Subjective Well-Being, Active Travel, and Socioeconomic Segregation

Abstract

1. Introduction

- -

- Is there an association between SWB and active travel according to Temuco’s NLSES and NHSES?

- -

- What sociodemographic characteristics, attitudes, lifestyles, social variables, and built environment features are linked to SWB in Temuco based on NLSES and NHSES?

2. Literature Review on SWB and Its Contributing Factors

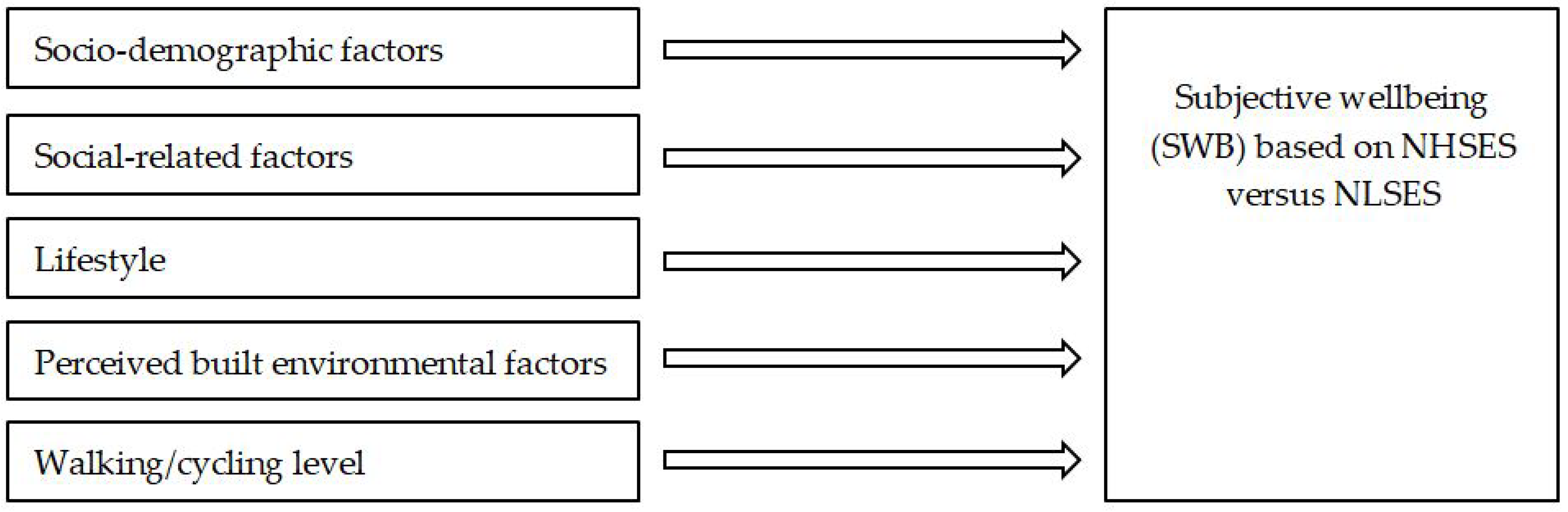

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Area, Neighborhood Selection, and Participants

3.2. Questionnaire Design and Measurments

3.3. Analysis

3.4. Ethical Approval

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. The Results of Exploratory Factor Analysis with Respect to Perceived Built Environment and Lifestyle in NLSES and NHSES

4.3. The SWB-Related Factors in NLSES

4.4. The SWB-Related Factors in NHSES

5. Discussion

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Diener, E.; Lucas, R.E.; Oishi, S. Advances and Open Questions in the Science of Subjective Well-Being. Collabra Psychol. 2018, 4, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, M.; Grimes, A. Sustainability and wellbeing: The dynamic relationship between subjective wellbeing and sustainability indicators. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2021, 27, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lu, S.; Chan, O.F.; Chui, C.H.K.; Lum, T.Y.S. Objective and perceived built environment, sense of community, and mental wellbeing in older adults in Hong Kong: A multilevel structural equation study. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 209, 104058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, S.; Habib, M.A. Investigation of life satisfaction, travel, built environment and attitudes. J. Transp. Health 2018, 11, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Shao, C.; Dong, C.; Wang, X. Happiness in urbanizing China: The role of commuting and multi-scale built environment across urban regions. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2019, 74, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, S.; Zhou, Y.; Yuan, Y. Associations between Community Cohesion and Subjective Wellbeing of the Elderly in Guangzhou, China—A Cross-Sectional Study Based on the Structural Equation Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Paydar, M.; Kamani Fard, A. Active travel and subjective well-being in Temuco, Chile. J. Transp. Geogr. 2025, 123, 104070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajrasouliha, A.; del Rio, V.; Francis, J.; Edmonson, J. Urban form and mental wellbeing: Scoping a framework for action. J. Urban. Des. Ment. Health 2018, 5, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Clatworthy, J.; Hinds, J.M.; Camic, P.M. Gardening as a mental health intervention: A review. Ment. Health Rev. J. 2013, 18, 214–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paydar, M.; Fard, A.K.; Sabri, S. Walking Behavior of Older Adults and Air Pollution: The Contribution of the Built Environment. Buildings 2023, 13, 3135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paydar, M.; Fard, A.K. Walking and cycling as recreational activities and their associated factors. Int. J. Urban Sustain. Dev. 2025, 17, 268–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joye, Y.; Köster, M.; Lange, F.; Fischer, M.; Moors, A. A Goal-Discrepancy Account of Restorative Nature Experiences. J. Environ. Psychol. 2023, 93, 102192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, M.; Kim, D.; Alizadeh, A.; Rokni, L. Evaluating the Mental-Health Positive Impacts of Agritourism; A Case Study from South Korea. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, J.; Aspinall, P. The Restorative Benefits of Walking in Urban and Rural Settings in Adults with Good and Poor Mental Health. Health Place 2011, 17, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, C.; Roux, A.V.D.; Galea, S. Are neighbourhood characteristics associated with depressive symptoms? A review of evidence: Table 1. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2008, 62, 940–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraus, M.W. Beggars do not envy millionaires: Social comparison socioeconomic status, and subjective well-being. In Handbook Well-Being; Diener, E., Oishi, S., Tay, L., Eds.; DEF Publishers: Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Link, B.G.; Phelan, J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1995, 35, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, N.E.; Boyce, T.; Chesney, M.A.; Cohen, S.; Folkman, S.; Kahn, R.L.; Syme, S.L. Socioeconomic status and health: The challenge of the gradient. Am. Psychol. 1994, 49, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, J.J.X.; Kraus, M.W.; Carpenter, N.C.; Adler, N.E. The association between objective and subjective socioeconomic status and subjective well-being: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2020, 146, 970–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, F.F.; Lindh, A. Socioeconomic Status, Need Fulfillment, and Subjective Well-Being. J. Happiness Stud. 2025, 26, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martela, F.; Lehmus-Sun, A.; Parker, P.D.; Pessi, A.B.; Ryan, R.M. Needs and well-being across Europe: Basic needs are closely connected with well-being, meaning, and symptoms of depression in 27 European countries. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 2023, 14, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann-Lunecke, M.G.; Mora, R.; Vejares, P. Perception of the built environment and walking in pericentral neighbourhoods in Santiago, Chile. Travel. Behav. Soc. 2021, 23, 192–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paydar, M.; Fard, A.K. Travel mode choice of the commuters and neighborhood socioeconomic segregation. J. Transp. Health 2025, 44, 102085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matas, M. Beyond residential segregation: Mapping Chilean social housing project residents’ vulnerability. J. Urban Manag. 2024, 13, 140–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paydar, M.; Kamani Fard, A. Active travel and socioeconomic segregation in Temuco, Chile: The association of personal factors and perceived built environment. Travel. Behav. Soc. 2025, 39, 100980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paydar, M.; Fard, A.K. Travel mode choice of the commuters in Temuco, Chile: The association of personal factors and perceived built environment. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2025, 31, 101412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Palmer, S.; Gallacher, J.; Marsden, T.; Fone, D. A systematic review of the relationship between objective measurements of the urban environment and psychological distress. Environ. Int. 2016, 96, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglitz, J.E.; Sen, A.K.; Fitoussi, J.P. Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress; Technical Report; Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress: Brussels, Belgium, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, A.E. Four Decades of the economics of happiness: Where next? Rev. Income Wealth 2018, 64, 245–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Ikei, H.; Igarashi, M.; Takagaki, M.; Miyazaki, Y. Physiological and Psychological Effects of a Walk in Urban Parks in Fall. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 14216–14228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, A.R.; Ebadi, M.; Shams, F.; Jangjoo, S. Human-built environment interactions: The relationship between subjective well-being and perceived neighborhood environment characteristics. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 21844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, J.; Hine, R.; Pretty, J. The health benefits of walking in greenspaces of high natural and heritage value. J. Integr. Environ. Sci. 2009, 6, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houlden, V.; Weich, S.; Porto de Albuquerque, J.; Jarvis, S.; Rees, K. The relationship between greenspace and the mental wellbeing of adults: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0203000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Qin, B. Exploring the link between neighborhood environment and mental wellbeing: A case study in Beijing, China. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 164, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araya, R.; Montgomery, A.; Rojas, G.; Fritsch, R.; Solis, J.; Signorelli, A.; Lewis, G. Common mental disorders and the built environment in Santiago, Chile. Br. J. Psychiatry 2007, 190, 394–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ettema, D.; Schekkerman, M. How do spatial characteristics influence well-being and mental health? Comparing the effect of objective and subjective characteristics at different spatial scales. Travel. Behav. Soc. 2016, 5, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyttä, M.; Broberg, A.; Haybatollahi, M.; Schmidt-Thomé, K. Urban happiness: Context-sensitive study of the social sustainability of urban settings. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2016, 43, 34–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arifwidodo, S.D.; Perera, R. Quality of life and compact development policies in bandung, Indonesia. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2011, 6, 159–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wang, D. Geography of urban life satisfaction: An empirical study of Beijing. Travel. Behav. Soc. 2016, 5, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouratidis, K. Is compact city livable? The impact of compact versus sprawled neighbourhoods on neighbourhood satisfaction. Urban Stud. 2017, 55, 2408–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naess, P. Residential location affects travel behavior—But how and why? The case of Copenhagen metropolitan area. Prog. Plan. 2005, 63, 167–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyden, K.M.; Goldberg, A.; Michelbach, P. Understanding the pursuit of happiness in ten major cities. Urban. Aff. Rev. 2011, 47, 861–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouratidis, K. Compact city, urban sprawl, and subjective well-being. Cities 2019, 92, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, V.; Torgersen, S.; Kringlen, E. Quality of life in a city: The effect of population density. Soc. Indic. Res. 2004, 69, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Tang, S.; Chuai, X. The impact of neighbourhood environments on quality of life of elderly people: Evidence from Nanjing, China. Urban Stud. 2017, 55, 2020–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, P.; Wood, A.; Ditchman, N.; Stephens, B. Life satisfaction of downtown high-rise vs. suburban low-rise living: A chicago case study. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, P.A.; Dussaillant, F.; Calvo, E. Social and Individual subjective wellbeing and Capabilities in Chile. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 628785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Klein, C. Social Capital or Social Cohesion: What Matters for Subjective Well-Being? Soc. Indic. Res. 2011, 110, 891–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araya, R.; Dunstan, F.; Playle, R.; Thomas, H.; Palmer, S.; Lewis, G. Perceptions of Social Capital and the Built Environment and Mental Health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 62, 3072–3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Actualización Plan de Transporte Temuco y Desarrollo de Anteproyecto, Etapa II, Ministerio de Transportes y Telecomunicaciones, SECTRA, Chile. 2017. Available online: http://www.sectra.gob.cl/biblioteca/detalle1.asp?mfn=3227 (accessed on 27 August 2021).

- Paydar, M.; Rodriguez, G.; Fard, A.K. Movilidad peatonal en Temuco, Chile: Contribución de densidad y factores sociodemográficos. Rev. Urban. 2022, 46, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halonen, J.I.; Pulakka, A.; Stenholm, S.; Pentti, J.; Kawachi, I.; Kivimäki, M.; Vahtera, J. Change in neighborhood disadvantage and change in smoking behaviors in Adults: A longitudinal, within-individual study. Epidemiology 2016, 27, 803–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Vuuren, C.L.; Reijneveld, S.A.; van der Wal, M.F.; Verhoeff, A.P. Neighborhood socioeconomic deprivation characteristics in child (0–18 years) health studies: A review. Health Place 2014, 29, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CENSO. Estimaciones y Proyecciones de la Población de Chile. 2017. Available online: https://www.censo2017.cl (accessed on 27 August 2021).

- Cerin, E.; Conway, T.L.; E Saelens, B.; Frank, L.D.; Sallis, J.F. Cross-validation of the factorial structure of the Neighborhood Environment Walkability Scale (NEWS) and its abbreviated form (NEWS-A). Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2009, 6, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joh, K.; Nguyen, M.T.; Boarnet, M.G. Can built and social environmental factors encourage walking among individuals with negative walking attitudes? J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2012, 32, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroesen, M.; Chorus, C. The role of general and specific attitudes in predicting travel behavior—A fatal dilemma? Travel. Behav. Soc. 2018, 10, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etminani-Ghasrodashti, R.; Paydar, M.; Hamidi, S. University-related travel behavior: Young adults’ decision-making in Iran. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 43, 495–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etminani-Ghasrodashti, R.; Paydar, M.; Ardeshiri, A. Recreational cycling in a coastal city: Investigating lifestyle, attitudes and built environment in cycling behavior. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 39, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, S.; Ohya, Y.; Odagiri, Y.; Takamiya, T.; Ishii, K.; Kitabayashi, M.; Suijo, K.; Sallis, J.F.; Shimomitsu, T. Association between perceived neighborhood environment and walking among adults in 4 cities in Japan. J. Epidemiol. 2010, 20, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paydar, M.; Fard, A.K. Older Adults’ Walking Behavior and the Associated Built Environment in Medium-Income Central Neighborhoods of Santiago, Chile. Infrastructures 2025, 10, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biermann, P.; Bitzer, J.; Gören, E. The relationship between age and subjective well-being: Estimating within and between effects simultaneously. J. Econ. Ageing 2022, 21, 100366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassenboehmer, S.C.; Haisken-DeNew, J.P. Heresy or enlightenment? The well-being age U-shape effect is flat. Econ. Lett. 2012, 117, 235–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunder, C.; Wiencierz, A.; Schwarze, J.; Küchenhoff, H. Well-being over the life span: Semiparametric evidence from British and German longitudinal data. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2013, 59, 154–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Desarrollo Social y Familia, Subsecretaría de Evaluación Social, en Base a Información de la Encuesta Casen y Encuesta Casen en Pandemia 2020. Fecha de Actualización: 30-08-2021. Available online: https://datasocial.ministeriodesarrollosocial.gob.cl/fichaIndicador/579/1 (accessed on 13 November 2022).

- Rokicka, M.; Palczyńska, M.; Kłobuszewska, M. Unemployment and Subjective Well-being Among the Youth: Evidence from a Longitudinal Study in Poland. Stud. Transit. States Soc. 2018, 10, 68–85. [Google Scholar]

- Gedikli, C.; Miraglia, M.; Connolly, S.; Bryan, M.L.; Watson, D. The relationship between unemployment and wellbeing: An updated meta-analysis of longitudinal evidence. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2022, 32, 128–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helgesson, M.; Johansson, B.; Nordqvist, T.; Lundberg, I.; Vingård, E. Unemployment at a young age and later sickness absence, disability pension and death in native Swedes and immigrants. Eur. J. Public Health 2012, 23, 606–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milner, A.; Page, A.; LaMontagne, A.D. Cause and effect in studies on unemployment, mental health and suicide: A meta-analytic and conceptual review. Psychol. Med. 2013, 44, 909–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrey, C.; Fleming, C. Public green space and life satisfaction in urban Australia. Urban Stud. 2014, 51, 1290–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ying, J.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhou, X. A systematic review of urban green spaces affecting subjective well-being: An explanation of their complex mechanisms. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 178, 113786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poortinga, W.; Denney, J.; Kelly, K.M.; Oates, R.; Phillips, R.; Oliver, H.; Hallingberg, B. Associations of reported access to public green space, physical activity and subjective wellbeing during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Environ. Psychol. 2024, 97, 102376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fard, A.K.; Paydar, M.; Navarrete, V.G. Urban Park Design and Pedestrian Mobility—Case Study: Temuco, Chile. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, M.C.; Lee, J.H. Measuring the Psychological Benefits of Green Space Usage: Development and Validation of the Green Space Use Satisfaction Scale. Soc. Indic. Res. 2025, 177, 599–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, D.; Parikh, N.S.; Giunta, N.; Fahs, M.C.; Gallo, W.T. The influence of neighborhood factors on the quality of life of older adults attending New York City senior centers: Results from the Health Indicators Project. Qual. Life Res. 2012, 21, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Kent, J.; Mulley, C. Transport disadvantage, social exclusion, and subjective well-being: The role of the neighborhood environment—Evidence from Sydney, Australia. J. Transp. Land Use 2018, 11, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Variable Description | NLSES | NHSES | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percentage | Mean | SD | Frequency | Percentage | Mean | SD | ||

| Level of walking (minutes per week) | 81.01 | 92.25 | 60.19 | 82.55 | |||||

| Cycling level | 0 = Did not ride a bicycle last week | 404 | 77.3 | 231 | 76.7 | ||||

| 1 = Using bicycle during last week | 77 | 22.6 | 70 | 23.3 | |||||

| Subjective well-being | 3.16 | 0.56 | 3.41 | 0.53 | |||||

| Sociodemographic variables | |||||||||

| Age | 18–29 | 90 | 18.7 | 80 | 26.7 | ||||

| 30–39 | 62 | 12.9 | 49 | 16.3 | |||||

| 40–49 | 69 | 14.3 | 69 | 22.9 | |||||

| 50–59 | 128 | 26.6 | 65 | 21.5 | |||||

| 60–69 | 85 | 17.7 | 23 | 7.6 | |||||

| 70–79 | 46 | 9.6 | 11 | 3.7 | |||||

| More than 80 | 1 | 0.2 | 4 | 1.3 | |||||

| Monthly income | Lower than 324,000 CLP | 183 | 38.2 | 16 | 5.4 | ||||

| 324,000–562,000 | 148 | 30.2 | 6 | 2 | |||||

| 562,000–899,000 | 105 | 21.9 | 25 | 8.4 | |||||

| 899,000–1,360,000 | 31 | 6.1 | 57 | 18.9 | |||||

| 1,360,000–1,986,000 | 10 | 2.2 | 88 | 29.1 | |||||

| More than 1,986,000 | 4 | 0.9 | 109 | 36.2 | |||||

| Private car | 0 = Do not Have | 295 | 61.3 | 0.39 | 0.48 | 64 | 21.3 | 0.79 | 0.40 |

| 1 = Have | 186 | 38.7 | 237 | 78.7 | |||||

| Driver’s license | 0 = Do not Have | 352 | 73.2 | 0.28 | 0.46 | 70 | 23.3 | 0.77 | 0.42 |

| 1 = Have | 129 | 26.8 | 231 | 76.7 | |||||

| Bicycle | 0 = Do not Have | 332 | 69 | 0.31 | 0.46 | 109 | 36.2 | 0.64 | 0.47 |

| 1 = Have | 149 | 31 | 192 | 63.8 | |||||

| Job situation | Retired | 83 | 17.2 | 26 | 8.6 | ||||

| Student | 37 | 7.7 | 54 | 17.9 | |||||

| With work | 222 | 46.2 | 188 | 62.5 | |||||

| Unemployed | 51 | 10.6 | 6 | 2 | |||||

| Housewife | 88 | 18.3 | 27 | 9 | |||||

| Social-related variables | |||||||||

| Take a walk or go biking with others | 2.38 | 1.17 | 2.74 | 1.10 | |||||

| Being motivated to engage in physical activity | 2.72 | 1.08 | 3.03 | 0.96 | |||||

| Helping the neighbors in the neighborhood | 3.02 | 0.98 | 2.96 | 0.81 | |||||

| Participating regularly in physical activities | 2.51 | 1.05 | 2.91 | 0.93 | |||||

| Seeing other active people inspires me | 2.67 | 1.07 | 3.08 | 0.93 | |||||

| Component | How Often (in the Last Month) Do You Engage in Various Activities During Your Free Time? | Loadings |

|---|---|---|

| Going to restaurants and malls with friends | A visit to commercial centers. | 0.633 |

| Joining friends at the cafeteria or restaurant. | 0.845 | |

| A gathering with friends. | 0.706 | |

| Physically active people | Participate in indoor sports or the gym. | 0.804 |

| Participating in outdoor activities, cycling, running, or walking. | 0.858 |

| Component | How Often (in the Last Month) Do You Engage in Various Activities During Your Free Time? | Loadings |

|---|---|---|

| Visiting restaurants and socializing with friends | Joining friends at the cafeteria or restaurant. | 0.870 |

| A gathering with friends. | 0.820 | |

| Visiting parks for exercise and reading | Visit nearby parks and plazas. | 0.661 |

| Participating in outdoor activities, cycling, running, or walking. | 0.785 | |

| Read magazines, newspapers, and books. | 0.605 |

| Component | Loadings | |

|---|---|---|

| Safety | The sidewalks are covered with several obstacles. | 0.657 |

| The amount of traffic on the surrounding streets makes it difficult or unpleasant to walk or bike. | 0.706 | |

| Most drivers in my neighborhood travel faster than the posted speed limits. | 0.731 | |

| My neighborhood has a high crime rate. | 0.671 | |

| Accessibility | The place I live in is easily accessible on foot from a number of locations. | 0.656 |

| I can walk a short distance from my house to the bus station. | 0.692 | |

| My house is within walking distance of parks and plazas. | 0.782 | |

| To travel from one location to another, there are numerous alternate paths. | 0.559 | |

| Basic walking infrastructure | The walkways in my neighborhood are generally sufficiently wide. | 0.812 |

| The sidewalks in my neighborhood are well-maintained (paved, even, and not a lot of cracks). | 0.851 | |

| Basic cycling infrastructure | Bicycle trails are easily accessible in or close to my neighborhood. | 0.783 |

| In the locations I typically go to on my daily journey, there is plenty of space for bicycle parking. | 0.829 | |

| Esthetic vistas during the day and at night | It is pleasant for me to walk through my neighborhood and take in the scenery. | 0.495 |

| At night, my neighborhood’s streets are well-lit. | 0.829 | |

| Traffic lights and slope | Walking on the streets in my neighborhood is challenging due to their steepness. | 0.868 |

| In my neighborhood, pedestrian lights and crosswalks make it easier to cross major streets. | 0.553 |

| Component | Loadings | |

|---|---|---|

| Accessibility | I can easily walk from my house to stores. | 0.742 |

| The place I live is easily accessible on foot from a number of locations. | 0.733 | |

| My house is within walking distance of parks and plazas. | 0.721 | |

| To travel from one location to another, there are numerous alternate paths. | 0.719 | |

| Basic walking infrastructure both during the day and at night | The walkways in my neighborhood are generally sufficiently wide. | 0.777 |

| The sidewalks in my neighborhood are well-maintained (paved, even, and not a lot of cracks). | 0.829 | |

| At night, my neighborhood’s streets are well-lit. | 0.666 | |

| Traffic safety | The sidewalks are covered with several obstacles. | 0.721 |

| The amount of traffic on the surrounding streets makes it difficult or unpleasant to walk or bike. | 0.782 | |

| Most drivers in my neighborhood travel faster than the posted speed limits. | 0.714 | |

| Basic bike infrastructure, such as enough traffic signals for crossings | Bicycle trails are easily accessible in or close to my neighborhood. | 0.822 |

| In the locations I typically go to on my daily journey, there is plenty of space for bicycle parking. | 0.530 | |

| In my neighborhood, pedestrian lights and crosswalks make it easier to cross major streets. | 0.484 | |

| Bus station access | I can walk a short distance from my house to the bus station. | 0.801 |

| Variables | Standardized Coefficients | t | p-Value | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.147 | 2.327 | 0.020 * | 2.38 |

| Retired | 0.180 | 2.479 | 0.014 * | 3.15 |

| Students | 0.159 | 2.860 | 0.004 ** | 1.85 |

| People with work | 0.316 | 4.231 | 0.000 ** | 3.32 |

| Housewife | 0.251 | 3.764 | 0.000 ** | 2.62 |

| People are eager to assist their neighbors | 0.141 | 2.894 | 0.004 ** | 1.41 |

| My family/friends participate in physical activities regularly | 0.112 | 1.924 | 0.05 * | 2.01 |

| Built environment (accessibility) | 0.110 | 2.453 | 0.015 * | 1.19 |

| Built environment (alope and traffic lights) | −0.140 | −2.899 | 0.004 ** | 1.39 |

| Variables | Standardized Coefficients | t | p-Value | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.227 | 2.778 | 0.006 ** | 2.56 |

| People are eager to assist their neighbors | 0.137 | 2.373 | 0.018 ** | 1.26 |

| Lifestyle (reading books and engaging in physical activity in parks) | 0.177 | 2.818 | 0.005 ** | 1.50 |

| Built environment (access to bus stations) | 0.108 | 1.880 | 0.05 * | 1.26 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Paydar, M.; Kamani Fard, A. Subjective Well-Being, Active Travel, and Socioeconomic Segregation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10571. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310571

Paydar M, Kamani Fard A. Subjective Well-Being, Active Travel, and Socioeconomic Segregation. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10571. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310571

Chicago/Turabian StylePaydar, Mohammad, and Asal Kamani Fard. 2025. "Subjective Well-Being, Active Travel, and Socioeconomic Segregation" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10571. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310571

APA StylePaydar, M., & Kamani Fard, A. (2025). Subjective Well-Being, Active Travel, and Socioeconomic Segregation. Sustainability, 17(23), 10571. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310571