Abstract

The global energy transition is a central pillar of climate change mitigation and sustainable development. While international frameworks such as the Paris Agreement and the UN 2030 Agenda emphasize renewable energy as a driver of decarbonization, the degree of ambition and coherence across governance levels remains uneven. The European Union (EU), through the European Green Deal, the “Fit for 55” package, and the REPowerEU plan, has adopted legally binding targets for climate neutrality by 2050 and a 55% emission reduction by 2030. However, national implementation via National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs) reveals substantial divergences among Member States. This study applies qualitative content analysis and comparative policy review to EU-level strategies, selected NECPs (Poland, Germany, France, Spain), and global frameworks (Agenda 2030, Paris Agreement, IEA, IRENA, IPCC reports). The analysis also incorporates a comparative perspective with other major economies, including China, Japan, and the United States, to situate EU policy within the global context. Documents were coded according to categories of strategic goals, regulatory and financial instruments, and identified barriers. Triangulation with secondary literature ensured validity and contextualization. The findings show that EU frameworks demonstrate higher ambition and legal enforceability compared to global initiatives, yet internal fragmentation persists. Germany and Spain emerge as frontrunners with ambitious renewable targets, while France relies heavily on nuclear power and Poland lags behind with the latest coal phase-out date. Global frameworks emphasize inclusivity and energy access but lack binding enforcement. The study contributes a comparative framework for evaluating renewable energy policies, identifies best practices and structural gaps, and highlights the dual challenge of EU climate leadership and internal coherence. These insights provide guidance for policymakers and a foundation for future research on governance and just transition pathways.

1. Introduction

The energy transition towards a low-carbon economy has become one of the most pressing challenges for contemporary policy and science [1]. Global frameworks, such as the Paris Agreement of 2015 and the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, established ambitious goals for reducing greenhouse gas emissions and ensuring universal access to clean energy [2,3]. The Paris Agreement commits to keeping the increase in global average temperature “well below 2 °C” above pre-industrial levels, while pursuing efforts to limit it to 1.5 °C, which in practice requires achieving global climate neutrality by mid-century [2,3,4]. Similarly, Goal 7 of the 2030 Agenda (SDG7) obliges the international community to secure affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all, while simultaneously increasing the share of renewable energy sources (RES) [3].

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), in its Sixth Assessment Report (AR6), clearly emphasizes that limiting warming to 1.5 °C or 2 °C requires “rapid, deep and sustained reductions in greenhouse gas emissions,” particularly drastic reductions in energy-related emissions [1]. This means a swift departure from the uncontrolled combustion of fossil fuels and the massive deployment of low- and zero-carbon energy technologies [1,4]. In this context, renewable energy emerges as the central pillar of the transition—not only as a technical solution to the climate crisis, but also as a driver of socio-economic development [4,5].

However, despite growing political and social awareness, global emission trends remain alarming. According to the World Energy Outlook (IEA), the implementation of current policies would lead to a temperature increase of around 2.4 °C by the end of the century, highlighting the gap between political declarations and actual actions [6]. At the same time, the renewable sector is experiencing unprecedented growth: in 2023, the world added a record 560 GW of new renewable capacity, while global investment in clean energy reached approximately USD 2 trillion annually—almost double the investment in fossil fuel projects [7]. This indicates both a breakthrough in the economic competitiveness of renewable technologies and a continuing lag in the pace of transition relative to climate science requirements [1,4].

Analyses by the IPCC and IRENA clearly demonstrate that energy systems dominated by RES are indispensable for achieving climate goals [1,5]. In 1.5 °C-aligned scenarios, the share of low-emission sources in global electricity generation reaches 93–97% by 2050 [1]. According to IRENA, the share of renewables in total final energy consumption must increase from ~16% in 2020 to around 77% by 2050 [5]. Achieving this scale requires not only massive investment but also the removal of institutional, infrastructural, and social barriers [1,5].

Against this backdrop, the European Union (EU) has positioned itself as a leader in energy and climate transition. Its flagship strategy, the European Green Deal (2019) [8], commits Europe to becoming the first climate-neutral continent by 2050, a target legally enshrined in the European Climate Law (2021) [8]. To achieve this, the Fit for 55 package raised the EU’s emission reduction target to −55% by 2030 and set a binding minimum of 42.5% renewables in the energy mix by 2030 [9]. In response to the energy crisis and Russia’s aggression against Ukraine in 2022, the EU also introduced the REPowerEU plan, aimed at accelerating renewable deployment and reducing dependence on fossil fuel imports [10].

A key tool for translating EU-level targets into national policies includes the National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs) [11]. Under the Governance Regulation, each Member State must prepare an integrated plan outlining objectives and policies across five dimensions: decarbonization, energy efficiency, energy security, the internal market, and research and innovation [12]. This mechanism is designed to operationalize EU targets at the national level. However, assessments show significant divergences in ambition and progress among Member States, raising questions about the coherence of EU policy [11,12].

The research gap in the literature lies precisely at this comparative level. While numerous studies focus on EU climate-energy policy in isolation, and extensive global transition scenarios exist (IEA, IRENA, IPCC) [1,4,5,6,7], systematic comparative content analyses of EU strategies versus global frameworks remain rare. In particular, differences in the treatment of renewables, financing instruments, implementation barriers, and social justice considerations between the EU and the global level have been insufficiently explored.

Building on this research gap, the study addresses the following questions:

To what extent are EU renewable energy strategies more coherent and ambitious than global policy frameworks?

- How do National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs) of selected EU Member States align with overarching EU goals?

- What policy instruments and governance mechanisms are emphasized at EU and global levels, and where are the key divergences?

- What lessons can be drawn for strengthening both EU and global pathways toward decarbonization and sustainable development?

To guide the analysis, the study focuses on three dimensions: the ambition and legal character of EU versus global strategies, the coherence of EU policies in light of internal divergences, and the balance between inclusivity, access, and regulatory enforcement.

The aim of this article is to fill this gap by conducting a comparative content analysis of EU and global strategic documents—including the European Green Deal [8], Fit for 55 [9], REPowerEU [10], selected NECPs [11], and global frameworks such as the 2030 Agenda [3], the Paris Agreement [2], and reports by the IEA [6,7] and IRENA [5]. The analysis examines how these strategies define the role of renewables, set targets and timelines, propose implementation instruments, and incorporate social justice and energy access dimensions.

The contribution of this article to the literature is fourfold:

- identifying convergences and divergences between EU and global frameworks;

- highlighting best practices and gaps in implementation;

- proposing a methodological framework for cross-level climate-energy policy comparison;

- linking findings to the broader scholarly debate on the effectiveness of public policies in the energy transition.

The subsequent sections of the article present the Literature Review (Section 2), the applied methodology, comparative results of EU and global strategies, and implications for climate policy and future research on sustainable development.

2. Literature Review

Recent literature emphasizes the unprecedented urgency of action to decarbonize the global economy. The IPCC AR6 (2022) indicates that in order to limit global warming to 1.5 °C, global greenhouse gas emissions must peak no later than 2025 and be reduced by approximately 43% by 2030 compared to 2019 levels [1]. Yet, even scenarios assuming the full implementation of current national commitments (the so-called current policies) lead to warming of around 2.4 °C by the end of the century [6]. This demonstrates that the current pace of implementing climate and energy policies is insufficient. At the same time, renewable energy has been expanding rapidly: in 2023, a record 560 GW of new renewable capacity was installed worldwide, while global investment in clean energy rose to about USD 2 trillion annually—nearly double the amount directed toward fossil fuel projects [7]. The growing scale of investment has led to projections that global coal use will peak around 2025, while demand for oil and natural gas will stabilize before the end of the 2020s [6]. Despite these positive trends, the window for achieving the Paris Agreement goals continues to narrow, a point often captured in the literature with the phrase “now or never” [4].

At the international level, the UN 2030 Agenda and the Paris Agreement (2015) [3] set the key directions for global policy. The 2030 Agenda, through the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), established Goal 7 (ensuring access to affordable and clean energy) and Goal 13 (climate action) as global development priorities [3]. The Paris Agreement created a mechanism of voluntary nationally determined contributions (NDCs) intended to collectively limit warming to “well below 2 °C” while pursuing 1.5 °C [2]. However, IRENA analyses highlight a significant ambition deficit in existing NDCs. According to its Global Renewables Outlook 2020, the renewable energy targets declared by countries cover only about 40% of the capacity required by 2030 for the world to be on track toward climate objectives [5]. In other words, there is a substantial gap between global commitments and the level of transformation demanded by climate science [1,4].

International energy organizations provide additional analytical frameworks for assessing the transition. The International Energy Agency (IEA), in successive World Energy Outlook reports (2019–2023), presents scenarios that illustrate the consequences of current policies as well as trajectories consistent with climate neutrality [13]. The most recent WEO 2024 stresses that even with the projected growth of renewables (10 TW capacity by 2030), efforts would need to triple to follow a 1.5 °C-compatible pathway [13]. The IEA also underscores the importance of phasing out fossil fuel subsidies, which remain at record levels and continue to slow the shift to clean energy [13]. Similarly, the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), in its Global Renewables Outlook: Energy Transformation 2050 (2020), argues that an accelerated transition could bring significant socio-economic benefits [5]. Its climate-aligned scenario foresees a 70% reduction in energy-related CO2 emissions by 2050, with more than 90% of these reductions achieved through renewables and energy efficiency improvements [5].

Importantly, the literature highlights the need for a holistic approach: the energy transition should be coupled with socio-economic development. IRENA points to the European Green Deal as an example of a strategy that links decarbonization with economic and social objectives, proposing a model of a just transition based on solidarity and the protection of vulnerable groups [5,8]. Likewise, the latest IPCC reports emphasize that rapid emission reductions can proceed in parallel with the achievement of other Sustainable Development Goals—appropriate climate policies can improve air quality, health, job creation, and innovation [1,3].

In summary, global literature from 2018–2023 portrays both the widening gap between political commitments and scientific requirements, and the unprecedented technological and financial progress in clean energy [1,4,5,6,7,13]. These two contrasting conclusions—the insufficiency of current action versus the growing techno-economic potential of renewables—provide the starting point for analyzing strategies at the European Union level.

2.1. The European Union as a Frontrunner in Climate and Energy Governance

The European Union has long been regarded as a leader of global climate policy, and the past decade has brought forward a new generation of ambitious strategic frameworks that have become the subject of numerous studies. The key initiatives include the European Green Deal (2019), the legislative package Fit for 55 (2021), and the REPowerEU plan (2022)—each addressing distinct challenges, but collectively forming a comprehensive EU strategy for energy and climate transition [8,9,10].

The European Green Deal (EGD) was defined by the European Commission as a new growth strategy aimed at making Europe the first climate-neutral continent by 2050 [8]. Unlike earlier policies (e.g., the 3 × 20 Package or the Energy Union), the EGD is characterized by a holistic approach—integrating climate goals with biodiversity protection, circular economy development, and social justice. According to the Commission, the EGD encompasses a wide range of actions: raising 2030 climate ambition (including an emissions reduction target of at least 55%), transforming energy systems towards clean and affordable energy, greening industry, advancing sustainable mobility, and engaging civil society through the European Climate Pact. Scholars have described the EGD as an unprecedented attempt to reorient the EU economy towards climate neutrality, while also serving as a test of the EU’s ability to translate an ambitious agenda into effective legal and financial instruments [8]. The strategy is also firmly anchored in EU values such as solidarity, cohesion, and high levels of environmental protection, ensuring that the green transition is implemented in a “just” manner, leaving no one behind.

The launch of the EGD was followed by concrete legislative steps. The most important was the adoption of the European Climate Law (2021), which made the target of climate neutrality by 2050 and the interim target of −55% net emissions reduction by 2030 legally binding [14]. To operationalize these objectives, the Commission prepared the Fit for 55 package (July 2021) [9], a comprehensive set of revisions to existing legislation. This included reforms to the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS), the Effort Sharing Regulation (ESR), the Renewable Energy Directive (RED II/III), the Energy Efficiency Directive, new CO2 standards for vehicles, and the introduction of a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) [15,16,17,18]. The aim was to align EU climate and energy policies with the new, more demanding −55% target. Fit for 55 also raised the renewable energy target: the original 32% target for 2030 (set in 2018) was revised upward, first to 40% and subsequently, in the context of REPowerEU, to 45% [9,10]. The final revision of the Renewable Energy Directive (RED III, adopted in 2023) established a binding minimum of 42.5% renewables by 2030, with a political aspiration of 45%—nearly doubling the 2022 EU share of ~23% [16].

The REPowerEU plan (2022) was the EU’s response to the energy crisis and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Its overarching objective is to end the EU’s dependence on Russian fossil fuels well before 2030, while simultaneously accelerating the green transition. The plan rests on three pillars: (1) saving energy, (2) scaling up clean energy deployment—especially renewables, and (3) diversifying energy supplies through new partnerships and hydrogen imports. In the field of renewables, REPowerEU introduced extraordinary measures, such as raising the 2030 target to 45% and fast-tracking permitting procedures [10]. The temporary regulation adopted in late 2022 simplified and accelerated authorization processes, declaring renewable projects to be of “overriding public interest” [19]. Scholars note that lengthy permitting procedures have historically been a major barrier to renewable deployment in Europe, and thus REPowerEU seeks to overcome this by introducing tools such as renewable go-to areas and streamlined environmental assessments in designated zones [19].

Comparative studies of EU and global frameworks highlight the EU’s leading role in raising climate ambition. The EU became the first major economy to adopt climate neutrality into binding law [14] and to prepare a detailed legislative package for its implementation [9]. In contrast, national commitments under the UN’s Paris Agreement (NDCs) often remain less ambitious than measures already enacted within the EU [2]. While the Paris Agreement is based on voluntary, bottom-up pledges, the EU has implemented a top-down governance model with binding targets and solidarity mechanisms for less wealthy Member States [12,14]. Instruments such as the Modernisation Fund and the Social Climate Fund are designed to support just transition by compensating weaker economies, while flexibility mechanisms ensure burden-sharing remains fair [14,20]. At the same time, the European Commission emphasizes continuous monitoring of implementation and the identification of barriers at Member State level [12].

2.2. Implementation of EU Policies at the National Level: NECPs and Member States’ Progress

To translate EU-level objectives into national action, new governance and planning instruments were introduced. The key tool is the National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs) for 2021–2030, required under Regulation (EU) 2018/1999 (the so-called Governance Regulation) [12]. Each Member State was obliged to prepare an integrated plan covering the five pillars of the Energy Union:

- -

- decarbonization, including the development of renewables and CO2 reduction,

- -

- energy efficiency,

- -

- energy security,

- -

- the internal energy market,

- -

- research, innovation, and competitiveness [11,12].

The NECPs serve as national roadmaps, outlining country-specific targets (e.g., renewables shares, energy savings) and the planned policies and measures to achieve them by 2030 [11]. The first final NECPs were submitted at the end of 2019, while updated versions—reflecting the raised ambition of the European Green Deal, Fit for 55, and REPowerEU—are due in 2024 [11,21]. The implementation system foresees biennial progress reports by Member States, as well as an EU-wide “State of the Energy Union” report [11]. This mechanism of multi-level governance is designed to align national actions with EU objectives while respecting Member State specificity and autonomy.

Recent literature analyzes both the content of the NECPs and the pace of their implementation. An EU-wide assessment highlights substantial differences in ambition: some Member States (e.g., Sweden, Denmark) set targets above the minimum requirements, particularly in the field of renewables, while others (e.g., Poland, Hungary) barely met the baseline [22].

Recent empirical studies confirm that the pace of the energy transition across the EU is highly uneven. Brodny et al. (2025) [23] developed the Energy Transition Efficiency Index (ETEI), allowing for a synthetic evaluation of progress in 2013–2023. Their findings revealed stark contrasts between Western European countries—marked by rapid increases in RES deployment and emission reductions—and Central and Eastern European countries, where progress remains significantly slower. The authors warn that without narrowing these disparities, the achievement of EU climate goals may be at risk [23].

Moreover, by 2023, it became clear that many countries were late in updating their plans: by mid-2024, most had not yet submitted revised NECPs, delaying the Commission’s collective assessment [21]. Nevertheless, the first NECP Progress Reports were submitted in 2023. The Commission’s technical evaluation concluded that emission reductions must triple in order for the EU to reach the −55% target by 2030. Current efforts remain insufficient—the average annual reductions of the past decade must be tripled to meet the requirements for 2020–2030 [21].

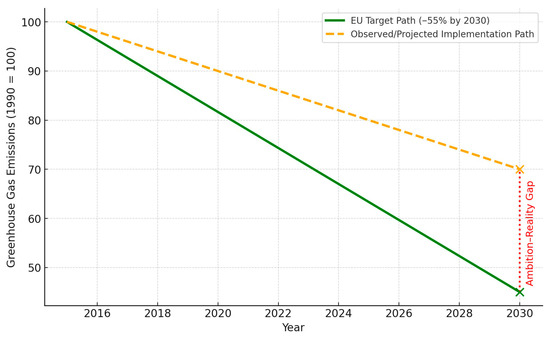

While the European Union has set an ambitious goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 55% by 2030 compared to 1990 levels, the actual pace of implementation remains considerably slower. To illustrate this discrepancy, Figure 1 contrasts the official EU decarbonisation trajectory with the observed and projected national implementation path.

Figure 1.

EU Emissions Reduction: Ambition vs. Reality.

As shown in Figure 1, the EU’s ambition requires a steady and steep decline in emissions, reaching 45% of the 1990 baseline by 2030. However, the observed trajectory indicates a reduction closer to 30%, leaving a significant ambition–reality gap. This gap underscores the challenges of aligning national energy strategies with collective EU climate objectives and highlights the urgency of accelerating implementation across Member States.

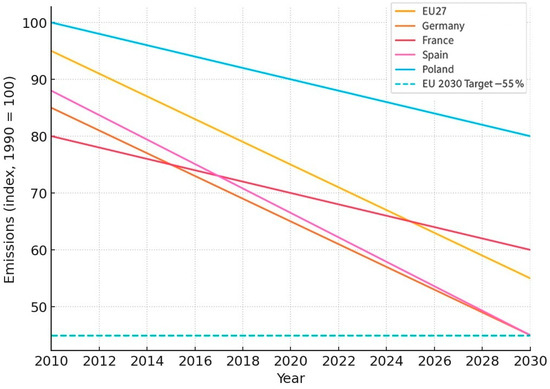

To complement the aggregate EU-level analysis presented in Figure 1, Figure 2 illustrates the evolution of CO2 emissions in the EU and four selected Member States (Germany, France, Spain, and Poland) between 2010 and 2030. By comparing national trajectories with the overall EU pathway, the figure highlights the extent to which Member States converge—or diverge—from the collective 2030 reduction target.

Figure 2.

CO2 Emissions in the EU and Selected Countries (2010–2030). Source: Own elaboration based on EU Commission and Eurostat data.

As Figure 2 shows, Germany is broadly aligned with the EU trajectory, moving steadily toward the −55% target. Spain also demonstrates a relatively strong performance, with reductions approaching −45% by 2030, though still below the EU benchmark. France follows a more moderate path, consistent with its reliance on nuclear energy and slower renewable expansion. Poland, by contrast, exhibits only marginal reductions of around −20%, remaining far from the EU average and underscoring persistent structural challenges. These divergent trajectories reveal the uneven pace of national transitions and the risks of fragmented progress, which could jeopardize the achievement of the Union’s collective climate objectives.

The Commission thus urged Member States to accelerate implementation and ensure the full execution of their planned measures.

In recent years, growing scholarly attention has been directed toward analyzing NECPs as instruments of EU energy-climate governance. While many Member States declare high levels of ambition regarding renewables and decarbonization, the degree of alignment with overarching EU objectives remains inconsistent. Maris (2021) [24] stresses that Member State compliance with the European Green Deal depends heavily on the advancement of Europeanisation and the strength and independence of national climate institutions [24]. Di Foggia (2024), in turn, compared EU countries’ pathways to 2030 and concluded that only a subset of NECPs are fully consistent with the ambition of the Fit for 55 package [25].

Civil society assessments point to concrete areas of delay. CAN Europe underlines that even before the energy crisis, many Member States—such as France, Italy, and Poland—were underperforming in non-ETS sectors (transport, buildings) and failing to exploit their renewables potential. Most countries need to intensify efforts in building renovation and transport electrification, especially given that the Fit for 55 package introduced a new ETS2 for these sectors, raising the cost of delays [26]. Similarly, CAN Europe stresses that raising the EU’s renewables target to 42.5–45% requires NECP updates, since the combined ambition of the 2019 plans is no longer sufficient. The Commission’s preliminary review of new drafts in 2023 concluded that Member States’ efforts still fall short, and final NECPs “do not yet guarantee” achievement of 2030 targets, calling for further strengthening [21].

Poland provides a clear illustration of the challenges of implementing EU policies at the national level. Between 2010 and 2020, Poland struggled to meet even less ambitious targets: the Supreme Audit Office (NIK) warned in 2018 that the 15% RES target for 2020 was at risk, as the RES share had fallen to ~11% in 2016 amid a lack of coherent policy. Indeed, the 2020 target was achieved largely thanks to the post-2019 boom in photovoltaics and the purchase of statistical transfers from other countries [22]. The NIK concluded that for years, Poland lacked a consistent support framework, with delays in auctions and regulatory uncertainty deterring investors [27]. Only under EU pressure was the national energy policy (PEP2040) updated and RES auctions accelerated. In the context of Fit for 55, however, Poland must now scale up its ambition substantially. The draft updated NECP (WAM scenario) foresees a 50.4% emissions reduction by 2030 and 70% by 2040, as well as a 32.6% RES share in 2030 (over 56% in electricity), far more ambitious than earlier plans (PEP2040, 2021, targeted ~30% by 2030). The new plan envisions 50 GW of new RES capacity, including offshore wind and solar, alongside a 65% reduction in power sector emissions by 2040. Nonetheless, experts warn that realization will require addressing barriers such as grid modernization, streamlined permitting, and securing hundreds of billions of PLN in investment [26,28]. Political attitudes are also shifting: while until 2023 the Polish government often took a skeptical stance toward EU climate initiatives, the new parliamentary majority elected in 2023 has declared stronger alignment with EU climate policy [29].

In sum, studies of NECPs and national strategies reveal a persistent implementation gap across many EU countries. There is a clear tension between raising ambition and the administrative capacity to translate targets into investments and projects. The literature emphasizes the need to strengthen governance mechanisms—through financial support for weaker regions, enhanced monitoring, and enforcement of compliance. Some argue that the EU should raise its targets further, toward 65–75% reductions by 2030, to align with the Paris Agreement [21]. Yet, without improved implementation, even the current targets risk remaining only on paper.

2.3. Energy Governance and Renewable Support Policies

The effective implementation of RES strategies and decarbonization requires appropriate forms of governance—public policy management—and well-designed implementation instruments. The literature identifies several key aspects in this context: multi-level governance of climate and energy policy, the design of renewable energy support instruments, and overcoming institutional barriers that slow down the transition.

In the EU, energy and climate policy is frequently discussed through the lens of multi-level governance, since it is implemented simultaneously at EU, national, regional, and local levels. The EU framework (e.g., NECPs) requires cooperation between central governments, local authorities, businesses, and civil society [11,12]. The requirement of public consultations during the drafting of NECPs and initiatives such as the European Climate Pact illustrate that participation and vertical coordination are considered essential for the success of the transition. At the same time, EU institutions have been strengthening their supervisory role—for instance, the Commission monitors national progress through annual reports and recommendations, while the Climate Law introduced a corrective mechanism if the EU deviates from its trajectory [14].

Strunz (2021) [30] notes that although EU governance frameworks encourage higher climate ambition and increasingly stringent targets, their implementation mechanisms remain partly “soft,” relying more on political coordination than on strict enforcement. This results in an implementation deficit, particularly in Member States that are lagging behind in the transition [3,30]. Similarly, Gajdzik et al. (2024) [31], analyzing the European industrial sector, emphasize that the absence of a unified approach to RES support in industry constitutes a serious barrier. Instead of a common mechanism, a patchwork of national instruments prevails, leading to fragmentation and slowing progress in several Member States [31].

Scholars describe this phenomenon as a gradual shift from “soft” to “harder soft governance.” Nevertheless, Member States remain pivotal actors, as they retain authority over their national energy mix and support instruments. Consequently, the literature increasingly focuses on national RES policies: which instruments are adopted, which prove effective, and which barriers persist.

Since the 2000s, a wide array of renewable support mechanisms has been developed and studied. The most common include feed-in tariffs (FiTs) and feed-in premiums, green certificate (quota) systems, renewable auctions, tax incentives, investment grants, and infrastructure support measures (e.g., grid-connection subsidies). In the EU, FiTs initially dominated and played a critical role in the growth of wind energy in Germany and solar PV in Spain. However, after 2015, under EU state aid guidelines, many countries shifted toward competitive RES auctions [15,16]. Literature shows that auctions significantly reduced RES costs through competition, but their effectiveness depends on design: overly aggressive bidding may lead to under-delivery of projects (undersubscription). Regulatory stability is also crucial: Poland’s Supreme Audit Office (NIK) recommended predictable auction schedules and support conditions to provide investors with long-term certainty [27]. A lack of such stability—e.g., delayed auctions in Poland (2016–2018) or retroactive policy changes in Hungary and Spain—has often acted as a major barrier to investment.

Institutional and infrastructural factors also play a decisive role. Gajdzik et al. (2024) [31] categorize barriers into four groups:

- -

- political—lack of long-term strategies, unstable legislation, conflicts among stakeholders,

- -

- administrative—complex and lengthy permitting, restrictive spatial planning rules, bureaucracy,

- -

- infrastructural—limited grid capacity, bottlenecks in connecting new sources, insufficient storage,

- -

- socio-economic—local opposition (NIMBY), low public acceptance, financing difficulties, high capital costs, and limited skilled workforce [31].

Many of these barriers are reflected in national reports. Poland’s Supreme Audit Office (2018) emphasized inconsistent planning and lengthy permitting as major obstacles [27]. The Institute for Reform (2024) recommends implementing renewable go-to areas (as defined by RED III) and strengthening administrative capacity in permitting authorities, alongside genuine public consultations to avoid local opposition [32]. Experiences across Europe show that insufficient dialogue with local communities often triggers resistance—such as against wind farms—slowing or even blocking projects. As a result, awareness-raising and public engagement are increasingly recognized as essential components of RES policy.

The literature also stresses the economic and social justice dimensions of governance. Rosen (2020) [33] notes that effective RES policy must balance environmental goals with economic concerns such as industrial competitiveness and household energy costs. From the outset, the European Green Deal emphasized a “Just Transition,” establishing the Just Transition Fund to mitigate social impacts, particularly in coal-dependent regions [20]. The Institute for Structural Research (IBS) conducted modeling for Poland showing that deep decarbonization can be achieved without severe macroeconomic costs if pursued gradually and supported by targeted investments [34]. According to IBS, phasing out coal by 2050 may require ~15% higher investment in the power sector, but could reduce sectoral CO2 emissions by nearly 70% with negligible long-term GDP impact [34]. Crucially, however, this depends on financial allocations and labor transition policies to prevent social disruption, which simulations show is feasible through gradual change and worker retraining [34].

In summary, the latest literature suggests that the success of the energy transition depends not only on setting ambitious targets but above all on effective governance and implementation. Removing administrative and infrastructural bottlenecks, designing stable support schemes, and ensuring public acceptance are all essential. While the EU provides direction and legal-financial frameworks, Member States remain the decisive actors. Thus, country case studies (e.g., Poland) provide valuable insights into what facilitates and what hinders RES deployment. The conclusions from the literature are consistent: ambitious strategies must be matched by adequate governance, otherwise they risk falling short of their objectives. The energy transition is a formidable challenge, but as IEA, IRENA, and IPCC reports confirm, it is also a historic opportunity for long-term sustainable economic and social development [1,5,6]. The condition, however, is to accelerate action now, in line with the IPCC’s warning that “this is the last moment to secure a livable planet for future generations” [1,4].

3. Materials and Methods

This study applies a qualitative research design, combining document analysis with comparative policy review to investigate the strategic frameworks governing renewable energy development in the European Union (EU) and in global contexts. The rationale for employing this approach stems from the fact that renewable energy policies are primarily articulated through formal strategies, legislative frameworks, and institutional reports, making document-based analysis particularly suitable for capturing the ambitions, instruments, and underlying narratives of the energy transition. The methodological objective was to identify similarities, differences, and inconsistencies in policy frameworks, and to assess their contribution to achieving long-term sustainability and decarbonization goals.

This study was designed to answer the research questions outlined in the Introduction. The content analysis was guided by three analytical dimensions: (1) strategic goals and targets, (2) policy instruments (regulatory, financial, governance), and (3) identified barriers. These categories were selected to operationalize the research questions and to test the working hypotheses on the relative ambition, coherence, and enforceability of EU versus global frameworks.

The dataset comprised two main groups of documents. The first included EU-level policies and strategies such as the European Green Deal [8], the Fit for 55 legislative package [9], the REPowerEU plan [10], and the National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs) submitted by Member States [11]. These documents reflect both supranational and national commitments and allow for an assessment of alignment and variation within the EU. The second group consisted of global frameworks, including the Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development [3], the Paris Agreement, and flagship reports published by international organizations such as the International Energy Agency (IEA) [6,13] and the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) [5]. Documents were selected according to two criteria: their formal status as guiding frameworks for renewable energy and climate action, and their publication after 2015, corresponding to the post-Paris Agreement era in which renewable energy has become a central pillar of global climate policy.

The primary method of inquiry was qualitative content analysis. Each document was systematically examined and coded according to predefined analytical categories. These categories encompassed (1) strategic goals, such as renewable energy penetration targets, decarbonization deadlines, and climate neutrality commitments; (2) regulatory and financial instruments, including subsidies, taxation schemes, carbon pricing mechanisms, and investment support; and (3) barriers and challenges explicitly acknowledged in the documents, such as infrastructural constraints, financial risks, or issues of energy equity. The use of a standardized coding protocol ensured that diverse documents could be systematically compared and that findings remained transparent and replicable.

In practical terms, the coding protocol was applied to all documents according to three analytical categories: ambition, coherence, and feasibility. Each category was operationalized with a set of indicators to ensure consistency.

Ambition was assessed on the basis of quantitative targets (e.g., percentage share of renewables in final energy consumption, declared emission reduction levels, year of climate neutrality). For example, references to “42.5% renewables by 2030” were coded under ambition.

Coherence captured the alignment between EU-level strategies and national NECPs, as well as the internal consistency of individual plans. Mentions of “delays in NECP updates” or “divergent coal phase-out dates” were coded as coherence challenges.

Feasibility reflected the availability of regulatory, financial, and infrastructural instruments. Mentions of “permitting bottlenecks,” “funding gaps,” or “grid modernization” were coded under feasibility.

To ensure comparability, a standardized coding sheet was developed. Each reference was assigned to one or more of the three categories, and examples were cross-checked during triangulation with secondary sources. Table 1 later illustrates the comparative outcomes of this coding process, summarizing the assessment for the EU, China, Japan, and the United States.

Table 1.

Coding Framework for Ambition, Coherence, and Feasibility.

To increase the transparency and replicability of the coding process, Table 1 presents the coding framework used in this study. It summarizes the three analytical categories—ambition, coherence, and feasibility—together with their main indicators and examples of coding rules. This framework served as the basis for classifying content across EU and global policy documents and ensured systematic comparison between cases.

This coding framework provided a structured lens for classifying policy content and allowed for systematic cross-case comparison. By applying the categories of ambition, coherence, and feasibility across EU-level strategies, Member States’ NECPs, and global frameworks, it was possible to identify both convergences and divergences in policy design. The results of this coding process are further synthesized in the comparative assessment presented in Table 2, which summarizes the evaluation for the EU, China, Japan, and the United States.

Table 2.

Comparative Assessment of Ambition, Coherence, and Feasibility.

The coding framework presented in Table 1 was directly applied to generate the comparative assessment of ambition, coherence, and feasibility summarized in Table 2.

The coded data were then subjected to comparative analysis. At the EU level, the study investigated the degree of coherence between national NECPs and overarching EU strategies, highlighting variations in ambition, timelines, and policy instruments across Member States [11,12]. On the global scale, the EU’s strategic approach was compared with international frameworks to assess how the European policy landscape fits into, or diverges from, the wider global discourse on renewable energy. Particular attention was given to the extent to which the EU positions itself as a frontrunner in the energy transition and how this leadership is reflected—or challenged—by global counterparts. This comparative perspective not only reveals policy divergences but also identifies areas of convergence that may foster international collaboration.

To strengthen the validity of results, the analysis was complemented by triangulation with secondary sources, including peer-reviewed academic studies and industry reports such as the IEA World Energy Outlook [6,13], IPCC Assessment Reports [1,4], and IRENA’s Global Renewables Outlook [5]. Triangulation enabled a critical evaluation of policy documents against independent expert assessments, thereby reducing the risk of relying solely on the declarative nature of official strategies. This methodological choice ensured that conclusions reflected both the intentions of policymakers and the broader context of technological, economic, and social feasibility.

The synthesis of findings was structured into a comparative framework that captured best practices, gaps, and inconsistencies across the analyzed documents. By organizing results into a structured matrix of categories—strategic goals, instruments, barriers, and implementation mechanisms—the study provides a coherent lens for evaluating renewable energy policies. The framework also highlights institutional and strategic challenges that may hinder the coherence of energy transition pathways, such as the misalignment between national and supranational objectives or the limited integration of social equity considerations.

Finally, it is important to acknowledge methodological limitations. While document analysis offers valuable insights into the declared priorities and strategies of policymakers, it does not directly measure implementation outcomes. Moreover, the scope of this study is limited to documents available in English and official EU languages, which may exclude relevant perspectives from non-EU countries where documentation is less accessible. Despite these limitations, the methodological approach offers a robust and systematic foundation for comparative policy analysis. By emphasizing transparency in document selection, coding, and triangulation, this study ensures that its findings are both replicable and relevant to future research on renewable energy policy.

In addition, three analytical categories were introduced to strengthen the evaluation framework: ambition, coherence, and feasibility.

Ambition was defined as the quantitative and qualitative level of the adopted targets (e.g., share of renewables in final energy consumption, greenhouse gas reduction targets, or declared year of climate neutrality).

Coherence referred to the degree of alignment between EU-level frameworks and national NECPs, as well as the internal consistency of strategies and their instruments.

Feasibility captured the availability of regulatory, financial, and infrastructural instruments, as well as political and social conditions for achieving the declared goals.

The documents were coded against both quantitative and qualitative indicators. Quantitative indicators included: (1) the share of renewables in final energy consumption by 2030, (2) the planned coal phase-out date, and (3) the level of GHG reduction by 2030 compared to 1990 (see Table 3 and Table 4).

Table 3.

Comparison of EU vs. Global Renewable Energy Strategies.

Table 4.

Comparison of Selected NECPs (Poland, Germany, France, Spain).

The evaluation was conducted using a comparative scoring matrix, in which each document was assessed along the three categories: ambition (low–medium–high), coherence (low–medium–high), and feasibility (limited–moderate–high). This approach enabled a systematic comparison of EU frameworks with global strategies, as well as across selected Member States. Similar methodological approaches have been applied in earlier policy analyses of renewable energy governance [23,30].

To provide a more systematic comparison of the three analytical dimensions introduced in this study—ambition, coherence, and feasibility—a summary assessment was developed for the European Union, China, Japan, and the United States. This comparative matrix synthesizes the main findings of the analysis and allows for a clearer evaluation of how major economies approach renewable energy strategies across different governance contexts (Table 2).

The results presented in Table 5 demonstrate that while the EU stands out for the legal enforceability of its targets, internal fragmentation limits overall coherence and feasibility. China’s ambition is equally high but constrained by continued coal dependency. Japan shows strong coherence due to its centralized strategy but faces feasibility challenges linked to its reliance on nuclear energy. The United States, despite weaker institutional coherence at the federal level, scores high on feasibility thanks to massive financial incentives under the Inflation Reduction Act. Taken together, these findings illustrate that climate leadership is multidimensional and depends not only on ambition but also on the ability to ensure coherent governance and practical feasibility.

Table 5.

Comparison of Key Climate and Energy Targets of the EU, China, Japan and USA.

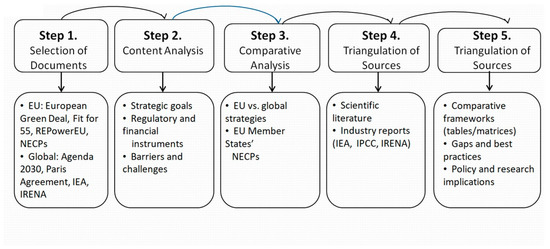

To present a clear overview of the methodological approach adopted in this study, Figure 3 illustrates the five main steps of the research process. The analysis began with the selection of EU and global policy documents, followed by a qualitative content analysis focusing on strategic goals, regulatory and financial instruments, and identified barriers. Next, a comparative analysis was conducted between EU and global frameworks, as well as among selected Member States’ National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs) [11]. To enhance validity, triangulation with scientific literature and industry reports was applied [1,4,5,6,13]. Finally, the results were synthesized into comparative frameworks, identifying gaps, best practices, and implications for both policy and research.

Figure 3.

Research methodology: Steps of document analysis and comparative assessment. Source: Author’s own elaboration based on the [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29].

The results of this study are presented in two complementary parts. First, a comparative assessment of EU-level and global renewable energy frameworks is provided in order to highlight similarities and differences in the scope, ambition, and enforcement of policy commitments. This analysis focuses on strategic objectives, regulatory instruments, and implementation mechanisms, contrasting the European Union’s legally binding approach [8,9,10,14,15,16] with the largely voluntary nature of global frameworks [2,3,5,6,13]. Second, a comparative examination of selected National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs) from Poland, Germany, France, and Spain illustrates the heterogeneity of national pathways toward decarbonization within the EU [11,21,22,26,27,28,29]. The results are presented in the form of summary tables and figures to provide a clear and structured overview of both supranational and national strategies.

4. Results

The comparative analysis of EU-level strategies and global frameworks revealed both convergences and divergences in the framing of renewable energy as a driver of sustainable development. While the EU demonstrates a higher level of ambition and coherence in its strategic frameworks [8,9,10,14,15,16], global initiatives emphasize inclusivity and universal access to energy [2,3,5] but often lack binding enforcement mechanisms [6,13]. At the same time, the examination of selected National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs) shows considerable differences between Member States, particularly in their reliance on specific technologies, target timelines, and implementation instruments [11,21,22,26,27,28,29].

The comparative assessment of the European Union’s renewable energy strategies and global frameworks highlights important differences in scope, ambition, and enforcement mechanisms. While both levels emphasize the urgent need for energy transition and decarbonization, the EU adopts a more legally binding and structured approach [8,9,10,14,15,16], whereas global frameworks often rely on voluntary commitments and scenario-based projections [2,3,5,6,13]. Table 3 presents a synthesis of the main goals, instruments, and implementation mechanisms, contrasting the European Union’s policy architecture with international initiatives such as the Paris Agreement [2], the Agenda 2030 [3], and reports by the IEA [6,13] and IRENA [5].

The comparison presented in Table 1 reveals that the European Union has developed a significantly more coherent and binding framework for renewable energy development than the global governance structures. The EU’s objectives, such as climate neutrality by 2050 and a minimum 55% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, are legally enforceable through directives and the obligation of Member States to submit and update National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs). This contrasts with global frameworks, where commitments under the Paris Agreement or the Agenda 2030 are largely voluntary and depend on the political will of individual countries.

In terms of renewable energy targets, the EU provides clear quantitative milestones, such as achieving a 42.5% share of renewables by 2030 under the REPowerEU plan, while global frameworks avoid binding numerical commitments and rely instead on long-term scenarios. This discrepancy reflects the EU’s ambition to act as a frontrunner in the energy transition, while the international level seeks to balance inclusivity with flexibility, accommodating the different capacities of developed and developing countries.

Another important finding concerns policy instruments. The EU has institutionalized strong mechanisms such as the Emissions Trading System (ETS), the Just Transition Fund, and mandatory reporting obligations, backed by enforcement through the European Commission. Global initiatives, on the other hand, focus on financial support mechanisms like the Green Climate Fund but lack a comparable enforcement capacity. This divergence raises questions about the effectiveness of global governance in driving coordinated action compared to the EU’s regionally binding system.

Finally, the dimension of equity is framed differently. The EU emphasizes reducing energy poverty and ensuring a just transition within its borders, whereas global frameworks prioritize universal access to energy, particularly in developing countries. Both approaches are crucial, yet they operate on different scales and highlight the tension between regional depth and global breadth of the energy transition.

In addition to the comparison between the European Union and global frameworks, the analysis of selected National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs) provides valuable insights into the diversity of approaches among EU Member States. Although all countries are formally aligned with the overarching EU climate neutrality target for 2050, their intermediate goals, preferred technologies, and timelines for phasing out fossil fuels vary considerably. Table 4 summarizes the main features of the NECPs of Poland, Germany, France, and Spain, illustrating the heterogeneity of national strategies in terms of renewable energy targets, energy mix, policy instruments, and identified challenges.

The comparison of selected National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs) in Table 2 illustrates the substantial heterogeneity of Member States’ approaches to renewable energy and decarbonization. Germany and Spain stand out as the most ambitious in terms of renewable energy penetration in electricity generation, targeting 80% and 74%, respectively, by 2030, while Poland remains significantly less ambitious, aiming at around 32% in final energy consumption [11,21,22,26,27,28,29]. France adopts an intermediate position, with a 40% target, but distinguishes itself through its continued reliance on nuclear power as a cornerstone of its energy mix [11].

Differences are also evident in the technological preferences of the analyzed countries. Germany and Spain prioritize a diversified portfolio of renewables, with strong emphasis on wind, solar, and hydrogen, while France maintains nuclear energy as the backbone of its decarbonization strategy, complementing it with renewable sources [11,21]. Poland, in contrast, continues to rely heavily on coal, planning only a gradual reduction with a phase-out horizon as late as 2049, and introducing nuclear power after 2033 as a new strategic element [22,27,28,29].

Timelines for phasing out coal further highlight the divergence. Spain plans a complete phase-out by 2030, Germany by 2038 (with political ambitions to accelerate this to 2030), while France has almost entirely eliminated coal already [11,21,26]. Poland remains the outlier with its late target, raising concerns about its alignment with EU-wide climate objectives [27,28,29].

Policy instruments also differ. While Germany and Spain rely extensively on renewable energy auctions, carbon pricing, and investment in grid modernization [11,21,26], France leverages strong state involvement in nuclear development and complementary RES schemes [11]. Poland, on the other hand, uses auctions and the capacity market, but its heavy coal dependency and delayed nuclear program indicate structural barriers that complicate its transition [22,27,28,29].

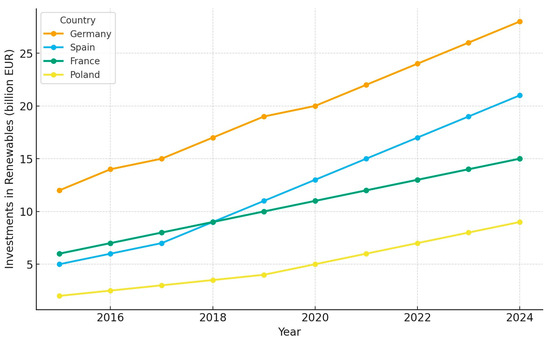

To complement the analysis of policy instruments and national strategies, it is essential to also examine investment dynamics in renewable energy. Financial flows not only reflect political commitment but also provide a tangible indicator of the pace and credibility of the transition (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Dynamics of renewable energy investments in Germany, Spain, France, and Poland (2015–2024). Source: Own elaboration based on IEA, Eurostat, and national energy agencies.

As shown in Figure 4, the investment trajectories of the four countries reveal substantial differences in the pace and depth of their energy transitions. Germany stands out as the clear frontrunner, with steadily increasing investments that nearly doubled from 2015 to 2024, consolidating its leadership role in the EU renewable energy market. Spain follows a dynamic growth path, particularly after 2018, reflecting both national policy reforms and strong market interest, which enabled the country to reach more than 20 billion EUR in annual investments by 2024. France demonstrates a more moderate, incremental pattern, largely consistent with its reliance on nuclear power as a decarbonisation strategy, but nevertheless showing gradual reinforcement of renewables. Poland, although starting from a very low baseline, shows signs of acceleration after 2020, with investments reaching approximately 9 billion EUR in 2024; however, the gap with Western European peers remains significant. These discrepancies highlight the structural asymmetries in financing capacity, policy implementation, and market development across the EU, raising concerns about the feasibility of achieving the collective 2030 renewable energy targets without stronger financial alignment and support mechanisms.

These divergences underscore the challenge of ensuring coherence across the EU’s climate and energy policy. While the EU provides a common framework and overarching goals [8,9,10,14,15,16], national NECPs reflect varying socio-economic conditions, political choices, and energy system legacies [11,21,22,26,27,28,29]. This heterogeneity may hinder the pace of collective decarbonization, but it also highlights areas of innovation and leadership that could serve as examples for other Member States.

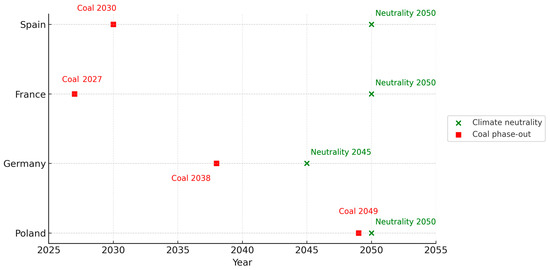

To provide a clearer visual representation of the national differences summarized in Table 2, Figure 1 illustrates the timelines for coal phase-out and climate neutrality targets in Poland, Germany, France, and Spain. The figure highlights the diversity of approaches: while France and Spain are moving towards an early coal exit (2027 and 2030 respectively), Germany sets its target for 2038 (with political debate on acceleration), and Poland remains the latest with 2049 [11,21,22,26,27,28,29]. In terms of climate neutrality, all countries converge on the EU’s 2050 target, except Germany, which aspires to achieve it earlier, by 2045 [11]. This visualization underscores both the shared long-term objectives and the striking divergence in short- and medium-term strategies.

In order to complement the tabular comparison of national strategies, Figure 5 visualizes the timelines for coal phase-out and climate neutrality in four selected Member States: Poland, Germany, France, and Spain [11,21,22,26,27,28,29]. This graphical representation allows for a clearer understanding of the temporal dimension of their commitments, showing not only the shared long-term objective of climate neutrality but also the significant divergence in the short- and medium-term targets for phasing out coal.

Figure 5.

Climate neutrality and coal phase-out timelines in selected NECPs (Poland, Germany, France, Spain). Source: Own elaboration based on European Commission [11,12], National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs) of Poland, Germany, France, and Spain [11,21,22], and complementary assessments (Forum Energii [26], NIK [27], CIRE [28], 300Gospodarka [29]).

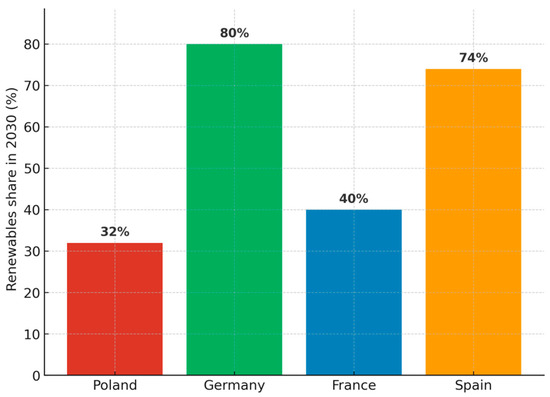

In addition to coal phase-out and climate neutrality timelines, it is equally important to examine the renewable energy targets that Member States have set for 2030. Figure 5 provides a comparison of the planned shares of renewables in the energy mix of Poland, Germany, France, and Spain [11,21,22,26,28,29]. The figure highlights the ambitious commitments of Germany and Spain, contrasted with the more moderate objectives of France and the relatively low target declared by Poland. This visualization further underlines the heterogeneity of national strategies and the challenge of achieving coherence within the EU’s collective decarbonization pathway.

The visualization in Figure 6 highlights the strong divergence in coal phase-out timelines among the selected Member States, despite a broadly shared commitment to climate neutrality [11,12,21,26,27,29]. France and Spain demonstrate early coal exit strategies, reinforcing their alignment with ambitious renewable integration, while Germany sets a later phase-out date, although with political debate on accelerating the timeline. Poland remains the most delayed, planning coal dependency until 2049, which significantly contrasts with EU-level ambitions. At the same time, all four countries converge around the climate neutrality objective for 2050, with Germany aiming for an even earlier target of 2045. This illustrates both the unity of long-term goals and the fragmentation of short- and medium-term implementation strategies.

Figure 6.

Renewable energy targets for 2030 in selected NECPs. Source: Own elaboration based on European Commission [11,12], National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs) of Poland, Germany, France, and Spain [11,21,22], and complementary assessments (Forum Energii [26], IEO [22], CIRE [28], 300Gospodarka [29]).

The comparison of renewable energy targets presented in Figure 6 reinforces the observation that, despite a common EU framework, national strategies remain highly heterogeneous. Germany and Spain clearly position themselves as leaders of the transition with ambitious goals exceeding 70–80% renewables by 2030 [11,21,22,26,27,28,29],while France pursues a more balanced approach by combining moderate renewable targets with strong reliance on nuclear power [11]. Poland, on the other hand, lags behind with the lowest target [22,27,28,29], raising questions about its ability to align with the EU’s overall climate ambitions. Together with the differences in coal phase-out timelines shown in Figure 5, these results highlight both the opportunities and the challenges of achieving coherence across the EU’s decarbonization pathway.

The findings of this study demonstrate both the progress and the persistent fragmentation of renewable energy policies across governance levels. The comparison between the European Union and global frameworks reveals a fundamental distinction in the nature of commitments. While the EU has adopted a legally binding, target-driven approach with strong enforcement mechanisms [8,9,10,11,12,14,15,16], international initiatives such as the Paris Agreement and the Agenda 2030 rely primarily on voluntary pledges and scenario-based projections [2,3,5,6,13]. This confirms earlier assessments by the IEA and IRENA [5,6,13], which underline the gap between global ambition and the robustness of policy instruments necessary for rapid decarbonization. The EU’s institutional capacity to enforce compliance through the submission and monitoring of National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs) [11,12] sets it apart as a frontrunner in climate governance, yet its leadership also exposes tensions with global frameworks that lack similar enforcement capacity.

The analysis of selected NECPs (Poland, Germany, France, Spain) further illustrates the divergence within the EU itself. Although all Member States are aligned with the overarching 2050 climate neutrality goal [14], their intermediate strategies vary considerably in scope and ambition.

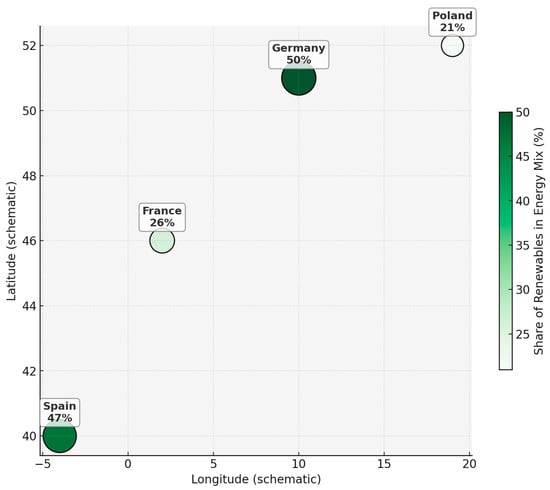

To better illustrate these national divergences, Figure 7 presents the progress of selected EU countries (Germany, France, Spain, and Poland) in terms of the share of renewables in their energy mix as of 2022. This visualization highlights both the frontrunners and the laggards, thereby providing a clearer context for the subsequent analysis of national strategies.

Figure 7.

Progress of selected EU countries in renewable energy share (2022).

As the figure shows, Germany and Spain have already achieved relatively high levels of renewable penetration, positioning themselves as leaders of the EU transition. France remains more moderate, relying heavily on nuclear power, while Poland continues to lag significantly behind its peers. These disparities underscore the challenge of aligning national trajectories with the collective EU target for 2030 and 2050.

Germany and Spain have positioned themselves as leaders by setting high renewable energy penetration targets (74–80% in electricity generation by 2030) [11,21,22,26,27,28,29], reflecting IRENA’s recommendation that rapid scale-up of solar and wind is critical to meet 1.5 °C pathways [5]. France, in contrast, pursues a hybrid model, relying heavily on nuclear power complemented by renewable [11], while Poland represents the least ambitious case, with modest renewable targets and the latest coal phase-out date (2049) [22,27,28,29]. These results echo IPCC AR6 findings [1], which emphasize the importance of near-term mitigation actions, warning that delays in fossil fuel phase-out risk locking in high-carbon infrastructures.

The visualizations in Figure 3 and Figure 4 reinforce these patterns by highlighting the temporal and quantitative heterogeneity of national strategies. While France and Spain align with accelerated coal exit pathways [11,21,26], Germany’s later target (2038) and Poland’s very late phase-out illustrate the difficulty of harmonizing national socio-economic conditions with EU-level objectives [27,28,29]. At the same time, the discrepancy between high renewable ambitions in Germany and Spain and the relatively modest targets in France and especially Poland underscores the uneven distribution of transition leadership within the Union [11,21,22,26,27,28,29]. Such fragmentation poses challenges for EU-wide energy security and collective progress toward the 2030 and 2050 targets.

From a governance perspective, these divergences suggest that the EU’s ability to act as a cohesive climate leader on the global stage may be constrained by internal inconsistencies. If Member States pursue highly heterogeneous strategies, the credibility of EU climate diplomacy could be weakened. Conversely, the ambitious examples of Germany and Spain could serve as benchmarks or sources of policy learning for less advanced Member States [21,26]. This aligns with the broader literature on policy diffusion, which highlights the potential for frontrunners to shape regional and international trajectories [30].

The broader implication of these findings is that achieving coherence across multiple levels of governance—national, regional, and global—remains one of the central challenges of the energy transition. While the EU demonstrates institutional strength in designing binding frameworks [8,9,10,11,12,14,15,16], the heterogeneity of Member State implementation and the voluntary nature of global commitments [2,3,5,6,13] continue to limit the effectiveness of collective action. Addressing these issues requires not only stricter alignment mechanisms at the EU level but also stronger integration of equity considerations at the global level, ensuring that ambitious decarbonization does not exacerbate inequalities either within or across countries [20].

Finally, the results contribute to the academic debate by offering a structured comparative framework that integrates EU and global perspectives. By combining content analysis with comparative assessment, this study highlights both the progress achieved and the structural barriers that persist. It underlines the need for future research to explore the interplay between technological pathways, institutional design, and socio-political contexts that shape the feasibility of renewable energy strategies [23,24,25,30,31,32,33,34].

5. Discussion

5.1. Interpretation of Results in the Context of EU and Global Strategies

The comparative analysis of the European Union’s strategies and global climate–energy policy frameworks (UN, IEA, IRENA), juxtaposed with the NECPs of Poland, Germany, France, and Spain, revealed diverse approaches and levels of ambition. The EU strategy—rooted in the European Green Deal, the Fit for 55 package, and the mechanism of National Energy and Climate Plans—stands out for its relatively coherent, multidimensional approach to renewable energy deployment and climate neutrality [8,9,10,11,12,14,15,16].

By contrast, global agreements such as the UN Paris Agreement articulate general goals (e.g., limiting warming to 1.5 °C and reaching climate neutrality by mid-century) but rely on voluntary nationally determined contributions (NDCs). This results in a persistent gap between declarations and actual implementation—current global pledges put the world on a warming trajectory of approximately 2.5–2.9 °C [35]. Our findings are consistent with the literature suggesting that the EU often adopts more ambitious and binding targets than the global average, positioning itself as a “leader” in the energy transition [36].

At the same time, our results confirm earlier findings that the Union is not a monolithic bloc—the pace of renewable energy development and the barriers encountered differ significantly across Member States [23,24]. As Wójcik-Czerniawska et al. observe, Poland and Germany have pursued divergent paths: Poland, traditionally reliant on coal, opts for a gradual transition, whereas Germany pushes for rapid decarbonization [23]. Our analysis reflects this divergence—countries vary in their energy mixes, RES targets, and policy instruments, underscoring the theoretical argument in energy governance that national conditions play a decisive role in shaping climate policy outcomes.

In line with the theory of multi-level governance, effective transformation requires coordination across EU, national, and local levels [32,37]. Our analysis suggests that the NECP mechanism, though designed to integrate these levels, is in practice sometimes treated merely as a formal exercise. This is consistent with observations that some governments regard NECPs more as a bureaucratic obligation than as genuine strategic roadmaps [37].

Therefore, interpreting the results requires consideration not only of formal policy targets but also of the institutional and social contexts in which they are embedded—including the dimensions of climate and energy justice. Energy justice offers a critical analytical lens, emphasizing equal access to the benefits of transition and citizen participation in decision-making [38]. Linking our results to this framework highlights that climate ambition must go hand in hand with social equity and public acceptance, a theme discussed in greater detail in the subsequent sections of this discussion.

5.2. Coherence of EU Policy vs. Internal Fragmentation

The analysis revealed persistent tensions between the coherence of the EU’s common climate policy and the fragmentation of actions at the Member State level. On the one hand, the Union has set collective targets—most recently raising the renewables share in final energy consumption to 42.5% by 2030 [39]—demonstrating increasing climate ambition compared to global benchmarks. On the other hand, national plans (NECPs) exhibit significant differences in aspiration levels.

Leaders of the transition, such as Germany and Spain, have put forward highly ambitious goals. Spain’s Plan Nacional Integrado de Energía y Clima (PNIEC) targets a 48% share of renewables in final energy consumption and as much as 81% in electricity generation by 2030 [40]. Similarly, Germany aims for around 80% renewables in electricity by 2030, supported by rapid expansion of wind and solar power. Yet even such advanced plans face gaps: for instance, the German NECP does not fully specify instruments for emerging technologies and relies heavily on energy imports and future solutions such as hydrogen [41].

Osuma and Yusuf (2025) argue that achieving energy security and sustainability in the EU requires not only scaling up renewables but also maintaining a more diversified energy mix, tailored to the specific conditions of Member States [42].

In contrast, laggards in the transition—notably Poland—initially submitted plans with relatively low ambition (around 21–23% RES in 2030 according to the 2019 NECP [11]). Although the most recent update significantly raised targets—including a tripling of solar PV capacity to 29 GW and 56% renewables in electricity generation by 2030 [39,43]—this remains well below the ambition level of the frontrunners, and even below earlier political declarations (the government had at one point announced 70% renewables in electricity) [43]. These divergences illustrate internal EU fragmentation, driven by differing economic, social, and political conditions.

The findings of this study therefore suggest that while the EU presents itself as one of the most ambitious actors globally—with climate neutrality by 2050, a 55% emission reduction target by 2030, and a legally binding 42.5% renewables share—such ambition at the legal and declaratory level does not always translate into consistent implementation across Member States. Implementation gaps, divergent coal phase-out timelines (Poland 2049 vs. Spain 2030), and differences in renewable targets (32% in Poland vs. 80% in Germany) reveal the limits of coherence within the Union

For this reason, assessments of EU ambition should be more cautious: high-level declarations may overstate the actual feasibility of the transition, particularly given national disparities. Moreover, when placing the EU in a broader comparative perspective, it is important to acknowledge that other major economies also articulate ambitious energy and climate strategies. For example, China has pledged to peak carbon emissions before 2030 and reach climate neutrality by 2060, targeting 1200 GW of wind and solar by 2030. Similarly, Japan has committed to climate neutrality by 2050 and set a target of 36–38% renewables in its energy mix by 2030. These examples demonstrate that while the EU remains the most institutionally coherent actor with legally binding frameworks, its leadership is challenged by the scale and ambition of other economies.

In addition, the United States has also adopted ambitious climate and energy targets, reinforcing its role as a major global actor. Under the Biden Administration’s updated Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), the U.S. committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 50–52% below 2005 levels by 2030, achieving 100% carbon-free electricity by 2035, and reaching net-zero emissions no later than 2050. While U.S. commitments are not anchored in supranational legislation as in the EU, federal initiatives such as the Inflation Reduction Act (2021) [14] provide unprecedented levels of financial support for renewable energy deployment, electrification, and clean technology innovation. This positions the United States as both a competitor and a potential partner to the EU in driving global climate ambition.

Eastern and Southern Member States have often delayed or softened collective action, while Western countries have pushed for greater ambition, creating coalition tensions [36].

While the EU remains the most institutionally coherent actor in terms of legally binding climate and energy frameworks, its ambition must be interpreted with caution. High-level targets such as climate neutrality by 2050, a 55% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, and a minimum 42.5% renewable share do not always translate into uniform implementation across Member States. Significant implementation gaps, delayed coal phase-out timelines, and divergences in renewable energy targets undermine overall coherence within the Union. At the same time, other major economies have also articulated ambitious strategies. China has pledged to peak emissions before 2030 and reach climate neutrality by 2060, while Japan has committed to carbon neutrality by 2050 and aims for 36–38% renewables by 2030. To contextualize the EU’s position globally, Table 5 compares the core climate and energy targets of the EU, China, and Japan.

The comparison in Table 5 highlights both the strengths and the limitations of the EU’s climate and energy strategy in the global context. The EU stands out as the only actor with legally binding frameworks and detailed governance mechanisms, which enhances its credibility as a global climate leader. However, China and Japan also demonstrate high levels of ambition in terms of capacity expansion and renewable integration, even if their commitments remain political rather than legally enforceable. This suggests that while the EU maintains institutional leadership, its global influence depends not only on the ambition of its targets but also on its ability to deliver them in practice. At the same time, the rise of other ambitious players indicates that climate leadership is increasingly shared, reinforcing the need for stronger international coordination and policy learning.

Poland provides a clear example: historically reliant on coal, it long delayed the liberalization of onshore wind, with restrictive regulations in place until 2023. Such conflicts of interest—between energy security based on domestic resources and emissions reduction targets—have been highlighted as major obstacles to raising collective ambition [36]. Our findings corroborate this diagnosis: contradictions between frontrunners and laggards hinder the development of a unified, coherent EU climate policy.

This fragmentation carries serious consequences: without compensatory measures, the Union risks failing to achieve its collective 2030 targets. The latest assessment of updated NECPs confirms that the sum of national contributions remains insufficient to meet agreed objectives on renewables and energy efficiency [44]. In other words, the EU ambition gap stems largely from shortcomings in certain national plans, and unless these gaps are closed, the collective goal will remain out of reach.

The political fragmentation of Europe—manifested in East–West and North–South divides—thus represents a major challenge to EU policy coherence, as emphasized both by our findings and by earlier expert analyses [36]. The potential consequence is a weakening of the EU’s position as a unified climate front, unless these divides are mitigated through solidarity mechanisms (e.g., the Just Transition Fund, technology transfers) and by promoting the principle of “common but differentiated responsibility” within the Union.

In an optimistic scenario, however, ambitious climate policy could become a unifying force for Europe—provided it is perceived as fair and collectively implemented [36]. Therefore, our discussion highlights the importance of solidarity and cooperation: frontrunners (e.g., Germany, Spain) should continue to raise ambition while simultaneously supporting lagging Member States in their transitions, to avoid the emergence of a two-speed “energy Europe.”

5.3. Effectiveness of Global Frameworks and the Role of the EU as a Leader

Our analysis also compared EU strategies with the broader global context, including key international documents and scenarios (UN, IEA, IRENA). Global policy frameworks—such as the UN 2030 Agenda (SDG 7 on clean energy) and the Paris Agreement—provide a shared vision and direction of travel. However, their effectiveness ultimately depends on the sum of national efforts. Unfortunately, as noted above, current global commitments remain far from sufficient to achieve the 1.5 °C target [35].

International agencies have repeatedly stressed the need for greater ambition. At COP28, parties agreed on a global goal to triple renewable energy capacity by 2030 and double the rate of energy efficiency improvements [43]. Yet, according to IRENA, current government plans will deliver only about half of the required renewable capacity. On the present trajectory, the world will reach ~7.4 TW of new RES by 2030 instead of the necessary 11.2 TW—an implementation gap of roughly 34% [43]. Similarly, a review of NDCs by UNEP warns that without additional measures, the world is heading toward ~2.5 °C of warming, requiring emission reductions of 28–42% by 2030 beyond existing pledges [35].