1. Introduction

Corporate innovation is a core engine for enterprises to gain sustained competitive advantage and drive economic growth [

1]. The characteristics of innovation activities—such as high risk, long incubation cycles, and uncertain returns—do not align with the strict standards traditional financial institutions apply to credit repayment. Consequently, corporate innovation activities are more susceptible to financing constraints.

Against this backdrop, promoting in-depth cooperation between finance and the real economy serves as a crucial prerequisite for building internationally competitive real-industry clusters and a necessary condition for the sustained and healthy development of the economy [

2]. The key to financial services for the real economy lies in leveraging finance to support enterprise innovation [

3], enhancing the availability of funds for enterprises, and creating an efficient “testing ground” for them to foster new economic growth points. Therefore, effectively promoting financial support for the development of the real economy and better channeling funds into the innovation activities of real-sector enterprises is of great significance for enhancing the quality and efficiency of enterprise development with financial assistance and achieving sustainable economic development.

In a free market economy, the level of corporate R&D investment tends to fall below the social optimum, a phenomenon characterized as “market failure” [

4]. This is primarily attributable to the positive externalities inherent in innovation activities, information asymmetries, and the public good nature of knowledge outputs [

5,

6].

The China Industry–Finance Collaboration pilot policy, leveraging the national industry–finance collaboration platform, has established a robust information-sharing mechanism. By emphasizing coordinated development between industry and finance, it effectively enhances the efficiency of information exchange between financial institutions and real-economy enterprises, providing a viable pathway for the efficient allocation of financial resources. As a key initiative to strengthen financial support for the real economy, industry–finance collaboration mitigates the negative externalities associated with the unbounded integration of industrial and financial capital on the overall economy. It fosters a healthy cooperative relationship between financial institutions and market entities, contributing to a new paradigm of positive interaction and mutual benefit between industry and finance. This approach effectively addresses information asymmetry and underinvestment in innovation activities.

Therefore, based on the perspective of government intervention, we empirically evaluate the impact of China’s pilot policy on industry–finance integration on corporate innovation at the micro level, thereby filling a gap in the existing literature. We regarded the implementation of the pilot policy as a quasi-natural experiment, and selected A-share listed manufacturing companies from 2012 to 2022 as the sample to conduct an empirical test on the impact of financial support for the real economy on enterprise innovation. The results indicate that the implementation of the Industry–Finance Collaboration pilot policy significantly enhances the innovation level of manufacturing enterprises. Further analysis reveals that this effect is primarily achieved through three channels: reducing information asymmetry, increasing local government fiscal subsidies, and improving corporate access to bank credit. Moreover, the impact is more pronounced in companies facing severe financing constraints, intense market competition, and those of relatively smaller size.

The contributions of this paper are as follows: We investigate the relationship between industry–finance collaboration and corporate innovation, empirically evaluating the policy effects of China’s industry–finance collaboration pilot policy on corporate innovation at the micro level from the perspective of government intervention, thereby adding a new dimension to the existing literature. Furthermore, we extend the Double Machine Learning method to the DID model, enhancing the validity of policy evaluation by mitigating the issue of insufficient estimation accuracy in the DID model. By demonstrating the promoting effect of industry–finance collaboration policies on corporate innovation, we hope our findings can provide insights for fostering internationally competitive real-economy enterprises and building an innovation-oriented nation.

The main contents of this paper are structured as follows:

Section 2 provides a review of relevant literature;

Section 3 discusses the policy background, theoretical analysis, and research hypotheses;

Section 4 elaborates on the research design;

Section 5 presents the analysis of empirical results;

Section 6 delves into further discussions on the mechanisms and heterogeneity;

Section 7 summarizes the research conclusions and proposes corresponding recommendations.

2. Literature Review

Since Arrow’s seminal work, the issues of underinvestment in innovation activities and information asymmetry have garnered widespread attention from both academia and policymakers [

4]. Current research on this topic primarily examines the problem from two perspectives: the market environment and firm-specific characteristics. Regarding the market environment, scholars generally agree that in freely competitive markets, corporate R&D investment tends to fall below the socially optimal level, exhibiting “market failure” [

4].

International evidence further substantiates this market failure hypothesis. Chava et al. (2013) [

7] demonstrate that banking deregulation in the United States significantly boosted innovation output, particularly among young firms, by easing financial constraints. Similarly, Howell (2017) [

8] finds that targeted R&D grants in the U.S. effectively stimulated startup innovation, illustrating how directed financial support can overcome market failures in innovation financing. These international studies provide important comparative perspectives for understanding the mechanisms through which financial interventions affect innovation.

The existing literature mainly conducts analysis from the following aspects:

In terms of the mechanism path, Lin et al. synthesized survey data from over 2000 Chinese companies in 2003 and identified a significant negative correlation between state-owned enterprises, state-appointed managers, and corporate R&D investment through analysis of this data [

9]. Nanda & Nicholas conducted an empirical analysis using a DID model, examining the scale, quality, and novelty of corporate patents before and after bank failures. Their study found that during the Great Depression, bank disruptions significantly affected firms’ technological achievements, indicating that credit market downturns negatively impact corporate innovation [

10]. Aghion et al. argued that product market competition can drive corporate development [

11].

In terms of policy types, to address the underinvestment in innovation caused by market failures, government intervention is often regarded as a necessary solution. R&D subsidies and tax incentives are the most commonly used policy tools by governments worldwide. These measures can lower the cost of innovation and stimulate greater private R&D investment. Bloom et al. argue that a 10% reduction in R&D taxes would lead to at least a 10% increase in R&D expenditure in the long term [

12].

However, the effectiveness of financial policies is not guaranteed. Mugerman et al. (2019) [

13] document a case where financial industry regulation failed to achieve its intended outcomes, reminding us that policy design and implementation matter crucially for success. This cautionary evidence suggests that the effectiveness of industry–finance collaboration policies may depend on specific design features and implementation quality.

In terms of enterprise types, regarding industry–finance collaboration, Lu et al. found that such collaboration can alleviate corporate financing constraints, with this effect being more pronounced in private companies [

14]. Using Taiwanese companies as an example, Lo, S.F. et al. conducted an empirical test employing the DEA model, and the results showed that companies implementing industry–finance collaboration achieved higher economic efficiency compared to those that did not [

15]. Recent China-specific research has produced findings closely related to our study. Xu, Li, and Zheng (2025) [

16] examine China’s industry–finance collaboration pilot with a focus on green innovation, finding that improved access to credit and subsidies drove patent increases. Their work provides a valuable point of comparison.

In recent years, how Industry–Finance Collaboration affects enterprise innovation has become a focus of attention for both the academic community and policymakers. A large number of studies have shown that Industry–Finance Collaboration exerts a profound impact on enterprise innovation activities by alleviating financing constraints of enterprises, guiding resource allocation, and building an innovation ecosystem. Due to its inherent high risks, long cycles, and information asymmetry, enterprise innovation activities often face severe financing constraints. Traditional research on Industry–Finance Collaboration focused on bank credit, while recent literature has revealed the role of diversified financial tools.

Firstly, emerging models such as digital finance and green finance have alleviated the problem of innovative financing through unique mechanisms. Li et al. (2023) demonstrated that the digital economy, by transforming “data” into a tangible element, effectively improved information asymmetry, thereby broadening the financing channels for enterprises, especially for disruptive innovations [

17]. Similarly, Pasupuleti et al. (2025) noted that green strategic alliances, by integrating government subsidies, scientific research talents, and market resources, can significantly enhance the green innovation output of enterprises, and this effect is particularly crucial in regions with underdeveloped financial markets [

18]. Secondly, financial regulatory policies will reshape the innovation collaboration models of enterprises. Luan et al. (2025) discovered that strengthened prudential bank supervision would make riskier innovative projects more inclined to seek sponsorship from state-owned enterprises, revealing how financial policies, through the channel of risk preference, indirectly influence the collaboration networks and resource allocation at the industrial level [

19]. Moreover, micro-financial strategies such as supply chain finance also provide specific solutions for addressing liquidity issues in innovation.

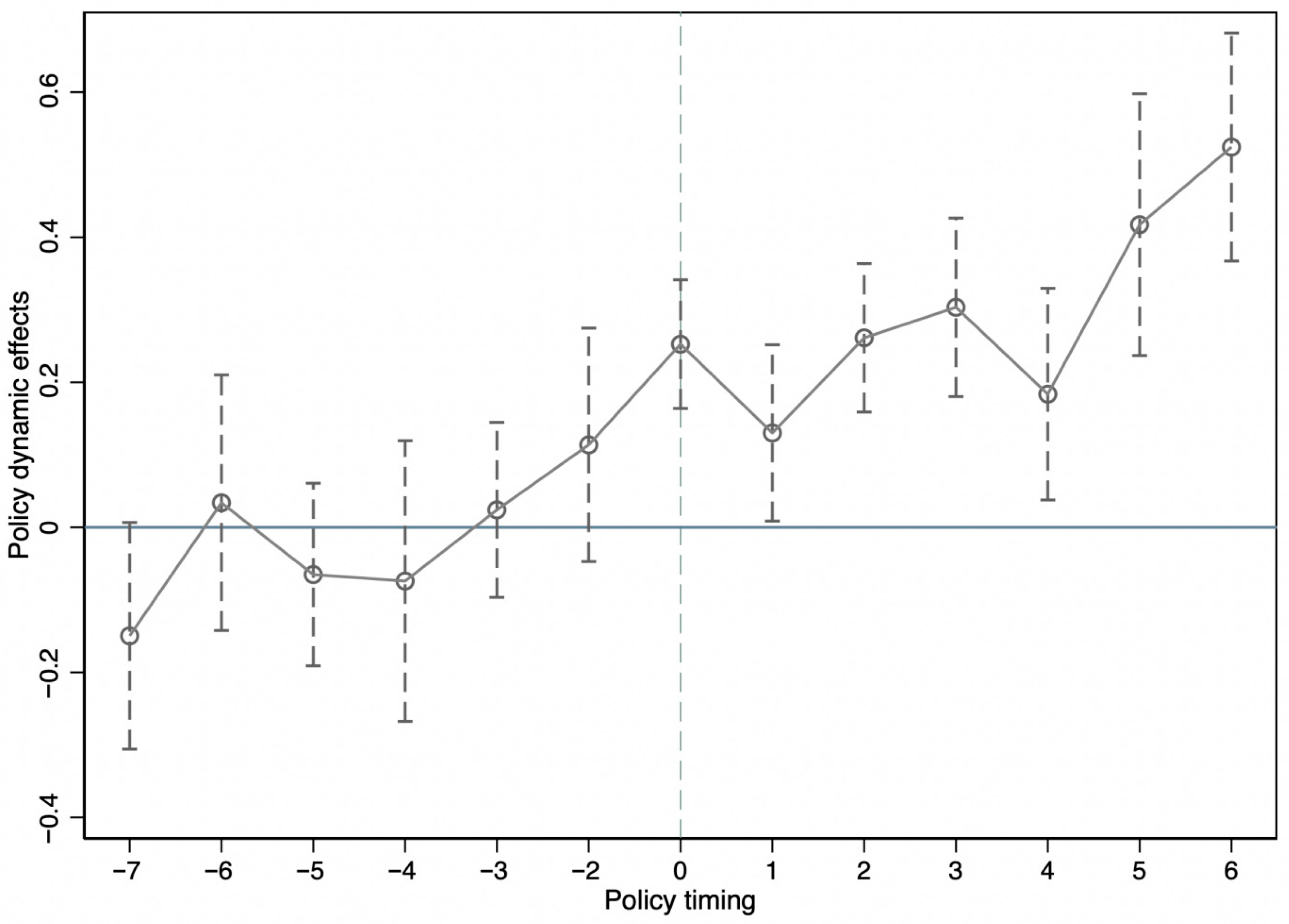

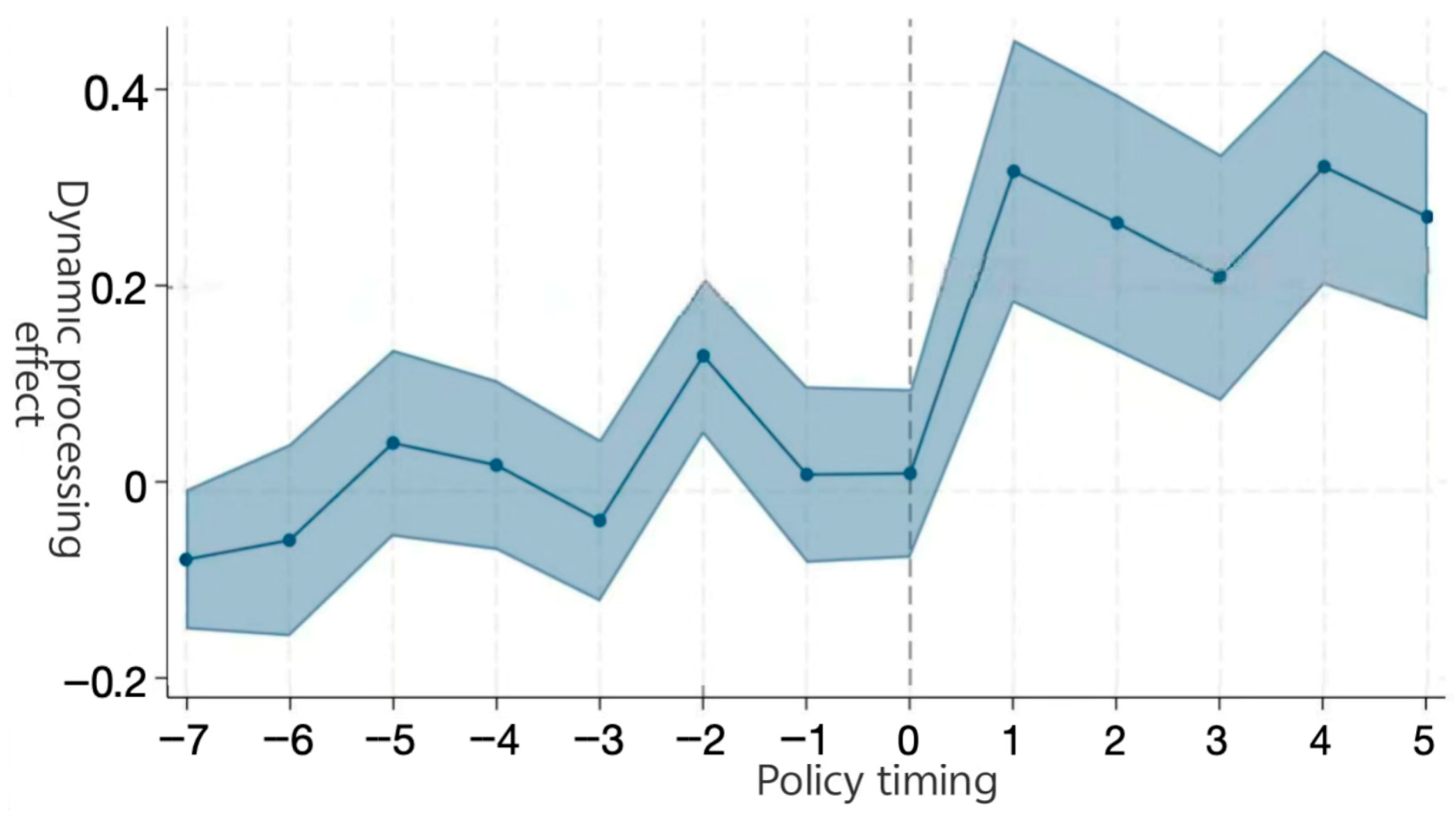

In terms of identification methods, the existing literature predominantly employs the traditional Two-Way Fixed Effects (TWFE) Difference-in-Differences (DID) model to identify policy effects [

20,

21,

22]. However, the DID model is constrained by severe multicollinearity issues, preventing researchers from incorporating numerous influencing factors [

22]. This limitation forces the selection of only a few control variables, significantly increasing the probability of endogeneity due to omitted variable bias. Moreover, traditional parametric regression methods assume a known functional form for the non-core explanatory variables in the DID model. Yet, in real-world economic systems, variable relationships are extremely complex, making simple linear functions inadequate for capturing these dynamics. This often leads to potential misspecification of the linear functional form.

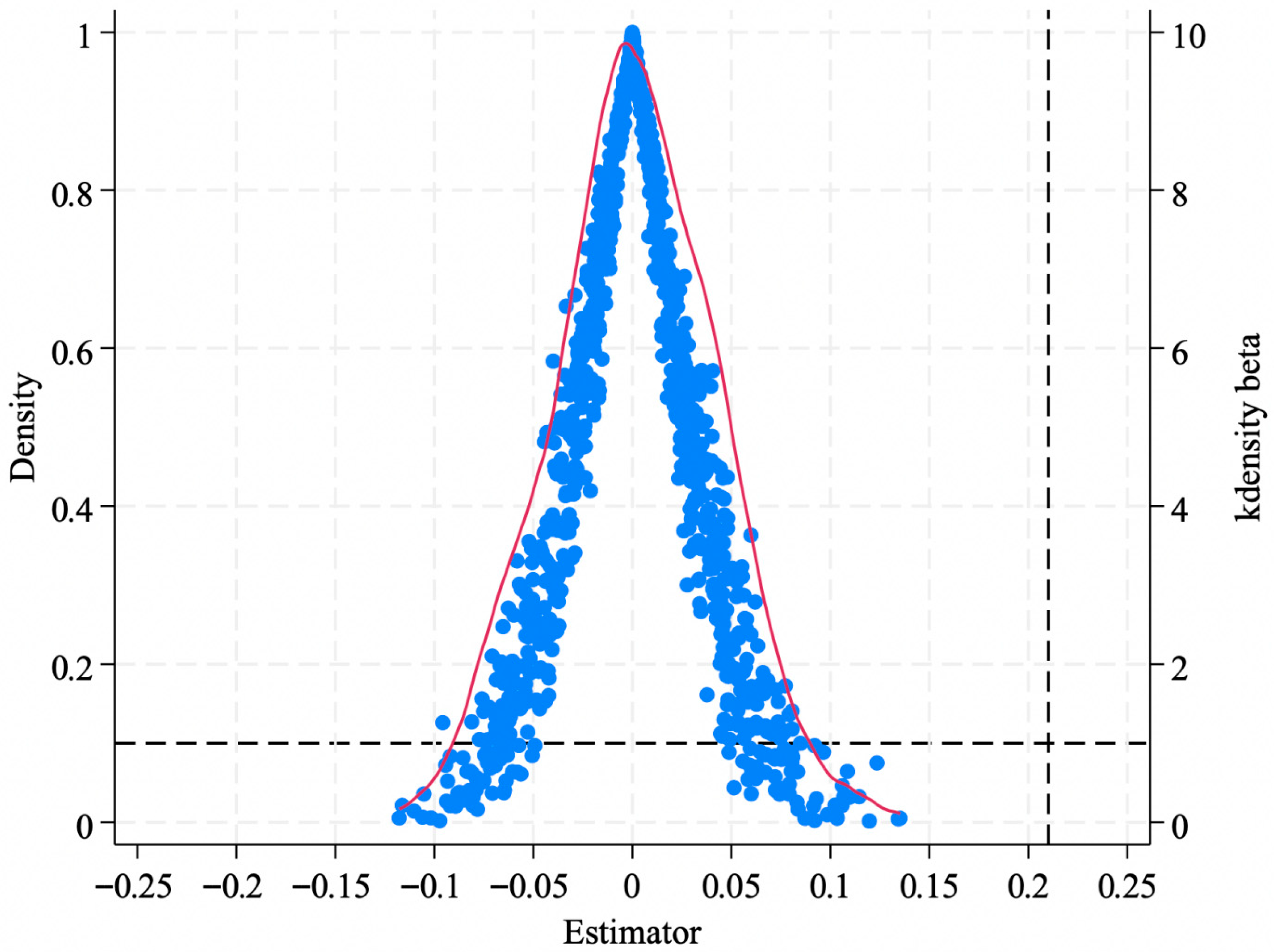

To address the functional form misspecification inherent in traditional parametric methods and the “curse of dimensionality” unresolved by semi-parametric estimation, Chernozhukov et al. utilized Double Machine Learning (DML) to identify the partial effects of explanatory variables of interest on the dependent variable [

23]. By employing machine learning algorithms, high-dimensional explanatory variables can be incorporated into empirical research, thereby overcoming multicollinearity constraints. This approach does not require pre-specifying a concrete functional form, avoiding bias from functional form misspecification.

In the current study, Chang et al. (2024) explored the impact of uncertainty in trade policy effects on corporate innovation investment after controlling for enterprises, industries, and high-dimensional fixed effects [

24]. Chang et al. (2020) theoretically integrated DML with the DID framework. This article provides a strict theoretical basis for the use of the “DML-DID” hybrid model in policy evaluation and is an important guide for the application of this method [

25].

Consequently, we extend the Double Machine Learning method to the DID framework. This allows us to retain the advantages of the Difference-in-Differences model while specifying the non-core explanatory variables in a semi-parametric form and incorporating high-dimensional control variables to the fullest extent. This effectively mitigates estimation accuracy degradation caused by functional form misspecification and omitted variables in the DID model, thereby enhancing the validity of policy evaluation.

Therefore, based on the current research, we can know that the nature of the enterprise and the operating conditions of the bank will have an impact on enterprise innovation. However, there are relatively few studies on the issue of insufficient enterprise innovation investment caused by market failure, and there are also few literature studies on the economic consequences of the industry–finance collaboration policy. Most of the existing research only conducts analysis at the theoretical level. But the economic impact of such policies is still unclear, and there is a lack of a systematic assessment of the impact of industry–finance collaboration policies on the innovation level of enterprises. In terms of research method, although the traditional DID method is widely used to assess policy shocks, its effectiveness heavily relies on the parallel trend assumption and appears weak when dealing with high-dimensional covariates or complex function forms. To overcome these limitations, we embed the DID into the DML framework. It enhances the credibility and accuracy of causal reasoning, providing a new paradigm for handling complex economic intervention issues and thus complementing the existing literature.

To explore whether industrial policies can drive economic development through scientific and technological innovation, we examine corporate innovation levels, thereby partially addressing the practical question of how to effectively promote financial support for the real economy to channel funds into corporate innovation activities.

3. Institutional Background, Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

3.1. Institutional Background of Industrial Integration in China

The term “Industry–Finance Collaboration” derives from “Industry–Finance Integration,” though their concepts are not entirely identical. Industry–finance Integration refers to capital collaboration formed through relational ties such as cross-shareholding and personnel dispatch between industrial capital and financial capital [

26]. In contrast, Industry–Finance Collaboration represents a new cooperative model where mutual reinforcement between industry and finance is achieved without the need for equity-based ties [

27], instead focusing on building institutional connections and information-sharing mechanisms.

“Industry–Finance Collaboration” is a strategic initiative launched by the state to enhance the ability of financial services to support the real economy. Its core lies in promoting the deep integration and virtuous cycle between industries and finance, aiming to achieve this through the establishment of effective institutional mechanisms, and to precisely allocate more financial resources to the key areas and weak links of industries.

In 2016, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) and three other ministries jointly launched the pilot program for industry–finance collaboration, establishing “National Industry–Finance Collaboration Pilot Cities.” The first batch of these pilot cities was announced on December 29 of the same year. In July 2020, MIIT and four other ministries issued the “Notice on Organizing Applications for the Second Batch of Industry–Finance Collaboration Pilot Cities,” and the second batch was announced on 18 December that year.

The policy framework of Industry–Finance Collaboration encompasses several key components:

It establishes a multi-tiered information-sharing system that includes the National Industry–Finance Collaboration Platform as the central hub, complemented by regional and sector-specific sub-platforms. This digital infrastructure collects and analyzes enterprise data, including production, R&D, taxation, and supply chain information, to generate comprehensive corporate credit profiles. These enterprises receive priority credit assessment and specialized financial product support.

The policy promotes financial product innovation specifically tailored for innovative enterprises, including intellectual property pledge financing, supply chain finance, and green credit products. Additionally, the policy facilitates regular matchmaking events between banks and enterprises, establishes specialized credit loan products for technology enterprises, and implements a risk compensation fund mechanism to share potential losses between the government and financial institutions.

The Industry–Finance Collaboration pilot zones were established to enhance financial services’ support for the real economy, accelerate the development of information platforms, and actively innovate financial products and services. The pilot program primarily involves creating financing demand lists for key enterprises and projects, building industry–finance collaboration platforms, facilitating bank-enterprise information matching activities, and establishing information-sharing mechanisms between enterprises and financial institutions through big data and other information technologies. These initiatives aim to improve the efficiency of industry–finance information alignment, promote the concentration of financial resources in the real economy, foster positive interaction between the real industry and the financial sector, and strengthen financial support for the real economy.

On one hand, the Industry–Finance Collaboration policy effectively guides financial institutions to implement differentiated credit policies, directing more financial resources toward green, innovative, efficient, and market-competitive enterprises. This incentivizes companies to strive in these directions, thereby stimulating corporate innovation. On the other hand, Industry–Finance Collaboration encourages financial institutions to allocate more funds to real-economy enterprises, alleviating their financing shortages. Thus, the Industry–Finance Collaboration pilot policy theoretically corrects market failures and demonstrates strong necessity and feasibility in the current context of innovation-driven development.

Table 1 shows the specific cities and implementation years for the pilot policies on industry-finance collaboration.

3.2. Theoretical Analyses

Corporate R&D and innovation activities face challenges such as high investment, significant risks, and long cycles. Consequently, they heavily rely on the efficiency of financial allocation and the robustness of the financial service system. Existing research indicates that in a free market economy, the level of corporate R&D investment tends to fall below the social optimum, a phenomenon characterized as “market failure.” The term “Market Failure” was first introduced by American economist Francis M. Bator in his article “The Anatomy of Market Failure” [

28]. It refers to a situation in which the resource allocation process of a free market, due to inherent flaws or external constraints, fails to achieve Pareto Efficiency—a state where resources cannot be reallocated to make one individual better off without making another worse off. Market failure can be primarily categorized into the following types: externalities, public goods, market power, information asymmetry, and incomplete markets. This framework provides an important theoretical foundation for studying the factors influencing corporate innovation levels.

Based on the theory of market failure, corporate innovation activities—characterized by multiple market imperfections—cannot achieve optimal resource allocation through market mechanisms alone. Consequently, policy guidance and intervention become necessary to ensure sufficient innovation investment and socially optimal levels of innovation. Given the capital’s inherent tendency to seek returns while avoiding risks, financial institutions like banks, as key players in credit channels, maintain stringent risk control standards and impose relatively high credit requirements for corporate innovation funding. When collaboration between industrial sectors and financial institutions remains superficial or becomes disconnected, enterprises face greater challenges in securing financing, including limited funding channels and elevated financing thresholds. Under such circumstances, the optimal allocation of resources between financial capital and corporate innovation cannot be spontaneously achieved through market mechanisms alone. Consequently, this form of “market failure” caused by information asymmetry becomes pervasive. The financing needs of non-state-owned enterprises and small and medium-sized enterprises are particularly difficult to meet, largely due to insufficient policy support and relatively weak credit profiles. As a result, these enterprises often face increasingly severe financing constraints. Challenges such as limited access to financing and high funding costs will inevitably suppress corporate investment in R&D, ultimately hindering the improvement of innovation performance.

Regarding the causes of “market failure” in corporate innovation activities, Arrow approached the issue from the perspective of innovation financing difficulties, contending that underinvestment in innovation results from the high costs of external R&D financing caused by information asymmetry and moral hazard [

29]. The problem of elevated external financing costs stemming from information asymmetry and moral hazard constitutes a major obstacle to corporate innovation.

Unlike previous unilateral policies that primarily relied on fiscal subsidies or financial institutions, the Industry–Finance Collaboration policy emphasizes two-way integration. It enhances the frequency and level of collaboration between industrial and financial sectors through financial innovation, technology spillovers, and market competition, thereby ultimately boosting corporate innovation capabilities. Following the implementation of the Industry–Finance Collaboration pilot policy, it helps further enhance the financial sector’s capacity to serve the real economy and overcome previous challenges of insufficient coordination between financial institutions and industrial sectors. Consequently, enterprises gain access to diversified financing channels. Thus, we argue that the pilot policy alleviates the “market failure” in corporate innovation activities by expanding credit sources and financing methods for innovation initiatives, reducing financing costs, and improving both financing efficiency and credit allocation efficiency.

3.3. Research Hypotheses

3.3.1. Industry–Finance Collaboration and Enterprise Innovation

Based on theoretical analysis, we posit that the Industry–Finance Collaboration policy influences corporate innovation levels by mitigating the “market failure” present in innovation activities. This is manifested in the following aspects: First, the pilot policy encourages the establishment of industry–finance collaboration platforms to enhance information sharing. Utilizing information technologies such as big data and cloud computing, participants in the financing process can create service platforms for industry–finance information alignment. These platforms not only enable efficient and rapid information communication but also significantly expand the scope of financial services. The generation of online credit reduces moral hazard post-lending and improves financial institutions’ risk resilience. The resultant reduction in financial service costs strengthens the willingness for continued collaboration between both parties. Second, the policy promotes the development of effective interactive models among stakeholders. It facilitates the creation of financing information alignment lists for key enterprises or projects, helping financial institutions accurately and swiftly identify corresponding financing needs. Furthermore, it advocates for differentiated lending strategies and targeted support, ensuring substantial improvements in the service capabilities of financial institutions. Finally, the policy requires financial institutions to actively enhance supply chain financial services and innovate financial products and services. This includes developing new loan products, promoting accounts receivable and intellectual property pledge financing, and providing innovative credit services such as energy efficiency loans, green credits, and carbon emission rights trading. Thus, the diversification of credit sources and financing methods driven by the implementation of the Industry–Finance Collaboration pilot policy provides new momentum for reducing corporate financing costs, improving financing efficiency, optimizing credit allocation, and ultimately enhancing corporate innovation capabilities.

Based on the above theoretical analyses, we propose Hypothesis 1:

H1: Industry–Finance Collaboration improves the innovation level of listed enterprises.

3.3.2. Information Transfer Mechanisms

Widespread information asymmetry within and outside the firm creates adverse selection problems in the credit market, which raises the cost of external financing for these firms [

30]. In turn, external financing will have a greater impact on corporate innovation [

31]. Enterprises can use different financing methods such as bank loans, equity financing, bond financing, commercial credit financing or financial leasing to raise funds for innovation according to their own financial needs, which in turn improves the efficiency of credit resource allocation. The problem of information asymmetry not only increases the difficulty for investors to accurately predict the future earnings of enterprises but also results in the underestimation of the value of innovative activities, which in turn weakens the innovation drive of enterprises. At the same time, it also prompts creditors and other stakeholders to adopt adverse selection strategies, forcing enterprises to reduce or abandon investment in innovation [

32]. In contrast, the construction of China’s pilot cities for Industry–Finance Collaboration builds a platform for Industry–Finance Collaboration. The platform publishes information on the financing needs of enterprises after reviewing them in accordance with regulations, which enhances the role of the information in guiding financial institutions to provide funding. This flow and sharing of financial service information can also help alleviate information asymmetry between financial institutions and enterprises, reduce transaction costs in the process of matching financing and innovation, and improve the availability of credit to enterprises, which in turn will increase their motivation to innovate. The function of this platform is similar to a trusted “signal transmission” and “authentication” mechanism. The platform regulates and reviews the financing demands of enterprises. This act itself is like a pre-screening and guarantee of the quality of enterprises, sending a positive signal about the credibility of enterprises to the market. This can effectively alleviate the aforementioned “adverse selection” problem. Financial institutions can obtain more reliable information through the platform, thus being more courageous to provide financing for light-asset enterprises that have good innovation potential but lack tangible collateral. This not only improves the allocation efficiency of credit resources, but more importantly, it changes the innovation budget constraints of enterprises, enabling the restart of those innovative projects that were once suppressed due to financing constraints, especially those exploratory R&D projects that represent long-term competitiveness. Therefore, the construction of pilot cities for Financial–Industrial Integration in China can improve the level of enterprise innovation by reducing the degree of information asymmetry among enterprises.

Based on the above theoretical analyses, we propose Hypothesis 2:

H2: Industry–Finance Collaboration improves the innovation level of listed enterprises by reducing the degree of information asymmetry of the companies.

3.3.3. Government Subsidy Mechanisms

The construction of national pilot cities for industry–finance collaboration encourages local governments to use financial funds as a guide to increase the financing support of financial institutions to enterprises, which will also have an impact on the innovation behaviour of enterprises. Considering the strong positive externality of R&D activities, enterprises cannot enjoy the full surplus of R&D activities [

4], which ultimately leads to the actual level of R&D inputs of enterprises being much lower than the optimal level of R&D inputs required by society [

33]. In contrast, financial subsidies, as a direct incentive, can not only promote enterprise innovation by increasing enterprise cash flow, but also promote enterprises to increase their R&D investment by increasing the marginal benefit of successful R&D or reducing the marginal cost of failed R&D. More importantly, the construction of national pilot cities for industry–finance collaboration has increased the financing support of financial institutions to enterprises by playing the role of guiding financial funds, so that enterprises can obtain more exogenous financing. Under this model, the function of government fiscal funds has been upgraded from “direct subsidies” to “credit enhancement” and “risk compensation”. For instance, by establishing a government risk compensation fund, providing loan interest subsidies, or offering a certain proportion of compensation for bad debts incurred by financial institutions in providing loans to specific industries, the government has effectively shared the credit risks of financial institutions. This has changed the risk–return assessment model of financial institutions for loans to innovative enterprises, encouraging them to relax loan conditions and increase credit quotas. This “government-guided and market-followed” collaborative financing model provides enterprises with a more sustainable and larger-scale source of innovative funds than simple subsidies. It is not difficult to conclude that the construction of national pilot cities for industrial integration can guide banks and other financial institutions to support the development of key industries in the region by leveraging financial funds, provide stable sources of funds for enterprise innovation, and alleviate the problem of insufficient funds in the process of enterprise innovation.

Based on the above theoretical analyses, we propose Hypothesis 3:

H3: Industry–finance collaboration improves the innovation level of listed enterprises by playing the guiding role of financial funds.

3.3.4. Bank Credit Availability Mechanism

The implementation of the industry–finance collaboration policy enables banks to obtain more information about enterprises. The formal or informal activities of enterprises seeking communication with banks will decrease, and the transaction cost of loans will also be reduced as a result [

34]. Compared with general investment activities, the characteristics of R&D and innovation with a long cycle and high uncertainty will significantly inhibit enterprises from obtaining financing through normal channels, and easily suffer from the shortage of exogenous financing [

6], which makes financing constraints become a ‘roadblock’ for enterprise innovation. On the other hand, a continuous credit supply and a relaxed financing environment can promote enterprise innovation [

35]. Bank credit is an important source for enterprises to obtain stable and continuous external funds, which can effectively promote enterprise innovation. The construction of national pilot cities for industry–finance collaboration clearly proposes to establish a multi-sectoral work coordination and information sharing mechanism, recommend key enterprises with large financing needs to financial institutions in a classified manner, and actively promote bank-enterprise docking in a variety of ways, such as financing fairs, so as to reduce the degree of information asymmetry between banks and enterprises while increasing the availability of bank credit to enterprises and providing stable sources of funds for innovation. Its promoting mechanism lies in the fact that the improved availability of bank credit provides enterprises with indispensable “patient capital”. A loan from a reputable bank itself is a strong “certification effect”, sending a positive signal to other market participants (such as suppliers, customers, and other investors) that the enterprise is operating stably and has a promising future. This helps the enterprise further obtain commercial credit and equity financing, forming a virtuous capital cycle that supports innovation.

Based on the above theoretical analyses, we propose Hypothesis 4:

H4: Industry–finance collaboration increases the level of innovation of listed enterprises by increasing the availability of bank credit to firms and thus increasing the level of innovation.

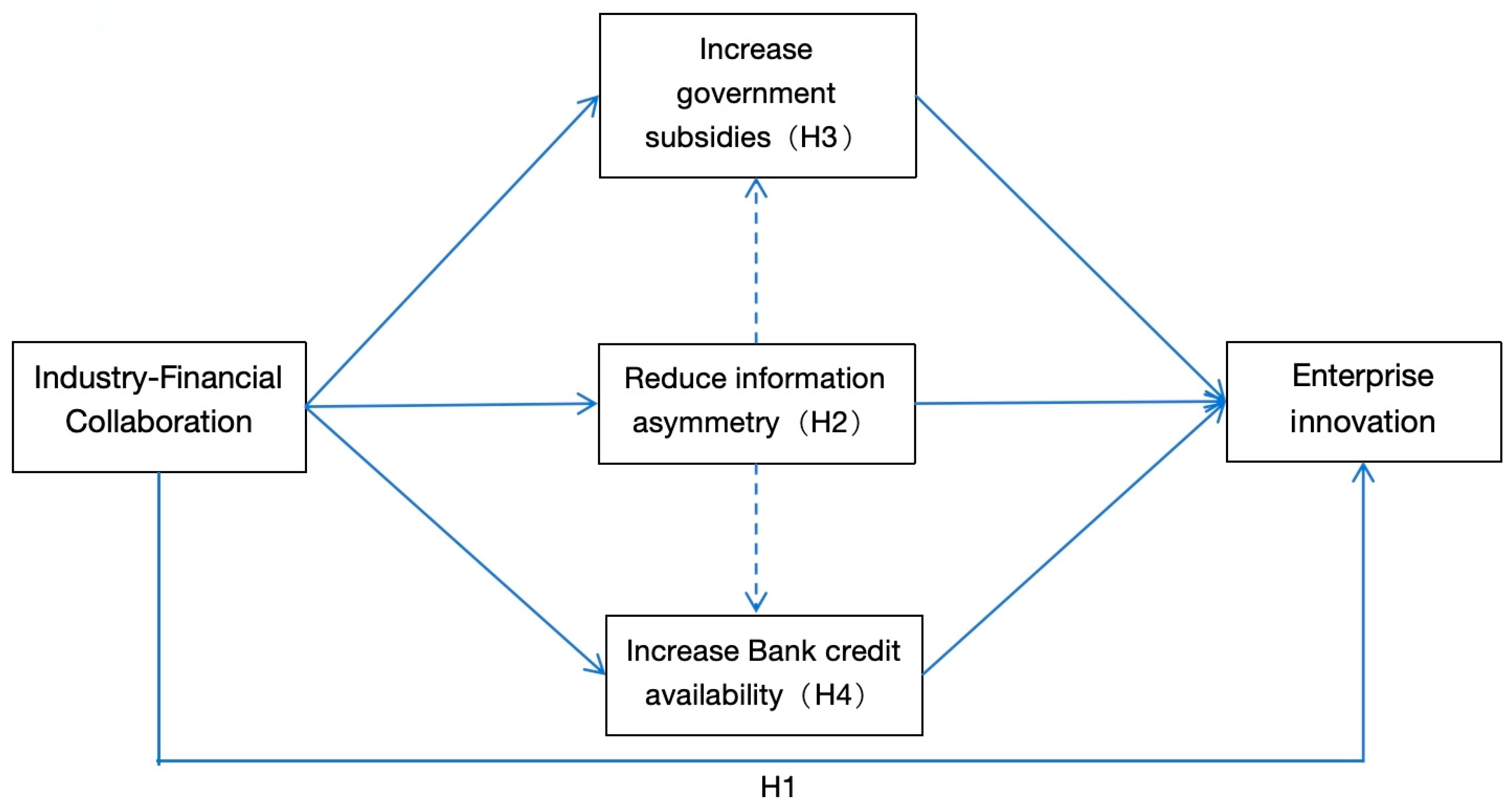

These three mechanisms operate within a comprehensive theoretical framework, with the reduction in information asymmetry providing the necessary foundation. By establishing formal channels for information sharing, this policy enables financial institutions to better identify feasible innovative projects and the government to make more targeted subsidy decisions. This information infrastructure thus enhances the efficiency of fiscal fund allocation and the effectiveness of bank credit allocation, generating synergy effects and jointly addressing different aspects of market failure in innovative financing. The specific theoretical framework diagram is shown in

Figure 1.

7. Suggestions

Based on the above analysis, we put forward the following suggestions:

Building an efficient industry–finance collaboration ecosystem. Creating a market environment where financial resources can effectively flow to and serve the real economy is crucial for driving corporate innovation to achieve both “scale expansion” and “quality leap.” By enhancing the capacity to serve the real economy, we can more effectively meet customers’ diverse and personalized financing needs, collectively fostering a fair, efficient, and sustainable financial service ecosystem, thereby avoiding the “shift from real to virtual” of financial resources and the “Matthew effect.”

Government departments should strengthen guidance and implement targeted policies. Institutional design should focus on “quality”—while continuously promoting financial services to support the real economy, efforts should simultaneously strengthen institutional design, making the enhancement of “quality” in corporate innovation activities a core policy objective. Precise assessment and support tailored to local conditions and enterprises are essential to scientifically and dynamically evaluate the actual innovation incentive effects of the industry–finance collaboration pilot policy, considering the alignment between regional financial service supply capacity and the structural characteristics of dominant industries. Effective screening and evaluation mechanisms should be established to accurately identify and prioritize high-quality enterprises with genuine innovation capabilities and development potential, thereby optimizing the allocation of fiscal resources. Services and coordination mechanisms should be optimized by improving fiscal and tax support systems and building comprehensive industry–finance information exchange and public service platforms, effectively reducing corporate financing thresholds and costs and providing more convenient and high-quality financial services to broaden external financing channels and efficiently raise R&D funds. This will deepen industry–finance collaboration and enhance the effectiveness and precision of financial support for real economic development.

At the enterprise level, companies should proactively adapt and continuously optimize their relevant strategies. Enterprises need to systematically assess their heterogeneous characteristics, such as the degree of financing constraints they face, their competitive position in the industry, and their core advantages, while closely monitoring the latest developments and implementation details of national and local industry–finance collaboration pilot policies. Optimize Financing and Vigorously Promote Innovation: Based on the evaluation results, enterprises should promptly adjust and optimize their financing strategies, actively explore and fully utilize diversified external financing channels, including venture capital, bond markets, and intellectual property pledge financing, to provide solid financial support for sustaining high-quality innovation activities with market competitiveness.

Our findings suggest distinct strategic priorities for different firms: SMEs should leverage policy support to address information asymmetry by actively participating in credit rating systems and utilizing public information platforms. Large enterprises should focus on accessing specialized innovation syndicates and outcome-based subsidies for breakthrough innovations. Firms in highly competitive markets should prioritize rapid innovation iteration using short-term R&D financing, while those in less competitive environments should combine financial strategies with organizational innovation to overcome inertia.

Financial institutions should play a central role in balancing risk and innovation. As key entities implementing the industry–finance collaboration policy, financial institutions must actively embrace fintech—such as big data risk control, artificial intelligence, and blockchain—while maintaining a sound risk management framework to deepen service innovation. They should vigorously promote the iterative innovation of financial products and service models, enhancing the coverage, precision, and efficiency of financial services for real-economy enterprises, particularly for long-tail customer segments such as small and medium-sized enterprises and specialized, sophisticated, distinctive, and innovative enterprises.

Financial institutions should develop differentiated service models based on our heterogeneity findings: for SMEs, create specialized assessment mechanisms incorporating alternative data; for innovation-intensive firms, establish fast-track approval processes and patent evaluation standards; for firms in competitive markets, offer real-time financing for rapid innovation. Additionally, they should implement dynamic risk pricing models that reflect firms’ innovation potential rather than relying solely on traditional financial metrics.

9. Discussion

Our findings resonate broadly with global research on how the integration of the financial and real sectors fosters innovation. First, regarding the central role of information asymmetry, our results align closely with conclusions drawn from studies in developed economies. In terms of the role of government subsidies, our conclusions share common ground with international research while also revealing thought-provoking differences. The consensus lies in the positive leveraging effect of government R&D subsidies on corporate innovation, which has been confirmed in multiple economies such as the United States and the European Union. However, as demonstrated by Howell (2017) [

8] in their Research Policy study on the U.S. ARPA-E program, subsidies there are more focused on high-risk, high-potential early-stage technologies and are allocated through rigorous peer review. In contrast, subsidies within China’s industry–finance collaboration policy may place greater emphasis on broadly “clearing” financing obstacles for corporate innovation by guiding financial resources. This divergence may stem from differing roles of government and the market across developmental stages and economic systems, reminding us that policy effectiveness is highly dependent on its alignment with the local institutional environment. Concerning the role of bank credit, Ayyagari et al. (2011) [

35] found that bank financing is the most important external source for firm growth and innovation. Yet, it must be noted that this reliance can be a double-edged sword. When the banking system itself is strongly influenced by factors such as industrial policies or administrative guidance, credit allocation may not be entirely based on commercial efficiency principles, potentially fostering moral hazard or resource misallocation, which constitutes a potential regional systemic factor in China.

While the Industry–Finance Collaboration policy is implemented in the specific institutional context of China, its core mechanisms offer valuable insights for international policy design, particularly for emerging economies. The triad of information symmetry enhancement, guided fiscal subsidies, and improved bank credit allocation constitutes a replicable policy toolkit for governments seeking to overcome chronic market failures in innovation financing.

In terms of research methods, the cities (districts) selected as pilot areas usually have an inherent advantage over non-pilot regions in terms of industrial foundation, government governance capacity, or financial ecological environment. These inherent regional characteristics themselves may be related to high innovation. Although our model captures these features as much as possible through urban fixed effects and control variables, the problem of residual variable omissions may still cause upward bias in our estimates. Therefore, our interpretation of policy effects should be regarded as a “strong correlation” after controlling for the variables we can observe, rather than an absolute causal relationship. Future research can attempt to seek out more exogenous instrumental variables or conduct in-depth case studies on the micro-mechanisms in the policy implementation process to further strengthen causal inference.