Easy to Know, Hard to Act: How Do Green Attribute Centrality, Environmental Concern, and Trust Exert a Chain Effect on Purchase Decisions?

Abstract

1. Introduction

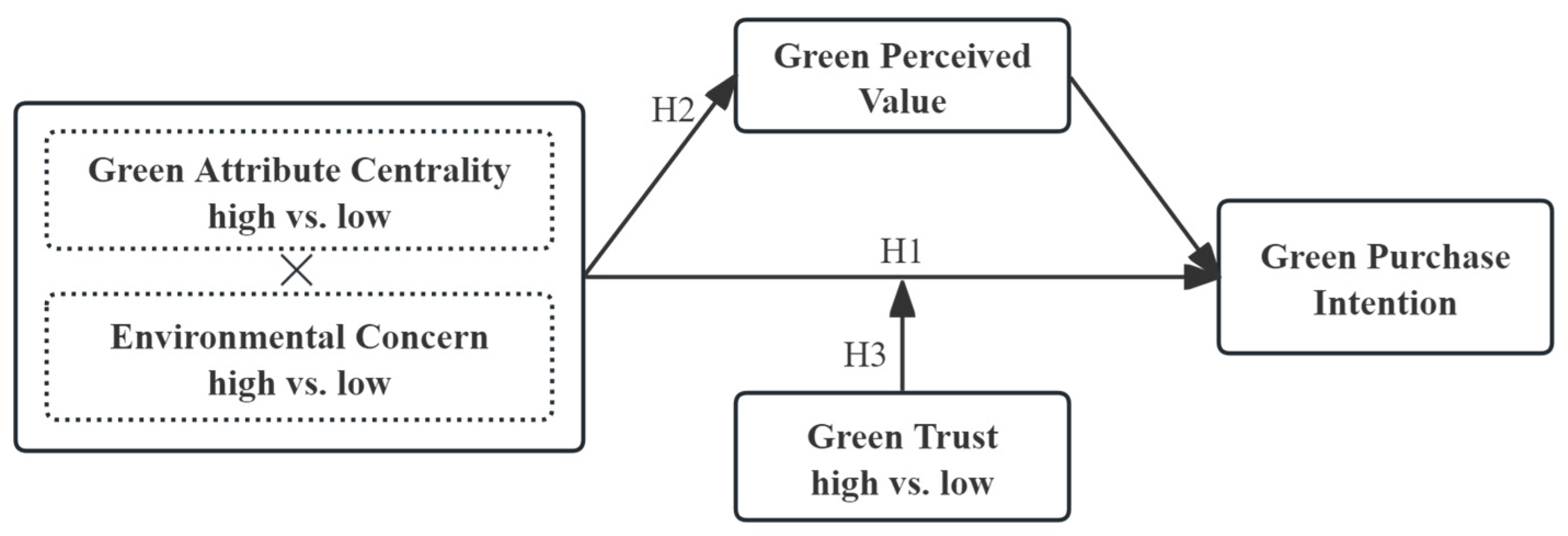

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. GAC, EC and GPI

2.2. The Mediating Role of GPV

2.3. The Moderating Role of GT

3. Research Design and Results Analysis

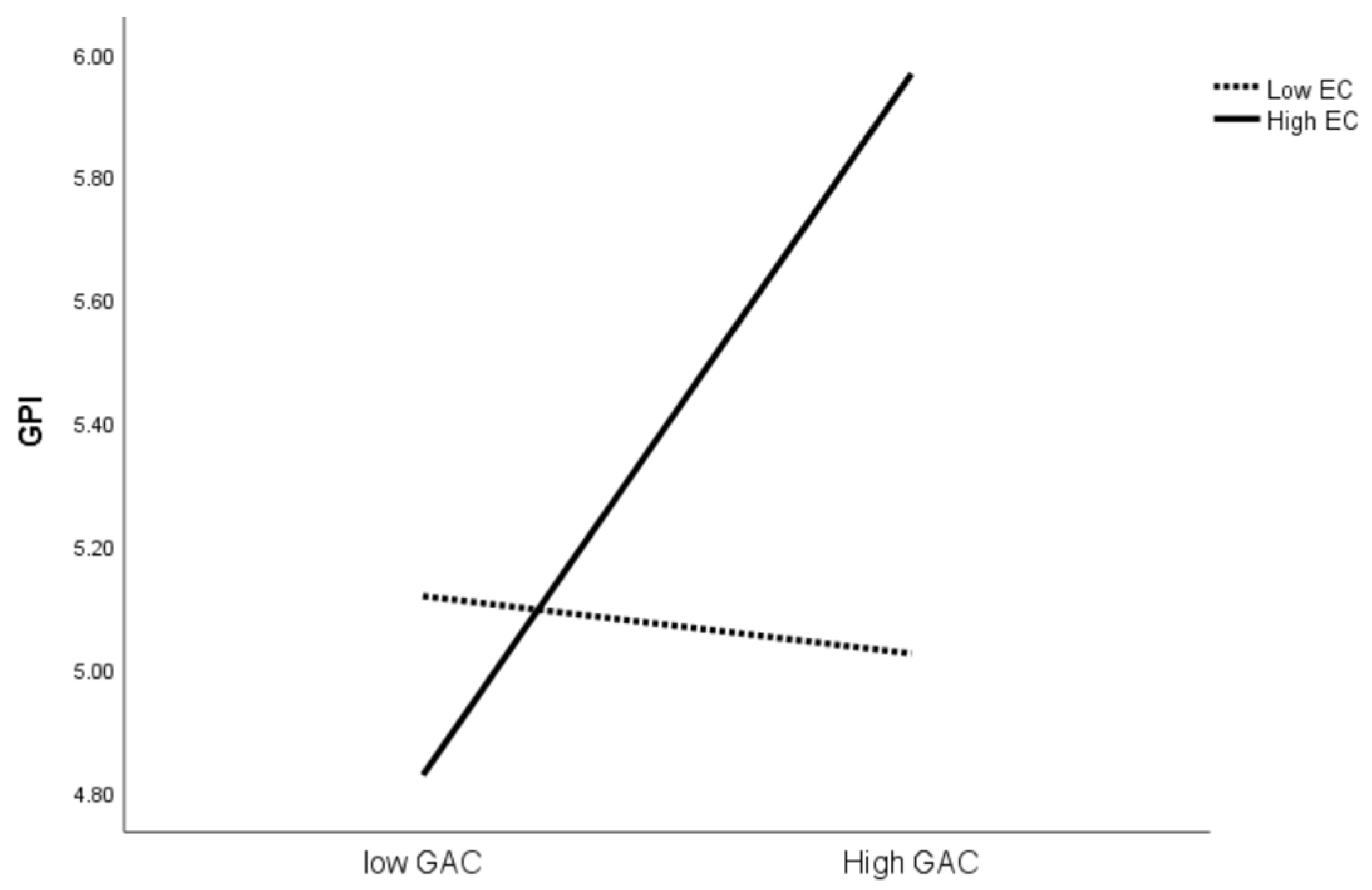

3.1. Study 1: The Interactive Effect of GAC and EC on GPI

3.1.1. Study Design and Procedure

3.1.2. Study Results

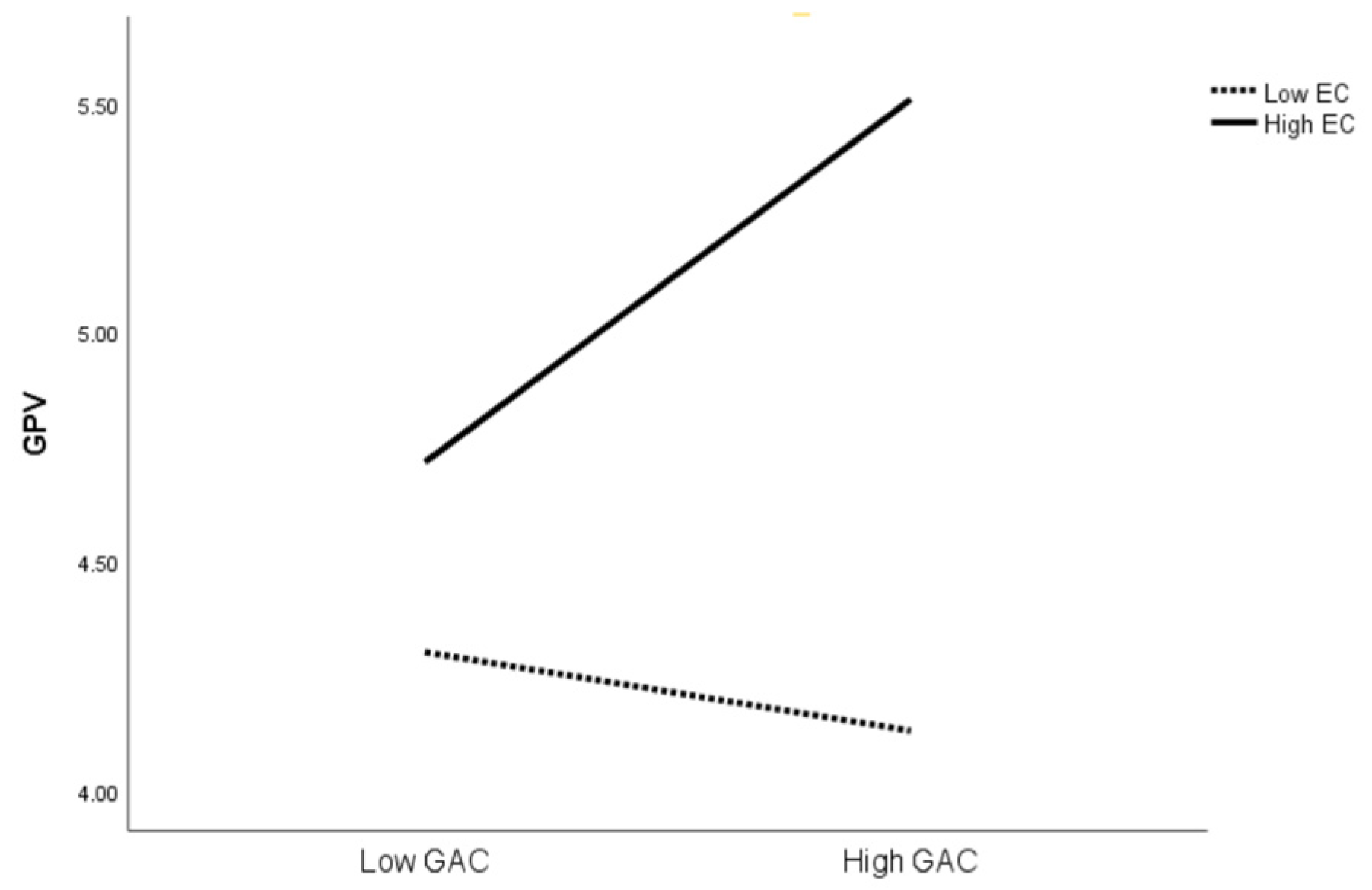

3.2. Study 2: The Mediating Role of GPV

3.2.1. Study Procedure

3.2.2. Results Analysis

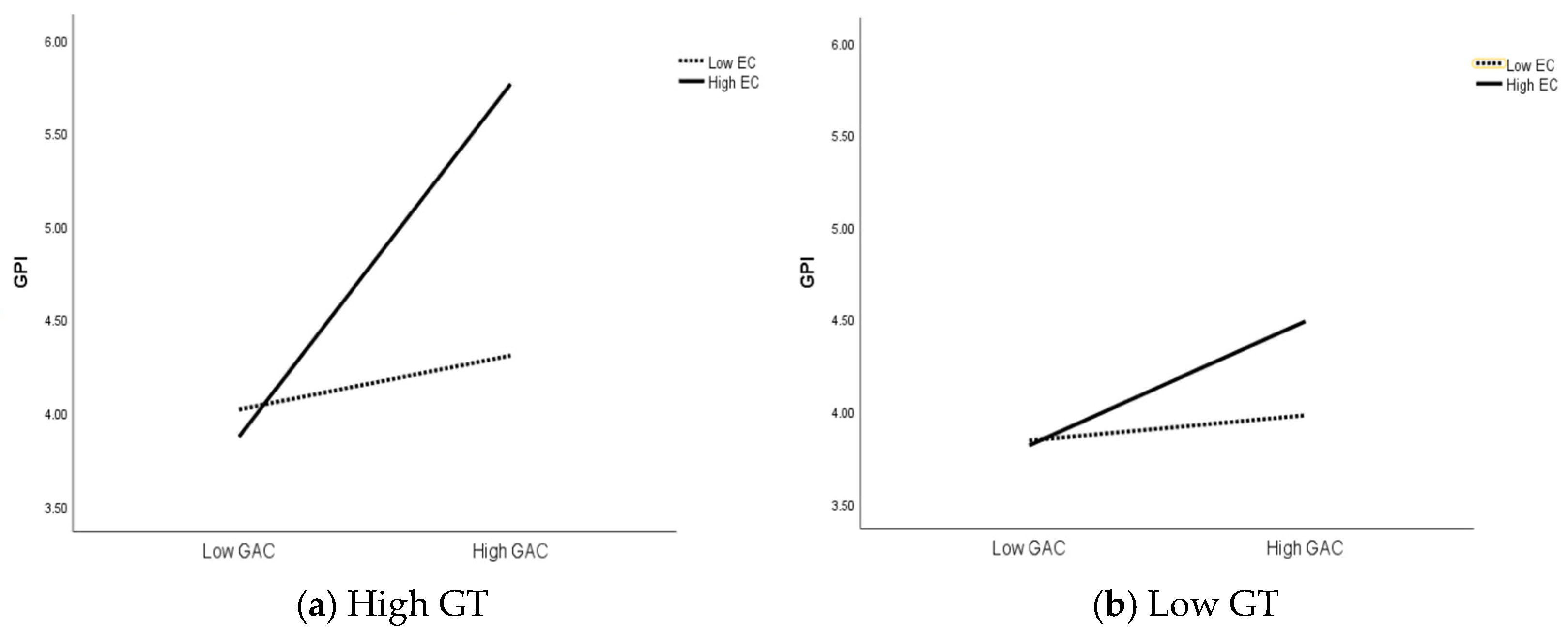

3.3. Study 3: The Moderating Role of GT

3.3.1. Study Design and Procedure

3.3.2. Results Analysis

4. Research Conclusions and Discussion

5. Theoretical Contribution and Managerial Implications

5.1. Theoretical Contribution

5.2. Managerial Implications

6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GAC | Green Attribute Centrality |

| EC | Environmental Concern |

| GT | Green Trust |

| GPV | Green Perceived Value |

| GPI | Green Purchase Intention |

References

- Li, X.; Du, J.; Long, H. Theoretical framework and formation mechanism of the green development system model in China. Environ. Dev. 2019, 32, 100465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almond, R.E.; Grooten, M.; Peterson, T. An SOS for Nature. In Living Planet Report 2020-Bending the Curve of Biodiversity Loss; World Wildlife Fund: Gland, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 10. [Google Scholar]

- Creutzig, F.; Roy, J.; Minx, J. Demand-side climate change mitigation: Where do we stand and where do we go? Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 040201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, M.; Wang, P.; Kuah, A.T. Why wouldn’t green appeal drive purchase intention? Moderation effects of consumption values in the UK and China. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 122, 713–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabio, R.A.; Croce, A.; Calabrese, C. Bridging the Green Attitude–Behavior Gap. J. Sustain. Res. 2025, 7, e250059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Medeiros, J.F.; Ribeiro, J.L.D. Environmentally sustainable innovation: Expected attributes in the purchase of green products. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcon, A.; Ribeiro, J.L.D.; Dangelico, R.M.; de Medeiros, J.F.; Marcon, É. Exploring green product attributes and their effect on consumer behaviour: A systematic review. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 32, 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, Y.; Uniyal, D.P.; Sangroya, D. Investigating consumers’ green purchase intention: Examining the role of economic value, emotional value and perceived marketplace influence. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 328, 129638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooi, L.W.; Liu, M.S.; Lin, J.J. Green human resource management and green organizational citizenship behavior: Do green culture and green values matter? Int. J. Manpow. 2022, 43, 763–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backer, S.; Prasanth, A.P. Influence of locus of control on green buyer behaviour: Mediating role of motivation and the moderating role of health consciousness. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2024. Preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junsheng, H.; Masud, M.M.; Akhtar, R.; Rana, M.S. The mediating role of employees’ green motivation between exploratory factors and green behaviour in the Malaysian food industry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Dayal, R. Drivers of green purchase intentions: Green self-efficacy and perceived consumer effectiveness. Glob. J. Enterp. Inf. Syst. 2016, 8, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rausch, T.M.; Baier, D.; Wening, S. Does sustainability really matter to consumers? Assessing the importance of online shop and apparel product attributes. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 63, 102681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skard, S.; Jorgensen, S.; Pedersen, L.J.T. When is Sustainability a Liability, and When Is It an Asset? Quality Inferences for Core and Peripheral Attributes. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 173, 109–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga Junior, S.; Martínez, M.P.; Correa, C.M.; Moura-Leite, R.C.; Da Silva, D. Greenwashing effect, attitudes, and beliefs in green consumption. RAUSP Manag. J. 2019, 54, 226–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabbir Husain, R.V. Green offering: More the centrality, greater the scepticism. Int. Rev. Public Nonprofit Mark. 2022, 19, 819–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünal, U.; Bağcı, R.B.; Taşçıoğlu, M. The perfect combination to win the competition: Bringing sustainability and customer experience together. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 4806–4824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R.L.; Strubbe, D.; Dallimer, M.; Davies, Z.G.; Davis, A.J.; Edelaar, P.; Groombridge, J.; Jackson, H.A.; Menchetti, M.; Mori, E.; et al. Assessing the ecological and societal impacts of alien parrots in Europe using a transparent and inclusive evidence-mapping scheme. NeoBiota 2019, 48, 45–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabio, R.A.; Croce, A.; Calabrese, C. Construction and psychometric properties of the sustainable behavior questionnaire among Italian adults. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 4374–4384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabio, R.A.; Marcuzzo, A.; Calabrese, C. Cognitive load and peace attitude influence cooperative choices in the iterated prisoner’s dilemma game. Psychol. Rep. 2025, 128, 986–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalanon, P.; Chen, J.S.; Le, T.T.Y. “Why do we buy green products?” An extended theory of the planned behavior model for green product purchase behavior. Sustainability 2022, 14, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.U.; Atlas, F.; Arshad, M.Z.; Akhtar, S.; Khan, F. Signaling green: Impact of green product attributes on consumers trust and the mediating role of green marketing. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 790272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangelico, R.M.; Pujari, D.; Pontrandolfo, P. Green product innovation in manufacturing firms: A sustainability-oriented dynamic capability perspective. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 490–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltenbrand, B.; Foerstl, K.; Azadegan, A.; Lindeman, K. See what we want to see? The effects of managerial experience on corporate green investments. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 150, 1129–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershoff, A.D.; Frels, J.K. What makes it green? The role of centrality of green attributes in evaluations of the greenness of products. J. Mark. 2015, 79, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Sun, X.; Wang, J.; Su, W.; Li, G. Factors affecting green purchase intention: A perspective of ethical decision making. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenis, N.D.; van Herpen, E.; van der Lans, I.A.; van Trijp, H.C. Partially green, wholly deceptive? How consumers respond to (in) consistently sustainable packaged products in the presence of sustainability claims. J. Advert. 2023, 52, 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, S.; Sheng, G.H. The influencing mechanism of the centrality of green attributes on consumer purchase intention: The moderating role of product type and the mediating effect of perceived benefit. Commer. Econ. Manag. 2021, 41, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Foropon, C. Green product attributes and green purchase behavior: A theory of planned behavior perspective with implications for circular economy. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 1018–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuti, D.; Pizzetti, M.; Dolnicar, S. When sustainability backfires: A review on the unintended negative side-effects of product and service sustainability on consumer behavior. Psychol. Mark. 2022, 39, 1933–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickart, B.A.; Ruth, J.A. Green eco-seals and advertising persuasion. In Green Advertising and the Reluctant. Consum. J. Advert. 2012, 41, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Lin, L.M. Exploring attitude–behavior gap in sustainable consumption: Comparison of recycled and upcycled fashion products. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. Opportunities for green marketing: Young consumers. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2008, 26, 573–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagher, G.K.; Itani, O. Factors influencing green purchasing behaviour: Empirical evidence from the Lebanese consumers. J. Consum. Behav. 2014, 13, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, J.D.; Tsarenko, Y.; Ferraro, C.; Sands, S. Environmental concern and environmental purchase intentions: The mediating role of learning strategy. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1974–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmuck, D.; Matthes, J.; Naderer, B. Misleading consumers with green advertising? An affect–reason–involvement account of greenwashing effects in environmental advertising. J. Advert. 2018, 47, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Luz, V.V.; Mantovani, D.; Nepomuceno, M.V. Matching green messages with brand positioning to improve brand evaluation. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 119, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.G.; Duan, S.L. The impact of environmental responsibility on consumers’ green purchase behavior: The chain multiple mediating effect of green self-efficacy and green perceived value. J. Nanjing Univ. Technol. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2022, 21, 48–60. [Google Scholar]

- Jalu, G.; Dasalegn, G.; Japee, G.; Tangl, A.; Boros, A. Investigating the effect of green brand innovation and green perceived value on green brand loyalty: Examining the moderating role of green knowledge. Sustainability 2024, 16, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Lobo, A.; Leckie, C. The role of benefits and transparency in shaping consumers’ green perceived value, self-brand connection and brand loyalty. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 35, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Sun, X. The impact of green brand crises on green brand trust: An empirical study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.Y.; Lu, C.C. Exploring the relationships of green perceived value, the diffusion of innovations, and the technology acceptance model of green transportation. Transp. J. 2016, 55, 51–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.H.; Duan, S.; Zhang, C.; Qiu, Q. Repeat purchase intention for green products: The moderating role of advertising appeal. Soft Sci. 2018, 32, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.L.; Yu, W.P. The formation mechanism of consumers’ green purchase intention: The role of advertising goal framing and regulatory focus. J. Nanjing Univ. Technol. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2021, 20, 87–98, 112. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.; Lai, X.; Yu, C. Switching intent of disruptive green products: The roles of comparative economic value and green trust. Front. Energy Res. 2021, 9, 764581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román-Augusto, J.A.; Garrido-Lecca-Vera, C.; Lodeiros-Zubiria, M.L.; Mauricio-Andia, M. Green marketing: Drivers in the process of buying green products—The role of green satisfaction, green trust, green WOM and green perceived value. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Long, R. How do perceptions of information usefulness and green trust influence intentions toward eco-friendly purchases in a social media context? Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1429454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, G.H.; Lin, Z.N. The influencing mechanism of corporate-environmental cause fit types on consumers’ purchase intention. Acta Acad. Manag. Sin. 2018, 18, 726. [Google Scholar]

- Wasaya, A.; Saleem, M.A.; Ahmad, J.; Nazam, M.; Khan, M.M.A.; Ishfaq, M. Impact of green trust and green perceived quality on green purchase intentions: A moderation study. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 13418–13435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, G.H.; Gong, S.Y.; Ge, W.D. The impact of brand green extension on consumer response: The matching effect of green extension type and thinking style. Foreign Econ. Manag. 2019, 41, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, C.Z.; Chang, T.W. Have I purchased the right product? Consumer behavior under corporate greenwash behavior. J. Consum. Behav. 2024, 23, 1102–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.G. Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, A.C.H.; Wu, H.H. How should green messages be framed: Single or double? Sustainability 2020, 12, 4257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagiaslis, A.; Krontalis, A.K. Green consumption behavior antecedents: Environmental concern, knowledge, and beliefs. Psychol. Mark. 2014, 31, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J. The role of design innovation in facilitating high-end product development of local enterprises: A customer-perceived value perspective. Sci. Sci. Manag. ST 2025, 46, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S. Towards green loyalty: Driving from green perceived value, green satisfaction, and green trust. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 21, 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, D.F.; Liao, Y.T.; Wang, H.Z. The impact of the interaction between green advertising appeals and product typicality on consumer purchase intention: A dual-path mechanism rooted in image congruity. Commer. Econ. Manag. 2025, 4, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Polonsky, M.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Kar, A. Green information quality and green brand evaluation: The moderating effects of eco-label credibility and consumer knowledge. Eur. J. Mark. 2021, 55, 2037–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Jhawar, A.; Shetty, K.; Varshney, S. Green ad stories’ characteristics and green brand trust: Examining the moderating role of consumer expertise through the elaboration likelihood model lens. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2025, 1–14, (Early Access). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Keh, H.T.; Wang, X. Powering Sustainable Consumption: The Roles of Green Consumption Values and Power Distance Belief. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 169, 499–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, T.; Seok, J.; Kim, Y. Unveiling ways to reach organic purchase: Green perceived value, perceived knowledge, attitude, subjective norm, and trust. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 67, 102988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chwialkowska, A.; Bhatti, W.A.; Bujac, A.; Abid, S. An interplay of the consumption values and green behavior in developed markets: A sustainable development viewpoint. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 3771–3785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Li, X. Addressing consumer skepticism: Effects of post-purchase green attribute disclosure on consumer attitude change. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, S.Y.; Sheng, G.H. The double-edged sword effect of product green attribute information on consumer decision-making: Formation mechanism and boundary mechanism. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2023, 31, 1611–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cam, L.N.T. A rising trend in eco-friendly products: A health-conscious approach to green buying. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 67 | 40.6.9 |

| Female | 98 | 59.4 | |

| Age (years) | ≤15 | 3 | 1.9 |

| 18–22 | 108 | 65.4 | |

| 12–25 | 44 | 26.7 | |

| ≥26 | 10 | 6 | |

| Education level | Junior college | 3 | 1.8 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 125 | 75.8 | |

| Master’s degree | 37 | 22.4 | |

| Income (CNY) | ≤1000 | 33 | 20.0 |

| 1001–2000 | 70 | 42.4 | |

| 2001–3000 | 44 | 26.1 | |

| ≥3000 | 18 | 10.9 | |

| Source | Type III Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corrected Model | 42.532 a | 3 | 14.177 | 32.985 | 0.000 |

| Intercept | 4179.422 | 1 | 4179.422 | 9723.978 | 0.000 |

| GAC | 10.695 | 1 | 10.695 | 24.884 | 0.000 |

| EC | 17.202 | 1 | 17.202 | 40.022 | 0.000 |

| GAC × EC | 15.302 | 1 | 15.302 | 35.601 | 0.000 |

| Error | 69.199 | 161 | 0.430 | ||

| Total | 4303.667 | 165 | |||

| Corrected Total | 111.731 | 164 |

| Variable | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 86 | 41.3 |

| Female | 111 | 58.7 | |

| Age (years) | ≤22 | 12 | 6.1 |

| 23–32 | 47 | 23.9 | |

| 33–42 | 26 | 13.2 | |

| 43–52 | 33 | 16.8 | |

| 53–62 | 53 | 26.9 | |

| ≥63 | 26 | 13.2 | |

| Education level | High school | 7 | 3.8 |

| Junior college | 62 | 31.5 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 107 | 54.3 | |

| Master’s degree | 8 | 91.8 | |

| Income (CNY) | ≤2000 | 54 | 27.4 |

| 2001–3000 | 65 | 33.0 | |

| 3001–5000 | 38 | 19.3 | |

| 5001–8000 | 28 | 14.2 | |

| ≥8001 | 12 | 6.1 | |

| Source | Type III Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corrected Model | 56.704 a | 3 | 18.901 | 37.547 | 0.000 |

| Intercept | 3632.513 | 1 | 3632.513 | 7215.822 | 0.000 |

| EC | 33.561 | 1 | 33.561 | 66.668 | 0.000 |

| GAC | 4.019 | 1 | 4.019 | 7.984 | 0.005 |

| EC × GAC | 9.686 | 1 | 9.686 | 19.242 | 0.000 |

| Error | 90.614 | 180 | 0.503 | ||

| Total | 4377.563 | 184 | |||

| Corrected Total | 147.318 | 183 |

| Variable | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 142 | 47.5 |

| Female | 157 | 52.5 | |

| Age (years) | ≤18 | 17 | 5.7 |

| 18–25 | 92 | 30.8 | |

| 26–35 | 94 | 31.4 | |

| 36–45 | 67 | 22.4 | |

| ≥55 | 29 | 9.7 | |

| Education level | High school | 14 | 4.7 |

| Junior college | 64 | 21.4 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 181 | 60.5 | |

| Master’s degree | 38 | 12.7 | |

| Doctor’s degree | 2 | 0.6 | |

| Income (CNY) | ≤2000 | 72 | 24.1 |

| 2001–3000 | 71 | 23.7 | |

| 3001–5000 | 57 | 19.1 | |

| 5001–8000 | 68 | 22.7 | |

| ≥8000 | 31 | 10.4 | |

| Source | Type III Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corrected Model | 113.905 a | 7 | 16.272 | 18.104 | 0.000 |

| Intercept | 5386.103 | 1 | 5386.103 | 5992.604 | 0.000 |

| GAC | 42.153 | 1 | 42.153 | 46.899 | 0.000 |

| EC | 15.122 | 1 | 15.122 | 16.825 | 0.000 |

| GT | 15.619 | 1 | 15.619 | 17.378 | 0.000 |

| GAC × EC | 21.064 | 1 | 21.064 | 23.436 | 0.000 |

| GAC × GT | 8.965 | 1 | 8.965 | 9.975 | 0.002 |

| EC × GT | 3.304 | 1 | 3.304 | 3.676 | 0.056 |

| GAC × EC × GT | 5.401 | 1 | 5.401 | 6.009 | 0.015 |

| Error | 261.548 | 291 | 0.899 | ||

| Total | 5792.444 | 299 | |||

| Corrected Total | 375.453 | 298 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, K.; Sun, X.; Yuan, B.; Tan, Y.; Yang, C. Easy to Know, Hard to Act: How Do Green Attribute Centrality, Environmental Concern, and Trust Exert a Chain Effect on Purchase Decisions? Sustainability 2025, 17, 10540. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310540

Zhang K, Sun X, Yuan B, Tan Y, Yang C. Easy to Know, Hard to Act: How Do Green Attribute Centrality, Environmental Concern, and Trust Exert a Chain Effect on Purchase Decisions? Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10540. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310540

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Kun, Xiaoling Sun, Baolong Yuan, Yuxuan Tan, and Caiyan Yang. 2025. "Easy to Know, Hard to Act: How Do Green Attribute Centrality, Environmental Concern, and Trust Exert a Chain Effect on Purchase Decisions?" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10540. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310540

APA StyleZhang, K., Sun, X., Yuan, B., Tan, Y., & Yang, C. (2025). Easy to Know, Hard to Act: How Do Green Attribute Centrality, Environmental Concern, and Trust Exert a Chain Effect on Purchase Decisions? Sustainability, 17(23), 10540. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310540