Abstract

Despite much interest in the flow experienced by English as a Foreign Language (EFL) teachers, there is less research on flow re-engagement and pre-service teachers at the crucial phase of career development. This study aims to examine flow dynamics among pre-service and in-service EFL teachers in China during teaching. Six Chinese EFL teachers (three pre-service and three in-service) engaged in two rounds of interviews over the course of one year, which were analyzed using a thematic narrative approach. The findings indicate that immediate feedback, clear goals, and a challenge-skill balance were key antecedents of flow. In-service teachers highlighted principal’s teaching-focused philosophy, technology support, teaching experience and curiosity. All participants reported a sense of control, deep absorption, and time distortion. Two experienced teachers further claimed a loss of self-consciousness. The flow of participants was impeded by student-related factors, strong self-consciousness, and technological breakdowns. In-service teachers noted more complicated causes. To re-enter a state of flow, pre-service teachers favored avoidance strategies, whereas in-service teachers employed more flexible approaches. Flow enhanced instructors’ teaching confidence, shifted pre-service teachers’ career motivation and fostered in-service educators’ professional well-being, post-class reflection, and self-improvement. Administrators and teacher educators should provide a teaching-oriented working environment for in-service teachers and offer flow-focused training to pre-service teachers, thus promoting their flow experiences and fostering sustainable professional development.

1. Introduction

Language teaching is regarded as a highly emotional profession due to the continuous emotional experiences and regulation that teachers undergo during teaching [1]. Previous studies have devoted much attention to teachers’ negative emotions, such as anxiety [2] and burnout [3]. In the Chinese EFL context, teachers are facing heavy workloads and a new round of curricular reform, which may further increase the risk of burnout. From the standpoint of sustainability, these ongoing emotional demands require the cultivation of teachers’ sustainable motivation and mitigation of burnout over the long term. Recent studies have suggested that teachers’ positive psychology is crucial for promoting teachers’ professional development as well as enhancing students’ performance and emotions [4]. According to the Broaden and Build Theory of Positive Emotions [5], educators’ positive emotions can promote mental resilience, hence increasing openness and acceptance of stress. Flow, as a basic concept of positive psychology, has been observed when teachers guide students to engage in the educational process [6]. When teachers experience flow, their high level of engagement and pleasant emotions during teaching serve as psychological resources that support sustainable motivation and reduce the risk of burnout, thereby facilitating their sustainable professional development [7].

Prior studies identified the conditions and affective states associated with the flow experienced by in-service EFL teachers [8,9]. Additionally, certain research suggested that flow can positively impact teachers’ professional development [10]. Recently, Barthelmäs and Keller [11] proposed the three-dimensional flow theory, involving the antecedents, experiential features, and consequences of flow. Some scholars highlighted the fragility of flow among in-service EFL teachers [12,13,14]. Nonetheless, there has been no investigation of the re-engagement of EFL teachers’ flow after disruptions, which is a key aspect of flow dynamics [12]. Furthermore, current research has primarily focused on in-service EFL teachers, neglecting pre-service teachers who are at the pivotal stage of their professional careers [15].

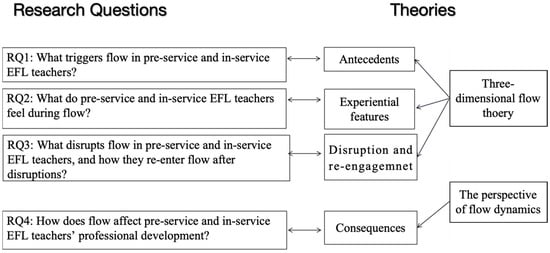

To fill these gaps, this research adopts a thematic narrative approach to investigate flow dynamics among Chinese pre-service and in-service EFL teachers during teaching. The research questions are: (1) What triggers flow in pre-service and in-service EFL teachers? (2) What do pre-service and in-service EFL teachers feel during flow? (3) What disrupts flow in pre-service and in-service EFL teachers, and how they re-enter flow after disruptions? (4) How does flow affect pre-service and in-service EFL teachers’ professional development? The mapping between theories and research questions is presented in Figure 1. This research indicates that school administrators should create a teaching-focused environment and make teaching technologies more reliable to promote teachers’ flow. In this way, they can foster teachers’ sustainable motivation and reduce the risk of burnout. Furthermore, teacher education programs should raise pre-service teachers’ awareness of flow and provide guidance on how to experience and re-engage flow during teaching, so that they can develop sustainable motivation and adapt to their future teaching in the workplace. Furthermore, this study is significant for the general public, as teachers’ flow can enhance students’ performance and positive feelings, which contribute to a more educated citizenry in the long run.

Figure 1.

Mapping the Theories to Research Questions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Language Teachers’ Emotions: From Negative to Positive

Language teaching is a highly emotional occupation as teachers constantly experience and manage a range of emotions within the classroom environment [1]. Previous studies have mainly concentrated on teachers’ negative emotions, such as anxiety [2] and burnout [3]. Some scholars have discovered that teachers’ positive psychology positively influences educators’ professional well-being, as well as students’ performance [4]. The Broaden-and-Build Theory of Positive Emotions [5] posits that teachers’ positive emotions can broaden their mental resources and foster greater openness and tolerance toward stress and pressure. Flow, as a fundamental idea of positive psychology, plays an important role in helping teachers navigate instructional challenges [6,7]. Consequently, analyzing the flow experiences of EFL teachers is essential for comprehending sustainable education.

2.2. Flow Theories: Three-Dimensional Framework and Dynamics

Flow, originally defined by Csikszentmihalyi [8], denotes a pleasurable state of effortless involvement in an activity. Its core experiential characteristics include a sense of control, time distortion, deep absorption, and loss of self-consciousness [11]. Time distortion refers to the perception that time passes faster than usual. Deep absorption describes a state of complete immersion in the activity. A sense of control means that individuals have no worries about the ongoing task. Loss of self-consciousness occurs when individuals stop focusing on themselves. Moreover, flow often emerges when key conditions are met, such as clear goals, immediate feedback and a challenge-skill balance [11]. This indicates that flow often arises when individuals are familiar with the tasks, receive feedback on their performance, and perceive a balance between task challenges and their skills. Some experts have proposed that flow occurs when individuals perceive the challenge slightly exceeds their skills [16]. However, Nakamura, Tse and Shankland [12] emphasized that the relationship between a challenge-skill balance and flow is influenced by individual traits. Thus, it is necessary to consider individual characteristics when exploring the flow experiences. Barthelmäs and Keller [11] conceptualized flow within a three-dimensional framework, which consists of the antecedents, experiential feelings, and consequences of flow. Specifically, flow antecedents refer to the conditions that facilitate the occurrence of flow; experiential feelings describe the characteristics of the flow experience itself; consequences are related to the outcomes that flow generates, including cognitive, emotional and behavioral aspects.

Moreover, flow experiences are susceptible to various factors. Some scholars pointed out that exploring how individuals re-engage their flow after disruptions is essential for understanding flow dynamics [12]. From the perspective of Broaden-and-Build Theory of Positive Emotions [5], flow re-engagement reflects individuals’ capacity for emotional resilience, enabling them to sustain their attention and motivation in tasks when unexpected interruptions occur. Accordingly, it is essential to understand EFL teachers’ flow dynamics in real teaching contexts to consider their re-engagement after disruptions as a crucial component of flow experience.

2.3. Empirical Studies on EFL Teachers’ Flow

Recent years have seen an increase in empirical studies examining the flow experienced by in-service EFL teachers, concentrating on the conditions, disruptions, and outcomes. Concerning the antecedents of flow, Tardy and Snyder [10] conducted semi-structured interviews with ten in-service EFL teachers in Turkey. They found that teachers experienced flow during moments of high interest, and when unexpected situations happened during teaching. Cohen and Bodner [17], using a mixed method, revealed that teachers with different levels of teaching experience differed in their flow experiences, with experienced teachers entering flow more easily. Chen et al. [18] concentrated on Chinese university teachers’ optimal experiences through a longitudinal survey method. Their research found that teachers’ flow experience changed as their teaching experience accumulated. Sobhanmanesh [9] conducted a quantitative study on Irian EFL teachers. The research found that teachers’ flow is associated with their personal curiosity, which can enable teachers to tolerate greater challenges during teaching. Moreover, some scholars emphasized that contextual factors in the workplace facilitate teachers’ flow. Basom and Frase [19] pointed out that American EFL teachers consider the principal’s visits as a sign of care for their teaching, which can motivate professional recognition and involvement, thereby supporting their flow. Additionally, students’ responses [10] and peer interaction [13] were also found to facilitate in-service teachers’ flow. However, previous research on antecedents of flow simply focused on in-service teachers, ignoring pre-service teachers who are in the crucial stage of professional development.

Regarding flow disruptions, performance anxiety was found to cause disruptions in flow [20]. Similarly, Dewaele and MacIntyre [14], using qualitative interviews, showed that language anxiety and threats to one’s sense of self and identity can interrupt language teachers’ flow. Furthermore, Khajavi and Abdolrezapour [13] examined Iran EFL teachers’ flow through a mixed method. Their study found that students’ behaviors and thought patterns, and technical obstacles could impede EFL teachers’ flow. However, despite much research on flow disruptions, little attention has been paid to how EFL teachers re-engage their flow during teaching.

As for the consequences of flow, several studies indicated that EFL teachers’ flow experiences played a crucial role in their motivation, professional growth, and well-being. Landhäußer and Keller [21] asserted that the enjoyment during flow motivated teachers to improve their professional skills, thereby enhancing professional well-being and meaning in life. They also suggested that flow can force teachers to engage in self-exploration and search for ways to improve themselves. Dai and Wang [7] focused on in-service EFL teachers through a quantitative method. They identified that flow can stimulate teachers’ work engagement, and change teachers’ career motivation. Tardy and Snyder [10] found that EFL teachers’ flow shapes teaching practices. Landhäußer and Keller [21] summarized three aspects of positive impact of flow, including cognition, emotions and behaviors. However, prior studies on the consequences of flow also targeted only in-service teachers, overlooking pre-service teachers.

2.4. Research Gap and Rationale

Although prior studies laid a strong theoretical foundation for current research, there are still several gaps that require attention. First, while some scholars have noted interruptions of flow, little attention has been paid to how EFL teachers re-engage in flow during teaching after disruptions. This is a key aspect for understanding the dynamic nature of flow. Second, existing studies have focused on in-service teachers, neglecting pre-service teachers who are in the crucial stage of professional development [15]. Furthermore, Chinese EFL teachers are experiencing substantial workloads and a new phase of curricular reform, which may exacerbate the risk of teachers’ professional burnout.

This research seeks to advance prior studies by addressing the empirical gaps and considering the contextual problems specific to Chinese EFL teachers. Drawing on the three-dimensional flow framework and a dynamic perspective on flow, this study adopts a thematic narrative approach to examine Chinese pre-service and in-service EFL teachers’ flow experiences, including the antecedents, feelings, disruptions and coping strategies, and consequences of teachers’ flow.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

This research utilized a thematic narrative method to analyze interview data, enabling researchers to discern common patterns across narratives while preserving the integrity of individual stories [22]. In line with this approach, this study intends to identify the recurring patterns in participants’ flow experiences while capturing individual diversity through illustrative narratives. The analysis was guided by the three-dimensional flow theory [11], involving antecedents, experiential features, and consequences. Moreover, the perspective of flow dynamics proposed by Nakamura, Tse and Shankland [12] was incorporated to emphasize the flow disruptions and re-engagement.

3.2. Research Setting

Pre-service teachers participated in an English teaching program affiliated with the Department of Foreign Language of a Normal University in Henan Province, China. This program functioned as a practicum platform for English education majors within a school environment, rather than a conventional educational institution. It was founded in December 2023 to enhance English education majors’ teaching experience. Approximately twenty children engaged in the lessons, all of whom were English beginners aged six to nine. A lesson occurred weekly, with each session lasting for sixty minutes. The instructional materials were sourced from People’s Education Press (PEP) Grade 3 English textbook (2012), as formal English classes officially commenced in Grade 3 [23].

Furthermore, three in-service teachers worked in public elementary schools in China. Each of their classes consisted of almost forty students. Both Deli and Ella taught at the same school in Zhengzhou, the capital city of Henan province. However, Francia was employed in a remote town in Shaanxi Province. These regional differences resulted in two main distinctions. The initial aspect was instructional resources: Deli and Ella’s classrooms were well-equipped with advanced teaching facilities, which enabled teachers to integrate various technologies during teaching. Conversely, Francia mainly relied on technologies to present PPT slides. A further distinction pertained to students’ exposure to English. Deli and Ella’s students were exposed to English earlier than Francia’s students, who learned English in formal classes. Moreover, Deli and Francia taught Grade 3 English lessons with the 2024 edition of the PEP textbook, whereas Ella taught Grade 6 English classes with the 2012 edition of PEP English textbook. According to the Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China [24], a new round of English textbook reform was applied to Grade 3 English textbooks but was not extended to Grade 6.

3.3. Participants

Purposeful sampling was utilized to explore the flow experiences of EFL teachers, as this method allows researchers to collect the data that are relevant to the research purpose [25]. Six EFL teachers participated in the research. In accordance with the saturation criteria [26], thematic saturation was achieved by the sixth interview, at which point no new themes emerged.

Three pre-service teachers, Anna, Beth and Cathy, majored in English education and were engaging in a university-based teaching program. Before enrolling in the program, they had completed core courses in English teaching methodologies and lesson design. After entering this program, they served as teaching assistants, aiding teachers with instruction and observing class delivery. Three weeks later, they started preparing for their first classes. All three pre-service teachers reported anxiety before and during teaching. Anna described herself as a creative teacher. Beth characterized herself as sensitive and prone to self-doubt. Cathy appeared to be open-minded.

Among the three in-service teachers, Ella and Francia had five years of teaching experience, while Deli had two years. The urban teachers (Deli and Ella) taught in well-resourced schools, so multiple technological tools were used in their classes to create an engaging classroom atmosphere. In contrast, Francia taught in a resource-limited rural school, where she mainly relied on PPT slides or simply on textbooks during instruction. A notable aspect of Francia’s teaching profile was her dual-language teacher identity. Owing to a teacher shortage in her school, she was assigned to teach both English and Chinese. This phenomenon, in which young teachers were asked to teach subjects outside their major, is common in remote rural schools in China [27]. Here is a summary of all participants’ background information (see as Table 1)

Table 1.

Demographic Information of Participants.

3.4. Data Collection

Data collection for this research lasted for one year, from September 2024 to August 2025. Before the formal collection, the researcher contacted each participant separately to introduce the research topic and secure their informed consent. Semi-structured interviews were conducted online twice with each participant due to geographical constraints. Each interview endured for nearly 90 min. The initial interview aimed to investigate the participants’ flow experiences. Participants were asked the following prepared questions: (1) Did you experience flow during teaching? (2) Could you describe how you were feeling during flow? (3) Could you describe what contributed to the occurrence of your flow? (4) Could you describe what disrupted your flow and how you coped with the situations? (5) How did you perceive the significance of flow for your professional growth? To aid recalling of specific events, the researcher played participants’ teaching videos during interviews. During the second interview, the researcher posed the questions to each participant (see Appendix A) that had not been included in the first interview but were mentioned by other participants. For instance, “Did you feel that the new textbook was so challenging that it triggered disruptions in your flow?” This interview facilitated a deeper insight into EFL teachers’ flow, revealing both shared patterns and distinctions. Additionally, participants’ instructional materials and videos were also gathered to provide a clearer insight into their classes and the smooth and disruptive moments during teaching.

3.5. Data Analysis

Prior to the formal analysis, the researcher familiarized herself with the data by reviewing interview transcripts. A hybrid deductive and inductive coding approach was employed during the coding process. Initially, four theoretical dimensions constituted the analytical framework, including (1) Antecedents of flow, (2) Feelings during flow, (3) Flow disruptions and coping strategies, and (4) Consequences of flow. For example, when participants expressed, “I felt that time went faster than usual,” this was recognized as the time distortion pattern corresponding to the theme feelings during flow. Nevertheless, certain elements of the data were not fully captured by the framework, including particular dimensions of flow antecedents, interruptions and coping strategies, and outcomes. To resolve this, data-driven inductive coding was performed to identify common patterns that emerged from participants’ quotes. For instance, when participants articulated, “students’ indifference embarrassed me,” “students’ cries made me nervous,” and “students’ distorted values annoyed me,” these statements were all grouped into the student-related factor pattern, linked to the theme of flow disruptions.

Narrative analysis was employed to elucidate the three teachers’ flow experiences, taking into account the dynamics and situational characteristics of flow [12]. Three teachers’ optimal experiences were selected as representative cases due to Beth’s flow disruptions caused by strong self-consciousness, Ella’s curiosity for teaching as an antecedent of flow, and Francia’s flow interruptions due to her identity as a non-English major English teacher and school limitations. The comprehensive narratives of three representative cases promoted a deeper understanding of the dynamics of EFL teachers’ flow.

3.6. Ethical Considerations and Trustworthiness

This research adhered to the ethical principles of respect for individuals, concern for welfare, and justice [28]. Before data collection, the researcher obtained permission from the program organizer at the university’s English department. Informed consent was gained from six participants, who were then informed about the research purpose, procedures, and their rights. Moreover, pseudonyms were applied to protect their privacy. Furthermore, the researcher conveyed gratitude for participants’ cooperation by offering small gifts or a nominal financial compensation.

Member checking, peer debriefing and data triangulation were employed to ensure the credibility and trustworthiness of the research. First, the preliminary results were provided to participants for confirmation and feedback. Second, an additional qualitative researcher (the first author’s supervisor) evaluated the coding framework and thematic interpretations. All issues were addressed until consensus was achieved, ultimately enhancing the credibility of the data analysis. Third, data triangulation was accomplished using interview transcripts as main data, supplemented by instructors’ teaching videos and materials. Interviews were used to examine teachers’ subjective accounts of flow. Prior to interviews, the researchers analyzed the participants’ teaching materials to understand their instructional themes and objectives. Furthermore, their teaching videos were watched to pinpoint salient episodes (e.g., technological breakdowns, pauses). The episodes were subsequently shown to interviewees to aid them in recalling specific feelings, thoughts and emotions, allowing researchers to compare participants’ self-reported explanation with their actual behaviors. For instance, Beth stated she avoided eye contact with students when encountering flow disruption. This was observed in her teaching video, as she shifted her gaze from students toward the PPT slides during a moment of uncertainty. This study achieved cross-validation across multiple data sources by merging participants’ subjective narratives with contextual information from instructional materials and videos, thereby increasing the credibility and reliability of the findings.

3.7. Researcher’s Role

The researcher possessed a master’s degree in English education from the same university as the three pre-service teachers. This common background provided contextual familiarity about their academic training but did not create a hierarchical connection, as the researcher had already graduated before the participants enrolled in the teaching program. Additionally, the researcher had part-time English teaching experience, which enhanced her empathy towards participants. To minimize researcher influence, interviews emphasized open-ended prompts and limited researcher intervention, followed by probing questions aimed at addressing contradictions and alternative interpretations.

4. Findings

This section presents a cross-case study of the flow experiences of six participants, comprising three pre-service and three in-service EFL teachers. Their flow experiences are illustrated through four themes. Under them, “x/y” was adopted to represent the number of participants that referenced the patterns in their interviews (e.g., 5/6 indicates 5 out of 6 mentioned it). Then, three representative cases are shown. Detailed thematic matrixes with illustrative quotes are provided in Appendix B (Table A1, Table A2, Table A3 and Table A4).

4.1. Antecedents of Flow

All EFL educators (6/6) indicated that students’ immediate feedback, clear teaching goals, and a challenge-skill balance facilitated their optimal experience. Students’ positive responses increased teachers’ perception of control, thereby facilitating entry into a state of flow. According to Anna, “They all raised hands, which gave me a sense of control (A_1_2024/9/21).” Clear teaching goals facilitated their immersion in flow. Deli stated, “Clear teaching goals made me feel at ease during teaching (D_1_2025/6/7).” This indicates that explicit teaching objectives directed their teaching and helped them relax, thus facilitating their flow. Furthermore, English-major teachers (5/6) reported that tasks that slightly exceeded their skills yet remained manageable were conducive to flow. Beth stated, “The challenging but manageable tasks made me attentive (B_1_2024/10/19).” This suggests that challenging but manageable tasks sustained teachers’ attention, facilitating their optimal experience. Conversely, the non-English-major teacher (1/6) said she entered flow when teaching content was easy for her. Francia reported, “Easiness of teaching content built up my confidence (F_1_2025/6/14).” These findings show that teachers with different backgrounds perceived a challenge-skill balance differently.

Additionally, all in-service teachers (3/6) emphasized the significance of teaching experience, technology support, principal’s teaching-focused philosophy and the curiosity about teaching. Ella explained, “Familiarity with students’ individual differences and teaching process allowed me to be calm and flexible in class (E_1_2025/7/12).” The teachers’ experience facilitated greater adaptability in instruction. Moreover, urban in-service teachers (2/6) spoke of technology support. Deli stated, “FlexClip 3D animation feature kept everyone immersed (D_1_2025/6/7).” Technologies not only assisted teachers in cultivating an engaging atmosphere but also augmented their immersion during teaching, hence facilitating their flow. Furthermore, principal’s pedagogical philosophy was also underscored. Ella mentioned, “Principal’s focus on teaching informs me that I’m doing something meaningful, so I was more focused on teaching (E_1_2025/7/12).” This indicates that principal’s teaching-focused philosophy improved teachers’ professional recognition and maintained their concentration on instruction. Eventually, one in-service instructor (1/6) expressed her curiosity for teaching. According to Ella, “I saw teaching as experiments where I kept thinking and adjusting, which drives me to explore more during teaching (E_1_2025/7/12).” This reflects that teachers’ teaching curiosity sustained attention, promoting her entry into flow states. A summary matrix of antecedents of flow is presented in Table A1.

4.2. Feelings During Flow

The analysis revealed that all EFL teachers (6/6) perceived time as passing more rapidly than usual during flow experiences. Anna remarked, “When I saw the watch, I realized that 20 min passed (A_1_2024/9/21).” Moreover, all participants (6/6) reported experiencing a sense of control and deep absorption during flow. Candy mentioned, “I felt that the class was under my control (C_1_2024/10/26).” In addition, Deli claimed, “I was fully absorbed during teaching (D_1_2025/6/7).” Notably, two in-service teachers (2/6) with five-year teaching experience reported a loss of self-consciousness during flow, which wasn’t observed among the pre-service teachers and one in-service teacher with two-year teaching experience. As Ella explained, “With five-year experience, I have become accustomed to the teaching process so I can devote myself to it (E_1_2025/7/12).” This indicates that the teacher with five years of experience was better accustomed to her working environment better, which helped immerse herself completely into teaching completely and lose her self-consciousness during flow. A summary matrix of participants’ feelings during flow is provided in Table A2.

4.3. Flow Disruptions and Coping Strategies

These results revealed that EFL teachers’ flow was impeded by multiple factors. Initially, all teachers (6/6) claimed that their flow was disrupted by student-related factors, like students’ indifference, talking back to teachers, inappropriate actions, distorted values, disagreement with teachers, and cries. Anna declared, “Students’ indifference embarrassed me (A_1_2025/6/7).” Students’ indifference distracted her attention and diminished her sense of control, hence obstructing her flow. Second, 6/6 teachers stated that their flow was stopped by technological breakdowns. Ella expressed, “The breakdown of technological equipment raised my concern about whether I can complete the class (E_1_2025/7/12).” This shows that technology failures heightened teachers’ apprehensions over class completion and interrupted their optimal experience. Third, 4/6 teachers pronounced strong self-consciousness as a disturbance to flow. Two teachers (2/6) conveyed concerns about possible evaluations from others concerning their teaching. Anna noted, “My imagination of student parents’ evaluation distracted my attention (A_1_2024/9/21).” Another two teachers (2/6) spoke of their internal conflict during teaching. Beth admitted, “My internal conflict about praising student led me to feel ashamed (B_1_2024/10/19).” The finding indicates that teachers’ self-consciousness disrupted their attention during instruction, thus impeding their flow.

Notably, all in-service instructors (3/6) asserted that their flow was additionally affected by institutional and situational factors. First, three in-service educators (3/6) referenced non-instructional duties. Deli complained, “Non-instructional duties made me tired and distracted my attention in class (D_2_2025/8/24).” This suggests that teachers’ physical and mental conditions deteriorated due to an excess of non-instructional responsibilities, consequently interrupting their flow. Second, two out of six in-service teachers identified the challenging new textbook as demanding. Francia claimed, “The increased difficulty of new textbook induced my teaching anxiety (F_2_2025/8/19).” This illustrates that the increased challenges of the new textbook induced anxiety while teaching, thus interrupting their optimal experience. Finally, two in-service educators (2/6) emphasized the principal’s sporadic visits. Ella complained, “Principal’s sporadic visits distracted my attention (E_2_2025/8/23).” This suggests that principal’s visits distracted teachers’ attention during instruction, thereby interrupting their flow.

In addition, the analysis shows that participants employed various strategies to manage flow disturbances. First, all EFL teachers (6/6) indicated an emphasis on problem-solving. According to Ella, “Devoting myself to solving the technological problem calmed me down and reduced panic (E_2_2025/8/23).” It assisted them in alleviating distressing feelings (e.g., panic, nervousness, etc.), thereby facilitating them to return to a state of flow. Second, pre-service teachers (3/6) preferred avoidance strategies to mitigate their unpleasant emotions, hence helping them re-enter a state of flow. Beth said, “I avoided eye contact with students, which helped me alleviate my internal conflict (B_1_2024/10/19).” Moreover, two pre-service teachers (2/6) chose to disregard students’ misbehaviors due to their inability to find effective interventions. Candy stated, “Ignoring their misbehaviors can reduce my nervousness (C_1_2024/10/26).”

Nonetheless, in-service EFL teachers exhibited a propensity for using more flexible ways to mitigate flow disturbances. Three out of six in-service teachers acknowledged a long-term teaching belief. Deli remarked, “Knowing about poorly learned content could be reviewed and practiced in later classes alleviated my worries (D_1_2025/6/7).” This shows that teachers’ concerns were alleviated upon realizing that review and practice might be conducted to reinforce students’ learning. Additionally, two in-service teachers (2/6) mentioned a reduction in teaching goals. As Francia stated, “Focusing on main teaching content reduced my stress and sense of guilt (F_2_2025/8/19).” This indicates that lowering goals mitigated the challenge-skill disparity, allowing teachers to re-enter a state of flow. An overview matrix of teachers’ flow disruption factors and coping strategies is included in Table A3.

4.4. Consequences of Flow

Initially, all teachers (6/6) asserted that students’ positive responses during flow enhanced their teaching confidence. As Beth noted, “Smooth process increased my confidence by reducing my anxiety during teaching (B_1_2024/10/19).” This shows that teachers’ nervousness during instruction was alleviated and confidence could be bolstered by the perception of teaching success in a state of flow. Second, five out of six EFL educators claimed that their capacity for adaptive decision-making was improved. According to Anna, “Immersion state was conducive to my creative ideas during teaching (A_2_2024/11/11).” This indicates that teachers exhibited increased adaptability when they experienced immersion in teaching during flow. Third, four out of six teachers stated their intrinsic motivation for professional development was strengthened by the sense of meaning in life during flow. Francia claimed, “The sense of meaning in life enhanced my intrinsic drive for my professional growth (F_2_2025/8/19).” Fourth, four teachers (4/6) said that enjoyable experiences motivated them to reflect on their teaching, enabling them to frequently attain a state of flow. As Ella mentioned, “Enjoyable experience motivated me to summarize what made the lessons successful (E_2_2025/8/23).” Fifth, all in-service teachers (3/6) expressed that their professional well-being improved due to students’ active engagement during flow. Deli stated, “Active atmosphere reinforced my belief that being a teacher is fulfilling profession (D_2_2025/8/24).” Finally, two pre-service teachers (2/6) said that the pleasure derived from flow transitioned their career motivation from external recognition to internal satisfaction. Candy declared, “The enjoyment in flow shifted my career motivation from external recognition to internal satisfaction (C_2_2024/11/11). A summarized matrix of flow consequences is shown in Table A4.

4.5. Three Representable Cases’ Flow Experiences

4.5.1. Beth’s Flow Experience

Beth described her optimal experiences while teaching, despite initially feeling rather nervous at the start of the lesson. Prior to the instruction, she thoroughly prepared, which made her familiar with the teaching content and process. Moreover, Beth added that students’ positive responses in class enhanced her teaching confidence, facilitating her entry into a state of flow. Beth remembered experiencing a sense of control, deep immersion, and time flying faster than normal during flow state. However, Beth didn’t experience a loss of self-consciousness for not being adapted for teaching. Furthermore, Beth encountered flow disruptions due to her strong self-consciousness. As she stated, “When I praised students with thumb-ups and exaggerated facial expressions, I felt unease (B_1_2024/10/19).” This was due to the fact that these acts or expressions do not constitute her communication in reality (e.g., thumb-up, ‘wow, you’re so great). Consequently, unfamiliar expressions provoked internal conflict, thereby hindering her flow. To cope, she attempted to evade eye contact with students in order to attain inner tranquility and re-engage in the teaching process. Beth concluded that the pleasure during flow informed her that future classes need not induce anxiety and inspired her to seek more effective teaching resources. Furthermore, she asserted that her career motivation shifted from external recognition to internal satisfaction during instruction.

4.5.2. Ella’s Flow Experience

Ella frequently utilized technologies to create an interactive environment during instruction. For instance, Ella converted students’ paintings into 3D animation using Flexclip, which enhanced students’ participation in class and sustained her focus on teaching, facilitating her optimal experience. Moreover, Ella asserted that she consistently dedicated herself to improving her teaching owing to her strong pedagogical curiosity. This continuous cognitive process enabled her to be fully engaged throughout teaching. As she stated, “I saw teaching as experiments where I kept thinking and adjusting, which drives me to explore more during teaching (E_1_2025/7/12).” Furthermore, Ella reported her principal’s pedagogical philosophy maintained her attention through enhancing her professional recognition. Ella declared, “Principal’s focus on teaching informs me that I’m doing something meaningful, so I was more focused on teaching (E_1_2025/7/12).”

In addition, Ella mentioned her experience of diminished self-consciousness during flow, alongside enjoyment, deep involvement, sense of control, and distortion of time track. Nevertheless, Ella’s flow was impeded when technologies went wrong or students misbehaved. To cope with the disruptions, Ella concentrated on technical breakdowns, lowered teaching objectives, or embracing a long-term teaching belief to facilitate seamless instruction and regain optimal experience. Ultimately, Ella believed that the enjoyment experienced during flow improved her professional well-being and stimulated her post-class contemplation. In practice, Ella frequently tested techniques to reach a state of flow among different student groupings. For example, she saw her pupils in a low-level class show greater interest in content pertinent to their everyday lives. Subsequently, she collected some photos of students’ pets to capture their interest and involve them in class.

4.5.3. Francia’s Flow Experience

Francia, a non-English-major English instructor, noted that her deficiency in confidence influenced the precursors of her flow experience. In contrast to the other five English education major teachers, who were more attentive when tasks slightly exceeded skills, Francia expressed that simplicity of the teaching content provided her considerable relaxation during teaching, helping her enter into a state of flow. Francia articulated, “The simplicity of teaching content built up my confidence (F_1_2025/6/14).” Moreover, Francia mentioned the sense of loss of self-consciousness beyond typical feelings. Francia explained that she possessed much autonomy during teaching at school. If students positively responded to her, then she derived enjoyment from the teaching and occasionally lost track of the class bell. Furthermore, Francia’s dual-language identity resulted in inner conflict during a lesson on Christmas, as her admiration for Chinese culture clashed with the content about Western celebrations. Moreover, Francia claimed the increased difficulty of the new textbook exacerbated her teaching anxiety, stemming from her identification as a non-major English teacher, particularly when encountering unfamiliar words during instruction. In addition, students’ distorted values, exemplified by their laughing at the photos of kids with black skin annoyed her, which impeded her state of optimal experience. To return to the state, Francia endeavored to teach them correct values, facilitating her emotional regulation and reentry into her flow state. Eventually, Francia highlighted that immersion and pleasure during flow brought her a sense of meaning in life and strengthened her motivation to advance English teaching skills.

5. Discussion

These findings reveal three new insights into EFL teachers’ flow experiences. Initially, experienced EFL instructors reported a loss of self-consciousness during flow whereas less experienced counterparts did not. Second, in-service EFL teachers encountered more complex, institutional and contextual disturbance during flow. Ultimately, teachers utilized various strategies to regain their flow, depending on their individual characteristics and the nature of the disruption.

A key finding of this research is that only experienced teachers (with five years of teaching experience) experienced a loss of self-consciousness during flow. This is consistent with the core experiential features of flow proposed by Csikszentmihalyi [8]. Moreover, it also confirmed the conclusion of [17] that individuals’ accumulated experience could enhance their immersion in activities and facilitate their optimal experience. Nevertheless, the focus of pre-service and less experienced educators was likely to be diverted during teaching [8]. Therefore, they do not experience the loss of self-consciousness as they were unable to completely immerse themselves in classes. This result can be further interpreted using Fredrickson’s [5] Broaden-and-Build Theory of Positive Emotions. Individuals’ positive emotions associated with task execution can broaden attention and reduce self-focused worries, thereby facilitating absorption in the task. Conversely, evaluative concerns and self-doubt can hamper their cognitive expansion for deep immersion.

This study confirms certain prior studies conducted in other countries (e.g., Turkey, Iran and the United States), including the impact of teaching experience, personality, and students’ immediate feedback on EFL teachers’ flow, while also revealing new patterns regarding flow disruptions. In contrast to previous results on disruptions to EFL teachers’ flow [10,13,14], the current study indicates that in-service teachers’ flow may be impeded by institutional and contextual factors. It was discovered that non-instructional tasks, and principal’s sporadic visits could interrupt in-service teachers’ flow during instruction. In particular, a recent phase of ongoing curriculum reform in China has shaped the distinctive institutional disruption of EFL teachers’ flow, compared with the findings from other nations. These findings correspond with the perspective of Strom and Viesca [29] on the high emotionality of language teachers. It is considered that language educators frequently encounter stress or distraction when confronted with situations beyond their control.

Another new discovery pertains to the coping strategies employed by participants to address flow interruptions, in response to the request of Nakamura, Tse and Shankland [12] for the re-engagement of flow. The analysis indicated that pre-service teachers tended to use avoidance strategies, such as avoiding eye contact with students and ignoring students’ disruptive behaviors, to manage their nervousness and embarrassment. This can be understood from the viewpoints that pre-service teachers lack teaching confidence and classroom management experience [30]. When faced with obstacles in teaching, they preferred to adopt avoidance methods to attain inner calm [31,32]. Conversely, in-service teachers preferred more flexible tactics, such as problem-solving, lowering teaching goals, and adopting a long-term teaching belief to mitigate stress and anxiety. The distinction underscores the vital role of classroom management abilities and accumulated teaching experience in shaping their coping strategies for flow disruptions [33].

This research has several limitations. Initially, this study investigated pre-service and in-service EFL teachers’ flow experiences in the specific context of teaching. However, individuals’ flow may differ in different situations [8]. Future research could extend these findings by examining the disparity in flow experiences between the two groups of EFL teachers’ flow in alternative contexts, like leisure activities. Secondly, this study explored participants’ flow experience throughout a particular phase of professional development. According to Chen et al. [18], teachers’ flow may change with an increase in their teaching experience. Consequently, future researchers may conduct longitudinal studies to investigate the trajectory of flow experiences among EFL teachers across different stages of career development. Moreover, the participants in this research were from a restricted area in China. Future research should be undertaken in a greater variety of countries and districts to yield a more thorough knowledge of EFL teachers’ flow experiences. However, it is important to acknowledge that the transferability of these findings might be limited due to Chinese special context, such as the current curriculum reform. In addition, this research also neglected participants’ English proficiency and gender, both of which have been shown to affect individuals’ flow experience [34]. Subsequent studies should take gender and English proficiency into account while investigating the dynamics of EFL teachers’ flow. Ultimately, the researcher’s experience of English teaching might influence data interpretation, despite efforts to minimize her personal bias.

6. Conclusions and Implication

This research aimed to examine the dynamics of flow experiences among pre-service and in-service EFL teachers, focusing on the antecedents, feelings, disruptions and coping strategies, and consequences of flow. First, all participants identified three prevalent antecedents of flow: clear teaching goals, students’ immediate feedback, and a challenge-skill balance. Moreover, distinctions were noted in the perception of a challenge-skill balance and flow dynamics across participants’ professional backgrounds. Second, this study also identified typical feelings during flow including deep absorption, a sense of control, and time distortion. Third, the results indicate that participants’ flow is impeded by student-related factors and their own strong self-consciousness. Ultimately, this research discovered that EFL teachers’ flow positively impacted their professional development. Their flow states aided in mitigating pedagogical anxiety, enhancing confidence and enabling pre-service teachers to transition from external recognition to internal pleasure. For in-service educators, flow facilitated their professional well-being, subsequent reflection and professional development.

Additionally, several new findings emerged in this research. First, the absence of self-consciousness was recognized as an uncommon feature during flow, frequently observed among experienced teachers. The teachers, unaccustomed to their roles, failed to attain a condition of less self-consciousness. Second, the disruptive factors affecting in-service teachers’ flow were complicated. They declared institutional factors (e.g., non-instructional duties, principal’s visits) interrupted their flow. In addition, the ongoing curriculum reform in China created a special situational factor that disrupted Chinese EFL teachers’ flow. Finally, this research showed how EFL teachers returned to their flow after disruptions, which had been largely ignored in previous studies. This research found that pre-service teachers preferred avoidance strategies due to low teaching confidence, whereas in-service teachers used flexible strategies (e.g., focusing on problem-solving, lowering teaching goals, and using long-term teaching belief) to alleviate mental stress and concerns.

These findings have some implications for school administrators and teacher educators. School administrators are encouraged to create a teaching-focused environment to promote in-service teachers’ flow, thereby fostering teachers’ sustainable motivation and reducing the risk of burnout. Moreover, it is recommended that teacher educators raise teacher candidates’ awareness of flow and equip them with techniques to attain and re-enter flow during teaching, thus facilitating their sustainable professional development and adaptability in future teaching environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L. and J.K.; methodology, J.L. and J.K.; investigation, J.L. and J.K.; data analysis, J.L. and J.K.; composing of draft, J.L. and J.K.; review and editing of the draft, J.L. and J.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study met the exemption criteria under Regulation 104-2 and was granted an exempt determination 5 September 2024 for research involving normal educational issues within an educational environment (Protocol CNU-EC-2024-EX-019) from JBNU.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Examples of Semi-Structure Interview Questions

Appendix A.1. First Interview

- Did you experience flow during teaching?

- Could you describe how you were feeling during flow?

- Could you describe what contributed to the occurrence of your flow?

- Could you describe what disrupted your flow and how you coped with the situations?

- How did you perceive the significance of flow for your professional growth?

Appendix A.2. Second Interview

- Did you feel that the task slightly higher than your skills helped to enter flow?

- Did you feel that the principal’s sporadic visits interrupted your flow? And why?

- Did you feel that the new textbook was so challenging difficult that triggered disruptions in your flow? And why?

- Did you re-turn your flow though lowering teaching goals? Could you give some specific examples?

- Did you re-turn your flow though ignore students’ behaviors? Could you give some specific examples?

- Did you feel that flow changed your career motivation from external recognition to internal pleasure? And why?

- Did you feel that flow experiences motivated you put more effort in professional growth? And why?

- Did you feel that flow experiences improved your professional well-being? And why?

- Did you feel that flow experiences supported your decision-making during teaching? Could you give some specific examples?

- Did you feel that flow experiences motivated you to reflect your post-lesson reflection? Could you give some specific examples?

Appendix B. Thematic Matrixes with Additional Illustrative Quotes

Table A1.

Thematic Analysis of Antecedents of Flow in Participants.

Table A1.

Thematic Analysis of Antecedents of Flow in Participants.

| Theme | Patterns | Frequency | Quotes | Research Question |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antecedents of Flow | Students’ immediate feedback | 6/6 | They all raised hands, which gave me a sense of control (A_1_2024/9/21). | What triggers flow in pre-service and in-service EFL teachers? |

| Clear goals | 6/6 | Clear teaching goals made me feel at ease during teaching (D_1_2025/6/7). | ||

| Challenge-skill balance | 6/6 | The challenging but manageable tasks made me attentive (B_1_2024/10/19). The simplicity of teaching content built up my confidence (F_1_2025/6/14). | ||

| Teaching experiences | 3/6 | Familiarity with students’ individual differences and teaching process allowed me to be calm and flexible in class (E_1_2025/7/12). | ||

| Technology support | 2/6 | FlexClip 3D animation feature kept everyone immersed (D_1_2025/6/7). | ||

| Principal’s teaching-focused philosophy | 2/6 | Principal’s focus on teaching informs me that I’m doing something meaningful, so I was more focused on the teaching (E_1_2025/7/12). | ||

| Teaching curiosity | 1/6 | I saw teaching as experiments where I kept thinking and adjusting, which drives me to explore more during teaching (E_1_2025/7/12). |

Table A2.

Thematic Analysis of Feelings during Flow in Participants.

Table A2.

Thematic Analysis of Feelings during Flow in Participants.

| Theme | Patterns | Frequency | Quotes | Research Question |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feelings during Flow | Time distortion | 6/6 | When I saw the watch, I realized that 20 min passed (A_1_2024/9/21). | What do pre-service and in-service EFL teachers feel during flow? |

| A sense of control for class | 6/6 | I felt that the class was under my control (C_1_2024/10/26). | ||

| Deep absorption | 6/6 | I was fully absorbed during teaching (D_1_2025/6/7). | ||

| Loss of self-consciousness | 2/6 | I didn’t notice the outside and hear the bell, and I lost self-awareness (F_1_2025/6/14). |

Table A3.

Thematic Analysis of Flow Disruptions and Coping Strategies in Participants.

Table A3.

Thematic Analysis of Flow Disruptions and Coping Strategies in Participants.

| Theme | Patterns | Frequency | Quotes | Research Question |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flow Disruptions | Student-related factors | 6/6 | Students’ indifference embarrassed me (A_1_2025/6/7). | What disrupts flow in pre-service and in-service EFL teachers, and how they re-enter flow after disruption? |

| Technological breakdowns | 5/6 | The breakdown of technological equipment raised my concern about whether I can complete the class (E_1_2025/7/12). | ||

| Strong self-consciousness (P125) | 4/6 | My imagination of student parents’ evaluation distracted my attention (A_1_2024/9/21). My internal conflict about praising student led me to feel ashamed (B_1_2024/10/19). | ||

| Non-instructional duties | 3/6 | Non-instructional duties made me tired and distracted in class (D_2_2025/8/24). | ||

| Curriculum reform | 2/6 | The increased difficulty of new textbook triggered my teaching anxiety (F_2_2025/8/19). | ||

| Principals’ visit | 2/6 | Principal’s sporadic visits distracted my attention (E_2_2025/8/23). | ||

| Coping Strategies | Focusing on problem-solving | 6/6 | Devoting myself to solving the technological problem calmed me down and reduced panic (E_2_2025/8/23). | |

| Ignoring students’ misbehaviors | 5/6 | Ignoring their misbehaviors can reduce my nervousness (C_1_2024/10/26). | ||

| Adopting a long-term teaching belief | 3/6 | Knowing about poorly learned content could be reviewed and practiced in later classes alleviated my worries (D_1_2025/6/7). | ||

| Lowering the teaching goals | 3/6 | Focusing on main teaching content reduced my stress and sense of guilt (F_2_2025/8/19). | ||

| Avoiding eye contact with students | 1/6 | I avoided eye contact with students, which helped me alleviate my internal conflict (B_1_2024/10/19). |

Table A4.

Thematic Analysis of Consequences of Flow in Participants.

Table A4.

Thematic Analysis of Consequences of Flow in Participants.

| Theme | Patterns | Frequency | Quotes | Research Question |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consequences of flow | Teaching confidence | 6/6 | Smooth process increased my confidence by reducing my anxiety during teaching (B_1_2024/10/19). | How does flow affect pre-service and in-service EFL teachers’ professional development? |

| Making adaptive decisions in class | 5/6 | Immersion state was conducive to my creative ideas during teaching (A_2_2024/11/11).” | ||

| Professional development drive | 4/6 | The sense of meaning in life enhanced my intrinsic drive for my professional growth (F_2_2025/8/19). | ||

| Post-lesson reflection | 4/6 | Enjoyable experience motivated me to summarize what made the lessons successful (E_2_2025/8/23). | ||

| Professional well-being | 3/6 | Active atmosphere reinforced my belief that being a teacher is a fulfilling profession (D_2_2025/8/24). | ||

| Career-motivation shift | 2 | The enjoyment in flow shifted my career motivation from external recognition to internal satisfaction (C_2_2024/11/11). |

References

- Ghanizadeh, A.; Royaei, N. Emotional facet of language teaching: Emotion regulation and emotional labor strategies as predictors of teacher burnout. Int. J. Pedagog. Learn. 2015, 10, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tüfekçi-Can, D. Foreign language teaching anxiety among pre-service teachers during teaching practicum. Int. Online J. Educ. Teach. 2018, 5, 579–595. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Liu, Z. Emotion regulation and well-being as factors contributing to lessening burnout among Chinese EFL teachers. Acta Psychol. 2024, 245, 104219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frenzel, A.C.; Daniels, L.; Burić, I. Teacher emotions in the classroom and their implications for students. Educ. Psychol. 2021, 56, 250–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. The flow experience and its significance for human psychology. In Optimal Experience: Psychological Studies of Flow in Consciousness; Csikszentmihalyi, M., Csikszentmihalyi, I.S., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1988; pp. 15–35. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, K.; Wang, Y.L. Investigating the interplay of Chinese EFL teachers’ proactive personality, flow, and work engagement. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2025, 46, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Beyond Boredom and Anxiety: Experiencing Flow in Work and Play; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sobhanmanesh, A. English as a foreign language teacher flow: How do personality and emotional intelligence factor in? Front. Psychol 2022, 13, 793955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardy, C.M.; Snyder, B. ‘That’s why I do it’: Flow and EFL teachers’ practices. ELT J. 2004, 58, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthelmäs, M.; Keller, J. Antecedents, boundary conditions and consequences of flow. In Advances in Flow Research; Peifer, C., Engeser, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 71–107. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, J.; Tse, D.C.K.; Shankland, S. Flow: The experience of intrinsic motivation. In The Oxford Handbook of Human Motivation; Ryan, R.M., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 439–454. [Google Scholar]

- Khajavi, Y.; Abdolrezapour, P. Exploring English as a Foreign Language (EFL) teachers’ experience of flow during online classes. Open Prax. 2022, 14, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewaele, J.M.; MacIntyre, P. “You can’t start a fire without a spark”. Enjoyment, anxiety, and the emergence of flow in foreign language classrooms. Appl. Linguist. Rev. 2024, 15, 403–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal-Gezegin, B.; Balikçi, G.; Gümüsok, F. Professional development of pre-service teachers in an English language teacher education program. Int. Online J. Educ. Teach. 2019, 6, 624–642. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, S.A.; Marsh, H.W. Development and validation of a scale to measure optimal experience: The Flow State Scale. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 1996, 18, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Bodner, E. The relationship between flow and music performance anxiety amongst professional classical orchestral musicians. Psychol. Music 2019, 47, 420–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wu, L.; Jia, L.; AlGerafi, M.A. Flow experience and innovative behavior of university teachers: Model development and empirical testing. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basom, M.R.; Frase, L. Creating optimal work environments: Exploring teacher flow experiences. Mentor. Tutoring: Partnersh. Learn. 2004, 12, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullagar, C.J.; Knight, P.A.; Sovern, H.S. Challenge/skill balance, flow, and performance anxiety. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 62, 236–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landhäußer, A.; Keller, J. Flow and its affective, cognitive, and performance-related consequences. In Advances in Flow Research; Engeser, S., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2012; pp. 65–85. [Google Scholar]

- Riessman, C.K. Narrative Methods for the Human Sciences; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. Compulsory Education Curriculum Plan and Standards (2022 Edition); Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2022.

- Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. Notice of the General Office of the Ministry of Education on Issuing the 2024 Catalogue of Nationally Approved Textbooks for Compulsory Education. Available online: http://hudong.moe.gov.cn (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Wang, Z. Assessing the development of primary English education based on CIPP model—A case study from primary schools in China. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1273860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Strom, K.J.; Viesca, K.M. Towards a complex framework of teacher learning-practice. In Non-Linear Perspectives on Teacher Development; Strom, K.J., Mills, T., Abrams, L., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill, S.; Stephenson, J. Does classroom management coursework influence pre-service teachers’ perceived preparedness or confidence? Teach. Teach. Educ. 2012, 28, 1131–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ay, T.S.; Gökdemir, A. Perception of peace among pre-service teachers. Int. J. Eval. Res. Educ. 2020, 9, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.Z.; Zhou, L.L. Self-care strategies for preservice teachers: A scoping review. Teach. Teach. 2025, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkut, P. Classroom Management in Pre-Service Teachers’ Teaching Practice Demo Lessons: A Comparison to Actual Lessons by In-Service English Teachers. J. Educ. Train. Stud. 2017, 5, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isham, A.; Jackson, T. Whose ‘flow’is it anyway? The demographic correlates of ‘flow proneness’. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2023, 209, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).