Empathy, Reconciliation, and Sustainability Action: An Evaluation of a Three-Year Community of Practice with Early Educators

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Project Context and Supporting Literature

Education and culture are both global public goods inscribed in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights… and essential cornerstones of sustainable development, making direct contributions and acting as enablers for achievement in other dimensions of sustainability, including environmental sustainability, employment, inclusion, and prosperity. They also mutually enable one another. Education is essential for the full enjoyment of cultural rights and for enabling modern, functioning cultural industries. Culture, in its widest definition, ultimately shapes education. It also enriches education and enables education systems to achieve better results that contribute to thriving and fulfilled societies.[9] (p. 8)

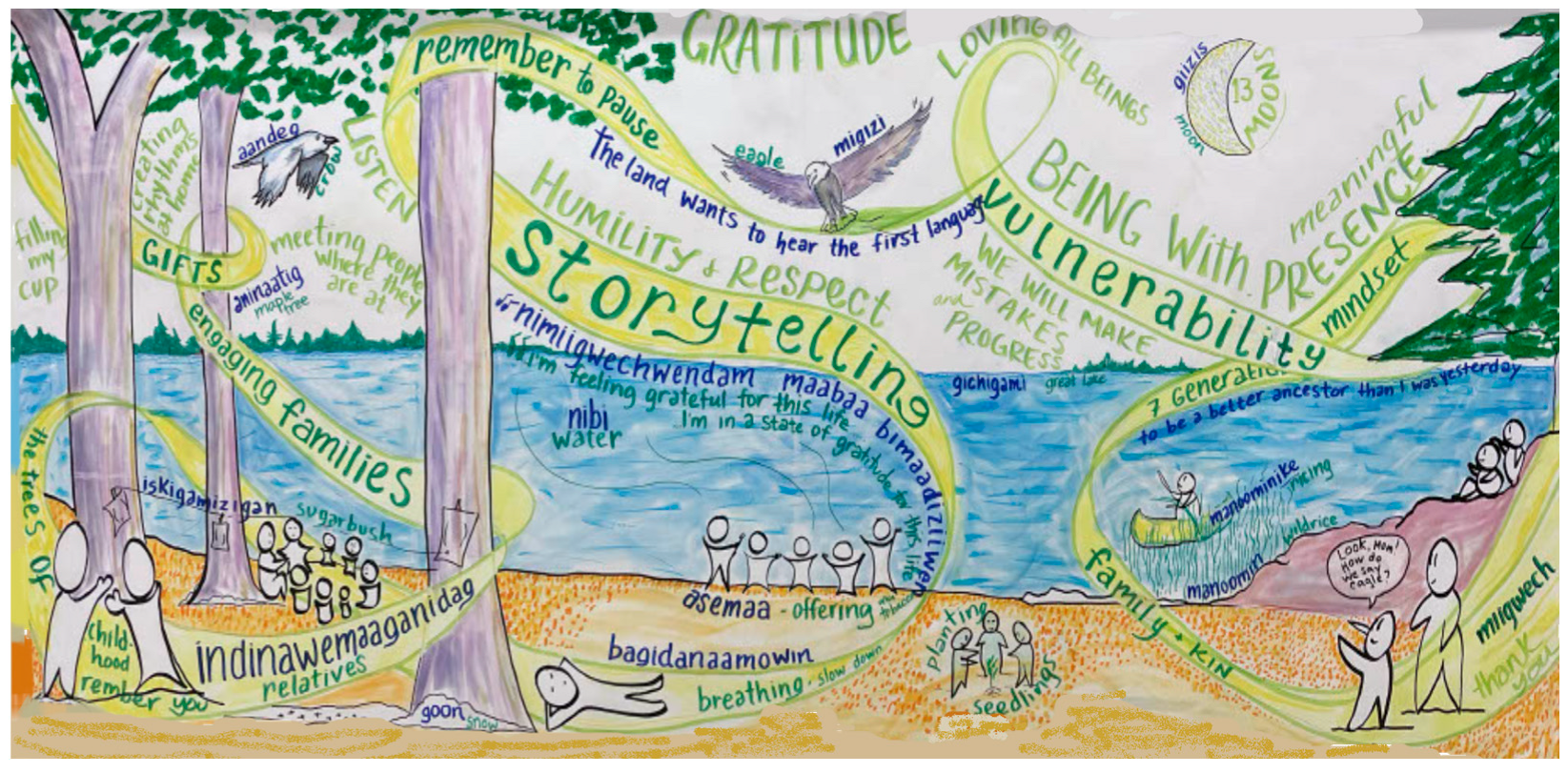

1.2. Project Description

When Anishinaabek share traditional teachings and stories, they are meant to reveal the nature of life and human nature, not just Anishinaabek culture. The stories teach us what it means to be alive, and anyone can learn from them if they listen carefully. The building of responsibility to self, relations, community, and life has never been more significant than this time of ecological crisis that will require us to shift our consciousness ever more to attending to each other’s survival, quality of life, and the protection of endangered species and habitats, including our own. Indigenous education is in line with the movement that many are calling the ‘great turning’. The time is right for the strengths and gifts of Indigenous education to be embraced by others. To integrate all learners in relation to one another and all life, in the pursuit of full human development, is an inclusive education”.[28] (para 8)

1.3. Evaluation Purpose

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Evaluation Approach

2.2. Data Collection Methods

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

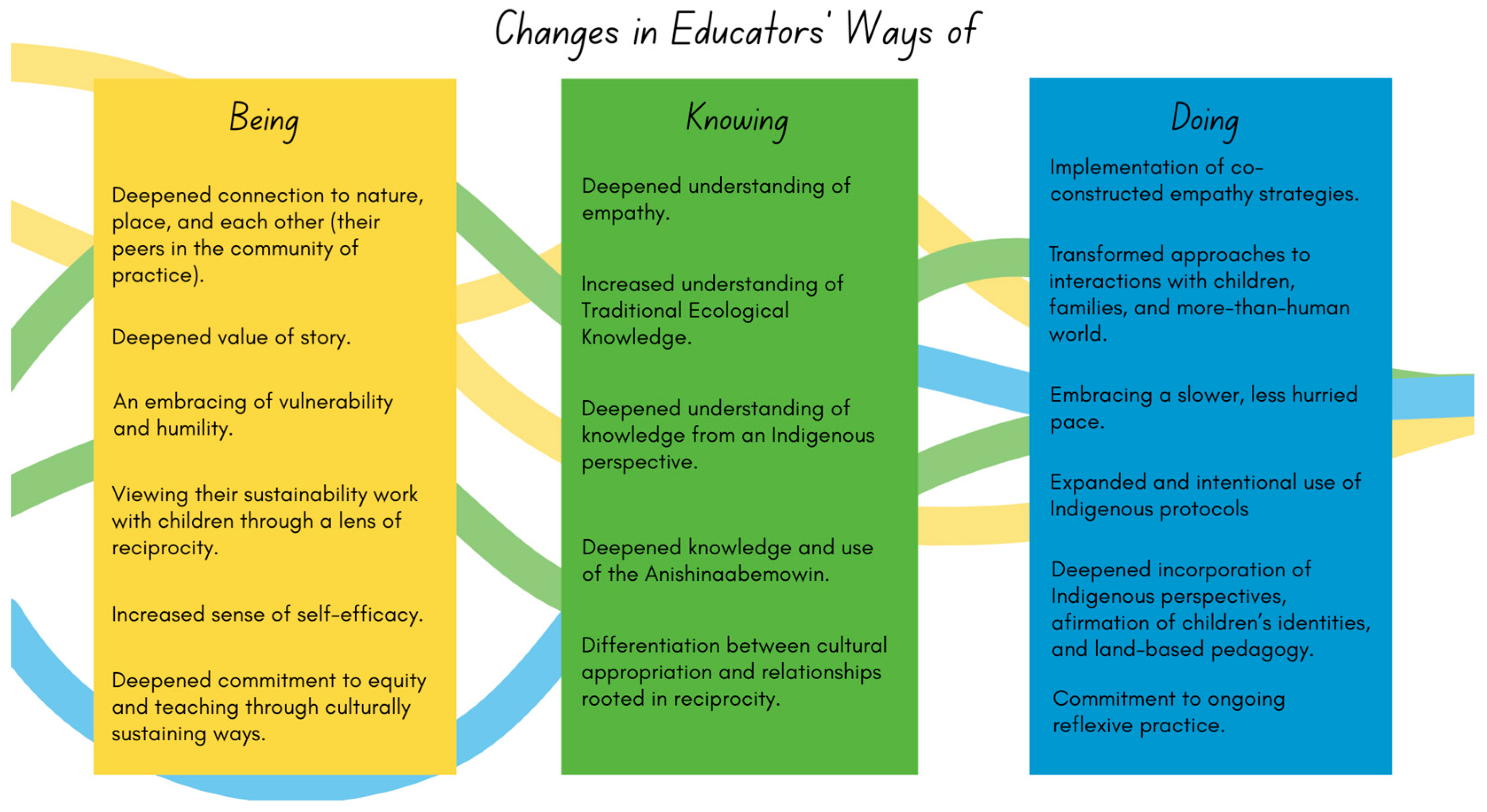

3.1. Changes in Educator Participants’ Ways of Being (Dispositional/Affective Changes)

- Deepened connection to nature, place, and each other (their peers in the community of practice). As one educator expressed, “I would say that this community of practice has given me reason to think more of the beings that we’re sharing our space with, within our forest, … to give the spirits of our forest—the rocks, the trees, the mosses—emotions and feelings and to respect the space that they occupy…” Or as another expressed, “We are not alone; we are not meant to do this work alone.” These deepened connections may be attributed in part to an “empathy perspective” that developed and became the framing for viewing these connections with the human and more-than-human world—from the recognition that each brings knowledge and experience to the group, inspired by their connection with other teachers doing this work, and informed by Indigenous traditions of relationality, where the world is understood through relationships with humans, other living beings, and the land itself. This is illustrated by one educator’s statement that “My relationship with land, nature, animals, and children has changed and shifted. I see others in relationship differently, and I’m grateful for this community. I am a better human, teacher, partner, and friend by continuing to immerse this work into my practices at work and beyond. I am a better ancestor than I was yesterday.”

- Deepened valuing of story. Across educators’ responses and sources of data, there was a strong sense of the importance of story—the story of the land they are on, and how it is being told and shared with children and with their community. There was also an awareness of how the story of place moves through their community, and how story is woven into their hearts. For example, one educator stated how participation prompted “learning more about my own story and how to tell it” as well as “deep reflection on the place that I work, live, and teach.” Educators expressed an awareness and valuing of stories that are unfolding, unfinished, and painful—how to be a part of telling a new story. Additionally, they expressed a deepened valuing of the role of story, not just in helping children learn but also in helping children “know who they are” and affirming their cultural identities.

- An embracing of vulnerability and humility. As one educator stated, “We are coming from this earnest place of growth and trying to do better.” And as expressed by another, “This learning community has provided a safe place to learn, share, make mistakes, and grow as an educator.” The theme of vulnerability surfaced across many participants, indicating, “that our hearts are in the right place, and we are willing to learn from our mistakes, and we are committed to continuing this work.” Educators also expressed valuing humility as a way to stay in relationship and as flowing from gratitude. One educator offered a remarkable demonstration of vulnerability and humility, where, in real time during a conference panel discussion, she shared that she had just realized her mistaken word use and modeled correcting her mistake and learning.

- Viewing their sustainability work with children through a lens of reciprocity. Educators frequently alluded to seeing beauty in work at hand and feeling deeply grateful for it: “We have been given many gifts…stories, time, presence, nourishment, teachings…gifts from each other, from Indigenous Elders, from the community. And for this experience, I think I speak for us all in saying we feel deep gratitude.” From those feelings of gratitude and joyfulness has emerged a lens of reciprocity as they approach their sustainability land-based teachings with children. As another expressed, “This way of seeing the world…recognizing resources and experiences as gifts…feeling a deep sense of gratitude…wanting to show and give respect/reciprocity…then moving to action…highlights the interconnected relationships we can hold and leads to sustainability.”

- Increased sense of self-efficacy. Educators were in strong agreement regarding a greater feeling of self-efficacy in their teaching practice, including centering their relationship with the land in their teaching, engaging appropriately and authentically in outdoor learning on and with Indigenous land and Indigenous peoples, and practicing reciprocity with the land, elders, and community. In the words of one participant, “I feel more confident that I can do this work even though it is hard and scary, and I may stumble because I have an entire community of teachers walking the same journey alongside me.”

- Deepened commitment to equity and teaching through culturally sustaining ways. This sentiment was shared by many of the educators. It is expressed well in the following articulation: “We are all moving toward building a stronger, more beautiful community by acknowledging the truths of the past and present and committing to intentionally doing better. We have created a community, one in which we can lean on each other, listen to one another, and cultivate ideas and ways of knowing to then implement in our own settings.” Another expressed feeling as though she was “part of a movement, a group of educators working together, perhaps implementing individually, to be more equitable, trauma-informed, and culturally competent” rippling outward into “families that feel welcomed and validated.”

3.2. Changes in Educator Participants’ Knowing (Cognitive Changes)

- Deepened understanding of empathy. Many educators alluded to not only greater understandings of empathy, deepened through engaging with Indigenous perspectives, but also of empathy’s importance in early childhood and of children’s capacity for empathy, as well as ways in which empathy can be supported. Educators also described a deepened understanding of the connection between empathy and reciprocal, respectful relationships with all of our human and more-than-human relatives and the power of empathy to foster community. They also expressed new understandings of how empathy and connectedness to nature are related and mutually reinforcing, as well as how empathy supports, but also flows from, a sense of place. As one educator participant expressed, “My framework for empathy has deepened in my teaching practice, for sure, but even in my relationships with my family, and with my friends, and with my relationship with nature, and my understanding of the non-human relatives that I’m with every day.”

- Increased understanding of Traditional Ecological Knowledge, knowledge of their local place, and the Indigenous peoples and traditions of this place. Indigenous and non-Indigenous educators alike expressed a deepened understanding of not only knowledge of Indigenous perspectives and the stories of their local place, but also of the importance of Indigenous knowledge in our collective efforts toward a more sustainable future. As one educator expressed, “We deepened our understanding of the importance of respect, relevance, reciprocity, and responsibility.”

- Deepened understanding of knowledge from an Indigenous perspective. Educators also expressed an expansion in their understanding of knowledge as something that can be held by an individual and a community, often both. From this perspective, knowledge is deeply grounded in place, connected to the land, and is a process, rather than a thing. Educators expressed understandings such as “this land, all land, is alive and has wisdom to share;” “knowing can be held by an individual, a community, and often by both;” “knowing is connected to perspective and experience;” “truth is not held in one, but created by many;” and “knowledge is a gift.”

- Deepened knowledge and use of Anishinaabemowin, the language of the land. Educators have come to understand that the Anishinabe language is a gift to the land, that the land loves to be spoken to in its first language. Educators have demonstrated an increased knowledge of Anishinaabemowin words and increased confidence in the use of those words. Beyond engagement with the community of practice, several educators have enrolled in local and online Anishabemowin classes to deepen their knowledge and use of the language. One educator relayed a story of encountering an eagle with her child and remarking on what a special gift it is to see an eagle. The young child thought quietly for a moment and then, unprompted, asked how to say eagle in Ojibwe, as the educator had been modeling the use of other Anishinabe words in their day-to-day interactions. While the educator did not know the word for eagle at that moment, she responded that they would look it up together. This educator shared with the community of practice that she felt the work she was doing to share the Anishinabe language was taking root, evidenced by this child’s curiosity.

- Differentiation between cultural appropriation and relationships rooted in reciprocity. While many educators initially approached Indigenous content with apprehension due to concerns about cultural appropriation, participation in the community of practice led to a more nuanced understanding of how to engage respectfully with Indigenous ways of knowing. Guided by Indigenous mentors and scholars, participants came to recognize that Indigenous education holds immense value for all children, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous. Rather than centering concerns around appropriation, the emphasis shifted toward an ethical responsibility to honor and appropriately convey the teachings received. This included explicitly naming the sources of Indigenous knowledge, including who shared the teachings, as well as the contexts in which that sharing occurred [49]. Such practices signal an intentional move toward relational accountability and reciprocal engagement. Additionally, educators expressed recognition of the importance of “doing this work in relationship with” Indigenous mentors, partners, parents, and community members.

3.3. Changes in Educator Participants’ Doing (Behavioral Changes)

- Implementation of co-constructed empathy strategies deepened through engagement with Indigenous perspectives. Educators described changes in the ways they interacted with children in their care. These changes included increased listening and observing, more storytelling, greeting more-than-human relatives by their Anishinaabemowin name, modeling the honorable harvest [50] (harvesting in respectful ways that further sustainability and reciprocity), and letting children ask questions rather than asking the questions themselves. They indicated modeling empathy, coaching, and supporting children as they practice empathy, affirming empathy expressions from children, and holding space for children to notice, wonder, inquire, and choose their own empathy actions. As one educator noted, “We are defining and redefining our approaches, strategies, and values. We’re redefining what it means to be an educator to all children and all relatives.” This educator continued her reflection, stating, “Year after year, we have access to these amazing, beautiful, capable young children. We can help plant the seeds of empathy and understanding and create a connection to the land, helping them see themselves in both the smaller and bigger stories of this world and their own lives and all our relatives.”

- Transformed interactions with children, families, and the more-than-human world. Participants described notable shifts in how they engage with children, characterized by deeper listening, greater emotional attunement, and an increased willingness to be open and vulnerable. Educators reported approaching their work with dispositions of curiosity, gentleness, and empathy, which supported children in developing and expressing empathy in return. Their pedagogical stance increasingly reflected a relational and reciprocal view of teaching, including learning alongside children about more-than-human relatives. Educators also extended this relational approach to families, sharing stories of children’s empathy encounters, communicating about Indigenous teachings and traditions, and creating programming to engage families more deeply in this work. One educator, upon reflecting on these transformed interactions, described them as allowing her and her peers in the community of practice to be “better people, in all areas of life, and kinder and gentler across the board.”

- Embracing a slower, less hurried pace. One of the most significant behavioral shifts involved embracing a slower, more intentional rhythm throughout the day. Teachers described making space for what our Indigenous mentor called the “Indigenous pause”—a practice of waiting, watching, and deeply listening before responding or acting. This shift allowed educators to observe more carefully, follow children’s lead, and respond more thoughtfully to both human and more-than-human encounters. Educators reported using fewer transitions, minimizing whole-group time, and trusting the pace of the child. In the words of one educator, “We don’t rush to fix anymore. We sit in it together.” And another described this slower pace allowed them to “hold significant space for nature as teacher.”

- Expanded and intentional use of Indigenous protocols. Educators also spoke of increased understanding of Indigenous protocols, particularly what respectful engagement of Indigenous family and community members in schools and programs entails, as well as protocols for including Elders in classrooms. As one educator noted, “I learned the importance of relationships. I turned to and really received guidance from a depth of Ojibwe mentors, and my community of practice group walked this journey with me, too. I also learned to turn to Indigenous parents and community members in education, to artists, writers, and storykeepers. I worked to be especially respectful and patient along the way...for example, asking our Indigenous mentor how to ask knowledge holders, and which questions to ask and how to ask in a good way, while practicing reciprocity through gifts, shared food, and monetary support for shared time, travel, and teaching.” Educators also indicated offering asema (tobacco) to Indigenous knowledge keepers and working with the children in their care to prepare gifts to share with Indigenous speakers to honor the knowledge and stories offered.

- Deepened incorporation of Indigenous perspectives, affirmation of children’s identities, and land-based pedagogy. Educators reported a growing ability to meaningfully integrate Indigenous perspectives and knowledge into their teaching while affirming children’s full identities, particularly their cultural identities. This shift was accompanied by more intentional efforts to recognize children’s strengths and center their agency through land-based pedagogy and environmental inquiry. Participants described learning with and from children, including moments when Indigenous children were invited to share cultural knowledge in ways that were voluntary and non-tokenizing. For example, when one educator asked the class what they knew about asema (tobacco), an Indigenous child confidently shared an extended explanation about asema’s ceremonial and everyday roles in expressing gratitude, prayer, and respect—demonstrating a depth of understanding and cultural pride that was affirmed by the classroom community. This pedagogical moment highlighted the role of the educator not as the sole authority but as a facilitator of reciprocal learning rooted in trust, respect, and relational accountability. These practices reflect a pedagogical orientation that positions land and children as co-teachers and affirms Indigenous presence and knowledge as vital to early learning.

- Commitment to ongoing reflexive practice. Educators continued to reflect critically on their use of empathy and land-based teaching strategies, asking questions about how these approaches were working and how they might evolve. They described wondering about children’s responses, how to deepen their learning, and how to refine their approaches to better support children’s relationships with one another, their communities, and the natural world. Educators emphasized the importance of time and space to reflect not only individually, but in community, and that in doing so, a sense of the collective impact of the community of practice arises. This reflexive stance underscored the dynamic nature of the learning process and the educators’ commitment to continual growth.

3.4. Educator Insights on the Value and Effectiveness of the Community of Practice

- A trusting, relational learning community. The community of practice was consistently described by educators as a safe, nurturing, trusting space that fostered vulnerability, authenticity, and deep connection—characteristics that were not often experienced in more traditional professional development settings. This relational environment enabled honest dialogue, risk-taking, and personal growth. One educator shared, “To be in the safekeeping of our small and vulnerable sharing space, my colleagues held space for me, and helped to reassure and reflect with me how the work I am doing is still so very present. But that it is also ok to honor stillness.” Educators reflected that the community of practice fostered a culture of care and reciprocity that encouraged them to slow down, reflect, and support one another, reinforcing the understanding of learning as deeply social and relational.

- Learning as a social, slow, and reflective process. Many educators noted the importance of time, slowness, and community as conditions for deep learning. Over the three years of the community of practice, they engaged in a process of unlearning that stepped outside of Western conceptualizations of urgency, in favor of a slower, more caring, and intentional approach, as noted above. Educators reported that the community of practice affirmed the idea that learning happens in and through relationships with people, place, and self, and that this learning unfolds and deepens when given adequate time and space for reflection. One educator reflected, “We talk so much about slowing down in the community of practice, and I have worked hard to embrace this in my world at home and school.” This educator further expressed that by doing so, she feels more balanced and also sees that her children also find more balance.

- Sustained motivation and accountability. Educators reported that consistent meetings across the three years supported continuing and built momentum, countering the isolation some educators feel in their day-to-day settings, where they may be one of only a few educators. The structure and cadence of the community of practice meetings created a sense of accountability, both externally and intrinsically driven by a desire to show up for the group and contribute meaningfully, as one educator articulated, this accountability translated directly into deepened action “I noticed that when I saw another community of practice meeting on the calendar, I wanted to be able to share my progress with my peers. It engaged me and motivated me to DO more. I wouldn’t have accomplished a fraction of what I did this last year without the support of this community.”

- Inspiration and modeling within the group. Core to the community of practice approach is the affirmation that each participant has something meaningful to contribute and to learn from and with the community. Educators reported learning not only from Indigenous mentors but also from witnessing the significance of fellow community of practice members’ work and growth. Peers served as models of practice, especially when navigating how to respectfully share Indigenous perspectives with children and families. As one educator shared that the biggest support in her practice of Indigenous ways of being–knowing–doing had been witnessing the work of a fellow community of practice member, she reflected that this peer “has been the most amazing example of how to bring these Indigenous ways into the classroom in so many different ways every day. I see her deeply collaborating with Indigenous family and community members and sharing the journey behind what she has been doing in the small group. Witnessing the impact her intentional work has had on her students has given me so much more confidence in my own practice.”

- Identity development, confidence, and commitment. Participation in the community of practice supported educators in deepening their professional identities, building confidence, and clarifying their commitment to equity- and relationship-based teaching. Rather than offering prescriptive solutions, the community of practice created space for educators to engage vulnerably with complex topics, reflect on their practice, and be affirmed by peers. These relational experiences fostered confidence and grounded educators in their values, even in moments of stillness or uncertainty. Educators also described a renewed sense of purpose and direction, not only individually but as part of a larger movement toward more just and culturally sustaining early childhood education. Witnessing one another’s practices, particularly those grounded in Indigenous ways of knowing, strengthened their belief in what was possible. As one participant wrote, “Hearing the experiences and examples from other programs also helps show me how to move in the right direction one step at a time.” This collective identity was not only sustaining but motivating. Educators spoke of carrying the work into their classrooms and communities with a sense of clarity, courage, and commitment to “doing better for children, families, the land, and future generations.”

- Commitment to broader impact and rippling effects. Educators described the community of practice teachings as gifts they now carry forward, not only in their classrooms and programs, but in their personal lives with family, friends, and the broader community. They have reflected a sense that the community of practice is not an isolated professional learning experience, but part of wider and larger work toward sustainability, healing, and justice. One educator expressed it this way: “We are now sharing our gifts, our teachings, our experiences within our community circles. The rippling effects are powerful.”

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Discussion of Findings

4.3. Implications

- Professional learning that recognizes the social and relational nature of learning. The findings highlight the value of professional learning that affirms the social and relational dimensions of knowledge construction. Rather than positioning educators as passive recipients of externally determined knowledge, the community of practice approach facilitated reciprocal learning relationships, where participants were recognized as co-constructors of meaning and holders of diverse expertise. One educator noted, “It is through connection that this work and this way of being gets strengthened and is long-lasting. Without others, the fire would fizzle. We need to grow in this work together, and we are doing this work together.” This reflection underscores the role of collective engagement in sustaining professional growth. In recognizing learning as emergent and relational, the community of practice approach also challenged conventional, linear models of professional development [51]. Instead of advancing toward pre-defined goals through fixed stages, participants described an unfolding process shaped by ongoing dialogue, reflection, and shared inquiry. As one participant reflected, “I realized that Indigenous perspectives weren’t so linear, but instead had more of a compounding reality that contains so many things all at once. And now, I’m finding that the edges of what I am trying to do in my teaching are expanding in that same way, and I’m starting to feel much more comfortable with the idea that I don’t know what’s in all those directions.” This orientation invites a more expansive, non-linear view of both pedagogy and professional growth—one that opens space for complexity, emergence, and the honoring of multiple ways of knowing.

- Professional learning that affords sustained engagement and reflection. The findings suggest that meaningful professional learning is supported by sustained engagement and opportunities for intentional reflection. Rather than prioritizing efficiency or rapid implementation, the community of practice moved at a deliberately slow and thoughtful pace, allowing educators to pause, process, and integrate new ideas into their practice over time. This slower approach fostered deeper connection and authenticity, creating the conditions for transformative learning. One educator articulated this impact, describing the experience as one of being “part of a movement, a group of educators working together to be more equitable, trauma-informed, and culturally competent.” The sustained duration of the community enabled such shifts to take root, with participants noting how this gradual and collective approach to learning fostered more inclusive, welcoming environments for families. In this way, the work was described not as isolated or episodic, but as expansive and ongoing, “rippling outward” into relationships with children, families, and communities.

- Professional learning that supports identity development, confidence, and commitment. Educators did not passively receive knowledge; they actively engaged in listening, reflecting, sense-making, and co-constructing meaning. This collegial inquiry unfolded within a trusted relational space, where the knowledge shared by Indigenous mentors and learning materials was held alongside the internal wisdom and lived experiences of participants. As a result, identity, confidence, and commitment emerged, linking new understandings to sustained shifts in practice. Participants articulated how their participation in the CoP became part of who they are, both as educators and as individuals. One teacher shared, “It has become a piece of who we are—there is no going backward.” This suggests that professional learning grounded in identity development fosters enduring transformation, not only by deepening knowledge but by reshaping how educators see themselves and their work. As such, time, trust, and community are not peripheral supports: they are the foundation of change.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Samuelsson, I.; Kaga, Y. The Contribution of Early Childhood Education to a Sustainable Society; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Power, T.G.; O’Connor, T.M.; Orlet Fisher, J.; Hughes, S.O. Obesity risk in children: The role of acculturation in the feeding practices and styles of low-income Hispanic families. Child. Obes. 2015, 11, 715–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Association for the Education of Young Children. NAEYC Early Learning Program Accreditation Standards and Assessment Items; NAEYC: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Alim, H.S.; Paris, D.; Wong, C.P. Culturally sustaining pedagogies: A critical framework for centering communities. In Handbook of the Cultural Foundations of Learning; Nasir, N.S., Lee, C.D., Pea, R., McKinney de Royston, M., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 261–276. [Google Scholar]

- Keith, H.R.; Kinnison, S.; Garth-McCullough, R.; Hampton, M. Putting Equity into Practice: Culturally Responsive Teaching and Learning; Equity-Minded Digital Learning Strategy Guide Series; Every Learner Everywhere: Boulder, CO, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Paris, D.; Alim, H.S. Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies: Teaching and Learning for Justice in a Changing World; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, & Medicine. A New Vision for High-Quality Preschool Curriculum; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Hardie, Y.; Kamara, Y. Shaping Futures Arts, Culture, and Education as Drivers of Sustainable Development; The ACP-EU Culture programme: Brussels, Belgium, 2024; Available online: https://www.acp-ue-culture.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Shaping-Futures-Arts-Culture-and-Education-as-drivers-of-sustainable-development-V9.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- United Nations. Transforming Education: An Urgent Political Imperative for Our Collective Future. Vision Statement of the Secretary-General on Transforming Education; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/2022/09/sg_vision_statement_on_transforming_education.pdf (accessed on 22 May 2023).

- United Nations. Report on the 2022 Transforming Education Summit; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/report_on_the_2022_transforming_education_summit.pdf (accessed on 22 May 2023).

- International Commission on the Futures of Education. Reimagining our Futures Together: A New Social Contract for Education; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2021; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000379707 (accessed on 22 May 2023).

- Stanistreet, P. The future is not what it used to be. Int. Rev. Educ. 2023, 69, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bascopé, M.; Perasso, P.; Reiss, K. Systematic Review of Education for Sustainable Development at an Early Stage: Cornerstones and Pedagogical Approaches for Teacher Professional Development. Sustainability 2019, 11, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikane, J.H.; Høydalsvik, T.E.L. Teachers’ Expressed Understandings Concerning Sustainability in the Norwegian ECE Context. Environ. Educ. Res. 2023, 30, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine & National Research Council. Transforming the Workforce for Children Birth Through Age 8: A Unifying Foundation; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK310532/ (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Sellars, M. Reflective Practice for Teachers, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Virmani, E.; Hatton-Bowers, H.; Lombardi, C.; Decker, K.; King, E.; Plata-Potter, S.; Vallotton, C. How are preservice early childhood professionals’ mindfulness, reflective practice beliefs, and individual characteristics associated with their developmentally supportive responses to infants and toddlers? Early Educ. Dev. 2020, 31, 1052–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, C.; Austin, L.J.E.; Powell, A.; Jaggi, S.; Kim, Y.; Knight, J.; Muñoz, S.; Schlieber, M. Early Childhood Workforce Index—2024; Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2024; Available online: https://cscce.berkeley.edu/workforce-index-2024/ (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- Byington, T.; Muenks, S.R. Professional Development Needs and Interests of Early Childhood Education Trainers. Early Child. Res. Pract. 2011, 13, n2. [Google Scholar]

- Siry, C.; Martin, S. Facilitating reflexivity in preservice science teacher education using video analysis and co-generative dialogue in field-based methods courses. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2014, 10, 481–508. [Google Scholar]

- Wenger, E.; McDermott, R.; Snyder, W. Cultivating Communities of Practice: A Guide to Managing Knowledge; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Blankenship, S.; Ruona, W. Professional Learning Communities and Communities of Practice: A Comparison of Models Literature Review. In Proceedings of the Academy of Human Resource Development International Research Conference in the Americas, Indianapolis, IN, USA, 28 February–4 March 2007; Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED504776 (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Hunter, M.A.; Aprill, A.; Hill, A.; Emery, S. Reorienting Teacher Professional Learning (Partnerships for Change). In Education, Arts and Sustainability; Springer Briefs in Education; Springer: Singapore, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seashore, K.; Anderson, A.; Riedel, E. Implementing Arts for Academic Achievement: The Impact of Mental Models, Professional Community and Interdisciplinary Teaming; Center for Applied Research and Educational Improvement, College of Education and Human Development, University of Minnesota: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2003; Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/11299/143717 (accessed on 9 July 2024).

- Lave, J. Situating learning in communities of practice. In Perspectives on Socially Shared Cognition; Resnick, L.B., Levine, J.M., Teasley, S.D., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Wood-Krueger, O. Restoring Our Place: An Analysis of Native American Resources Used in Minnesota’s Classrooms; Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community: Prior Lake, MN, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Restoule, J. Everything Is Alive and Everyone Is Related: Indigenous Knowing and Inclusive Education; Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2011; Available online: https://www.federationhss.ca/en/blog/everything-alive-and-everyone-related-indigenous-knowing-and-inclusive-education (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Korteweg, L.; Gonzalez, I.; Guillet, J. The stories are the people and the land: Three educators respond to environmental teachings in Indigenous children’s literature. Environ. Educ. Res. 2010, 16, 227–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czap, N.V.; Czap, H.J.; Khachaturyan, M.; Burbach, M.E.; Lynne, G.D. Experiments on empathy conservation: Implications for environmental policy. J. Behav. Econ. Policy 2018, 2, 71–77. [Google Scholar]

- Berenguer, J. The effect of empathy in proenvironmental attitudes and behaviors. Environ. Behav. 2007, 39, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, N.; Guthrie, I.K.; Murphy, B.C.; Shepard, S.A.; Cumberland, A.; Carlo, G. Consistency and development of prosocial dispositions: A longitudinal study. Child. Dev. 1999, 70, 1360–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ernst, J.; Underwood, C.; Nayquanabe, T. Everyone has a piece of the story: A Community of Practice approach for supporting early childhood educators’ capacity for fostering empathy in young children through nature-based early learning. Int. J. Early Child. Environ. Educ. 2023, 11, 34–62. [Google Scholar]

- Reconciliation Through Indigenous Education Course Material. Available online: https://pdce.educ.ubc.ca/reconciliation-2/ (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- Hare, J. Foreword. In Troubling Truth and Reconciliation in Canadian Education: Critical Perspectives; Styres, S.S., Kempf, A., Eds.; University of Alberta Press: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2022; pp. vii–xi. [Google Scholar]

- Ernst, J.; Underwood, C.; Nayquonabe, T. Beyond Empathy: Wiijigaabawitaadidaa Niigaan Izhaayang (Moving Forward Together) toward Reconciliation through Indigenous Education in Early Childhood Environmental Education. Int. J. Early Child. Environ. Educ. 2025, 12, 50–63. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, D.; Comay, J.; Chiarotto, L. Natural Curiosity 2nd Edition: The Importance of Indigenous Perspectives in Children’s Environmental Inquiry; Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Underwood, C.; Nayquonabe, T.; Goodman, S.; Richtman, E.; Walker-Davis, S.; Whittaker, L. Breathing with the World: Building Reciprocal Relationships with Indigenous Peoples, Places, and Perspectives. In Proceedings of the Natural Start Alliance Annual Conference, Virtual Pre-recorded Panel, 14–17 July 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Buergelt, P.T.; Mahypilama, L.E.; Paton, D. The value of sophisticated Indigenous ways of being-knowing-doing towards transforming human resource development in ways that contribute to organizations thriving and addressing our existential crises. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2022, 21, 391–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Balbach, E.D. Using Case Studies to Do Program Evaluation; Stanford Center for Research in Disease Prevention, Stanford University School of Medicine: Stanford, CA, USA, 1999; Available online: https://www.betterevaluation.org/tools-resources/using-case-studies-do-program-evaluation (accessed on 2 January 2024).

- Equitable Evaluation Initiative & Grantmakers for Effective Organizations. Shifting the Evaluation Paradigm: The Equitable Evaluation Framework™, 2021. Available online: https://www.equitableeval.org/_files/ugd/21786c_7db318fe43c342c09003046139c48724.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2024).

- Wilson, S. What Is an Indigenous Research Methodology? Can. J. Nativ. Educ. 2001, 25, 175–179. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, J. Arts-based Research: Weaving Magic and Meaning. Int. J. Educ. Arts 2012, 13, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Chazdon, S.; Emery, M.; Hansen, D.; Higgins, L.; Sero, R. A Field Guide to Ripple Effects Mapping; University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2017; Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/11299/190639 (accessed on 21 January 2023).

- Ernst, J.; Underwood, C.; Wojciehowski, M.; Nayquonabe, T. Empathy capacity-building through a community of practice approach: Exploring perceived impacts and implications. J. Zool. Bot. Gard. 2024, 5, 395–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crabtree, B.F. Doing Qualitative Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, R.A. Analyzing and Reporting Focus Group Results; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Restoule, J.P.; Chaw-win-is. Old Ways Are the New Way Forward: How Indigenous Pedagogy Can Benefit Everyone; Canadian Commission for UNESCO’s Idea Lab: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kimmerer, R.W. Braiding Sweetgrass; Milkweed Editions: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Buysse, V.; Sparkman, K.; Wesley, P. Communities of practice: Connecting what we know with what we do. Except. Child. 2003, 69, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean-Coffey, J.; Cone’, M. Equitable Evaluation Framework™ Framing Paper: Expansion, 2023. Available online: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/tfr/vol15/iss3/ (accessed on 9 August 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ernst, J.; Underwood, C.; Nayquonabe, T. Empathy, Reconciliation, and Sustainability Action: An Evaluation of a Three-Year Community of Practice with Early Educators. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8686. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198686

Ernst J, Underwood C, Nayquonabe T. Empathy, Reconciliation, and Sustainability Action: An Evaluation of a Three-Year Community of Practice with Early Educators. Sustainability. 2025; 17(19):8686. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198686

Chicago/Turabian StyleErnst, Julie, Claire Underwood, and Thelma Nayquonabe. 2025. "Empathy, Reconciliation, and Sustainability Action: An Evaluation of a Three-Year Community of Practice with Early Educators" Sustainability 17, no. 19: 8686. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198686

APA StyleErnst, J., Underwood, C., & Nayquonabe, T. (2025). Empathy, Reconciliation, and Sustainability Action: An Evaluation of a Three-Year Community of Practice with Early Educators. Sustainability, 17(19), 8686. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198686