Low-Cost Angular-Velocity Measurements for Sustainable Dynamic Identification of Pedestrian Footbridges: A Case Study of the Footbridge in Gdynia (Poland)

Abstract

1. Introduction

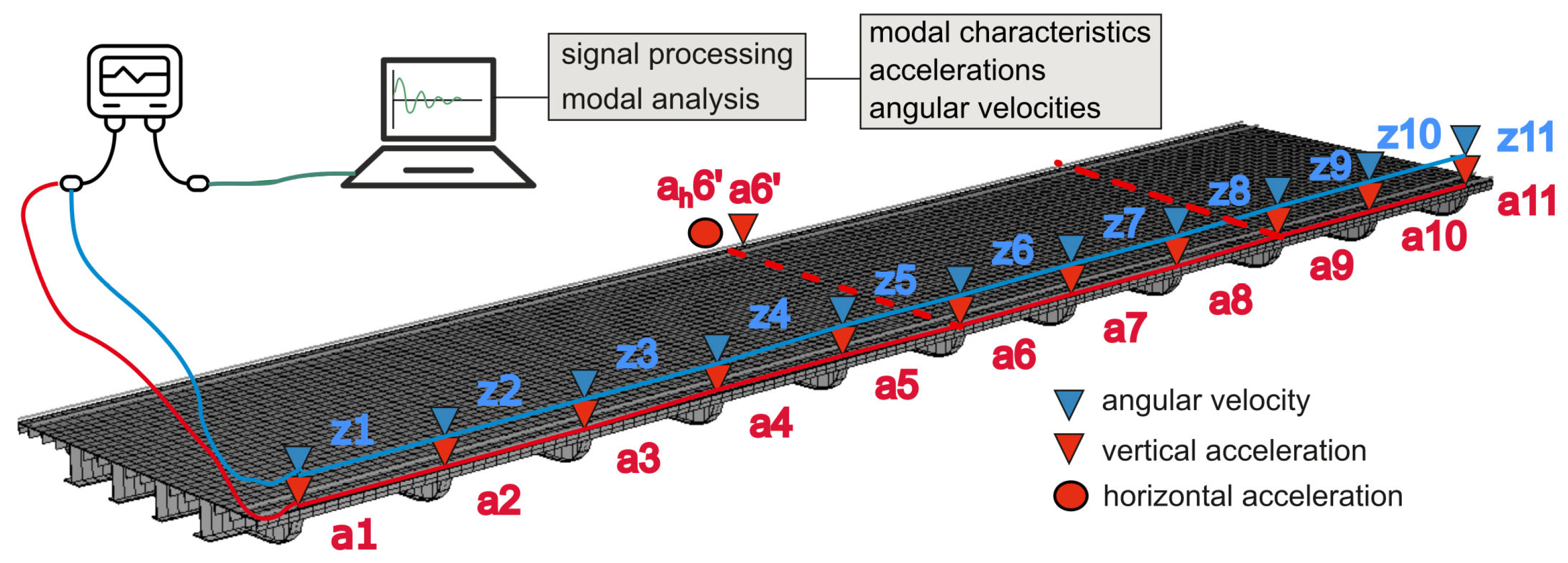

2. Materials and Methods

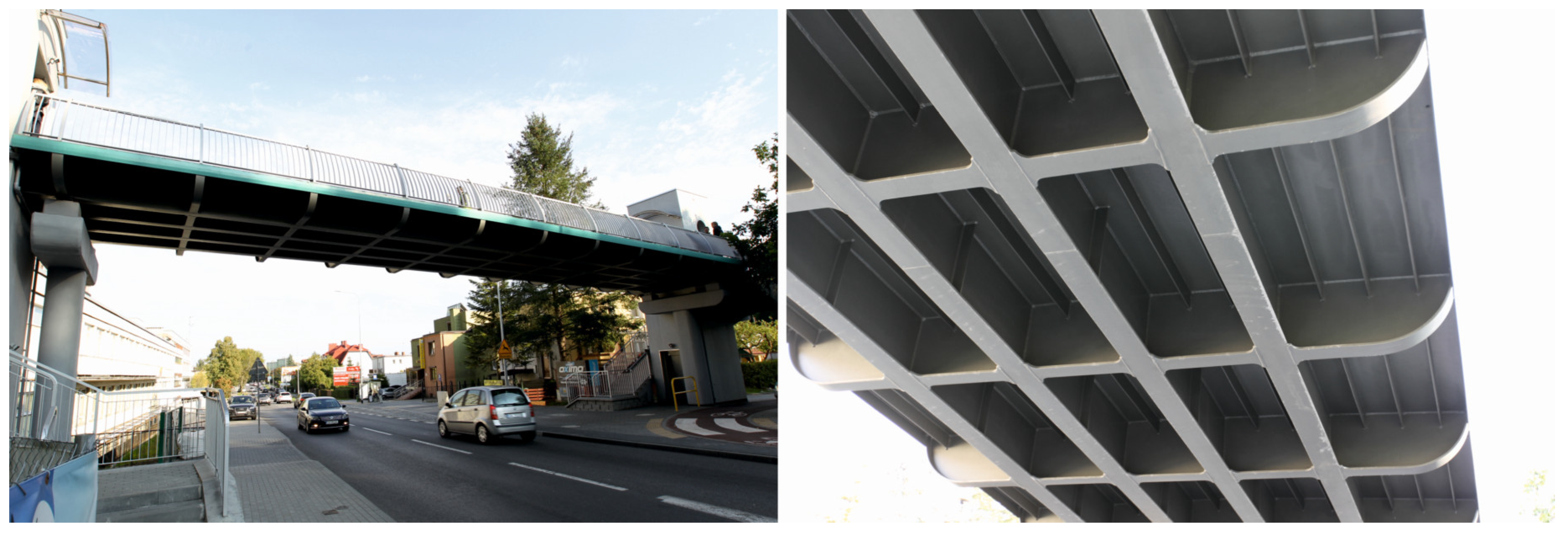

2.1. Footbridge Descriptions

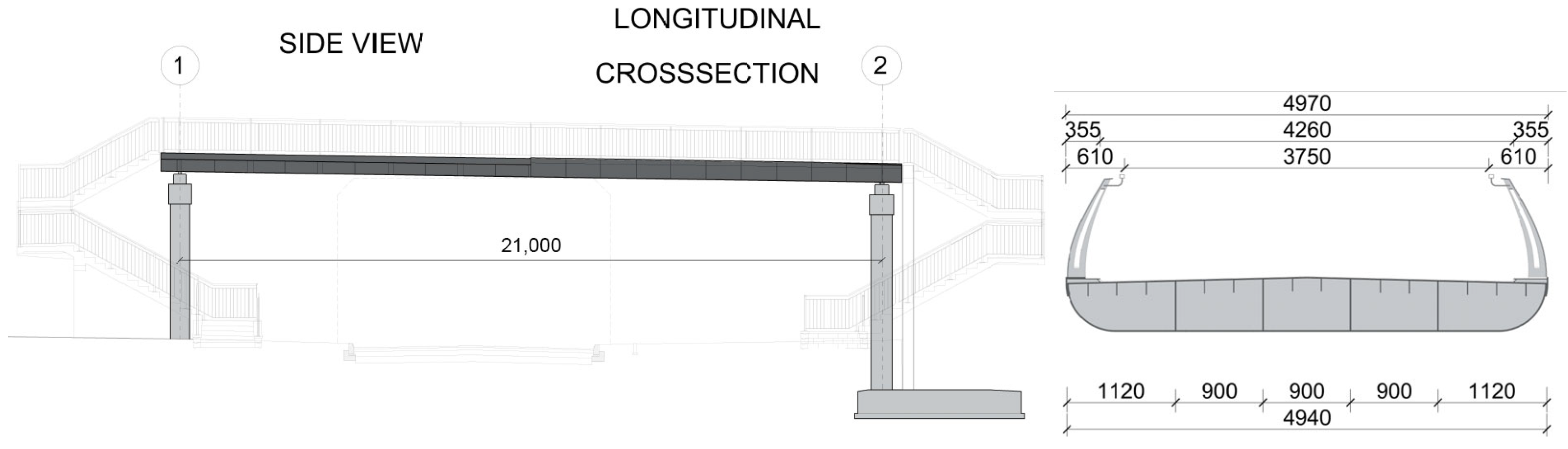

2.2. Experimental Procedures

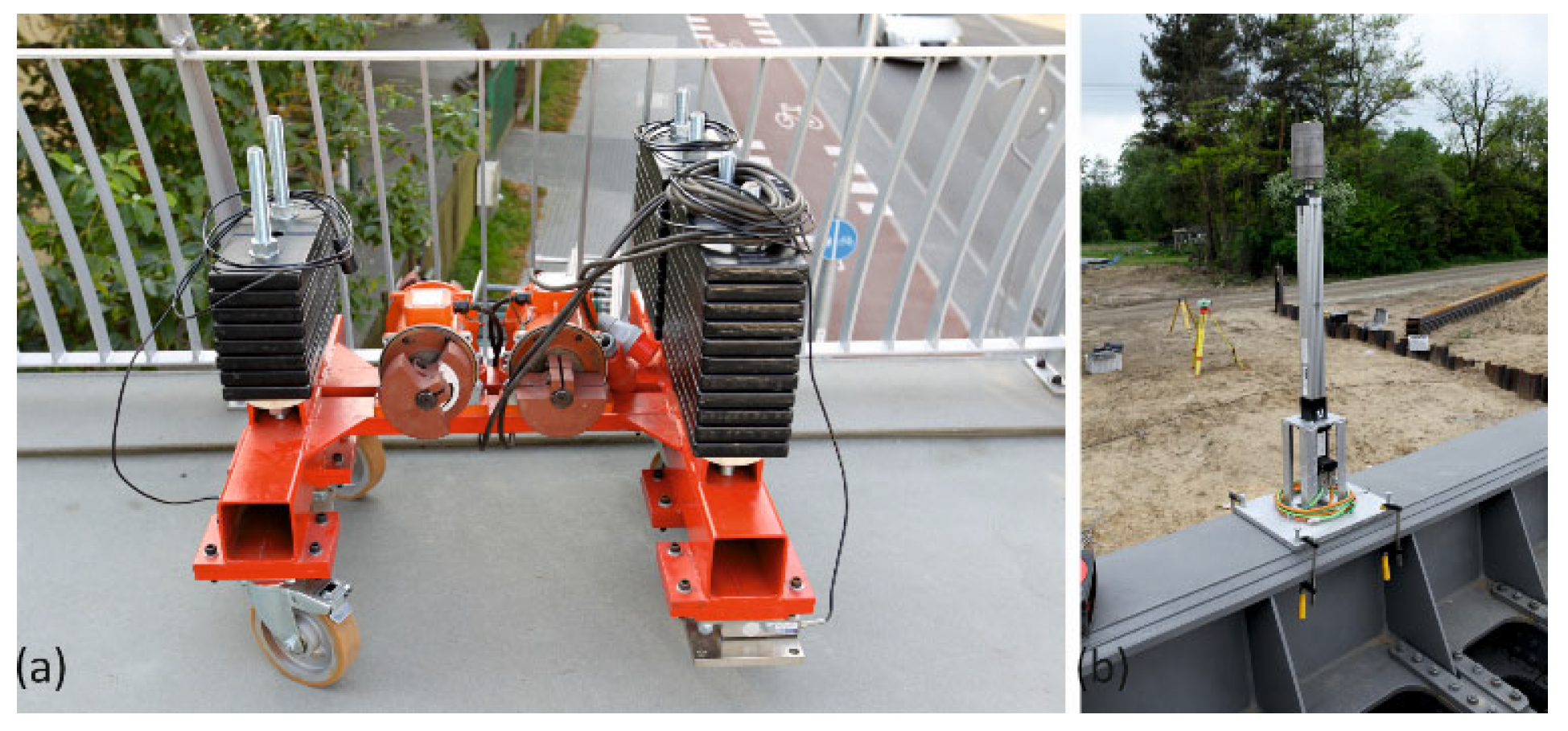

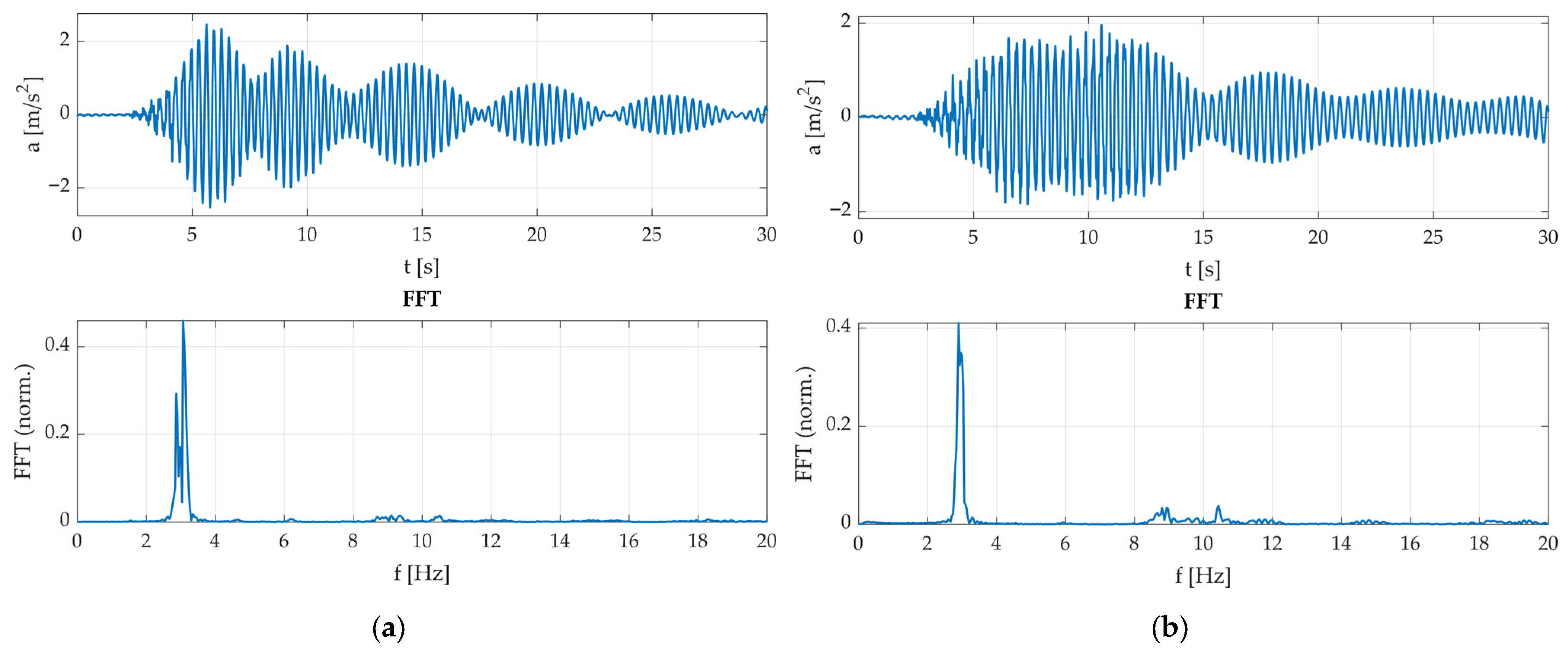

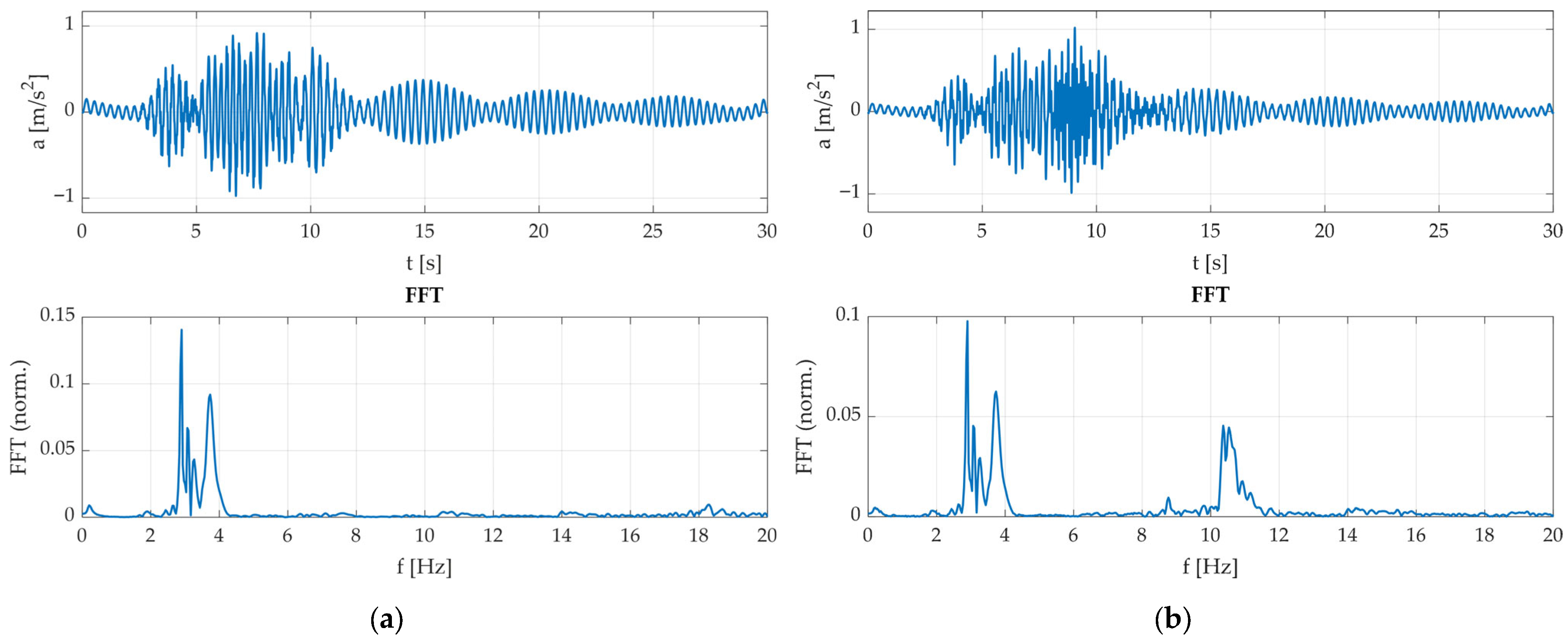

2.3. Excitation and Ambient Vibration In Situ Measurements

2.4. Tests with Walking Pedestrians

- free walking of 1, 3, and 6 pedestrians without synchronisation,

- fast synchronised marching of 1, 3, 6, and 9 pedestrians at resonance frequency,

- synchronised running of 1, 3, and 6 pedestrians at resonance frequency,

- synchronised jumping of a group of 6 pedestrians at the resonance frequency.

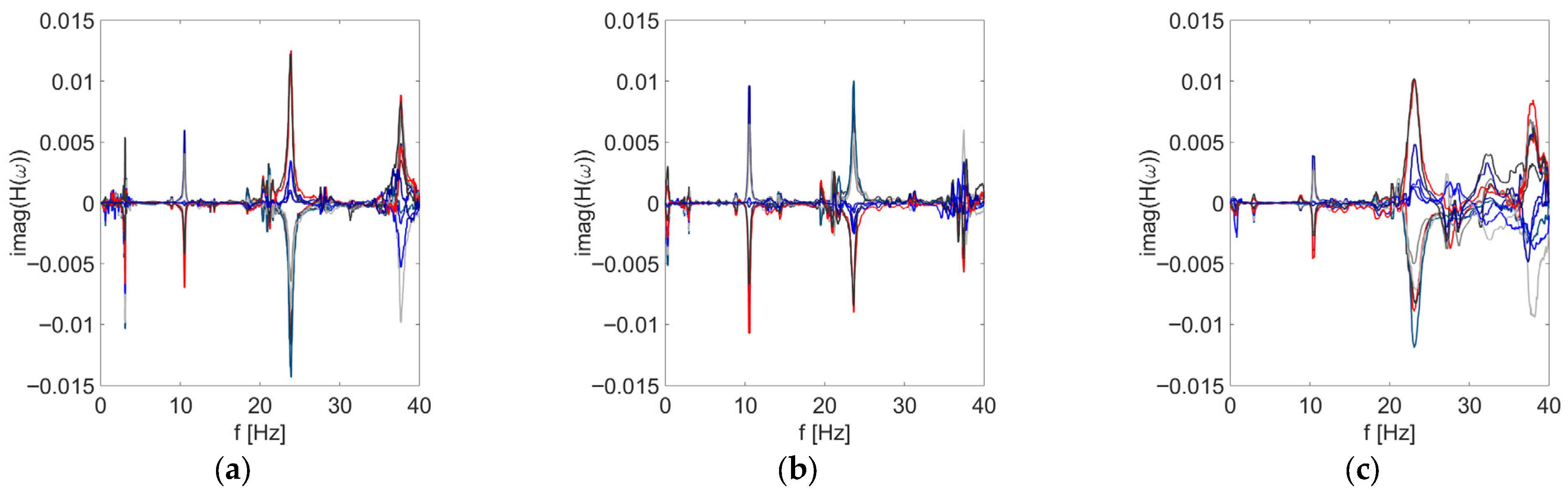

2.5. Modal Parameters Identification Techniques

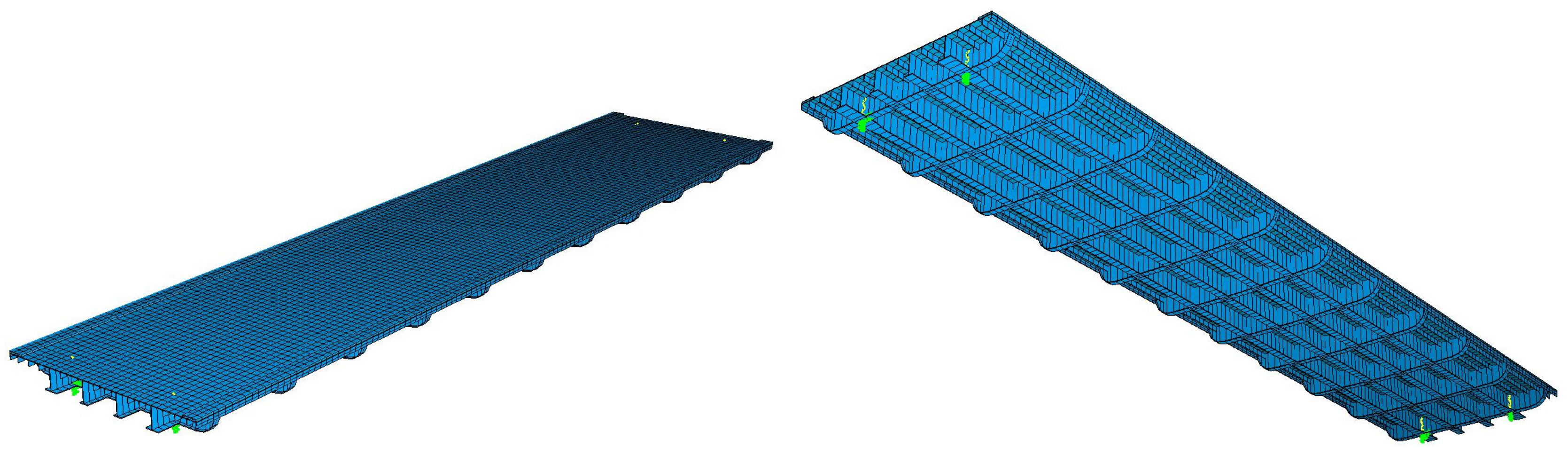

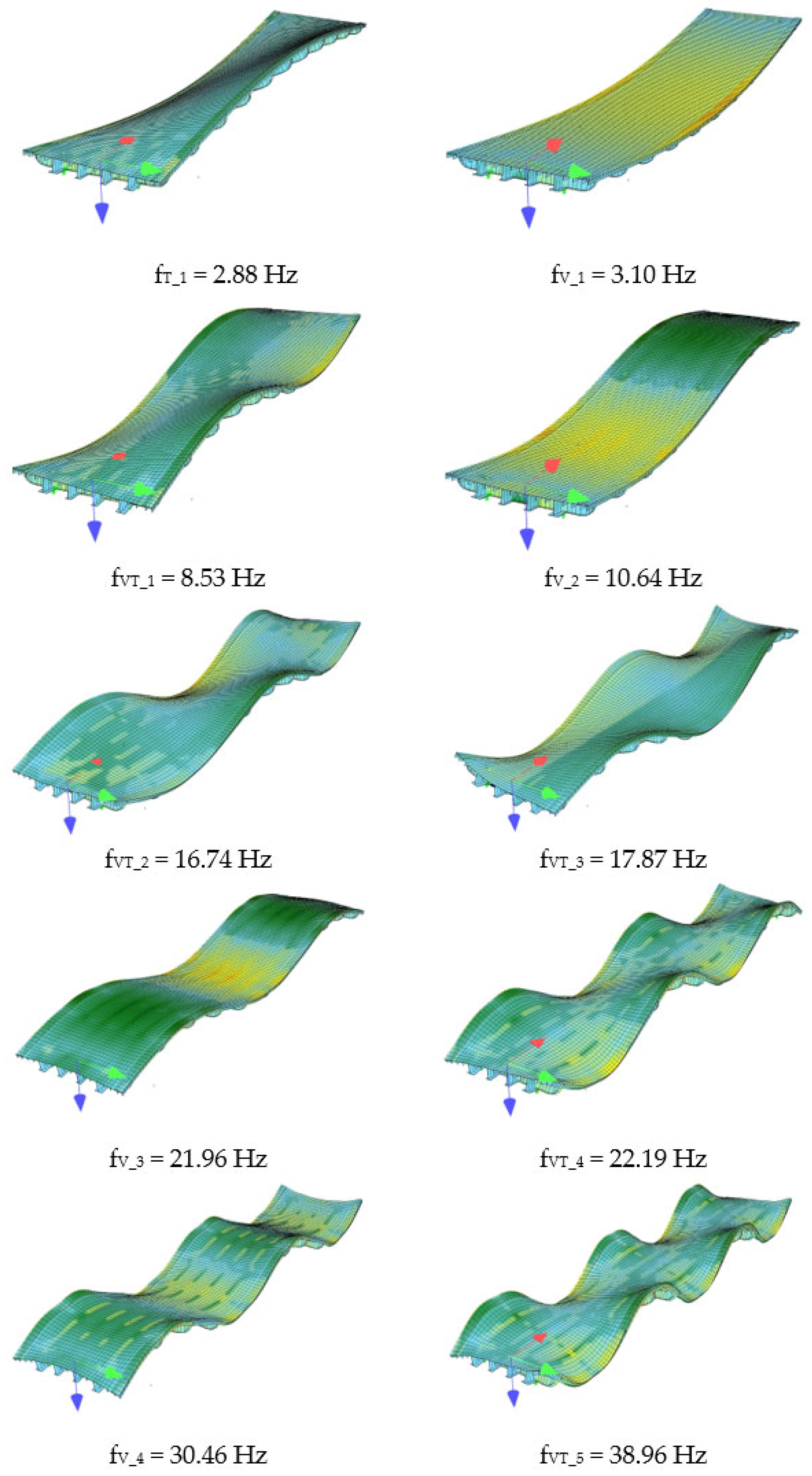

2.6. The Finite Element Model of the Footbridge and the Numerical Analysis

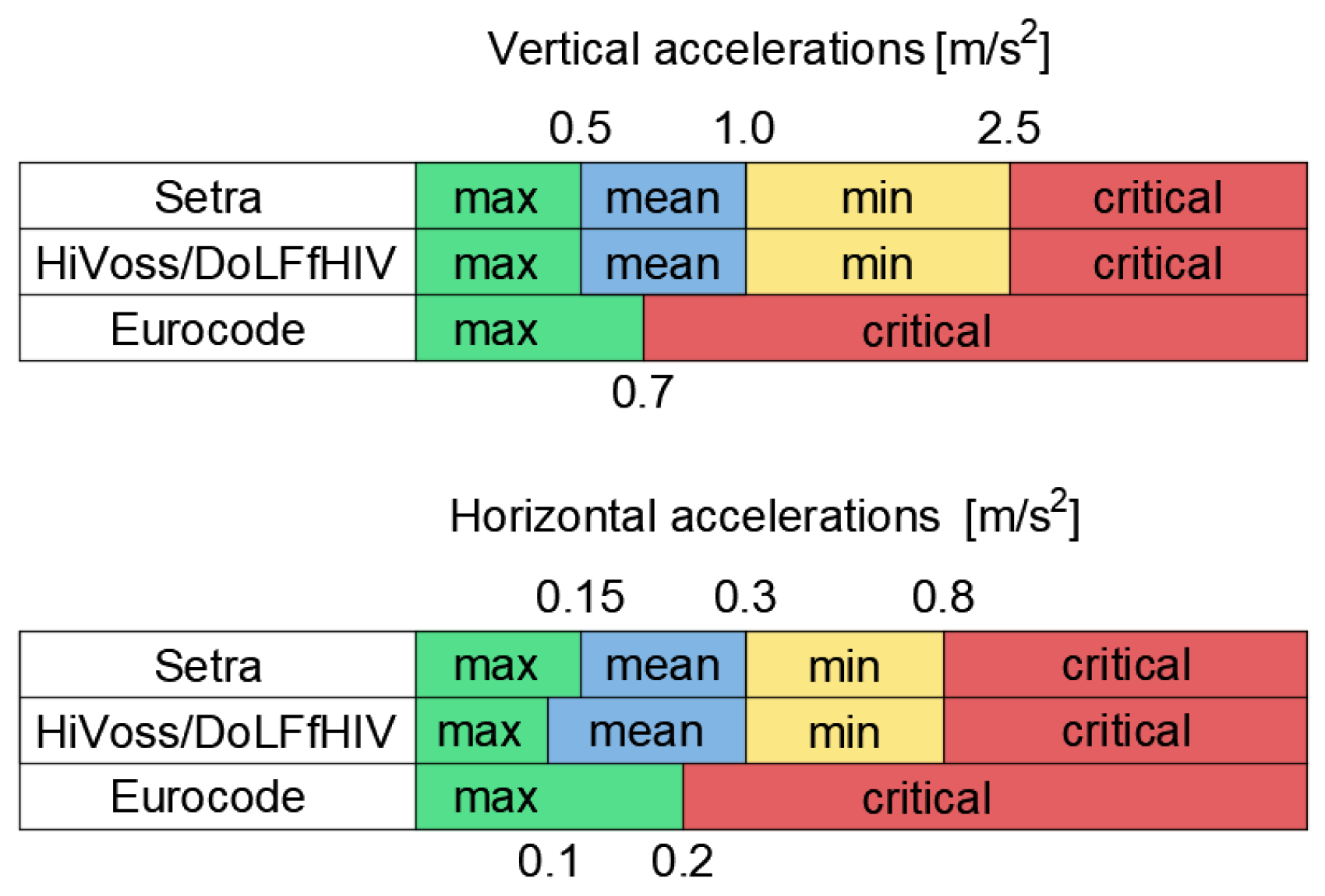

2.7. Vibration Serviceability of Footbridges According to the Current Codes

3. Results

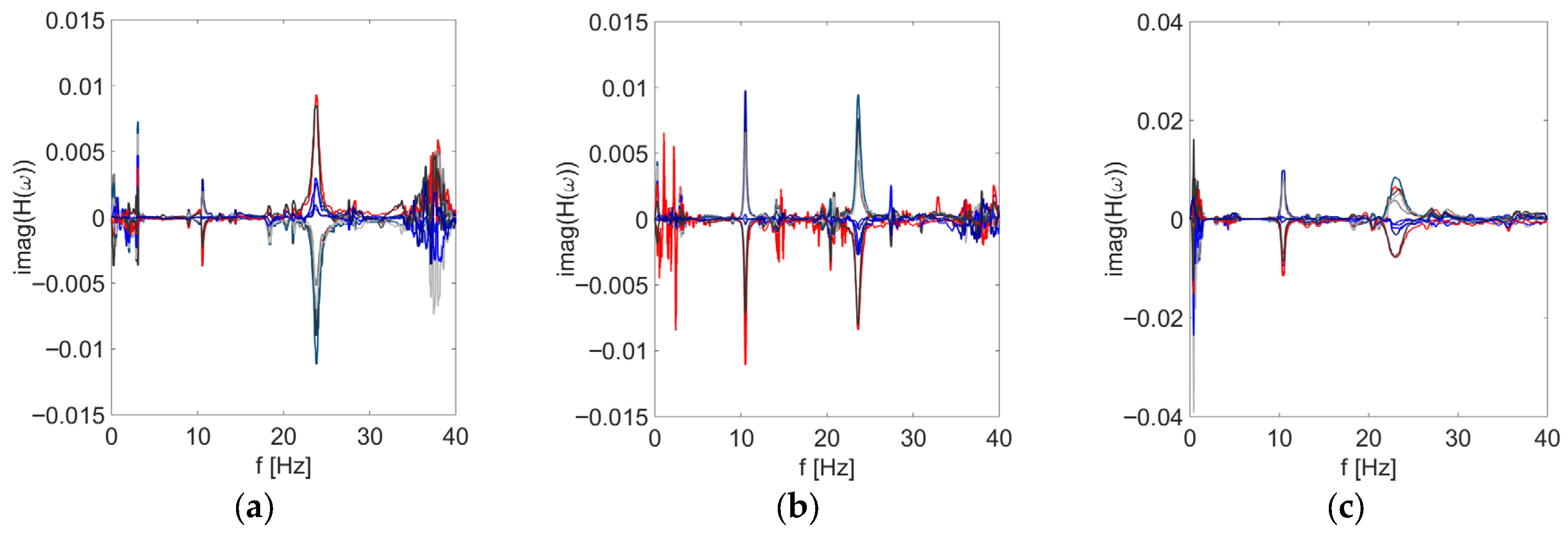

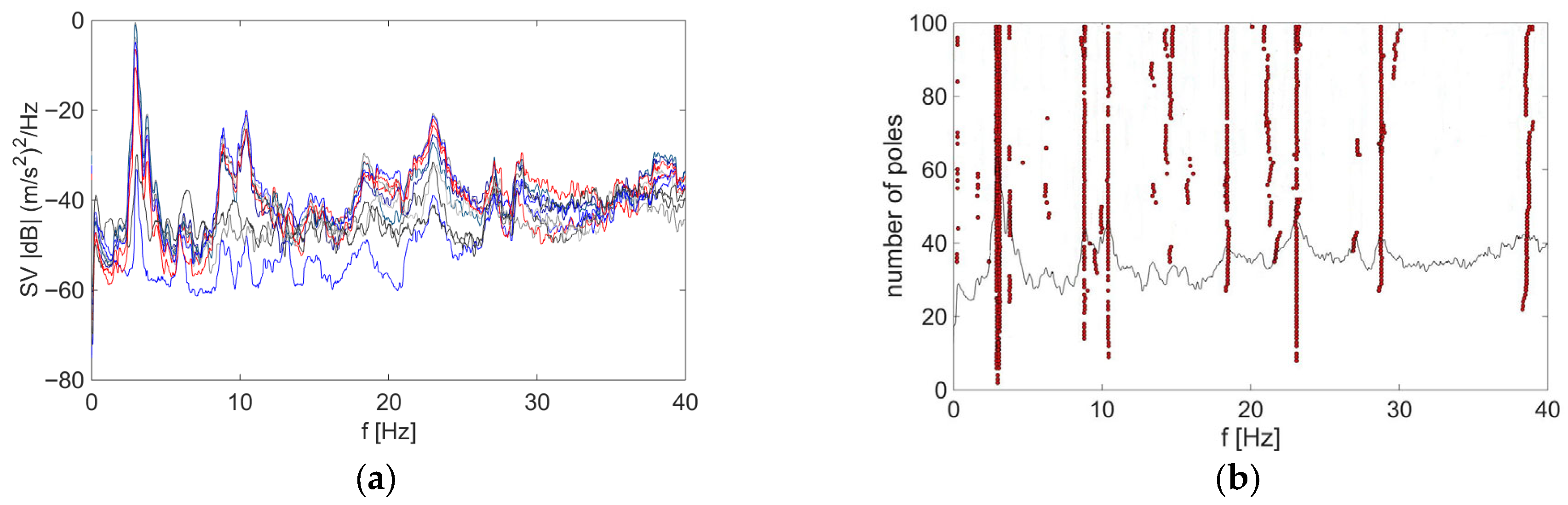

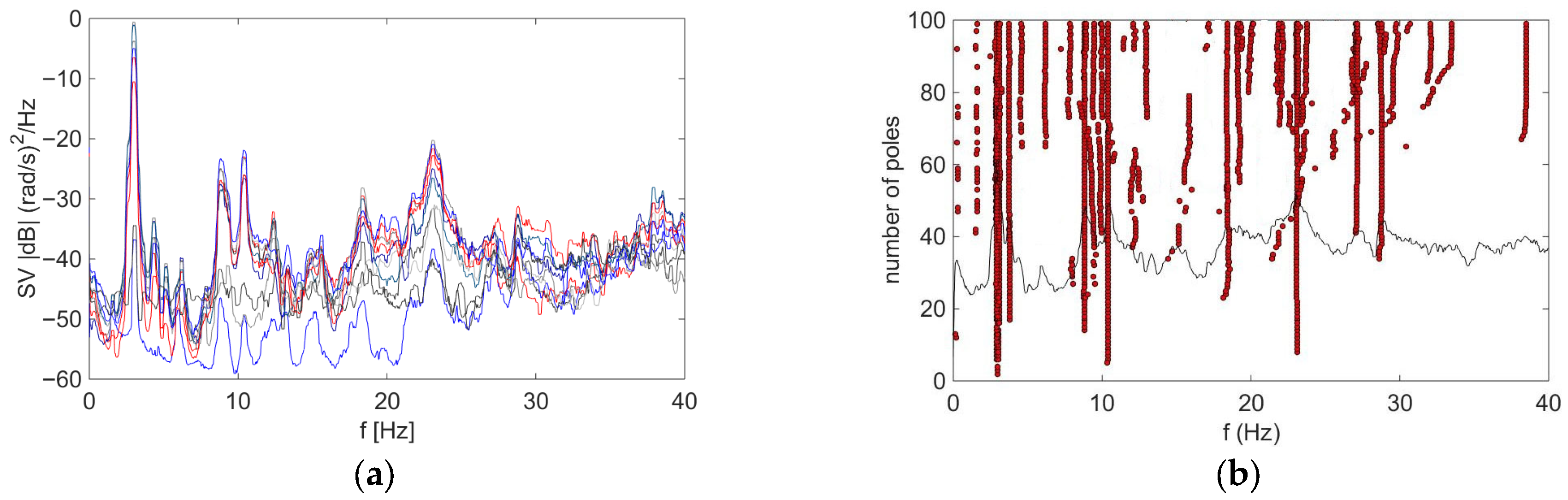

3.1. The Experimental and Numerical Identification Results

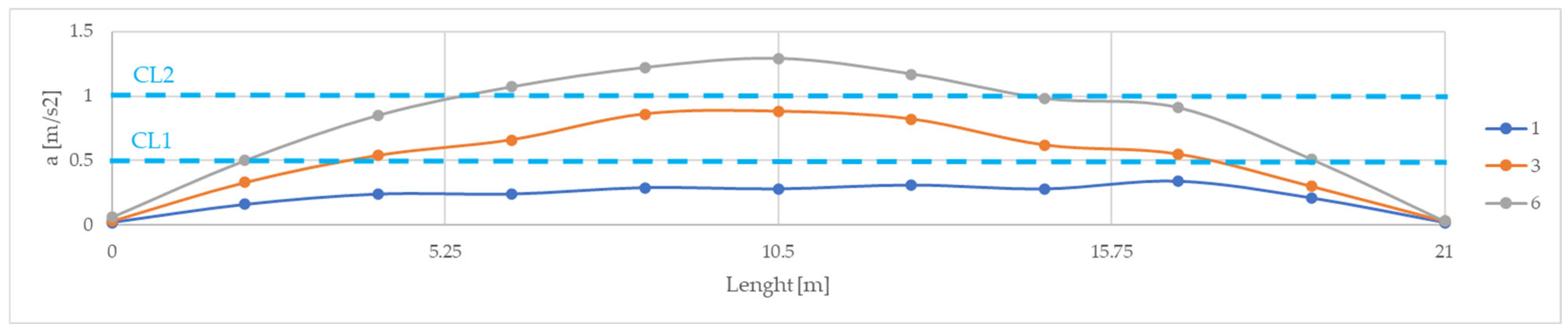

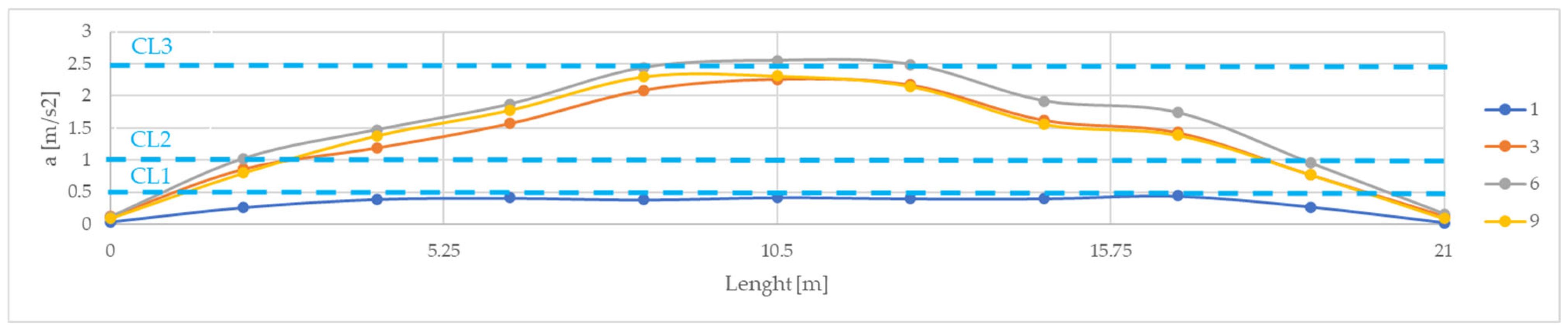

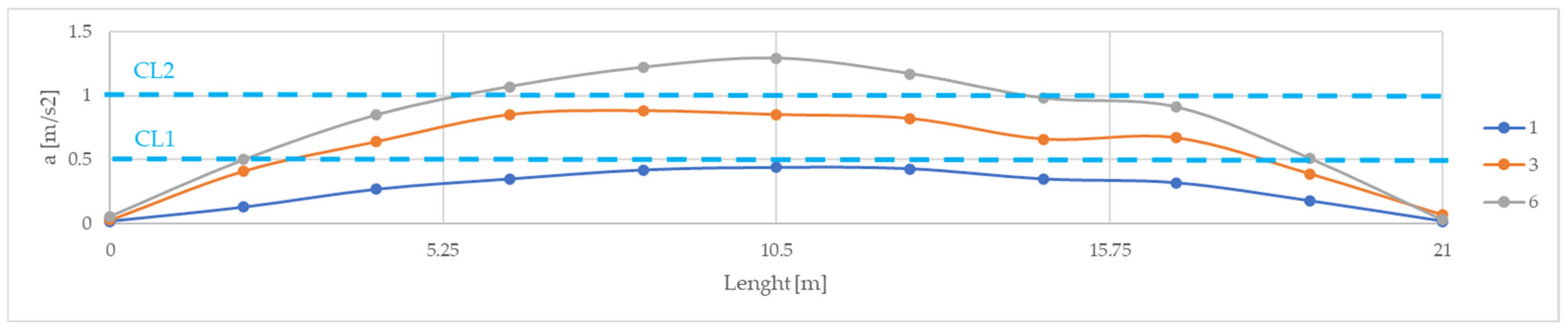

3.2. Assessment of Pedestrian Effects

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison Between Experimental and Numerical Identification Results

- (i)

- the unloaded model, representing the structure without additional external mass, and

- (ii)

- the loaded model, in which the mass of the large modal exciter was included at locations CS6 and CS8.

4.2. Assessment of Pedestrian Comfort Criteria

5. Conclusions

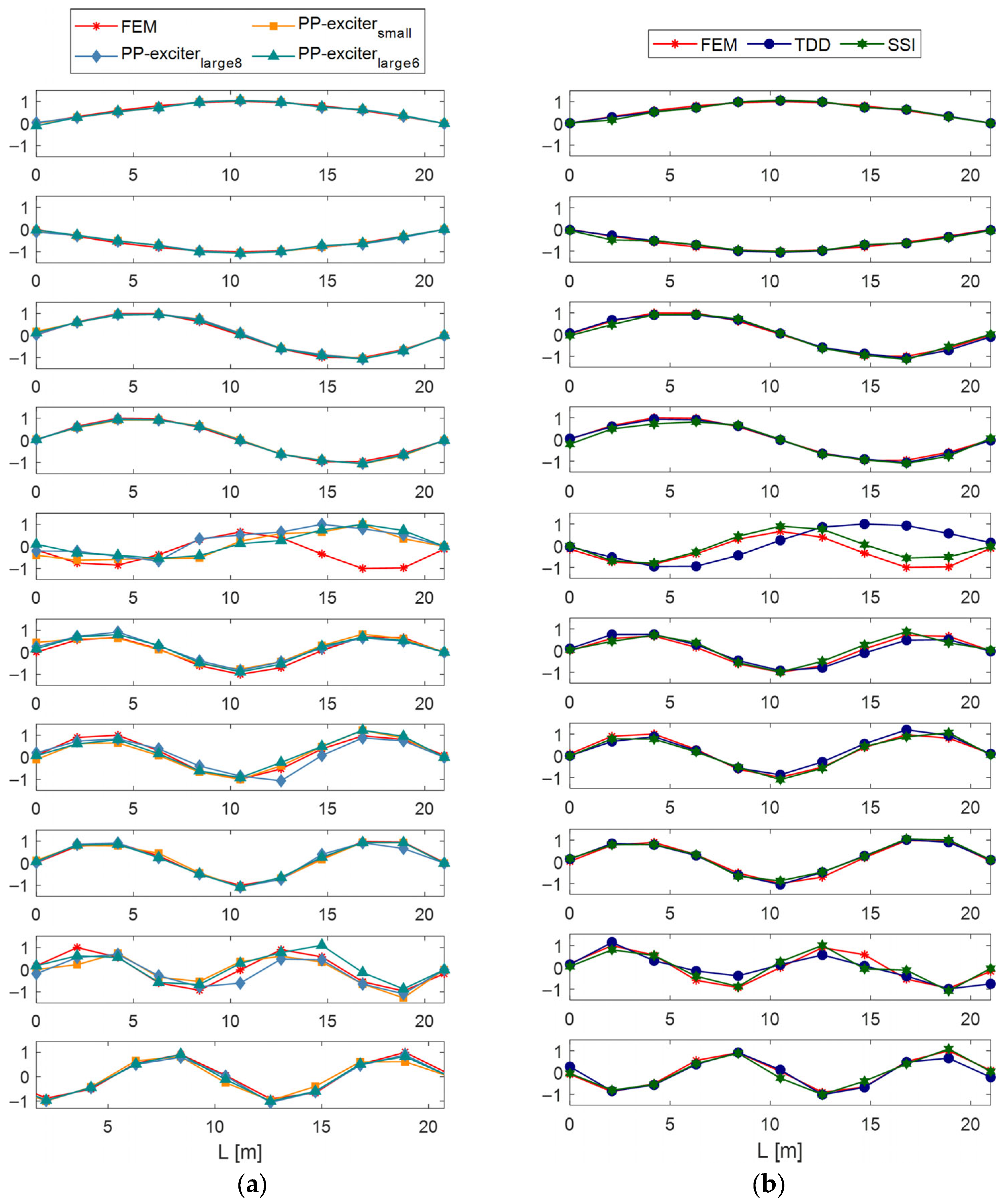

- Combining rotational velocities with acceleration measurements improved modal identification, particularly for coupled vertical–torsional modes. Rotational responses enabled clear recognition of mode VT2, which remained partly obscured when using accelerations alone.

- The applied identification methods—Peak Picking (PP), Frequency Domain Decomposition (FDD) and Stochastic Subspace Identification (SSI)—provided consistent modal parameters for translational DoF with high correlation to the FEM model. FDD and SSI gave the most accurate estimates for rotational DoF, while PP performed well under strong excitation but was less reliable for light excitation.

- MEMS-based gyroscopic sensors proved to be an effective and low-cost complement to acceleration-based monitoring.

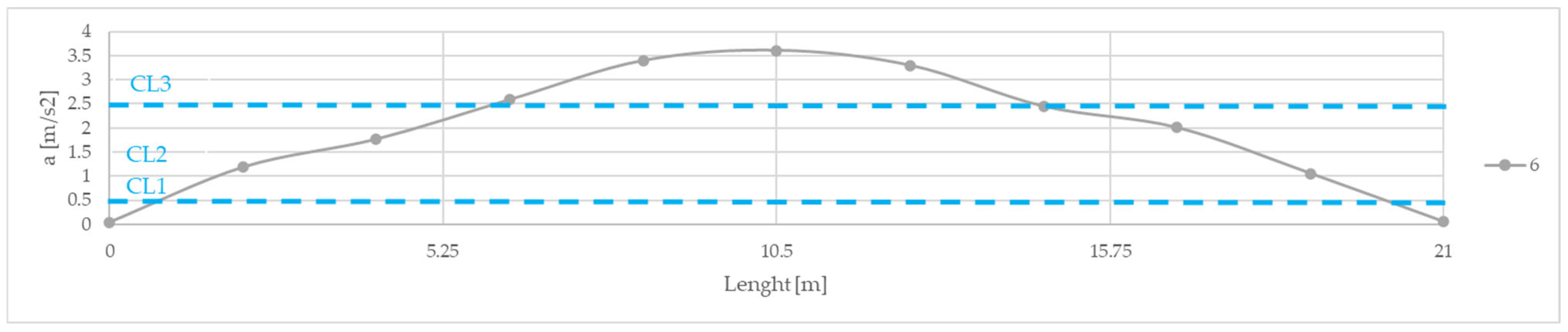

- The serviceability assessment confirmed the resonance-prone behaviour of the footbridge: its fundamental vertical frequency of 3.1 Hz falls within the critical pedestrian excitation range. Dynamic tests recorded peak accelerations up to 3.6 m/s2 during tests with pedestrians; while these levels do not threaten structural integrity, they may cause perceptible discomfort, especially for groups of users. The observed vibrations indicate the need for mitigation measures such as tuned mass dampers.

- Future research should advance rotational sensing within multi-scale SHM frameworks and improve hybrid identification procedures to enhance the accuracy and predictive capability of numerical models for pedestrian bridges.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CFA | Continuous Flight Auger |

| CS6 | Cross-section 6 |

| CS8 | Cross-section 8 |

| DoF | Degree of Freedom |

| FDD | Frequency Domain Decomposition |

| FRF | Frequency Response Functions |

| MARE | Mean Absolute Relative Error |

| MEMS | Micro-Electro-Mechanical-Systems |

| OMA | Operational Modal Analysis |

| PP | Peak Picking |

| PSD | Power Spectral Density |

| RD | Relative Difference |

| SSI | Stochastic Subspace Identification |

| SVD | Singular Value Decomposition |

References

- Živanović, S.; Pavic, A.; Reynolds, P. Vibration Serviceability of Footbridges under Human-Induced Excitation: A Literature Review. J. Sound Vib. 2005, 279, 1–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallard, P.; Fitzpatrick, T.; Flint, A.; Low, A.; Smith, R.R.; Willford, M.; Roche, M. London Millennium Bridge: Pedestrian-Induced Lateral Vibration. J. Bridge Eng. 2001, 6, 412–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caetano, E.; Cunha, Á.; Magalhães, F.; Moutinho, C. Studies for Controlling Human-Induced Vibration of the Pedro e Inês Footbridge, Portugal. Part 1: Assessment of Dynamic Behaviour. Eng. Struct. 2010, 32, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, C.; Gallino, N. Ambient Vibration Testing and Structural Evaluation of an Historic Suspension Footbridge. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2008, 39, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, E.; Gentile, C.; Mulas, M.G. Experimental and Numerical Serviceability Assessment of a Steel Suspension Footbridge. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2017, 132, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pańtak, M.; Jarek, B.; Marecik, K. Vibration Damping in Steel Footbridges. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 419, 012029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Li, S. Study on Vertical Vibration Control of Long-Span Steel Footbridge with Tuned Mass Dampers under Pedestrian Excitation. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2019, 154, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Suesca, A.E.; Gutiérrez-Junco, O.J.; Hernández-Montes, E. Vibration Performance Assessment of Deteriorating Footbridges: A Study of Tunja’s Public Footbridges. Eng. Struct. 2022, 256, 113997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayat, E.; Milone, A.; Tubino, F.; Venuti, F. Vibration Serviceability Assessment of a Historic Suspension Footbridge. Buildings 2022, 12, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drygala, I.J.; Dulińska, J.M.; Nisticò, N. Vibration Serviceability of the Aberfeldy Footbridge under Various Human-Induced Loadings. Materials 2023, 16, 2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banas, A.; Nariswari, A.; Mulas, M.G. Modal Properties and Human Induced Vibration of an Arch Footbridge in Gdynia (PL). In Proceedings of the Experimental Vibration Analysis for Civil Engineering Structures, Porto, Portugal, 2–4 July 2025; Cunha, Á., Caetano, E., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 93–104. [Google Scholar]

- Machelski, C.; Barcik, W.; Hawryszków, P.; Tadla, J.; Biliszczuk, J. Wrażliwość podwieszonych kładek dla pieszych na wzbudzenia dynamiczne. Inż. Bud. 2005, 61, 562–569. [Google Scholar]

- Živanović, S.; Pavic, A.; Reynolds, P. Finite Element Modelling and Updating of a Lively Footbridge: The Complete Process. J. Sound Vib. 2007, 301, 126–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Fan, J.; Nie, J.; Li, Q.; Chen, Y. Crowd-Induced Random Vibration of Footbridge and Vibration Control Using Multiple Tuned Mass Dampers. J. Sound Vib. 2010, 329, 4068–4092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawryszków, P. Assessment of Pedestrian Comfort and Safety of Footbridges in Dynamic Conditions: Case Study of a Landmark Arch Footbridge. Build. Sci. 2021, 285, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawryszków, P.; Biliszczuk, J. Vibration Serviceability of Footbridges Made of the Sustainable and Eco Structural Material: Glued-Laminated Wood. Materials 2022, 15, 1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoltowski, K.; Banas, A.; Binczyk, M.; Kalitowski, P. Control of the Bridge Span Vibration with High Coefficient Passive Damper. Theoretical Consideration and Application. Eng. Struct. 2022, 254, 113781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulas, M.G.; Fortis, C.; Lastrico, G. Field-Testing and Serviceability Assessment of a Lively Footbridge. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2024, 2647, 122005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biliszczuk, J.; Hawryszków, P.; Szczepanik, K.; Stempin, P. O działaniach tłumu na kładki dla pieszych. Inż. Bud. 2003, 59, 440–445. [Google Scholar]

- García-Diéguez, M.; Racic, V.; Zapico-Valle, J.L. Complete Statistical Approach to Modelling Variable Pedestrian Forces Induced on Rigid Surfaces. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2021, 159, 107800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawryszków, P.; Pimentel, R.; Silva, R.; Silva, F. Vertical Vibrations of Footbridges Due to Group Loading: Effect of Pedestrian–Structure Interaction. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayat, E.; Tubino, F. Experimental and Numerical Characterization of the Dynamic Behaviour of a Historic Suspension Footbridge. In Proceedings of the Experimental Vibration Analysis for Civil Engineering Structures, Milan, Italy, 30 August–1 September 2023; Wu, Z., Nagayama, T., Dang, J., Astroza, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 137–148. [Google Scholar]

- Nicoletti, V.; Quarchioni, S.; Tentella, L.; Martini, R.; Gara, F. Experimental Tests and Numerical Analyses for the Dynamic Characterization of a Steel and Wooden Cable-Stayed Footbridge. Infrastructures 2023, 8, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Xia, J.; Wang, X.; Wen, K.; Wang, Q.; Liu, Q. Analysis of Human-Induced Vibration Response and TLD Vibration Reduction of High Fundamental Frequency Aluminum Alloy Footbridge. Structures 2024, 70, 107579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubino, F.; Van Nimmen, K. Crowd-Induced Loading on Footbridges: Reliability of an Equivalent Spectral Model. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2024, 2647, 122006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziaja, D.; Błazik-Borowa, E. Development of Numerical Models of Degraded Pedestrian Footbridges Based on the Cable-Stayed Footbridge over the Wisłok River in Rzeszów. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 10798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Guo, W.; Zhu, H.; Li, L. Dynamic Test and Finite Element Model Updating of Bridge Structures Based on Ambient Vibration. Front. Archit. Civ. Eng. China 2008, 2, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamak, M.; Łaziński, P. Experimental Identification of the Dynamic Properties of Three Different Footbridge Structures. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference Footbridge, Porto, Portugal, 2–4 July 2008; pp. 319–320. [Google Scholar]

- Tomaszewska, A.; Szafrański, M. Study on Applicability of Two Modal Identification Techniques in Irrelevant Cases. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 2020, 20, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, C.; Avramova, A. Monitoring of Historical Monuments: 5 Years Dynamic Monitoring of the Milan Cathedral. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2024, 64, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szafrański, M. A Dynamic Vehicle-Bridge Model Based on the Modal Identification Results of an Existing EN57 Train and Bridge Spans with Non-Ballasted Tracks. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2021, 146, 107039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoni, A.; Elahi, A.R.; Cimellaro, G.P. A Refined Output-Only Modal Identification Technique for Structural Health Monitoring of Civil Infrastructures. Eng. Struct. 2025, 323, 119210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drygala, I.; Dulińska, J.; Jasińska, D.; Tatara, T.; Małecki, M.; Grabon, S.; Mesar, R. Dynamic Performance Analysis of a Single-Span Footbridge Supported by a Spatially Variable. In Proceedings of the Experimental Vibration Analysis for Civil Engineering Structures, Porto, Portugal, 2–4 July 2025; Volume 2, pp. 436–445. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, D.; Calçada, R.; Delgado, R.; Brehm, M.; Zabel, V. Finite Element Model Updating of a Bowstring-Arch Railway Bridge Based on Experimental Modal Parameters. Eng. Struct. 2012, 40, 413–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, Ø.W.; Øiseth, O. Finite Element Model Updating of a Long Span Suspension Bridge. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Earthquake Engineering and Structural Dynamics, Reykjavík, Iceland, 12–14 June 2017; Rupakhety, R., Olafsson, S., Bessason, B., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 335–344. [Google Scholar]

- Martinelli, L.; Racic, V.; Dal Lago, B.A.; Foti, F. Testing Walking-Induced Vibration of Floors Using Smartphones Recordings. Robotics 2020, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Mao, J.-X.; Xu, Z.-D. Investigation of Dynamic Properties of a Long-Span Cable-Stayed Bridge during Typhoon Events Based on Structural Health Monitoring. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2020, 201, 104172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharry, T.; Guan, H.; Nguyen, A.; Oh, E.; Hoang, N. Latest Advances in Finite Element Modelling and Model Updating of Cable-Stayed Bridges. Infrastructures 2022, 7, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.C.; Salamak, M.; Katunin, A.; Poprawa, G. Finite Element Model Updating of Steel Bridge Structure Using Vibration-Based Structural Health Monitoring System: A Case Study of Railway Steel Arch Bridge in Poland. In Proceedings of the Experimental Vibration Analysis for Civil Engineering Structures, Milan, Italy, 30 August–1 September 2023; Limongelli, M.P., Giordano, P.F., Quqa, S., Gentile, C., Cigada, A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 371–380. [Google Scholar]

- Brambilla, M.; Chiariotti, P.; Cigada, A. On the Effect of Intra- and Inter-Node Sampling Variability on Operational Modal Parameters in a Digital MEMS-Based Accelerometer Sensor Network for SHM: A Preliminary Numerical Investigation. Sensors 2025, 25, 5044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hekič, D.; Kalin, J.; Žnidarič, A.; Češarek, P.; Anžlin, A. Model Updating of Bridges Using Measured Influence Lines. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, B.; Deroeck, G. Reference-Based Stochastic Subspace Identification for Output-Only Modal Analysis. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 1999, 13, 855–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brincker, R.; Zhang, L.; Andersen, P. Modal Identification of Output-Only Systems Using Frequency Domain Decomposition. Smart Mater. Struct. 2001, 10, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.-W.; Omenzetter, P.; Beskhyroun, S. Operational Modal Analysis of an Eleven-Span Concrete Bridge Subjected to Weak Ambient Excitations. Eng. Struct. 2017, 151, 839–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, N.; Yang, Y.B.; Dimitrakopoulos, E.G.; Paraskeva, T.S.; Katafygiotis, L.S. Application of Short-Time Stochastic Subspace Identification to Estimate Bridge Frequencies from a Traversing Vehicle. Eng. Struct. 2021, 230, 111688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhao, S.; Wang, P.; Wang, R.; Huang, M. Improved Data-Driven Stochastic Subspace Identification with Autocorrelation Matrix Modal Order Estimation for Bridge Modal Parameter Extraction Using GB-SAR Data. Buildings 2022, 12, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, T.; Ma, G. Mode Identification Method of Long Span Steel Bridge Based on CEEMDAN and SSI Algorithm. Earthq. Eng. Resil. 2024, 3, 388–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekiya, H.; Kinomoto, T.; Miki, C. Determination Method of Bridge Rotation Angle Response Using MEMS IMU. Sensors 2016, 16, 1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, W.; Hu, W.; Liu, F.; Tang, J.; Li, S.; Yang, Y. Bridge Continuous Deformation Measurement Technology Based on Fiber Optic Gyro. Photonic Sens. 2016, 6, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, S.H.; Park, J.W.; Nagayama, T.; Jung, H.J. A Multi-Scale Sensing and Diagnosis System Combining Accelerometers and Gyroscopes for Bridge Health Monitoring. Smart Mater. Struct. 2013, 23, 015005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.-S.; Agbayani, J.A.; Lee, J.-H.; Lee, J.-J. Rotational Angle Measurement of Bridge Support Using Image Processing Techniques. J. Sens. 2016, 2016, 1923934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, D.W.; Park, H.S.; Choi, S.W.; Kim, Y. A Wireless MEMS-Based Inclinometer Sensor Node for Structural Health Monitoring. Sensors 2013, 13, 16090–16104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BS EN 1337-3:2005; Structural Bearings Elastomeric Bearings. European Committee for Standardization, CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2005. Available online: https://behsazpolrazan.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/EN-1337-3-E-2005-03.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Maia, N.M.M.; Silva, J.M.M. (Eds.) Theoretical and Experimental Modal Analysis; Research Studies Press: Chichester, West Sussex, UK, 1997; ISBN 978-0-471-97067-5. [Google Scholar]

- Ewins, D.J. Modal Testing: Theory, Practice and Application; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-0-86380-218-8. [Google Scholar]

- Rainieri, C.; Fabbrocino, G. Operational Modal Analysis of Civil Engineering Structures: An Introduction and Guide for Applications; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4939-0766-3. [Google Scholar]

- Rossing, T.D.; Fletcher, N.H. Principles of Vibration and Sound; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-1-4419-2343-1. [Google Scholar]

- de Silva, C.W. (Ed.) Vibration and Shock Handbook; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-0-429-12873-8. [Google Scholar]

- Brincker, R.; Zhang, L.; Andersen, P. Modal Identification from Ambient Responses Using Frequency Domain Decomposition. In Proceedings of the 18th International Modal Analysis Conference, IMAC 18, San Antonio, TX, USA, 7–10 February 2000; pp. 625–630. [Google Scholar]

- Brincker, R.; Ventura, C. Introduction to Operational Modal Analysis; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-119-96315-8. [Google Scholar]

- Van Overschee, P.; De Moor, B. Subspace Identification for Linear Systems; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1996; ISBN 978-1-4613-8061-0. [Google Scholar]

- Allemang, R.J.; Brown, D.L. Correlation Coefficient for Modal Vector Analysis. In Proceedings of the 1st International Modal Analysis Conference, Orlando, FL, USA, 1–4 February 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Allemang, R. The Modal Assurance Criterion–Twenty Years of Use and Abuse. Sound Vib. 2003, 37, 14–23. [Google Scholar]

- MathWorks MATLAB R2024a. Available online: https://uk.mathworks.com/products/matlab.html (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- SOFiSTiK, 2025; SOFiSTiK AG: Nuremberg, Germany, 2025. Available online: https://www.sofistik.com/en/ (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- EN 1993-1-1; Eurocode 3: Design of Steel Structures—Part 1-1: General Rules and Rules for Building. European Committee for Standardization, CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2005.

- SÉTRA—Service d’Études Techniques des Routes et Autoroutes. Technical Guide Footbridges—Assessment of Vibrational Behaviour of Footbridges Under Pedestrian Loading; Association Française de Génie Civil: Paris, France, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Directorate-General for Research and Innovation (European Commission); Feldmann, M.; Heinemeyer, C.; Lukić, M. Human-Induced Vibration of Steel Structures (Hivoss); Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2010; ISBN 978-92-79-14146-1. [Google Scholar]

- Heinemeyer, C.; Butz, C.; Keil, A.; Schlaich, M.; Goldbeck, A.; Trometor, S.; Lukic, M.; Chabrolin, B.; Lemaire, A.; Martin, P.-O.; et al. Design of Lightweight Footbridges for Human Induced Vibrations. Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC53442 (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Eurocode 1: Actions on Structures|Eurocodes: Building the Future. Available online: https://eurocodes.jrc.ec.europa.eu/EN-Eurocodes/eurocode-1-actions-structures (accessed on 6 August 2025).

| Guideline | Resonance Risk Level | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Medium | Low | Negligible | |

| Vertical frequencies [Hz] | ||||

| Sétra | 1.7–2.1 | 1.0–1.7; 2.1–2.6 | 2.6–5.0 | 0–1.0; >5 |

| HiVoss/DoLFfHIV | 1.7–2.1 | 1.25–1.7; 2.1–2.3 | 2.3–4.6 | 0–1.25; >4.6 |

| Eurocode | 0.0 -5.0 | – | – | >5 |

| Horizontal frequencies [Hz] | ||||

| Sétra | 0.5–1.1 | 0.3–0.5; 1.1–1.3 | 1.3–2.5 | 0.0–0.3 >2.5 |

| HiVoss/DoLFfHIV | 0.7–1.0 | 0.5–0.7; 1.0–1.2 | – | 0.0–0.5 >1.2 |

| Eurocode | 0.0–2.5 | – | – | >2.5 |

| Mode | Frequency [Hz] | Relative Difference [%] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PP-exsmall | FDD | SSI | FE Model | PP-exsmall | FDD | SSI | |

| T1 | 2.95 | 2.91 | 2.90 | 2.88 | 2.37 | 1.03 | 0.69 |

| V1 | 3.10 | 3.07 | 3.09 | 3.10 | 0.00 | 0.98 | 0.32 |

| VT1 | 8.80 | 8.80 | 8.80 | 8.53 | 3.07 | 3.07 | 3.07 |

| V2 | 10.47 | 10.43 | 10.41 | 10.64 | 1.62 | 2.01 | 2.21 |

| VT2 | 14.60 | 14.80 | 14.80 | 16.74 | 14.66 | 13.11 | 13.11 |

| VT3 | 18.20 | 18.25 | 18.27 | 17.87 | 1.81 | 2.08 | 2.19 |

| V3 | 21.75 | 21.73 | 21.70 | 21.96 | 0.97 | 1.06 | 1.20 |

| VT4 | 23.10 | 23.13 | 23.10 | 22.19 | 3.94 | 4.06 | 3.94 |

| V4 | 32.20 | 28.70 | 28.79 | 30.46 | 5.40 | 6.13 | 5.80 |

| VT5 | 38.45 | 38.55 | 38.59 | 38.96 | 1.33 | 1.06 | 0.96 |

| MARE | 4.42 | 3.46 | 3.35 | ||||

| MEAN V1-V2-V3 | 3.86 | 1.35 | 1.24 | ||||

| Mode | Frequency [Hz] | Relative Difference [%] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PP-exlarge 6 | PP-exlarge 8 | FE Modellarge 6 | FE Modellarge 8 | PP-exlarge 6 | PP-exlarge 8 | |

| T1 | 2.68 | 2.84 | 2.78 | 2.84 | 3.73 | 0.00 |

| V1 | 3.05 | 3.10 | 3.01 | 3.05 | 1.31 | 1.61 |

| VT1 | 8.91 | 8.82 | 8.51 | 8.43 | 4.49 | 4.42 |

| V2 | 10.34 | 10.42 | 10.59 | 10.30 | 2.42 | 1.15 |

| VT2 | 14.30 | 14.40 | 16.46 | 16.58 | 15.10 | 15.14 |

| VT3 | 18.03 | 18.50 | 17.46 | 17.62 | 3.16 | 4.76 |

| V3 | 21.13 | 21.25 | 21.48 | 21.75 | 1.66 | 2.35 |

| VT4 | 22.70 | 22.12 | 21.92 | 21.84 | 3.44 | 1.27 |

| V4 | 31.40 | 30.70 | 30.20 | 30.22 | 3.82 | 1.56 |

| VT5 | 37.80 | 37.70 | 38.79 | 38.82 | 2.62 | 2.97 |

| MARE | 4.18 | 3.52 | ||||

| MEAN V1-V2-V3 | 1.80 | 1.70 | ||||

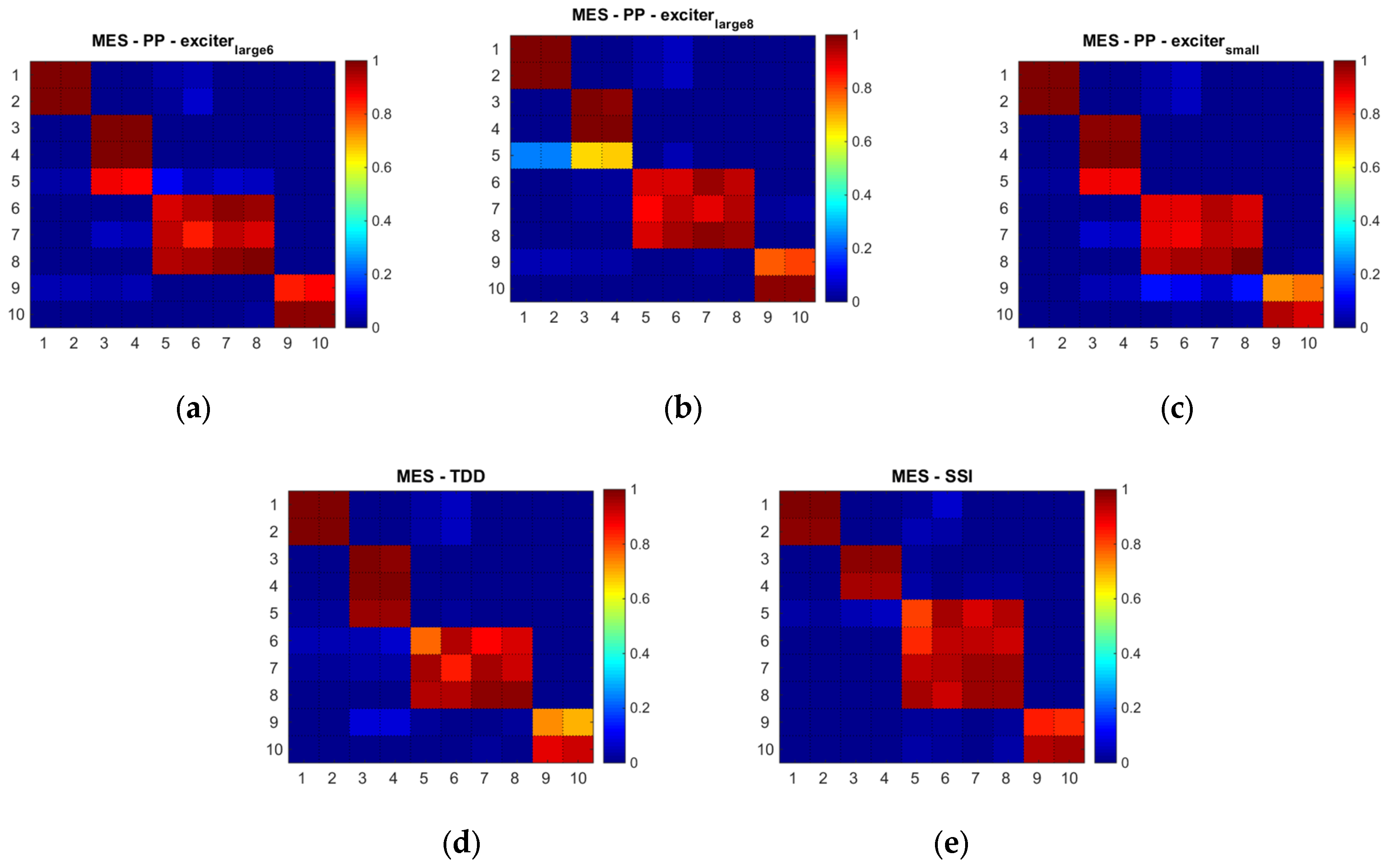

| Mode | MAC | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PP-exlarge6 | Nr. Group | PP-exlarge8 | Nr. Group | PP-exsmall | Nr. Group | FDD | Nr. Group | SSI | Nr. Group | |

| T1 | 0.993 | 1 | 0.995 | 1 | 0.995 | 1 | 0.995 | 1 | 0.989 | 1 |

| V1 | 0.993 | 1 | 0.991 | 1 | 0.994 | 1 | 0.993 | 1 | 0.986 | 1 |

| VT1 | 0.993 | 2 | 0.992 | 2 | 0.987 | 2 | 0.990 | 2 | 0.984 | 2 |

| V2 | 0.997 | 2 | 0.997 | 2 | 0.994 | 2 | 0.995 | 2 | 0.958 | 2 |

| VT2 | 0.879 | 2 | 0.670 | 2 | 0.883 | 2 | 0.971 | 2 | 0.956 | 3 |

| VT3 | 0.981 | 3 | 0.965 | 3 | 0.938 | 3 | 0.943 | 3 | 0.927 | 3 |

| V3 | 0.935 | 3 | 0.948 | 3 | 0.928 | 3 | 0.952 | 3 | 0.972 | 3 |

| VT4 | 0.993 | 3 | 0.979 | 3 | 0.989 | 3 | 0.986 | 3 | 0.973 | 3 |

| V4 | 0.867 | 4 | 0.812 | 4 | 0.755 | 4 | 0.737 | 4 | 0.841 | 4 |

| VT5 | 0.981 | 4 | 0.980 | 4 | 0.939 | 4 | 0.917 | 4 | 0.951 | 4 |

| Meanall | 0.961 | 0.933 | 0.940 | 0.948 | 0.954 | |||||

| MeanV1–V2–V3 | 0.975 | 0.979 | 0.972 | 0.980 | 0.972 | |||||

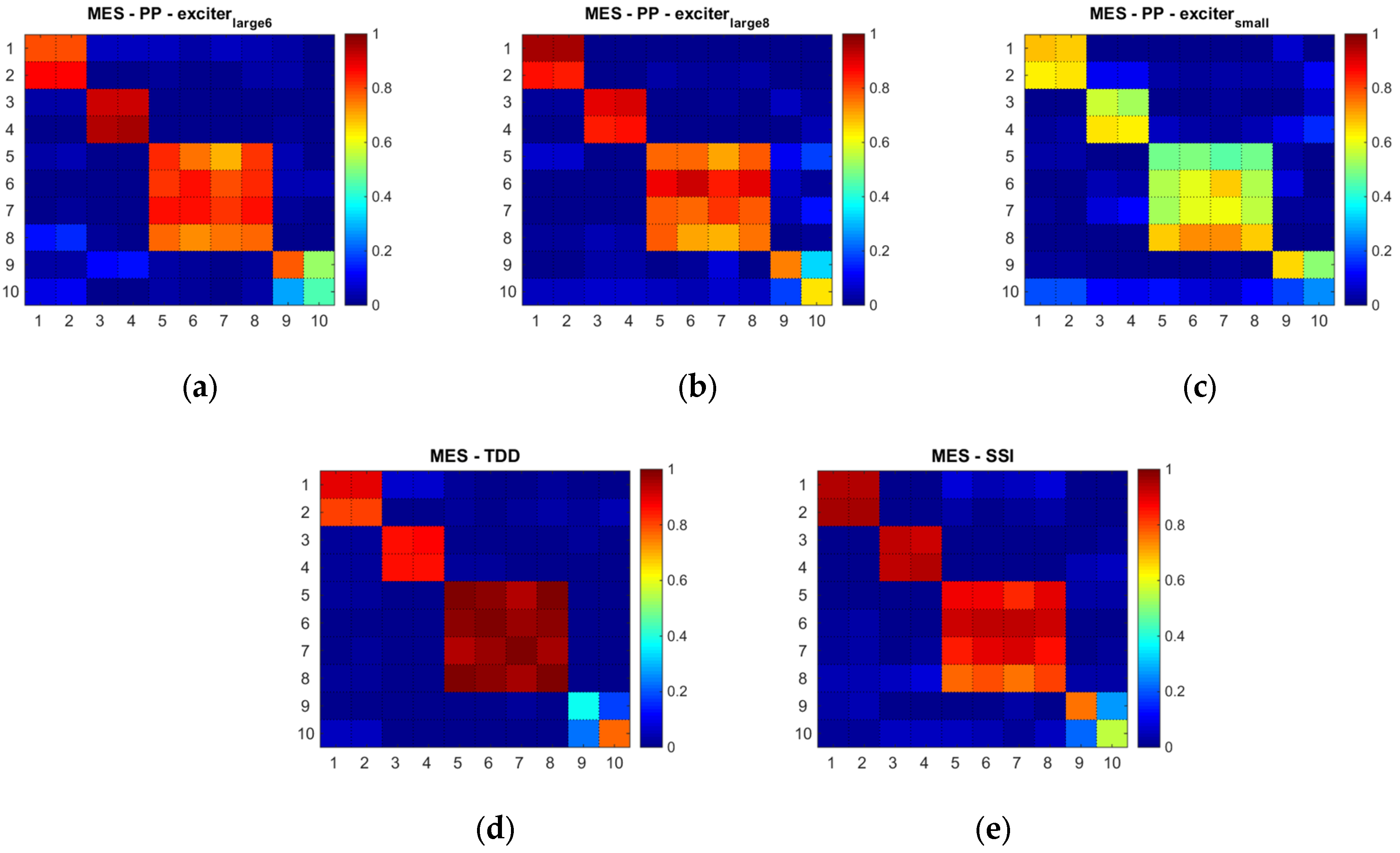

| Mode Order | MAC | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PP-exlarge6 | Nr. Group | PP-exlarge8 | Nr. Group | PP-exsmall | Nr. Group | FDD | Nr. Group | SSI | Nr. Group | |

| T1 | 0.873 | 1 | 0.955 | 1 | 0.676 | 1 | 0.898 | 1 | 0.959 | 1 |

| V1 | 0.875 | 1 | 0.952 | 1 | 0.669 | 1 | 0.893 | 1 | 0.962 | 1 |

| VT1 | 0.947 | 2 | 0.895 | 2 | 0.642 | 2 | 0.860 | 2 | 0.936 | 2 |

| V2 | 0.955 | 2 | 0.911 | 2 | 0.627 | 2 | 0.867 | 2 | 0.946 | 2 |

| VT2 | 0.854 | 3 | 0.885 | 3 | 0.667 | 3 | 0.997 | 3 | 0.917 | 3 |

| VT3 | 0.860 | 3 | 0.918 | 3 | 0.735 | 3 | 0.999 | 3 | 0.925 | 3 |

| V3 | 0.819 | 3 | 0.844 | 3 | 0.736 | 3 | 0.997 | 3 | 0.927 | 3 |

| VT4 | 0.856 | 3 | 0.896 | 3 | 0.673 | 3 | 0.997 | 3 | 0.922 | 3 |

| V4 | 0.784 | 4 | 0.743 | 4 | 0.656 | 4 | 0.386 | 4 | 0.757 | 4 |

| VT5 | 0.524 | 4 | 0.644 | 4 | 0.506 | 4 | 0.764 | 4 | 0.558 | 4 |

| Meanall | 0.835 | 0.864 | 0.659 | 0.886 | 0.881 | |||||

| MeanV1–V2–V3 | 0.883 | 0.902 | 0.677 | 0.919 | 0.945 | |||||

| Sensor | Walk | Run | Jump | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Free | Synchronous | Synchronous | Sync. | ||||||||

| 1 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 6 | |

| Vertical acceleration [m/s2] | |||||||||||

| a1 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.05 |

| a2 | 0.16 | 0.33 | 0.5 | 0.26 | 0.86 | 1.02 | 0.8 | 0.13 | 0.19 | 0.41 | 1.19 |

| a3 | 0.24 | 0.54 | 0.85 | 0.39 | 1.19 | 1.47 | 1.38 | 0.27 | 0.36 | 0.64 | 1.77 |

| a4 | 0.24 | 0.66 | 1.07 | 0.41 | 1.57 | 1.87 | 1.78 | 0.35 | 0.5 | 0.85 | 2.59 |

| a5 | 0.29 | 0.86 | 1.22 | 0.38 | 2.09 | 2.44 | 2.3 | 0.42 | 0.57 | 0.88 | 3.4 |

| a6 | 0.28 | 0.88 | 1.29 | 0.42 | 2.26 | 2.55 | 2.31 | 0.44 | 0.56 | 0.85 | 3.61 |

| a7 | 0.31 | 0.82 | 1.17 | 0.4 | 2.17 | 2.49 | 2.15 | 0.43 | 0.52 | 0.82 | 3.3 |

| a8 | 0.28 | 0.62 | 0.98 | 0.4 | 1.62 | 1.92 | 1.56 | 0.35 | 0.45 | 1.00 | 2.45 |

| a9 | 0.34 | 0.55 | 0.91 | 0.44 | 1.43 | 1.74 | 1.39 | 0.32 | 0.34 | 0.67 | 2.01 |

| a10 | 0.21 | 0.3 | 0.51 | 0.27 | 0.77 | 0.95 | 0.77 | 0.18 | 0.14 | 0.39 | 1.06 |

| a11 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.06 |

| Horizontal acceleration [m/s2] | |||||||||||

| a6y | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Banas, A. Low-Cost Angular-Velocity Measurements for Sustainable Dynamic Identification of Pedestrian Footbridges: A Case Study of the Footbridge in Gdynia (Poland). Sustainability 2025, 17, 10456. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310456

Banas A. Low-Cost Angular-Velocity Measurements for Sustainable Dynamic Identification of Pedestrian Footbridges: A Case Study of the Footbridge in Gdynia (Poland). Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10456. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310456

Chicago/Turabian StyleBanas, Anna. 2025. "Low-Cost Angular-Velocity Measurements for Sustainable Dynamic Identification of Pedestrian Footbridges: A Case Study of the Footbridge in Gdynia (Poland)" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10456. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310456

APA StyleBanas, A. (2025). Low-Cost Angular-Velocity Measurements for Sustainable Dynamic Identification of Pedestrian Footbridges: A Case Study of the Footbridge in Gdynia (Poland). Sustainability, 17(23), 10456. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310456