1. Introduction

Transparency and accountability have become central pillars of contemporary corporate governance, shaping how firms communicate their environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance to stakeholders [

1,

2,

3]. As global markets increasingly prioritize ethical, responsible, and sustainable business conduct, the quality and consistency of ESG disclosure have gained strategic importance. Transparent communication enhances stakeholder trust and reduces information asymmetry, while accountability mechanisms ensure that firms can be evaluated based on reliable and comparable information [

4,

5].

Despite the growing relevance of ESG reporting, the empirical literature highlights substantial variation in how transparency and accountability are implemented across firms, sectors, and institutional environments. Prior studies have examined ESG disclosure through the lenses of legitimacy, stakeholder, and signaling theories [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]; however, many of these investigations remain conceptually oriented or rely on fragmented and con-text-dependent evidence. Moreover, existing research has often emphasized either environmental or financial dimensions of corporate performance, with limited attempts to evaluate ESG disclosure in an integrated and systematic manner [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15].

In emerging markets such as Turkey, the need for rigorous ESG disclosure assessment is particularly pronounced. Firms listed on the Public Disclosure Platform (KAP) operate in a dynamic regulatory environment where investor expectations, institutional pressures, and governance reforms increasingly prioritize transparent communication [

16,

17,

18]. The information technology (IT) sector, in particular, represents a salient context for examining ESG disclosure practices due to its rapid growth, high stakeholder visibility, and potential to lead industry-wide transformations in corporate sustainability communication. Yet, systematic and comparable evidence on ESG disclosure within this sector remains limited [

19,

20,

21].

To address these gaps, this study develops a comprehensive ESG Disclosure Index based on 18 binary indicators capturing the environmental, social, and governance dimensions of corporate transparency. Using a combination of equal-weight aggregation and cluster analysis, the study evaluates disclosure practices of 31 IT firms listed on Borsa Istanbul (BIST). The methodology provides a consistent, interpretable, and statistically coherent framework for assessing firm-level disclosure intensity and identifying underlying patterns in ESG communication [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. This approach avoids the limitations of methods that require continuous data and instead aligns with the dichotomous nature of ESG indicators commonly observed in emerging markets [

13,

27]

This study makes three key contributions to the literature. First, it offers a theoretically grounded measurement framework that translates the abstract concepts of transparency and accountability into quantifiable ESG disclosure indicators [

1,

2,

3,

4,

20]. Second, it provides a methodologically robust and reproducible evaluation tool tailored to binary disclosure data [

22,

26,

28]. Third, it delivers context-specific empirical insights into the ESG communication practices of Turkish IT firms, identifying disclosure patterns that have implications for regulators, investors, and corporate policymakers [

19,

21,

29].

The remainder of the article is structured as follows.

Section 2 presents the literature review and conceptual background.

Section 3 outlines the dataset and the indicator development process.

Section 4 describes the methodological framework, including the construction of the ESG Disclosure Index and the clustering approach.

Section 5 reports the empirical findings, and

Section 6 offers concluding remarks and policy implications.

2. Literature Review

Table 1 summarizes the evolution of research across both conceptual and methodological approaches to transparency and accountability.

The literature on transparency and accountability can be broadly divided into two main strands. The first strand consists of studies that conceptually or systematically investigate the transparency–accountability nexus [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. These works explore distinctions such as proactive versus demand-driven transparency and top–down versus bottom–up accountability, while examining the implications of these mechanisms for trust, legitimacy, and institutional performance.

The second strand involves empirical studies that apply quantitative, MCDM-based, or clustering methods in domains such as open government data, procurement processes, public sector performance evaluation, and information systems [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. These studies demonstrate the potential of data-driven techniques to evaluate transparency-related dimensions; however, they typically do so without explicitly linking the results to accountability mechanisms.

Table 1 summarizes the principal contributions of prior research across both strands, highlighting their objectives, methodological approaches, and key findings. The first group of studies primarily addresses transparency and accountability as conceptual constructs, whereas the second group employs empirical and methodological approaches. Despite these developments, the literature reveals a clear gap: few studies integrate conceptual and empirical approaches to systematically assess transparency and accountability using a unified analytical framework.

In particular, the lack of empirical investigations that combine objective weighting methods with pattern-recognition techniques limits our understanding of how transparency and accountability interact across different institutional contexts. Furthermore, most existing research examines these constructs either within environmental or financial dimensions of corporate governance, with limited attempts to systematically evaluate disclosure practices in an integrated manner.

This study contributes to filling this gap by developing a two-stage analytical approach. First, it proposes a hybrid methodology that integrates clustering and MCDM techniques to provide a statistically grounded assessment of disclosure practices. Second, it designs a comprehensive indicator set capturing both conceptual and applied dimensions of transparency and accountability. Third, it translates the empirical results into insights relevant for policymakers, regulators, investors, and firms by identifying converging patterns in ESG communication.

3. Theoretical Framework: Transparency, Accountability, and ESG Disclosure

Transparency and accountability have consistently served as fundamental concepts in governance and disclosure studies; however, their practical application in Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) reporting necessitates a robust theoretical foundation. Three interrelated theories—legitimacy theory, stakeholder theory, and signaling theory—offer valuable insights into the motivations and mechanisms underlying firms’ disclosure of ESG information, aiming to strengthen accountability and foster trust among stakeholders.

Legitimacy theory argues that organizations strive to align their actions with prevailing social norms and expectations in order to preserve their legitimacy within society [

7]. By voluntarily disclosing ESG-related information, firms aim to demonstrate consistency with social and environmental standards, thereby reinforcing their alignment with societal values. In this sense, transparent reporting functions as both a symbolic and substantive tool through which firms sustain public and investor approval.

Stakeholder theory, on the other hand, contends that companies bear accountability not only toward their shareholders but also to a broader network of stakeholders—including employees, customers, suppliers, regulatory bodies, and local communities [

8]. Within this framework, transparency serves as a vital mechanism for satisfying stakeholders’ informational needs and signaling responsiveness to their expectations. In the context of ESG disclosure, the quality and comprehensiveness of information provided indicate how effectively firms manage diverse stakeholder interests and navigate potential trade-offs among them.

These three theories were selected because they directly explain how firms communicate sustainability-related information to external audiences and how such communication supports transparency and accountability. Although alternative perspectives such as agency theory or institutional theory were reviewed, they were not adopted because they focus on managerial incentives or macro-level institutional pressures rather than disclosure-driven mechanisms central to ESG reporting.

Signaling theory explains voluntary ESG disclosure as a mechanism through which firms communicate their underlying quality or credibility to the market [

9,

10]. High-quality and detailed ESG reporting signals superior management capability, long-term orientation, and commitment to sustainable practices. Conversely, limited or vague disclosure may indicate either information asymmetry or poor performance. Hence, disclosure acts as a differentiating signal in competitive capital markets.

These theoretical perspectives directly inform the operationalization of the seven ESG disclosure indicators used in this study. Each indicator (C1–C7) captures a specific aspect of transparency and accountability as derived from legitimacy, stakeholder, and signaling theories. This theoretical anchoring ensures that the empirical assessment is not merely descriptive but reflects well-established normative expectations regarding credible, comparable, and stakeholder-oriented disclosure practices.

In addition to providing conceptual grounding, these theories also offer practical guidance for translating transparency and accountability into measurable disclosure indicators. Each theoretical lens clarifies why certain ESG-related actions, behaviors, or reporting practices meaningfully reflect a firm’s commitment to openness and responsibility toward stakeholders. By systematically aligning the study’s seven ESG indicators (C1–C7) with legitimacy, stakeholder, and signaling theory, the research ensures that the empirical framework is not only methodologically rigorous but also theoretically coherent. This alignment strengthens the interpretability of the results and demonstrates that the selected indicators are conceptually justified rather than arbitrarily chosen.

Together, these theories provide the conceptual foundation linking transparency and accountability to measurable ESG indicators. In this study, each of the seven criteria (C1–C7) corresponds to specific theoretical dimensions:

To convert the theoretical link between transparency, accountability, and ESG disclosure into quantifiable terms, seven indicators (C1–C7) were identified, each representing a distinct aspect of the discussed theoretical constructs.

Table 2 outlines how these ESG indicators are connected to the three theoretical foundations—legitimacy theory, stakeholder theory, and signaling theory—demonstrating how each criterion reflects a specific facet of transparency and accountability in corporate reporting. This alignment grounds the empirical analysis in solid theoretical principles and ensures consistency with prominent sustainability reporting frameworks such as GRI, ISSB, and SASB. By doing so, it effectively bridges the gap between abstract concepts of accountability and measurable indicators that can be evaluated using MCDM and clustering techniques employed in this study. The explicit linkage of each criterion to its theoretical foundation enhances both the conceptual depth and methodological robustness of the research.

As shown in

Table 2, the indicators reflect the theoretical foundations of legitimacy, stakeholder, and signaling theories. These links ensure that the ESG disclosure items used in the study are conceptually grounded and consistent with established sustainability reporting frameworks.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data Source and Scope

This study focuses on the transparency- and accountability-oriented dimensions of ESG disclosure among information technology (IT) firms listed on Borsa Istanbul (BIST). The dataset comprises 31 IT firms for which complete ESG-related disclosure data were available on the Public Disclosure Platform (KAP). Data were collected between August and September 2025, covering the most recent reporting period (fiscal year 2024).

Seven indicators were defined to capture key aspects of transparency and accountability in ESG communication. The indicator set was developed based on international reporting frameworks (GRI, ISSB, SASB) and previous empirical studies on ESG disclosure. These indicators were grouped under five dimensions, as shown in

Table 3.

As shown in

Table 3, the indicators reflect the theoretical foundations of legitimacy, stakeholder, and signaling theories. These links ensure that the ESG disclosure items used in the study are conceptually grounded and consistent with established sustainability reporting frameworks. The criteria related to compliance with international standards (C6) strengthen the connection between theoretical legitimacy and practical accountability, while the social, environmental, and governance indicators (C2, C3, and C7) emphasize stakeholder engagement, community responsiveness, and responsible oversight. This theoretical alignment provides a robust foundation for the subsequent methodological analysis presented in

Section 4.2.

4.2. Research Design and Methodological Framework

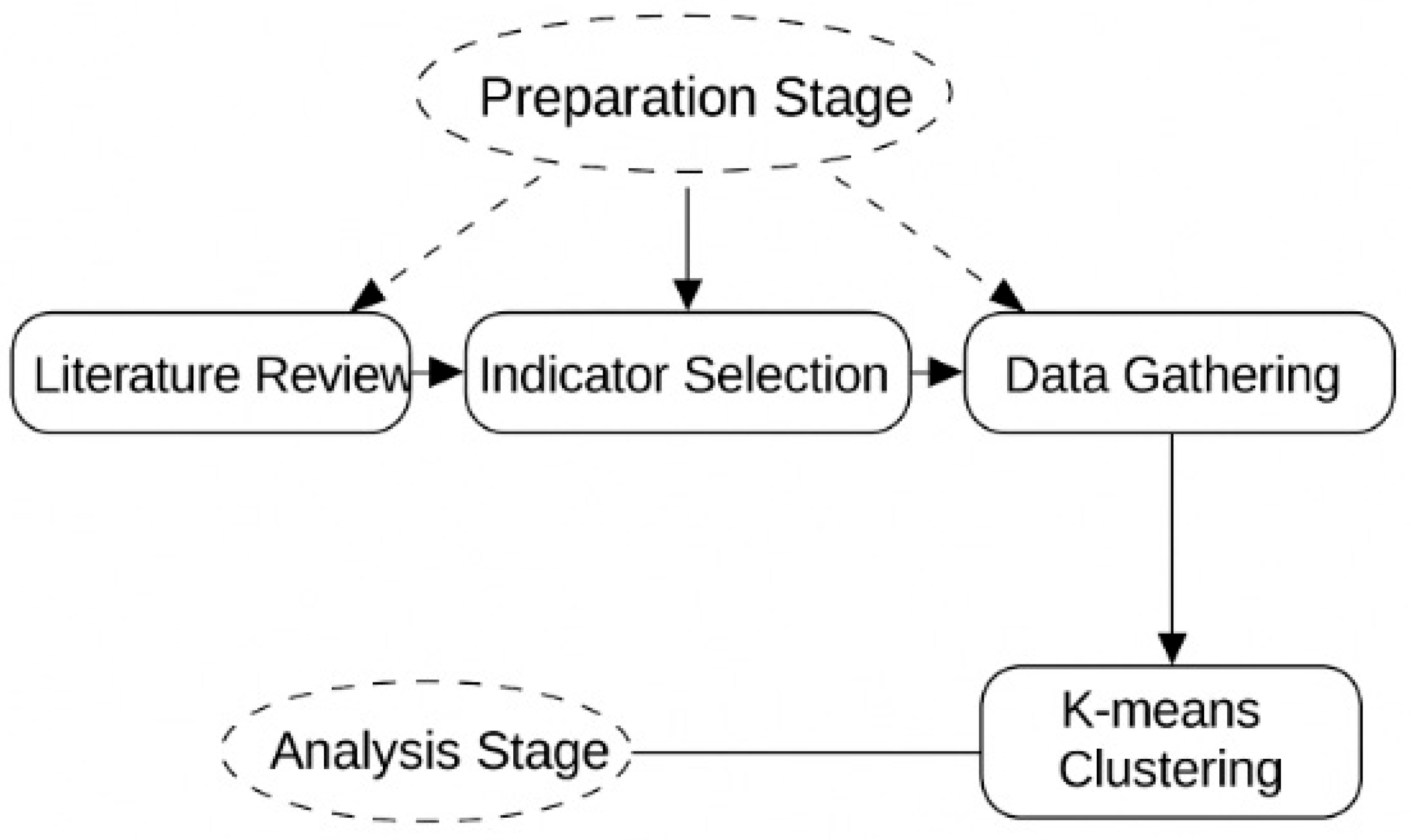

As illustrated in

Figure 1, the research methodology consists of two sequential phases: the preparation stage and the analysis stage.

The preparation stage involves conducting a literature review, identifying relevant ESG disclosure indicators, and gathering the necessary data from publicly available sources.

The analysis stage includes constructing the ESG Disclosure Index, calculating the sub-indices (E, S, G), performing the clustering analysis, and generating the final ESG disclosure scores for each firm.

4.2.1. Construction of the ESG Disclosure Index

The construction of the ESG Disclosure Index follows widely adopted practices in sustainability reporting research [

33,

34].

Because the dataset consists of binary indicators indicating whether each disclosure item is present (1) or absent (0), this approach aligns with methodologies used in prior ESG disclosure studies that operationalize transparency through dichotomous coding [

35,

36].

Binary indicators were assigned to 18 ESG items, covering the environmental, social, and governance dimensions.

As recommended in methodological studies, all indicators were normalized using a single min–max scaling procedure, which is commonly applied in disclosure-based indices to ensure comparability across firms [

37,

38].

4.2.2. Weighting Procedure

Given the dichotomous nature of the data, the study employs an equal-weighting scheme, which is widely endorsed for ESG disclosure indices using binary variables [

39,

40]. Equal weighting prevents artificial variance introduced by statistical weighting methods such as entropy or CRITIC, which require continuous variation to produce meaningful weights [

41].

This approach is also consistent with global ESG rating methodologies (e.g., GRI and SASB frameworks), which treat disclosure items as conceptually equal unless empirical justification exists for differential weighting [

42,

43].

Under this structure, each indicator contributes equally to its respective dimension, and the final ESG Disclosure Index is computed as the arithmetic mean of all normalized indicators.

4.2.3. ESG Sub-Indices

The environmental (E), social (S), and governance (G) sub-indices follow the structure of prior empirical research segmenting ESG disclosures into three pillar components.

Each sub-index is calculated as the average of its associated normalized disclosure items.

The composite

ESG Disclosure Score is computed using the standard aggregation method also found in multi-dimensional sustainability assessments:

This approach aligns with established frameworks that model ESG performance as the balanced integration of the three principal sustainability pillars [

44].

4.2.4. Cluster Analysis

Cluster analysis has been widely used to examine patterns in ESG behavior and corporate sustainability profiles [

45].

In line with best practices in unsupervised learning, this study validates the optimal number of clusters using both the elbow method [

46] and the silhouette coefficient [

47], two standard validation techniques in clustering research.

Both measures indicate that a two-cluster solution provides the most coherent structure for the dataset.

All clustering procedures rely on min–max normalized ESG scores, consistent with methodological recommendations for reducing scale distortion in multivariate classification [

48].

4.2.5. Consistent Definition of Criterion C7

Criterion C7 was standardized in line with recommendations from sustainability communication literature, which emphasizes consistent definitions in social responsibility disclosure [

6,

49].

The final definition used in this study is:

C7: Activities related to social responsibility projects, awareness events, and trainings have been publicly disclosed.

This definition aligns with prior empirical work assessing social responsibility initiatives within ESG reporting frameworks [

50].

As illustrated in

Figure 1, the research process consists of two main stages: the preparation stage—covering the literature review, indicator selection, and data gathering—and the analysis stage, which includes normalization, equal weighting, construction of the environmental (

E), social (

S), and governance (

G) sub-indices, computation of the composite ESG Disclosure Index, and clustering firms based on disclosure similarity using the K-means algorithm.

4.3. Clustering Analysis Using the K-Means Algorithm

Clustering analysis is employed to identify groups of firms that exhibit comparable ESG disclosure profiles. As an unsupervised learning technique, clustering infers group structure directly from the data without requiring predefined labels, making it particularly suitable for disclosure-based research where transparency levels vary naturally across firms [

24,

25,

26]. This approach also reduces multidimensional complexity by summarizing firms into a limited number of interpretable clusters, thereby facilitating comparative assessment and policy-relevant analysis.

Among available clustering techniques, the K-means algorithm is widely used due to its conceptual simplicity, computational efficiency, and strong performance with continuous, normalized data such as the ESG Disclosure Index. The algorithm partitions the dataset into K clusters by minimizing within-cluster variability through an iterative procedure. Each iteration consists of the following steps:

Initialization: A set of K initial centroids is determined (either randomly or via optimized initialization procedures such as K-means++).

Assignment step: Each firm is assigned to the cluster whose centroid is closest in terms of Euclidean distance.

Update step: Centroids are recalculated as the mean vector of all firms assigned to each cluster.

Objective function computation: The within-cluster sum of squared distances is calculated as the clustering objective. In this study, the objective value D is computed using Equation (1):

where

denotes the ESG disclosure vector of firm

i, and

represents the centroid of cluster

j.

- 5

Convergence check: Iterations continue until cluster assignments stabilize or improvements in D fall below a predefined threshold.

To ensure methodological rigor, the optimal number of clusters was validated using both the elbow method and the silhouette coefficient, two widely adopted diagnostic tools in clustering research. Both measures indicated that a two-cluster solution provides the most coherent structure for the dataset. Standardized min–max values of ESG disclosure indicators were used in all computations to prevent scale-induced distortions in distance-based classification [

24,

25,

26].

Overall, the K-means algorithm offers a transparent, reproducible, and statistically sound framework for grouping firms according to their ESG disclosure intensity, making it well aligned with the objectives of this study.

4.4. Robustness and Validation

To ensure the robustness and internal consistency of the analytical framework, several validation procedures were conducted.

First, the accuracy and reliability of the disclosure data were verified by cross-checking the ESG information obtained from the Public Disclosure Platform (KAP) with the corresponding sustainability reports of the firms, when available. All 31 firms demonstrated consistent reporting structures, ensuring comparability across the seven indicators.

Second, the internal coherence of the indicator set was assessed by examining whether the seven ESG disclosure criteria exhibited consistent patterns across firms. No contradictory or illogical disclosure combinations were observed, confirming that each indicator behaves as expected within the transparency–accountability framework.

Third, the robustness of the min–max normalization procedure was confirmed by testing the sensitivity of the normalized indicator values to small perturbations. Minor adjustments to individual disclosure items did not materially alter the relative positions of firms, indicating that the normalization procedure preserves the underlying data structure and ensures stability for subsequent analysis [

37,

38].

Fourth, the stability of the K-means clustering solution was evaluated by re-running the algorithm using multiple random initializations (random start and k-means++), following the recommendations of Jain (2010) and Hamerly & Drake (2015) [

24,

25]. Across all runs, the two-cluster structure remained consistent, and firm assignments showed minimal variation, demonstrating the reliability of the clustering outcomes.

Fifth, methodological consistency was validated by examining the alignment between the ESG sub-index scores (E, S, and G) and the final cluster memberships. Firms with higher overall disclosure scores consistently appeared in the higher-disclosure cluster, confirming that the clustering structure is conceptually and statistically coherent with the underlying transparency indicators.

Collectively, these validation steps confirm that the analytical framework—comprising standardized ESG indicators, min–max normalization, and K-means clustering—is robust, replicable, and methodologically sound.

5. Results

The empirical results are based on the normalized ESG disclosure indicators and the aggregated scores calculated for each of the 31 IT firms included in the analysis.

Table 4 presents the indicator weights used in the evaluation framework, reflecting the relative importance assigned to each of the seven transparency- and accountability-oriented ESG criteria.

As shown in

Table 4, the weights capture the contribution of each criterion to the overall disclosure assessment. Notably, C7 (social responsibility initiatives) receives the highest weight, suggesting that externally verifiable social engagement plays a central role in distinguishing disclosure practices among firms. Following the weighting process, all ESG indicators were normalized to ensure cross-firm comparability.

Table 5 reports the resulting standardized scores (Si, Qi, and Pi) for each firm, summarizing their relative disclosure performance across the seven indicators.

As indicated in

Table 5, firms such as Hitit Bilgisayar, Papilon, and Logo demonstrate the strongest disclosure performance, while several companies—including Ingram Micro, Pasifik Teknoloji, and Reeder—display minimal or no ESG-related transparency. These results highlight substantial heterogeneity in disclosure practices across the Turkish IT sector.

To examine patterns within this variation, firms were grouped using the K-means clustering algorithm.

Table 6 presents the distribution of firms across the two resulting clusters.

As shown in

Table 6, the sample divides into two distinct groups:

Cluster 1, containing firms with stronger and more systematic ESG disclosure practices, and

Cluster 2, consisting of firms with limited or fragmented disclosure.

This division reflects meaningful structural differences in reporting maturity, particularly in areas such as environmental certification, human rights policies, and occupational safety transparency. The silhouette coefficient for the clustering solution is 0.61, indicating a satisfactory degree of cohesion within clusters and separation between them.

Table 7 displays the final cluster centers, showing average indicator values for each group.

As seen in

Table 7, firms in Cluster 1 consistently achieve higher average values across all indicators. In particular, notable differentiating factors include:

disclosure of ISO 14001 (C2),

the existence of a Corporate Human Rights and Employee Policy aligned with international conventions (C4),

reporting of workplace accident prevention and safety measures (C5).

These findings indicate that firms in Cluster 1 adopt more transparent, comprehensive, and stakeholder-oriented ESG communication practices compared to those in Cluster 2.

To provide further insight,

Table 8 lists the cluster memberships of all firms together with their distances from the cluster centroids.

As

Table 8 illustrates, firms in Cluster 1 present a wider range of distances (1.239–2.719), indicating greater internal variation among high-disclosure companies. By contrast, the majority of firms in Cluster 2 show closely clustered distance values (around 0.276), reflecting a more homogeneous group with consistently low disclosure levels.

Overall, the results reveal a pronounced divergence in ESG disclosure performance among IT firms listed on Borsa Istanbul. While a subset of companies demonstrates advanced transparency and accountability practices, many others exhibit limited or minimal reporting, underscoring the need for more structured ESG communication and clearer regulatory expectations within the sector.

6. Discussion

This study evaluated the ESG disclosure performance of 31 information technology firms listed on Borsa Istanbul using a standardized ESG Disclosure Index and K-means clustering. The index—constructed through equally weighted and min–max normalized indicators—provides an objective basis for assessing the consistency and depth of firms’ transparency and accountability practices. The findings offer insights into the key disclosure dimensions that differentiate firms within the Turkish IT sector and contribute to the broader ESG reporting and accountability literature.

First, the ESG Disclosure Index results show that indicators closely associated with transparency and accountability—such as ISO 14001 certification, corporate human rights and employee policy disclosure, and reporting on occupational health and safety—play a particularly influential role in distinguishing firms. In contrast, several environmental and social indicators demonstrate more limited variation across the sample. This suggests that, within Turkey’s institutional and regulatory environment, stakeholders place greater emphasis on externally verifiable, standardized, and evidence-based forms of disclosure rather than on broad or generic statements of environmental or social commitment. This pattern aligns with accountability-oriented perspectives emphasizing that credible, comparable information reduces information asymmetry and enhances the usefulness of ESG reporting.

Second, the clustering analysis reveals a clear and meaningful segmentation of disclosure behavior. Cluster 1 comprises firms with consistently high ESG disclosure scores, indicating more mature reporting systems, adoption of international standards, and proactive communication of sustainability-related information. In contrast, Cluster 2 includes firms with fragmented, minimal, or compliance-driven reporting practices. The silhouette coefficient of 0.61 confirms that the two-cluster solution offers a coherent and well-differentiated classification. Collectively, the results indicate substantial heterogeneity in ESG disclosure practices, even within a relatively specialized sector such as information technology.

The contrast between the two clusters also provides insight into firm characteristics associated with disclosure maturity. High-performing firms tend to be larger or more internationally oriented, suggesting stronger exposure to global investor expectations and cross-border normative pressures. Conversely, smaller or domestically focused firms more often appear in the low-disclosure cluster, which may reflect resource constraints, lower external scrutiny, or limited institutional incentives for comprehensive ESG reporting. This dual structure points to a widening divide between leaders and laggards in the Turkish IT sector in terms of transparency and accountability.

From a policy perspective, the findings highlight the importance of further strengthening the regulatory and institutional framework governing ESG disclosure. Harmonizing Public Disclosure Platform reporting templates with internationally recognized standards could enhance comparability across firms. Additionally, encouraging third-party assurance, clarifying expectations regarding disclosure of human rights and workplace safety information, and promoting consistent reporting structures may help firms transition from symbolic compliance toward substantively informative ESG communication. The results suggest that improvements in disclosure quality—rather than only disclosure volume—are likely to yield the most meaningful gains in transparency and accountability.

For corporate decision makers, the empirical patterns demonstrate that integrating ESG considerations into governance and internal control mechanisms can generate reputational and strategic benefits. Firms that provide transparent, verifiable information on environmental certification, employee well-being, and risk-management processes not only achieve higher ESG Disclosure Index scores but also cluster together as a distinct group of high performers. This indicates that sustained investments in data systems, reporting processes, and stakeholder engagement may serve as strategic assets rather than mere compliance obligations.

Finally, the study has several limitations that offer opportunities for future research. The focus on a single sector and country context limits the generalizability of the findings. The analysis is based solely on publicly disclosed information, potentially omitting informal or non-public sustainability practices. Moreover, the cross-sectional research design does not capture potential changes in disclosure behavior over time. Future studies could expand the framework to multi-sector or international settings, incorporate forward-looking metrics such as emissions-reduction targets, or employ longitudinal clustering techniques to examine transitions in disclosure maturity. Despite these limitations, the analytical framework developed here provides a replicable and conceptually grounded approach for evaluating ESG transparency and accountability in emerging markets.

7. Conclusions

This study assessed the ESG disclosure practices of information technology firms listed on Borsa İstanbul by developing a structured evaluation framework built on standardized indicators and a clustering-based analytical approach. The results provide a comprehensive view of how transparently and consistently firms communicate sustainability-related information within the Turkish IT sector.

The findings reveal substantial variation in disclosure practices across the sample. Firms that regularly report on environmental compliance, human rights and employee policies, workplace safety procedures, and stakeholder-oriented activities demonstrate noticeably higher levels of transparency and accountability. These firms form a clearly identifiable group characterized by structured reporting, stronger governance arrangements, and a more proactive approach to sustainability communication.

In contrast, several companies disclose only limited information or provide fragmented statements that do not align with established sustainability frameworks. These firms cluster together as a low-disclosure group, signalling a more symbolic or compliance-driven approach to ESG reporting. The clustering structure shows high internal validity, indicating that firms’ disclosure patterns naturally separate into two groups based on consistency, depth, and substantive content of ESG communication.

Overall, the study makes three key contributions:

It links established concepts of transparency and accountability with measurable disclosure behaviours, demonstrating how firms operationalize these principles in practice. The results highlight which dimensions—such as human rights policies, stakeholder communication, and occupational safety—serve as stronger signals of accountability within an emerging-market context.

It offers a replicable framework for evaluating ESG disclosure using standardized indicators and clustering techniques. This approach allows researchers to identify disclosure patterns without relying on subjective scoring systems, making it suitable for future applications in other sectors or regions.

It provides policymakers, regulators, and corporate managers with evidence on which disclosure dimensions most clearly differentiate transparent firms from others. Strengthening reporting standards, promoting consistent disclosure templates, and encouraging external validation of sustainability information may enhance accountability and comparability across firms.

Despite its contributions, the study has certain limitations. The analysis focuses on a single sector and relies solely on publicly available disclosures, which may not capture all sustainability practices undertaken internally by firms. In addition, the evaluation framework reflects a specific set of indicators and may be further expanded to incorporate additional environmental or forward-looking metrics.

Future research may extend this framework to multi-sector contexts, perform cross-country comparisons, or explore how technological tools—such as digital reporting platforms—affect firms’ transparency behaviours over time. Overall, the findings underscore the growing importance of structured ESG communication and provide a foundation for advancing sustainability governance in emerging markets.