Abstract

Improving the credit system within a market economy is key to advancing sustainable economic development in China. Using panel data from 280 cities between 2009 and 2022, this study combines a quasi-natural experiment of China’s social credit system (SCS) reform pilot program and applies a difference-in-differences (DID) model to analyze the impact of SCS on green economic development. The results indicate the following: First, the SCS significantly contributes to China’s green economic development, and this conclusion remains valid under a variety of robustness tests. Second, the positive impact of the SCS is more pronounced in non-coastal, resource-based, and low-environmental-regulation regions. Third, the SCS drives the development of China’s green economy through three pathways: reducing transaction costs, optimizing the market competition environment, and stimulating green innovation. Accordingly, it is imperative to strengthen the foundational infrastructure of the SCS, implement differentiated governance frameworks, and thereby enhance the sustainable development of China’s green economy.

1. Introduction

In recent years, although China’s economy has grown rapidly, it has also led to serious environmental pressures. The 2024 Environmental Performance Index (EPI) shows that China ranks 156th among 180 economies worldwide, highlighting the prominent shortcomings in ecological environmental protection and sustainable development. To address this challenge, national policies have continuously strengthened the country’s orientation toward green development, and the 2025 Chinese Government Work Report even lists “accelerating the development of green and low-carbon economy” as a key task. Against this backdrop, institutional innovation is regarded as a crucial path to promote green transformation and sustainable development.

New institutional economics points out that institutional effectiveness not only stems from formal institutional arrangements such as laws, regulations, and policies but also profoundly relies on the internalization and implementation of informal institutions such as social credit and public values. As an important part of informal institutions, credit norms have effectively promoted the green transformation of economic entities and facilitated the dynamic coupling between institutions and the modernization process by strengthening group constraints and reshaping behavioral logic. Current academic research mainly focuses on the green effects of formal institutions, such as low-carbon governance [1], government responsibilities [2], green finance [3], and environmental regulations [4], while relatively neglecting the potential role of the construction of the SCS. As a core value of excellent traditional Chinese culture, credit not only serves as a fundamental norm for individual behavior and corporate operation but also profoundly shapes the nation’s capacity for sustainable development. Following Manioudis and Meramveliotakis [5], sustainable development should be understood as a historically embedded and institutionally grounded process, requiring an integrated perspective that combines economic, social, and political dimensions. In this context, China’s SCS reform can be viewed as an institutional innovation that reshapes the market environment and promotes sustainable green transformation.

The Third Plenary Session of the 20th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China explicitly called for improving the long-term mechanism for integrity construction. Indeed, credit not only constitutes a soft environment for the effective functioning of formal institutions but also enhances public participation and improves policy implementation efficiency, thereby promoting the development of the green economy [6]. In recent years, a series of enterprises such as Jinhua Environmental Protection, Meili Paper Industry, and Tianjiayi Chemical have been exposed for environmental impact assessment fraud, revealing the severe restrictive effect of credit deficiency on the development of the green economy. Therefore, examining the impact of China’s SCS on green economic development is of considerable theoretical and practical significance.

2. Literature Review

The green economy seeks to substantially reduce the risks of environmental degradation by fostering a low-carbon economy, improving resource-use efficiency, and promoting social inclusion, while simultaneously enhancing social welfare and equity. Since its inception, the Green Economy Initiative has been recognized as a core strategy and a crucial pathway toward achieving sustainable development, serving as an essential mechanism for transforming economic growth patterns and advancing the coordinated development of ecological protection and social progress [7]. At present, the measurement of green economic development in academic research has been further refined and optimized. Relevant studies have evolved from the early efficiency evaluation methods based on the Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) model to more sophisticated approaches such as the Non-Radial Directional Distance Function (NDDF) [8]. These methodological advancements enable a more accurate assessment of the comprehensive performance of green economic development. The evolution of these measurement techniques not only enhances the scientific rigor of evaluation but also provides a more solid quantitative foundation for exploring the driving mechanisms of green economic growth.

Institutional factors play a fundamental and decisive role in promoting green economic development. A sound institutional framework not only provides a stable policy environment and incentive mechanisms for green transformation but also fosters sustainable growth by regulating market behavior, reducing transaction costs, and guiding resource allocation to support green technological innovation [9]. Given the significant externalities associated with the green economy, examining its development from an institutional perspective has gradually become a central topic in theoretical research. Existing studies primarily focus on formal institutional dimensions, such as foreign direct investment [10], green finance [11], cultural consumption [12], smart city construction [13], resource misallocation [14], digital transformation [15], and industrial policies [16]. However, research exploring the relationship between informal institutions and green economic development remains relatively limited.

The relationship between formal institutions and green economic development is still inconclusive: One strand of research suggests that formal institutional factors may exert a negative effect on green economic development. Specifically, environmental regulations often increase firms’ compliance costs, forcing them to divert financial resources away from technological innovation and other productive investments. This, in turn, may hinder technological progress and reduce profit margins [17]. Moreover, stringent environmental regulations can have an adverse impact on the growth of the green economy. For instance, empirical evidence from U.S. manufacturing firms indicates that environmental regulatory constraints significantly increase production costs and negatively affect productivity improvement [18]. However, more and more studies have pointed out that formal institutional factors constitute a fundamental driving force for green economic development, exerting a positive and far-reaching influence on sustainable growth. First, environmental regulations, as policy instruments that directly intervene in resource utilization and environmental protection within a non-market framework, can stimulate firms’ technological innovation through the dual mechanisms of compliance cost effects and innovation compensation effects, thereby promoting the growth of the green economy [19]. Second, low-carbon pilot city policies have been shown to effectively foster regional green economic development by strengthening the synergistic link between green technological innovation and ecological efficiency improvement [20]. Moreover, the implementation of digital inclusive finance policies has been empirically proven to significantly stimulate green economic growth. This stimulating effect is not only evident within local regions but also exhibits a notable spatial spillover effect. At the same time, digital inclusive finance contributes to optimizing urban-rural consumption structures, promoting the greening of household consumption patterns, and thereby facilitating the high-quality development of the green economy [21].

Although formal institutional factors play a pivotal role in promoting green economic development, informal institutional factors also warrant in-depth exploration, and scholars have increasingly devoted efforts to this area in recent years. For example, Ye et al. [22] argue that Confucian culture can enhance the efficiency of corporate green investment primarily by improving human capital and managerial capabilities. Wang et al. [23] find that both traditional morality and modern responsibility significantly foster corporate green management innovation, with social trust serving as a key mediating factor. Moreover, they demonstrate that the effects of traditional morality and modern responsibility vary across stages of economic development: traditional morality exerts a stronger influence on green innovation during the early stages of economic growth, whereas modern responsibility becomes more prominent as economic development advances. Hu et al. [24] further reveal that corporate ESG practices exert a significant positive effect on regional green economic efficiency, with stronger impacts observed among enterprises located in eastern regions, state-owned firms, and highly polluting industries. Mechanism analysis suggests that ESG practices enhance regional green economic efficiency primarily through the promotion of green technological innovation.

On this basis, scholars have further expanded their research perspective to the societal level, focusing on the role of informal institutions such as social norms, trust, and cooperation in green development. SCS, as a key social capital reflecting social trust and contract compliance, is believed to play a significant role in promoting green innovation and sustainable development [7]. At present, the measurement methods of SCS mainly include questionnaire surveys [25], comprehensive indicator-based indices [26], and dishonesty data crawling [27]. Studies on its economic effects focus on areas such as trade growth [28], financial support [29], and corporate governance [30]. Although some studies extend to green innovation and green finance [31,32], few have deeply explored its connection with green development.

Using data from 280 Chinese cities covering the period 2009–2022, this study leverages the pilot implementation of the SCS as a quasi-natural experiment and applies a DID approach to analyze how the SCS influences China’s green economic development. This study makes three primary contributions to the existing literature. First, it adopts policy shock as a relatively exogenous measurement method, replacing traditional subjective measurement approaches, thereby effectively mitigating potential endogeneity issues. Second, it systematically constructs a theoretical framework for how the development of the social credit system influences green economic development, enriching interdisciplinary research at the intersection of institutional economics and green transition. Third, it empirically identifies and verifies three core mechanism pathways: reduction in transaction costs, optimization of market competition, and incentive for green innovation.

3. Policy Background and Research Hypotheses

3.1. Policy Background

Recent years have seen a rise in illegal and non-compliant behaviors in China, including tax evasion, clandestine pollutant discharges, excessive emissions, and debt defaults. The increasingly prominent issue of deficient social credibility has attracted widespread public attention. According to the Report on the Construction of Integrity in China, direct economic losses incurred by enterprises due to dishonest practices amount to approximately RMB 600 billion annually. Data from the Ministry of Ecology and Environment indicate that in 2024, 55,900 administrative environmental penalty cases were processed nationwide, involving total fines of RMB 4.612 billion. The persistently high incidence of misconduct in the environmental domain reflects an underlying institutional trust deficit within environmental governance. The lack of integrity not only exacerbates resource waste and environmental pollution but also, at a deeper level, undermines the effectiveness of institutional enforcement, emerging as a critical obstacle constraining China’s high-quality development and green transition. Against this backdrop, advancing the construction of an SCS has become a vital aspect of modernizing national governance.

To effectively curb dishonest practices across various sectors and foster a sound credit environment, the Outline of the SCS Construction Plan (2014–2020) was promulgated by the State Council in June 2014. This document called for comprehensively advancing social credit development, particularly emphasizing the need to enhance national capabilities in environmental monitoring, information management, and statistics in key areas such as environmental protection and energy conservation. It also advocated for strengthening the collection and management of environmental credit data, achieving coordination and information sharing in environmental protection efforts, and improving the catalog of publicly available environmental information.

To implement the outline’s requirements, China’s top economic planning body and central bank identified 43 pilot regions for SCS construction in two phases during 2015 and 2016. These included cities such as Shenyang, Hangzhou, Chengdu, Xiamen, Yichang, Beijing, and Shanghai’s Pudong New Area. The designated pilot cities actively developed public credit information platforms, organized initiatives like “Integrity Day” and “Integrity in Business,” established environmental credit evaluation mechanisms, and implemented “red and black list” systems to institutionalize and regularize credit-based supervision in key fields.

In May 2024, the National Development and Reform Commission issued the 2024–2025 Action Plan for the Construction of a Social Credit System, which calls for continued monitoring of urban credit conditions, the improvement of the monitoring indicator system, and the expansion of monitoring coverage.

In March 2025, China’s central authorities released the Opinions on Improving the SCS, which further called for establishing a comprehensive SCS covering all market entities, enhancing mechanisms to reward trustworthiness and penalize dishonesty, and consolidating the institutional foundation for green development and modern governance.

3.2. Research Hypotheses

3.2.1. The Impact of SCS Construction on the Green Economy

The construction of the SCS exerts a direct influence on the development of the green economy. First, by disclosing information such as enterprises’ environmental credit ratings and records of environmental penalties [33], the SCS reduces the cost of environmental risk assessment for financial institutions and guides credit funds to accurately flow into green fields such as low-carbon technology research and development and clean energy projects. For example, enterprises with high credit are more likely to obtain qualifications for issuing green bonds or low-interest loans, directly accelerating the commercialization of green technologies. Second, the credit punishment mechanism includes environmental violations (such as excessive emissions and data fraud) in the blacklist of dishonest behaviors. Through cross-departmental joint punishments such as restricting government procurement and financing credit, enterprises are forced to internalize pollution control as a prerequisite for production decisions and take the initiative to adopt environmental protection equipment or clean technologies to reduce pollution from the source. Finally, the credit information sharing platform reduces the cooperation risks both upstream and downstream of the green industrial chain. For instance, environmental protection material suppliers and manufacturing enterprises can quickly establish trust by checking each other’s credit records, promoting collaborative innovation in the green supply chain. At the same time, enterprises will increase ESG information disclosure to maintain their credit reputation [34], attracting investment from ESG institutions and forming a positive cycle of “credit premium–green investment”. Building on the preceding analysis, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1.

The construction of SCS exerts a significant and positive influence on green economic development.

3.2.2. Mechanism Analysis of How SCS Construction Affects the Green Economy

The Transaction Cost Reduction Effect

The establishment of the SCS constitutes an important driving force behind the development of the green economy, with its core mechanism rooted in the reduction in transaction costs. As a key constraint on economic efficiency, transaction costs mainly stem from three constraints: asset specificity, bounded rationality, and opportunism. In the field of green economy, highly specific assets such as investments in clean technology R&D and environmental protection equipment face high risks of sunk costs due to partner defaults or information asymmetry. Meanwhile, complex scenarios such as environmental benefit assessment and carbon footprint tracking place high demands on enterprises’ cognitive abilities, leading to reduced decision-making efficiency. Furthermore, opportunistic behaviors such as “free-riding” and fraudulent green certification undermine the trust foundation of the market.

The SCS significantly reduces information search and verification costs by establishing a multidimensional information-sharing platform that integrates corporate environmental credit records, carbon emission data, and green certification information [35]. In addition, the hierarchical and classified supervision mechanism provides financing support and market access convenience for creditworthy entities, while imposing joint punishment on untrustworthy entities, thereby curbing opportunistic behaviors. At the technical level, the introduction of smart contracts and blockchain has enhanced the rigidity of contract execution, alleviating the uncertainty in specific asset investments [36]. This institutional innovation not only reconstructs the trust mechanism in green technology cooperation but also, by reducing transaction costs, promotes the diffusion of environmental protection technologies, the integration of green supply chains, and the vitality of the environmental rights trading market, thus advancing the high-quality development of the green economy. Thus, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2.

The construction of the SCS can promote China’s green economic development through reducing transaction costs.

The Market Competition Enhancement Effect

The construction of the SCS effectively stimulates market competition and drives the development of the green economy by optimizing the market credit environment. Through the national credit information sharing platform and dynamic credit file system, information such as enterprises’ operational qualifications and performance capabilities is disclosed transparently. This enables creditors to accurately identify enterprise risks and provide differentiated financing support to enterprises with excellent green performance, alleviating capital constraints and improving capital allocation efficiency, which helps attract more enterprises to enter the market and thereby enhance market competition [37]. In addition, the construction of integrity mechanisms in government affairs, business, and judicial fields has streamlined administrative approval processes, improved government transparency, and reduced the cost of enterprises’ market access. The dynamic supervision of the social credit system has effectively curbed enterprises’ tendency to obtain government resources through non-market means, attracted more high-quality enterprises with strong green technology capabilities and compliant operations, and promoted a sound market structure of fair competition. In the fierce market competition, enterprises increase investment in green technologies and clean production processes, which improves production efficiency and resource utilization, reduces energy consumption and pollution emissions, promotes the reconstruction of green industrial chains and the improvement of ecological efficiency, and ultimately drives the high-quality development of the green economy [38]. In light of the above discussion, this study advances the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3.

The construction of the SCS is expected to promote China’s green economic development by enhancing market competition.

The Green Innovation Incentive Effect

The construction of the SCS has significantly promoted the development of urban green economies by stimulating green innovation. This promoting effect is primarily reflected in two key aspects.

First, social trust helps to mitigate the externality constraints associated with green innovation. Because the social benefits generated by green innovation often exceed the private returns, enterprises typically bear substantial costs and high uncertainty while being unable to fully capture the resulting benefits [39]. This imbalance between costs and returns weakens firms’ incentives to invest in green innovation, thereby hindering innovation activities. In regions with higher levels of social trust, market participants tend to place greater emphasis on contract fulfillment and reputation maintenance, and their behavior is more strongly guided by moral norms. As a result, opportunistic behaviors such as free-riding and intellectual property infringement are significantly reduced. Thus, a high degree of social trust can partially alleviate the externality problem of green innovation, enhance firms’ willingness to engage in environmentally oriented innovation, and ultimately foster the development of urban green economies.

Second, social trust contributes to reducing information asymmetry in the innovation process. Green innovation activities are inherently risky and uncertain, requiring continuous capital investment and external financial support [9]. However, information asymmetry often prevents external investors from accurately assessing a firm’s innovation potential and risk profile, thereby constraining financing for green innovation. In regions characterized by stronger social trust, firms are more likely to ensure transparency and authenticity in information disclosure, leading to a more reliable and efficient information environment. Such a trust-based institutional context enables investors to better understand firms’ operations and innovation activities, thereby mitigating adverse selection in financing, easing funding constraints for green innovation, and further advancing the urban green economy. Accordingly, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4.

The construction of the SCS promotes the development of China’s green economy by incentivizing green innovation.

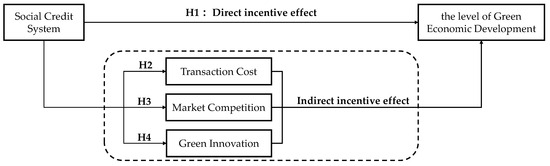

Drawing on the theoretical mechanisms and hypotheses discussed above, the research framework was constructed, as illustrated in Figure 1. Subsequently, empirical analyses were conducted in accordance with this framework.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework.

4. Methodology and Data

4.1. Econometric Model

Drawing on the preceding theoretical discussion and hypotheses, this study develops the following DID model to assess the effect of the SCS on green economic development. Furthermore, to mitigate potential bias resulting from heteroscedasticity, a logarithmic transformation is applied to some variables. The empirical model is specified as follows:

lnGEDit = α0 + α1SCSit + α2lncontrolsit + γi + μt + εit

In Equation (1), subscripts i and t denote the city and year, respectively; lnGED represents the level of green economic development (in logarithmic form); SCS is a dummy variable indicating the implementation of the Social Credit System; lncontrols represents a set of control variables (in logarithmic form), including economic development (lngdp), urbanization (lnurb), infrastructure (lnroa), scientific and technological R&D investment (lntec), and industrial structure (lnind); α0 is the constant term; α1 and α2 represent the estimated coefficients; γi and μt capture city and year fixed effects, respectively; and εit denotes the disturbance term.

To explore in greater depth how the construction of the SCS influences the green economy, this study establishes the following mediation effect model:

lnMit = α0 + α1SCSit + α2lncontrolsit + γi + μt + εit

In Equation (2), M denotes the mediating variables, namely transaction cost (lnTRC), market competition (lnMAC), and green innovation (PAT), respectively; all other variables are consistent with those defined in Model (1).

4.2. Variable Selection

4.2.1. Explained Variable: The Level of Green Economic Development (lnGED)

The green economy encompasses multiple dimensions such as resource efficiency, environmental sustainability, social inclusivity, and low-carbon transition, making it difficult to fully capture its development level using a single indicator. Hence, this study employs a directional distance function-based DEA model (NDDF–DEA) to measure green economic efficiency as a proxy for the level of green economic development. Specifically, labor, capital, and energy are selected as input factors, and real GDP is used as the desirable output, while industrial soot and dust, carbon dioxide (CO2), sulfur dioxide (SO2), and industrial wastewater emissions are treated as undesirable outputs.

4.2.2. Explanatory Variable: Social Credit System (SCS)

Based on the list of pilot cities for SCS construction released by the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) and the People’s Bank of China (PBoC), a value of 1 is assigned to a city in the year it is designated as a pilot city and thereafter, while cities that are not included receive a value of 0.

4.2.3. Mediation Variables

Transaction Cost (lnTRC): A well-functioning credit environment can effectively curb firms’ opportunistic behavior in green production, thereby reducing transaction costs and promoting green economic development. To capture this mechanism, this study uses the ratio of the sum of selling, financial, and administrative expenses to total assets of enterprises in each city as a proxy indicator for regional transaction costs. The relevant data are obtained from the China Industrial Economic Statistical Yearbook and the China City Statistical Yearbook. Since city-level data on these expense items are not directly available, we obtained provincial-level data from the China Industrial Economic Statistical Yearbook and city-level data from the China City Statistical Yearbook. We then estimated city-level values by proportionally allocating provincial data based on each city’s share of total assets within the province. This approach ensures consistency between provincial and city-level data while maintaining the reliability of the transaction cost indicator.

Market Competition (lnMAC): The construction of the SCS has improved the market credit environment, stimulated market competitiveness, and provided crucial institutional support for the development of the green economy. This study uses the annual number of newly registered enterprises in each city as an indicator of market competition intensity. Admittedly, using the number of newly registered enterprises in the environmental protection or green technology sectors would more directly reflect market competition related to the green economy. However, due to data availability constraints and the inability of the Tianyancha database to accurately identify the industry classification of newly registered enterprises, it is currently not feasible to obtain data specifically for green industries. Therefore, this study employs the total number of newly registered enterprises in each city as a proxy variable for market competition, which comprehensively reflects the overall market dynamism and competitive intensity at the city level.

Green Innovation (PAT): The construction of the SCS strengthens regional green innovation through improving credit constraint mechanisms, optimizing resource allocation efficiency, and stimulating the innovative behavior of market entities, thereby significantly promoting the transformation and high-quality development of urban green economies. Accordingly, this study employs the ratio of green invention patent applications to total patent applications in each city as a proxy variable for green innovation, in order to measure the impact of the social credit system on green innovation.

4.2.4. Control Variables

To mitigate potential estimation bias from omitted variables, the study includes the following control variables: (1) Economic development (lngdp), measured as the natural logarithm of real GDP per capita; (2) Urbanization (lnurb) is defined as the natural logarithm of the urban population share in the total population; (3) Infrastructure (lnroa), measured using the natural logarithm of urban per capita road area; (4) Scientific and technological R&D investment (lntec), measured using the natural logarithm of the proportion of science and technology expenditure to regional GDP; (5) Industrial structure (lnind) is defined as the natural logarithm of the ratio between the added value of the tertiary industry and that of the secondary industry.

4.3. Data and Sample

The sample period of this study spans from 2009 to 2022. After excluding cities with substantial missing data, a balanced panel dataset comprising 280 cities was constructed. The data were obtained from multiple sources, including the China Energy Statistical Yearbook, China Environmental Statistical Yearbook, China Industrial Economy Yearbook, China City Statistical Yearbook, Tianyancha, as well as statistical yearbooks and bulletins of prefecture-level cities. Descriptive statistics for all variables are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics.

5. Results

5.1. Baseline Regression Estimation Results—H1 Test

Table 2 reports the regression results on the relationship between the SCS and China’s green economic development, where columns (1)–(5) sequentially add more control variables. As shown in Table 2, even with the gradual inclusion of control variables, the estimated coefficient of the SCS remains positive and highly significant at the 1% level, indicating that the development of the SCS strongly contributes to China’s green economic growth. Thus, Research Hypothesis 1 is supported. This can be attributed to the fact that the SCS, grounded in laws, regulations, and market mechanisms, establishes integrity-based market rules. On the one hand, it alleviates information asymmetry in corporate transactions and management, significantly reduces operational costs, thereby enhancing profitability and strengthening financial reserves, which effectively mitigates corporate financing constraints. This ensures sustained investment in technology R&D and innovation, facilitating scientific outputs and technological upgrading. On the other hand, by imposing credit-based penalties on violations, the SCS raises the cost of dishonesty, reduces the risk of devaluation of innovation outcomes, and stimulates corporate motivation for innovation. Together, these mechanisms enhance production efficiency and output while substantially reducing resource consumption and pollution emissions, thereby advancing China’s green economic development.

Table 2.

Estimated results of baseline regression.

5.2. Heterogeneity Analysis Results

This paper conducts heterogeneity analysis mainly from three aspects: geographical location, resource endowment, and environmental regulation.

First, we categorize the sample into coastal and non-coastal cities, with the corresponding estimation results reported in columns (1) and (2) of Table 3. The coefficient of the SCS for non-coastal cities (0.149) is higher than that for coastal cities (0.089), indicating that the SCS policy exerts a stronger effect on green economic development in non-coastal areas of China. The possible reason is that coastal cities are relatively developed and can give full play to the market mechanism to optimize resource allocation, thus the marginal impact of the SCS construction policy is relatively lower.

Table 3.

Estimation results of heterogeneity analysis.

Second, following the National Sustainable Development Plan for Resource-Based Cities (2013–2020), the sample is categorized into resource-based and non-resource-based cities for group estimation, with the corresponding results reported in columns (3) and (4) of Table 3. The coefficient of the SCS is markedly higher for resource-based cities than for non-resource-based ones, suggesting that the policy exerts a stronger effect on green economic development in resource-based regions. This is because most resource-based cities are dominated by resource-consuming industries such as coal, metallurgy, and coking. Extensive development has caused generally high pollution emissions. The construction of an SCS with punishment for dishonesty (punishment for dishonesty) and incentives for keeping promises (incentives for keeping promises) exerts a strong deterrent effect on enterprises’ environmental violations, which can promote the rapid development of the green economy.

Finally, a comprehensive index was constructed using the entropy method based on two dimensions, including the comprehensive utilization rate of industrial solid waste and the urban domestic sewage treatment rate, to measure the stringency of environmental regulation. The sample was divided into high and low environmental regulation groups according to the mean value of the index. The results of the subgroup regression are presented in columns (5) and (6) of Table 3. The results show that the SCS construction policy only significantly promotes the green economy development of cities with low environmental regulation. This indicates that the construction of the SCS makes up for the deficiency of relatively loose environmental regulation, increases the cost of dishonesty and the benefits of keeping promises, and guides enterprises in the region towards green production.

5.3. Results of Mechanism Analysis: Test of H2, H3, and H4

Table 4 presents the results of the mechanism analysis. As shown in column (1), the estimated coefficient of the SCS variable is −0.023 and remains statistically significant at the 1% level. This suggests that the SCS effectively reduces enterprise transaction costs, restrains opportunistic behaviors to a certain extent, and promotes the integration and diffusion of enterprises’ environmental protection technologies and the vitality of the environmental rights trading market, thereby facilitating the development of the green economy, which verifies Hypothesis 2.

Table 4.

Estimation results of mechanism test.

Meanwhile, the estimated value of the SCS construction variable in column (2) is significant at 0.050, suggesting that the construction of the SCS can promote healthy market competition, attract more high-quality enterprises with strong green technology capabilities and compliant operations, drive the development of green technologies and clean production processes, and improve green economic efficiency, which verifies Hypothesis 3.

In addition, column (3) shows that the estimated value of the SCS construction variable is significantly 0.006, indicating that the SCS can alleviate the externality constraints faced by green innovation and reduce information asymmetry, thereby promoting green economic development and confirming Hypothesis 4.

5.4. Robustness Tests

5.4.1. Test of the Parallel Trend Assumption

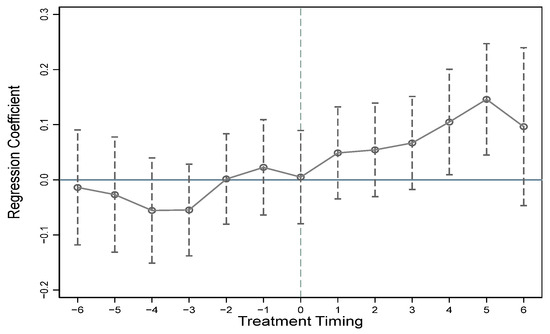

A key condition for applying the DID approach is that the dependent variable should meet the parallel trend assumption between the treatment and control groups. That is, prior to the implementation of the SCS pilot policy, the trajectories of green economic development in pilot and non-pilot cities should evolve similarly. To test whether this assumption holds, the study adopts an event-study framework, taking the initial year of the sample as the reference point, and conducts a parallel trend test. The corresponding results are illustrated in Figure 2. The coefficients estimated for the pre-policy periods are statistically insignificant at the 10% level, implying no significant difference in the development of the green economy between cities with SCS construction and other cities before the policy was implemented, and they maintained a synchronous changing trend. Thus, the parallel trend assumption is confirmed.

Figure 2.

Results of the Parallel Trend Analysis.

5.4.2. Placebo Test

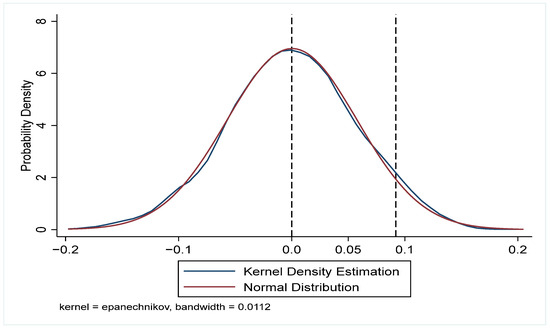

To avoid the issues of underestimated standard errors and excessive rejection of the null hypothesis caused by potential serial correlation in the DID model, this study employs the nonparametric permutation method for a placebo test. The specific steps are as follows. First, randomly select 41 cities from the sample as the fake treatment group, and the remaining 239 cities as the control group. Second, a time point between 2010 and 2021 is randomly chosen as the fake policy implementation time. Third, repeat the above steps 2000 times, and in each iteration, perform regression based on the generated fake treatment group and fake policy time to obtain the estimated coefficient of the interaction term, ultimately obtaining the distribution of 2000 fake coefficients. As shown in Figure 3, the fake coefficients are mainly concentrated around 0 and approximately follow a normal distribution. However, the benchmark estimated coefficient (0.99) of the impact of SCS on China’s green economy development lies in the tail of this distribution, which is a low-probability event. This indicates that the benchmark results have passed the placebo test and the estimation is accurate and reliable.

Figure 3.

Probability density distribution of placebo test.

5.4.3. Propensity Score Matching Test

To mitigate potential estimation bias arising from sample selection, this study employs the Propensity Score Matching Difference-in-Differences (PSM-DID) approach to balance the characteristics of the treatment and control groups and enhance the robustness of the empirical findings. Specifically, the control variables in the benchmark regression are selected as matching covariates. After performing Logit regression using the mixed matching and yearly matching methods of caliper nearest neighbor matching, samples are screened based on propensity scores, and the DID method is re-applied for estimation and testing. As shown in Table 5, the coefficient continues to be positive and significant at or above the 5% threshold, implying that the SCS promotes the development of China’s green economy, and the conclusions of the benchmark regression are verified again.

Table 5.

Estimation results of PSM-DID.

5.4.4. Other Robustness Tests

To ensure the reliability of the estimation results as much as possible, this study conducts a series of robustness checks from the following perspectives:

- (1)

- We exclude prefecture-level cities where the credit system pilot was implemented only at the district or county level, and re-estimate the model. As presented in column (1) of Table 6, the SCS coefficient remains statistically significant at the 1% level with a value of 0.094, which is consistent with the baseline results.

- (2)

- The four direct-controlled municipalities (Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, and Chongqing) have a distinctive administrative status and economic development far exceeding that of other cities. Including them in the sample may unduly influence the estimates. After removing these four cities, we re-run the regression. Evidence from column (2) of Table 6 confirms that the influence of the SCS variable persists, exhibiting a positive sign and statistical significance at the 1% level.

- (3)

- Given the high correlation between electricity consumption and energy usage, we recalculate green economic efficiency using non-radial distance function and data envelopment analysis with electricity consumption data in place of total energy consumption. The estimation results after substituting the dependent variable are reported in column (3) of Table 6. Regression outcomes reported at the 5% significance level reveal that the impact of the SCS variable remains positive, thereby confirming the consistency and reliability of the initial findings.

Table 6.

Results of Additional Robustness Analyses.

Table 6.

Results of Additional Robustness Analyses.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCS | 0.094 *** (4.070) | 0.087 *** (3.678) | 0.032 ** (2.280) |

| Constant | −1.135 *** (−4.523) | −1.049 *** (−4.179) | −0.633 *** (−4.540) |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| City fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 3864 | 3864 | 3920 |

| R2 | 0.732 | 0.732 | 0.730 |

Note: *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, t-statistics are reported in parentheses.

5.5. Endogeneity Analysis

To mitigate potential endogeneity issues arising from omitted variables and reverse causality that may bias the baseline estimates, this paper employs the number of Confucian academies and temples in each city as instrumental variables. The prevalence of these institutions reflects the historical depth of Confucian cultural traditions and the prevailing level of social trust within a city. Confucianism emphasizes integrity, contractual compliance, adherence to social norms, and public morality, which together form the cultural foundation for the development of social credit concepts and institutional arrangements. Accordingly, cities with a stronger Confucian cultural atmosphere, as indicated by a greater number of academies and temples, are more likely to exhibit higher levels of institutional recognition and stronger administrative commitment to the construction of modern social credit systems. This relationship supports the relevance condition required for a valid instrumental variable.

Meanwhile, although the cultural atmosphere may indirectly influence economic behavior, the number of academies and temples itself does not directly determine a city’s s level of green economic development. After controlling for factors such as economic development level, industrial structure, and infrastructure, it is reasonable to assume that this variable affects green economic development only through its impact on social credit system construction, thus satisfying the exclusion restriction condition.

Given that the number of Confucian academies and temples in each city remains relatively stable over time, this paper constructs an interaction term between the implementation dummy variable of the social credit system policy and the sum of academies and temples in each city as the instrumental variable, and estimates the model using the two-stage least squares (2SLS) method. The results are presented in Table 7. As shown in column (1), the coefficient of the instrumental variable is significantly positive at the 1% level, indicating a strong correlation with the endogenous explanatory variable. Moreover, the Kleibergen–Paap rk LM statistic yields a p-value of 0.000, and the Cragg–Donald Wald F-statistic exceeds the critical value of 16.38 at the 10% significance level of the weak identification test, confirming the instrument’s validity. After controlling for endogeneity, the results in column (2) show that the coefficient of the social credit system construction variable remains significantly positive. This finding indicates that the paper’s core conclusions are not substantially affected by potential endogeneity issues, demonstrating the robustness of the results.

Table 7.

Results of the Endogeneity Analysis.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

6.1. Conclusions

As a core value of excellent traditional Chinese culture, credit not only serves as a fundamental norm for individual behavior and corporate operation but also profoundly shapes the nation’s capacity for sustainable development. It plays a unique role in improving market order and promoting green development. Using the SCS pilot cities as a quasi-natural experiment, this study employs a DID model to empirically examine the mechanisms and effects of this policy on China’s green economic development. The findings reveal the following:

- (1)

- The construction of the SCS has significantly promoted green economic development in China, a conclusion that holds under a series of robustness tests. Consistent with existing studies emphasizing the role of institutional quality in fostering green growth, this study further reveals the distinctive role of informal institutional construction as a governance tool in facilitating the green transition;

- (2)

- Mechanism analysis indicates that the credit system facilitates green economic development primarily through three channels: reducing transaction costs, enhancing market competition, and stimulating green innovation. These findings align with the literature on how institutional quality enhances resource allocation efficiency and innovation capacity. However, this study provides city-level empirical evidence on the mechanisms of informal institutions, highlighting the significance of credit constraints and social trust in advancing the green transition;

- (3)

- Findings from the heterogeneity analysis indicate that the policy exerts a greater effect in non-coastal and resource-based cities, as well as in those with less stringent environmental regulations. This suggests that the SCS, as an informal governance mechanism, exerts stronger incentive and coordination effects in areas with relatively weak institutional environments.

Overall, this study not only verifies the positive impact of the SCS on green economic growth but also enriches the theoretical discussion of high-quality green development from the perspective of informal institutions.

6.2. Recommendations

Based on the research findings, this paper proposes the following policy recommendations:

- (1)

- Strengthen the foundation of the credit system and optimize the institutional environment for green transition. As an informal institution embedded in social norms, the SCS provides fundamental support for the green and low-carbon transition through reputation mechanisms and moral constraints. The government should regularly evaluate pilot city performance, summarize replicable governance models, and promote credit culture nationwide. A unified national standard for credit information management should be established, along with a graded framework for environmental credit data. Integrating government, enterprise, and individual credit information will enhance data service efficiency. Development of professional credit service institutions should be encouraged, along with talent training and innovation in credit rating and risk warning products.

- (2)

- Implement differentiated credit construction strategies tailored to the heterogeneous characteristics of cities. Since the impact of the SCS on green economic development varies spatially, differentiated strategies are needed. Non-coastal regions should prioritize data infrastructure improvement and build integrated credit databases. Resource-based cities should strengthen environmental credit indicators and establish credit-constrained mechanisms for resource extraction. Regions with weaker environmental regulation can introduce environmental credit commitment systems, incorporating credit evaluations into environmental supervision.

- (3)

- Remove key blockages in the credit transmission mechanism to smooth the pathway for efficiency improvement. Efforts should focus on three major pathways: establishing credit-backed trading models and developing electronic credit vouchers; linking credit ratings with market access to improve factor allocation efficiency; and implementing incentive mechanisms for green innovation enterprises. Firms with high credit ratings should enjoy policy benefits such as additional R&D tax deductions and priority approval for green projects. A “green innovation whitelist” can guide financial institutions to provide preferential financing.

- (4)

- Strengthen the concept of sustainable development and enhance the green guidance role of informal institutions. Integrate the SDGs into the SCS to build a green credit evaluation mechanism grounded in social recognition. Through credit incentives, guide social capital toward SDGs-aligned fields such as clean energy, green innovation, and energy conservation, thereby forming social constraints conducive to sustainable development. Establish ecological credit accounts that incorporate indicators such as carbon footprints and resource-use efficiency, encouraging all social actors to adopt green, low-carbon, and responsible behaviors that contribute to the realization of the United Nations SDGs.

7. Limitations and Further Research

Although this study provides preliminary evidence on the promoting effect of the SCS on China’s green economic development and its underlying mechanisms, several limitations remain and warrant further exploration. First, regarding the positive impact and heterogeneous characteristics of the SCS pilot reform policy on urban green economic development, this study has not fully accounted for the interactive effects of other related policies (such as intellectual property protection policies and digital technology development policies), as well as factors like the urban geographical environment and environmental regulation, which may lead to certain estimation biases. Second, in terms of key variable measurement, particularly the assessment of green economic development levels using the NDDF model and the parallel trend test, potential measurement errors may exist, thereby affecting the robustness of the conclusions. Finally, the identification of micro-level mechanisms remains insufficient, making it difficult to uncover the specific pathways through which the SCS pilot reform policy influences the green transformation behavior of high-pollution enterprises in cities.

Building upon the above limitations, future research can be extended in several directions. First, micro-level firm data can be introduced, combined with questionnaire surveys or case studies, to better identify the effects of different types of social credit policies (such as environmental credit ratings and financing credit assessments) on the green behaviors of high-pollution enterprises and to examine potential reverse impact mechanisms. Second, future studies can broaden the analysis of the long-term effects of the Social Credit System by employing longer time-series data to trace its dynamic impact on long-term green transformation processes, including green technological innovation and the energy structure transition. Finally, international comparative studies can be conducted to systematically explore the differences between China and other countries in the construction of social credit systems and their varying influences on green behaviors, thereby providing policy insights for improving China’s social credit system and promoting high-quality green development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and writing, W.Z.; methodology and software, T.Y.; formal analysis, J.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 72504110), the Jiangsu Provincial Social Science Planning Fund (Grant No. 2024GLC003), and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant No. 2024M760571).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Liu, M.; Li, S.; Li, Y.; Shi, J.; Bai, J. Evaluating the synergistic effects of digital economy and government governance on urban low-carbon transition. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 105, 105337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, W. With great power comes great responsibility: Exploring the role of government affiliation in subsidies and water pollution treatment in China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhai, N.; Miao, J.; Sun, H. Can Green Finance Effectively Promote the Carbon Emission Reduction in “Local-Neighborhood” Areas?—Empirical Evidence from China. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belloc, F.; Bimonte, S. Environmental regulation and pollution abatement under incremental innovation. Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 2025, 75, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manioudis, M.; Meramveliotakis, G. Broad strokes towards a grand theory in the analysis of sustainable development: A return to the classical political economy. New Political Econ. 2022, 27, 866–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Yang, Y.; Hua, M.; Chan, K.C. Social credit scoring system and corporate pollution governance: Insights from China’s Social Credit System Construction. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 96, 103774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klarin, T. The Concept of Sustainable Development: From its Beginning to the Contemporary Issues. Zagreb Int. Rev. Econ. Bus. 2018, 21, 67–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, B.K.; Tone, K. Radial and Non-radial Decompositions of Profit Change: With an Application to Indian Banking. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2009, 196, 1130–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, D.; Zhang, L.; Yin, Y. Social Trust and Green Technology Innovation: Evidence from Listed Firms in China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caglar, A.E.; Uche, E.; Yagis, O.; Ngepah, N. On the Path to Green Economy: Can Green Foreign Direct Investment Accelerate the Success of Climate Action? Sustain. Dev. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.C.; Lee, C.C. How does green finance affect green total factor productivity? Evidence from China. Energy Econ. 2022, 107, 105863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Chen, H.; Tang, H.; Chen, M. Can the Chinese Cultural Consumption Pilot Policy Facilitate Sustainable Development in the Agritourism Economy? Agriculture 2025, 15, 1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Meng, C.; Tan, J.; Zhang, G. Do smart cities promote a green economy? Evidence from a quasi-experiment of 253 cities in China. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2023, 99, 107009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Ding, X.; Chen, M.; Song, H.; Imran, M. The Impact of Resource Spatial Mismatch on the Configuration Analysis of Agricultural Green Total Factor Productivity. Agriculture 2025, 15, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, Q. Impact of digital transformation in agribusinesses on total factor productivity. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2024, 27, 843–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Ayele, S.; Worako, T.K. The political economy of green industrial policy in Africa: Unpacking the coordination challenges in Ethiopia. Energy Policy 2023, 179, 113633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Kong, S. The effect of environmental regulation on green total-factor productivity in China’s industry. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2022, 94, 106757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinson, A.; Taylor, M. Unmasking the pollution haven effect. Int. Econ. Rev. 2008, 49, 223–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Shang, Y.; Magazzino, C.; Madaleno, M.; Mallek, S. Multi-step impacts of environmental regulations on green economic growth: Evidence in the lens of natural resource dependence. Resour. Policy 2023, 85, 103919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Antunes, J.; Wanke, P.; Chen, Z. Ecological efficiency assessment under the construction of low-carbon city: A perspective of green technology innovation. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2022, 65, 1727–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, X.; He, Z.; Lu, B. The effect of digital inclusive finance on the development of the green economy in china: A panel data analysis. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Tu, A.; Liao, F.; Li, G. Does Confucian culture affect the efficiency of corporate green investments? Evidence from heavily polluting enterprises. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2024; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Tang, B.; Li, L. Are Good Deeds Rewarded?—The Impact of Traditional Morality and Modern Responsibility on Green Innovation. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, A.; Yuan, X.; Fan, S.; Wang, S. The Impact and Mechanism of Corporate ESG Construction on the Efficiency of Regional Green Economy: An Empirical Analysis Based on Signal Transmission Theory and Stakeholder Theory. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.S. Datafication, dataveillance, and the social credit system as China’s new normal. Online Inf. Rev. 2019, 43, 952–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X. Social credit environment, financing levels, and criminal crime rates. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 85, 107974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Yu, Y.; Fei, Q. Social credit and patent quality: Evidence from China. J. Asian Econ. 2022, 84, 101570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, D.; Munasib, A.; Chen, X. Social trust and international trade: The interplay between social trust and formal finance. Rev. World Econ. 2014, 150, 693–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Liu, X.; Wang, C. Social Trust and Bank Loan Financing: Evidence from China. Abacus-A J. Account. Financ. Bus. Stud. 2016, 52, 374–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.; Cao, C.; Chan, K. Social trust environment and irm tax avoidance: Evidence from China. North Am. J. Econ. Financ. 2017, 42, 374–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Wang, K.; Liu, J. Can social trust foster green innovation? Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 66, 105644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zan, H.; Jiang, K.; Ma, J. Social trust, green finance, and enterprise innovation. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 63, 105386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, J. Social trust, cultural trust, and the will to sacrifice for environmental protections. Soc. Sci. Res. 2023, 109, 102779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Wang, Y. Does social trust affect firms’ESG performance? Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 93, 103153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zeng, H. Can social trust promote the professional division of labor in firms? Evidence from China. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 89, 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werbach, K.; Cornell, N. Contracts Ex Machina. Duke Law J. 2017, 67, 313–382. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Cui, R.; Gao, H.; Lu, X.; Hu, X. Can the construction of the social credit system improve the efficiency of corporate investment? Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 96, 103510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Yu, Z.; Tian, G.; Wang, D.; Wen, Y. Market competition, environmental, social and corporate governance investment, and enterprise green innovation performance. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 77, 107057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, L.J. Impact of Environmental Regulation on Green Technology Innovation: Empirical Analysis Based on Panel Data of the Cities in Yellow River Basin. Res. Financ. Econ. Issue 2020, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).