Mine Emergency Rescue Capability Assessment Integrating Sustainable Development: A Combined Model Using Triple Bottom Line and Relative Difference Function

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Basic Theories

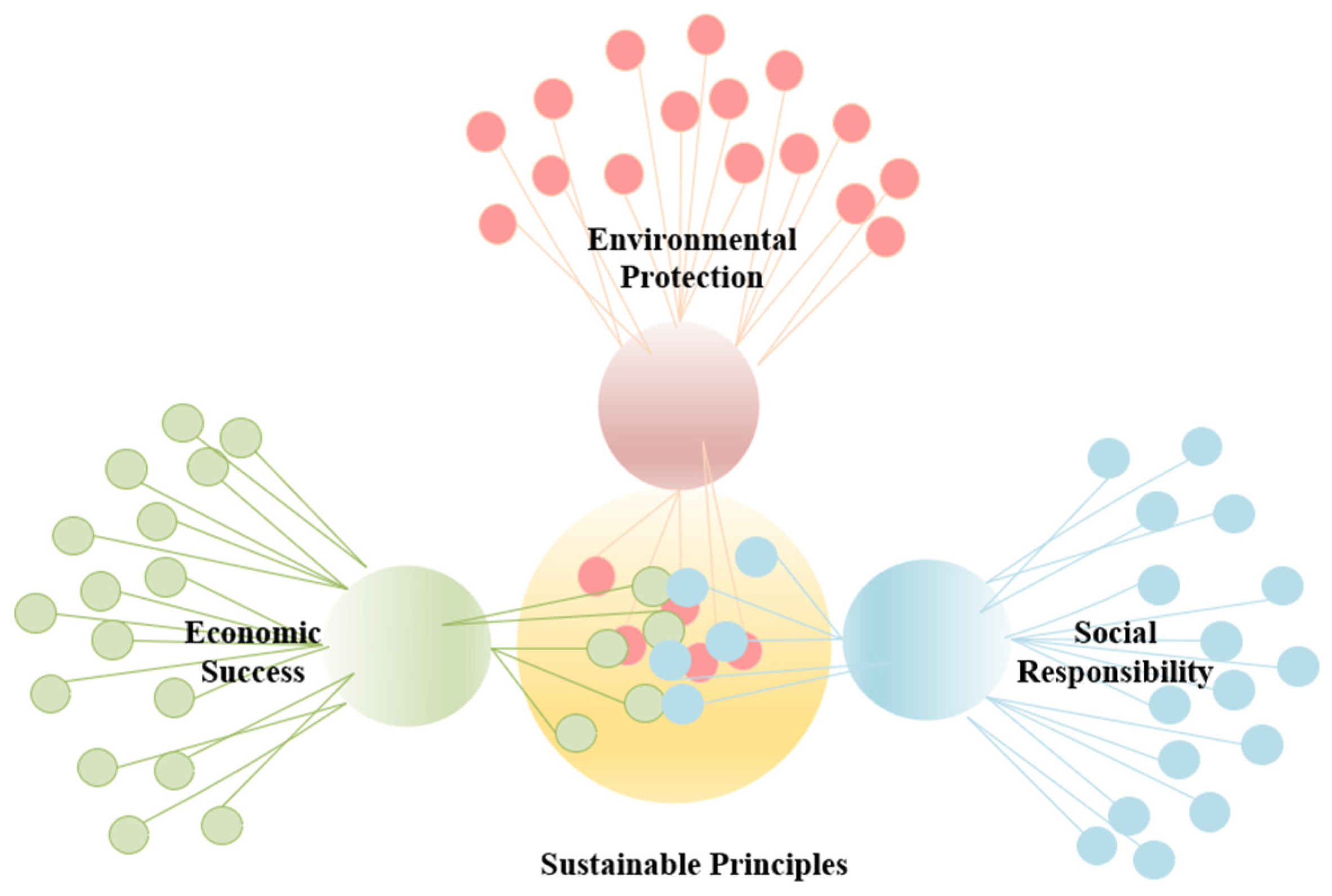

2.1. Principle of TBL

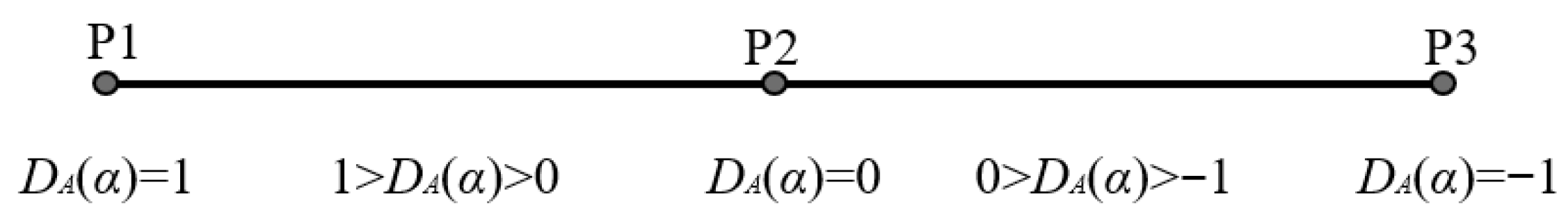

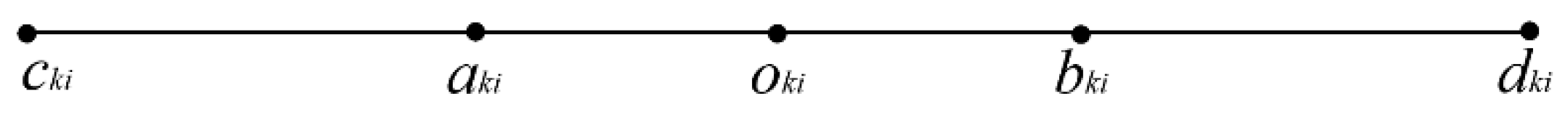

2.2. Principle of RDF

- RDF

- 2.

- Relative affiliation

- 3.

- Adaptability of RDF

2.3. Weighting Methods

- (1)

- The G1Method

- (2)

- Entropy weight method

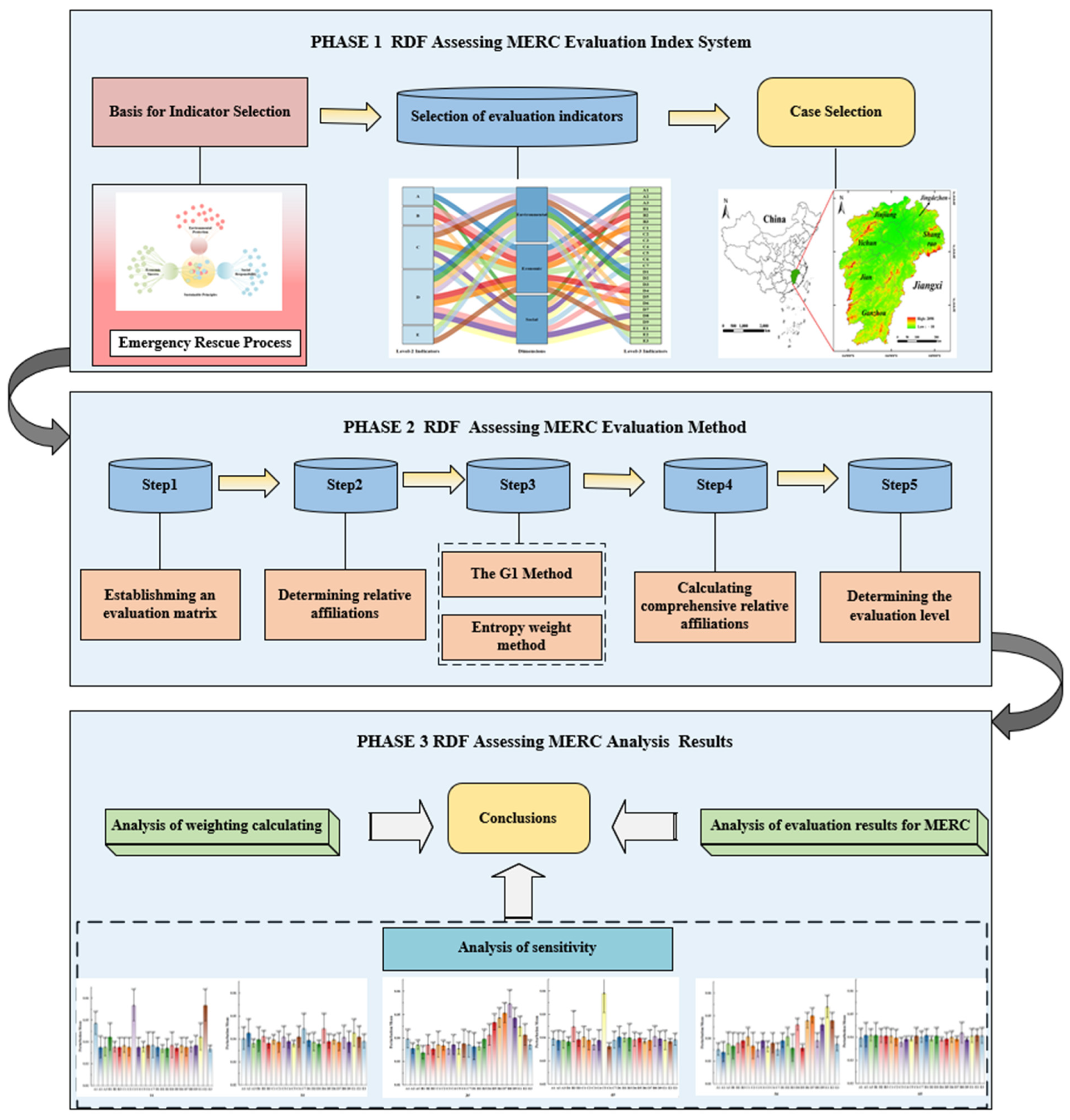

3. Evaluation Procedures for RDF Assessing MERC

3.1. Establishing the Characteristic Value Evaluation Matrix

3.2. Determining Relative Membership Degree

3.3. Calculating Combined Weights

3.4. Calculating Comprehensive Relative Membership Degree

3.5. Determining the Evaluation Level

4. Model Application and Analysis

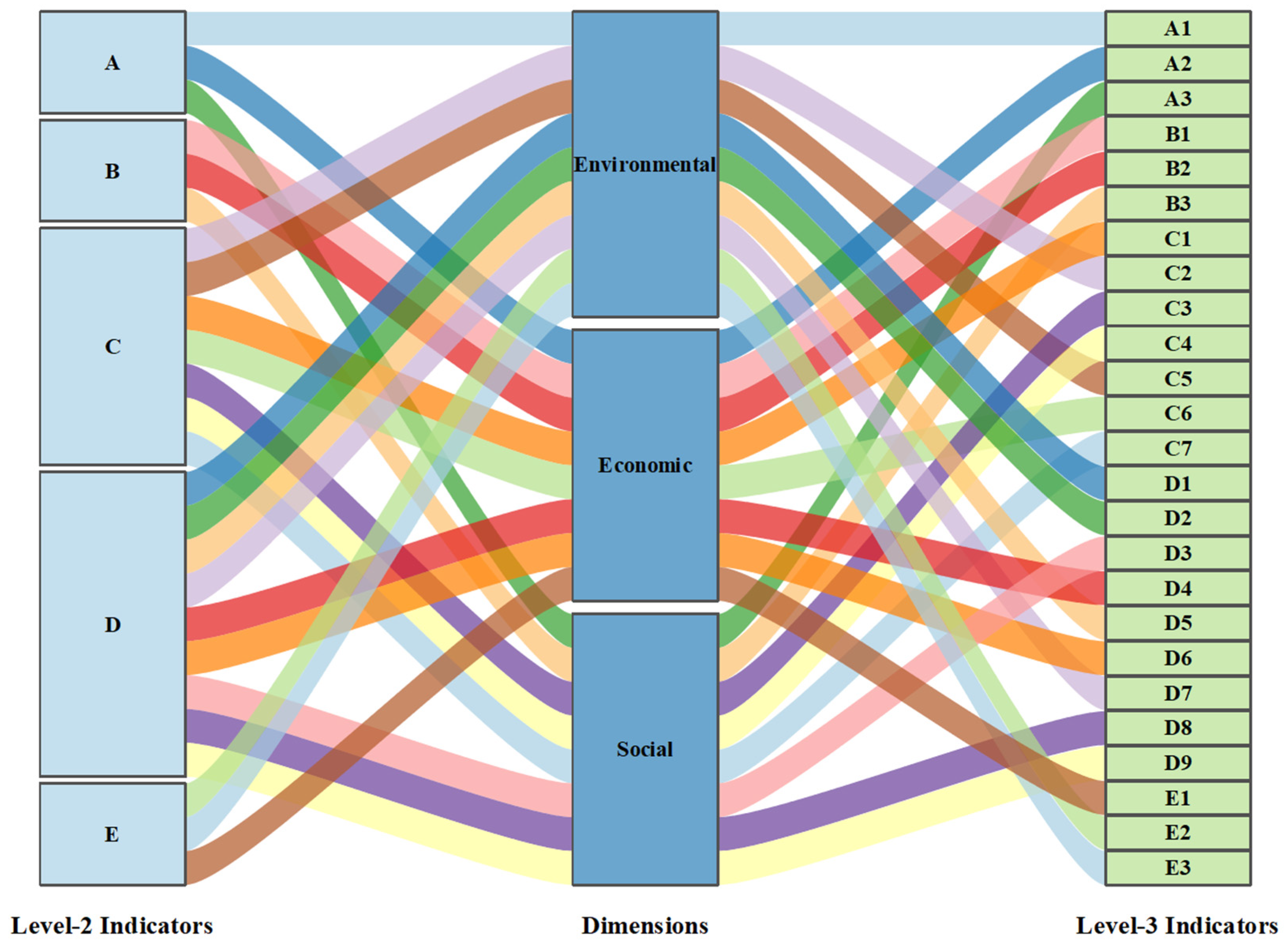

4.1. Establishment of MERC Evaluation Index System for Metal Mine

4.1.1. Description of Evaluation Indicators

- A.

- Organization and institutional construction

- B.

- Monitoring and early warning

- C.

- Emergency preparation

- D.

- Emergency response

- E.

- Recovery and reconstruction

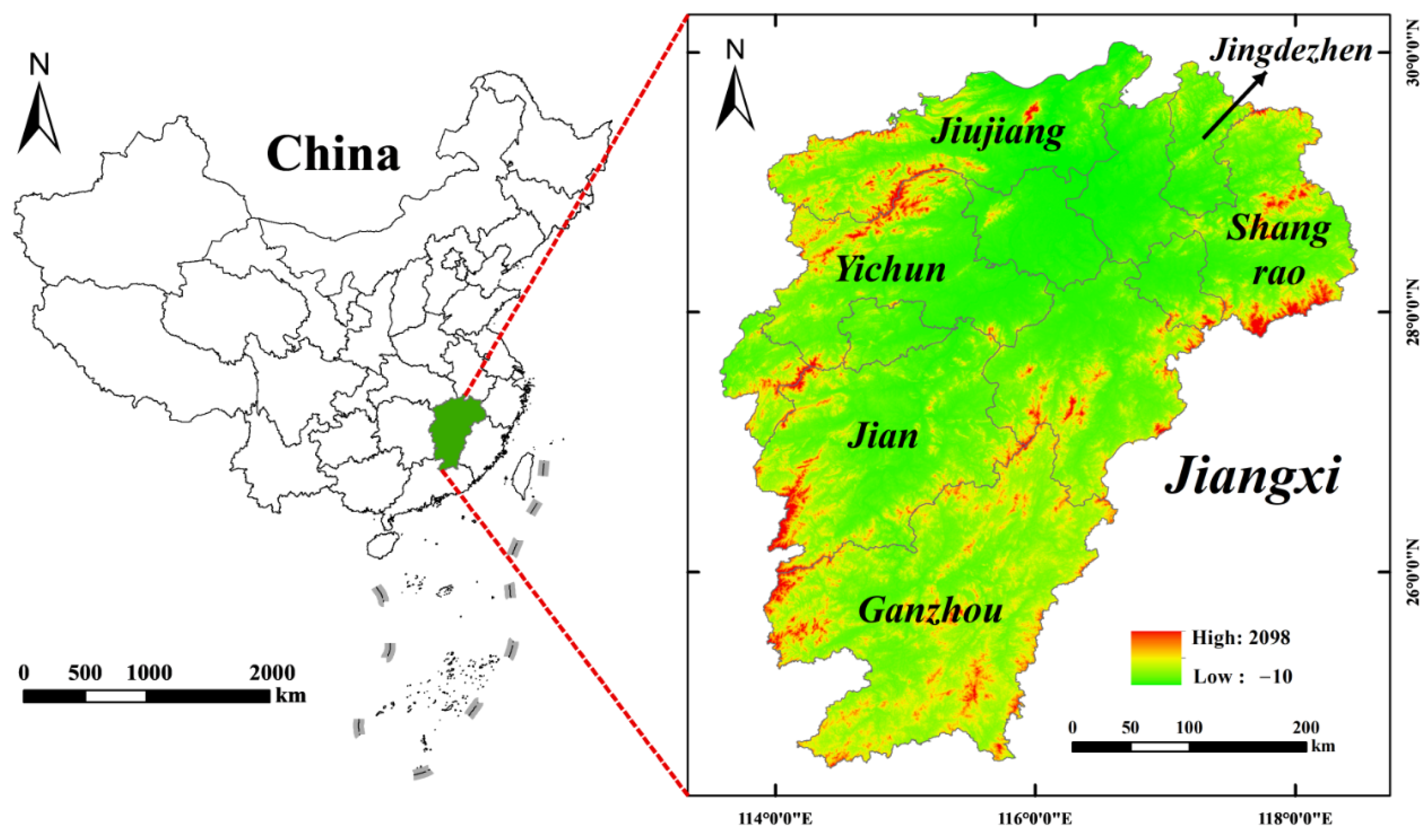

4.1.2. Research Field

4.1.3. Grade Classification Standards

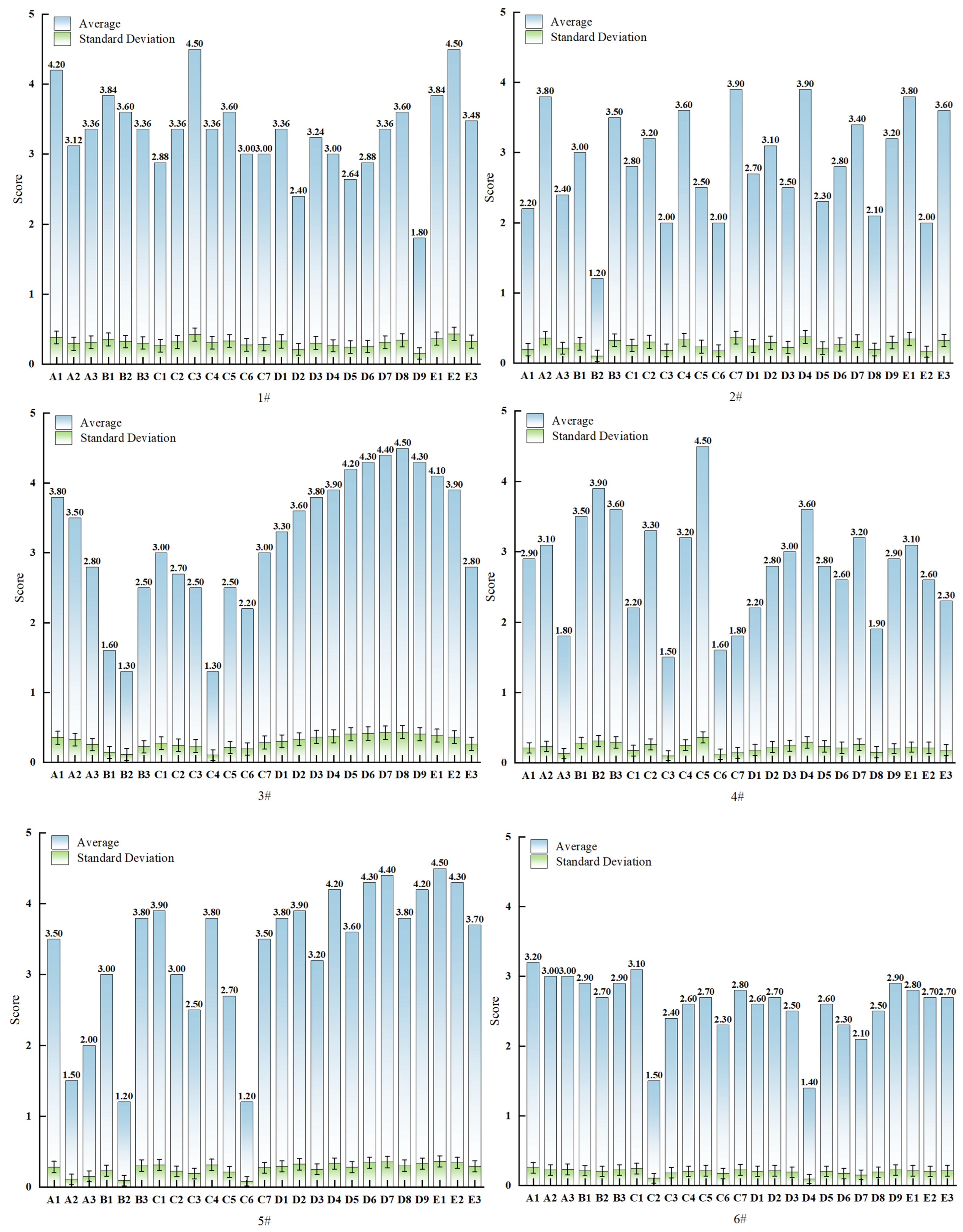

4.2. Quantitative Scoring Results for Evaluation Indicators

4.3. Determination of Relative Membership Degree for MERC Evaluation Indicator in Mines

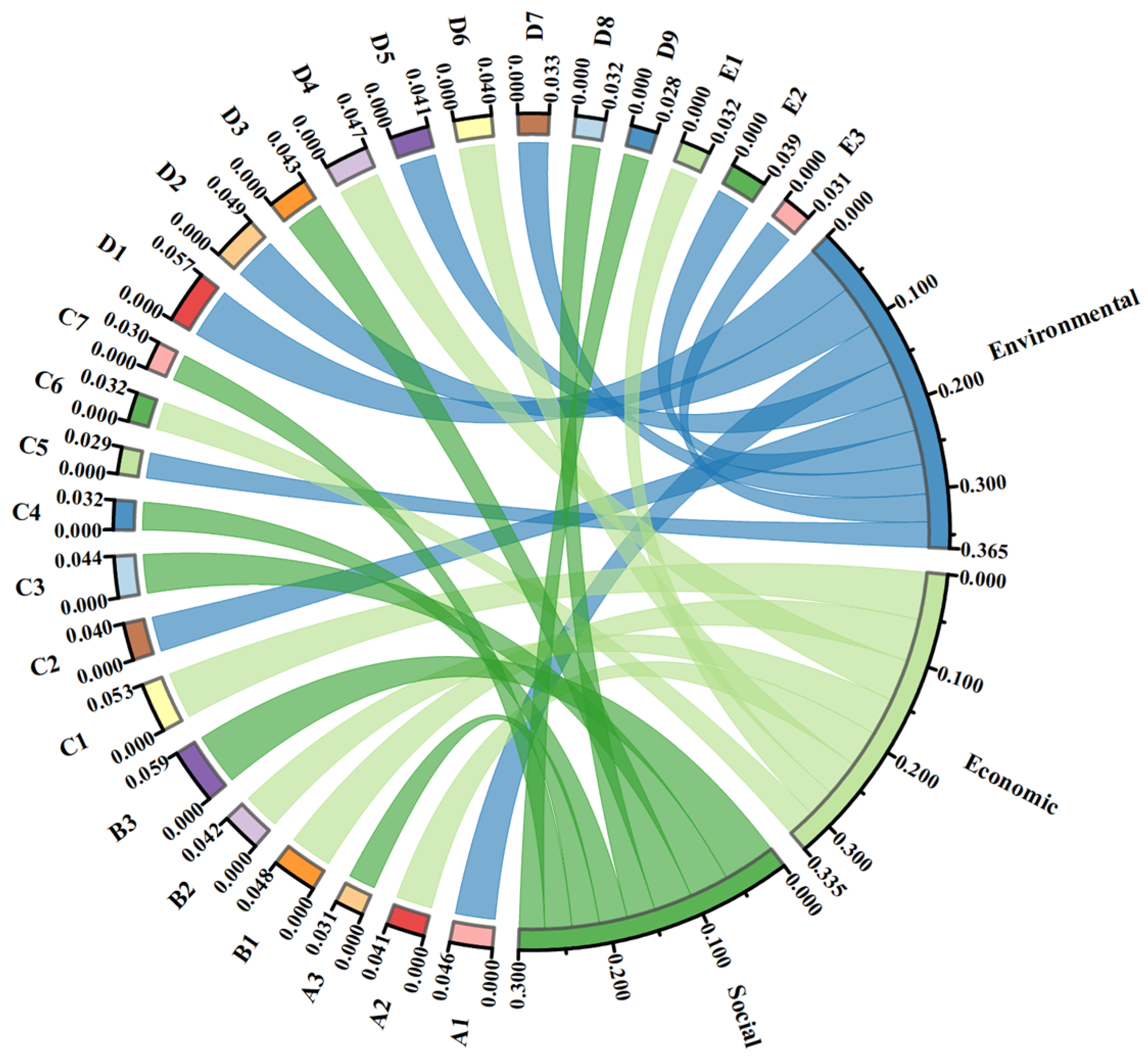

4.4. Weight Assignment to MERC Evaluation Indicator in Mine

4.5. Determination of Comprehensive Relative Membership Degree for MERC Evaluation Indicator in Mine

4.6. Determination of Evaluation Level for MERC in Mine

5. Results Analysis

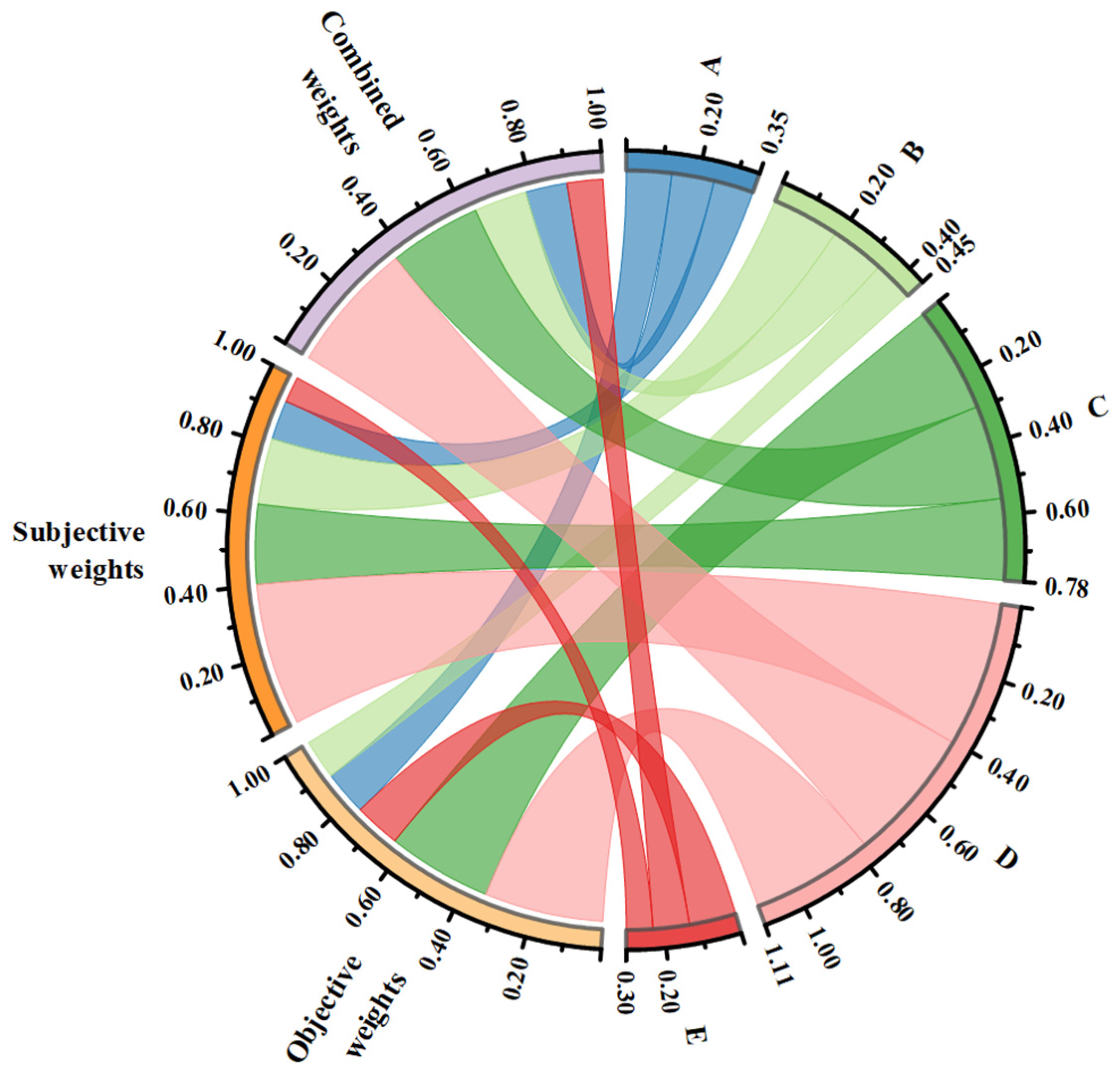

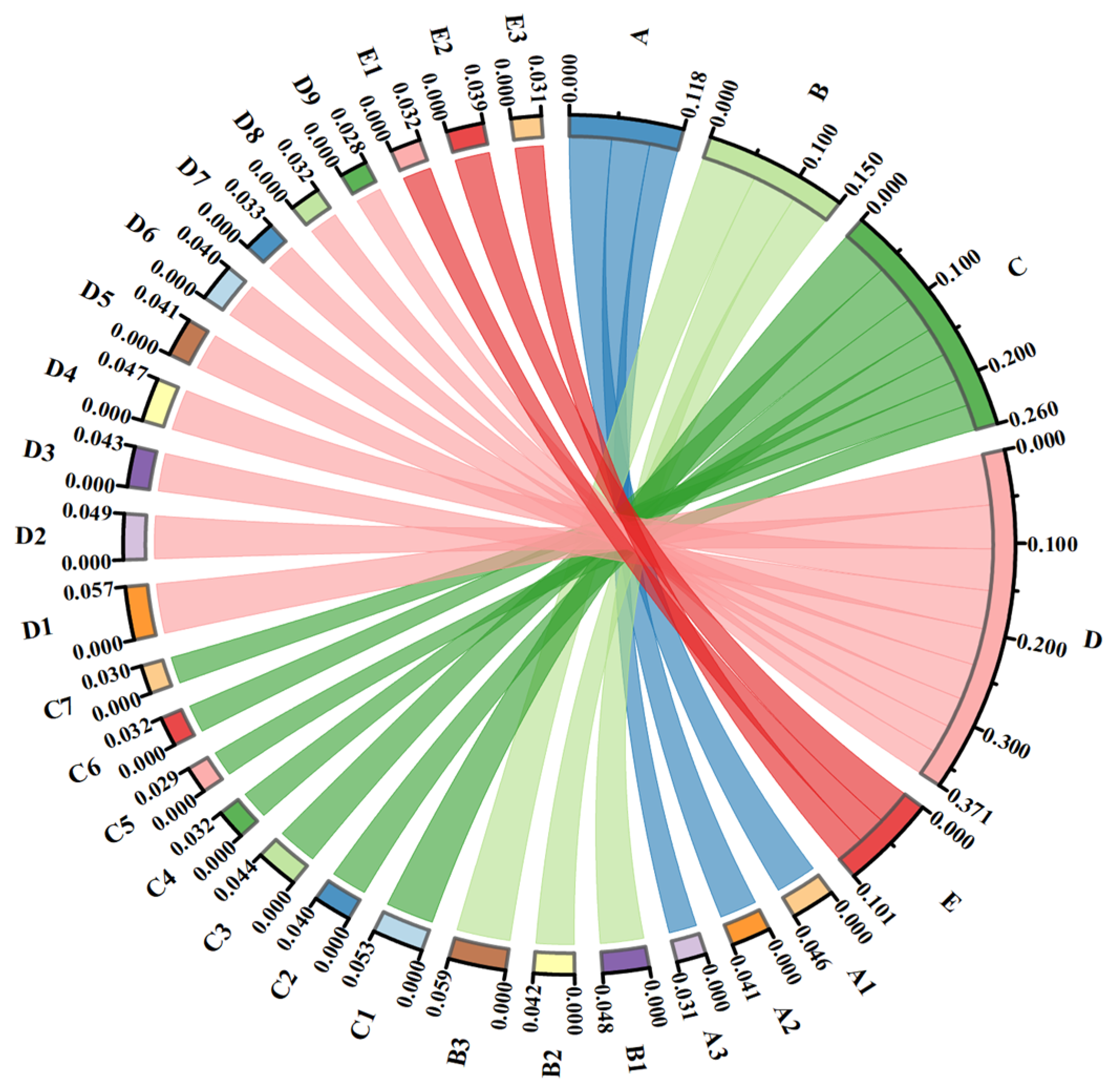

5.1. Weight Calculation Results Analysis

5.2. Policy Recommendations

6. Comparative Analysis of Evaluation Models

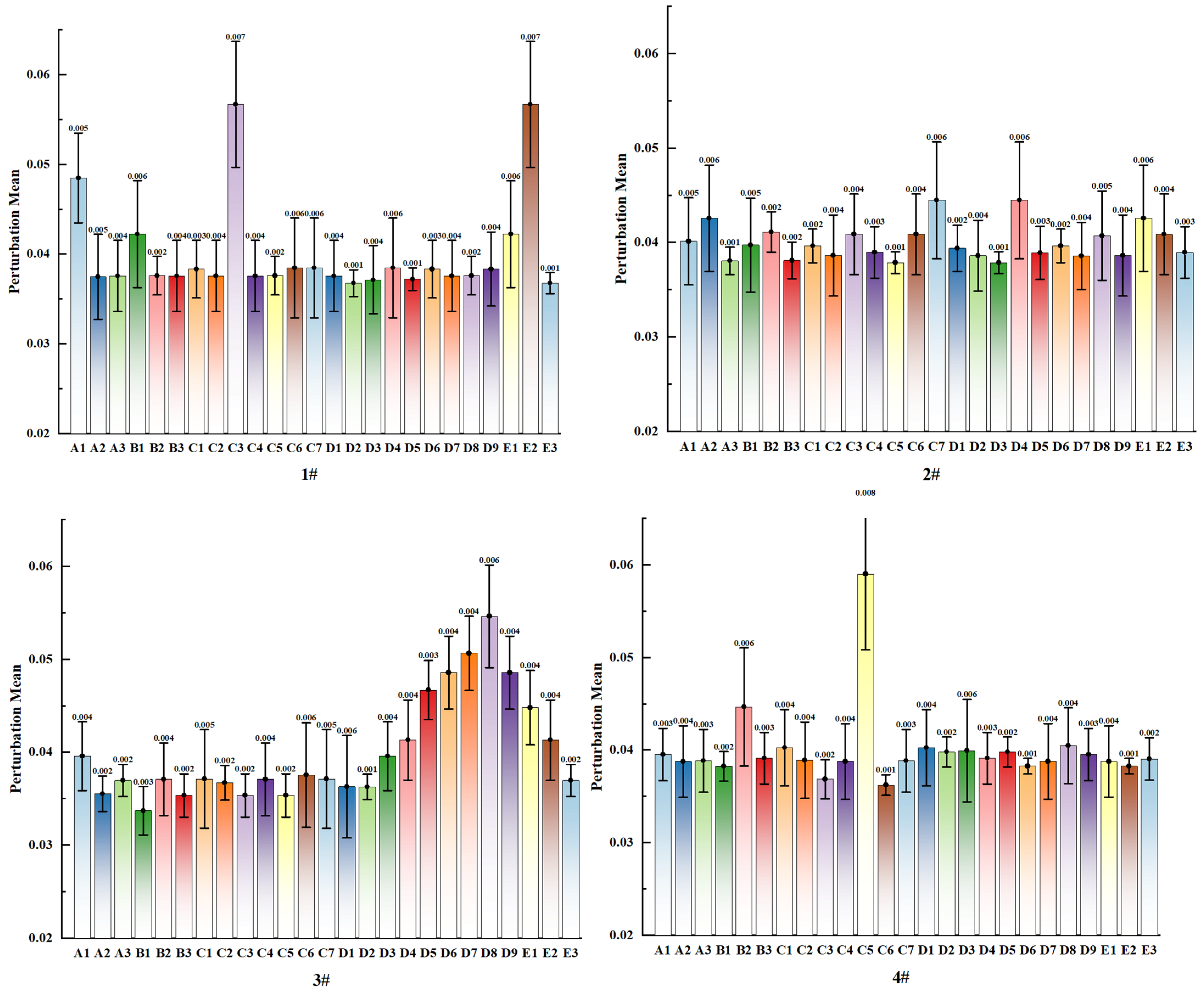

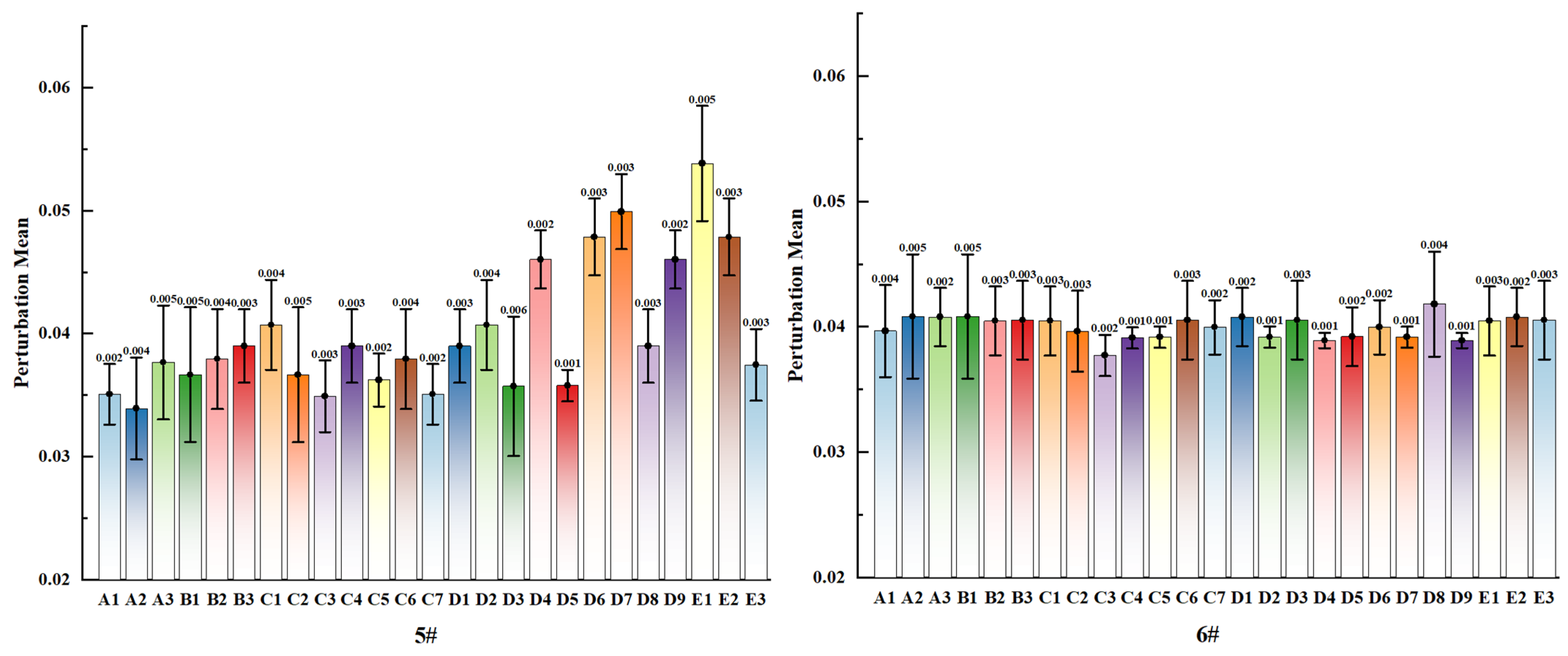

6.1. Sensitivity and Robustness Analysis

6.2. Comparison and Analysis of Evaluation Results for MERC

6.3. Limitations of the Model

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yu, H.; Li, S.; Yu, L.; Wang, X. The Recent Progress China Has Made in Green Mine Construction, Part II: Typical Examples of Green Mines. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Ali, S.H.; Bazilian, M.; Radley, B.; Nemery, B.; Okatz, J.; Mulvaney, D. Sustainable Minerals and Metals for a Low-Carbon Future. Science 2020, 367, 30–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollack, K.; Bongaerts, J.C.; Drebenstedt, C. Towards Low-Carbon Economy: A Business Model on the Integration of Renewable Energy into the Mining Industry. In Proceedings of the 28th International Symposium on Mine Planning and Equipment Selection—MPES 2019; Topal, E., Ed.; Springer Series in Geomechanics and Geoengineering; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 422–430. ISBN 978-3-030-33953-1. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Jiskani, I.M.; Lin, A.; Zhao, C.; Jing, P.; Liu, F.; Lu, M. A Hybrid Decision Model and Case Study for Comprehensive Evaluation of Green Mine Construction Level. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 3823–3842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D. Exploration and application of artificial intelligence in mine emergency rescue. Shaanxi Coal 2024, 43, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.; Verburg, A.; Tukkaraja, P. Internet of Things–Based Command Center to Improve Emergency Response in Underground Mines. Saf. Health Work 2022, 13, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Cheng, G.; Li, Z.; Zhu, W.; Wu, F. Visualized analysis of mine emergency rescue in China based on bibliometrics. Saf. Coal Mine 2023, 54, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Xv, Y.; Xie, D.; Liu, C.; Zhong, C. The risk assessment of water bursting based on combination rule of distance function. China Min. Mag. 2021, 30, 162–167. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, R. Study on the impact of multi-disaster chains on emergency rescue. China Min. Mag. 2021, 30, 161–165. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, B. Risk Decision Evaluation of Mine Gas Explosion Emergency Rescue Based on Vague Set. In Proceedings of the 2022 World Automation Congress (WAC), San Antonio, TX, USA, 11–15 October 2022; pp. 553–557. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Shi, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, W. Modified Stochastic Petri Net-Based Modeling and Optimization of Emergency Rescue Processes during Coal Mine Accidents. Geofluids 2021, 4141236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, Q.; Jiang, B.; Lu, X.; Li, S.; Fu, Q. Construction of green, low-carbon and multi-energy complementary system for abandoned mines under global carbon neutrality. J. China Coal Soc. 2023, 47, 2131–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Kang, Q.; Zou, Y.; Yu, S.; Ke, Y.; Peng, P. Research on Comprehensive Evaluation Model of Metal Mine Emergency Rescue System Based on Game Theory and Regret Theory. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Hao, Y.; Wei, J.; Zhang, L. Research on the Evaluation of Emergency Management Synergy Capability of Coal Mines Based on the Entropy Weight Matter-Element Extension Model. Processes 2023, 11, 2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, K.; Qiu, D.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Z.; Jin, Y. Coal Mine Fire Emergency Rescue Capability Assessment and Emergency Disposal Research. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Li, Y. Evaluation of Coal Mine Water Permeable Emergency Rescue Capability Based on Combined Weighting. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2023, 23, 2353–2361. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, S.; Gao, L.; Fan, B.; Shun, W.; Zhao, Z.; Cai, X. Capability evaluation of coal mine emergency management based on WSR methodology. J. Xi’an Univ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 42, 647–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Reniers, G. Development of a Risk Assessment Approach by Combining SPA-Fuzzy Method with Petri-Net. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2024, 91, 105372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Shi, Y.; Pang, C.; Li, H.; Lin, J. Evaluation Model of Coal Mine Emergency Rescue Resource Allocation Based on Weight Optimization TOPSIS Method. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, L.; Zhou, R.; Yan, J.; Guo, H. Construction and application of maturity evaluation model of coal mine emergency rescue ability. China Saf. Sci. J. 2021, 31, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Xue, K.; Wang, W.; Cui, X.; Liang, R.; Wu, Z. Coal and Gas Protrusion Risk Evaluation Based on Cloud Model and Improved Combination of Assignment. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S. Theory and Model of Variable Fuzzy Sets and Its Application; Dalian University of Technology Press: Dalian, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, J.; Wang, W.; Li, S. Risk Assessment of Highway Construction Based on Relative Difference Function. J. Chongqing Jiaotong Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2020, 39, 81–85+99. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, B.; Ke, Y.; Qing, C.; Zhang, H.; Huang, H.; Fang, L.; Wang, C.; Tao, T. Risk Recognition of Metal Mine Goaf Based on Rel-ative Difference Function. Gold Sci. Technol. 2021, 29, 440–448. [Google Scholar]

- Alhaddi, H. Triple Bottom Line and Sustainability: A Literature Review. Bus. Manag. Stud. 2015, 1, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, C.S.; Chong, H.-Y.; Jack, L.; Mohd Faris, A.F. Revisiting Triple Bottom Line within the Context of Sustainable Construction: A Systematic Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 252, 119884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhu, J.P. Review of Research Progress on Comprehensive Evaluation Methods. Stat. Decis. 2012, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; He, N. Study on Classification and Applicability of Comprehensive Evaluation Methods. Stat. Decis. 2022, 38, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, J.; Ma, H.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, R. An Improved Power Quality Evaluation for LED Lamp Based on G1-Entropy Method. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 111171–111180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liang, Z. Research on Variable Weight Synthesizing Model for Transformer Condition Assessment. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 941985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Cheng, Z.; Kong, D. Evaluation of Mining Capacity of Mines Using the Combination Weighting Approach: A Case Study in Shenmu Mining Area in Shaanxi Province, China. Sci. Prog. 2021, 104, 00368504211044032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Ke, Y.; Wang, C.; Zeng, Z.; Liao, B. Standardization grade evaluation for non-coal mine safety based on matter-element extension model with variable weight. Nonferrous Met. Sci. Eng. 2021, 12, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Gu, J. Risk Evaluation of Mine-Water Inrush Based on Comprehensive Weight Method. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2023, 41, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Li, S.; Lin, H. Establishment of Assessment Index System for the Emergency Capability of the Coal Mine Based on SEM. Procedia Eng. 2011, 26, 2313–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- National Mine Safety Administration. Mine Rescue Regulations; National Mine Safety Administration: Beijing, China, 2024.[Green Version]

- AQ 1009-2021; Standardized Assessment Criteria for Mine Rescue Teams. Ministry of Emergency Management: Beijing, China, 2021.[Green Version]

- AQ 1123-2023; Mine Rescue Teams Risk Pre-Control Management System. Ministry of Emergency Management: Beijing, China, 2023.[Green Version]

- State Administration for Market Regulation. General Rules for Evaluation of Green Mines; State Administration for Market Regulation: Beijing, China, 2024.[Green Version]

- Ministry of Natural Resources of the People’s Republic of China. Construction Specifications for Green Mine Development; Ministry of Natural Resources of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2018.[Green Version]

- Shang, D.; Yin, G.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Jiang, C.; Kang, X.; Liu, C.; Zhang, C. Analysis for Green Mine (Phosphate) Performance of China: An Evaluation Index System. Resour. Policy 2015, 46, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Qiu, Z.; Li, M.; Shang, J.; Niu, W. Evaluation and Empirical Research on Green Mine Construction in Coal Industry Based on the AHP-SPA Model. Resour. Policy 2023, 82, 103503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Jiskani, I.M.; Jinliang, C.; Yan, H. Evaluation and Future Framework of Green Mine Construction in China Based on the DPSIR Model. Sustain. Environ. Res 2020, 30, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Liu, X.; Hou, H. Analysis of green mine evaluation index. Chin. Acad. Nat. Resour. Econ. 2020, 29, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Huang, J.; Liang, Y.; Cheng, L. Comprehensive Evaluation of Green Mine Construction Level Considering Fuzzy Factors Using Intuitionistic Fuzzy TOPSIS with Kernel Distance. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 16884–16898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrayeva, A.S.; Turdaliyeva, B.S.; Aimbetova, G.Y. Analysis of the Organization and Conduct of Emergency Rescue Activities. SRP 2020, 11, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, X.; Cao, Q.; Li, D.; Wang, J. Research and Calculation on Emergency Rescue Reliability Model through Entropy Weight-BP Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Conference on Telecommunications, Optics and Computer Science (TOCS), Shenyang, China, 10–11 December 2021; pp. 795–798. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Y.; Wu, X.; Na, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, J. Analysis of green and high quality development of the mining industry in Jiangxi province. China Min. Mag. 2019, 28, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, B.J.E.; Eriksson, P. A Maturity Model to Guide Inter-Organisational Crisis Management and Response Exercises. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 106, 104413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, R.; Wang, C.; Chen, X. Research on Emergency Rescue Capability of Coal Mine Based on Vague Set Theory. Coal Technol. 2016, 35, 320–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C.; Yang, Q.; Liang, J.; Ma, H. Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation with AHP and Entropy Methods and Health Risk Assessment of Groundwater in Yinchuan Basin, Northwest China. Environ. Res. 2022, 204, 111956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Si, Q. Multiple-level Projection of Indexes and the Analysis of Causes on A Fuzzy Evaluation Conclusion. Oper. Res. Manag. Sci. 2023, 32, 126–131+137. [Google Scholar]

| rk | Relative Importance |

|---|---|

| 1.0 | Equal importance |

| 1.2 | Slightly more important |

| 1.4 | Comparatively more important |

| 1.6 | Significantly more important |

| 1.8 | Extremely important |

| 1.1, 1.3, 1.4, 1.5, 1.7 | Between the above |

| Indicator | Maturity Level | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level I | Level II | Level III | Level IV | Level V | |

| (0.0, 1.0] | (1.0, 2.0] | (2.0, 3.0] | (3.0, 4.0] | (4.0, 5.0] | |

| C1 | Rescue personnel have no mastery of skills related to environmental emergency response. | Only a few team members understand basic concepts, but their practical operational skills are poor. | Most team members have received training and execute basic response procedures. | Team members are highly skilled, capable of flexibly responding to complex disaster scenarios and minimizing secondary damage. | The team possesses expert-level response capabilities and optimizing new techniques, thereby leading the industry. |

| C2 | The emergency plan contains no dedicated measures for ecological impact prevention and control. | The emergency plan includes ecological protection but lacks specific implementation processes. | The emergency plan includes a dedicated chapter, with clear measures covering major risk scenarios. | The ecological control module is deeply integrated with core rescue processes, with strong practicality. | The emergency plan is ecological prevention and control measures representing industry best practices. |

| C3 | No formal risk report has been generated, with information being fragmented and disorganized. | A basic report exists, but it merely lists certain safety risks in a simplistic manner. | A regular risk reporting system has been established, enabling systematic identification of safety and ecological risks. | The report comprehensively analyzes risk interrelationships and prospectively evaluates potential economic. | A dynamic risk early warning model has been established, with reports providing precise quantitative analysis and undergoing continuous optimization. |

| C4 | No emergency drills have ever been conducted. | Occasionally, one drill is conducted annually, but the effectiveness is negligible. | Comprehensive drills are conducted regularly1–2 times each year, and ecological measures are basically validated. | Drills are conducted with high frequency ≥2 times per year and enhance coordination and operational capabilities. | Drill frequency, quality, and innovation serve as industry benchmarks. |

| C5 | No allocation has been planned for the emergency funds for any purposes related to ecological or environmental protection. | A minimal amount of funds is allocated, but the proportion is extreme, <5%, with usage lacking planning. | The proportion of ecological emergency funds meeting basic requirements 5–10%, and usage is standardized. | The proportion of funds is relatively 10–20%. Allocations are dynamically optimized based on demand. | The proportion of funds is high and stable (>20%), with an innovation fund established to support technology introduction and upgrades. |

| C6 | No low-carbon emergency equipment has been stockpiled. | Only a minimal amount of conventional material, with no management system. | Quantitative stockpiling conducted in accordance with standards, and a regular inspection and update mechanism in place. | Material reserves are sufficient, with proactive adoption of new environmentally friendly materials and equipment, supported by informatized management. | Intelligent and networked precise allocation and supply chain management have been achieved, ensuring optimal material efficiency. |

| C7 | No relevant publicity or training activities have been conducted. | Only sporadic, informal publicity activities have been carried out, with no institutionalized framework. | An annual publicity and education plan has been formulated, with regular training conducted for internal employees. | A comprehensive internal and external publicity system has been established, with content continuously improved based on feedback. | The enterprise, in collaboration with the community and relevant stakeholders, has achieved significant publicity impact and high social recognition. |

| No. | y’ | Y | Level | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| θ = 1, β = 1 | θ = 2, β = 1 | θ = 1, β = 2 | θ = 2, β = 2 | |||

| 1# | 3.813 | 3.741 | 3.840 | 3.843 | 3.809 | III close to IV |

| 2# | 3.362 | 3.268 | 3.406 | 3.367 | 3.351 | III close to II |

| 3# | 3.644 | 3.473 | 3.855 | 3.728 | 3.675 | III close to IV |

| 4# | 3.335 | 3.336 | 3.379 | 3.401 | 3.363 | III close to II |

| 5# | 3.838 | 3.595 | 4.156 | 4.000 | 3.897 | III close to IV |

| 6# | 3.083 | 3.004 | 3.132 | 3.113 | 3.083 | III close to II |

| Method | Level of MERC | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1# | 2# | 3# | 4# | 5# | 6# | |

| RDF | III | III | III | III | III | III |

| Vague sets | III | III | III | III | III | III |

| FCA | III | III | III | III | IV | II |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Feng, L.; Xie, J.; Ke, Y. Mine Emergency Rescue Capability Assessment Integrating Sustainable Development: A Combined Model Using Triple Bottom Line and Relative Difference Function. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9948. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17229948

Feng L, Xie J, Ke Y. Mine Emergency Rescue Capability Assessment Integrating Sustainable Development: A Combined Model Using Triple Bottom Line and Relative Difference Function. Sustainability. 2025; 17(22):9948. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17229948

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeng, Lu, Jing Xie, and Yuxian Ke. 2025. "Mine Emergency Rescue Capability Assessment Integrating Sustainable Development: A Combined Model Using Triple Bottom Line and Relative Difference Function" Sustainability 17, no. 22: 9948. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17229948

APA StyleFeng, L., Xie, J., & Ke, Y. (2025). Mine Emergency Rescue Capability Assessment Integrating Sustainable Development: A Combined Model Using Triple Bottom Line and Relative Difference Function. Sustainability, 17(22), 9948. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17229948