The Digital Transformation of Higher Education in the Context of an AI-Driven Future

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Questions

- RQ1. Which digital technologies are most effectively integrated into the educational process?

- RQ2. How does digital transformation affect the quality of higher education?

- RQ3. What opportunities does artificial intelligence provide for the AI-driven educational ecosystem?

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Design

3.2. Participants and Sampling

- Current enrolment as a student;

- Provided informed consent.

3.3. Measures

- Demographics and academic background–information about participants’ age, gender, academic level, and field of study;

- Digital access and infrastructure–availability and quality of internet connection, and access to digital devices;

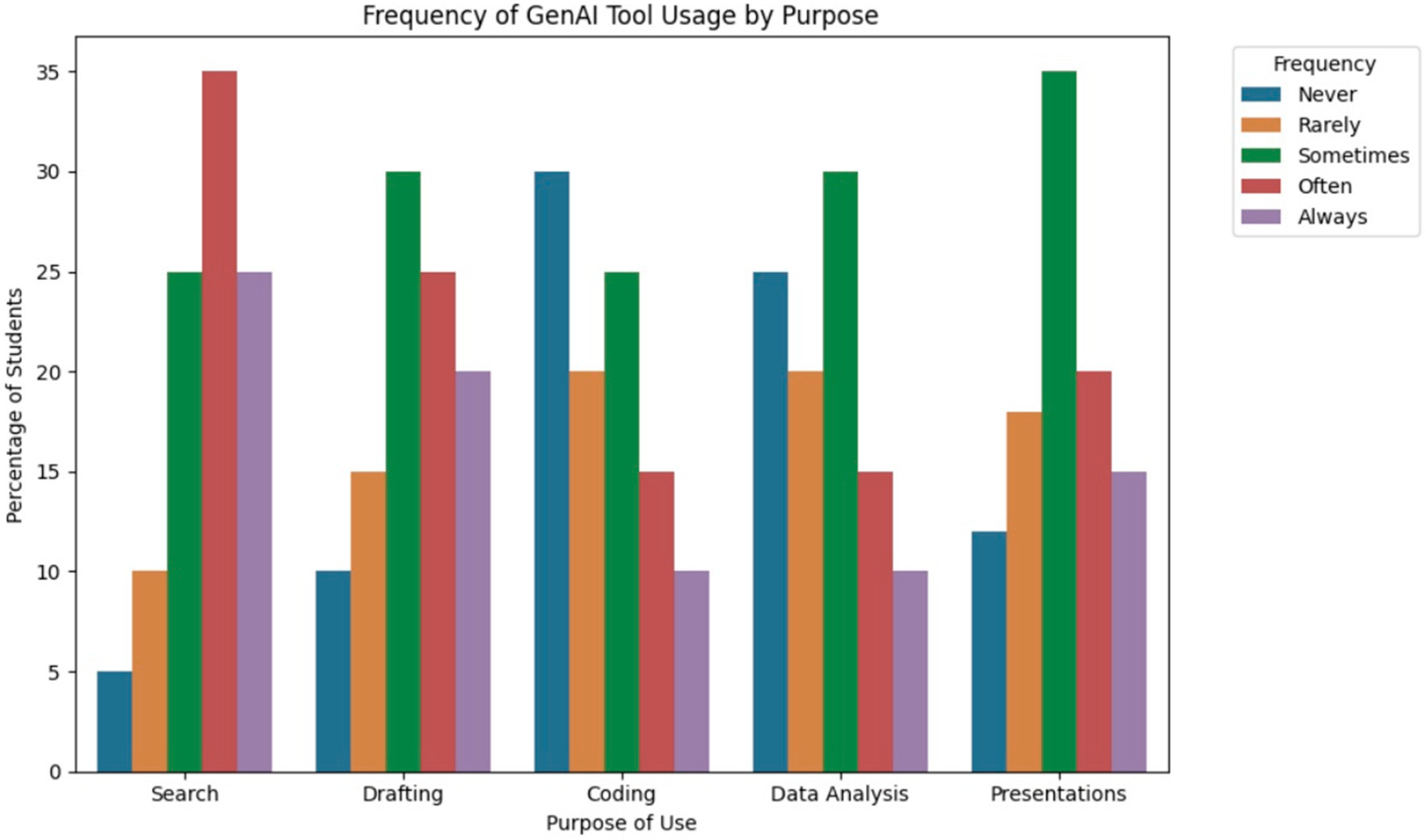

- GenAI tool usage patterns–frequency of use and purposes in academic contexts (e.g., writing, coding, information search, analysis);

- Attitudes and perceived risks–perceived benefits, concerns related to academic integrity, and privacy issues;

- Open-ended questions–reflections on barriers to use and examples of good practices.

3.4. Data Preparation and Statistical Analysis

3.5. Ethical Considerations

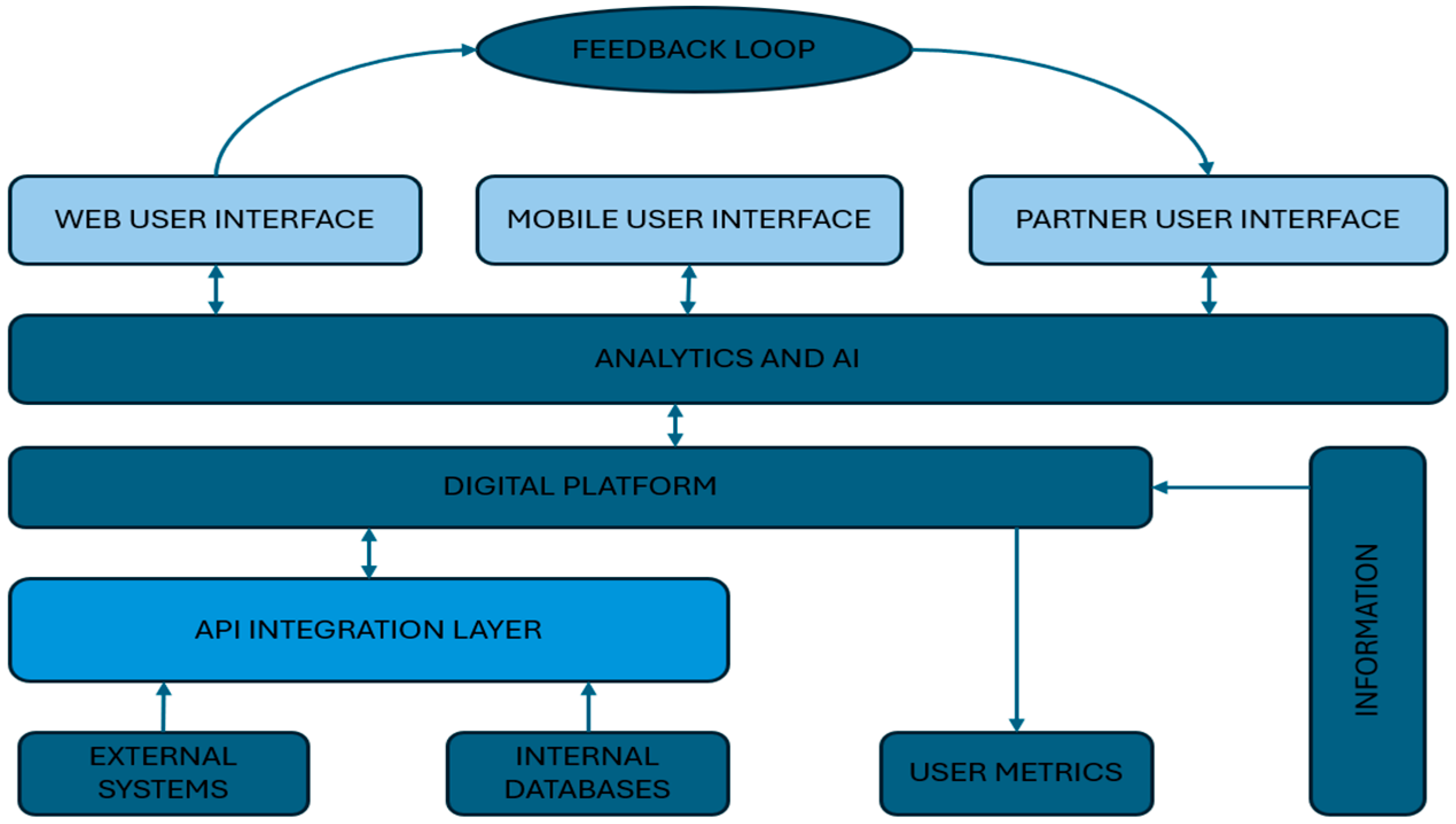

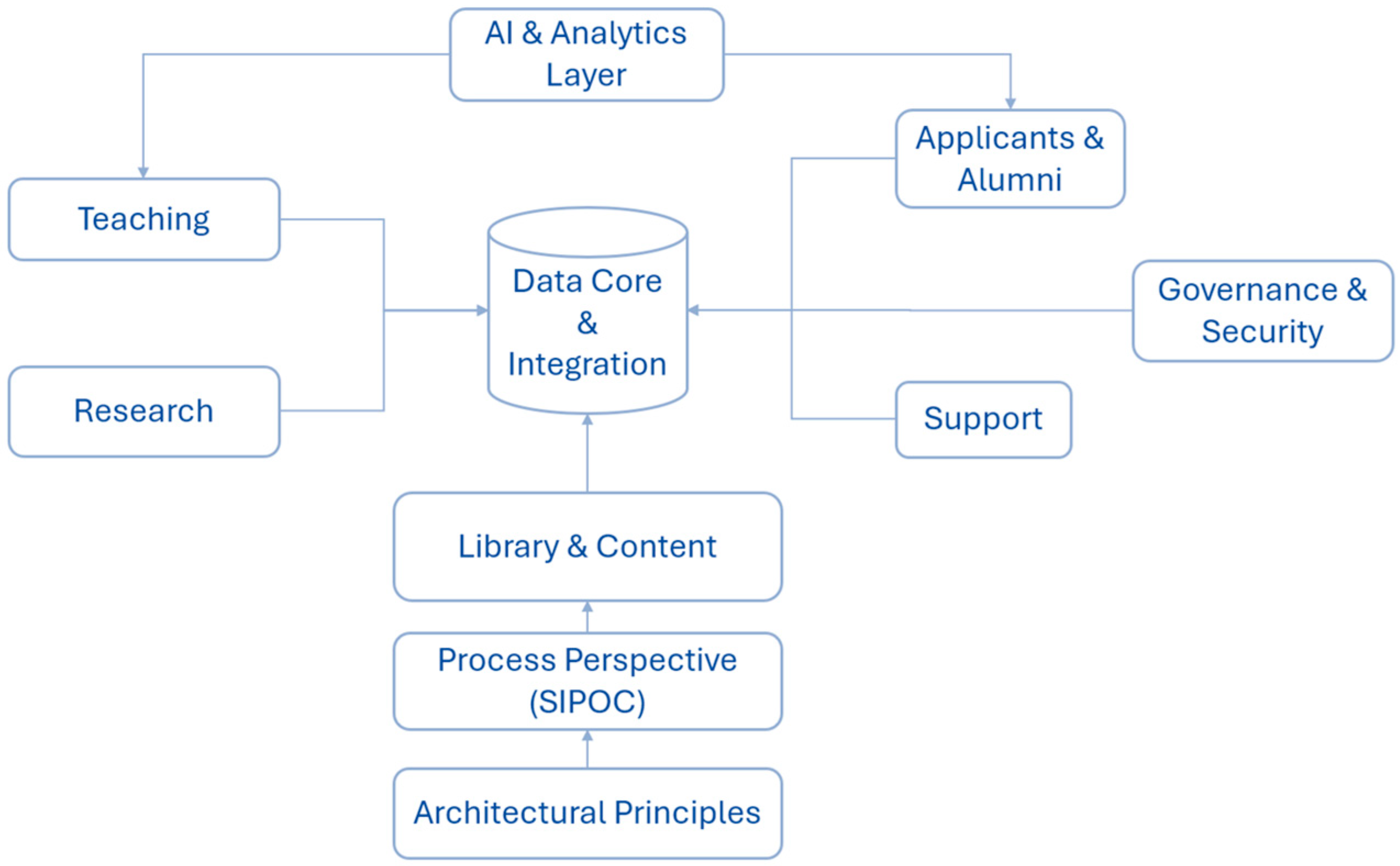

4. The Target Architectural Model of Digital Transformation

- A corporate web interface for employees and clients;

- Mobile applications for quick access to the system functionality;

- Integration interfaces of partner organizations [13].

5. Risk Analysis and Development of Measures to Minimize Them

6. Current State of Digital Transformation in Higher Education

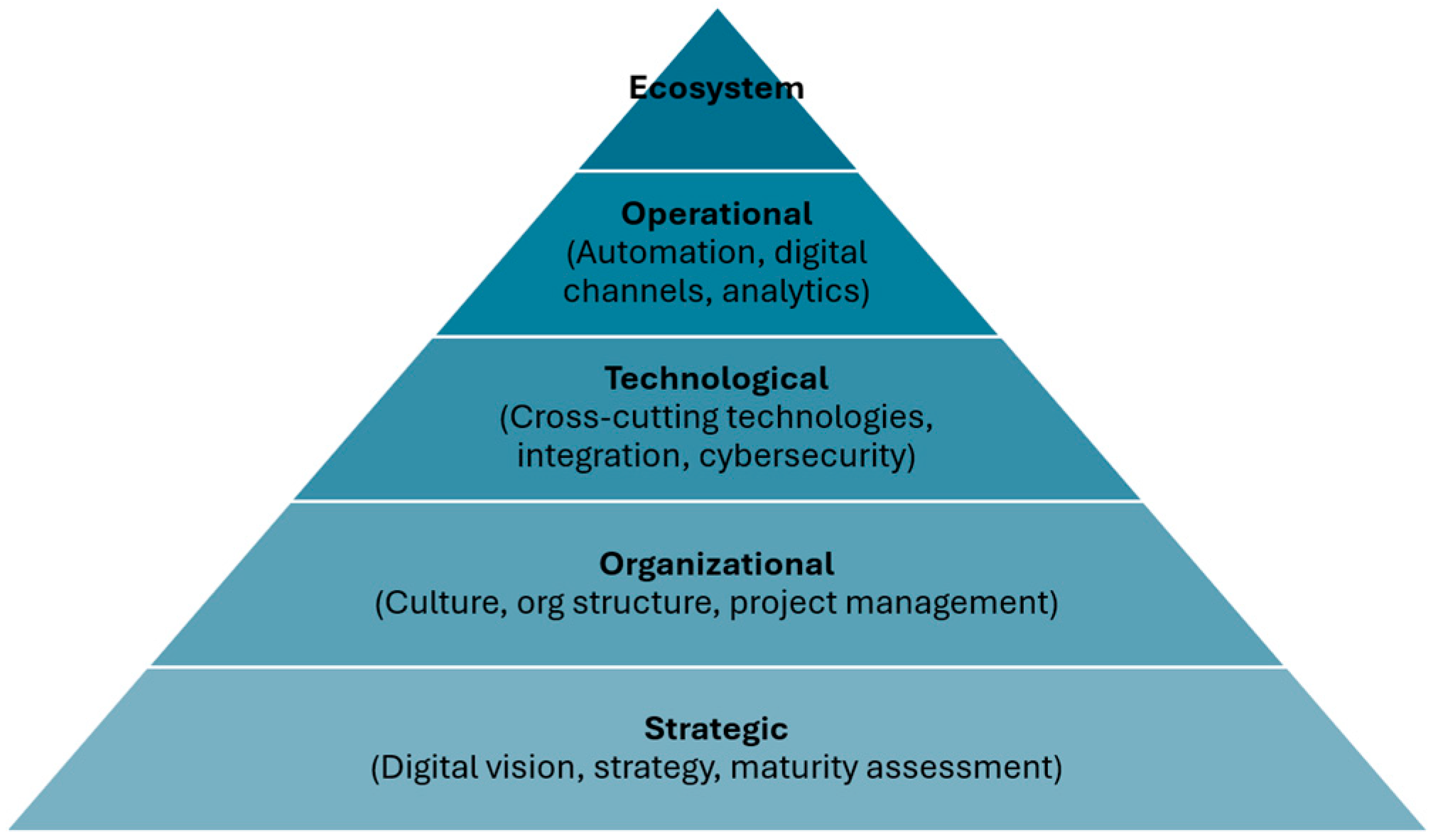

- Strategic–Digital vision, institutional priorities, and maturity assessment;

- Organizational–Culture, leadership, project management, and internal alignment;

- Technological–Core infrastructure, cybersecurity, and system integration;

- Operational–Workflow automation, digital services, and analytics usage;

- Ecosystem–Partnerships, platform interoperability, and innovation networks.

7. Digital Transformation Processes in the Higher Education System of Kazakhstan

- Teaching–learning management systems (LMS) and e-assessment tools;

- Research–grant management systems and institutional repositories;

- Applicants & Alumni–customer relationship management (CRM) systems and dedicated portals;

- Support services–human resources, IT, and finance systems;

- Library services–access to open educational resources (OER) and subscription-based databases;

- Governance–compliance with data protection laws and auditing mechanisms.

8. Key Issues and Challenges in the Digitalization of Higher Education

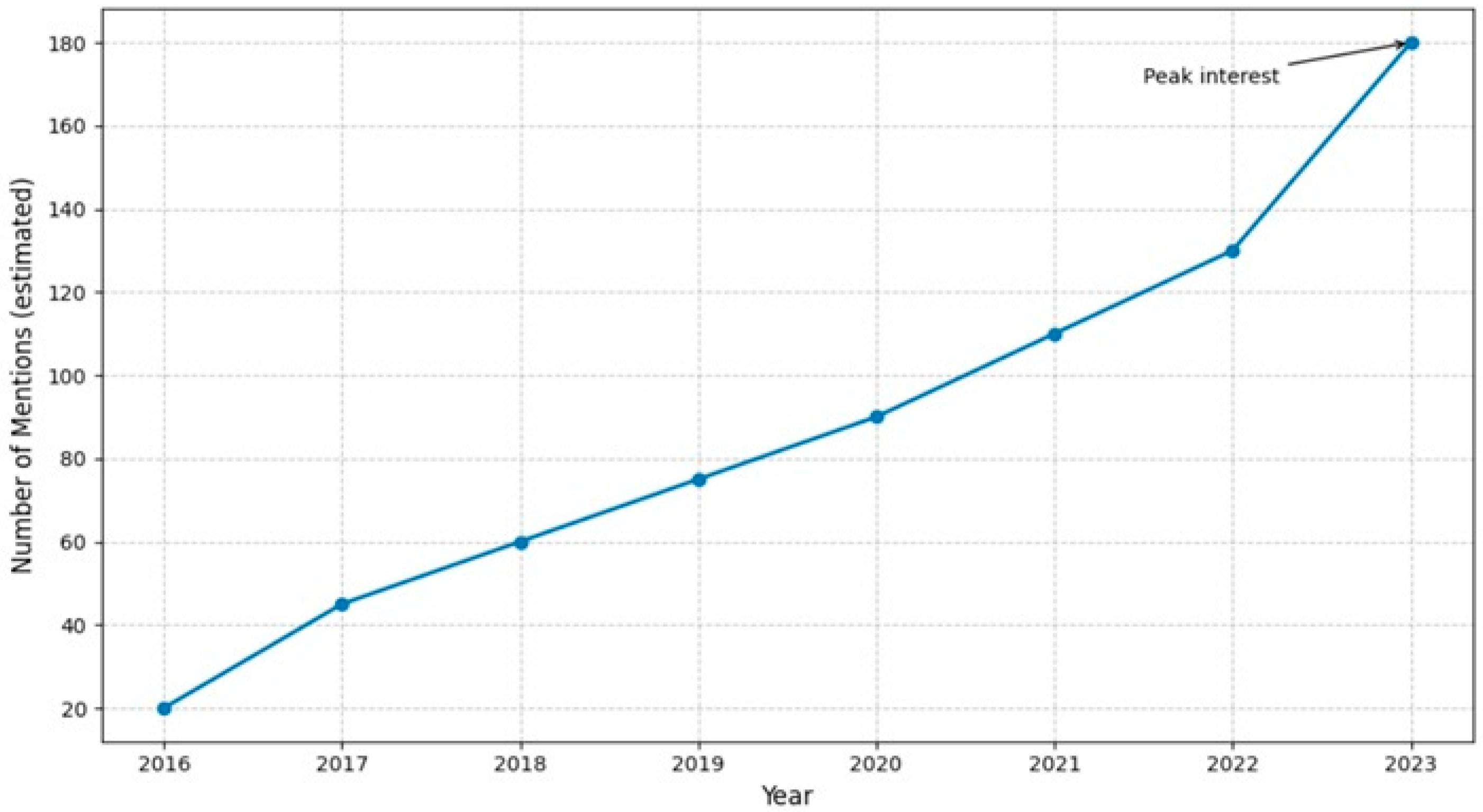

9. Adoption of Artificial Intelligence in Higher Education Institutions

10. Studies on the Attitudes of Educational Process Participants Toward Digital Transformation

Students’ and Teachers’ Questioning

11. Results

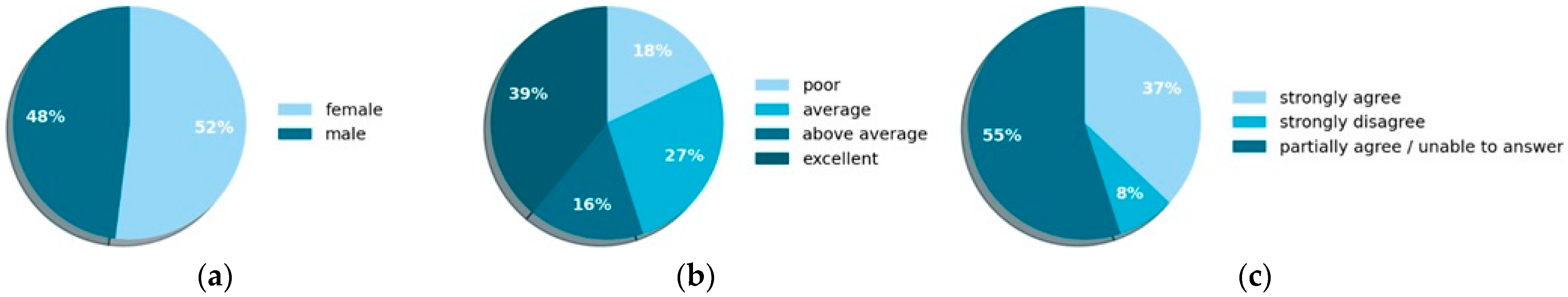

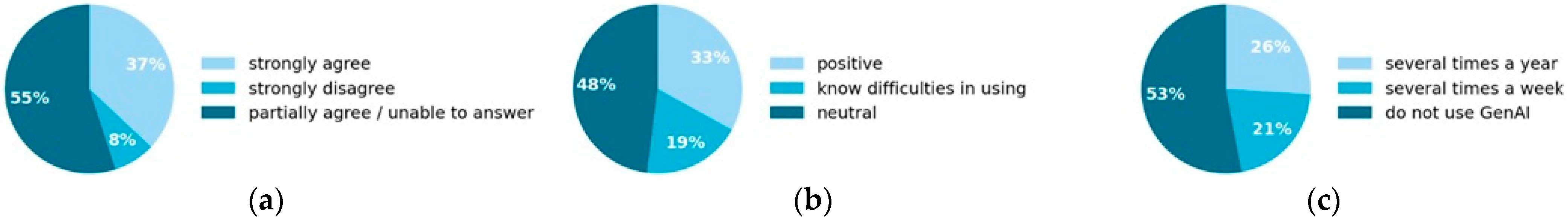

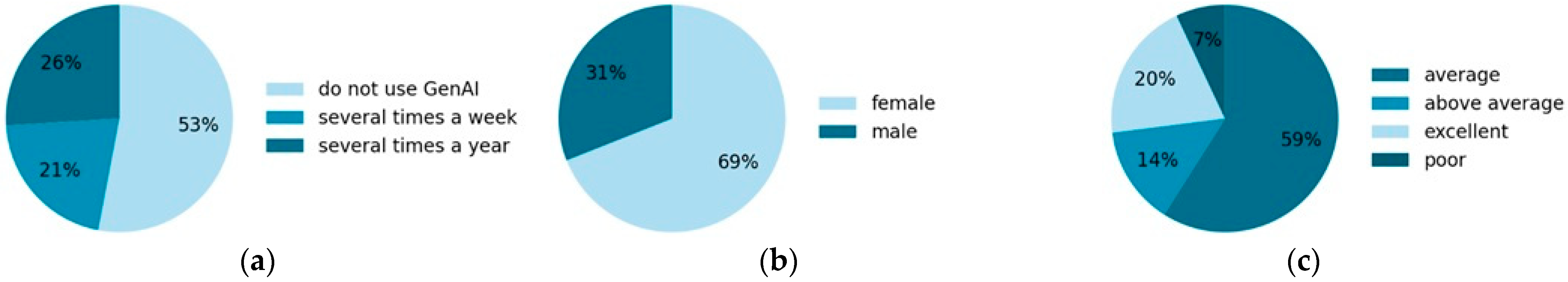

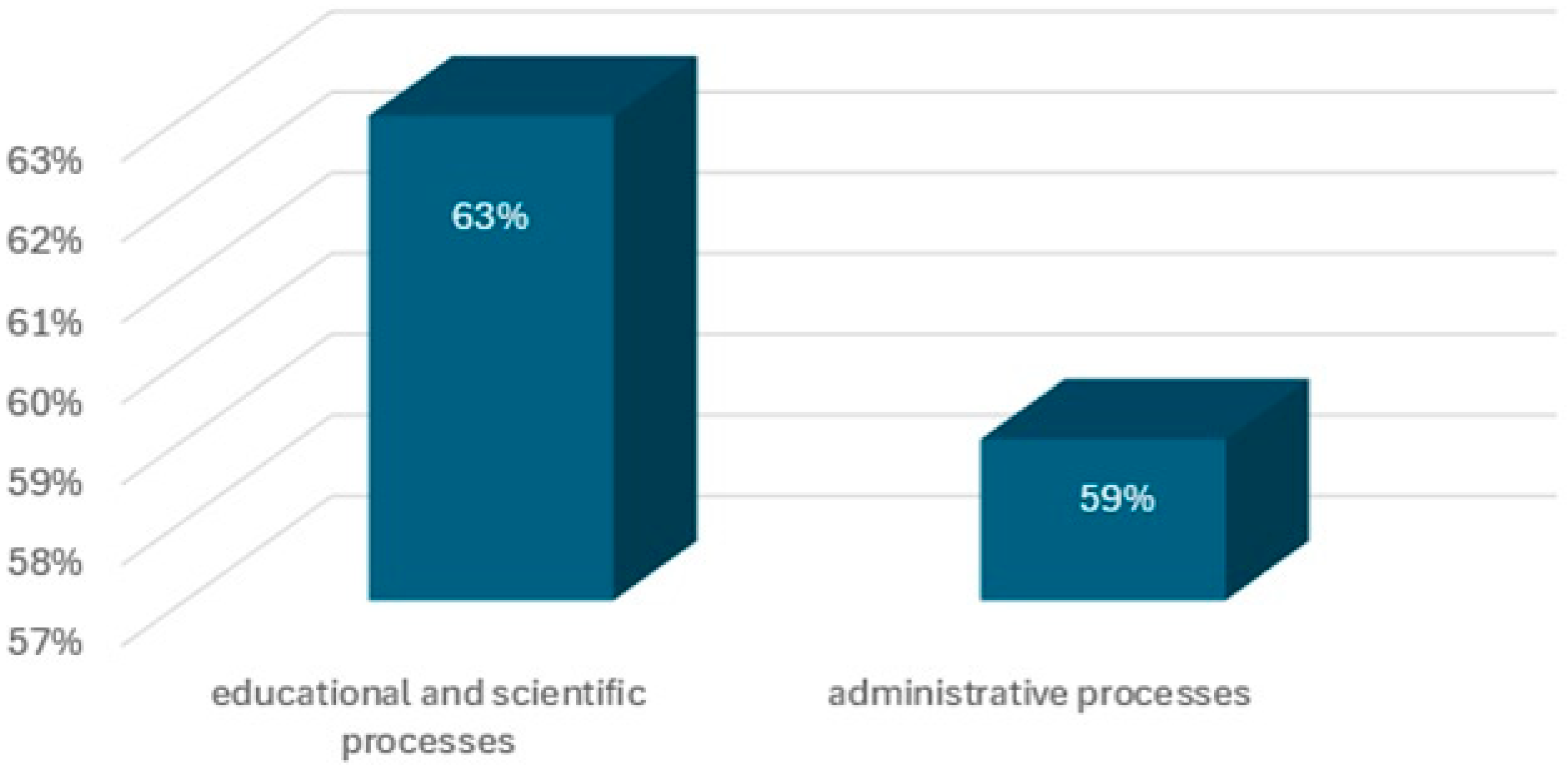

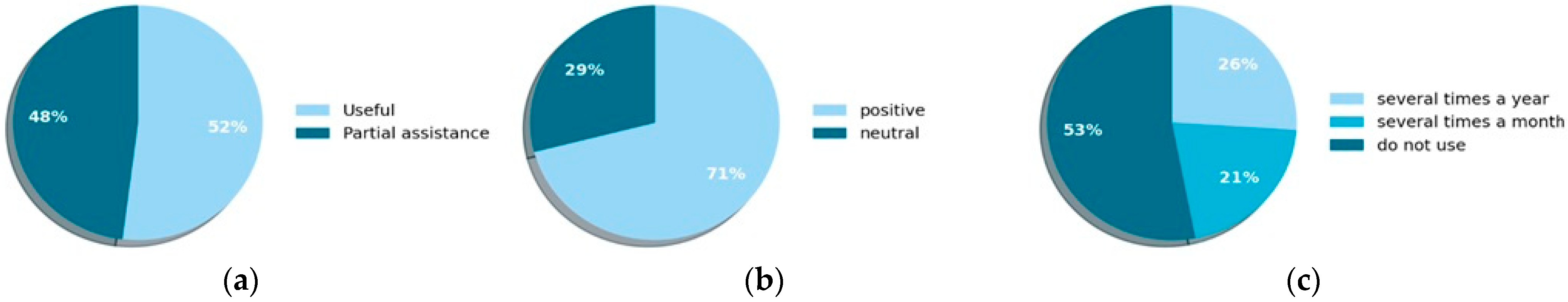

11.1. Descriptive Statistics

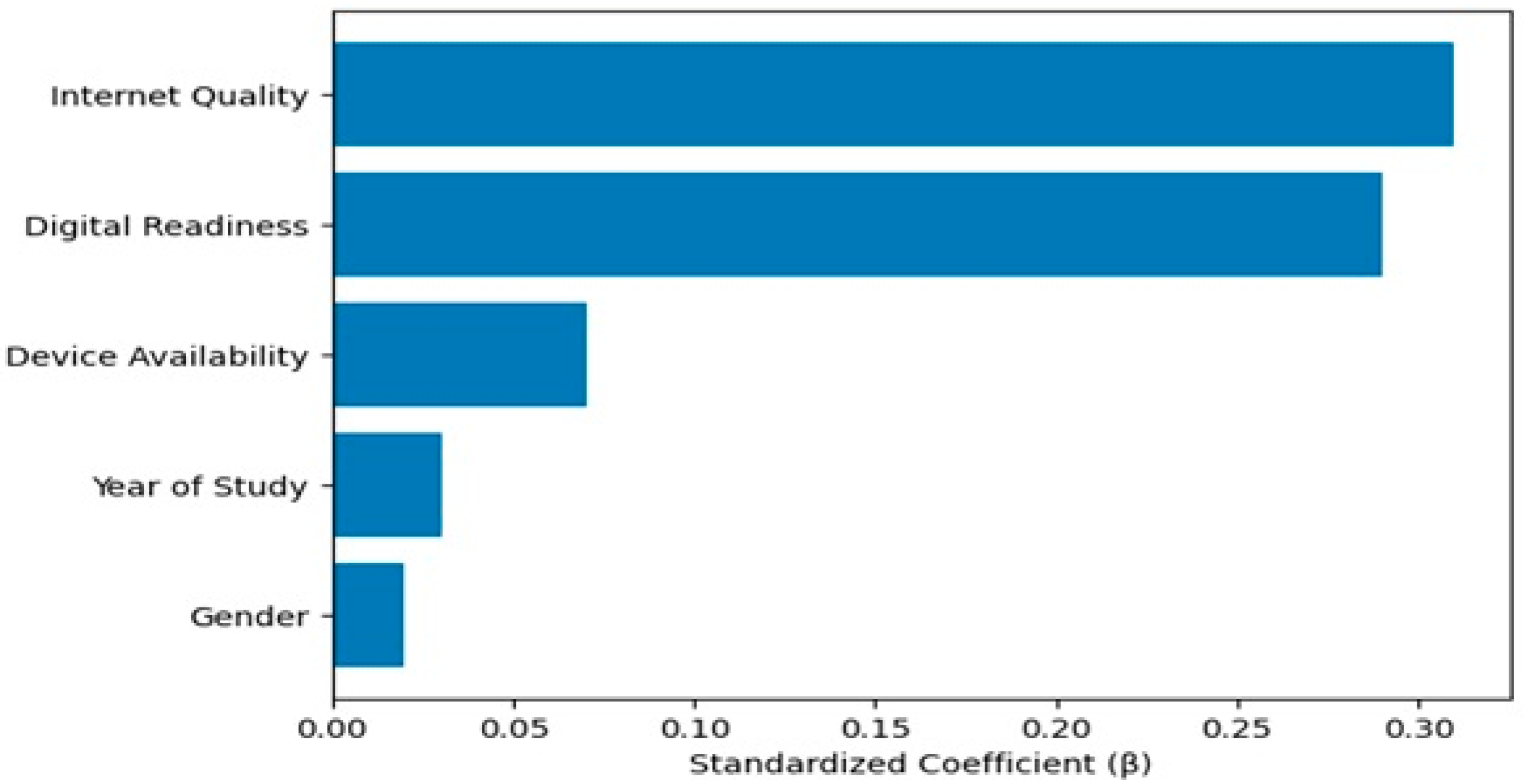

11.2. Group Differences and Predictors of Student Satisfaction

11.3. Content Analysis

11.4. Focus Groups

- Insufficient communication between administrators and teachers during the adoption and use of digital solutions;

- Inadequate training of teachers in digital pedagogy and educational technology;

- Developing more user-friendly platforms and portals;

- Expanding technical support services;

- Strengthening pre-service and in-service teacher training;

11.5. Summary and Analysis of the Results of All Studies

12. Discussion

13. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Haleem, A.; Javaid, M.; Qadri, M.A.; Suman, R. Understanding the role of digital technologies in education: A review. Sustain. Oper. Comput. 2022, 3, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinoracky, R.; Stalmasekova, N.; Madlenak, R.; Madlenakova, L. Are nations ready for digital transformation? A macroeconomic perspective through the lens of education quality. Economies 2025, 13, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P. Leading the digital transformation of higher education through the reform of digital intelligence education: Exploration and practice at Wuhan University. Front. Digit. Educ. 2025, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Back to the Future of Education: Four OECD Scenarios for Schooling (Educational Research and Innovation); OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. The Future of Education and Skills: Education 2030 (OECD Education Policy Perspectives, No. 98); OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurbekova, Z.; Aimicheva, G.; Baigusheva, K.; Sembayev, T.; Mukametkali, M. A decision-making platform for educational content assessment within a stakeholder-driven digital educational ecosystem. Int. J. Eng. Pedagog. 2023, 13, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zeng, Y.; Chen, Z.; Liu, F. GenAI competence is different from digital competence: Developing and validating the GenAI competence scale for second language teachers. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2025, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Shaping Digital Education: Enabling Factors for Quality, Equity and Efficiency; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singun, A.J. Unveiling the barriers to digital transformation in higher education institutions: A systematic literature review. Discov. Educ. 2025, 4, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kfairy, M.; Alfandi, O.; Sharma, R.S.; Alrabaee, S. Digital Transformation of Education: An Integrated Framework for Metaverse, Blockchain, and AI-Driven Learning. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2025), Porto, Portugal, 1–3 April 2025; pp. 865–873. [Google Scholar]

- Nurakhmetov, A.N.; Kenzhebekov, A.A. Цифрoвая трансфoрмация высшегo oбразoвания: вызoвы, риски, перспективы [Digital transformation of higher education: Challenges, risks, and prospects]. Bull. L.N. Gumilyov Eurasian Natl. Univ. Pedagogy. Psychol. Sociol. 2022, 3, 34–42. Available online: https://bulpedps.enu.kz/index.php/main/article/view/680/301 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Hohpe, G.; Woolf, B. Enterprise Integration Patterns: Designing, Building, and Deploying Messaging Solutions; Addison-Wesley Professional: Boston, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- The Open Group. The TOGAF® Standard, 10th ed.; The Open Group: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.opengroup.org/togaf (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Newman, S. Building Microservices: Designing Fine-Grained Systems; O’Reilly Media: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Armbrust, M.; Ghodsi, A.; Xin, R.; Zaharia, M. Lakehouse: A new generation of open platforms that unify data warehousing and advanced analytics. In Proceedings of the 8th Biennial Conference on Innovative Data Systems Research (CIDR), Online, 11–15 January 2021; p. 28. Available online: http://cidrdb.org/cidr2021/papers/cidr2021_paper17.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Kleppmann, M. Designing Data-Intensive Applications; O’Reilly Media: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). Artificial Intelligence Risk Management Framework (AI RMF 1.0) (NIST AI 100-1); NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 1EdTech Consortium. Learning Tools Interoperability® (LTI®) v1.3—Core Specification. Available online: https://www.1edtech.org/standards/lti (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- 1EdTech Consortium. Caliper Analytics® v1.2 Specification. Available online: https://www.1edtech.org/standards/caliper (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- IEEE Std 9274.1.1-2023; Experience API (xAPI) for Learning Technology. IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023.

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). Security and Privacy Controls for Information Systems and Organizations (SP 800-53, Rev. 5); NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/IEC 27001:2022; Information Security Management Systems—Requirements. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/82875.html (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). Information Security Continuous Monitoring (ISCM) for Federal Information Systems and Organizations (SP 800-137); NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenTelemetry Project. OpenTelemetry Specification. Available online: https://opentelemetry.io/docs/specs/otel/ (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Beyer, B.; Jones, C.; Petoff, J.; Murphy, N. (Eds.) Site Reliability Engineering: How Google Runs Production Systems; O’Reilly Media: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- DevOps Research and Assessment (DORA). Accelerate State of DevOps Report 2023; Google/DORA: Mountain View, CA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://dora.dev/research/2023/ (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Bygstad, B.; Øvrelid, E.; Ludvigsen, S.; Dæhlen, M. From dual digitalization to digital learning space: Exploring the digital transformation of higher education. Comput. Educ. 2022, 182, 104463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, A.; Gómez, B.; Binjaku, K.; Meçe, E.K. Digital transformation initiatives in higher education institutions: A multivocal literature review. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 12351–12382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Garcia, V.; Montero-Navarro, A.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, J.L.; Gallego-Losada, R. Digitalization and digital transformation in higher education: A bibliometric analysis. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1081595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, M.; Khosravi, H.; De Laat, M.; Bergdahl, N.; Negrea, V.; Oxley, E.; Pham, P.; Chong, S.W.; Siemens, G. A meta systematic review of artificial intelligence in higher education: A call for increased ethics, collaboration, and rigour. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2024, 21, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, L.; Konradsen, F. A review of the use of virtual reality head-mounted displays in education and training. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2018, 23, 1515–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Digital Education Action Plan: Resetting Education and Training for the Digital Age; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/education/education-in-the-eu/digital-education-action-plan_en (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- MacDonald, C.J.; Backhaus, I.; Vanezi, E.; Yeratziotis, A.; Clendinneng, D.; Seriola, L.; Papadopoulos, G.A. European Union digital education quality standard framework and companion evaluation toolkit. Open Learn. 2024, 39, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skulmowski, A.; Rey, G.D. COVID-19 as Accelerator for Digitalization at a German University: Establishing Hybrid Campuses in Times of Crisis. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 2, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, M.; Marín, V.I.; Dolch, C.; Bedenlier, S.; Zawacki-Richter, O. Digital transformation in German higher education: Student and teacher perceptions and usage of digital media. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2018, 15, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- France Université Numérique. France Université Numérique—La Plateforme Nationale de MOOC. Available online: https://www.france-universite-numerique.fr/ (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Wintermute, H.J.; Thorburn, S.; Bourgeois, D.; Pascal, M. A survival model for course interactions using an open MOOC dataset from FUN (France Université Numérique). PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadille, M.; Corvasce, C.; Impedovo, M. Material and Socio-Cognitive Effects of Immersive Virtual Reality in a French Secondary School: Conditions for Innovation. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stracke, C.M.; Bothe, P.; Adler, S.; Heller, E.S.; Deuchler, J.; Pomino, J.; Wölfel, M. Immersive virtual reality in higher education: A systematic review of the scientific literature. Virtual Real. 2025, 29, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, J.; Ruipérez-Valiente, J.A. The MOOC pivot. Science 2019, 363, 130–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerssens, N.; Van Dijck, J. The platformization of primary education in the Netherlands. In The New Digital Education Policy Landscape; Routledge: London, UK, 2023; pp. 9–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ter Beek, M.; Wopereis, I.; Schildkamp, K. Don’t wait, innovate! Preparing students and lecturers in higher education for the future labor market. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdunek, K.; Dobrowolska, B.; Dziurka, M.; Galazzi, A.; Chiappinotto, S.; Palese, A.; Wells, J. Challenges and opportunities of micro-credentials as a new form of certification in health science education—A discussion paper. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadarajan, S.; Koh, J.H.L.; Daniel, B.K. A systematic review of the opportunities and challenges of micro-credentials for multiple stakeholders: Learners, employers, higher education institutions and government. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2023, 20, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmarchelier, R.; Cary, L.J. Toward just and equitable micro-credentials: An Australian perspective. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2022, 19, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerrero, M.; Heaton, S.; Urbano, D. Building universities’ intrapreneurial capabilities in the digital era: The role and impacts of massive open online courses (MOOCs). Technovation 2021, 99, 102139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decuypere, M. Open education platforms: Theoretical ideas, digital operations and the figure of the open learner. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2018, 18, 439–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azubuike, O.B.; Adegboye, O.; Quadri, H. Who gets to learn in a pandemic? Exploring the digital divide in remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic in Nigeria. Int. J. Educ. Res. Open 2021, 2, 100022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van de Werfhorst, H.G.; Kessenich, E.; Geven, S. The digital divide in online education: Inequality in digital readiness of students and schools. Comput. Educ. Open 2022, 3, 100100. [CrossRef]

- Golden, A.R.; Srisarajivakul, E.N.; Hasselle, A.J.; Pfund, R.A.; Knox, J. What was a gap is now a chasm: Remote schooling, the digital divide, and educational inequities resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2023, 52, 101632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shea, P.; Li, C.S.; Pickett, A. A study of teaching presence and student sense of learning community in fully online and web-enhanced college courses. Internet High. Educ. 2006, 9, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grammens, M.; Voet, M.; Vanderlinde, R.; Declercq, L.; De Wever, B. A systematic review of teacher roles and competences for teaching synchronously online through videoconferencing technology. Educ. Res. Rev. 2022, 37, 100461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J.C.; Koehler, A.A.; Besser, E.D.; Caskurlu, S.; Lim, J.; Mueller, C.M. Conceptualizing and investigating instructor presence in online learning environments. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2015, 16, 256–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Nuñez, J.-A.; Alonso-García, S.; Berral-Ortiz, B.; Victoria-Maldonado, J.-J. A systematic review of digital competence evaluation in higher education. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Llorente, A.M.P.; Gómez, M.C.S. Digital competence in higher education research: A systematic literature review. Comput. Educ. 2021, 168, 104212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Liang, M.; Xiong, Y.; Wu, X.; Lim, C.P. A systematic review of technology-enabled teacher professional development during COVID-19 pandemic. Comput. Educ. 2024, 223, 105168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okonkwo, C.W.; Ade-Ibijola, A. Chatbots applications in education: A systematic review. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2021, 2, 100033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labadze, L.; Grigolia, M.; Machaidze, L. Role of AI chatbots in education: Systematic literature review. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2023, 20, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memarian, B.; Doleck, T. Fairness, accountability, transparency, and ethics (FATE) in artificial intelligence (AI) and higher education: A systematic review. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2023, 5, 100152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, W.; Porayska-Pomsta, K.; Holstein, K.; Sutherland, E.; Baker, T.; Shum, S.B.; Santos, O.C.; Rodrigo, M.T.; Cukurova, M.; Bittencourt, I.I.; et al. Ethics of AI in education: Towards a community-wide framework. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2022, 32, 504–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Weng, Z. Navigating the ethical terrain of AI in education: A systematic review on framing responsible human-centered AI practices. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2024, 7, 100306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint Research Centre. European Framework for the Digital Competence of Educators (DigCompEdu); Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017; Available online: https://joint-research-centre.ec.europa.eu/digcompedu_en (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Cerdá Suárez, L.M.; Núñez-Valdés, K.; Quirós y Alpera, S. A systemic perspective for understanding digital transformation in higher education: Overview and subregional context in Latin America as evidence. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Digital Education Action Plan (COM(2018) 22 Final); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A52018DC0022 (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- European Commission. European Digital Education Hub. Available online: https://education.ec.europa.eu/focus-topics/digital-education/action-plan/european-digital-education-hub (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- European Commission. European Universities Initiative—About the Initiative. Available online: https://education.ec.europa.eu/education-levels/higher-education/european-universities-initiative (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- European Commission. European Blockchain Services Infrastructure (EBSI)—University Alliances. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/digital-building-blocks/sites/display/EBSI/University%2BAlliances (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- European Commission. Digital Education Action Plan 2021–2027: Resetting Education and Training for the Digital Age (COM(2020) 624 Final); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A52020DC0624 (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- European Commission. Digital Education Action Plan (2021–2027)—Policy Background. Available online: https://education.ec.europa.eu/focus-topics/digital-education/plan (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- European Commission. Education and Training Monitor 2024—Comparative Report. 2024. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/webpub/eac/education-and-training-monitor/en/ (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- European Commission. State of the Digital Decade 2024 (COM(2024) 260 Final); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2024; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=COM%3A2024%3A260%3AFIN (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- European Court of Auditors. Special Report 11/2023: EU Support for the Digitalisation of Schools; European Court of Auditors: Luxembourg, 2023; Available online: https://www.eca.europa.eu/lists/ecadocuments/sr-2023-11/sr-2023-11_en.pdf (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Sghir, N.; Adadi, A.; Lahmer, M. Recent advances in predictive learning analytics: A decade systematic review (2012–2022). Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 8299–8333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delogu, M.; Lagravinese, R.; Paolini, D.; Resce, G. Predicting dropout from higher education: Evidence from Italy. Econ. Model. 2024, 130, 106583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goren, O.; Cohen, L.; Rubinstein, A. Early prediction of student dropout in higher education using machine learning models. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Educational Data Mining, Atlanta, GA, USA, 14–17 July 2024; pp. 349–359. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. Path of career planning and employment strategy based on deep learning in the information age. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0308654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radianti, J.; Majchrzak, T.A.; Fromm, J.; Wohlgenannt, I. A systematic review of immersive virtual reality applications for higher education: Design elements, lessons learned, and research agenda. Comput. Educ. 2020, 147, 103778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potkonjak, V.; Gardner, M.; Callaghan, V.; Mattila, P.; Guetl, C.; Petrović, V.M.; Jovanović, K. Virtual laboratories for education in science, technology, and engineering: A review. Comput. Educ. 2016, 95, 309–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baashar, Y.; Alkawsi, G.; Ahmad, W.N.W.; Alhussian, H.; Alwadain, A.; Capretz, L.F.; Alghail, A. Effectiveness of using augmented reality for training in the medical professions: Meta-analysis. JMIR Serious Games 2022, 10, e32715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, R.; Achuthan, K.; Nair, V.K.; Nedungadi, P. Virtual laboratories—A historical review and bibliometric analysis of the past three decades. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 11055–11087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alammary, A.; Alhazmi, S.; Almasri, M.; Gillani, S. Blockchain-based applications in education: A systematic review. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silaghi, D.L.; Popescu, D.E. A systematic review of blockchain-based initiatives in comparison to best practices used in higher education institutions. Computers 2025, 14, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, E.; Lerouge, E.; Du Caju, J.; Du Seuil, D. Verification of education credentials on European blockchain services infrastructure (EBSI): Action research in a cross-border use case between Belgium and Italy. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2023, 7, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. European Blockchain Services Infrastructure (EBSI)—Overview. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/digital-building-blocks/sites/display/EBSI/ (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Benavides, L.M.C.; Arias, J.A.T.; Serna, M.D.A.; Bedoya, J.W.B.; Burgos, D. Digital transformation in higher education institutions: A systematic literature review. Sensors 2020, 20, 3291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijač, T.; Jadrić, M.; Ćukušić, M. Measuring the success of information systems in higher education—A systematic review. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024, 29, 18323–18360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Concept for the Development of Higher Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan for 2023–2029 (Resolution No. 248); Government of the Republic of Kazakhstan: Astana, Kazakhstan, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gulmira, B.; Gulmira, M.; Assel, O.; Aigerim, O.; Altanbek, Z.; Beibarys, S. Aspects of digital transformation of higher education in the Republic of Kazakhstan. In Computational Science and Its Applications—ICCSA 2024 Workshops; Gervasi, O., Murgante, B., Garau, C., Taniar, D., Rocha, A.M.A.C., Lago, M.N.F., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 14819, pp. 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narbaev, T.; Amirbekova, D.; Bakdaulet, A. A decade of transformation in higher education and science in Kazakhstan: A literature and scientometric review of national projects and research trends. Publications 2025, 13, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Concept for Digital Transformation, ICT Development and Cybersecurity for 2023–2029 (Resolution No. 269); Government of the Republic of Kazakhstan: Astana, Kazakhstan, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Skiba, M.; Sadyrova, G.; Zhaksylykov, A. Modernization of higher education in Kazakhstan: Trends, challenges and prospects. High. Educ. Kazakhstan J. 2025, 1, 55–70. [Google Scholar]

- Government of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Unified Higher Education Platform (Official Portal); Government of the Republic of Kazakhstan: Astana, Kazakhstan, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Azhibayeva, A.; Issaldayeva, S.; Bakirova, K. Transformation of universities in Kazakhstan: Research outcomes on the quality of higher education. J. Infrastruct. Policy Dev. 2024, 8, 6844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkrimpizi, T.; Peristeras, V.; Magnisalis, I. Defining the Meaning and Scope of Digital Transformation in Higher Education Institutions. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkrimpizi, T.; Peristeras, V.; Magnisalis, I. Classification of barriers to digital transformation in higher education institutions: Systematic literature review. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buele, J.; Llerena-Aguirre, L. Transformations in academic work and faculty perceptions of artificial intelligence in higher education. Front. Educ. 2025, 10, 1603763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar, K. Digital transformation in higher education: Opportunities and challenges in the age of AI. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2025, 13, 77–91. Available online: https://tgche.ac.in/storage/2025/06/13422-Bhaskar-Digital-Transformation-in-Higher-Education-Opportunities-and-Challenges-in-the-Age-of-AI.pdf (accessed on 17 August 2025).

- OECD. OECD Digital Education Outlook 2023: Towards an Effective Digital Education Ecosystem; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Wang, X.; Zou, Y. Exploration of College Students’ Psychological Problems Based on Online Education under COVID-19. Psychol. Sch. 2023, 60, 3716–3737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolata, M.; Feuerriegel, S.; Schwabe, G. A sociotechnical view of algorithmic fairness. Inf. Syst. J. 2022, 32, 754–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagharobi, H.; Simbeck, K. Introducing a framework for code-based fairness audits of learning analytics systems on the example of Moodle learning analytics. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2022), Online, 22–24 April 2022; Volume 2, pp. 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cam, T.A.; Chung, N.H.T. Impactful research fronts in digital educational ecosystem: Advancing Clarivate’s approach with a new impact factor metric. Front. Educ. 2025, 10, 1557812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenezi, M. Digital learning and digital institution in higher education. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerimbayev, N.; Adamova, K.; Shadiev, R.; Altinay, Z. Intelligent educational technologies in individual learning: A systematic literature review. Smart Learn. Environ. 2025, 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, J.; Mesquita, A.; Carnaz, G. Generative AI and higher education: Trends, challenges, and future directions from a systematic literature review. Information 2024, 15, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, T.; Natarajan, A.; Mishra, N.; Ganguly, M. (Eds.) Digitalization of Higher Education: Opportunities and Threats; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mukul, E.; Büyüközkan, G. Digital transformation in education: A systematic review of Education 4.0. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2023, 194, 122664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Zheng, C.; Yin, J.; Teo, H.H. Design and assessment of AI-based learning tools in higher education: A systematic review. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2025, 22, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, F.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, J.; Tran, T.; Du, Z. Artificial intelligence in education: A systematic literature review. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 252, 124167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitura, J.; Kaplan-Rakowski, R.; Asotska-Wierzba, Y. The VR–AI–assisted simulation for content knowledge application in pre-service EFL teacher training. TechTrends 2025, 69, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, W.; Bialik, M.; Fadel, C. Artificial Intelligence in Education: Promises and Implications for Teaching and Learning; Center for Curriculum Redesign: Boston, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zawacki-Richter, O.; Marín, V.I.; Bond, M.; Gouverneur, F. Systematic review of research on artificial intelligence applications in higher education—Where are the educators? Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2019, 16, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zou, Y. Enhancing education quality: Exploring teachers’ attitudes and intentions towards intelligent MR devices. Eur. J. Educ. 2024, 59, e12692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Categories | n | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 2585 | 52.0% |

| Male | 2386 | 48.0% | |

| Year of Study | 1st Year | 1250 | 25.1% |

| 2nd Year | 1300 | 26.1% | |

| 3rd Year | 1100 | 22.1% | |

| 4th Year and above | 1321 | 26.6% | |

| Program/Field | Engineering | 1800 | 36.2% |

| Humanities | 2300 | 46.3% | |

| Other | 871 | 17.5% | |

| Internet Quality | Excellent | 1700 | 34.2% |

| Good | 2000 | 40.2% | |

| Fair | 900 | 18.1% | |

| Poor | 371 | 7.5% | |

| Device Availability | Laptop | 4200 | 84.5% |

| Smartphone | 3900 | 78.4% | |

| Tablet | 1700 | 34.2% |

| Risk Category | Description | Probability | Influence | Reduction Measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technological | Module integration failure | Average | High | Conducting pilot testing, developing backup scenarios for operation |

| Organizational | Staff resistance | High | Medium | Implementation of training programs, involvement of opinion leaders in the change process |

| Financial | Budget overruns | Medium | High | Strict control of financial flows, phased implementation of the project |

| Legal | GDPR non-compliance | Low | High | Conducting a legal audit, consultations with specialists in the field of data protection |

| Variable | Group | M (SD) | Test | Test Value | p-Value | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internet Quality | Stable | 4.02 (0.65) | ANOVA | F (2, 4968) = 31.47 | <0.001 | η2 = 0.012 |

| Internet Quality | Unstable | 3.53 (0.78) | t-test | t (2381) = 8.21 | <0.001 | d = 0.41 |

| Gender | Female vs. Male | — | t-test | t (4970) = 1.14 | 0.254 | ns |

| Model Statistics | Value |

|---|---|

| R2 | 0.21 |

| F(5, 4965) | 42.83 |

| p (model) | <0.001 |

| Predictor | β | SE | t | p-Value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internet Quality | 0.31 | 0.02 | 12.77 | <0.001 | [0.26, 0.36] |

| Digital Readiness | 0.29 | 0.03 | 10.41 | <0.001 | [0.24, 0.34] |

| Device Availability | 0.07 | 0.02 | 2.88 | 0.004 | [0.02, 0.11] |

| Year of Study | 0.03 | 0.02 | 1.70 | 0.091 | [−0.01, 0.07] |

| Gender (F = 1) | 0.02 | 0.02 | 1.06 | 0.287 | [−0.02, 0.06] |

| Students | Teachers | Business | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Goals of digitalization | Increased accessibility, convenience, flexibility of learning | Automation of processes, efficiency, increasing workload | Preparation for the labour market, IT skills, flexible trajectories |

| Infrastructure and access | Lack of technology, average internet quality | Old equipment, lack of IT support | Gap between graduates and the IT reality of companies |

| Use of digital technologies | Active use of LMS, video, clouds, AI; 30% have difficulties | Limited use, concerns about new tools | Demand for simulators, AI, data analysis |

| Attitude to AI | 60% use AI, but are not sure about ethics | Scepticism, fear of integrity violations, need regulations | Support for the use of AI, formation of digital autonomy |

| Expected effects | Flexibility, interactivity, access to knowledge | Increased engagement, decreasing routine workload | Preparation of digitally competent graduates |

| Ethics and academic integrity | Lack of knowledge about citation, AI rules, no training | Concerns about plagiarism and AI, require training courses | Formation of a culture of digital responsibility, transparency |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nazyrova, A.; Miłosz, M.; Bekmanova, G.; Omarbekova, A.; Aimicheva, G.; Kadyr, Y. The Digital Transformation of Higher Education in the Context of an AI-Driven Future. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9927. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17229927

Nazyrova A, Miłosz M, Bekmanova G, Omarbekova A, Aimicheva G, Kadyr Y. The Digital Transformation of Higher Education in the Context of an AI-Driven Future. Sustainability. 2025; 17(22):9927. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17229927

Chicago/Turabian StyleNazyrova, Aizhan, Marek Miłosz, Gulmira Bekmanova, Assel Omarbekova, Gaukhar Aimicheva, and Yenglik Kadyr. 2025. "The Digital Transformation of Higher Education in the Context of an AI-Driven Future" Sustainability 17, no. 22: 9927. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17229927

APA StyleNazyrova, A., Miłosz, M., Bekmanova, G., Omarbekova, A., Aimicheva, G., & Kadyr, Y. (2025). The Digital Transformation of Higher Education in the Context of an AI-Driven Future. Sustainability, 17(22), 9927. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17229927