Navigating Power Dynamics in Sustainability Transformation: Extending Integration Mechanisms Across Organizational Boundaries

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How do organizations address power asymmetries in supply chains and partnerships to advance sustainability transformation?

- What specific mechanisms enable organizations to manage power dynamics across organizational boundaries?

- How do digital technologies function as tools for reconfiguring power relationships in sustainability contexts?

2. Theoretical Background

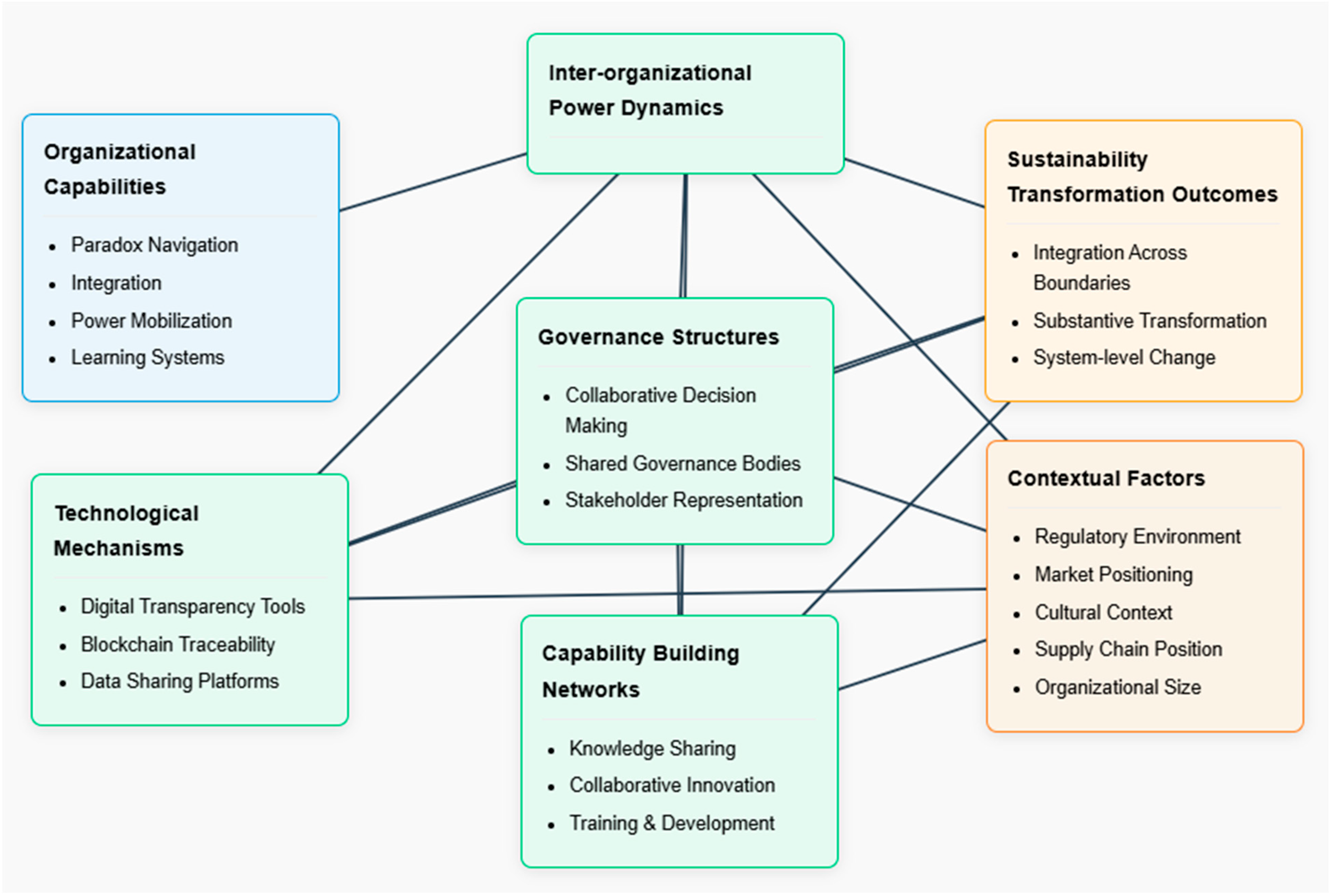

2.1. Power Dynamics in Sustainability Transformation

2.2. Inter-Organizational Power in Supply Chains and Partnerships

2.3. Digital Technologies and Power Reconfiguration

2.4. Conceptual Framework and Research Hypotheses

3. Methods

3.1. Research Design

- Quantitative phase: Survey of sustainability professionals (n = 127) across multiple sectors to test relationships between inter-organizational power mechanisms, integration practices, and transformation outcomes

- Qualitative phase: In-depth interviews with transformation leaders (n = 18) to develop deeper understanding of the mechanisms and contexts through which organizations address power dynamics

3.2. Sampling and Participants

3.2.1. Survey Sample

- The final sample included 127 sustainability professionals with the following characteristics:

- Sectors: Manufacturing (31%), Services (27%), Consumer Products (22%), Technology (12%), Other (8%)

- Organizational size: Large (>5000 employees, 42%), Medium (500–5000 employees, 35%), Small (<500 employees, 23%)

- Geographic regions: North America (37%), Europe (33%), Asia (21%), Other (9%)

- Roles: Sustainability Directors/Managers (48%), Supply Chain/Procurement Managers (22%), Executive Leadership (18%), Other (12%)

- Supply chain position: Focal firms (57%), Tier 1 suppliers (24%), Tier 2+ suppliers (19%)

3.2.2. Interview Sample

- Interview participants were selected using purposive sampling to capture diverse experiences with inter-organizational power dynamics in sustainability contexts. Selection criteria included:

- Direct experience with inter-organizational sustainability initiatives.

- Representation of both powerful and less powerful positions in supply chains/partnerships.

- Experience with digital technologies in sustainability contexts.

- Sector and geographic diversity.

- 6 sustainability directors/managers from focal firms.

- 4 supply chain managers from focal firms.

- 5 sustainability/operations managers from supplier firms.

- 3 leaders of multi-stakeholder sustainability initiatives.

3.3. Research Instruments

3.3.1. Survey Instrument

- Scale development for newly created measures followed a rigorous process following De Vellis’ (2016) [25] scale development guidelines:

- Initial item generation based on literature and expert input.

- Content validity assessment by a panel of five academic and practitioner experts.

- Pilot testing with 25 sustainability professionals.

- Exploratory factor analysis to refine item sets.

- Confirmatory factor analysis to validate final scales.

3.3.2. Semi-Structured Interviews

- Semi-structured interviews lasting 60–90 min were conducted with 18 participants between April and June 2023. The interview protocol addressed:

- Experiences with power dynamics in inter-organizational sustainability initiatives.

- Strategies for navigating and addressing power relationships with external stakeholders.

- Use of digital technologies in inter-organizational sustainability contexts.

- Barriers and enablers for collaborative approaches to sustainability.

- Evolution of inter-organizational relationships through sustainability initiatives.

3.4. Data Analysis

3.4.1. Quantitative Analysis

- Measurement validation: Confirmatory factor analysis to assess convergent and discriminant validity of constructs.

- Structural model testing: Examination of hypothesized relationships between constructs.

- Multigroup analysis: Comparison of path coefficients across sectors, organizational sizes, and supply chain positions to test for contextual differences.

3.4.2. Qualitative Analysis

- Familiarization with the data through repeated reading.

- Generation of initial codes using a hybrid approach combining deductive codes from the conceptual framework and inductive codes emerging from the data.

- Searching for themes by organizing codes into potential themes.

- Reviewing themes in relation to coded extracts and the entire dataset.

- Defining and naming themes with clear descriptions.

- Producing the report with representative quotes and analysis.

3.4.3. Integration of Quantitative and Qualitative Findings

3.5. Research Quality and Ethics

- Construct validity was established through validated scales and expert review of survey items.

- External validity was supported by including a diverse sample across sectors, organizational sizes, and geographic regions.

- Reliability was enhanced through detailed documentation of research procedures and analysis decisions.

4. Results

4.1. Quantitative Findings: Structural Model and Hypothesis Testing

- The association between digital transparency mechanisms and integration was significantly stronger for suppliers (β = 0.53) than focal firms (β = 0.29), with a difference of 0.24 (p < 0.001).

- The association between capability building networks and integration was significantly stronger for suppliers (β = 0.44) than focal firms (β = 0.31), with a difference of 0.13 (p = 0.038).

- The association between collaborative governance structures and integration was significantly stronger in service sectors (β = 0.41) than manufacturing (β = 0.28), with a difference of 0.13 (p = 0.038).

4.2. Qualitative Findings: Mechanisms and Contextual Dynamics

4.2.1. Technological Transparency Mechanisms

- Collaborative design processes that involve less powerful actors in system development.

- Bidirectional transparency that makes information visible to all participants rather than only to powerful actors.

- Shared value creation that ensures benefits flow to all participants in the system.

4.2.2. Collaborative Governance Structures

- Formal representation of diverse stakeholders, particularly those traditionally excluded from decision-making.

- Clear decision rights and processes that ensure representation translates into genuine influence.

- Resource support that enables less-resourced stakeholders to participate effectively.

4.2.3. Capability Building Networks

- Knowledge democratization that makes sustainability expertise accessible to less-resourced organizations.

- Innovation support that enables smaller organizations to develop and scale sustainability solutions.

- Relationship building that creates social capital across traditional power boundaries.

4.3. Contextual Contingencies and Integration

4.3.1. Regulatory Context

4.3.2. Market Positioning

4.3.3. Cultural Context

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Alternative Explanations

5.3. Practical Implications

- Assessment stage: Analyze existing power dynamics and contextual factors to identify appropriate intervention points.

- Foundation stage: Implement digital transparency initiatives with collaborative design to create shared understanding.

- Governance stage: Establish formal collaborative governance structures with representation of diverse stakeholders.

- Capability stage: Develop shared capability building networks that distribute expertise more equitably.

- System stage: Scale successful approaches to influence broader system dynamics beyond immediate relationships.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

- Longitudinal studies of how inter-organizational power dynamics evolve over time through sustainability initiatives, identifying critical junctures and intervention points. Future research should test the proposition that power relationships in sustainability contexts follow an evolutionary pathway from compliance-based to collaborative approaches through specific transitional mechanisms.

- Comparative studies of digital transparency initiatives across diverse contexts to develop more nuanced understanding of how technological design choices affect power outcomes. Future research should examine how specific design features influence power distribution in digital sustainability platforms.

- Multi-level analyses connecting organizational, inter-organizational, and system-level power dynamics to develop more comprehensive models of power in sustainability transformations. This research should test the proposition that successful system-level sustainability transitions require coherent power reconfiguration across multiple levels rather than isolated changes at specific levels.

- Action research approaches that actively engage with organizations in designing, implementing, and evaluating power-conscious approaches to sustainability transformation. This engaged research approach would provide deeper insights into the practical challenges of addressing power dynamics while simultaneously contributing to meaningful change.

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Survey Instrument

- INTER-ORGANIZATIONAL POWER DYNAMICS IN SUSTAINABILITY TRANSFORMATION

- SECTION 1: ORGANIZATIONAL CHARACTERISTICS

- Which sector best describes your organization?

- ○

- Manufacturing

- ○

- Services

- ○

- Consumer Products

- ○

- Technology

- ○

- Other (please specify): _______

- How many employees does your organization have globally?

- ○

- Less than 100

- ○

- 100–499

- ○

- 500–999

- ○

- 1000–4999

- ○

- 5000–9999

- ○

- 10,000 or more

- In which regions does your organization operate? (Select all that apply)

- ○

- North America

- ○

- Europe

- ○

- Asia

- ○

- South America

- ○

- Africa

- ○

- Australia/Oceania

- Which of the following best describes your organization’s position in the supply chain?

- ○

- Focal firm (brand owner, retailer, or other customer-facing organization)

- ○

- Tier 1 supplier (direct supplier to focal firms)

- ○

- Tier 2 or beyond supplier (supplier to other suppliers)

- ○

- Other (please specify): _______

- Which of the following best describes your role in the organization?

- ○

- Sustainability Director/Manager

- ○

- Supply Chain/Procurement Manager

- ○

- Operations Manager

- ○

- Executive Leadership (C-Suite, VP)

- ○

- Other (please specify): _______

- SECTION 2: INTER-ORGANIZATIONAL POWER MOBILIZATION

- Our organization builds coalitions with external stakeholders to advance sustainability initiatives.

- We strategically frame sustainability initiatives to align with partners’ priorities and interests.

- We leverage our market position to influence suppliers’ sustainability practices.

- Our organization creates shared narratives about sustainability that resonate with diverse stakeholders.

- We identify and work with champions in partner organizations to advance sustainability initiatives.

- Our organization negotiates sustainability standards and expectations with key partners rather than imposing them unilaterally.

- We acknowledge power imbalances with suppliers/partners and take steps to create more balanced relationships.

- Our sustainability team is skilled at mobilizing support across organizational boundaries.

- SECTION 3: DIGITAL TRANSPARENCY MECHANISMS

- Our organization uses digital platforms to create supply chain transparency.

- Digital tools help us make sustainability impacts visible to stakeholders.

- We use digital technologies to track and verify sustainability claims across our value chain.

- Our digital systems allow suppliers and partners to access information about their sustainability performance.

- Digital tools in our organization create two-way visibility (not just monitoring suppliers but also sharing information with them).

- We involve suppliers and partners in the design of digital transparency systems.

- Our digital systems help create shared understanding of sustainability challenges with external stakeholders.

- Digital transparency tools have changed power dynamics in our relationships with suppliers/partners.

- SECTION 4: COLLABORATIVE GOVERNANCE STRUCTURES

- Our organization has established shared decision-making processes with key partners.

- We have formal structures for collaborative problem-solving with external stakeholders.

- Sustainability governance includes representation from suppliers and other external stakeholders.

- Our organization ensures that less powerful stakeholders have meaningful voice in sustainability initiatives.

- We have clear procedures for resolving conflicts with external stakeholders in sustainability contexts.

- Our organization allocates resources to support participation of less-resourced stakeholders in governance processes.

- Decision-making authority in sustainability initiatives is distributed among partners rather than centralized.

- Our governance structures create accountability in both directions (not just suppliers to us, but also us to suppliers).

- SECTION 5: CAPABILITY BUILDING NETWORKS

- Our organization invests in building sustainability capabilities across our supply chain.

- We participate in knowledge-sharing networks with external partners.

- We provide resources to help suppliers develop sustainability capabilities.

- Our organization creates platforms for cross-organizational learning on sustainability.

- We engage in collaborative innovation with suppliers and partners to address sustainability challenges.

- Our organization values and incorporates knowledge from diverse stakeholders in sustainability initiatives.

- We recognize and leverage the unique sustainability capabilities of suppliers and partners.

- Our capability building initiatives have changed power dynamics with external stakeholders.

- SECTION 6: INTEGRATION ACROSS BOUNDARIES

- Sustainability considerations are integrated into supplier selection and management.

- Our sustainability strategy is developed collaboratively with key external stakeholders.

- Performance metrics track sustainability impacts across organizational boundaries.

- We have aligned sustainability goals with key suppliers and partners.

- Sustainability information flows effectively between our organization and external stakeholders.

- Our organization has integrated sustainability considerations into contracts and agreements with suppliers/partners.

- We have established shared problem-solving approaches for sustainability challenges with external stakeholders.

- Our approach to sustainability challenges systemically addresses cross-organizational issues.

- SECTION 7: TRANSFORMATION OUTCOMES

- Our sustainability initiatives have transformed relationships with suppliers and partners.

- We have achieved significant sustainability improvements across our value chain.

- Our organization has influenced sustainability practices beyond our direct operations.

- Our inter-organizational sustainability initiatives have created shared value for all participants.

- We have effectively addressed systemic sustainability challenges through cross-organizational collaboration.

- Our approach to sustainability has evolved from compliance-focused to collaboration-focused.

- Our sustainability initiatives have improved overall supply chain resilience.

- External stakeholders recognize our organization as a sustainability leader in our industry.

- SECTION 8: CONTEXTUAL FACTORS

- Our organization operates in a highly regulated environment for sustainability.

- External stakeholders exert significant pressure on our organization regarding sustainability.

- Our industry has established sustainability standards that shape inter-organizational relationships.

- Power is distributed relatively equally among key actors in our value chain.

- Our organization’s culture supports collaborative approaches to sustainability.

- Our organizational leadership actively supports power-sharing in sustainability initiatives.

- Our organization has sufficient resources to invest in cross-organizational sustainability initiatives.

- The geographic regions where we operate influence our approach to power dynamics in sustainability.

- SECTION 9: OPEN-ENDED QUESTIONS

- What are the most significant power-related challenges your organization faces in advancing sustainability across organizational boundaries?

- Can you describe a specific example where your organization successfully reshaped power dynamics with external stakeholders to advance sustainability?

- How have digital technologies specifically influenced power relationships with suppliers or partners in sustainability contexts?

- What do you see as the most promising approaches for creating more balanced power relationships in sustainability initiatives?

- SECTION 10: DEMOGRAPHIC INFORMATION

- How many years have you worked in your current organization?

- ○

- Less than 1 year

- ○

- 1–3 years

- ○

- 4–6 years

- ○

- 7–10 years

- ○

- More than 10 years

- How many years of experience do you have working on sustainability-related issues?

- ○

- Less than 1 year

- ○

- 1–3 years

- ○

- 4–6 years

- ○

- 7–10 years

- ○

- More than 10 years

- What is your gender?

- ○

- Female

- ○

- Male

- ○

- Non-binary/third gender

- ○

- Prefer not to say

- In which region are you primarily based?

- ○

- North America

- ○

- Europe

- ○

- Asia

- ○

- South America

- ○

- Africa

- ○

- Australia/Oceania

Appendix B. Interview Protocol

- INTER-ORGANIZATIONAL POWER DYNAMICS IN SUSTAINABILITY TRANSFORMATION

- In-Depth Interview Guide

- Introduction

- Thank participant for their time;

- Explain purpose of research: investigating how organizations navigate and reshape power dynamics across organizational boundaries in sustainability contexts;

- Review informed consent, confidentiality, and recording permissions;

- Clarify expected duration (60–90 min).

- Background Information

- Could you briefly describe your role and responsibilities related to sustainability in your organization?

- How long have you been working on sustainability-related initiatives, both in your current role and previously?

- Could you briefly describe your organization’s key sustainability priorities and how these connect to external stakeholders like suppliers, customers, or partners?

- Understanding Power Dynamics

- How would you describe the power dynamics between your organization and key external stakeholders (suppliers, partners, customers) in sustainability contexts?

- What specific power asymmetries or imbalances have you observed in sustainability initiatives that cross organizational boundaries?

- How do these power dynamics differ from those in conventional business relationships not focused on sustainability?

- In what ways do these power dynamics enable or constrain progress on sustainability initiatives?

- Digital Transparency Mechanisms

- How does your organization use digital technologies to create transparency in sustainability contexts?

- Could you describe a specific digital transparency initiative and how it was designed and implemented?

- How were external stakeholders involved in the design and implementation process?

- How has this digital transparency initiative affected relationships with external stakeholders?

- In what ways, if any, has this initiative shifted power dynamics with suppliers or partners?

- What factors determine whether digital tools function as power equalizers versus reinforcing existing power asymmetries?

- Collaborative Governance Structures

- What formal structures or processes has your organization established for collaborative decision-making with external stakeholders on sustainability issues?

- Could you describe a specific collaborative governance initiative and how it was developed?

- What challenges did you face in implementing more collaborative governance approaches?

- How do you ensure that less powerful stakeholders have meaningful voice in these governance processes?

- In what ways have these governance structures changed power relationships with external stakeholders?

- Capability Building Networks

- How does your organization approach capability building for sustainability across organizational boundaries?

- Could you describe a specific capability building initiative involving external stakeholders?

- How does your organization balance providing expertise versus learning from external stakeholders?

- In what ways has capability building changed power dynamics with suppliers or partners?

- How do capability building initiatives differ depending on the stakeholder’s relative power position?

- Evolution of Power Relationships

- How have your organization’s relationships with key external stakeholders evolved through sustainability initiatives?

- Could you describe a specific relationship that has transformed significantly through sustainability work?

- What were the key factors or interventions that enabled this transformation?

- How has your personal approach to navigating power dynamics in sustainability contexts evolved over time?

- Contextual Factors

- How do regulatory contexts influence your organization’s approach to power dynamics in sustainability initiatives?

- In what ways does your organization’s market positioning (brand visibility, consumer proximity) affect how you navigate power with external stakeholders?

- How do cultural contexts (national, organizational) shape your approaches to power in sustainability initiatives?

- How do approaches differ across different geographic regions where your organization operates?

- Challenges and Barriers

- What are the most significant barriers to creating more balanced power relationships in sustainability contexts?

- Can you describe a situation where efforts to reshape power dynamics were unsuccessful? What factors contributed to this outcome?

- What resistances have you encountered from within your own organization to more collaborative approaches with external stakeholders?

- What tensions exist between reshaping power dynamics and meeting short-term business objectives?

- Success Factors and Best Practices

- Based on your experience, what approaches have been most effective in reshaping power dynamics to enable more substantive sustainability transformation?

- What skills or capabilities are most important for sustainability professionals to develop in navigating power dynamics?

- What advice would you give to organizations seeking to create more balanced and collaborative relationships with external stakeholders?

- Closing Questions

- Is there anything important about power dynamics in sustainability contexts that we haven’t discussed that you’d like to share?

- Would you be willing to be contacted for any follow-up questions or clarifications?

- Do you have any questions for me about this research?

- Wrap-up

- Thank participant for their time and insights;

- Explain next steps in the research process;

- Offer to share summary of findings when available;

- Provide contact information for any additional thoughts or questions.

References

- Bansal, P.; Song, H.C. Similar but not the same: Differentiating corporate sustainability from corporate responsibility. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2017, 11, 105–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, G.; Merrill, R.K.; Schillebeeckx, S.J. Digital sustainability and entrepreneurship: How digital innovations are helping tackle climate change and sustainable development. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2021, 45, 999–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westover, J.H. Navigating paradox for sustainable futures: Organizational capabilities and integration mechanisms in sustainability transformation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huxham, C.; Vangen, S. Managing to Collaborate: The Theory and Practice of Collaborative Advantage; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Touboulic, A.; Chicksand, D.; Walker, H. Managing imbalanced supply chain relationships for sustainability: A power perspective. Decis. Sci. 2014, 45, 577–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.; Kennedy, S.; Philipp, F.; Whiteman, G. Systems thinking: A review of sustainability management research. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 148, 866–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touboulic, A.; Walker, H. Love me, love me not: A nuanced view on collaboration in sustainable supply chains. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2015, 21, 178–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lissillour, R.; Bonet Fernandez, D. Reframing sustainability learning through certification: A practice-perspective on supply chain management. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 17, 5761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestre, B.S.; Silva, M.E.; Cormack, A.; Thome, A.M.T. Supply chain sustainability trajectories: Learning through sustainability initiatives. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2020, 40, 1301–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, P.; Spicer, A. Power in management and organization science. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2014, 8, 237–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J.; Salancik, G.R. The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Hillman, A.J.; Withers, M.C.; Collins, B.J. Resource dependence theory: A review. J. Manag. 2009, 35, 1404–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W. Micro-foundations of the multi-level perspective on socio-technical transitions: Developing a multi-dimensional model of agency through crossovers between social constructivism, evolutionary economics and neo-institutional theory. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 152, 119894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, R.; Sulaiman, A.B.; Ramayah, T.; Molla, A. Senior managers’ perception on green information systems (IS) adoption and environmental performance: Results from a field survey. Inf. Manag. 2016, 53, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monod, E. The illusion of transparency: Examining power dynamics in AI implementation strategies. Inf. Technol. People 2023, 36, 1379–1402. [Google Scholar]

- Avelino, F. Power in sustainability transitions: Analysing power and (dis)empowerment in transformative change towards sustainability. Environ. Policy Gov. 2017, 27, 505–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roscoe, S.; Subramanian, N.; Jabbour, C.J.; Chong, T. Green human resource management and the enablers of green organizational culture: Enhancing a firm’s environmental performance for sustainable development. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 212–226. [Google Scholar]

- Casciaro, T.; Piskorski, M.J. Power imbalance, mutual dependence, and constraint absorption: A closer look at resource dependence theory. Adm. Sci. Q. 2005, 50, 167–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saberi, S.; Kouhizadeh, M.; Sarkis, J.; Shen, L. Blockchain technology and its relationships to sustainable supply chain management. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 2117–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuboff, S. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power; Profile Books: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, S.L.; Chen, V.Z. How to engage the crowd for innovation in restricted markets? A practice perspective of Google’s boundary spanning in China. Inf. Technol. People 2018, 31, 635–655. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Singapore, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, S.; Roome, N. Sustainable business: Learning-action networks as organizational assets. Bus. Strategy Environ. 1999, 8, 296–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vellis, R.F. Scale Development: Theory and Applications, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Singapore, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage Learning: New Delhi, India, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetters, M.D.; Curry, L.A.; Creswell, J.W. Achieving integration in mixed methods designs—Principles and practices. Health Serv. Res. 2013, 48 Pt 2, 2134–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markard, J.; Raven, R.; Truffer, B. Sustainability transitions: An emerging field of research and its prospects. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 955–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, B.; Purdy, J. Collaborating for Our Future: Multistakeholder Partnerships for Solving Complex Problems; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Sample Items | Source | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inter-organizational Power Mobilization | “Our organization builds coalitions with external stakeholders to advance sustainability initiatives”; “We strategically frame sustainability initiatives to align with partners’ priorities” | Adapted from Westover (2025) [3] and Touboulic et al. (2014) [5] | 0.89 |

| Digital Transparency Mechanisms | “Our organization uses digital platforms to create supply chain transparency”; “Digital tools help us make sustainability impacts visible to stakeholders” | Developed based on Saberi et al. (2019) [19] | 0.91 |

| Collaborative Governance Structures | “Our organization has established shared decision-making processes with key partners”; “We have formal structures for collaborative problem-solving with external stakeholders” | Adapted from Huxham & Vangen (2005) [4] | 0.88 |

| Capability Building Networks | “Our organization invests in building sustainability capabilities across our supply chain”; “We participate in knowledge-sharing networks with external partners” | Developed based on Clarke & Roome (1999) [24] | 0.85 |

| Integration Across Boundaries | “Sustainability considerations are integrated into supplier selection and management”; “Our sustainability strategy is developed collaboratively with key external stakeholders” | Adapted from Westover (2025) [3] | 0.90 |

| Transformation Outcomes | “Our sustainability initiatives have transformed relationships with suppliers and partners”; “We have achieved significant sustainability improvements across our value chain” | Adapted from Westover (2025) [3] and Williams et al. (2017) [6] | 0.87 |

| Variable | M | SD | CR | AVE | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Inter-org. Power Mobilization | 4.78 | 1.21 | 0.91 | 0.64 | 0.80 | |||||

| 2. Digital Transparency Mechanisms | 4.33 | 1.56 | 0.93 | 0.68 | 0.42 ** | 0.82 | ||||

| 3. Collaborative Governance | 3.95 | 1.38 | 0.90 | 0.61 | 0.39 ** | 0.34 ** | 0.78 | |||

| 4. Capability Building Networks | 4.26 | 1.27 | 0.88 | 0.57 | 0.45 ** | 0.38 ** | 0.51 ** | 0.75 | ||

| 5. Integration Across Boundaries | 4.15 | 1.33 | 0.92 | 0.63 | 0.48 ** | 0.52 ** | 0.44 ** | 0.49 ** | 0.79 | |

| 6. Transformation Outcomes | 3.89 | 1.42 | 0.89 | 0.59 | 0.37 ** | 0.47 ** | 0.33 ** | 0.41 ** | 0.56 ** | 0.77 |

| Construct | Items (Abbreviated) | Loading | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inter-org. Power Mobilization | Build coalitions with stakeholders | 0.85 ** | 0.74–0.85 |

| Create shared sustainability narratives | 0.82 ** | ||

| Acknowledge and address power imbalances | 0.74 ** | ||

| Digital Transparency Mechanisms | Use digital platforms for supply chain transparency | 0.86 ** | 0.75–0.88 |

| Create two-way visibility with digital tools | 0.83 ** | ||

| Involve partners in design of digital systems | 0.75 ** | ||

| Collaborative Governance | Establish shared decision-making processes | 0.84 ** | 0.72–0.84 |

| Include representation from external stakeholders | 0.78 ** | ||

| Distribute decision-making authority | 0.72 ** | ||

| Capability Building Networks | Invest in building supply chain capabilities | 0.81 ** | 0.70–0.81 |

| Create platforms for cross-organizational learning | 0.76 ** | ||

| Value diverse stakeholder knowledge | 0.70 ** | ||

| Integration Across Boundaries | Integrate sustainability into supplier management | 0.85 ** | 0.74–0.85 |

| Develop strategy collaboratively with stakeholders | 0.83 ** | ||

| Align sustainability goals with partners | 0.74 ** | ||

| Transformation Outcomes | Transform relationships with suppliers/partners | 0.80 ** | 0.71–0.80 |

| Create shared value for all participants | 0.77 ** | ||

| Improve overall supply chain resilience | 0.71 ** |

| Hypothesis | Path | Coefficient | 95% CI | p-Value | Effect Size (f2) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Inter-organizational Power Mobilization → Integration Across Boundaries | 0.36 | [0.28, 0.44] | <0.01 | 0.21 | Supported |

| H2 | Digital Transparency Mechanisms → Integration Across Boundaries | 0.41 | [0.33, 0.49] | <0.01 | 0.28 | Supported |

| H3 | Collaborative Governance Structures → Integration Across Boundaries | 0.34 | [0.26, 0.42] | <0.01 | 0.19 | Supported |

| H4 | Capability Building Networks → Integration Across Boundaries | 0.38 | [0.30, 0.46] | <0.01 | 0.23 | Supported |

| H5 | Integration Across Boundaries → Transformation Outcomes | 0.45 | [0.37, 0.53] | <0.01 | 0.31 | Supported |

| H6 | Digital Transparency Mechanisms × Supply Chain Position → Integration Across Boundaries | 0.22 | [0.14, 0.30] | <0.01 | 0.12 | Supported |

| H7 | Collaborative Governance Structures × Sector → Integration Across Boundaries | 0.17 | [0.09, 0.25] | <0.01 | 0.09 | Supported |

| Path | Large Organizations | SMEs | Difference | 95% CI of Difference | p-Value * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital Transparency → Integration | 0.46 ** [0.34, 0.58] | 0.33 ** [0.21, 0.45] | 0.13 * | [0.02, 0.24] | 0.025 |

| Collaborative Governance → Integration | 0.35 ** [0.23, 0.47] | 0.32 ** [0.20, 0.44] | 0.03 | [−0.08, 0.14] | 0.571 |

| Capability Networks → Integration | 0.37 ** [0.25, 0.49] | 0.40 ** [0.28, 0.52] | −0.03 | [−0.14, 0.08] | 0.571 |

| Path | Focal Firms | Suppliers | Difference | 95% CI of Difference | p-Value * |

| Digital Transparency → Integration | 0.29 ** [0.19, 0.39] | 0.53 ** [0.41, 0.65] | −0.24 ** | [−0.36, −0.12] | <0.001 |

| Collaborative Governance → Integration | 0.32 ** [0.22, 0.42] | 0.36 ** [0.24, 0.48] | −0.04 | [−0.16, 0.08] | 0.571 |

| Capability Networks → Integration | 0.31 ** [0.21, 0.41] | 0.44 ** [0.32, 0.56] | −0.13 * | [−0.25, −0.01] | 0.038 |

| Path | Manufacturing | Services | Difference | 95% CI of Difference | p-Value * |

| Digital Transparency → Integration | 0.40 ** [0.28, 0.52] | 0.43 ** [0.31, 0.55] | −0.03 | [−0.15, 0.09] | 0.571 |

| Collaborative Governance → Integration | 0.28 ** [0.18, 0.38] | 0.41 ** [0.29, 0.53] | −0.13 * | [−0.25, −0.01] | 0.038 |

| Capability Networks → Integration | 0.35 ** [0.23, 0.47] | 0.40 ** [0.28, 0.52] | −0.05 | [−0.17, 0.07] | 0.571 |

| Quantitative Finding | Qualitative Theme | Illustrative Quote | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Digital transparency has strongest effect on integration (β = 0.41) | Transparency as Power Equalizer | “The blockchain traceability system fundamentally changed our relationship with suppliers. Instead of us imposing requirements and them struggling to comply, we now have shared visibility of sustainability impacts that enables collaborative problem-solving. Information access has become more democratic, which shifts the power balance in subtle but important ways.” (Sustainability Director, Consumer Goods Firm) | Digital transparency creates shared understanding of sustainability impacts and reduces information asymmetries that traditionally advantage more powerful actors |

| Digital transparency effect stronger for suppliers (β = 0.53) than focal firms (β = 0.29) | Technology Design for Power Balancing | “When we designed the system, we made a conscious choice to create bidirectional transparency—not just visibility for us into supplier practices, but also visibility for suppliers into how their materials flow through our system. This bidirectional design was critical for creating more balanced relationships rather than just another surveillance tool.” (Technology Director, Manufacturing Firm) | Digital tools must be specifically designed for power equalization through bidirectional transparency and collaborative development processes |

| Collaborative governance stronger in services (β = 0.41) than manufacturing (β = 0.28) | From Power Over to Power With | “We realized that using our purchasing power to demand compliance was yielding minimal results. Suppliers would do the minimum to check the box. When we shifted to a partnership approach—joint innovation projects, shared goal-setting, mutual accountability—we saw transformative improvements in sustainability performance.” (Supply Chain Director, Manufacturing Firm) | Shift from coercive to collaborative approaches happens through intentional governance structures that institutionalize more balanced relationships |

| Capability building stronger for suppliers (β = 0.44) than focal firms (β = 0.31) | Power Dynamics as Evolutionary Process | “Our sustainability journey has transformed relationships with our larger customers. Initially, we were just responding to their requirements, feeling pressure without support. Over time, as we demonstrated value and built our own expertise, the relationship evolved. Now we’re viewed as sustainability partners rather than just suppliers who need to be monitored.” (Operations Manager, Small Manufacturing Supplier) | Power relationships evolve over time as capability building enables less powerful actors to contribute unique value to sustainability initiatives |

| Contextual Factor | Characteristic | Recommended Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Regulatory Environment | Strong regulation | Emphasize shared compliance through collaborative working groups |

| Voluntary context | Develop incentive structures to balance power and create mutual benefits | |

| Market Positioning | Consumer-facing | Leverage external stakeholder pressure to drive collaborative approaches |

| B2B | Emphasize business case and competitive advantage of power-sharing | |

| Organizational Size | Large organization | Implement formal governance structures with clear representation |

| SME | Focus on network-based approaches and coalition building | |

| Cultural Context | Hierarchical | Design collaborative approaches that respect formal positions while enabling input |

| Egalitarian | Implement direct participation and flat governance structures | |

| Supply Chain Position | Focal firm | Proactively share power through formal mechanisms and capability building |

| Supplier | Build coalitions and leverage unique sustainability expertise | |

| Sector | Manufacturing | Emphasize digital transparency and operational integration |

| Services | Focus on collaborative governance and stakeholder engagement |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Westover, J.H. Navigating Power Dynamics in Sustainability Transformation: Extending Integration Mechanisms Across Organizational Boundaries. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9925. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17229925

Westover JH. Navigating Power Dynamics in Sustainability Transformation: Extending Integration Mechanisms Across Organizational Boundaries. Sustainability. 2025; 17(22):9925. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17229925

Chicago/Turabian StyleWestover, Jonathan H. 2025. "Navigating Power Dynamics in Sustainability Transformation: Extending Integration Mechanisms Across Organizational Boundaries" Sustainability 17, no. 22: 9925. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17229925

APA StyleWestover, J. H. (2025). Navigating Power Dynamics in Sustainability Transformation: Extending Integration Mechanisms Across Organizational Boundaries. Sustainability, 17(22), 9925. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17229925