Linking Sustainability and Brand Love Through Employees’ Insights on ESG Practices in the Airline Industry

Abstract

1. Introduction

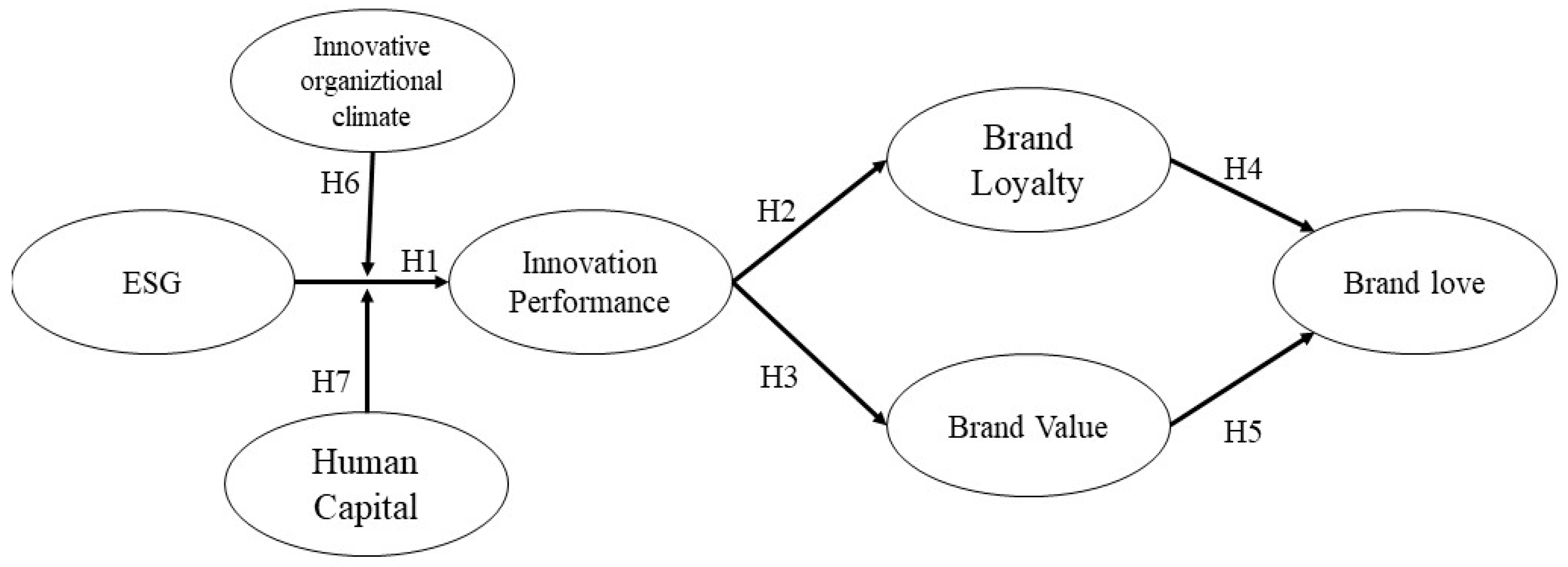

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Relationships Between ESG, Innovation Performance and Brand Dimensions

2.2. The Moderating Roles of Innovative Organizational Climate and Human Capital

3. Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Measurement of Scales

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Analysis

4.2. Evaluation of the Measurement Model

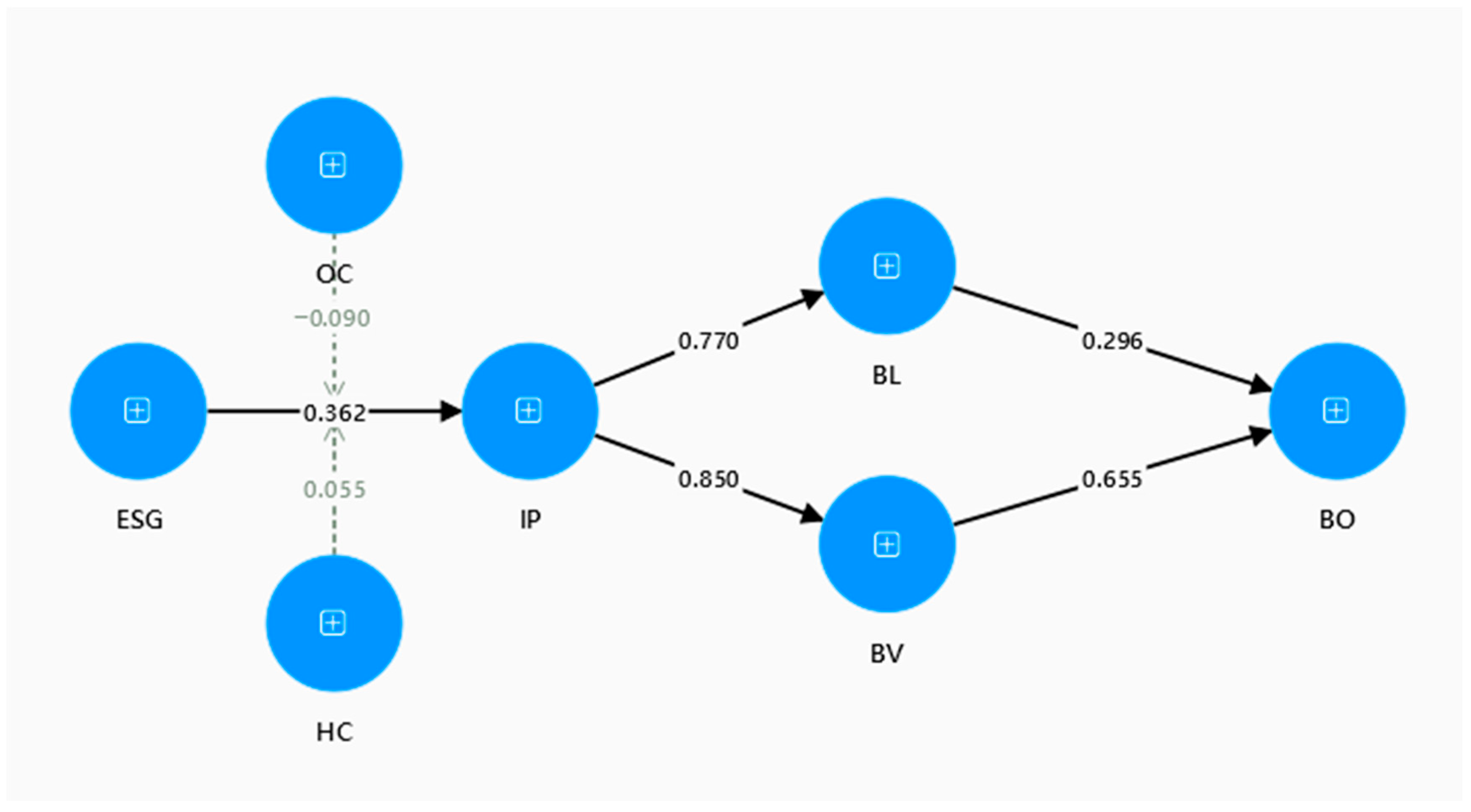

4.3. Structural Model Analysis

4.4. Examination and Analysis of the Moderating Effect

5. Discussion

6. Implications

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Empirical Implications

6.3. Research Limitations and Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Detention | Items | Source |

|---|---|---|

| ESG practice | ER1. The company participates in environmental protection activities. | Kim & Hwang (2023) [18] |

| ER2. The company reduces waste and uses eco-friendly products. | ||

| ER3. The company effectively utilizes energy and resources. | ||

| ER4. The company has reduced the pollution caused by its business activities. | ||

| ER5. The company conducts business activities in compliance with environmental laws and policies. | ||

| ER6. The company uses renewable energy and reduces ground energy consumption. | ||

| SR7. The company raises funds for social causes. | ||

| SR8. The company supports sports and cultural activities. | ||

| SR9. The company encourages employees to participate in volunteer activities in the local community. | ||

| GR11. The company contributes to society and the economy through investment and profit creation. | ||

| GR12. The company creates new job opportunities. | ||

| GR13. The company creates more value for national economic development. | ||

| Innovation performance | PI14. The company launches many new sustainability-related services. | Lim (2021) [96] |

| PI15. The company has made many sustainability-related adjustments to existing services. | ||

| PI16. The company continuously seeks new sustainability service initiatives | ||

| PI17. The company launches more new sustainability services than its competitors. | ||

| PI18. The sustainability initiatives launched by the company have led to significant changes in the industry. | ||

| PrI19. The company often compares its sustainability initiatives with those of top international companies to stay up-to-date. | ||

| PrI20 The company regularly updates its sustainability services to improve productivity. | ||

| PrI21. The company often adopts new technologies to improve the efficiency of its sustainability initiatives. | ||

| PrI22. The company often adopts new technologies to improve the quality of our sustainability services. | ||

| PrI23. The company invests in integrating sustainable technologies, equipment, and/or procedures to respond to market changes. | ||

| PrI24. The company regularly trains employees on new technologies in the field of sustainability. | ||

| AI25. The company continuously introduces new management methods to adapt to sustainability initiatives. | ||

| AI26. The company invests in new administrative procedural systems that are more aligned with sustainability. | ||

| AI27. Management continuously seeks to improve administrative procedural systems for sustainability. | ||

| AI28. The company empowers employees to take initiative in response to sustainability changes in the market. | ||

| AI29. Competitors use the company’s sustainability practices as a benchmark. | ||

| Brand values | BV38. The brand represents the organizational values of our company. | Muhonen, Hirvonen, and Laukkanen (2017) [98] |

| BV39. The company’s marketing methods follow our brand values. | ||

| BV40. We are committed to integrating the marketing activities of our company’s brand. | ||

| Brand love | BO41. I have strong feelings for the company’s brand. | Puriwat & Tripopsakul (2023) [97] |

| BO42. You think I am suitable for this company’s brand. | ||

| BO43. I evaluate the company’s brand as the same as your personal preferences. | ||

| BO44. I can build a long-term relationship with the company’s brand. | ||

| Brand loyalty | BL45. I will continue to work for the company. | Puriwat & Tripopsakul (2023) [97] |

| BL46. I am willing to identify with this company. | ||

| BL47. I am willing to make a commitment to this company. | ||

| BL48. I am willing to give more to this company compared to switching to another. | ||

| Innovative organizational climate | OC30. At the company, I am often encouraged to propose new sustainability ideas. | Hieu (2023) [99] |

| OC31. At the company, my sustainability innovation behaviors are praised. | ||

| OC32. At the company, I can challenge others through positive thinking. | ||

| OC33. At the company, I am expected to act in a more sustainable and creative way. | ||

| OC34. At the company, a sufficient budget is provided to support sustainability innovation. | ||

| OC35. At the company, it is acceptable for employees not to achieve the expected results when executing sustainability innovation learning plans. | ||

| OC36. At the company, my superior values the sustainability contributions I make. | ||

| OC37. At the company, I am free to exchange sustainability ideas. | ||

| Human Capital | HC49. The company’s employees receive appropriate sustainability education to complete their work. | Liu (2017) [85] |

| HC50. The company’s employees have appropriate sustainability experience to successfully complete their work. | ||

| HC51. The company’s employees are well-trained to respond to global sustainability changes. | ||

| HC52. No one understands this sustainability work better than the employees of our company. | ||

| HC53. If anyone can find the best executor for sustainable work, it’s the employees of our company. | ||

| HC54. Mastering the execution of sustainable work is of great significance to the employees of our company. |

References

- Lee, H.J.; Rhee, T.H. How does corporate ESG management affect consumers’ brand choice? Sustainability 2023, 15, 6795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Ok, Y.S.; Rhee, J.H. How to enhance ESG credentials through corporate governance innovation: The case of DGB Financial Group in South Korea. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2025, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, G.H.; Firoiu, D.; Pirvu, R.; Vilag, R.D. The impact of ESG factors on market value of companies from travel and tourism industry. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2019, 25, 820–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lins, K.V.; Servaes, H.; Tamayo, A. Social capital, trust, and firm performance: The value of corporate social responsibility during the financial crisis. J. Financ. 2017, 72, 1785–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, J.M.; Sun, W. Doing good and doing bad: The impact of corporate social responsibility and irresponsibility on firm performance. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 80, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.; Choi, J. Artificial intelligence-based toxicity prediction of environmental chemicals: Future directions for chemical management applications. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 7532–7543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Lee, K.P.; You, C.Y. Does ESG performance enhance the financial performance and valuation of Chinese private enterprises? The moderating role of political connection and state ownership. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2025, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, M.; Kim, H. Measurement validation of a consumer-driven environmental, social, and governance (ESG) index for the airline industry. J. Sustain. Tour. 2025, 33, 474–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunday, G.; Ulusoy, G.; Kilic, K.; Alpkan, L. Effects of innovation types on firm performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2011, 133, 662–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R.G.; Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. The impact of corporate sustainability on organizational processes and performance. Manag. Sci. 2014, 60, 2835–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatemi, A.; Fooladi, I.; Tehranian, H. Valuation effects of corporate social responsibility. J. Bank. Financ. 2015, 59, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, W.J. Antecedents of labor turnover in Australian alpine resorts. J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tour. 2007, 6, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Li, Q.; Wang, X. Investigating how corporate social responsibility affects employees’ thriving at work: A social exchange perspective. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andruszkiewicz, K.; Wierzejski, T.; Siemiński, M. The effect of corporate social responsibility and sustainable development practices on employer branding—A case study of an international corporation operating in Poland. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahhan, S.A. Emotional Intelligence and Employees’ Commitment: Analyzing the Role of Brand Image and Corporate Social Responsibility Among Lebanese SMEs. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturkoglu, Y.; Kazancoglu, Y.; Ozkan-Ozen, Y.D. A sustainable and preventative risk management model for ship recycling industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 238, 117907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deegan, C. Introduction: The legitimising effect of social and environmental disclosures—A theoretical foundation. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2002, 15, 282–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Hwang, J. Airline CSR and Quality Attributes as Driving Forces of Passengers’ Brand Love: Comparing Full-Service Carriers with Low-Cost Carriers. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; You, E.S.; Lee, T.J.; Li, X. The influence of historical nostalgia on a heritage destination’s brand authenticity, brand attachment, and brand equity: Historical nostalgia on a heritage destination’s brand authenticity. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 23, 1176–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, S.; Hino, H. Emotional brand attachment: A factor in customer-bank relationships. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2016, 34, 136–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Suárez, M. Examining customer–brand relationships: A critical approach to empirical models on brand attachment, love, and engagement. Adm. Sci. 2019, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, A.; Khan, Z. Fostering sustainable relationships in Pakistani cellular service industry through CSR and brand love. S. Asian J. Bus. Stud. 2023, 12, 293–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Chernatony, L. Succeeding with brands on the Internet. J. Brand Manag. 2001, 8, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urde, M.; Greyser, S.A. The Nobel Prize: The identity of a corporate heritage brand. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2015, 24, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitelock, V.G. Relationship Between Environmental Social Governance (ESG) Management and Performance–The Role of Collaboration in the Supply Chain. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Toledo, Toledo, OH, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bae, J.H.; Park, J.W. Research into individual factors affecting safety within airport subsidiaries. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortas, E.; Álvarez, I.; Garayar, A. The environmental, social, governance and financial performance effects on companies that adopt the United Nations Global Compact. Sustainability 2015, 7, 1932–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdan, V.; Rus, L.; Gherai, D.S.; Florea, A.G.; Bugnar, N.G. A streamline sustainable business performance reporting model by an integrated FinESG approach. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Sun, J.; Lin, Y.E.; Hu, J. ESG and investment efficiency: The role of marketing capability. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Yu, J.; Kim, W. Environmental corporate social responsibility and the strategy to boost the airline’s image and customer loyalty intentions. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, K.; Oates, W.E.; Portney, P.R. Tightening environmental standards: The benefit-cost or the no-cost paradigm? J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M. Value-enhancing capabilities of CSR: A brief review of contemporary literature. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 127, 419–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M.A.; Chew, B.C.; Hamid, S.R. Benchmarking key success factors for the future green airline industry. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 224, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.Y.; Chang, Y.H.; Lin, Y.H. Customer perceptions of airline social responsibility and its effect on loyalty. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2012, 20, 49–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilkhanizadeh, S.; Karatepe, O.M. An examination of the consequences of corporate social responsibility in the airline industry: Work engagement, career satisfaction, and voice behavior. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2017, 59, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vural-Yavaş, Ç. Economic policy uncertainty, stakeholder engagement, and environmental, social, and governance practices: The moderating effect of competition. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 82–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, C.V.; Liu, S.F.; Chen, S.H. Corporate ESG performance and intellectual capital: International evidence. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2024, 29, 306–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Lai, S.B.; Wen, C.T. The influence of green innovation performance on corporate advantage in Taiwan. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 67, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodhanwala, S.; Bodhanwala, R. Exploring relationship between sustainability and firm performance in travel and tourism industry: A global evidence. Soc. Responsib. J. 2022, 18, 1251–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, P.H.; Chiu, Y.H.; Huang, C.H. Exploring the research development trajectory and trends of green finance. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2025, 30, 100329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Racherla, P. Visual representation of knowledge networks: A social network analysis of hospitality research domain. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2008, 27, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, H.K.; Burnasheva, R.; Suh, Y.G. Perceived ESG (environmental, social, governance) and consumers’ responses: The mediating role of brand credibility, Brand Image, and perceived quality. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Chin, T. ESG performance and the ecosystem-based business model innovation: Evidence from Chinese firms. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2024, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, B.; Samson, D. Developing innovation capability in organisations: A dynamic capabilities approach. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2001, 5, 377–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Liu, J.; George, G. The dynamic impact of innovative capability and inter-firm network on firm valuation: A longitudinal study of biotechnology start-ups. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 593–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damanpour, F. Organizational innovation: A meta-analysis of effects of determinants and moderators. Acad. Manag. J. 1991, 34, 555–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alon, A.; Elron, D.; Jackson, L. Innovation: Clear vision, cloudy execution. Accenture 2015 US innovation survey. Retrieved Oct. 2015, 26, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.A.R.; Sheikh, A.A.; Ashraf, M.; Yu, Z. Improving consumer-based green brand equity: The role of healthy green practices, green brand attachment, and green skepticism. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, K.; Moon, J.; Lee, S. Synergy of corporate social responsibility and service quality for airlines: The moderating role of carrier type. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2015, 47, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Yu, J.; Lee, K.S.; Baek, H. Impact of corporate social responsibilities on customer responses and brand choices. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2020, 37, 302–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Zou, Q.; Isabel, J.Z.A.; Mao, Z.; Jiang, J. Green Fiscal Policy and Brand Development Potential: Evidence from China’s Comprehensive Demonstration Cities for Energy Conservation and Emission Reduction. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawson, A.; Duncan, E.; Jones, C. The truth about customer experience. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2013, 91, 90–98. [Google Scholar]

- Gorska-Warsewicz, H.; Dębski, M.; Fabuš, M.; Kováč, M. Green brand equity—Empirical experience from a systematic literature review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, S.; Chu, L. The mediating role of consumer satisfaction in the relationship between brand equity and brand loyalty based on PLS-SEM Model. Int. Bus. Res. 2015, 8, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, R.L. Service quality and the training of employees: The mediating role of organizational commitment. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekk, M.; Spörrle, M.; Hedjasie, R.; Kerschreiter, R. Greening the competitive advantage: Antecedents and consequences of green brand equity. Qual. Quant. 2016, 50, 1727–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, B.A.; Ahuvia, A.C. Some antecedents and outcomes of brand love. Mark. Lett. 2006, 17, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, R.; Ahuvia, A.; Bagozzi, R.P. Brand love. J. Mark. 2012, 76, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Choi, J.K. An investigation of passengers’ psychological benefits from green brands in an environmentally friendly airline context: The moderating role of gender. Sustainability 2017, 10, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daou, L.; Sayegh, E.; Atallah, E.; Jabbour Al Maalouf, N.; Sarkis, N. Greenwashing as a Barrier to Sustainable Marketing: Expectation Disconfirmation, Confusion, and Brand Consumer Relationships. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, M.; Mohd-Any, A.A.; Kamarulzaman, Y. Validating a consumer-based service brand equity (CBSBE) model in the airline industry. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 59, 102354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susanty, A.; Kenny, E. The relationship between brand equity, customer satisfaction, and brand loyalty on coffee shop: Study of Excelso and Starbucks. ASEAN Mark. J. 2015, 7, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, M.A. Customer satisfaction and hotel brand equity: A structural equation modelling study. J. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 5, 144–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Iglesias, O.; Markovic, S.; Rialp, J. How does sensory brand experience influence brand equity? Considering the roles of customer satisfaction, customer affective commitment, and employee empathy. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 96, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizik, N. Assessing the total financial performance impact of brand equity with limited time-series data. J. Mark. Res. 2014, 51, 691–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A.; Holbrook, M.B. The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: The role of brand loyalty. J. Mark. 2001, 65, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekhar Kumar, R.; Dash, S.; Chandra Purwar, P. The nature and antecedents of brand equity and its dimensions. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2013, 31, 141–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ta’Amnha, M.; Kurtishi-Kastrati, S.; Magableh, I.K.; Riyadh, H.A. Sustainable Employer Branding as a Catalyst for Safety Voice Behavior in Healthcare: The Mediating Role of Employee Engagement. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas-Avila, J.; Abreu-Ledón, R.; Tamayo-Arias, J. Intellectual capital and knowledge generation: An empirical study from Colombian public universities. J. Intellect. Cap. 2020, 21, 1053–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dineen, B.R.; Allen, D.G. Third party employment branding: Human capital inflows and outflows following “best places to work” certifications. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 90–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arhinful, R.; Mensah, L.; Owusu-Sarfo, J.S. Board governance and ESG performance in Tokyo stock exchange-listed automobile companies: An empirical analysis. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2024, 29, 397–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.D.; Mao, Z.E.; Zhao, X.R.; Mattila, A.S. How does social capital influence the hospitality firm’s financial performance? The moderating role of entrepreneurial activities. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 51, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, P.S.; Kwon, S.W. Social capital: Prospects for a new concept. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozbura, F.T.; Beskese, A. Prioritization of organizational capital measurement indicators using fuzzy AHP. Int. J. Approx. Reason. 2007, 44, 124–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olusegun Adedipe, C.; Olusola Adeleke, B. Human capital development in the Nigerian hospitality industry: The imperative for a stakeholder driven initiative. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2016, 8, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, H.; Liu, Y.; Peng, M.W. Managerial ties, organizational learning, and opportunity capture: A social capital perspective. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2014, 31, 271–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mention, A.L. Intellectual capital, innovation and performance: A systematic review of the literature. Bus. Econ. Res. 2012, 2, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauss, T.; Abebe, M.; Tangpong, C.; Hock, M. Strategic agility, business model innovation, and firm performance: An empirical investigation. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2019, 68, 767–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-Requena, G.; Ruiz-Ortega, M.J.; Garcia-Villaverde, P.M.; Ramírez, F.J. Innovativeness and performance: The joint effect of relational trust and combinative capability. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2022, 25, 191–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Ortega, M.J.; García-Villaverde, P.M.; De La Gala-Velásquez, B.; Hurtado-Palomino, A.; Arredondo-Salas, Á.Y. Innovation capability and pioneering orientation in Peru’s cultural heritage tourism destinations: Conflicting environmental effects. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 48, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orfila-Sintes, F.; Mattsson, J. Innovation behavior in the hotel industry. Omega 2009, 37, 380–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundbo, J.; Orfila-Sintes, F.; Sørensen, F. The innovative behaviour of tourism firms—Comparative studies of Denmark and Spain. Res. Policy 2007, 36, 88–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.T. Individual attitudes to learning and sharing individual and organisational knowledge in the hospitality industry. Serv. Ind. J. 2009, 29, 1723–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, A.I.; Akhtar, S.A.; Zaheer, A. Impact of transformational and servant leadership on organizational performance: A comparative analysis. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 116, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.H. Creating competitive advantage: Linking perspectives of organization learning, innovation behavior and intellectual capital. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 66, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertini, E. An inductive typology of the interrelations between different components of intellectual capital. Manag. Decis. 2016, 54, 887–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, M.; Youndt, M.A. The influence of intellectual capital on the types of innovative capabilities. Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 450–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamadamin, H.H.; Atan, T. The impact of strategic human resource management practices on competitive advantage sustainability: The mediation of human capital development and employee commitment. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kryscynski, D.; Coff, R.; Campbell, B. Charting a path between firm-specific incentives and human capital-based competitive advantage. Strateg. Manag. J. 2021, 42, 386–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minbaeva, D.B. Building credible human capital analytics for organizational competitive advantage. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 57, 701–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, F.I.; Fang, W.T.; LePage, B.A. Proactive environmental strategies in the hotel industry: Eco-innovation, green competitive advantage, and green core competence. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 30, 1240–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faggian, A.; McCann, P. Human capital, graduate migration and innovation in British regions. Camb. J. Econ. 2009, 33, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhmetshin, E.M.; Sharafutdinov, R.I.; Gerasimov, V.O.; Dmitrieva, I.S.; Puryaev, A.S.; Ivanov, E.A.; Miheeva, N.M. Research of human capital and its potential management on the example of regions of the Russian Federation. J. Entrep. Educ. 2018, 21, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Camisón, C.; Monfort-Mir, V.M. Measuring innovation in tourism from the Schumpeterian and the dynamic-capabilities perspectives. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 776–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickham, P.P. Human experimentation. Code of ethics of the world medical association. Declaration of Helsinki. Br. Med. J. 1964, 2, 177. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, S.E. Fostering absorptive capacity and facilitating innovation in hospitality organizations through empowering leadership. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 94, 102780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puriwat, W.; Tripopsakul, S. Sustainability matters: Unravelling the power of ESG in fostering brand love and loyalty across generations and product involvements. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhonen, T.; Hirvonen, S.; Laukkanen, T. SME brand identity: Its components, and performance effects. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2017, 26, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hieu, V.M. The moderating role of innovative organizational climate on the relationship between environmental monitoring social monitoring, governance monitoring and sustainable development goals (case of Vietnam). Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2023, 36, 2111976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.M.; Cheah, J.H.; Gholamzade, R.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM’s most wanted guidance. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 35, 321–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M. Gütemaße für den Partial-Least-Squares-Ansatz zur Bestimmung von Kausalmodellen. 2004. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Christian-Ringle/publication/237525868_Gutemasse_fur_den_Partial_Least_Squares-_Ansatz_zur_Bestimmung_von_Kausalmodellen/links/540073c40cf24c81027df146/Guetemasse-fuer-den-Partial-Least-Squares-Ansatz-zur-Bestimmung-von-Kausalmodellen.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Kelloway, E.K. Structural equation modelling in perspective. J. Organ. Behav. 1995, 16, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.G., Jr.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, D.; Kong, Q. Corporate green innovation under environmental regulation: The role of ESG ratings and greenwashing. Energy Econ. 2024, 140, 107971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Rong, D.; Eweje, G.; Yuan, X.; Song, M.; Searcy, C. Effective environmental strategy or illusory tactics? Corporate greenwashing and innovation willingness. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2025, 34, 1338–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Song, Y.; Gao, P. Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance and financial outcomes: Analyzing the impact of ESG on financial performance. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behl, A.; Kumari, P.R.; Makhija, H.; Sharma, D. Exploring the relationship of ESG score and firm value using cross-lagged panel analyses: Case of the Indian energy sector. Ann. Oper. Res. 2022, 313, 231–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrigo, U.; Beccarello, M.; Di Foggia, G. Strategic response of European airlines to market dynamics: A comparative analysis. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belobaba, P.; Odoni, A.; Barnhart, C. (Eds.) The Global Airline Industry; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wittmer, A.; Bieger, T.; Müller, R. (Eds.) Aviation Systems: Management of the Integrated Aviation Value Chain; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 355–386. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H.; Yu, J.; Chua, B.L.; Lee, S.; Kim, W. Impact of core-product and service-encounter quality, attitude, image, trust and love on repurchase: Full-service vs low-cost carriers in South Korea. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 1588–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, Y.; Li, X.; Càmara-Turull, X. Impact of sustainability on firm value and financial performance in the air transport industry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, Y.; Li, X.; Càmara-Turull, X. Exploring the impact of sustainability (ESG) disclosure on firm value and financial performance (FP) in airline industry: The moderating role of size and age. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 5052–5079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Park, J.W.; Choi, D. The Effects of ESG management on business performance: The case of Incheon International Airport. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Bae, J. Cross-cultural differences in concrete and abstract corporate social responsibility (CSR) campaigns: Perceived message clarity and perceived CSR as mediators. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2016, 1, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamberti, L.; Lettieri, E. CSR practices and corporate strategy: Evidence from a longitudinal case study. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 87, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Background Variables | Category | Total | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 94 | 27.2 |

| Female | 252 | 72.8 | |

| Age | 21~30 | 50 | 14.5 |

| 31~40 | 160 | 46.1 | |

| 41~50 | 84 | 24.3 | |

| 51~60 | 50 | 14.5 | |

| 61 up | 2 | 0.6 | |

| Education | College diploma/undergraduate | 257 | 74.3 |

| Postgraduate | 89 | 25.7 | |

| Service type | Air duty | 196 | 56.6 |

| Ground service | 150 | 43.4 | |

| Job title | Flight Attendant | 147 | 42.5 |

| Chief Flight Attendant | 24 | 6.9 | |

| Cabin Manager | 19 | 5.5 | |

| Ground Staff Supervisor | 23 | 6.6 | |

| Ground Staff | 113 | 32.7 | |

| Other | 20 | 5.8 | |

| seniority | Under 5 years | 23 | 6.6 |

| 5–10 years | 63 | 18.2 | |

| 11~15 years | 128 | 37.0 | |

| 16~20 years | 28 | 8.1 | |

| 21~25 years | 54 | 15.6 | |

| over 25 years | 50 | 14.5 |

| Item | Variables | Factor Loadings | Cronbach’s α | Composite Reliability | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESG practice | ER1 | 0.867 | 0.970 | 0.973 | 0.752 |

| ER2 | 0.820 | ||||

| ER3 | 0.888 | ||||

| ER4 | 0.918 | ||||

| ER5 | 0.881 | ||||

| ER6 | 0.895 | ||||

| SR7 | 0.789 | ||||

| SR8 | 0.899 | ||||

| SR9 | 0.894 | ||||

| GR11 | 0.864 | ||||

| GR12 | 0.837 | ||||

| GR13 | 0.845 | ||||

| Innovation performance | PI14 | 0.898 | 0.985 | 0.987 | 0.821 |

| PI15 | 0.897 | ||||

| PI16 | 0.902 | ||||

| PI17 | 0.911 | ||||

| PI18 | 0.915 | ||||

| PrI19 | 0.916 | ||||

| PrI20 | 0.933 | ||||

| PrI21 | 0.949 | ||||

| PrI22 | 0.954 | ||||

| PrI23 | 0.902 | ||||

| PrI24 | 0.911 | ||||

| AI25 | 0.896 | ||||

| AI26 | 0.842 | ||||

| AI27 | 0.907 | ||||

| AI28 | 0.903 | ||||

| AI29 | 0.851 | ||||

| Brand values | BV38 | 0.957 | 0.964 | 0.977 | 0.933 |

| BV39 | 0.974 | ||||

| BV40 | 0.966 | ||||

| Brand loyalty | BL45 | 0.950 | 0.977 | 0.983 | 0.934 |

| BL46 | 0.981 | ||||

| BL47 | 0.975 | ||||

| BL48 | 0.960 | ||||

| Brand love | BO41 | 0.934 | 0.970 | 0.978 | 0.918 |

| BO42 | 0.967 | ||||

| BO43 | 0.969 | ||||

| BO44 | 0.962 | ||||

| Innovative Organizational Climate | OC30 | 0.945 | 0.979 | 0.982 | 0.870 |

| OC31 | 0.938 | ||||

| OC32 | 0.937 | ||||

| OC33 | 0.951 | ||||

| OC34 | 0.933 | ||||

| OC35 | 0.922 | ||||

| OC36 | 0.950 | ||||

| OC37 | 0.886 | ||||

| Human Capital | HC49 | 0.929 | 0.973 | 0.978 | 0.880 |

| HC50 | 0.951 | ||||

| HC51 | 0.949 | ||||

| HC52 | 0.926 | ||||

| HC53 | 0.949 | ||||

| HC54 | 0.922 |

| BL | BO | BV | ESG | HC | IP | OC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brand loyalty | 0.967 | ||||||

| Brand love | 0.858 | 0.958 | |||||

| Brand values | 0.859 | 0.909 | 0.966 | ||||

| ESG practice | 0.800 | 0.844 | 0.813 | 0.867 | |||

| Human Capital | 0.869 | 0.868 | 0.858 | 0.857 | 0.938 | ||

| Innovation performance | 0.770 | 0.834 | 0.850 | 0.899 | 0.863 | 0.906 | |

| Innovative Organizational Climate | 0.731 | 0.814 | 0.821 | 0.832 | 0.824 | 0.899 | 0.933 |

| BL | BO | BV | ESG | IP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brand loyalty | |||||

| Brand love | 0.881 | ||||

| Brand values | 0.885 | 0.939 | |||

| ESG practice | 0.821 | 0.868 | 0.838 | ||

| Innovation performance | 0.784 | 0.853 | 0.872 | 0.917 |

| Hypothesis | Path | β | t | R2 | f2 | VIF | 95% CI LL | 95% CI UL | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | ESG→IP | 0.362 | 68.846 *** | 0.809 | 4.243 | 1.000 | 0.870 | 0.922 | supported |

| H2 | IP→BL | 0.770 | 24.810 *** | 0.593 | 1.460 | 1.000 | 0.703 | 0.826 | supported |

| H3 | IP→BV | 0.850 | 43.342 *** | 0.723 | 2.608 | 1.000 | 0.807 | 0.885 | supported |

| H4 | BL→BO | 0.296 | 5.046 *** | 0.850 | 0.153 | 3.803 | 0.186 | 0.414 | supported |

| H5 | BV→BO | 0.655 | 11.302 *** | 0.850 | 0.751 | 3.803 | 0.535 | 0.760 | supported |

| Hypothesis | Path | β | t | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H6 | ESG*OC → IP | −0.038 | 1.981 * | supported |

| H7 | ESG*HC → IP | 0.006 | 0.372 | not supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, F.-R.; Ko, W.-H.; Lu, M.-Y. Linking Sustainability and Brand Love Through Employees’ Insights on ESG Practices in the Airline Industry. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10408. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210408

Chen F-R, Ko W-H, Lu M-Y. Linking Sustainability and Brand Love Through Employees’ Insights on ESG Practices in the Airline Industry. Sustainability. 2025; 17(22):10408. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210408

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Fang-Rong, Wen-Hwa Ko, and Min-Yen Lu. 2025. "Linking Sustainability and Brand Love Through Employees’ Insights on ESG Practices in the Airline Industry" Sustainability 17, no. 22: 10408. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210408

APA StyleChen, F.-R., Ko, W.-H., & Lu, M.-Y. (2025). Linking Sustainability and Brand Love Through Employees’ Insights on ESG Practices in the Airline Industry. Sustainability, 17(22), 10408. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210408