Are Nature-Based Climate Solutions in the Russian Arctic Feasible? A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Rapidly Changing Arctic

1.2. Nature-Based Climate Solutions

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

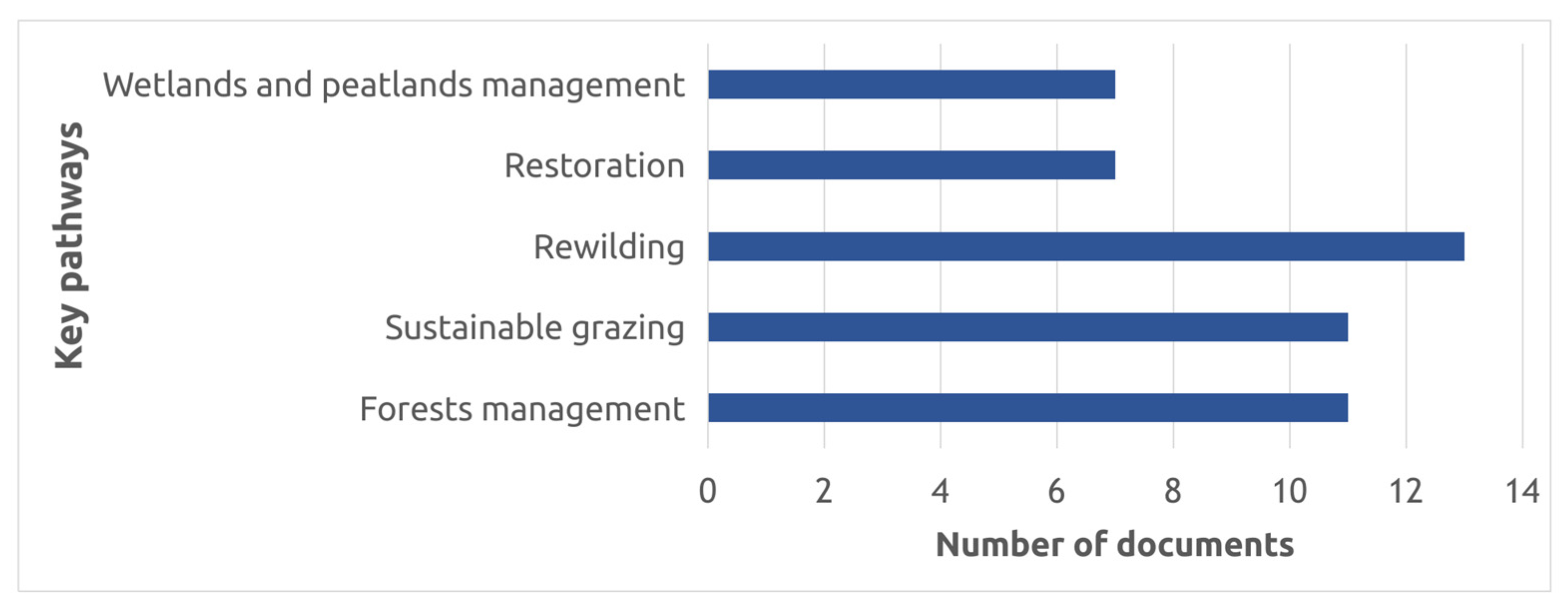

3.1. The State of Knowledge and Research Gaps

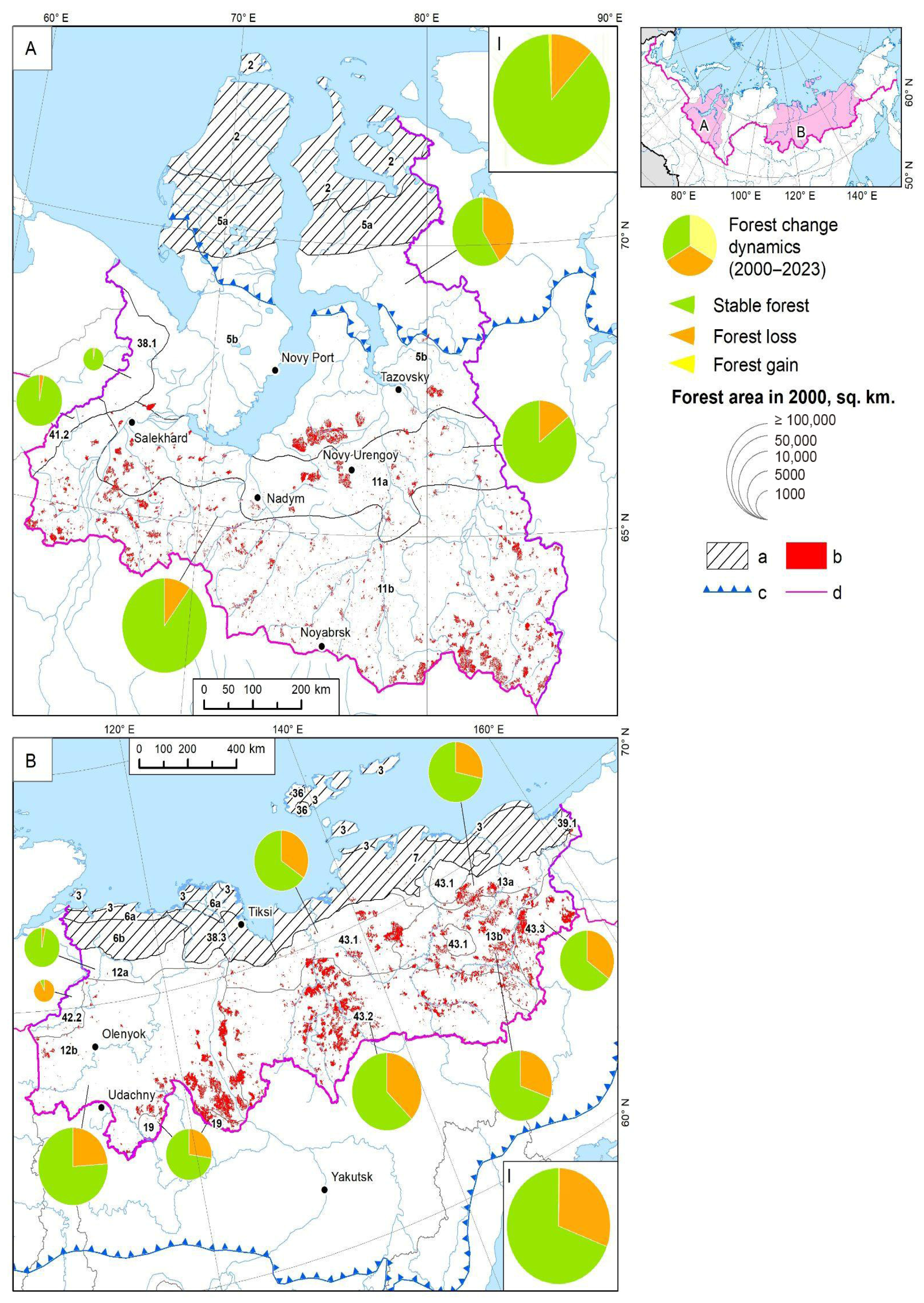

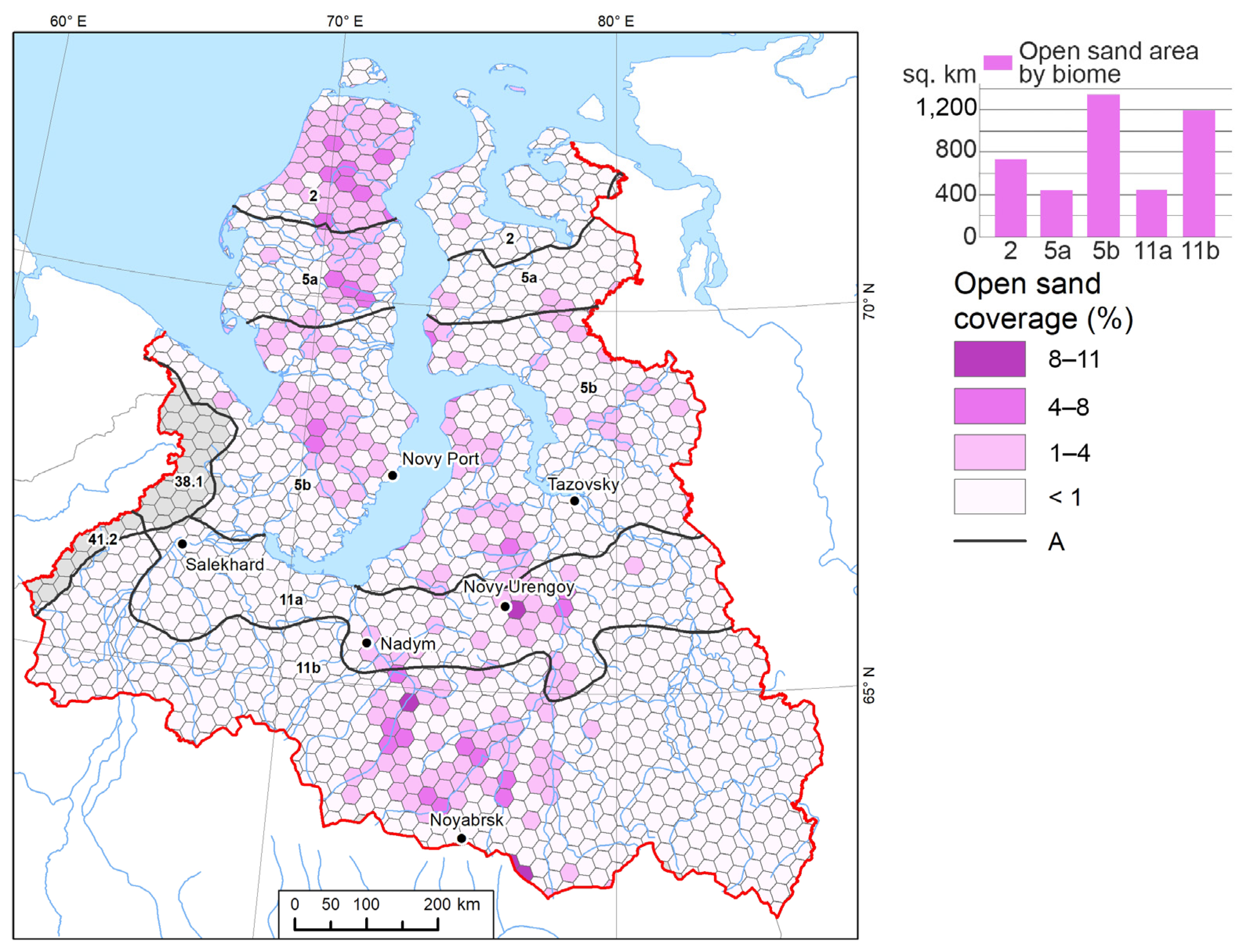

3.2. Forest in the Arctic

3.3. Sustainable Grazing Management in the Arctic

3.4. Rewilding in the Arctic

3.5. Restoration of Degraded Arctic Lands

3.6. Arctic Wetlands and Peatlands

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMAP | Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme |

| AZRF | Arctic Zone of Russian Federation |

| CAVM | Circumpolar Arctic Vegetation Map |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| GFCM | Global Forest Change map |

| GHG | Greenhouse gases |

| GLCLU | Global Land Cover and Land Use Change dataset |

| GPP | Gross Primary Production |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| MCA | Multiple Correspondence Analysis |

| NbS | Nature-based climate solutions |

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

| NEE | Net Ecosystem Exchange |

| NPP | Net Primary Production |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| Reco | Ecosystem Respiration |

| YaNAO | Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug |

Appendix A

| Biomes Index | Bioms | Tree Cover 2000, sq. km | Forest Loss (2000–2023), sq. km | Forest Loss Share (2000–2023), % | Forest Loss (% of 2000 area) | Open Sand, sq. km | Open Sand Share, % | Built-Up Areas, sq.km | Built-Up Areas Share, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Novozemelsko-Yamalo-Gydan Arctic tundra | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 725.8 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 5a | Northern hypoarctic Kola-Bolshezemelsko-Taz tundra | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 445.9 | 6 | 0.6 | 0.001 |

| 5b | Southern hypoarctic Kola-Bolshezemelsko-Taz tundra | 6500.8 | 2672.6 | 1 | 41 | 1340.0 | 1 | 204 | 0.1 |

| 11a | Northern West Siberian forest-tundra | 27,947.9 | 3977.9 | 4 | 14 | 445.1 | 1 | 346 | 0.3 |

| 11b | Northern West Siberian northern taiga | 125,261.1 | 12,722.4 | 5 | 10 | 1193.3 | 0.3 | 584 | 0.2 |

| 38.1 | Hypoarctic Polar Ural tundra | 599.6 | 13.7 | 0.1 | 2 | - | - | 26 | 0.2 |

| 41.2 | Hypoarctic Northern Ural tundra | 1491.9 | 47.3 | 1 | 3 | - | - | 2 | 0.03 |

| Biomes Index | Bioms | Tree Cover 2000, sq. km | Forest Loss (2000–2023), sq. km | Forest Loss Share (2000–2023), % | Forest Loss (% of 2000 area) | Open Sand, sq. km | Open Sand Share, % | Built-Up Areas, sq.km | Built-Up Areas Share, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | Taimyr-East Siberian arctic tundra | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 283.2 | 0.5 | 0.3 | <0.01 |

| 6a | Taimyr-Central Siberian northern hypoarctic tundra | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 348.8 | 1 | 0.8 | <0.01 |

| 6b | Taimyr-Central Siberian southern hypoarctic tundra | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 532.6 | 1 | 0.6 | <0.01 |

| 7 | Lena-Kolyma hypoarctic tundra | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 276.6 | 0.2 | 5.2 | <0.01 |

| 12a | Kotui-Lena (Olenyok) forest-tundra | 1735.4 | 51.2 | 0.1 | 3 | 1171.9 | 2.6 | 2.2 | <0.01 |

| 12b | Kotui-Lena (Olenyok) northern taiga | 88,018.6 | 20,930.3 | 6 | 24 | 1903.8 | 0.5 | 30.9 | <0.01 |

| 13a | Nizhnekolymsky forest-tundra | 14,093.4 | 4002.0 | 7 | 28 | 18.3 | 0.03 | 1.1 | <0.01 |

| 13b | Nizhnekolymsky northern taiga | 43,637.1 | 13,301.5 | 11 | 30 | 53.4 | 0.04 | 10 | <0.01 |

| 19 | Middle taiga of Central Yakutia (boreal forests) | 7143.6 | 1935.0 | 13 | 27 | 277.6 | 2 | 1.6 | <0.01 |

| 36 | High Arctic island mountain tundra | - | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | <0.01 |

| 38.3 | Kharaulakh Range middle Siberian Hypoarctic tundra | - | - | 0 | 0 | 12,807 | 23 | 1.9 | <0.01 |

| 39.1 | Chukchi (Beringian, Western Chukchi) hypoarctic tundra | - | - | 0 | 0 | 219.2 | 7.5 | 0 | <0.01 |

| 42.2 | Anabar hypoarctic taiga | 282 | 261.6 | 1 | 93 | 2857 | 12 | 0.3 | <0.01 |

| 43.1 | Verkhoyano-Kolyma (Polousny Range) hypoarctic taiga | 11,419.1 | 3955.3 | 2 | 35 | 16,773.9 | 10 | 5.1 | <0.01 |

| 43.2 | Verkhoyano-Kolyma (Verkhoyano-Yano-Indigirka) hypoarctic taiga | 79,010.2 | 29,480.4 | 8 | 37 | 59,320.3 | 17 | 34.9 | <0.01 |

| 43.3 | Verkhoyano-Kolyma (Oymyakon-Omolon) hypoarctic taiga | 20,030.4 | 6974.7 | 13 | 35 | 439.4 | 0.8 | 0.4 | <0.01 |

References

- Rantanen, M.; Karpechko, A.Y.; Lipponen, A.; Nordling, K.; Hyvarinen, O.; Ruosteenoja, K.; Vihma, T.; Laaksonen, A. The Arctic Has Warmed Nearly Four Times Faster than the Globe since 1979. Commun. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chylek, P.; Folland, C.; Klett, J.D.; Wang, M.; Hengartner, N.; Lesins, G.; Dubey, M.K. Annual Mean Arctic Amplification 1970–2020: Observed and Simulated by CMIP6 Climate Models. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2022, 49, e2022GL099371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, J.M.; Jones, R.G.; Narisma, G.T.; Alves, L.M.; Amjad, M.; Gorodetskaya, I.V.; Grose, M.; Klutse, N.A.B.; Krakovska, S.; Li, J.; et al. Atlas. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1927–2058. [Google Scholar]

- Third Assessment Report on Climate Change and Its Impacts in the Russian Federation. General Summary; Science-Intensive Technologies: St. Petersburg, Russia, 2022; ISBN 978-5-907618-14-5.

- Schuur, E.A.G.; Abbott, B.W.; Commane, R.; Ernakovich, J.; Euskirchen, E.; Hugelius, G.; Grosse, G.; Jones, M.; Koven, C.; Leshyk, V.; et al. Permafrost and Climate Change: Carbon Cycle Feedbacks From the Warming Arctic. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2022, 47, 343–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedlingstein, P.; O’Sullivan, M.; Jones, M.W.; Andrew, R.M.; Hauck, J.; Landschützer, P.; Le Quéré, C.; Li, H.; Luijkx, I.T.; Olsen, A.; et al. Global Carbon Budget 2024. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2025, 17, 965–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, J.; Schirrmeister, L.; Grosse, G.; Fortier, D.; Hugelius, G.; Knoblauch, C.; Romanovsky, V.; Schädel, C.; Von Deimling, T.S.; Schuur, E.A.G.; et al. Deep Yedoma Permafrost: A Synthesis of Depositional Characteristics and Carbon Vulnerability. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2017, 172, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biskaborn, B.K.; Smith, S.L.; Noetzli, J.; Matthes, H.; Vieira, G.; Streletskiy, D.A.; Schoeneich, P.; Romanovsky, V.E.; Lewkowicz, A.G.; Abramov, A.; et al. Permafrost Is Warming at a Global Scale. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuur, E.A.G.; McGuire, A.D.; Schädel, C.; Grosse, G.; Harden, J.W.; Hayes, D.J.; Hugelius, G.; Koven, C.D.; Kuhry, P.; Lawrence, D.M.; et al. Climate Change and the Permafrost Carbon Feedback. Nature 2015, 520, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natali, S.M.; Holdren, J.P.; Rogers, B.M.; Treharne, R.; Duffy, P.B.; Pomerance, R.; MacDonald, E. Permafrost Carbon Feedbacks Threaten Global Climate Goals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2100163118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natali, S.M.; Bronen, R.; Cochran, P.; Holdren, J.P.; Rogers, B.M.; Treharne, R. Incorporating Permafrost into Climate Mitigation and Adaptation Policy. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 091001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, A.D.; Christensen, T.R.; Hayes, D.; Heroult, A.; Euskirchen, E.; Kimball, J.S.; Koven, C.; Lafleur, P.; Miller, P.A.; Oechel, W.; et al. An Assessment of the Carbon Balance of Arctic Tundra: Comparisons among Observations, Process Models, and Atmospheric Inversions. Biogeosciences 2012, 9, 3185–3204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virkkala, A.-M.; Rogers, B.M.; Watts, J.D.; Arndt, K.A.; Potter, S.; Wargowsky, I.; Schuur, E.A.G.; See, C.R.; Mauritz, M.; Boike, J.; et al. Wildfires Offset the Increasing but Spatially Heterogeneous Arctic–Boreal CO2 Uptake. Nat. Clim. Change 2025, 15, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- See, C.R.; Virkkala, A.-M.; Natali, S.M.; Rogers, B.M.; Mauritz, M.; Biasi, C.; Bokhorst, S.; Boike, J.; Bret-Harte, M.S.; Celis, G.; et al. Decadal Increases in Carbon Uptake Offset by Respiratory Losses across Northern Permafrost Ecosystems. Nat. Clim. Change 2024, 14, 853–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, P.; Storelvmo, T.; Armour, K.; Collins, W.; Dufresne, J.-L.; Frame, D.; Lunt, D.J.; Mauritsen, T.; Palmer, M.D.; Watanabe, M.; et al. The Earth’s Energy Budget, Climate Feedbacks, and Climate Sensitivity. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 923–1054. [Google Scholar]

- Parmentier, F.-J.W.; Thornton, B.F.; Silyakova, A.; Christensen, T.R. Vulnerability of Arctic-Boreal Methane Emissions to Climate Change. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1460155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, K.; Li, F.; McNicol, G.; Chen, M.; Hoyt, A.; Knox, S.; Riley, W.J.; Jackson, R.; Zhu, Q. Boreal–Arctic Wetland Methane Emissions Modulated by Warming and Vegetation Activity. Nat. Clim. Change 2024, 14, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteman, G.; Hope, C.; Wadhams, P. Vast Costs of Arctic Change. Nature 2013, 499, 401–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anisimov, O.; Zimov, S. Thawing Permafrost and Methane Emission in Siberia: Synthesis of Observations, Reanalysis, and Predictive Modeling. Ambio 2021, 50, 2050–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Y.; Zhuang, Q.; Liu, L.; Welp, L.R.; Lau, M.C.Y.; Onstott, T.C.; Medvigy, D.; Bruhwiler, L.; Dlugokencky, E.J.; Hugelius, G.; et al. Reduced Net Methane Emissions Due to Microbial Methane Oxidation in a Warmer Arctic. Nat. Clim. Change 2020, 10, 317–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, C.; Virkkala, A.-M.; Gosselin, G.H.; Bennett, K.A.; Black, T.A.; Detto, M.; Chevrier-Dion, C.; Guggenberger, G.; Hashmi, W.; Kohl, L.; et al. Arctic Soil Methane Sink Increases with Drier Conditions and Higher Ecosystem Respiration. Nat. Clim. Change 2023, 13, 1095–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz, S.; Malhi, Y. Biodiversity: Concepts, Patterns, Trends, and Perspectives. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2022, 47, 31–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinale, B.J.; Duffy, J.E.; Gonzalez, A.; Hooper, D.U.; Perrings, C.; Venail, P.; Narwani, A.; Mace, G.M.; Tilman, D.; Wardle, D.A.; et al. Biodiversity Loss and Its Impact on Humanity. Nature 2012, 486, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, D.U.; Adair, E.C.; Cardinale, B.J.; Byrnes, J.E.K.; Hungate, B.A.; Matulich, K.L.; Gonzalez, A.; Duffy, J.E.; Gamfeldt, L.; O’Connor, M.I. A Global Synthesis Reveals Biodiversity Loss as a Major Driver of Ecosystem Change. Nature 2012, 486, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, S.; Bernier, P.; Kuuluvainen, T.; Shvidenko, A.Z.; Schepaschenko, D.G. Boreal Forest Health and Global Change. Science 2015, 349, 819–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, A.S.; Dee, L.E.; Gonzalez, A.; Ohashi, H.; Cowles, J.; Wright, A.J.; Loreau, M.; Hautier, Y.; Newbold, T.; Reich, P.B.; et al. Biodiversity–Productivity Relationships Are Key to Nature-Based Climate Solutions. Nat. Clim. Change 2021, 11, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marañón-Jiménez, S.; Luo, X.; Richter, A.; Gündler, P.; Fuchslueger, L.; Verbrigghe, N.; Poeplau, C.; Sigurdsson, B.D.; Janssens, I.; Peñuelas, J. Warming Weakens Soil Nitrogen Stabilization Pathways Driving Proportional Carbon Losses in Subarctic Ecosystems. Glob. Change Biol. 2025, 31, e70309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, M.; Jones, T.G.; Ford, H.; Hill, P.W.; Jones, D.L. Life in the Dark: Impact of Future Winter Warming Scenarios on Carbon and Nitrogen Cycling in Arctic Soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2023, 186, 109184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers-Smith, I.H.; Elmendorf, S.C.; Beck, P.S.A.; Wilmking, M.; Hallinger, M.; Blok, D.; Tape, K.D.; Rayback, S.A.; Macias-Fauria, M.; Forbes, B.C.; et al. Climate Sensitivity of Shrub Growth across the Tundra Biome. Nat. Clim. Change 2015, 5, 887–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, Z.A.; Riley, W.J.; Berner, L.T.; Bouskill, N.J.; Torn, M.S.; Iwahana, G.; Breen, A.L.; Myers-Smith, I.H.; Criado, M.G.; Liu, Y.; et al. Arctic Tundra Shrubification: A Review of Mechanisms and Impacts on Ecosystem Carbon Balance. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 053001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markley, P.T.; Gross, C.P.; Daru, B.H. The Changing Biodiversity of the Arctic Flora in the Anthropocene. Am. J. Bot. 2025, 112, e16466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasowicz, P.; Sennikov, A.N.; Westergaard, K.B.; Spellman, K.; Carlson, M.; Gillespie, L.J.; Saarela, J.M.; Seefeldt, S.S.; Bennett, B.; Bay, C.; et al. Non-Native Vascular Flora of the Arctic: Taxonomic Richness, Distribution and Pathways. Ambio 2020, 49, 693–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rew, L.J.; McDougall, K.L.; Alexander, J.M.; Daehler, C.C.; Essl, F.; Haider, S.; Kueffer, C.; Lenoir, J.; Milbau, A.; Nuñez, M.A.; et al. Moving up and over: Redistribution of Plants in Alpine, Arctic, and Antarctic Ecosystems under Global Change. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 2020, 52, 651–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemieux, T.A.; Coles, J.D.R.; Haley, A.L.; LaFlamme, M.L.; Steel, S.K.; Scott, K.M.; Provencher, J.F.; Price, C.; Bennett, J.R.; Barrio, I.C.; et al. Persistent and Emerging Threats to Arctic Biodiversity and Ways to Overcome Them: A Horizon Scan. Arct. Sci. 2025, 11, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J.D.; Pearce, T.; Canosa, I.V.; Harper, S. The Rapidly Changing Arctic and Its Societal Implications. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.-Clim. Change 2021, 12, e735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjort, J.; Streletskiy, D.; Doré, G.; Wu, Q.; Bjella, K.; Luoto, M. Impacts of Permafrost Degradation on Infrastructure. Nat. Rev. Earth Env. 2022, 3, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnikov, V.P.; Osipov, V.I.; Brouchkov, A.V.; Falaleeva, A.A.; Badina, S.V.; Zheleznyak, M.N.; Sadurtdinov, M.R.; Ostrakov, N.A.; Drozdov, D.S.; Osokin, A.B.; et al. Climate Warming and Permafrost Thaw in the Russian Arctic: Potential Economic Impacts on Public Infrastructure by 2050. Nat Hazards 2022, 112, 231–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waits, A.; Emelyanova, A.; Oksanen, A.; Abass, K.; Rautio, A. Human Infectious Diseases and the Changing Climate in the Arctic. Environ. Int. 2018, 121, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omazic, A.; Bylund, H.; Boqvist, S.; Högberg, A.; Björkman, C.; Tryland, M.; Evengård, B.; Koch, A.; Berggren, C.; Malogolovkin, A.; et al. Identifying Climate-Sensitive Infectious Diseases in Animals and Humans in Northern Regions. Acta Vet. Scand. 2019, 61, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonova, E.G.; Kartavaya, S.A.; Titkov, A.V.; Loktionova, M.N.; Raichich, S.R.; Tolpin, V.A.; Lupyan, E.A.; Platonov, A.E. Anthrax in the Territory of Yamal: Assessment of Epizootiological and Epidemiological Risks. Probl. Osob. Opasnykh Infektsii 2017, 1, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Security Council of the Russian Federation. Strategy for the Development of the Arctic Zone of the Russian Federation and National Security for the Period up to 2035. Approved by Decree of the President of the Russian Federation No. 645. (26 October 2020). Available online: http://www.scrf.gov.ru/media/files/file/hcTiEHnCdn6TqRm5A677n5iE3yXLi93E.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Streletskiy, D.A.; Suter, L.J.; Shiklomanov, N.I.; Porfiriev, B.N.; Eliseev, D.O. Assessment of Climate Change Impacts on Buildings, Structures and Infrastructure in the Russian Regions on Permafrost. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 025003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN. International Union for Conservation of Nature IUCN Global Standard for Nature-Based Solutions: A User-Friendly Framework for the Verification, Design and Scaling up of NbS: First Edition, 1st ed.; IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature: Gland, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 978-2-8317-2058-6. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, B.A.; Kumar, P.; Okano, N.; Dasgupta, R.; Shivakoti, B.R. Nature-Based Solutions for Climate Change Adaptation: A Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews. Nat. Based Solut. 2022, 2, 100042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, P.W.; Page, A.M.; Wood, S.; Fargione, J.; Masuda, Y.J.; Denney, V.C.; Moore, C.; Kroeger, T.; Griscom, B.; Sanderman, J.; et al. The Principles of Natural Climate Solutions. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook-Patton, S.C.; Drever, C.R.; Griscom, B.W.; Hamrick, K.; Hardman, H.; Kroeger, T.; Pacheco, P.; Raghav, S.; Stevenson, M.; Webb, C.; et al. Protect, Manage and Then Restore Lands for Climate Mitigation. Nat. Clim. Change 2021, 11, 1027–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griscom, B.W.; Adams, J.; Ellis, P.W.; Houghton, R.A.; Lomax, G.; Miteva, D.A.; Schlesinger, W.H.; Shoch, D.; Siikamäki, J.V.; Smith, P.; et al. Natural Climate Solutions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 11645–11650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seddon, N.; Turner, B.; Berry, P.; Chausson, A.; Girardin, C.A.J. Grounding Nature-Based Climate Solutions in Sound Biodiversity Science. Nat. Clim. Change 2019, 9, 84–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corlett, R.T. The Anthropocene Concept in Ecology and Conservation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2015, 30, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.H.; Erbaugh, J.T.; Fajardo, P.; Lu, L.; Molnár, I.; Papp, D.; Robinson, B.E.; Austin, K.G.; Castro, M.; Cheng, S.H.; et al. Global Evidence of Human Well-Being and Biodiversity Impacts of Natural Climate Solutions. Nat. Sustain. 2024, 8, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanovskaya, A.A. Approaches to Implementing Ecosystem Climate Projects in Russia. Izv. Ross. Akad. nauk. Seriâ Geogr. 2023, 87, 463–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drever, C.R.; Cook-Patton, S.C.; Akhter, F.; Badiou, P.H.; Chmura, G.L.; Davidson, S.J.; Desjardins, R.L.; Dyk, A.; Fargione, J.E.; Fellows, M.; et al. Natural Climate Solutions for Canada. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabd6034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, G.P.; Hamilton, S.K.; Paustian, K.; Smith, P. Land-Based Climate Solutions for the United States. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2022, 28, 4912–4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wijngaarden, A.; Moore, J.C.; Alfthan, B.; Kurvits, T.; Kullerud, L. A Survey of Interventions to Actively Conserve the Frozen North. Clim. Change 2024, 177, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catonini, F.; Buerkert, J.S.; Kristensen, K.S. Arctic Geoengineering Between Governance and Science: A Structured Literature Review of the Arctic Geoengineering Discourse. WIREs Energy Amp Environ. 2025, 14, e70008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AMAP. AMAP Arctic Climate Change Update 2024: Key Trends and Impacts; Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP): Tromsø, Norway, 2024; ISBN 978-82-7971-203-9. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J. Informetr. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogureeva, G.N.; Leonova, N.B.; Buldakova, E.V.; Kadetov, N.G.; Arkhipova, M.V.; Miklyaeva, I.M.; Bocharnikov, M.V.; Dudov, S.V.; Ignatova, E.A.; Ignatov, M.S.; et al. The Biomes of Russia. Map. Scale 1:7,500,00. Second Revised Edition. 2018. Available online: https://www.elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=36725020 (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Hansen, M.C.; Potapov, P.V.; Moore, R.; Hancher, M.; Turubanova, S.A.; Tyukavina, A.; Thau, D.; Stehman, S.V.; Goetz, S.J.; Loveland, T.R.; et al. High-Resolution Global Maps of 21st-Century Forest Cover Change. Science 2013, 342, 850–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyukavina, A.; Potapov, P.; Hansen, M.C.; Pickens, A.H.; Stehman, S.V.; Turubanova, S.; Parker, D.; Zalles, V.; Lima, A.; Kommareddy, I.; et al. Global Trends of Forest Loss Due to Fire From 2001 to 2019. Front. Remote Sens. 2022, 3, 825190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potapov, P.; Hansen, M.C.; Pickens, A.; Hernandez-Serna, A.; Tyukavina, A.; Turubanova, S.; Zalles, V.; Li, X.; Khan, A.; Stolle, F.; et al. The Global 2000–2020 Land Cover and Land Use Change Dataset Derived from the Landsat Archive: First Results. Front. Remote Sens. 2022, 3, 856903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obu, J.; Westermann, S.; Bartsch, A.; Berdnikov, N.; Christiansen, H.H.; Dashtseren, A.; Delaloye, R.; Elberling, B.; Etzelmüller, B.; Kholodov, A.; et al. Northern Hemisphere Permafrost Map Based on TTOP Modelling for 2000–2016 at 1 Km2 Scale. Earth Sci. Rev. 2019, 193, 299–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijmans, R. Terra: Spatial Data Analysis. R Package Version 1.8-29. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=terra (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Baston, D. Exactextractr: Fast Extraction from Raster Datasets Using Polygons. R Package Version 0.9.1. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=exactextractr (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Shvarts, E.A.; Ptichnikov, A.V.; Romanovskaya, A.A.; Korotkov, V.N.; Baybar, A.S. The Low-Carbon Development Strategy of Russia Until 2050 and the Role of Forests in Its Implementation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurtsev, B.A. Problems of botanical geography of the North-East Asia; Nauka: Leningrad, Russia, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Schepaschenko, D.G.; Shvidenko, A.Z.; Shalaev, V.S. Biological Productivity and Carbon Budget of Larch Forests of Northern-East Russia; Moscow State Forest University: Moscow, Russia, 2008; ISBN 978-5-8135-0443. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, A.V.; Neumann, M.; Darman, G.F.; Danilov, A.V.; Susloparova, E.S.; Solovyov, I.D.; Kravchenko, O.M.; Smuskina, I.N.; Bryanin, S. Vulnerability of Larch Forests to Forest Fires along a Latitudinal Gradient in Eastern Siberia. Can. J. For. Res. 2022, 52, 1543–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers-Smith, I.H.; Kerby, J.T.; Phoenix, G.K.; Bjerke, J.W.; Epstein, H.E.; Assmann, J.J.; John, C.; Andreu-Hayles, L.; Angers-Blondin, S.; Beck, P.S.A.; et al. Complexity Revealed in the Greening of the Arctic. Nat. Clim. Change 2020, 10, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berner, L.T.; Goetz, S.J. Satellite Observations Document Trends Consistent with a Boreal Forest Biome Shift. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2022, 28, 3275–3292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, T.C.; Subke, J.; Wookey, P.A. Rapid Carbon Turnover beneath Shrub and Tree Vegetation Is Associated with Low Soil Carbon Stocks at a Subarctic Treeline. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2015, 21, 2070–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharuk, V.I.; Kasischke, E.S.; Yakubailik, O.E. The Spatial and Temporal Distribution of Fires on Sakhalin Island, Russia. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2007, 16, 556–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamet, S.D.; Brown, C.D.; Trant, A.J.; Laroque, C.P. Shifting Global Larix Distributions: Northern Expansion and Southern Retraction as Species Respond to Changing Climate. J. Biogeogr. 2019, 46, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Forest Institute. Russian Forests and Climate Change; European Forest Institute, Leskinen, P., Lindner, M., Verkerk, P.J., Nabuurs, G.-J., Van Brusselen, J., Kulikova, E., Hassegawa, M., Lerink, B., Eds.; What Science Can Tell Us; European Forest Institute: Joensuu, Finland, 2020; Volume 11, ISBN 978-952-7426-00-5. [Google Scholar]

- Loranty, M.M.; Berner, L.T.; Taber, E.D.; Kropp, H.; Natali, S.M.; Alexander, H.D.; Davydov, S.P.; Zimov, N.S. Understory Vegetation Mediates Permafrost Active Layer Dynamics and Carbon Dioxide Fluxes in Open-Canopy Larch Forests of Northeastern Siberia. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, S.J.; Sloan, V.L.; Phoenix, G.K.; Wagner, R.; Fisher, J.P.; Oechel, W.C.; Zona, D. Vegetation Type Dominates the Spatial Variability in CH4 Emissions Across Multiple Arctic Tundra Landscapes. Ecosystems 2016, 19, 1116–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köster, K.; Aaltonen, H.; Köster, E.; Berninger, F.; Pumpanen, J. Post-Fire Soil Carbon Emission Rates along Boreal Forest Fire Chronosequences in Northwest Canada Show Significantly Higher Emission Potentials from Permafrost Soils Compared to Non-Permafrost Soils. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 11, 1331018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talucci, A.C.; Loranty, M.M.; Holloway, J.E.; Rogers, B.M.; Alexander, H.D.; Baillargeon, N.; Baltzer, J.L.; Berner, L.T.; Breen, A.; Brodt, L.; et al. Permafrost–Wildfire Interactions: Active Layer Thickness Estimates for Paired Burned and Unburned Sites in Northern High Latitudes. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2025, 17, 2887–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, H.D.; Natali, S.M.; Loranty, M.M.; Ludwig, S.M.; Spektor, V.V.; Davydov, S.; Zimov, N.; Trujillo, I.; Mack, M.C. Impacts of Increased Soil Burn Severity on Larch Forest Regeneration on Permafrost Soils of Far Northeastern Siberia. For. Ecol. Manag. 2018, 417, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, A.V.; Shaver, G.R. Postfire Energy Exchange in Arctic Tundra: The Importance and Climatic Implications of Burn Severity. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2011, 17, 2831–2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, H.B.; Smith, S.L.; Burn, C.R.; Duchesne, C.; Zhang, Y. Widespread Permafrost Degradation and Thaw Subsidence in Northwest Canada. JGR Earth Surf. 2023, 128, e2023JF007262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Painter, S.L.; Coon, E.T.; Khattak, A.J.; Jastrow, J.D. Drying of Tundra Landscapes Will Limit Subsidence-Induced Acceleration of Permafrost Thaw. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2212171120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwahana, G.; Harada, K.; Uchida, M.; Tsuyuzaki, S.; Saito, K.; Narita, K.; Kushida, K.; Hinzman, L.D. Geomorphological and Geochemistry Changes in Permafrost after the 2002 Tundra Wildfire in Kougarok, Seward Peninsula, Alaska. JGR Earth Surf. 2016, 121, 1697–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sizov, O.; Ezhova, E.; Tsymbarovich, P.; Soromotin, A.; Prihod’ko, N.; Petäjä, T.; Zilitinkevich, S.; Kulmala, M.; Bäck, J.; Köster, K. Fire and Vegetation Dynamics in Northwest Siberia during the Last 60 Years Based on High-Resolution Remote Sensing. Biogeosciences 2021, 18, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berner, L.T.; Beck, P.S.A.; Bunn, A.G.; Goetz, S.J. Plant Response to Climate Change along the Forest-tundra Ecotone in Northeastern Siberia. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2013, 19, 3449–3462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loginov, V.G.; Ignatyeva, M.N.; Naumov, I.V. Reindeer Husbandry as a Basic Sector of the Traditional Economy of Indigenous Ethnic Groups: Present and Future. Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2022, 14, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klokov, K.B. Geographical Variability and Cultural Diversity of Reindeer Pastoralism in Northern Russia: Delimitation of Areas with Different Types of Reindeer Husbandry. Pastoralism 2023, 13, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golovnev, A.V.; Kukanov, D.A.; Perevalova, E.V. Arctic: Atlas of Nomadic Technologies; MAE RAS Publication: St. Petersburg, Russia, 2018; ISBN 978-5-88431-359-0. [Google Scholar]

- Koltz, A.M.; Gough, L.; McLaren, J.R. Herbivores in Arctic Ecosystems: Effects of Climate Change and Implications for Carbon and Nutrient Cycling. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2022, 1516, 28–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernes, C.; Bråthen, K.A.; Forbes, B.C.; Speed, J.D.; Moen, J. What Are the Impacts of Reindeer/Caribou (Rangifer Tarandus L.) on Arctic and Alpine Vegetation? A Systematic Review. Env. Evid. 2015, 4, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köster, K.; Berninger, F.; Köster, E.; Pumpanen, J. Influences of Reindeer Grazing on Above- and Belowground Biomass and Soil Carbon Dynamics. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 2015, 47, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, S.; Männistö, M.K.; Ganzert, L.; Tiirola, M.; Häggblom, M.M. Grazing Intensity in Subarctic Tundra Affects the Temperature Adaptation of Soil Microbial Communities. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2015, 84, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimonenko, E.; Uporova, M.; Dimitryuk, E.; Samokhina, N.; Ge, T.; Aloufi, A.S.; Prikhodko, N.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Soromotin, A. Effects of Reindeer Grazing on Thermal Stability of Organic Matter in Topsoil in Arctic Tundra. Catena 2025, 254, 108928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köster, K.; Köster, E.; Berninger, F.; Heinonsalo, J.; Pumpanen, J. Contrasting Effects of Reindeer Grazing on CO2, CH4, and N2 O Fluxes Originating from the Northern Boreal Forest Floor. Land. Degrad. Dev. 2018, 29, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossio, D.A.; Cook-Patton, S.C.; Ellis, P.W.; Fargione, J.; Sanderman, J.; Smith, P.; Wood, S.; Zomer, R.J.; von Unger, M.; Emmer, I.M.; et al. The Role of Soil Carbon in Natural Climate Solutions. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, S.; Cromsigt, J.P.G.M.; te Beest, M.; Chen, J.; Roy, D.P.; Hawkins, H.; Kerley, G.I.H. Grassland Albedo as a Nature-Based Climate Prospect: The Role of Growth Form and Grazing. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 124004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Terrer, C.; Li, J.; Cao, Y.; Yang, S.; Liu, D. Historical Impacts of Grazing on Carbon Stocks and Climate Mitigation Opportunities. Nat. Clim. Change 2024, 14, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Wang, T.; Ji, X.; Wei, L.; Wei, J.; Cao, Y.; Ding, J. Grazing Reverses Climate-Induced Soil Carbon Gains on the Tibetan Plateau. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 6978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellison, L. Influence of Grazing on Plant Succession of Rangelands. Bot. Rev. 1960, 26, 1–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNaughton, S.J. Grazing as an Optimization Process: Grass-Ungulate Relationships in the Serengeti. Am. Nat. 1979, 113, 691–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.H.; Strickland, M.S.; Hutchings, J.A.; Bianchi, T.S.; Flory, S.L. Grazing Enhances Belowground Carbon Allocation, Microbial Biomass, and Soil Carbon in a Subtropical Grassland. Glob. Change Biol. 2018, 24, 2997–3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Te Beest, M.; Sitters, J.; Ménard, C.B.; Olofsson, J. Reindeer Grazing Increases Summer Albedo by Reducing Shrub Abundance in Arctic Tundra. Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 125013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golovatin, M.G.; Morozova, L.M.; Ektova, S.N. Effect of Reindeer Overgrazing on Vegetation and Animals of Tundra Ecosystems of the Yamal Peninsula. Czech Polar Rep. 2012, 2, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podkorytov, F.M. Problems of Reindeer Herding in Yamal. In Science to Reindeer Herding; Publishing House “Nauka”, Siberian Branch: Novosibirsk, Russia, 2005; Volume 2, pp. 102–104. [Google Scholar]

- Mukhachev, A.D. Yamal Reindeer Breeding. In Agrarian Science—Agricultural Production in Siberia, Mongolia, Kazakhstan and Bulgaria; IIC SSAESB SBAAAS: Novosibirsk, Russia, 2014; Volume 2, pp. 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Loginov, V.G. A Methodological Approach to the Economic Assessment of the Resource Potential of the Tundra Pastures of Yamal. Agrar. Bull. Ural. 2012, 10, 68–70. [Google Scholar]

- Ermokhina, K.A. Geobotanical Assessment of Reindeer Pastures in the Yamal and Taz Regions of the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug. In Collection of Materials from Proceedings of the Legislative Assembly of the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug; Northern Publishing House: Salekhard, Russia, 2018; pp. 8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Volkovitskiy, A.; Terekhina, A. The contemporary issues of Yamal reindeer herding discussions and perspectives. Etnografia 2020, 8, 152–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmus, S.; Horstkotte, T.; Turunen, M.; Landauer, M.; Löf, A.; Lehtonen, I.; Rosqvist, G.; Holand, Ø. Reindeer Husbandry and Climate Change. In Reindeer Husbandry and Global Environmental Change; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 99–117. ISBN 978-1-003-11856-5. [Google Scholar]

- Rozenfeld, S.B.; Kirtaev, G.V. Necessity of Creation a Network of Seasonal Protected Natural Areas to Preserve Migratory Waterfowl. In Contribution of the Arkhangelsk Region Protected Natural Areas to the Preservation of Natural and Cultural Heritage: Proceedings of the Interregional Conference; FCIARctic: Arkhangelsk, Russia, 2017; pp. 186–191. [Google Scholar]

- Severtsov, A.N.; Rozenfeld, S.B.; Kirtaev, G.V.; Rogova, N.V.; Soloviev, M.Y.; Gorchakovsky, A.A.; Bizin, M.S.; Demianets, S.S. Estimation of the Populations Status and Habitat Conditions of Anseriformes in the State Nature Reserve «Gydansky» (Russia) Using Ultralight Aviation. Nat. Conserv. Res. 2018, 3, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morozova, L.M.; Ektova, S.N. Desertification of Tundra Ecosystems of the Yamal Peninsula. In Materials of the Regional Scientific Conference «Mamaev Readings»; OOO “UIPC”: Ekaterinburg, Russia, 2012; pp. 110–114. ISBN 978-5-4430-0017-6. [Google Scholar]

- Kopceva, E.M. Natural Restoration of Vegetation in Man-Made Habitats of the Far North (Yamal Sector of the Arctic). Ph.D. Dissertation, St. Petersburg State University, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 2005. Available online: https://search.rsl.ru/ru/record/01002832115 (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Ektova, S.N.; Morozova, L.M. Rate of Recovery of Lichen-Dominated Tundra Vegetation after Overgrazing at the Yamal Peninsula (Short Communication). Czech Polar Rep. 2015, 5, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, I. Reindeer in a Desert (Desertification in the Arctic Because of Overgrazing). Polar Sci. 2025, 101234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anisimov, O.A.; Anokhin, Y.A.; Lavrov, S.A.; Malkova, G.V.; Myach, L.T.; Pavlov, A.V.; Romanovskij, V.A.; Streleczkij, D.A.; Kholodov, A.L.; Shiklomanov, N.I. Continental Permafrost. In Assessing Methods of the Climate Change Consequences for Physical and Biological Systems; Roshydromet: Moscow, Russia, 2012; pp. 301–359. ISBN 978-5-904206-10-9. [Google Scholar]

- Kuklina, V.; Sizov, O.; Fedorov, R.; Butakov, D. Dealing with Sand in the Arctic City of Nadym. Ambio 2023, 52, 1198–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, M.; Bühne, H.S.T.; Lopes, M.; Ehrich, D.; Sokovnina, S.; Hofhuis, S.P.; Pettorelli, N. Can Reindeer Husbandry Management Slow down the Shrubification of the Arctic? J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 267, 110636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, B.C.; Stammler, F.; Kumpula, T.; Meschtyb, N.; Pajunen, A.; Kaarlejärvi, E. High Resilience in the Yamal-Nenets Social–Ecological System, West Siberian Arctic, Russia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 22041–22048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutillod, C.; Buisson, É.; Mahy, G.; Jaunatre, R.; Bullock, J.M.; Tatin, L.; Dutoit, T. Ecological Restoration and Rewilding: Two Approaches with Complementary Goals? Biol. Rev. 2024, 99, 820–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, O.J.; Sylvén, M.; Atwood, T.B.; Bakker, E.S.; Berzaghi, F.; Brodie, J.F.; Cromsigt, J.P.G.M.; Davies, A.B.; Leroux, S.J.; Schepers, F.J.; et al. Trophic Rewilding Can Expand Natural Climate Solutions. Nat. Clim. Change 2023, 13, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandom, C.J.; Middleton, O.; Lundgren, E.; Rowan, J.; Schowanek, S.D.; Svenning, J.-C.; Faurby, S. Trophic Rewilding Presents Regionally Specific Opportunities for Mitigating Climate Change. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2020, 375, 20190125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trepel, J.; Le Roux, E.; Abraham, A.J.; Buitenwerf, R.; Kamp, J.; Kristensen, J.A.; Tietje, M.; Lundgren, E.J.; Svenning, J.-C. Meta-Analysis Shows That Wild Large Herbivores Shape Ecosystem Properties and Promote Spatial Heterogeneity. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 8, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofsson, J.; Post, E. Effects of Large Herbivores on Tundra Vegetation in a Changing Climate, and Implications for Rewilding. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2018, 373, 20170437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimov, S.A. Pleistocene Park: Return of the Mammoth’s Ecosystem. Science 2005, 308, 796–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimov, S.A.; Zimov, N.S.; Tikhonov, A.N.; Chapin, F.S. Mammoth Steppe: A High-Productivity Phenomenon. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2012, 57, 26–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, W.; Thomas, C.K.; Zimov, N.; Göckede, M. Grazing Enhances Carbon Cycling but Reduces Methane Emission during Peak Growing Season in the Siberian Pleistocene Park Tundra Site. Biogeosciences 2022, 19, 1611–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windirsch, T.; Grosse, G.; Ulrich, M.; Forbes, B.C.; Göckede, M.; Wolter, J.; Macias-Fauria, M.; Olofsson, J.; Zimov, N.; Strauss, J. Large Herbivores on Permafrost—A Pilot Study of Grazing Impacts on Permafrost Soil Carbon Storage in Northeastern Siberia. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 893478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, C.; Zimov, N.; Olofsson, J.; Porada, P.; Zimov, S. Protection of Permafrost Soils from Thawing by Increasing Herbivore Density. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borisyuk, V.N. Reintroduction of the Musk Ox in the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug. Sci. Bull. Arct. 2019, 6, 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Mosbacher, J.B.; Kristensen, D.K.; Michelsen, A.; Stelvig, M.; Schmidt, N.M. Quantifying Muskox Plant Biomass Removal and Spatial Relocation of Nitrogen in a High Arctic Tundra Ecosystem. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 2016, 48, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosbacher, J.B.; Michelsen, A.; Stelvig, M.; Hjermstad-Sollerud, H.; Schmidt, N.M. Muskoxen Modify Plant Abundance, Phenology, and Nitrogen Dynamics in a High Arctic Fen. Ecosystems 2019, 22, 1095–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheremetev, I.S.; Rozenfeld, S.B.; Sipko, T.P.; Gruzdev, A.R. Extinction of Large Herbivore Mammals: Niche Characteristics of the Musk Ox Ovibos Moschatus and the Reindeer Rangifer tarandus Coexisting in Isolation. Biol. Bull. Rev. 2014, 4, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buma, B.; Gordon, D.R.; Kleisner, K.M.; Bartuska, A.; Bidlack, A.; DeFries, R.; Ellis, P.; Friedlingstein, P.; Metzger, S.; Morgan, G.; et al. Expert Review of the Science Underlying Nature-Based Climate Solutions. Nat. Clim. Change 2024, 14, 402–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gann, G.D.; McDonald, T.; Walder, B.; Aronson, J.; Nelson, C.R.; Jonson, J.; Hallett, J.G.; Eisenberg, C.; Guariguata, M.R.; Liu, J.; et al. International Principles and Standards for the Practice of Ecological Restoration. Second Edition. Restor. Ecol. 2019, 27, S1–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavrinenko, I.A. Map of Technogenic Disturbance of Nenets Autonomous District. Sovr. Probl. DZZ Kosm. 2018, 15, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magomedova, M.A.; Morozova, L.M.; Ektova, S.N.; Rebristaya, O.V.; Chernyadyeva, I.V.; Potemkin, A.D.; Knyazev, M.S. Yamal Peninsula: Plant Cover; City-Press: Tyumen, Russia, 2006; ISBN 978-5-98100-074-4. [Google Scholar]

- Raynolds, M.K.; Walker, D.A.; Ambrosius, K.J.; Brown, J.; Everett, K.R.; Kanevskiy, M.; Kofinas, G.P.; Romanovsky, V.E.; Shur, Y.; Webber, P.J. Cumulative Geoecological Effects of 62 Years of Infrastructure and Climate Change in Ice-rich Permafrost Landscapes, Prudhoe Bay Oilfield, Alaska. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2014, 20, 1211–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, D.; Walker, M. History and Pattern of Disturbance in Alaskan Arctic Terrestrial Ecosystems: A Hierarchical Approach to Analysing Landscape Change. J. Appl. Ecol. 1991, 28, 244–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, D.A.; Cate, D.; Brown, J.; Racine, C. Disturbance and Recovery of Arctic Alascan Tundra Terrain: A Review of Recent Investigations. CRREL Report 87–11.; Cold Regions Research & Engineering Laboratory: Hanover, NH, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Zamolodchikov, D.G.; Minayeva, T.Y.; Pechkin, A.S. The Impact of Anthropogenic Activity on the Northern Yamal Soils CO2-Gas Exchange. In Soils—Strategic Resource of Russia; Abstracts of VIII Congress of the V.V. Dokuchaev Society of Soil Scientists and the School of Young Scientists on Soil Morphology and Classification Reports; IB FRC Komi SC UB RAS: Moscow-Syktyvkar, Russia, 2021; pp. 667–668. [Google Scholar]

- Neby, M.; Semenchuk, P.; Neby, E.; Cooper, E.J. Comparison of Methods for Revegetation of Vehicle Tracks in High Arctic Tundra on Svalbard. Arct. Sci. 2022, 8, 1006–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minayeva, T.Y.; Avetov, N.A.; Bolshakov, R.G.; Bragg, O.; Golubeva, S.G.; Kirilov, A.G.; Lavrinenko, I.A.; Lavrinenko, O.V.; Lobanova, E.A.; Mizin, I.A.; et al. Ecological Restoration in Arctic: Review of the International and Russian Practices; Triada: Syktyvkar, Russia; Naryan-Mar, Russia, 2016; ISBN 978-5-94789-751-7. [Google Scholar]

- Vloon, C.C.; Evju, M.; Klanderud, K.; Hagen, D. Alpine Restoration: Planting and Seeding of Native Species Facilitate Vegetation Recovery. Restor. Ecol. 2022, 30, e13479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirazi, M.A.; Haggerty, P.K.; Hendricks, C.W.; Reporter, M. The Role of Thermal Regime in Tundra Plant Community Restoration. Restor. Ecol. 1998, 6, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hnatowich, I.G.; Lamb, E.G.; Stewart, K.J. Reintroducing Vascular and Non-Vascular Plants to Disturbed Arctic Sites: Investigating Turfs and Turf Fragments. Ecol. Rest. 2023, 41, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hnatowich, I.G.; Lamb, E.G.; Stewart, K.J. Vegetative Growth and Belowground Expansion from Transplanted Low-arctic Tundra Turfs. Restor. Ecol. 2023, 31, e13716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamarre, J.J.; Dhar, A.; Naeth, M.A. Arctic Ecosystem Restoration with Native Tundra Bryophytes. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 2023, 55, 2209394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letendre, A.-C.; Coxson, D.S.; Stewart, K.J. Restoration of Ecosystem Function by Soil Surface Inoculation with Biocrust in Mesic and Xeric Alpine Ecosystems. Ecol. Rest. 2019, 37, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ficko, S.; Haughland, D.; Naeth, M. Assisted Dispersal and Retention of Lichen-Dominated Biocrust Material for Arctic Restoration. Restor. Ecol. 2023, 31, e13793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longton, R.E. The Role of Bryophytes and Lichens in Polar Ecosystems. Spec. Publ. Br. Ecol. Soc. 1997, 13, 69–96. [Google Scholar]

- Agnelli, A.; Corti, G.; Massaccesi, L.; Ventura, S.; D’Acqui, L.P. Impact of Biological Crusts on Soil Formation in Polar Ecosystems. Geoderma 2021, 401, 115340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finne, E.A.; Bjerke, J.W.; Erlandsson, R.; Tømmervik, H.; Stordal, F.; Tallaksen, L.M. Variation in Albedo and Other Vegetation Characteristics in Non-Forested Northern Ecosystems: The Role of Lichens and Mosses. Environ. Res. Lett. 2023, 18, 074038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, P.; Briegel-Williams, L.; Simon, A.; Thyssen, A.; Büdel, B. Uncovering Biological Soil Crusts: Carbon Content and Structure of Intact Arctic, Antarctic and Alpine Biological Soil Crusts. Biogeosciences 2018, 15, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleary, K.G.; Xia, Z.; Yu, Z. The Growth and Carbon Sink of Tundra Peat Patches in Arctic Alaska. JGR Biogeosci. 2024, 129, e2023JG007890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Bu, C.; Wu, S.; Siddique, K.H.M. Lichen Biocrusts Contribute to Soil Microbial Biomass Carbon in the Northern Temperate Zone: A Meta-analysis. Eur. J. Soil. Sci. 2024, 75, e13517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Q.; Li, C. Development of Artificial Moss-Dominated Biological Soil Crusts and Their Effects on Runoff and Soil Water Content in a Semi-Arid Environment. J. Arid. Environ. 2015, 117, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guida, G.; Nicosia, A.; Settanni, L.; Ferro, V. A Review on Effects of Biological Soil Crusts on Hydrological Processes. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2023, 243, 104516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khitun, O.V. Natural Recovery of Man-Made Disturbances in the West Siberian Arctic and Recommended Species for Rehabilitation. Eco Tech. 2003, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secretareva, N.A. Vascular Plants of Russian Arctic and Adjacent Territories; KMK: Moscow, Russia, 2004; ISBN 5-87317-167-X. [Google Scholar]

- Pismarkina, E.V.; Khitun, O.V.; Egorov, A.A.; Byalt, V.V. An Overview of the Alien Flora of the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Area (Russia); Ural Federal University: Yekaterinburg, Russia, 2020; pp. 51–65. [Google Scholar]

- Simberloff, D.; Martin, J.-L.; Genovesi, P.; Maris, V.; Wardle, D.A.; Aronson, J.; Courchamp, F.; Galil, B.; García-Berthou, E.; Pascal, M.; et al. Impacts of Biological Invasions: What’s What and the Way Forward. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2013, 28, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, M.L.; Lapina, I.V.; Shephard, M.; Conn, J.S.; Densmore, R.; Spencer, P.; Heys, J.; Riley, J.; Nielsen, J. Invasiveness Ranking System for Non-Native Plants Alaska; R10-TP-143; United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service Alaska Region: Washington, DC, USA, 2008.

- Fink, K.A.; Wilson, S.D. Bromus Inermis Invasion of a Native Grassland: Diversity and Resource Reduction. Botany 2011, 89, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vil`chek, G.E.; Kuzneczov, D.V. Flora of anthropogenic habitats in the city vicinity of Novy Urengoy (Western Siberia). In Flora of Anthropogenic Habitats in the North; IGRAS: Moscow, Russia, 1996; pp. 100–121. [Google Scholar]

- Pismarkina, E.V.; Byalt, V.V. Materials for the Study of Biodiversity in the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous District: Vascular Plants of the Nuny-Yaha River Basin. Vestn. Orenbg. State Pedagog. Univ. 2016, 1, 49–69. [Google Scholar]

- Business and Biodiversity Offsets Programme (BBOP). Biodiversity Offset Implementation Handbook; BBOP: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, G.M.; Quétier, F.; Wende, W. Guidance on Achieving No Net Loss or Net Gain of Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. In Report to the European Commission, DG Environment on Contract ENV.B.2/SER/2016/0018; Institute for European Environmental Policy: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Schuuring, S.; Halvorsen, R.; Eidesen, P.B.; Niittynen, P.; Kemppinen, J.; Lang, S.I. High Arctic Vegetation Communities With a Thick Moss Layer Slow Active Layer Thaw. JGR Biogeosci. 2024, 129, e2023JG007880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, B.; Yumagulova, L.; McBean, G.; Norris, K.A.C. Indigenous-Led Nature-Based Solutions for the Climate Crisis: Insights from Canada. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, L.; Taillardat, P.; Macreadie, P.I.; Malerba, M.E. Freshwater Wetland Restoration and Conservation Are Long-Term Natural Climate Solutions. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 922, 171218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strack, M.; Davidson, S.J.; Hirano, T.; Dunn, C. The Potential of Peatlands as Nature-Based Climate Solutions. Curr. Clim. Chang. Rep. 2022, 8, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, L.I.; Richardson, K.; Bona, K.A.; Davidson, S.J.; Finkelstein, S.A.; Garneau, M.; McLaughlin, J.; Nwaishi, F.; Olefeldt, D.; Packalen, M.; et al. The Essential Carbon Service Provided by Northern Peatlands. Front. Ecol. Env. 2022, 20, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kåresdotter, E.; Destouni, G.; Ghajarnia, N.; Hugelius, G.; Kalantari, Z. Mapping the Vulnerability of Arctic Wetlands to Global Warming. Earth’s Future 2021, 9, e2020EF001858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, D.A.; Raynolds, M.K.; Daniëls, F.J.; Einarsson, E.; Elvebakk, A.; Gould, W.A.; Katenin, A.E.; Kholod, S.S.; Markon, C.J.; Melnikov, E.S.; et al. The Circumpolar Arctic vegetation map. J. Veg. Sci. 2005, 16, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartsch, A.; Efimova, A.; Widhalm, B.; Muri, X.; Von Baeckmann, C.; Bergstedt, H.; Ermokhina, K.; Hugelius, G.; Heim, B.; Leibman, M. Circumarctic Land Cover Diversity Considering Wetness Gradients. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2024, 28, 2421–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugelius, G.; Loisel, J.; Chadburn, S.; Jackson, R.B.; Jones, M.; MacDonald, G.; Marushchak, M.; Olefeldt, D.; Packalen, M.; Siewert, M.B.; et al. Large Stocks of Peatland Carbon and Nitrogen Are Vulnerable to Permafrost Thaw. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 20438–20446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreplin, H.N.; Santos Ferreira, C.S.; Destouni, G.; Keesstra, S.D.; Salvati, L.; Kalantari, Z. Arctic Wetland System Dynamics under Climate Warming. WIREs Water 2021, 8, e1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CAFF. Scoping for Resilience and Management of Arctic Wetlands: Resilience & Management of Arctic Wetlands: Phase 2 Report. Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna International Secretariat; CAFF: Akureyri, Iceland, 2021; ISBN 978-9935-431-99-8. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, C.; Cottenie, K.; Gingras-Hill, T.; Kokelj, S.V.; Baltzer, J.L.; Chasmer, L.; Turetsky, M.R. Mapping and Understanding the Vulnerability of Northern Peatlands to Permafrost Thaw at Scales Relevant to Community Adaptation Planning. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 055022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olefeldt, D.; Goswami, S.; Grosse, G.; Hayes, D.; Hugelius, G.; Kuhry, P.; McGuire, A.D.; Romanovsky, V.E.; Sannel, A.B.K.; Schuur, E.A.G.; et al. Circumpolar Distribution and Carbon Storage of Thermokarst Landscapes. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serikova, S.; Pokrovsky, O.S.; Laudon, H.; Krickov, I.V.; Lim, A.G.; Manasypov, R.M.; Karlsson, J. High Carbon Emissions from Thermokarst Lakes of Western Siberia. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- In ’T Zandt, M.H.; Liebner, S.; Welte, C.U. Roles of Thermokarst Lakes in a Warming World. Trends Microbiol. 2020, 28, 769–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmgren, M.; Groten, F.; Carracedo, M.R.; Vink, S.; Limpens, J. Rewilding Risks for Peatland Permafrost. Ecosystems 2023, 26, 1806–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarovnyaev, B.N.; Popov, V.F.; Shubin, G.V.; Budikina, M.E.; Sokolova, M.D. Prospects of Peat Development in the Arctic and Subarctic Zones of Russia. Gorn. Inf. Anal. Bull. 2020, 6, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zotova, L.I.; Tumel, N.V. Selection Methodology of Nature Protection Measures in the Field of Permafrost in the Study of the West Siberian Oil and Gas Province. Reg. Environ. Issues 2018, 1, 93–98. [Google Scholar]

- Egorov, A.A.; Koptseva, E.M.; Sumina, O.I.; Fatianova, E.V.; Kirillov, P.S.; Ivanov, S.A.; Trofimuk, L.P. Long-Term Biodiversity Monitoring of the Spontaneous Successions for the Assessment of the Artificial Restoration Progress on the Quarries in Russian Arctic. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 263, 012002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novick, K.A.; Keenan, T.F.; Anderegg, W.R.L.; Normile, C.P.; Runkle, B.R.K.; Oldfield, E.E.; Shrestha, G.; Baldocchi, D.D.; Evans, M.E.K.; Randerson, J.T.; et al. We Need a Solid Scientific Basis for Nature-Based Climate Solutions in the United States. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2318505121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orchard, S.; Fitzpatrick, B.M.; Shah, M.A.R.; Andrade, A. Impact Assessment Frameworks for Nature-Based Climate Solutions: A Review of Contemporary Approaches. Sustainability 2025, 17, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virkkala, A.-M.; Abdi, A.M.; Luoto, M.; Metcalfe, D.B. Identifying Multidisciplinary Research Gaps across Arctic Terrestrial Gradients. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 124061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallandt, M.M.T.A.; Kumar, J.; Mauritz, M.; Schuur, E.A.G.; Virkkala, A.-M.; Celis, G.; Hoffman, F.M.; Göckede, M. Representativeness Assessment of the Pan-Arctic Eddy Covariance Site Network and Optimized Future Enhancements. Biogeosciences 2022, 19, 559–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heijmans, M.M.P.D.; Magnusson, R.I.; Lara, M.J.; Frost, G.V.; Myers-Smith, I.H.; van Huissteden, J.; Jorgenson, M.T.; Fedorov, A.N.; Epstein, H.E.; Lawrence, D.M.; et al. Tundra Vegetation Change and Impacts on Permafrost. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dudov, S.V.; Pryadilina, A.V.; Kumaniaev, A.S.; Bocharnikov, M.V.; Naumov, A.D.; Chernianskii, S.S.; Slobodyan, V.Y. Are Nature-Based Climate Solutions in the Russian Arctic Feasible? A Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10409. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210409

Dudov SV, Pryadilina AV, Kumaniaev AS, Bocharnikov MV, Naumov AD, Chernianskii SS, Slobodyan VY. Are Nature-Based Climate Solutions in the Russian Arctic Feasible? A Review. Sustainability. 2025; 17(22):10409. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210409

Chicago/Turabian StyleDudov, Sergey V., Aleksandra V. Pryadilina, Anton S. Kumaniaev, Maxim V. Bocharnikov, Andrey D. Naumov, Sergey S. Chernianskii, and Vladimir Y. Slobodyan. 2025. "Are Nature-Based Climate Solutions in the Russian Arctic Feasible? A Review" Sustainability 17, no. 22: 10409. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210409

APA StyleDudov, S. V., Pryadilina, A. V., Kumaniaev, A. S., Bocharnikov, M. V., Naumov, A. D., Chernianskii, S. S., & Slobodyan, V. Y. (2025). Are Nature-Based Climate Solutions in the Russian Arctic Feasible? A Review. Sustainability, 17(22), 10409. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210409