1. Introduction

Two severe recessions have hit Western countries in the first two decades of this century: the first one (2009) was fuelled by the financial crisis, and the second one (2020) was driven by the COVID epidemic. Moreover, the last decades have also witnessed a striking increase in income inequality related also to a greater concentration in labour income distribution and a reduction in the share of national income appropriated by the labour factor (see, e.g., the extensive documentation provided by the OECD [

1], as well as the influential contributions of Stiglitz [

2,

3], and Piketty [

4], which have oriented the international debate on inequality and issues of distributive justice). Recessions entail layoffs, which make labour income distribution even more uneven. The dramatic fall in GDP featuring many countries and the contemporary rise in income inequality have addressed deep concerns about the resilience of different economic systems and different business organisations, especially regarding the dynamics of employment (see, e.g., the early international experiences surveyed in [

5], the contribution by [

6] on governance characteristics, the essays mostly dealing with Swiss case studies collected in [

7], and the analysis proposed by [

8] and the literature cited therein). As for the French experience, Musson and Rousselière [

8] investigate the economic performance of a group of craftsmen cooperatives during the 2009 crisis. They share with a large empirical literature the conclusion that cooperatives exhibit a stronger resilience in terms of output than other suppliers.

As compared to international tendencies, Italy is no exception; hence, it is not surprising that, looking for structural explanations of the Italian economic performance, many scholars have investigated the impact of Italian cooperative firms on the resilience of local economic systems especially regarding the pattern of employment (see, e.g., Burdin and Dean [

9] and Costa and Delbono [

10]). It turns out that Italian cooperative enterprises, in the post-Lehman Brothers recession, displayed greater resilience than capitalist ones, especially in limiting the impact of the downturn on employment; see, e.g., [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

The empirical literature we have referred to investigates the impact of the 2009 downturn or of prolonged recessionary periods on cooperative firms as opposed to conventional enterprises and documents that the former ones appear more resilient than the latter ones. Additional research should try to test whether such differential performance across types of firms also applies to the COVID recession.

In the economic literature, we witness a variety of notions of “resilience”, focusing time by time on different aspects considered crucial by the researchers and affecting the measurement of the resilience itself (see the updated taxonomy of Serfilippi and Ramnatha [

19] and the review in [

20]). In this paper, we align with the vast literature following the approach pioneered by Fingleton et al. [

21] and surveyed in [

22] according to which the notion of resilience might be split at least into two sides:

resistance, when the shock occurs, and recovery from the shock. Hence, the new contributions on the performance of cooperatives should try to also examine the

recovery phase following the COVID shock. Since the epidemic was observed in 2020 and 2021, we need at least two subsequent years to control for the recovery period. This is precisely what we are going to propose, by contributing to the existing research with a comparative analysis for the period 2014–2023.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first empirical study of a national economy considering (i) the set of all active firms over a decade, (ii) the business model (cooperative vs. capitalist), and (iii) a time span including both the resistance and recovery period related to the COVID recession.

In this framework, our study addresses three main research questions.

First, we ask whether cooperative firms significantly differ from capitalist ones in the way they allocate value added, that is, whether their labour cost to added value ratio is systematically higher.

Second, we explore whether this labour preference leads to greater employment resilience, particularly during economic downturns.

Third, we investigate whether the cooperative advantage observed in the 2008 crisis persists in the more recent decade, or whether it has weakened.

From these questions, we formulate the following hypotheses:

H1. Cooperatives show greater employment resilience than capitalist firms during recessions.

H2. The cooperative advantage in terms of employment resilience diminishes in the post-COVID years, likely reflecting changing social and institutional conditions in the Italian economy.

H3. Cooperatives exhibit a higher and more stable labour cost to added value ratio than capitalist firms, reflecting their structural commitment to labour remuneration.

This paper is organised as follows. In

Section 2, we briefly introduce the cooperative business model and account for its size worldwide. In

Section 3, we present our dataset and the variables we are mostly interested in.

Section 4 illustrates the econometric strategy that we follow to obtain the results discussed in

Section 5.

Section 6 concludes.

2. The Cooperative Business Model

The main motivation inducing us to explore the role of cooperative firms lies in their pursuit of socially desirable goals, strongly oriented toward an inclusive and sustainable economic system. In 2015, the United Nations General Assembly approved the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs henceforth) to be met by 2030. Twenty years earlier, the International Cooperative Alliance (ICA, from now) adopted the revised statement on the cooperative identity (including the definition of cooperative) and the seven so-called cooperative principles. A cooperative is defined as “an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly owned democratically controlled enterprise.” Its principles modernize the contents of a manifesto shared by the Rochdale “pioneers”, a group of artisans of this Northern England city who in 1844 established what is since then often considered the first proper instance of cooperative business organisation. Those 28 pioneers also set a group of principles which were adopted in 1937 by the ICA, which updated them in 1966. The latest version became part of ICA’s statement in 1995 and concerns cooperative governance (e.g., membership, democratic control, autonomy, limited return).

If principles entail goals and actions, it is worth stressing the substantial overlap between the derived cooperative goals and the SDGs, as well as the role of cooperative organisations in facilitating SDG implementation [

23,

24,

25].

In the wake of [

24] (p. 5), “the cooperative model is very well placed to address the challenges posed by transitions to sustainability, including those such as poverty, gender inequality or economic and social exclusion. Three main lines of thought can support this argument. Firstly, the original cooperative values and principles stand in a close and harmonious relation to the aims and objectives set out in the 17 SDGs and 169 indicators. Second, in a similar way, cooperatives can act along what has been termed a ‘triple-bottom line’; as social organisations, environmental actors, and economic actors, cooperatives often meet these goals simultaneously. Third, and in addition to the triple bottom line, cooperatives also address challenges of governance by fostering member economic participation and facilitating education and training, ways in which they can solve common problems and enable people to take charge of their own development. The report then goes on to outline how the cooperative values and principles are deeply interlinked with the SDGs in a coherent conceptual framework.

More specifically, cooperative principles are closely aligned with SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities), SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), and SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions). By means of these channels, cooperatives can significantly contribute to economic, social, and institutional sustainability through participatory, inclusive, and long-term-oriented practices. In this work, our emphasis is on stable, inclusive and resilient employment, which is shared both by the SDGs and by the cooperative principles. Lafont et al. [

23] provide an illuminating bibliometric analysis of the large literature, which addresses research questions such as “What is the role of cooperatives in promoting compliance with SDGs?” or “What are the main SDGs linked to cooperatives?”

The economic modelling of cooperative firms is not an easy task. Since the pioneering paper by Ward [

26], only a few steps have been made to embed some findings from the growing empirical literature into consistent formal frameworks; see [

27] and the vast literature cited therein [

28,

29]. According to Ward, in a perfectly competitive industry populated only by workers’ cooperatives (labour-managed firms, in his own words), each cooperative chooses the number of workers (all members) to maximize the revenue, net of non-labour costs, per worker-member. In the recent theoretical contributions, instead, more realistic assumptions are considered: cooperatives compete with conventional firms in mixed oligopolies and may also choose the size of their membership. Although modelled very differently, the concern for workers and employment level unites the old and the new approaches. This is no surprise, because the very origins of the cooperative movement lie in the attempt to overthrow the ordinary superiority of stockholders over workers. Absent financial constraints, the choice of participating as a working member in a (new) cooperative, as opposed to enter as a simple worker in capitalist company, reveals a preference for (i) more stable—though usually less paid—employment, and the chance of (ii) sharing democratically (one head, one vote) the control of the company and (iii) contributing to a more sustainable and equitable society.

The economic impact of cooperative presence, in terms of added value as well as employment, may be large. Indeed, while unevenly distributed across countries, the size of the cooperative movement worldwide is huge. According to the ICA’s [

14,

24] reports, the cooperative movement is the largest entrepreneurial organisation on the planet, with almost 3 million companies and over 1 billion members. It provides jobs and work opportunities for 280 million people, amounting to roughly 10% of the world’s employed population.

Italy ranks top in terms of the economic importance of cooperative enterprises. In 2021, the Italian cooperative companies accounted for about 1,627,000 employees (7.2% of total employment in the Italian private sector) and over 29 billion euros added value (4.2% of the total); see Euricse [

30]. Moreover, there is some evidence that the cooperative presence at the territorial level is positively associated with economic prosperity. This is shown in [

10], considering the Italian regions in the period 2010–2019 and building on a welfare measure originally proposed in Sen [

31], which combines (positively) the average individual incomes and (negatively) the dispersion around the average (captured by the Gini index of the regional income distribution). The resulting index of widespread prosperity turns out to be positively associated with the size of the regional cooperative employment. There are then valid arguments to consider the Italian economic system as a significant benchmark to test the contribution of cooperative firms to the socio-economic sustainability and to the protection of employment, especially during macroeconomic downturns.

3. Data and Variables

Our dataset comes from the Aida–van Dijk database and includes a panel of all Italian firms that operated continuously from 2014 to 2023 and regularly submitted balance sheets. Its key strength is the inclusion of microdata.

Although the set of firms active throughout the entire decade may not be fully representative of the overall economic situation, our choice of panel data is motivated by the fact that it allows for much greater comparability of business models and provides stronger control over unobserved heterogeneity. However, focusing only on firms continuously active from 2014 to 2023 means that our findings are based only on surviving firms, which may be more resilient than the average firm. This selection may therefore introduce a survivorship bias.

The dataset allows one to classify firms by means of their legal form; hence, we distinguish between the group of “cooperatives”, while we aggregate all the other legal forms under the label “capitalist”.

As for the classification into the two groups, it is important to remember the longstanding issue of “spurious” cooperatives. These are firms legally registered as cooperatives, but operating like conventional firms. Since they do not adhere to any coop association, they often escape monitoring or controls.

We focus on four main variables to analyse firms’ economic and financial performance, with particular attention to their impact on employment and the labour market: value of production, added value, employment, and labour costs. Our crucial variable is the labour cost to added value ratio (LC/AV), which we adopt as a key indicator of the economic impact of cooperatives. This metric, which is a variant of the well-known payroll ratio (LC/revenue), allows us to assess the influence of cooperatives on employment and economic performance, particularly in the context of the sustainability of the economic system.

The availability of microdata allows for a detailed comparison between cooperatives and non-cooperatives; in fact, we can analyse the full distribution of the LC/AV ratio rather than simply relying on synthetic indicators such as the mean.

The LC/AV ratio is usually constrained between 0 and 1 under normal economic conditions; it must be greater than 0 to ensure a minimum level of labour remuneration, and less than 1 to allow for capital remuneration. However, in specific cases or during periods of economic distress, added value may fall below labour costs, causing the LC/AV ratio to exceed 1. In extreme scenarios, where firms incur significant losses, added value may become negative, resulting in an LC/AV ratio below 0. To avoid distortions, we restrict the range of the LC/AV variable to exclude extreme values that are economically implausible or likely driven by temporary shocks, accounting for only a very small percentage of observations. This ensures that the analysis both focuses on representative LC/AV ratios and maintains the ability to study the full distribution of the variable. We therefore define lower and upper bounds, y

L and y

H, and only include values within the range y

L ≤ y ≤ y

H. In the following, we set y

L = −2 and y

H = 2; however, other thresholds that exclude extreme LC/AV values lead to similar results. The sequence of steps to obtain the final dataset, addressing the main issues typically encountered in this type of data [

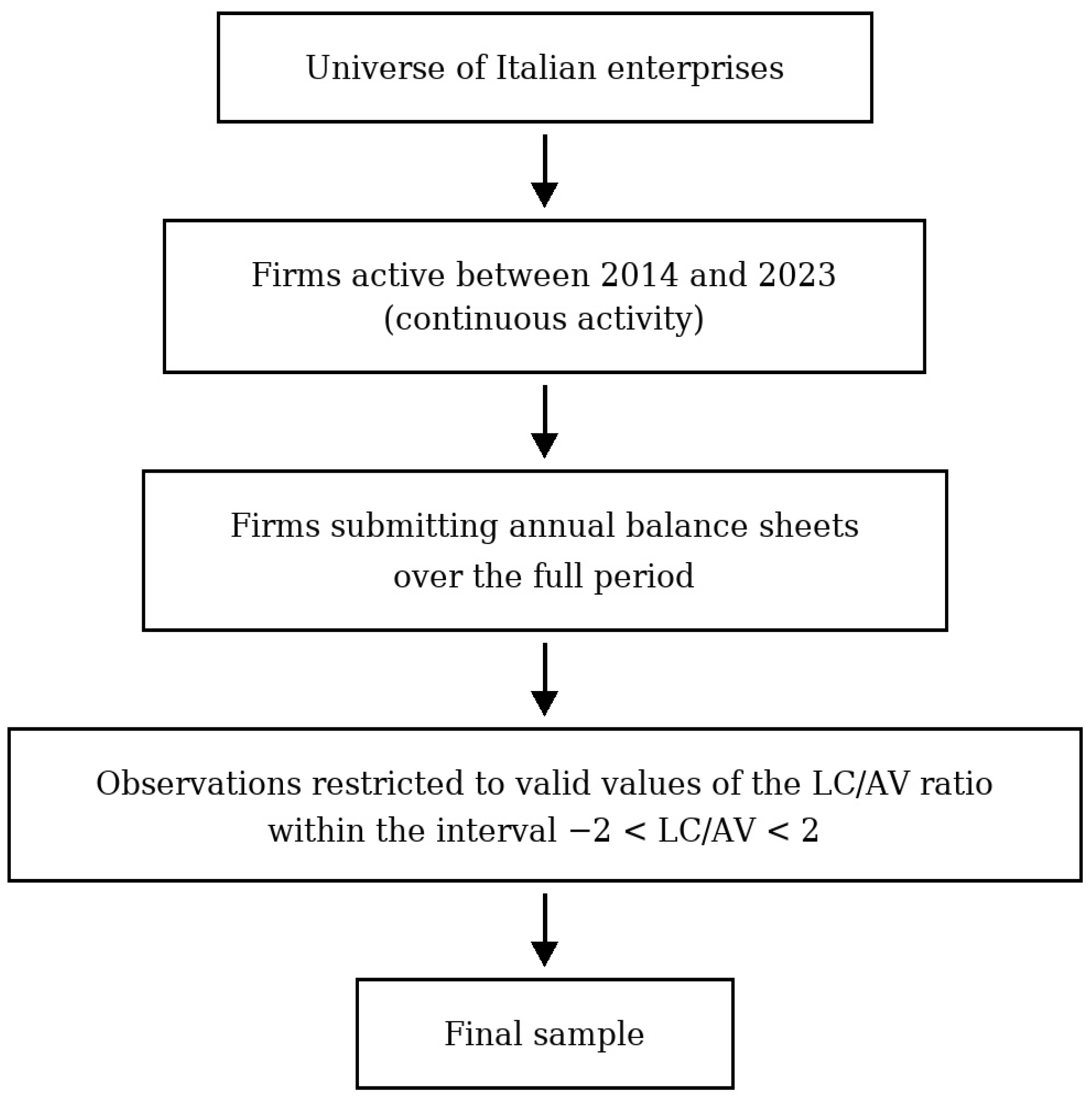

32], is summarized in the following flowchart (

Figure 1).

In

Table 1, we report some descriptive statistics which show consistent structural differences between cooperatives and capitalist firms over the decade 2014–2023.

On average (first two columns of

Table 1), cooperatives employ significantly more workers per firm than capitalist firms (e.g., 62.1 vs. 35.8 in 2023), reflecting their typically larger size in terms of employment. It is certainly true that firm size depends on the sector of activity and that cooperatives are more prevalent in labour-intensive sectors; however, the larger size of cooperatives represents a stylized fact that holds even within sectors. The gap in average firm size between the two business models slightly increases over the decade, from +23 to +26 in favour of cooperatives, while it slightly decreases in relative terms, with cooperatives in 2023 being 73% larger than capitalist firms, compared to 82% in 2014.

The number of firms in the panel (approximately 150,000 capitalist firms and around 9000 cooperatives), which should be constant over the period, shows (last two columns of

Table 1) minimal change due to the restriction y

L = −2 and y

H = +2, which led to the exclusion of several observations.

Our key variable, the labour cost to added value (LC/AV) ratio (third and fourth columns of

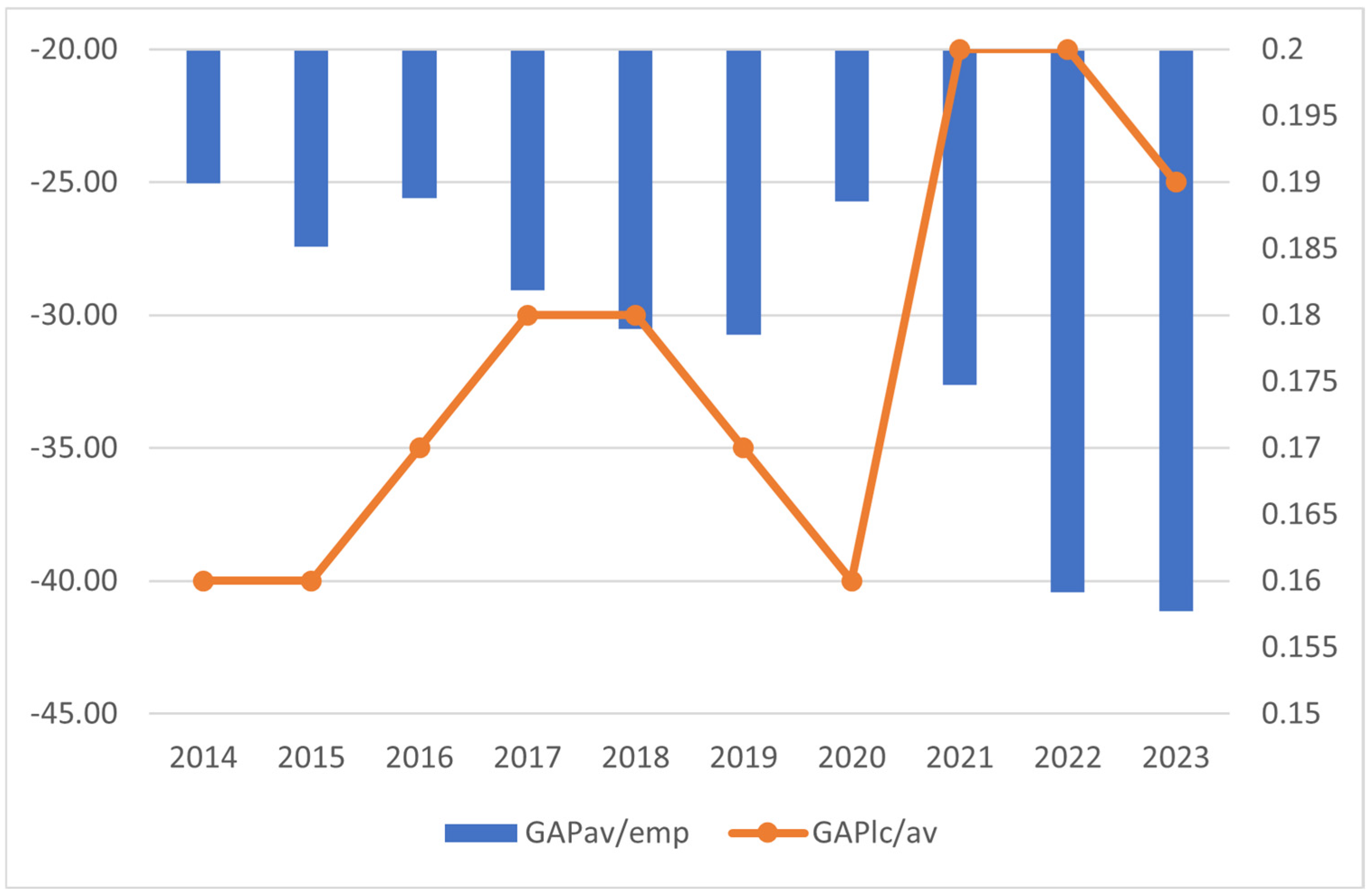

Table 1), is systematically higher for cooperatives, indicating a stronger commitment to labour remuneration. This ratio remains stable for cooperatives (around 0.84–0.85), while it declines slightly for capitalist firms (from 0.67 in 2014 to 0.63 in 2023), leading over the decade to a widening of the gap between the two types of firms by about 3 percentage points, from +16 in 2014 to +19 in 2023, as illustrated in

Figure 2.

In contrast, added value per employee (AV/EMP) is consistently higher for capitalist firms, with the gap widening over time—by 2023, it reached EUR 85.8k for capitalist firms compared to EUR 44.7k for cooperatives (fifth and sixth columns of

Table 1 and

Figure 2). While it is well-known that cooperatives tend to operate in labour-intensive sectors, the above difference may suggest lower labour productivity in cooperatives.

Notice that high values of the ratio LC/AV within cooperatives may foreshadow endogeneity issues when performing econometric analysis about the relationship between “being cooperative” and a high share of added value distributed to labour. As we argue in

Section 2 above, the decision of opening a cooperative business incorporates indeed a preference for employment protection (high LC/AV). However, from

Table 1, we observe that cooperatives exhibit a lower level of AV/EM and a low average individual pay, which should discourage participation in a cooperative business, especially in a workers’ one. It is worth noting that, including social cooperatives, workers cooperatives represent about two-thirds of all Italian cooperative firms active in 2021 [

30].

Turning to employment dynamics,

Table 2 highlights notable differences in employment trends between cooperatives and capitalist firms over the 2014–2023 period. Let

eCAPt,

eCOOPt, and

eNt denote employment in capitalist firms, cooperatives, and at the national level, respectively, and their respective variations be defined as

These are the key ingredients for measuring employment resilience according to the approach proposed by [

21].

While both categories of firms show overall employment growth, cooperatives exhibit higher year-on-year variation in the early years, particularly between 2015 and 2018. However, starting from 2019, the pattern shifts. Cooperatives experience a flattening or even slight decline in employment, whereas capitalist firms maintain an increasing pattern. It is worth noting the data related to 2020, the only year in which employment in capitalist enterprises declined, while, on the contrary, cooperatives showed a better result than capitalist ones. The post-COVID period 2021–2023 appears more problematic for cooperatives, which display weak employment dynamics and much weaker ones than capitalist enterprises.

In the last two columns of

Table 2, we report the ratio between employment variation in the panel and the variation in national employment. The resulting number represents our chosen measure of employment resilience, which we adopt following a large body of literature (see, e.g., [

33,

34]), also because of its simplicity:

Between 2015 and 2018, cooperatives consistently outperformed non-cooperative firms. From 2019 onward, however, cooperatives’ contribution drops quite a lot, falling below that of capitalist firms. Cooperatives played a significant role in the earlier part of the decade, but their resilience during more recent years (e.g., post−2019) appears weaker relative to non-cooperative firms. While in the period 2014–2020, employment resilience was higher for cooperatives, once the last three years are included, the result turns out to be more favourable to capitalist enterprises, highlighting how the 2021–2023 period has been one of difficulty for cooperatives.

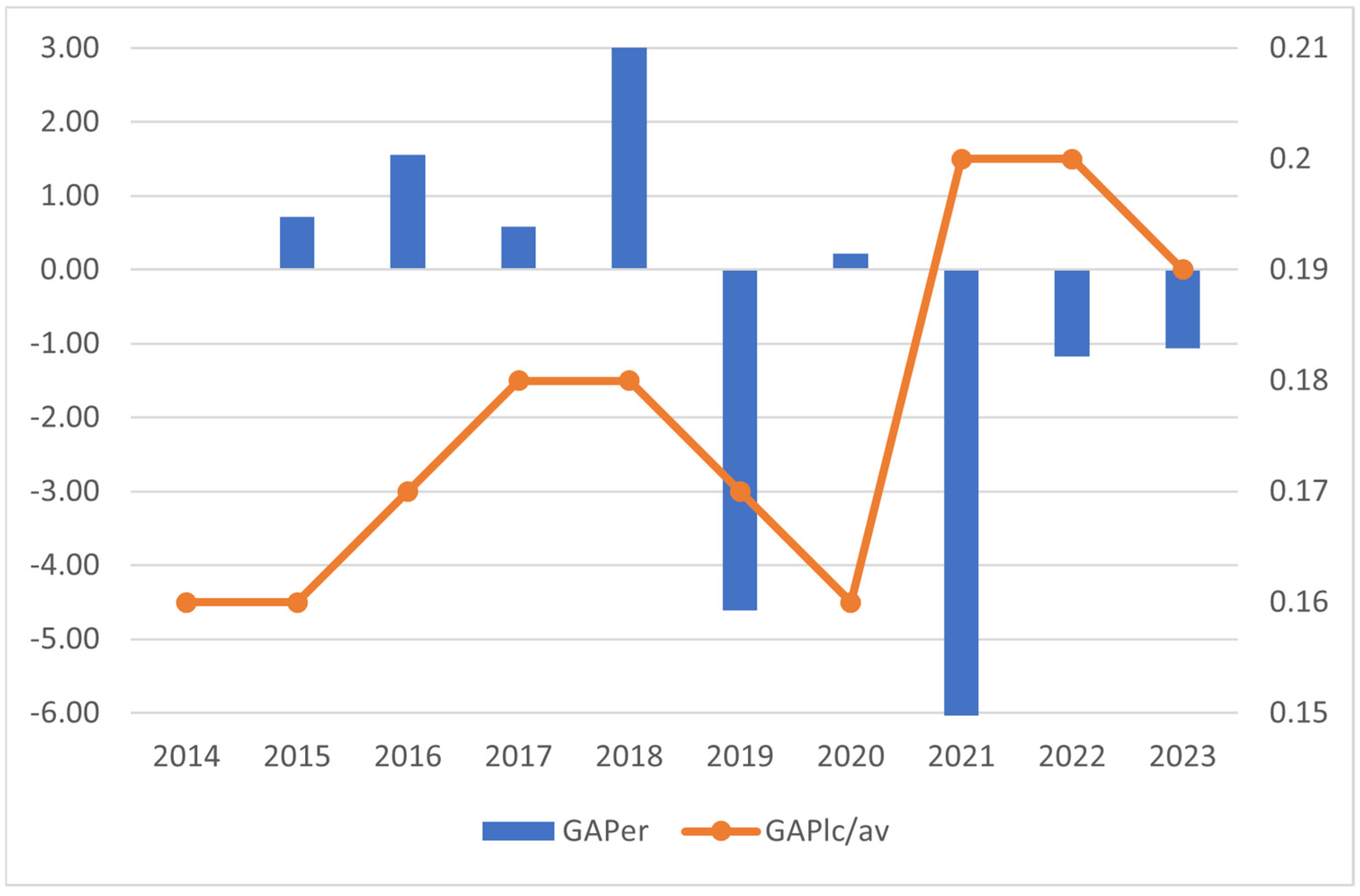

A possible summary of the data and results discussed in this section is presented in

Figure 3, which shows the difference between the LC/AV ratio of cooperatives and that of capitalist firms, GAPlc/av = LC/AV

COOP − LC/AV

cap, as well as the difference in employment resilience indicators, GAPer = ER

COOP − ER

cap.

It can be observed that, although the employment resilience of cooperatives worsens (left axis) toward the end of the decade under consideration, this does not translate into a deterioration of the LC/AV ratio. On the contrary, the ratio improves (right axis), confirming the cooperatives’ sustained attention to labour remuneration.

4. Methodologies

To analyse the LC/AV ratio and to evaluate the role of cooperatives within our panel dataset, we adopt a twofold econometric strategy. First, we estimate a pooled OLS model using the full dataset; second, we implement a panel specification. In this way, we fully exploit the double dimension (temporal and cross-sectional) of our data.

The analysis is first conducted in terms of the levels of the LC/AV ratio. To consider possible dynamic characteristics, we also extend the analysis to the first differences, that is, to the changes between period

t and

t – 1:

with LC

t/AV

t =

yt, thus allowing us to analyse the dynamic adjustments of the ratio over time.

As noted in the previous section, it is reasonable to expect biases caused by extreme or non-representative values of LC/AV, driven also by the specific period under scrutiny, during which the added value of some firms turned out to be extremely low or even negative. As a reaction, we restricted the LC/AV ratio within the range defined by −2 ≤ yt ≤ 2 and ruled out all observations falling outside this interval.

We also control for heterogeneity stemming from sectors in which firms operate, geographic factors and firms ’size. To the end of focusing our analysis on the role of cooperative enterprises—without ignoring potential unobserved heterogeneity and the presence of confounding factors—we adopt a method inspired by pairwise aggregate estimation, which exploits differences between pairs of observations to identify systematic underlying patterns.

More specifically, we first group observations into H (h = 1, …, H) clusters of similar units, that is, firms operating in the same geographic region, within the same economic activity sector, belonging to the same size class, and, most importantly, sharing the same business model (cooperative or capitalist). This clustering procedure allows us to compare firms that are homogeneous along key observable dimensions (in our case, geographic location, sector of activity, firm size, and business model) and exposed to similar market and institutional conditions. Second, we compute within-cluster means as , where is the number of observations in the h-th group in year t. Finally, under the assumption of intra-group homogeneity, individual observations are set equal to the mean of their respective group, thus minimizing the consequences of unobserved heterogeneity and confounding factors, with the aim of focusing on and highlighting the effect of the cooperative business model.

This procedure leads to a reformulation of the usual minimization problem

which then becomes

We also focus on the interaction between firm type and macroeconomic conditions, which provides a useful way to include the time-invariant cooperative dummy variable in a fixed-effects panel model, where it could not be captured directly. To measure macroeconomic conditions, we compute the average change between time

t and time

t − 1 in the total production (

TP) of individual firms

As for the interpretation of the value of , when positive, it indicates an expansionary phase, reflecting overall growth in production, while when the sign is negative, it signals a recession, e.g., a contraction in aggregate firm output.

Finally, unlike the standard approach that assumes a single, symmetric effect and therefore cannot capture potential differences in responses to improvements or deteriorations in the ratio, we propose a specification that allows for asymmetric effects. This generalization enables us to explicitly account for differential reactions to positive or negative changes, providing a more complete and realistic model of firms’ behaviour and also allowing for a more precise assessment of the differences between cooperative and capitalist firms.

5. Results

The first result of our analysis concerns the measurement of the employment resilience of cooperative enterprises compared with other firms. As illustrated in

Section 3, we showed that (i) the average firm size in terms of employment in cooperatives continues to exceed that of other enterprises; (ii) cooperatives display greater resilience up to 2018, but their performance becomes weaker than that of capitalist firms starting from 2019, especially during the

recovery phase 2021–2023 (

Table 2); (iii) interestingly, cooperatives are more resilient in 2020, when epidemic fuels the huge recession, meaning that cooperatives perform better during the

resistance phase; (iv) the gap between the two types of firms widens both in the share of value added distributed to employees (higher in cooperatives) and in value added per employee (higher in capitalist firms).

These findings are neatly related to our initial hypotheses H1–H3. Specifically, result (ii) supports H2, the third confirms H1, and the fourth is consistent with H3. It is worth stressing that our results have to be interpreted within the broader Italian macroeconomic context, which can be summarized, for our purposes, by the very low GDP growth during the decade following the 2009 recession and the generally low—when positive—profits of cooperative enterprises, often characterized by substantial under-capitalization. It is therefore not surprising that, in the final years of our observation period, cooperative firms display a weaker employment dynamic than other enterprises.

To further investigate these patterns and assess the robustness of the descriptive results, we develop an econometric analysis based on four models: two pooled OLS specifications (one for the LC/AV ratio in levels and one for its first differences) and two fixed-effects panel models (again, for levels and first differences). The inclusion of first-difference specifications allows us not only to capture the possible dynamic dimension of firms’ behaviour, but also to control for time-invariant unobserved heterogeneity, thus providing a more robust assessment of the relationship between labour costs and value added.

In the framework of our methodology, inspired by the pairwise aggregate estimation approach, we group the data by region, macro-sector, firm size, year, and business model. To capture geographical differences, we refer to the 20 Italian regions; to account for sectoral heterogeneity, we consider the 21 macro-sectors defined at the European level by the NACE Rev. 2 classification; and to control for firm size, we adopt the four standard categories (micro: fewer than 10 employees; small: up to 50; medium: up to 250; large: above 250). Overall, our clustering procedure results in a total of H = 23,721 groups.

The main results regarding the impact of cooperatives are summarized in

Table 3. In all models, cooperatives exhibit significantly higher LC/AV ratios as compared to non-cooperative firms, confirming a structural feature of cooperative firms.

In the pooled OLS model on levels, the coefficient on the cooperative dummy is positive and highly significant (+0.1975), confirming that cooperatives allocate a larger share of value added to labour. Interestingly, the negative and significant interaction between coop and macroeconomic cycle (−0.0048) suggests a countercyclical behaviour of cooperatives: as the economy improves, the LC/AV ratio of cooperatives increases to a lesser extent than that of other firms.

Looking at the dynamic pattern, in the OLS model on

first differences, the cooperative dummy remains positive and significant (+0.0227), indicating that cooperatives, on average, show larger increases in LC/AV over time. However, when considering interactions with economic conditions, the findings reveal a notable asymmetry. Unlike the previous model, which was specified in levels, the first differences in the LC/AV ratio are significantly more sensitive (+0.0055) to macroeconomic conditions: when the cycle improves, the growth of LC/AV in cooperatives is higher than in non-cooperatives. This discrepancy with respect to the previous model is only apparent; the levels model captures the relative pro-cyclicality of cooperatives in terms of average LC/AV shares, while the first-difference model reflects their response to short-term fluctuations. Thus, although cooperatives exhibit less cyclical variation in levels, their period-to-period changes appear more sensitive, showing stronger increases during upturns and sharper decreases during downturns. Finally, when LC/AV declines, cooperatives experience an even larger reduction (−0.0021) compared to non-cooperatives. This finding can be interpreted consistently with the strategies of cooperatives: on the one hand, they tend to protect employment even during recessions (as shown in

Table 2); on the other hand, they typically operate with lower value added per worker and allocate a higher share of value added to labour (see

Table 1). As a consequence, when LC/AV declines, cooperatives experience a steeper drop because their margins for adjustment are more limited than those of other firms [

35].

Moving to the panel data analysis, the Hausman test suggests that the fixed effects model is to be preferred over a random effects model. In the fixed effects model, however, the cooperative effect, being time-invariant, must be captured indirectly.

The panel fixed-effects models confirm the patterns observed in the pooled OLS estimation. In the model on first differences, the coop interaction with reductions in LC/AV remains significant and strongly negative (−0.0468), reinforcing the idea that cooperatives face disproportionately stronger contractions in LC/AV. At the same time, both in levels as well as in first differences, some year-specific interactions (e.g., coop and year 2021) are strongly positive, confirming an increasing advantage of cooperatives over capitalist firms in terms of LC/AV and also hinting at a rebound effect after particularly adverse periods like the COVID–19 crisis (see also Fernandez-Cerezo et al. [

36]). This effect, which may appear inconsistent with the weak employment dynamics and the lower employment resilience observed for cooperatives in

Table 2 for 2021, does not primarily concern employment—which indeed remains fragile—but rather the differential in the LC/AV indicator, which shows a marked decline for capitalist firms between 2020 and 2021 (see

Table 1).

The panel model on levels also indicates that, during periods when LC/AV decreases, the decline is more pronounced (−0.023) in cooperatives than in non-cooperative firms. At first glance, the significant but negative interaction between cooperatives and LC/AV declines could seem counterintuitive, particularly if one assumes that a more significant drop in LC/AV reflects a weakening commitment to labour. However, a closer analysis of the data, summarized in

Table 4, leads to a different explanation.

While both cooperatives and non-cooperatives experience simultaneous increases in value added and labour costs, the magnitude of these increases differs. In non-cooperative firms, the average increase in value added is approximately EUR 236, compared to an EUR 81.8 rise in labour costs. In contrast, cooperatives see an average increase of EUR 121 in value added and EUR 54.8 in labour costs. These figures suggest that the difference between the growth of added value and labour costs is significantly larger in non-cooperatives (around EUR 154.2) than in cooperatives (around EUR 66.2).

This pattern has important implications for the interpretation of LC/AV dynamics. Since the LC/AV ratio is defined as labour cost divided by value added, it will decline when the value added grows faster than labour costs. Given the sharper increase in value added among non-cooperatives, one would expect a more substantial drop in LC/AV in that group. Yet, the model shows the opposite result, i.e., a larger LC/AV decline in cooperatives. This apparent contradiction can be accounted for by considering the initial level of the LC/AV ratio. Cooperatives typically allocate a greater share of their value added to labour compensation, resulting in a higher initial LC/AV. Therefore, even modest growth in value added, relative to labour costs, can produce a significant relative drop in the LC/AV ratio. In summary, the steeper decline observed in cooperatives reflects their higher initial level, not a decrease in labour commitment. Therefore, the negative coefficient associated with cooperatives in the LC/AV model can be interpreted as evidence of their continued support for labour. Despite a slower value-added growth, cooperatives maintain increases in labour cost, preserving their core missions even under economic stress. This suggests a form of resilient behaviour that prioritizes employment and income stability.

Finally, it is worth noting that the results summarized in

Table 3 and

Table 4 display a satisfactory degree of robustness from several perspectives. First, the comparison between the static model (in levels) and the dynamic specification (in first differences) yields consistent outcomes, which can be interpreted as a robustness check. In addition, alternative clustering procedures—for instance, excluding the geographical factor or using a different regional aggregation (such as 5 macro-areas instead of 20 regions)—lead to results that confirm our main hypotheses and conclusions.

6. Conclusions, Policies and Extensions

To summarize the most innovative aspects of our contribution, we may stress that, by having the complete set of active firms over a decade encompassing both the resistance and recovery related to the COVID−19 pandemic, we are able to draw a deeper understanding of the role played by different business models (cooperative vs. capitalist) within the economic system. We examine the economic and social role of cooperatives by means of the analysis of the employment resilience and the labour cost to added value ratio (LC/AV). We use this ratio as a key metric to assess how firms allocate resources between labour and capital.

Our results show that cooperatives exhibit significantly higher LC/AV ratios than capitalist firms, reflecting a stronger commitment to labour remuneration and to the achievement of SDGs, especially the 8th and the 10th ones. This is consistent with our initial hypothesis H3. However, we have to note that this behaviour of cooperatives incurs the potential cost of weakening themselves financially. We extend the previous literature in the direction of exploring asymmetric effects in the behaviour of LC/AV. Moreover, we explore the presence of dynamic effects in the relationship between the LC/AV ratio and the business model. Interestingly, cooperatives exhibit more pronounced reductions in the LC/AV ratio when this ratio decreases compared to the previous year. However, this should not be interpreted as a retreat from their labour-oriented mission. Rather, it reflects their initially higher LC/AV levels, implying that even modest growth in value added can lead to substantial proportional declines in the ratio. On the contrary, cooperatives continue to sustain labour costs even when value added grows slowly, reaffirming their role in supporting employment even under conditions of economic stress. While employment in cooperatives shows strong growth and a more robust dynamic than capitalist enterprises up to 2018, and despite their greater resilience to the pandemic shock in 2020, their contribution to national employment weakened in the years of recovery 2021–2023. These conclusions are consistent with both H1 and H2. Overall, the cooperative business model emerges as a relevant channel for promoting social sustainability through labour remuneration and income stability.

Our results hint at some policy implications. First, the ability to stabilize employment, especially during downturns, should be recognized as a positive contribution to a more equitable and socially sustainable pattern. We know how heavy the consequences of recessions are for public accounts because of the decline in tax revenues and the surge in social spending. Appropriate fiscal incentives could be designed in favour of those organisations, as cooperatives, that succeed in absorbing the impact of macroeconomic shocks on employment with a comparatively lower resort to social safety nets. Second, the allocation of added value within cooperatives echoes a zero-sum game and then a trade-off between the protection of the labour force and the ability to gain financial solidity by transforming profits into reserves. Given the overwhelming preference in favour of employees, cooperative firms often worsen their well-known undercapitalization and their financial fragility, especially under prolonged periods of economic turbulence. The legislation may also strengthen the instruments easing their access to credit by means of sustaining their solidarity funds (see [

37] on the Italian experience).

Some limitations of our contribution implicitly point to extensions of our research. First, while we focus on panel data over the decade, one might detail the patterns of natality and mortality of cooperative firms, as compared to other types of business models. Second, it would be instructive to test whether our conclusions still hold once the overall sample is split among separate sectors, territories (e.g., regions) of firms by size. Finally, it seems worthwhile to look for other national experiences to measure the impact of macroeconomic shocks on cooperative firms by comparing countries with a non-negligible cooperative presence within their economies. We plan to address these extensions in our research agenda.