Navigating Paradoxes of Liveability: A Cross-Disciplinary Exploration of Urban Challenges in Jubail Industrial City

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background on Jubail Industrial City

1.2. Study Urban Liveability in the Industrial Context

1.3. Objectives of the Paper

- Theoretical Framework

1.4. What is Urban Liveability?

1.5. Dimensions of Liveability

1.5.1. Housing

1.5.2. Environment

1.5.3. Social Equity

1.6. Interdisciplinarity: Architecture, Sociology, Public Health, and Environmental Studies

1.6.1. Architecture

1.6.2. Sociology

1.6.3. Public Health

1.6.4. Environmental Studies

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design and Approach

2.2. Study Area

2.3. Quantitative Component

2.3.1. Survey Design

- Overall quality of life.

- Housing affordability and quality.

- Environmental quality (air, water, and green spaces).

- Access to essential services (education, healthcare, and transport).

- Safety and neighborhood cohesion.

- Opportunities for community engagement and decision-making.

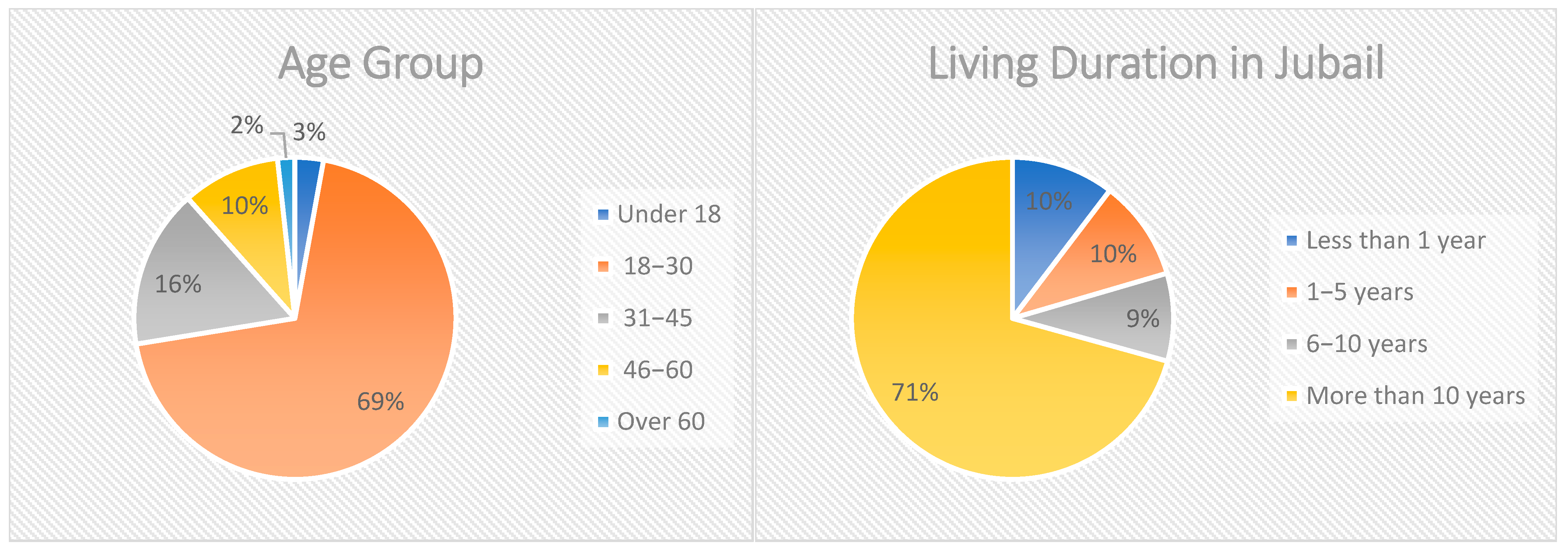

2.3.2. Sampling and Data Collection

2.3.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Qualitative Component

2.4.1. Data Collection

2.4.2. Qualitative Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

2.6. Methodological Integration

2.7. Limitations

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Current Challenges in Jubail

3.1.1. Housing Affordability

3.1.2. Impact on Environmental Sustainability

3.1.3. Social Equity and Inclusion

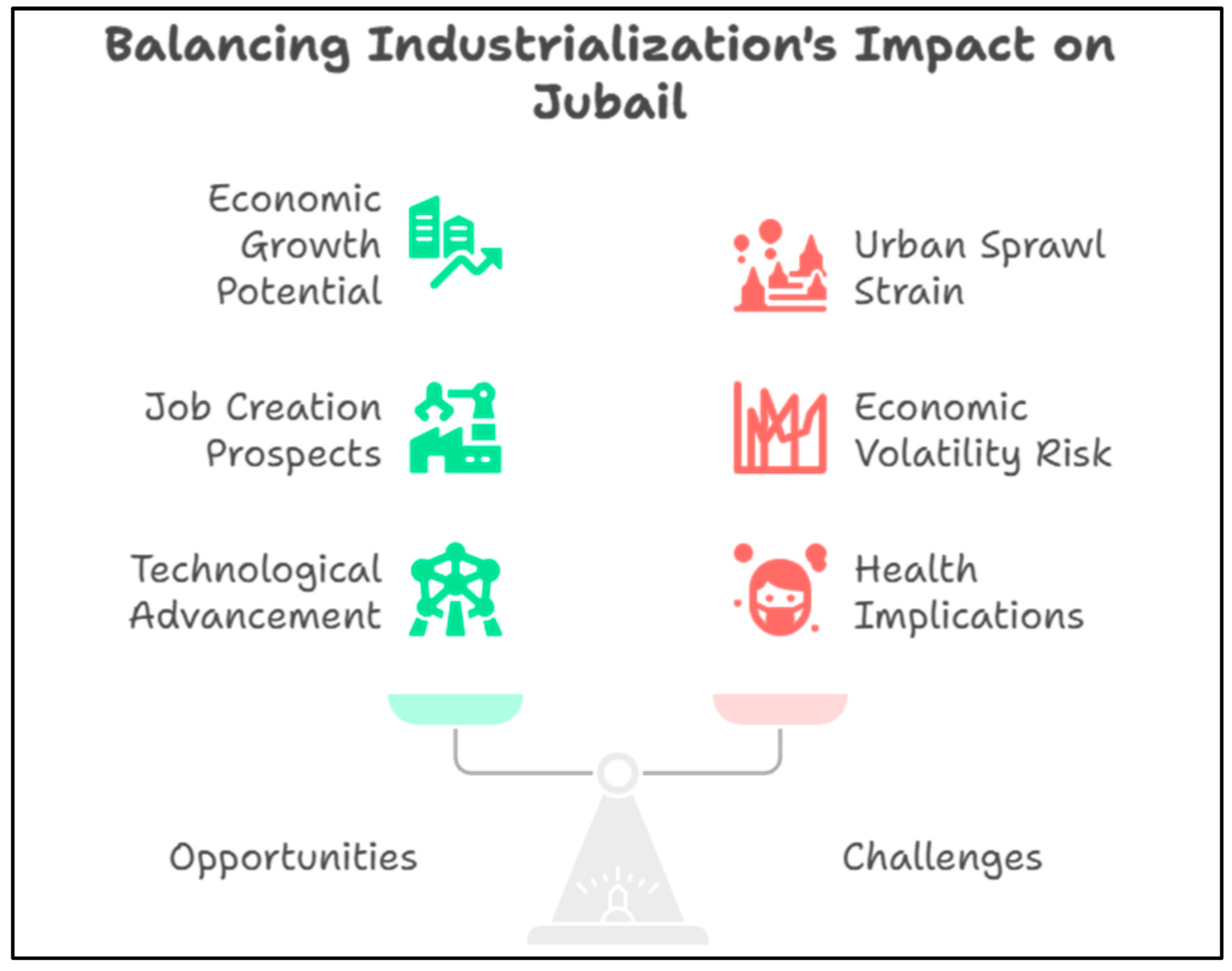

3.1.4. Impacts of Rapid Industrialization

3.2. What Residents Say About Liveability

3.2.1. Opinion Survey on Perceptions of Liveability

3.2.2. Analysis of Housing Conditions and Access to Services

3.2.3. Qualitative Insights from Open-Ended Questions

3.3. Environmental Analysis

3.3.1. Impact of Industrial Activities on Public Health

3.3.2. Analysis of Air and Water Quality Data

3.3.3. Sustainability Implications

4. Discussion

4.1. The Economic–Environmental Paradox

4.2. The Housing Equity Paradox

4.3. The Community Participation Paradox

4.4. Synthesis and Implications

5. Conclusions

5.1. Policy Recommendations for Enhancing Liveability in Jubail

5.1.1. Housing Affordability and Land Use Policies

5.1.2. Environmental Quality and Green Infrastructure

5.1.3. Mobility and Public Transport Integration

5.1.4. Social Equity and Community Engagement

5.1.5. Monitoring and Evaluation Framework

5.2. Expected Policy Impact

- Adaptive Governance—The capacity of institutions to respond flexibly to social and environmental change.

- Socio-Spatial Balancing—Planning interventions that align industrial productivity with residential well-being.

- Technological Mediation—Leveraging green and digital technologies to mitigate industrial externalities.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-But’hie, I.M.; Saleh, M.A.E. Urban and industrial development planning as an approach for Saudi Arabia: The case study of Jubail and Yanbu. Habitat Int. 2002, 26, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hathloul, S.; Mughal, M.A. Creating identity in new communities: Case studies from Saudi Arabia. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1999, 44, 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aina, Y.A.; Wafer, A.; Ahmed, F.; Alshuwaikhat, H.M. Top-down sustainable urban development? Urban governance transformation in Saudi Arabia. Cities 2019, 90, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alruwaili, A.S. Observing the Enablers for Achieving Sustainability in Saudi Oil Industry Cities According to Vision 2030 Aspirations: A Case Study of Jubail Industrial City. Emir. J. Eng. Res. 2025, 30, 4. Available online: https://scholarworks.uaeu.ac.ae/ejer/vol30/iss1/4/ (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Alshehri, R.M.; Alzenifeer, B.M.; Alqahtany, A.M.; Alrawaf, T.; Alsayed, A.H.; Afify, H.M.N.; Elmoghazy, Z.A.A.; Alshammari, M.S. Impact of Urban Green Spaces on Social Interaction Among People in Neighborhoods: Case Study for Jubail, Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassin, H.H. Livable city: An approach to pedestrianization through tactical urbanism. Alex. Eng. J. 2019, 58, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Regions in Industrial Transition, Policies for People and Places; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutfilter, A.F.; Krüger, C.; Taubitz, A.; Merten, F.; Halim, R.; Ahrend, R. Regional industrial transitions to climate neutrality. In OECD Regional Development Papers; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, W.T.; van Ameijde, J. Promoting livability through urban planning: A comprehensive framework based on the “theory of human needs”. Cities 2022, 131, 103972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodson, M.; Marvin, S. Urbanism in the anthropocene: Ecological urbanism or premium ecological enclaves? City 2010, 14, 298–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponzini, D. Transnational architecture and urbanism: Rethinking how cities plan, transform, and learn. In Transnational Architecture and Urbanism: Rethinking How Cities Plan, Transform, and Learn, Abingdoni; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 1–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torre, V.; Ponzini, D. 2020: Transnational Architecture and Urbanism: Rethinking How Cities Plan, Transform, and Learn. Abingdon: Routledge. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2021, 45, 745–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashef, M. Urban livability across disciplinary and professional boundaries. Front. Archit. Res. 2016, 5, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, H.; El-Sorogy, A.S.; Qaysi, S. Assessment of human health risks of toxic elements in coastal area between Al-Khafji and Al-Jubail, Saudi Arabia. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 196, 115622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aina, Y.A. Achieving smart sustainable cities with GeoICT support: The Saudi evolving smart cities. Cities 2017, 71, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shihri, F.S. Impacts of large-scale residential projects on urban sustainability in Dammam Metropolitan Area, Saudi Arabia. Habitat Int. 2016, 56, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altouma, A.; Bashir, B.; Ata, B.; Ocwa, A.; Alsalman, A.; Harsányi, E.; Mohammed, S. An environmental impact assessment of Saudi Arabia’s vision 2030 for sustainable urban development: A policy perspective on greenhouse gas emissions. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2024, 21, 100323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiq, M.K.M. Liveable City Centre: Livability through The Lens of The Singaporean Experience (Case of Singapore City Center). Eng. Res. J. 2022, 176, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-W. Can smart cities bring happiness to promote sustainable development? Contexts and clues of subjective well-being and urban livability. Dev. Built Environ. 2023, 13, 100108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Wang, Y.; Wu, K.; Yue, X.; Zhang, H.O. Livability-oriented urban built environment: What kind of built environment can increase the housing prices? J. Urban Manag. 2024, 13, 357–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.K.; Srivastava, I.A. Cities: Inclusive, Liveable, and Sustainable; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Roka, K. Liveable City: Towards Economic, Social, Cultural, and Environmental Well-being. In Sustainable Cities and Communities; Leal Filho, W., Azul, A.M., Brandli, L., Özuyar, P.G., Wall, T., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Jodder, P.K.; Hossain, M.Z.; Thill, J.-C. Urban Livability in a Rapidly Urbanizing Mid-Size City: Lessons for Planning in the Global South. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdipanah, R. Without affordable, accessible, and adequate housing, health has No foundation. Milbank Q. 2023, 101 (Suppl. S1), 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, P.; Tsouros, A.D. Promoting Physical Activity and Active Living in Urban Environments: The Role of Local Governments; WHO Regional Office Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Marchigiani, E. Healthy and caring cities: Accessibility for all and the role of urban spaces in re-activating capabilities. In Care and the City; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 75–87. [Google Scholar]

- Efroymson, D.; Rahman, M.; Shama, R. Making Cities More Liveable: Ideas and Action; HealthBridge: Grand Rapids, MI, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, E.; Franz, A.; O’Hara, S. Promoting social equity and building resilience through value-inclusive design. Buildings 2023, 13, 2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerow, S.; Pajouhesh, P.; Miller, T.R. Social equity in urban resilience planning. Local Environ. 2019, 24, 793–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-Y.E.; Chan, W.-W.V. Inclusive Management and Neighborhood Empowerment. In Inclusive Housing Management and Community Wellbeing: A Case Study of Hong Kong; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 259–307. [Google Scholar]

- Farahani, L.M. The value of the sense of community and neighbouring. Hous. Theory Soc. 2016, 33, 357–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, H. Linking the quality of public spaces to quality of life. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2009, 2, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deniz, D. Improving perceived safety for public health through sustainable development. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 216, 632–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antolín-López, R.; Martínez-Bravo, M.D.M.; Ramírez-Franco, J.A. How to make our cities more livable? Longitudinal interactions among urban sustainability, business regulatory quality, and city livability. Cities 2024, 154, 105358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, R.; Srijaroon, A.; Mousavi, S.H. Exploring the Benefits of Recreational Sports: Promoting Health, Wellness, and Community Engagement. J. Eval. Educ. (JEE) 2022, 3, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stodolska, M. Recreation for all: Providing leisure and recreation services in multi-ethnic communities. World Leis. J. 2015, 57, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akopov, A.S.; Beklaryan, L.A.; Saghatelyan, A.K. Agent-based modelling for ecological economics: A case study of the Republic of Armenia. Ecol. Model. 2017, 346, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, R.; Daly, L.; Fioramonti, L.; Giovannini, E.; Kubiszewski, I.; Mortensen, L.F.; Pickett, K.E.; Ragnarsdottir, K.V.; De Vogli, R.; Wilkinson, R. Modelling and measuring sustainable wellbeing in connection with the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 130, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, R.; Fioramonti, L.; Kubiszewski, I. The UN Sustainable Development Goals and the dynamics of well-being. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2016, 14, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, M.; Turaev, S.; Al-Dabet, S.; Abdulghafor, R. Multidimensional Assessment of Public Space Quality: A Comprehensive Framework Across Urban Space Typologies. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.21555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, N.; Girling, C.; Lu, Y. Urban form and livability: Socioeconomic and built environment indicators. Build. Cities 2021, 2, 220–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuhuber, T.; Schneider, A.E. Stratification of Livability: A Framework for Analyzing Differences in Livability Across Income, Consumption, and Social Infrastructure. Soc. Indic. Res. 2025, 177, 1051–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leby, J.L.; Hashim, A.H. Liveability dimensions and attributes: Their relative importance in the eyes of neighbourhood residents. J. Constr. Dev. Ctries. 2010, 15, 67–91. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/46817848_Liveability_dimensions_and_attributes_Their_relative_importance_in_the_eyes_of_neighbourhood_residents (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Zhan, D.; Kwan, M.-P.; Zhang, W.; Fan, J.; Yu, J.; Dang, Y. Assessment and determinants of satisfaction with urban livability in China. Cities 2018, 79, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Niaz, H.; Ahmad, S.; Khan, S. Investigating how Rapid Urbanization Contributes to Climate Change and the Social Challenges Cities Face in Mitigating its Effects. Rev. Appl. Manag. Soc. Sci. 2025, 8, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, D.; Enemark, S.; Van der Molen, P. Climate resilient urban development: Why responsible land governance is important. Land Use Policy 2015, 48, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perikangas, S.; Määttä, A.; Tuurnas, S. Ensuring social equity through service integration design. Public Manag. Rev. 2025, 27, 452–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geekiyanage, D.; Fernando, T.; Keraminiyage, K. Assessing the state of the art in community engagement for participatory decision-making in disaster risk-sensitive urban development. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 51, 101847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehmann, S. Sustainable building design and systems integration: Combining energy efficiency with material efficiency. In Designing for Zero Waste; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 209–246. [Google Scholar]

- Yahia, A.K.M.; Shahjalal, M. Sustainable materials selection in building design and construction. Int. J. Sci. Eng. 2024, 1, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Mazumdar, S.; Vasconcelos, A.C. Understanding the relationship between urban public space and social cohesion: A systematic review. Int. J. Community Well-Being 2024, 7, 155–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northridge, M.E.; Freeman, L. Urban planning and health equity. J. Urban Health 2011, 88, 582–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamukcu-Albers, P.; Ugolini, F.; La Rosa, D.; Grădinaru, S.R.; Azevedo, J.C.; Wu, J. Building green infrastructure to enhance urban resilience to climate change and pandemics. Landsc. Ecol. 2021, 36, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jubayl Population 2025. Available online: https://worldpopulationreview.com/cities/saudi-arabia/jubayl#sources (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Folke, C. Resilience: The emergence of a perspective for social–ecological systems analyses. Glob. Environ. Change 2006, 16, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fainstein, S.S. The Just City; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2011; p. 212. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. Social Justice and the City; Athens University of Georgia Press: Athens, GA, USA; Scientific Research Publishing: Wuhan, China, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Geels, F.W. Technological transitions as evolutionary reconfiguration processes: A multi-level perspective and a case-study. Res. Policy 2002, 31, 1257–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, I. Achieving readiness for organisational change. Libr. Manag. 2005, 26, 408–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giap, T.K.; Thye, W.W.; Aw, G. A New Approach to Measuring the Liveability of Cities: The Global Liveable Cities Index. World Rev. Sci. Technol. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 11, 176–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgs, C.; Badland, H.; Simons, K.; Knibbs, L.D.; Giles-Corti, B. The Urban Liveability Index: Developing a policy-relevant urban liveability composite measure and evaluating associations with transport mode choice. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2019, 18, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.G.; Woo, W.T.; Tan, K.Y.; Low, L.; Aw, G.E.L. Ranking the Liveability of the World’s Major Cities: The Global Liveable Cities Index (GLCI); World Scientific: Singapore, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Khorrami, Z.; Ye, T.; Sadatmoosavi, A.; Mirzaee, M.; Davarani, M.M.F.; Khanjani, N. The Indicators and Methods Used for Measuring Urban Liveability: A Scoping Review. Rev. Environ. Health 2021, 36, 397–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Phase | Method | Sample Size | Instrument | Key Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 | Quantitative survey | 457 residents | Structured questionnaire (Likert scale) | Statistical assessment of liveability indicators |

| Phase 2 | Qualitative responses | 457 participants | Semi-structured questions | Thematic insights into lived experiences |

| Integration | Mixed-methods synthesis | — | Comparative triangulation | Comprehensive model of liveability determinants |

| Area Evaluated | Satisfaction Mean |

|---|---|

| How satisfied are you with your overall quality of life in Jubail? | 4.13 |

| How would you describe the level of safety in your area? | 4.70 |

| How do you rate the air quality in Jubail? | 3.21 |

| Do you feel you have opportunities to participate in community decision-making? | 3.07 |

| How satisfied are you with the availability of essential services (healthcare, education, transportation) in your area? | 4.02 |

| How do you rate the availability of green spaces (parks, gardens) in your area? | 4.34 |

| How would you rate your social interaction with your neighbor? | 3.18 |

| How much does the surrounding environment affect your mental well-being? | 3.74 |

| Area Evaluated | Not Exist % | Exist % |

|---|---|---|

| Housing affordability | 37.5 | 62.5 |

| Air quality | 41.3 | 58.7 |

| Access to services | 63.5 | 36.5 |

| Overcrowding | 72.8 | 27.2 |

| Lack of green spaces | 87.3 | 12.7 |

| Area Evaluated | How Would You Describe the Level of Safety in Your Area? (Safety) | How do You Rate the Air Quality in Jubail? (Air Quality) | Do You Feel You Have Opportunities to Participate in Community Decision-Making? (Community Participation) | How Satisfied Are You with the Availability of Essential Services (Healthcare, Education, Transportation) in Your Area? (Services) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How satisfied are you with your overall quality of life in Jubail? | Correlation Coefficient | 0.352 ** | 0.459 ** | 0.330 ** | 0.514 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 (8.71 × 10−15) | 0.000 (3.48 × 10−25) | 0.000 (4.26 × 10−13) | 0.000 (3.94 × 10−32) | |

| N | 457 | 457 | 457 | 457 |

| Policy Area | Key Action | Lead Institution | Vision 2030 Alignment | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Housing | Inclusionary zoning and subsidies | RCJY | Housing Program | Affordable, mixed-income communities |

| Environment | Industrial audits and green buffers | RCJY/Saudi Green Initiative | Environmental Sustainability | Cleaner air and improved public health |

| Environment | Integrated public bus network | RCJY/Transport Ministry | Quality of Life Program | Reduced congestion and emissions |

| Social Inclusion | Community engagement platforms | RCJY/NGOs * | Thriving Society | Greater civic participation |

| Monitoring | Integrated public bus network | RCJY/SDG Unit | Vision Realization Office | Measurable progress tracking |

| Mechanism | Definition | Practical Application in Jubail |

|---|---|---|

| Adaptive Governance | Institutional capacity to respond to socio-environmental challenges through flexible policy mechanisms. | RCJY’s regulatory adaptability in environmental monitoring and social housing provision. |

| Socio-Spatial Balancing | Aligning industrial, residential, and environmental planning to reduce inequalities and enhance accessibility. | Strategic zoning and inclusionary housing policies linking residential areas to employment hubs. |

| Technological Mediation | Use of digital and green technologies to mitigate industrial externalities and improve quality of life. | Adoption of emission monitoring, renewable energy systems, and smart mobility pilots. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elantary, A.R. Navigating Paradoxes of Liveability: A Cross-Disciplinary Exploration of Urban Challenges in Jubail Industrial City. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10349. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210349

Elantary AR. Navigating Paradoxes of Liveability: A Cross-Disciplinary Exploration of Urban Challenges in Jubail Industrial City. Sustainability. 2025; 17(22):10349. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210349

Chicago/Turabian StyleElantary, Asmaa Ramadan. 2025. "Navigating Paradoxes of Liveability: A Cross-Disciplinary Exploration of Urban Challenges in Jubail Industrial City" Sustainability 17, no. 22: 10349. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210349

APA StyleElantary, A. R. (2025). Navigating Paradoxes of Liveability: A Cross-Disciplinary Exploration of Urban Challenges in Jubail Industrial City. Sustainability, 17(22), 10349. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210349