Abstract

The growing demand for natural gas and the corresponding expansion of pipeline networks have intensified the need for precise leak detection, particularly due to the increased vulnerability of infrastructure to natural disasters such as earthquakes, floods, torrential rains, and landslides. This research leverages deep learning to develop two hybrid architectures, the Transformer–LSTM Parallel Network (TLPN) and the Transformer–LSTM Cascaded Network (TLCN), which are rigorously benchmarked against Transformer and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) baselines. Performance evaluations demonstrate TLPN achieves exceptional metrics, including 91.10% accuracy, an 86.35% F1 score, and a 95.20% AUC value. Similarly, TLCN delivers robust results, achieving 90.95% accuracy, an 85.76% F1 score, and 93.90% of the Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC). These outcomes confirm the superiority of attention mechanisms and highlight the enhanced capability realized by integrating LSTM with Transformer for time-series classification. The findings of this research significantly enhance the safety, reliability, sustainability, and risk mitigation capabilities of buried infrastructure. By enabling rapid leak detection and response, as well as preventing resource waste, these deep learning-based models offer substantial potential for building more sustainable and reliable urban energy systems.

1. Introduction

The increasing demand for natural gas and expansion of pipeline networks pose significant hazards to public safety, infrastructure integrity, and environmental sustainability through potential gas leaks, with risks substantially amplified by natural disasters, including earthquakes, floods, torrential rains, and landslides. Timely and accurate detection is paramount to mitigate risks of fire, explosion, and resource wastage. Detection methods for gas leaks in pipeline networks are primarily categorized into hardware-based and software-based approaches, both of which are critically important and often interdependent [1].

The natural gas pipeline network, as a complex infrastructure, consists of an intricate physical structure and well-defined processes. The network itself is composed of a vast web of interconnected pipes that span long distances, transporting natural gas from production sources to end-users. Along this pipeline, various engineering components play crucial roles. Compressors are used for air pressure elevation, ensuring that the gas can flow smoothly over long distances against resistance. These compressors increase the pressure of the gas, which is essential for maintaining an appropriate volume flow rate. When it comes to the gas supply process, the pipeline network delivers gas to different consumption areas [2]. The flow of gas is carefully regulated, and flow meters are installed to measure the volume flow rate precisely. Pressure regulators are in place to adjust the gas pressure according to the requirements of different users and the characteristics of the pipeline. At the end-user side, the process of gas extraction occurs, where consumers access the natural gas for various purposes such as heating, power generation, and industrial production. In terms of the operating conditions, the pipeline network experiences a wide range of pressure, volume flow, temperature, and concentration conditions. Pressure conditions vary depending on the location in the pipeline, with higher pressures at the upstream near the production sources and compressors, and lower pressures at the downstream closer to the end-users [3]. Volume flow rates are determined by factors such as the demand from consumers and the capacity of the pipeline. Temperature can fluctuate due to environmental factors and the heat generated during the compression process. Additionally, the concentration of natural gas remains relatively stable within the pipeline, but any abnormal changes may indicate potential leaks or other issues, which highlights the importance of accurate leak detection [4].

The core of hardware detection methods relies on human or equipment perception, where a leak, as an abnormal condition, causes noticeable changes or anomalies in the perceived signal. Leak determination can often be made directly based on the perception signal, which avoids the need for complex signal processing or model analysis. Manual inspection represents a fundamental method in the gas industry involving safety inspectors who use their sense of smell, vision, or portable detection equipment to patrol pipelines, making subjective judgments about leaks. While its principle is simple and costs are low, this approach demands significant human resources and offers poor detection accuracy. It is mainly suitable for periodic inspections targeting major leaks or third-party damage. Other detection methods include acoustic sensors and optical fiber sensors. Mahmutoglu et al. designed a passive acoustics-based localization system specifically engineered to identify leakage points in subsea natural gas pipeline networks [5]. Their system utilized the acoustic signals generated by gas leaks, achieving a certain level of accuracy in detecting the leak location. Adegboye et al. demonstrated that dynamic simulation approaches can effectively identify pipeline leaks with remarkable precision [6]. This framework systematically incorporates diverse elements ranging from fluid properties to ambient conditions and pipeline attributes to assess critical performance indicators such as volumetric flow, pressure gradients, and temperature distributions.

To enhance gas detection precision, machine learning algorithms have been extensively employed in pipeline leakage monitoring systems. Back-propagation neural networks (BPNN) have been experimented with and discussed for leak detection in pipelines. In their comparative study, Santos et al. examined the effectiveness of feedforward neural architectures and radial basis networks in pinpointing gas pipeline leaks, with the objective of refining detection precision [7]. Chen et al. demonstrated that SVM classification outperformed conventional methods when applied to pipeline leak detection and localization tasks, yielding superior accuracy in both aspects [8]. Fernandes et al. employed a dual machine learning approach, combining a supervised artificial neural network with unsupervised self-organizing maps, to analyze signal patterns in pipeline monitoring data, finding that the unsupervised method demonstrated better performance [9]. A new accelerometer-enabled monitoring solution was presented by El-Zahab et al. for water distribution pipelines, incorporating decision trees and naive Bayes for data interpretation, successfully detecting virtually all leak occurrences [10]. Focusing on the critical process of feature extraction, Xu et al. developed a novel acoustic detection approach for identifying pipeline gas leaks, which incorporated the calculation of significant temporal parameters such as arithmetic averages and dispersion metrics [11]. Wang et al. used time-domain statistical features for pipeline leak detection [12]. For monitoring complex pipeline infrastructures, Lay-Ekuakille’s group applied the filter diagonalization approach to enhance leak identification capabilities [13].

In the field of deep learning, Lee et al. proposed an innovative solution combining RNN-LSTM deep learning models analyzing meter inflow data with dynamic threshold adjustment modules, achieving substantial improvements in prediction reliability [14]. Applied to actual data, the model shows over 90% accuracy at most points, enabling quick leak recognition. A supervised OPELM-BiLSTM hybrid model was established by Yang et al. as a novel solution for PPA leak detection. The OPELM is used for the first-stage detection due to its fast learning and good classification performance. BiLSTM is employed in the second stage to identify false alarms by leveraging its strong memorizing ability. Experiments show this method achieves higher accuracy with fewer false alarms compared to existing ML-based PPA methods [15]. Vynnykov et al. employed artificial neural networks to study the safe life of industrial (metal) structures under long-time operation in the corrosive-active media of oil and gas wells [16]. They used the MATLAB R2023b system for interface modeling and the “with teacher” learning process. An artificial neural network helped obtain a generalized diagram of the expected areas of high viscoplastic characteristics of carbon steels used in the oil and gas industry. The trained neural networks were used to obtain generalized dependences of the corrosion rates of structural steels on the parameters of media with different ion concentrations, which were the basis for predicting corrosion behavior. The research highlighted the importance of neural network analysis in handling complex data with non-linear relationships. It also demonstrated that neural networks can expand the range of predicted values beyond experimental data, although the error increases with the distance from the experimental data scope. This is consistent with the general understanding that neural networks can capture complex patterns in data, which is valuable for time-series classification tasks such as gas leakage and biogas accumulation. In the field of pipeline-related research, Colorado-Garrido et al. used neural networks for Nyquist plots prediction during corrosion inhibition of a pipeline steel, showing the effectiveness of neural networks in pipeline-related data analysis [17]. Liao et al. developed a numerical corrosion rate prediction method for direct assessment of wet gas gathering pipelines’ internal corrosion using a neural-network-based approach, which further emphasized the potential of neural networks in handling pipeline-related time-series data [18].

However, the studies above predominantly rely on conventional machine learning models, necessitating architectural innovations to develop more effective models for gas detection that minimize false alarms. This study addresses this gap by introducing a novel deep learning model incorporating attention mechanisms for the identification of both gas leakage and biogas accumulation.

2. Methodology

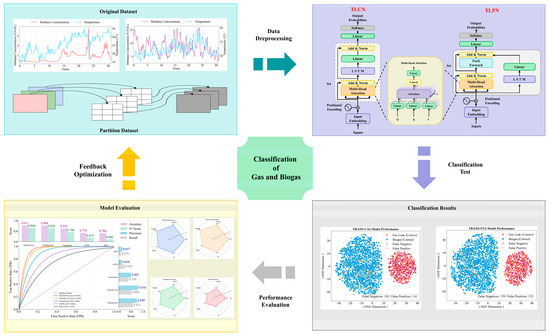

This study seeks to develop robust deep learning models for the critical task of binary classification within time series data representing gas leakage and biogas accumulation events. The primary workflow initiates with essential data preprocessing steps, which clean and normalize the input sequences, ensuring optimal model performance. Following this, various deep learning architectures were constructed, with the primary models comprising a Transformer—LSTM Parallel Network (TLPN), a parallel fusion model integrating Transformer and LSTM; and Transformer—LSTM Cascaded Network (TLCN), a serial cascade model combining these components. Each model needs to undergo strict training and use the validation set to perform hyperparameter tuning to achieve the best configuration. The final stage involves evaluating the classification efficacy through comparative testing on an independent test set. To visually elucidate this entire process, a flowchart is presented, offering a clear schematic representation, which is shown in Figure 1. Subsequently, the fundamental principles and operational mechanics of each model are thoroughly introduced, providing insights into their unique design and application within the study.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the deep learning method of classification of gas leakage and biogas accumulation.

2.1. Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM)

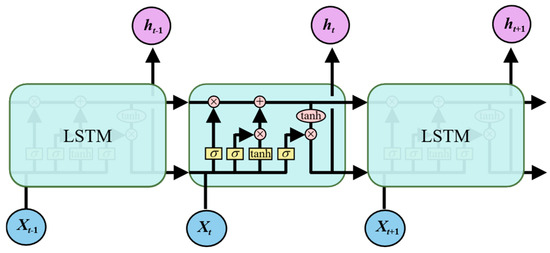

In 1997, Hochreiter et al. developed the Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) architecture as a solution to fundamental challenges in conventional recurrent neural networks, most notably the gradient explosion issues that arose during backpropagation through extended temporal sequences [19]. As shown in Figure 2, the fundamental improvement in LSTM architecture centers on its novel approach to memory management through gated cellular structures. LSTM cells overcome this by employing three adaptive gates: the Forget Gate clears unnecessary historical data, the Input Gate admits valuable new information, and the Output Gate governs information propagation. This configuration creates a robust cell state mechanism that acts as an information preservation channel, allowing sustained gradient transmission through time [20]. This architecture makes LSTMs exceptionally well-suited for time series classification. Their ability to capture and retain long-term contextual patterns, selectively remember relevant features while discarding noise or irrelevant short-term fluctuations, and model complex, non-linear temporal dynamics enables them to learn discriminative features from sequential data effectively [21].

Figure 2.

Structure of LSTM [19].

2.2. Transformer

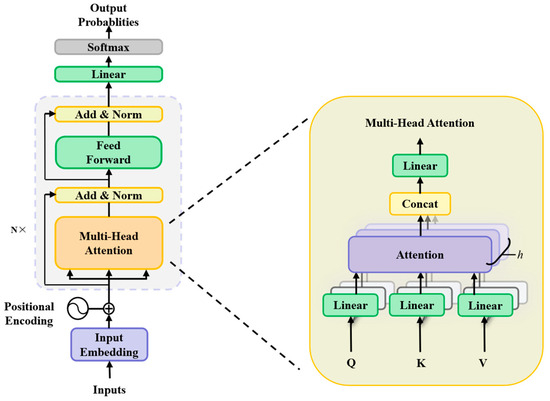

Emerging in 2017 as a revolutionary architecture that fundamentally departed from the sequential processing paradigm constraining LSTM, the Transformer addressed critical LSTM limitations, including inherent difficulties in parallelizing training computations and persistent struggles with capturing extremely long-range dependencies despite sophisticated gating mechanisms [22]. For time series classification tasks requiring the assignment of a single label to an entire temporal sequence based on its evolving patterns, the Transformer offers significant advantages stemming from its ability to process all time points simultaneously during training, its explicit modeling of relationships between any temporally distant elements via self-attention, and its superior capacity for learning global context often diminished in LSTMs over extended intervals [23,24]. The core Transformer architecture originally comprised stacked encoder and decoder layers designed for sequence generation; however, as shown in Figure 3, time series classification constitutes a sequence-to-label problem where only the encoder component proves necessary for extracting rich, contextualized representations of the input sequence without any requirement for the target sequence generation functionality housed within the decoder [25,26].

Figure 3.

Structure of transformer and the multi-head attention mechanism [26].

While traditional attention mechanisms process information in a unified representation space, the encoder’s Multi-Head Attention introduces parallel attention heads that independently learn to attend to different feature dimensions across sequence positions, significantly expanding its modeling capabilities. We begin with the input matrices: queries , keys , and values , where n and m denote sequence lengths. For each attention (where i = 1, 2, …, h), we linearly project , , and using learnable weight matrices , respectively. This yields head-specific projections:

where and ensure computational efficiency. For each head, we compute the scaled dot-product attention:

The softmax operates row-wise, and scaling by mitigates vanishing gradients for large . The outputs of all h heads are concatenated into a combined matrix . Finally, this concatenated output is projected back to the original dimensionality using a learnable matrix :

This mechanism operates by projecting the input into multiple independent sets of Queries, Keys, and Values through separate learned linear transformations, allowing each parallel attention head to specialize in identifying different types of temporal relationships such as short-term volatility, persistent long-term trends, recurring seasonal patterns, or complex interactions among multiple sensor channels [27]. Subsequently, the outputs generated by these independently functioning heads are concatenated and linearly projected, synthesizing diverse insights into a unified representation highly conducive to classification. Multi-Head Attention renders the Transformer exceptionally suitable for time series classification because it dynamically learns context-dependent weights signifying the importance of different time steps and features [28], facilitates robust recognition of discriminative patterns spanning arbitrary durations irrespective of their distance, naturally accommodates intricate multivariate dependencies, and exhibits inherent resilience to noise or irrelevant fluctuations through its content-adaptive filtering [29], ultimately empowering the model to discern subtle, long-range temporal signatures critical for accurate categorization.

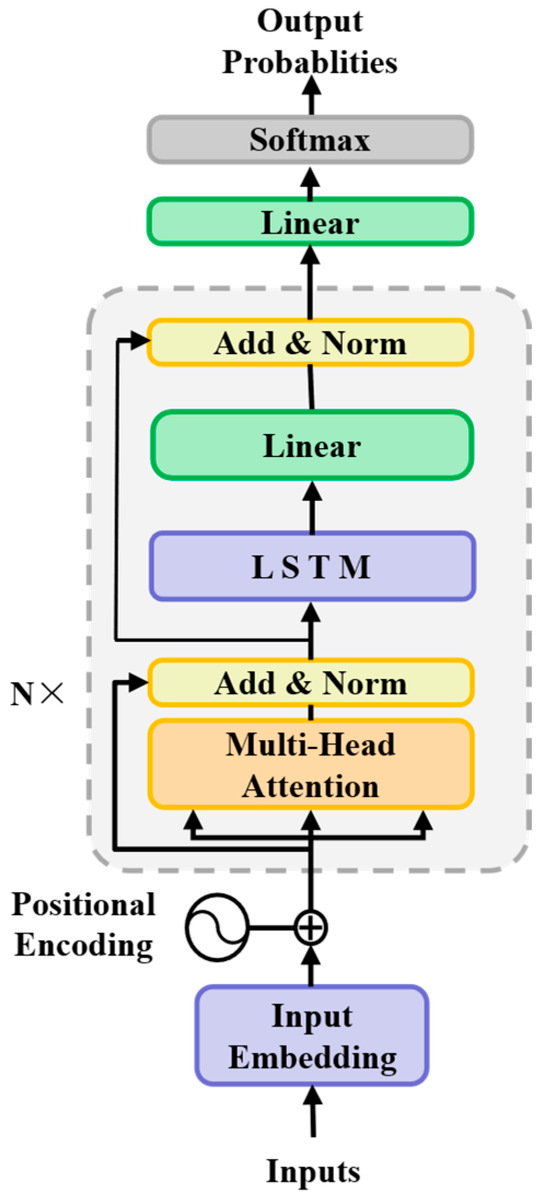

2.3. Transformer–LSTM Cascaded Network (TLCN)

The Transformer–LSTM Cascaded Network (TLCN), illustrated in Figure 4, employs a sequential processing architecture wherein a Transformer module processes the entire input sequence first, and its output is subsequently fed as the exclusive input to an LSTM network. This design capitalizes on the complementary temporal modeling strengths inherent in each component. The Transformer module initiates the processing by ingesting the raw multivariate time series input. Utilizing its multi-head self-attention mechanism, the Transformer computes interactions between every pair of time steps within the input window concurrently [30].

Figure 4.

Structure of TLCN.

This enables the effective capture of long-range temporal dependencies across the entire sequence, identifying correlations between sensor readings at widely separated time points, which is essential for recognizing the gradual pressure changes or slow gas concentration buildups characteristic of developing gas leak scenarios. The output from the Transformer stage is a transformed sequence where each time step’s representation incorporates information derived from its relationship to all other steps, effectively encoding a global temporal perspective [31].

Critically, this transformed sequence serves as the input for the subsequent LSTM module. Unlike the Transformer’s parallel processing, the LSTM inherently operates sequentially, processing the input one time step at a time in strict chronological order. The LSTM’s gating mechanisms specialize in modeling local temporal dynamics, capturing the intricate patterns, short-term fluctuations, and the precise order of events occurring over adjacent or closely spaced time steps. The strategic placement of the LSTM after the Transformer fundamentally optimizes its operation. By receiving the Transformer’s output—a sequence already imbued with resolved long-range dependencies—the LSTM is liberated from the challenging task of establishing these distant temporal correlations directly from raw, potentially noisy sensor data. This task often proves difficult for standalone LSTMs due to vanishing gradients and sequential processing constraints. Consequently, the LSTM can concentrate its full representational capacity on refining the local temporal structure present within the globally informed sequence. It focuses exclusively on learning discriminative features related to the immediate evolution of the signal, such as the sharp, rapid spikes in gas concentration indicative of sudden biogas accumulation events or subtle transient patterns preceding a detectable leak, which demand high sensitivity to local order and short-term trends. This targeted local refinement, operating on a sequence where long-range context is already established, mitigates a limitation of standalone Transformers whose attention mechanisms, while powerful for global dependencies, may not inherently prioritize the critical nuances of immediate temporal transitions and fine-grained sequential evolution with the same efficacy as recurrent architectures [32].

The sequential cascade thus establishes a synergistic hierarchical feature extraction process: the Transformer excels at discerning macro-scale temporal patterns and dependencies spanning the entire sequence window, effectively addressing the long-range modeling deficiency of standalone LSTMs. The succeeding LSTM, operating on this sequence enriched with global temporal context, excels at capturing micro-scale dynamics and fine-grained temporal evolution, compensating for a potential weakness in standalone Transformers concerning precise local order sensitivities. For heterogeneous time series data characteristic of gas monitoring—exhibiting both slow-evolving global trends and critical localized anomalies—this division of labor is theoretically advantageous. The Transformer provides a comprehensive understanding of overarching temporal relationships, while the LSTM meticulously analyzes the detailed, step-by-step progression of the signal within that global framework. This integrated approach yields representations significantly more robust to noise and capable of capturing the multifaceted temporal signatures essential for accurate binary classification of leak/accumulation events versus normal operation. The final classification decision is derived from the processed output of the LSTM module [33].

2.4. Transformer–LSTM Parallel Network (TLPN)

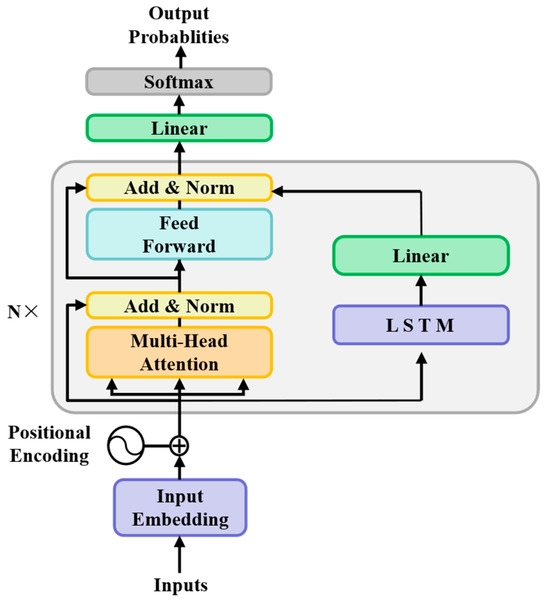

Building upon TLCN, we designed TLPN, which is a parallel feature fusion model integrating Transformers and LSTMs. TLPN operates through a dedicated Transformer branch, which captures global spatiotemporal dependencies via multi-headed self-attention mechanisms, and a dedicated LSTM branch, which extracts local temporal dynamics and sequential transitions. Both branches process the same raw input sequences concurrently, thereby eliminating the inherent sequential computational bottlenecks characteristic of cascaded architectures [34].

As shown in Figure 5, this design fundamentally deploys two co-processing branches operating directly on raw input time series: the Transformer pathway leverages multi-headed self-attention mechanisms to model complex, long-term temporal dependencies spanning extended durations—an essential capability for identifying slow-evolving methane concentration drifts in landfill gas accumulation scenarios, while simultaneously, the dedicated LSTM branch captures rapid temporal variations and localized transient patterns through its recurrent gating operations, enabling precise detection of abrupt changes characteristic of pipeline fissure-induced gas leaks. Such parallel execution circumvents computational bottlenecks inherent in cascaded designs while ensuring maximal retention of both macro-scale trends essential for identifying chronic emission patterns and micro-scale anomalies critical for explosive risk prevention [35].

Figure 5.

Structure of TLPN.

Feature integration occurs through a dynamically trainable fusion module where concatenated embeddings from both pathways are adaptively synthesized. This gated fusion mechanism employs attention-based recalibration to dynamically weigh the contributions of each branch’s output based on their discriminative significance for specific temporal signatures. During operation, the system intrinsically amplifies the LSTM branch when resolving sudden pressure transients requiring millisecond-level sensitivity—frequently encountered in leakage scenarios—while prioritizing Transformer-derived features when detecting gradual concentration shifts spanning days or weeks that indicate hazardous biogas accumulation. This selective feature amplification proves indispensable for mitigating environmental noise inherent in industrial sensor data, substantially boosting model robustness against meteorological variability and measurement disturbances.

The mathematical formulation governing feature fusion is expressed as

where and denote the high-dimensional temporal representations generated by the Transformer and LSTM branches, respectively. The attention weight matrix and bias vector generate normalized contribution coefficients through sigmoid activation (σ). The projection matrices and transform domain-specific vectors prior to Hadamard product (⊙) operations with attention weights, while ⊕ signifies vector concatenation. The fused representation undergoes GELU activation for enhanced non-linear expressiveness [36].

This architecture demonstrates critical advantages over its predecessors by maintaining the integrity of temporal feature hierarchies. Unlike sequential configurations, where preprocessing by a Transformer branch may irreversibly attenuate high-frequency signal components—severely detrimental when resolving explosion-risk-relevant pressure spikes—TLPN preserves full-spectrum temporal information through unprocessed inputs feeding both branches. The dedicated LSTM channel maintains high-fidelity reconstruction of microsecond-level leakage signatures without distortion from potentially over-smoothed representations, while the Transformer arm concurrently captures sustained concentration variations beyond the receptive field of recurrent units. This architecture proves exceptionally powerful for time series classification because its parallel dual-branch design comprehensively captures multi-resolution features spanning extended contexts and immediate transitions [37].

3. Case Studies

3.1. Data Sources and Features

We obtained data on natural gas leakage and biogas accumulation from the city of Hefei, spanning the period from December 2020 to December 2021. Crucially, while both phenomena involve the release of methane (CH4), their sources and fundamental characteristics differ: natural gas, primarily composed of methane (typically 80–95%) with minor alkanes, originates from deep fossil fuel reserves and is distributed via pipelines; biogas, conversely, is produced through the anaerobic decomposition of organic matter in settings like landfills, wastewater treatment plants, or agricultural digesters, with methane content generally ranging between 60 and 75% alongside significant quantities of carbon dioxide (CO2), moisture, and trace gases.

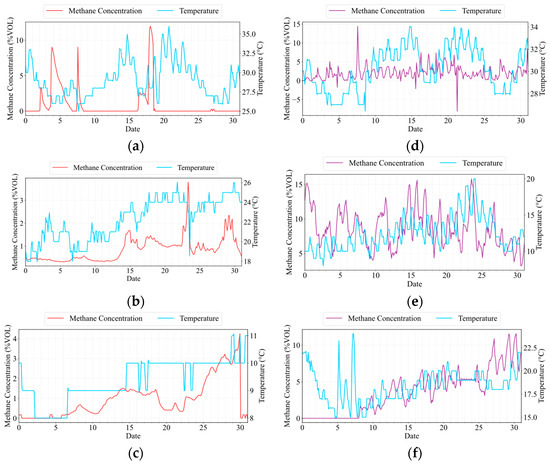

The natural gas leakage monitoring data originates from 33 spatially distinct locations across Hefei. Each monitored location corresponds to a dedicated gas analyzer paired with an integrated temperature sensor, implying the deployment of 33 independent sets of instrumentation. These monitoring sites were strategically distributed across diverse urban environments typical of Hefei’s metropolitan landscape, encompassing densely populated residential districts with aging infrastructure, commercial zones featuring complex piping networks, newly developed industrial parks, and transportation corridors where excavation risks exist. Simultaneously, biogas accumulation data was collected from 18 specific sites, predominantly located in peri-urban or rural fringes of Hefei. These sites were characterized by their association with organic matter decomposition sources, including operational municipal solid waste landfills undergoing active filling, digesters within wastewater treatment facilities, and agricultural locations managing livestock manure. Detailed methane concentration profiles and temperature variations during characteristic natural gas leakage episodes were captured over one-month intervals at representative sites RQ4336, RQ5220, and RQ1853, as visually presented in Figure 6a–c. Parallel datasets, illustrating biogas accumulation through methane concentration and temperature profiles, were compiled from sites RQ8651, WS08003019, and YS022508631, as depicted in Figure 6d–f. In Figure 6, the horizontal axis represents time over a one-month period, the left vertical axis indicates methane concentration in the gas mixture, while the right vertical axis displays temperature measurements.

Figure 6.

Changes in methane concentration and temperature with time in the scene of gas leakage/biogas accumulation at different locations. (a) Gas leakage at RQ4336 in July 2021. (b) Gas leakage at RQ5220 in June 2021. (c) Gas leakage at RQ1853 in February 2021. (d) Biogas accumulation at RQ8651 in August 2021. (e) biogas accumulation at WS08003019 in May 2021. (f) Biogas accumulation at YS022508631 in March 2021.

Detailed analysis, as discussed previously, confirms a fundamental operational distinction: methane concentration profiles resulting from pipeline natural gas leaks exhibit no consistent correlation with concurrent temperature fluctuations, whereas biogas methane concentrations typically demonstrate a pronounced positive correlation with diurnal and seasonal thermal variations. Consequently, gas leakage profiles often display abrupt, non-periodic methane spikes followed by a rapid decline, signaling a point source release and prompt remediation efforts upon detection. Biogas accumulation, influenced by biological activity whose rate is temperature-dependent, manifests more gradual methane concentration changes, frequently exhibiting cyclical patterns that maintain elevated levels for extended durations.

3.2. Data Preprocessing

The collected data of gas leakage and biogas accumulation at different locations need multidimensional data cleaning. Linear interpolation fills isolated points using adjacent data, spline interpolation handles short gaps of 2–5 consecutive points while retaining fluctuation characteristics, and segments exceeding 10 missing points undergo removal with annotation unless occurring during critical periods of gas leak alarms, where spatial interpolation supplements adjacent sensor data. For outlier management, the Z-score method identifies anomalies; temperature readings beyond the empirically defined [−20, 50] °C threshold are replaced with the location-specific monthly median when concurrent sensor readings validate normal conditions. Negative methane concentrations undergo elimination, whereas anomalous methane values coinciding with high-level alarms are retained as valid signals; others are substituted with sliding window means. Signal smoothing applies moving averaging with a window size of 5 to temperature and methane concentration fields, preserving trends while filtering high-frequency noise. Discrete alarm levels remain unsmoothed, though severe noise may necessitate Savitzky–Golay filtering, a method superior in peak retention and waveform fidelity whose parameters require grid search optimization. Each data table receives a categorical label—designated “0” for gas leakage and “1” for biogas accumulation—before vertical integration of all 58 tables into a single shuffled dataset comprising timestamp, temperature, methane concentration, alarm level, and category columns, thereby preventing order-induced bias.

Sliding window implementation precedes feature engineering to mitigate temporal data leakage risks and counteract class imbalance stemming from gas leakage samples versus abundant biogas accumulation instances. Window parameters reflect distinct event dynamics: gas leak events, characterized by rapid methane/temperature surges and transient high alarms, necessitate short windows of 30 min length with 15 min steps, whereas biogas accumulation manifests as gradual methane increases and sustained high alarms, requiring extended 90 min windows with 45 min steps. Zero-padding aligns shorter gas leak windows to the 90 min biogas window length for dimensional consistency during batch processing. Sample labeling employs methane concentration thresholds within windows to accurately identify leakage events, preventing erroneous associations between normal data patterns and gas leakage labels. Feature engineering extracts domain-specific attributes: timestamps undergo sine encoding of hourly and weekly cyclical components to capture temporal dependencies; temperature and methane yield statistical features, including mean, variance, extrema, first-order differences, trend slope, and zero-crossing rates; alarm levels contribute features such as count and temporal proportion of level ≥1 occurrences alongside maximum level. All features undergo Z-score standardization to eliminate scale disparities. Finally, the dataset undergoes strict location-based partitioning (7:2:1 training/validation/test ratio) using stratified sampling to preserve class balance, isolate sites completely across subsets, and rigorously evaluate model generalization to unseen locations during deployment.

4. Model Validation and Result Analysis

4.1. Evaluation Indicators

The rigorous assessment of deep learning architectures demands a multi-dimensional analytical approach wherein each metric quantifies distinct aspects of classification efficacy. A nuanced understanding of confusion-matrix-derived metrics, complemented by ROC/AUC threshold analysis and t-SNE visual diagnostics, is essential to determine operational viability for safety-critical gas detection systems where false negatives precipitate catastrophic outcomes while false alarms incur economic penalties [38,39]. This holistic methodology reveals architectural strengths in capturing complex temporal dependencies within sensor data, thereby guiding optimal model deployment.

4.1.1. Confusion Matrix

A confusion matrix, which is a tabular representation of a classifier’s predictions versus actual labels, provides granular insights into model performance. It partitions outcomes into four categories: True Positives (TP, correctly identified leaks), False Positives (FP, safe conditions misclassified as leaks), True Negatives (TN, correctly identified safe states), and False Negatives (FN, undetected leaks). For gas leak detection, this matrix quantifies critical errors—especially FN, which represent hazardous missed detections—and forms the basis for deriving all subsequent metrics. Its structural clarity enables targeted model refinement by isolating specific failure modes.

4.1.2. Accuracy

Accuracy represents the proportion of correctly classified samples among all samples, which can be referred to as ACC. It is a classification metric of a model on a population sample that includes all categories. The calculation formula is as follows [40]:

4.1.3. Precision

The precision metric is mathematically defined as the number of true positives divided by the sum of true and false positives in classification outcomes, denoted as PRE. The higher the accuracy, the higher the recognition accuracy. Precision, or positive predictive value, evaluates the reliability of leak alarms:

It penalizes false alarms (FP), which trigger unnecessary interventions in industrial settings. High precision is essential for operational efficiency, as frequent false positives erode user trust and incur economic costs. However, precision does not account for missed leaks (FN), necessitating integration with recall [41].

4.1.4. Recall

The recall rate represents the proportion of correctly classified samples among samples with true labels, denoted as REC. Recall quantifies the model’s ability to detect actual leaks:

Also termed sensitivity, it directly addresses safety risks by minimizing undetected hazards (FN). In gas monitoring, maximizing recall is paramount due to the severe consequences of leaks. Yet, an isolated focus on recall may increase false alarms, highlighting the need for balance with precision [42].

4.1.5. F1 Score

The F1 score harmonizes precision and recall via their harmonic mean:

This metric mitigates biases from class imbalance by equally weighting false alarms and missed leaks. For safety-critical tasks like gas detection, F1 offers a balanced view of model efficacy, penalizing extremes where high recall sacrifices precision or vice versa [43].

4.1.6. ROC Curve

The Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve is constructed by plotting the hit rate (TPR) against the false alarm rate (FPR) across all possible decision boundaries:

Each point on the curve represents a trade-off between leak detection (TPR) and false alarms (FPR). In gas monitoring, the ROC curve visualizes how threshold adjustments impact safety (prioritizing TPR) versus operational stability (suppressing FPR). An ideal curve hugs the top-left corner, reflecting simultaneous high sensitivity and low false alarms [44].

4.1.7. AUC

The Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC) summarizes overall discriminative power:

where t denotes the classification threshold. AUC values range from 0.5 to 1.0 (perfect separation). For time-series models like TLPN or LSTM, AUC evaluates threshold-agnostic class separation capability. High AUC indicates robust leak identification regardless of threshold selection, which is vital for deployment in dynamic environments with varying risk tolerance [45].

4.1.8. t-SNE Visualization

Projects high-dimensional latent representations into 2D/3D space using probability distributions to preserve local similarities:

The algorithm minimizes Kullback–Leibler divergence between high-dimensional () and low-dimensional () distributions. For model diagnostics, t-SNE reveals clustering fidelity: well-separated leak/non-leak clusters indicate effective feature extraction, while overlapping clusters expose architectural weaknesses like RNN’s inability to capture long-range dependencies. Critically, t-SNE helps identify “confusion zones” where gas concentration patterns mislead simpler models—enabling targeted data augmentation or architecture modifications [46].

4.2. Result Analysis

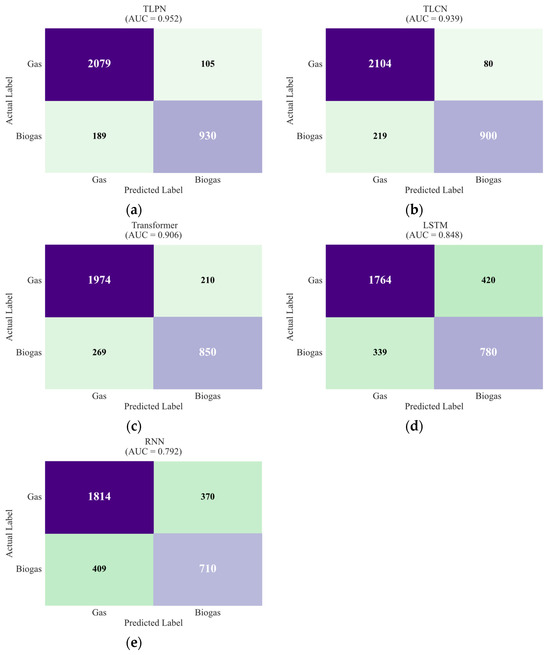

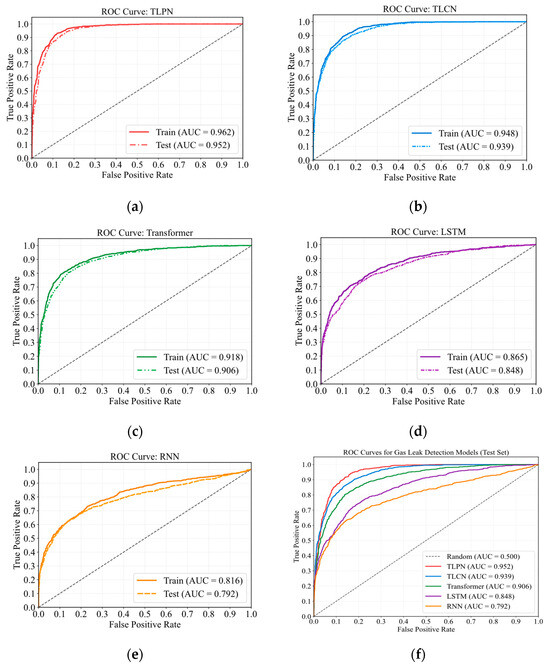

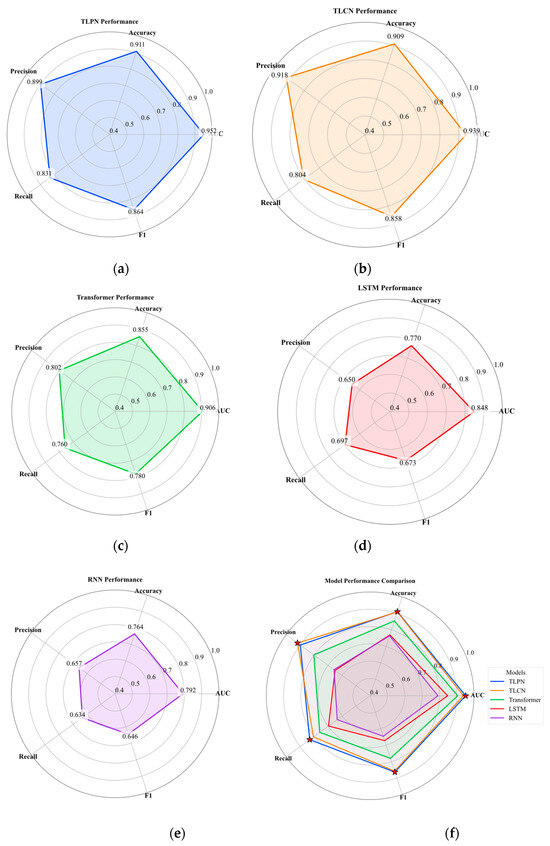

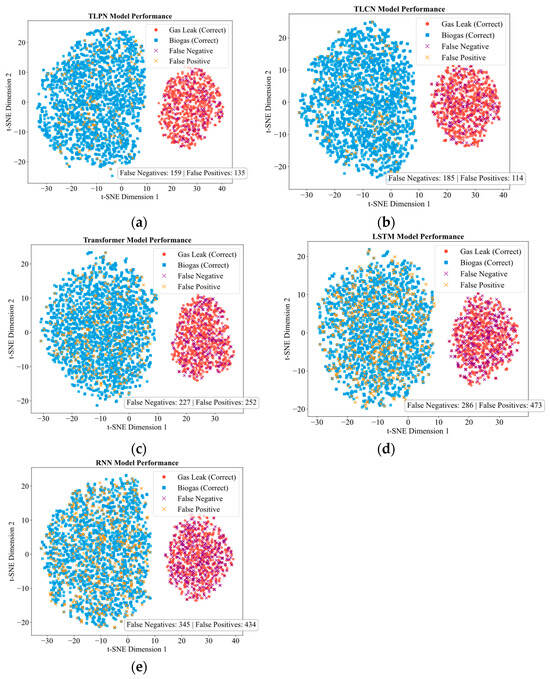

In this study, experimental data were annotated with gas leakage instances designated as positive class samples and biogas accumulation events labeled as negative class samples. The test set comprised 3303 samples, exhibiting a positive-to-negative class ratio of 1:1.95. This ratio allowed deriving the confusion matrix for each model, as shown in Figure 7. We subsequently analyzed these confusion matrices to obtain the fundamental classification metrics—TP, TN, FP, and FN. These values subsequently enabled the calculation of key performance indicators—accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score, which are given in Table 1. To further evaluate model discrimination capability, ROC curves were plotted, and the corresponding AUC values were computed. The result is depicted in Figure 8. A comprehensive comparative analysis of the five distinct gas leakage detection models revealed significant performance differences. These variations are attributable to inherent structural disparities within their underlying architectures, each model exhibiting unique operational characteristics.

Figure 7.

Confusion matrix of each deep learning model. (a) TLPN. (b) TLCN. (c) Transformer. (d) LSTM. (e) RNN.

Table 1.

Comparison of ACC, PRE, REC, and F1 score of each model.

Figure 8.

ROC Curve of each deep learning model. (a) TLPN. (b) TLCN. (c) Transformer. (d) LSTM. (e) RNN. (f) Comparison between models.

As shown in Table 1, TLPN achieves the highest accuracy of 91.10%, precision of 89.86%, recall of 83.11%, F1 score of 86.35%, and AUC of 95.20%, establishing itself as the most effective solution for gas leak detection among the evaluated models. This exceptional performance stems from its fusion architecture that likely integrates multiple data modalities or feature representations, enabling the model to capture complex patterns and dependencies that simpler architectures might miss. The high recall rate, which indicates minimal false negatives, proves particularly valuable in safety-critical applications where missing actual leaks could have severe consequences.

TLCN follows closely as the second-best performer with an impressive precision of 91.84% that slightly exceeds TLPN, though it shows marginally lower recall and overall accuracy. Its cascaded architecture, which processes information through sequential refinement stages, provides excellent precision but appears to trade off some sensitivity compared to the fusion approach. The standard Transformer model, which achieves solid but unexceptional results, demonstrates the fundamental strength of attention mechanisms in capturing long-range dependencies, though its performance plateau suggests limitations in handling the specific patterns of gas sensor data without specialized architectural enhancements [47].

Both recurrent models exhibit substantially weaker performance, with LSTM showing the lowest precision and RNN demonstrating the poorest overall results across all metrics. These traditional sequence modeling approaches, which rely on sequential processing and hidden state transitions, struggle to capture the complex temporal dependencies present in gas detection data, with their inherent challenges in learning long-term patterns leading to higher rates of both false positives and false negatives. The significant performance gap between the transformer-based models and recurrent architectures highlights the transformative impact of attention mechanisms that allow direct modeling of relationships across all time steps regardless of distance [48].

While accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 scores provide valuable snapshots of model performance at specific decision thresholds, AUC offers a more comprehensive evaluation that addresses critical limitations inherent in threshold-dependent metrics. Unlike accuracy, which becomes unreliable with imbalanced datasets, or precision-recall metrics, which require careful threshold tuning, the AUC metric delivers a robust assessment of overall model discrimination capability that remains invariant to class distribution and decision threshold selection, making it particularly valuable for evaluating gas leak detection systems where operational conditions may vary. Figure 8 shows that the close alignment between training and test ROC curves across all models, which demonstrates exceptional generalization capability and inherent model strengths in feature extraction. This indicates the models effectively capture intrinsic patterns in gas sensor data rather than memorizing noise, which is critical for safety applications requiring reliable performance across diverse environmental conditions and deployment scenarios [49].

TLPN achieves the highest AUC value of 95.2%, demonstrating exceptional classification performance that significantly outperforms other architectures. This superior discriminative ability stems from its innovative fusion mechanism that integrates multi-scale feature representations through cross-attention modules, allowing the model to capture complex temporal dependencies and subtle pattern variations in gas sensor data that might indicate leakage events [50]. TLCN follows closely with an AUC of 93.9%, leveraging its cascade architecture where successive transformer layers refine feature representations through hierarchical processing, though its slightly lower performance suggests minor information loss occurs during this sequential transformation process compared to the parallel feature integration approach of TLPN. The base Transformer model achieves a respectable AUC of 90.6%, confirming the fundamental effectiveness of self-attention mechanisms in processing time-series sensor data. Its performance differential from the enhanced transformer variants highlights the value of specialized architectural modifications for gas leak detection tasks [51]. The LSTM model attains an AUC of 84.8%, reflecting its ability to capture medium-range temporal dependencies through gated memory cells, though its recurrent nature imposes sequential processing constraints that limit parallelization and context aggregation. The RNN model shows the weakest performance with an AUC of 79.2%, suffering from vanishing gradient problems that impede its capacity to learn long-range dependencies in sensor data sequences, resulting in inadequate feature representation for subtle gas leak patterns that evolve over extended time periods [52].

The performance hierarchy revealed by the AUC values directly correlates with each model’s architectural sophistication and its alignment with the data characteristics of gas leak detection. The dominant transformer-based models excel due to their self-attention mechanisms that enable simultaneous processing of all time steps and dynamic weighting of feature importance, capabilities particularly suited for identifying complex gas dispersion patterns. Meanwhile, the recurrent models exhibit diminishing returns as sequence length increases, struggling to maintain relevant information across extended time windows critical for early leak detection [53].

The performance improvements of TLPN and TLCN compared to Transformer and LSTM, respectively, are presented in detail in Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5. TLPN and TLCN hybrid architectures exhibit marked performance enhancements over standalone Transformer and LSTM models across critical classification metrics. Relative to the Transformer baseline, TLPN elevates AUC by 5.08%, accuracy by 6.55%, and F1 score by 10.68%. TLCN demonstrates moderately lower gains, achieving a 3.64% AUC improvement, 6.37% accuracy increase, and 9.92% F1 score enhancement.

Table 2.

Comparison of performance between TLPN and Transformer.

Table 3.

Comparison of performance between TLPN and LSTM.

Table 4.

Comparison of performance between TLCN and Transformer.

Table 5.

Comparison of performance between TLCN and LSTM.

When compared to the LSTM baseline, both fusion architectures deliver substantially more pronounced advancements. TLPN attains a 12.26% AUC elevation, 18.28% accuracy augmentation, and 28.37% F1 score progression. TLCN similarly improves AUC by 10.73%, accuracy by 18.08%, and F1 score by 27.48%.

This observed performance hierarchy, TLPN surpassing TLCN, which in turn exceeds Transformer, followed by LSTM, and finally RNN, is fundamentally attributable to the distinct capabilities of each architecture in capturing the heterogeneous temporal dependencies inherent in gas sensor time series. The RNN suffers severely from vanishing gradients, drastically limiting its capacity to model the long-term, slow-evolving pressure trends indicative of developing gas leaks. While the LSTM mitigates this issue through gating mechanisms, its inherent sequential processing imposes computational constraints and struggles with exceptionally long-range correlations or rapidly fluctuating signals such as the sharp localized spikes characteristic of sudden biogas accumulation events. Consequently, standalone LSTMs often fail to fully correlate distant precursor events with eventual consequences or react optimally to rapid transient anomalies [54].

The Transformer excels at modeling such long-range temporal dependencies across the entire input window. However, its global weighting mechanism may inadequately prioritize the precise local order and immediate sequential transitions essential for recognizing the exact morphology of rapid biogas spikes or subtle short-duration precursor patterns preceding detectable leak thresholds. This inherent characteristic explains the significant leap achieved by both hybrid models. TLCN’s sequential cascade design, where the Transformer first resolves comprehensive long-range dependencies, allows the subsequent LSTM to specialize exclusively in refining local temporal dynamics such as short-term fluctuation rates of change and the exact sequence of sensor responses within this globally informed representation. This focused local refinement proves critical for accurately classifying events demanding high sensitivity to immediate temporal evolution [55].

Nevertheless, TLPN’s parallel fusion architecture consistently outperforms TLCN’s sequential approach primarily due to its more flexible and information-rich integration strategy. TLPN processes the input simultaneously through dedicated Transformer and LSTM pathways, preserving the original unprocessed signal alongside both global dependency encodings and local sequential dynamics. The Transformer pathway captures the broad, slow-changing temporal patterns vital for leak detection, while the LSTM pathway concurrently models the fine-grained grained rapidly evolving sequences characteristic of biogas accumulation [53]. A subsequent adaptive fusion mechanism dynamically learns optimal weightings for these complementary representations, potentially emphasizing global context for gradual leak signatures and local dynamics for abrupt accumulation spikes based on the specific input segment characteristics. This parallel processing and adaptive fusion mitigate potential information loss inherent in TLCN’s fixed sequential flow, where the LSTM processes only the Transformer-derived representation. Consequently, TLPN achieves superior harmonization of precision and recall reflected in its highest F1 scores, making it exceptionally robust for detecting the complex heterogeneous temporal patterns, slow global drifts intertwined with critical local anomalies that define gas safety events in real-world sensor data. The empirical results decisively validate that hybrid architectures, particularly the parallel fusion embodied in TLPN, offer the most effective solution for capturing the multifaceted temporal dependencies essential in safety-critical gas detection systems [56].

Based on the radar plot analysis of classification performance across five deep learning models, as shown in Figure 9, TLPN demonstrates exceptional overall performance, which manifests as the polygon with the most expansive coverage across all five evaluation metrics, exhibiting a notably symmetrical and convex pentagonal shape that reflects its remarkably balanced predictive power. TLCN maintains substantial but slightly diminished coverage. Its pentagon shows noticeable constriction along the Recall dimension, indicating marginally inferior sensitivity in detecting positive gas leak instances. This limitation stems from its sequential cascade design, where feature transformations occur in ordered stages [55]. During propagation through successive processing layers, critical low-level signal characteristics may be discarded compared to the parallel fusion approach. The standard Transformer model produces a smaller symmetrical polygon, moderating performance reflects limitations in processing localized acoustic events within long sequences, lacking specialized temporal feature extractors. LSTM exhibits a distorted shape with significant Precision and F1 weaknesses. This reveals problems with false positives, as its forget gates sometimes discard critical short leak signatures during long sequence processing. RNN forms the smallest, most concave polygon with poor Recall and Precision, whose fundamental limitations stem from vanishing gradient issues and error accumulation during sequential processing, hindering reliable leak detection [56].

Figure 9.

Radar map of each deep learning model. (a) TLPN. (b) TLCN. (c) Transformer. (d) LSTM. (e) RNN. (f) Radar map comparison of the above models (The points with the best performance are represented by “★”).

Figure 10 indicates that TLPN exhibits exceptionally crisp cluster separation, where distinct crimson gas leak points form an isolated island surrounded by deep blue biogas accumulations. This visual clarity corresponds with impressively balanced error rates: merely 159 false negatives and 135 false positives, representing the most reliable performance. TLCN demonstrates well-defined clusters featuring moderately scattered gas leak points along boundary regions. Achieving the lowest false positive rate at 114 showcases its precision strength, though 185 false negatives reveal occasional missed detections near transition zones. The cascade attention mechanism delivers conservative classification that prioritizes safety by minimizing false alarms while sometimes overlooking ambiguous peripheral samples. Progressing to Transformer, we observe noticeable boundary blurring where gas leak samples penetrate deep into biogas territory, creating hybrid regions. It’s 227 false negatives and 252 false positives reflect self-attention mechanisms that capture global patterns but struggle with local feature discrimination. While identifying broad relationships effectively, this architecture occasionally misinterprets blended characteristics, causing boundary confusion [57].

Figure 10.

Visualized classification results by t-SNE. (a) TLPN. (b) TLCN. (c) Transformer. (d) LSTM. (e) RNN.

In contrast, LSTM displays severe cluster overlap resembling merging nebulae. This visual chaos correlates with an alarming 473 false positives and 286 false negatives. The recurrent architecture’s temporal focus proves fundamentally inadequate for spatial separation tasks, generating excessive false alarms, particularly near cluster cores. And RNN presents near-total homogenization where both classes intermix randomly without discernible patterns. Catastrophic 345 false negatives and 434 false positives confirm its architectural poverty, with primitive recurrent connections failing to establish any meaningful decision boundaries across the feature space.

Crucially, TRANS models demonstrate architectural superiority through specialized attention mechanisms. TLPN integrates multimodal features via cross-attention layers that resolve complex pattern interactions, while TLCN employs sequential processing that progressively refines feature representations. These innovations maintain cluster integrity where conventional models fail, proving essential for safety-critical applications demanding minimal false alarms and missed detections [57].

The practical deployment of TLPN and TLCN in complex, variable gas pipeline environments necessitates rigorous evaluation of their scalability and adaptability beyond classification metrics. TLPN’s parallel architecture inherently supports superior scalability for large-scale distributed sensor networks. By processing Transformer and LSTM pathways simultaneously, TLPN minimizes sequential computation bottlenecks, enabling efficient parallelization across hardware accelerators like GPUs. This design proves critical when handling high-frequency multi-sensor data streams from kilometers of pipelines, where latency constraints demand real-time anomaly detection. Conversely, TLCN’s sequential cascade—requiring full Transformer computation before LSTM execution—introduces inherent latency that escalates with input sequence length, potentially compromising responsiveness in dynamic scenarios such as rapid biogas accumulation events where milliseconds influence mitigation efficacy.

Regarding adaptability, TLPN’s fusion layer dynamically recalibrates feature weights between global dependency modeling and local transient detection. This allows autonomous adjustment to unseen operational shifts—for example, adapting to seasonal methane concentration fluctuations or unforeseen sensor drift by amplifying the Transformer pathway’s influence during gradual leak development while prioritizing LSTM-derived local features for sudden hydrogen sulfide spikes. TLCN, though competent in stable environments, exhibits rigidity in its fixed processing order; the LSTM module cannot access raw sensor data directly, limiting its capacity to reinterpret local anomalies when the Transformer’s global context extraction is skewed by noisy or novel signal patterns. Consequently, TLPN demonstrates enhanced resilience in heterogeneous pipelines integrating legacy and modern sensing infrastructures, where signal heterogeneity and intermittent data quality variations are prevalent.

Ultimately, TLPN’s architectural flexibility offers greater operational longevity in evolving pipeline ecosystems. Its parallel pathways simplify incremental updates—such as retraining only the LSTM module for new sensor types—while TLCN’s tightly coupled stages necessitate full model redeployment for similar adaptations. This scalability-adaptability synergy positions TLPN as a more sustainable solution for future-proofing safety-critical gas monitoring systems against emerging technological and environmental variabilities.

5. Conclusions

With the escalating demand for natural gas and the expansion of pipeline networks, gas leakage has become a significant threat to public safety, infrastructure integrity, and environmental sustainability. This risk is further exacerbated by natural disasters such as earthquakes, floods, torrential rains, and landslides. Consequently, accurate detection of gas leakage and the differentiation from biogas accumulation are of paramount importance. The comparative analysis conducted in this study reveals a clear performance hierarchy among the models for classifying gas leak (positive class) versus biogas accumulation (negative class) in time series data. Hybrid Transformer–LSTM architectures, particularly TLPN and TLCN, demonstrate superior capabilities in distinguishing hazardous gas leaks from benign biogas accumulation. Their high AUC values and balanced precision-recall trade-offs make them well-suited for safety-critical industrial monitoring applications.

When compared to the Transformer model, TLPN achieves a 5.1% improvement in AUC, a 6.6% increase in accuracy, and a substantial 10.7% enhancement in the F1 score. Against the LSTM model, these improvements are even more pronounced: TLPN shows a 12.3% higher AUC, an 18.3% surge in accuracy, and an impressive 28.4% in the F1 score. TLCN outperforms the baseline models, achieving a 3.6% AUC improvement, a 6.4% accuracy increase, and a 9.9% enhancement in the F1 score compared to the Transformer model. Against the LSTM benchmark, TLCN registers a 10.7% AUC gain, an 18.1% accuracy improvement, and a 27.5% F1 score increase. Standalone Transformer models, which rely solely on self-attention mechanisms, also deliver commendable classification performance. However, the hybrid architectures that strategically integrate LSTM modules achieve significantly enhanced predictive accuracy, demonstrating the synergistic potential of combining attention-based feature extraction with recurrent network components. In contrast, traditional LSTM and RNN models perform considerably worse, struggling to detect key patterns in the data that indicate gas leaks, highlighting a major limitation in models lacking advanced attention mechanisms.

In conclusion, the hybrid models, particularly TLPN, provide a promising solution for gas leak detection. Their ability to capture complex temporal dependencies makes them well-suited for safety-critical applications. However, the current study also has certain technical limitations. The models are mainly tested on the dataset from Hefei, and their generalization ability to other regions with different environmental and pipeline conditions needs further verification. Additionally, although the hybrid models improve performance, there is still room for reducing false positives and false negatives, especially in complex scenarios where gas leak characteristics are more ambiguous. Future research could focus on optimizing these models by fine-tuning the architecture, incorporating more diverse data sources, and improving the adaptability of the models to different environments. This would enhance their performance and robustness in real-world scenarios.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z. and W.W.; methodology, Y.Z. and W.W.; software, Y.Z.; validation, Y.Z.; formal analysis, Y.Z.; investigation, Y.Z.; resources, W.W.; data curation, Y.Z., K.S. and W.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Z., K.S. and W.W.; writing—Y.Z., K.S. and W.W.; visualization, Y.Z.; supervision, W.W.; project administration, W.W.; funding acquisition, W.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grants No. 2023YFC3807602), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 72442008, 72404160).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TLPN | Transformer–LSTM Parallel Network |

| TLCN | Transformer–LSTM Cascaded Network |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| BPNN | Back-propagation neural networks |

| SVM | Support vector machine |

| RNN-LSTM | Recurrent Neural Network-Long Short-Term Memory |

| OPELM | Optimally Pruned Extreme Learning Machine |

| BiLSTM | Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory |

| AE | Acoustic Emission |

| CWT | Continuous Wavelet Transform |

| GA | Genetic Algorithm |

| TP | True Positives |

| FP | False Positives |

| TN | True Negatives |

| FN | False Negatives |

| ROC | The Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| TPR | True Positive Rate |

| FPR | False Positive Rate |

| AUC | The Area Under the ROC Curve |

| t-SNE | t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding |

References

- Meng, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, W.; Fu, J. Experimental study on leak detection and location for gas pipeline based on acoustic method. J. Loss Prev. Process. Ind. 2012, 25, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Cui, Z.; Fang, L.; Li, Y.; Xu, M. Leak localization approaches for gas pipelines using time and velocity differences of acoustic waves. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2019, 103, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Zhang, L.; Liang, W.; Ding, Q. Integrated leakage detection and localization model for gas pipelines based on the acoustic wave method. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2014, 27, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Li, Y.; Yan, Y.; Fu, J. A new leak location method based on leakage acoustic waves for oil and gas pipelines. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2015, 35, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmutoglu, Y.; Turk, K. A Passive Acoustic Based System to Locate Leak Hole in Underwater Natural Gas Pipelines. Digit. Signal Process. 2018, 76, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegboye, M.A.; Fung, W.K.; Karnik, A. Recent Advances in Pipeline Monitoring and Oil Leakage Detection Technologies: Principles and Approaches. Sensors 2019, 19, 2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, R.B.; Rupp, M.; Bonzi, S.J.; Fileti, A.M. Comparison between multilayer feedforward neural networks and a radial basis function network to detect and locate leaks in pipelines transporting gas. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2013, 32, 1375–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Ye, H.; Chen, L.V.; Su, L.Y. Application of support vector machine learning to leak detection and location in pipelines. In Proceedings of the 21st IEEE Instrumentation and Measurement Technology Conference, Como, Italy, 18–20 May 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, L.B.; da Silva, F.V.; Fileti, A.M.F. Diagnosis of Gas Leaks by Acoustic Method and Signal Processing. In Computer Aided Chemical Engineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Zahab, S.; Abdelkader, E.M.; Zayed, T. An accelerometer-based leak detection system. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2018, 108, 276–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Liang, W. Acoustic detection technology for gas pipeline leakage. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2013, 91, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Lin, W.; Liu, Z.; Wu, S.C.; Qiu, S.B. Pipeline Leak Detection by Using Time-Domain Statistical Features. IEEE Sens. J. 2017, 17, 6431–6442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lay-Ekuakille, A.; Pariset, C.; Trotta, A. Leak detection of complex pipelines based on the filter diagonalization method: Robust technique for eigenvalue assessment. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2010, 21, 115403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.W.; Yoo, D.G. Development of Leakage Detection Model and Its Application for Water Distribution Networks Using RNN-LSTM. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhao, Q. A novel PPA method for fluid pipeline leak detection based on OPELM and bidirectional LSTM. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 107185–107199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vynnykov, Y.; Kharchenko, M.; Manhura, S.; Aniskin, A.; Manhura, A. Neural network analysis of safe life of the oil and gas industrial structures. Min. Miner. Depos. 2024, 18, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colorado-Garrido, D.; Ortega-Toledo, D.M.; Hernández, J.A.; González-Rodríguez, J.G.; Uruchurtu, J. Neural networks for Nyquist plots prediction during corrosion inhibition of a pipeline steel. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2009, 13, 1715–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, K.; Yao, Q.; Wu, X.; Jia, W.L. A Numerical Corrosion Rate Prediction Method for Direct Assessment of Wet Gas Gathering Pipelines Internal Corrosion. Energies 2012, 5, 3892–3907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long Short-Term Memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gers, F.A.; Schmidhuber, J.; Cummins, F. Learning to Forget: Continual Prediction with LSTM. Neural Comput. 2000, 12, 2451–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sak, H.; Senior, A.; Beaufays, F. Long Short-Term Memory Based Recurrent Neural Network Architectures for Large Vocabulary Speech Recognition. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1402.1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. arXiv 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katharopoulos, A.; Vyas, A.; Pappas, N.; Fleuret, F. Transformers are RNNs: Fast Autoregressive Transformers with Linear Attention. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.16236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerveas, G.; Jayaraman, S.; Patel, D.; Bhamidipaty, A.; Eickhof, C. A Transformer-based Framework for Multivariate Time Series Representation Learning. In Proceedings of the 27th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, Singapore, 14–18 August 2021; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.H.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, B.; Ark, S.; Loeff, N.; Pfister, T. Temporal Fusion Transformers for interpretable multi-horizon time series forecasting. Int. J. Forecast. 2021, 37, 1748–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zhang, S.; Peng, J.; Zhang, S.; Li, J.X.; Xiong, H.; Zhang, W.C. Informer: Beyond Efficient Transformer for Long Sequence Time-Series Forecasting. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2012.07436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, Y.; Dehghani, M.; Bahri, D.; Metzler, D. Efficient Transformers: A Survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, F.; Majumdar, S.; Darabi, H.; Chen, S. LSTM Fully Convolutional Networks for Time Series Classification. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 1662–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guen, V.L.; Thome, N. Shape and Time Distortion Loss for Training Deep Time Series Forecasting Models. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 32, Volume 6 of 20: 32nd Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2019), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Jin, X.; Xuan, Y.; Zhou, X.; Chen, W.; Wang, Y.X.; Yan, X. Enhancing the Locality and Breaking the Memory Bottleneck of Transformer on Time Series Forecasting. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 32, Volume 7 of 20: 32nd Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2019), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Franceschi, J.Y.; Dieuleveut, A.; Jaggi, M. Unsupervised Scalable Representation Learning for Multivariate Time Series. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 32, Volume 6 of 20: 32nd Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2019), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, C.; Meng, S.; Hu, X.; Wang, X.; Zhong, Y. Cropnet: Deep Spatial-Temporal-Spectral Feature Learning Network for Crop Classification from Time-Series Multi-Spectral Images. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 26 September–2 October 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingphai, K.; Moshfeghi, Y. On Time Series Cross-Validation for Deep Learning Classification Model of Mental Workload Levels Based on EEG Signals; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foumani, N.M.; Miller, L.; Tan, C.W.; Webb, G.; Forestier, G.; Salehi, M. Deep Learning for Time Series Classification and Extrinsic Regression: A Current Survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 56, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hespeler, S.C.; Nemati, H.; Masurkar, H.D.N.E. Deep Learning-Based Time-Series Classification for Robotic Inspection of Pipe Condition Using Non-Contact Ultrasonic Testing. J. Nondestruct. Eval. Diagn. Progn. Eng. Syst. 2024, 7, 11002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kam, H.J.; Kim, H.Y. Learning representations for the early detection of sepsis with deep neural networks. Comput. Biol. Med. 2017, 89, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasaka, K.; Akai, H.; Kunimatsu, A.; Obe, O.; Kiryu, S. Deep learning for staging liver fibrosis on CT: A pilot study. Eur. Radiol. 2018, 28, 4578–4585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choo, H.; Lee, K.H.; Hong, S.; Lee, K.B.; Chang, Y.L. Beyond the ROC Curve: Activity Monitoring to Evaluate Deep Learning Models in Clinical Settings. Appl. Med. Inform. 2024, 46, S9–S12. [Google Scholar]

- Li, A.; Feng, C.; Xu, S.; Cheng, Y. Graph t-SNE multi-view autoencoder for joint clustering and completion of incomplete multi-view data. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2024, 284, 111324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Ali, M.; Naseem, U.; Bosques Palomo, B.A.; Monsivais Molina, M.A.; Garza Abdala, J.A.; Avendano Avalos, D.B.; Cardona-Huerta, S.; Aaron Gulliver, T.; Tamez Pena, J.G. Performance Evaluation of Deep Learning and Transformer Models Using Multimodal Data for Breast Cancer Classification. In MICCAI Workshop on Cancer Prevention Through Early Detection; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Xu, M.; Li, R. Deep Learning for Household Load Forecasting—A Novel Pooling Deep RNN. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2017, 9, 5271–5280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, N.; Li, T.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, X. Medformer: A Multi-Granularity Patching Transformer for Medical Time-Series Classification. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 36314–36341. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, C.; Li, L.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, T.; Li, P. FBG Tactile Sensing System Based on SVP-Transformer for Material Classification. IEEE Sens. J. 2025, 25, 5370–5379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Qiu, F.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y. Multiscale spatial-temporal transformer with consistency representation learning for multivariate time series classification. Concurr. Pract. Exp. 2024, 36, e8234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Meng, R.; Li, R.; Dai, L.; Shen, F.; Yuan, J.; Sun, D.; Li, M.; Fu, C.; Li, R.; et al. Multitask deep learning model based on multimodal data for predicting prognosis of rectal cancer: A multicenter retrospective study. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2025, 25, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdomo, O.; Rios, H.; Rodríguez, F.J.; Otálora, S.; Meriaudeau, F.; Müller, H.; González, F.A. Classification of diabetes-related retinal diseases using a deep learning approach in optical coherence tomography. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2019, 178, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Xu, Z.; Wang, C.; Guo, J. Leak Prediction Method for Gas Pipelines Based on an Improved Transformer. In Proceedings of the 2024 6th International Conference on Video, Signal and Image Processing, Ningbo, China, 22–24 November 2024; pp. 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, S.; Hou, J.; Wang, J.; Zhao, M. Intelligent identification of internal leakage in natural gas pipeline control valves based on Mamba-ARN. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 198, 107113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Huang, J.; Sun, L.; Yao, Y.; Zhu, F.; Xie, F.; Zhang, M. An Improved Convolutional Neural Network for Pipe Leakage Identification Based on Acoustic Emission. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Shang, Z.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Weng, G.; Zhao, S.; Bi, C. Research on Leak Detection and Localization Algorithm for Oil and Gas Pipelines Using Wavelet Denoising Integrated with Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM)–Transformer Models. Sensors 2025, 25, 2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Chen, J.; Yang, D.; Hu, Z.; Wang, P.; Wang, D. Two-dimensional small leak detection of pipeline based on time sequence coding. Flow Meas. Instrum. 2024, 97, 102572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Chu, S.; Wang, J.; Shi, M.; Huang, D.; Song, W. MD-Former: Multiscale Dual Branch Transformer for Multivariate Time Series Classification. Sensors 2025, 25, 1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Wei, Y.; Li, T.; Zheng, X.; Ji, C. A hierarchical transformer-based network for multivariate time series classification. Inf. Syst. 2025, 132, 102536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snider, E.J.; Hernandez-Torres, S.I.; Boice, E.N. An image classification deep-learning algorithm for shrapnel detection from ultrasound images. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 8427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, A.H.; Chen, J.R.; Liu, S.H.; LU, C.; Lin, C.; Shieh, J.; Weng, W.; Tsui, P. Deep Learning of Ultrasound Imaging for Evaluating Ambulatory Function of Individuals with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, X. Self-Supervised Time Series Classification Based on LSTM and Contrastive Transformer. Wuhan Univ. J. Nat. Sci. 2022, 27, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).