1. Introduction

The rapid global growth of tourism in recent years has sparked significant debates concerning environmental sustainability. According to the United Nations World Tourism Organization [

1] the number of international tourists is expected to reach 1.8 billion by 2030. This growing volume of travel exacerbates environmental challenges such as carbon emissions, energy and water consumption, waste generation, and the degradation of natural habitats. Consequently, scholarly interest in sustainable tourism consumption has intensified. However, the existing literature reveals substantial limitations in translating sustainability principles from the theoretical level into practical implementation [

2]. Questions regarding how tourist behavior can be transformed, to what extent consumption practices can be rendered sustainable, and through which social groups such a transformation might occur remain highly relevant. In the existing literature, sustainable tourism consumption is predominantly examined through the lens of individual behaviors, consumer choices, corporate practices, and public policies [

3,

4]. Much of this research focuses on analyzing consumers’ environmental awareness, inclination toward green preferences, and eco-ethical behaviors, while also measuring the formation of demand for sustainable products and destinations [

5,

6]. However, these approaches largely concentrate on understanding current visitor behaviors, offering only limited conceptual or empirical insights into the generations that will shape future practices. Furthermore, the literature emphasizes that the development of sustainable tourism behaviors is influenced not only by environmental awareness but also by individual value systems, attitudes, and social norms [

6]. Aligning tourism consumption with sustainability principles has become increasingly critical, particularly considering the growing environmental impacts of mass tourism [

7]. However, the success of sustainability policies depends not only on supply-side interventions but also on demand-side transformations, namely the behavioral shifts in tourists. Within this transformation process, younger generations particularly Generation Z emerge as key actors with significant potential to drive sustainable tourism consumption [

8,

9]. Research on sustainable tourism consumption among Generation Z should not only address existing behavioral patterns but also focus on young people’s perceptions, value systems, and orientations toward sustainability, thereby contributing to the development of a more holistic perspective. Such studies may foster more participatory approaches to the future of tourism while considering its environmental impacts. Although recent scholarship has increasingly examined young people’s sustainability values, Han et al. [

10] the imaginaries of Generation Z in relation to tourism, namely their mental representations of the future and their alternative constructions of destinations remain underexplored in the literature. Yet, this generation consists of individuals who have grown up immersed in digital platforms, confronted global crises at an early age, and developed heightened environmental awareness. Critical approaches such as “tourism imaginaries” [

11] highlight that individuals’ expectations and imaginaries of travel are shaped through cultural values, media images, and societal discourses. In this context, the imaginaries of younger generations are open to analysis at both symbolic and practical levels.

This study aims to explore how Generation Z envisions sustainable tourism and to understand how these imaginaries reflect the values associated with responsible tourism consumption. Within this framework, the study seeks to answer the following questions:

What common themes of imagined sustainable tourism destinations are revealed through the symbolic elements embedded in Generation Z’s visual narratives?

How can the forms of transportation, accommodation, consumption, and interactions with the environment that emerge in Generation Z’s utopias be evaluated within the context of responsible tourism consumption?

What alternative propositions do Generation Z’s future imaginaries offer for sustainable tourism planning and policymaking?

1.1. Theoretical Background

This study adopts a multi-layered theoretical approach to analyze Generation Z’s imaginaries of sustainable tourism (

Figure 1). The utopias expressed through written and visual narratives encapsulate not only consumption practices but also spatial, cultural, and symbolic meanings.

At the higher level, the concept of tourism imaginaries provides a theoretical foundation for understanding the fictional, cultural, and symbolic representations of tourism constructed by individuals and groups. Salazar [

11] emphasizes that tourism imaginaries are shaped not only by individual expectations but also by collective images generated through media, education, and cultural transmission. This approach offers a valuable conceptual tool for examining the tourism-related images of the future imagined by younger generations.

At the lower level, the concept of responsible tourism consumption provides a framework for analyzing tourism consumption practices developed with attention to environmental, social, and ethical impacts. This perspective focuses particularly on how sustainability principles are reflected in individual choices and which value systems influence such decisions [

3,

6]. The preferences of younger generations regarding transportation, accommodation, food consumption, and their relationships with the environment are examined within this theoretical framework.

The combined use of these two approaches enables a holistic analysis that encompasses both symbolic representations and practical patterns. In doing so, the study aims to contribute to the literature by moving beyond observable consumption practices and engaging with the mental representations and value systems of young individuals. Compared to the predominantly behavior-oriented studies in the current literature, this focus on imaginaries and representational analysis provides an alternative and critical perspective on sustainable tourism consumption.

In integrating these two frameworks, this study introduces the concept of the imagination consumption bridge, a theoretical connector that explains how symbolic imaginaries are translated into responsible tourism practices (

Figure 1). This bridge conceptualizes the cognitive–normative process through which imagined values, meanings, and representations evolve into concrete behavioral orientations toward sustainability. It operates through three interrelated mechanisms:

Value Internalization: Imaginaries enable individuals to internalize sustainability-oriented values by framing ecological harmony, equity, and social responsibility as desirable moral ideals [

10,

12]. Through this mechanism, imagination functions as an emotional-cognitive channel that embeds sustainability within the self-concept of young tourists.

Normative Translation: Once internalized, these values are collectively negotiated and translated into social norms and ethical expectations that guide responsible tourism behavior [

11,

13]. Tourism imaginaries thus function as cultural scripts that circulate through media and peer communities, shaping what is perceived as “ethical” or “authentic” travel among Generation Z [

14,

15].

Practical Projection: The final mechanism involves the projection of these internalized and shared values into concrete practices such as low-carbon mobility, zero-waste food systems, and community participation where imagination becomes performative [

6,

16]. Here, imaginaries provide templates for how sustainability is enacted in everyday tourism decisions.

Together, these mechanisms illustrate that the imagination–consumption bridge serves as a translation space between the representational (symbolic) layer of tourism imaginaries and the practical (behavioral) layer of responsible tourism consumption. In doing so, it provides a conceptual response to the widely discussed attitude–behavior gap in sustainable tourism [

3,

6] suggesting that imaginaries act as mediators that convert abstract values into embodied and habitualized sustainable practices among Generation Z.

1.1.1. Connecting Tourism Imaginaries to Generation Z’s Context

Generation Z represents the first cohort to come of age amid accelerating climate anxiety, digital hyperconnectivity, and global cultural exchange. Having grown up in a world where environmental degradation and technological innovation coexist, they construct their imaginaries of tourism within a hybrid framework of digital mediation and ecological consciousness. Studies have shown that this generation demonstrates stronger awareness of sustainability challenges and a heightened demand for authenticity and ethical consumption than previous cohorts [

12,

17]. These characteristics position Generation Z as a critical group for understanding how tourism imaginaries are produced, circulated, and enacted within a sustainability-oriented worldview.

Tourism imaginaries are not isolated fantasies; rather, they are cognitive and cultural constructs that reflect how individuals visualize desirable futures and translate collective discourses into spatial visions [

11,

18]. For Generation Z, these imaginaries are increasingly shaped by digital platforms, social media storytelling, and AI-generated visual cultures, where sustainability is both an aesthetic and moral norm [

14,

16]. Exposure to climate activism, influencer-led eco-travel narratives, and global crises such as COVID-19 has expanded the imaginative repertoire through which young people connect ethical values to everyday consumption [

19,

20]. Consequently, Generation Z’s imaginaries of tourism do not simply reproduce escapist ideals but articulate value-driven blueprints for how tourism should function in the future, equitable, low-carbon, and participatory.

The interrelation between imaginaries and consumption thus gains a generational specificity: Generation Z’s sustainability imaginaries serve as normative mediators that link cognitive representations with behavioral intentions. Previous research has suggested that imaginaries guide not only destination perceptions but also moral orientations and lifestyle aspirations [

13,

15]. Within this context, Z consumers reframe tourism as an arena for ethical self-expression turning imagination into a mechanism for social and environmental responsibility. This study therefore conceptualizes Generation Z’s sustainable tourism imaginaries as translational spaces where symbolic visions of the future interact with practical orientations toward responsible tourism consumption.

1.1.2. The Conceptual Foundations of Tourism Imaginaries

Tourism imaginaries refer to the ways in which individuals and communities envision tourism-related places, experiences, and values, as well as the cultural, social, and media-based sources that shape these visions. The concept is inspired by Appadurai’s [

21] notion of “imaginaries,” originally developed to explain global cultural flows, and later adapted to the context of tourism. According to Appadurai [

21], imaginaries function as social frameworks that guide people’s actions and expectations. Within this theoretical perspective, tourism is understood not only as a physical form of mobility but also as a mental, symbolic, and cultural practice.

Salazar [

11], elaborates on the concept of tourism imaginaries, arguing that tourist imaginaries go beyond individual expectations and are instead collective and culturally constructed, largely circulated through media, literature, education, and popular culture. Similarly, Gravari-Barbas and Graburn [

18], highlight the critical role of these imaginaries in shaping how destinations are constructed, how tourist experiences are designed, and how tourism policies are guided. Along the same lines, Kirshenblatt-Gimblett [

22] emphasizes the performative nature of tourism, asserting that tourist sites are not only physically but also representationally produced.

In recent years, this theoretical framework has been applied in diverse contexts such as the representation of heritage sites, destination branding, and media discourses [

23]. However, empirical research focusing specifically on the sustainable tourism imaginaries of younger generations remains limited. Yet Generation Z constitutes a particularly significant social group, having confronted global environmental crises at an early age, grown up with images shaped through digital media, and demonstrated the potential to develop strong value-driven approaches toward the future [

17,

24]. Recent studies have expanded the scope of tourism imaginaries, emphasizing that they are not static representations, but dynamic, multisensory processes shaped by how people perceive, feel, and make sense of places through representational dynamics and cultural reinterpretation. Le, Scott, and Lohmann (2018) [

25] demonstrated that experiential marketing activates imagination through emotional and sensory cues, while Li, Cheng, and Su (2025) [

26] proposed a model of geographical imagination that unfolds through information richness, sensory immersion, and perceptual consistency, illustrating how tourists construct meaning before, during, and after their trips. On a more cultural level, Astudillo and Salazar (2024) [

27] reinterpreted heritage through the notion of heritage imaginaries, arguing that heritage should be understood as a relational and value-laden practice rather than a fixed object within tourism contexts. These studies demonstrate that imagery is an active and value-driven form of meaning-making. However, studies focusing on Generation Z remain limited. In this sense, the question of how tourism imaginaries shape young people’s perceptions of sustainability is both timely and meaningful for tourism studies and consumer research.

This theoretical approach assumes that tourism is not merely a physical activity but also a practice culturally constructed and symbolically reproduced. In this regard, the mental images that individuals particularly younger generations develop about tourism reflect their relationships with nature, society, technology, and the future. Imagined places, forms of travel, and models of interaction offer indirect yet meaningful indicators of how individuals internalize sustainability and attribute meaning to the future. Accordingly, the tourism imaginaries approach provides a suitable theoretical foundation for analyzing mental representations shaped by cultural, environmental, and social values. Particularly in studies working with multi-layered data such as written narratives and visual materials, this approach enables an in-depth examination of the meaning structures embedded in linguistic and visual symbols. In doing so, imaginaries of sustainability can be analyzed not only at the individual level but also in ways that shed light on generational and societal orientations.

1.1.3. Linking Responsibility and Sustainability in Tourism Consumption

Responsible tourism consumption refers to the development of ethical and sustainable choices by individuals during travel, taking into account environmental, social, and cultural impacts. It emphasizes a holistic understanding of consumption that integrates environmentally friendly practices with respect for local communities, cultural preservation, and equitable economic participation [

28]. As such, it provides a critical lens for interpreting demand-side behaviors that underpin sustainable tourism.

In tourism literature, responsible behaviors are often conceptualized around themes such as environmental awareness, ethical concerns, volunteering, and reducing carbon footprints [

29,

30]. However, the extent to which these behaviors align with attitudes and values commonly referred to as the “attitude–behavior gap” remains a recurring challenge in research [

6]. This gap is particularly visible among younger consumers who exhibit strong environmental awareness but whose consumption patterns do not always align with their stated values.

Recent evidence suggests that younger generations, especially Generation Z, demonstrate higher responsiveness to sustainability concerns [

10]. Having grown up amid digital connectivity and global crises, they tend to approach sustainability not merely as policy compliance but as a lifestyle [

17]. Recent research links ethical and agency perspectives to responsible sustainable consumption. Rabbiosi (2025) [

31] conceptualized “travelling imaginative geographies” to highlight how ethical awareness and identity are enacted through mobility and visual narratives, while, from a critical perspective, Capellà Miternique (2025) [

32] introduced the “post-paradise syndrome,” in which tourism imaginaries generate a cycle of hyper-idealization, disappointment (overtourism) reshaping how local societies debate sustainability and belonging. Wan et al. (2025) [

33] demonstrated that combining cultural and ethical messages significantly enhances tourists’ pro-sustainability attitudes and visit intentions. Together, these studies underscore that imaginaries are active, value-laden frameworks of meaning, essential for understanding how Generation Z imagine sustainability in tourism. Yet, empirical understandings of how these values materialize in tourism particularly in transportation, accommodation, food consumption, and destination choices remain limited.

In this study, the responsible tourism consumption framework is employed to analyze the everyday practices, forms of mobility, and interactions with the environment represented in Generation Z’s utopias. By examining young people’s alternative tourism imaginaries through written and visual data, the analysis evaluates which consumption values are prioritized and how sensitivities toward nature and society are articulated. This framework thus serves as both a practical and normative tool for assessing young people’s orientations toward sustainability in tourism. In this respect, it aligns with the Special Issue’s focus on “planning and managing sustainable tourism consumption” and contributes to a deeper understanding of how the next generation’s value systems can inform inclusive and effective sustainability tourism policies.

3. Results

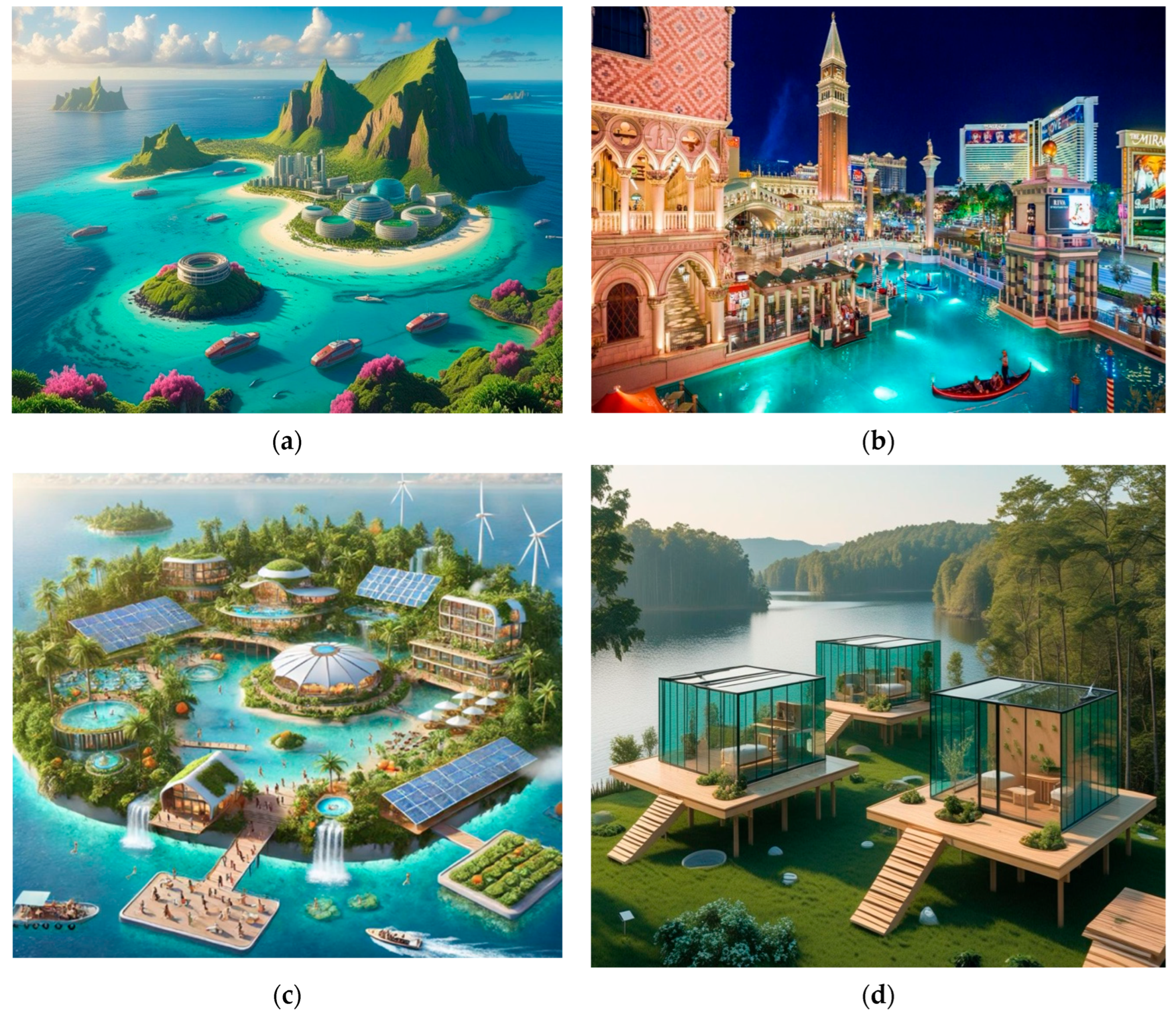

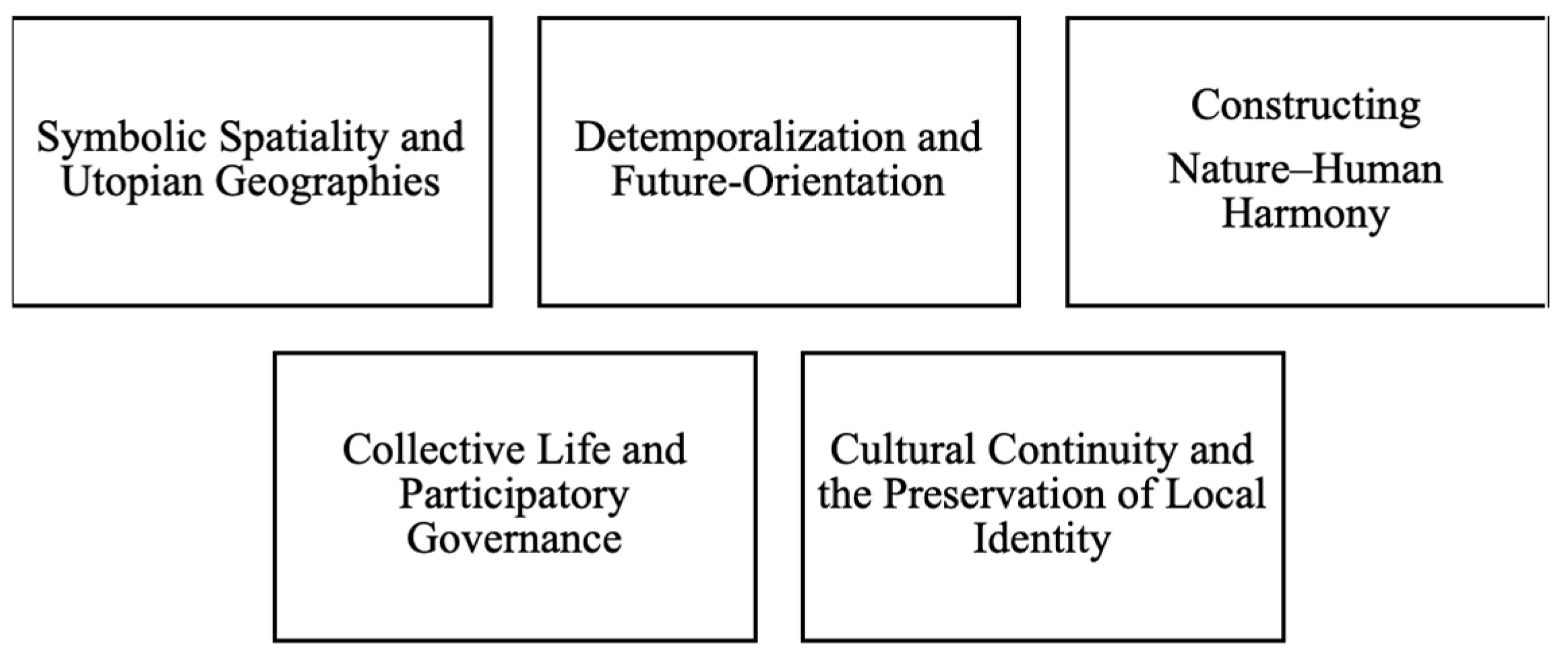

3.1. Tourism Imaginaries

The thematic analysis of the 59 utopia narratives revealed that Generation Z’s imaginaries of sustainable tourism extend beyond physical places, encompassing multi-layered constructions of social order, value systems, environmental integrity, and collective living. These imaginaries were categorized into five overarching themes—see

Figure 3:

Many of the imagined destinations transcend real geographies, offering symbolic worlds reflecting sustainability ideals. About 53% (31) of the narratives described purely fictional places, while 47% (28) idealized existing destinations. Fictional examples such as Minik Cennet (Little Heaven), Franco, Peace Country, Green Future, and Magical Falling Star Utopia evoke themes of nature, solidarity, and peace, often with spiritual undertones. Some were systematically imagined but non-geographic (e.g., “Franco” located between fictional oceans), while others envisioned fantastical settings like “a titanium-coated balloon in the sky.”

Among real-world inspirations, participants frequently referenced destinations with striking landscapes such as the Maldives, Norway, Finland, and Australia. About one-quarter of these (7 cases) were based in Türkiye, reflecting familiarity and accessibility. Some narratives reimagined real cities, such as “Mersin City,” as hubs of cultural and ecological tourism.

Temporal imagination extended beyond the present, ranging from futuristic (49%) to timeless (20%), mythic past (18%), or contemporary (13%) settings. Future-oriented narratives envisioned years like 2033 or 2149, while others referred to ancient or mythological eras, blending history and speculation into sustainability visions. Nature was consistently depicted as an active agent rather than a backdrop, integrated into aesthetics, governance, and tourism. Examples such as Wabi Sabi and Magical Falling Star combined natural landscapes with eco-friendly infrastructure, highlighting nature as both a sacred and co-creative force shaping tourism experiences.

Social systems were reimagined around equality and participation. Leadership roles included ministers and planners (56%), environmental and cultural figures (32%), and technological or scientific leaders (12%), with many narratives assigning decision-making to collective assemblies or AI systems. Gender equality was also salient: women appeared as scientists and guardians of heritage, while men often took technical roles.

Cultural heritage and gastronomy formed another core dimension. About 40% of the utopias emphasized preserving local architecture, cuisine, and religious landmarks. Foodways were central to these imaginaries ranging from zero-waste and plant-based diets to circular food systems and local gastronomy. Real sites such as Kız Kalesi, St. Paul’s Church, and ancient Mesopotamian cities were invoked as symbols of continuity, while utopias like Sun Country and Naharina merged spiritual diversity with sustainable tourism practices.

While participants’ utopian narratives were fictional in form, they were deeply anchored in real-world experiences and sustainability discourses. Many descriptions of imagined destinations echoed contemporary challenges such as over-tourism, ecological degradation, and community displacement, suggesting that participants drew upon their lived realities to construct idealized alternatives. Beyond mirroring current problems, the narratives mobilized recognizable sustainability repertoires low-carbon mobility, circular food systems, community-based governance, and heritage preservation indicating that imaginaries functioned as normative blueprints rather than escapist fantasies.

Importantly, these imaginaries negotiated several tensions that characterize Gen Z’s sustainability outlook: technology vs. nature (e.g., smart infrastructures and AI-enabled monitoring alongside rewilding and slow travel), individual freedom vs. collective responsibility (personal choice framed within community rules and commons management), and access vs. exclusivity (open, inclusive destinations that still safeguard carrying capacity). Such dissonances were not resolved through simple binaries; instead, participants combined elements into hybrid models (e.g., sensor-based visitor caps with participatory budgeting; eco-minimalist architecture augmented by renewable micro-grids). This hybridity shows imaginaries operating as sites of practical problem-solving, where symbolic values are tested against implementable arrangements.

The narratives also revealed clear scalar and temporal orientations. Spatially, participants linked local stewardship (neighborhood food co-ops, watershed councils) with global connectivity (knowledge exchange networks, climate solidarity routes), positioning destinations as nodes in wider socio-ecological systems. Temporally, visions clustered around “near-future” horizons improvements deemed plausible within one or two decades rather than distant utopias, which further grounds the imaginaries in feasible transition pathways. Taken together, this interplay between fictional imagination and real-world reference points demonstrates how tourism imaginaries serve simultaneously as critique of existing systems and as prototypes for more responsible futures, prefiguring the translation from representational ideals to practical consumption and governance choices.

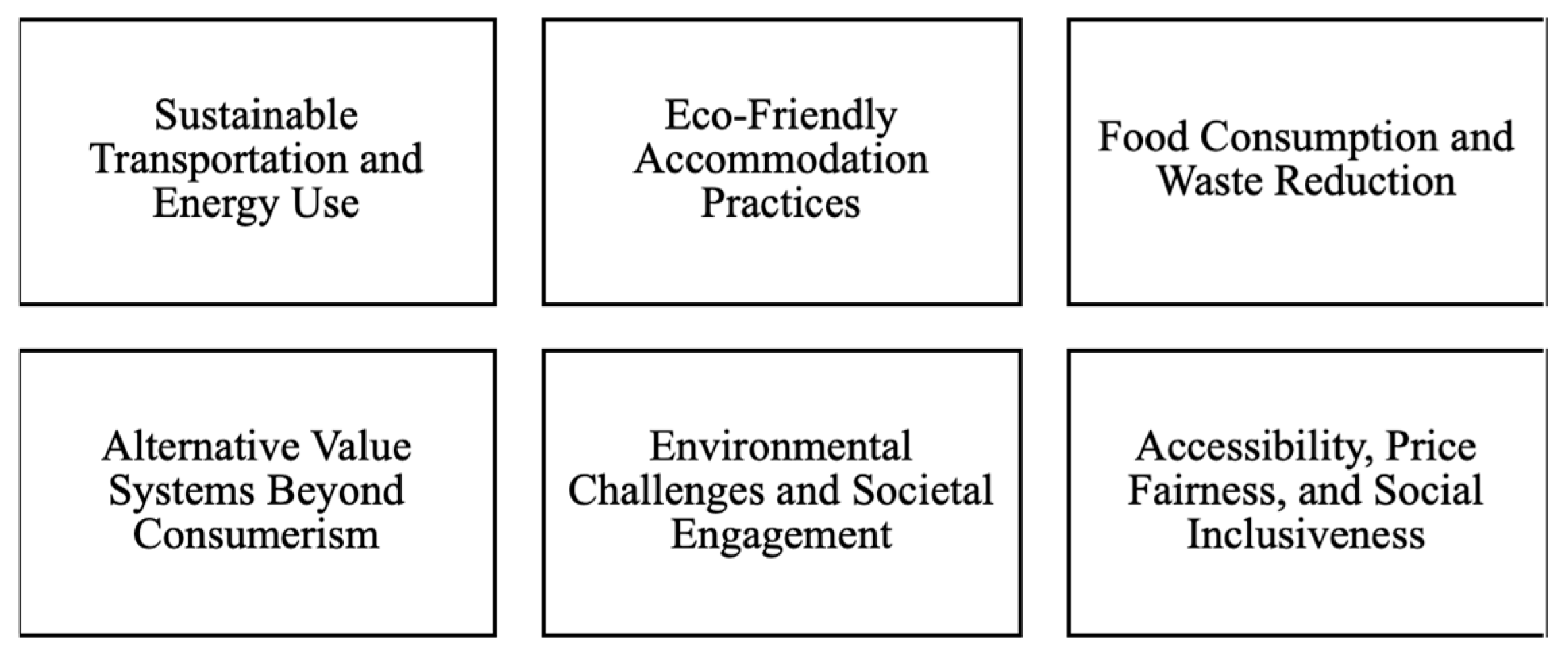

3.2. Responsible Tourism Consumption

The participants’ imaginaries of sustainability were not confined to spatial constructions alone; rather, they also included detailed designs regarding how tourism consumption could become more ethical, environmentally friendly, equitable, and accessible. The analysis identified six main themes—see

Figure 4:

A dominant theme concerned environmentally friendly transport systems. Over half of the utopias (55%) envisioned sustainable mobility through electric vehicles, bicycles, renewable energy, or walking-centered infrastructures. Others imagined solar-powered cars (Ecology City) or hydro-powered metros (Odenja). A smaller portion (25%) retained conventional modes with ecological modifications, and 20% introduced fantastical transport such as dragons, clouds, or teleportation. Overall, these visions reveal Generation Z’s climate consciousness and their preference to transform rather than abandon existing infrastructures. Accommodation was similarly eco-conscious and nature-integrated. About two-thirds (65%) featured renewable energy, recycled materials, and low-carbon practices, including bamboo houses producing their own power (Gwa-Hyeon Village) or underground dwellings as climate adaptation (Kurakya). The rest imagined either conventional luxury hotels or fantastical lodgings like flower-shaped houses or cloud-top skyscrapers.

Food systems reflected strong concerns with waste reduction and local production. More than half (55%) addressed food waste and recycling, while 25% promoted organic and seasonal consumption. Examples included banning chain restaurants (Youngsea), redistributing leftovers to animals (Flora), and converting waste into energy (Sustaintown). Creative proposals such as “hunger machines” or circular composting systems illustrated efforts to close consumption loops. Economic models also challenged conventional tourism. Around 40% combined money with ecological incentives, while 30% imagined entirely free or contribution-based systems. These visions reflect a rethinking of consumption beyond market logic toward ethical exchange and community value.

Collective participation in environmental management appeared in 60% of the narratives. Many utopias emphasized education, community clean-ups, and volunteer initiatives (Odenja, Kaedwen Republic), while others relied on technological fixes such as automated reforestation. This duality illustrates Generation Z’s balance between grassroots engagement and faith in innovation. Finally, accessibility and equity were recurrent priorities. About one-third addressed disadvantaged groups, offering free or subsidized services (Saygılıland, Peace Country), while others emphasized fair and equal pricing (Kaedwen Republic, Green Republic). These imaginaries conceptualize sustainability as a social as well as environmental responsibility. Across these themes, Generation Z’s utopias frame sustainable tourism not merely as a technical adjustment but as a holistic ethical transformation rooted in justice, participation, and collective care.

Under the theme of responsible tourism consumption, the findings indicate that female imaginaries foreground collective well-being and ecological ethics, whereas male imaginaries are more closely aligned with technological rationality and hierarchical structures, reflecting distinct gendered orientations in envisioning sustainable futures (see

Table 1).

3.3. Generation Z’s Imaginaries: Pathways to Sustainable Tourism

The analysis of Generation Z’s imaginaries reveals alternative pathways for embedding sustainability within tourism practices and governance. A significant portion of the visual data depicted living environments deeply intertwined with nature, mountain landscapes, lakesides, forest cabins, and rural life scenes. These visuals indicate that participants did not perceive tourism merely as consumption but as a means of cultivating a symbiotic relationship with nature. Written narratives echoed similar values, emphasizing return to nature, simple living, and authentic experiences, collectively suggesting that sustainable tourism was imagined as an ecologically grounded lifestyle rather than an individual escape.

The second major theme concerned environmental sustainability and ecological alignment. Solar panels, bicycles, electric vehicles, and recycling systems featured prominently across visual data, demonstrating an aspiration for low-impact infrastructures. References to “reducing carbon footprints” and “green mobility” were consistent across both modalities, signaling that Generation Z imagines sustainability as a holistic transformation of everyday life supported by technology and innovation.

A further cluster of images emphasized community life and collective experiences. Depictions of village squares, communal dining, and tourists engaging in joint activities with residents underscored tourism’s imagined role in strengthening social bonds. These findings suggest that Generation Z values collective living, sharing, and solidarity over individualistic consumption. Written statements such as “blending with the local community” and “experiencing local culture” were thus visually reinforced. Tourism was imagined not only as a quest for individual enjoyment but also as an inclusive and participatory process rooted in social interaction.

Another striking finding was the futuristic and utopian scenarios reflected in the visual data. Floating cities, space tourism, renewable-energy-powered megastructures, and alternative living colonies emerged as recurring motifs. These imaginaries demonstrate that participants did not confine sustainable tourism to present conditions but embedded it within visionary future scenarios. Interestingly, Generation Z’s imaginaries combined nostalgic visions of “returning to nature” and rural life with futuristic constructions of technological utopias, illustrating a dual orientation toward both tradition and innovation.

Cultural sustainability also emerged as a significant visual theme. Many depictions featured historic buildings, local festivals, cultural rituals, and intangible heritage. This highlights that Generation Z perceives sustainable tourism not only through ecological dimensions but also within the framework of cultural continuity and heritage preservation. Tourism was envisioned as a vehicle for maintaining local traditions, protecting cultural heritage, and transmitting identity to future generations. The written narratives’ emphasis on “connecting with local cultures” found strong visual resonance in these depictions.

Comparative analysis of visual and textual data revealed a high degree of consistency. Key themes such as return to nature, environmental awareness, community engagement, and cultural preservation were present across both modalities. At the same time, certain futuristic and utopian images that did not explicitly appear in the written accounts revealed latent imaginative dimensions of Generation Z’s visions of tourism. This suggests that their approach to sustainable tourism extends beyond current challenges and incorporates forward-looking, visionary perspectives.

In sum, the visual content analysis indicates that Generation Z’s imaginaries of sustainable tourism are structured around three key axes:

Nature-integrated living practices;

Environmentally and community-oriented responsible tourism consumption;

Futuristic and utopian visions of tourism’s future.

While the overlaps between written and visual data grounded participants’ values, the divergences highlighted the creative and multi-layered dimensions of Generation Z’s perceptions of tourism.

Participants’ understandings of responsible tourism consumption extended beyond individual moral acts and were expressed as interconnected practices that linked everyday choices such as mobility, accommodation, and food with broader systems of governance and ethical reasoning. Their narratives revealed three recurring constellations of behavior. The first involved low-carbon mobility, slow travel, and proximity tourism, in which walking, cycling, and train journeys were perceived as both environmentally sound and emotionally fulfilling. The second constellation centered on eco-accommodation and circular provisioning, with participants imagining small-scale lodgings powered by renewable energy, water reuse systems, and local waste management networks that supported resource efficiency. The third constellation focused on food, fairness, and participation, emphasizing local supply chains, seasonal consumption, transparent pricing, and cooperative ownership models. In each of these constellations, responsibility appeared as a sustained process of decision-making that continued across the different stages of travel planning, mobility, and interaction rather than as an isolated behavioral choice.

Participants also reflected on the practical tensions that complicate responsible consumption, such as reconciling affordability with ethical production, convenience with environmental impact, and inclusivity with ecological limits. Their narratives suggested that responsibility becomes meaningful when these tensions are managed through social design and collective regulation. Many imagined destinations included dynamic pricing to control demand, community-based management boards, or participatory budgeting systems to distribute tourism revenues equitably. This orientation indicates a shift from purely individual responsibility toward shared, structural accountability.

Furthermore, the data showed how participants perceived responsibility as co-produced between travelers, communities, and infrastructures. Individual efforts to behave ethically were seen as effective only when supported by enabling environments such as reliable public transport, visible recycling systems, refill stations, and transparent communication of environmental impact. In this sense, responsible tourism consumption was understood less as a moral identity and more as a socio-material arrangement that makes ethical action possible and habitual.

Finally, participants described trajectories through which sustainability values are transformed into repeated practices. Aspirations for fairness and low impact were translated into visible cues at the destination, such as rail-first travel options, plant-based menus, or price transparency, which encouraged habitual behavioral reinforcement. These patterns illustrate how the imagination–consumption bridge operates in practice: imaginaries provide the normative direction, infrastructures create the material conditions for enactment, and social recognition consolidates these actions into enduring habits.

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore how Generation Z imagines sustainable tourism, and how these imaginaries embody values, norms through written utopian narratives and AI-generated visuals. The findings coalesced around three major axes: (i) nature-integrated living practices, (ii) environmentally and community-oriented sustainability, and (iii) futuristic utopian visions. These results are discussed here considering the theoretical frameworks of tourism imaginaries and responsible tourism consumption, with a focus on their contributions to, and implications for, the existing literature.

The analysis revealed that Generation Z’s imaginaries were dominated by nature-centered, simple, and tranquil living images that closely aligned with textual emphases on “return to nature” and “authentic experience.” This consistency suggests that these imaginaries are not merely aesthetic preferences but are nourished by a value system grounded in ecological symbiosis, community solidarity, and low-carbon lifestyles. Such a finding resonates with prior work emphasizing the link between values, norms, and tourism practices [

3,

6] and highlights the analytic potential of the imagination–value practice nexus in explaining tourist practices.

Drawing on Appadurai’s [

21] notion of imaginaries and Salazar’s [

11] framework of tourism imaginaries, the pastoral scenes and futuristic megastructures found in the visual data reflect how cultural images circulating through media, education, and popular culture mediate young people’s framing of tourism as both a present and future-oriented meaning-making regime. In this sense, Generation Z’s imaginaries go beyond destination “choice” to articulate normative visions of how tourism ought to be organized [

18,

22]. Practices such as free public transport, renewable energy use, or food waste recycling exemplify not only aspirational ideals but also experiences of relative deprivation: participants integrated into their utopias practices that they perceive as absent in their own contexts but existing elsewhere in the world.

The dataset revealed a dual vision: (a) pastoral and locally rooted sustainability (forests, lakes, wooden eco-lodges, local gastronomy, rituals) and (b) techno-utopian futures (floating cities, space colonies, fully renewable infrastructures). This duality aligns with scholarship noting the coexistence of “return-to-nature romanticism” and “technological solutionism” in contemporary tourism imaginaries [

24]. Findings indicate that Generation Z simultaneously legitimizes local identity and cultural continuity [

28,

29] while embracing high-tech innovations to minimize carbon footprints [

7]. Rather than contradicting one another, these imaginaries appear complementary, pointing to a pluralistic vision of tourism’s future.

Nevertheless, this raises an important normative question: could technological utopias render invisible the “volatile carbon costs” of high mobility and energy-intensive futures? Higham et al. [

4] describe this tension as the “flyers’ dilemma,” which highlights a normative contradiction between low-carbon transport imaginaries (bicycles, electric public transit) and techno-futuristic visions of global mobility. Our findings suggest that this tension coexists within Generation Z’s imaginaries, yet their ethical orientation remains clearly expressed through preferences for low-impact practices such as walking, cycling, and local production.

The widely discussed attitude–behavior gap in sustainable tourism [

6] the disjuncture between strong environmental attitudes and inconsistent sustainable practices can also be reframed through these findings. Visual imaginaries may function in two ways to narrow this gap:

By transforming abstract values into concrete practice-based scenarios (e.g., zero-waste kitchens, local sourcing, shared mobility).

By embedding individual responsibilities within collective norms (e.g., communal meals, participatory governance), thereby fostering social reinforcement [

46]. In terms of framing, the aesthetics of metaverse and digital platforms may further gamify or enhance engagement with sustainability for Generation Z. Yet whether visual stimuli produce durable practice change remains an open methodological agenda for future research.

Recurring images of communal dining, village squares, participatory governance, and equity in access/pricing extend responsible tourism consumption into an ethical framework [

28,

29]. These findings suggest that sustainable tourism must be understood not only as technical optimization of supply but also as a matter of distributive justice and inclusivity. The prominence of co-production and participatory governance in these imaginaries demonstrates that Generation Z perceives tourism as a praxis that strengthens social bonds, aligning with UNEP’s [

2] Sustainable Consumption and Production framework, which bridges consumption practices and institutional design.

Methodologically, combining thematic analysis [

33] with visual content analysis [

43] enabled a three-layered reading: (1) symbolic/representational (imaginaries), (2) practical (responsible consumption practices), and (3) normative (justice and inclusivity). The findings suggest that visuals were not only reflective but also constitutive, as young participants treated future practice-based scenarios as design problems. This contributes to tourism research by creating a translation space between visual-based data and value-based theory [

37,

38].

Moreover, the integration of AI-assisted visual generation into the data collection process provided an innovative methodological trajectory, enabling rapid prototyping of young people’s mental models. This approach opens avenues for participatory visualization techniques in practice-oriented design and policy prototyping (e.g., low-carbon tourism scenarios).

The recurring theme of cultural continuity in participants’ utopian imaginaries appears closely tied to Türkiye’s socio-cultural context, where heritage preservation and collective memory occupy a central place in national identity and tourism policy. Generational exposure to heritage-centered education, local traditions, and community-based tourism practices may have implicitly shaped how participants envisioned sustainable futures. Rather than representing a universal pattern of sustainability imagination, this emphasis reflects a culturally situated understanding of continuity, belonging, and intergenerational responsibility. In Türkiye, sustainability is often narrated through the protection of tangible and intangible heritage architecture, cuisine, crafts, and rituals which positions cultural preservation as a moral duty. Consequently, the prominence of cultural continuity in the data should be interpreted not as a generic Gen Z tendency, but as a reflection of localized moral geographies that align sustainability with identity, history, and place attachment. These findings align with recent theoretical discussions that highlight that tourism imaginaries and responsible consumption are deeply intertwined processes that jointly shape how Generation Z envisions and enacts sustainability in tourism [

26,

27,

31,

33].

In conclusion, this study bridges the literature on tourism imaginaries [

11,

21] and responsible tourism consumption [

3,

6] to propose an “imagination consumption bridge.” In this framework:

Imaginaries act as cognitive emotional architectures that translate values into practice templates.

Visual practices (e.g., cycling, local sourcing, zero-waste kitchens) represent practical projections of these architectures.

Community-centered norms (e.g., shared meals, participatory governance) socially reinforce this transformation.

This perspective reconceptualizes the chronic “intention–behavior gap” in sustainable tourism through visual normative mediators, offering directly transferable insights for policy design and communication strategies [

2,

4,

7].

Limitations

This study has certain limitations that warrant consideration. The sample consisted of 59 university students from four universities located in different parts of Türkiye, a group that provides valuable insight into the imaginaries of young people but does not allow claims of broad representativeness. The findings are therefore situated within the specific socio-cultural and political context of Türkiye, where discourses such as heritage preservation and cultural continuity are particularly salient. These contextual dynamics may have shaped participants’ utopian visions in ways that differ from those of Generation Z in other cultural settings. While thematic saturation was achieved, the transferability of the results should be understood as analytical rather than statistical. Moreover, the data were based on self-reported narratives and AI-assisted visualizations rather than lived tourism experiences, which places some boundaries on interpretation. Future research could extend this inquiry through larger and more cross-cultural samples, comparative case studies, and the integration of additional qualitative or participatory methods to further test the robustness and contextual variability of the themes identified here.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Alignment with Research Questions

This study aimed to explore how Generation Z imagines sustainable tourism futures, how these imaginaries reflect responsible tourism consumption values, and how visual and textual narratives interact in constructing sustainability meanings. The following discussion outlines how the key findings address each of these research aims and demonstrates the coherence between the study’s objectives, data, and results.

The first research question sought to understand how Generation Z imagines sustainable tourism futures. The analysis revealed that participants articulated hybrid and contextually grounded utopias that blend ecological awareness, technological innovation, and social justice. Their narratives and visuals presented sustainability not as a distant ideal but as a lived, attainable future in which environmental balance, community well-being, and cultural continuity coexist. These imaginaries functioned as both critique and aspiration questioning the excesses of mass tourism while envisioning fairer and more inclusive models of travel and place-making.

The second question examined how these imaginaries reflect responsible tourism consumption values. The results showed that responsibility was imagined as a collective, systemic process rather than an individual moral act. Participants envisioned sustainable consumption through interconnected practices such as low-carbon mobility, circular food systems, equitable pricing, and universal accessibility. This interpretation supports the conceptual model proposed in the study, the imagination consumption bridge, illustrating how moral ideals expressed in utopian thinking are translated into behavioral norms and governance preferences. Through this lens, consumption becomes a form of ethical and political expression embedded in shared responsibility and community care.

The third research question focused on the interaction between visual and textual data in constructing sustainability themes. The combination of written narratives and AI-assisted visuals produced a high degree of thematic consistency, particularly in the representation of nature-integrated living, cultural continuity, and collective responsibility. Visual data added symbolic and spatial depth to the textual material, revealing layers of meaning related to harmony, regeneration, and coexistence. Rather than duplicating the written content, the visuals expanded it transforming abstract concepts into tangible imagery that strengthened interpretation and theme development.

Together, these findings confirm that the study successfully addressed its research objectives by linking imagination and consumption through a theoretically grounded, methodologically innovative, and empirically coherent framework. The integration of narrative and visual analysis provides new insight into how Generation Z envisions responsible tourism as a transformative socio-cultural process, redefining sustainability as a dynamic interplay between ideals, practices, and representations.

This study set out to explore how members of Generation Z imagine sustainable tourism and how these imaginaries embody values, norms, and responsible consumption practices. By analyzing 59 utopian narratives and AI-generated visuals, the findings reveal that young people articulate sustainability not only through spatial representations but also through ethical, social, and cultural dimensions. Three dominant axes emerged: (i) nature-integrated living practices that highlight harmony with the environment, (ii) community-centered sustainability that emphasizes solidarity, accessibility, and inclusivity, and (iii) futuristic visions that combine technological innovation with utopian ideals. These imaginaries demonstrate that Generation Z perceives tourism as more than a leisure activity; rather, it is envisioned as a transformative practice linked to ecological responsibility, social justice, and cultural continuity.

A key insight is the coexistence of pastoral imaginaries (e.g., eco-lodges, communal living, local gastronomy) and techno-utopian futures (e.g., floating cities, renewable megastructures, space tourism). Instead of treating these orientations as contradictory, Generation Z integrates them as complementary pathways toward a sustainable future. This dual vision reflects both a nostalgia for authenticity and a forward-looking openness to technological innovation. It also reveals a normative orientation where sustainability is not confined to individual choices but is collectively negotiated through shared values and governance structures.

From this perspective, the study advances three major implications:

Theoretical implications: The findings extend the literature on tourism imaginaries [

11,

21] by demonstrating how they intersect with responsible tourism consumption frameworks [

3,

6]. The proposed “imagination–consumption bridge” conceptualizes imaginaries as cognitive–normative architectures that mediate between values, attitudes, and practices. This contributes to reframing the long-debated attitude–behavior gap by showing how imaginaries can transform abstract sustainability values into concrete practice-based scenarios.

5.2. Implications

This study contributes to the growing literature on tourism imaginaries and responsible consumption by conceptualizing the imagination–consumption bridge as a cognitive and normative mechanism that links values to behavior. It demonstrates that Generation Z’s sustainability visions are not merely imaginative expressions but analytical indicators of emerging socio-cultural norms in tourism. By showing how fictional and real-world imaginaries intersect, the study advances theoretical understanding of how young people translate moral ideals into consumption logics.

The findings suggest that inclusive tourism policy design should move beyond abstract goals to actionable strategies. Local governments and tourism boards can establish Youth Sustainability Councils and participatory design labs where young citizens co-create sustainable tourism initiatives. Digital co-creation platforms and AI storytelling competitions could engage Generation Z in envisioning and communicating sustainable destinations. Policies promoting equitable pricing systems, universal accessibility, and living heritage programs can ensure that sustainability is experienced as both a social and environmental right. Moreover, the findings highlight the critical role of policymakers in mediating between imagined ideals and practical realities in tourism [

32].

Finally, collaboration between universities, municipalities, and tourism enterprises can transform youth imaginaries into green entrepreneurship projects, embedding creativity, equity, and innovation into the future of sustainable tourism.

5.3. Future Research

Future research should expand the scope of this inquiry through larger and cross-cultural comparative samples. Investigating Generation Z’s sustainability imaginaries across different socio-economic and policy contexts would provide deeper insight into how cultural values, governance models, and development priorities shape the imagination–consumption relationship. Comparative studies involving participants from countries with varying tourism paradigms such as heritage-based, nature-based, or technology-driven systems could reveal divergent pathways to sustainability thinking among youth. Moreover, longitudinal and mixed-method approaches integrating visual, narrative, and behavioral data would help trace how these imaginaries evolve over time and how they translate into concrete tourism practices and policy orientations.