1. Introduction

As the global population continues to grow, it is estimated that food production will need to increase by approximately 100% by 2050 to meet the projected demand and ensure food security worldwide [

1].

Addressing global water scarcity while ensuring food security requires increasing the productivity of existing farmland, rather than expanding cultivation into natural or biodiversity-rich areas. Achieving this goal depends on optimizing agricultural inputs, particularly irrigation water and fertilizers. However, intensifying their use conflicts with the sustainability objectives of the European Green Deal, especially the Farm to Fork and Biodiversity 2030 strategies, which call for more efficient resource use and reduced environmental impacts in food production [

2]. Moreover, the intensive use of irrigation water threatens the maintenance of ecosystem services and the minimum ecological flow, which is essential to preserve the ecological integrity of aquatic ecosystems [

3].

Food security is also threatened by climate change, which increasingly exposes agricultural production to extreme weather events [

4]. One of the main threats posed by climate change to crop yield is the increase in temperature causing frequent heatwaves. Increasing temperatures lead to reduced photosynthetic activity and biomass accumulation. Another anomaly associated with climate change concerns the altered pattern of precipitation distribution with increased intensity and extreme events [

5]. The unpredictable pattern of precipitation, combined with the deterioration in water quality caused by high temperatures, may leave farmers with water resources that are unsuitable for agricultural use [

6]. Overall, frequent temperature fluctuations, increased evapotranspiration, and reduced soil moisture are expected for the next years [

7].

Irrigated agriculture is globally more productive than rainfed systems [

8], yet it accounts for relevant freshwater withdrawals [

9]. This intensive use makes the sector particularly vulnerable to water scarcity and climate change. In many regions, such vulnerability stems less from the absolute lack of water than from inefficient management, including overexploitation of surface and groundwater resources, insufficient reservoir storage capacity, and inadequate water distribution systems [

10]. Moreover, the irregular pattern of precipitation, along with an increase in heavy rainfall and flooding, is leading to greater waterlogging and soil salinization, posing further threats to irrigation [

11]. Finally, a significant portion of the water used for irrigation is wasted due to system leakages, inadequate irrigation methods, and overwatering [

12].

Given that the limits of freshwater and land use are rapidly being reached, the possibilities for further expansion of irrigation or cropland are extremely limited [

12]. To ensure food security and enhance the resilience of agricultural systems, it is essential to adopt mitigation and adaptation strategies. These include investments in advanced technologies, the implementation of crop specific irrigation scheduling, and the promotion of water saving practices such as reuse and precision irrigation.

In the European context, over 40% of water use is allocated to agriculture, especially in southern countries. According to the most recent Eurostat data (

https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Agri-environmental_indicator_-_irrigation, accessed on 24 June 2025), 15.5 million hectares were equipped for irrigation in Europe, but only 10.2 million hectares were actually irrigated. The majority of irrigated land is concentrated in the Mediterranean region while in central and western Europe, irrigation is mainly used to support crops during occasional summer dryness [

13]. However, projections indicate that by the end of the century, irrigation demand could increase by 30–35% under a high emission Shared Socioeconomic Pathway (SSP) scenario [

14]. Thus, the changing climate conditions are driving traditionally rainfed agricultural areas in Central and Northern Europe to adopt irrigation systems and investments will be necessary to implement irrigation infrastructures [

14,

15].

All EU countries must comply with the Water Framework Directive (WFD), which establishes principles for sustainable water use and cost recovery. In accordance with the WFD, most irrigation systems in the EU operate under a cost-recovery model, whereby farmers pay for water use based on volume withdrawn, area irrigated, or through a flat-rate fee. However, irrigation governance across the EU is not uniform. Individual member states may adopt either a centralized, state level management model, or a decentralized approach, in which responsibilities are delegated to regional or local entities, often through water User Associations, Reclamation Consortia, or Cooperatives [

16]. The latter model is particularly common in Southern European countries, such as Italy, Spain, and France [

17]. In Northern and Central Europe, where irrigation is less widespread, farmers often manage their own systems or rely on permits granted by local authorities [

18]. A bottom-up, decentralized irrigation management approach may foster stronger stakeholder engagement and be more effective in supporting the achievement of WFD goals [

16]. Moreover, these governance frameworks are directly linked to broader sustainability objectives, including the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) numbers 2, 6, and 13, which focus on food security, sustainable water use, and climate action.

In Italy, 202 Reclamation Consortia manage a total area of 17,919,838 hectares, corresponding to 59.47% of the national territorial surface and managing 81% of irrigation water (

https://www.anbi.it, accessed on 25 June 2025). The Reclamation Consortia have historical roots dating back to the medieval and Renaissance periods, when groups of landowners collaborated to implement hydraulic works for land reclamation and flood protection. The modern legal and institutional framework for the Reclamation Consortia dates back to 1933, when they were formally recognized as public economic bodies responsible for managing land reclamation and hydraulic protection within defined territories [

19]. From the post-World War II period onward, the Reclamation Consortia expanded their role to include the design, construction, and management of irrigation infrastructure. This shift was driven by national rural development policies between the 1950s and 1970s, which led to the establishment of widespread irrigation networks [

20]. Despite their central role in water resource management, structural, operational, and territorial weaknesses persist, indicating that the irrigation governance model is still undergoing an evolutionary phase [

21]. Each Reclamation Consortium operates within a territory where there is a hydraulic infrastructure for irrigation, flood protection, and drainage purposes, known as a ‘reclamation district’. All landowners with property located within such a district are considered ‘users’ and are required to pay reclamation and irrigation contributions.

Irrigation water can be distributed via structured or non-structured systems. The structured system is a hierarchical system comprising main canals, secondary distribution networks (open channels or pressurized pipes), and farm level delivery points. In these areas, irrigation is typically managed through rotation schedules, an organized system designed to allocate Consortium managed water to various users according to a predetermined irrigation timetable [

22]. Reclamation Consortia plan irrigation schedules based on water availability and crop requirements. Users are required to comply with these schedules; however, in case of need, the rotation plans can be adjusted or revised depending on changing climatic conditions or water availability. Scheduled rotations offer the advantage of ensuring equitable access among users.

In other areas, there are no structured distribution networks and the Consortium may authorize the use of its dual-purpose canals, which control water flow for drainage (reclamation) and crop water supply (irrigation). In this case, users withdraw water to perform supplemental irrigation. This practice allows farmers to apply additional water to mainly rain fed crops during dry periods, to alleviate soil moisture stress, particularly during critical growth stages. To access this service, for which an annual fee is required, users must submit a formal request to the Consortium. In this case, users can freely withdraw water, but to ensure a more equitable distribution among them, especially during periods of water scarcity, it would be preferable to adopt a rotational management system. The rotation should be differentiated, giving priority first to crops that are more sensitive to water stress, as well as to plots with sandy soils and/or gravelly soils compared to heavy soils.

In the Italian context, supplemental irrigation plays a strategic role in sustaining agricultural production under growing climatic uncertainty. Unlike full irrigation, supplemental irrigation is applied on demand to rainfed crops through the existing drainage irrigation network managed by Reclamation Consortia. This dual-purpose infrastructure represents both an opportunity and a challenge: while it allows flexible water withdrawals, it also requires coordinated management to ensure equitable and efficient distribution among users. Thus, strengthening the governance and optimization of supplemental irrigation is a key step toward enhancing the resilience of Italian agriculture to recurrent droughts. The research questions addressed by this research were: What are the structural differences between Reclamation Consortia? How do different Reclamation Consortia manage supplemental irrigation under contrasting climatic conditions? Can AquaCrop modelling quantify irrigation requirements and efficiency for key crops under varying soil-climate-system combinations?

Thus, the objectives of this study were (i) to evaluate and compare the supplemental irrigation management strategies adopted by three key Reclamation Consortia (Piave, Veneto Orientale, and Acque Risorgive) in the Venetian Plain, (ii) to analyze the variability in governance frameworks, irrigation scheduling criteria, and infrastructure efficiency across the Consortia, and (iii) to model and quantify the seasonal irrigation requirements and efficiency for key crops in different weather conditions. Each Consortium employs distinct methods and water allocation strategies, providing a diverse range of practices for analysis. The research focused on developing a management approach that considers pedoclimatic characteristics and land use while adopting a dynamic rotation system, designed to adapt to variations in water availability caused by the evolving effects of climate change. To achieve this, the AquaCrop model was applied to the 2022 and 2023 irrigation seasons, with 2022 characterized by severe drought. The model assessed whether each Consortium’s water availability could meet the needs of the three most widespread crops in the area: maize, radicchio, and vineyard. The ultimate goal is to guide users’ irrigation activities towards more sustainable water management across the entire region.

Despite extensive research on irrigation or water governance separately, there is a lack of integrated studies linking crop-specific water requirements with the management practices of Reclamation Consortia to guide sustainable and equitable supplemental irrigation. The innovative aspect of this study lies in the combination of AquaCrop-based predictions of irrigation water requirements with a comprehensive assessment of the structures and organizational practices of Reclamation Consortia, based on interviews with their managers. This integrated approach supports sustainable water management by addressing both technical and institutional dimensions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Study Area

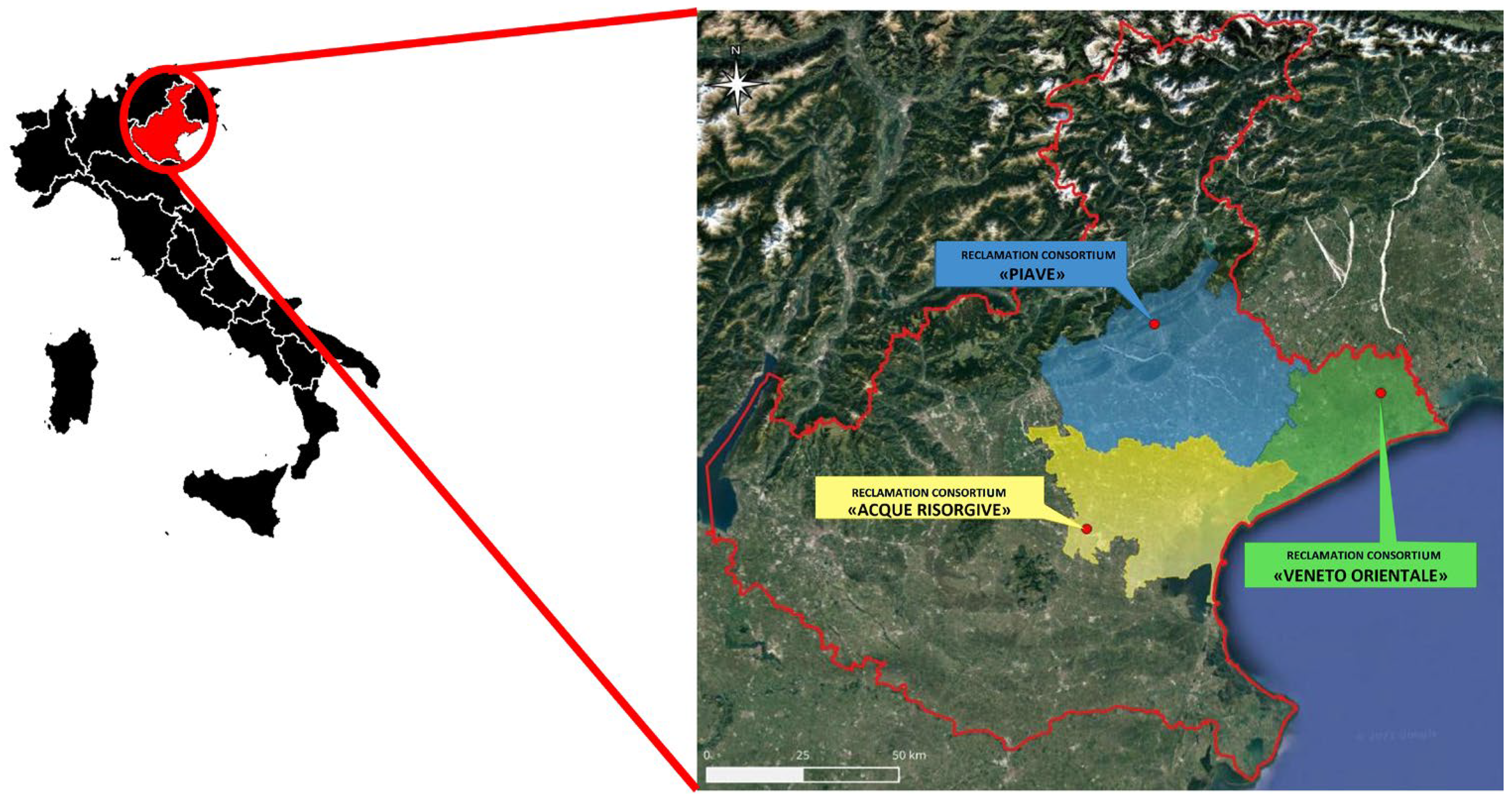

“Piave”, “Veneto Orientale”, and “Acque Risorgive” are the Reclamation Consortia involved in this study and are located in the provinces of Treviso and Venice (

Figure 1).

The area of the three Consortia is located within the Veneto region in northeastern Italy. The region geographical coordinates span from approximately 44°47′34″ N (South) to 46°40′49″ N (North) in latitude, and from 10°37′22″ E (West) to 13°06′03″E (East) in longitude.

The Consortia were selected based on critical criteria, including their geographical proximity (which made it particularly interesting to observe how the practices of one could influence or interact with the others), their organizational structure (which had never been fully compared before), the soil characteristics and predominant crops (which are representative of Veneto region), and the opportunity to initiate potential future inter-Consortium collaboration to enhance the overall resilience of the agricultural system, particularly in terms of irrigation management.

The study area is characterized by a humid subtropical climate, with mean annual temperature of 13–14 °C and annual precipitation ranging from 700 to 1100 mm. These average data were obtained using information from 35 meteorological stations of ARPAV (Regional Agency for Environmental Prevention and Protection of Veneto), uniformly distributed across the study area. The recording period of meteorological parameters varies depending on the variable considered; however, for this analysis, daily average values were used, based on data recorded since 2010. This approach allowed for a multi-year analysis of the meteorological trends within the area of interest. Precipitation is relatively well distributed throughout the year, with moderately dry winters. Spring and autumn are more frequently affected by Atlantic and Mediterranean weather systems, while summer months often bring thunderstorms, hailstorms, and occasionally tornadoes [

23].

Geologically, the Venetian plain was shaped by the progressive accumulation of fluvial sediments from major rivers such as Po, Brenta, Adige, and Piave, leading to the formation of extensive megafans. Minor river systems, fed by pre-Alpine or resurgence springs (e.g., Astico-Bacchiglione, Sile, and Cellina-Livenza) contribute to a dense and complex hydrographic network.

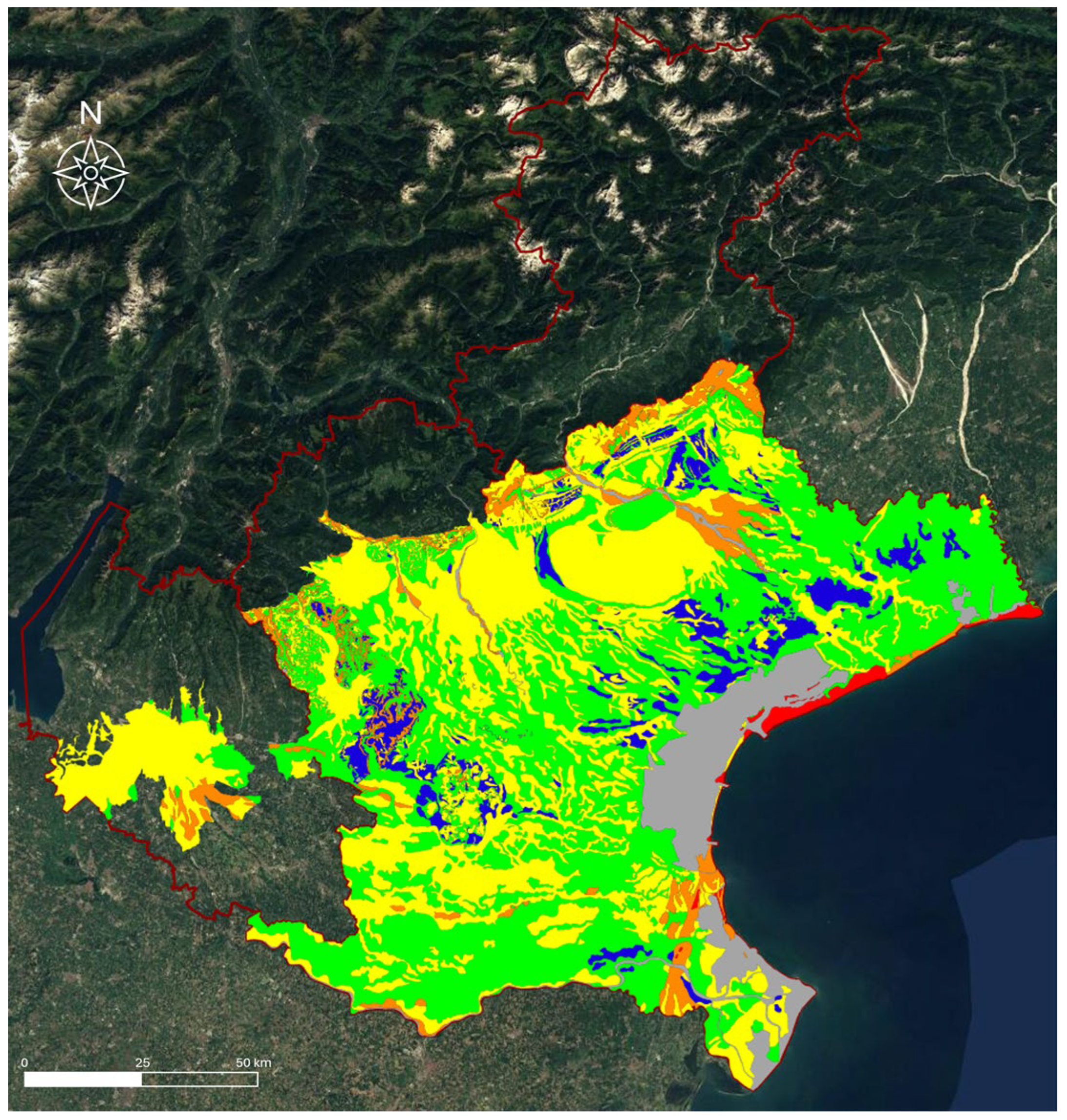

Traditionally, Venetian plain is divided into upper and lower sections with distinct pedological features. The upper plain consists mainly of gravelly and sandy soils with high permeability but low water retention. In contrast, the lower plain features sandy-silty-clayey soils with lower permeability [

24], as shown in

Figure 2.

2.2. Analysis of Supplemental Irrigation Management Methods Adopted by the Consortia

The study was informed by preliminary interviews conducted with three individual managers (one per Consortium) of the Reclamation Consortia. The aim was to analyze the main challenges faced in the management of supplemental irrigation during water scarcity events, assess the effectiveness of existing strategies, and identify areas for improvement. The interviews were structured according to the points listed in the following paragraph. Each interview lasted between 2 and 3 hours and was conducted over three separate days. Whenever an interviewee was unable to provide precise or complete information, the interview was repeated, allowing time to gather the missing data. Any additional information, for practical reasons, was collected through the submission of digital materials.

While Consortia are primarily tasked with ensuring adequate water delivery for agricultural cultivation, broader objectives such as the protection and enhancement of ecosystem services must also be considered [

25].

Based on these premises, the survey focused on three main aspects: (i) the strategies and protocols adopted by the Consortia during periods of water scarcity, with particular emphasis on water rotation practices; (ii) the administrative procedures for requesting and using water; and (iii) the planning of infrastructures aimed at improving efficiency and protecting the territory against potential water shortages.

From an administrative perspective, the study examined how irrigation requests from farmers are handled, the regulatory framework governing irrigation water use, and how irrigation fees are structured and managed. In addition, the Consortia were asked to provide detailed information on territorial jurisdiction, land use, cultivated crops, and irrigation methods employed.

Among the infrastructures considered, retention basins play a vital role in supporting irrigation systems. They contribute not only to water storage and supply but also to flood control, sediment and pollutant retention, and overall environmental protection, thus representing key elements within the framework of Best Management Practices (BMPs) [

26].

Based on the information provided by the managers of the three Consortia, the adopted measures were categorized according to their implementation and management complexity:

supplemental irrigation management measures by Reclamation Consortia,

governance practices, regulation and monitoring,

availability of regulation and storage reservoirs.

Each measure was assigned a score ranging from 1 to 5.

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3 present the values along with a detailed description of each categorization.

Table 1 details the categorization of supplemental irrigation management measures by Reclamation Consortia,

Table 2 summarizes the categorization of governance practices, regulation and monitoring and

Table 3 outlines the categorization of availability of regulation and storage reservoirs.

The results obtained from the various interviews were compared with the water volumes estimated by the AquaCrop model. The selected crops, irrigation systems, and soil types were considered to be the most prevalent, and therefore representative, across all three Consortia. In particular, the aim was to assess whether Consortia would have been able to meet the hypothetical water demands of the main crops across the different areas and growing seasons, based on their actual organizational structure. This comparison allowed us to identify potential strengths and weaknesses of the various Consortia structures.

2.3. AquaCrop Model

AquaCrop is a simulation model developed by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) to estimate crop productivity under varying water availability conditions. AquaCrop is designed to evaluate the relationship between water inputs and yield outcomes, partcularly in water limited environments [

27]. The model requires multiple input parameters, including weather data, crop and soil characteristics, and management practices that define the environment in which the crop will develop. Outputs generated by AquaCrop include projected crop yield, water use efficiency (WUE), and total water consumption.

AquaCrop is highly sensitive to climatic, irrigation, and soil parameters. It is also strongly influenced by crop-specific parameters, such as sowing or transplanting density and canopy cover, which in turn affect leaf growth, water consumption, and final yield. To manage uncertainties, the model provides predefined ranges for certain parameters, such as crop density, helping to avoid major input errors. These features allow AquaCrop to address uncertainties arising from climate variability, input errors, and inherent sensitivity to crop and soil characteristics, ensuring more reliable simulations under varying conditions.

AquaCrop can be calibrated for a wide variety of crops, characteristics of local irrigation systems, climatic conditions, and agricultural management systems. It assists farmers in making informed decisions about irrigation strategies [

28], water saving techniques, and forecasting agricultural productivity under changing environmental conditions. An advanced feature of AquaCrop allows users to simulate the effects of different agronomic practices, such as mulching or modifications in sowing dates. Such information helps identify the optimal timing and amount of irrigation needed to maximize yield while minimizing water waste.

Beyond operational planning, AquaCrop is widely used in scientific research to investigate the interactions among water, soil, climate, and crop productivity, serving as foundation for developing sustainable agricultural strategies. However, as with any simulation tools, AquaCrop operates on simplified assumptions and may not fully represent the complexity of field conditions. The model has some limitations including reduced accuracy in estimating evapotranspiration and WUE in certain contexts, and a primary focus on annual herbaceous crops [

29]. These constraints were particularly relevant in our study which involved the simulation of perennial crops, such as grapevine (

Vitis vinifera L.). Grapevine is an extremely important crop for our region because it is very widely cultivated and its production plays a vital role in international trade. In Veneto region alone, the vineyard area in production reached approximately 94,708 hectares in 2022, with a grape harvest of about 15 million quintals and a wine production of around 11.9 million hectolitres. Moreover, Veneto wine export value in 2022 was close to € 2.84 billion, accounting for about 36% of Italian total wine export in that year.

2.3.1. Model Calibration

The calibration process involved adjusting parameters related to irrigation methods and soil characteristics, using the AquaCrop model (Version 7.1). Specifically, the following variables were calibrated: meteorological data, crop type, irrigation method, soil fertility level, and the presence of a shallow groundwater table. Soils were selected based on the characteristics indicated in the regional soil map of the Veneto Region, aiming to identify two soil types with opposite properties in terms of water retention and rooting depth, and present in all three irrigation Consortia. The selected irrigation methods reflected those most commonly used in the three Consortia, with their characteristics (such as irrigation efficiency and degree of ground cover). Regarding soil fertility and the presence of a shallow water table, average values were chosen to minimize their influence on simulation. The most complex aspect was the calibration of different crops: apart from maize, whose parameters were already available in the model, radicchio and grapevine had to be created from scratch. For these crops, particular attention was given to parameters such as leaf coverage, rooting depth, average water consumption, and final yield. These values were cross-checked to produce crop profiles as realistic as possible in relation to the production levels observed in the area of interest. The adjustments aimed to ensure consistency between modeled and expected responses under the local agroclimatic and irrigation conditions.

Statistical analyses were conducted to evaluate the significance of differences and the influence of selected factors on irrigation volumes. A Welch Two Sample t-test was employed to compare annual mean irrigation volumes, adopting a 95% confidence level (α = 0.05) to assess statistical significance. Furthermore, a multiple linear regression model (lm) was fitted to quantify the effects of irrigation system, soil type, crop variety, and year on irrigation volumes. The validity of model assumptions was verified prior to interpretation, and the statistical significance of the explanatory variables was determined according to conventional probability thresholds (p < 0.1, p < 0.05, p < 0.01, p < 0.001). All computations and analyses were performed using R software (version 2024.09.0+375).

2.3.2. Weather Data Collection

AquaCrop integrates weather data by calibrating the model using observed soil parameters and weather datasets, adjusting crop parameters under optimal water availability, and validating the model with independent datasets from different locations or experimental series [

30].

In this study, weather data were sourced from six monitoring stations that are part of the telemetry network managed by ARPAV (Regional Agency for Environmental Prevention and Protection of Veneto). The stations were carefully selected within the area managed by the three Reclamation Consortia, with two stations representing each Consortium’s territory. To ensure consistency, the selected stations were located in areas that were as homogeneous as possible in terms of soil structure, climate conditions, rainfall patterns, and crop types. The meteorological parameters considered were the daily minimum, mean, and maximum temperature, as well as daily rainfall. The reference period extended from 1 January to 31 December for both simulation years (2022 and 2023). The individual parameters collected from each weather station were averaged to obtain a single annual value (2022 and 2023) for minimum, mean, and maximum temperature, and for rainfall.

The recorded data were used to calculate crop evapotranspiration (

ETc), a key component of the soil–water balance.

ETc was derived in two steps. First, the reference evapotranspiration (

ET0) was calculated using the Hargreaves-Samani equation, adapted to Venetian plain by Berti et al. [

31] (Equation (1)).

where

R0 is the global radiation based on latitude, obtained from tabulated values;

Tmean, Tmax, Tmin are daily average, maximum, and minimum air temperatures (°C).

Once the

ET0 values, calculated based on the previously obtained meteorological data, were entered into the model, AquaCrop automatically computed the Crop evapotranspiration (

ETc) values according to the selected crop, following Equation (2) below:

where

kc is the crop coefficient based on the phenological stage of the crop, obtained from tabulated values [

32].

2.3.3. Soil Data

Two distinct soil types were selected for the simulations to account for contrasting hydrological behaviors. One was a loamy soil and the other a well-drained soil with high gravel content. Both soil types are present in all the areas considered in the simulations and represent the extremes in terms of soil water retention capacity. Detailed information on the pedological properties of the selected soils, based on values provided by the AquaCrop model, is summarized in

Table 4.

2.3.4. Irrigation Methods and Crops

Three irrigation methods, reflecting the systems in use across the participating Reclamation Consortia, were considered in the simulations: subsurface irrigation, drip irrigation, sprinkler irrigation. In AquaCrop, subsurface irrigation is interpreted as subsurface drip irrigation. This system involves buried drip lines near the root zone to reduce surface evaporation and enhance water delivery where it is most needed [

33]. The water requirement for each irrigation system is automatically calculated by the AquaCrop model, taking into account the parameters reported in

Table 5 for the different irrigation methods, as well as soil characteristics and climatic conditions. In addition, water consumption is estimated based on the target average yield expected for each crop.

The main technical specifications used for each irrigation method in the simulation are reported in

Table 5.

The crops selected for this simulation were grapevine, maize, and transplanted radicchio. Despite differing water requirements and phenological cycles, all the crops are widely cultivated within the areas managed by the land Reclamation Consortia involved in the study.

While AquaCrop database includes a variety of herbaceous crops, this study required custom crop files for grapevine and radicchio. These files were created using average water consumption and yield data. For radicchio, the main parameters included root depth, transplant density, leaf area development, canopy cover, and the typical transplanting and harvesting periods of the areas managed by the participating Reclamation Consortia. As regards grapevine, as AquaCrop does not simulate perennial crops, the transplanting date was assumed to coincide with the onset of vegetative growth. A minimum root depth relative to its maximum potential was considered, while other parameters, such as vegetative growth rate, canopy cover, and harvest timing, were set according to reference values representative of the Consortia production areas. Compared to maize, these parameters introduced some degree of uncertainty; however, they were carefully evaluated and adjusted until the simulated water consumption and yields were consistent with the values observed in real field conditions. For maize, the default crop parameters provided by AquaCrop were used without modification.

Grapevine (

Vitis vinifera L.), although traditionally cultivated under rainfed conditions, exhibits stage specific water requirements [

34]. Severe water stress during summer can significantly impair fruit development and reduce both yield and quality [

35]. Water deficits can affect grapevine physiology, delay ripening, and alter organoleptic properties, especially under increasing temperatures and declining rainfall during the vegetative period [

36]. In Veneto region, average annual water requirements for grapevine are estimated at approximately 300 mm, with the highest demand during the dry summer months [

37]. Local vineyards employ various irrigation systems, ranging from traditional sprinklers to more efficient microirrigation methods, which offer agronomic and operational benefits. For grapevine, an average yield value of 14 t/ha was considered, without accounting for possible varietal differences.

Maize (

Zea mays L.) exhibits high water requirements, particularly during germination and early vegetative growth stages [

38]. In Veneto the total water demand typically ranges between 600 and 800 mm per growing cycle, with critical periods including flowering and kernel development. Water stress during critical growth stages, especially during germination, flowering, and ear formation can lead to considerable yield reductions [

39]. Sprinkler and drip irrigation are the most commonly used methods in the region, while traditional surface irrigation (e.g., furrow systems) is now rarely adopted. For maize, an average yield value of 15 t/ha was considered.

Radicchio (

Cichorium intybus L., group

Rubifolium), is a variety of chicory, also known as “Italian chicory” grown in Venetian plain. It requires precise irrigation management from transplanting, usually in early August, until full development of the heads in early autumn. Irrigation is typically performed with sprinkler irrigation systems [

40], watering only when a deficit is detected and applying at least 20 mm per irrigation. However, research has shown that for more efficient water use and higher crop production it is advisable to irrigate more frequently with smaller volumes [

41]. In most cases, low pressure sprinkler systems (which simulate gentle rainfall)are the most sustainable solution for this crop [

41]. For radicchio, an average yield of 20–22 t/ha was considered, based on the Treviso radicchio variety, a local cultivar from the study area [

41,

42].

3. Results

3.1. How Consortia Manage Supplemental Irrigation

Based on the characterization of the different topics addressed in the questionnaire and across the various Consortia, the results obtained from the survey are summarized in

Table 6. Scores on a 1–5 scale were assigned through qualitative evaluation and multiple independent scoring.

The three Reclamation Consortia manage water scarcity in different ways, while sharing the common goal of ensuring adequate irrigation supply. The Piave Consortium manages supplemental irrigation through individual user authorizations, allowing a flexible withdrawal period from June to mid-July. This is followed by a scheduled rotation system with prebooked time slots, generally from 15 July to the end of August, which can be adjusted based on water availability.

The Veneto Orientale Reclamation Consortium continues to carry out routine management and maintenance activities even during periods of water scarcity. In some areas, it uses pumping stations located downstream of the network to reintroduce higher-quality water into upstream canals. This operation has been made possible thanks to a monitoring system implemented in 2022. As water scarcity is partly influenced by upstream water resource management, in the event of severe drought, withdrawals are suspended. Currently, the Veneto Orientale Consortium does not rely on formal irrigation regulation or detailed monitoring of irrigation demand, although future implementation is planned.

Finally, the Acque Risorgive Reclamation Consortium adopts a stricter rotation system. This Consortium has developed a ‘Drought Management Plan’ with four alert levels (normal, pre-alert, alert, and emergency), each determining specific irrigation restrictions. In the emergency phase, irrigation is prohibited.

As regards irrigation scheduling criteria, the rotation methods during drought conditions are similar across the three Consortia. The Piave Consortium manages rotations using software that controls water availability and canal flow rates, optimizing withdrawals zone by zone according to supply. The Veneto Orientale Consortium applies rotation only in emergency situations based on criteria depending on multiple factors, including water availability, seasonal conditions, water quality, and crop type, with priority given to early harvest and perennial crops. In 2024, a demo version of IRRIBOOK, a platform for irrigation scheduling, was developed. The Consortium’s goal for the coming years is to enable farmers to promptly report the irrigation needs of their fields. The Acque Risorgive Consortium adopts a rotation system triggered by climatic alert levels. In cases of moderate to severe water crisis, irrigation is reduced and managed through continuous monitoring. Thus, none of the Consortia showed an optimized irrigation scheduling management but they are building up an efficient system.

Moving to the second objective of the investigation, the three Land Reclamation Consortia apply similar administrative procedures and principles for calculating irrigation fees, which justifies the medium score assigned to all of them in this category. Despite differences in the calculation methods, flat rate in the Consortium Piave, benefit-based formulas in the Consortia Veneto Orientale and Acque Risorgive, all require users to submit land and technical details, and ensure compliance through structured processes.

Differences are more evident in irrigation request management. The Consortium Piave uses a traditional but functional system with paper or online forms and clear supervision. The Consortium Veneto Orientale has simplified the request process and is implementing the IRRIBOOK platform to improve efficiency and transparency. The Consortium Acque Risorgive, by contrast, still relies on a complex, document-heavy procedure with no plans for short-term updates.

The third topic of the investigation on the managing efficiency of the three Consortia related to storage basins. Our findings show that territorial differences among Consortia lead to a highly variable approach to water resource management. However, at present, none of the three Consortia demonstrates effective performance in the management of storage basins. The Consortium Piave has flood control or expansion basins for hydraulic defense, but not for water storage purposes. The Consortium Veneto Orientale, constrained by local geology, does not possess storage basins but adopts alternative solutions, such as the installation of barriers on canals for minimal and temporary water retention. It also relies on coastal infrastructure to mitigate saltwater intrusion. Finally, the Consortium Acque Risorgive is not equipped with storage basins, but it is actively developing new basins to enhance water management and address the increasing challenges posed by water scarcity.

3.2. AquaCrop Model Results

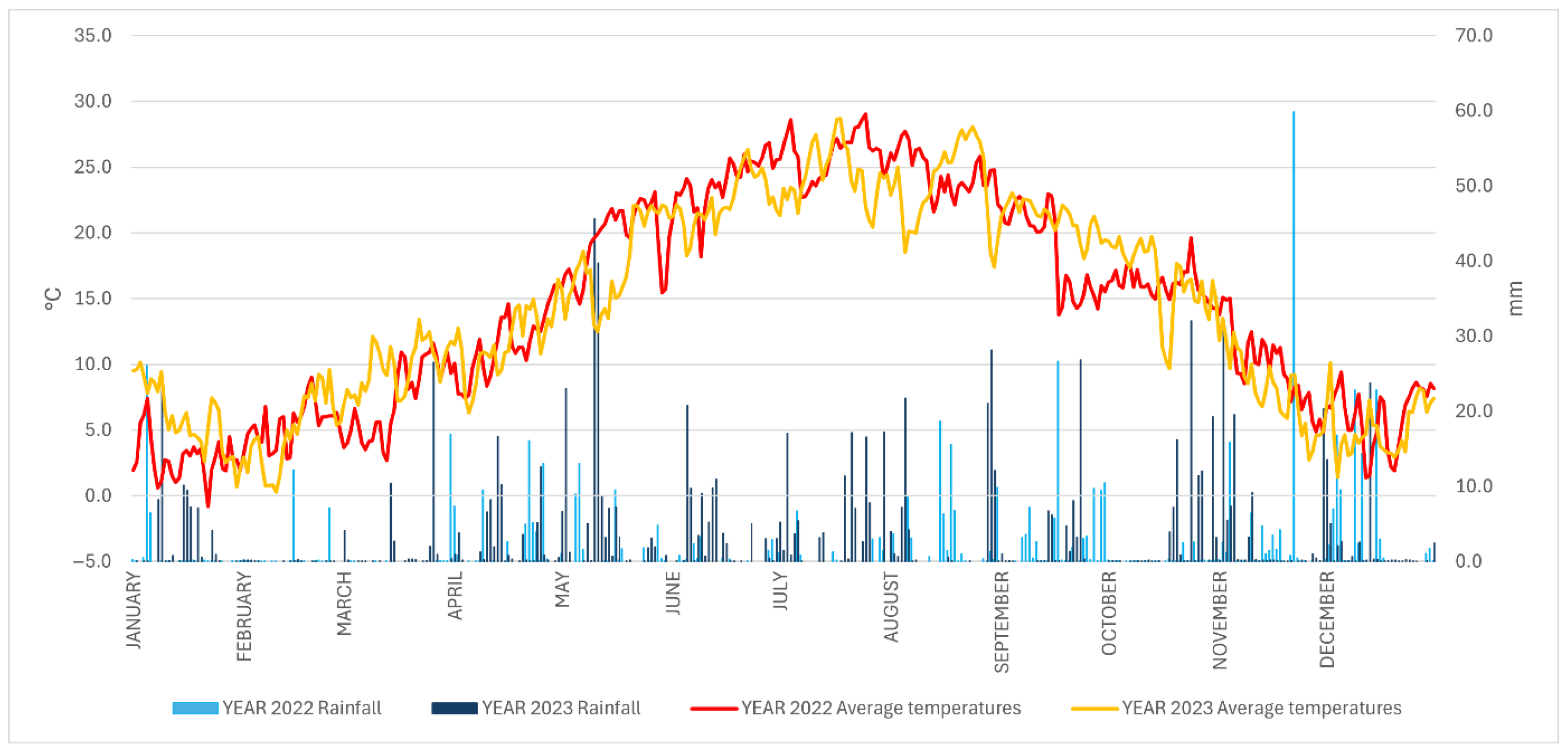

The simulation carried out with the AquaCrop model examined two different years, whose weather patterns are shown in

Figure 3. Meteorological data were obtained from the ARPAV weather stations listed in

Section 2.3.2. The differences between the two years reflect variations in climatic conditions, based on empirical observations. The weather conditions had a strong influence on the water requirements of the crops, and the differences in terms of irrigation volumes and number of irrigation events can be observed in

Table 7.

Thanks to the simulations performed with the AquaCrop model, it was possible to compare the estimated irrigation volumes and the number of irrigation events for each year, crop type, soil type, and irrigation system with the actual water volumes available to the Consortia. This comparison allowed the assessment of whether the existing irrigation network and water resources were sufficient to meet the estimated crop water requirements. The results are summarized in

Table 8.

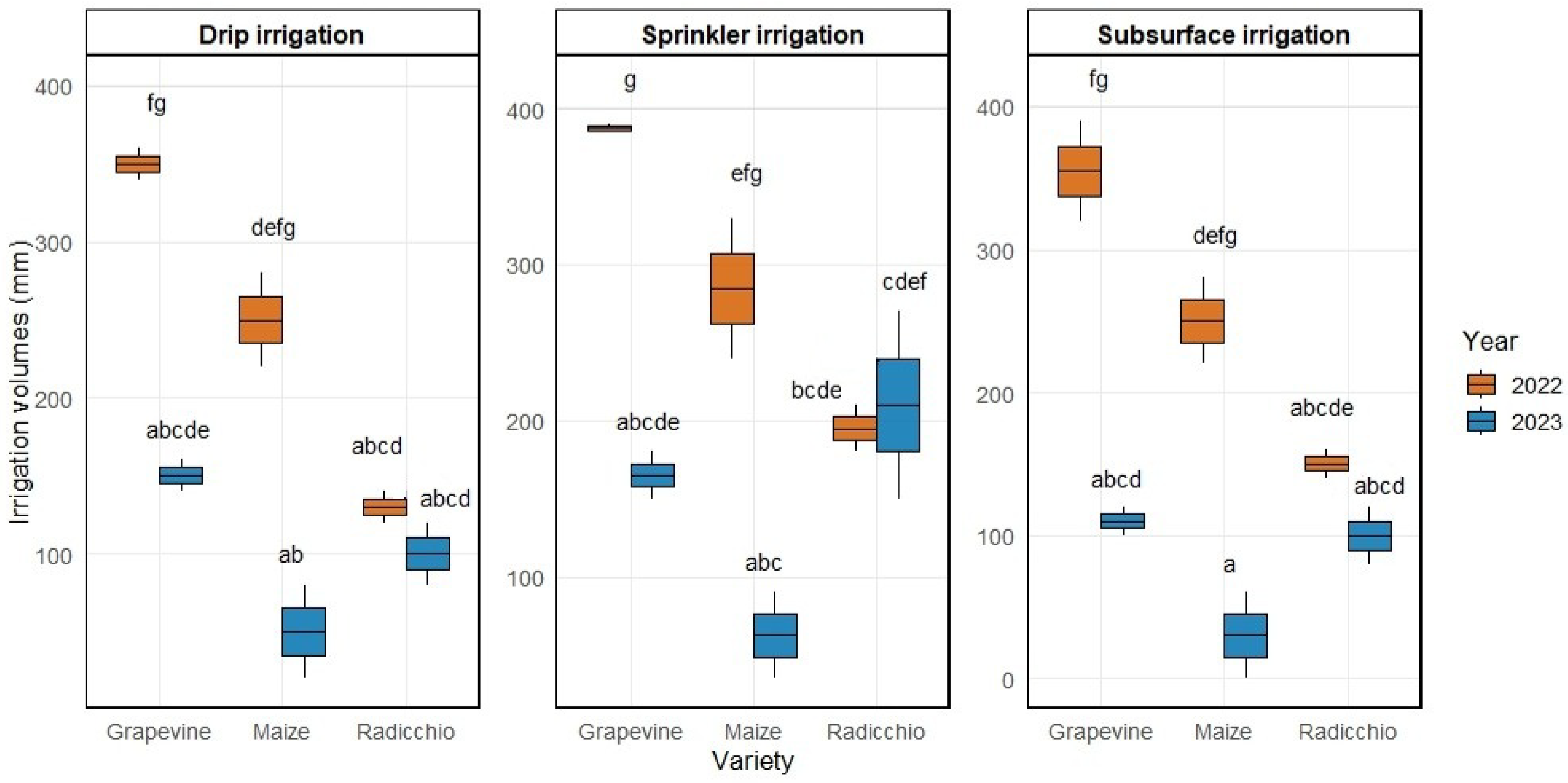

A clear pattern emerged: in 2022, irrigation volumes and events were consistently higher across all crops and systems, reflecting severe drought and high temperatures. In particular, precipitation in 2022 was approximately 70% lower than in 2023 (108.7 mm compared to 310 mm during June, July, and August). Moreover, maximum temperatures in 2022 were 1.6 °C higher during the same period and persisted for a longer number of consecutive days, further exacerbating the overall drought conditions.

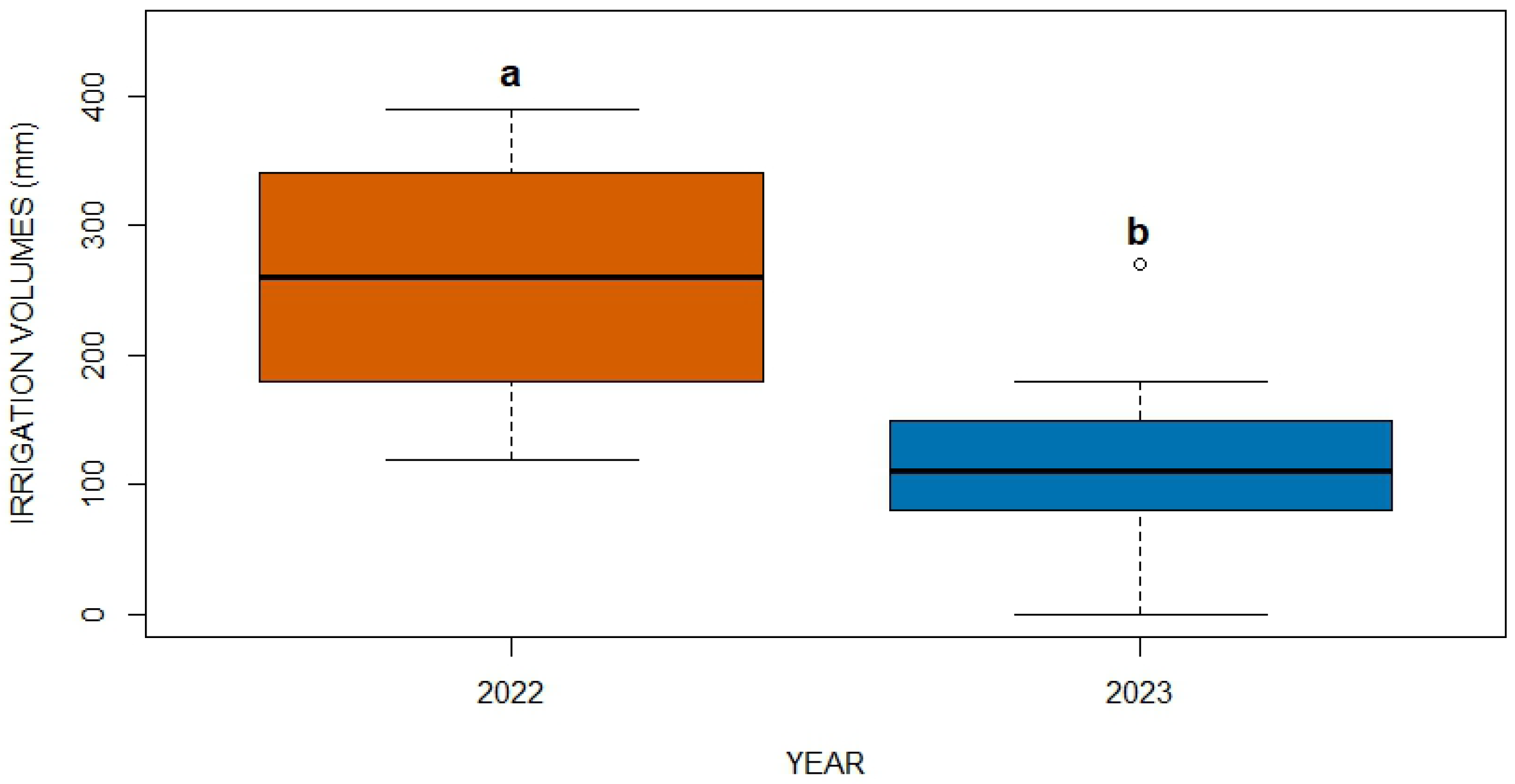

A Welch Two Sample

t-test was applied to assess interannual differences in mean total irrigation volumes. Mean values were 261.39 mm in 2022 and 108.61 mm in 2023, representing an overall reduction of approximately 58.5%, as shown in

Figure 4. The difference between years was statistically significant (

p < 0.001). This analysis considered only annual mean irrigation volumes, without distinguishing among crop types, irrigation systems, or soil classes.

Maize was very sensitive crop to water stress: in well drained soils under sprinkler irrigation, volumes reached 330 mm with 11 events in 2022, compared to 90 mm and 3 events in 2023, with a difference of almost 73% more irrigation water. In 2023, subirrigation was almost unused for maize on loamy soils, indicating adequate rainfall or limited suitability of this method under milder conditions.

Radicchio, a shallow rooted leafy crop, had moderate irrigation volumes but remained sensitive to soil type and irrigation methods. Sprinkler irrigation on well drained soils peaked at 270 mm and 9 events in 2023, possibly due to its late summer planting, which coincided with a gradual increase in rainfall.

Grapevine, a deep-rooted perennial crop, consistently required the highest irrigation volumes, especially in 2022. For example, sprinkler irrigation on loamy soils reached 390 mm and 13 events, while subirrigation reached 320 mm and 16 events. In 2023, subirrigation for grapevines on loamy soils dropped from 16 events to none, reflecting improved water availability or changes in irrigation strategy.

These descriptive patterns were supported by a multiple linear regression analysis considering the effects of irrigation system, soil type, crop variety, and year on total irrigation volumes (

Figure 5). The model explained a substantial portion of the observed variability (

p < 0.001). Year was the strongest predictor, confirming significant interannual differences. Crop variety also had a pronounced effect: maize and radicchio required significantly less irrigation than grapevine, with estimated coefficients of –98.3 mm for maize and –105.4 mm for radicchio relative to grapevine. Well-drained soils were associated with higher irrigation volumes (+45 mm), and sprinkler irrigation showed a marginal positive effect, with volumes estimated to be approximately + 45.8 mm higher than drip irrigation, although this effect was only marginally significant (

p = 0.058). Subirrigation was not statistically significant, consistent with its limited application in certain years and crops. Overall, irrigation demand reflected the combined influence of crop-specific water requirements, soil characteristics, irrigation method, and annual climatic conditions.

4. Discussion

4.1. Contextualizing Supplemental Irrigation Efficiency Within Mediterranean Reclamation Consortia

The investigation conducted for this study aimed to analyze the persistent constraints associated with supplemental irrigation management by Consortia, especially in light of a changing climate that affects crops underpinning the local economy.

The initial focus of the investigation was to analyze the measures and practices adopted for managing supplemental irrigation (

Table 1 and

Table 6). Attention was paid not only to water scarcity management strategies, but also to the criteria used for irrigation scheduling. In other words, the analysis went beyond the current management strategies, taking a step back to examine the baseline organizational structure prior to the onset of water stress.

Research on irrigation governance and the role of Reclamation Consortia in Mediterranean agriculture has increasingly focused on the effectiveness of water management practices. However, existing studies have typically addressed either the organizational or the technical dimensions of irrigation management, with limited interest in assessing the efficiency of the measures implemented to manage supplemental irrigation under variable climatic conditions. The irrigation governance trends and challenges across Mediterranean countries were analyzed by Molle [

43], emphasizing the historical evolution of Reclamation Consortia in Italy and their analogues, such as Comunidades de Regantes in Spain. The work stressed institutional fragmentation and the need for integration between basin authorities and local management bodies, providing a regional policy framework. However, it did not explore the operational efficiency of Consortia or their potential for adaptive irrigation planning under variable water availability. Lamaddalena et al. [

43] provided a foundational analysis of the Reclamation Consortium della Capitanata in Southern Italy. They illustrated how collective management and advanced distribution systems can support equitable water allocation. However, their work did not quantify the performance of supplemental irrigation strategies or the water savings achieved. Isselhorst et al. [

44] offered a comparative view by examining irrigation communities in Andalusia, Spain. Their analysis highlighted the long-term institutional persistence and adaptability of collective irrigation management systems under Mediterranean conditions. The findings of their work illustrate the sociocultural resilience of local governance models; however, the study did not include a quantitative assessment of irrigation performance or predictive modelling of water needs.

In contrast to these previous works, our study introduced an innovative framework by combining AquaCrop-based modelling of irrigation water requirements with a systematic evaluation of the structures and operational practices of Reclamation Consortia. This integrated approach aimed at identifying both the quantitative needs for supplemental irrigation and the institutional capacities and constraints influencing their implementation and might serve as a reference to determine water-use efficiency in Mediterranean irrigated agriculture.

Table 6 displays that the Piave Consortium showed the best performance, supported by a fully developed and structured system. Located in the northern part of the study area, this Consortium benefits from its favorable geographical position. Specifically, Piave can draw water further upstream, taking advantage of greater water availability, especially during the drier months, when the gravelly nature of the terrain results in significantly reduced flow rates. Moreover, the Consortium territory is subdivided into supplemental irrigation districts, reflecting a reasonably well-defined organization into management subzones. The irrigation infrastructure operates mainly in two ways: surface (gravity) irrigation and pressurized systems. Reasonably, diversifying water supplies mitigates risks associated with climate change [

45]. The well-structured organization can be attributed to a long-standing history of irrigation management within its jurisdiction and precedes the establishment of the neighboring Consortia.

4.2. Contribution of the Work to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

The management of irrigation practices raises concerns about the long-term sustainability of water resources, potentially compromising their availability for other uses and triggering far reaching social, environmental, and economic consequences [

45]. As highlighted in a recent study [

46], a well-structured management system enhances the economic sustainability of Reclamation Consortia by reducing labor costs and water use. This, in turn, contributes to greater environmental sustainability by allowing the expansion of irrigated areas. Moreover, the network structure also contributes to environmental sustainability. It ensures continuous monitoring of water withdrawals, allowing for the maintenance of the minimum ecological flow and the preservation of the ecosystem services provided by watercourses.

Within this framework, our study contributed to the broader sustainability agenda by assessing the efficiency of measures and practices adopted by Reclamation Consortia for managing supplemental irrigation. Our integrated approach provides an integrated view of how irrigation scheduling and infrastructural planning can enhance resource-use efficiency and ecosystem resilience. This approach directly supports SDG 2 (Zero Hunger) by improving the reliability of agricultural water supply under variable climatic conditions, SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation) by promoting efficient and equitable water allocation, SDG 13 (Climate Action) by fostering adaptive management in response to climate variability, and SDG 15 (Life on Land) through the preservation of ecological flows and associated ecosystem services.

The need to plan sustainable policies has led to the development of dedicated tools aimed at improving the decision-making process. At the Consortium level in Italy, the National Institute of Agricultural Economics (INEA) developed the Information System for Water Management in Agriculture (SIGRIA) [

47]. This georeferenced database supports public institutions in the planning and management of water resources at the river basin scale. Within the SIGRIA framework, the remote sensing-based DEMETER (DEMonstration of Earth observation TEchnologies in Routine irrigation advisory services) standard was created to assist irrigation advisory services by providing precise and timely information on crop water requirements [

47]. Similarly, the SWAMP (Smart Water Management Platform) project was developed to promote precision irrigation solutions tailored to crop needs and supported by Internet of Things (IoT) technologies [

48].

Starting from the 2022 growing season, the Piave Land Reclamation Consortium promoted the use of the IRRINET platform among all authorized users to provide irrigation advice synchronized with the scheduled irrigation turns. IRRINET is part of IRRIFRAME, a project of National Association of Drainage and Irrigation Consortia (ANBI) aimed at giving irrigation advice based and helping irrigation scheduling on the real water availability in irrigation supply channel or pipelines [

49]. The integration of this Decision Support System (DSS) into irrigation scheduling management justifies the score assigned to the Piave Consortium in

Table 6, along with the implementation of the demo version of IRRIBOOK by the Veneto Orientale Consortium. DSS for irrigation scheduling management still face critical challenges in ensuring optimal water resource use. Fais [

45] highlighted ongoing difficulties in accessing both up to date and historical data, identifying irrigated crops, and accurately estimating actual crop water consumption. Nevertheless, experimental evidence confirms the effectiveness of DSS in enhancing sustainable irrigation scheduling and water management [

50,

51].

4.3. Recommendations Applicable to Water Management Policies

The second objective of the investigation was to analyze the administrative procedures regulating water access, including the methods by which farmers submit water requests and the processes through which Consortia manage irrigation demands (

Table 2 and

Table 6).

Platforms for irrigation scheduling have significant potential to enhance decision making and support farmers and growers, particularly in countries where the average farm size is small [

52]. In these contexts, irrigation Consortia face the challenge of coordinating irrigation across numerous fields. Moreover, the diversity of crops cultivated by many small farms makes irrigation scheduling even more complex. This explains why only the Consortia Piave and Veneto Orientale received a good score, while Acque Risorgive remained at a medium level.

The analysis of governance practices should serve as a foundation for supporting Consortia in implementing optimal irrigation pricing systems. The results shown in

Table 6 indicate that there is room for improvement in this area. An optimal pricing system should standardize or clarify the cost structure to enable fairer and more sustainable pricing [

53,

54]. A study conducted in another Italian context [

53] proved that the systems where fees are based both on irrigated area and crop water requirements may be the most balanced as it reduces consumption and environmental impact. Moreover, it creates rational incentives for water savings, without penalizing small farms disproportionately. Moving forward, a key priority for Consortia should be the revision and rationalization of their pricing systems to enhance equity, efficiency, and environmental sustainability.

The third topic of the investigation on the managing efficiency of the three Consortia related to storage basins (

Table 3 and

Table 6).

Sustainable irrigation involves storing water prior to use in a way that avoids depleting freshwater resources and does not lead to the expansion of cropland [

55]. According to Schmitt et al. [

55], although there are currently storage basins capable of providing 2000 m

3/year of irrigation water compared to the 460 m

3/year required to ensure global food security, their inefficiency and losses make the construction of new basins necessary.

While the creation of water storage basins is considered a necessary practice for cultivation in areas subject to water stress, its effectiveness in reducing overall water demand is conditional on careful planning and specific environmental policies. A potential paradox emerges when an increase in efficiency and storage capacity does not lead to a reduction, but rather an expansion of irrigated areas [

56,

57]. This phenomenon, known as the “rebound effect,” implies that an apparently improved water infrastructure may not translate into a decrease in water demand [

58]. Therefore, storage basins can effectively contribute to mitigating the effects of water scarcity on agriculture only if they are accompanied by strict controls and regulations on irrigated areas [

59]. This risk is explicitly addressed in several EU policy instruments. The EU Water Framework Directive (2000/60/EC) requires Member States to maintain ecological flows and avoid overexploitation of water bodies, limiting the potential for expansion of irrigated areas. Similarly, the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) promotes sustainable water management through conditionality and eco-schemes, linking financial support to practices that ensure water savings rather than increased water use. Thus, while the development of new storage basins is a vital strategy for adapting to climate change, their long-term effectiveness is contingent on a comprehensive governance model. Such model should include strict limits on water withdrawals, in line with the EU Water Framework Directive, to protect ecological flows and prevent resource depletion.

Our investigation highlighted that the Italian Reclamation Consortia are undergoing an evolutionary phase, with significant differences in their capacity to manage water scarcity. While there is a shared commitment to optimizing irrigation, the results show that a well-structured model, supported by advanced technologies and optimal internal organization, demonstrates greater resilience and superior efficiency. Moreover, the findings underscore the need for coordinated action and a further evolution of the regulatory and managerial framework to meet the challenges posed by climate change. Structural differences between Consortia (such as geographic location in the canal network and the distribution of abstraction points) strongly influence resilience. The results stress the need to promote coordinated inter-Consortium management strategies.

4.4. Climate Adaptation Strategies

The agroclimatic trend in Italy in 2022 was marked by high temperatures and extremely low rainfall, whereas in 2023 most of the country experienced near-average temperatures and precipitation. In 2022, maximum temperatures frequently exceeded 37 °C, making it the hottest year on record. Combined with a severe rainfall deficit, particularly during summer, these conditions led to extreme drought. Average temperatures in 2022 were consistently 1–2 °C higher than in 2023, and rainfall was 336 mm lower (774 mm vs. 1110 mm).

According to ARPAV (

https://www.arpa.veneto.it, accessed on 11 August 2025), 2022 and 2023 were the two hottest years in the Veneto region in the past 30 years. Precipitation trends over the past three decades show no clear long-term change, though 2022 stands out for its exceptionally low totals and increased interannual variability in the last 15 years. Rainfall events have become less frequent but more intense. In 2022, February recorded only 3 mm of rain, while the normally drier summer months saw substantial rainfall, particularly in May and July. Overall, precipitation patterns were erratic, with a dry September followed by a very wet October.

The AquaCrop model results (

Table 8 and

Figure 4 and

Figure 5) provide a comparative analysis of irrigation volumes and events for maize, radicchio, and grapevine across two soil types (loamy and well drained), three irrigation systems (drip, sprinkler, and subirrigation), and two years (2022 and 2023). The results highlighted substantial differences in water requirements and irrigation frequency in response to soil type and climatic conditions.

Well drained soils generally required higher volumes across all crops, as rapid infiltration increased irrigation frequency to maintain adequate moisture. Loamy soils, with better water retention, typically needed less irrigation. Drip irrigation involved more frequent but lower volume applications, while sprinklers applied larger volumes with fewer events, potentially increasing evaporation losses. Subirrigation use was inconsistent, likely due to system or soil constraints.

Using AquaCrop outputs, this study assessed the capacity of Reclamation Consortia to meet agricultural water demand, considering existing infrastructure and withdrawal capacities from main conveyance canals in two contrasting years. The evaluation applied a standardized scenario in which all farmers cultivated the same crop using the same irrigation method, eliminating variability from crop calendars and technologies. In 2022, prolonged drought limited water availability across the study area. Model results indicate that the Consortia Piave and Veneto Orientale would have been unable to meet total demand, even with the most efficient systems. This deficit was most severe in peak summer months. An exception was radicchio in Consortium Piave, whose August planting coincided with lower overall demand, allowing water needs to be met. Consortium Veneto Orientale faced additional limitations due to its downstream location, which reduced withdrawal capacity through upstream abstractions and conveyance losses. Conversely, Consortium Acque Risorgive met demand in 2022, supported by multiple abstraction points and a dense canal network enabling flexible redistribution. However, much of its jurisdiction remained uncultivated due to agronomic and market constraints; thus, results apply only to actively farmed areas (

Table 8).

In 2023, higher rainfall frequency and increased winter precipitation improved water availability. Nevertheless, Consortium Piave would still have faced shortages for radicchio, as August rainfall was low during a sensitive growth stage, and for grapevine, due to limited spring precipitation. These results confirm that intra seasonal rainfall distribution, rather than annual totals, is critical to irrigation adequacy (

Table 8).

To address limitations of the Consortia Piave and Veneto Orientale, they should strengthen their water management capacity through infrastructural and operational improvements. In particular, the implementation of additional water storage structures (e.g., small or medium-sized reservoirs) would increase their ability to cope with prolonged dry periods and seasonal peaks in demand. Moreover, enhanced monitoring and maintenance of the irrigation network are essential to reduce conveyance losses and prevent unnecessary water waste. At the farm scale, Consortia should promote the adoption of more efficient irrigation systems and provide training programs to support farmers in improving on-farm water use efficiency.

The combined assessment showed that Reclamation Consortia are highly sensitive to rainfall timing and infrastructure capacity. Structural differences, such as geographic location in the canal network, abstraction point distribution, and conveyance efficiency, strongly influence resilience to water shortages. The persistent vulnerability of Consortium Veneto Orientale contrasts with the robustness of Acque Risorgive, underscoring the need for coordinated inter-Consortium management, infrastructure upgrades to reduce losses, and crop-irrigation choices aligned with projected seasonal water availability.

These findings are consistent with broader risk frameworks for irrigated agriculture under climate change, where hazard, exposure, and vulnerability together determine water scarcity risk [

45]. Garofalo et al. [

60] used AquaCrop to optimize irrigation volumes of tomato in southern Italy finding that moderate irrigation volumes (~300–400 mm per season) maximize the combination of yield, water productivity and economic return. Similarly, Busschaert et al. [

61] applied AquaCrop in a spatial distribution across Europe to project maize yield gaps and water productivity under future warming; their results underline how shifts in sowing dates and growing season length may offset water-limited yield losses. These studies sustain our use of AquaCrop to assess trade-offs between irrigation volumes under different environmental conditions.

Adaptation strategies should combine technological efficiency gains with diversified water sources, increased storage, and dynamic allocation policies that integrate hydrological forecasts with agronomic planning, to better safeguard agricultural production under uncertain future irrigation regimes [

62]. Although previous studies have examined technical or organizational aspects of Reclamation Consortia, none have provided a comparative assessment of supplemental irrigation efficiency. This study filled that gap by evaluating how structural, managerial, and infrastructural differences influence water-use efficiency and resilience in the Venetian Basin.

4.5. Limitations and Future Perspectives

Despite providing valuable insights into the functioning and adaptive capacity of Reclamation Consortia, this study presents some limitations. First, the AquaCrop model operates on simplified assumptions and includes uncertainties related to input data and calibration, particularly for perennial crops such as grapevine. Second, the analysis was limited to three Consortia within a relatively narrow geographical area, which may re-strict the generalization of results to other Mediterranean contexts. Moreover, only two consecutive irrigation seasons were considered, which constrains the ability to capture longer-term climatic variability. Finally, the development of sustainable irrigation strategies requires the integration of multiple expertise, from agronomy to hydrology and institutional governance, highlighting the need for interdisciplinary approaches and broader collaboration in future research. Future work should extend this framework to a wider spatial and temporal scale and test the performance of alternative decision-support and water-allocation models to strengthen the adaptive capacity of irrigation governance under changing climatic conditions.

5. Conclusions

This study assessed the critical role of Reclamation Consortia in the Venetian Plain in managing water scarcity under a changing climate. In addition to examining the management strategies of three Consortia, the analysis focused on supplemental irrigation practices across contrasting climatic years (2022–2023) and varying soil–crop–system combinations. Results showed that irrigation demand in 2022 was substantially higher due to extreme drought. Soil type, irrigation method, and crop species strongly influenced water requirements, while differences in Consortium performance were largely attributable to infrastructure, geographic location, and organizational capacity. Structural differences, such as the positioning in the canal network and the distribution of intake points, were directly connected to the persistent vulnerability in drought scenarios.

The adaptability of Consortia to climate change was closely linked to the flexibility of rotational schedules and the adoption of technologies and tools enabling efficient irrigation water management. Differences also emerged in fee structures and irrigation request procedures. Current gaps in storage basin management were mainly due to geographical constraints, but the findings underline the need for enhanced water storage capacity. While increasing water storage capacity is crucial to enhance resilience during drought periods, its development should be accompanied by strict governance measures to prevent the rebound effect, whereby improved infrastructure efficiency leads to higher overall water consumption. Thus, new infrastructure investments must be integrated with regulatory and monitoring actions in irrigated areas, in line with the principles of the Water Framework Directive, to ensure that efficiency gains translate into genuine water savings rather than increased demand. Our work contributes to the broader sustainability agenda by supporting SDGs 2, 6, 13 and 15, showing how coordinated governance, infrastructure planning, and irrigation practices can enhance water-use efficiency, agricultural productivity, and ecosystem preservation.

Looking ahead, Reclamation Consortia will face increasing challenges related to interannual rainfall variability, infrastructure limitations, and governance. Intra seasonal rainfall timing may be more critical than total annual precipitation in determining irrigation adequacy. To address these challenges, priority actions should include upgrading infrastructure to reduce conveyance losses, expanding the use of decision support systems integrated with real time monitoring, and fostering coordinated inter-Consortium strategies to manage strict water withdrawal limits in line with the Water Framework Directive. Furthermore, to better address drought periods it is crucial to increase water storage capacity, including through the optimization of Consortium canal network management. Finally, the review and rationalization of irrigation pricing systems should pursue a model that combines the irrigated area with the actual volume of water used, reflecting both land and crop water requirements. Such a system would enhance equity, efficiency, and environmental sustainability while providing rational economic incentives for water conservation. Future research should explore the replicability of these findings across other Mediterranean basins and the long-term effects of integrated governance and technological interventions under climate change scenarios.