1. Introduction

Climate change has emerged as a central issue in the discourse surrounding global sustainability and future well-being, exerting profound impacts on ecosystems, climate systems, as well as socio-economic structures. Thomas et al. [

1] estimated that by 2050, around 37% of species could be at risk of extinction under mid-range warming scenarios, which highlights the critical need to curb greenhouse gas emissions. As Solomon et al. [

2] demonstrated, the effects of elevated atmospheric CO

2 are largely irreversible on a millennial scale, with persistent sea-level rise and long-term reductions in dry-season rainfall continuing for centuries, even if emissions cease. Economic studies, such as that by Tol [

3], reveal that while the early climate change may yield marginal benefits, long-term impact will disproportionately harm vulnerable economies and ecosystems, underscoring the urgency of carbon emission management.

Many studies have explored the influencing factors behind carbon emissions across regions and sectors. In this direction, Gonz’alez and Mart’inez [

4] utilized decomposition analysis to examine CO

2 drivers in Mexico’s industrial sector from 1965 to 2003, indicating that industrial activity, structure and fuel mix significantly contributed to emissions growth, while energy intensity mitigated it. Loo and Li [

5] used trend analysis and decomposition to analyze carbon emissions from passenger transport in China, suggesting that road transportation is the primary emitter, with income growth as the dominant influencing factor. In addition, multiple linear regression has been used to examine energy-related carbon emissions in Turkey from 1971 to 2010, identifying population growth and fossil fuel consumption as the main driving forces [

6].

Energy consumption forecasting has emerged as a critical topic in global sustainable development, serving an essential role in mitigating climate change, guiding policy decisions and optimizing energy systems. Traditional statistical forecasting approaches typically rely on historical data for model construction [

7]. The advantages of such models lie in their simplicity and ease of implementation. Integrating regression models with artificial neural networks, Kialashaki and Reisel [

8] developed a new method for predicting residential energy demand in the United States. Xie et al. [

9] proposed an effective forecasting method for China’s energy production and consumption over the period 2006–2020 by combining a grey forecasting model with the Markov approach and optimization techniques. Yuan et al. [

10] developed a hybrid forecasting framework for China’s primary energy consumption that combines the autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) model with grey relational analysis, achieving superior performance compared with baseline models.

Although these statistical models offer high computational efficiency, their performance is limited when handling nonlinear complex data in practical applications; thus, many studies have explored various machine learning and hybrid approaches to forecast carbon emissions in different contexts [

11,

12,

13]. Based on the least squares support vector machine (LSSVM), Sun et al. [

14] conducted an analysis of carbon dioxide emissions from multiple sectors in China and developed a novel forecasting model. Acheampong et al. [

15] applied artificial neural networks (ANN) to simulate carbon emission intensity for the USA, Brazil, China, Australia and India. Ma et al. [

16] developed a new hybrid forecasting method by using association rule algorithm and optimized grey model, illustrating superior predictive performance and highlighting the challenges of China’s carbon emission reduction.

With the development of deep learning techniques, time series forecasting has achieved significant progresses. However, no single model is universally applicable for all scenarios. To address this, researchers have explored and developed a number of hybrid modeling approaches. Li et al. [

17] proposed an EA-LSTM model that incorporates evolutionary algorithms and attention mechanisms into LSTM, effectively enhancing temporal feature learning and improving prediction accuracy. Qiao et al. [

18] developed a hybrid method combining an improved lion swarm optimizer with traditional models, achieving better convergence and accuracy in carbon emission forecasting. Lin et al. [

19] constructed an attention-based LSTM model for cross-country carbon emission forecasting, effectively modeling regional characteristics and economic variations. Han et al. [

20] presented a coupled LSTM-CNN model for carbon emission prediction across 30 Chinese provinces, leveraging complementary strengths in sequence modeling and feature extraction. Based on quantile regression and attention-based bidirectional long short-term memory (BiLSTM) network, Zhou et al. [

21] proposed an ensemble forecasting model for predicting daily carbon emissions of five major carbon-emitting countries. Xu et al. [

22] developed a hybrid forecasting model for crude oil prices by integrating financial market factors, where commodity and foreign exchange were found to have significant impact on oil price volatility.

China, as the largest carbon emitter, has actively engaged in climate governance by unveiling its dual-carbon objectives in 2020, reaching a peak in carbon emissions by 2030 and achieving carbon neutrality by 2060 [

23]. However, China still faces significant challenges, including delays in restructuring its energy system and the disparities in emission reduction capacities between regions [

24]. Most existing studies rely on annual data, which fail to capture seasonal or quarterly fluctuations in emissions [

25]. Moreover, these models cannot account for complex external factors including economic cycles and policy interventions, resulting in limited prediction accuracy and robustness.

The impact of climate risk on the financial system is becoming increasingly prominent. Accurate prediction of carbon emissions has become a crucial research issue connecting environmental governance with financial decision-making. Recent research shows that there exists a close relationship between climate policy risk and asset prices. Dietz et al. [

26] introduced the concept of ’Value at Risk’ (VaR) to climate change by modifying the classic dynamic integrated climate-economy (DICE) model for probabilistic forecasting to assess the impact on economic output. Bolton et al. [

27] investigated whether carbon emissions affect the cross-section of US stock returns and found that stocks of firms with higher carbon emissions earn higher returns, indicating investors are pricing in carbon emission risks. More recently, scholars have examined the impact of economic policy uncertainty on corporate decisions related to carbon emissions and renewable energy, finding that heightened uncertainty tends to increase carbon emissions, with renewable energy consumption serving as a mediating factor in this relationship [

28].

The rest of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 illustrates the proposed STL-wLSTM-SVR model in detail. Next, the experimental setup, including data source and evaluation metrics, is presented in

Section 3. The experimental results for aggregate-level and sector-level carbon emission forecasts are presented in

Section 4. Subsequently, the model’s rationality is verified through two sets of comparison experiments in

Section 5. Some brief conclusions, limitations and future directions for this work are given in

Section 6 and

Section 7, respectively.

2. The Proposed STL-wLSTM-SVR Model

Carbon emission time series exhibit complex composite characteristics, which not only encompass long-term evolutionary trends such as economic cycles but also are influenced by policy interventions, seasonal variations and short-term demand shocks. Leveraging the capability of machine learning to process high-dimensional and complex data, an ensemble forecasting strategy that integrates multiple models can more effectively reduce the prediction errors inherent in single-model approaches.

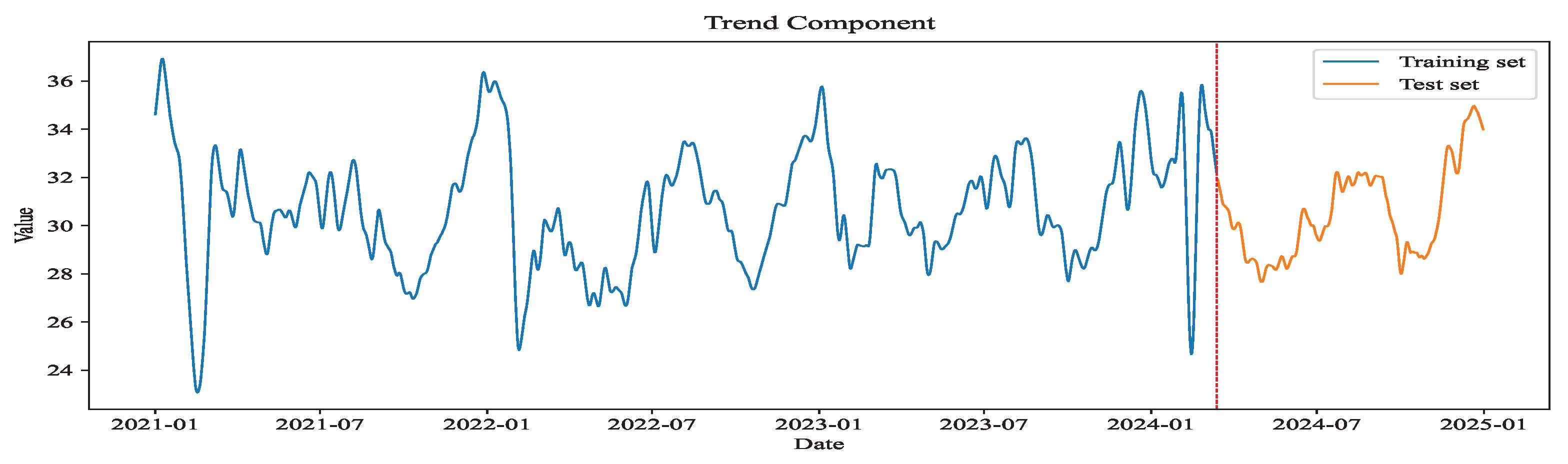

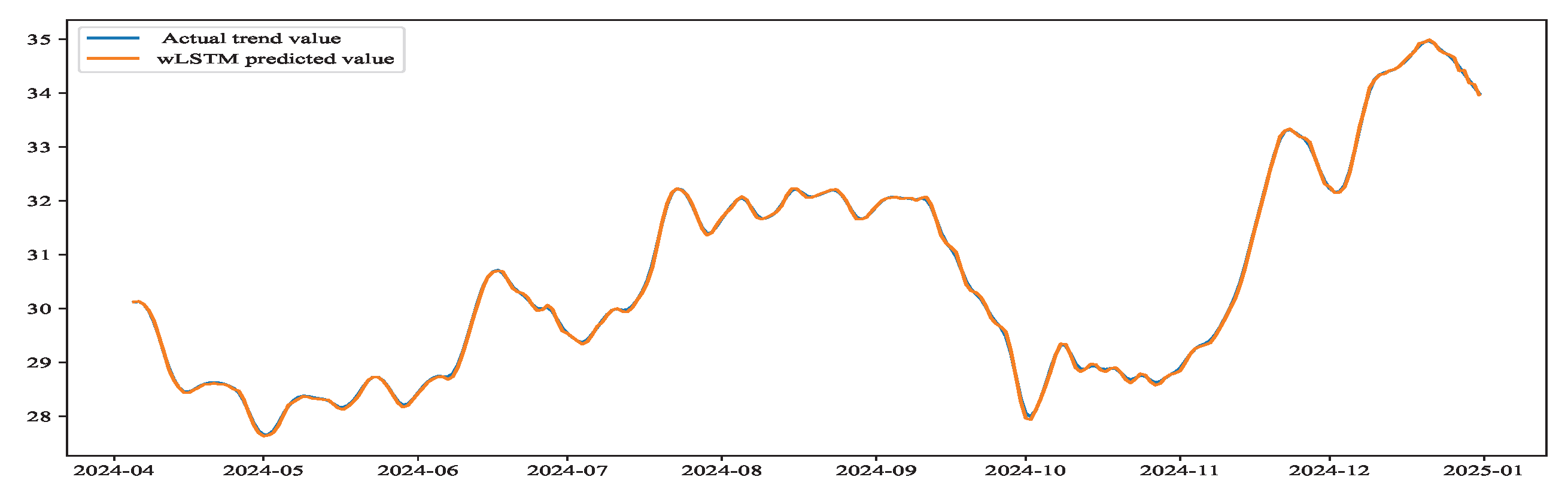

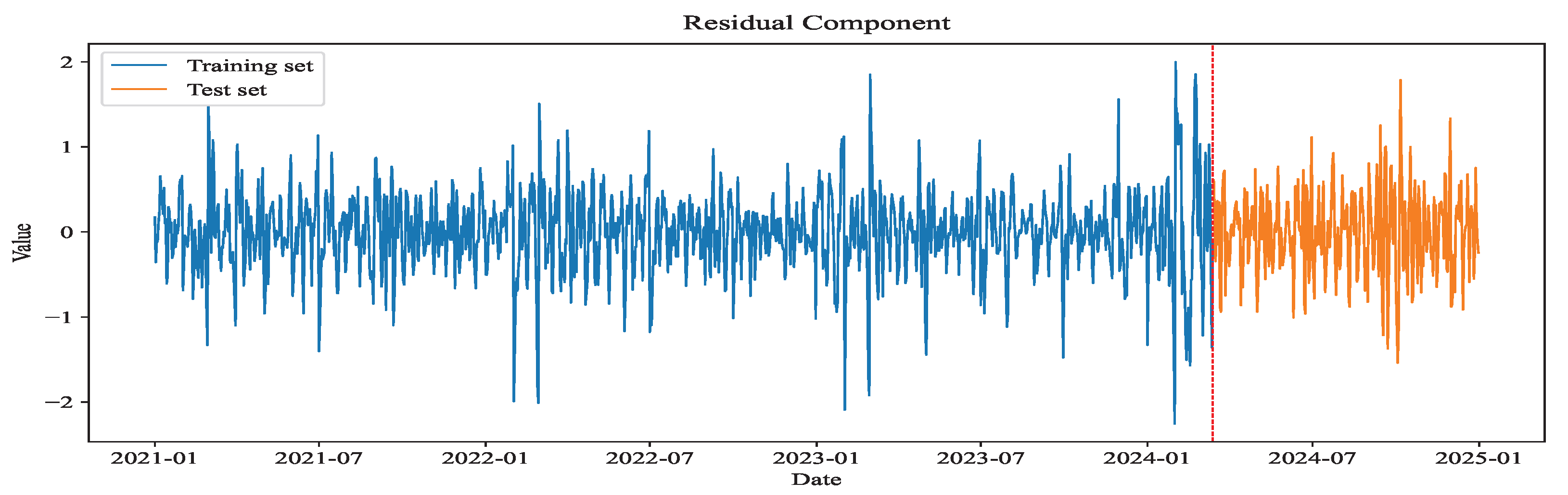

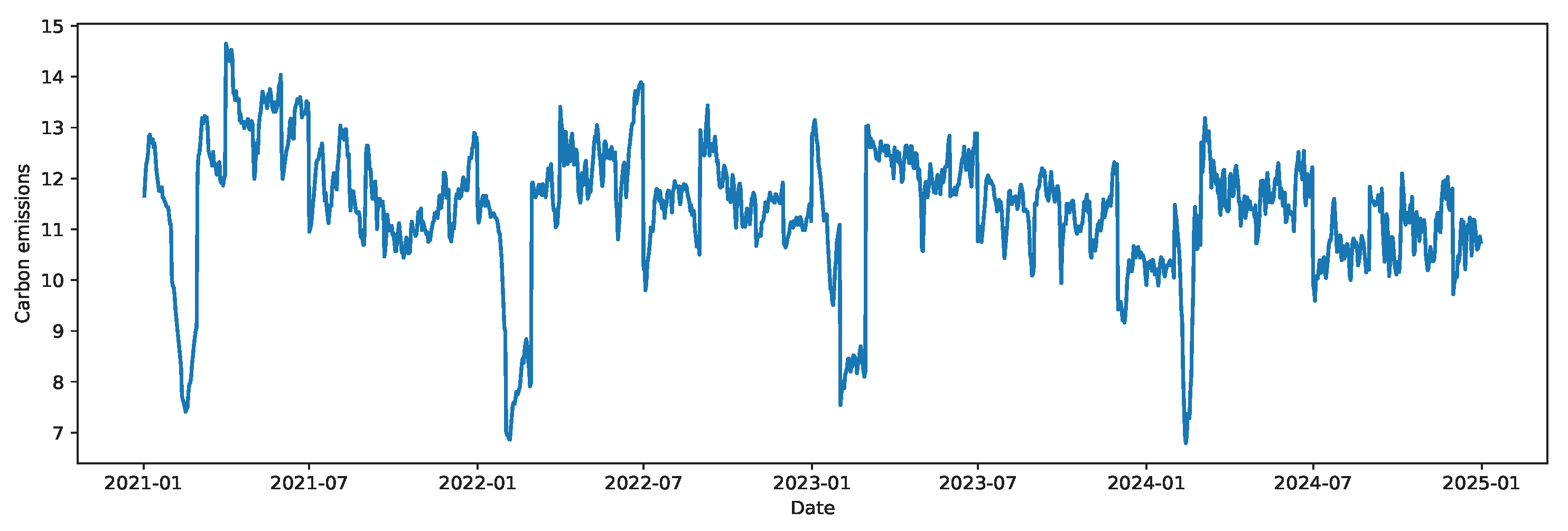

The proposed STL-wLSTM-SVR hybrid forecasting model is illustrated in

Figure 1, which consists of four phases. (1) Data preprocessing. China’s daily carbon emission data during 2021–2024 comes from the Carbon Monitor platform via the China Carbon Emissions Database. The dataset is then normalized and split. (2) Model selection. Four data decomposition models and seven single forecasting models are evaluated. The analysis identifies the STL decomposition method, long short-term memory (LSTM) network and support vector regression (SVR) as the most suitable components for different modules of the hybrid forecasting framework. (3) Combined prediction. In this phase, the STL decomposition method is first applied to decompose the carbon emission time series data into trend, seasonal and residual components. The LSTM model is then used for forecasting the trend and seasonal components, while the SVR model is used for forecasting the residual component. To enhance prediction accuracy, the WOA is employed for hyperparameter tuning in the LSTM model, while traditional grid search is applied for hyperparameter selection in the SVR model. (4) Forecasting results. The final predicted values are obtained by performing inverse normalization and combining the forecasted values of the three subsequences. The first two phases will be introduced in

Section 4, and the following focuses on the data decomposition and combined prediction modules.

2.1. Seasonal-Trend Decomposition Using Loess Method

The STL decomposition technique [

29], which applies seasonal-trend decomposition with Loess, is a widely adopted method in time series prediction. It is also widely used in anomaly detection and data cleaning. The core idea is to decompose a given time series into trend, seasonal and residual components using the locally estimated scatterplot smoothing (LOESS) method. As a non-parametric regression technique, LOESS dynamically adjusts time weights to accurately capture the trend features.

Carbon emissions data are often influenced by seasonal fluctuations (such as climate change and policy implementation cycles) and long-term trends (such as industrial development and energy transition). Additionally, due to factors like economic activity, policy adjustments and fluctuations in energy demand, the carbon emission series exhibit significant nonlinear characteristics. The STL method employs local regression to perform smoothing for accurately capturing such nonlinear relationships, and it can handle time series data with varying periodic and trending characteristics, making it highly suitable for the study of complex carbon emissions data.

2.2. wLSTM-Based Trend and Seasonal Prediction Module

Recurrent neural networks (RNNs), which specialize in processing sequential data, effectively model temporal dependencies owing to their memory-based architecture. However, when processing long sequences, RNNs are constrained by gradient vanishing or exploding issues. In response to this challenge, Hochreiter and Schmidhuber innovatively designed the novel long short-term memory (LSTM) networks [

30], depicted in

Figure 2.

The advantage of LSTM lies in its strong ability for extracting long-term and short-term dependencies in time series data, which can memorize seasonal patterns that span multiple cycles and track the evolution of trend components. Comparing with traditional recurrent neural networks, it can better capture asymmetric and abrupt features in emission fluctuations, such as trend shifts caused by policy changes or external shocks [

20].

The following equations define the forget gate

, input gate

, candidate cell state

, updated cell state

, output gate

and hidden state

[

30].

The complexity of LSTM originates from its unique network topology and diverse parameter configurations, with parameter settings crucial for performance and generalization [

31]. To enhance the performance of LSTM models, it is necessary to optimize hyperparameters such as the number of hidden layer neurons, learning rate and the number of iterations. Traditional hyperparameter tuning relies on manual trial-and-error, which is not only time-consuming but also prone to getting stuck in local optima. Therefore, this study introduces the WOA for tuning hyperparameters automatically [

32].

WOA is a nature-inspired intelligent optimization technique, whose core idea is to simulate the hunting behavior of humpback whales based on two mechanisms. One is encircling prey, which means that all candidate solutions gradually approach the current optimal solution, thus narrowing the search range. The other one is bubble-net feeding, which indicates that random walks and spiral movements are used to break free from local optima, expanding the parameter search space, thus balancing local search precision and global search breadth. Compared to manual tuning, WOA does not rely on experience-based preset parameter ranges. Through the iterative process, it automatically selects the optimal LSTM hyperparameter combination for the current forecasting task, reducing the subjective influence of human intervention and providing a reliable optimization path to improve the model’s predictive performance [

33,

34].

Specifically, the wLSTM algorithm consists of four steps as follows.

Step 1. Initializing the hyperparameters

For the seasonal and trend forecast in carbon emission series, the initial positions of the whale individuals are defined as the hyperparameter combinations of the LSTM model, including the input sequence length (time_step), the number of units in the LSTM layers (units1, units2), the number of training iterations (epochs), the batch size for each iteration (batch_size), the learning rate for weight updates (learning_rate) and the control parameters A and C.

Step 2. Training and evaluating model

The carbon emission series data are partitioned into training and test sets at an 8:2 ratio, where the training set is employed for model building and the test set is used to validate forecasting performance. For each set of hyperparameters, the training set is employed to train the LSTM model. Based on this, the fitness value is calculated to quantitatively evaluate the carbon emission prediction corresponding to the specific set of hyperparameters. The calculation formula is as follows:

where

and

correspond to the actual and predicted values of the seasonal component, and

N is the total data points. With the aid of (

4), the performance of hyperparameter combination

is evaluated.

Step 3. Updating optimal solution

Based on the current optimal solution

and the position of

, the position of the hyperparameter in LSTM is updated as follows [

32]:

where

A and

C represent search range and direction coefficients, respectively. Through the updating optimal solution, the current hyperparameter combination will gradually approach the optimal solution.

Step 4. Generating optimal LSTM hyperparameters

The optimization stops if the number of iterations reaches the maximum or if the error is less than the predefined tolerance coefficient . If the termination condition is not satisfied, return to step 3. Otherwise, the optimal hyperparameters with the smallest fitness value are obtained, which will be used to train the final LSTM model.

2.3. SVR-Based Residual Prediction Module

The support vector regression (SVR) [

35] algorithm, as an extension of support vector machine (SVM), is a robust and effective supervised learning method. This algorithm focuses on determining the optimal hyperplane that separates the data points by maximizing the distance to the nearest ones. In the case of linearly separable data, it adopts a hard-margin approach for maximization, while for non-linearly separable data, it utilizes kernel functions to project the input into a higher-dimensional space and addresses the optimization problem using a soft-margin technique.

The residual component, after STL decomposition, represents the noise-like remainder from which trend and seasonal patterns have been removed. It lacks significant periodicity and trends, often containing random disturbances such as short-term policy adjustments and temporary fluctuations in energy demand. Compared to complex deep learning models, SVR is simpler and more suitable for residual data, which typically have lower dimensionality and weak regular patterns [

36,

37].

The SVR model is trained with the following objective function [

35],

where

w refers to the weight vector,

b denotes the bias,

and

are the slack variables, and

and

C are the tolerance and penalty parameter, respectively.

When the data exhibit a nonlinear relationship, SVR uses the kernel function transformation to map the original data into a higher-dimensional feature space and then performs linear regression in that space. Several hyperparameters such as the kernel function, penalty coefficient C, kernel parameter and insensitive loss parameter are set to their initial values. Through the classic grid search method, all possible combinations are traversed in the hyperparameter space, and the optimal hyperparameter combination with the minimized RMSE or other metrics can be derived.

2.4. Research Assumptions

In this study, four research assumptions are proposed to ensure the robustness and generalization performance of the STL-wLSTM-SVR model.

First, we assume that after data decomposition, the obtained trend, seasonal and residual components of carbon emission series remain stationary or quasi-stationary, enabling time-series models based on historical patterns.

Second, we assume that decomposing carbon emission series and applying proper predictive models to its components can effectively capture linear and nonlinear dynamics.

Third, the prediction errors of each model in the hybrid method are assumed to be independent, which forms the basis for combining different models’ predictions to improve predictive accuracy.

Finally, we assume that external factors such as macroeconomic conditions and energy policies remain stable over the short-term forecast horizon, without abrupt disruptions that could significantly alter emission patterns.

6. Limitations and Future Directions

The proposed hybrid model achieved excellent performance in forecasting China’s total daily carbon emissions and sectoral emissions. This study is subject to several limitations, which, in turn, suggest promising future directions.

6.1. Limitations

(1) Model generalizability and regional heterogeneity

The proposed model achieves high prediction accuracy for forecasting China’s daily carbon emissions. However, its effectiveness is closely tied to the statistical properties of the studied data. When directly applied to other countries or regions, the model’s predictive accuracy may be restricted due to significant disparities in energy structures, industrial layouts and policy environments. Therefore, the model’s cross-regional generalization ability warrants further validation and refinement.

(2) Robustness to extreme events and structural breaks

A core challenge in time-series forecasting is maintaining model stability in the presence of outliers and sudden events. While the proposed model efficiently captures regular cyclical and trend components, its accuracy may fluctuate significantly when encountering public health crises (e.g., COVID-19), major policy shocks or extreme weather events. The model’s capacity to adapt to such structural breaks requires further enhancement.

(3) Spatiotemporal scale adaptability

This research focuses on China’s daily carbon emission forecasting at the aggregate and sectoral levels, without accounting for the multi-level characteristics of emissions across different spatiotemporal scales. For instance, local urban carbon emission hotspots exhibit significant spatiotemporal heterogeneity. The current model struggles to simultaneously predict short-term fluctuations and long-term trends or to capture the spillover effects of carbon emissions between regions.

6.2. Future Directions

(1) Integrating multi-source heterogeneous data and external factors

As future work, we can explore a more comprehensive forecasting framework by integrating multi-source and heterogeneous data. In addition to historical emissions data, future research is expected to incorporate a wider array of external variables. These include macroeconomic indicators (e.g., GDP, industrial value-added), energy and market data (e.g., price fluctuations in coal, oil, natural gas and carbon from the emissions trading system), as well as other drivers such as meteorological data and environmental policy texts. This will lead to more profoundly uncovering the underlying mechanisms of carbon emission dynamics, thereby improving the model’s predictive accuracy and logical consistency.

(2) Optimizing hyperparameter tuning algorithms

The hyperparameter optimization is often computationally intensive, which limits the model’s deployability in scenarios requiring high-frequency, real-time forecasting. More study on the intelligent optimization methods in forecasting models is worthy in the future, such as Bayesian optimization or reinforcement learning, to replace traditional grid search strategies. Dynamic hyperparameter optimization may be helpful to enhance the model’s applicability in real-time prediction contexts.

(3) Enhancing model interpretability and uncertainty quantification

To increase model transparency, future research will explore the use of techniques such as SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) or Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME). By analyzing the marginal contribution of each feature to the predicted values, one can provide policymakers with more insightful information. Furthermore, research may extend to interval and probabilistic forecasting. Quantifying the uncertainty of prediction results will provide a more robust assessment and sound decision-making.

7. Conclusions and Policy Implications

7.1. Conclusions

Accurate carbon emission forecast is not only essential for addressing the challenges of climate governance but also serves as a theoretical foundation for promoting the green transformation of socio-economic systems. Time-series forecasting remains one of the most challenging tasks in the prediction domain due to the superimposed characteristics of trend, seasonality, and randomness in the data. Constructing a specialized forecasting framework for specific scenarios not only requires overcoming the theoretical challenges of integrating multiple methods but also provides precise support for practical decision-making, thereby holding both significant theoretical innovation value and practical guidance.

The proposed hybrid forecasting model, STL-wLSTM-SVR, follows the framework of “selecting an appropriate baseline model–matching with a time series decomposition method–optimizing parameters in baseline models”. It fully integrates the strengths of STL decomposition (for accurate extraction of multi-scale features in time series), LSTM network (for capturing long- and short-term dependencies), SVR model (for improving nonlinear fitting accuracy), the WOA (for efficient global parameter optimization) and the grid search method (for ensuring reliability in parameter selection). While these are established techniques, their ingenious integration is empirically validated by the model’s exceptional performance. It achieved a high-precision forecast for China’s total daily carbon emissions (MAPE of 0.28%) and demonstrated remarkable adaptability across five sectors—from navigating the high volatility of ground transport (MAPE of 0.36%) to successfully handling the dramatic post-pandemic structural break in aviation (MAPE of 0.72%). These results not only verify the effectiveness of the hybrid framework in complex forecasting scenarios but also provide a valuable methodological reference for similar prediction tasks, such as sector-specific pollutant emissions and regional energy consumption.

7.2. Policy Implications

In this study, we proposed a high-precision short-term carbon emission forecasting model. The model’s accurate forecasting ability, especially in capturing the daily total carbon emissions and sector-specific emission dynamics, provides valuable insights for policy-making, industrial operations, and the development of carbon markets.

From the viewpoint of government governance, high-precision short-term forecasting models enable environment governance to shift from post-event evaluation to proactive early warning. Based on forecast data, governments can establish a dynamic warning system to implement targeted measures in advance—such as temporary traffic control and staggered industrial production—to address potential emission peaks. This achieves “peak shaving and valley filling” at a lower cost. Moreover, sector-specific forecast data help identify major short-term emission sources, providing a scientific basis for crafting differentiated and precise policies such as optimizing grid dispatch and promoting green transportation, thereby enhancing the effectiveness of environmental governance.

At the industrial operations level, accurate short-term emission forecasting facilitates low-carbon operations and cost optimization by enabling optimized production schedules that lower the systemic carbon footprint. For those enterprises engaging in carbon trading markets, this model may serve as a strategic tool for carbon asset management. Companies can develop flexible allowance trading strategies based on emission predictions, transforming passive compliance costs into proactive opportunities for economic value creation.

For the sustainable development of carbon trading markets, precise carbon emission forecasts act as a leading indicator for market demand. By reducing information asymmetry, these forecasts help stabilize market expectations and curb excessive price volatility. In the long term, a market consensus built on reliable data will promote the refinement of the carbon price discovery mechanism, allowing carbon prices to more accurately reflect marginal abatement costs. This creates a solid data foundation for developing carbon financial derivatives, thereby fostering the maturity and growth of China’s carbon finance markets.