1. Introduction

The digital economy has entered a new phase of development, with various industries progressively accelerating their digital transformation and upgrading. The deep integration of technologies such as Artificial Intelligence (AI), big data, and cloud computing is driving an explosive growth in computing power demand. The advanced deployment of computing power infrastructure is conducive to the deep integration of the digital and real economies, facilitating enterprise digitalization and urban green transformation. To seize market opportunities, countries around the world have actively deployed computing power centers, while local governments are promoting the construction of regional computing power centers through policy guidance, financial investment, and the integration of social capital, aiming to meet industrial upgrade demands and cultivate new quality productive forces in artificial intelligence. International Data Corporation (IDC) predicts that global data generation will reach 213.56 ZB in 2025, more than doubling to 527.47 ZB by 2029, with approximately 43% of this data being generated directly in the cloud. Furthermore, the global AI computing power market is projected to exceed $1.2 trillion in 2025 and reach $5.8 trillion by 2030, demonstrating a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of over 35%. Countries around the world have all regarded the construction of computing power centers as a key measure to seize the commanding heights of digital economic development.

However, during the rapid development of the computing power industry, computing power centers have presented a mixed landscape of good and bad due to constraints from various factors such as technological capabilities, infrastructure construction, and environmental adaptability. Unclear market demand, irrational planning of computing power resources, and frequent occurrences of indiscriminate investment following trends are commonplace, and the coexistence of low utilization rates at hub nodes and rapid node growth has not only resulted in resource wastage but also created difficulties for subsequent policy formulation.

The root of the problem lies in the lack of a scientific, effective, readily applicable, and comparable competitiveness evaluation mechanism for individual computing power centers, which is essential for assessing their competitiveness and analyzing development pathways. Existing research suffers from three fundamental shortcomings: a fragmented understanding of the factors influencing computing power center competitiveness, a lack of dynamic analysis of the formation mechanism, and poor applicability of evaluation systems.

To address these issues, this study conceptualizes computing power center competitiveness as a multidimensional and interactive complex system.

First, at the theoretical level, it breaks through the limitations of traditional single-factor analyses by innovatively adopting a complex systems theory perspective. This approach frames the formation of computing power center competitiveness as a dynamic interactive process between internal driving factors and external facilitating elements. The proposed theoretical framework reveals that enhancing competitiveness requires not only the optimized allocation and management of internal resources but also the dynamic evolution of the external environment and its organic coupling with the internal system. This mechanism facilitates efficient resource flow and promotes value-added growth, thereby providing a theoretical foundation for improving the competitiveness of computing power centers.

Secondly, at the methodological level, this study constructs a logically closed-loop evaluation system from the perspective of enterprise operators and applies it to the actual operational scenarios of individual computing power centers. By employing the entropy weight-TOPSIS-gray relational analysis method, a fully quantitative, self-consistent, and directly applicable evaluation framework for computing power centers is established. This framework provides a data-driven, highly applicable, universally valid, and comparable decision-making tool for assessing the competitiveness of computing power centers.

Finally, at the practical application level, based on Chinese data, this study identifies development pathways for computing power centers and proposes a dual-engine strategy focusing on technology and cost. This approach not only supports the sustainable development of computing power centers themselves but also provides a solid theoretical foundation and practical decision-making tools for the long-term development of the global computing power industry.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Influencing Factors of Computing Power Center Competitiveness

The identification of influencing factors is the key to the competitiveness analysis of computing power centers, and their targeted optimization helps to improve the overall efficiency of resource allocation. In terms of technical capabilities, Li et al. pointed out that technical capabilities in hardware equipment, software systems, and information security determine the competitive strength of computing power centers from the perspective of foundational capabilities [

1]. With technological advancement, Data Center Infrastructure Management (DCIM), as a key solution enabling seamless integration of various functional modules, has become a core element for the long-term development of computing power centers. Wang et al. emphasized that computing power centers require not only fundamental service capabilities but also refined and systematic management through the integration of software and hardware, facilitating real-time routine equipment start-stop operations and assisting users in making more informed decisions [

2,

3]. In terms of operational costs, Sardjono W et al., based on the characteristic that energy costs represent the largest proportion of operational expenses, pointed out that the level of energy-saving technology (particularly energy-saving technology for refrigeration equipment), electricity prices, and the energy mix determine the development scale of computing power centers [

4,

5]; Uddin et al. indicated that green Information Technology (IT) technologies and intelligent operational management better align with the future development direction of computing power centers, and both have become key influencing factors for maintaining competitive advantage [

6].

Existing research has provided a multi-angle analysis of the influencing factors of the competitiveness of computing power centers, and initially revealed the impact of the interaction among these factors on the overall competitiveness. However, existing research has predominantly examined the impact of factor accumulation on competitiveness from an isolated perspective, lacking an integrated analysis grounded in the holistic nature of complex systems. This fragmented analytical approach undermines a deeper understanding of the root causes of competitiveness formation and offers limited systematic decision-making support for managers regarding the synergistic allocation of resources. This limitation represents precisely the gap that our study aims to address by introducing a complex systems perspective.

2.2. Formation Mechanism of Computing Power Center Competitiveness

Analyzing the formation mechanism helps reveal pathways and key elements for enhancing competitiveness, providing theoretical support for resource utilization and development decisions. At the macro level, Christensen D J et al., based on evidence from Nordic countries, indicate that data center development is determined by the combined effects of numerous factors, including political stability, rapid market entry policies, and stable power supply [

7]. Qin et al. pointed out that the construction level of computing power infrastructure is primarily shaped by factors such as industrial cluster development, spatial layout, resource sharing coordination, and the intensity of policy support, while also analyzing industrial development pain points including supply-demand imbalance and uneven distribution of foundational resources [

8,

9]. At the micro level, Reddy et al. indicated that data center performance evaluation is shaped by multiple dimensions including energy efficiency, cooling, networking, and security [

10], while Tong et al., from a technical architecture perspective, pointed out that the competitiveness of computing power centers primarily relies on four key pillars: green intensive construction, multi-source heterogeneous integration, hierarchical storage-computing coordination, and lossless transmission networking [

11].

Existing research has explored the formation mechanism of computing power center competitiveness from multiple perspectives, ranging from macro-level policies and industrial clusters to micro-level technical architecture and performance standards. However, these studies are largely confined to static structural analyses or unidirectional causal chains, lacking an in-depth explanation of the two-way feedback and coupling mechanisms between internal driving forces and external traction forces. This analytical disconnect makes it difficult to fully reveal how computing power centers achieve a spiral rise in competitiveness through the dynamic flow and adaptation of internal and external resources. To bridge this research gap, this study develops an integrated formation mechanism model based on complex systems theory, incorporating internal factors, external factors, and resource flow pathways. This model aims to systematically unveil how the internal and external subsystems drive the emergence of competitiveness through co-evolution, thereby providing a more comprehensive theoretical explanation for understanding its dynamic formation process.

2.3. Evaluation System for Computing Power Center Competitiveness

The establishment of a scientific evaluation system can provide a quantitative basis for policy formulation and operational optimization of computing power centers. Relevant research has predominantly focused on computing power measurement and comprehensive computing power indices constructed by domestic and international institutions. Amid the trend towards increasingly diversified and efficient computing power demands, IDC has proposed a global computing power index evaluation system based on four dimensions: computing capability, computational efficiency, application level, and infrastructure support. And based on factors such as the computing power index score, cluster analysis of sub-indicators, and the contribution of incremental index units to GDP growth, countries are categorized into three tiers: leader, chaser and starter [

12,

13]. The China Computing Power Conference employed statistical methods to construct a comprehensive computing power index evaluation system across four dimensions: computing power, storage capacity, transport capacity, and environmental factors. Building upon this framework, the China Academy of Information and Communications Technology (CAICT) enhanced the evaluation of technological innovation capability by incorporating third-level indicators such as the total investment in hardware and software research and development (R&D) and the total number of authorized invention patents and software copyrights [

14,

15]. In the field of theoretical research, Daim et al., with sustainability as the core, constructed an evaluation indicator system based on multiple key dimensions such as infrastructure, technological level, energy efficiency, cooling, and green attributes. This provides theoretical guidance for the efficient construction and realization of green, environmentally friendly, and low-cost operation of computing centers [

16,

17,

18]. Existing research has explored computing power evaluation systems from various perspectives, revealing the fundamental characteristics of computing power centers. However, the construction of evaluation systems for individual computing power centers still requires further investigation.

Existing research has explored computing power evaluation systems from various dimensions, including computing power measurement, comprehensive index construction, and sustainable development. However, significant applicability and methodological limitations emerge when applying these existing evaluation systems to assess the competitiveness of individual computing power centers. On the one hand, most evaluation frameworks are designed for macro-level comparisons at the national or regional level, making their indicator selection and weighting systems difficult to apply directly for measuring the relative competitiveness of individual operational entities. On the other hand, existing research mostly relies on subjective weighting methods in methodology, which are prone to introducing biases, or uses a single evaluation model, which is difficult to simultaneously take into account the absolute distance and morphological trend of data distribution. When dealing with the assessment of the complex system of competitiveness, its robustness is insufficient. These limitations make it difficult for the existing system to provide a quantifiable, reusable decision-making tool suitable for horizontal comparison among individual computing power centers. To address this, our study innovatively proposes a hybrid evaluation framework. This framework not only establishes a practically applicable competitiveness evaluation system for individual computing power centers but also, through objective weighting to eliminate subjective bias and the integration of Euclidean distance with gray relational degree, constructs a more adaptive, stable, and comparable quantitative assessment mechanism for competitiveness. Ultimately, it aims to provide methodological support for the precise diagnosis and pathway optimization of individual computing power centers.

In summary, existing research exhibits three fundamental limitations: a fragmented understanding of influencing factors, an oversimplified and static description of the formation mechanism, and a lack of a practical and robust evaluation system applicable to individual computing power centers. These limitations stem from a common root cause: the failure to adequately conceptualize and systematically study computing power center competitiveness as a multidimensional, interactive, and highly complex system.

To address these gaps, this study constructs a comprehensive research framework grounded in complex systems theory. First, it develops a formation mechanism model from a complex systems perspective to elucidate the dynamic interactions and co-evolution between internal driving factors and external traction forces. Second, it establishes a fully quantifiable, readily applicable, and easily comparable evaluation system. Finally, it employs an entropy weight-TOPSIS-gray correlation method to construct the competitiveness evaluation methodology for computing power centers. Consequently, through an empirical analysis of 35 computing power centers in China, actionable development pathways are derived. Through this systematic research approach, this study aims to provide a solid theoretical foundation and a practical decision-making toolkit for enhancing the competitiveness of computing power centers and guiding their sustainable development.

3. Theoretical Model

The formation of a computing power center’s competitiveness is a dynamic, relative, and complex process within an open environment, making it difficult to uncover its true essence through linear causal reasoning. Complex systems theory emphasizes that a system is a dynamic entity organically composed of numerous internal and external elements, where the interconnections, interactions, and mutual constraints among micro-level agents give rise to macro-level complex phenomena [

19]. Accurate prediction of the system cannot be achieved by analyzing the characteristics of its individual components alone; it is imperative to decipher the interactions among the system’s elements to understand its formation mechanism [

20,

21]. Applying complexity thinking to examine and analyze the formation mechanism of computing power center competitiveness helps to deeply explore its essential characteristics. From a complex systems perspective, the competitiveness formation model of a computing power center consists of internal influencing factors, external influencing factors, and resource flow pathways, with competitiveness emerging precisely from the co-evolution of internal resources and the external environment.

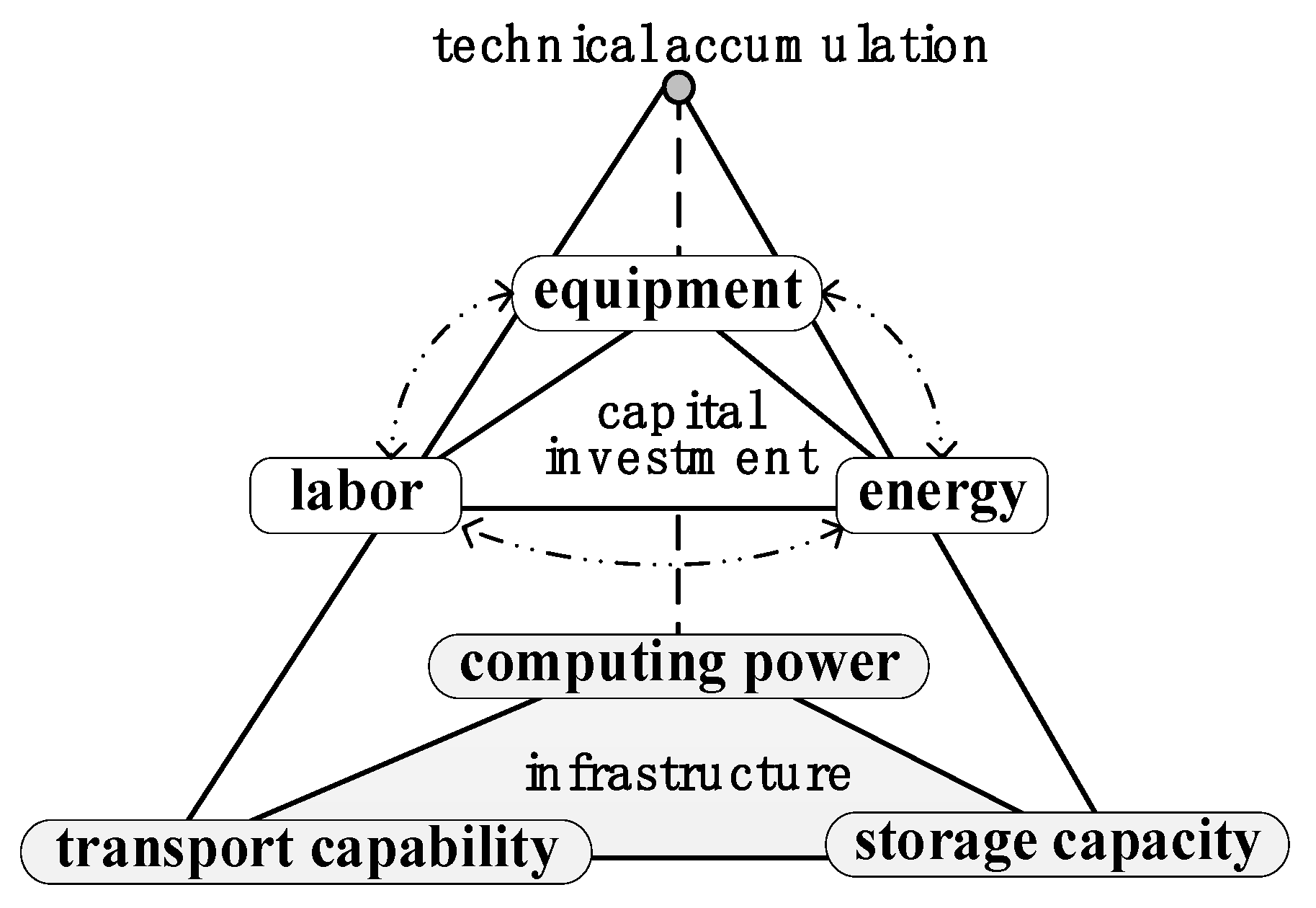

3.1. Internal Factors

Internal factors play a decisive role in shaping the computing power center competitiveness, serving as the core force underpinning competitive advantage. The internal drivers of a computing power center’s competitiveness form an organic combination of infrastructure, capital investment, and technological accumulation, as shown in

Figure 1.

3.1.1. Infrastructure

The three dimensions of computing power, storage capacity, and transport capability form the cornerstone of a computing power center’s competitiveness. These represent not only the physical hardware infrastructure supporting daily operations but also the system architecture and operational mechanisms underpinning business development and flexible resource allocation. The level of infrastructure development not only establishes the foundation for the computing power center services through the dynamic synergy among these three elements but also enhances service resilience through their deep integration. This integration ultimately determines the center’s flexibility and scalability.

3.1.2. Capital Investment

Funding serves as a critical resource for sustaining the efficient operation of the computing power center, with its utilization efficiency being key to an organization’s ability to navigate complex market environments and withstand market fluctuations. The operational costs of the computing power center primarily encompass equipment procurement costs, labor costs, energy costs, and maintenance expenses. Given that electricity constitutes the primary production resource for computing power centers, achieving efficient, low-carbon energy utilization while reducing energy costs is central to optimizing their cost structure.

3.1.3. Technology Accumulation

Technological resources are the core elements enhancing the competitiveness of computing power centers. The innovation, adaptability, and forward-looking nature of proprietary technologies directly determine a computing power center’s stable operational capability in complex environments and its future growth potential [

22]. Continuous hardware upgrades and systematic software optimization directly impact a center’s computing power, storage capacity, and transport capability. Furthermore, technological interoperability and system integration levels determine the overall efficiency and collaborative capabilities of the computing power center.

3.2. External Factors

External factors play a supplementary and catalytic role, accelerating or constraining the effectiveness of internal factors, thereby providing external impetus for competitiveness formation. External traction exists outside the competitiveness system of computing power centers, stimulating and propelling the system toward self-renewal and optimization upgrades. It primarily originates from four entities: supply chain partners, user groups, market competitors, and the government.

3.2.1. Supply Partners

Computing power centers can establish cooperative networks with supply chain partners aimed at technology sharing and resource complementarity, which can significantly enhance service quality and operational efficiency. Among these, securing a green, stable, and affordable power supply from electricity providers and obtaining the latest technological information from equipment manufacturers are key to maintaining service stability and optimizing operational costs.

3.2.2. User Groups

A diverse and stable user base not only directly impacts the profitability of a computing power center but also determines its market positioning and long-term growth potential [

23]. A user base spanning multiple industries enhances flexibility and adaptability, while a stable customer base secures revenue streams and builds corporate reputation, thereby providing robust support for business innovation and continued market expansion.

3.2.3. Market Competitors

Market competition pressure serves as the primary driving force propelling enterprises to forge competitive advantages [

24]. As the number of competitors increases and user expectations for service quality rise, market competition intensifies. This compels computing centers to continuously improve their products and services, optimize resource allocation, and reduce average unit costs in order to gain a competitive edge.

3.2.4. Government

The government plays a foundational and guiding role in the operation of computing power centers. Through policies spanning industrial planning, fiscal incentives, market mechanism design, and green low-carbon orientation, the government not only directly influences the operational costs, technological approaches, and strategic positioning of these centers but also indirectly stimulates industrial investment and optimizes the market environment by shaping market expectations and the industry ecosystem.

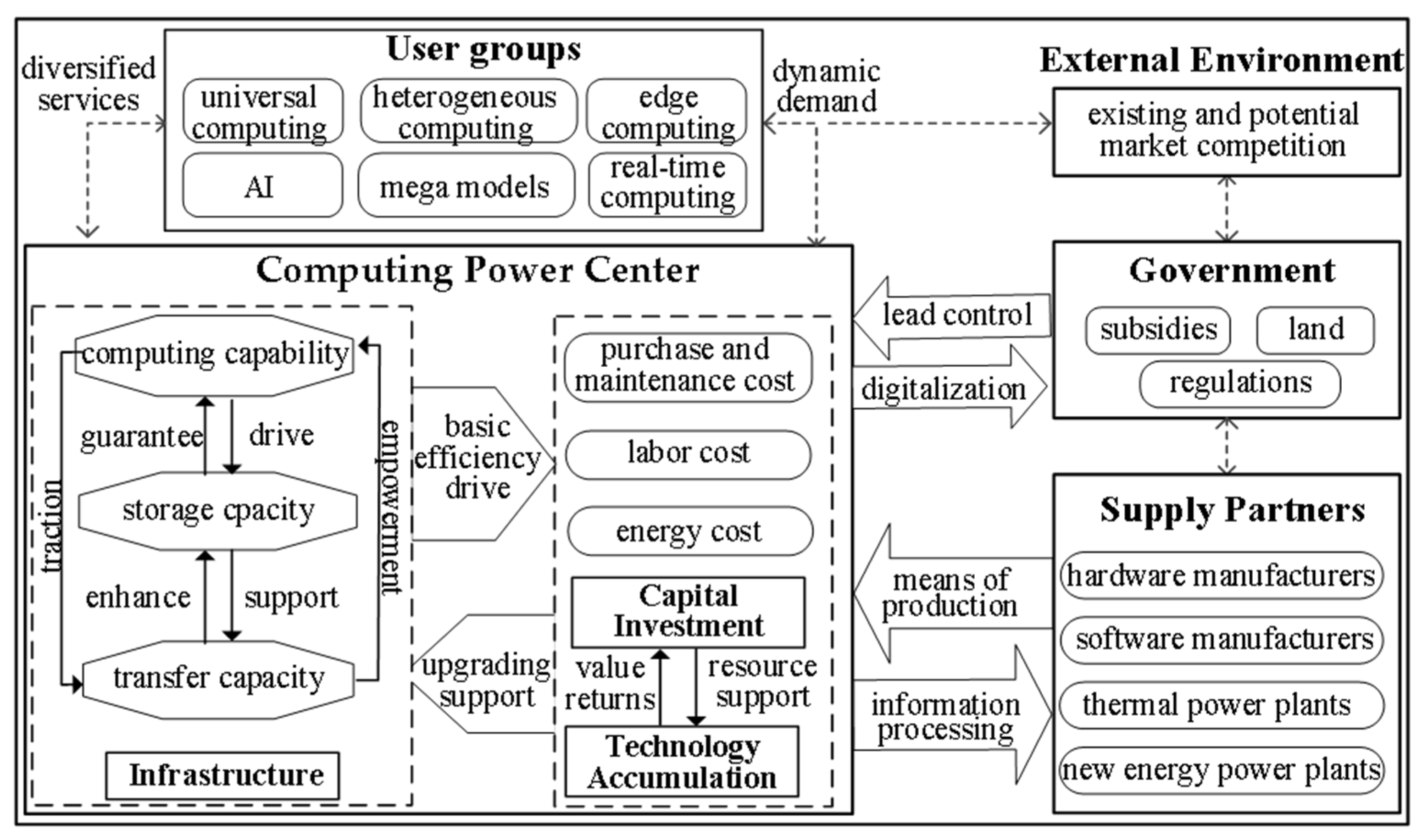

3.3. Formation Mechanism

The formation of the computing power center’s competitiveness can be viewed as a dynamic process of resource acquisition and utilization, involving the interaction of multiple factors, as shown in

Figure 2. It relies not only on the optimal allocation and management of internal resources but also on the dynamic changes in the external environment and the organic coupling of internal systems to achieve efficient resource flow and value enhancement.

3.3.1. Internal Factors Synergize to Optimize Resource Efficiency

Infrastructure, capital investment, and technological accumulation collectively form the internal drivers of a computing power center’s competitiveness, representing its resource allocation across various domains. Effective interaction among these factors ensures the computing power center’s efficiency and flexibility in resource utilization. First, the stability and sophistication of infrastructure lay the groundwork for the effective operation of other resources, and its development is a systematic process. It requires not only substantial financial investment to sustain daily operations but also advanced technical capabilities to support the continuous expansion of the computing power center, ensuring resilience in the face of complex environmental fluctuations. Secondly, financial support serves as the core safeguard for infrastructure development, technological research and development, and talent cultivation. The effective allocation of funds must not only meet immediate needs but also drive long-term development through strategic investment. Leveraging feedback mechanisms, capital investment propels the overall advancement of the system, thereby enabling efficient reinvestment and capital appreciation. Finally, technological innovation not only enhances the operational efficiency of the computing power center but also drives the optimization of equipment functionality and the precise allocation of capital. It triggers synergistic effects among various internal factors, propelling infrastructure and capital allocation toward greater efficiency. These three elements complement and reinforce each other, creating a virtuous cycle that enables the computing power center to maintain high efficiency and flexibility in resource acquisition and allocation, service delivery, and innovative practices.

3.3.2. External Factors Interact to Respond Swiftly to Market Changes

The computing power center has formed a dynamic, interconnected and mutually reinforcing relationship network with four major external factors. The positive interaction mechanism of this network of relationships not only provides a strong impetus for the sustainable development of computing power centers, but also helps them achieve efficient resource flow in the fierce market competition. Firstly, the computing power center acquires feedback information through in-depth interaction with users, promptly identifies market opportunities, and adjusts product service and resource allocation strategies, thereby creating growth points. Secondly, computing power centers need to closely monitor the movements of their competitors. Technological breakthroughs by competitors will force computing power centers to increase their research and development expenses, and changes in pricing strategies by competitors will prompt computing power centers to adjust their service models. Finally, as the synergy effect of the industrial chain deepens, establishing a deep cooperative relationship between computing power centers and suppliers is a key path to obtaining the latest equipment and the most economical resources in a more timely and stable manner than competitors. In addition, government guidance will directly influence the market competition pattern and directly change investment decisions and supplier choices. Policies will also be influenced by market demand and competitive dynamics, forming an interactive and sustainable development relationship.

3.3.3. Internal and External Factors Coupling to Enhance Overall Efficiency

Internal driving forces and external traction forces do not exist in isolation. They are organically coupled to form a synergy, jointly promoting the continuous progress of computing power centers in technological innovation, resource integration, and market adaptability, thereby maintaining long-term market competitiveness and achieving sustainable development. In this process, based on the construction of the new power system and the requirements of low-carbon policies, it has become an inevitable trend for power enterprises and computing power centers to develop in a coordinated manner through a two-way feedback mechanism. Power enterprises provide green and low-cost electricity for computing power centers, optimize the cost structure and promote green transformation. Computing power centers not only facilitate the consumption of renewable energy through large-scale electricity demand but also achieve real-time power dispatching and predict electricity demand through high-level data processing capabilities, thereby promoting the reform of the power mechanism. The two achieve a spiral effect of electricity driving the green upgrade of computing power and computing power facilitating the digital transformation of electricity through organic coupling.

4. Methodology

4.1. Identification of Key Influencing Factors

Based on the preceding analysis, this study identifies the primary factors influencing the competitiveness of computing power centers from both internal and external dimensions, converting these factors into quantifiable metrics. The objective is to provide a theoretical basis for optimizing resource allocation and formulating sustainable development strategies.

Internal influencing factors can be categorized into infrastructure level, operational cost structure, and technological innovation capability. The infrastructure level dimension can be further detailed into computing power, storage capacity, and transport capability. Among these, computing capability is represented by floating point operation capability and concurrent operations number; storage capacity is represented by the capacity of configured server storage and external storage devices; and transport capability is represented by two indicators: network egress bandwidth and network latency, which reflect broadband load capacity and data transmission speed. In the dimension of operational cost structure, considering the operational characteristics of the computing power center, the electricity cost—which accounts for 50% of operating cost—is measured using the Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE) and the electricity price, while the labor cost is represented by the regional average annual salary in the information industry. In the dimension of technological innovation capability, quantification is achieved jointly through R&D investment and the number of patent applications.

Regarding external influencing factors, given that the computing power industry remains in its nascent stage, the market competition landscape is subject to frequent adjustments due to market dynamics, and the performance of supply chain partnerships exhibits relative homogeneity. Therefore, the two factors of market competition and supply partners, which lack comparability, are excluded. Shelf rate and business revenue are used to quantify market performance and commercial benefits to measure the competitiveness of computing power centers at the business level. Government support is quantified by the frequency of the digital economy term in government work reports. Additionally, considering that temperature is a primary factor influencing equipment energy consumption, the annual average temperature is incorporated as an external resource in the evaluation.

4.2. Evaluation Index System for Computing Power Center Competitiveness

Based on the identification of key influencing factors, a computing power center competitiveness evaluation index system is constructed. This system features the goal level focused on competitiveness evaluation, the criteria level comprising infrastructure level, operational cost structure, technological innovation capability, and external resource environment, and the indicators level consisting of 13 key influencing factors. Among these, a15, a21, a23, and a43 are negative indicators, as shown in

Table 1.

4.3. Comprehensive Evaluation Model for Computing Power Center Competitiveness

The selection of an appropriate evaluation method is crucial for establishing a robust and credible assessment system. Given that all evaluation indicators are quantitative, we employ the entropy weight method to determine objective indicator weights, effectively minimizing subjective bias.

Furthermore, considering the characteristics of the evaluation indicators and the research objectives, the TOPSIS-gray correlation method was adopted for the evaluation. This hybrid method was chosen based on its comparative advantages over alternative approaches. In contrast to the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), our model is more objective and data-driven. Unlike Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA), which often fails to provide a clear ranking for all units, our method delivers a complete and stable ordinal ranking. Additionally, while the standalone TOPSIS focuses exclusively on Euclidean distances to ideal solutions and may overlook data trends, and Gray Relational Analysis (GRA) alone captures geometric shape similarity but ignores absolute distances, their integration offers a superior solution.

The applicability of the method also underpins its selection. The TOPSIS-gray relational method demonstrates unique advantages in emerging industry research. It simultaneously considers both the absolute position and morphological trends of the data sequence for each computing power center. This integration generates more stable and reliable ranking outcomes, effectively addressing the complexity and dynamic nature of the competitiveness system as outlined in the theoretical model. Critically, the method remains robust under conditions of information scarcity, which is a common challenge with nascent industry data. This approach establishes a data-driven, highly applicable, and universally valid decision-making tool, thereby providing a robust scientific basis for our evaluation.

The specific steps are as follows:

- (1)

Assuming there are m computing power centers to be evaluated and n competitiveness evaluation indicators for these centers, construct the competitiveness evaluation indicator matrix

as shown in Equation (1).

- (2)

The indicators are then normalized according to Equation (2) to eliminate dimensional differences, resulting in a normalized decision matrix Y

- (3)

Subsequently, the proportion

of the j-th indicator in the sum of all indicators for the i-th solution, the entropy value

of the j-th indicator, and the divergence coefficient

of the j-th indicator are calculated according to Equation (3). A larger divergence coefficient

corresponds to a smaller entropy value

, resulting in a greater weight for the j-th indicator and consequently a more significant role in the solution evaluation. Conversely, a larger entropy value

leads to a smaller weight for the j-th indicator and a less significant role in the evaluation.

- (4)

Calculate the weight

for the jth indicator and construct the weighted normalized decision matrix U

, as shown in Equation (4):

- (5)

Define the positive ideal solution

and negative ideal solution

of the weighted decision matrix according to Equation (5).

- (6)

Calculate the Euclidean distances

and

between the computing power center under evaluation and the positive and negative ideal solutions, respectively, as well as the gray correlation coefficients

and

between the computing power center under evaluation and the positive and negative ideal solutions, respectively, according to Equations (6) and (7):

- (7)

Calculate the closeness degree

and

between the evaluated computing power center and its positive and negative ideal values, ultimately deriving the relative closeness degree

. As shown in Equation (8). A larger value of the relative closeness degree

indicates that the evaluation object is closer to the positive ideal solution, reflecting a higher level of competitiveness. Conversely, a smaller value indicates a greater distance from the positive ideal solution, reflecting a lower level of competitiveness.

5. Empirical Analysis

5.1. Sample Selection and Data Sources

To ensure the representativeness and scientific validity of empirical findings, this study selected 35 operational computing power centers with capacities exceeding 40 PFlops, based on regional distribution disparities across China’s computing power centers. These centers comprise 20 in the East, 3 in the Northeast, and 6 each in the Central and Western regions, as shown in

Table A1.

Regarding data sources, this study utilizes statistical yearbooks and local government reports from the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) and the Academy of Information and Communications Technology (AICT). Additionally, adhering to compliance principles, Python version 3.9 web scraping technology was employed to extract relevant 2023 performance and operational data from technical specification pages, service documentation, and news announcements on the official websites of computing centers and cloud computing platforms. Following data cleansing and structuring, a comprehensive dataset required for analysis was ultimately constructed.

5.2. Results

First, STATA MP 18 software was employed to assign weights to the computing power center competitiveness evaluation indicators based on the entropy weight method, in order to quantify the variability of indicator information across samples and ensure that the weights of the computing power center competitiveness evaluation indicators accurately reflect the importance of each indicator in the overall evaluation. The weight results are shown in

Table 2.

Second, using Matlab R2023a software, the weighted normalized decision matrix was constructed, and the weighted decision values along with the positive and negative ideal solutions for the computing power center competitiveness evaluation indicators were derived. Following this, Equations (6) and (7) were applied to calculate the Euclidean distances and gray correlation coefficients between the computing power centers and the positive and negative ideal solutions, as presented in

Table 3.

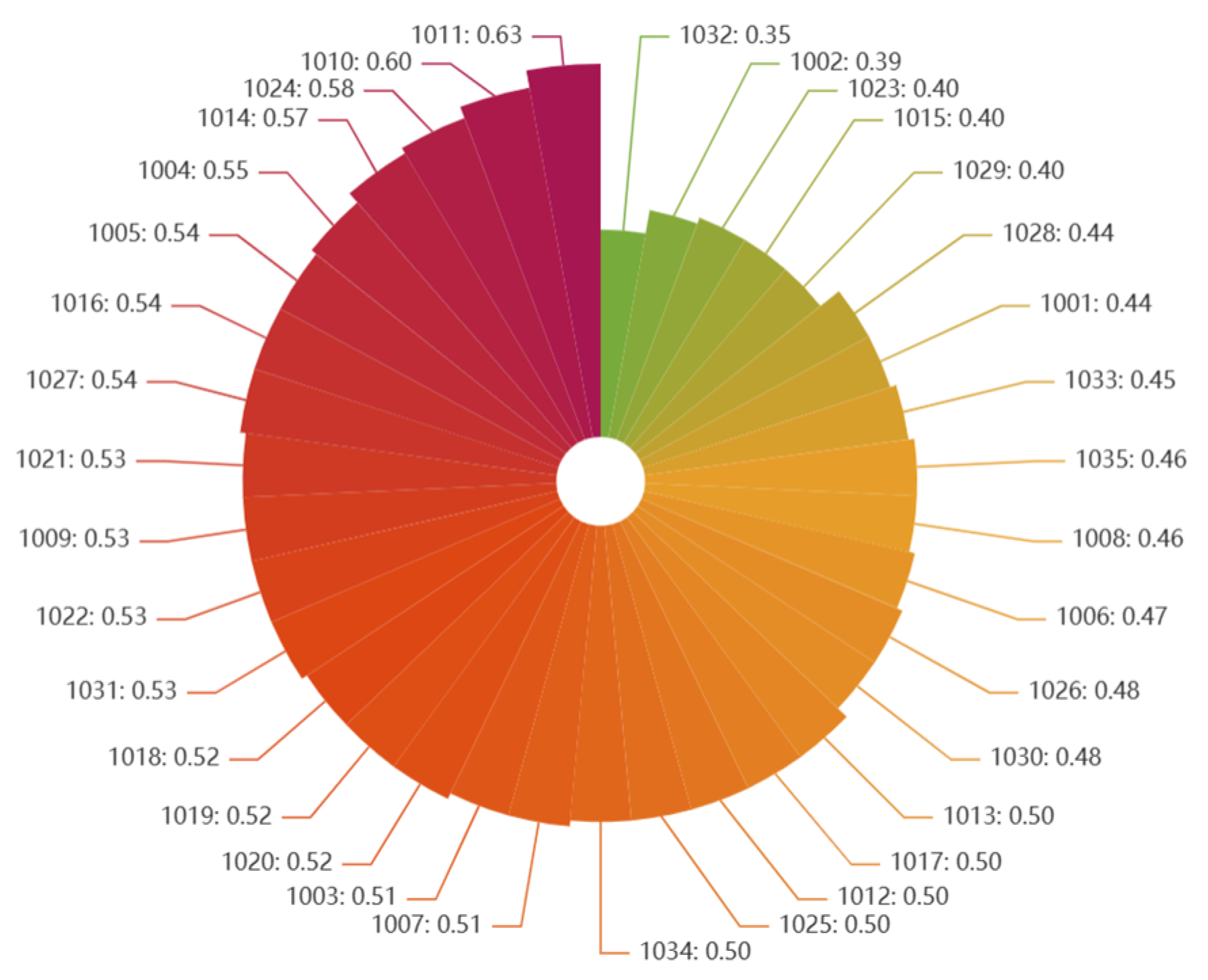

Finally, the relative closeness degree of each computing power center was calculated using Equation (8). A higher relative closeness degree indicates a higher level of computing power center competitiveness, whereas a lower value indicates a lower competitiveness level. The results, sorted in descending order, are shown in

Figure 3.

5.3. Discussions

5.3.1. Overall Competitiveness Level Analysis

The competitiveness of China’s computing power centers generally follows a normal distribution with relatively small disparities. The results of the normality test are presented in

Table 4. The mean and median values are very close, and the standard deviation is 0.062, indicating that the competitiveness levels among computing power centers do not exhibit large overall differences. A skewness of −0.322 indicates a slightly higher number of computing power centers with lower competitiveness, suggesting that the infrastructure and technological capabilities of some computing power centers may lag significantly behind those in other regions. The kurtosis is 0.175, consistent with the tail characteristics of a normal distribution. Furthermore, the

p-values for the normality test results are all greater than 0.05, indicating that the competitiveness of the computing power centers approximately follows a normal distribution statistically.

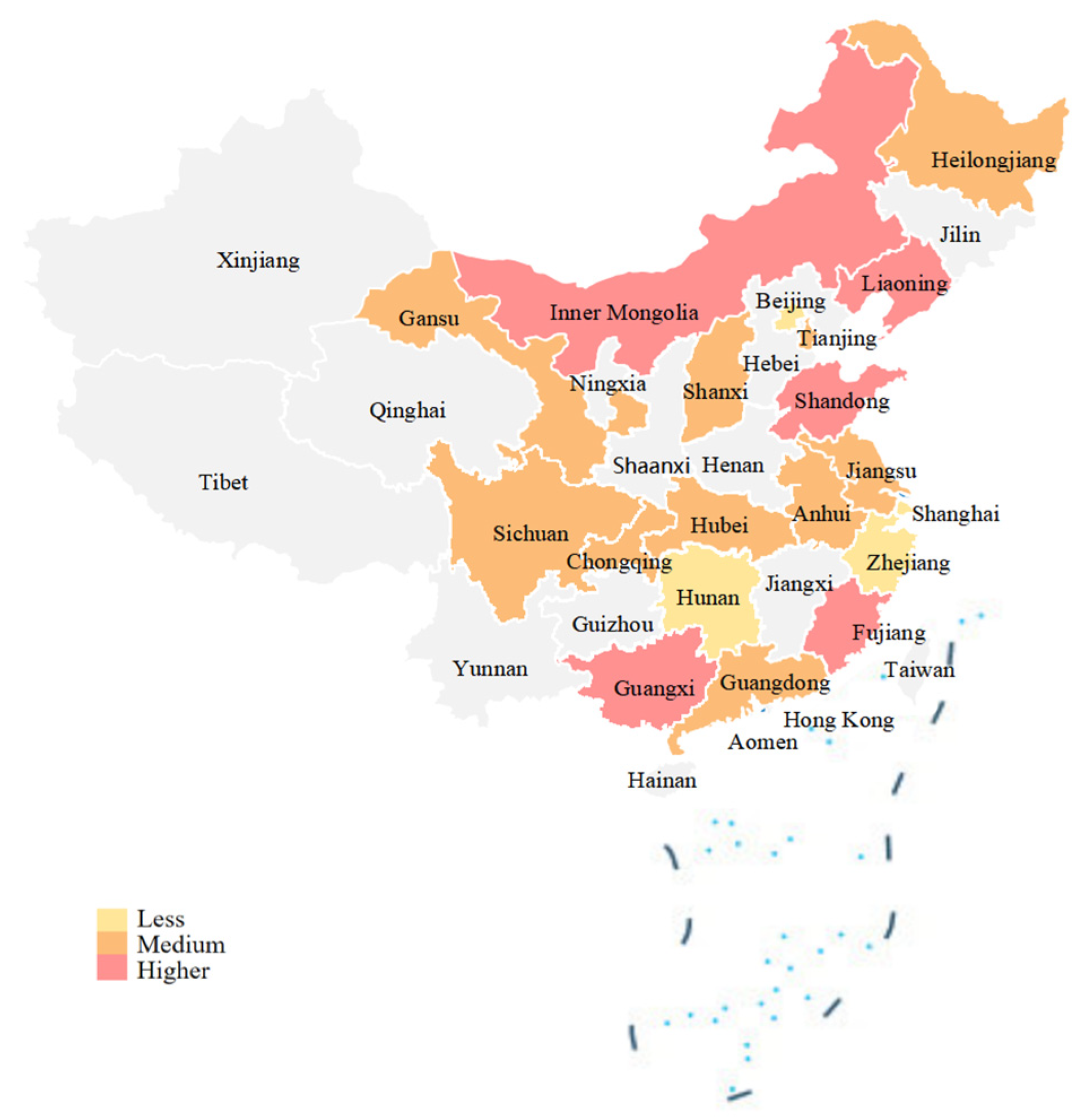

Based on the elbow method, the number of clusters was set to three. Using the K-Means algorithm, provinces were clustered according to the average competitiveness level of their computing power centers, thereby categorizing the provinces into three tiers, containing 4, 10, and 5 provinces, respectively. The one-way analysis of variance results indicate that the differences in competitiveness scores among the three tiers are highly statistically significant (F = 78.995,

p < 0.001). Post hoc least significant difference tests further confirm the existence of significant differences between all tier pairs (

p < 0.001), effectively validating the discriminant validity of the clustering results. Subsequently, a geographical distribution map of the tier levels was generated based on the clustering results to achieve spatial visualization, as shown in

Figure 4. Geographically, a pattern emerges where the competitiveness is stronger at the two ends and weaker in the middle, generally decreasing from the western and northeastern regions to the eastern and central regions. This distribution trend is closely related to the differences in key competitive resources across these regions.

5.3.2. Evaluation Indicator Weight Analysis

To accurately identify the core factors influencing the competitiveness of computing power centers, this study employs a dual-perspective analysis method: the entropy weight method is used to objectively determine the weight of each indicator, while Pearson correlation coefficients (rij) quantify the strength of association between each indicator and the final competitiveness score. This comprehensive analytical approach provides a more robust foundation for strategic decision-making.

- (1)

Infrastructure level is the core factor of computing power center competitiveness. Among the primary indicators, infrastructure level holds the highest weight of 0.3658, validating the tripartite pillar role of computing power, storage capacity and transport capability in shaping computing power center competitiveness. As shown in

Figure 5, within this dimension, the concurrent operations number possesses the highest single weight, while the floating-point operation capability exhibits the most significant positive correlation with the competitiveness score (r

11 = 0.571,

p < 0.01). This dual evidence indicates that enhancing computing power is the most direct and effective strategy for boosting competitiveness. Particularly in the context of increasing multi-task concurrent processing and complex computational demands, computing power directly determines service quality and user satisfaction, thereby expanding the market share of computing power centers. In contrast, although the network egress bandwidth carries a considerable weight, its correlation with competitiveness is not significant. This suggests that once a certain bandwidth threshold is met, its marginal contribution to perceived competitiveness may diminish, and the focus should shift more towards core computing metrics such as network latency.

- (2)

External resource environment significantly influences computing power center competitiveness. Among the criteria levels, the external resource environment carries a weight of 0.2742, within which the shelf rate emerges as a key performance driver. It not only possesses a high weight but also exhibits a strong positive correlation with competitiveness (w42 = 0.0771, r42 = 0.480, p < 0.01). The shelf rate reflects the resource utilization efficiency and market-oriented performance of a computing power center; a higher shelf rate signifies the center’s ability to maximize the deployment of computing resources. This underscores the fact that superior infrastructure and cost advantages must ultimately be translated into high resource utilization rates and market performance to realize competitive potential. Consequently, computing power centers should prioritize enhancing the shelf rate and strengthen operational management to reduce idle computing resources, thereby consolidating their competitive advantage in the intensely competitive market.

- (3)

Operational cost structure is a key element of computing power center competitiveness. With a weight of 0.2281, it indicates that to cope with intense market competition, computing power centers must not only maintain advantages in infrastructure but also effectively control operating costs. Correlation analysis powerfully quantifies this pressure: both the wage level and electricity price are among the indicators with the strongest negative correlations (r23 = −0.493, p < 0.01; r21 = −0.483, p < 0.01), which aligns with their high weights as negative indicators. This provides data-driven proof that regions with lower labor and energy costs possess an inherent competitive advantage. This also necessitates that computing power centers strike a reasonable balance between labor costs and talent acquisition needs. While ensuring talent quality, they must avoid excessively high labor costs resulting from the indiscriminate recruitment of high-level talent, which could conversely diminish overall competitiveness. Furthermore, computing power centers must actively explore energy-saving technologies and introduce green energy. By reducing electricity costs, they can maintain competitiveness at the cost structure level.

- (4)

Technological innovation capability serves as the fundamental guarantee for the development potential of computing power centers. Although technological innovation capability, with a weight of 0.1319, influences the competitive level of computing power centers, it has not yet become a key competitive factor. Among these, the number of patent applications ranks third in weight among all secondary indicators and shows a significant positive correlation with competitiveness (w32 = 0.0822, r32 = 0.344, p < 0.05). This stands in stark contrast to R&D investment, which shows no significant correlation (r31 = 0.036). This clear divergence indicates that it is not the input of R&D funds, but rather the efficiency and output of the innovation process that are directly associated with competitiveness. This insight urges managers to shift their focus from the scale of R&D to the productivity of R&D activities. From a long-term perspective, as market competition intensifies, the importance of innovation and technological capability will gradually increase, becoming a crucial guarantee for the sustainable development of computing power centConfirm.ers and a driving force for their long-term growth.

5.3.3. Competitiveness Improvement Path Analysis

Although the overall competitiveness gap is small, there are significant differences in resource endowment and competitive advantages among individual computing power centers. By calculating the difference between the standardized technological innovation capability score and the standardized operational cost structure score, the competitive advantages of computing power centers are categorized into two major types. A center is classified as the technology-advantaged type when the difference is greater than 0, and as the cost-advantaged type when the difference is less than 0.

The cost-advantaged type of computing power center, represented by the third-ranked center No. 1024, captures market share by attracting price-sensitive users with its lower costs. Results from inter-group difference analysis indicate that this type significantly outperforms the technology-advantaged type in cost-related indicators. It not only exhibits lower electricity prices (

t-test,

p = 0.016) and wage levels (Mann–Whitney U test,

p = 0.002) but also benefits from lower annual average temperatures (

t-test,

p = 0.001) and lower PUE values (Mann–Whitney U test,

p = 0.034). The core competitiveness of this type lies primarily in its resource advantages, such as a cost-effective talent pool and low electricity prices, which significantly enhance corporate capital turnover efficiency and consequently form a robust competitive capacity. Considerable variation in the shape of the radar charts for this type of computing power center is observed, as shown in

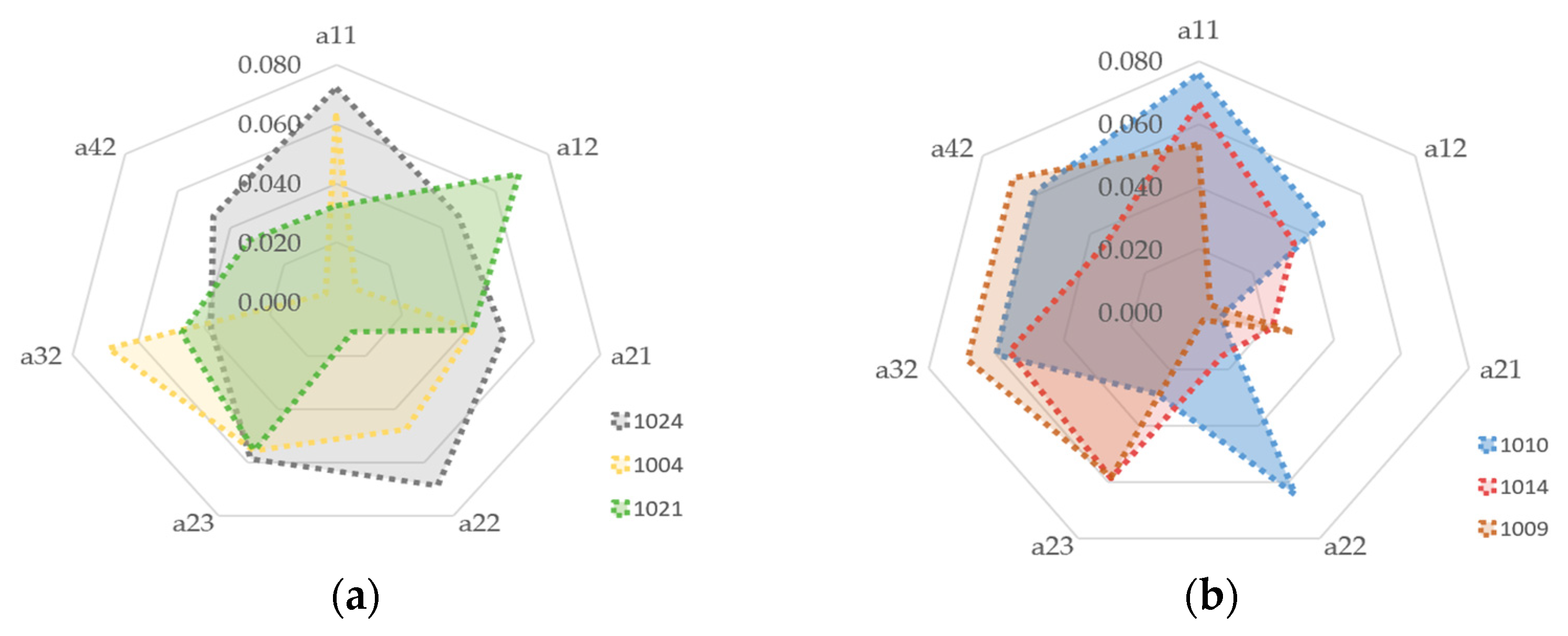

Figure 6. Center No. 1021 successfully offsets the negative impact of its high PUE level by improving its shelf rate. However, center No. 1004, located in a remote area, experiences a significantly depressed shelf rate due to influences from its geographical location and regional total demand volume. This disadvantage results in its competitiveness being lower than that of other centers of the same type and imposes constraints on its long-term development potential.

The technology-advantaged type of computing power center, represented by the second-ranked center No. 1010, robustly captures market share by providing high-quality services that fully meet user operational and experiential requirements. The results of inter-group difference analysis show no significant difference in floating-point operation capability between the two types of centers. The technology-advantaged type relies primarily on its superior technological transformation capability (i.e., the number of patent applications, Mann–Whitney U test, p = 0.011) and business carrying performance (i.e., the concurrent operations number, Mann–Whitney U test, p = 0.047). This indicates that the differentiation in competitiveness has shifted from the basic availability of computing power to a higher-dimensional competition focused on efficiency and user experience. The radar charts of this type of computing power center exhibit similar shapes, as their competitive advantages stem mainly from technological accumulation and capability, enabling them to deliver high-performance, high-stability premium services. This approach establishes dynamic barriers in core technologies, while continuously enhancing service experience and user stickiness through persistent technological iteration.

In the highly competitive market, the most competitive computing power center, No. 1011, demonstrates the synergistic effect of a dual-driver model. It not only possesses top-tier technological innovation capability but also secures a significant cost advantage through access to low-cost electricity and labor resources, thereby maintaining its leading position in the industry. This indicates that formulating a development strategy for a computing power center necessitates the integrated consideration of both technological capability and cost control. Centers must then flexibly adjust their competitive strategies based on their specific resource endowment to achieve sustainable development.

6. Conclusions

Grounded in complex systems theory, this research establishes a comprehensive analytical framework to elucidate the formation mechanism, evaluation methodology, and development pathways of computing power center competitiveness. The proposed methodology, built on transferable indicators and a generic model, offers a replicable and scalable tool for global applicability. The key conclusions are as follows:

First, in terms of the formation mechanism, the competitiveness of computing power centers is the result of a dynamic and nonlinear interaction and collaborative coupling between internal driving forces (including infrastructure, capital investment, and technological accumulation) and external traction forces (including supply chain partners, user groups, market competitors, and government). This complex system perspective offers a more comprehensive and realistic understanding than traditional fragmented analysis.

Second, in terms of evaluation methodology, the entropy weight-TOPSIS-gray correlation model developed in this study serves as a robust, objective, and readily applicable assessment tool for measuring the relative competitiveness of individual computing power centers.

Third, the empirical results reveal a hierarchical distribution of the importance of core factors influencing competitiveness: Infrastructure level is the decisive factor for competitiveness, among which floating-point operation capability and concurrent operations number constitute the most influential individual drivers. Operational cost structure and external resource environment play a pivotal role in sustaining competitive advantages, where elements such as electricity price, wage level, and utilization rate not only carry significant weight in evaluation but also demonstrate statistically significant correlations with competitiveness. In terms of technological innovation capability, competitiveness hinges critically on the efficiency and output of the innovation process rather than merely the scale of input.

Fourth, the study uncovers the dynamic evolutionary path for building computing power center competitiveness. In the initial stages of development, computing power centers can enter the market by choosing either a technology-advantaged path, which relies on cutting-edge technology and high-quality services to succeed, or a cost-advantaged path, which competes based on low-cost energy and labor, depending on their resource endowment. Influenced by technology diffusion or fluctuations in factor prices, computing power centers must evolve towards the synergy of multiple competitive advantages to achieve sustainable leading positions.

7. Countermeasures

Optimizing computing power infrastructure serves as the core driver for the development of the digital economy. Enhancing the supply capacity of the computing power industry, unleashing the application potential of computing power technologies, and facilitating the establishment of a new pattern for computing power development must proceed from the current development status of computing power centers and the key elements for enhancing their competitiveness. Based on the empirical findings, this study proposes four targeted and actionable countermeasures centered on the dual-wheel drive of technology and cost, and focusing on the key influencing factors of competitiveness. These recommendations outline potential development pathways for computing power centers; however, their effectiveness requires verification through more in-depth and detailed analysis to refine the solutions and assess their feasibility.

- (1)

Strengthen technological advantages to build core competitiveness. As a technology-intensive industry, the technological capability of computing power centers is key to improving individual efficiency and seizing the high ground in the international market.

First, prioritize enhancing computing capability as the lead, appropriately deploying infrastructure ahead of demand, and increasing the energy level of basic computing power facilities. Individual computing power centers should prioritize investment in high-performance computing nodes and heterogeneous computing resources, and optimize task scheduling systems to handle high-concurrency scenarios with multiple users and tasks, thereby improving service response quality and market attractiveness. A key focus should be placed on constructing high-speed, lossless network architectures, increasing investment in network egress bandwidth, and deploying technologies such as Remote Direct Memory Access (RDMA) and smart network interface cards to reduce network latency and ensure efficient data flow, thereby solidifying the synergistic foundation of computing power, storage capacity, and transport capability.

Second, focus on enhancing R&D and innovation capability. The competitiveness of a computing power center is reflected not only in its static technological level but also, more importantly, in its capacity for technology tracking, iterative upgrading, and foresight regarding future technology roads. Computing power centers should establish dedicated programs for tackling key technologies, focusing on disruptive algorithmic fields such as brain-inspired neural networks and prioritizing R&D directions including hardware-software co-design, energy efficiency optimization, and autonomous controllable computing power systems. This aims to achieve higher task concurrency and faster transmission speeds under equivalent computing power conditions, thereby establishing technological barriers.

- (2)

Optimize the cost structure to solidify the foundation for sustainable operation. The speed, sustainability, and effectiveness of capital turnover directly impact the development pace and market position of computing power centers.

First, systematically reduce electricity costs and unleash the potential of green computing power. Against the backdrop of the energy crisis, the energy efficiency and proportion of green electricity directly determine the quality of the cost structure for computing power centers as high-energy-consumption entities. Building upon the comprehensive deployment of high-efficiency cooling systems, such as liquid cooling and waste heat recovery, to continuously optimize PUE, it is essential to establish integrated green computing power industrial parks that combine green electricity, energy storage, and computing power. These parks should ensure that 70% of the electricity consumed originates from renewable sources within the park, while the remaining 30% is sourced as low-cost power through long-term supply agreements. This approach guarantees a continuous and stable power supply while effectively reducing the electricity consumption and cost per unit of computing power. Concurrently, AI-powered energy management systems should be introduced to utilize artificial intelligence for load forecasting and energy consumption regulation, achieving on-demand power supply and dynamic frequency adjustment, thereby enhancing energy use efficiency.

Second, precisely control labor costs. Computing power centers urgently need to establish a personnel efficiency evaluation mechanism and set thresholds for the input-output ratio of labor costs. They should rationally configure the proportion of senior, mid-level, and junior technical staff to avoid cost overruns caused by indiscriminate high-salary talent recruitment. Concurrently, promote operational automation and intelligence by implementing AI-driven automation for partial operational tasks, thereby reducing reliance on high-frequency manual operations.

Third, fully enhance resource utilization. Implement refined operations and flexible pricing strategies by constructing an elastic resource scheduling mechanism based on load forecasting. Introduce time-of-use and tiered pricing models to attract users during off-peak hours, thereby increasing the overall shelf rate. Furthermore, expand the market targeting small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and research users by launching lightweight computing power packages tailored to small and medium-scale demands. This will improve cabinet utilization rates and resource turnover efficiency.

- (3)

Governments should implement targeted policies to promote coordinated development across regions. Implementing differentiated regional computing power policies for targeted resource allocation is central to fostering high-quality development in the computing power industry.

First, in regions with cost advantages, introduce advanced renewable energy technologies and implement flexibly adjusted electricity subsidies based on the scale of computing power centers and local electricity prices. This consolidates their inherent advantages and prevents missing industry opportunities due to slowed growth. Simultaneously, accelerate the digital transformation of traditional industries. Deepen applications in areas such as the industrial internet, smart manufacturing, and smart agriculture to unleash local computing power demand, thereby establishing an internal absorption mechanism for computing power resources and broadening the development space.

Second, in regions with technological advantages, promote the establishment of computing power technology sharing platforms. This facilitates the transfer of capabilities from advanced computing power centers to technologically lagging units, elevating the overall regional standard and fostering a virtuous cycle within the region. Concurrently, advance the development of technology R&D, talent cultivation, and innovation platforms to enhance inter-regional technology spillover effects.

Third, in less developed regions, while increasing investment to bridge infrastructure and technological capability gaps, enhance the function of computing power conversion hubs to undertake computing power outsourcing and region-specific scenario tasks. Simultaneously, prioritize these areas in land use planning and infrastructure support to reduce initial investment pressure and narrow the development gap.

- (4)

Foster industrial ecosystem synergy to build a collaborative development system. Constructing an efficient, interconnected industrial ecosystem encompassing computing power centers, data service providers, equipment manufacturers, and universities is crucial for achieving a virtuous cycle of resource sharing, technological collaboration, and market linkage.

First, promote power-computing synergy. Governments should take the lead in facilitating long-term green power cooperation agreements between computing power centers, grid companies, and new energy enterprises. Establish a linkage mechanism between computing load and green power consumption to achieve dual empowerment through low-carbon operations and low costs. Furthermore, create an interconnected computing power scheduling platform that uses electricity prices to guide computing power demand allocation.

Second, facilitate computing-application synergy to boost the shelf rate of computing power centers. On the one hand, leverage the strengths of the industrial chain. Through close collaboration with upstream and downstream partners, deepen the exploration of industry application scenarios to enhance the market adaptability and application value of computing power technologies. On the other hand, address the weaknesses of the industrial chain. Implement market-oriented industrial policies to drive industry digital transformation, and establish regional computing power service consortia to jointly secure cross-regional computing power orders. This helps mitigate geographical disadvantages while enhancing market bargaining power and resource integration capabilities.