The Economic Evaluation of Cultural Ecosystem Services: The Case of Recreational Activities on the “Via degli Dei Pilgrim Route” (Italy)

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review—Valuation of Cultural Ecosystem Services, Visitor Profiling and Methods

1.2. Research Objectives

- Derive empirically supported visitor typologies.

- 2.

- Translate typologies into monetary and operational CES flows.

- 3.

- Produce cluster-specific governance recommendations and scenario assessments.

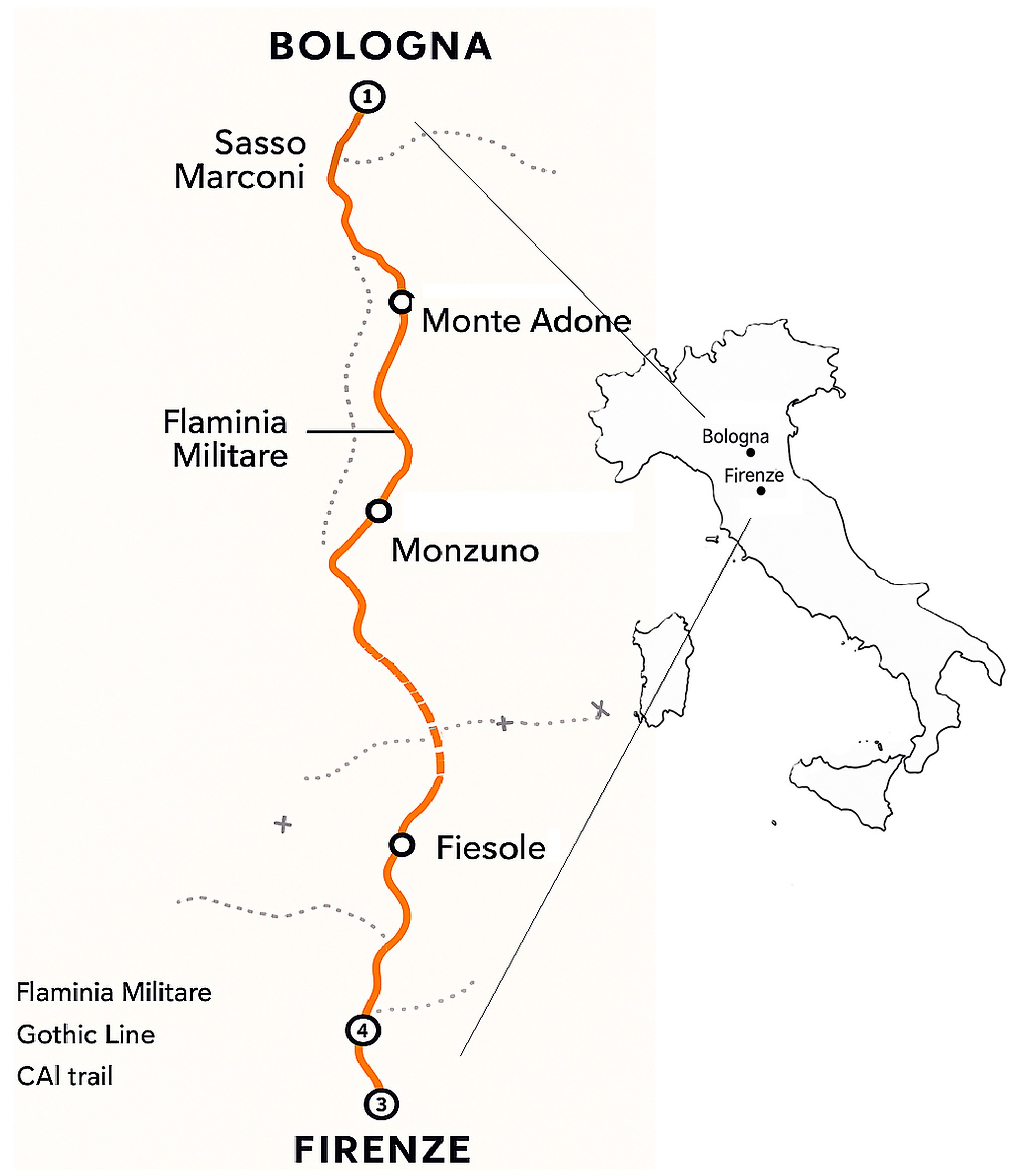

1.3. Study Area

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Hypotheses and Analytical Framework

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Variables

- -

- Socio-demographics: gender, age class, education, country of residence.

- -

- Trip organisation: travel period, accommodation type, means of transport, daily and total expenditure.

- -

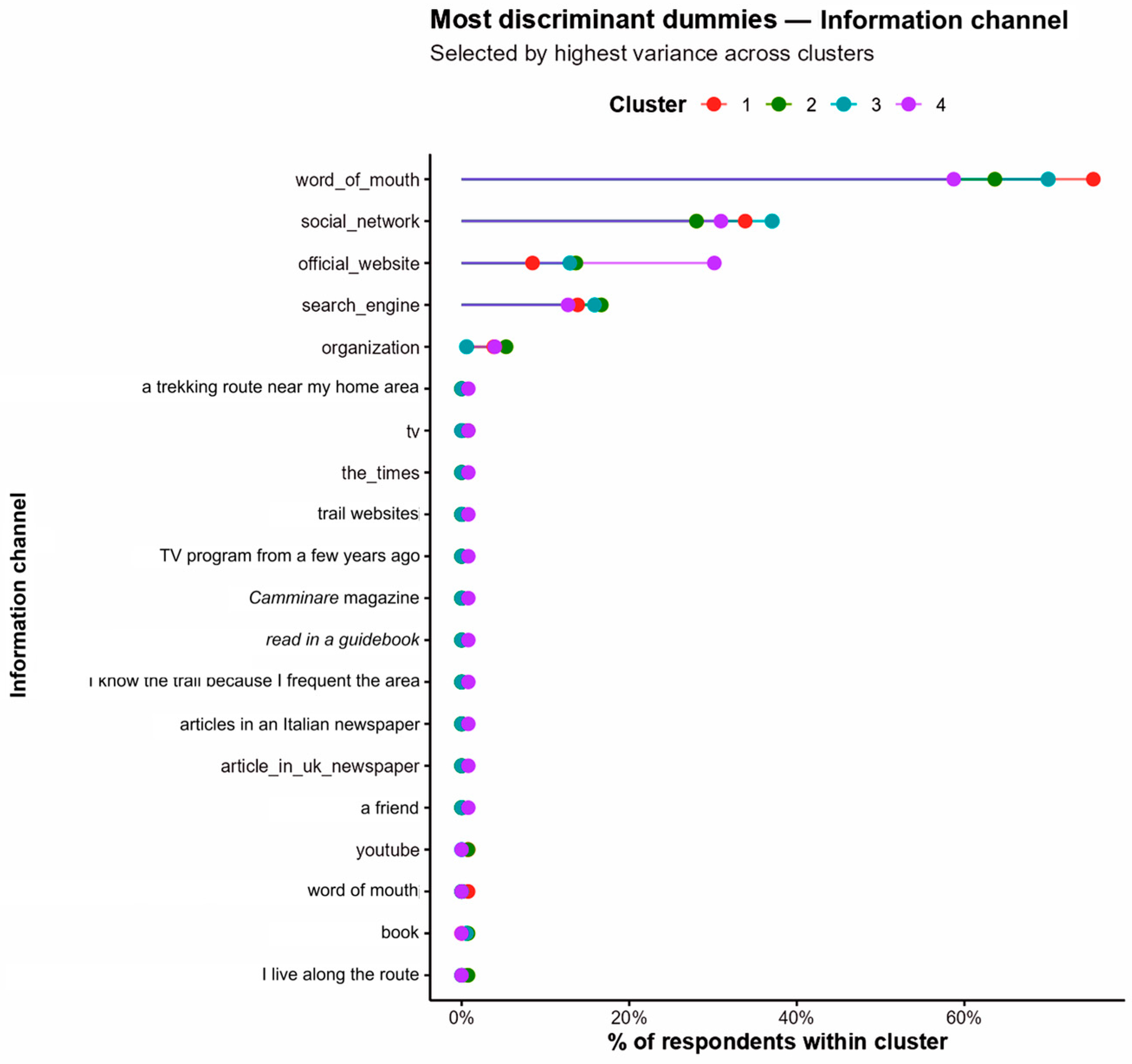

- Behavioural and motivational dimensions: travel motivation, information sources and communication channels, travel companions.

2.4. Dissimilarity Measure

2.5. Clustering Procedure

2.6. Selection of the Number of Clusters: The Silhouette Method

2.7. Dimensionality Reduction and Visualisation

2.8. Cluster Characterisation

3. Results

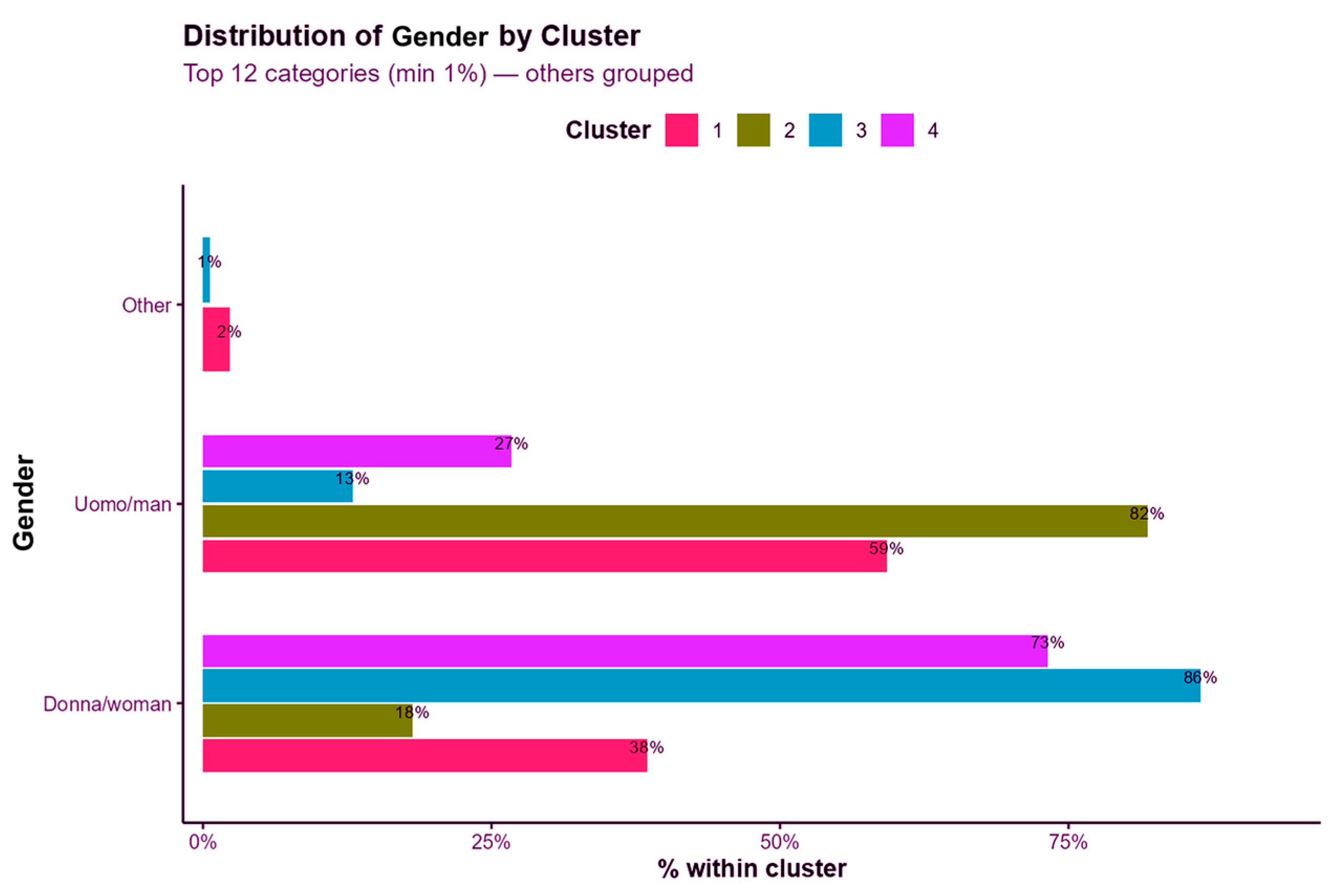

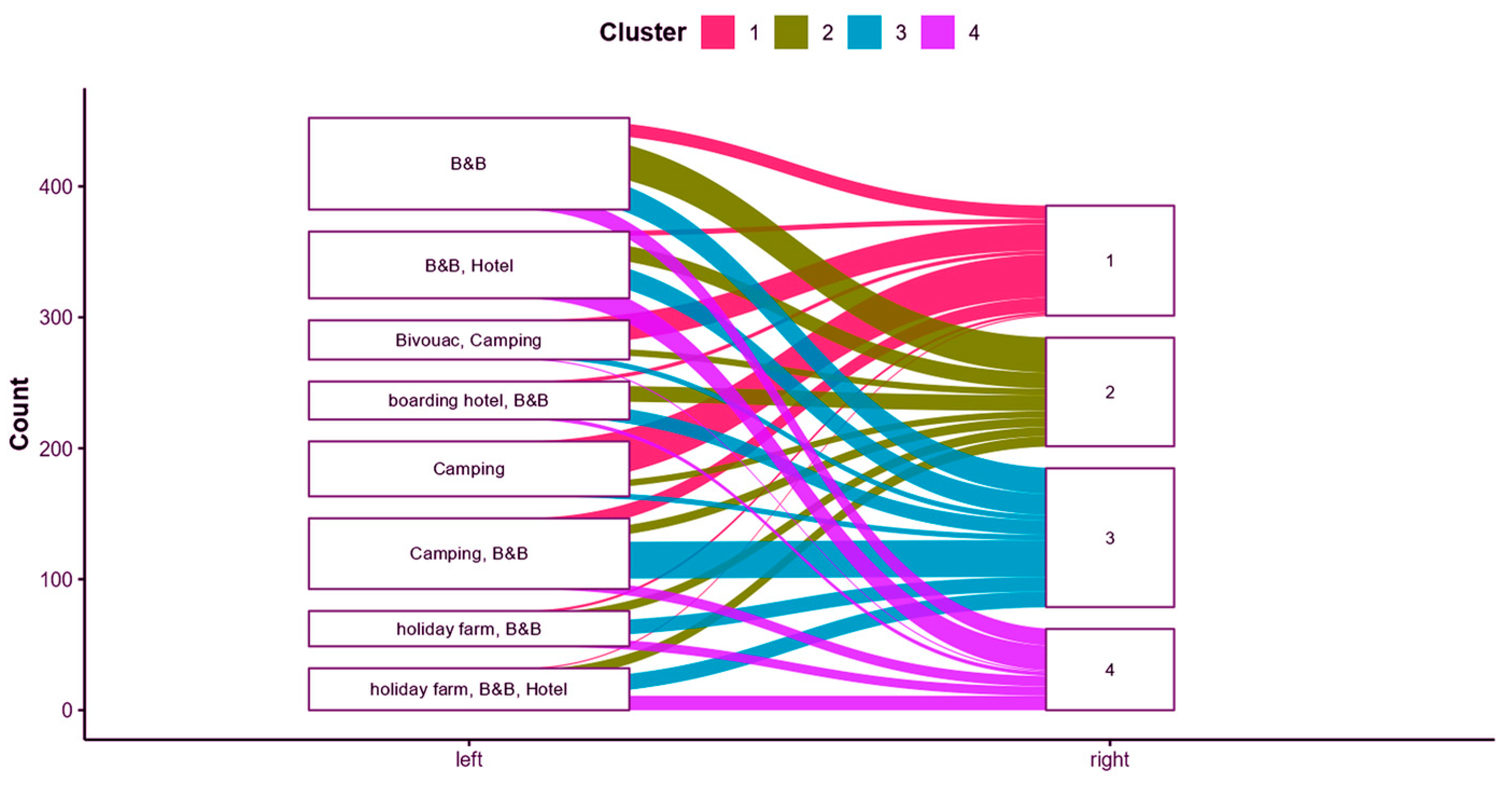

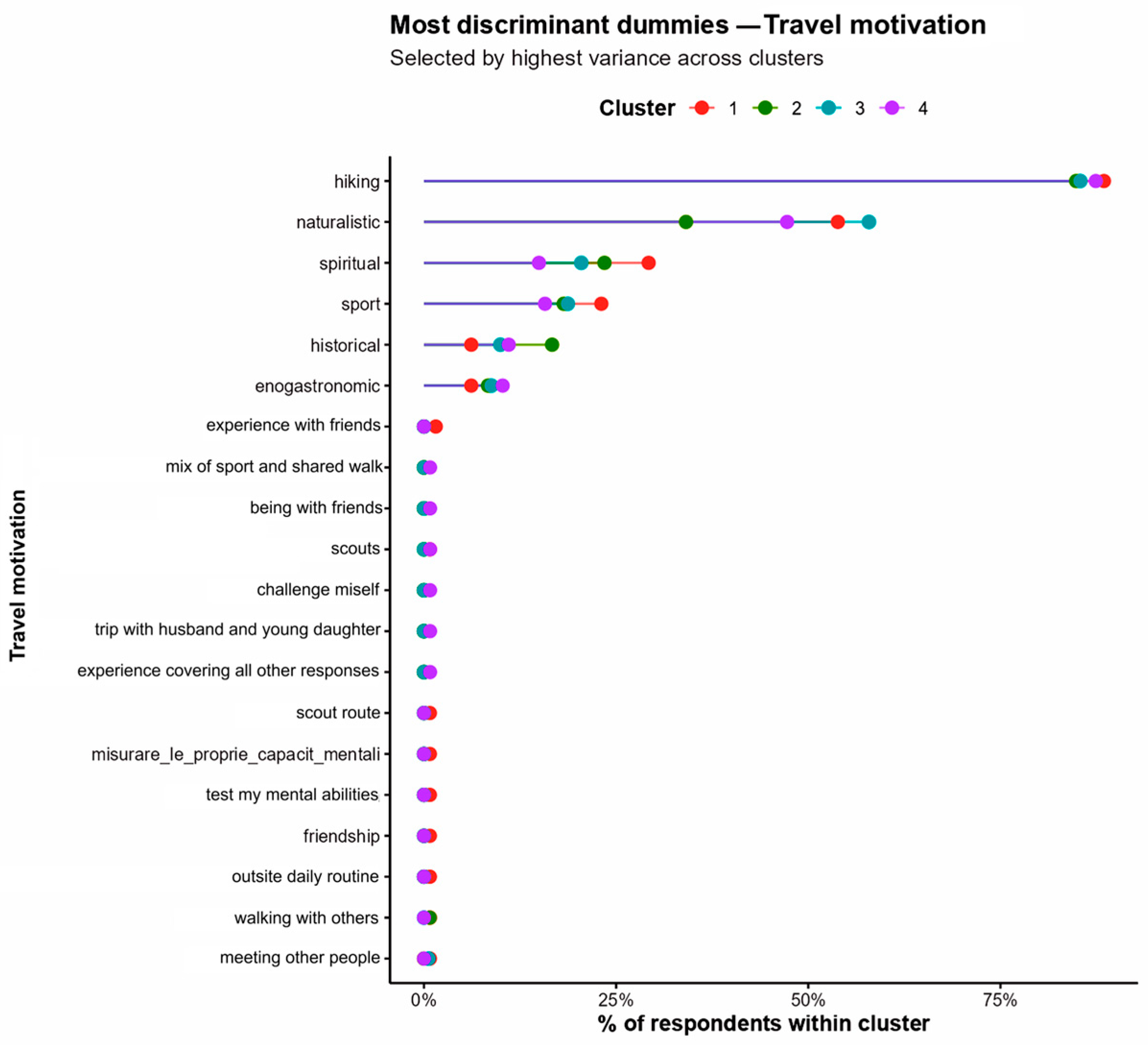

3.1. Cluster Characterisation for Hikers on the Via degli Dei Pilgrim Route

3.2. Expenditure Patterns Across Clusters

4. Discussion

- Midlife Comfort-Seekers (shoulder season): bundle B&B + restaurant menus and luggage transfer; 5–6-day midweek departures in May/September; themed products (foliage/history) with certified local guides; channels: official website and targeted campaigns to 45–64 cohorts; incentives: early-booking and weekday discounts.

- Student Campers (peak management): expand low-impact camping/bivouac capacity; pre-bookable plots to smooth peaks; shuttle links to trailheads; nudges on Leave-No-Trace and quiet hours.

- Young Women on Mixed Lodging: highlight safety, well-signed sections, small-group options; mixed lodging passes (B&B + one campground night); storytelling on heritage/nature.

- Working-Age Male B&B Hikers: shoulder-season ‘trail-to-table’ packages (B&B + local dinners), micro-events, and last-minute weekday offers.

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (Program). Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Synthesis; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; ISBN 1597260401. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, T.C.; Muhar, A.; Arnberger, A.; Aznar, O.; Boyd, J.W.; Chan, K.M.A.; Costanza, R.; Elmqvist, T.; Flint, C.G.; Gobster, P.H.; et al. Contributions of Cultural Services to the Ecosystem Services Agenda. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 8812–8819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardoin, N.M.; Gould, R.K.; Lukacs, H.; Sponarski, C.C.; Schuh, J.S. Scale and Sense of Place among Urban Dwellers. Ecosphere 2019, 10, e02871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.M.A.; Guerry, A.D.; Balvanera, P.; Klain, S.; Satterfield, T.; Basurto, X.; Bostrom, A.; Chuenpagdee, R.; Gould, R.; Hannahs, N.; et al. Where Are ‘Cultural’ and ‘Social’ in Ecosystem Services? A Framework for Constructive Engagement. Bioscience 2012, 62, 744–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milcu, A.I.; Hanspach, J.; Abson, D.; Fischer, J. Cultural Ecosystem Services: A Literature Review and Prospects for Future Research. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plieninger, T.; Dijks, S.; Oteros-Rozas, E.; Bieling, C. Assessing, Mapping, and Quantifying Cultural Ecosystem Services at Community Level. Land Use Policy 2013, 33, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhard, B.; Kroll, F.; Nedkov, S.; Müller, F. Mapping Ecosystem Service Supply, Demand and Budgets. Ecol. Indic. 2012, 21, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, J.; Egoh, B.; Willemen, L.; Liquete, C.; Vihervaara, P.; Schägner, J.P.; Grizzetti, B.; Drakou, E.G.; La Notte, A.; Zulian, G.; et al. Mapping Ecosystem Services for Policy Support and Decision Making in the European Union. Ecosyst. Serv. 2012, 1, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tew, E.R.; Simmons, B.I.; Sutherland, W.J. Quantifying Cultural Ecosystem Services: Disentangling the Effects of Management from Landscape Features. People Nat. 2019, 1, 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Morcillo, M.; Plieninger, T.; Bieling, C. An Empirical Review of Cultural Ecosystem Service Indicators. Ecol. Indic. 2013, 29, 434–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickerson, N.P.; Jorgenson, J.; Boley, B.B. Are Sustainable Tourists a Higher Spending Market? Tour. Manag. 2016, 54, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Baggethun, E.; de Groot, R.; Lomas, P.L.; Montes, C. The History of Ecosystem Services in Economic Theory and Practice: From Early Notions to Markets and Payment Schemes. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 1209–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenter, J.O.; Bryce, R.; Christie, M.; Cooper, N.; Hockley, N.; Irvine, K.N.; Fazey, I.; O’brien, L.; Orchard-Webb, J.; Ravenscroft, N.; et al. Shared Values and Deliberative Valuation: Future Directions. Ecosyst. Serv. 2016, 21, 358–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanazzi, G.R.; Koto, R.; De Boni, A.; Ottomano Palmisano, G.; Cioffi, M.; Roma, R. Cultural Ecosystem Services: A Review of Methods and Tools for Economic Evaluation. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2023, 20, 100304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercadé-Melé, P.; Barreal Pernas, J. Study of Expenditure and Stay in the Segmentation of the International Tourist with Religious Motivation in Galicia. Rev. Galega De Econ. 2021, 30, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvache-Franco, M.; Regalado-Pezúa, O.; Carvache-Franco, O.; Carvache-Franco, W. Segmentation by Motivations in Religious Tourism: A Study of the Christ of Miracles Pilgrimage, Peru. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0303762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomatis, F.; Lozano-Castellanos, L.F.; García-Navarrete, O.L.; Correa-Guimaraes, A.; Wilhelm, M.S.; Boukharta, O.F.; Murcia Velasco, D.A.; Méndez-Vanegas, J.E. Evaluation of Urban Sustainability in Cities of The French Way of Saint James (Camino de Santiago Francés) in Castilla y León According to The Spanish Urban Agenda. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- den Breejen, L. The Experiences of Long-Distance Walking: A Case Study of the West Highland Way in Scotland. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 1417–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, S. A Review of Data-Driven Market Segmentation in Tourism. Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gower, J.C. A General Coefficient of Similarity and Some of Its Properties. Biometrics 1971, 27, 857–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, L.; Rousseeuw, P.J. Finding Groups in Data: An Introduction to Cluster Analysis; John Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1990; ISBN 0-471-87876-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lê, S.; Josse, J.; Husson, F. FactoMineR: An R Package for Multivariate Analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 2008, 25, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Déniz, E.; Dávila-Cárdenes, N. Modelling the Heterogeneity of Tourist Spending in a Mature Destination: An Approach through Infinite Mixture. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iniesta-Arandia, I.; García-Llorente, M.; Aguilera, P.A.; Montes, C.; Martín-López, B. Socio-Cultural Valuation of Ecosystem Services: Uncovering Links between Values, Drivers and Wellbeing. Ecol. Econ. 2014, 108, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, K.F.; Lawson, R. The Nature of Independent Travel. J. Travel. Res. 2003, 42, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarinen, J. Critical Sustainability: Setting the Limits to Growth and Responsibility in Tourism. Sustainability 2014, 6, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagarazzi, C.; Sergiacomi, C.; Stefanini, F.M.; Marone, E. A Model for the Economic Evaluation of Cultural Ecosystem Services: The Recreational Hunting Function in the Agroforestry Territories of Tuscany (Italy). Sustainability 2021, 13, 11229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czúcz, B.; Arany, I.; Potschin-Young, M.; Bereczki, K.; Kertész, M.; Kiss, M.; Aszalós, R.; Haines-Young, R. Where Concepts Meet the Real World: Systematic Review of Ecosystem Service Indicators and Classification Using CICES. Ecosyst. Serv. 2018, 29, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomo, I.; Felipe-Lucia, M.R.; Bennett, E.M.; Martín-López, B.; Pascual, U. Disentangling the Pathways and Effects of Ecosystem Service Co-Production. Adv. Ecol. Res. 2016, 54, 245–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-López, B.; Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Lomas, P.L.; Montes, C. Effects of Spatial and Temporal Scales on Cultural Services Valuation. J. Env. Manag. 2009, 90, 1050–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Benedictis, L.; Licio, V.; Pinna, A. From the Historical Roman Road Network to Modern Infrastructure in Italy. J. Reg. Sci. 2023, 63, 1162–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostini, C.; Santi, F. La Strada Flaminia Militare Del 187 a. C.: Tutto Il Percorso Bologna-Arezzo; Nuove Ricerche e Rinvenimenti; Grafis: Viersen, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Appennino Slow. Via degli Dei—Annual Report 2022 (Consortium Report, 2023). Available online: https://www.appenninoslow.it (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Struyf, A.; Hubert, M.; Rousseeuw, P.J. Clustering in an Object-Oriented Environment. J. Stat. Softw. 1996, 1, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseeuw, P.J. Silhouettes: A Graphical Aid to the Interpretation and Validation of Cluster Analysis. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 1987, 20, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig, C. Cluster-Wise Assessment of Cluster Stability. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2007, 52, 258–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagès, J. REVUE DE STATISTIQUE APPLIQUÉE Analyse Factorielle de Données Mixtes Article Numérisé Dans Le Cadre Du Programme Numérisation de Documents Anciens Mathématiques. Rev. Stat. Appl. 2004, 52, 93–111. [Google Scholar]

- Everitt, B.S.; Landau, S.; Leese, M.; Stahl, D. Cluster Analysis, 5th ed.; Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics; Balding, D.J., Cressie, N.A.C., Fitzmaurice, G.M., Johnstone, I.M., Molenberghs, G., Scott, D.W., Smith, A.F.M., Tsay, R.S., Weisberg, S., Eds.; Jon Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-0-470-74991-3. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M. Constructing Sustainable Tourism Development: The 2030 Agenda and the Managerial Ecology of Sustainable Tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1044–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, C. The West Highland Way—A Strategic Review of Management and Maintenance; Slater Business Services: Stirling, Scotland, 2017.

- Guiver, J.; Lumsdon, L.; Weston, R. Traffic Reduction at Visitor Attractions: The Case of Hadrian’s Wall. J. Transp. Geogr. 2008, 16, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cluster | Expenses | Mean | Median | p25 | p75 | tmean10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Accommodation | 89.77 | 75.00 | 50.00 | 125.00 | 84.90 |

| 2 | 125.62 | 125.00 | 75.00 | 200.00 | 127.81 | |

| 3 | 137.99 | 125.00 | 100.00 | 200.00 | 139.56 | |

| 4 | 161.14 | 180.00 | 125.00 | 200.00 | 165.91 | |

| 1 | Other * | 14.92 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 25.00 | 11.30 |

| 2 | 19.81 | 25.00 | 0.00 | 25.00 | 15.14 | |

| 3 | 26.23 | 25.00 | 0.00 | 25.00 | 17.52 | |

| 4 | 28.29 | 25.00 | 0.00 | 25.00 | 18.38 | |

| 1 | Travel | 60.05 | 33.00 | 30.00 | 80.00 | 51.49 |

| 2 | 65.70 | 50.00 | 30.00 | 90.00 | 57.90 | |

| 3 | 73.59 | 60.00 | 33.00 | 105.00 | 65.74 | |

| 4 | 88.01 | 80.00 | 40.00 | 120.00 | 78.32 | |

| 1 | Food | 93.27 | 75.00 | 30.00 | 125.00 | 79.42 |

| 2 | 132.71 | 125.00 | 75.00 | 175.00 | 126.05 | |

| 3 | 140.18 | 125.00 | 75.00 | 175.00 | 134.30 | |

| 4 | 160.77 | 175.00 | 125.00 | 225.00 | 159.75 |

| Cluster | Expenses | Mean | Median | p25 | p75 | tmean10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Accommodation | 34.8% | 34.8% | 25.0% | 46.9% | 35.4% |

| 2 | 36.6% | 36.2% | 28.1% | 45.5% | 36.5% | |

| 3 | 37.9% | 37.1% | 29.4% | 47.0% | 37.9% | |

| 4 | 38.7% | 37.6% | 30.6% | 46.5% | 38.4% | |

| 1 | Other | 5.8% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 9.8% | 4.3% |

| 2 | 5.5% | 5.1% | 0.0% | 9.1% | 4.6% | |

| 3 | 6.0% | 5.5% | 0.0% | 8.2% | 4.8% | |

| 4 | 5.8% | 4.9% | 0.0% | 7.2% | 4.3% | |

| 1 | Travel | 24.0% | 21.4% | 14.2% | 31.0% | 22.0% |

| 2 | 19.9% | 18.2% | 11.7% | 25.9% | 18.7% | |

| 3 | 19.5% | 18.0% | 11.1% | 24.7% | 18.4% | |

| 4 | 19.7% | 18.2% | 10.5% | 25.3% | 18.5% | |

| 1 | Food | 34.8% | 32.6% | 22.7% | 44.6% | 34.3% |

| 2 | 37.3% | 38.0% | 27.8% | 46.5% | 37.2% | |

| 3 | 35.9% | 36.2% | 28.2% | 44.6% | 35.8% | |

| 4 | 35.4% | 36.2% | 25.9% | 44.6% | 35.6% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bernetti, I.; Morri, A.; Fossati, M.; Ventura, T.; Fagarazzi, C. The Economic Evaluation of Cultural Ecosystem Services: The Case of Recreational Activities on the “Via degli Dei Pilgrim Route” (Italy). Sustainability 2025, 17, 10179. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210179

Bernetti I, Morri A, Fossati M, Ventura T, Fagarazzi C. The Economic Evaluation of Cultural Ecosystem Services: The Case of Recreational Activities on the “Via degli Dei Pilgrim Route” (Italy). Sustainability. 2025; 17(22):10179. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210179

Chicago/Turabian StyleBernetti, Iacopo, Anna Morri, Marta Fossati, Tommaso Ventura, and Claudio Fagarazzi. 2025. "The Economic Evaluation of Cultural Ecosystem Services: The Case of Recreational Activities on the “Via degli Dei Pilgrim Route” (Italy)" Sustainability 17, no. 22: 10179. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210179

APA StyleBernetti, I., Morri, A., Fossati, M., Ventura, T., & Fagarazzi, C. (2025). The Economic Evaluation of Cultural Ecosystem Services: The Case of Recreational Activities on the “Via degli Dei Pilgrim Route” (Italy). Sustainability, 17(22), 10179. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210179