1. Introduction

Overbank flow on the floodplain of a natural river is a repeatable process which renews some fluvial landforms (rebuilding of levees and crevasse splays) and masks other ones (i.e., filling of abandoned channels), as exemplified by the 2019 flood on the Platte River downstream from Columbus [

1]. Human pressure on rivers and their floodplains has changed this natural process into flooding, which is usually defined in hydrology as an overflow of water that causes social and economic losses [

2,

3]. These losses induce people to further train rivers in order to manage flooding by construction of different hydrotechnical structures [

4]. The simplest structures reduce the area of inundation along the river (artificial levees, dikes) or downstream from a particular location (dam), but more complicated systems are also designed to convey abnormal discharge to an area flooded intentionally such as bypass channels, floodways, detention and storage basins, and dry polders.

So far, the task of regulating water resources in river valleys has been entrusted to multifunctional retention reservoirs. The main function is usually to manage flooding, but others include the provision of drinking water, regular irrigation of the valley, production of hydroelectricity, and provision of areas for recreation and tourism. Over time, it was noticed that this solution entails excessive environmental costs including changing the river regime, permanent flooding of riverside ecosystems, disconnection of ecological corridors, and the triggering of landslides on the slopes of artificial basins. In addition, there occurs a need for the displacement of road and rail infrastructure and the loss of valuable agricultural areas.

Protecting the inhabitants of the river valley and cities is an urgent task in the face of the frequent floods and violent storms that plague Central Europe. Concerns about biodiversity and frequent social protests drive the search for solutions that align with the concept of sustainable development. Local conditions determine whether it is necessary to build a dam or protect natural wetlands as retention areas [

5].

In the United States since 2005, more dams have been removed than newly constructed [

6]. In many European countries where dams have been built, reservoirs have lost their function due to sediment deposition. In some cases, negative impacts are observed due to poorly designed reservoirs. Environmental organizations are taking increasingly active steps against the construction of new dams [

7]. There are protests and demands to dismantle existing dams. In Western Europe, a trend of dam removal rather than construction has been underway for a few years [

8,

9], and in the near future, it may spread into Central Europe [

10,

11] and Asia [

12] as well; however, the number of dams is still increasing from a global perspective [

13].

The flood on the Odra River in July 1997 caused huge material losses. An area of about 750 km

2 in the Silesian, Opole, and Lower Silesian voivodeships was flooded. A total of 37,000 buildings, 866 bridges, and over 2000 km of roads were damaged, and 60 people died [

14]. One of the main causes of these losses was insufficient flood protection. In 2001, studies began on the government’s “Programme for the Odra 2006” [

15]. As a result of these studies, the need to build a dry polder on the Odra upstream from Racibórz was indicated [

16,

17].

The analyses conducted by the authors aimed to indicate a rational management of environmental resources, which would ensure the proper exploitation of the fact that the area would be flooded during the filling of the reservoir. The technical assumptions for the dry polder project clearly linked its implementation to the documented deposits of natural aggregates within its basin. Extracting these minerals increases flood protection capacity [

18]. It was noted that the use of mineral deposits in the bowl of the Racibórz Dolny dry polder does not cause environmental damage as in the case of land deposits of natural aggregates. The biotic resources of the area within the boundaries of the Racibórz Dolny reservoir were also presented, with special attention paid to habitats and birds protected within Natura 2000 areas.

The considerations were supported by an analysis of the hydrological data (water stages and discharges) on the Odra River during the flood events of 1997, 2010, and 2024. A comparison of the flood course from these years allowed for the formulation of an assessment of the effectiveness of the Racibórz Dolny dry polder. Interdisciplinary analyses based on spatial and temporal distribution allowed for the assessment of whether the facility meets the assumptions of sustainable development.

1.1. Regional Setting

The hydrotechnical structure of the Racibórz Dolny dry polder is located in southern Poland, over 30 km from the border with Czechia (

Figure 1). It is an area of the Racibórz Basin mesoregion, which includes the Odra Valley and constitutes the southeastern part of the Silesian Lowland macroregion [

19].

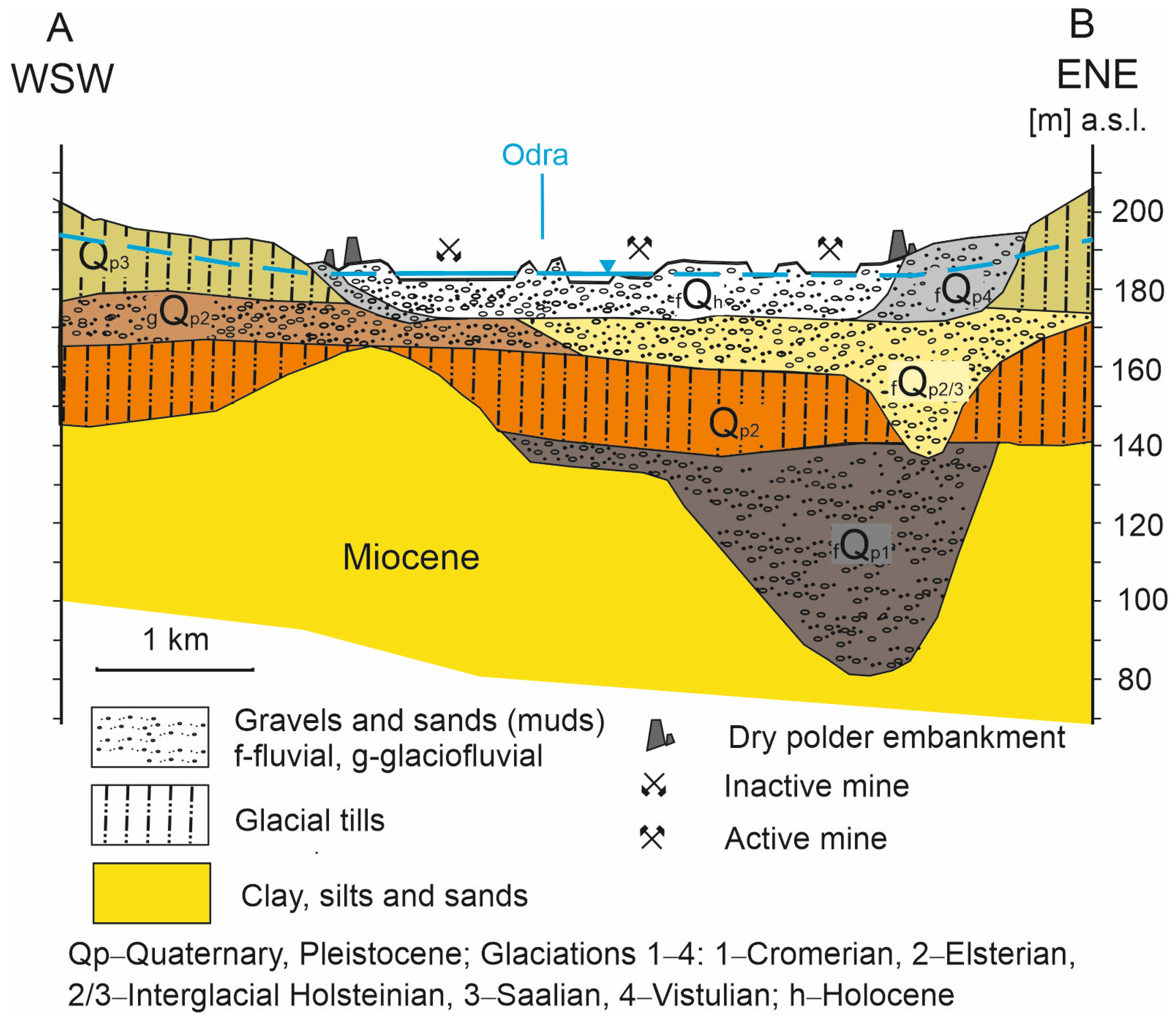

Geologically, the study area is the western part of the Carpathian Foredeep. The sedimentary base for the sediments of the foredeep are Lower Carboniferous (Visean) sediments developed in the Culm facies. The foredeep is filled with Miocene formations (Badenian and Sarmatian). The total thickness of the Miocene in the analysed area is about 600 m [

20,

21]. The Badenian formations are composed of marly clays and clays with intercalations of fine-grained sands, while the Sarmatian is composed of continental sediments in the form of clays interbedded with sands (

Figure 2). In the analysed area, the ceiling of the Miocene formations lies at a depth of 7 to 15 m below ground level [

20].

The Quaternary sediments occur in the form of two terraces: a higher one, passing into the slope of the plateau, and a lower flood terrace (

Figure 2). The higher terrace has an erosive–accumulative character, composed mainly of gravels and river sands with an interbedding of clays and silts [

19]. The Odra flood terrace is an accumulation terrace, composed of alluvial soils and river sands and gravels [

22,

23].

The Odra River is a large (on the European scale) transboundary river (

Figure 1, locator map) shared between Czechia, Poland, and Germany. Typically, the name Oder derived from German is used in English, but rather for the lower reach of the river shared between Germany and Poland. In our study, we focus on the upper section of the Odra river, which is delimitated usually down to the outlet of its right tributary, the Kłodnica River (and the associated Gliwice channel), or down to the major left tributary, the Nysa Kłodzka River, and will use the native form of the name, the Odra River, to discuss this area. In particular, we were interested in a river reach located in the physical region of the Racibórz Gate (in Polish: Brama Raciborska), [

19], which forms a relatively narrow passage (

Figure 1, main map) between two basins (wider parts of the river valley known as the Ostrava Basin and Racibórz Basin) occupied, correspondingly, by the city of Ostrava in Czechia and the city of Kędzierzyn-Koźle in Poland. In general, the area is a tectonic depression (foredeep) between the Alpine structures of the Carpathian Mountains and the Polish Upland to the east and the Bohemian Massif with the Sudetes to the west (

Figure 1, locator map). Due to the low elevation of the region, it was covered by southernmost lobes of Scandinavian ice sheets during the older glaciations in the Pleistocene (

Figure 2)—the Saalian [

24] and Elsterian [

25]—correlated with the Alpine Riss and Mindel glaciations.

The Upper Odra is an example of many river valleys in Europe which have undergone significant transformation by anthropopressure. Training of the river started in the medieval period, and by World War Two, it had effectively (i) removed fluvial landforms as sandbars and riverine islands, (ii) shortened the length of the river by cutting meanders, (iii) narrowed the active channel by groynes, and (iv) cascaded the longitudinal profile by means of a system of barrages (low dams). All these efforts impacted the hydraulic setting of the river by increasing the stream power, which in turn induced lateral erosion and incision [

26]. A unique reach which has been left untrained due to its location on the political border between Poland and Czechia (earlier Austrian Silesia and Prussia) is within the study area between the Chałupki gauge (

Figure 1) and outlet of the Olza river. This 7 km length section of the Upper Odra River remains almost freely meandering in its alluvial belt, enabling studies on the dynamics of a natural riverscape [

27]. The floodplain of the Upper Odra River was transformed even more than the channel because of extensive open pit mining.

The longitudinal profile of the Upper Odra River is 0.4‰ (40 cm per 1 km). The channel width is 60 m. A usual discharge is 60 m

3·s

−1, but in autumn this can decrease down to 20 m

3·s

−1. Discharges during flooding might be 300 times higher than the usual flow of water [

26]. Maximal discharge values are given in

Table 1.

Pluvial floods occur on the Upper Odra River regularly once every dozen or so years, especially in the summer. The studied segment of the river has the highest flood potential among the large Polish rivers as the k index varies there from 3.85 at the Chałupki gauge to 4.00 at the Krzyżanowice gauge to 3.99 at the Racibórz-Miedonia gauge—a calculation performed by [

28] using a formula proposed by [

29], which is based on the ratio of the maximal discharge and catchment area.

1.2. Dry Polder Parameters and History

The “Racibórz Dolny” reservoir is a flood control polder (

Figure 1), i.e., a dry reservoir with limited access to areas located in the basin of the facility. Deposits of sand and gravel have been documented in the basin of the “Racibórz Dolny” polder, the exploitation of which contributes to the increase in the capacity of the reservoir basin. The maximum surface of the reservoir water is approximately 2630.0 ha. It is not ruled out that the “Racibórz Dolny” polder will be a water reservoir in the future, which will also be related to the construction of the “Odra-Dunaj” Canal and the creation of a European waterway. Characteristics of the Racibórz Dolny dry polder are as follows [

18]:

Area 26.26 km2;

Reservoir capacity 185 million m3;

Embankment crown level 197.50 m a.s.l.;

Max. water level 195.20 m a.s.l.;

Max. height of dams 10.5 m;

Width of dam crown 6 m;

Length of embankments 22.68 km, including:

Frontal 4.0 km;

Left bank 9.53 km;

Right bank 9.15 km.

The structure of the dam body comprises a hydrotechnical embankment made of local cohesive rocks, with prism drainage from the air side, draining water from the drainage to the ditch at the base of the slope. The project assumptions include the possibility of exploiting natural aggregate deposits from the reservoir basin, which will affect the achievement of its target flood capacity [

22].

In order to counteract catastrophic floods on the Odra River in 1997, two hydrotechnical investments were designed: the Buków reservoir and the dry polder Racibórz Dolny. The design work was completed in 2003. The implementation was blocked for a long time, until 2012, by the WWF Poland organization. WWF Poland activists wanted to implement ecological protection of the Odra Valley against floods. The main assumption of this idea was to move the development away from the Odra River and abandon the project of building hydrotechnical facilities.

In 2013, the Silesian Voivode issued a decision on the construction of a dry polder again (the first decision was made in 2005; it was protested by WWF Poland). Construction began in 2013 (the building company was Dragados, Spain), but due to errors in the selection of materials and failure to adhere to the schedule, the contractor was changed in 2017. The dam and embankments were put into service in 2022. A flood was needed to prove that a dry polder was necessary.

2. Materials and Methods

We analyse water stages and discharges from three stream gauges (see location in

Figure 1 and

Figure 3) in the Upper Odra River, Chałupki, Krzyżanowice, Racibórz-Miedonia. The Institute of Meteorology and Water Management—a national research institute in Warsaw (Poland)—collects these hydrological data. We present the hydrological data covering floodwaves on hydrographs from three different flood events (1997—two months, 2010—two months, 2024—one month, as the event lasted shorter than earlier ones), and we use basic data frequency, i.e., one water stage value per day. Elevation on the hydrographs and everywhere in the text are recalculated to the PL-EVRF2007-NH geodetic system—a part of the European Vertical Reference System (tide gauge in Amsterdam). Additionally, on these hydrographs, we mark a warning stage and an alarm stage. The stage names are word-for-word translations from the Polish vocabulary used by the Institute of Meteorology and Water Management; however, more exact English names might be given as “alert stage” and “flood stage”.

The Chałupki river gauge (

Figure 3A) has had a long observation period, beginning in 1891. Due to its location on the political boundary between Czechia and Poland, it plays a crucial role as the first gauge on the Odra River in the Polish system of hydrological forecasts. The catchment area computed down to the gauging station is 4660 km

2 and it covers mostly mountainous areas in the Carpathians and the Sudetes and a part of the tectonic depression between them—the Racibórz Gate (in Czech: Moravska brána). The distance from the gauge to the outlet of the Odra River into the Szczecin Lagoon (near the Baltic Sea) expressed in river kilometre markers is 725 [km]. The lowest stage, 193.31 m a.s.l., was recorded on 8 October 2015, and the highest on 15 September 2024, thus during the third flood event analysed in our study. At that time, the water stage reached a height of 199.83 m a.s.l.

The Krzyżanowice gauge (

Figure 3B) is located in a very narrow passage between two polders and under a road bridge; however, water flow there is not controlled by any structure nearby (

Figure 1). It is only closed by the embankments of the Racibórz Dolny polder with a spillway in the main dam, a few kilometres downstream from the gauge. The distance from the Chałupki gauge is 12 km measured in river kilometre markers. The catchment area is getting larger (increasing to 5.876 km

2), mostly because of receiving the tributary of the Olza River (

Figure 1), draining the Carpathians and Polish (Silesian) Upland. The highest and lowest water stages were recorded on the same days as in the case of the Chałupki gauge, and their heights were 185.31 m a.s.l. and 194.36 m a.s.l. The highest stage was a result of intentional water storage in the polder during the third flood event studied by us. The observations have been performed since 1927.

The Racibórz-Miedonia is a gauge (

Figure 3C) located downstream from the polder and downstream from the confluence of the Odra River with its bypass channel (

Figure 1). This channel is called Kanał Ulga or New Odra and it is a kind of floodway around the city of Racibórz. The gauge was installed in 1940, shortly after the bypass channel had been constructed. The river valley profile within the gauging station consists of a relatively wide interdike floodplain. The catchment area is 6.731 km

2, thus being 855 km

2 larger than the catchment area computed down to the Krzyżanowice gauge, because a left tributary, the Psina River, flows into the Odra River upstream from the Racibórz-Miedonia gauge. The distance between both gauges in river kilometre markers is 21 km. The lowest water stage was recorded on 7 August 2007. At that time, the water level dropped to a height of 177.04 m a.s.l. The highest water stage was recorded when the floodwave crest of the 1997 flood was passing by through the profile gauge, and the water level reached an elevation on 9 July of almost 10 m above the minimal stage, i.e., 186.8 m a.s.l.

All the gauging stations were visited by the authors in the field in order to determine any possible factor of regional setting which may bias the hydrological data recorded by these instruments.

In the years 2004–2024, the authors prepared environmental impact reports for the exploitation of documented natural aggregate deposits in the reservoir basin in the analysed area [

30]. In this context, they learned in great detail about the environmental conditions of mining projects. In particular, the impact assessment included the following:

Transformation of the land surface;

Emission of gases and dust;

Generation of waste;

Introduction of sewage into water or soil;

Emission of noise, etc.

A set of factors that may significantly affect the environment was also taken into account:

These partial experiences were used to assess the impact of the dry polder on the environment; an analysis of the spatial development of the area was carried out, and a simulation of the passage of the floodwave from September 2024 was performed under the conditions of the implementation of the “ecological variant”—without the participation of the dry polder in the protection of the Odra Valley.

To determine the relation between (i) water stage and (ii) discharge, we use rating curves calculated by the Institute of Meteorology and Water Management, a national research institute in Warsaw (Poland), calculated for each gauge. We use the same rating curves for reconstruction of possible discharges during the 2024 flood event in scenarios without storage of water in dry polder, but firstly a gauge-to-gauge correlation was conducted on the basis of the 1997 and the 2010 flood events. This method is based on the analysis of hydrographs and selection of a set of corresponding water stages observed at two gauging stations. The resulting dataset is then plotted on a graph and subsequently fitted with a function to obtain equations that best describe the observed relationship.

3. Results

3.1. Floods on the Upper Odra River

3.1.1. Pluvial Floods—A Dynamic Comparison

The main result of our study—the nine hydrographs in

Figure 4—can be read from the left to the right if the reader aims to compare the following (1997, 2010, 2024) flood events at the same river gauge, or from the top to the bottom if the reader prefers to analyse how the floodwave moves and transforms at the adjacent river gauges (from Chałupki, via Krzyżanowice to Racibórz-Miedonia).

To start with a comparison of the following flood events at the same gauges, the 1997 and 2010 floods were similar in some parts. Both events have a very steep increasing part of the main floodwave and a secondary floodwave afterwards; however, the main floodwave was dramatically higher (almost 1 m) and steeper in 1997 than in 2010.

The 2024 event is different from the 1997 and the 2024 floods as it consists of one floodwave only, and the wave is lower than that in the main floodwave in 1997, lower especially at the Racibórz-Miedonia gauge and a little bit wider, especially at the Krzyżanowice gauge (note: the 2024 hydrographs refer to the period of one month only, while the 1997 and the 2010 hydrographs cover two months). The heights of the crests of the 2010 and the 2024 floodwaves in Chałupki and Krzyżanowice seem comparable.

The discharges on floodwave crests are presented in

Table 1 in the same way as the hydrographs (

Figure 4); thus, they can be analysed from the left to right or from the top to the bottom depending on the need of analyser. The 1997 flood brought two times more water than to the entrance of our studied reach (Chałupki) in the 2010 flood. The 2024 flood was intermediate between the 1997 and the 2010 events in terms of the amount of water flowing through the Chałupki gauge. In Krzyżanowice, the gauge readings for the 2010 and the 2024 floods seem very similar, and both events had significantly less water than the 1997 flood there. In Racibórz-Miedonia, the flow through 2024 was only 37.5% of the flow recorded in 1997. The flow there in 2010 was significantly larger than in 2024 and smaller than in 1997.

The results obtained on the basis of the relationship between the two water-gauge stations and the constructed flow–duration curve demonstrated that without the dry polder, the maximum water level was estimated at 185.94 m a.s.l., with a discharge of about 2239 m3/s. In comparison, the 1997 flood peaked at 2800 m3/s, and the 2010 flood reached 1890 m3/s. The dry polder reduced the water level by approximately 1.65 m and cut the peak discharge by more than 50%. It also shifted the flood’s peak from 15 September to 17 September, which gave downstream communities more time to prepare for the floodwave crest.

3.1.2. September 2024 Flood General Outline

The September 2024 flood caused by heavy rainfall, over 400 mm, was recorded at the Mt. Śnieżnik station [

31]. Incorrectly interpreted forecasts and data coming from Czechia and the fact that rainfall accumulated unevenly in smaller catchments caused significant losses in Lower Silesia. As a result of the flooding, the following cities suffered severe damage: Kłodzko, Głuchołazy, Prudnik, Nysa, Bystrzyca Kłodzka, Szprotawa, and Lewin Brzeski. The Stronie Śląskie reservoir was a relatively small, dry polder with a capacity of 1.38 million m

3, located along the Morawka Stream. The reservoir was built between 1906 and 1908 and modernised in recent years. Throughout its history, it has been used (1938, 1997) to protect the town of Stronie Śląskie. On September 15, it was damaged. The excess water began to overflow the dam’s crest, eventually rupturing its earthen section. The surge reached the towns of Stronie Śląskie and Lądek Zdrój, flooding hundreds of buildings.

The alarm level on the Odra River above the dry polder Racibórz Dolny was exceeded on 13 September 2024 immediately by almost 3 m. In the early morning hours of 15 September, the reservoir dam was closed and the floodwave on the Odra River was stopped. The river remained above the alarm level until 17 September. During this time, the dam was closed and the reservoir held back the floodwave. By 17 September, the Racibórz Dolny reservoir contained 147.9 million m3 of water, which meant it was approximately 80% full. The maximum allowable outflow of 750 m3/s from the reservoir was maintained at all times. In the following days, the floodwave was noted to be decreasing, and the Odra River was restored to its normal level. On 29 September, the emptying of the reservoir and its return to its dry polder state were completed.

Along with the decision to activate the dam in the Racibórz Dolny dry polder, companies extracting natural aggregates were informed about the need to evacuate. The short timeframe allowed only for the removal of most of the wheeled machinery (excavators, loaders, and trucks). The remaining crawler excavators were placed on product piles. The floating excavators were anchored in the production basins. It was impossible to relocate the processing lines and conveyor belts. Many transformer stations and electrical equipment were submerged (

Figure 5).

After emptying the reservoir, it was necessary to remove the material that had flown in with the river: municipal waste, branches, tree fragments, and sheet metal. Technical and service roads were damaged. The damage and losses caused the first mining plants to start production on a limited scale (e.g., one product fraction instead of three) after two months. In many cases, the only possible way to start a plant was to purchase new equipment. Even half a year later, none of the companies had regained their full production capacity from the period before the flood in September 2024.

3.2. Nature and Landscape Protection

The analysed area of the Upper Odra Valley is characterised by a considerable diversity of habitats, which translates into a large floristic diversity of the area, as well as a diversity of fauna. The Upper Odra Valley Ecological Corridor plays an important role in species migrations in this part of Europe. Despite major transformations of the riverbed and floodplains, the Upper Odra Valley is one of the few remnants of large ecological structures in a landscape that has been heavily altered by humans. It is characterised by strong fragmentation and low forest cover. Only small forest areas, wet meadows, and oxbow lakes have survived in this section.

Taking into account the degree of preservation of structure and the degree of preservation of function, the state of preservation of most habitats in the analysed area of the Upper Odra Valley is classified as good or excellent, especially habitats within the boundaries of protected areas within the Natura 2000 network. Patches of oak–hornbeam forest and ash–riparian forest—forest habitats protected within the boundaries of the Special Area of Conservation “Forest near Tworków”—are extensive, occur in typical conditions, and are preserved in very good condition. The best-preserved, several dozen hectares of riparian forest patches have excellent representativeness [

32]; in the analysed area, there are habitats included in Annex I of the Habitats Directive. There are forest habitats, including one priority habitat covering willow, poplar, alder and ash forests, and oak–hornbeam forests. Among the non-forest communities, there are numerous habitats of standing waters: oxbow lakes and eutrophic reservoirs, semi-natural wet tall-herb meadows, and mesophilic grass formations [

32].

The project implementation area is located in the southern part of the international ecological corridor of the Upper Odra Valley.

Within the boundaries of the Racibórz Dolny dry polder, there are habitats and species protected under Polish law and the Habitats and Birds Directives. This area may be a feeding ground for some protected birds, especially predatory birds that feed in open spaces. This area may also be located on the flight path of birds, including protected ones. These are the Natura 2000 Areas (

Figure 6):

Within the boundaries of the SPA “Wielikąt Ponds and Tworków Forest” is the “Wielikąt Nature and Landscape Complex”. This is an area of fishponds and adjacent fields and meadows.

There are three categories of floodplain forests in the Odra River Valley [

32,

33]:

Willow–poplar floodplain forests—requiring about 30 days of flooding per year. They are a rare type of habitat, mainly due to river regulation and the resulting lack of regular, long-term flooding. This habitat type is protected as a priority.

Elm–ash floodplain forests—requiring regular, short periods of flooding. This is a protected habitat.

Alder–ash floodplain forests are mainly associated with the edges of small, rarely flooding streams and oxbow lakes. The habitat is particularly threatened by the regulation of small rivers and streams due to a decrease in the frequency of flooding and lowering of groundwater levels. These habitat types are protected as a priority.

The ecosystems of semi-natural, wet tall-herb meadows are represented by habitats of variable-humidity moor-grass meadows and hydrophilic riverside and river-edge tall-herb communities, while the habitats of mesophilic grassland formations are represented by lowland hay meadows (Habitats Directive).

Within the boundaries of the dry polder, initially, mainly terrestrial ecosystems occurred—mainly agricultural, especially arable land and anthropogenic communities. There was a small share of meadow ecosystems within the boundaries of the permanent grasslands. Over time, exploitation pits in the form of water pools began to dominate the surface (

Figure 7).

Most of the oxbow lakes are eutrophic reservoirs with numerous plant communities. Arable land dominates in the open areas in the Odra valley, on the embankment, and in the inter-embankment meadows, and pastures are used extensively. Some of the unused meadows are overgrown with shrubs. Against the background created by arable land, island-like natural refuges and corridors connecting them stand out. Areas of an island character are the Tworkowski Forest, reservoirs in the excavations near the village of Nieboczowy, the Odra oxbow lake in the vicinity of the village of Nieboczowy (in the vicinity of the post-mining excavations), and the Wielikąt ponds.

On the border of the dry Racibórz Dolny polder there is one of the most important wetland bird sanctuaries in Silesia. These are the Wielikąt breeding ponds and the neighbouring Tworków Forest. These areas are protected within the Wielikąt Nature and Landscape Complex, and within the Natura 2000 network (

Figure 5): the Birds Special Protection Areas (SPAs) “Wielikąt Ponds and Tworków Forest” and the Special Area of Conservation (SAC) “Forest near Tworków”.

The Wielikąt Nature and Landscape Complex covers an area of 636.96 ha and consists of nine larger and several smaller breeding ponds. The natural value of this area is primarily determined by the occurrence of many valuable species of water and marsh birds. In the SPA “Wielikąt Ponds and Tworków Forest”, 24 bird species are protected, listed in Annex I of Council Directive 2009/147/EC, the so-called Birds Directive, including white-tailed eagle, little bittern, ferruginous duck, red-crested pochard, and others.

In addition to the previously mentioned species, the excavations remaining after the extraction of natural aggregates within the dry polder and its vicinity are a nesting site for black-headed gulls, little terns, and water birds such as mute swan, mallard, common pochard, and tufted duck [

32].

3.3. Mineral Resources

The deposits documented in the Racibórz Dolny reservoir bowl (

Table 2,

Figure 8) are water-logged. The Quaternary aquifer occurs at a depth of about 1–3.6 m. The deposit series consists of Quaternary sands and gravels, which form a fairly regular bed with a fairly simple structure. In addition to soil, the overburden contains silty clay, clay, and dust formations. The thickness of the overburden ranges from 2.3 to 6 m, with an average of 4.2 m [

17,

30]. The depth of the bottom of the deposits is 9.2–12 m and the average thickness of the deposits is 6.3 m (

Figure 2 and

Figure 8).

The mineral that will be sent to the processing plant is sand with gravel with an average sand point (pp) of 36.1. The dust content slightly exceeds 1%. The petrographic composition is dominated by Carpathian sandstones and quartz, gneisses, lydites, and rocks transported here by the glacier, i.e., granites and Scandinavian sandstones [

21].

Initially, mining was carried out on a small scale. Only the decision to relocate the residents of the village of Nieboczowy accelerated interest in this area. The mining industry has been represented by 24 companies in the period from 2012 to the present.

In the period of 2013–2015, there was a steady increase in the extraction of natural aggregates, mainly by medium-sized and small plants (

Figure 9). Some of them used joint processing plants [

36]. The most was extracted from the Bieńkowice Wschód deposit, a total of 16,831 thousand tonnes. In 2015, extraction from the Racibórz Dolny dry polder accounted for 61% of the production of the Silesian province.

The environmental impact of exploitation is very limited. Mining takes place under very favourable conditions, causing damage to the surface, but this is an area that is flooded in the event of a flood. The noise generated by mining machinery is effectively contained by the flood control reservoir embankment. Measurements and modelling of sound wave propagation indicate no exceedances of standards or nuisance to residents. The mineral is highly saturated with water, which means there are no dust emissions.

In summary, it can be stated that the extraction of natural aggregates within the Racibórz Dolny reservoir basin is consistent with the principles of a circular economy [

37]. On-site material extraction accomplishes the following:

4. Discussion

Flood protection can be implemented in various ways. Classic retention reservoirs can realise multiple functions: flood control, energy generation, drinking water storage, recreational, and tourist purposes. Electricity production in pumped-storage reservoirs has been defined as clean, renewable energy. Retention reservoirs obviously have their advantages and disadvantages. Since protests against the construction of such reservoirs have become increasingly numerous in recent years, it seems we should seek new solutions or return to older, less frequently implemented ideas.

However, if we examine the current operation of such a plant, it turns out that hydropower plants operate as suppliers very rarely. Energy consumption predominates during the day, when a large amount of photovoltaic-generated energy is fed into the grid. Therefore, we can say today that hydroelectric power plants play the role of a transistor and a stabilizer in the power grid.

4.1. Accuracy of Hydrological Data

The height of the 2024 floodwave crest in Chałupki is biased by the data frequency (one value per one day), more than the 1997 and the 2010 floodwave crests, because the true crest of the 2024 flood was slightly higher than in the 1997 event and much more higher than in the 2010 event. This suggests that the discharge at the Chałupki gauge in 2024 should be greater than in 1997 as well.

We also speculate about the possible impact of a local, hydraulic setting on water stages in Chałupki, because the gauging station is located 220 m downstream from an old bridge constructed in a place where the spacing of levees (a distance between the left dike and right dike) decreases from 400 to 140 m. The bridge has four piers, and it is relatively low—its bottom is 41 cm higher only than the floodwave crest recorded in 1997 according to Czech authorities [

38]. As a result of the above conditions, during extreme flooding, a water stage at the Chałupki gauge may be lower than that upstream from the bridge. Further hydraulic analysis is limited by the transboundary course of the Odra River next to the Chałupki gauging station.

Two-dimensional hydrodynamic modelling [

39] suggests that the peak discharges in the 1997 flood were much higher than those estimated from the rating curve and presented in

Table 1. The difference (underestimation from the rating curve) at the Chałupki gauge is 240 m

3/s, at the Krzyżanowice gauge—260 m

3/s, and at the Racibórz-Miedonia gauge—320 m

3/s. During the 2024 flood event, the peak discharges on the Upper Odra River were not measured directly at all in the field due to extremely high flow velocities in the channel (based on personal communication with a hydrologist who measured the discharge during the 2024 flood in Wrocław (Middle Odra River) using an ADCP (Acoustic Doppler Current Profiler) device installed on a boat). This way of measurement performed on the Lower Vistula River during the 2010 flood in a very specific place (around the levee breach in Świniary upstream from Płock city), impacted by large flow velocities (exceeding 1.5 m/s), gave very distant values of discharge (881 m

3/s vs. 1023 m

3/s), which were dependent on the manner of ADCP positioning: bottom tracking vs. GPS-RTK [

40]. Extreme discharges possibly generate very deep scour and the associated enormous sediment transport by bed load (saltation) and suspended load, which may reduce the possibility of accurate discharge measurements by ADCP, especially if scour depths are commonly underestimated; indirect observations suggest a depth greater than 12 m [

41].

4.2. Efficiency of Structural Flood Management

If we consider the hydrological data gathered during the extreme flood event to be insufficiently accurate, we can speculate that construction of the Racibórz Dolny dry polder significantly reduced the peak discharges and the height of the floodwave crest in the 2024 event compared to a lack of these structures in the 1997 and the 2010 floods. Probably, an overtrained river like the Upper Odra River cannot be easily switched to non-structural flood management as postulated for European Rivers [

42]; however, dam removal in Eastern Europe and Asia is likely to be successful in the future, similar to that in Western Europe and the US.

4.3. Green Infrastructure on a Large Scale

Due to the political changes in Poland, the Świnna Poręba reservoir on the Skawa River is among the longest-running in terms of construction time: 1986–2020. Despite extended completion dates, significant natural aggregate resources were irretrievably flooded due to filling with water. In comparison, the Liptovská Mara reservoir on the Váh River (Slovakia) also flooded aggregate deposits. However, aggregate extraction is currently being conducted underwater in part of the reservoir.

The analysis of three selected hydrotechnical projects indicates that the reservoirs in Świnna Poręba and Liptovská Mara have caused permanent inundation of river valleys, alterations of the hydrological regime, and substantial transformations of terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems (

Table 3). In contrast, the environmental impacts of the Racibórz Dolny dry polder are less severe: flooding occurs only periodically, there is no threat of landslides or permanent loss of mineral resources, and the river regime is affected primarily through the reduction of floodwaves. With regard to the utilisation of mineral resources, clear differences emerge: in Świnna Poręba, aggregate extraction was limited to the construction phase only, whereas in both Liptovská Mara and Racibórz Dolny, natural aggregates were obtained during construction as well as after the commissioning of the facility [

37].

Observations conducted in July 2025 in the area of the Racibórz Dolny dry polder (10 months after the flood) indicate that there were no visible changes in the morphology or vegetation of the polder canopy. Drainage ditches and small watercourses were not affected. In the spring of 2025, sowing of areas excluded from mining operations (levelled and partially reclaimed areas) was carried out. These were primarily corn crops requiring high irrigation, but also sunflowers (

Figure 10). Numerous birds (gulls and pigeons) were seen around the mine workings, on the dumps, and on the shores. In May 2025, the Regional Water Management Board in Gliwice began a nature inventory to determine the impact of filling the Racibórz Dolny reservoir with water.

Just as cities are expected to implement and develop green and blue infrastructure, it seems necessary to look beyond urbanised areas [

43,

44,

45]. In this case, the scale of the facility increases, but this also increases its impact. It seems that a dry polder like Racibórz Dolny could be the first example of large-scale green infrastructure. It is also a response to the dramatic history of the Odra Valley in terms of high floods.

5. Conclusions and Recommendation

The Odra River Valley is known for its pluvial floods. The Racibórz Dolny dry polder, commissioned in 2022, lowered the floodwave on the Odra River in September 2024 by 1.65 m at the Racibórz-Miedonia gauge, halved an expected discharge at the floodwave crest there, and delayed the movement of the floodwave downstream by two days. As a result, the residents of Racibórz, Opole, and Wrocław were relatively safe compared to the 1997 catastrophic flood.

The results of hydrological calculations clearly indicate that if the flow had not been closed and the Racibórz Dolny reservoir had not been filled, the Odra River Valley would have been flooded. The scale of the flood in Racibórz and below would have been greater than that in 2010, and at its peak, it could have been comparable to that in 1997. The Racibórz Dolny reservoir is crucial for safety management in the Upper Odra Valley. Therefore, increasing its capacity through continued aggregate extraction is desirable.

Exploitation of natural aggregates in the basin of the Racibórz Dolny dry polder is primarily conducted using open-pit mining. Mining is conducted in the basin workings using floating equipment (suction dredgers). The deposits are water-logged, typically under 1–4 m of overburden. Unlike traditional retention reservoirs in Poland, the construction of the Racibórz Dolny dry polder did not result in permanent flooding of the river valley or loss of natural aggregate resources. Mining from the reservoir’s basin, however, conserves land-based deposits and, consequently, reduces environmental degradation in the surrounding area. Deposits on the Odra River terraces are easily accessible and do not cause any problems during mining. Natural aggregates from the Odra Valley are of good quality and enable the production of various fractions, including gravel.

A preliminary assessment of the area’s natural changes indicates that its main assets have been preserved. One of the key factors was the avifauna, whose mobility allowed it to evacuate and return after the floodwaters had passed. Detailed environmental studies are underway by the services responsible for managing the dry polder.

In total, 42,602 tons of natural aggregate were extracted from the reservoir basin. As a result of exploitation in the period 2007–2023, 25,349 m3 of rocks was extracted, thus increasing the flood capacity of the Racibórz Dolny reservoir by 13%. Currently, the reservoir can hold 185 million m3 of water, but there is a plan to deepen it by exploiting documented reserves of natural aggregate deposits of up to 300 million m3. The deepening could take up to 10 years.

Gravel mines and agricultural crops are operating within the reservoir basin, and currently there is no indication that in September 2024, everything was covered by approximately 7 m of water. Mining operations are not possible while the reservoir is filling. It is also important that mining facilities, electrical stations, fuel storage facilities, and parts storage facilities can be evacuated. Experience from the 2024 flood indicates that heavy, immobile machinery must remain within the reservoir basin. Restoring full production took more than six months.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G. and G.W.; methodology, A.G. and G.W.; software, G.W., M.U.-Ż., and S.G. validation, G.W., M.U.-Ż., and J.K.; formal analysis, G.W. and M.U.-Ż.; investigation, A.G., G.W., M.U.-Ż., S.G., and J.K.; resources, S.G. and M.U.-Ż.; data curation G.W., M.U.-Ż., and S.G.; writing—original draft preparation A.G. and G.W.; writing—review and editing, A.G., S.G., and G.W.; visualization, G.W., M.U.-Ż., and S.G.; supervision, A.G., G.W., and J.K.; project administration, A.G.; funding acquisition, A.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This article has been supported by the Mineral and Energy Economy Research Institute of the Polish Academy of Sciences statutory research, by the Polish National Agency for Academic Exchange, Faculty of Geology, Geophysics, and Environmental Protection at the AGH University, as part of statutory research 16.16.140.315.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the three anonymous reviewers for their valuable suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Korus, J.T.; Joeckel, R.M.; Mittelstet, A.R.; Shrestha, N. Multiscale characterization of splays produced by a historic, rain-on-snow flood on a large braided stream (Platte River, Central USA). Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2024, 49, 4788–4807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas, A.; Rahman, M.A.; Strong, A.; Tate, E. Economic benefits of a rural distributed flood storage system. Prog. Disaster Sci. 2025, 26, 100422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalicki, T.; Przepióra, P.; Kusztal, P.; Chrabąszcz, M.; Fularczyk, K.; Kłusakiewicz, E.; Frączek, M. Historical and present-day human impact on fluvial systems in the Old-Polish Industrial District (Poland). Geomorphology 2020, 357, 107062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elhamid, H.F.; Franzetti, L.A.; Zeleňáková, M.; Kaya, Y.Z. Development of integrated hydrologic and hydrodynamic models for flood modelling in Radiša catchment at Western Slovakia using HEC-HMS and HEC-RAS. Nat. Hazards 2025, 121, 22183–22209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, M.; Sadowski, A.J. Conceptual classification model for Sustainable Flood Retention Basins. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 624–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahedifard, F.; Madani, K.; AghaKouchak, A.; Thota, S.K. Are we ready for more dam removals in the United States? Environ. Res. Infrastruct. Sustain. 2021, 1, 013001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wawręty, R.; Żelaziński, J. (Eds.) Zapory a Powodzie; Towarzystwo na rzecz Ziemi (Oświęcim): Oświęcim, Poland; Polska Zielona Sieć (Kraków): Warsaw, Poland, 2008. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Lejon, A.G.C.; Renöfält, B.M.; Nilsson, C. Conflicts Associated with Dam Removal in Sweden. Ecol. Soc. 2009, 14, 4. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/26268322 (accessed on 2 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Hommes, L. The Ageing of Infrastructure and Ideologies: Contestations Around Dam Removal in Spain. Water Altern. 2022, 15, 592–613. Available online: https://www.water-alternatives.org/index.php/alldoc/articles/vol15/v15issue3/674-a15-3-3/file (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Hac, P.; Faur-Poenar, M.; Marginean, M. The Dam Removal Europe movement reaches Romania. Oryx 2024, 58, 145–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habel, M.; Mechkin, K.; Wagner, I.; Grabowski, Z.; Kaczkowski, Z.; Absalon, D.; Szatten, D.; Matysik, M.; Pytel, S.; Jurczak, T.; et al. Dammed context: Community perspectives on ecosystem service changes following Poland’s first dam removal. Land Degrad. Dev. 2024, 35, 2184–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Chen, L.; Ding, C.; Tao, J. Global Trends in Dam Removal and Related Research: A Systematic Review Based on Associated Datasets and Bibliometric Analysis. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2019, 29, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehner, B.; Beames, P.; Mulligan, M.; Zarfl, C.; De Felice, L.; van Soesbergen, A.; Thieme, M.; de Leaniz, C.G.; Anand, M.; Belletti, B.; et al. The Global Dam Watch database of river barrier and reservoir information for large-scale applications. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubicki, A.; Słota, H.; Zieliński, J. Dorzecze Odry: Monografia Powodzi, Lipiec 1997; IMGW-PIB: Warszawa, Poland, 1999; 164p. [Google Scholar]

- Program for the Odra 2006—Update 2011. The Government Plenipotentiary for the Program for the Odra. In Journal of Laws 2001.98.1067; Government of Poland: Warsaw, Poland, 2011; p. 183. [Google Scholar]

- Słysz, K. Prognoza Oddziaływania na Środowisko Projektu Dokumentu Programu dla Odry—2006 (Aktualizacja); Instytut Meteorologii i Gospodarki Wodnej; Instytut Rozwoju Miast; Instytut Ochrony Środowiska: Kraków, Poland, 2010. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Hydroprojekt. Budowa Zbiornika Przeciwpowodziowego Racibórz Dolny na Rzece Odrze, Województwo’ Sląskie—Polder, Raport o Oddziaływaniu na’ Srodowisko (Construction of the Flood Reservoir Racibórz Dolny on the Oder River, Silesian Voivodeship—Polder); Hydroprojekt Sp. z o.o.: Warszawa, Poland, 2009. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Szuwarzyńska, K.; Poręba, E.; Porwisz, B. Studium Koncepcyjne Zagospodarowania Złoża Kruszyw Naturalnych w Obrębie Czaszy Projektowanego Zbiornika Racibórz Dolny na Rzece Odrze Wraz z Wytycznymi Rekultywacji i Zagospodarowania Nadkładu, Część I—Projekt Zagospodarowania Złoża; Przedsiębiorstwo Geologiczne S.A.: Krakowie, Poland, 2004. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Solon, J.; Richling, A.; Dobrowolski, R.; Migoń, P.; Myga-Piątek, U.; Ziaja, W. Physico-geographical mesoregions of Poland: Verification and adjustment of boundaries on the basis of contemporary data. In Geographia Polonica; Taylor & Francis: Oxfordshire, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Trzempla, M. Szczegółowa Mapa Geologiczna Polski w Skali 1:50 000 Arkusz Racibórz (966) Wraz z Objaśnieniami; Państwowy Instytut Geologiczny—Państwowy Instytut Badawczy (PIG-PIB): Warszawa, Poland, 1997. (In Polish)

- Trzempla, M. Szczegółowa Mapa Geologiczna Polski w Skali 1:50 000 Arkusz Polska Cerekiew (939) Wraz z Objaśnieniami; Państwowy Instytut Geologiczny—Państwowy Instytut Badawczy (PIG-PIB): Warszawa, Poland, 1996. (In Polish)

- Sroczyński, W. Uwarunkowania Geologiczne Realizacji Zbiornika Przeciwpowodziowego Racibórz Dolny na Rzece Odrze; Studia; Rozprawy; Monografie; PAN, IGSMiE: Kraków, Poland, 2002. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Guzik, K.; Kamyk, J.; Kot-Niewiadomska, A. Undeveloped deposits of sand and gravel aggregates with potential strategic importance in Poland. Miner. Resour. Manag. 2024, 40, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamon, T. Development of the topography-controlled Upper Odra ice lobe (Scandinavian Ice Sheet) in the fore-mountain area of southern Poland during the Saalian glaciation. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2015, 123, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamon, T. Elsterian ice sheet dynamics in a topographically varied area (southern part of the Racibórz–Oświęcim Basin and its vicinity, southern Poland). Geol. Q. 2017, 61, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Faměra, M.; Grygar, T.M.; Ciszewski, D.; Czajka, A.; Álvarez-Vázquez, M.Á.; Hron, K.; Fačevicová, K.; Hýlová, V.; Tůmová, Š.; Světlík, I.; et al. Anthropogenic records in a fluvial depositional system: The Odra River along The Czech-Polish border. Anthropocene 2021, 34, 100286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasperek, R.S. Changes in the Meandering Upper Odra River as a Result of Flooding Part I. Morphology and Biodiversity. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2015, 24, 2459–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicki, T.; Magnuszewski, A. Potencjał Powodziowy Rzek Polski. In Gospodarka wodna w Polsce; Magnuszewski, A., Ed.; Monografie Komitetu Gospodarki Wodnej Polskiej Akademii Nauk: Warsaw, Poland, 2024; Volume 45, pp. 147–161. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Françou, J.; Rodier, J.A. Essai de classification des crues maximales. In The Floods and Their Computation: Proceedings of the Leningrad Symposium; IAHS-UNESCO-WMO: Gentbrugge, Belgium, 1969; pp. 518–527. [Google Scholar]

- Gałaś, A.; Gałaś, S. Raport o Oddziaływaniu na Środowisko Przedsięwzięcia Polegającego na Wydobywaniu Kruszywa Naturalnego ze złóż “Racibórz II—Zbiornik 3” i “Racibórz II—Zbiornik 6”; GEOMORR: Gmina Lubomia, Poland, 2024. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- RainGRS Opad Całkowity dla 72h oraz 96h. Centrum Modelowania Meteorologicznego IMGW, 2024-09-16. Available online: https://cmm.imgw.pl (accessed on 29 September 2024).

- Nowak, Waloryzacja przyrodnicza rejonu zbiornika i prognoza oddziaływania zbiornika na faunę i florę. In Opracowanie Na Rzecz Studium Wykonalności dla Zbiornika Przeciwpowodziowego Racibów Dolny na Rzece Odrze; Jacobs GIBB Polska, Hydroprojekt: Warszawa, Poland, 2003. (In Polish)

- Smolnicki, K.; Nieznański, P. Natura 2000 w Dolinie Odry, Czyli Odrą do Europy; Światowy Fundusz na Rzecz Ochrony Przyrody oraz Dolnośląska Fundacja Ekorozwoju: Wrocław, Poland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Midas (System of Management and Protection of Mineral Resources in Poland) 2025 Polish Geological Institute—National Research Institute. Available online: https://midas-app.pgi.gov.pl/ords/r/public/midas (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Szuflicki, M.; Malon, A.; Tymiński, M. Bilans Zasobów Złóż Kopalin w Polsce Według Stanu na Dzień 31.12.2024 r.; PIG-PIB: Warszawa, Poland, 2025. (In Polish)

- Gałaś, S.; Gałaś, A.; Zeleňáková, M. Environmental resources management in the light of construction of reservoir and a polder exemplified by construction of the reservoirs in Świnna Poręba and Racibórz Dolny, Poland. In Proceedings of the International Multidisciplinary Scientific Geoconferences, 17th GeoConference on Ecology, Economics, Education and Legislation, Environmental Economics, Albena, Bulgaria, 29 June–5 July 2017; Volume 17, pp. 337–344. [Google Scholar]

- Gałaś, S.; Gałaś, A. Construction of Hydrotechnical Structures in Terms of Rational Management of Mineral Resources. In Water Management and the Environment: Case Studies; Zelenakova, M., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 29–41. [Google Scholar]

- Parzonka, W.; Głowski, R.; Kasperek, R. Ocena Przepustowości Doliny Górnej Odry Między Chałupkami a Ujściem Olzy; Infrastruktura i Ekologia Terenów Wiejskich: Kraków, Poland, 2006; Volume 4/2. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Banasiak, R.J. Verification of the peak discharges of the flood in July 1997 on the Odra River. Acta Sci. Pol. Form. Circumiectus 2019, 18, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wierzbicki, G.; Ostrowski, P.; Mazgajski, M.; Bujakowski, F. Using VHR multispectral remote sensing and LIDAR data to determine the geomorphological effects of overbank flow on a floodplain (the Vistula River, Poland). Geomorphology 2013, 183, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wierzbicki, G.; Ostrowski, P.; Falkowski, T.; Mazgajski, M. Geological setting control of flood dynamics in lowland rivers (Poland). Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 636, 367–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conitz, F.; Zingraff-Hamed, A.; Lupp, G.; Pauleit, S. Non-Structural Flood Management in European Rural Mountain Areas—Are Scientists Supporting Implementation? Hydrology 2021, 8, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiszek, M.; Krzysztofik, R. Green Infrastructure as an Effective Tool for Urban Adaptation—Solutions from a Big City in a Postindustrial Region. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starczewski, T.; Douša, M.; Lopata, E. An analysis of urban green spaces—A case study in Poland and Slovakia. Acta Sci. Pol. Adm. Locorum 2023, 22, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jóźwik, J.; Dymek, D. Spatial diversity of ecological stability in different types of spatial units: Case study of Poland. Acta Geogr. Slov. 2021, 61, 8779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).