Tripartite Evolutionary Game for Carbon Reduction in Highway Service Areas: Evidence from Xinjiang, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Factors Influencing Carbon Reduction in Highway Service Areas

2.2. Carbon Reduction Measures for Highway Service Areas

2.3. Applications of Evolutionary Game Theory

2.4. Energy Transition in Remote Grid Areas

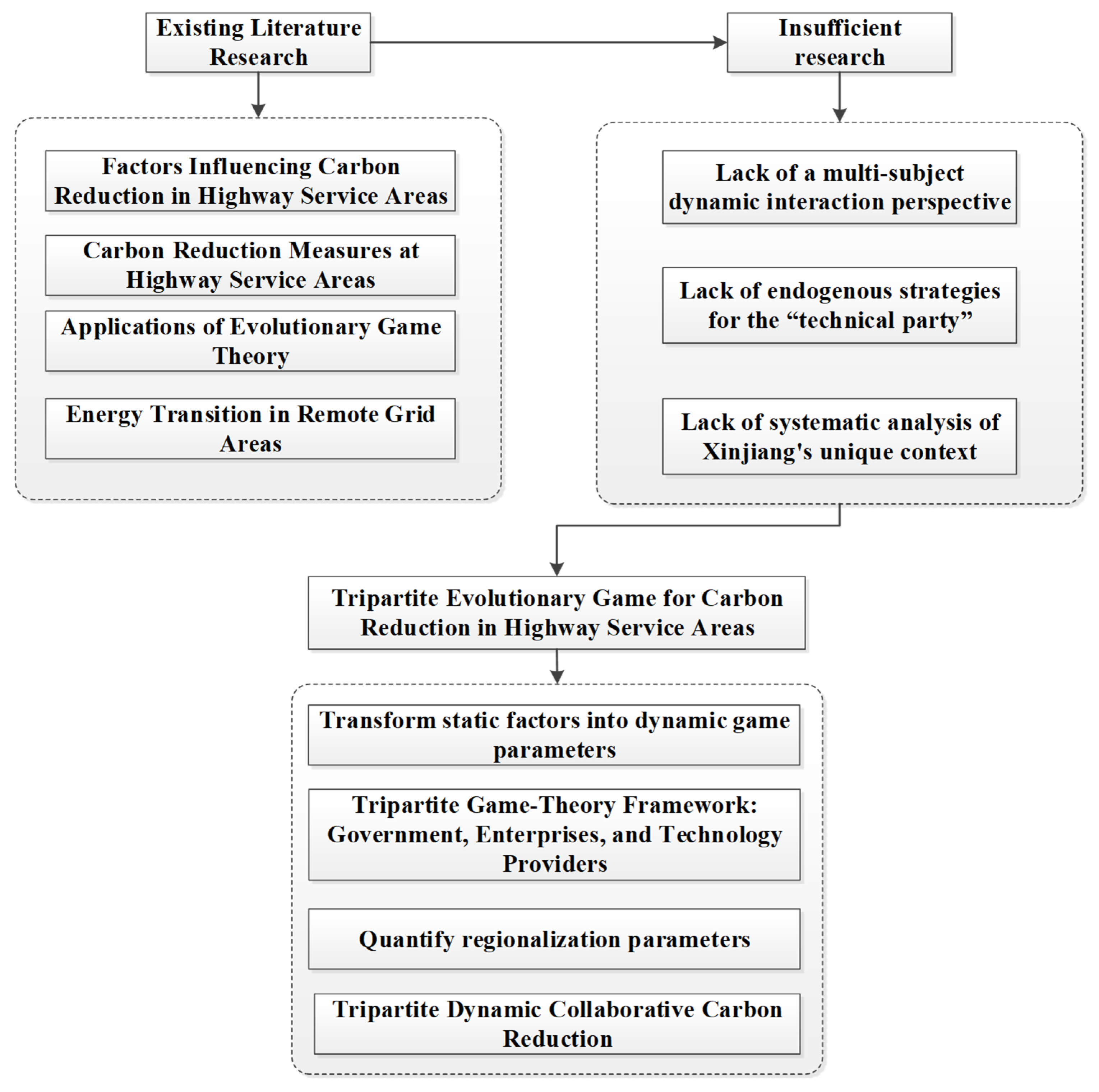

2.5. Research Gaps and Critical Review

2.6. Research Framework and Technical Approach

3. Construction of a Tripartite Evolutionary Model for Carbon Reduction in Highway Service Areas in Xinjiang, China

3.1. Game Participants and Model Assumptions

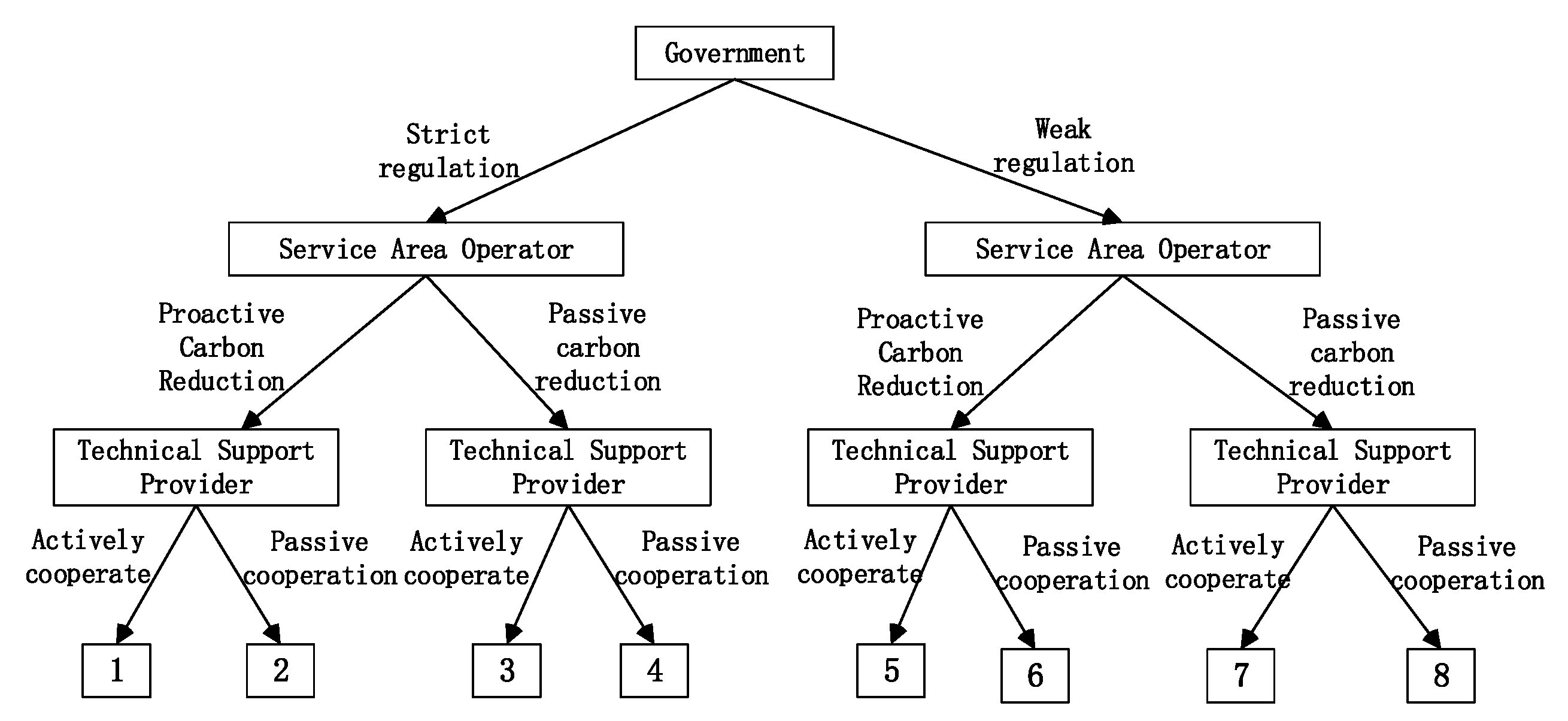

3.1.1. Game Participants and Behavioral Strategies

3.1.2. Model Assumptions

3.2. Establishment of a Tripartite Evolutionary Game Model

3.2.1. Parameter Settings

3.2.2. Tripartite Evolutionary Game Dynamic Reproduction Equation

4. Tripartite Evolutionary Game Analysis

4.1. Tripartite Evolutionary Path Analysis

4.2. Tripartite Evolutionary Stability Analysis

5. Simulation Analysis of Tripartite Evolutionary Games

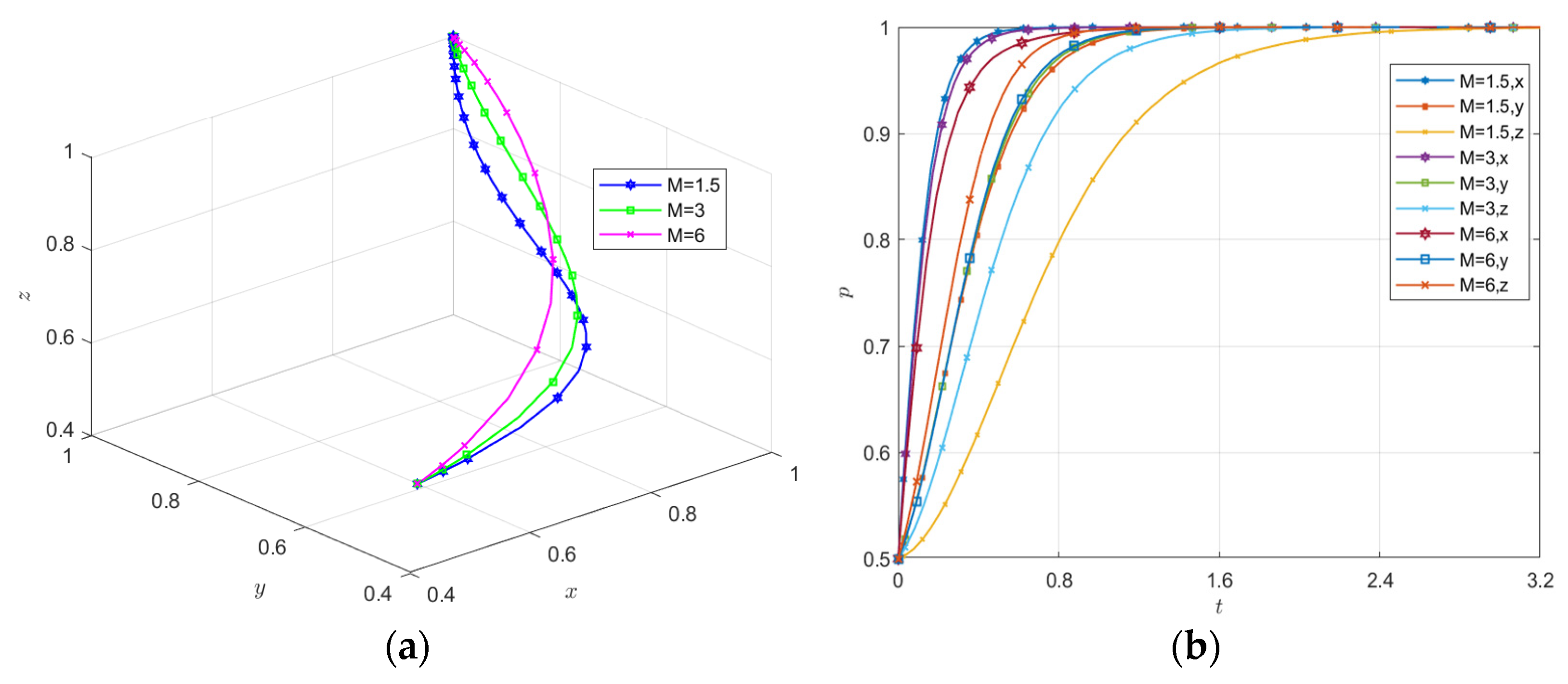

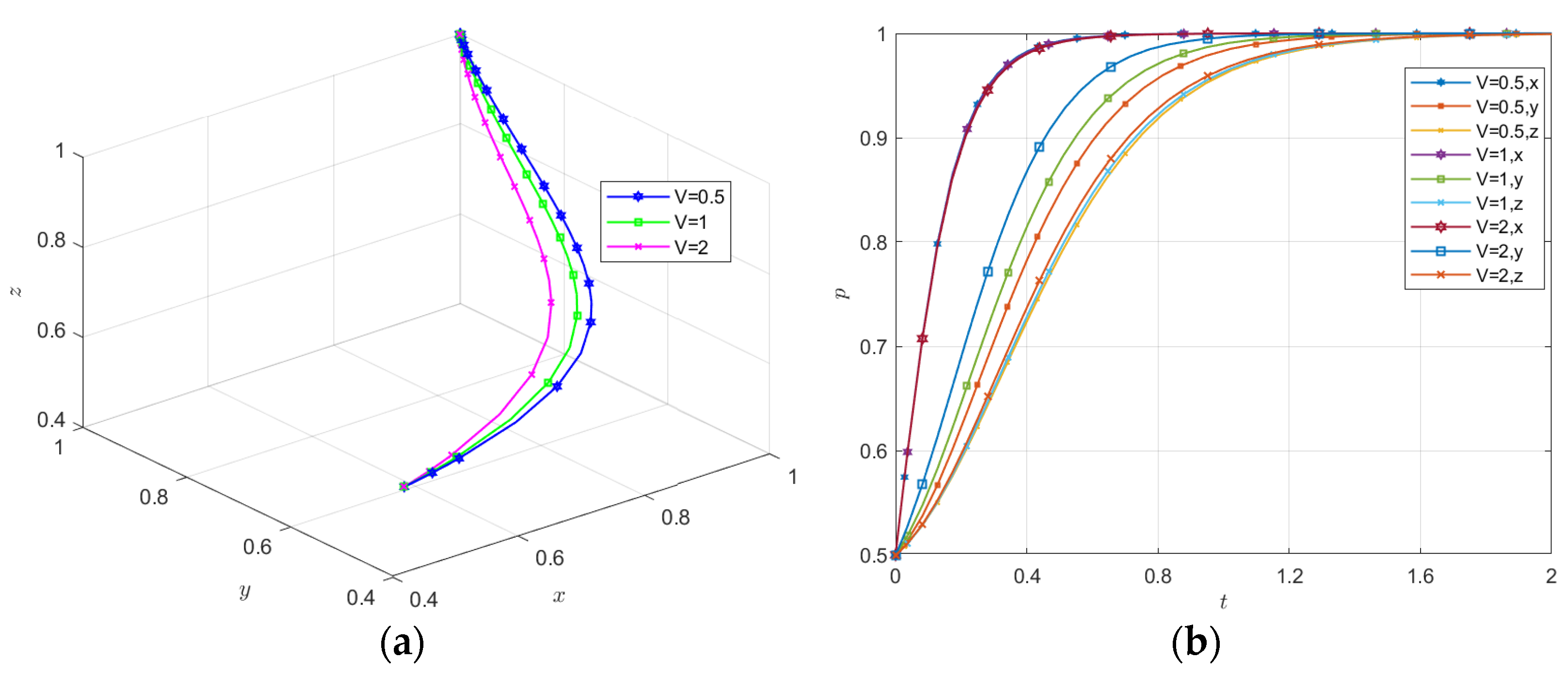

5.1. Simulation of the Tripartite Evolutionary Pathway

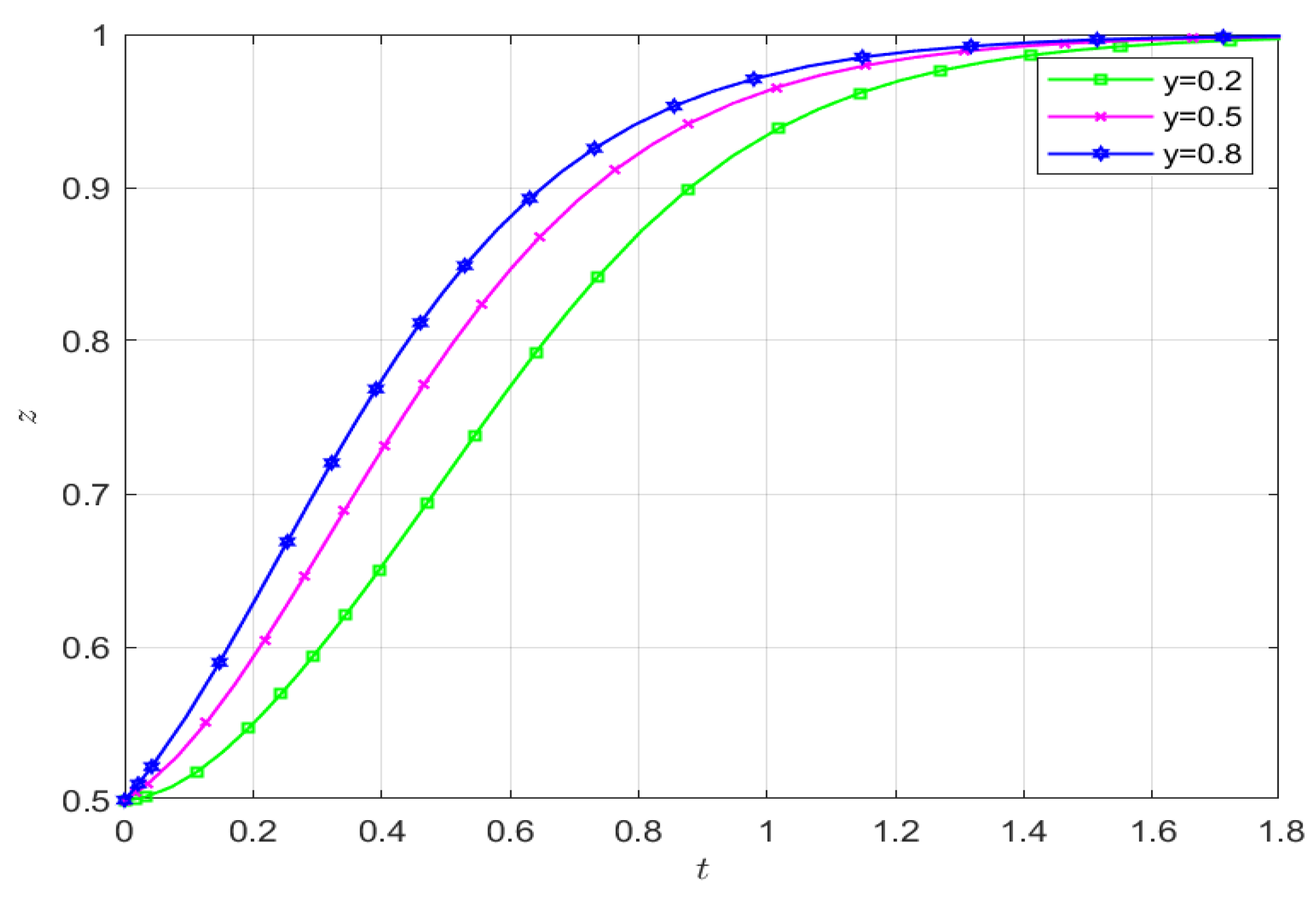

5.2. Simulation of the Impact of Initial Value Changes on Evolutionary Outcomes

5.3. Parameter Sensitivity Simulation

5.4. Limitations and Generalizability of Models

5.5. Model Validation and Robustness

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Policy Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. MATLAB Simulation Code and Parameter Table (Full Versions of All Code Are Available from the Authors)

- Cg1 = 5; Cg2 = 8; S = 3; M = 3; Bg = 10; F = 2; Ce1 = 4; Ce2 = 1; Ce3 = 1; Re = 1; k = 1; V = 1; Ct1 = 10; Ct2 = 5; Rt = 3; arf = 0.5; bta = 2;

- dydt=zeros(3,1);

- dydt(1) = −y(1)*(y(1) − 1)*(Bg+(1 − y(2))*F − Cg1+Cg2 − y(2)*S − y(3)*M);

- dydt(2) = −y(2)*(y(2) − 1)*(Re*k+V+y(1)*(S+F)+y(3)*arf*(Ce1+Ce3)+Ce2 − (Ce1+Ce3));

- dydt(3) = −y(3)*(y(3) − 1)*(y(2)*(bta − 1)*Rt+Rt+y(1)*M+Ct2 − Ct1);

- dydt = zeros(3,1);

- dydt(1) = −y(1)*(y(1) − 1)*(Bg+(1 − y(2))*F − Cg1+Cg2 − y(2)*S − y(3)*M);

- dydt(2) = −y(2)*(y(2) − 1)*(Re*k+V+y(1)*(S+F)+y(3)*arf*(Ce1+Ce3)+Ce2 − (Ce1+Ce3));

- dydt(3) = −y(3)*(y(3) − 1)*(y(2)*(bta − 1)*Rt+Rt+y(1)*M+Ct2 − Ct1);

- clc,clear;

- Cg1 = 5; Cg2 = 8; S = 3; M = 3; Bg = 10; F = 2; Ce1 = 4; Ce2 = 1; Ce3 = 1; Re = 1; k = 1; V = 1; Ct1 = 10; Ct2 = 5; Rt = 3; arf = 0.5; bta = 2;

- Cg1 = 5; Cg2 = 8; S = 3; M = 3; Bg = 10; F = 2; Ce1 = 4; Ce2 = 1; Ce3 = 1; Re = 1; k = 1; V = 1; Ct1 = 10; Ct2 = 5; Rt = 3; arf = 0.5; bta = 2;

- Cg1 = 5; Cg2 = 8; S = 3; M = 3; Bg = 5; F = 2; Ce1 = 4; Ce2 = 1; Ce3 = 1; Re = 1; k = 1; V = 1; Ct1 = 10; Ct2 = 5; Rt = 3; arf = 0.5; bta = 2;

- Cg1 = 5; Cg2 = 8; S = 3; M = 3; Bg = 10; F = 2; Ce1 = 4; Ce2 = 1; Ce3 = 1; Re = 1; k = 1; V = 1; Ct1 = 10; Ct2 = 5; Rt = 3; arf = 0.5; bta = 2;

- Cg1 = 5; Cg2 = 8; S = 3; M = 3; Bg = 20; F = 2; Ce1 = 4; Ce2 = 1; Ce3 = 1; Re = 1; k = 1; V = 1; Ct1 = 10; Ct2 = 5; Rt = 3; arf = 0.5; bta = 2;

References

- Deng, Z.; Zhu, B.; Davis, S.J.; Ciais, P.; Guan, D.; Gong, P.; Liu, Z. Global Carbon Emissions and Decarbonization in 2024. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 231–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, M. A Study on the Path Planning and Optimization of Carbon Peaking and Carbon Neutrality in the Highway Service Area. Build. Environ. 2025, 267, 112187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Gao, L.; Tu, W.; He, J.; Tang, J.; Ma, S.; Zhao, X.; Zhu, X.; Brindha, K.; Tao, H. Decomposition and Decoupling Analysis of Carbon Emissions in Xinjiang Energy Base, China. Energies 2022, 15, 5526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Wang, R.; Ma, G. Carbon Emission Scenario Analysis of Data Centers in China under the Carbon Neutrality Target. Int. J. Refrig. 2024, 168, 648–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiam, D.R.; Moll, H.C. The Constraints in Managing a Transition towards Clean Energy Technologies in Developing Nations: Reflections on Energy Governance and Alternative Policy Options. Int. J. Technol. Policy Manag. 2012, 12, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Lu, H.; He, Q.; Yue, W.; Lin, H.; Chen, C.; Wang, Z. Research on Intelligent Service Area of Urban Green Highway. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 310, 022010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; He, X.; Liang, X.; Yu, L. Research on the Decoupling Relationship and Driving Factors of Carbon Emissions in the Construction Industry of the East China Core Economic Zone. Buildings 2024, 14, 1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Z.; Song, T.; Lv, Z. A Practical Method of Carbon Emission Reduction Ratio Evaluation for Expressway Service Area Considering Future Infrastructures. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 1327–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Ren, D.; Ke, C.; Ying, W. Carbon Emission Influencing Factors and Scenario Prediction for Construction Industry in Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2023, 2023, 2286573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neardey, M.; Aminudin, E.; Chung, L.P.; Zin, R.M.; Zakaria, R.; Che Wahid, C.M.F.H.; Hamid, A.R.A.; Noor, Z.Z.N. Simulation on Lighting Energy Consumption Based on Building Information Modelling for Energy Efficiency at Highway Rest and Service Areas Malaysia. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 943, 012062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, M.; Zhu, H.; Jiang, H.; Liu, J. Impact Factors and Peaking Simulation of Carbon Emissions in the Building Sector in Shandong Province. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 87, 109141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammam, A.H.; Nayel, M.A.; Mohamed, M.A. Optimal Design of Sizing and Allocations for Highway Electric Vehicle Charging Stations Based on a PV System. Appl. Energy 2024, 376, 124284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, Y.; Seo, U.-J.; Kim, J.-H. Economic Feasibility of Ground Source Heat Pump System Deployed in Expressway Service Area. Geothermics 2018, 76, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wu, C.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, B.; Xu, C.; Yan, Y.; Liu, F. A DEMATEL-TODIM Based Decision Framework for PV Power Generation Project in Expressway Service Area under an Intuitionistic Fuzzy Environment. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 247, 119099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.; Tang, K.; Lee, K.Y. Optimal Configuration of Self-Consistent Microgrid System with Hydrogen Energy Storage for Highway Service Area. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2023, 56, 7960–7965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, L.; Jiao, L.; Ma, D.; Dong, Y. Research on Indoor Thermal Comfort of Expressway Service Building Based on SPMV. Energy Build. 2024, 303, 113830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, R.; Gao, Q.; Guan, X.; Du, P.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X. Analysis of Building Energy Saving Potential in High-Speed Service Area Based on DeST Energy Consumption Simulation. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 766, 012090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.; New, J.; Copeland, W. Potential Energy, Demand, Emissions, and Cost Savings Distributions for Buildings in a Utility’s Service Area. Energies 2020, 14, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Li, W.-K.; Dai, P. Parametric Analysis of Passive Ultra-Low Energy Building Envelope Performance in Existing Residential Buildings. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 23407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ren, Z.; Peng, Z.; Yang, J.; Chen, Z.; Deng, Z. Impacts of Climate Change and Building Energy Efficiency Improvement on City-Scale Building Energy Consumption. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 78, 107646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Dong, X.; Lei, J.; Zhang, N.; Wang, Q.; Shi, Z.; Yang, J. Life Cycle Assessment of Carbon Capture by an Intelligent Vertical Plant Factory within an Industrial Park. Sustainability 2024, 16, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H.-K.; Park, H.-M.; Kim, J.-Y. Carbon Offset Service and Design Guideline of Tree Planting for Multifamily Residential Sites in Korea. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H. Impacts of Urban Greenspace on Offsetting Carbon Emissions for Middle Korea. J. Environ. Manag. 2002, 64, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramamohan, H.; Raminaidu, S.; Rao, I.S.; Dinakar, P.; Reddy, B.V. Environmental Impact Assessment of Flora and Its Role in Offsetting Carbon along National Highway-16, India. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, K.; Ai, C.; Chen, F. Design and Application of Sewage Treatment Process in Expressway Service Area. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 304, 022075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Pan, J.; Hu, N.; Xie, C. Hydrologic Performance of Bioretention in an Expressway Service Area. Water Sci. Technol. 2018, 77, 1829–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, X.; Yuan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Men, C.; Zhang, Z.; Zheng, X.; Ni, D.; Xi, H.; Zuo, J. Enhanced Denitrification of the AO-MBBR System Used for Expressway Service Area Sewage Treatment: A New Perspective on Decentralized Wastewater Treatment. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Zhu, Y.; Li, W.; Zhang, Q. Low-Carbon and High-Ammonia Nitrogen Dispersed Wastewater Treatment: From “Normal-Sludge” to “Low-Sludge” to “No-Sludge” Modes. Environ. Res. 2023, 233, 116498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makowska, M.; Mazurkiewicz, J. Treatment of Wastewater from Service Areas at Motorways. Arch. Environ. Prot. 2016, 42, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, N.; Wang, H.; Xiu, Y. Study on Influencing Factors and Simulation of Watershed Ecological Compensation Based on Evolutionary Game. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Fan, L.; Zhai, L. Evolutionary Game Analysis of Inter-Provincial Diversified Ecological Compensation Collaborative Governance. Water Resour. Manag. 2022, 37, 341–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, F.; Shi, M.; Li, W. Research on Ecological Protection Mechanisms in Watersheds Based on Evolutionary Games-Inter-Provincial and Intra-Provincial Perspectives. Water Resour. Manag. 2024, 38, 2377–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Pu, H.; Liang, Y. Study on Ecological Compensation of Inter-Basin Water Transfer Based on Evolutionary Game Theory. Water 2022, 14, 3498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Wang, W. Research on Ecological Compensation Mechanism for Energy Economy Sustainable Based on Evolutionary Game Model. Energies 2022, 15, 2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, A.-R.-H.; Liu, Y.; Dong, J.; Chen, Z.-P.; Chen, Z.-J.; Wu, C. Evolutionary Game Analysis of Co-Opetition Strategy in Energy Big Data Ecosystem under Government Intervention. Energies 2022, 15, 2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, K.; Golubchikov, O.; Mehmood, A. Uneven Energy Transitions: Understanding Continued Energy Peripheralization in Rural Communities. Energy Policy 2020, 138, 111288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard, I.; MacKay, D.; Schell, K.R.; Kilpatrick, R.; Abdulla, A. Hydrogen Microgrids to Facilitate the Clean Energy Transition in Remote, Northern Communities. Appl. Energy 2025, 401, 126758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holdmann, G.; Pride, D.; Poelzer, G.; Noble, B.; Walker, C. Critical Pathways to Renewable Energy Transitions in Remote Alaska Communities: A Comparative Analysis. Energy Res. Social Sci. 2022, 91, 102712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veerasamy, V.; Sampath, L.P.M.I.; Qiu, H.; Huang, H.; Li, Y.; Nguyen, H.D.; Ramachandaramurthy, V.K.; Gooi, H.B. Grid Infrastructure and Renewables Integration for Singapore Energy Transition. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 34405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clavel, E.R.G.; Stringer, T.; Rivero, J.C.S.; Burelo, M. Subnational Perspectives on Energy Transition Pathways for Mexico’s Electricity Grid. Util. Policy 2024, 90, 101801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugden, R. The Evolutionary Turn in Game Theory. J. Econ. Methodol. 2001, 8, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, E. Evolving Game Theory. J. Econ. Surv. 1997, 11, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clempner, J.B. On Lyapunov Game Theory Equilibrium: Static and Dynamic Approaches. Int. Game Theory Rev. 2018, 20, 1750033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Tan, J.; Dai, J. Analysis of Decision-Making in a Green Supply Chain under Different Carbon Tax Policies. Mathematics 2023, 11, 4631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, L.; Huang, C. A Tripartite Evolutionary Game and Simulation Analysis of Transportation Carbon Emission Reduction across Regions under Government Reward and Punishment Mechanism. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Peng, L.; Zhao, Y.; Feng, Y. Coevolution Mechanisms of Stakeholder Strategies in the Green Building Technologies Innovation Ecosystem: An Evolutionary Game Theory Perspective. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2024, 105, 107418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadeer, A.; Yang, J.; Zhao, S. Complexity Analysis of the Interaction between Government Carbon Quota Mechanism and Manufacturers’ Emission Reduction Strategies under Carbon Cap-and-Trade Mechanism. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, W.; Huang, R. Supply Chain Enterprise Operations and Government Carbon Tax Decisions Considering Carbon Emissions. J. Cleaner Prod. 2017, 152, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Comparison Dimension | Tripartite Model (Government-Enterprise-Technology Provider) | Government-Enterprise Dual Model | The Unique Value of the Tripartite Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main Components | Three endogenous entities, with the technology provider possessing independent decision-making authority | Two endogenous entities, with technology as an exogenous variable | Addressing the core practical challenge of “technical compatibility difficulties” |

| Interactive Mechanism | Two-way feedback (government → technology → enterprise → technology) | Unidirectional Incentive (Government Subsidies → Corporate Carbon Reduction) | Establish a positive feedback loop of “technology iteration—cost reduction” to avoid the linear dependency inherent in the two-party model. |

| Characteristics of Evolutionary Outcomes | Converges to ESS (1,1,1) | Single stable point: Converging toward “strong regulation—proactive carbon reduction” | Identify the cost threshold of recognition technology to provide precise basis for policy formulation |

| Model Stakeholder | Parameter | Parameter Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Government | Cg1 | Increased costs resulting from stringent government regulation |

| Cg2 | The environmental governance costs incurred by the government’s adoption of weak regulation | |

| Cg3 | The government’s fixed costs for regulating carbon reduction at highway service areas | |

| S | Additional subsidy amount for enterprises’ voluntary carbon reduction efforts under the government’s stringent regulatory environment | |

| M | Additional policy support subsidies provided by the government’s stringent regulatory environment to encourage proactive carbon reduction development cooperation among technology providers | |

| Bg | The positive social benefits resulting from the government’s implementation of stringent regulatory oversight. | |

| F | Government-imposed fines on companies for “passive carbon reduction” under stringent regulation | |

| Service Area Operator | Ce1 | The investment costs for equipment and technology associated with enterprises’ proactive carbon reduction efforts |

| Ce2 | The Cost of “Passive Carbon Reduction” for Enterprises | |

| Ce3 | Follow-up maintenance costs for enterprises’ proactive carbon reduction efforts | |

| Ce4 | Baseline Costs for Service Area Carbon Reduction Management in Enterprises | |

| Re | Economic Savings and Benefits from Corporate “Proactive Carbon Reduction” | |

| k | Revenue elasticity coefficient (k > 0) indicates the amplification effect of corporate proactive carbon reduction efforts on revenue. | |

| V | Potential revenue generated from brand premiums resulting from enterprises’ proactive carbon reduction efforts | |

| L | Losses incurred by enterprises due to inadequate adaptation of carbon reduction technologies or impacts from extreme environmental conditions | |

| β | The multiplier effect of corporate “proactive carbon reduction” on the revenue of technology providers | |

| Technical Support Provider | Ct1 | Additional costs incurred from the technical support provider actively cooperating |

| Ct2 | Opportunity cost losses, reputational damage, and market risk costs resulting from the passive cooperation of the technical support provider. | |

| Ct3 | The benchmark cost that the technical support provider charges to provide technical services for carbon reduction in the service area. | |

| Rt | Incremental benchmark gains resulting from the technical support provider’s “proactive cooperation” | |

| Q | The benchmark revenue for the carbon reduction technology service area provided by the technical support provider at the high-speed service area. | |

| α | The coefficient of cost reduction for enterprises through “active cooperation” with the technical support providers |

| Government Choice | Selection of Service Area Operating Companies | Selection of Technical Support Provider | Government Revenue | Revenue of Service Area Operating Enterprises | Revenue for the Technical Support Provider |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strict regulation (x) | Proactive carbon reduction (y) | Active cooperation (z) | Bg-Cg3-Cg1-S-M | kRe + V + S-Ce4 − (1 − α)(Ce1 + Ce3)-L | Q + Rtβ + M-Ct3-Ct1 |

| Passive cooperation (1 − z) | Bg-Cg3-Cg1-S | kRe + V+S-Ce4-(Ce1 + Ce3)-L | Q-Ct3-Ct2 | ||

| Passive carbon reduction (1 − y) | Active cooperation (z) | Bg + F-Cg3-Cg1-M | −Ce4-Ce2-F-L | Q + Rt + M-Ct3-Ct1 | |

| Passive cooperation (1 − z) | Bg + F-Cg3-Cg1 | −Ce4-Ce2-F-L | Q-Ct3-Ct2 | ||

| Weak regulation (1 − x) | Proactive carbon reduction (y) | Active cooperation (z) | −Cg3-Cg2 | kRe + V-Ce4-(1 − α)(Ce1 + Ce3)-L | Q + Rtβ + M-Ct3-Ct1 |

| Passive cooperation (1 − z) | −Cg3-Cg2 | kRe + V-Ce4-(Ce1 + Ce3)-L | Q-Ct3-Ct2 | ||

| Passive carbon reduction (1 − y) | Active cooperation (z) | −Cg3-Cg2 | −Ce4-Ce2-L | Q + Rt-Ct3-Ct1 | |

| Passive cooperation (1 − z) | −Cg3-Cg2 | −Ce4-Ce2-L | Q-Ct3-Ct2 |

| Equilibrium Point | Eigenvalue 1 | Eigenvalue 2 | Eigenvalue 3 | Stable Condition | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expression | +/− | Expression | +/− | Expression | +/− | ||

| E1 (0,0,0) | Bg-Cg1 + Cg2 + F | Uncertain | Ce2-Ce1-Ce3 + kRe + V | Uncertain | Ct1-Ct2-Rt | Uncertain | When Bg + Cg2 + F < Cg1 and Ce2 + kRe + V < Ce1 + Ce3 and Ct1 < Ct2 + Rt, ESS |

| E2 (0,1,0) | Bg-Cg1 + Cg2-S | Uncertain | Ce1-Ce2 + Ce3-kRe-V | Uncertain | Ct2-Ct1 + βRt | Uncertain | When Bg + Cg2 < Cg1 + S and Ce1 + Ce3 < Ce2 + Re*k +V and Ct2 + βRt < Ct1, ESS |

| E3 (0,0,1) | Bg-Cg1 + Cg2 + F-M | Uncertain | Ce2-Ce1-Ce3 + kRe + V+α(Ce1 + Ce3) | Uncertain | Ct1-Ct2-Rt | Uncertain | When Bg + Cg2 + F < Cg1 + M and Ce2 + kRe + V < (1 − α)(Ce1 + Ce3) and Ct1 < Ct2 + Rt, ESS |

| E4 (0,1,1) | Bg-Cg1 + Cg2-M-S | Uncertain | Ce1-Ce2 + Ce3-kRe-V-α(Ce1 + Ce3) | Uncertain | Ct1-Ct2-βRt | Uncertain | When Bg + Cg2 < Cg1 + M+S and (1 − α)(Ce1 + Ce3) < Ce2 + kRe + V and Ct1 < Ct2 + βRt, ESS |

| E5 (1,0,0) | Cg1-Bg-Cg2-F | − | Ce2-Ce1-Ce3 + F+kRe + S+V | Uncertain | Ct2-Ct1 + M+Rt | Uncertain | When Ce2 + F+kRe + S+V < Ce1 + Ce3 and Ct2 + M+Rt < Ct1, ESS |

| E6 (1,1,0) | Cg1-Bg-Cg2 + S | Uncertain | Ce1-Ce2 + Ce3-F-kRe-S-V | Uncertain | Ct2-Ct1 + M+βRt | Uncertain | When Cg1 + S < Bg + Cg2 and Ce1 + Ce3 < Ce2 + F+kRe + S+V and Ct2 + M+βRt < Ct1, ESS |

| E7 (1,0,1) | Cg1-Bg-Cg2-F + M | Uncertain | Ce2-Ce1-Ce3 + F+kRe + S+V + α(Ce1 + Ce3) | + | Ct1-Ct2-M-Rt | Uncertain | Instability point or saddle point |

| E8 (1,1,1) | Cg1-Bg-Cg2 + M+S | Uncertain | Ce1-Ce2 + Ce3-F-kRe-S-V-α(Ce1 + Ce3) | − | Ct1-Ct2-M-βRt | Uncertain | When Cg1 + M+S < Bg + Cg2 and Ct1 < Ct2 + M+βRt, ESS |

| Cg1 | Cg2 | S | M | Bg | F | Ce1 | Ce2 | Ce3 | Re | k | V | Ct1 | Ct2 | Rt | α | β |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 8 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 5 | 3 | 0.5 | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bai, H.; Qi, D. Tripartite Evolutionary Game for Carbon Reduction in Highway Service Areas: Evidence from Xinjiang, China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10145. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210145

Bai H, Qi D. Tripartite Evolutionary Game for Carbon Reduction in Highway Service Areas: Evidence from Xinjiang, China. Sustainability. 2025; 17(22):10145. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210145

Chicago/Turabian StyleBai, Huiru, and Dianwei Qi. 2025. "Tripartite Evolutionary Game for Carbon Reduction in Highway Service Areas: Evidence from Xinjiang, China" Sustainability 17, no. 22: 10145. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210145

APA StyleBai, H., & Qi, D. (2025). Tripartite Evolutionary Game for Carbon Reduction in Highway Service Areas: Evidence from Xinjiang, China. Sustainability, 17(22), 10145. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210145