How Can Enterprises’ Green Innovation Persist? A Study Based on Explainable Machine Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Framework and Theoretical Analysis

2.1. Strategy Tripod Framework

2.2. Resource Factors and Persistence of Enterprise Green Innovation

2.3. Industry Factors and Persistence of Enterprise Green Innovation

2.4. Institution Factors and Persistence of Enterprise Green Innovation

3. Research Design

3.1. Machine Learning Models

3.1.1. Multiple Linear Regression (MLR)

3.1.2. Elastic Net (E-Net)

3.1.3. Support Vector Machine (SVM)

3.1.4. Decision Tree (DT)

3.1.5. Random Forest (RF)

3.1.6. Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT)

3.1.7. eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost)

3.2. Hyper-Parameter Optimization

3.3. Model Evaluation

3.4. SHAP

4. Data Source and Variable Selection

4.1. Data Source

4.2. Variable Definition

4.2.1. Label Variable

4.2.2. Feature Variable

4.3. Descriptive Statistics

5. Analysis of Empirical Results

5.1. Performance Measure of Machine Learning Models

5.2. Analysis Based on the SHAP

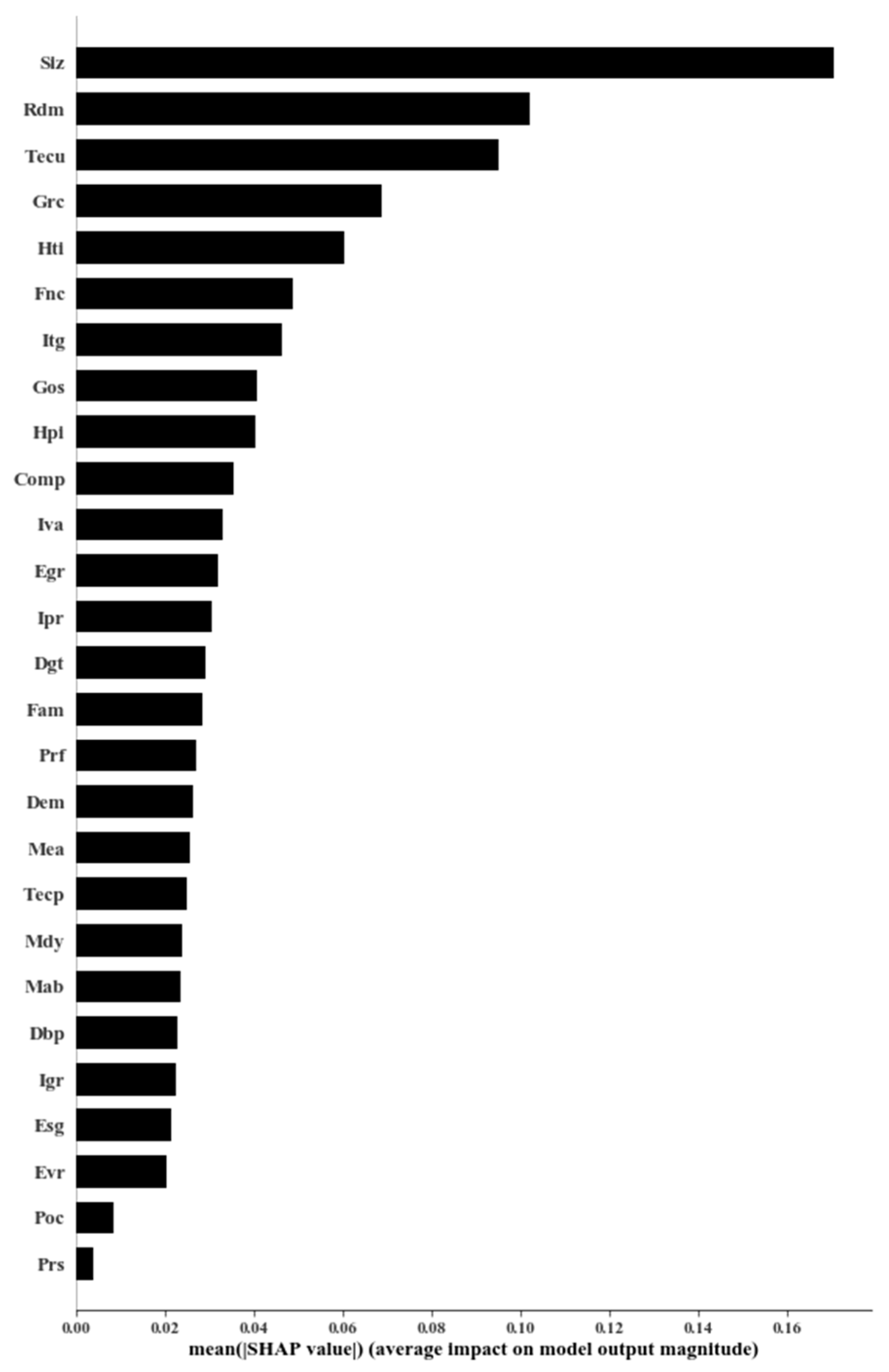

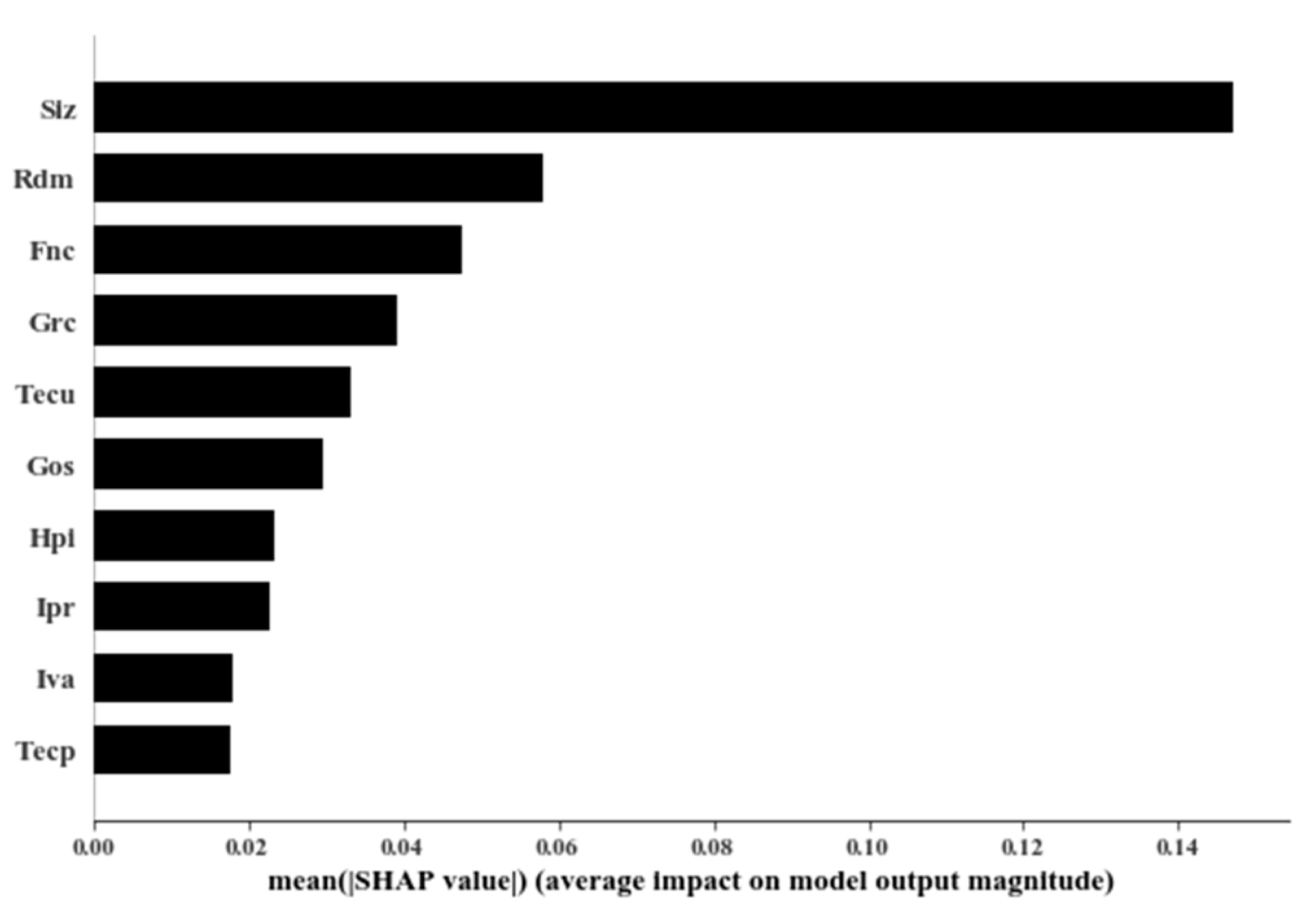

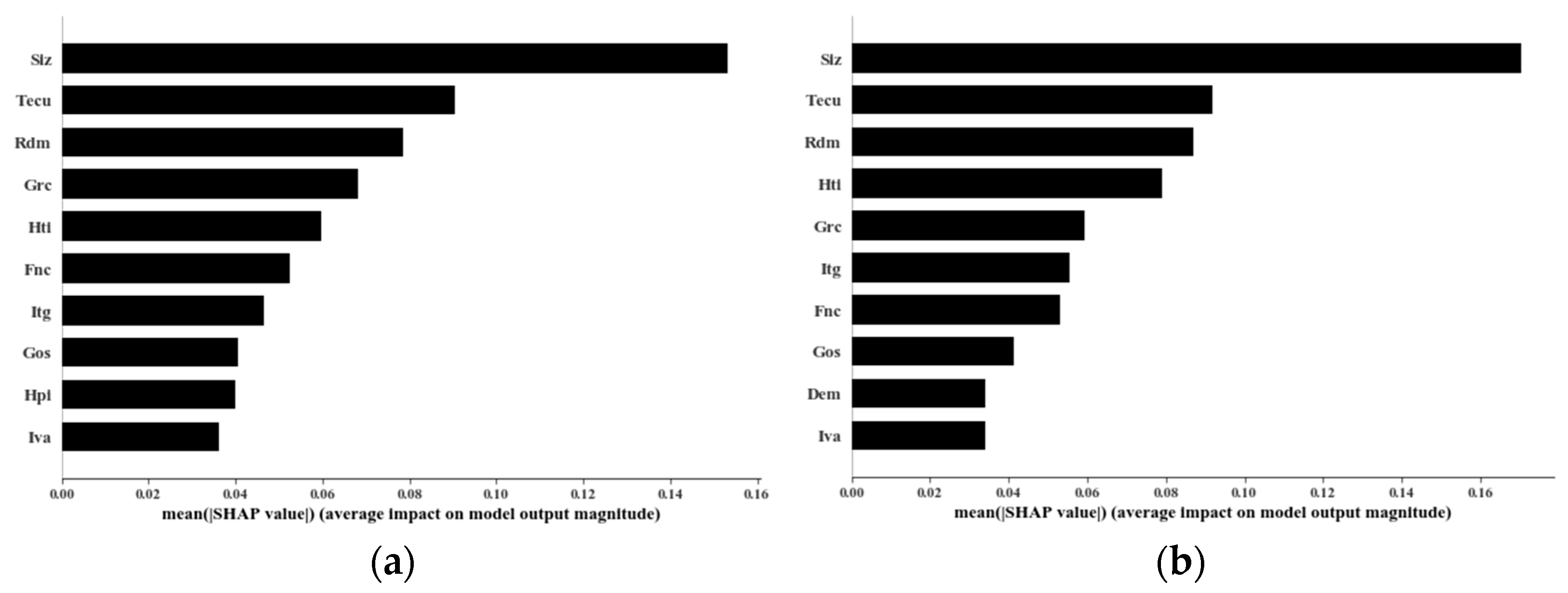

5.2.1. Feature Importance Analysis

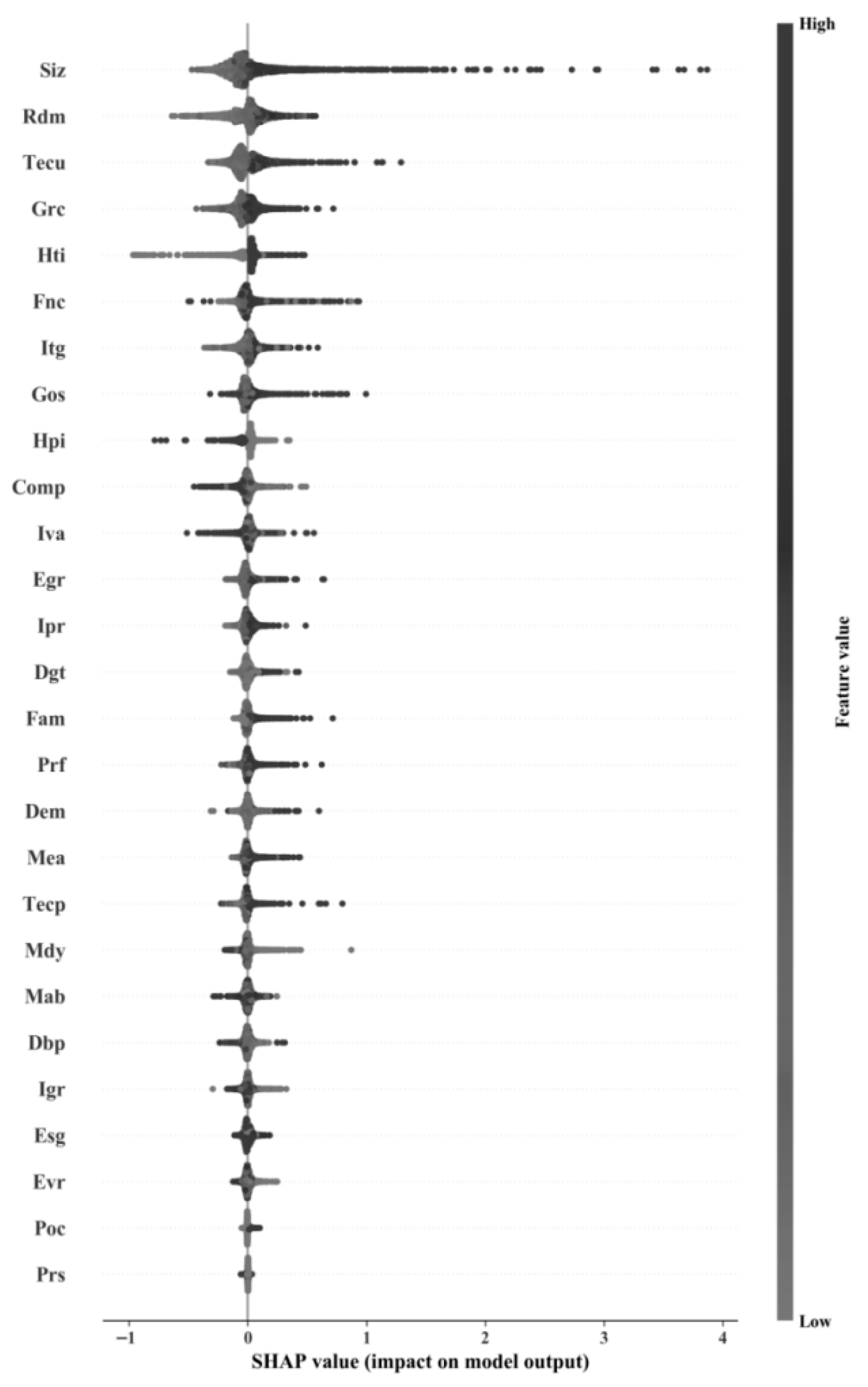

5.2.2. Feature Effect Direction Analysis

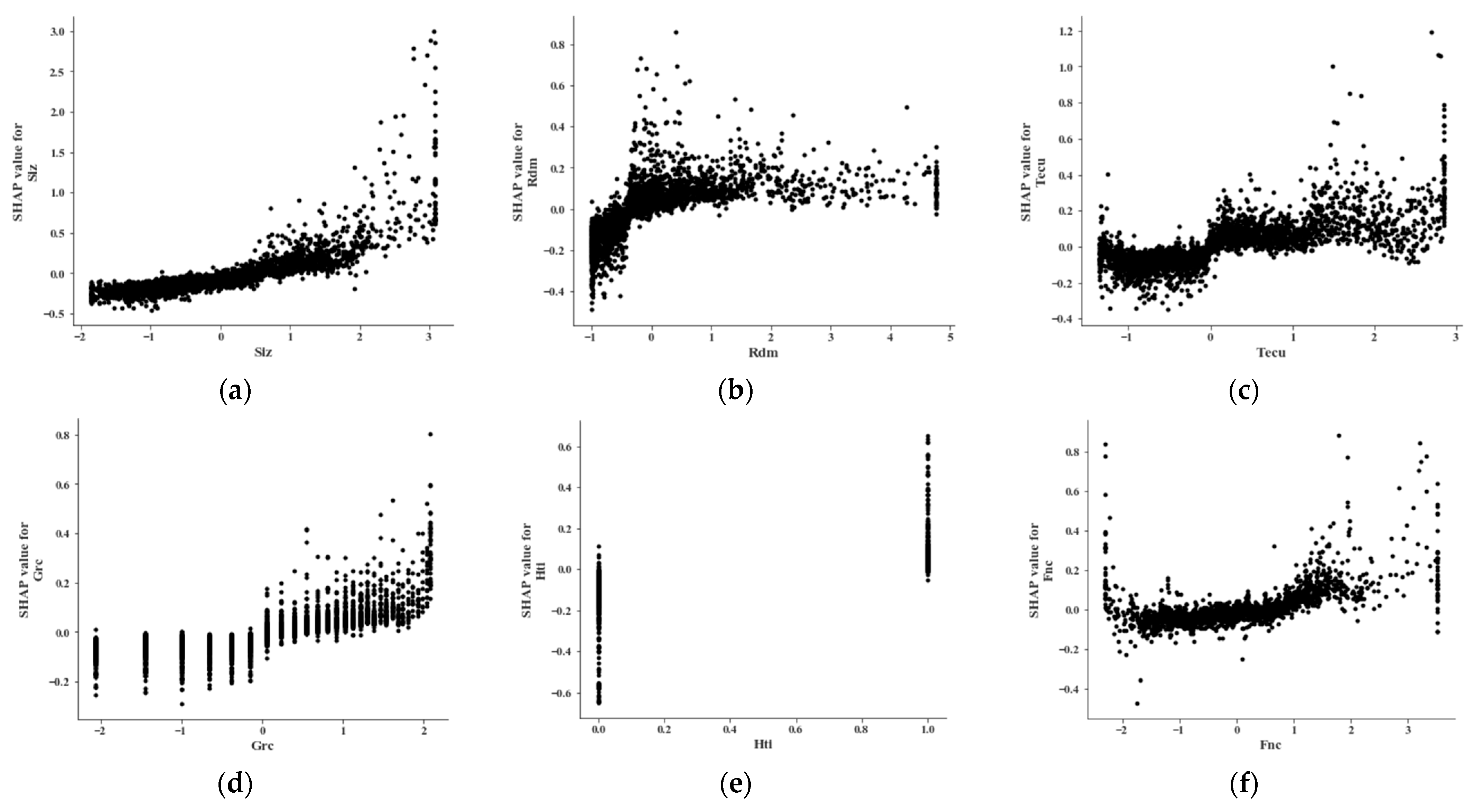

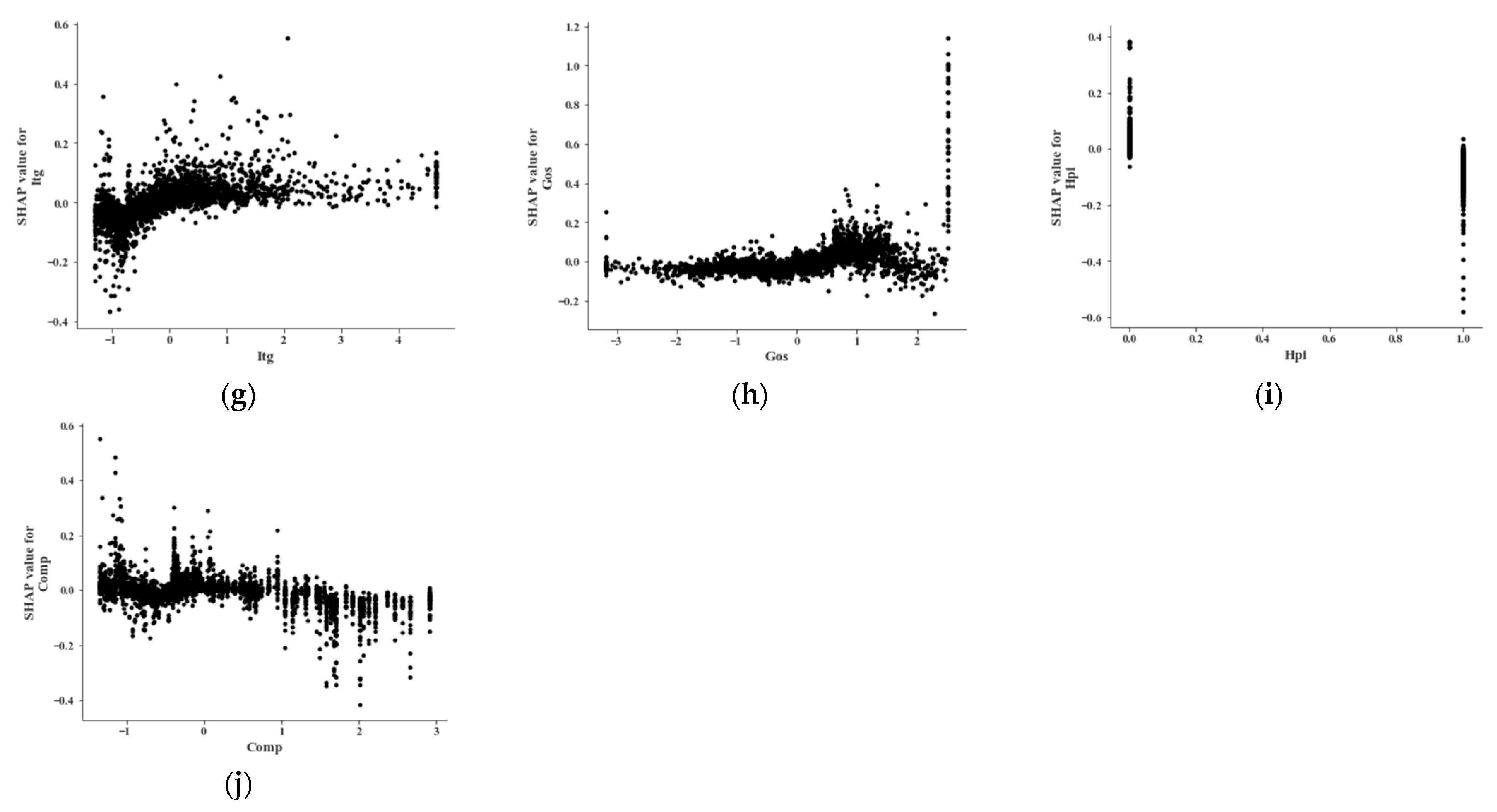

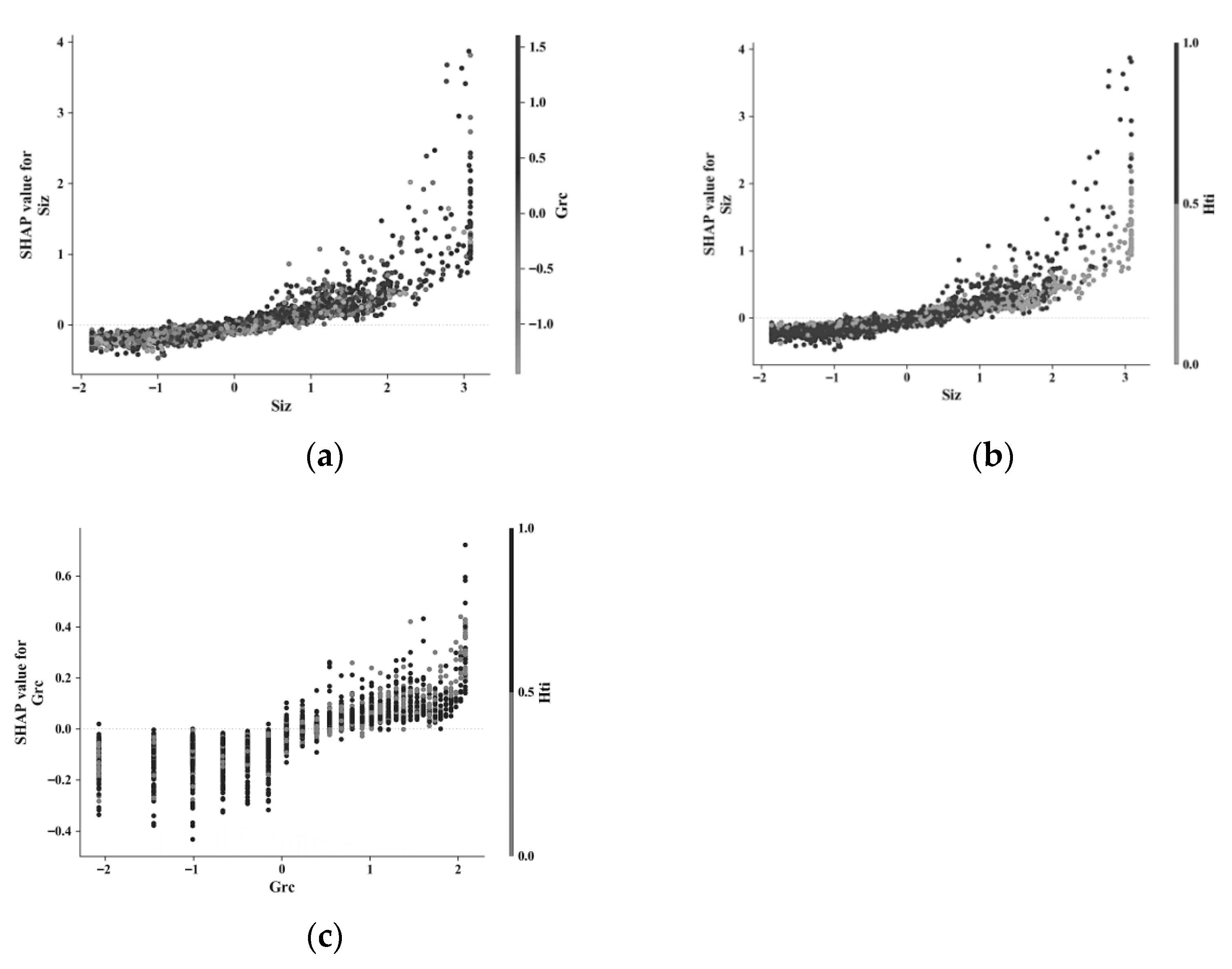

5.2.3. Feature Dependency Analysis

5.2.4. Feature Interaction Analysis

5.2.5. Local Interpretation Analysis

5.3. Robustness Test

5.3.1. Substituting Measurement of Label Variable

5.3.2. Adjusting the Sample Split Ratio

5.4. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Implications

6.1. Conclusions

- (1)

- Persistent green innovation has emerged as a central pathway for enterprises to address environmental challenges and achieve sustainable development [3]. However, there is significant variation in the persistence of green innovation among enterprises, and a majority of them struggle to sustain their green innovation efforts.

- (2)

- 27 feature variables influencing the persistence of enterprise green innovation have been identified within the strategy tripod framework. After empirical testing, we found that some variables play important roles in influencing the persistence of enterprise green innovation. Specifically, enterprise size, R&D investment, and technological utilization capability are identified as key determinants. Notably, enterprise size, high-tech industry, and enterprise green culture are the most significant variables within the resource, industry, and institution dimension. R&D investment, technological utilization capability, enterprise green culture, financing capacity, and integration capability exhibit non-linear positive effects on the persistence of green innovation.

- (3)

- Among seven machine learning models evaluated, ensemble models outperform traditional single models. Based on this result, an XGBoost-based prediction model for enterprise green innovation persistence has been developed.

6.2. Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Albloushi, B.; Alharmoodi, A.; Jabeen, F.; Mehmood, K.; Farouk, S. Total quality management practices and corporate sustainable development in manufacturing companies: The mediating role of green innovation. Manag. Res. Rev. 2023, 46, 20–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Chen, X. Can digital finance alleviate the adverse effects of short-term loans for long-term investments on corporate sustainable green innovation? China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2024, 34, 123–131. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Gao, Y. Local government environmental protection concern and corporate green sustainable innovation levels. Syst. Eng. Theory Pract. 2025, 45, 17–35. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, F.; FAN, X. TMT cognition, industrial regulation and firm innovation persistence. Sci. Res. Manag. 2022, 43, 173–181. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, R.; Hou, M.; Jing, R.; Bauer, A.; Wu, M. The impact of national big data pilot zones on the persistence of green innovation: A moderating perspective based on green finance. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, H.; Zhao, K.; Liu, Y. ESG performance and the persistence of green innovation: Empirical evidence from Chinese manufacturing enterprises. Multinatl. Bus. Rev. 2025, 33, 268–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Cai, S.; Ma, W.; Wang, Y. How government green procurement enhances the sustainability of corporate green innovation. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 2025, 42, 110–120. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, R.; Liu, R. The impact of green finance on persistence of green innovation at firm-level: A moderating perspective based on environmental regulation intensity. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 62, 105274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zheng, C.; Hong, Y. How can machine learning empower management research? A domestic-foreign frontier review and future prospects. J. Manag. World. 2023, 39, 191–216. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, S.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, J. Chairman and CEO value differences and firm innovation: Empirical evidence from a machine learning approach. China Soft Sci. 2024, S1, 203–222. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, M.; Liu, M.; Zhao, X. What kind of ‘‘navigator’’ does enterprise digital transformation need: An investigation based on machine learning methods. China Soft Sci. 2024, 5, 173–187. [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In Proceedings of the NIPS’17: Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.; Wang, R.; Fang, M. Mapping green innovation with machine learning: Evidence from China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 200, 123107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. The contributions of industrial organization to strategic management. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1981, 6, 609–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.W. Towards an institution-based view of business strategy. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2002, 19, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.W.; Wang, D.Y.L.; Jiang, Y. An institution-based view of international business strategy: A focus on emerging economies. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2008, 39, 920–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Wang, L.; Zheng, T.; Wu, W. What types of business environment fosters the emergence of more specialized and sophisticated ‘‘little giant’’ enterprises?—An empirical study based on the TOE framework and configuration adaptation theory. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2024, 3, 1557–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhang, J.; Chen, W. The configuration effect of factors influencing the performance of intelligent transformation in manufacturing enterprises: Based on AMO theoretical analysis framework. Sci. Technol. Manag. Res. 2024, 10, 143–152. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; He, J.; Chen, L. Will interlocking directors with green experience promote quantity increase and quality improvement of enterprise green innovation. China Ind. Econ. 2023, 10, 155–173. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.; Zhai, Y. Does profitability affect companies’ R&D decision-making? An empirical research of Chinese listed manufacturing companies. Manag. Rev. 2021, 33, 68–80. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C.; Wu, X.; Zhang, D.; Chen, S.; Zhao, J. Demand for green finance: Resolving financing constraints on green innovation in China. Energy Policy 2021, 153, 112255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Sun, H.; Xiao, H.; Xin, L. ‘‘Be cautious’’ or ‘‘Win in danger’’? Environmental policy uncertainty and green innovation of pollution-intensive enterprises. Ind. Econ. Res. 2021, 2, 30–41+127. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, B.; Cao, X. Do corporate social responsibility practices contribute to green innovation? The mediating role of green dynamic capability. Technol. Soc. 2022, 68, 101868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Tan, Y.; Yang, X. Firm size and innovation sustainability: A dual-regulation based on firmness and flexibility. Soft Sci. 2024, 38, 101–107+124. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y.; Song, S.; Jiao, J.; Yang, R. The impacts of government R&D subsidies on green innovation: Evidence from Chinese energy-intensive firms. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 233, 819–829. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, N. The empirical study on influence of enterprise informatization on innovation capability in resource-oriented regions--Based on resource view theory. Soft Sci. 2017, 31, 44–48. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Liu, X.; Zhang, L.; Cheng, W. Does digitalization promote green technology innovation of resource-based enterprises? Stud. Sci. Sci. 2022, 40, 332–344. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Yao, S. Organizational capital, stakeholder pressure and green innovation of enterprises. Sci. Res. Manag. 2023, 44, 71–81. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Sun, W. Digital Business Models, Dynamic Capabilities, and Enterprise Innovation Performance. Econ. Rev. J. 2024, 8, 106–117. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, J. Digital economy, peer influence, and persistent green innovation of firms: A mixed embeddedness perspective. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 13883–13896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ran, Q.; Yang, X.; Ye, L. Digitalization and continuous green innovation: Evidence from A-share listed industrial companies. J. Soochow Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2024, 45, 119–131. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Gao, S. Research on relationships between environmental uncertainty, organizational slack and original innovation. Manag. Rev. 2014, 26, 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, H.; Yu, B.; Wang, K. Environmental uncertainty, slack resources and corporate strategic change. Sci. Sci. Manag. S.& T. 2018, 39, 92–105. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Zhao, T. Whether Industry Growth Reduces Corporate Tax Burden: Evidence from Chinese Listed Companies. J. Zhongnan Univ. Econ. Law 2018, 2, 14–24+158. [Google Scholar]

- Raymond, W.; Mohnen, P.; Palm, F.; Loeff, S.S. Persistence of innovation in Dutch manufacturing: Is it spurious? Rev. Econ. Stat. 2010, 92, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Tao, F. Does downstream digitalization lead to green innovation in upstream enterprises--Based on the perspective of supply chain spillover. South China J. Econ. 2024, 5, 132–149. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Z.; Tang, X.; Liu, X. Can you have your cake and eat it too?—Market competition, government subsidies and enterprise R&D. World Econ. Pap. 2018, 4, 101–117. [Google Scholar]

- Du, K.; Chen, G.; Liang, J. Heterogeneous environmental regulation, environmental dual strategy and green technology innovation. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 2023, 40, 130–140. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Rasiah, R. Can ESG disclosure stimulate corporations’ sustainable green innovation efforts? Evidence from China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, X.; Liu, C.; Yang, M. Who is financing corporate green innovation? Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2022, 78, 321–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, Z. Institutional advantage transfer: Political connection and business green innovation. Financ. Econ. 2020, 9, 108–120. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, F.; Huang, Y.; Wang, J.; Shang, M. Entering the chamber of orchids: Corporate green culture and green innovation. Foreign Econ. Manag. 2025, 47, 137–152. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Chen, J.; Ling, H. Media attention, environmental policy uncertainty and firm’s green technology: Empirical evidence from Chinese A-share listed firms. J. Ind. Eng. Eng. Manag. 2023, 37, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, X.; Lin, L.; Xiao, B.; Yu, H. Re-exploration of small and micro enterprises’ default characteristics based on machine learning models with SHAP. Chin. J. Manag. Sci. 2024, 32, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Wei, S. Can overseas M&A promote the green innovation level of enterprises? Foreign Econ. Manag. 2024, 46, 106–121. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Zhou, J.; Huang, J. How does the generosity of enterprises come? Evidence from machine learning. J. Financ. Econ. 2023, 49, 153–169. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, C.; Shi, X.; Zhang, Y. Corporate Innovation Culture and Audit Pricing. Audit. Res. 2023, 6, 123–135. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Qi, N.; Meng, Q. Technology Integration Capability, Green Patent Quality and Firms’ Sustainable Innovation. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 2023, 40, 11–21. [Google Scholar]

| Theoretical Framework | Main Consideration | Author |

|---|---|---|

| Resource-based view | The specific resources and capabilities possessed by an organization determine its strategic decisions. | Barney [15] |

| Industry-based view | The competitive advantage of an enterprise is derived from the conjunction of industry structure and the enterprise’s specific positioning within that industry. | Porter [14] |

| Institution-based view | Legitimacy and other normative institutional factors constrain an enterprise’s selection of innovation strategies. | Peng et al. [16] |

| Strategy tripod framework | Factors at the resource, industrial, and institutional levels are interdependent and interact with one another, collectively shaping an enterprise’s innovation strategic choices. | Peng et al. [17] |

| Model | Parameters | Value Range |

|---|---|---|

| E-Net | alpha | 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, 100 |

| L1-ratio | 0.1, 0.5, 0.7, 0.9 | |

| SVM | C | 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10 |

| Gamma | 0.01, 0.1, 1 | |

| DT | max_depth | 2, 5, 7, 10 |

| min_samples_split | 3, 5, 7, 9 | |

| min_samples_leaf | 2, 5, 8 | |

| RF | n_estimators | 100, 200, 300 |

| max_depth | 2, 5, 7, 10 | |

| min_samples_split | 3, 5, 7, 9 | |

| min_samples_leaf | 2, 5, 8 | |

| GBDT | n_estimators | 100, 200, 300 |

| max_depth | 2, 5, 7, 10 | |

| min_samples_split | 3, 5, 7, 9 | |

| min_samples_leaf | 2, 5, 8 | |

| Learning_rate | 0.01, 0.1, 0.5, 1.0 | |

| Subsample | 0.5, 0.8, 1.0 | |

| XGBoost | max_depth | 2, 5, 7, 10 |

| Learning_rate | 0.01, 0.1, 0.5, 1.0 | |

| Subsample | 0.5, 0.8, 1.0 | |

| min_child_weight | 3, 6, 9, 12 |

| Variable Type | Name of Variables | Abbreviation | Definition of Variables |

|---|---|---|---|

| Label Variable | Persistence of Green Innovation | Oip | Green patent year-over-year growth rate × R&D output scale |

| Feature Variable | Profitability | Prf | Net profit/Total assets |

| Financing Capacity | Fnc | 1/SA Index | |

| Growth Potential | Egr | Increase in operating revenue/Total operating revenue of the previous year | |

| Debt-Paying Capacity | Dbp | Total current assets/Total current liabilities | |

| Enterprise Fame | Fam | Ln (Number of analysts tracking the enterprise + 1) | |

| Enterprise Size | Siz | Ln (Total assets) | |

| R&D Investment | Rdm | R&D expenditure/Operating revenue | |

| Integration Capability | Itg | Total asset turnover ratio | |

| Technology Utilizing Capability | Tecu | Employees with bachelor’s degree or above/Total employees | |

| Technology Perception Capability | Tecp | Executives with technical background/Total executives | |

| Data Processing Capability | Dgt | Digital intangible assets/Total intangible assets | |

| Industry Abundance | Mab | Measurement method refers to Fu et al. [34] | |

| Industry Dynamism | Mdy | Measurement method refers to Fu et al. [34] | |

| Industry Growth | Igr | Industry Tobin’s Q | |

| Heavily Polluting Industry | Hpi | Heavy polluting industry, 1; otherwise, 0 | |

| High Tech industry | Hti | High tech industry, 1; otherwise, 0 | |

| Market Demand | Dem | Cost of sales/Average inventory balance | |

| Market Competition | Comp | 1/HHI | |

| Environmental Regulation | Evr | Ln(Number of local environmental regulations) | |

| ESG Rating | Esg | Huazheng ESG rating | |

| Intellectual Property Protection | Ipr | Ln(Number of concluded patent infringement cases in the region) | |

| Government Subsidy | Gos | Ln(Government subsidies) | |

| Ownership Structure | Prs | State-owned enterprise, 1; otherwise, 0 | |

| Political Connection | Poc | Current chairman or general manager has political background, 1; otherwise, 0 | |

| Enterprise Green Culture | Grc | Word frequency of environmental terms in executive sections of enterprise’s annual reports | |

| Investor Attention | Iva | Institutional shareholding/Total shares | |

| Media Attention | Mea | Ln(Number of online + News reports) |

| Variable | Mean Value | Standard Deviation | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oip | 7.079 | 22.509 | 0.000 | 159.853 |

| Prf | 0.028 | 0.070 | −0.313 | 0.196 |

| Fnc | 0.258 | 0.164 | 0.220 | 0.316 |

| Egr | 0.292 | 0.670 | −0.681 | 4.193 |

| Dbp | 2.102 | 1.705 | 0.359 | 10.715 |

| Fam | 7.090 | 9.913 | 0.000 | 45.000 |

| Siz | 22.480 | 1.264 | 20.129 | 26.381 |

| Rdm | 4.657 | 4.581 | 0.028 | 26.530 |

| Itg | 0.625 | 0.397 | 0.108 | 2.479 |

| Tecu | 29.622 | 20.568 | 1.723 | 88.384 |

| Tecp | 0.313 | 0.230 | 0.000 | 0.857 |

| Dgt | 0.091 | 0.200 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Mab | 0.113 | 0.147 | −0.276 | 0.538 |

| Mdy | 0.049 | 0.042 | 0.005 | 0.239 |

| Igr | 1.301 | 0.769 | 0.133 | 4.667 |

| Hpi | 0.296 | 0.457 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Hti | 0.678 | 0.467 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Dem | 9.733 | 28.525 | 0.333 | 243.890 |

| Comp | 14.142 | 9.386 | 1.482 | 41.514 |

| Evr | 0.951 | 0.227 | 0.518 | 1.692 |

| Esg | 4.339 | 1.910 | 1.000 | 6.000 |

| Ipr | 6.786 | 1.860 | 1.609 | 9.763 |

| Gos | 16.601 | 1.511 | 11.829 | 20.419 |

| Prs | 0.088 | 0.284 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Poc | 0.273 | 0.445 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Grc | 2.037 | 0.670 | 0.000 | 3.401 |

| Iva | 42.491 | 23.988 | 0.341 | 90.211 |

| Mea | 4.541 | 1.171 | 1.099 | 7.645 |

| MLR | E-Net | SVM | DT | RF | GBDT | XGBoost | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | 0.161 (7) | 0.158 (6) | 0.314 (4) | 0.269 (5) | 0.423 (3) | 0.508 (2) | 0.521 (1) |

| MAE | 0.480 (7) | 0.470 (6) | 0.325 (4) | 0.382 (5) | 0.358 (3) | 0.340 (2) | 0.336 (1) |

| RMSE | 0.977 (6) | 0.978 (7) | 0.883 (4) | 0.911 (5) | 0.810 (3) | 0.747 (2) | 0.738 (1) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, H.; Wang, J.; Yuan, Y. How Can Enterprises’ Green Innovation Persist? A Study Based on Explainable Machine Learning. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10071. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210071

Zhao H, Wang J, Yuan Y. How Can Enterprises’ Green Innovation Persist? A Study Based on Explainable Machine Learning. Sustainability. 2025; 17(22):10071. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210071

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Huaping, Jian Wang, and Yuan Yuan. 2025. "How Can Enterprises’ Green Innovation Persist? A Study Based on Explainable Machine Learning" Sustainability 17, no. 22: 10071. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210071

APA StyleZhao, H., Wang, J., & Yuan, Y. (2025). How Can Enterprises’ Green Innovation Persist? A Study Based on Explainable Machine Learning. Sustainability, 17(22), 10071. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210071