Unveiling the Synergistic Effects in Graphene-Based Composites as a New Strategy for High Performance and Sustainable Material Development: A Critical Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Synergistic Effects Observed in Graphene-Based Composites

2.1. Antimicrobial Graphene-Based Composites (AGCs)

2.1.1. AGCs Revealing Synergistic Effects for Clinic Application

2.1.2. AGCs Revealing Synergistic Effects for Water Purification

2.1.3. AGCs Revealing Synergistic Effects for Packaging Development

2.1.4. AGCs Revealing Synergistic Effects on Other Antimicrobial Applications

| Graphene Materials | Synergistic Components | Target Microorganisms | Synergistic Antimicrobial Capacity | Synergistic Mechanisms | Applications | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rGO | Peptide (Cathelicidin-2) | Escherichia coli (E. coli) | The rGO-peptide complex resulted in 21.8 mm and 16.5 mm inhibition zones compared with 13.3 mm with rGO alone. | Unique surface property | Clinic application | Joshi et al., 2020 [25] |

| GO | ZnO nanoparticles | E. coli Bacillus subtilis (B. subtilis) | ZnO/GO inactivated >80% of E. coli and 90% of B. subtilis, while it only inactivated 15% of E. coli and 50% of B. subtilis in the same condition with ZnO or GO alone. | Cumulative effect | Clinic application | Zhong et al., 2018 [36] |

| GO | Polyhexamethylene guanidine hydrochloride (PHMG)/thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) | E. coli Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) | GO-PHMG/TPU inactivated 28.21% of E. coli and 30.88% of S. aureus even after 30 days, while PHMG/TPU inactivated 5.22% and 4.56% and GO/TPU inactivated 71.26% for E. coli and 76.96% for S. aureus. | N/A | Clinic application | Jian et al., 2020 [39] |

| GO | Quaternary ammonium salts (QAS) | E. coli S. aureus | GO-QAS at 200 μg/mL almost completely killed both E. coli and S. aureus, while GO and QAS caused approximately 87% and 92% cell death for S. aureus and 75% and 88% cell death for E. coli, respectively. | Cumulative effect | Clinic application | Liu et al., 2018 [44] |

| GO | Curcumin | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) | Curcumin/GO showed efficacy against MRSA at a concentration below 0.002 mg/mL, while MIC of GO is 37.5 mg/mL and MIC of curcumin alone against MRSA ranges from 125 to 256 mg/mL. | Unique surface property | Clinic application | Bugli et al., 2018 [48] |

| rGO | Silver nanoparticles | S. aureus Proteus mirabilis (P. mirabilis) | rGO-nAg killed almost 100% of S. aureus and P. mirabilis within 2–2.5 h compared to 4 h with rGO or nAg alone. | Cumulative effect | Clinic application | Prasad et al., 2017 [33] |

| GO | AgNPs/polydopamine (PDA)/Ti | E. coli S. aureus | PDA/GO/AgNPs-Ti resulted in 99.8% and 99.6% effectiveness against E. coli and S. aureus, which is significantly higher than that of pure Ti and PDA/GO-Ti (<20%) | Cumulative effect | Clinic application | Xie et al., 2017 [47] |

| GO | Gold nanoclusters | S. aureus | GO and AuNCs resulted in 17% and <5% bacterial inactivation rates, compared with 34% for the GO-AuNP composite. | Cumulative effect | Clinic application | Zheng et al., 2019 [65] |

| rGO (montmorillonite modified, MTT) | Copper nanoparticles | E. coli S. aureus | MMT-rGO-CuNPs resulted in a >99% reduction in E. coli and S. aureus, compared to individual treatments which achieved no more than a 97% killing rate. | Unique surface property | Clinic application | Yan et al., 2019 [66] |

| GO | Red phosphorus (RP) | E. coli S. aureus | Ti-RP/GO resulted in >98% and >99.9% reduction under simulated sunlight and 808 nm for S. aureus and E. coli, compared with a 42% and 79% bacterial reduction caused by Ti-GO and Ti-RP alone. | Cumulative effect | Clinic application | Zhang et al., 2020 [67] |

| Graphene quantum dots (GQD) | AgNPs | E. coli S. aureus | GQD-AgNP resulted in >90% reduction for both S. aureus and E. coli under 450 nm, while GQD alone caused less than 30% and 40% reduction. | Cumulative effect | Clinic application | Mei et al., 2020 [68] |

| GO | Ni colloidal nanocrystal cluster (NCNC) | E. coli S. aureus | GO/NCNC resulted in 99.5% and 100% inhibition against S. aureus and E. coli, respectively, compared to 70–82% inhibition for individual components. | Cumulative effect | Clinic application | Du et al., 2022 [69] |

| GO | PVA (polyvinyl alcohol) | E. coli S. aureus | GO/PVA led to over 97% and 99% reduction in S. aureus and E. coli, respectively, under dual-wavelength light, compared to around 80% and 50% reduction by GO/PVA. | Cumulative effect | Clinic application | Li et al., 2021 [45] |

| rGO | pi-conjugated molecule containing five aromatic rings and two side-linked quaternary ammonium groups (piQA) | E. coli S. aureus | piQA-rGO rapidly removed most bacteria within 110 s compared to the inactivation time of piQA (10 min), while rGO resulted in just under a 30% loss of viability. | Unique surface property | Water purification | Wang et al., 2019 [56] |

| GO | ε-poly-L-lysine (PLL) | E. coli B. subtilis | GO-PLL retained 61% of E. coli and 53% of B. subtilis, which is significantly higher than the retention rates of 25% and 5% for the GO sponge without PLL, respectively. | Unique surface property | Water purification | Filina et al., 2019 [57] |

| rGO | Ag-AgBr nanoparticles | E. coli K12 | Ag-AgBr/0.5% rGO resulted in 7 log reductions within 10 min, comparatively, Ag-AgBr and AgBr-rGO resulted in 7 and 5.5 log reductions in 40 min. | Cumulative effect | Water purification | Xia et al., 2016 [70] |

| GO | AgNP(silver nanoparticles) | E. coli S. Typhi S. aureus | The diameter of the highest inhibition zone for S. typhi was measured as 11.75 ± 0.96 mm. S. aureus: this value was measured as 9.88 ± 0.25 mm; E coli: this value was measured as 10.00 ± 0.41 mm, while GOQD used as negative control did not show any antibacterial activity | N/A | Water purification | Büşra et al., 2024 [71] |

| rGO | Starch/polyiodide | E. coli S. aureus | Starch/rGO/polyiodide nanocomposite resulted in inhibition zones of 22.2 ± 2.2 mm and 20.2 ± 0.9 mm for E. coli and S. aureus, respectively, whereas Starch/rGO alone did not exhibit any inhibition. | N/A | Antimicrobial food packaging | Narayanan et al., 2021 [60] |

| rGO | Pd-ZnO | P. aeruginosa K. pneumonia | Pd-RGO-ZnO exhibited antibacterial activity against a panel of human pathogens, including P. aeruginosa and K. pneumonia. | Unique surface property | Antimicrobial food packaging | Rajeswari et al., 2020 [61] |

| GO | Curcumin | Respiratory syncytial virus | Curcumin/GO resulted in 4 log reduction in viral titers, which was significantly higher than that caused by the individual components. | Cumulative effects | Other antimicrobial applications | Yang et al., 2017 [72] |

| GO | Polymeric N-halamine (PSPH) | E. coli S. aureus | GO-PSPH-Cl resulted in a 6.7 log reduction in S. aureus and an 8.1 log reduction in E. coli. Comparatively, GO and GO-PSPH resulted in <1.7 log and <2.7 log reduction of S. aureus and E. coli under the same condition. | Cumulative effects | Other antimicrobial applications | Pan et al., 2017 [73] |

2.2. Medicinal Graphene-Based Composites for Cancer Therapy

2.3. Graphene-Based Catalysts

2.3.1. Graphene-Based Catalysts Revealing Synergistic Effects Through Photocatalysis

2.3.2. Graphene-Based Catalysts Revealing Synergistic Effects Through Electrocatalysis

2.3.3. Graphene-Based Catalysts Revealing Synergistic Effects Through Chemical Catalysis

| Graphene Composites | Synergistic Components | Reaction | Synergistic Catalytic Capacity | Synergistic Mechanisms | Applications | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrogen-doped graphene (NG) | FexCoy/perylene diimide (PDI) | Degradation of Bisphenol A (BPA) | Fe0.2Co0.8-NG/PDI degraded 100% of BPA, while NG/PDI, Co-NG/PDI, and Fe-NG/PDI degraded only 50%, 65%, and 90% of BPA, respectively. | Cumulative effect | Photocatalysis | Liu et al., 2023 [91] |

| Graphene | Fe/TiO2 | Degradation of methyl Orange | Graphene-0.5Fe/TiO2 composites have a 10-fold enhancement in photocatalytic activity compared to pure TiO2, surpassing GR-TiO2 (six times) and Fe-TiO2 (two times). | Fast electron transfer | Photocatalysis | Khalid et al., 2012 [92] |

| N-doped reduced graphene oxide (NRG) | SnS2/polyaniline | Degradation of Cr (VI) | The reaction rate constant (k) for photocatalytic reduction in Cr (VI) using polyaniline/SnS2/NRG2% is 3.8, which is higher than that of SnS2 (0.8), SnS2/NGR (1.9), and SnS2/polyaniline (2). | Cumulative effect | Photocatalysis | Zhang et al., 2018 [107] |

| Graphene | Co-Fe2O4 | Degradation of methylene blue (MB) | CoFe2O4-G degrades most of MB under visible-light irradiation at 25 °C, while pure CoFe2O4 hardly degrades MB. | Cumulative effect | Photocatalysis | Fu et al., 2012 [100] |

| Graphene | TiO2 | Degradation of MB | G-TiCl3 led to an 89.13% and 78.15% decrease in MB concentration when irradiated with UV and sunlight, respectively. In comparison, G reduced MB by 6.7% and 6.5%, while TiCl3 reduced MB by 34.5% and 14.2%. | Cumulative effect | Photocatalysis | Karimi et al., 2015 [101] |

| NG | Fe oxide/Fe hydroxide | Degradation of antibiotics (Chloramphenicol sodium succinate, CAP) | The Fe oxide/Fe hydroxide/N-rGO hybrid nanocomposites degraded around 62.5% of CAP under visible light irradiation during 150 min, in contrast to pure Fe oxide/Fe hydroxide (around 5%) or N-rGO layers (under 15%). | Fast electron transfer | Photocatalysis | Ivan et al., 2023 [108] |

| GO | Copper-centered metal (MOF) | Hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) Oxygen evolution reaction (OER) Oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) | The electroactive surface area of GO/Cu-MOF is 20 times higher than that of the bare electrode, while that of Cu-MOF is 4 times higher, with almost no increase in GO. | Cumulative effect | Electrocatalysis | Jahan et al., 2013 [96] |

| rGO | Iron–porphyrin metal–organic framework ((Fe-P) nMOF) | ORR | The redox current of G-(Fe-P)nMOF increased nearly 10-fold compared to bare GC, while (Fe-P)nMOF increased 2-fold. | Cumulative effect | Electrocatalysis | Jahan et al., 2012 [90] |

| rGO | CoFe2O4 | ORR OER | The current density for the OER of CoFe2O4/rGO is significantly higher at 29.5 mA·cm2 compared to CoFe2O4 (below 7.5 mA·cm−2) and rGO (below 15 mA·cm−2). | Fast electron transfer | Electrocatalysis | Bian et al., 2014 [103] |

| rGO | Boron nitride nanosheets (BNNSs) | Li2S conversion | BNNSs/rGO exhibits the lowest onset potential (−0.41 V) compared with BNNSs + rGO (−0.32 V), rGO (−0.28 V) and BNNSs (−0.26 V) electrodes. | Cumulative effect | Electrocatalysis | Yang et al., 2023 [109] |

| GO | Co3O4 | Degradation of Orange II | GO-Co3O4 degraded Orange II in water (100% degradation) in a very short time of 4 min, while bare Co3O4 (approximately 10% degradation) and GO (nearly 5% degradation) did not. | Cumulative effect | Chemical catalysis | Shi et al., 2014 [105] |

| rGO | Au-Cu | Degradation of 4-nitrophenol (4-NP) | The Au3-Cu1/rGO nanocatalyst showed the highest kapp value of 96 × 10−3·s−1, which is nearly 9 times higher than that of Au/rGO (kapp = 11 × 10−3·s−1) and approximately 14 times higher than that of Cu/rGO (kapp = 7 × 10−3·s−1). | Cumulative effect | Chemical catalysis | Rout et al., 2017 [23] |

| Graphene | C3N4 | Production of cyclohexanone | G-C3N4 (with ~1.2 wt% graphene) provides the highest yield (5.4%) for cyclohexanone, while graphene or C3N4 alone cannot produce any cyclohexanone. | Fast electron transfer | Chemical catalysis | Chen et al., 2016 [110] |

2.4. Graphene-Based Composites with Improved Mechanic Properties

2.5. Graphene-Based Conductive Composites

2.6. Graphene-Based Sensors

2.7. Graphene-Based Electromagnetic Interference (EMI) Shielding

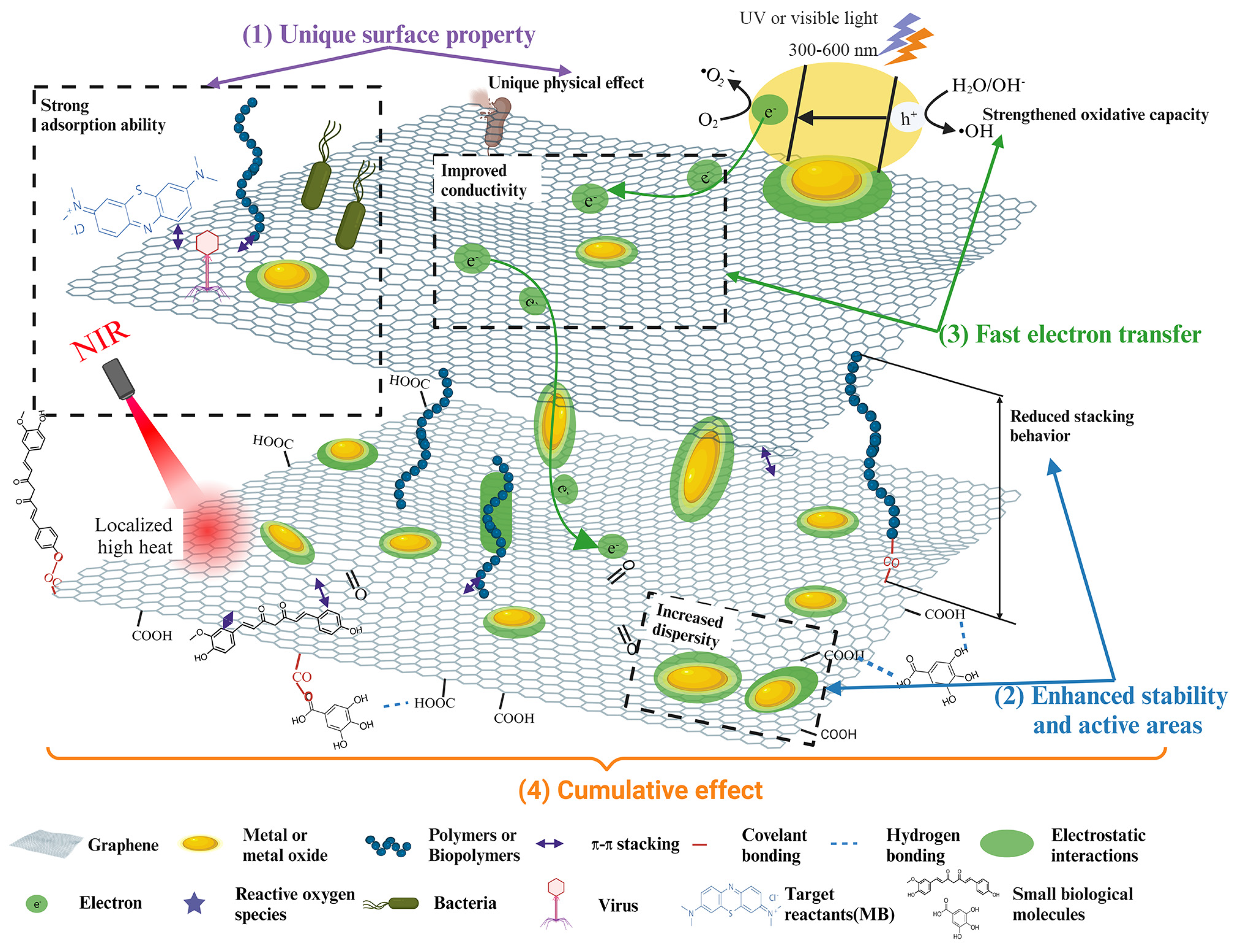

3. Synergistic Mechanisms in Graphene-Based Composites

3.1. Unique Surface Property

3.2. Enhanced Stability and Active Areas

3.3. Fast Electron Transfer

3.4. Cumulative Effects

4. Conclusions, Challenges and Future Perspectives

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ji, H.; Sun, H.; Qu, X. Antibacterial Applications of Graphene-Based Nanomaterials: Recent Achievements and Challenges. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 105, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukowiak, A.; Kedziora, A.; Strek, W. Antimicrobial Graphene Family Materials: Progress, Advances, Hopes and Fears. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2016, 236, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawal, A.T. Graphene-Based Nano Composites and Their Applications: A Review. Biosens. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 141, 111384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaleel, J.A.; Sruthi, S.; Pramod, K. Reinforcing Nanomedicine Using Graphene Family Nanomaterials. J. Control. Release 2017, 255, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamang, S.; Rai, S.; Bhujel, R.; Bhattacharyya, N.K.; Swain, B.P.; Biswas, J. A concise review on GO, rGO and metal oxide/rGO composites: Fabrication and their supercapacitor and catalytic applications. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 947, 169588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Wu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y. Graphene Family Nanomaterials (GFNs)—Promising Materials for Antimicrobial Coating and Film: A Review. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 358, 1022–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Ye, X.; Han, J.; Chen, Q.; Fan, P.; Zhang, H.; Xie, D.; Zhu, H.; Zhong, M. Precise Control of the Number of Layers of Graphene by Picosecond Laser Thinning. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Kong, W. Recent Progress in Graphene-Based and Ion-Intercalation Electrode Materials for Capacitive Deionization. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2020, 878, 114703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Zheng, Y.B.; Zhao, F.; Li, S.; Gao, X.; Xu, B.; Weiss, P.S.; Zhao, Y. Chemistry and Physics of a Single Atomic Layer: Strategies and Challenges for Functionalization of Graphene and Graphene-Based Materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Wang, G.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X. Graphene-Based Antimicrobial Nanomaterials: Rational Design and Applications for Water Disinfection and Microbial Control. Environ. Sci. Nano 2017, 4, 2248–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- One-Step Synthesis of Pt-Decorated Graphene–Carbon Nanotubes for the Electrochemical Sensing of Dopamine, Uric Acid and Ascorbic Acid. Available online: https://ouci.dntb.gov.ua/en/works/4O8j8AOl/ (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Li, X.; Zhi, L. Graphene hybridization for energy storage applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 3189–3216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Cheng, Q. Synergistic Reinforcing Effect from Graphene and Carbon Nanotubes. Compos. Commun. 2018, 10, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Xu, Q.; Jiang, H.L. Metal-Organic Frameworks Meet Metal Nanoparticles: Synergistic Effect for Enhanced Catalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 4774–4808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, Y.; Luo, X.; Qiao, J.; Huang, H. “More Is Different:” Synergistic Effect and Structural Engineering in Double-Atom Catalysts. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2007423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Uliana, A.; Zhu, J.; Liu, J.; Bruggen, B. Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework/Graphene Oxide Hybrid Nanosheets Functionalized Thin Film Nanocomposite Membrane for Enhanced Antimicrobial Performance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 25508–25519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Zheng, S.; Xue, H.; Pang, H. Metal-Organic Frameworks/Graphene-Based Materials: Preparations and Applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1804950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Murali, S.; Cai, W.; Li, X.; Suk, J.W.; Potts, J.R.; Ruoff, R.S. Graphene and Graphene Oxide: Synthesis, Properties, and Applications. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 3906–3924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Loh, K.P. Carbocatalysts: Graphene Oxide and Its Derivatives. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 2275–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabath, L.D.; Abraham, E.P. Synergistic Action of Penicillins and Cephalosporins against Pseudomonas Pyocyanea. Nature 1964, 204, 1066–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegab, H.M.; Elmekawy, A.; Zou, L.; Mulcahy, D.; Saint, C.P.; Ginic-Markovic, M. The Controversial Antibacterial Activity of Graphene-Based Materials. Carbon 2016, 105, 362–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Z.; Luo, Y. Mechanisms of the Antimicrobial Activities of Graphene Materials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 2064–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rout, L.; Kumar, A.; Dhaka, R.S.; Reddy, G.N.; Giri, S.; Dash, P. Bimetallic Au-Cu Alloy Nanoparticles on Reduced Graphene Oxide Support: Synthesis, Catalytic Activity and Investigation of Synergistic Effect by DFT Analysis. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2017, 538, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreyer, D.R.; Park, S.; Bielawski, C.W.; Ruoff, R.S. The chemistry of graphene oxide. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, S.; Siddiqui, R.; Sharma, P.; Kumar, R.; Verma, G.; Saini, A. Green Synthesis of Peptide Functionalized Reduced Graphene Oxide (rGO) Nano Bioconjugate with Enhanced Antibacterial Activity. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 9441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnamoorthy, K.; Umasuthan, N.; Mohan, R.; Lee, J.; Kim, S.J. Antibacterial activity of graphene oxide nanosheets. Sci. Adv. Mater. 2012, 4, 1111–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zeng, T.H.; Hofmann, M.; Burcombe, E.; Wei, J.; Jiang, R.; Kong, J.; Chen, Y. Antibacterial Activity of Graphite, Graphite Oxide, Graphene Oxide, and Reduced Graphene Oxide: Membrane and Oxidative Stress. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 6971–6980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, M.; Zhou, B.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, D.; Luo, H. Graphene Oxide/Gallium Nanoderivative as a Multifunctional Modulator of Osteoblastogenesis and Osteoclastogenesis for the Synergistic Therapy of Implant-Related Bone Infection. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 25, 594–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Tikekar, R.V.; Ding, Q.; Gilbert, A.R.; Wimsatt, S.T. Inactivation of Foodborne Pathogens by the Synergistic Combinations of Food Processing Technologies and Food-Grade Compounds. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 2110–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaisare, M.L.; Wu, B.S.; Wu, M.C.; Khan, M.S.; Tseng, M.H.; Wu, H.F. MALDI MS Analysis, Disk Diffusion and Optical Density Measurements for the Antimicrobial Effect of Zinc Oxide Nanorods Integrated in Graphene Oxide Nanostructures. Biomater. Sci. 2016, 4, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, X.; Du, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, H.; Pu, F.; Ren, J.; Qu, X. Hyaluronic Acid-Templated Ag Nanoparticles/Graphene Oxide Composites for Synergistic Therapy of Bacteria Infection. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 19717–19724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.H.; Gong, J.L.; Zeng, G.M.; Niu, C.G.; Niu, Q.Y.; Zhang, W.; Liu, H.Y. Inactivation Performance and Mechanism of Escherichia Coli in Aqueous System Exposed to Iron Oxide Loaded Graphene Nanocomposites. J. Hazard. Mater. 2014, 276, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, K.; Lekshmi, G.S.; Ostrikov, K.; Lussini, V.; Blinco, J.; Mohandas, M.; Vasilev, K.; Bottle, S.; Bazaka, K.; Ostrikov, K. Synergic Bactericidal Effects of Reduced Graphene Oxide and Silver Nanoparticles against Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacteria. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurapati, R.; Vaidyanathan, M.; Raichur, A.M. Synergistic Photothermal Antimicrobial Therapy Using Graphene Oxide/Polymer Composite Layer-by-Layer Thin Films. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 39852–39860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Sun, S.; Dong, A.; Hao, Y.; Shi, S.; Sun, Z.; Gao, G.; Chen, Y. Developing of a Novel Antibacterial Agent by Functionalization of Graphene Oxide with Guanidine Polymer with Enhanced Antibacterial Activity. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 355, 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Liu, H.; Samal, M.; Yun, K. Synthesis of ZnO Nanoparticles-Decorated Spindle-Shaped Graphene Oxide for Application in Synergistic Antibacterial Activity. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2018, 183, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghanem, A.F.; Badawy, A.A.; Mohram, M.E.; Rehim, M.H.A. Synergistic Effect of Zinc Oxide Nanorods on the Photocatalytic Performance and the Biological Activity of Graphene Nano Sheets. Heliyon 2020, 6, 03283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassen, A.; Moawed, E.A.; Bahy, R.; El Basaty, A.B.; El-Sayed, S.; Ali, A.I.; Tayel, A. Synergistic effects of Thermally Reduced Graphene Oxide/Zinc Oxide Composite Material on Microbial Infection for Wound Healing Applications. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 22942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jian, Z.; Wang, H.; Liu, M.; Chen, S.; Wang, Z.; Qian, W.; Luo, G.; Xia, H. Polyurethane-Modified Graphene Oxide Composite Bilayer Wound Dressing with Long-Lasting Antibacterial Effect. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 111, 110833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jana, I.D.; Kumbhakar, P.; Banerjee, S.; Gowda, C.C.; Kedia, N.; Kuila, S.K.; Banerjee, S.; Das, N.C.; Das, A.K.; Manna, I.; et al. Copper Nanoparticle-Graphene Composite-Based Transparent Surface Coating with Antiviral Activity against Influenza Virus. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021, 4, 352–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vi, T.T.T.; Kumar, S.R.; Pang, J.H.S.; Liu, Y.K.; Chen, D.W.; Lue, S.J. Synergistic Antibacterial Activity of Silver-Loaded Graphene Oxide towards Staphylococcus Aureus and Escherichia coli. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chautrand, T.; Souak, D.; Chevalier, S.; Duclairoir-Poc, C. Gram-Negative Bacterial Envelope Homeostasis under Oxidative and Nitrosative Stress. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, S.; Gao, Y.; Fang, L.; Jiang, Z.; Xie, Q.; Meng, Q.; Fei, G.; Ding, S. Graphene Oxide with Acid-Activated Bacterial Membrane Anchoring for Improving Synergistic Antibacterial Performances. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 551, 149444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Liu, Y.; Liu, M.; Wang, Y.; He, W.; Shi, G.; Hu, X.; Zhan, R.; Luo, G.; Xing, M.; et al. Synthesis of Graphene Oxide-Quaternary Ammonium Nanocomposite with Synergistic Antibacterial Activity to Promote Infected Wound Healing. Burn. Trauma 2018, 6, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Shi, J.; Zhang, H.; Yao, X.; Chen, W.; Zhang, X. A Rose Bengal/Graphene Oxide/PVA Hybrid Hydrogel with Enhanced Mechanical Properties and Light-Triggered Antibacterial Activity for Wound Treatment. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 118, 111447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F.; Ye, A.; Jiang, L.; Lu, Y.; Feng, Y.; Huang, R.; Du, S.; Dong, X.; Huang, T.; Li, P.; et al. Photothermal-Enhanced Silver Nanocluster Bioactive Glass Hydrogels for Synergistic Antimicrobial and Promote Wound Healing. Mater. Today Bio 2024, 30, 101439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, X.; Mao, C.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, Z.; Yang, X.; Yeung, K.W.K.; Pan, H.; Chu, P.K.; Wu, S. Synergistic Bacteria Killing through Photodynamic and Physical Actions of Graphene Oxide/Ag/Collagen Coating. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 26417–26428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugli, F.; Cacaci, M.; Palmieri, V.; Santo, R.; Torelli, R.; Ciasca, G.; Vito, M.; Vitali, A.; Conti, C.; Sanguinetti, M.; et al. Curcumin-Loaded Graphene Oxide Flakes as an Effective Antibacterial System against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus. Interface Focus 2018, 8, 20170059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsi, S.; Elias, N.; Sarchio, S.N.E.; Yasin, F.M. Gallic Acid Loaded Graphene Oxide Based Nanoformulation (GAGO) as Potential Anti-Bacterial Agent against Staphylococcus Aureus. Mater. Today Proc. 2018, 5, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Feng, Y.; Fan, X.; Zhang, M.; Wang, C.; Zhao, W.; Zhao, C. Biocompatible Graphene-Based Nanoagent with NIR and Magnetism Dual-Responses for Effective Bacterial Killing and Removal. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2019, 173, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, W.Y.; Huang, C.C.; Lin, T.T.; Hu, H.Y.; Lin, W.C.; Li, M.J.; Sung, H.W. Synergistic Antibacterial Effects of Localized Heat and Oxidative Stress Caused by Hydroxyl Radicals Mediated by Graphene/Iron Oxide-Based Nanocomposites. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2016, 12, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radhi, A.; Mohamad, D.; Rahman, F.S.A.; Abdullah, A.M.; Hasan, H. Mechanism and Factors Influence of Graphene-Based Nanomaterials Antimicrobial Activities and Application in Dentistry. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 11, 1290–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Tao, B.; He, Y.; Liu, J.; Lin, C.; Shen, X.; Ding, Y.; Yu, Y.; Mu, C.; Liu, P.; et al. Biocompatible MoS2/PDA-RGD Coating on Titanium Implant with Antibacterial Property via Intrinsic ROS-Independent Oxidative Stress and NIR Irradiation. Biomaterials 2019, 217, 119290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.; Liu, X.; Min, H.; Dong, G.; Feng, Q.; Zuo, S. Preparation, Characterization, and Antibacterial Activity of Silver Nanoparticle-Decorated Graphene Oxide Nanocomposite. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 6966–6973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seabra, A.B.; Paula, A.J.; Lima, R.; Alves, O.L.; Durán, N. Nanotoxicity of Graphene and Graphene Oxide. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2014, 27, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; He, J.; Zhu, L.; Wang, Y.; Feng, X.; Chang, B.; Karahan, H.E.; Chen, Y. Assembly of Pi-Functionalized Quaternary Ammonium Compounds with Graphene Hydrogel for Efficient Water Disinfection. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 535, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filina, A.; Yousefi, N.; Okshevsky, M.; Tufenkji, N. Antimicrobial Hierarchically Porous Graphene Oxide Sponges for Water Treatment. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2019, 2, 1578–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Sun, J.; Chen, X.; Wu, G.; Jin, Z.; Guo, D.; Liu, L. The Synergistic Effect of Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity and Photothermal Effect of Oxygen-Deficient Ni/Reduced Graphene Oxide Nanocomposite for Rapid Disinfection under near-Infrared Irradiation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 419, 126462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, A.; Hussain, Z.; Riaz, A.; Khan, A.N. Enhanced Mechanical, Thermal and Antimicrobial Properties of Poly(Vinyl Alcohol)/Graphene Oxide/Starch/Silver Nanocomposites Films. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 153, 592–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, K.B.; Park, G.T.; Han, S.S. Antibacterial Properties of Starch-Reduced Graphene Oxide—Polyiodide Nanocomposite. Food Chem. 2021, 342, 128385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeswari, R.; Prabu, H.G. Palladium Decorated Reduced Graphene Oxide/Zinc Oxide Nanocomposite for Enhanced Antimicrobial, Antioxidant and Cytotoxicity Activities. Process Biochem. 2020, 93, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Chen, J.; Li, H.; Chen, Y.; Lian, R.; Wang, Y. Innovative packaging materials and methods for flavor regulation of prepared aquatic products: Mechanism, classification and future prospective. Food Innov. Adv. 2023, 2, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Peng, F.; Cheng, C.; Chen, L.; Shi, X.; Gao, X.; Li, J. Synergistic antifungal activity of graphene oxide and fungicides against fusarium head blight in vitro and in vivo. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, F.; Wang, X.; Zhang, W.; Shi, X.; Cheng, C.; Hou, W.; Lin, X.; Xiao, X.; Li, J. Nanopesticide Formulation from Pyraclostrobin and Graphene Oxide as a Nanocarrier and Application in Controlling Plant Fungal Pathogens. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, K.; Li, K.; Chang, T.H.; Xie, J.; Chen, P.Y. Synergistic Antimicrobial Capability of Magnetically Oriented Graphene Oxide Conjugated with Gold Nanoclusters. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1904603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Li, C.; Wu, H.; Du, J.; Feng, J.; Zhang, J.; Huang, L.; Tan, S.; Shi, Q. Montmorillonite-Modified Reduced Graphene Oxide Stabilizes Copper Nanoparticles and Enhances Bacterial Adsorption and Antibacterial Activity. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2019, 2, 1842–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, X.; Tan, L.; Cui, Z.; Li, Z.; Liang, Y.; Zhu, S.; Yeung, K.W.K.; Zheng, Y.; Wu, S. An UV to NIR-Driven Platform Based on Red Phosphorus/Graphene Oxide Film for Rapid Microbial Inactivation. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 383, 123088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, L.; Cao, F.; Zhang, L.; Xu, J.; Xu, Z.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Shi, Y.; Li, X.; Cheng, K.; et al. Ag-Conjugated Graphene Quantum Dots with Blue Light-Enhanced Singlet Oxygen Generation for Ternary-Mode Highly-Efficient Antimicrobial Therapy. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8, 1371–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, T.; Huang, B.; Cao, J.; Li, C.; Jiao, J.; Xiao, Z.; Wei, L.; Ma, J.; Du, X.; Wang, S. Ni Nanocrystals Supported on Graphene Oxide: Antibacterial Agents for Synergistic Treatment of Bacterial Infections. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 18339–18349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, D.; An, T.; Li, G.; Wang, W.; Zhao, H.; Wong, P.K. Synergistic Photocatalytic Inactivation Mechanisms of Bacteria by Graphene Sheets Grafted Plasmonic AgAgX (X = Cl, Br, I) Composite Photocatalyst under Visible Light Irradiation. Water Res. 2016, 99, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktay, B.; Erarslan, A.; Üstündağ, C.B.; Ahlatcıoğlu Özerol, E. Preparation and Characterization of Graphene Oxide Quantum Dots/Silver Nanoparticles and Investigation of Their Antibacterial Effects. Mater. Res. Express 2024, 11, 015603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.X.; Li, C.M.; Li, Y.F.; Wang, J.; Huang, C.Z. Synergistic Antiviral Effect of Curcumin Functionalized Graphene Oxide against Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 16086–16092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, N.; Liu, Y.; Fan, X.; Jiang, Z.; Ren, X.; Liang, J. Preparation and Characterization of Antibacterial Graphene Oxide Functionalized with Polymeric N-Halamine. J. Mater. Sci. 2017, 52, 1996–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Rao, L.; Liao, X. Extracellular pH Decline Introduced by High Pressure Carbon Dioxide Is a Main Factor Inducing Bacteria to Enter Viable but Non-Culturable State. Food Res. Int. 2022, 151, 110895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lee, J.-S.; Lee, H. Combination Treatment of Hepatitis C Virus-Associated Hepatocellular Carcinoma by Simultaneously Blocking Genes in Multiple Organelles via Functionally Engineered Graphene Oxide. Chem. Eng. J 2023, 452, 139279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.T.; Tabakman, S.M.; Liang, Y.; Wang, H.; Casalongue, H.S.; Vinh, D.; Dai, H. Ultrasmall Reduced Graphene Oxide with High Near-Infrared Absorbance for Photothermal Therapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 6825–6831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Guo, Z.; Huang, D.; Liu, Z.; Guo, X.; Zhong, H. Synergistic Effect of Chemo-Photothermal Therapy Using PEGylated Graphene Oxide. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 8555–8561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, G.; Yan, M.; Dong, R.; Wang, D.; Zhou, X.; Chen, J.; Hao, J. Covalent Modification of Reduced Graphene Oxide by Means of Diazonium Chemistry and Use as a Drug-Delivery System. Chem. A Eur. J. 2012, 18, 14708–14716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, D.; Zhang, J.; Gao, G.; Sheng, Z.; Cui, H.; Cai, L. Indocyanine Green-Loaded Polydopamine-Reduced Graphene Oxide Nanocomposites with Amplifying Photoacoustic and Photothermal Effects for Cancer Theranostics. Theranostics 2016, 6, 1043–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Jang, J.; Nagase, S. Hydrazine and Thermal Reduction of Graphene Oxide: Reaction Mechanisms, Product Structures, and Reaction Design. J. Phys. Chem. 2010, 114, 832–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Bao, Q.; Tang, L.A.L.; Zhong, Y.; Loh, K.P. Hydrothermal Dehydration for the “Green” Reduction of Exfoliated Graphene Oxide to Graphene and Demonstration of Tunable Optical Limiting Properties. Chem. Mater. 2009, 21, 2950–2956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.T.; Li, C.M. Restoring Basal Planes of Graphene Oxides for Highly Efficient Loading and Delivery of β-Lapachone. Mol. Pharm. 2012, 9, 615–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Zhang, G.; Gauquelin, N.; Chen, N.; Zhou, J.; Yang, S.; Chen, W.; Meng, X.; Geng, D.; Banis, M.N.; et al. Single-atom catalysis using Pt/graphene achieved through atomic layer deposition. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Gu, T.H.; Kwon, N.H.; Hwang, S.J. Synergetic Advantages of Atomically Coupled 2D Inorganic and Graphene Nanosheets as Versatile Building Blocks for Diverse Functional Nanohybrids. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2005922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgakilas, V.; Tiwari, J.N.; Kemp, K.C.; Perman, J.A.; Bourlinos, A.B.; Kim, K.S.; Zboril, R. Noncovalent Functionalization of Graphene and Graphene Oxide for Energy Materials, Biosensing, Catalytic, and Biomedical Applications. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 5464–5519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niyogi, S.; Bekyarova, E.; Itkis, M.E.; Zhang, H.; Shepperd, K.; Hicks, J.; Sprinkle, M.; Berger, C.; Lau, C.N.; Deheer, W.A.; et al. Spectroscopy of covalently functionalized graphene. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 4061–4066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacHado, B.F.; Serp, P. Graphene-Based Materials for Catalysis. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2012, 2, 54–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Guo, Y.; Zhou, Z. Three-Dimensional Graphene-Based Macrostructures for Electrocatalysis. Small 2021, 17, 2005255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Liang, B.; Cao, Q.; Mo, C.; Zheng, Y.; Ye, X. Vertically aligned PANI nanorod arrays grown on graphene oxide nanosheets for a high-performance NH3 gas sensor. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 33510–33520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, M.; Bao, Q.; Loh, K.P. Electrocatalytically Active Graphene-Porphyrin MOF Composite for Oxygen Reduction Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 6707–6713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Peng, Q.; Yang, R.; Wang, B.; Zhang, X.; Wang, R.; Zhu, X.; Cheng, M.; Xu, H.; Li, H. Incorporating Fe, Co Co-Doped Graphene with PDI Supermolecular for Promoted Photocatalytic Activity: A Story of Electron Transfer. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 637, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, N.R.; Hong, Z.; Ahmed, E.; Zhang, Y.; Chan, H.; Ahmad, M. Synergistic effects of Fe and Graphene on Photocatalytic Activity Enhancement of TiO2 under Visible Light. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2012, 258, 5827–5834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Xiao, S.; Zheng, Y.; Rong, X.; Bai, M.; Tang, Y.; Ma, T.; Cheng, C.; Zhao, C. Emerging Electrocatalytic Activities in Transition Metal Selenides: Synthesis, Electronic Modulation, and Structure-Performance Correlations. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 451, 138514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namsheer, K.; Rout, C.S. Conducting Polymers: A Comprehensive Review on Recent Advances in Synthesis, Properties and Applications. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 5659–5697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramanik, A.; Dhar, J.A.; Banerjee, R.; Davis, M.; Gates, K.; Nie, J.; Davis, D.; Han, F.X.; Ray, P.C. WO 3 Nanowire-Attached Reduced Graphene Oxide-Based 1D–2D Heterostructures for near-Infrared Light-Driven Synergistic Photocatalytic and Photothermal Inactivation of Multidrug-Resistant Superbugs. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2023, 6, 919–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, M.; Liu, Z.; Loh, K.P. A Graphene Oxide and Copper-Centered Metal Organic Framework Composite as a Tri-Functional Catalyst for HER, OER, and ORR. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2013, 23, 5363–5372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; He, D.; Duan, J.; Wang, S.; Peng, H.; Wu, H.; Fu, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X. Simple Synthesis Method of Reduced Graphene Oxide/Gold Nanoparticle and Its Application in Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2013, 582, 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, S.; Lee, J.M.; Kim, S.J.; Kim, H.; Jin, X.; Wang, K.K.; Kim, M.; Hwang, J.W.; Choi, W.; Kim, Y.R.; et al. Understanding the Relative Efficacies and Versatile Roles of 2D Conductive Nanosheets in Hybrid-Type Photocatalyst. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2019, 257, 117875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Fu, X.; Zhang, Y. 3D-2D-3D BiOI/Porous g-C3N4/Graphene Hydrogel Composite Photocatalyst with Synergy of Adsorption-Photocatalysis in Static and Flow Systems. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 850, 156778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Chen, H.; Sun, X.; Wang, X. Combination of Cobalt Ferrite and Graphene: High-Performance and Recyclable Visible-Light Photocatalysis. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2012, 111–112, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, L.; Yazdanshenas, M.E.; Khajavi, R.; Rashidi, A.; Mirjalili, M. Optimizing the Photocatalytic Properties and the Synergistic effects of Graphene and Nano Titanium Dioxide Immobilized on Cotton Fabric. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 332, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Tan, H.; Zhang, L.; Cheng, B.; Yu, J. In-Situ Growth of Few-Layer Graphene on ZnO with Intimate Interfacial Contact for Enhanced Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction Activity. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 411, 128501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, W.; Yang, Z.; Strasser, P.; Yang, R. A CoFe2O4/Graphene Nanohybrid as an Efficient Bi-Functional Electrocatalyst for Oxygen Reduction and Oxygen Evolution. J. Power Sources 2014, 250, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xu, X.; Lu, X.; He, C.; Huang, J.; Sun, W.; Tian, L. Synergistic Coupling of FeNi3 Alloy with Graphene Carbon Dots for Advanced Oxygen Evolution Reaction Electrocatalysis. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 615, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, P.; Dai, X.; Zheng, H.; Li, D.; Yao, W.; Hu, C. Synergistic Catalysis of Co3O4 and Graphene Oxide on Co3O4/GO Catalysts for Degradation of Orange II in Water by Advanced Oxidation Technology Based on Sulfate Radicals. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 240, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Liu, G.; Dong, B.; Jin, R.; Zhou, J. Synergistic catalytic Fenton-like degradation of sulfanilamide by biosynthesized goethite-reduced graphene oxide composite. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 415, 125704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Yang, Z.; Dionysiou, D.D.; Zhu, A. Exceptional Synergistic Enhancement of the Photocatalytic Activity of SnS2 by Coupling with Polyaniline and N-Doped Reduced Graphene Oxide. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2018, 236, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivan, R.; Popescu, C.; Antohe, V.A.; Antohe, S.; Negrila, C.; Logofatu, C.; Pino, A.P.; György, E. Iron Oxide/Hydroxide–Nitrogen Doped Graphene-like Visible-Light Active Photocatalytic Layers for Antibiotics Removal from Wastewater. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Cao, C.; Qiao, J.; Qiao, W.; Jiang, B.; Tang, C.; Xue, Y. Self-Assembled BNNSs/rGO Heterostructure as a Synergistic Adsorption and Catalysis Mediator Boosts the Electrochemical Kinetics of Lithium-Sulfur Batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 471, 144737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Chai, Z.; Li, C.; Shi, L.; Liu, M.; Xie, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, D.; Manivannan, A.; Liu, Z. Catalyst-Free Growth of Three-Dimensional Graphene Flakes and Graphene/g-C3N4 Composite for Hydrocarbon Oxidation. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 3665–3673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Nafezarefi, F.; Tai, N.H.; Schlagenhauf, L.; Nüesch, F.A.; Chu, B.T.T. Size and Synergy Effects of Nanofiller Hybrids Including Graphene Nanoplatelets and Carbon Nanotubes in Mechanical Properties of Epoxy Composites. Carbon 2012, 50, 5380–5386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, K.; Feng, S.; Han, Y.; Gao, L.; Ly, T.H.; Xu, Z.; Lu, Y. Elastic straining of free-standing monolayer graphene. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, D.G.; Kinloch, I.A.; Young, R.J. Mechanical properties of graphene and graphene-based nanocomposites. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2017, 90, 75–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, T.; Yu, T.; Zheng, L.; Liao, K. Synergistic Effect of Hybrid Carbon Nantube-Graphene Oxide as a Nanofiller in Enhancing the Mechanical Properties of PVA Composites. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21, 10844–10851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagotia, N.; Choudhary, V.; Sharma, D.K. Synergistic Effect of Graphene/Multiwalled Carbon Nanotube Hybrid Fillers on Mechanical, Electrical and EMI Shielding Properties of Polycarbonate/Ethylene Methyl Acrylate Nanocomposites. Compos. Part B Eng. 2019, 159, 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, C.; Guo, W.; Wu, P.; Yang, W.; Hu, S.; Xia, Y.; Feng, P. A Graphene Oxide-Ag Co-Dispersing Nanosystem: Dual Synergistic effects on Antibacterial Activities and Mechanical Properties of Polymer Scaffolds. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 347, 322–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, K.H.; Yu, J.; You, N.H.; Han, H.; Ku, B.C. Synergistic Toughening of Polymer Nanocomposites by Hydrogen-Bond Assisted Three-Dimensional Network of Functionalized Graphene Oxide and Carbon Nanotubes. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2017, 149, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Dichiara, A.; Bai, J. Carbon Nanotube-Graphene Nanoplatelet Hybrids as High-Performance Multifunctional Reinforcements in Epoxy Composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2013, 74, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, G.; Tang, M.; Zhou, L.; Li, J.; Fan, X.; Shi, X.; Qin, J. Synergistic Effect of Carbon Nanotube and Graphene Nanoplates on the Mechanical, Electrical and Electromagnetic Interference Shielding Properties of Polymer Composites and Polymer Composite Foams. Chem. Eng. J 2018, 353, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Wang, S.; Song, P.; Wu, C.; Chen, S.; Wang, X. Combination Effect of Carbon Nanotubes with Graphene on Intumescent Flame-Retardant Polypropylene Nanocomposites. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2014, 59, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Han, S.; Xin, G.; Lin, J.; Wei, R.; Lian, J.; Sun, K.; Zu, X.; Yu, Q. High-Quality Graphene Directly Grown on Cu Nanoparticles for Cu-Graphene Nanocomposites. Mater. Des. 2018, 139, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.-Y.; Lin, W.-N.; Huang, Y.-L.; Tien, H.-W.; Wang, J.-Y.; Ma, C.-C.M.; Li, S.-M.; Wang, Y.-S. Synergetic Effects of Graphene Platelets and Carbon Nanotubes on the Mechanical and Thermal Properties of Epoxy Composites. Carbon 2011, 49, 793–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, K.E.; Das, B.; Maitra, U.; Ramamurty, U.; Rao, C.N.R. Extraordinary Synergy in the Mechanical Properties of Polymer Matrix Composites Reinforced with 2 Nanocarbons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 13186–13189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thu, T.V.; Nguyen, T.; Le, X.D.; Le, T.S.; Thuy, V.; Huy, T.Q.; Truong, Q.D. Graphene-MnFe2O4-Polypyrrole Ternary Hybrids with Synergistic Effect for Supercapacitor Electrode. Electrochim. Acta 2019, 314, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankovich, S.; Dikin, D.A.; Dommett, G.H.B.; Kohlhaas, K.M.; Zimney, E.J.; Stach, E.A.; Piner, R.D.; Nguyen, S.B.T.; Ruoff, R.S. Graphene-based composite materials. Nature 2006, 442, 282–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, V.B.; Lau, K.; Hui, D.; Bhattacharyya, D. Graphene-Based Materials and Their Composites: A Review on Production, Applications and Product Limitations. Compos. Part B Eng. 2018, 142, 200–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Yu, C.; Yang, J.; Ling, Z.; Hu, C.; Zhang, M.; Qiu, J. A Layered-Nanospace-Confinement Strategy for the Synthesis of Two-Dimensional Porous Carbon Nanosheets for High-Rate Performance Supercapacitors. Adv. Energy Mater. 2015, 5, 1401761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toupin, M.; Brousse, T.; Bélanger, D. Charge Storage Mechanism of MnO2 Electrode Used in Aqueous Electrochemical Capacitor. Chem. Mater. 2004, 16, 3184–3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratha, S.; Rout, C.S. Supercapacitor Electrodes Based on Layered Tungsten Disulfide-Reduced Graphene Oxide Hybrids Synthesized by a Facile Hydrothermal Method. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 11427–11433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snook, G.A.; Kao, P.; Best, A.S. Conducting-Polymer-Based Supercapacitor Devices and Electrodes. J. Power Sources 2011, 196, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Liu, H.Y.; Kang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Jiang, S.; Li, B.; Yin, J.; Zhu, J. Synergistic Combination of Carbon-Black and Graphene for 3D Printable Stretchable Conductors. Mater. Technol. 2022, 37, 1971–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar, S.; Ramamurthy, S.S. Synergistic Coupling of Titanium Carbonitride Nanocubes and Graphene Oxide for 800-Fold Fluorescence Enhancements on Smartphone Based Surface Plasmon-Coupled Emission Platform. Mater. Lett. 2021, 298, 130008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Xie, H.; Zhou, S.; Sheng, X.; Chen, L.; Zhong, M. Construction of AuNPs/Reduced Graphene Nanoribbons Co-Modified Molecularly Imprinted Electrochemical Sensor for the Detection of Zearalenone. Food Chem. 2023, 423, 136294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velmurugan, M.; Karikalan, N.; Chen, S.M.; Dai, Z.C. Studies on the Influence of β-Cyclodextrin on Graphene Oxide and Its Synergistic Activity to the Electrochemical Detection of Nitrobenzene. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 490, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Duan, N.; Qiu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, Z. Colorimetric Aptasensor for the Detection of Salmonella Enterica Serovar Typhimurium Using ZnFe2O4-Reduced Graphene Oxide Nanostructures as an Effective Peroxidase Mimetics. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2017, 261, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Hu, W.; Xiong, Y.; Xu, Y.; Li, C.M. Multifunctionalized reduced graphene oxide-doped polypyrrole/pyrrolepropylic acid nanocomposite impedimetric immunosensor to ultra-sensitively detect small molecular aflatoxin B1. Biosens. Bioelectron 2015, 63, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, H.; Marquette, C.A.; Dutta, P.; Rajesh, G.S. Integrated Graphene Quantum Dot Decorated Functionalized Nanosheet Biosensor for Mycotoxin Detection. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2020, 412, 7029–7041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, N.; Shen, M.; Wu, S.; Zhao, C.; Ma, X.; Wang, Z. Graphene Oxide Wrapped Fe3O4@Au Nanostructures as Substrates for Aptamer-Based Detection of Vibrio Parahaemolyticus by Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy. Microchim. Acta 2017, 184, 2653–2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Guo, L.; Li, J.; Li, N.; Zhang, G.; Gao, Y.; Li, J.; Cao, D.; Wang, W.; Jin, Y.; et al. Binary Synergistic Sensitivity Strengthening of Bioinspired Hierarchical Architectures Based on Fragmentized Reduced Graphene Oxide Sponge and Silver Nanoparticles for Strain Sensors and Beyond. Small 2017, 13, 1700944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, E.; Xi, J.; Guo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Peng, L.; Gao, W.; Ying, J.; Chen, Z.; Gao, C. Synergistic Effect of Graphene and Carbon Nanotube for High-Performance Electromagnetic Interference Shielding Films. Carbon 2018, 133, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurutuza, A.; Marinelli, C. Challenges and Opportunities in Graphene Commercialization. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2014, 9, 730–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xiao, J.; Gao, X.; Xu, J.; Tan, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, H. Unveiling the Synergistic Effects in Graphene-Based Composites as a New Strategy for High Performance and Sustainable Material Development: A Critical Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10058. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210058

Xiao J, Gao X, Xu J, Tan J, Zhang X, Zhang H. Unveiling the Synergistic Effects in Graphene-Based Composites as a New Strategy for High Performance and Sustainable Material Development: A Critical Review. Sustainability. 2025; 17(22):10058. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210058

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiao, Jie, Xingxing Gao, Jie Xu, Juzhong Tan, Xuesong Zhang, and Hongchao Zhang. 2025. "Unveiling the Synergistic Effects in Graphene-Based Composites as a New Strategy for High Performance and Sustainable Material Development: A Critical Review" Sustainability 17, no. 22: 10058. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210058

APA StyleXiao, J., Gao, X., Xu, J., Tan, J., Zhang, X., & Zhang, H. (2025). Unveiling the Synergistic Effects in Graphene-Based Composites as a New Strategy for High Performance and Sustainable Material Development: A Critical Review. Sustainability, 17(22), 10058. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210058