A Proposal of an Integrated Framework for the Strategic Implementation of Product-Service Systems in Brazilian Industrial Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Barriers and Drivers Related to the Adoption of PSSs

3. PSS Implementation and Its Relationship with the Business Model and Innovation Process

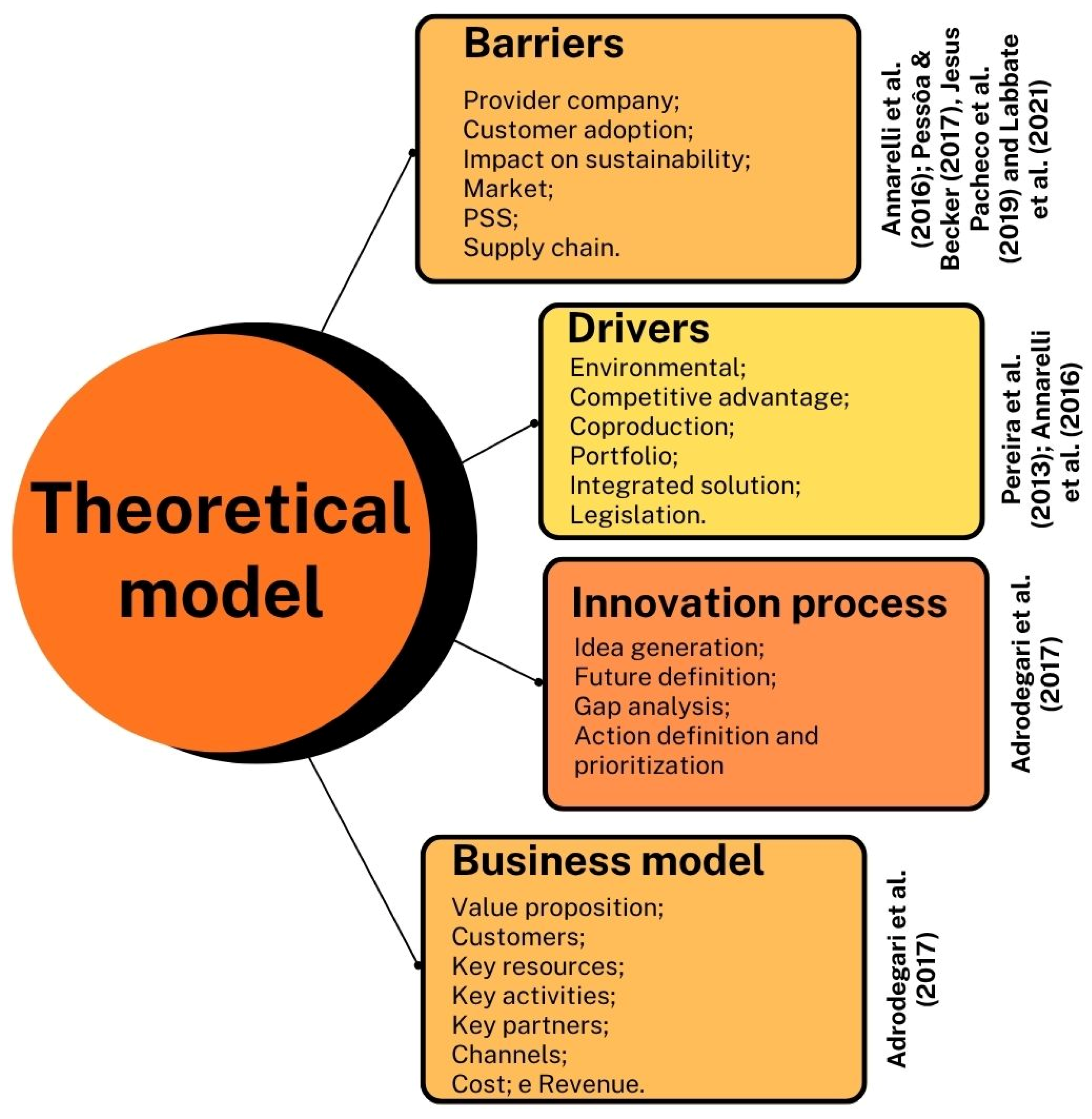

4. Summary of the Theoretical Model Developed

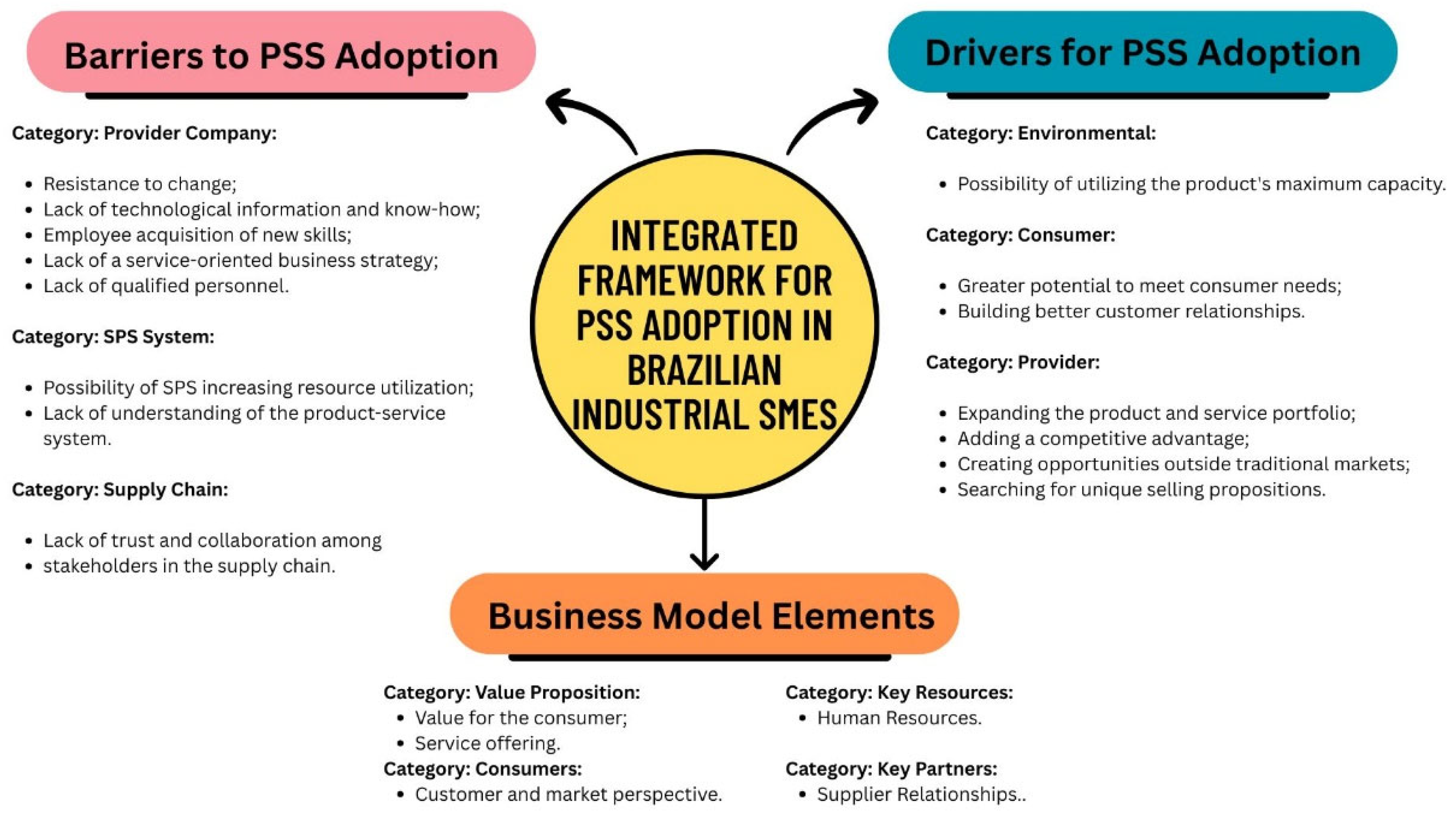

4.1. Barriers to the Adoption of PSS

4.2. Drivers for PSS Adoption

4.3. The Innovation Process and Business Model for PSS

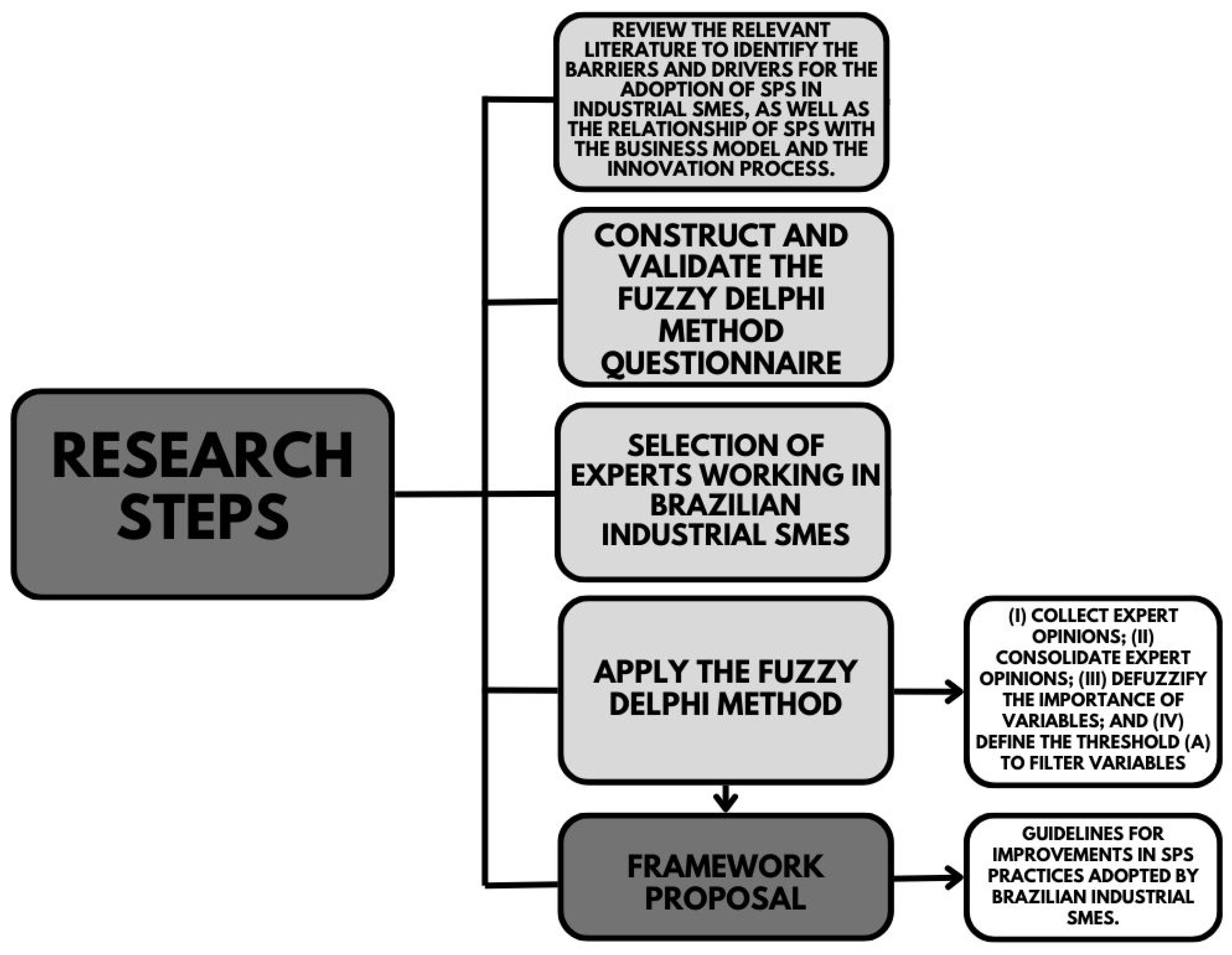

5. Methods

| Response Option According to the Likert Scale Used | Linguistic Variable | Assessment | TFN Corresponding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Totally disagree | Very low | 1 | (0.1, 0.1, 0.3) |

| Disagree | Low | 2 | (0.1, 0.3, 0.5) |

| Neutral | Average | 3 | (0.3, 0.5, 0.7) |

| I agree | High | 4 | (0.5, 0.7, 0.9) |

| I totally agree | Very High | 5 | (0.7, 0.9, 0.9) |

| Does not apply | Worthless | 0 | (Will not be used in the calculation) |

6. Results

Integrated Framework of the Context of Product-Service Systems (PSSs) Adoption by Brazilian Industrial Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises at the Time of Writing

7. Conclusions, Implications, and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Table

| Block | Analysis Categories | Variable Code | Variable Description | TFN | Defuzzification Value | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barriers to PSS adoption in industrial companies | Provider company | BPSS1 | Technological adequacy | (0.1; 0.5; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected |

| BPSS2 | Resistance to change | (0.3; 0.7; 0.9) | 0.60 | Selected | ||

| BPSS3 | Lack of technological information and know-how (knowledge) | (0.3; 0.6; 0.9) | 0.60 | Selected | ||

| BPSS4 | Lack of experience with services | (0.1; 0.4; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| BPSS5 | High financial risk | (0.1; 0.5; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| BPSS6 | Need for company adjustments | (0.1; 0.6; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| BPSS7 | Acquisition of new skills by employees | (0.1; 0.7; 0.9) | 0.60 | Selected | ||

| BPSS8 | Lack of infrastructure | (0.1; 0.5; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| BPSS9 | Changes in source of income | (0.1; 0.6; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| BPSS10 | Super diversification of product/service offerings | (0.1; 0.6; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| BPSS11 | Internal competition (between products and services) | (0.1; 0.5; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| BPSS12 | Difficulty recognizing the changes needed in the company | (0.1; 0.6; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| BPSS13 | Low engagement in innovation activities | (0.1; 0.6; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| BPSS14 | Lack of a service-oriented business strategy | (0.3; 0.7; 0.9) | 0.60 | Selected | ||

| BPSS15 | Short-term management practices | (0.1; 0.5; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| BPSS16 | Need for high investments | (0.1; 0.6; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| BPSS17 | Low commitment from company management | (0.1; 0.5; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| BPSS18 | Shortage of qualified personnel | (0.1; 0.7; 0.9) | 0.60 | Selected | ||

| BPSS19 | Complex transition | (0.1; 0.6; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| Consumer | BPSS20 | Lack of customer acceptance | (0.1; 0.4; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | |

| BPSS21 | Lack of customer confidence | (0.1; 0.3; 0.9) | 0.40 | Rejected | ||

| BPSS22 | Access to information on service usage | (0.1; 0.5; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| BPSS23 | Complexity and cost of acquisition for the consumer | (0.1; 0.5; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| BPSS24 | Responsibility shared between provider and user | (0.1; 0.6; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| Sustainability | BPSS25 | Uncertainty that PSS will generate sustainability benefits | (0.1; 0.6; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | |

| BPSS26 | Limited knowledge regarding sustainability issues | (0.1; 0.6; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| Market | BPSS27 | Lack of consumer demand for services | (0.1; 0.4; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | |

| PSS System | BPSS28 | Possibility of PSS increasing resource use | (0.3; 0.6; 0.9) | 0.60 | Selected | |

| BPSS29 | Lack of acceptance of servitization | (0.1; 0.4; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| BPSS30 | Lack of understanding of the product-service system | (0.3; 0.6; 0.9) | 0.60 | Selected | ||

| Supply chain | BPSS31 | Lack of trust and collaboration among stakeholders in the chain | (0.3; 0.6; 0.9) | 0.60 | Selected | |

| BPSS32 | Difficult relationships between stakeholders | (0.1; 0.5; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| BPSS33 | Inappropriate mindset of stakeholders | (0.1; 0.5; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| Drivers for PSS adoption in industrial companies | Environmental | DPSS1 | Focus on environmental aspects | (0.1; 0.3; 0.9) | 0.40 | Rejected |

| DPSS2 | Possibility of product maintenance and repair | (0.1; 0.6; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| DPSS3 | Possibility of utilizing the product’s maximum capacity | (0.3; 0.7; 0.9) | 0.60 | Selected | ||

| DPSS4 | Assistance in the correct disposal of products after use | (0.1; 0.5; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| DPSS5 | Possibility of maintaining profits and reducing environmental impact | (0.1; 0.5; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| DPSS6 | Reduction in the use of materials | (0.1; 0.6; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| DPSS7 | Developing offers that benefit the environment and that customers can afford | (0.1; 0.5; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| Consumer | DPSS8 | Greater potential to meet consumer needs | (0.3; 0.7; 0.9) | 0.60 | Selected | |

| DPSS9 | Allows payment flexibility | (0.1; 0.6; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| DPSS10 | Enables the co-production process with customers | (0.1; 0.5; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| DPSS11 | Building better relationships with customers | (0.3; 0.7; 0.9) | 0.60 | Selected | ||

| PSS System | DPSS12 | Disconnecting from the idea of the value of physical material | (0.1; 0.5; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | |

| DPSS13 | Offers flexibility in use/rental | (0.1; 0.4; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| DPSS14 | Possibility of using more than one PSS model | (0.1; 0.4; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| Provider company | DPSS15 | Expansion of the product and service portfolio | (0.3; 0.7; 0.9) | 0.60 | Selected | |

| DPSS16 | Senior management commitment | (0.1; 0.5; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| DPSS17 | Adding competitive advantage | (0.1; 0.7; 0.9) | 0.60 | Selected | ||

| DPSS18 | Identifying ways to co-create value | (0.1; 0.6; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| DPSS19 | Improvement in asset utilization | (0.1; 0.6; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| DPSS20 | Market share protection | (0.1; 0.6; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| DPSS21 | Creating opportunities outside traditional markets | (0.1; 0.7; 0.9) | 0.60 | Selected | ||

| DPSS22 | Search for exclusive sales proposals | (0.3; 0.7; 0.9) | 0.60 | Selected | ||

| DPSS23 | Increased engagement with suppliers | (0.1; 0.5; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| DPSS24 | Discourage new competitors | (0.1; 0.5; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| Legislation | DPSS25 | Compliance with legislation | (0.1; 0.4; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | |

| Innovation process in industrial companies focused on offering PSS | Idea generation | IPPSS1 | Business model assessment | (0.1; 0.5; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected |

| IPPSS2 | Business model expectations | (0.1; 0.6; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| IPPSS3 | Context analysis | (0.1; 0.6; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| Definition of future state | IPPSS4 | Business model structure | (0.1; 0.6; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | |

| Gap analysis | IPPSS5 | Analysis of consumer needs | (0.1; 0.6; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | |

| IPPSS6 | Gap analysis | (0.1; 0.6; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| Definition and prioritization of actions | IPPSS7 | Importance-impact-effect matrix | (0.1; 0.6; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | |

| Elements of the business model in industrial companies focused on offering PSS | Value proposition | BMPSS1 | Value for the consumer | (0.1; 0.7; 0.9) | 0.60 | Selected |

| BMPSS2 | Value creation | (0.1; 0.6; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| BMPSS3 | Product ownership | (0.1; 0.5; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| BMPSS4 | Service offering | (0.3; 0.6; 0.9) | 0.60 | Selected | ||

| Consumers | BMPSS5 | Interactions with consumers | (0.1; 0.6; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | |

| BMPSS6 | Interactions with consumers | (0.1; 0.5; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| BMPSS7 | Customer and market insight | (0.3; 0.7; 0.9) | 0.60 | Selected | ||

| BMPSS8 | Target segments and customers | (0.1; 0.6; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| Key features | BMPSS9 | ICTs and technology monitoring | (0.1; 0.5; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | |

| BMPSS10 | Installed base of information | (0.1; 0.6; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| BMPSS11 | Human resources | (0.3; 0.7; 0.9) | 0.60 | Selected | ||

| BMPSS12 | Financial resources | (0.1; 0.6; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| Key Activities | BMPSS13 | Product design and development | (0.1; 0.5; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | |

| BMPSS14 | Service design and engineering | (0.1; 0.5; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| BMPSS15 | Support for product and service configuration | (0.1; 0.5; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| BMPSS16 | Delivery of products and services | (0.1; 0.5; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| BMPSS17 | Integration and collaboration between companies | (0.1; 0.6; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| Key partners | BMPSS18 | Network | (0.1; 0.6; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | |

| BMPSS19 | Relationship with suppliers | (0.3; 0.6; 0.9) | 0.60 | Selected | ||

| Channels | BMPSS20 | Configuration with the sales channel | (0.1; 0.5; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | |

| BMPSS21 | After-sales channel and field service network | (0.1; 0.5; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| Cost | BMPSS22 | Cost structure management and composition | (0.1; 0.5; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | |

| BMPSS23 | Risk | (0.1; 0.6; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | ||

| Revenues | BMPSS24 | Revenue stream | (0.1; 0.5; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected | |

| BMPSS25 | Contractual agreements | (0.1; 0.5; 0.9) | 0.50 | Rejected |

| Analysis Category | Area to Be Improved | Required Actions | Time Horizon (Short, Medium, and Long Term) | KPIs (Key Performance Indicator) | Authors/Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provider company | Internal training and development | Training focused on technical, technological and digital skills, knowledge management and know-how development | Short term (0–12 months) | Number of employees trained; Percentage of employees with digital/technological training; Knowledge retention rate (facilitators, repositories, recorded practices). | [10,75] |

| Business Strategy | Portfolio redesign, digitalization and innovation in business models | Medium term (1–2 years) | Percentage of portfolio adapted to PSS; Number of new services/solutions added; Revenue generated by services vs. products. | [9,74] | |

| Value Chain Integration | Partnerships and collaboration with stakeholders and governance mechanisms | Medium to long term (1–3 years) | Number of new strategic partnerships; Level of data/process integration with partners; Average collaborative response time in the chain. | [9,63,73] | |

| Consumers | Customer Relationship | Co-creation, customization of products and services, value marketing | Short to medium term (6–18 months) | Customer satisfaction index; Number of co-creation projects carried out; Percentage of customizable products/services. | [10,71] |

| PSS System | PSS Risk Reduction | Pilot projects, integrated communication and focus on the life cycle | Short term for pilots; medium term for implementation (6–24 months) | Number of pilot projects carried out and validated; Success/adoption rate of pilot projects; Costs and failures per PSS life cycle. | [72,76] |

| Environmental | Sustainability and circular economy | Environmental Impact Analysis of Services and Products, Resource Management and Planning of Solutions Based on Use, Reuse and Life Cycle Extension | Medium to long term (1–3 years) | Reduction in waste and emissions (percentage of or tons); Percentage of materials reused or remanufactured; Percentage of or tons of resource savings (energy, water, raw materials) Level of circularity of the PSS. | [58,74,76] |

Appendix B. Survey Questionnaire

| Block I–Expert Profile | ||||||||

| 1. Position: | 2. Length of service at the company (years): | 3. Years of experience in the sector: | ||||||

| 4. Education: Mark one option with an X. | ||||||||

| ( ) | Elementary school | |||||||

| ( ) | High school | |||||||

| ( ) | Higher education | |||||||

| ( ) | Postgraduate studies | |||||||

| Block II–Company Profile | ||||||||

| 5. Company name: | ||||||||

| 6. Industry sector (considering the main product or product line in terms of revenue): | ||||||||

| 7. Time since company was founded (years): | ||||||||

| 8. Company’s gross operating revenue in 2023 (in Brazilian reais). Mark one of the alternatives with an X (For Brazilian companies) | 9. Total number of employees in the company. Mark one of the alternatives with an X: | |||||||

| ( ) Up to 19 ( ) From 20 to 99 ( ) From 100 to 499 ( ) Over 499 | ||||||||

| ( ) Up to R$ 2.4 million ( ) Above R$ 2.4 million up to R$ 16 million ( ) Above R$ 16 million up to R$ 90 million ( ) Above R$ 90 million up to R$ 300 million ( ) Above R$ 300 million | ||||||||

| 10. Does the company provide services? | ||||||||

| ( ) Yes ( ) Not | ||||||||

| 11. What service(s) are offered? | ||||||||

| 12. What is the share of services in the company’s revenue? | ||||||||

| ( ) Up to 20% ( ) Between 21% and 40% ( ) Between 41% and 60% ( ) Between 61% and 80% ( ) Above 80% | ||||||||

| 13. Select the type(s) of product/service offering(s) that are similar to what the company offers. | ||||||||

| ( ) The company’s business model focuses on product sales, but we add services to the offer (e.g., maintenance, supply of inputs, advisory and consulting services, etc.). ( ) The company retains ownership of the products and sells the utility, availability, or function of the products, such as leasing, renting, and sharing (e.g., rental of items/machines, sharing of items/equipment, etc.). ( ) The company sells the results of a product. (e.g., contract for number of copies, companies that offer a “pleasant climate” in offices, rather than gas or cooling equipment). | ||||||||

| Block III–Barriers | ||||||||

| The following questions seek to measure the RELEVANCE of each aspect presented. Mark the degree (score) that best reflects its relevance to the actions taken by the company, according to the following scale, in which 1 represents the lowest degree of relevance and 5 the highest relevance. The option “not applicable” should be used when the question is not related to the company’s reality or deals with practices that are not yet developed by it: | ||||||||

| Indicate the degree of relevance of barriers to the adoption of PSS in the company: | Level of relevance | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Not applicable | |||

| 1. Technological adequacy | ||||||||

| 2. Resistance to change | ||||||||

| 3. Lack of technological information and know-how (knowledge) | ||||||||

| 4. Lack of experience with services | ||||||||

| 5. High financial risk | ||||||||

| 6. Need for company adjustments | ||||||||

| 7. Acquisition of new skills by employees | ||||||||

| 8. Lack of infrastructure | ||||||||

| 9. Changes in source of profit | ||||||||

| 10. Over-diversification of product/service offerings | ||||||||

| 11. Internal competition (between products and services) | ||||||||

| 12. Difficulty in recognizing necessary changes in the company | ||||||||

| 13. Low engagement in innovation activities | ||||||||

| 14. Lack of service-oriented business strategy | ||||||||

| 15. Short-term management practices | ||||||||

| 16. Need for high investments | ||||||||

| 17. Low commitment from company management | ||||||||

| 18. Lack of qualified personnel | ||||||||

| 19. Complex transition | ||||||||

| 20. Lack of customer acceptance | ||||||||

| 21. Lack of customer confidence | ||||||||

| 22. Access to information on service use | ||||||||

| 23. Complexity and cost of acquisition for the consumer | ||||||||

| 24. Responsibility divided between provider and user | ||||||||

| 25. Uncertainty that PSS will generate benefits for sustainability | ||||||||

| 26. Limited knowledge of sustainability issues | ||||||||

| 27. Lack of consumer demand for services | ||||||||

| 28. Possibility that PSS will increase resource use | ||||||||

| 29. Lack of acceptance of servitization | ||||||||

| 30. Lack of understanding of the product-service system | ||||||||

| 31. Lack of trust and collaboration among stakeholders in the chain | ||||||||

| 32. Difficult relationships between stakeholders | ||||||||

| 33. Inappropriate mindset among stakeholders | ||||||||

| Block III–Drivers | ||||||||

| Indicate the degree of relevance of the drivers for the adoption of PSS: | Level of relevance | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Not applicable | |||

| 1. Focus on environmental aspects | ||||||||

| 2. Possibility of product maintenance and repair | ||||||||

| 3. Possibility of using the product’s maximum capacity | ||||||||

| 4. Assistance in the correct disposal of products after use | ||||||||

| 5. Possibility of maintaining profit and reducing environmental impact | ||||||||

| 6. Reduction in the use of materials | ||||||||

| 7. Development of offers that benefit the environment and that the customer can afford | ||||||||

| 8. Greater potential to satisfy consumer needs | ||||||||

| 9. Allows for payment flexibility | ||||||||

| 10. Enables co-production with customers | ||||||||

| 11. Builds better customer relationships | ||||||||

| 12. Disconnects the idea of value from physical material | ||||||||

| 13. Offers flexibility in use/rental | ||||||||

| 14. Possibility of using more than one PSS model | ||||||||

| 15. Expansion of the product and service portfolio | ||||||||

| 16. Commitment from senior management | ||||||||

| 17. Addition of competitive advantage | ||||||||

| 18. Identification of ways to co-create value | ||||||||

| 19. Improved asset utilization | ||||||||

| 20. Protection of market share | ||||||||

| 21. Creation of opportunities outside traditional markets | ||||||||

| 22. Search for unique sales proposals | ||||||||

| 23. Increased engagement with suppliers | ||||||||

| 24. Discouraging new competitors | ||||||||

| 25. Compliance with legislation | ||||||||

| Block IV–Innovation Process | ||||||||

| With regard to the innovation process for adopting PSS service offerings, the company considers the following to be important: | Level of relevance | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Not applicable | |||

| 1. Evaluation of the business model prior to PSS adoption | ||||||||

| 2. Generation of new concepts for the business model in line with expectations regarding PSS | ||||||||

| 3. Analysis of the context prior to PSS adoption (inhibitors, obstacles, facilitators, and opportunities) | ||||||||

| 4. Structuring of the elements of the future business model in accordance with the expectations of the previous stage | ||||||||

| 5. Assessment of the company’s maturity for the transition to PSS (resources, capabilities, and tools) | ||||||||

| 6. Definition of actions to implement the PSS business model | ||||||||

| Block V–Elements of the Business Model | ||||||||

| With regard to the elements of the company’s business model from the perspective of PSS, the company considers the following to be important: | Level of relevance | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Not applicable | |||

| 1. Purpose of generating value for the consumer by reducing initial investment, guaranteeing operating costs, or minimizing risk for the customer throughout the life cycle with PSS | ||||||||

| 2. The goal of creating value through consumer use of the product | ||||||||

| 3. The intention to retain ownership of products and deliver service to the consumer | ||||||||

| 4. The goal of emphasizing service in the total offering to the consumer | ||||||||

| 5. Consumer participation in the design, production, sales, and delivery processes of products/services. | ||||||||

| 6. Sharing information with the consumer | ||||||||

| 7. Processes designed to create and deliver a value proposition that matches consumer needs and preferences. | ||||||||

| 8. Consumer segmentation and analysis processes to create specific value propositions. | ||||||||

| 9. Information and communication technologies for better communication/interaction with consumers and suppliers. | ||||||||

| 10. Information collected from consumers about product use to improve processes. | ||||||||

| 11. People trained to increase their service orientation at all levels. | ||||||||

| 12. Financial capacity to await the return on services. | ||||||||

| 13. Product design and development services. | ||||||||

| 14. Company design and engineering processes that enable the extension of service offerings and their integration with tangible components. | ||||||||

| 15. Ability to communicate the value of services to consumers, given the complexity of PSS offerings. | ||||||||

| 16. Monitoring of PSS delivery to consumers. | ||||||||

| 17. Integration of the sales/after-sales team with the research and development departments to develop PSS offerings | ||||||||

| 18. The development of collaborative networks among employees so that everyone is aware of their tasks throughout the product life cycle. | ||||||||

| 19. Relationships with partners in order to share information efficiently | ||||||||

| 20. A sales channel capable of conveying the value of the PSS offering to consumers. | ||||||||

| 21. Integrated sales and after-sales teams | ||||||||

| 22. Reorganized cost structure for service delivery. | ||||||||

| 23. Risk management to make PSS offers, unlike traditional product-only offers. | ||||||||

| 24. Management of your revenue structure in line with service integration. | ||||||||

| 25. Specific commercial agreements with consumers and suppliers to protect against problems arising from PSS offers, such as misuse of products. | ||||||||

References

- Abdulnour, S.; Baril, C.; Abdulnour, G.; Gamache, S. Implementation of industry 4.0 principles and tools: Simulation and case study in a manufacturing SME. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchard, S.; Gamache, S.; Abdulnour, G. Operationalizing mass customization in manufacturing SMEs—A systematic literature review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leipziger, M.; Kanbach, D.K.; Kraus, S. Business model transition and entrepreneurial small businesses: A systematic literature review. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2024, 31, 473–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrapa, L.H.; Assumpção, M.P.; Tasé Velázquez, D.R.; Gennaro, C.K.; de Oliveira, E.D. Product-Service System Modularization: A Systematic Review. In International Joint Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, M.S.S.; Andersen, A.L.; Nielsen, K.; Brunoe, T.D. Modularity in product-service systems: Literature review and future research directions. In IFIP International Conference on Advances in Production Management Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechuga, A.G.; Robles, G.C.; Soto, K.C.A.; Ackerman, M.A.M. The integration of the business model canvas and the service blueprinting to assist the conceptual design of new product-service systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 415, 137801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, P. A design method for edge–cloud collaborative product service system: A dynamic event-state knowledge graph-based approach with real case study. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2024, 62, 2584–2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalik, A.; Besenfelder, C.; Henke, M. Servitization of small-and medium-sized manufacturing enterprises: Facing barriers through the dortmund management model. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2019, 52, 2326–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åkesson, J.; Sundström, A.; Johansson, G.; Chirumalla, K.; Grahn, S.; Berglund, A. Design of product-service systems in SMEs: A review of current research and suggestions for future directions. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2024, 35, 874–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.Q.; Rich, N.; Found, P.; Kumar, M.; Brown, S. Exploring product–service systems in the digital era: A socio-technical systems perspective. TQM J. 2020, 32, 897–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokarz, B.; Kohlbeck, E.; Fagundes, A.B.; Pereira, D.; Beuren, F.H. Systematic literature review: Opportunities and trends to the post-outbreak period of COVID-19. Braz. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2021, 18, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labbate, R.; Silva, R.F.; Rampasso, I.S.; Anholon, R.; Quelhas, O.L.G.; Leal Filho, W. Business models towards SDGs: The barriers for operationalizing Product-Service System (PSS) in Brazil. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2021, 28, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. SME and Entrepreneurship Policy in Brazil 2020; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2020/04/sme-and-entrepreneurship-policy-in-brazil-2020_445942b8/cc5feb81-en.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Rampasso, I.S.; Siqueira, R.G.; Martins, V.W.; Anholon, R.; Quelhas, O.L.G.; Filho, W.L.; Salvia, A.L.; Santa-Eulalia, L.A. Implementing social projects with undergraduate students: An analysis of essential characteristics. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2021, 22, 198–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesus Pacheco, D.A.; ten Caten, C.S.; Jung, C.F.; Sassanelli, C.; Terzi, S. Overcoming barriers towards Sustainable Product-Service Systems in Small and Medium-sized enterprises: State of the art and a novel Decision Matrix. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 222, 903–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosenz, F.; Bivona, E. Fostering growth patterns of SMEs through business model innovation. A tailored dynamic business modelling approach. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 130, 658–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElNaggar, R.A.; ElSayed, M.F. Drivers of business model innovation in micro and small enterprises: Evidence from Egypt as an emerging economy. Future Bus. J. 2023, 9, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, V.R.; Carvalho, M.M.D.; Rotondaro, R.G. Product-service systems in a clinical laboratory: A case study. Production 2015, 26, 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Song, W.; Sakao, T. A customization-oriented framework for design of sustainable product/service system. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 1672–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clegg, B.; Little, P.; Govette, S.; Logue, J. Transformation of a small-to-medium-sized enterprise to a multi-organisation product-service solution provider. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 192, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ferreira Junior, R.; Scur, G.; Nunes, B. Preparing for smart product-service system (PSS) implementation: An investigation into the Daimler group. Prod. Plan. Control 2022, 33, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, V.R.; de Carvalho, M.M.; Ribeiro, J.L.D. Product-Service System–PSS: A Study of Business Drivers. 2013. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/271703163_Product-service_system_-_PSS_a_study_of_business_drivers (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Ghobakhloo, M.; Iranmanesh, M.; Vilkas, M.; Grybauskas, A.; Amran, A. Drivers and barriers of Industry 4.0 technology adoption among manufacturing SMEs: A systematic review and transformation roadmap. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2022, 33, 1029–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukker, A.; Tischner, U. Product-services as a research field: Past, present and future. Reflections from a decade of research. J. Clean. Prod. 2006, 14, 1552–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boons, F.; Montalvo, C.; Quist, J.; Wagner, M. Sustainable innovation, business models and economic performance: An overview. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 45, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukker, A. Product services for a resource-efficient and circular economy–A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 97, 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelini, G.; Moraes, R.N.; Cunha, R.N.; Costa, J.M.; Ometto, A.R. From linear to circular economy: PSS conducting the transition. Procedia CIRP 2017, 64, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.; De Pauw, I.; Bakker, C.; Van Der Grinten, B. Product design and business model strategies for a circular economy. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2016, 33, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Smart, P.; Kumar, M.; Jolly, M.; Evans, S. Product-service systems business models for circular supply chains. Prod. Plan. Control 2018, 29, 498–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa-Zomer, T.T.; Miguel, P.A.C. Exploring the critical factors for sustainable product-service systems implementation and diffusion in developing countries: An analysis of two PSS cases in Brazil. Procedia CIRP 2016, 47, 454–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catulli, M.; Cook, M.; Potter, S. Consuming use orientated product service systems: A consumer culture theory perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 141, 1186–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, M.P.; McAloone, T.C.; Pigosso, D.C. Configuring new business models for circular economy: From patterns and design options to action. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on New Business Models: New Business Models for Sustainable Entrepreneurship, Innovation, and Transformation, Berlin, Germany, 1–3 July 2019; Europe Business School: Munich, Germany, 2019; pp. 74–89. [Google Scholar]

- Orellano, M.; Neubert, G.; Gzara, L.; Le-Dain, M.A. Business Model configuration for PSS: An explorative study. Procedia CIRP 2017, 64, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annarelli, A.; Battistella, C.; Nonino, F.; Annarelli, A.; Battistella, C.; Nonino, F. How product service system can disrupt companies’ business model. In The Road to Servitization: How Product Service Systems Can Disrupt Companies’ Business Models; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 175–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, M.; Marques, C.; Campese, C.; Guzzo, D.; Mendes, G.; Costa, J.; Rosa, M.; de Oliveira, M.G.; Macul, V.; Rozenfeld, H. Transforming a traditional product offer into PSS: A practical application. Procedia CIRP 2016, 47, 412–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ayala, N.F.; Paslauski, C.A.; Ghezzi, A.; Frank, A.G. Knowledge sharing dynamics in service suppliers’ involvement for servitization of manufacturing companies. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 193, 538–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reim, W.; Parida, V.; Örtqvist, D. Product–Service Systems (PSS) business models and tactics–a systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 97, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukker, A. Eight types of product–service system: Eight ways to sustainability? Experiences from SusProNet. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2004, 13, 246–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrodegari, F.; Pashou, T.; Saccani, N. Business model innovation: Process and tools for service transformation of industrial firms. Procedia CIRP 2017, 64, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orellano, M.; Medini, K.; Lambey-Checchin, C.; Neubert, G. A system modelling approach to collaborative PSS design. Procedia CIRP 2019, 83, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortoluzzi, G.; Chiarvesio, M.; Romanello, R.; Tabacco, R.; Veglio, V. Servitisation and performance in the business-to-business context: The moderating role of Industry 4.0 technologies. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2022, 33, 108–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annarelli, A.; Battistella, C.; Nonino, F. Product service system: A conceptual framework from a systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 139, 1011–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pessôa, M.V.P.; Becker, J.M.J. Overcoming the product-service model adoption obstacles. Procedia CIRP 2017, 64, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Lin, L. Evaluating the Whole-Process Management of Future Communities Based on Integrated Fuzzy Decision Methods. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, T.J.; Pipino, L.L.; Van Gigch, J.P. A pilot study of fuzzy set modification of Delphi. Hum. Syst. Manag. 1985, 5, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrudi, S.H.H.; Ghomi, H.; Mazaheriasad, M. An Integrated Fuzzy Delphi and Best Worst Method (BWM) for performance measurement in higher education. Decis. Anal. J. 2022, 4, 100121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rejeb, A.; Rejeb, K.; Keogh, J.G.; Zailani, S. Barriers to blockchain adoption in the circular economy: A fuzzy Delphi and best-worst approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawood, K.A.; Sharif, K.Y.; Ghani, A.A.; Zulzalil, H.; Zaidan, A.A.; Zaidan, B.B. Towards a unified criteria model for usability evaluation in the context of open source software based on a fuzzy Delphi method. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2021, 130, 106453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, K.; Bigdeli, A.Z.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Schroeder, A.; Beltagui, A.; Baines, T. A socio-technical view of platform ecosystems: Systematic review and research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 128, 94–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, J.Z.; Hsieh, C.C. Fuzzy Delphi Evaluation on Long-Term Care Nurse Aide Platform: Socio-Technical Approach for Job Satisfaction and Work Effectiveness. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2025, 8, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnavas, S.I.; Peteinatos, I.; Kyriazis, A.; Barbounaki, S.G. Using fuzzy multi-criteria decision-making as a human-centered AI approach to adopting new technologies in maritime education in Greece. Information 2025, 16, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.K.; Sarkar, P. A framework based on fuzzy Delphi and DEMATEL for sustainable product development: A case of Indian automotive industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 246, 118991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Zavadskas, E.K.; Mangla, S.K.; Agrawal, V.; Sharma, K.; Gupta, D. When risks need attention: Adoption of green supply chain initiatives in the pharmaceutical industry. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 3554–3576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, D.A.L.; Muritiba, S.N.; Muritiba, P.M. Taxonomy of company size in research: Characterizing Medium-sized Enterprises. Hermes Sci. J. 2017, 19, 536–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ministry of Economy, Special Secretariat for Productivity and Competitiveness. Company Map: Bulletin for the First Four Months of 2025 (1st ed.). 2025. Available online: https://www.gov.br/empresas-e-negocios/pt-br/mapa-de-empresas/boletins/mapa-de-empresas-boletim-1o-quadrimestre-2025-pdf.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2025).[Green Version]

- Neves, M.L.; Cruz, P.B.D.; Locatelli, O. Factors influencing the survival of micro and small businesses in Brazil. RAM. Mackenzie Manag. J. 2024, 25, eRAMC240073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suaily, S.; Ismail, S.Z. Development of Product Service System Modelling in SMED: The Case of Inventory Control. J. Mod. Manuf. Syst. Technol. 2018, 1, 94–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Lu, C.; Jiang, S. An iterative design method from products to product service systems—Combining acceptability and sustainability for manufacturing SMEs. Sustainability 2022, 14, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herceg, I.V.; Kuč, V.; Mijušković, V.M.; Herceg, T. Challenges and driving forces for industry 4.0 implementation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le-Dain, M.A.; Benhayoun, L.; Matthews, J.; Liard, M. Barriers and opportunities of digital servitization for SMEs: The effect of smart Product-Service System business models. Serv. Bus. 2023, 17, 359–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Torró, V.; Calafat-Marzal, C.; Guaita-Martinez, J.; Vega, V. Assessment of European countries’ national circular economy policies. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casidy, R.; Nyadzayo, M. Drivers and outcomes of relationship quality with professional service firms: An SME owner-manager perspective. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2019, 78, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Solis, E.R.; Llonch-Andreu, J.; Malpica-Romero, A.D. Relational capital and strategic orientations as antecedents of innovation: Evidence from Mexican SMEs. J. Innov. Entrep. 2022, 11, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrizio, C.M.; Kaczam, F.; de Moura, G.L.; da Silva, L.S.C.V.; da Silva, W.V.; da Veiga, C.P. Competitive advantage and dynamic capability in small and medium-sized enterprises: A systematic literature review and future research directions. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2022, 16, 617–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otache, I. Innovation capability, strategic flexibility and SME performance: The roles of competitive advantage and competitive intensity. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Stud. 2024, 15, 248–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yusof, R.N.R.; Jaharuddin, N.S. Driving SMEs’ Sustainable Competitive Advantage: The Role of Service Innovation, Intellectual Property Protection, Continuous Innovation Performance, and Open Innovation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meirelles, D.S.E. Business Model and Strategy: In search of dialog through value perspective. Rev. Adm. Contemp. 2019, 23, 786–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, A.F.; Hollnagel, H.C.; Santos, F.D.A. Servitization as a Circular Economy Strategy: A Brazilian Tertiary Packaging Industry for Logistics and Transportation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, R.; Figueiredo, F.; Nunes, J. Product-services for a resource-efficient and circular economy: An updated review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitake, Y.; Hiramitsu, K.; Tsutsui, Y.; Sholihah, M.A.; Shimomura, Y. A Strategic Planning Method to Guide Product—Service System Development and Implementation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrayati, H.; Marimon, F.; Hwang, W.Y.; Yuliawati, T.; Susanto, P.; Rahmiati, R. Customer relationship management and value creation as key mediators of female-owned MSMEs’ market performance. J. Innov. Entrep. 2025, 14, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulkepli, Z.H.; Hasnan, N.; Mohtar, S. Communication and service innovation in small and medium enterprises (SMEs). Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 211, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzingirai, M.; Sikomwe, S.; Tshuma, N. Corporate Governance Challenges for Small and Medium Enterprises in the Constrained Zimbabwean Economy. Int. J. Appl. Manag. Sci. Eng. 2022, 9, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlbeck, E.; Cauchick-Miguel, P.A.; Mendes, G.H.D.S.; Zomer, T.T.D.S. A longitudinal history-based review of the product-service system: Past, present, and future. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassanelli, C.; Da Costa Fernandes, S.; Rozenfeld, H.; Mascarenhas, J.; Terzi, S. Enhancing knowledge management in the PSS detailed design: A case study in a food and bakery machinery company. Concurr. Eng. 2021, 29, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, I.C.; Kohlbeck, E.; Beuren, F.H.; Fagundes, A.B.; Pereira, D. Life cycle analysis of electronic products for a product-service system. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 314, 127926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Confente, I.; Buratti, A.; Russo, I. The role of servitization for small firms: Drivers versus barriers. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2015, 26, 312–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number of Employees | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Until 19 | 4 | 40.00% |

| From 20 to 99 | 5 | 50.00% |

| From 100 to 499 | 1 | 10.00% |

| Total | 10 | 100.00% |

| Age Range (in Years) | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Up to 10 years | 1 | 10% |

| 11 to 50 years | 8 | 80% |

| Over 50 years | 1 | 10% |

| Total | 10 | 100% |

| Industry | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Industrial Assembly | 1 | 10.00% |

| Component Industry | 1 | 10.00% |

| Metallurgical Industry | 1 | 10.00% |

| Rubber Industry | 1 | 10.00% |

| Industrial Equipment | 2 | 20.00% |

| Metalworking Industry | 1 | 10.00% |

| Industrial Transport Equipment | 1 | 10.00% |

| Food Industry | 1 | 10.00% |

| Industrial Ventilation Equipment | 1 | 10.00% |

| Total | 10 | 100.00% |

| Number of Specialists | TFN | Grade Assigned |

|---|---|---|

| Expert 1 | (0.7; 0.9; 0.9) | [Note 5] |

| Expert 2 | (0.3; 0.5; 0.7) | [Note 3] |

| Expert 3 | (0.7; 0.9; 0.9) | [Note 5] |

| Expert 4 | (0.3; 0.5; 0.7) | [Note 3] |

| Expert 5 | (0.3; 0.5; 0.7) | [Note 3] |

| Expert 6 | (0.5; 0.7; 0.9) | [Note 4] |

| Expert 7 | (0.5; 0.7; 0.9) | [Note 4] |

| Expert 8 | (0.5; 0.7; 0.9) | [Note 4] |

| Expert 9 | (0.7; 0.9; 0.9) | [Note 5] |

| Expert 10 | (0.5; 0.7; 0.9) | [Note 4] |

| TFN corresponding | (0.3; 0.7; 0.9) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Favarin, R.R.; Kneipp, J.M.; Araujo, A.R.d.; Bichueti, R.S.; Gomes, C.M.; Frizzo, K.; Carvalho, L.M.C. A Proposal of an Integrated Framework for the Strategic Implementation of Product-Service Systems in Brazilian Industrial Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10020. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210020

Favarin RR, Kneipp JM, Araujo ARd, Bichueti RS, Gomes CM, Frizzo K, Carvalho LMC. A Proposal of an Integrated Framework for the Strategic Implementation of Product-Service Systems in Brazilian Industrial Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Sustainability. 2025; 17(22):10020. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210020

Chicago/Turabian StyleFavarin, Rodrigo Reis, Jordana Marques Kneipp, Andreza Rodrigues de Araujo, Roberto Schoproni Bichueti, Clandia Maffini Gomes, Kamila Frizzo, and Luísa Margarida Cagica Carvalho. 2025. "A Proposal of an Integrated Framework for the Strategic Implementation of Product-Service Systems in Brazilian Industrial Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises" Sustainability 17, no. 22: 10020. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210020

APA StyleFavarin, R. R., Kneipp, J. M., Araujo, A. R. d., Bichueti, R. S., Gomes, C. M., Frizzo, K., & Carvalho, L. M. C. (2025). A Proposal of an Integrated Framework for the Strategic Implementation of Product-Service Systems in Brazilian Industrial Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Sustainability, 17(22), 10020. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210020