Protection of Personal Information Act in Practice: A Systematic Synthesis of Research Trends, Sectoral Applications, and Implementation Barriers in South Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. POPIA’s Eight Principles of Lawful Processing

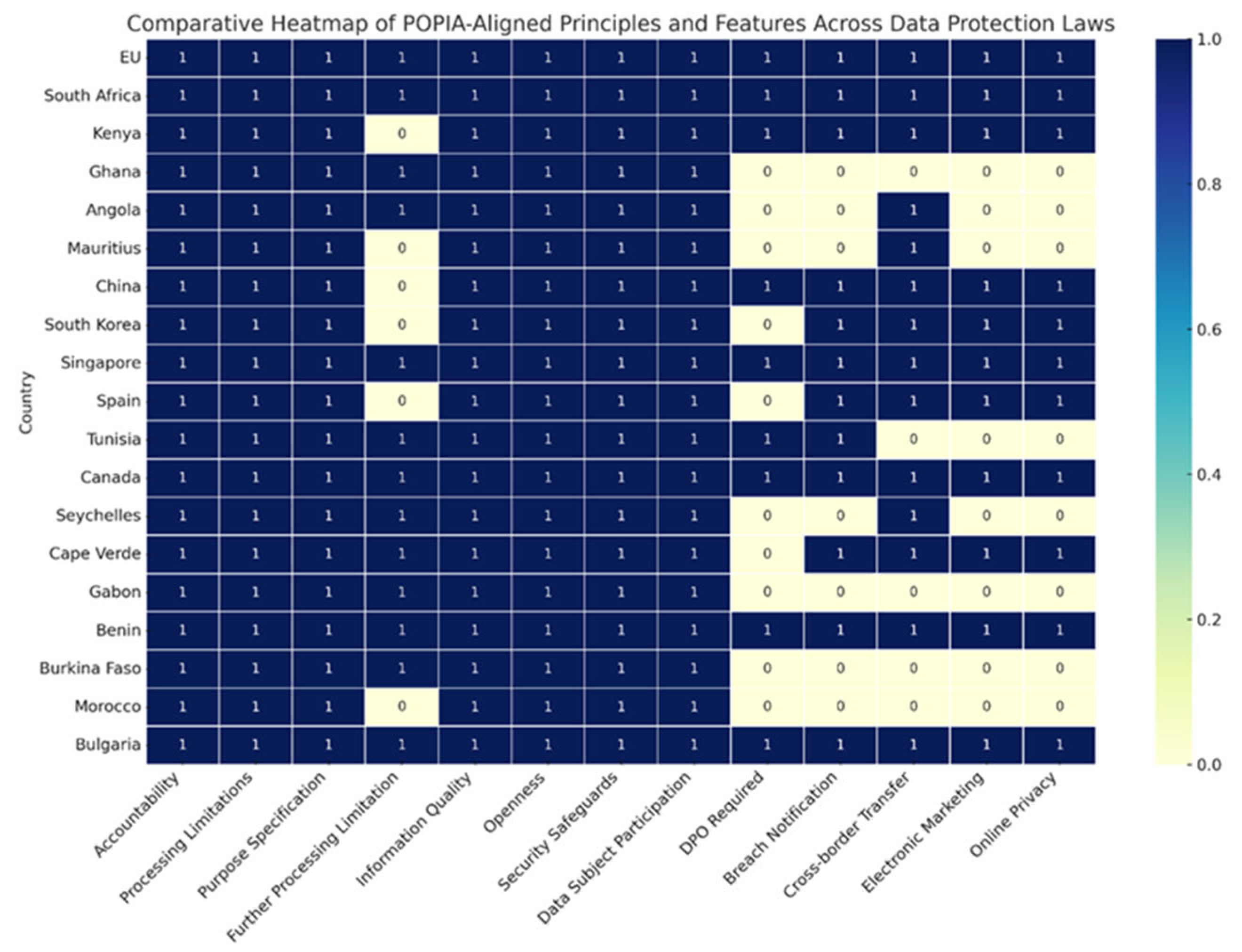

2.2. POPIA Principles in Comparison with International Data Protection Laws

3. Methodology

3.1. Identification

3.2. Screening

3.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

- Published in English.

- Published between 2014 and 2025 (POPIA was signed into law in 2013 and became enforceable in 2021).

- Explicitly focus on POPIA compliance or implementation within South African organizations or systems.

- Include journal articles, conference papers, reviews, book chapters, and notes.

- Are available in full-text and open-access formats.

3.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

- Non-English publications.

- Studies unrelated to POPIA or not addressing implementation/compliance.

- Non-academic content (e.g., blog posts and editorials).

- Duplicate entries.

- Restricted-access or inaccessible full-text articles.

3.3. Eligibility and Study Selection

3.4. Inclusion Criteria and Data Extraction

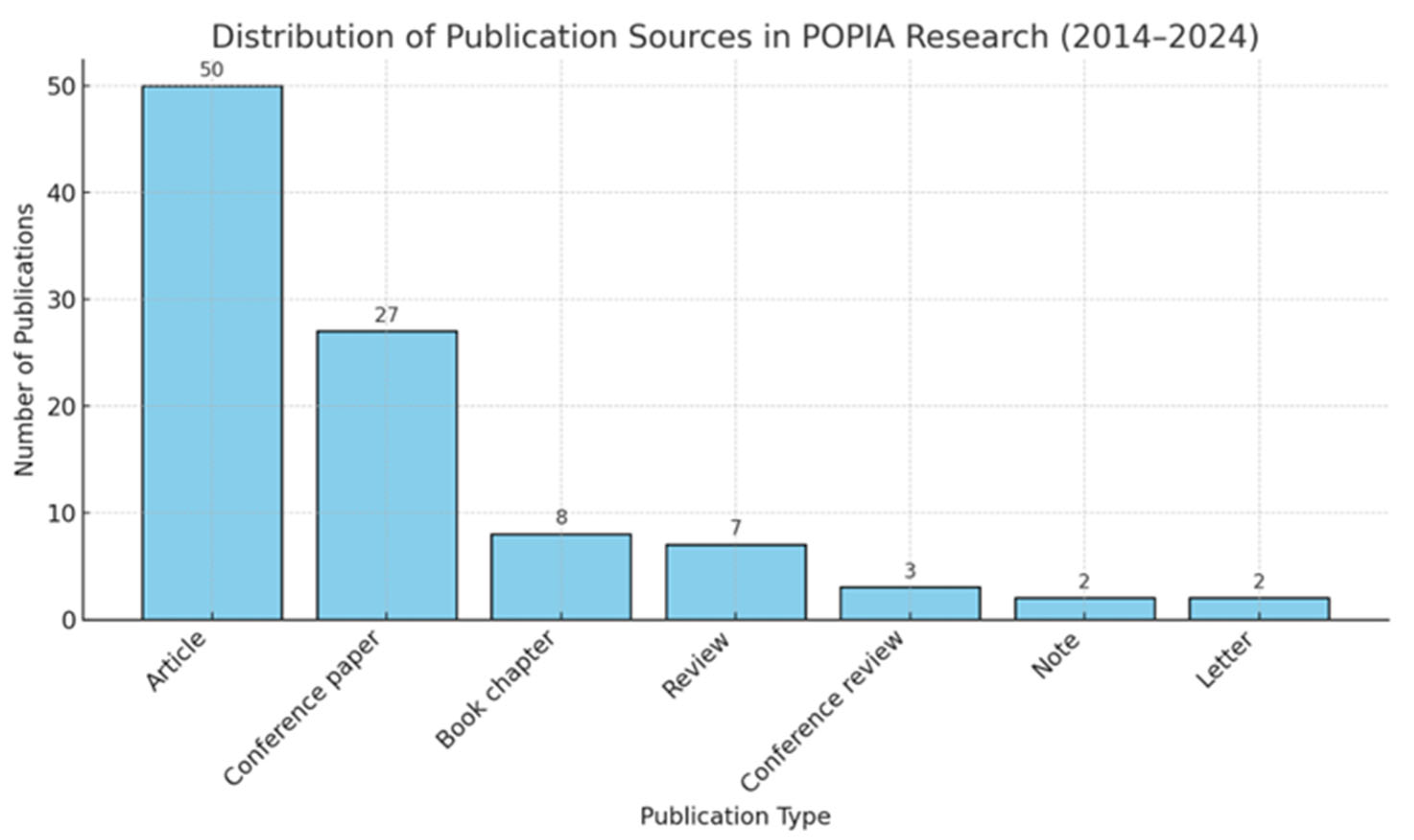

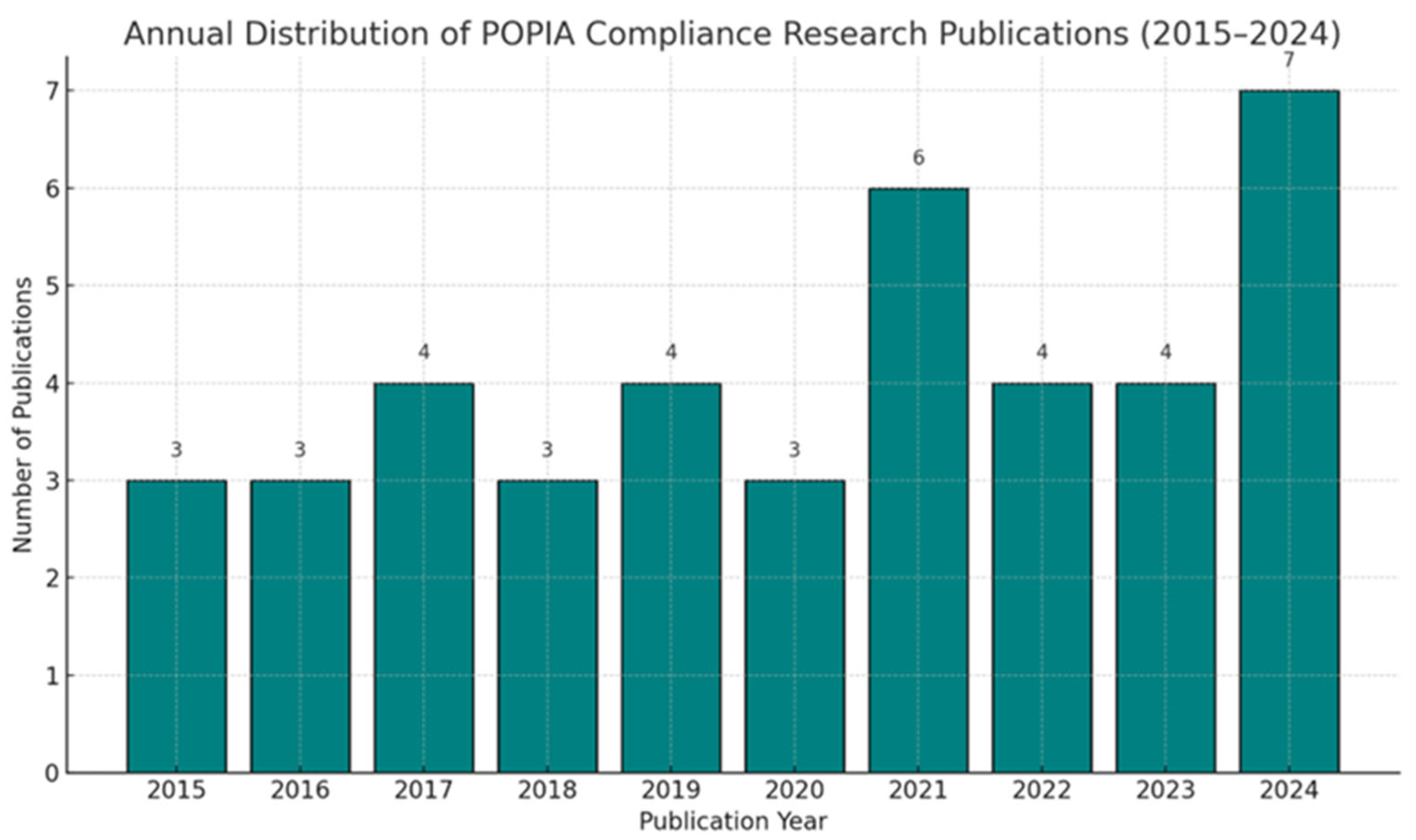

3.5. Data Extraction Table and Characteristics of Included Studies

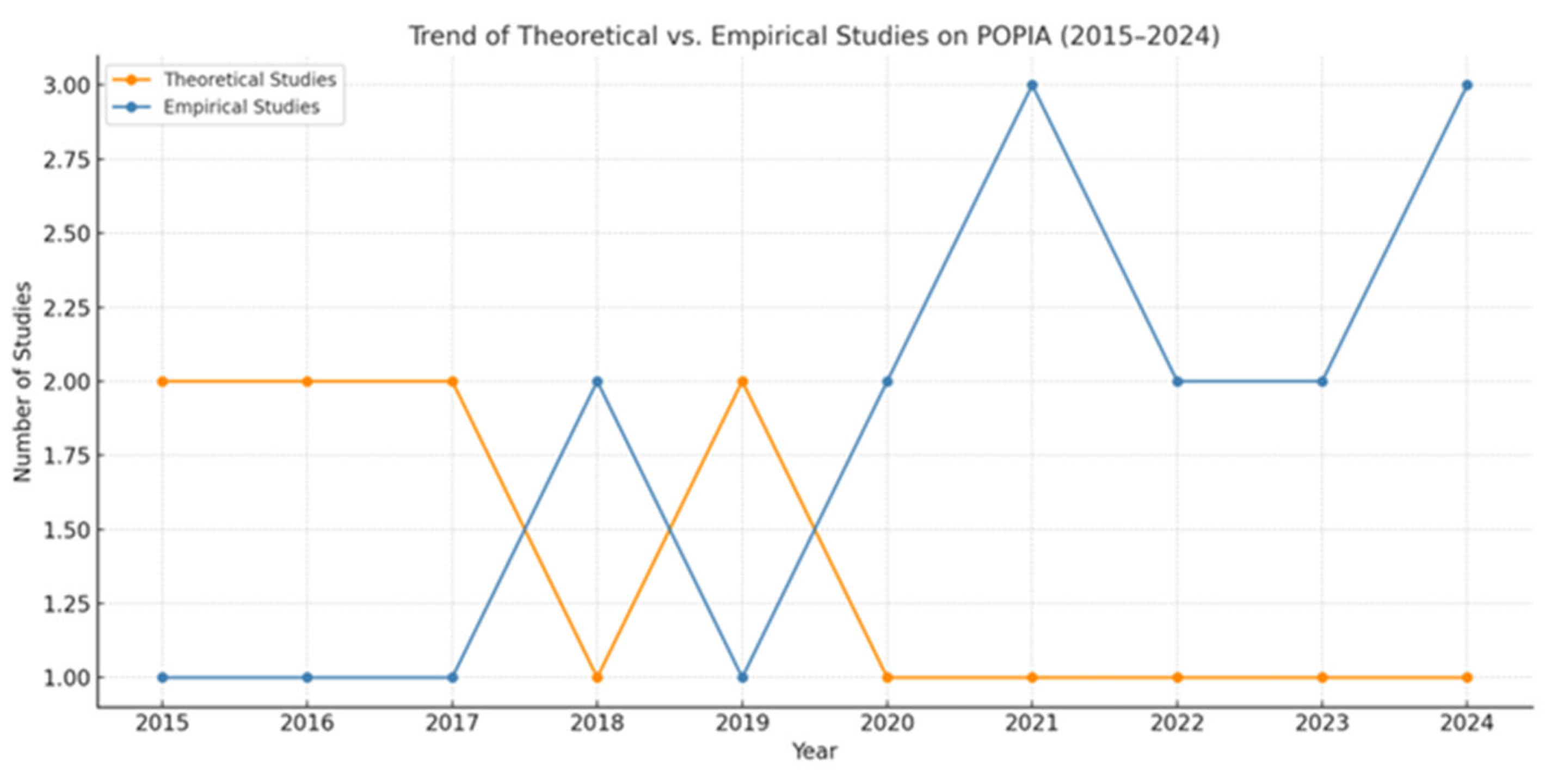

3.5.1. Annual Research Output Trends (2015–2024)

3.5.2. Citation Distribution by Study Type

- Literature reviews and theoretical studies tend to have higher median citation counts, reflecting their broad utility and reference value.

- Empirical and qualitative studies show variable citation performance, suggesting sector-specific or context-sensitive relevance.

- Case studies and scoping reviews have moderate but consistent citation values.

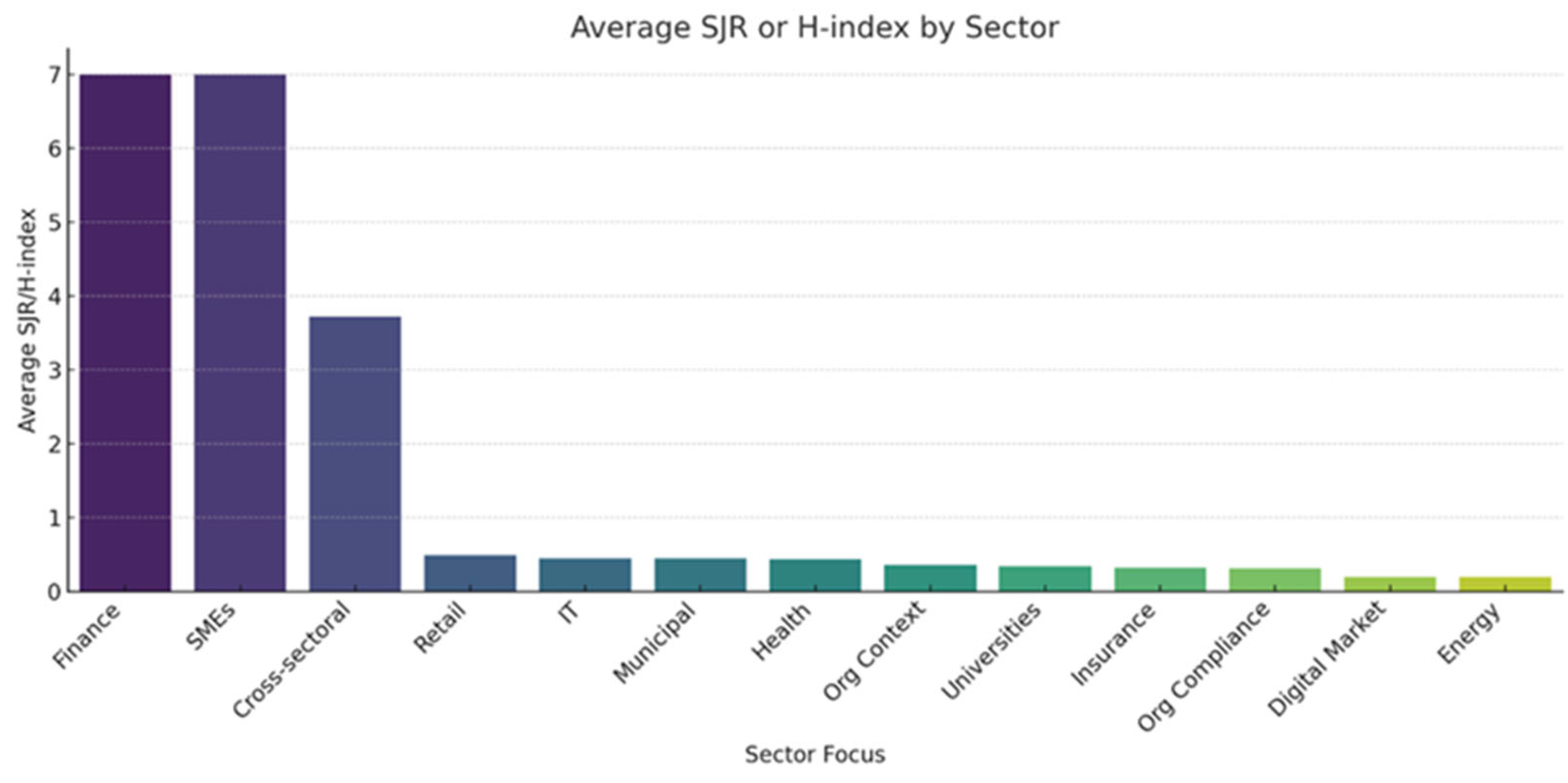

3.5.3. Sectoral Quality (Average SJR/H-Index)

- (i)

- Local or niche dissemination—Many of these studies are published in South African or regional journals with lower international citation indices.

- (ii)

- Applied rather than theoretical focus—Sector-specific implementation research may be tailored for practitioner audiences, limiting publication in high-impact academic outlets.

- (iii)

- Lower global resonance—Certain domains, such as municipal governance or local retail, may have limited appeal beyond the national context, reducing opportunities for placement in top-tier, internationally indexed journals.

- (iv)

- Emerging research maturity—In fields like digital marketplaces or energy, POPIA-focused research is still in its early stages, with relatively few contributions achieving methodological or conceptual maturity that meets high-impact journal thresholds.

4. Risk of Bias/Quality Assessment

4.1. Quality Assessment Using a Modified Likert Approach

4.2. Quality Assessment and Inter-Rater Reliability

- Reviewer A—PhD candidate in information governance, specializing in African data protection frameworks.

- Reviewer B—Legal scholar in data protection and privacy law.

- Reviewer C—Professor of Computer Science with extensive SLR and bibliometric analysis experience.

5. Results

5.1. RQ1: What Are the Dominant Thematic Trends in the Scholarly Literature on POPIA’s Implementation and Compliance?

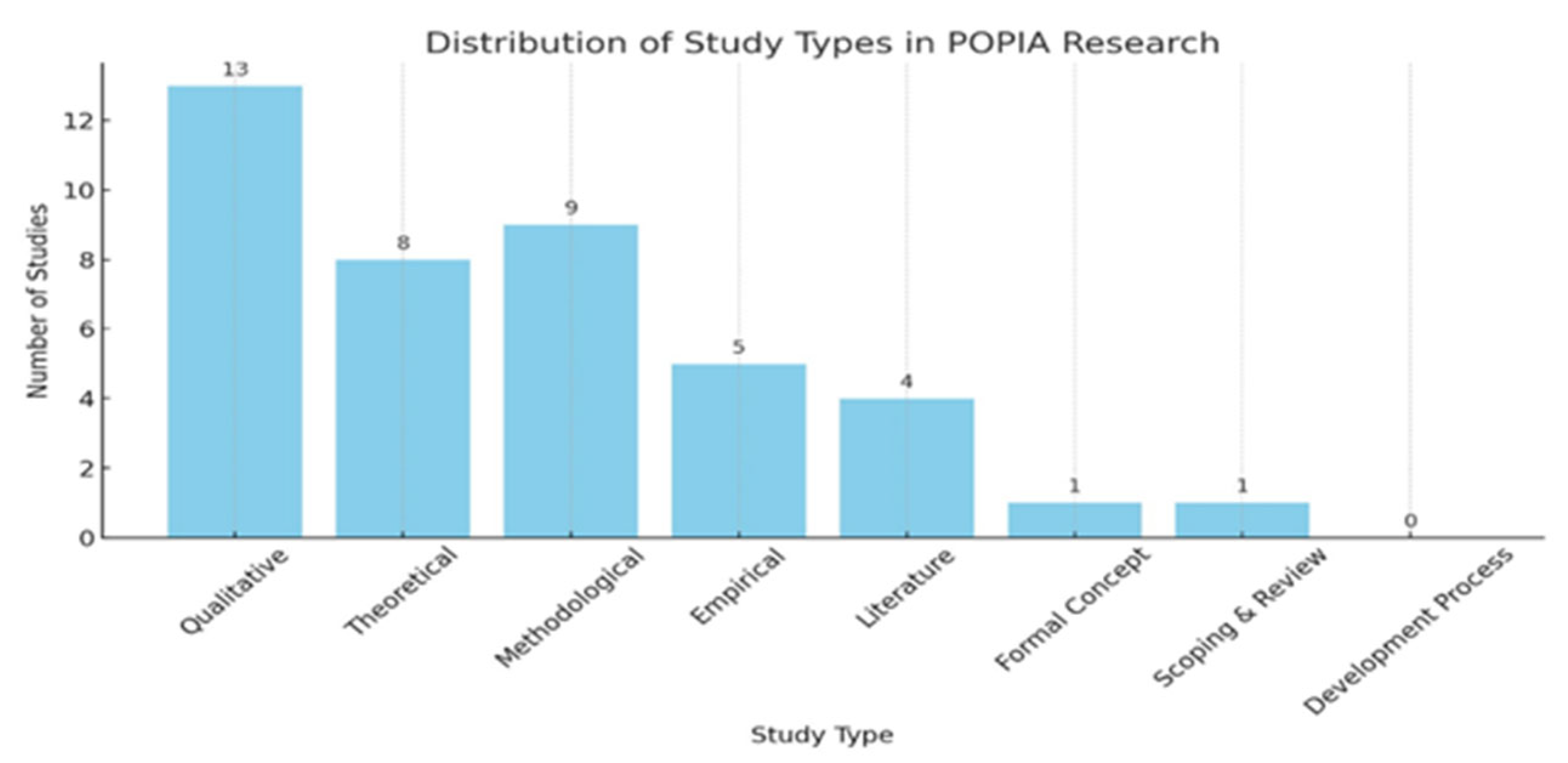

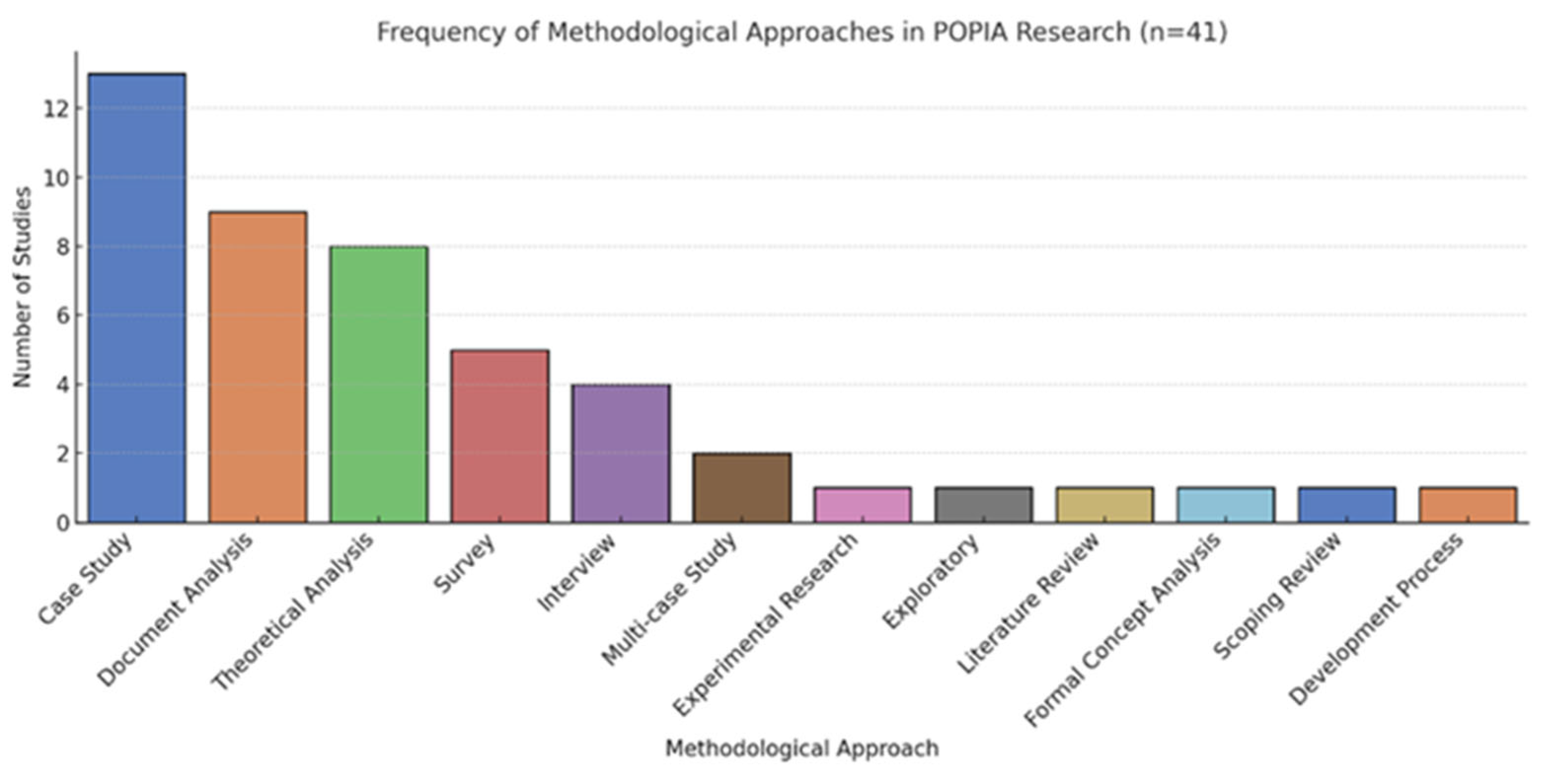

5.2. RQ2: What Methodological Trends and Approaches Are Used in These Studies?

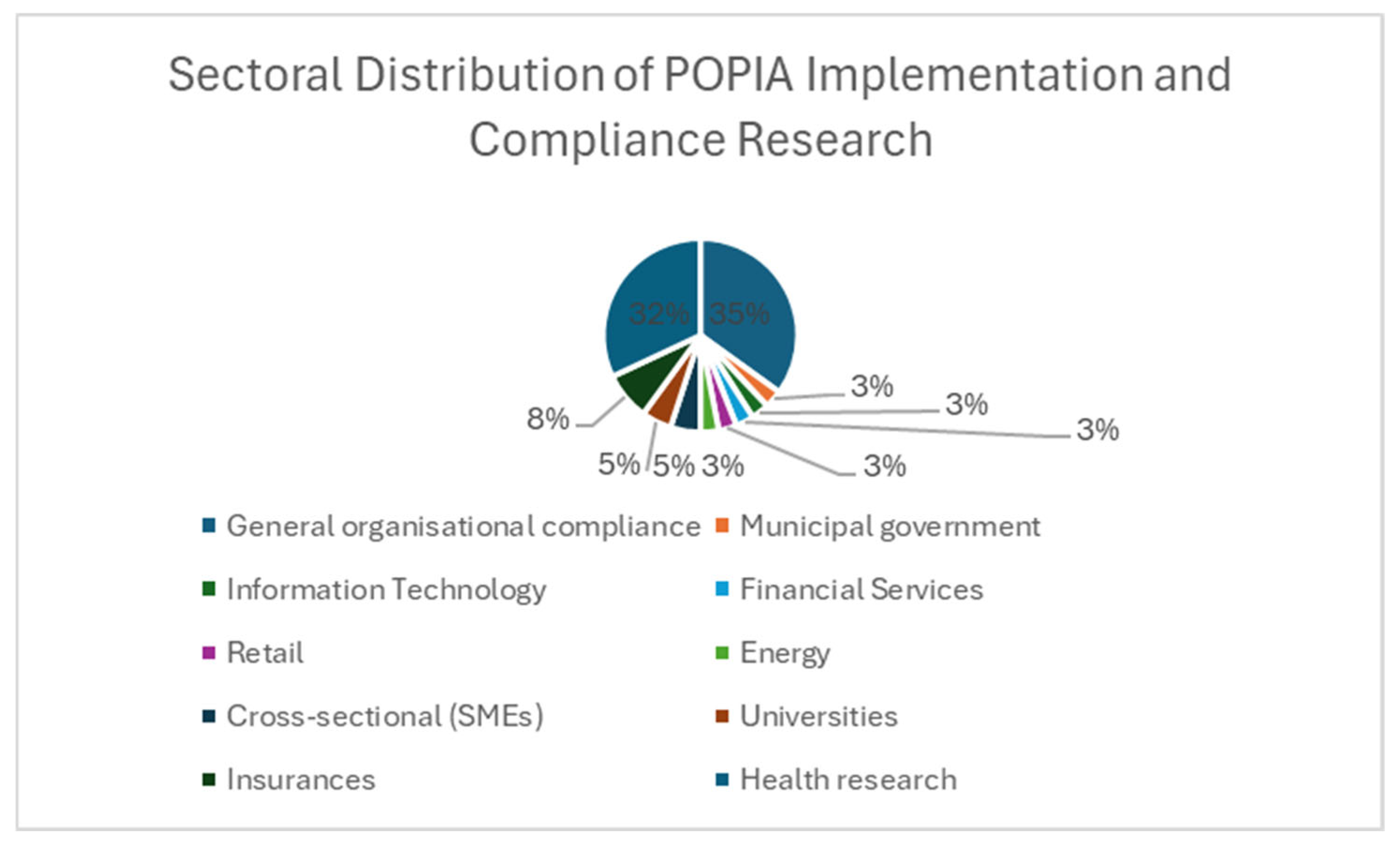

5.3. RQ3: Which Sectors Are Most Frequently Studied in POPIA Implementation, Compliance, and Cross-Cutting Implementation Barriers Research?

5.4. Emerging Dimensions for Future Literature Mapping

6. Discussion

- (i)

- Establishment of sector-specific compliance benchmarks by the Information Regulator.

- (ii)

- Introduction of national POPIA awareness campaigns using public media and community ICT centers.

- (iii)

- Development of an open-access POPIA compliance maturity toolkit for SMEs;

- (iv)

- Facilitation of data governance incubator programs at universities to build technical and legal capacity.

7. Conclusions and Future Work

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hashmi, M.; Governatori, G.; Lam, H.P.; Wynn, M.T. Are we done with business process compliance: State of the art and challenges ahead. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 2018, 57, 79–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandeh, A.T.; Botha, R.A.; Futcher, L.A. Enforcement of the Protection of Personal Information (POPI) Act: Perspective of data management professionals. S. Afr. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netshakhuma, N.S. Assessment of a South Africa national consultative workshop on the Protection of Personal Information Act (POPIA). Glob. Knowl. Mem. Commun. 2020, 69, 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbonye, V.; Moodley, M.; Nyika, F. Examining the applicability of the Protection of Personal Information Act in AI-driven environments. S. Afr. J. Inf. Manag. 2024, 26, 1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botha, J.; Grobler, M.M.; Hahn, J.; Eloff, M. A High-Level Comparison Between the South African Protection of Personal Information Act and International Data Protection Laws. In Proceedings of the ICMLG2017 5th International Conference on Management Leadership and Governance, Johannesburg, South Africa, 16–17 March 2017; p. 57. [Google Scholar]

- South Africa, Department of Justice. Government Gazette; Protection of Personal Information Act 2013; South African Government: Cap Town, South Africa, 2013; p. 37067. [Google Scholar]

- Staunton, C.; Tschigg, K.; Sherman, G. Data protection, data management, and data sharing: Stakeholder perspectives on the protection of personal health information in South Africa. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0260341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swales, L. The Protection of Personal Information Act 4 of 2013 in the context of health research: Enabler of privacy rights or roadblock? Potchefstroom Electron. Law J. Potchefstroomse Elektron. Regsblad 2022, 25, 236881. [Google Scholar]

- Raaff, E.; Rothwell, N.; Wynne, A. Aligning South African Data and Cloud Policy with the POPI Act. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Cyber Warfare and Security, Albany, NY, USA, 17–18 March 2022; Academic Conferences International Limited: Reading, UK, 2022; Volume 17, pp. 279–287. [Google Scholar]

- Thaldar, D.; Townsend, B. Exempting health research from the consent provisions of POPIA. Potchefstroom Electron. Law J. Potchefstroomse Elektron. Regsblad 2021, 24, 235940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staunton, C.; Adams, R.; Botes, M.; De Vries, J.; Labuschaigne, M.; Loots, G.; Mahomed, S.; Loideain, N.N.; Olckers, A.; Pepper, M.S.; et al. Enabling the Use of Health Data for Research: Developing a POPIA Code of Conduct for Research in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Bioeth. Law 2021, 14, 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Da Veiga, A.; Vorster, R.; Pilkington, C.; Abdullah, H. Compliance with the Protection of Personal Information Act and Consumer Privacy Expectations: A Comparison Between the Retail and Medical AID industry. In Proceedings of the 2017 Information Security for South Africa (ISSA), Johannesburg, South Africa, 16–17 August 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA; pp. 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Da Veiga, A.; Vorster, R.; Li, F.; Clarke, N.; Furnell, S.M. Comparing the Protection and Use of Online Personal Information in South Africa and the United Kingdom in Line with Data Protection Requirements. Inf. Comput. Secur. 2019, 28, 399–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moabalobelo, T.; Ngobeni, S.; Molema, B.; Pantsi, P.; Dlamini, M.; Nelufule, N. Towards a Privacy Compliance Assessment Toolkit. In Proceedings of the 2023 IST-Africa Conference (IST-Africa), Tshwane, South Africa, 31 May 2023–2 June 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Buys, M. Protecting personal information: Implications of the Protection of Personal Information (POPI) Act for healthcare professionals. S. Afr. Med. J. 2017, 107, 954–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Govender, I. 2015, August. Mapping ‘Security Safeguard’ Requirements in a Data Privacy Legislation to an International Privacy Framework: A Compliance Methodology. In Proceedings of the 2015 Information Security for South Africa (ISSA), Johannesburg, South Africa, 12–13 August 2015; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Chimboza, T.; Smith, E. How Does Compliance with the Protection of Personal Information Act (POPI Act) Affect Organisations in South Africa? In Proceedings of the 10th Annual ACIST Proceedings (2024), Virtual, 12 September 2024. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- De Bruyn, M. The Protection of Personal Information (POPI) Act—Impact On South Africa. Int. Bus. Econ. Res. J. (Online) 2014, 13, 1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafta, Y.; Leenen, L.; Chan, P. An Ontology for the South African Protection of Personal Information Act. In Proceedings of the ECCWS 2020 19th European Conference on Cyber Warfare and Security, Chester, UK, 25–26 June 2020; Volume 2020, pp. 158–167. [Google Scholar]

- Coetzee, J. Cross-Border Data Flows the Protection of Personal Information Act 4 of 2013-Part II: The Data Transfer Provision. Potchefstroom Electron. Law J. (PELJ) 2024, 27, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraka, L.I.; Singh, U.G. The POPIA 7th Condition Framework for SMEs in Gauteng. In Computational Intelligence: Select Proceedings of InCITe 2022; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 831–838. [Google Scholar]

- Pittman, F.P.; Hafiz, A.; Hamm, A. Data Protection Laws and Regulations USA 2024; White & Case LLP: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, B. Is POPIA bad business for South Africa? Comparing the GDPR to POPIA and analyzing POPIA’s impact on businesses in South Africa. Penn State J. Law Int. Aff. 2022, 10, 218. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baloyi, N.; Kotzé, P. Are Organisations in South Africa Ready to Comply with Personal Data Protection or Privacy Legislation and Regulations? In Proceedings of the 2017 IST-Africa Week Conference (IST-Africa), Windhoek, Namibia, 30 May–2 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Da Veiga, A.; Vorster, R.; Li, F.; Clarke, N.; Furnell, S. A Comparison of Compliance with Data Privacy Requirements in Two Countries. In Proceedings of the ECIS 2018: 26th European Conference on Information Systems: Beyond Digitization-Facets of Socio-Technical Change, Portsmouth, UK, 23–28 June 2018; University of Portsmouth: Portsmouth, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Da Veiga, A.; Ochola, E.; Mujinga, M.; Mwim, E. Investigating Data Privacy Evaluation Criteria and Requirements for e-Commerce Websites. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advanced Research in Technologies, Information, Innovation and Sustainability, Cartagena de Indias, Colombia, 21–23 October 2025; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 297–307. [Google Scholar]

- Kumalo, M.O.; Botha, R.A. POPIA Compliance in Digital Marketplaces: An IGOE Framework for Pattern Language Development. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference of South African Institute of Computer Scientists and Information Technologists, Gqeberha, South Africa, 15–17 July 2024; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 331–346. [Google Scholar]

- Bredenkamp, I.E.; Kritzinger, E.; Herselman, M. A conceptual framework for consumer is compliance awareness: South African government context. In Proceedings of the Informatics and Cybernetics in Intelligent Systems. CSOC 2021, Online, 15–16 July 2021; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; Volume 3, pp. 682–701. [Google Scholar]

- Mbonye, V.; Subramaniam, P.R.; Padayachee, I. POPIA compliant regulatory framework for smart grids to secure gaps in existing privacy laws. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Big Data, Computing and Data Communication Systems (icABCD), Durban, South Africa, 5–6 August 2021; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Malepeng, P.; Speckman, T.; Gerber, M. An Assessment of POPIA Compliance in Case 1 Municipal Fresh Produce Market. In Proceedings of the 2024 IST-Africa Conference (IST-Africa), Dublin, Ireland, 20–24 May 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Tsegaye, T.; Flowerday, S. PoPI Compliance Through Access Control of Electronic Health Records. In Proceedings of the South African Institute of Computer Scientists and Information Technologists, Skukuza, South Africa, 17–18 September 2019; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Arthur, J. The protection of personal information act compliance and requirements for higher education institutions: Pre covid. S. Afr. J. High. Educ. 2021, 35, 221–237. [Google Scholar]

- Hertzog, L.; Wittesaele, C.; Titus, R.; Chen, J.J.; Kelly, J.; Langwenya, N.; Baerecke, L.; Toska, E. Seven essential instruments for POPIA compliance in research involving children and adolescents in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2021, 117, 9–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botha, J.; Eloff, M.M.; Swart, I. Evaluation of Online Resources on the Implementation of the Protection of Personal Information Act in South Africa. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Cyber Warfare and Security: ICCWS2015, Kruger National Park, South Africa, 24–25 March 2015; p. 39. [Google Scholar]

- Botha, J.G.; Eloff, M.M.; Swart, I. The Effects of the PoPI Act on Small and Medium Enterprises in South Africa. In Proceedings of the 2015 Information Security for South Africa (ISSA), Johannesburg, South Africa, 12–13 August 2015; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Staunton, C.; De Stadler, E. Protection of Personal Information Act No. 4 of 2013: Implications for biobanks. S. Afr. Med. J. 2019, 109, 232–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staunton, C.; Adams, R.; Anderson, D.; Croxton, T.; Kamuya, D.; Munene, M.; Swanepoel, C. Protection of Personal Information Act 2013 and data protection for health research in South Africa. Int. Data Priv. Law 2020, 10, 160–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaldar, D. Does data protection law in South Africa apply to pseudonymised data? Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1238749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theys, M.W.; Ruhode, E.; Harpur, P. May. Challenges of Implementation of Data Protection Legislation in a South African context. In Proceedings of The 11th International Conference on Research in Science and Technology, Paris, France, 14–16 May 2021; Diamond Scientific Publishing: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2021; pp. 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Bronstein, V. Prioritising Command-and-Control Over Collaborative Governance: The Role of the Information Regulator Under the Protection of Personal Information Act. Potchefstroom Electron. Law J. (PELJ) 2022, 25, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legodi, S.F.; Abdullah, H. Assessing the Impact of Information Privacy Protection Awareness Among Online Users and Consumers. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Mysore Sub Section International Conference (MysuruCon), Hassan, India, 24–25 October 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 498–504. [Google Scholar]

- Sekgweleo, T.; Mariri, M. Critical analysis of PoPI Act within the organisation. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Inf. Secur. (IJCSIS) 2019, 17, 64–69. [Google Scholar]

- Dala, P.; Venter, H.S. Understanding the Level of Compliance by South African Institutions to the Protection of Personal Information (POPI) Act. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the South African Institute of Computer Scientists and Information Technologists, Johannesburg, South Africa, 26–28 September 2016; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Katurura, M.; Cilliers, L. The Extent to Which the POPI Act Makes Provision for Patient Privacy in Mobile Personal Health Record Systems. In Proceedings of the 2016 IST-Africa Week Conference, Durban, South Africa, 11–13 May 2016; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Pelteret, M.; Ophoff, J. Organizational Information Privacy Strategy and the Impact of the PoPI Act. In Proceedings of the 2017 Information Security for South Africa (ISSA), Johannesburg, South Africa, 16–17 August 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 56–65. [Google Scholar]

- Scharnick, N.; Gerber, M.; Futcher, L. Review of Data Storage Protection Approaches for POPI Compliance. In Proceedings of the 2016 Information Security for South Africa (ISSA), Johannesburg, South Africa, 17–18 August 2016; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 48–55. [Google Scholar]

- De Waal, P.J. The protection of personal information act (POPIA) and the promotion of access to information act (PAIA): It is time to take note. Curr. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2022, 35, 232–236. [Google Scholar]

- Zenda, B.; Vorster, R.; Da Viega, A. Protection of personal information: An experiment involving data value chains and the use of personal information for marketing purposes in South Africa. S. Afr. Comput. J. 2020, 32, 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaddu, S.; Ssekitto, F. Africa’s Data Privacy Puzzle: Data Privacy Laws and Compliance in Selected African Countries. Univ. Dar Salaam Libr. J. 2023, 18, 264002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A.; Kale, S.; Chandel, S.; Pal, D.K. Likertscale: Explored and explained. Br. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2015, 7, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. An Application of Hierarchical Kappa-Type Statistics in the Assessment of Majority Agreement among Multiple Observers. Biometrics 1977, 33, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Veiga, A.; Abdullah, H.; Eybers, S.; Ochola, E.; Mujinga, M.; Mwim, E. Evaluating Data Privacy Compliance of South African E-Commerce Websites Against POPIA. J. Inf. Syst. Inform. 2024, 6, 2693–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Congress. Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act 15; United States Congress: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

| POPIA Principle | Description |

|---|---|

| Accountability | The responsible party must ensure that all conditions for lawful processing are fulfilled and adhered to throughout the data lifecycle |

| Processing limitation | Information must be processed lawfully, fairly and not excessively, with adherence to minimality and consent requirements |

| Process specification | Personal information must be collected for a specific, explicitly defined and lawful purpose. Data subject must be informed of this purpose. |

| Further processing | Any further processing of the data must be compatible with the original purpose for which it was collected. |

| Information quality | The responsible party must ensure that data is complete, accurate, not misleading and updated where necessary |

| Openness | The data subject must be informed that data is collected. A notification must also be submitted to the Information Regulator, where applicable. |

| Security safeguards | Reasonable technical and organisational measures must be implemented to ensure integrity and confidentiality of personal information. |

| Data subject participation | Data subjects have the right to access, update or correct their personal information held by the responsible party for free of charge. |

| Continent | Country | Act | POPIA Principles | Other Areas | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accountability | Processing Limitations | Purpose Specification | Further Processing Limitation | Information Quality | Openness | Security Safeguards | Data Subject Participation | DPO Required | Breach Notification | Cross-Border Data Transfer Limitation | Electronic Marketing | Online Privacy | Enacted Year | |||

| Europe | UK | GDPR | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 2009 | |

| Spain | LOPD | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 1999 | ||||||||

| Bulgarian | DPA | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 2002 | ||||

| America | US | CCPA | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 2018 | ||||||||

| US | COPPA | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 1998 | ||||

| Canada | PIPEDA | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 2000 | ||||

| Asia | China | PIPL | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 2021 | |||

| South Korea | PIPA | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 2011 | |||||||

| Singapore | PDPA | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 2012 | |||

| Africa | South Africa | POPIA | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 2013 | |

| Kenya | DPA | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 2019 | ||||

| Benin | PPD | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 2009 | |||||

| Burkina Faso | PPD | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 2004 | ||||||||

| Ghana | DPA | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 2012 | |||||||

| Mall | PPD | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 2013 | |||||||

| Mauritius | DPA | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 2004 | |||||||

| Tunisia | DPA | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 2004 | |||||

| Ivory Coast | PPD | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 2013 | |||||||

| Seychelles | DPA | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 2003 | ||||||

| Morocco | PIRPD | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 2009 | ||||||||

| Cape Verde | DPL | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 2001 | ||||||

| Gabon | PPD | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 2011 | ||||||||

| Database | Initial Search Results | Screened Articles | Full Text Assessed | Relevant Articles |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Google scholar | 1970 | 1963 | 1936 | 27 |

| Scopus | 99 | 94 | 80 | 14 |

| Total | 2069 | 2057 | 2016 | 41 |

| Author | Year | Citation | Study Type | Sector Focus | Methodological Approach | Primary Research Focus | Publisher | SJR and H-Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baloyi and Kotzé [25] | 2017 | 17 | Empirical research | Cross-sectoral | Quantitative study (survey) | Organizational readiness for data privacy compliance | 2017 IST-Africa Week Conference (IEEE) | 7 |

| Da Veiga et al. [12] | 2017 | 4 | Qualitative study | Retail industry Medical aid | Case study | Compliance with POPIA and consumer privacy expectations | Emerald Publishing Limited surge | 0.485 |

| Da Veiga et al. [26] | 2018 | 8 | Qualitative study | Insurance industry | Multi-case study; empirical research | A comparison of compliance with data privacy requirements in two countries | University of Portsmouth | 0.271 |

| Da Veiga et al. [13] | 2019 | 15 | Multi-case study methodology | Insurance industry | Multi-case study; empirical research | Comparing the protection and use of online personal information in SA and the UK | Emerald Publishing Limited | 0.485 |

| Da Veiga et al. [27] | 2022 | 0 | Exploratory | e-commerce | Document analysis | Evaluating data privacy compliance of South African e-commerce websites against POPIA | IGI Global | 0.253 |

| Kumalo and Botha [28] | 2024 | 0 | Methodological study | General organizational compliance | Document analysis | POPIA compliance in digital marketplaces: an IGOE framework for pattern language development | SAICSIT | 0.191 |

| Bredenkamp, Kritzinger, and Herselman [29] | 2021 | 0 | Methodological study | General organizational compliance | Document analysis | Evaluating a consumer data protection framework for IS compliance awareness in South Africa | SAICSIT | 0.191 |

| Chimboza and Smith [17] | 2024 | 0 | Qualitative study | General organizational compliance | Semi-structured interviews | How does compliance with the Protection of Personal Information Act (POPI Act) affect organizations in South Africa? | The 10th African Conference on Information Systems and Technology | 8 |

| Mbonye, Subramaniaaand Padayachee [30] | 2021 | 5 | Methodological study | Energy sector (smart grids) | Systematic literature review | POPIA-compliant regulatory framework for smart grids | IEEE | 7 |

| Malepeng Speckman, and Gerber [31] | 2024 | 0 | Qualitative study | Municipal fresh produce markets | Document analysis | Assessment of POPIA compliance in municipal fresh produce market | IEEE | 7 |

| Tsegaye [32] | 2019 | 5 | Scoping review and thematic analysis | Health research | Document analysis | PoPI compliance through access control of electronic health records | ACM | 0.191 |

| Arthur [33] | 2024 | 0 | Qualitative study | Universities | Mono method qualitative | The Protection of Personal Information Act compliance and requirements for higher education institutions: pre-COVID | University of Johannesburg | 0.249 |

| Hertzog et al. [34] | 2023 | 3 | Methodological study | Health research, universities | Framework development | POPIA compliance in research involving children and adolescents | IASSIST Quarterly | 0.165 |

| Botha et al. [35] | 2015a | 14 | Methodological study | General organizational compliance | Document analysis | Evaluation of online resources for Protection of Personal Information Act (POPIA) implementation | ACI | 0.629 |

| Botha et al. [36] | 2015b | 27 | Literature study | Cross-sectoral (small and medium enterprises (SMEs)) | Survey; theoretical analysis | Effects of POPI Act on small and medium enterprises | IEEE | 7 |

| Staunton and Stadler [37] | 2019 | 12 | Theoretical analysis | Health research | Conceptual analysis | Implications of POPIA for biobanks | SAMJ | 0.199 |

| Staunton et al. [38] | 2020 | 34 | Qualitative study | Health research | Case study | POPIA and data protection for health research | Plosone | 0.803 |

| Staunton., Tschigg, and Sherman [7] | 2021 | 34 | Qualitative | Health research | Semi-structured interviews | Stakeholder perspectives on protection of personal health information | Plosone | 0.803 |

| Thaldar and Townsend [10] | 2021 | 20 | Theoretical | Health research | Conceptual analysis | Exempting health research from POPIA consent | Potchefstroom Electronic Law | 0.242 |

| Swales [8] | 2022 | 13 | Methodological study | Health research | Document analysis | The Protection of Personal Information Act 4 of 2013 in the context of health research: Enabler of privacy rights or roadblock? | Potchefstroom Electronic Law | 0.242 |

| Moabalobelo et al., 2023 [14] | 2023 | 3 | Development process; methodological study | General organizational compliance | Experimental research | Development of POPIA Compliance Assessment | IEEE | 7 |

| Netshakhuma [3] | 2020 | 43 | Case study approach | Universities | Interviews and workshop | Assessment of a South African national consultative workshop on the Protection of Personal Information Act (POPIA) | Emerald Publishing Limited | 0.485 |

| Staunton et al. [11] | 2021 | 6 | Theoretical analysis | Health research | Conceptual analysis | Developing a POPIA code of conduct for research | South African Journal of Bioethics and Law | 0.446 |

| Thaldar [39] | 2023 | 2 | Theoretical | Health research | Conceptual | Applicability of POPIA to pseudonymized data | Frontiers | 0.576 |

| Theys [40] | 2021 | 4 | Qualitative study | Organizational compliance | Case study, interviews, surveys | Challenges of implementation of data protection legislation | RSTCONF | 0.165 |

| Bronstein and Nyachowe [41] | 2023 | 1 | Theoretical | Health research | Conceptual analysis | Applicability of POPIA in health research | SAMJ | 0.446 |

| Legodi and Abdullah [42] | 2021 | 0 | Qualitative study | Organizational compliance | Case study and interviews | Assessing the impact of information privacy protection awareness | IEEE | 7 |

| Sekgweleo and Mariri [43] | 2019 | 5 | Qualitative study | Organizational compliance | Case study interviews | Critical analysis of PoPI Act within the organization | IJCSIS | 0.204 |

| Dala and Venter [44] | 2016 | 1 | Empirical research | Organizational compliance | Survey | Understanding level of compliance with POPIA Mapping | ProQuest | 0.239 |

| Kandeh, Botha, and Futche [2] | 2018 | 46 | Qualitative study | Organizational compliance | Semi-structured interviews | Enforcement of POPIA from data management professionals’ perspective | South African Journal of Information Management | 0.446 |

| Katurura and Cilliers [45] | 2016 | 20 | Theoretical analysis | Health research; information technology | Conceptual analysis | Perspective: POPI Act provisions for patient privacy in mobile health record systems | IEEE | 7 |

| Pelteret and Ophoff [46] | 2017 | 6 | Qualitative study | Financial services industry | Case study | Organizational information privacy strategy and POPI Act impact | IEEE | 7 |

| Scharnick, Gerber, and Futcher [47] | 2016 | 3 | Literature review and qualitative content analysis | General organizational compliance (focus on SMMEs) | Literature review; content analysis | Review of data storage protection approaches for POPI compliance | IEEE | 7 |

| Mbonye, Moodley, and Nyika [4] | 2024 | 1 | Qualitative study | Cross-sectoral | Document review | Applicability of POPIA in AI-driven environments | South African Journal of Information Management | 0.446 |

| Buys [15] | 2017 | 37 | Theoretical analysis | Health research | Conceptual analysis | Implications of POPIA for healthcare professionals | SAMJ | 0.446 |

| de Waal [48] | 2022 | 5 | Theoretical analysis | Health research | Conceptual analysis | The Protection of Personal Information Act (POPIA) and the Promotion of Access to Information Act (PAIA) | Current Allergy & Clinical Immunology | 0.692 |

| Raaff et al. [9] | 2022 | 5 | Formal concept analysis | Information technology | Formal Concept Analysis | Aligning South African data and cloud policy with POPI Act | ICCWS | 7 |

| Zenda Vorster and Da Viega [49] | 2020 | 14 | Empirical research | Insurance industry | Experimental | Protection of personal information in data value chains | South African Computer Journal | 0.191 |

| Kaddu and Ssekitto [50] | 2024 | 3 | Methodological study | General organizational compliance, universities, information technology | Systematic review | Data privacy laws and compliance in African countries | AJOL | |

| Hashmi et al. [1] | 2018 | 211 | Methodological study | General organizational context | Systematic Literature review | State of the art in business process compliance | Springer | 0.352 |

| Govender [16] | 2015 | 4 | Methodological study | General organizational context | Theoretical analysis, framework mapping | Mapping security safeguard requirements to international privacy frameworks | ISSA | 7 |

| Summary Insights: POPIA Compliance Research (2025–2024) | |

|---|---|

| Metric | Value |

| Mean Citations | 15.77 |

| Median Citations | 5.0 |

| Standard Deviation (Citations) | 37.71 |

| Mean SJR/H-index | 1.25 |

| Median SJR/H-index | 0.45 |

| Standard Deviation (SJR/H-index) | 2.26 |

| Most common study type | Methodological |

| Most common sector | Health |

| No | Questions |

|---|---|

| QA1 | Does the paper focus on POPIA implementation and compliance within South African organisation? |

| QA2 | Does the abstract indicate the methodology approach? |

| QA3 | Does the study indicate the analytical approach? |

| QA4 | Do the study indicate scholarly work? |

| QA5 | Do the study address implementation and compliance challenges? |

| QA6 | Is the study relevant to POPIA? |

| QA7 | Do the study clearly indicates its objective? |

| Study ID | Author | Year | QA1 | QA2 | QA3 | QA4 | QA5 | QA6 | QA7 | Total Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | [4] | 2017 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 20 |

| S2 | [13] | 2017 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 21 |

| S3 | [14] | 2018 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 20 |

| S4 | [15] | 2019 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 20 |

| S5 | [33] | 2022 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 20 |

| S6 | [7] | 2024 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 17 |

| S7 | [11] | 2021 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 14 |

| S8 | [17] | 2024 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 20 |

| S9 | [38] | 2021 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 19 |

| S10 | [40] | 2023 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 20 |

| S11 | [37] | 2024 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 20 |

| S12 | [41] | 2019 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 17 |

| S13 | [52] | 2019 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 19 |

| S14 | [34] | 2022 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 17 |

| S15 | [2] | 2024 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 21 |

| S16 | [36] | 2023 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 14 |

| S17 | [7] | 2025 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 17 |

| S18 | [6] | 2015 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 21 |

| S19 | [45] | 2019 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 20 |

| S20 | [46] | 2020 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 17 |

| S21 | [47] | 2021 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 21 |

| S22 | [48] | 2021 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 20 |

| S23 | [19] | 2021 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 20 |

| S24 | [20] | 2023 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 20 |

| S25 | [51] | 2021 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 19 |

| S26 | [9] | 2023 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 17 |

| S27 | [35] | 2021 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 17 |

| S28 | [43] | 2019 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 17 |

| S29 | [12] | 2016 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 20 |

| S30 | [30] | 2018 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 21 |

| S31 | [32] | 2016 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 20 |

| S32 | [42] | 2017 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 21 |

| S33 | [44] | 2016 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 20 |

| S34 | [39] | 2024 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 19 |

| S35 | [10] | 2017 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 18 |

| S36 | [22] | 2022 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 16 |

| S37 | [53] | 2022 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 20 |

| S38 | [54] | 2020 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 21 |

| S39 | [37] | 2024 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 13 |

| S40 | [25] | 2018 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 13 |

| S41 | [23] | 2015 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 20 |

| Compliance Area | Key Challenges | Implementation Approaches | Sectoral Variations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness and understanding | Low awareness levels among staff and management | Training programs, awareness campaigns | Higher financial services, lower in Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) |

| Data management | Lack of proper data classification and handling procedures | Implementing data inventory and risk assessment tools | More advanced practices in health research sector |

| Consent management | Challenges in obtaining and managing specific consent | Developing consent frameworks, exploring exemptions | Particularly complex in health research and biobanking |

| Security safeguards | Inadequate technical and organizational measures | Adopting international security standards, regular audits | No mention found |

| Third-party data sharing | Unconsented distribution of personal information | Implementing strict data sharing agreements, audits | More prevalent issues in retail and insurance sectors |

| Direct Marketing practices | Non-compliance with opt-in/opt-out preferences | Developing compliant marketing strategies, consent management systems | Significant challenges in retail and insurance sectors |

| Cross-border data transfers | Ensuring adequate protection in recipient countries | Implementing binding corporate rules, standard contractual clauses | More relevant in multinational corporations and research collaborations |

| Compliance Assessment | Lack of standardized assessment tools | Development of compliance toolkits and frameworks | Varying approaches across sectors, need for sector-specific tools |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sema, G.G.; Owolawi, P.A.; Olugbara, O.O. Protection of Personal Information Act in Practice: A Systematic Synthesis of Research Trends, Sectoral Applications, and Implementation Barriers in South Africa. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8529. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198529

Sema GG, Owolawi PA, Olugbara OO. Protection of Personal Information Act in Practice: A Systematic Synthesis of Research Trends, Sectoral Applications, and Implementation Barriers in South Africa. Sustainability. 2025; 17(19):8529. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198529

Chicago/Turabian StyleSema, Gugu G., Pius A. Owolawi, and Oludayo O. Olugbara. 2025. "Protection of Personal Information Act in Practice: A Systematic Synthesis of Research Trends, Sectoral Applications, and Implementation Barriers in South Africa" Sustainability 17, no. 19: 8529. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198529

APA StyleSema, G. G., Owolawi, P. A., & Olugbara, O. O. (2025). Protection of Personal Information Act in Practice: A Systematic Synthesis of Research Trends, Sectoral Applications, and Implementation Barriers in South Africa. Sustainability, 17(19), 8529. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198529