Heritage Education, Sustainability and Community Resilience: The HISTOESE Project-Based Learning Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

- to analyse how PBL projects in initial educator preparation mobilize local heritage and sustainable practices;

- to identify the core pedagogical principles that underpin these practices;

- to formulate a transfer-ready design (HISTOESE) with explicit implications for community partnerships and tourism resilience.

2. Pedagogical Framework and Literature Review

2.1. Heritage Education and Didactic Approaches

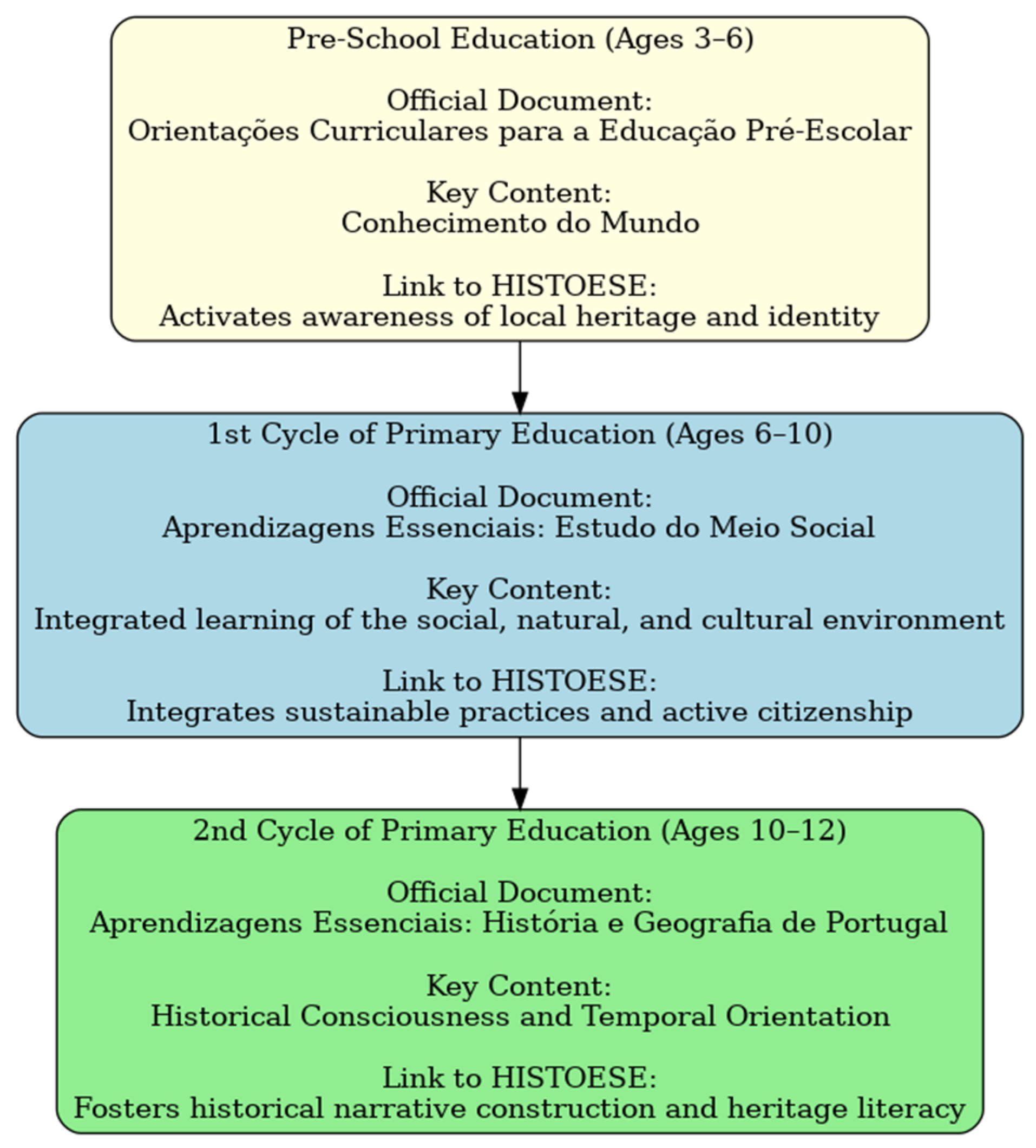

2.2. Curricular Context: Heritage Education in the Portuguese System

- Estudo do Meio Social (Environmental and Social Studies): Taught from the 1st to the 4th grade (ages 6–10), this subject is fundamentally interdisciplinary [40]. It aims to develop a child’s understanding of their social and natural environment by integrating concepts from history, geography, science, and civic education. Its holistic nature aligns directly with the HISTOESE model’s core principle of fostering connections between people, time, and place. In this subject, heritage is not a separate discipline but a transversal theme that allows children to explore their local community, family history, and cultural traditions in an integrated manner [44,45].

- História e Geografia de Portugal: Introduced in the 5th and 6th grades (ages 10–12), this subject marks a transition to more formalized historical and geographical disciplines [41]. It focuses on the chronological study of Portuguese history and the exploration of the country’s diverse landscapes. The pedagogical challenge here—which the HISTOESE approach directly addresses—is to move beyond a mere memorization of facts [46]. Instead, the focus is on developing a deep historical consciousness [19] and an understanding of how the past shapes the present.

2.3. Historical Education and Historical Consciousness

2.4. Social Environmental Studies, Sustainability and Curriculum

2.5. Heritage Education, Didactics and Tourism

2.6. Synthesis and Research Gap

- Lack of Integration: Few studies holistically integrate heritage-based learning, historical consciousness, sustainability and teacher training programmes into a single theoretical foundation or empirical framework.

- Limited Empirical Grounding: There is a scarcity of longitudinal, empirical evidence from early childhood and primary settings, especially in cultural contexts with rich local heritage.

- Contextualization: Research on localization and community participation remains limited, with few studies detailing how families and local heritage actors are systematically involved in co-creating educational programmes.

- Longitudinal Studies: Few studies track the evolution of heritage-based learning practices over multiple years or across different regions.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Context and Participants

- Pre-service teachers (master’s students) who developed and documented classroom projects.

- Cooperating teachers and school mentors who provided supervision and feedback.

3.2. Design and Interpretive Stance

- (1)

- analysis of practical problems;

- (2)

- development and iterative testing of solutions;

- (3)

- reflection and refinement leading to design principles.

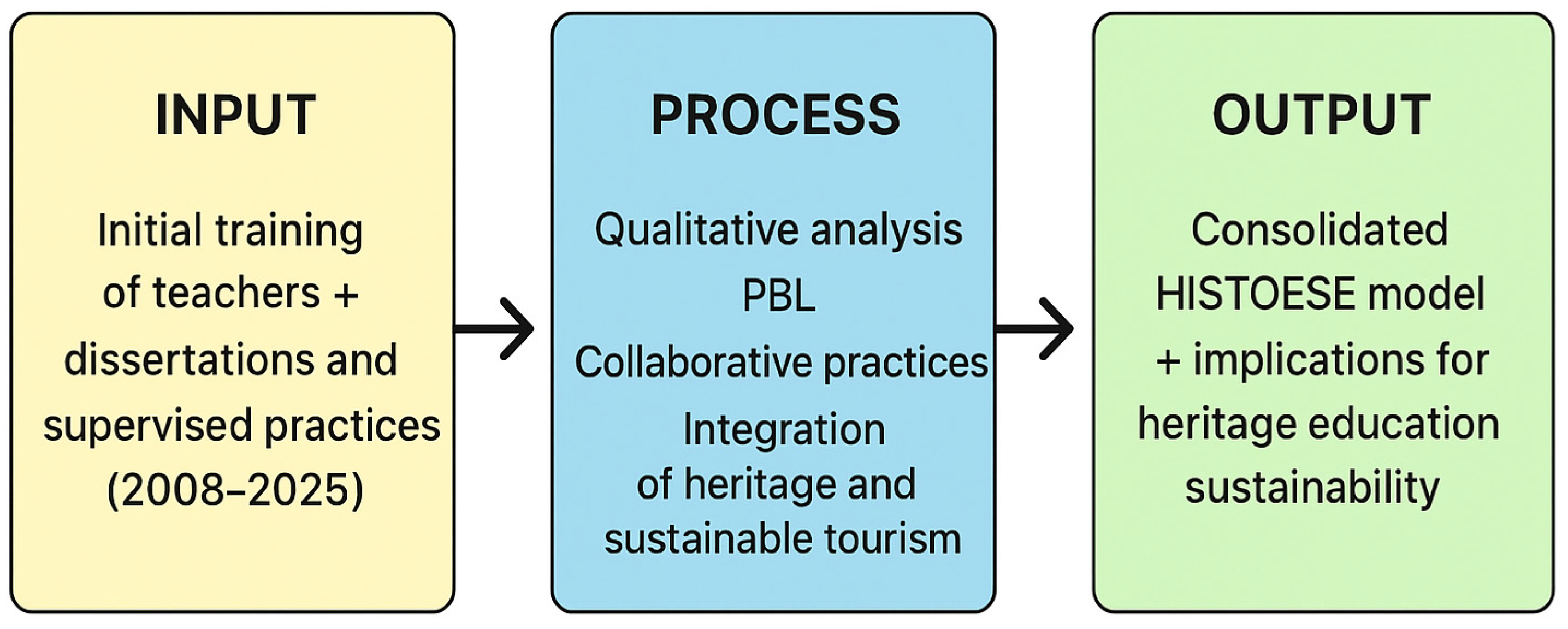

- Cycle 1—Exploratory Synthesis (corpus analysis): systematic review of historical supervised practice reports and dissertations to identify recurring practices, resources and pedagogical forms. Outcomes: initial set of codes and candidate pedagogical principles.

- Cycle 2—Pilot Implementation (course modules): implementation of PBL activities within master’s courses; classroom enactments and community collaborations tested candidate elements. Outcomes: adaptation of learning sequences, inclusion of in situ activities and partnership templates.

- Cycle 3—Consolidation and Reflection: refinement of the model based on repeated implementations and reflective reporting (student narratives, supervisor feedback), producing the consolidated HISTOESE framework.

3.3. Data Corpus

- Lesson plans and didactic units integrating heritage and sustainability.

- Reflective journals and narratives from pre-service teachers.

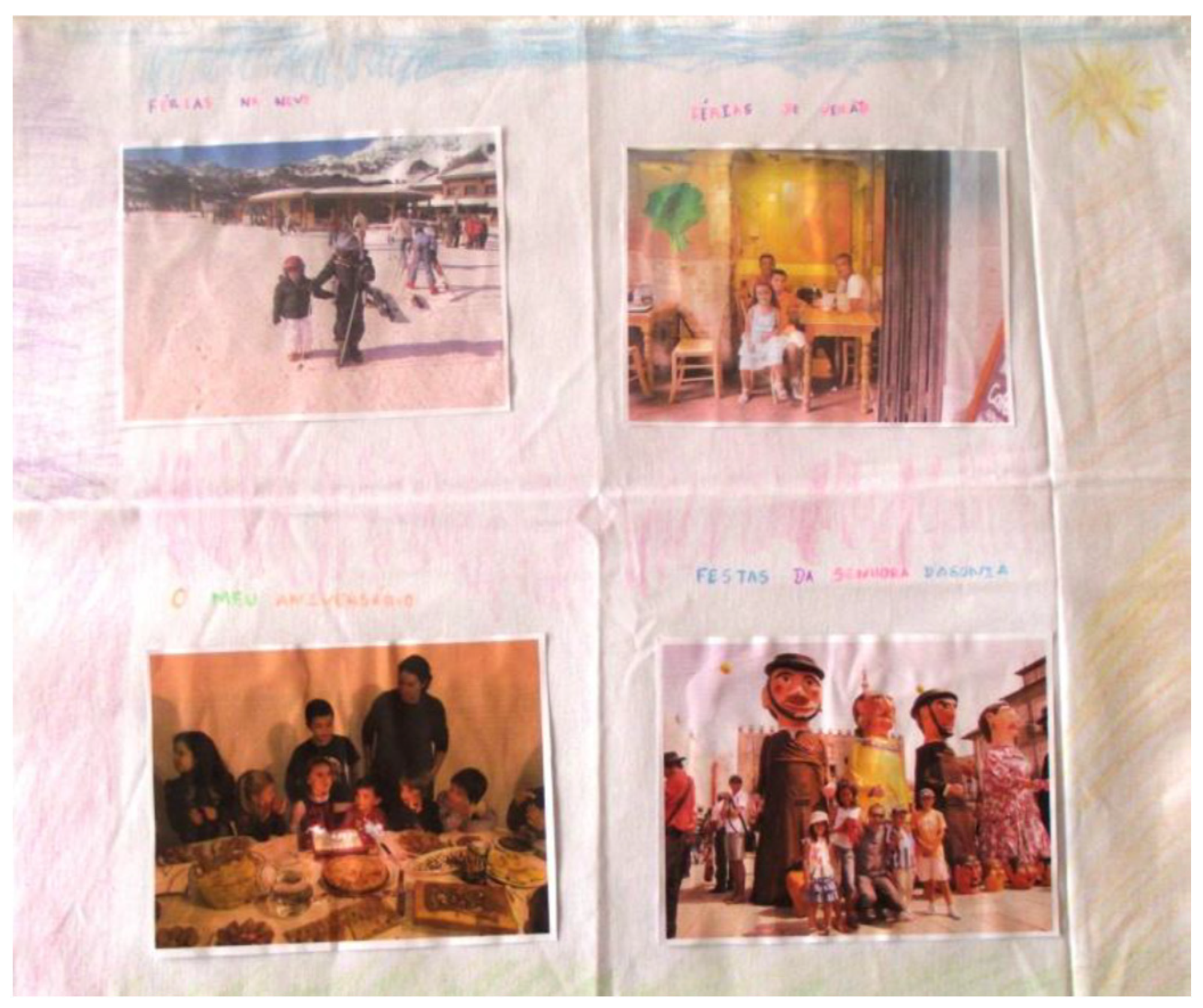

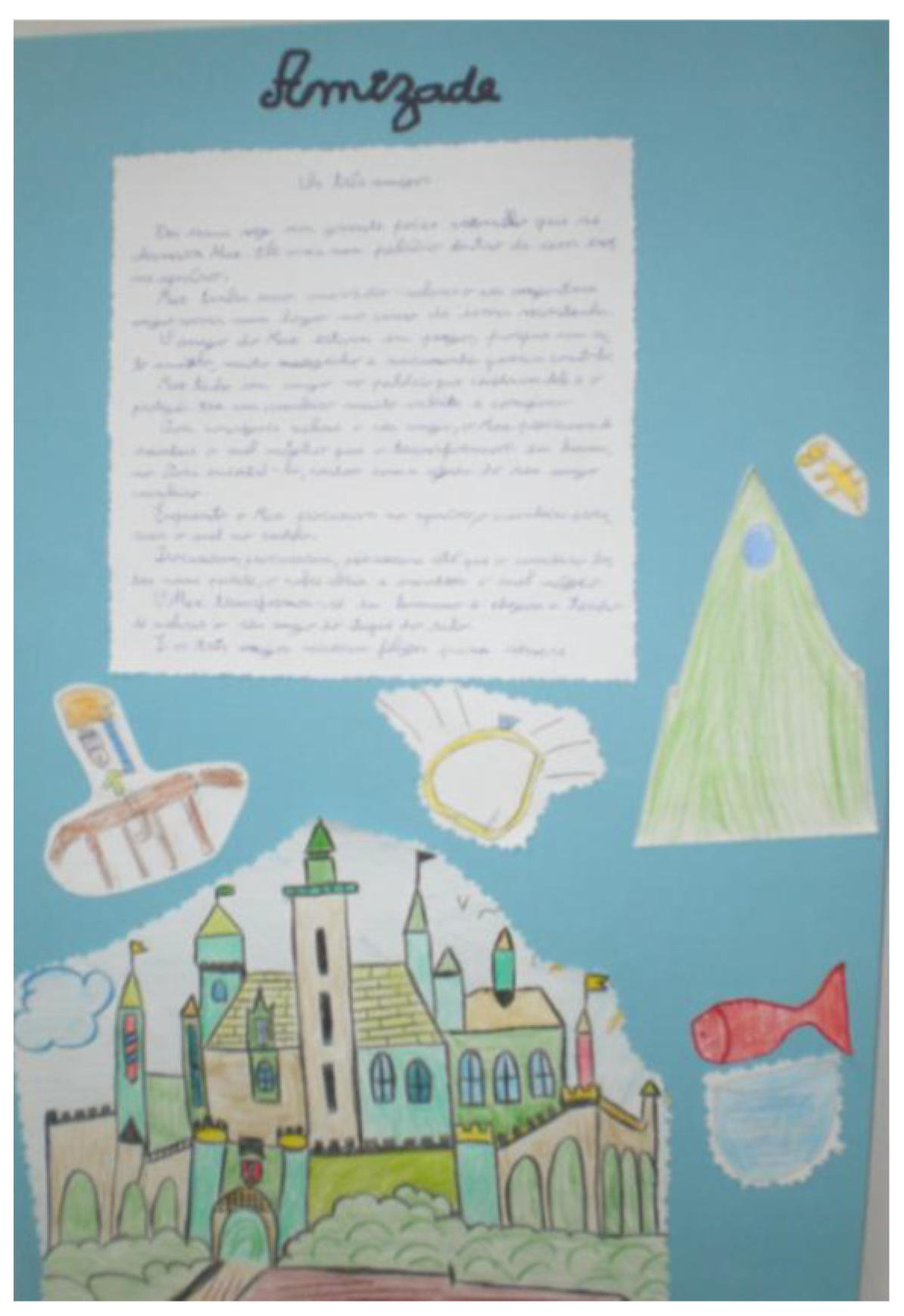

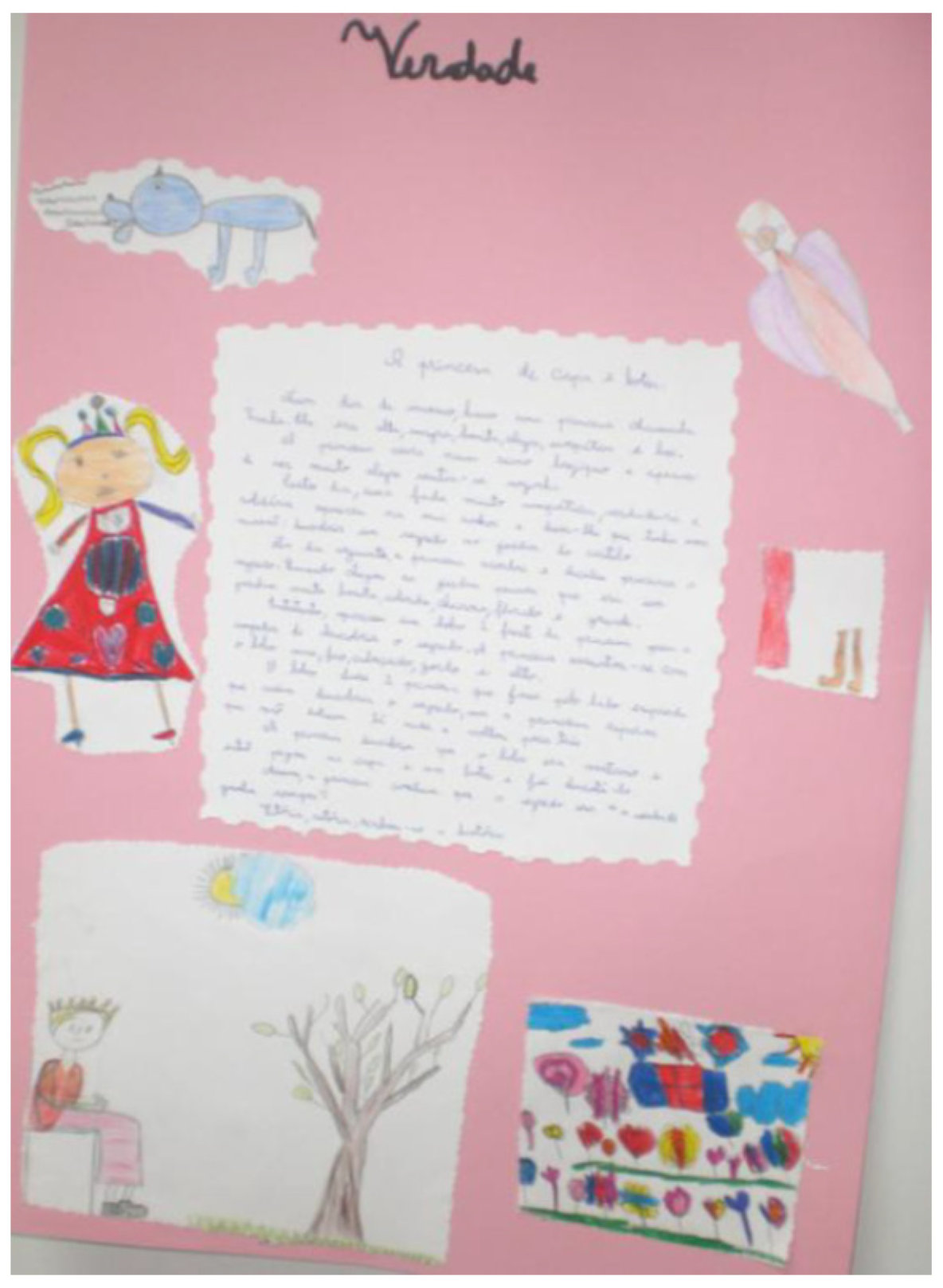

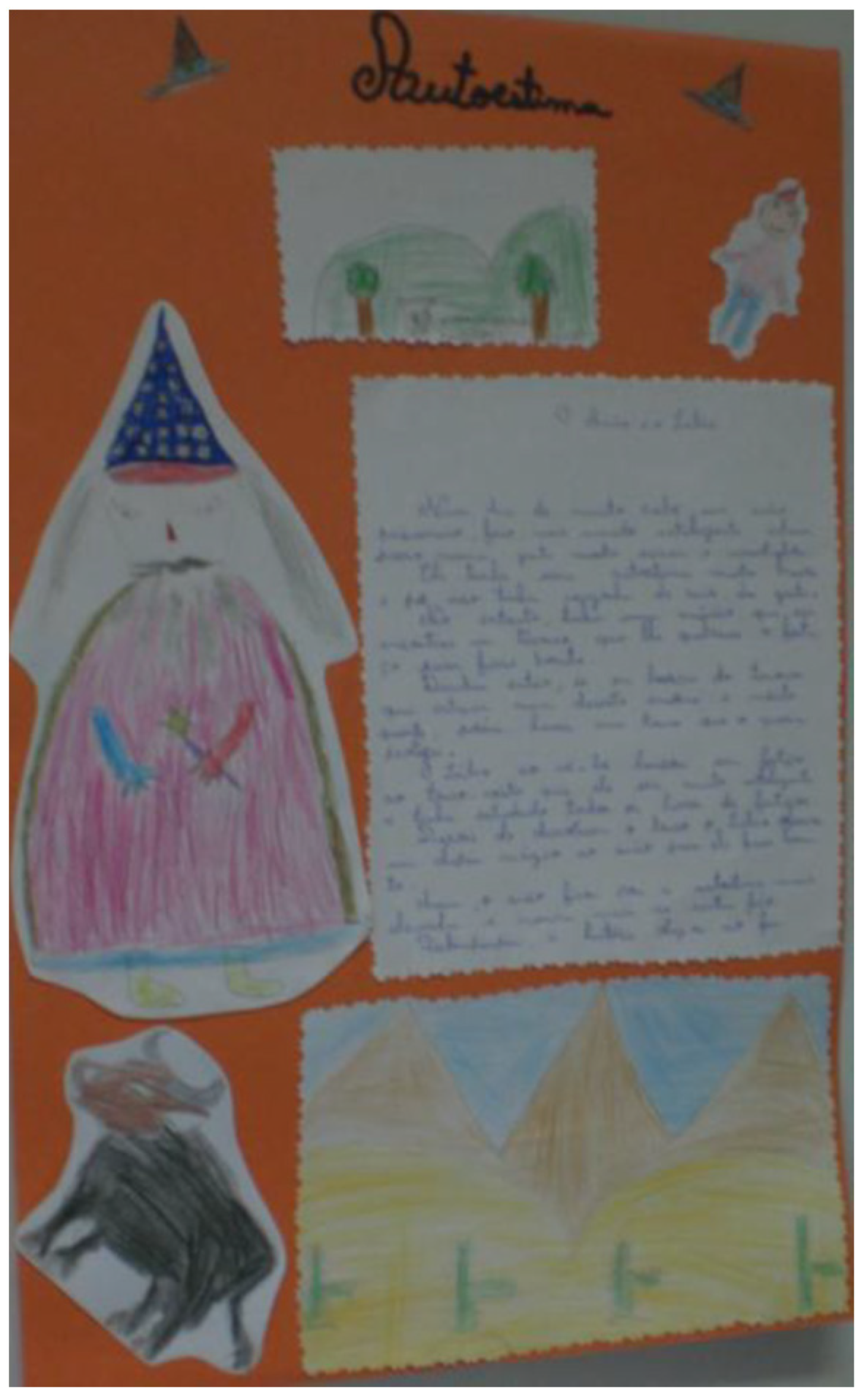

- Children’s outputs (drawings, models, storytelling projects).

- Photographic and digital documentation of field activities.

- Supervisory and evaluative feedback.

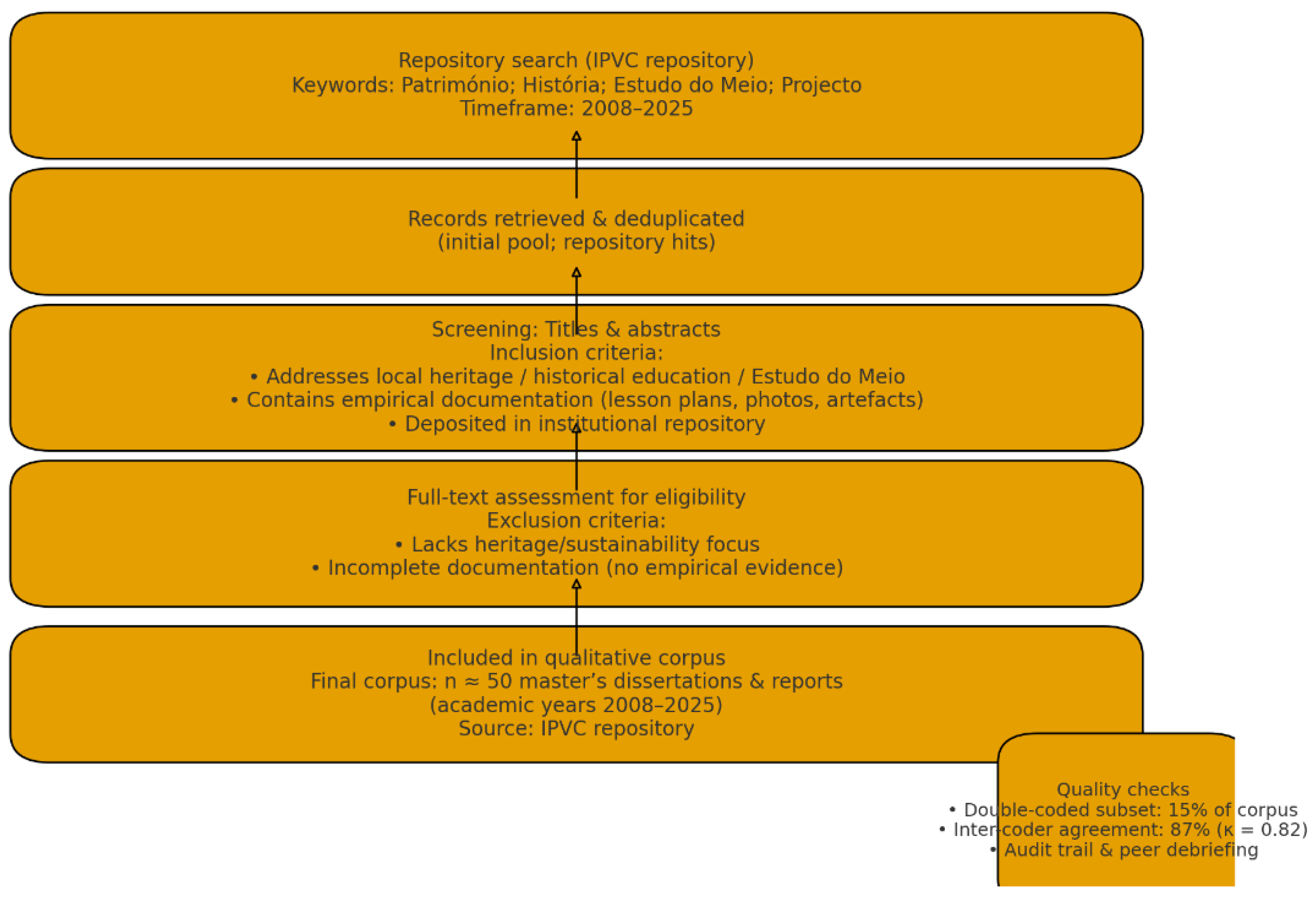

- Unit of analysis: final master’s dissertations and supervised teaching practice reports produced by pre-service teachers in the master’s programmes (Early Childhood and Primary Education) at ESE-IPVC.

- Corpus size: n ≈ 50 documents (covering academic years 2008–2025).

- Inclusion criteria: (a) documents explicitly addressing local heritage, historical education, or Estudo do Meio with implemented classroom/community activities; (b) reports containing empirical documentation (lesson plans, photographic records, student artefacts, reflective journals); (c) deposited in the institutional repository.

- Exclusion criteria: projects lacking a heritage/sustainability focus or with incomplete documentation.

- Selection procedure: a systematic repository search (keywords: “Património”, “História”, “Estudo do Meio”, “Projecto”), followed by screening titles/abstracts and full-text verification. A selection flowchart indicating initial records, screened items, excluded items, and final corpus will be provided as Supplementary Figure S1.

3.4. Analytical Framework

- Codebook: an initial codebook (operational definitions, inclusion/exclusion rules, exemplar quotes) was developed iteratively from the exploratory phase; the finalized codebook is supplied as Supplementary Table S2.

- Coding procedure: coding was predominantly inductive; codes were grouped into higher-order themes through iterative team meetings and memos.

- Intercoder procedure: a subset of documents (~10–20% of the corpus) was independently coded by a second coder to verify consistency; discrepancies were resolved through discussion and consensus, documented in the audit trail. (If desired, quantitative inter-coder metrics such as percentage agreement or Cohen’s κ may be computed and reported here).

- Reflexivity and audit trail: the researcher maintained reflexive memos throughout, and peer debriefing with colleagues was used to challenge interpretations. Triangulation across document types (plans, artefacts, photographs) strengthened confirmability. All analytic steps are documented for traceability and are available in the Supplementary File.

3.5. Ethical Considerations and AI Tool Usage

- Human oversight: all AI outputs were critically reviewed and validated by the researcher.

- Contextual validation: interpretation and meaning-making remained grounded in the researcher’s expertise and the empirical context.

- Transparency of limitations: LLMs cannot capture cultural nuances and were used only to expedite organisation, not to replace interpretive analysis.

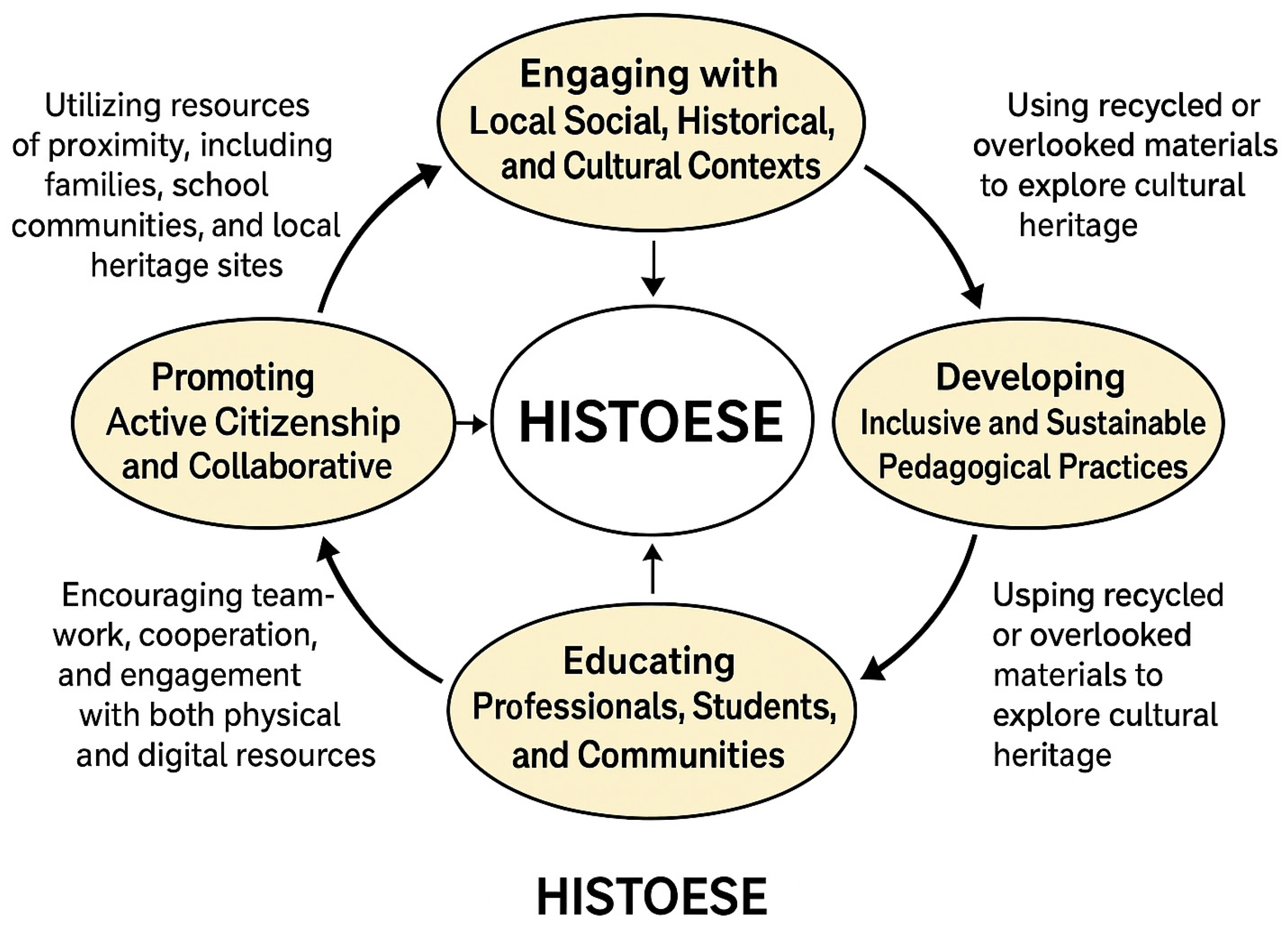

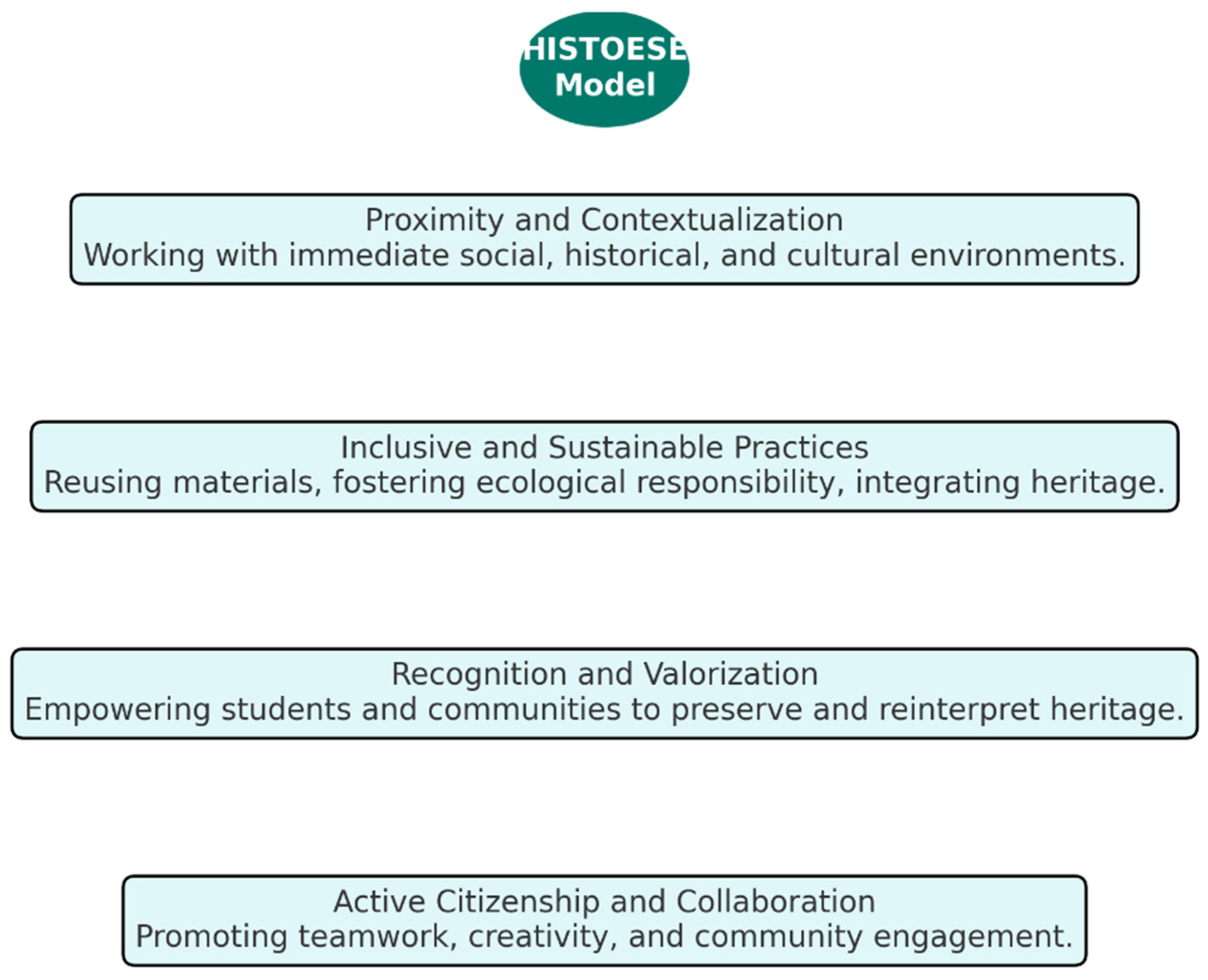

3.6. Emergence of the HISTOESE Design

- Proximity and Contextualization—working with the immediate social, historical, and cultural environment.

- Inclusive and Sustainable Practices—reusing materials, fostering ecological responsibility, and integrating heritage with sustainability.

- Recognition and Valorisation—empowering students and communities to acknowledge, reinterpret, and preserve cultural heritage.

- Active Citizenship and Collaboration—promoting teamwork, creativity, and community participation, both on-site and through digital platforms.

3.7. Visual Representation

4. Discussion and Emergence of the HISTOESE Approach

4.1. From Practice to Theory: A Thematic Synthesis

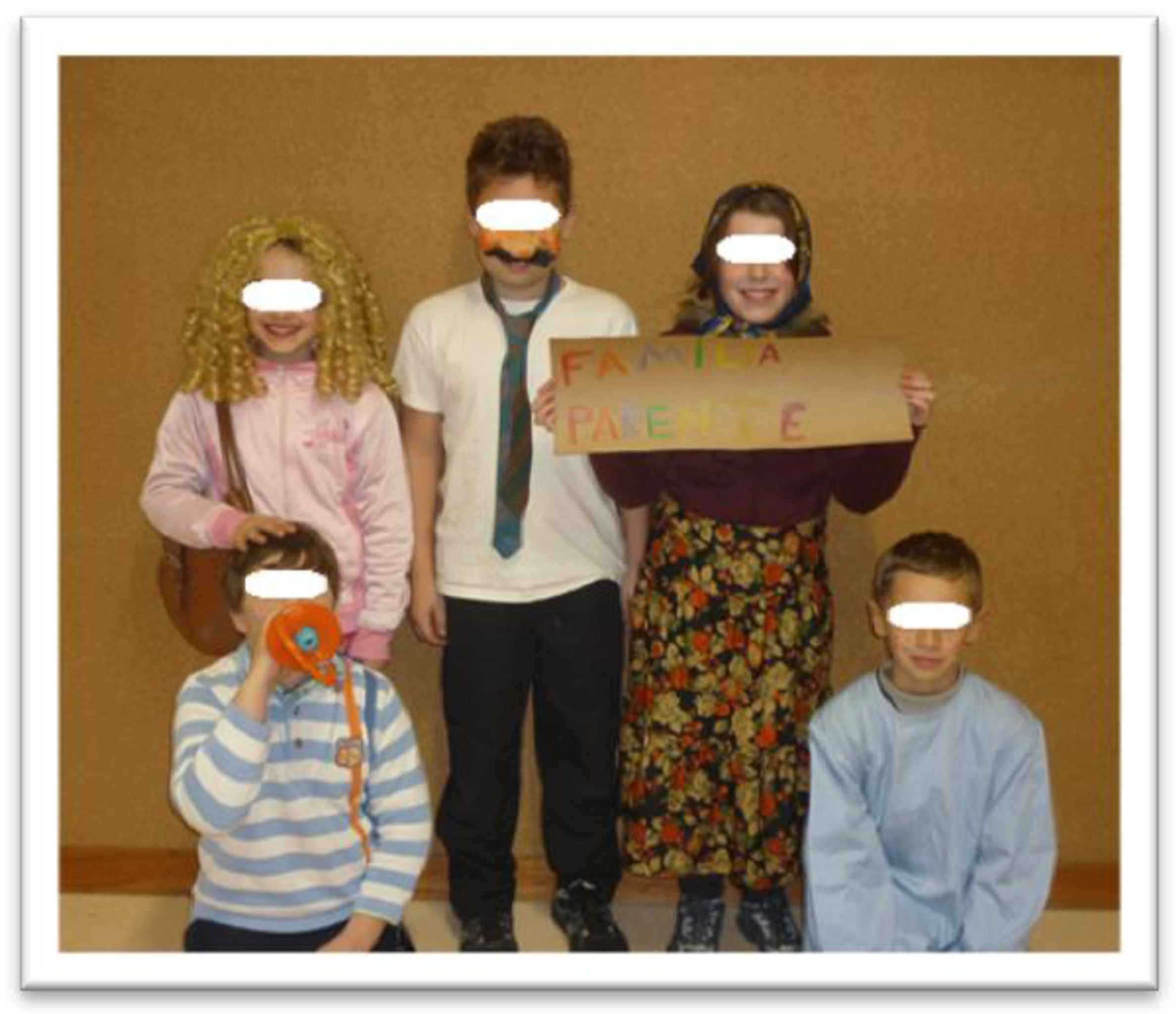

4.1.1. Identity and Heritage

4.1.2. Citizenship and Participation

4.1.3. Inclusion and Diversity

4.1.4. Didactics of History and Geography

4.1.5. Environmental Education and Sustainability

4.2. Broader Implications of the HISTOESE Design

- Between formal, non-formal, and informal learning: The approach uses families, communities, and nearby heritage as resources for situated, lifelong learning.

- Between education and tourism: By fostering professional and community awareness, it positions cultural heritage as a shared responsibility for sustainable and post-COVID recovery, especially in tourism contexts.

- Between cultural preservation and sustainable innovation: It promotes a glocal approach, rooted in the local heritage of northern Portugal and Galicia, yet designed to be transferable and adaptable to other contexts worldwide.

4.3. Community–Tourism Interfaces

4.4. Conclusions: The HISTOESE Contribution

5. Conclusions and Final Considerations

5.1. Answering the Research Questions

- RQ1. How do PBL-based teacher education projects promote Heritage Literacy and Historical Consciousness in early childhood and primary education? The dissertations functioned as a living laboratory for pedagogical innovation. A consistent pattern of contextualised, inquiry-based practices emerged, enabling pre-service teachers to cultivate children’s awareness of local heritage and historical reasoning.

- RQ2. What pedagogical practices and forms of community collaboration recur across the longitudinal corpus and how do they contribute to Cultural Sustainability? Effective practices integrated PBL, fieldwork, creative reuse of materials, and collaboration with families and community partners. These approaches fostered holistic, situated learning and civic participation consistent with the principles of powerful knowledge and inclusive education.

- RQ3. In what ways can school-based heritage projects be traced to community and tourism outputs, and under what conditions do they support local cultural-tourism recovery?

5.2. Final Considerations and Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IPVC | Polytechnic Institute of Viana do Castelo |

| HISTOESE | History Education for Sustainable Environments |

| PASEO | Student Profile by the End of Compulsory Education |

| PBL | Project-based learning |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |

References

- Tilden, F. Interpreting Our Heritage, 4th ed.; The University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Achille, C.; Fiorillo, F. Teaching and Learning of Cultural Heritage: Engaging Education, Professional Training, and Experimental Activities. Heritage 2022, 5, 2565–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Guilarte, Y.; Gusman, I.; Lois González, R.C. Understanding the Significance of Cultural Heritage in Society from Preschool: An Educational Practice with Student Teachers. Heritage 2023, 6, 6172–6188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giardino, M.; Justice, S.; Olsbo, R.; Balzarini, P.; Magagna, A.; Viani, C.; Selvaggio, I.; Kiuttu, M.; Kauhanen, J.; Laukkanen, M.; et al. ERASMUS+ Strategic Partnerships between UNESCO Global Geoparks, Schools, and Research Institutions: A Window of Opportunity for Geoheritage Enhancement and Geoscience Education. Heritage 2022, 5, 677–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, F.; Yasin, N.; Nair, G. Envisioning the Future of Heritage Tourism in the Creative Industries in Dubai: An Exploratory Study of Post COVID-19 Strategies for Sustainable Recovery. Heritage 2023, 6, 4557–4572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernàndez-Cardona, F.X.; Sospedra-Roca, R.; Íñiguez-Gracia, D. Educational Illustration of the Historical City, Education Citizenship, and Sustainable Heritage. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, L.A.; Pinto, H. Educación Histórica con el Patrimonio: Desafiando la Formación de Profesorado. Rev. Electrón. Interuniv. Form. Profr. 2019, 22, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, F.; Costa, A.P.; Sá, M.F. O Papel da Investigação na Prática Pedagógica dos Mestrados em Ensino. In Atas do XII Congresso Internacional Galego-Português de Psicopedagogia; Universidade do Minho: Braga, Portugal, 2013; pp. 2641–2655. ISBN 978-989-8525-22-2. Available online: https://repositorium.sdum.uminho.pt/handle/1822/25492 (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Mtapuri, O.; Daitai, J.; Camilleri, M.A.; Dluzewska, A. Sustainable tourism development: Insights from South Africa and the continent. In Tourism Planning and Destination Marketing, 2nd ed.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2024; pp. 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, A.I.; Marques, G.M. Educação Histórica entre os 3 e os 12 Anos: Desafios para Quem Ensina e para Quem Aprende. Educ. Soc. Cult. 2019, 55, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, G.M. Didactic and Pedagogical Aspects of Tourism Training Programs in Portugal: Conceptual Analysis of Study Plans. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, G.M. Heritage Literacy: Contributions into a Conceptual Framework. Diálogos Com Arte Rev. Arte Cult. Educ. 2020, 10, 150–161. [Google Scholar]

- Barthes, A. What Adaptations of French Elementary Teachers to “Educations for”? Res. Sci. Educ. 2019, 45, 163–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthes, A.; Blanc-Maximin, S. What Are the Developments in the French Schools for Heritage Education? Rev. Sci. Educ. 2017, 43, 85–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, C. Heritage and Participation. In The Palgrave Handbook of Contemporary Heritage Research; Waterton, E., Watson, S., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2015; pp. 346–365. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, M.-P.; Ortiz-Urbano, R. Active learning methodologies in teacher training for cultural sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, A.; Facey, J. Placing History: Territory, Story, Identity—And Historical Consciousness. Teach. Hist. 2004, 116, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, C. El Origen de los Procesos de Patrimonialización: La Efectividad como Punto de Partida. Educ. Artística Rev. Investig. 2014, 5, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rüsen, J. Forming Historical Consciousness: Towards a Humanistic History Didactics. Antíteses 2012, 5, 519–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romera, F.; Le Bigot, E.; Khoo, C. Heritage Education towards Sustainable Development in Tourism: An Inclusive Systematic Literature Review. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2024, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barca, I. Aula Oficina: Do Projeto à Avaliação. In Para uma Educação de Qualidade: Atas da Quarta Jornada de Educação Histórica; CIED: Braga, Portugal, 2004; pp. 131–144. Available online: https://lapeduh.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/para-uma-educac3a7c3a3o-histc3b3rica-de-qualidade.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Chen, Q.; Cheng, J.; Wu, Z. Evolution of the Cultural Trade Network in “the Belt and Road” Region: Implication for Global Cultural Sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchoro-Parrilla, R.; Lavega-Burgués, P.; Damian-Silva, S.; Prat, Q.; Sáez de Ocáriz, U.; Ormo-Ribes, E.; Pic, M. Traditional Games as Cultural Heritage: The Case of Canary Islands (Spain) from an Ethnomotor Perspective. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 586238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domżał, R. Social Responsibility in Educational Projects of the National Maritime Museum in Gdansk. Muzealnictwo 2022, 63, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L. The Uses of Heritage; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Remoaldo, P.; Matos, O.; Freitas, I.; da Silva Lopes, H.; Ribeiro, V.; Gôja, R.; Pereira, M. Good and Not-so-Good Practices in Creative Tourism Networks and Platforms: An International Review. In A Research Agenda for Creative Tourism; Duxbury, N., Richards, G., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; pp. 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontal, O. La educación, un ámbito clave en la gestión del patrimonio cultural. In Patrimonio Cultural y Desarrollo Territorial; Cultural Heritage & Territorial Development; Thomson Reuters Aranzadi: Cizur Menor, Spain, 2016; pp. 107–132. Available online: http://uvadoc.uva.es/handle/10324/24329 (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Lim, M.-K.; Lee, C. A Study on the Heat and Stress Evaluation of Reinforced Concrete through High-Frequency Induction Heating System Using Finite Element Techniques. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontal, O.; Gómez-Redondo, C. Heritage Education and Heritagization Processes: SHEO Methodology for Educational Programs Evaluation. Interchange 2016, 47, 65–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rüsen, J. Os Princípios da Aprendizagem: A Filosofia da História na Didática da História. In Diálogo(s), Epistemologia(s) e Educação Histórica: Um Primeiro Olhar; Alves, L.A., Gago, M., Eds.; CITCEM: Porto, Portugal, 2021; pp. 11–20. Available online: https://ler.letras.up.pt/uploads/ficheiros/18571.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Martínez Gil, T.; Benito, V.L.; Santacanamestre, J. La Educación Patrimonial como Herramienta para la Educación Inclusiva: Definición, Factores y Modelización. Rev. Andamio 2015, 2, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, E.A.; Martín-Cáceres, M.J.; López, J.M.C. Patrimonio, Territorio y Ciudadanía en Educación Infantil: Concepciones del Alumnado. Panta Rei Rev. Digit. Hist. Didáct. Hist. 2024, 18, 101–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Fernández, J.A.; Medina, S.; López, M.J.; García-Morís, R. Perceptions of Heritage among Students of Early Childhood and Primary Education. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Monfort, N. L’ús Didàctic i el Valor Educatiu del Patrimoni Cultural; Doctoral Dissertation, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2007; Available online: https://ddd.uab.cat/record/36572 (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Somoza Medina, X.; Lois González, R.C.; Somoza Medina, M. Walking as a Cultural Act and a Profit for the Landscape: A Case Study in the Iberian Peninsula. GeoJournal 2023, 88, 2171–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Alonso, F.; Ochoa-Cervantes, A.; Guzón-Nestar, J.L. Service-Learning in Higher Education between Spain and Mexico: Towards the SDGs. Alteridad Rev. Educ. 2022, 17, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cainelli, M.R.; de Souza Tomazini, E.C. A Aula-Oficina como Campo Metodológico para a Formação de Professores em História: Um Estudo sobre o PIBID/História/UEL. Hist. Ensino 2017, 23, 11–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, G.M. Educação Histórica nas Primeiras Idades: Quadro Epistemológico e Conceptual. CEM—Cult. Espaço Mem. 2021, 12, 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ministério da Educação, Direção-Geral da Educação. PASEO: Perfil dos Alunos à Saída da Escolaridade Obrigatória; Ministério da Educação, Direção-Geral da Educação: Lisboa, Portugal, 2017. Available online: https://www.dge.mec.pt/perfil-dos-alunos (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Ministério da Educação, Direção-Geral da Educação. Aprendizagens Essenciais: Estudo do Meio, 1–4.° Anos de Escolaridade; Ministério da Educação, Direção-Geral da Educação: Lisboa, Portugal, 2018. Available online: https://www.dge.mec.pt/aprendizagens-essenciais-ensino-basico (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Ministério da Educação, Direção-Geral da Educação. Aprendizagens Essenciais: História e Geografia de Portugal, 5.° e 6.° Anos de Escolaridade; Ministério da Educação, Direção-Geral da Educação: Lisboa, Portugal, 2018. Available online: https://www.dge.mec.pt/aprendizagens-essenciais-ensino-basico (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Ministério da Educação, Direção-Geral da Educação. Orientações Curriculares para a Educação Pré-Escolar; Ministério da Educação, Direção-Geral da Educação: Lisboa, Portugal, 2016. Available online: https://www.dge.mec.pt/orientacoes-curriculares-para-educacao-pre-escolar (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Marques, G.M.; Barroso, A.; Pereira, A.C.; Matos, C.J.; Machado, F.; Pereira, M. Estratégias de Ensino da História e dos Estudos Sociais no 1° Ciclo do Ensino Básico. Hist. Ensino 2013, 19, 195–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, J.A. Estudos do Património: Museus e Educação, 2nd ed.; Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra: Coimbra, Portugal, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mestre, J.S.; Gil, T.M. Patrimonio, Identidad y Educación: Una Reflexión Teórica desde la Historia. Educ. Siglo XXI 2013, 31, 47–60. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, H.; Chapman, A. (Eds.) Constructing History 11–19; Sage: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rüsen, J. Evidence and Meaning: A Theory of Historical Studies; Berghahn Books: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Barca, I. Ideias Chave para a Educação Histórica: Uma Busca de (Inter)Identidades. História Rev. 2012, 17, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barca, I. Literacia e Consciência Histórica. Educ. Rev. 2006, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barca, I. História e Diálogo entre Culturas: Contributos da Teoria de Jörn Rüsen para a Orientação Temporal dos Jovens. Intelligere 2017, 3, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barca, I. Investigar em Educação Histórica em Portugal: Opções Metodológicas. Educ. Rev. 2019, 35, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barca, I. Educação Histórica: Desafios Epistemológicos para o Ensino e a Aprendizagem da História. In Diálogo(s), Epistemologia(s) e Educação Histórica: Um Primeiro Olhar; Alves, L.A., Gago, M., Eds.; CITCEM: Porto, Portugal, 2021; pp. 59–70. Available online: https://repositorio-aberto.up.pt/handle/10216/135510 (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Chapman, A. Research and Practice in History Education in England: A Perspective from London. J. Soc. Stud. Educ. Res. 2017, 6, 13–43. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, A.; Wilschut, A. Joined-Up History: New Directions in History Education Research; Information Age Publishing: Scottsdale, AZ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, A. Knowing History in Schools: Powerful Knowledge and the Powers of Knowledge; UCL Press: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, A. Asses, Archers and Assumptions: Strategies for Improving Thinking Skills in History in Years 9 to 13. Teach. Hist. 2006, 123, 6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Cainelli, M.; Barca, I. A Aprendizagem da História a Partir da Construção de Narrativas sobre o Passado. Educ. Pesqui. 2018, 44, e164920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solé, G. A História nos Manuais Escolares do Ensino Primário em Portugal: Representações Sociais e a Construção de Identidade(s). Hist. Mem. Educ. 2017, 6, 89–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solé, G. Ensino da História em Portugal: O Currículo, Programas, Manuais Escolares e Formação Docente. El Futuro del Pasado 2021, 12, 21–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solé, G. Children’s Understanding of Time: A Study in a Primary History Classroom. Hist. Educ. Res. J. 2019, 16, 158–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, A.D. Elaboración de Trabajos Guiados sobre Patrimonio Cultural: Métodos Mixtos de Trabajo. Eur. Public Soc. Innov. Rev. 2025, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röll, V.; Meyer, C. Young People’s Perceptions of World Cultural Heritage: Suggestions for a Critical and Reflexive World Heritage Education. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. UNESCO World Heritage Convention: World Heritage and Sustainable Development; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2015; Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/sustainabledevelopment/ (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- García-Ceballos, S.; Aso, B.; Navarro-Neri, I.; Pilar, R. La Sostenibilidad del Patrimonio en la Formación de los Futuros Docentes de Educación Primaria: Compromiso y Práctica Futura. Rev. Interuniv. Form. Profr. 2021, 96, 87–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miralles, P.; Gómez, C.; Rodríguez, R. Patrimonio, Competencias Históricas y Metodologías Activas de Aprendizaje: Un Análisis de las Opiniones de los Docentes en Formación en España e Inglaterra. Estud. Pedagógicos 2017, 43, 161–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Guilarte, Y. El Patrimonio Inmaterial y el Paisaje como Recursos Didácticos: Una Investigación Acción a Través del Camino de Santiago. Rev. Investig. Educ. 2022, 20, 204–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia Espinosa, F.; Arias Ferrer, L. El Aprendizaje Basado en Objetos como Estrategia para la Enseñanza de la Historia en Educación Primaria: Un Estudio Cuasi-Experimental. Espiral. Cuad. Profr. 2021, 14, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatipoglu, B.; Ertuna, B.; Sasidharan, V. A Referential Methodology for Education on Sustainable Tourism Development. Sustainability 2014, 6, 5029–5048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, P.J.; Fesenmaier, D.R.; Tribe, J. The Tourism Education Futures Initiative (TEFI): Activating Change in Tourism Education. J. Teach. Travel Tour. 2011, 11, 2–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Fonseca Filho, A. Educação e Turismo: Reflexões para Elaboração de uma Educação Turística. Rev. Bras. Pesqui. Tur. 2007, 1, 5–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, E.C.H.; Azevedo, A.C.; Cadavez, C.; Domingues, S.; Gonçalves, S.F. Turismo, História e Patrimônio: Diálogos entre Brasil e Portugal. Tur. Soc. Territ. 2021, 3, e27375. [Google Scholar]

- Guillén-Peñafiel, R.; Hernández-Carretero, A.M.; Sánchez-Martín, J.M. Heritage Education as a Basis for Sustainable Development: The Case of Trujillo, Monfragüe National Park and Villuercas-Ibores-Jara Geopark (Extremadura, Spain). Land 2022, 11, 1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgousis, E.; Savelidi, M.; Savelides, S.; Holokolos, M.V.; Drinia, H. Teaching Geoheritage Values: Implementation and Thematic Analysis Evaluation of a Synchronous Online Educational Approach. Heritage 2021, 4, 3523–3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anokhin, A.Y.; Kropinova, E.G.; Spiriajevas, E. Developing Geotourism with a Focus on Geoheritage in a Transboundary Region: The Case of the Curonian Spit, a UNESCO Site. Balt. Reg. 2021, 13, 112–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ceballos, S.; Rivero, P.; Molina-Puche, S.; Navarro-Neri, I. Educommunication and Archaeological Heritage in Italy and Spain: An Analysis of Institutions’ Use of Twitter, Sustainability, and Citizen Participation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, M.H. O Patrimônio Cultural no Ensino de História: Entre Teoria e Prática. Front. Rev. História 2019, 21, 10–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barca, I.; Solé, G. Educación Histórica en Portugal: Metas de Aprendizaje en los Primeros Años de Escolaridad. Rev. Electrón. Interuniv. Form. Profr. 2012, 15, 91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Melo, A.D.; Cardozo, P.F. Patrimônio, Turismo Cultural e Educação Patrimonial. Educ. Soc. 2015, 36, 1059–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñafiel, R.G.; Martín, J.M.S.; Carretero, A.H. Evaluation of Heritage Education during Tourism Experiences: The Case of Monfragüe National Park, Villuercas-Ibores-Jara Geopark and Trujillo, Cáceres (Spain). Meta Avaliação 2020, 23, 539–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñafiel, R.G.; Carretero, A.M.H.; Martín, J.M.S. Formación en Educación Patrimonial y Didáctica de los Profesionales Turísticos: Pilares para Contribuir al Desarrollo Sostenible. Lurralde Investig. Espac. 2021, 44, 185–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Sánchez, A.; González-Gómez, D.; Jeong, J.S. Service Learning as an Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) Teaching Strategy: Design, Implementation, and Evaluation in a STEM University Course. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalhido, R.J.; Brilha, J.B.; Pereira, D.I. Designation of Natural Monuments by the Local Administration: The Example of Viana Do Castelo Municipality and its Engagement with Geoconservation (NW Portugal). Geoheritage 2016, 8, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, N.; Pereira, B.; Silva, M.R. From Geoheritage to Geosites at the Oeste Aspiring Geopark (Portugal). Geoheritage 2024, 16, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, M.H.; dos Reis, R.P. Storytelling the Geoheritage of Viana do Castelo (NW Portugal). Geoheritage 2021, 13, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitão, R.B.; Neves, M.L.V.; Sá, C.; Carvalhido, R.J. Educação, Ciência e Património Local: Conceptualização de um Curso de Pós-Graduação para Professores. In Reflexões Sobre Património, Educação e Cultura—I Encontro em Património, Educação e Cultura; Raposo, F., Jorge, F.R., Carvalhinho, M., Eds.; RVJ Editores: Castelo Branco, Portugal, 2020; pp. 43–50. ISBN 978-989-54750-3-2. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10400.11/8490 (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Lin, R.; Chiang, I.Y.; Taru, Y.; Gao, Y.; Kreifeldt, J.G.; Sun, Y.; Wu, J. Education in Cultural Heritage: A Case Study of Redesigning Atayal Weaving Loom. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Wu, F.; Hou, D. Geodiversity, Geotourism, Geoconservation, and Sustainable Development in Longyan Aspiring Geopark (China). Geoheritage 2022, 15, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Halbouni, D.; AlRabayah, O.; Nakath, D.; Rüpke, L. A Vision on a UNESCO Global Geopark at the Southeastern Dead Sea in Jordan—How Natural Hazards May Offer Geotourism Opportunities. Land 2022, 11, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Song, S.; Feng, K. The sustainability cycle of historic houses and cultural memory: Controversy between historic preservation and heritage conservation. Front. Archit. Res. 2022, 11, 1030–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, D.S.; Mota, K.M.; Perinotto, A.R.C. Turismo Pedagógico como Ferramenta de Educação Patrimonial: A Visão dos Professores de História em um Colégio Estadual de Parnaíba (Piauí, Brasil). Tur. Soc. 2012, 5, 82–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venera, S.; Alvarenga, R. Turismo e Ensino de História: Potencialidades e interpretações locais. Rev. Tur. Análise 2010, 21, 421–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, S. Formação de Professores de História: Reflexões sobre um Campo de Pesquisa (1987–2009). Cad. História Educ. 2012, 11, 285–303. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, H.; Silva, S.; Sousa, M.J.; Teixeira, A. Experiencias de Educación Patrimonial con Objetos Arqueológicos en Contexto Formal y no Formal. Ens. Rev. Fac. Educ. Albacete 2019, 34, 83–99. [Google Scholar]

- Prats, L. Antropología y Patrimonio; Ariel: Barcelona, Spain, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, C.Y. A Importância da Educação Patrimonial para o Desenvolvimento do Turismo Cultural. Partes 2006, 30, 1–11. Available online: https://www.ucs.br/site/midia/arquivos/gt5-a-importancia.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Giliberto, F.; Labadi, S. Re-imagining Heritage Tourism in Post-COVID Sub-Saharan Africa: Local Stakeholders’ Perspectives and Future Directions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.; Shattuck, J. Design-Based Research: A Decade of Progress in Education Research? Educ. Res. 2012, 41, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdan, R.C.; Biklen, S.K. Qualitative Research for Education: An Introduction to Theory and Methods, 5th ed.; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, A. Crise: Conceções da Criança e Reflexos na sua Estabilidade Emocional. Relatório Final de Prática de Ensino Supervisionada do Mestrado em Educação Pré-Escolar e Ensino do 1.° Ciclo do Ensino Básico Apresentado na Escola Superior de Educação do Instituto Politécnico de Viana do Castelo. 2013. Available online: http://repositorio.ipvc.pt/handle/20.500.11960/4125 (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenAI. ChatGPT [Large Language Model]; OpenAI: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2025; Available online: https://chat.openai.com (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Halder, S.; Sarda, R. Promoting Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) Tourism: Strategy for Socioeconomic Development of Snake Charmers (India) through Geoeducation, Geotourism and Geoconservation. Int. J. Geoheritage Parks 2021, 9, 212–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, T.; Ainscow, M. The Index for Inclusion: A Guide to School Development for Inclusive Education; CSIE: Bristol, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo, D. A Constituição da Família em Crianças de Idade Pré-Escolar: Estudo de Caso. Relatório Final de Prática de Ensino Supervisionada do Mestrado em Educação Pré-Escolar e Ensino do 1.° Ciclo do Ensino Básico Apresentado na Escola Superior de Educação do Instituto Politécnico de Viana do Castelo. 2012. Available online: http://repositorio.ipvc.pt/handle/20.500.11960/4130 (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Barton, K.C.; Levstik, L.S. Teaching History for the Common Good; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Remoaldo, P.; Matos, O.; Gôja, R.; Alves, J.; Duxbury, N. Management Practices in Creative Tourism: Narratives by Managers from International Institutions to a More Sustainable Form of Tourism. Geosciences 2020, 10, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, E.; Lopes, E.R.; Simões, J.; Soares, J.; Constantino Figueira, M. View of Tourism on the ecopistas as a factor in the preservation of railway cultural heritage. J. Tour. Herit. Res. 2024, 7, 106–114. [Google Scholar]

- Coelho, C. À Descoberta da Identidade Cultural Local: Estudo Numa Turma do 3° Ano de Escolaridade. Relatório Final de Prática de Ensino Supervisionada do Mestrado em Educação Pré-escolar e Ensino do 1.° Ciclo do Ensino Básico Apresentado na Escola Superior de Educação do Instituto Politécnico de Viana do Castelo. 2018. Available online: http://repositorio.ipvc.pt/handle/20.500.11960/1989 (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- UNESCO. Shaping the Future We Want: UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (2005–2014) Final Report; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2014; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000230171 (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Beatriz, S. A Identidade na Palma do Pé e na Ponta do Dedo: Estudo Com Crianças de Idade Pré-Escolar. Relatório Final de Prática de Ensino Supervisionada do Mestrado em Educação Pré-escolar e Ensino do 1.° Ciclo do Ensino Básico Apresentado na Escola Superior de Educação do Instituto Politécnico de Viana do Castelo. 2025. Available online: http://repositorio.ipvc.pt/handle/20.500.11960/4360 (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Araneo, P. Re-imagining Cultural Heritage Archetypes towards Sustainable Futures. J. Futures Stud. 2017, 21, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, L.A.; Marques, G.M.; Pinto, H. O Glocal no Ensino da História: Desafios e Reflexões. In Educación, Historia y Memoria: Espacios y Agentes Educativos (Siglos XX–XXI); Rico Gómez, M.L., Ponce Gea, A.I., Zapata, Y.G., Eds.; Octaedro: Barcelona, Spain, 2023; pp. 85–102. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/libro?codigo=980700 (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Richards, G. Designing creative places: The role of creative tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 85, 102922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seraphin, H.; Kennell, J.; Mandic, A.; Smith, S.; Kozak, M. Language Diversity and Literature Reviews in Tourism Research. Tour. Cult. Commun. 2023, 23, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Level 1 Macro-Themes | Level 2 Subcodes/Indicators |

|---|---|

| A. Local Context & Resources (families, community, local monuments, intangible heritage) | A1: Use of intergenerational knowledge (grandparents, artisans) A2: Field visits and in situ learning (museums, monuments, landscape walks) |

| B. Inclusive & Sustainable Practices (reuse/upcycling of materials, low-cost resources, intentional design) | B1: Use of recycled/waste materials in teaching activities B2: Activities explicitly framed as “sustainable” or ESD |

| C. Professional & Community Education (training sequences, workshops, parental involvement) | C1: Training activities for teachers (micro-teachings, seminars) C2: Collaboration with external actors (museum educators, tourism agents) |

| D. Active Citizenship & Collaboration (teamwork, community projects, civic actions) | D1: Student leadership, community exhibitions, local festivals involvement |

| E. Historical Literacy & Temporal Orientation (use of narratives, temporal sequencing, local history, provenance) | E1: Narrative construction (stories, local legends, chronological exercises) E2: Tools for temporal orientation (timelines, life histories, from my time to our time) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marques, G.M. Heritage Education, Sustainability and Community Resilience: The HISTOESE Project-Based Learning Model. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9891. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219891

Marques GM. Heritage Education, Sustainability and Community Resilience: The HISTOESE Project-Based Learning Model. Sustainability. 2025; 17(21):9891. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219891

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarques, Gonçalo Maia. 2025. "Heritage Education, Sustainability and Community Resilience: The HISTOESE Project-Based Learning Model" Sustainability 17, no. 21: 9891. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219891

APA StyleMarques, G. M. (2025). Heritage Education, Sustainability and Community Resilience: The HISTOESE Project-Based Learning Model. Sustainability, 17(21), 9891. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219891