1. Introduction

Environmental sustainability and resilience have become urgent priorities in contemporary urban planning, particularly as cities increasingly face the disruptive impacts of climate change, extreme weather events, and global health crises. These challenges represent not only economic and infrastructural threats but also profound risks to human well-being. This has generated a growing imperative to rethink how urban systems are designed, governed, and maintained. Urban design has emerged as a crucial discipline for addressing such complexity, shaping urban transformations that are ecologically sustainable, liveable, socially inclusive, and adaptable to future uncertainties. The integration of green infrastructure, flexible public spaces, and art now constitutes a cornerstone of strategies aimed at enhancing the liveability and resilience of increasingly dense and vulnerable urban areas [

1].

Within this framework, the public spaces of university campuses are assuming a progressively more significant role. No longer isolated zones devoted exclusively to academia, campuses today function as dynamic urban ecosystems—places where diverse populations gather for education, socialization, work, leisure, and cultural exchange. Their spatial, social, and environmental functions are increasingly aligned with urban priorities, positioning them as key sites for advancing climate adaptation, community building, and sustainable infrastructures [

2].

Historically, however, university campuses were conceived as insular environments, focused solely on academic activities and characterized by minimal interaction with the surrounding city. In Europe, for example, medieval universities often adopted cloister-like layouts that emphasized separation from everyday urban life: models such as Oxford and Cambridge epitomized this approach, privileging intellectual isolation [

3,

4]. By contrast, in recent decades, the role of campuses has profoundly evolved [

5,

6,

7,

8]: increasingly integrated into the urban fabric, they reflect broader social transformations associated with urbanization, sustainability, and the opening of higher education to public and social functions [

9,

10]. Today, universities are recognized as key actors in urban contexts, and their public spaces—green areas, plazas, pedestrian networks, and courtyards—are designed not only to serve academic needs but also to foster social interaction, community engagement, and environmental sustainability [

11,

12,

13,

14]. The central challenge lies in balancing the traditional academic mission with the growing role of campuses as social and cultural hubs that actively contribute to urban life. Their public spaces operate as multifunctional settings for informal learning, relaxation, and socialization for students and faculty, while simultaneously serving as open resources for city residents, offering cultural, recreational, and social opportunities [

15,

16,

17]. Building on these premises, the present study—conducted within the framework of two research projects both funded by Sapienza Università di Roma—LOVE Sapienza: Livable, enjOyable and attractiVE spaces for the community, under the Author’s responsibility, and University and Urban Regeneration: Redesigning Neglected Spaces and Routes with Sapienza as a Driver (NARRATES), of which the Author is Responsible for the Architectural and Urban Regeneration Line of Research—seeks to identify the key factors that enhance the liveability of campus public spaces and to propose a dedicated methodology, supported by the case study of the University of British Columbia (UBC) in Vancouver.

The aims of LOVE Sapienza include analyzing international best practices of public spaces in universities and campuses, examining Sapienza’s sites, and proposing guidelines for the enhancement and/or design of open public spaces in Sapienza’s facilities, with attention to urban liveability, health, and flexibility. The aims of NARRATES include regenerating underused public spaces in Rome through a sustainable network for non-motorized and collective mobility connecting Sapienza University with key urban hubs and promoting new “narratives” of sustainable places and behaviors that strengthen the university–city relationship.

The original methodology—which was partially used in the aforementioned research projects—developed integrated spatial analyses, field observations, and alignment with the principles of the Charter for Resilient and Liveable Public Spaces, elaborated from the case studies.

The Vancouver campus of UBC represents a particularly significant example of this evolution. Situated within an ecologically sensitive context, it has evolved into a multifunctional environment where sustainability, climate resilience, community, and artistic expression are deeply interwoven. Through biophilic design, inclusive placemaking, and long-term climate planning, the campus not only mitigates ecological risks but also cultivates a vibrant social and cultural community. Its trajectory illustrates how post-secondary institutions can guide urban transformation by promoting public health, civic participation, and environmental stewardship.

Resilience constitutes a central theme in UBC’s development, as the university addresses growing risks such as wildfires, heatwaves, and heavy rainfall through its Resilience Strategy. Notable initiatives include the establishment of “Resilience Hubs”—multifunctional spaces that provide support during emergencies (e.g., cooling centers or distribution hubs for essential goods) while also serving as everyday meeting places designed to ensure accessibility, energy efficiency, and social inclusion. From an environmental standpoint, UBC positions itself as a living laboratory: its Climate Action Plan aims for carbon neutrality by the mid-century through district energy systems, advanced building standards (LEED Gold and beyond), integrated water management, resilient landscapes, and zero-waste infrastructures.

Community engagement is embedded in the Engagement Charter, which sets out principles of transparency and inclusion, involving students, staff, Indigenous communities such as the Musqueam, and neighboring municipalities.

Indeed, UBC’s Indigenous Strategic Plan (ISP) embeds reconciliation within all aspects of campus life, guiding actions that honour Indigenous rights, knowledge, and presence. A key focus—“Enriching our spaces” (Goal 5)—promotes the integration of Indigenous art, design principles, and cultural narratives into public spaces, ensuring that the campus reflects Indigenous heritage and fosters inclusivity. Through collaboration with the Musqueam and other Indigenous Nations, UBC’s open areas, pathways, and artworks become sites of dialogue, remembrance, and respect. These interventions transform the campus into both a learning environment and a landscape of reconciliation, where spatial design and cultural expression advance intercultural understanding and shared stewardship [

18].

The campus’s social infrastructures are conceived as fundamental to well-being: open spaces, greenways, and pedestrian paths encourage social interaction and physical activity; multimodal transport systems reduce emissions; childcare facilities, residences, and recreational centers ensure a balanced and accessible environment.

Finally, the arts play an essential role in UBC’s cultural landscape. Public art—with particular attention to Indigenous expression—is integrated into the built environment to stimulate dialogue and cultural memory. Galleries, performance venues, and installations serve not only the university community but the wider region, reinforcing the campus’s role as a cultural hub (University of British [

18,

19,

20]. This case demonstrates how contemporary campuses, by reconfiguring their role within cities, can reconcile academic, social, and ecological objectives. Their public spaces, increasingly crucial, shape the liveability and resilience not only of university communities but also of the cities that host them. The paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 discusses the main components of a resilient and liveable campus;

Section 3 illustrates the methodology for analyzing and designing campus public spaces;

Section 4 presents the case study;

Section 5 offers the observations; and finally,

Section 6 concludes the study.

2. Universities and Campus Public Spaces: Resilience and Liveability Factors

The design of public spaces within university campuses must respond to the complex and evolving needs of a heterogeneous user base, comprising students, faculty, staff, and residents. In high-density urban environments, where land availability is often constrained, universities frequently face spatial competition from other land uses [

21,

22,

23].

As a result, the allocation of land for public open space is limited, necessitating design strategies that maximize spatial efficiency and multifunctionality within compact footprints. The need to reconcile diverse expectations—ranging from students seeking environments conducive to study and socialization, to residents utilizing campus areas for leisure and recreation—further complicates spatial planning. Addressing these competing demands requires a carefully calibrated approach that integrates resilience, adaptability and flexibility into spatial design [

24].

In addition to programmatic versatility, public space design must prioritize core principles of safety, comfort, and accessibility. The provision of well-lit and clearly legible circulation paths is essential to ensure perceived and actual safety, particularly during non-daylight hours. Furthermore, incorporating adequate seating, shaded zones, and protection from adverse weather conditions contributes to prolonged and equitable use of outdoor spaces. Crucially, accessibility must be approached through an inclusive lens, ensuring universal access for individuals with disabilities. When successfully implemented, these strategies foster not only usability but also broader outcomes such as psychological well-being, social connectivity, and a sense of belonging within the campus community.

2.1. Resilience

The concept of resilience, together with that of adaptation, describes the capacity of a system to absorb shocks, reorganize, and maintain its core functions without losing identity or purpose. Originating in the field of ecology with Holling’s seminal studies (1973) and later extended across a wide range of disciplines—from spatial planning to psychology, sociology, and economics—it has become a transversal category, useful for interpreting the complexity of contemporary societies and their vulnerabilities. Within this research, resilience is operationally defined as the measurable capacity of the campus environment to prevent, withstand, and recover from environmental, infrastructural, and social disruptions through integrated spatial, technological, and community-based strategies. Resilience does not merely denote a passive reaction to crises; rather, it is understood as a dynamic process involving prevention, adaptation, and transformation [

25].

In the context of university campuses, resilience acquires a distinctive relevance, as these environments operate as “miniature cities” characterized by heterogeneous populations and a concentration of educational, social, cultural, and residential functions. The COVID-19 pandemic represented another major test of resilience: campuses that had already integrated outdoor learning environments—such as the University of British Columbia in Vancouver—were able to cope more effectively with the disruption, experiencing only a brief interruption of in-person teaching [

19]. University public spaces are not simply are as of transit, but multifunctional platforms that support community life and foster social cohesion. Squares, green corridors, libraries, courtyards, and communal areas function as social infrastructures that reduce isolation and strengthen bonds among individuals and groups, contributing to the construction of belonging and collective identity [

26]. At the same time, these spaces play a crucial environmental role by mitigating the effects of climate change through nature-based and integrated solutions such as sustainable urban drainage, vegetative shading, permeable surfaces, and biodiversity enhancement [

27]. In this sense, environmental and social resilience are intertwined, producing places capable of accommodating everyday needs while serving as critical infrastructures during times of crisis.

The application of resilience to university spaces is closely linked to the notion of preventive resilience, which presupposes strategic investments, long-term planning, and inclusive governance [

28,

29]. This approach requires not only the identification of potential vulnerabilities, but also particular attention to groups most at risk during crises. On campuses, these may include international students, individuals living in collective residences, persons with disabilities, or those in precarious economic conditions. Social resilience thus translates into universal accessibility, equitable distribution of resources, attention to mental health, and enhanced perceived safety [

30]. Resilient spaces are inherently inclusive: they accommodate cultural and social diversity, promote dialogue and participation, and strengthen networks of mutual support.

Mobility is another key dimension. Reducing automobile dependency forms an integral part of resilience: campuses that prioritize walkability, cycling, and public transport not only deliver environmental benefits but also provide safer and more continuous flows under crisis conditions. Public spaces thereby become connective corridors that integrate multiple modes of mobility and guarantee legible, safe, and redundant routes, avoiding single points of vulnerability [

31]. In recent years, increasing attention has been paid to designing spaces that serve everyday academic, social, and cultural functions but can rapidly transform into shelters and support centres during emergencies. Such spaces can provide protection against extreme weather events, distribute food and water, and ensure energy and information connectivity in the event of service disruptions. Within university campuses, libraries, student centres, and gyms can perform these dual roles, reinforcing the conception of public space as critical infrastructure with both ordinary and extraordinary functions.

Resilience in public space also encompasses cultural and symbolic dimensions. Access to nature and high-quality landscapes directly influence psychological well-being, reducing stress while supporting concentration and creativity [

32]. Tree-lined pathways, community gardens, and teaching orchards create regenerative environments that strengthen a sense of community. In parallel, public art, collective events, and cultural celebrations consolidate the identity of the campus as a locus of shared memory and social innovation.

2.2. Well-Being

Liveability is operationally defined here as the set of environmental and social conditions that support human well-being, comfort, and inclusivity within the campus context. Main factors include thermal comfort, perceived safety, accessibility score, and health-related quality of life. This concept has gained increasing relevance in urban planning as cities seek to create environments that enhance human well-being. Within university campuses, liveability [

33] is crucial not only for students, faculty, and staff who spend significant time in these spaces, but also for the broader urban communities that interact with campus facilities [

34]. Universities are no longer solely educational institutions; they now function as social, cultural, and economic actors within cities, shaping the urban landscape and fostering community well-being.

The contribution of public spaces to individual physical and psychological health is well documented in environmental and urban studies. In the campus context, one of the most significant determinants of liveability is the integration of green infrastructure. Numerous studies highlight the benefits of natural environments—parks, gardens, and vegetated open spaces—for mental health and psychosocial well-being. Exposure to such settings is associated with reduced stress, improved mood, and strengthened social cohesion, particularly through informal social interactions [

1]. Among these spatial typologies, the concept of “healing gardens” has gained prominence. Incorporating trees, flowering plants, and water features, they offer restorative experiences that provide refuge from academic pressures. Evidence shows that such spaces support cognitive restoration and emotional resilience among students and staff [

22,

35]. More broadly, the presence of natural settings contributes to calmness and focus, both positively correlated with academic performance and psychological health. Physical activity represents another essential dimension of liveability, closely tied to both mental and physical health. Walking paths, sports fields, outdoor fitness installations, and open activity zones encourage daily movement and exercise, improving cardiovascular health, reducing risks of chronic illness, and enhancing emotional stability [

36,

37]. These spaces thus function not only as recreational amenities but as critical components of public health infrastructure [

38].

Green and open spaces also provide micro-breaks that counteract stress-induced fatigue in demanding academic environments. This aligns with biophilic theory, which posits an innate human affinity with nature and explains the calming effects of natural settings. Empirical evidence links time spent in nature to reduced cortisol levels and improved emotional well-being.

Beyond individual outcomes, campus public spaces play a social role, fostering inclusive and cohesive communities. They provide platforms for casual, unstructured encounters that promote interpersonal connections and reduce isolation—an issue frequently observed in academic contexts [

35]. Plazas, seating areas, and outdoor cafés enable interaction across disciplinary, cultural, and generational boundaries, enriching the social fabric of the university. In doing so, they contribute both to individual well-being and to the cultivation of a supportive, diverse campus culture.

2.3. Connectivity

Connectivity is a factor that is necessary to open the campus to the city and create a social sustainability.

Historically, university campuses were conceived as insular environments, reinforcing the notion of academia as a world detached from everyday urban life. Contemporary urban dynamics—marked by population growth, densification, and shifting socio-economic priorities—have transformed this paradigm. Today, the boundaries between campus and city are increasingly porous, requiring a reconceptualization of the university’s role within the broader urban ecosystem.

A key driver of this shift is the recognition of universities as catalysts for urban regeneration, particularly in areas lacking accessible public infrastructure or facing socio-economic challenges [

37]. Many institutions have therefore embraced the “open campus” model, reimagining their estates as multifunctional, publicly accessible environments that provide value beyond the academic community. By integrating green infrastructure, cultural amenities, and socially oriented services, these campuses actively contribute to urban liveability [

38,

39].

This model is especially relevant in cities with limited public space. Universities often hold large land assets, and by opening portions of their estates for public use, they help address urban deficits in recreation, ecology, and social infrastructure. Moreover, through the development of connective elements—pedestrian corridors, bicycle lanes, bridges, and transitional nodes—campuses foster physical and symbolic integration with their urban surroundings.

Designing for connectivity requires prioritizing inclusivity. Universal design principles must be applied to pedestrian paths, seating, and gathering spaces, ensuring accessibility for people of all ages and abilities. Locating green spaces near academic buildings, residences, and public transport nodes further enhances usability and equitable access [

1].

Connectivity also extends to programmatic strategies. Universities that host cultural events, community outreach programs, and open-access learning initiatives contribute to intellectual and social enrichment beyond academia. Such activities foster reciprocal exchanges between universities and their cities, strengthening civic legitimacy and reinforcing their role as drivers of cultural vitality. In this evolving model, the campus emerges as both a spatial and societal interface—one that advances educational goals while supporting urban resilience, liveability, and community engagement.

2.4. Sense of Community

The

Sense of community in Campus public spaces–including furniture and equipment-is important to create interactions not only for students, faculty, and staff, but also for urban populations that engage with campus facilities [

34,

35]. Public spaces are central to this framework, functioning as enablers of community-building and informal social interaction. They play a critical role in shaping what Oldenburg defines as “third places”—neutral settings beyond home and work that facilitate inclusive encounters across diverse groups [

40,

41,

42]. On campuses, the relevance of third places is amplified by population diversity and fluidity. Students, faculty, staff, and visitors embody a wide spectrum of cultural, social, and economic backgrounds. Campus life encompasses overlapping communities—some permanent, others transient—ranging from formal institutional structures to informal networks organized around shared interests or digital platforms. These dynamics demand shared and accessible environments where both planned and serendipitous encounters can occur [

35].

Spaces such as plazas, libraries, cafés, and outdoor seating areas are thus essential for cultivating a vibrant and cohesive campus culture. They not only facilitate daily socialization but also support intercultural exchange, emotional belonging, and the development of interpersonal networks. Designing such spaces requires grounding in principles of inclusivity and diversity, ensuring responsiveness to a variety of user needs and practices.

Inclusive design extends beyond physical accessibility to social and cultural accessibility. This entails flexibility—providing quiet areas alongside active zones, formal and informal seating, and opportunities for both individual and collective use [

1]. Cultural sensitivity is equally important: for international students and visitors, elements such as culturally resonant vegetation, public art, or food offerings can foster familiarity and comfort. Through these strategies, campus public spaces become environments where diversity is acknowledged and celebrated, strengthening community ties and enhancing the overall liveability of the campus.

3. Methodology

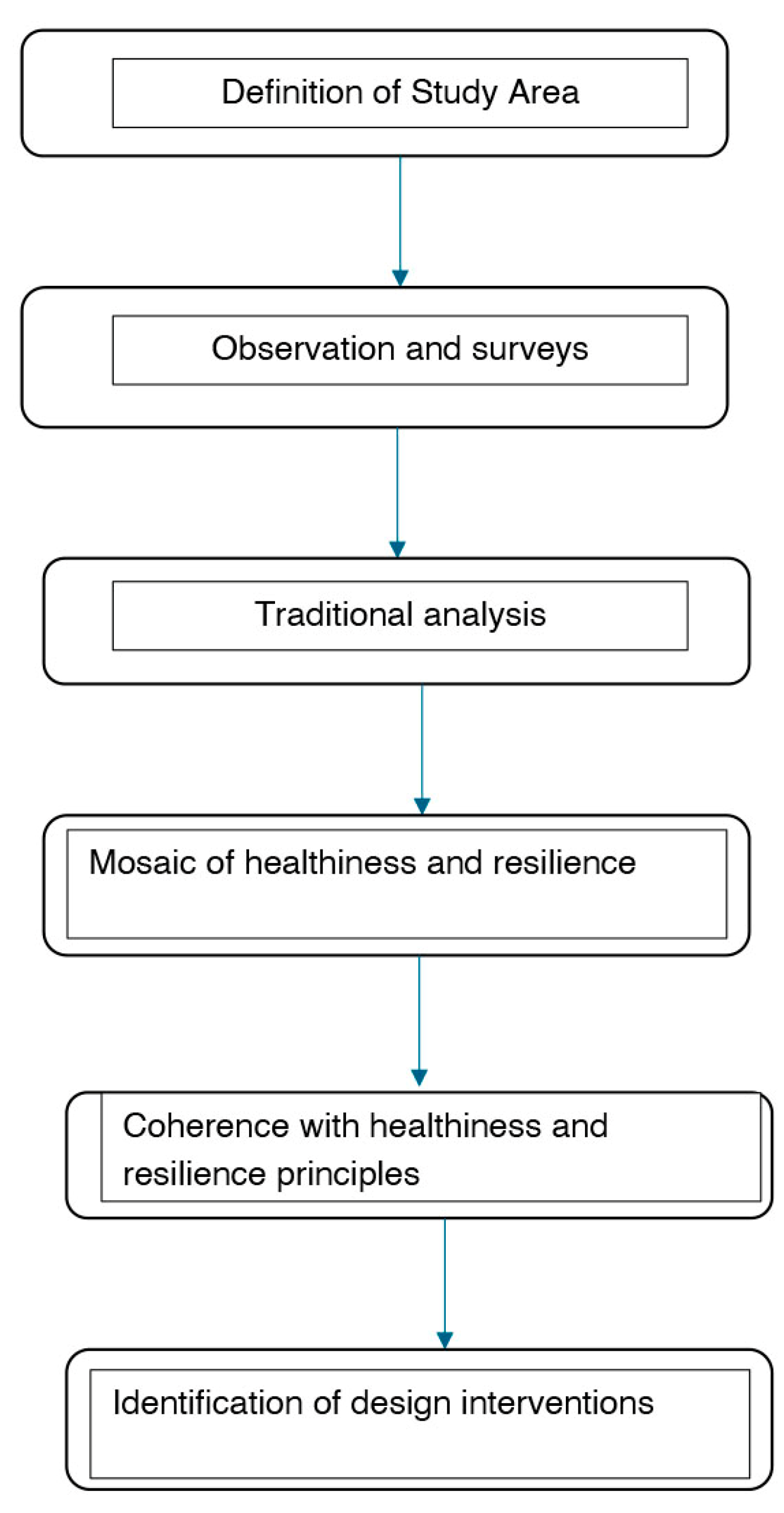

In recent decades, the understanding of university spaces has evolved beyond their traditional role as functional supports for teaching and research (

Figure 1).

They are now increasingly regarded as complex environments that influence psychological and physical well-being, quality of life, and the sociality of academic communities. Within this framework, it becomes necessary to employ a methodology conceived as an innovative tool for the analysis, design, and transformation of university public spaces. This methodology is grounded in an integrated approach that combines direct surveys, cartographic tools, and universal principles of healthiness and urban liveability [

40]. The methodological framework is articulated into six sequential phases, designed to ensure a logical progression from observation to design proposal.

Phase 1 consists of defining the study area within the campus. This preliminary step is essential to circumscribe the scope of investigation, establishing the physical and functional boundaries of the university public space under analysis. Through site visits and preliminary observations, the main gathering areas, circulation routes, and connection nodes are identified, providing the operational basis for subsequent analyses.

Phase 2 focuses on the systematic observation and classification of the physical, social, and perceptual characteristics of public spaces, as well as the movements and behaviours of people traversing them. Quantitative and qualitative data are collected on flows, activities, and user categories, distinguishing among students, faculty, technical staff, visitors, and members of the surrounding community. The observation framework (

Table 1) records the type of activity (leisure, transit, sports, work), the quantity of people, and their frequency and pace of movement, each evaluated on a Low–Medium–High scale. This allows for a comparative analysis of intensity, rhythm, and spatial distribution of use.

Simultaneously, the perceptual dimension of space is explored through on-site and survey-based assessments that capture users’ sensory experiences (

Table 2). Visual, acoustic, olfactory, tactile, gustatory, and mixed perceptions are documented, each rated in terms of quantity (Low–Medium–High) and quality (Pleasant–Neutral–Disturbing). This dual evaluation recognizes that environmental quality derives not only from measurable physical parameters but also from the subjective sensations and affective responses elicited by place.

The phase also includes the cataloguing of facilities, equipment, and furnishings (

Table 3), assessing their type, characteristics, and maintenance status using the same Low–Medium–High scale. Special attention is given to sustainability-oriented devices—such as solar-powered lighting or recycling bins—and to artistic or symbolic elements like sculptures or street art, which contribute to the identity and inclusiveness of the space.

Overall, Phase 2 provides a multi-layered understanding of campus public spaces by combining behavioural observation, sensory perception, and infrastructural assessment. The use of standardized parameters (Low–Medium–High) ensures comparability across sites and facilitates the translation of empirical observations into design and management guidelines.

Phase 3 involves traditional cartographic and morphological analysis. This stage examines the physical components of the campus context—roads, green areas, buildings, and infrastructures—placing them within an overall vision. It is a crucial step for understanding the relationship between the academic space and the surrounding urban fabric, as well as for highlighting the potential and criticalities of the existing morphological structure.

Phase 4 identifies the elements of healthiness and resilience within the campus public spaces by superimposing the information collected in the previous phases. The objective is to create a composite map highlighting which areas are healthier and more resilient, and which require corrective interventions. This synthesis provides the foundation for comparative evaluation.

Phase 5 consists of assessing the degree of healthiness and resilience by verifying coherence with guiding principles. These principles, constituting a “Charter for Resilient and Liveable Campuses,” span material needs—such as cleanliness, maintenance, and removal of architectural barriers—as well as immaterial aspects, including place identity, educational functions, the presence of art, and the use of digital technologies for heritage enhancement.

The principles include:

Ensuring accessibility for all potential campus users;

Eliminating architectural barriers that discourage use;

Balancing natural, landscape, and infrastructural elements;

Designing flexible, adaptable spaces that can serve in both ordinary and emergency conditions;

Guaranteeing adequate natural and artificial lighting while minimizing artificial light pollution;

Maintaining cleanliness and proper upkeep;

Creating a sense of safety and protection for those walking, studying, or resting in public spaces;

Reducing or eliminating noise generated by transport systems;

Providing adequate cycling lanes and internal–external campus connections;

Using natural, preferably local, materials;

Incorporating water features that foster vitality;

Ensuring usability in diverse weather and seasonal conditions;

Preserving both place identity and intangible site characteristics;

Supporting varied functions such as play, relaxation, and walking;

Facilitating physical activity with equipment or dedicated spaces;

Promoting art in its various forms;

Encouraging participation and a sense of belonging;

Implementing effective wayfinding systems;

Paying attention to waste separation and recycling;

Recognizing healthy nutrition as an essential principle of campus sustainability.

This verification not only measures compliance with shared standards but also identifies criticalities and opportunities for improvement.

Phase 6 culminates in the identification of design interventions, elaborated on the basis of collected data. These interventions must align with the Charter’s principles and integrate coherently with the university’s strategic development plans. The final outcome is a comprehensive mosaic that not only represents the current state of public spaces but also outlines potential pathways for their transformation.

4. UBC Vancouver Campus

The methodology was tested on several exemplary university campuses whose public spaces represent key indicators of environmental and social quality for both academic communities and visitors. These include University of British Columbia (UBC Vancouver), Søndre Campus (Copenhagen), WU Vienna University of Economics and Business, University College Dublin (UCD), Wuhan University, Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology (XAUAT), and the University of California campuses at Berkeley and San Francisco–Mission Bay.

The comparative analysis of Søndre Campus, WU Vienna, and UCD highlights how European campuses function as resilient, inclusive, and liveable urban ecosystems. Each demonstrates strong connectivity with its urban surroundings through open spatial structures, pedestrian and cycling networks, and integration with public transport. Field observations and surveys confirm that these environments promote well-being through accessible, green, and multisensory spaces fostering study, leisure, and social interaction. Users value biodiversity-oriented landscapes, shaded seating, and multifunctional plazas enhancing comfort and year-round usability. Despite this, exposure to weather extremes underscores the need for more adaptive and climate-responsive design. In the North American context, UC Berkeley and UCSF Mission Bay offer two complementary models. Berkeley’s historic campus, embedded in the urban fabric, embodies a hybrid ecosystem where cultural memory, civic activism, and nature coexist. Mission Bay, conversely, represents a paradigm of health urbanism, integrating research, clinical care, and community well-being within a sustainable spatial framework. In China, Wuhan University and XAUAT demonstrate distinct yet convergent approaches. Wuhan integrates its campus within the natural landscape of Luojia Hill and East Lake, fostering contemplative and environmental harmony, while XAUAT’s design uses courtyards and experimental gardens as pedagogical spaces, merging learning, research, and social interaction. Among these case studies, the case of UBC Vancouver is of particular interest and will be illustrated in detail below. It represents a campus where public spaces embody resilience and liveability for all, in line with the broader planning principles of the city.

The University of British Columbia (UBC), headquartered in Vancouver, constitutes one of the most significant examples of a North American campus designed and managed according to advanced principles of environmental and social sustainability. The study area corresponds to the main campus, located on the Point Grey Peninsula, an extensive site combining academic, residential, cultural, and sports functions, interwoven with a complex system of open public spaces. The delimitation follows a dual logic: on the one hand, the physical and administrative boundaries of the campus, regulated by controlled access; on the other, the perception of the public spaces actually used by users. Within this perimeter, particular importance is given to central plazas (such as Martha Piper Plaza), pedestrian and cycling greenways, courtyards within academic buildings, equipped green areas, commons, outdoor sports facilities, and informal recreational spaces. A specific focus is directed toward the relationship with the surrounding context: UBC stands on the unceded traditional territory of the Musqueam community, which confers a functional, environmental, and cultural-symbolic value to its public spaces. Artistic installations, Indigenous works, and participatory processes aimed at recognizing local cultural heritage are thus integral to the study area definition. Phase 1 therefore produces a clear delimitation of the study area, comprising the main public spaces, slow-mobility corridors, and activity nodes guiding population flows.

Phase 2 relies on direct and indirect surveys to map activities, flows, perceptions, and material provisions. Data sources include field visits and survey-based investigations, which provided both qualitative and quantitative information on the use and perception of public spaces.

The campus population is highly heterogeneous, including undergraduate and graduate students, researchers, faculty, technical and administrative staff, visitors, and members of local communities.

The intensity of use varies according to the time of day and the academic calendar: daytime is characterized by circulation and study/work activities; breaks coincide with social and recreational practices, while specific areas host sports, leisure, and cultural events. Movement rhythms are diverse: fast along classroom–library connections, moderate along greenways, and slow in plazas and commons where pauses prevail.

Sensory perceptions reveal an overall positive image: visually, modern buildings alternate with green landscapes and panoramic views of the ocean and mountains; acoustically, the environment is generally pleasant due to limited car traffic, although higher noise levels are recorded near main road nodes; natural scents of grass and wood positively influence olfactory perception; tactile sensations are enhanced by the use of natural materials such as wood and stone in pavements and furnishings.

Equipment includes benches, waste-sorting bins, lighting, bike racks, playgrounds, and sports facilities (

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). Sustainable technologies such as solar lighting, rainwater management systems, and digital information panels are widespread, while maintenance standards remain consistently high.

Artistic and cultural features—particularly Indigenous installations—endow public spaces with a strong cultural identity: far from mere decoration, public art stimulates reflection, belonging, and recognition of local communities. Example tables are represented in the following (

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6).

Cartographic and morphological analysis allows the identification of the campus’s physical and infrastructural elements and their alignment with healthiness objectives (

Figure 7). The system appears compact, with clear distinctions among central academic areas, student residences, sports facilities, and services. The open-space network functions as green infrastructure connected both to surrounding natural areas and to internal mobility systems. Main entrances are designed to favour multimodal transport—bus, cycling, and pedestrian flows—while reducing car dependency through greenways and progressive pedestrianization of internal streets. Landscape integration is of great value: proximity to the ocean and forests enhances aesthetic attractiveness, strengthens perceptions of healthiness, and provides daily opportunities for contact with nature. District energy systems and LEED Gold building standards demonstrate an advanced sustainability approach, while the innovative

Resilience Hubs provide spaces for ordinary social activities that can be rapidly transformed into community support centres during emergencies. This phase systematically maps material and infrastructural components, confirming alignment with sustainability goals and highlighting resilience as a guiding criterion.

Phase 5 synthesizes evidence from surveys and cartographic analysis to identify factors underpinning UBC’s resilience and liveability. Key strengths include: Environmental quality, expressed through abundant green spaces, connection with surrounding nature, and use of natural, sustainable materials;

Mobility, with an extensive network of pedestrian and cycling paths and reduced car use; Social accessibility, reflected in inclusive gathering spaces and participatory processes involving students, staff, and the Musqueam community; Resilience and safety, demonstrated by the presence of Resilience Hubs and sustainable energy infrastructures; Cultural value, shaped by a visual and symbolic identity reinforced through public and Indigenous art.

Challenges remain, however: limited coverage reduces year-round usability; residual architectural barriers persist in secondary areas; there is demand for more light sports and informal social facilities; and some traffic nodes generate noise levels that compromise acoustic comfort.

Verification against the Charter principles confirms that UBC transmits widespread feelings of well-being and happiness, supported by abundant greenery, perceived safety, and vibrant social life. Spaces are not limited to students but also attract families, children, and seniors, particularly in green and cultural areas, confirming intergenerational inclusivity. Accessibility measures are largely effective, though some barriers remain in older facilities. Balance between natural elements and infrastructure is well achieved, lighting is adequate though sometimes excessive, and maintenance is consistently high. Noise is reduced in central areas but persists near traffic corridors. Cycling infrastructure is widespread, though intersections require improvements. Sensory quality is enriched by natural scents and tactile use of local materials. Public spaces support a moderate rhythm of daily activities, with ample opportunities for pause, walking, and socialization, though seasonal usability declines in winter due to harsh, rainy weather. Campus identity is strongly preserved through ties with the Musqueam community and Indigenous art. Functional diversity is ensured by a variety of study, leisure, sports, and cultural areas, though light physical activities could be better supported by specific equipment. Public art is highly valued, and playful, interactive elements could be expanded. Educational functions are enriched by panels, museums, and learning trails, complemented by digital technologies enabling interactive engagement.

Phase 6 translates findings into concrete design interventions. For UBC, priority actions include:

Development of climate-adaptive infrastructures such as lightweight canopies, pergolas, and covered multifunctional areas; introduction of more water elements (fountains, reflecting pools, interactive installations) to reinforce sensory and symbolic dimensions; completion of universal accessibility, eliminating residual barriers and redesigning secondary routes inclusively; expansion of sports and fitness facilities (e.g., gentle exercise areas, yoga spaces, fitness trails); enrichment of public art, integrating interactive and playful installations; strengthening of cycling infrastructure, focusing on safer intersections and increased bike parking; implementation of digital tools for communication and storytelling, to promote cultural heritage and community belonging.

These interventions are fully consistent with the strategies of

Campus Vision 2050 [

20,

43] already underway at UBC in the fields of sustainability, resilience, and inclusion. Collectively, they consolidate the image of the campus as an international model of healthy, liveable, and joyful public space [

44].

5. Observations on the Case Study

UBC has developed as a complex urban ecosystem, capable of integrating academic, residential, cultural, and recreational functions within a high-value landscape setting. In this perspective, resilience and liveability are not ancillary outcomes but guiding criteria that inform the entire life cycle of public space: from morphological layout to material choices, from water management to programming and use, through to the construction of identity and belonging. The underlying premise is that an environment able to host everyday practices under ordinary conditions—study, encounter, play, movement, contemplation—is also an environment that, under extraordinary conditions, can absorb shocks, reorganize, and ensure continuity of essential services.

In terms of climate adaptation, the resilience strategy takes shape through infrastructures that connect physical and social dimensions. The Resilience Hubs represent the fulcrum of this vision: hybrid places that, in normal times, support programs for well-being, sociality, and learning, while, in emergencies, reconfigure as cooling centres and hubs for the distribution of water and food, and for access to energy and information. Their effectiveness depends not only on technical solutions (energy efficiency, emergency systems, network redundancy), but also on universal accessibility, proximity to pedestrian flows, and symbolic recognizability, so that they are perceived as common goods rather than sector-specific facilities.

Campus liveability is supported by a coherent network of open spaces that privileges walking and cycling. Greenways, plazas, and commons are conceived as devices for ecological and social continuity: by connecting buildings and amenities, they sustain active mobility, multiply opportunities for informal encounter, and increase perceived safety through the steady presence of users and legible routes. Within this light infrastructure, the use of natural, locally sourced materials (wood, stone), vegetative shading, permeable surfaces, and distributed stormwater management mitigates heat islands, runoff, and environmental stress, translating biophilic design principles into accessible sensory experiences—scents of grass and wood, tactile textures, and views toward the ocean and forests.

The cultural dimension is another structural lever of resilience. Collaboration with the Musqueam community and the integration of public art—with particular emphasis on Indigenous works—acknowledge the identity of place and activate a pedagogy of space that connects memory, care, and territorial justice. Far from mere decoration, art functions as a language of mediation and cohesion: it marks routes, renders nodes recognizable, produces shared narratives, and strengthens symbolic anchoring as well as the quality of experience.

To enhance the analytical and operational clarity of the case study, the identified strengths and challenges can be systematized through a priority matrix that evaluates each proposed action according to its impact and feasibility, and associates it with a suggested timeframe (short, medium, or long term). High-impact and high-feasibility actions include the expansion of shaded and permeable areas, the improvement of cycling networks, and the integration of interactive public art—all of which can generate tangible benefits for comfort, mobility, and cultural inclusion within a short to medium horizon. Medium-impact interventions with lower feasibility, such as the extension of resilience hubs or the implementation of advanced stormwater systems, would require longer-term planning and additional funding.

6. Conclusions

The paper has illustrated the main factors of liveability and resilience in campus public spaces, together with an original methodology for their analysis and design. Among the case studies, the best practice of the University of British Columbia (UBC) in Vancouver was examined, revealing that resilience and liveability are not merely desirable attributes but structural components of a sustainability framework capable of enduring over time. The most significant outcome lies not in the sum of individual interventions, but in the systemic quality that interrelates them: legible and connected open spaces, inclusive governance, a culture of place, ecological resource management, and climate adaptation capacity. This interweaving generates positive externalities across multiple dimensions—environmental, social, health-related, and educational—consolidating the campus as a civic platform that promotes public well-being beyond institutional boundaries.

From a theoretical perspective, the UBC case confirms that resilience extends beyond resistance to disturbances, incorporating institutional learning and the redefinition of practices of use. Liveability, in turn, transcends aesthetic or perceptual aspects to function as an everyday infrastructure encompassing active mobility, shading and microclimatic comfort, spaces for rest and encounter, universal accessibility, and perceived safety. When these elements are coherently coordinated and properly maintained, the university campus becomes a device capable of reducing vulnerabilities, generating social capital, and enabling healthy behaviours. The integration of art and place memory—particularly through dialogue with the Musqueam community—demonstrates that culture forms part of the cognitive security of space: it orients, includes, and empowers.

From a methodological standpoint, the proposed approach has proven effective in organizing heterogeneous data—field surveys, sensory perceptions, and cartographic analyses—and translating them into actionable strategies. Its added value lies not only in the sequencing of phases but also in the iterative possibility of revisiting results through the lens of the Charter of Resilient and Liveable Campuses. This verification distinguishes between superficial compliance and genuinely experienced quality, preventing sustainability from being reduced to certifications or performance standards disconnected from everyday life. The integration of both quantitative and qualitative dimensions—metrics and narratives such as indicators, perception maps, and climate diaries—emerges as crucial for informed, context-sensitive decision-making that accounts for seasonal dynamics and diverse social needs.

From a theoretical contribution standpoint, the integration of the Curriculum + Charter represents a transferable and comparable framework for campus planning. It provides a replicable structure linking educational content (the Curriculum) with spatial and operational principles (the Charter), enabling institutions to evaluate and design their public spaces through a shared matrix of criteria. This framework can serve as a reference model adaptable to diverse cultural and environmental contexts, fostering cross-campus benchmarking and knowledge exchange in the field of sustainable campus development.

From an operational perspective, the UBC experience suggests three strategic trajectories that campuses—and, more broadly, large public estates—can adopt to reconcile adaptation, equity, and spatial quality. The first concerns the climatic maintenance of open spaces, moving beyond routine care toward seasonal management that includes permeable surfaces, lightweight shelters, wind screens, and low-impact thermal comfort devices. The second involves water as both environmental and cultural infrastructure: not only the technical management of stormwater, but also the staging of water cycles through educational and experiential installations such as fountains, small cascades, and visible collection systems. The third relates to slow mobility as a universal service, through protected cycling networks, continuous sidewalks, inclusive wayfinding, and micro-areas for gentle physical activity near residences and classrooms.

Looking ahead, the proposed methodology offers a scalable framework adaptable to other university campuses and large institutional estates worldwide. By integrating environmental performance with social and cultural dimensions, it provides a replicable model for the design and management of resilient and liveable public spaces. Nonetheless, certain limitations must be acknowledged: the study’s focus on a single case—the UBC Vancouver campus—may not capture the full diversity of geographical, climatic, or governance contexts elsewhere, and the predominance of qualitative data calls for further quantitative validation. Future research could therefore expand the empirical base and test the framework across different cultural and environmental settings, including healthcare facilities, research parks, and civic precincts, where similar dynamics of coexistence, mobility, and adaptation define the everyday landscape of collective life.