Evaluation of Groundwater Storage in the Heilongjiang (Amur) River Basin Using Remote Sensing Data and Machine Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Sources

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Interpolation Method

2.3.2. Calculation of Groundwater Reserve Changes

2.3.3. Trend and Correlation Analysis

2.3.4. GWSA-Driven Mechanism Based on RF–SHAP Methods

2.3.5. Pearson Correlation Coefficient Method

3. Results

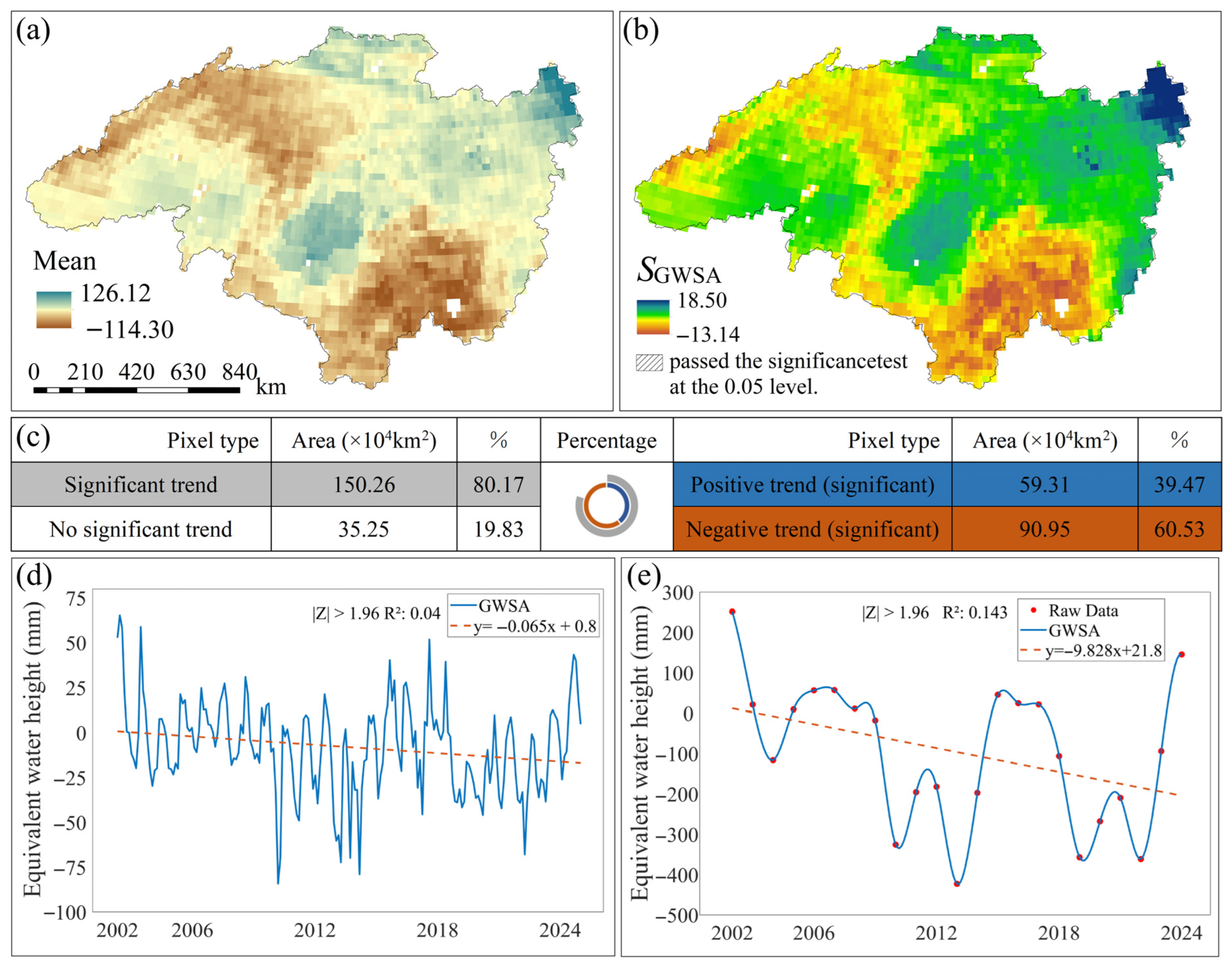

3.1. Spatio-Temporal Variation Characteristics of Groundwater Reserves

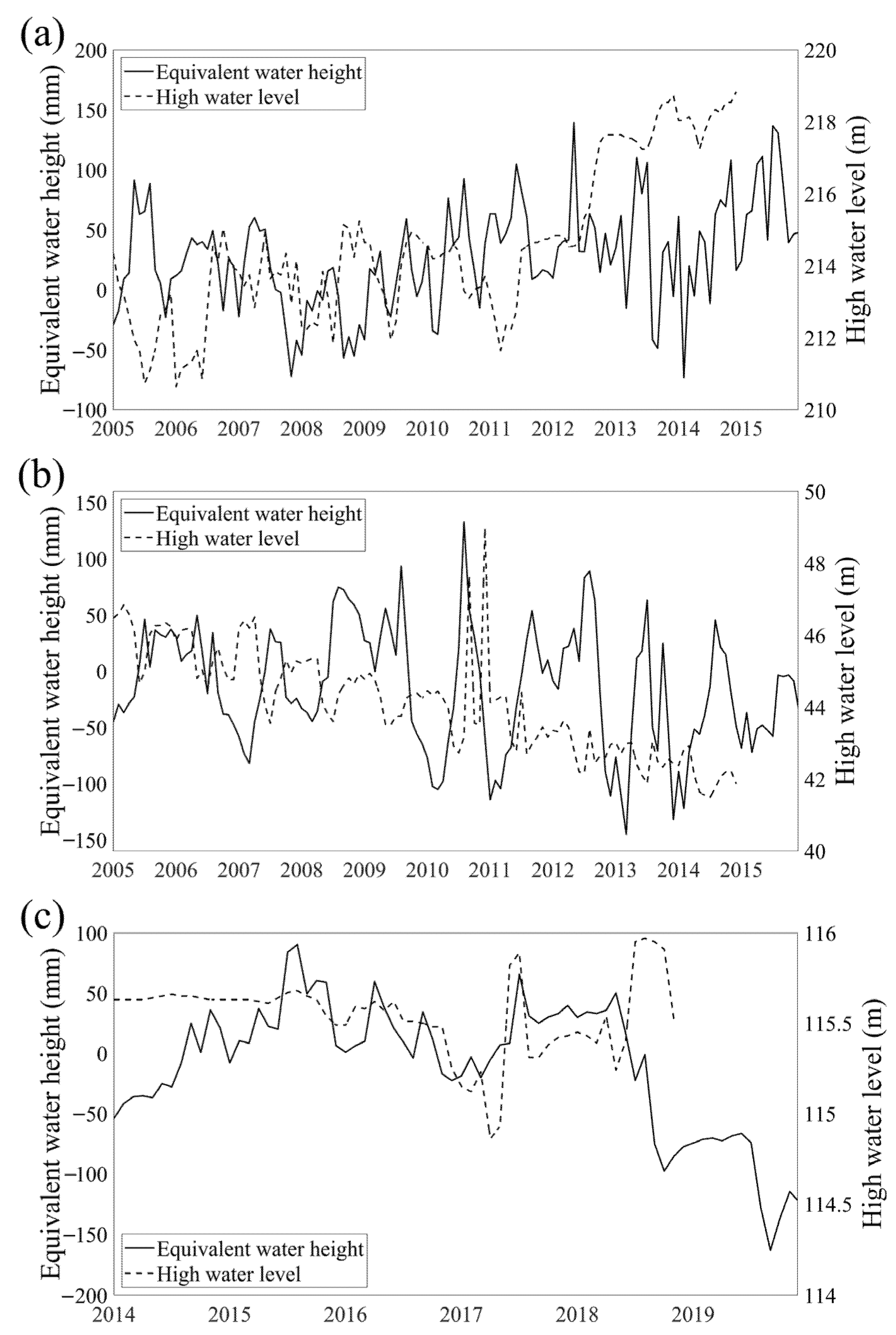

3.2. Correlation Analysis of Groundwater Reserve Variations

3.3. Correlation Analysis of GWSA with Key Driving Factors

3.3.1. Correlation Analysis with TEM

3.3.2. Correlation Analysis with PRE

3.4. Spatial Heterogeneity Analysis of GWSA and Dominant Factors

3.4.1. Spatial Heterogeneity Analysis of GWSA and TEM

3.4.2. Spatial Heterogeneity Analysis of GWSA and PRE

4. Discussion

4.1. Uncertainty Analysis of the Inversion Results

4.2. Spatial Analysis of Driving Mechanisms

4.2.1. Focusing Specifically on the Impact of TEM on GWSA

4.2.2. Focusing Specifically on the Impact of PRE on GWSA

4.2.3. In-Depth Analysis of the Impact of Human Activities on GWSA

4.3. Comparison with Other Cross-Border River Basins and Methods Within the Same River Basin

4.4. Limitations of This Study and Future Prospects

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zuo, Q.T. Research on sustainable utilization of water resources and its contribution to modern water control in China. Adv. Earth Sci. 2023, 38, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Márquez, C.; Posadas-Paredes, T.; Raya-Tapia, A.Y.; Ponce-Ortega, J.M. Natural Resource Optimization and Sustainability in Society 5.0: A Comprehensive Review. Resources 2024, 13, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Li, K.; Li, H.J.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Fu, T.L.; Sun, L.C.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.X. Water resource utilization and future supply–demand scenarios in energy cities of semi-arid regions. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.P.; Bantilan, C.; Byjesh, K. Vulnerability and policy relevance to drought in the semi-arid tropics of Asia—A retrospective analysis. Weather Clim. Extrem. 2014, 3, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.S.; Jayakumar, R.; Liu, K.; Wang, H.; Chai, R. Review on transboundary aquifers in People’s Republic of China with case study of Heilongjiang-Heilongjiang (Amur) River Basin. Environ. Geol. 2008, 54, 1411–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.Y.; Xu, C.C.; Gao, X.; Lu, C.Y.; Cao, B.; Guo, H.; Yan, L.J.; Wu, C.; He, X. Response of groundwater to different water resource allocation patterns in the Sanjiang Plain, Northeast China. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2022, 42, 101156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frappart, F.; Ramillien, G. Monitoring Groundwater Storage Changes Using the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) Satellite Mission: A Review. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Nan, Z.; Cheng, G. GRACE Gravity Satellite Observations of Terrestrial Water Storage Changes for Drought Characterization in the Arid Land of Northwestern China. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 1021–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Li, G.; Zhu, Z.; Hao, Y.; Hao, H.; Yao, J.; Bao, T.; Liu, Q.; Yeh, T.-C.J. Analysis of the spatiotemporal variation of groundwater storage in Ordos Basin based on GRACE gravity satellite data. J. Hydrol. 2024, 632, 130931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Famiglietti, J.S.; Lo, M.; Ho, S.L.; Bethune, J.; Anderson, K.; Syed, T.H.; Swenson, S.C.; de Linage, C.R.; Rodell, M. Satellites measure recent rates of groundwater depletion in California’s Central Valley. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2011, 38, L03403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlon, B.R.; Longuevergne, L.; Long, D. Ground referencing GRACE satellite estimates of groundwater storage changes in the California Central Valley, USA. Water Resour. Res. 2012, 48, W04520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arega, K.A.; Birhanu, B.; Ali, S.; Hailu, B.T.; Tariq, M.A.U.R.; Adane, Z.; Nedaw, D. Analysis of spatio-temporal variability of groundwater storage in Ethiopia using Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) data. Environ. Earth Sci. 2024, 83, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xiang, L.; Steffen, H.; Wu, P.; Jiang, L.; Shen, Q.; Li, Z.; Hayashi, M. GRACE-based estimates of groundwater variations over North America from 2002 to 2017. Geod. Geodyn. 2022, 13, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massoud, E.C.; Purdy, A.J.; Miro, M.E.; Famiglietti, J.S. Projecting groundwater storage changes in California’s Central Valley. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Li, T.; Cheng, S.; Wang, X. Spatial Distribution Exploration and Driving Factor Identification for Soil Salinisation Based on Geodetector Models in Coastal Area. Ecol. Eng. 2020, 156, 105961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Sun, Y.; Chen, Z.; Yan, H.; Qian, S. Dynamic Changes of Vegetation Ecological Quality in the Yellow River Basin and Its Response to Extreme Climate During 2000–2020. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2022, 42, 4524–4535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Z.; Li, C.; Zhao, J.; Li, Z.; Chen, K.; Huang, X.; Zhao, Z. The Temporal and Spatial Evolution Characteristics and Driving Factors of Ecosystem Service Bundles in Anhui Province, China. Land 2024, 13, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liang, Q.; Hancock, J.T.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M. Feature selection strategies: A comparative analysis of SHAP-value and importance-based methods. J. Big Data 2024, 11, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Broeck, G.; Lykov, A.; Schleich, M.; Suciu, D. On the tractability of SHAP explanations. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2022, 74, 851–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Hutson, A.D. A robust Spearman correlation coefficient permutation test. Commun. Stat.-Theory Methods 2024, 53, 2141–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, S.N. On correlation coefficients and their interpretation. J. Orthod. 2022, 49, 359–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Shan, F.; Yue, H.; Wang, X.; Fan, Y. Global analysis of the correlation and propagation among meteorological, agricultural, surface water, and groundwater droughts. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 333, 117460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurstone, L.L. A method of calculating the Pearson correlation coefficient without the use of deviations. Psychol. Bull. 1917, 14, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee Rodgers, J.; Nicewander, W.A. Thirteen ways to look at the correlation coefficient. Am. Stat. 1988, 42, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.; Li, M.; Zhang, Z. Study on hydrogeological regionalization of Heilongjiang (Amur River) Basin. Eng. J. Heilongjiang Univ. 2021, 12, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.L.; Xia, Z.Q.; Cai, T.; Guo, L.D. Variations of temperature, precipitation, and extreme events in Heilongjiang River. Procedia Eng. 2012, 28, 326–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yue, Q.; Yu, G.; Miao, Y.; Zhou, Y. Analysis of Meteorological Element Variation Characteristics in the Heilongjiang (Amur) River Basin. Water 2024, 16, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, R.; Huang, Q.; Xia, J.; Wang, P.; Fang, Y.; Shamov, V.V.; Frolova, N.L.; She, D. Climate Warming-Induced Hydrological Regime Shifts in Cold Northeast Asia: Insights from the Heilongjiang-Heilongjiang (Amur) River Basin. Land 2025, 14, 980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.; Sneeuw, N. Filling the data gaps within GRACE missions using singular spectrum analysis. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2021, 126, e2020JB021227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; van Dam, T.; Sneeuw, N.; Collilieux, X.; Weigelt, M.; Rebischung, P. Singular spectrum analysis for modeling seasonal signals from GPS time series. J. Geodyn. 2013, 72, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abatzoglou, J.T.; Dobrowski, S.Z.; Parks, S.A.; Hegewisch, K.C. TerraClimate, a High–Resolution Global Dataset of Monthly Climate and Climatic Water Balance from 1958–2015. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 170191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, L.; Zhao, T.; Chen, X.; Lin, S.; Wang, J.; Mi, J.; Liu, W. GWL_FCS30: A Global 30 m Wetland Map with a Fine Classification System Using Multi–Sourced and Time–Series Remote Sensing Imagery in 2020. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2023, 15, 265–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Tian, P.; Zhang, H. Surface Water Changes in China’s Yangtze River Delta over the Past Forty Years. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 91, 104458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, E.W.; Jaiteh, M.; Levy, M.A.; Redford, K.H.; Wannebo, A.V.; Woolmer, G. The Human Footprint and the Last of the Wild: The Human Footprint Is a Global Map of Human Influence on the Land Surface, Which Suggests That Human Beings Are Stewards of Nature, Whether We Like It or Not. BioScience 2002, 52, 891–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, H.; Li, X.; Wen, Y.; Huang, J.; Du, P.; Su, W.; Miao, S.; Geng, M. A Global Record of Annual Terrestrial Human Footprint Dataset from 2000 to 2018. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, O.; Sanderson, E.W.; Magrach, A.; Allan, J.R.; Beher, J.; Jones, K.R.; Possingham, H.P.; Laurance, W.F.; Wood, P.; Fekete, B.M.; et al. Sixteen Years of Change in the Global Terrestrial Human Footprint and Implications for Biodiversity Conservation. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Gong, H.; Chen, B.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Z. Long-term and seasonal variation in groundwater storage in the North China Plain based on GRACE. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2021, 104, 102560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, T.Y.; Li, X.L.; Shum, C.K.; Ding, H.; Xu, X.Y. The Balance and Abnormal Increase of Global Ocean Mass Change from Land Using GRACE. Earth Space Sci. 2020, 7, e2020EA001104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houser, P.; Gottschalck, J.; Meng, C.-J.; Cosgrove, B.; Radakovich, J.; Bosilovich, M. The global land data assimilation system. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2004, 85, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Zuo, D.; Xu, Z.; Wang, G.; Peng, D.; Pang, B.; Yang, H. Attributing the Imp acts of Vegetation and Climate Changes on the Spatial Heterogeneity of Terrestrial Water Storage over the Tibetan Plateau. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlson, J.A.; Kim, S. Linear Valuation Without OLS: The Theil–Sen Estimation Approach. Rev. Account. Stud. 2015, 20, 395–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, P.; Basistha, A.; Sarkar, S.; Sachdeva, K. Trend Analysis and ARIMA Modelling of Pre–Monsoon Rainfall Data for Western India. Comptes Rendus Geosci. 2013, 345, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomari, Y.; Andó, M. SHAP-based insights for aerospace PHM: Temporal feature importance, dependencies, robustness, and interaction analysis. Results Eng. 2024, 21, 101834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, L. t-Test and ANOVA for data with ceiling and/or floor effects. Behav. Res. Methods 2021, 53, 264–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadollahi, A.; VB, M.K.; Ghimire, A.B.; Poudel, B.; Shin, S. The impact of climate change and urbanization on groundwater levels: A system dynamics model analysis. Environ. Prot. Res. 2024, 4, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Jin, H. Permafrost and groundwater on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and in northeast China. Hydrogeol. J. 2013, 21, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, D.; Pan, Y.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Y.; Hou, X.; Hong, Y.; Scanlon, B.R.; Longuevergne, L. Global analysis of spatiotemporal variability in merged total water storage changes using multiple GRACE products and global hydrological models. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 192, 198–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Xin, Z.; Cheng, Y. Groundwater storage changes and influencing factors in the Mongolian Plateau. J. Desert Res. 2025, 45, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhai, L.; Qiao, Q.; Liu, J. Changes of groundwater storage and their influencing factors in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region based on GRACE and GLDAS data. Sci. Surv. Mapp. 2023, 48, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Wang, Z. Detect Songhua River Basin Groundwater Spatiotemporal Variation Characteristics by GRACE and Multi-source Hydrological Data. Geomat. Inf. Sci. Wuhan Univ. 2023, 48, 1409–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, M.A.; Webster, R. Kriging: A method of interpolation for geographical information systems. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Syst. 1990, 4, 313–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Fang, S.; Han, J.; Yu, Y.; Wu, D. Analysis of groundwater storage anomaly and multisource influencing factors in the North China Plain. Natl. Remote Sens. Bull. 2025, 29, 677–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Peng, Y.; Liu, J.; Hao, C. Study on groundwater storage changes in Henan province during 2003–2022 derived from GRACE and GLDAS. Bull. Surv. Mapp. 2024, 10, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Dai, C.; Jing, Y.; Ru, Q.; Yan, F.; Zhang, Y. GRACE/GRACE-FO Satellite Assessment of Sown Area Expansion Impacts on Groundwater Sustainability in Jilin Province. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahr, J.; Swenson, S.; Zlotnicki, V.; Velicogna, I. Time-variable gravity from GRACE: First results. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2004, 31, L11501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swenson, S.; Wahr, J. Post-processing removal of correlated errors in GRACE data. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2006, 33, L08402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longuevergne, L.; Scanlon, B.R.; Wilson, C.R. GRACE Hydrological estimates for small basins: Evaluating processing approaches on the High Plains Aquifer, USA. Water Resour. Res. 2010, 46, W11517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Tang, X.; Yuan, G.; Zhang, X.; Sun, X. Chinese Ecosystem Research Network 2005–2014 Groundwater Data Set; Science Data Bank: Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Simulation and Dynamic Analysis of Groundwater Depression Funnel Control Following Reservoir Impoundment at Dadingzi Mountain Reservoir, Harbin. Master’s Thesis, Heilongjiang University, Harbin, China, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walvoord, M.A.; Kurylyk, B.L. Hydrologic impacts of thawing permafrost—A review. Vadose Zone J. 2016, 15, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, S.G.; Ge, S. Contrasting hydrogeologic responses to warming in permafrost and seasonally frozen ground hillslopes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2017, 44, 1803–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Dai, C.; Jing, J.; Liu, G.; Ru, Q.; Li, J.; Liu, P. Study on the relationship between surface water and groundwater transformation in the middle and lower reaches of Songhua river basin. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, D.; Yang, W.; Scanlon, B.R.; Zhao, J.; Liu, D.; Burek, P.; Pan, Y.; You, L.; Wada, Y. South-to-North Water Diversion stabilizing Beijing’s groundwater levels. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, G.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; Qu, X.; Wang, L.; Tong, S.; Zhang, M.; Li, X.; Zhang, W. Impacts of groundwater storage variability on soil salinization in a semi-arid agricultural plain. Geoderma 2025, 454, 117162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, S.; Cui, G.; Yan, L.; Tong, S. Hydro-salinity dynamics in a semi-arid agricultural plain: Implications for sustainable land management. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 178, 114100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Cui, G.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Tong, S.; Zhang, M. GRACE Satellite-based analysis of spatiotemporal evolution and driving factors of groundwater storage in the black soil region of Northeast China. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Famiglietti, J.S. The global groundwater crisis. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2014, 4, 945–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuthbert, M.; Gleeson, T.; Moosdorf, N.; Befus, K.M.; Schneider, A.; Hartmann, J.; Lehner, B. Global patterns and dynamics of climate–groundwater interactions. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2019, 9, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, B.; Li, Z.; Li, W. Water resource formation and conversion and water security in arid region of Northwest China. J. Geogr. Sci. 2016, 26, 939–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, Y.; Van Beek, L.P.; Van Kempen, C.M.; Reckman, J.W.; Vasak, S.; Bierkens, M.F. Global depletion of groundwater resources. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2010, 37, L20402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanshan, W.; Tong, J.; Xiucang, L.; Tengfei, W.; Yanjun, W.; Fischer, T. Changes of actual evapotranspiration over the Songhua River Basin from 1961 to 2010. Adv. Clim. Chang. Res. 2014, 10, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diadin, D.; Shandyba, D.; Drozd, O.; Yakovlev, V. Assessment of anthropogenic transformation of groundwater recharge conditions in urban areas. Ecol. Saf. Balanc. Use Resour. 2025, 16, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiflay, E.; Schirmer, M.; Foppen, J.W.; Moeck, C. Impact of urbanization on groundwater recharge: Altered recharge rates and water cycle dynamics for Arusha, Tanzania. Hydrogeol. J. 2025, 33, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodell, M.; Velicogna, I.; Famiglietti, J.S. Satellite-based estimates of groundwater depletion in India. Nature 2009, 460, 999–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asoka, A.; Gleeson, T.; Wada, Y.; Mishra, V. Relative contribution of monsoon precipitation and pumping to changes in groundwater storage in India. Nat. Geosci. 2017, 10, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Duy, N.; Nguyen, T.V.K.; Nguyen, D.V.; Tran, A.T.; Nguyen, H.T.; Heidbüchel, I.; Merz, B.; Apel, H. Groundwater dynamics in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta: Trends, memory effects, and response times. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2021, 33, 100746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Z. Study on Terrestrial Water Storage Changes in the Heilongjiang (Amur) River Basin Based on GRACE Satellite Data. Master’s Thesis, Heilongjiang University, Harbin, China, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Wang, C.-Q.; Mu, D.-P.; Zhong, M.; Zhong, Y.-L.; Xu, H.-Z. Groundwater storage variations in the North China Plain from GRACE with spatial constraints. Chin. J. Geophys. 2017, 60, 1630–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellazzi, P.; Longuevergne, L.; Martel, R.; Rivera, A.; Brouard, C.; Chaussard, E. Quantitative mapping of groundwater depletion at the water management scale using a combined GRACE/InSAR approach. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 205, 408–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béjar-Pizarro, M.; Ezquerro, P.; Herrera, G.; Tomás, R.; Guardiola-Albert, C.; Hernández, J.M.R.; Merodo, J.A.F.; Marchamalo, M.; Martínez, R. Mapping groundwater level and aquifer storage variations from InSAR measurements in the Madrid aquifer, Central Spain. J. Hydrol. 2017, 547, 678–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonotto, G.; Peterson, T.J.; Fowler, K.; Western, A.W. Identifying causal interactions between groundwater and streamflow using convergent cross-mapping. Water Resour. Res. 2022, 58, e2021WR030231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runge, J.; Bathiany, S.; Bollt, E.; Camps-Valls, G.; Coumou, D.; Deyle, E.; Glymour, C.; Kretschmer, M.; Mahecha, M.D.; Muñoz-Marí, J. Inferring causation from time series in Earth system sciences. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Positive Driving Factors | Shap Mean | % | Negative Driving Factors | Shap Mean | % | Model Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TEM | 1.3902 | 44.37 | PRE | −1.0826 | 37.17 | R2 = 0.87 |

| PET | 0.1722 | 3.94 | PDSI | −0.0589 | 5.14 | |

| SWE | 0.3743 | 3.20 | LUCC | −0.5566 | 3.33 | RMSE = 10.47 |

| SM | 0.0121 | 1.64 | NDVI | −0.0588 | 1.08 | |

| HFP | −0.0410 | 0.14 |

| Method | Temporal Dependency | Main Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Mean substitution | Almost ignored | Fails to reflect dynamic changes |

| Linear interpolation | Simplified local consideration | Inconsistent with the nonlinear physical processes of GRACE data |

| Cubic spline interpolation | Local consideration | Inaccurate reconstruction of trends and periodicity |

| Kriging interpolation | Mainly spatial dependence | Unsuitable for filling missing months in time series |

| Singular spectrum interpolation | Global and adaptive processing | Parameter selection and computation are complex |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, T.; Dai, C.; Zhang, K.; Liu, Y. Evaluation of Groundwater Storage in the Heilongjiang (Amur) River Basin Using Remote Sensing Data and Machine Learning. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9758. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219758

Sun T, Dai C, Zhang K, Liu Y. Evaluation of Groundwater Storage in the Heilongjiang (Amur) River Basin Using Remote Sensing Data and Machine Learning. Sustainability. 2025; 17(21):9758. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219758

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Teng, ChangLei Dai, Kaiwen Zhang, and Yang Liu. 2025. "Evaluation of Groundwater Storage in the Heilongjiang (Amur) River Basin Using Remote Sensing Data and Machine Learning" Sustainability 17, no. 21: 9758. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219758

APA StyleSun, T., Dai, C., Zhang, K., & Liu, Y. (2025). Evaluation of Groundwater Storage in the Heilongjiang (Amur) River Basin Using Remote Sensing Data and Machine Learning. Sustainability, 17(21), 9758. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219758