Abstract

The sustainable development of agrifood systems is a pressing global challenge, highlighting the need for frameworks that guide responsible investment and community engagement. The Principles for Responsible Investment in Agriculture and Food Systems (CSA-IRA), approved by the Food Security Council in 2014, provide such a framework. Recognizing this opportunity, the FAO selected the Gesplan Research Group of the Polytechnic University of Madrid in 2016 to promote these principles in Latin America, the Caribbean, and Spain, leveraging the expertise of PhD graduates in Projects and Planning for Sustainable Rural Development. The main objective of this research was to explore how teaching, research, and civil society engagement can be integrated to operationalize CSA-IRA principles and foster sustainable development. To achieve this, the study applied the “Working with People” model across multiple countries and contexts, using university–business collaborations to implement practical, socially responsible initiatives. Over nine years, the approach generated a network of 46 universities and 52 agrifood companies across 12 countries, demonstrating effective multi-stakeholder collaboration. The accumulated experience led to the proposal of the Metauniversity—a “university of universities”—as an innovative instrument to scale knowledge transfer, research, and community engagement. These findings highlight that structured, collaborative networks can translate CSA-IRA principles into tangible actions, offering a replicable model for sustainable agrifood development globally

1. Introduction

Higher education is currently undergoing a critical transformation, driven by global demands for sustainable development and the need for more effective responses to complex social problems. Traditional university models, although historically effective, are increasingly showing limitations in addressing the multifaceted challenges of the 21st century. This situation has sparked a profound debate about the need for new paradigms in higher education that enable greater integration among research, teaching, and social engagement [1]. The complexity of current problems, ranging from climate change to food security, requires approaches that transcend traditional institutional and geographical boundaries. In this context, there is a need to develop more adaptable and collaborative university models, capable of integrating diverse knowledge and experience on a global scale [2]. The concept of the Metauniversity [3] emerges as a potential response to these challenges, suggesting a structure that facilitates international collaboration and knowledge exchange while maintaining high academic standards. The Metauniversity is emerging as an innovative educational paradigm that redefines higher education through the integration of emerging technologies, artificial intelligence and digital twins [4]. This concept represents an evolution of the traditional university towards a flexible, inclusive and globally connected learning ecosystem.

The term “Metauniversity” was introduced by Charles Vest in 2006 [3], who envisioned a model of international higher education that transcended the physical barriers of traditional universities. Vest envisioned a system where open educational resources and digital tools would make education accessible to all, fostering global collaboration in research and access to quality resources no matter the student’s location or financial situation.

The evolution of this concept has been driven by the development of cloud-based learning platforms, Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) and digital knowledge networks [4]. The original idea, rooted in the Greek prefix “meta” (meaning “beyond”), suggests a “model of models” or a “university of universities”, a concept that, as will be seen below, goes beyond the abstraction of a traditional institution to encompass a global collaborative network of universities and companies [4] (Cazorla).

In the era of globalization and digitalization, the Metauniversity emerges, as well as a response to the need for new, more adaptable and collaborative university models. Its relevance is based on several key points such as: accessibility and inclusion by eliminating geographical, economic and social barriers; learning-based by doing for the acquisition of skills fostering critical thinking and innovation; personalization and flexibility promoting cultural diversity and lifelong learning; response to the problems and needs of society by focusing on practical skills [2].

The Metauniversity model is intrinsically linked to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and is seen as a tool to achieve multiple SDG [5]. Its approach, based on collaboration, innovation and equity, contributes directly to several targets: SDG 4 (Quality Education), SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure), SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities) and especially SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals) since the concept of MetaUniversity is based on global collaboration between educational institutions, business and civil society, embodying the spirit of partnerships to achieve sustainable development [5,6].

The Metauniversity is therefore not only a technological evolution of education, but a new paradigm that aligns higher education with the global needs of sustainability, equity and innovation. By creating collaborative and accessible learning ecosystems, it has the potential to transform education and empower new generations to build a more sustainable future [2,7,8,9].

To guide actions towards truly sustainable development, the Principles for Responsible Investment in Agriculture and Food Systems (CFS-IRA), adopted by the Committee on World Food Security (CFS) in 2014, provide a fundamental framework [10]. These principles, aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), seek to guide the actors involved—governments, the private sector, civil society and academia—towards development that promotes food security, gender equality, resource conservation and inclusive governance [11,12]. The need to transform agri-food systems towards more sustainable and inclusive models has put the CFS-RAI Principles in the international debate [13,14,15,16,17]. These principles constitute a voluntary framework that guides States, the private sector, civil society, and international organizations in mobilizing investments that contribute to food security, inclusive rural development, and environmental sustainability [18].

In Latin America, the application of the RAI principles is connected to the structural challenges of rural development such as access to land, land grabbing, market concentration, vulnerability to climate change, and the historical exclusion of peasant and indigenous communities in rural development [14]; the institutional weakness to guarantee transparency and accountability in projects [15]; and the difficulties in generating financial instruments accessible to small producers [16,17]

The CFS–RAI principles provide a widely accepted normative framework to guide responsible investments in agriculture and food systems in Latin America. Its implementation is now a field of research and priority action, especially on how to ensure that investments contribute to food security and sustainable rural development [13].

This work is framed in the confluence of two necessary trends: the evolution towards more collaborative university models in the field of sustainable development planning [19] and the growing need to apply guiding principles, such as the CSA-IRA Principles, in real contexts [18]. The Metauniversity’s proposal, promoted by the GESPLAN Research Group of the Polytechnic University of Madrid, is based on the “Working with People” (WWP) metamodel [20]. The WWP model is a participatory, multidimensional approach that connects knowledge and action through social learning, emphasizing the integration of human values, expert knowledge, and local expertise. It is structured in three interconnected dimensions: ethical-social, technical-business and political-contextual, which have proven to be effective in solving rural problems, improving governance and promoting sustainable development in various contexts in Europe and Latin America [13].

Previous research has validated the application of the CFS-IRA Principles in various contexts, demonstrating their ability to drive sustainable economic growth in rural areas, support the transformation of regions affected by illicit crops [21], and strengthen indigenous women’s cooperative systems [22]. Similarly, the WWP model has been validated as an effective framework for development planning, the creation of Local Action Groups [23,24], the strengthening of agri-food chains [17,25], and the promotion of rural entrepreneurship [26]. The synergy between the CFS-IRA Principles and the WWP model has been explored in projects that demonstrate improvements in producers’ livelihoods and successful access to international markets [13,27].

However, despite these advances, the joint application of these frameworks in a structure of inter-university, innovative teaching governance and business collaboration [28], such as the one proposed by the Metauniversity, has been scarcely explored. This article seeks to address this gap, analyzing how the structure of the Metauniversity, operating from the CSA-IRA principles and the WWP methodology, connects with current trends in sustainable development and aligns social innovation, participatory governance and the creation of multi-stakeholder networks.

This research aims to provide a robust theoretical and practical framework that illustrates how higher education institutions can evolve to lead the transition to a more sustainable and equitable future. For this purpose, the research is based on the outcomes of the FAO-UPM project, developed between 2016 and 2024, which, according to Cazorla et al. [29,30], enabled the implementation of a Metauniversity model specifically oriented toward sustainable development by the end of this period. According to Jiménez Aliaga et al., [25] this project has provided a unique laboratory to examine how higher education institutions can evolve to meet contemporary demands while preserving their core mission of knowledge creation and dissemination. As highlighted by Requelme and Afonso [10], the integration of the CSA-IRA Principles in this process has been essential to ensure that institutional transformation aligns with the goals of sustainable development.

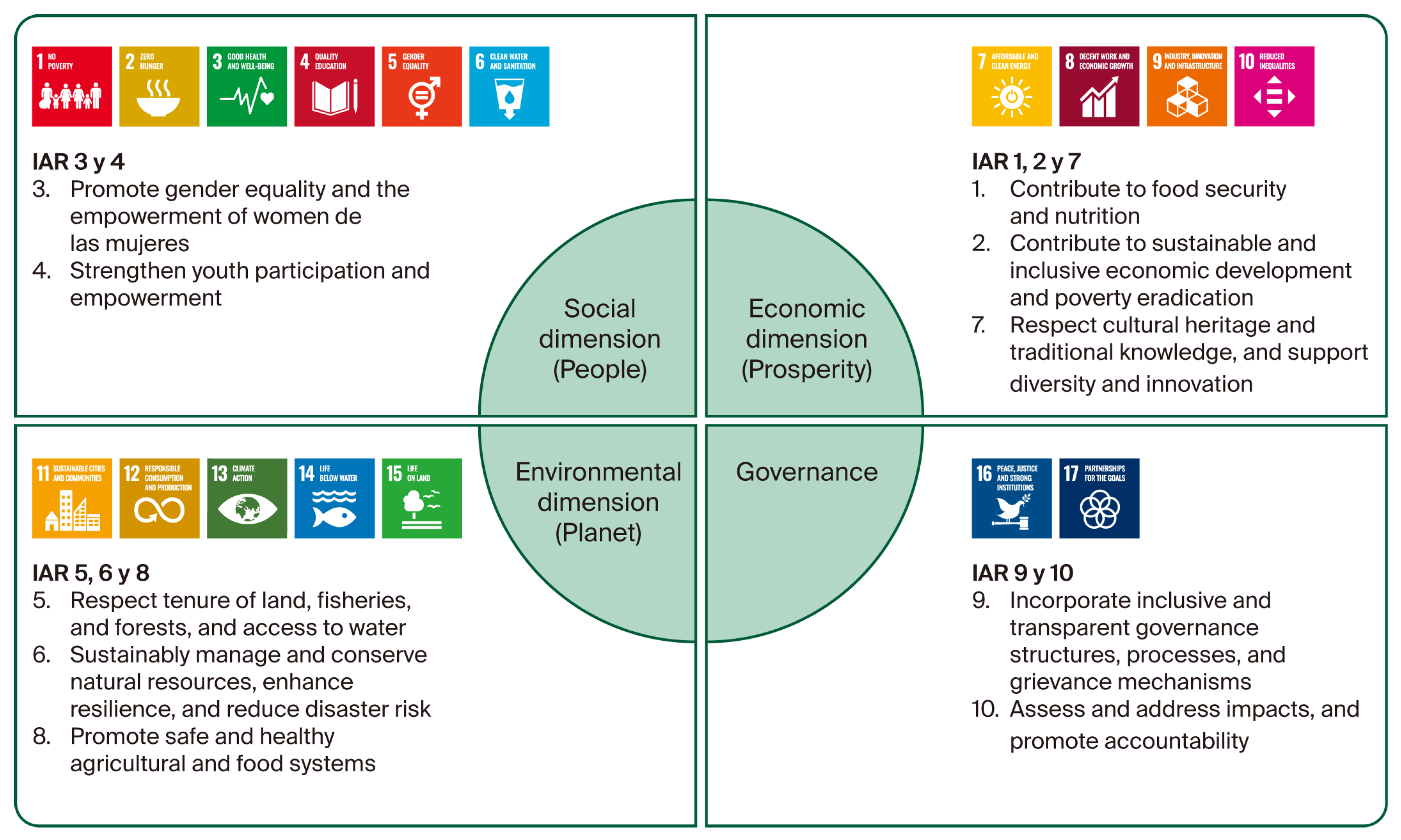

As we have seen, the theoretical framework of this research is based on three interrelated conceptual pillars. First, the CSA-IRA Principles (see Table 1), approved by the Committee on World Food Security in 2014, provide a fundamental basis for Responsible Investment in Agriculture and Food Systems [10]. These principles align with the Sustainable Development Goals through five key dimensions, Planet, People, Prosperity, Peace, and Partnerships [31], establishing a comprehensive framework for sustainable development.

Table 1.

CSA-IRA Principles. Source: Own elaboration based on [18].

Secondly, the paradigm of research universities, according to San Martin and Cazorla [1], evolves beyond traditional rankings by integrating three essential elements: research as a generator of knowledge, effective engagement with society, and relevant teaching, especially at the postgraduate level. This model is complemented by an efficient administrative structure and strategic leadership, recovering the original concept of the university as an institution for the generation and dissemination of knowledge [32].

Finally, the concept of the Metauniversity emerges as an innovative response to the contemporary challenges of higher education. As noted by Vest [3] and Couturier [4], this model facilitates knowledge transfer among academics, researchers, and society, leveraging digital technologies and promoting global cooperation [33]. This approach, according to Costanza et al., [2] represents a significant evolution in how higher education institutions can collaborate and share resources to address complex global challenges.

The integration of these three elements provides a robust theoretical framework for analyzing and understanding the evolution of higher education toward more collaborative and sustainable development-oriented models.

1.1. FAO, SDGs, and CSA-IRA Principles for Responsible Investment

The CSA-IRA Principles, approved by the Committee on World Food Security in October 2014, establish a comprehensive framework for promoting Responsible Investment in Agriculture and Food Systems [18]. As Requelme and Afonso [10] point out, these principles emerged in response to the need to guide stakeholders involved in food systems toward achieving sustainable development.

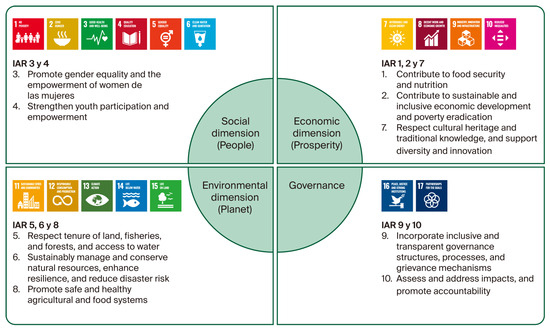

The conceptual framework links the SDGs with the CSA-IRA Principles through five core pillars, known as the 5 Ps: People, Planet, Prosperity, Peace, and Partnership [8]. Afonso et al. [10] emphasize that this structure enables the classification of research and experience according to different dimensions of sustainability:

The social dimension (People), as noted by De los Ríos et al., [13,24] focuses on eradicating poverty and hunger, relating to SDGs 1–6. These goals are connected to CSA-IRA Principles 3 and 4, which center on gender equality and youth empowerment [10,25].

The environmental dimension (Planet), according to Castañeda et al. [34] and Cachipuendo et al. [16], focuses on protecting natural resources and combating climate change. SDGs 11–15 are associated with this dimension, and their connection to CSA-IRA Principles 5, 6, and 8 concerns respecting land tenure and conserving natural resources [35].

The economic dimension (Prosperity) refers to aspects related to sustainable economic growth, decent employment, and the reduction in economic inequalities. The most relevant SDGs for this dimension are 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11, and they align with CSA-IRA Principles 1, 2, and 7, which focus on economic growth [36,37,38]. From the governance dimension (Peace and Partnership), the goal is to achieve strong alliances and well-structured governance systems [39]. This dimension is linked to SDGs 16 and 17 and to CSA-IRA Principles 9 and 10, which specifically emphasize the incorporation of solid institutional structures, accountability, and transparency in management [30,35]. Figure 1 summarizes these dimensions of the CSA-IRA Principles and SDO.

Figure 1.

CSA-IRA Principles and SDO. Source: Own elaboration based on [8].

Between 2012 and 2014, FAO’s general policy was enriched during the approval process of the CSA-IRA Principles. In addition to its traditional engagement with governments as a United Nations multilateral agency, the FAO began to actively incorporate long-term collaboration with civil society, represented by universities, associations, cooperatives, and enterprises operating in rural areas. This shift reinforced the role of FAO’s Partnerships and UN Collaboration Division [34]. As a result, universities began to play an increasingly relevant role, thanks to their dynamic research–action relationships with businesses and associations aiming to achieve sustainable development [19,40].

1.2. The New Paradigm of Research Universities and Their Relationship with Society: The Polytechnic University of Madrid

Until the end of the 20th century, much attention was given to world-class universities and their characteristics to be included in this elite group [40]. These components closely aligned with the indicators that the most prestigious global rankings would begin to use a few years later to classify universities, considering the quality and scope of research as a key factor [1]. However, this key role of research, though always important, was not clearly connected to other crucial aspects of good university governance, such as faculty development, links to teaching, or the real-world needs of the society that universities should serve and help improve.

This was the context in which, in 2003 and 2004, three global university rankings were published: the Shanghai Ranking from Jiao Tong University, the Webometrics Ranking by the Higher Council for Scientific Research (CSIC), and The Times Higher Education Ranking. A fourth, Quacquarelli Symonds (QS), was added in 2012. Starting in 2005, the term “research” became increasingly attached to the concept of “university,” not merely to describe institutions that prioritize research—a clear and longstanding trait—but to introduce a new concept with broader ambitions [41].

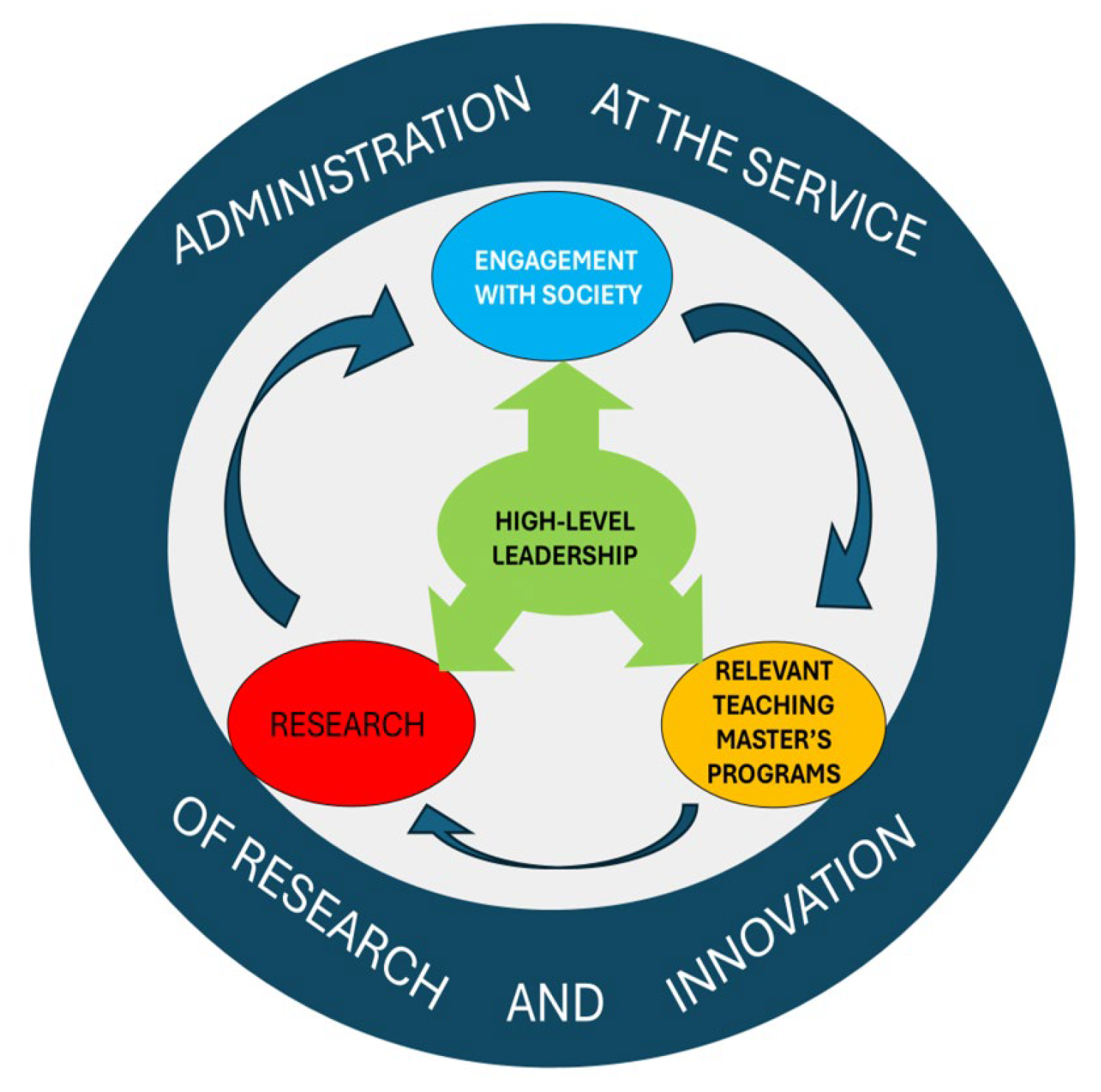

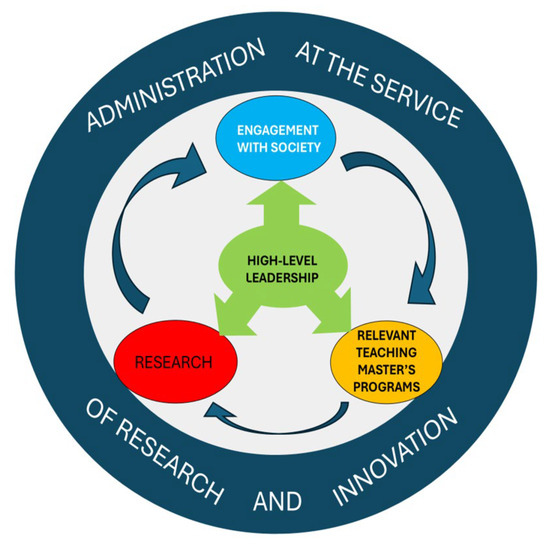

Cazorla & Stratta [40] identify three fundamental pillars of the research university paradigm: research as a driver of knowledge aligned with societal needs, engagement with society, and relevant teaching, especially in master’s programs. Drawing from their experience as vice-rectors of research universities, San Martin and Cazorla [1] complete this approach with two additional and less clear elements necessary for the effective governance of a university: an administrative structure that supports this triad of excellence, and a high-level leadership capable of understanding and meeting the demands of such a challenge.

Figure 2 schematically presents this framework, illustrating this new paradigm of the research university, a model that defines it as a true engine of social transformation [40]. The model is based on five fundamental pillars that, together, create a dynamic institution that generates and disseminates knowledge to respond to the needs of society: (1) Research: it is the central pillar, conceived as an engine of knowledge aligned with the real problems and opportunities of Society; (2) Engagement with society: It reflects the real link between the university and its environment, ensuring that the knowledge generated has a positive impact; (3) Relevant teaching: Focused especially on postgraduate studies (master’s and doctorate), to train graduates with high intellectual, creative and innovative preparation; (4) Administrative support structure: An efficient governance support that is essential to sustain excellence in the other pillars; and (5) High-level leadership: strategic leadership capable of guiding the institution to meet the complex demands of this model [42].

Figure 2.

The five pillars of research universities. Source: Own elaboration.

These five pillars define the essential elements for a university to be considered a true engine of social transformation, as Cazorla & Stratta [40] put it, integrating knowledge generation with sustainable development. A university that addresses societal problems or opportunities through innovative knowledge—technological, legal, economic, humanistic, etc.—is a living institution that reclaims the original purpose of the university: not only as a guardian but also as a generator and disseminator of knowledge [10]. This is achieved by faculty, typically working in teams, through their publications and the design of postgraduate programs—master’s and doctorate—ensuring that graduates are intellectually, creatively, and innovatively prepared [23,43].

The link between the emergence of global rankings and the new paradigm of research universities has already been noted. Although not developed here, the literature shows that Webometrics, through its indicators, transparency, and openness, best reflects the reality of research universities. It offers more than just a static metric: it provides a path for governance improvement for any university aspiring to become a research university [44,45,46]. In this way, research universities emerge as highly suitable systems and key instruments to address the complex challenge of sustainable development.

The Polytechnic University of Madrid (UPM) elected a new rector in 2004 who, along with his team, undertook as a governance program the goal of transforming the institution into a research university within the eight-year duration of his mandate. The governance measures and their impact on rankings were significant—the creation of research structures, master’s programs, and stronger engagement with society, among many others—which positioned UPM among the top 300 universities in the world [1]. One of the research groups at this university, known as Gesplan (Research in Planning and Sustainable Management of Rural/Local Development) [19], had been working for years under this approach—one of its members had been trained at UC Los Angeles—establishing a network of PhD holders in Latin America (LA) and Spain, many of whom are faculty at universities in those countries. This drew the attention of the FAO in 2016 to undertake a very innovative program—the first of its kind—to connect the United Nations multilateral organization with universities, the business sector, and associative and cooperative networks to promote the dissemination of the CSA-IRA Principles in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC).

On 27 September 2016, UPM and FAO signed a Framework Agreement, renewed in subsequent editions, to promote a policy that was defined as follows: “Working on the analysis and formulation of policy proposals and projects for strengthening governance for rural development and food and nutrition security in countries of LA and the Caribbean, the geographic area initially targeted by this project. On behalf of UPM, the Gesplan Group and on behalf of FAO, the Agricultural and Development Economics Division (ESA) and FAO’s Regional Office for LA and the Caribbean (RLC)” [47].

Since 2016, successive Letters of Agreement (LoAs) have been developed, launching new projects—described later in this document—with increasingly complex and ambitious activities based on the annual results achieved. In the terminology of the field of Project Management, this could be synthesized as a system of projects operating as a process, [23] in which the achievements—new ideas—are articulated through new projects, making it, as Negrillo insists, [48] more appropriate to speak of a development process rather than merely development projects.

1.3. Metauniversity in World-Class Universities: Rethinking the Future

Within the context of American World-Class Universities, the concept of the “Metauniversity” emerges as a way of rethinking the future of higher education through the transfer of knowledge among academics, researchers, and society [3,4,48,49,50].

The term “meta” gained significance centuries ago and originates from Hellenic culture. In a certain library, some of Aristotle’s books were shelved behind works on Physics, and the subject matter therein was referred to as “Metaphysics”, meaning “beyond Physics”. From that point on, the prefix “meta” enriched the accompanying concept with its original sense of “beyond.” In 1984, in the context of a research project conducted at the Chair of Physical Planning and Projects at UPM, Ángel Ramos, a prominent figure, incorporated that prefix into the “model” for the regionalization of a territory, titling it “Metamodel for the Regionalization of a Territory,” meaning “beyond” and suggesting that the notion of ‘model’ as an abstraction, when extended with the prefix ‘meta’, leads us to another concept: one that completes and adds to the original, as in a “model of models” [51]. More recently, other authors have applied the term “metamodel” as a structure of entities, associations, and constraints that allow for the representation of conceptual models. [24]

With this meaning and linked to technological change, the term “meta” extends to the university domain, giving rise to the concept of the Metauniversity [3,4,25]. The OpenCourseWare initiative developed in the USA, Asia, and Europe enabled the opening and sharing of intellectual resources and educational materials, promoting a dominant spirit of global cooperation: informing, sharing knowledge, and teaching internationally [3].

Cazorla and De los Ríos [19] emphasizes the fundamental role of the professor as a guide and mentor to students, encouraging them to use, adapt, or expand materials to meet their needs, based on the teaching strategy and local context. Within this new conceptual framework, Costanza et al. [2] note that knowledge generation and resource mobilization will take place through digital platforms for shared information, increasing quality and global access.

Thus, we continue to be enriched by a concept that remains highly relevant in the world’s leading universities: the university as “a relationship between masters and disciples in search of the unum necessarium: knowledge” [19].

Just as it was previously argued that research universities are “more than” simple universities, likewise, the authors of this publication believe that a concept as complex and multifaceted as sustainable development requires an operational structure suited to such a challenge. The experience gained conceptually “through action” invites us to believe that it is indeed possible.

1.4. Objectives of This Research

Within the new context of change at FAO, the approval of the CSA-IRA Principles, and the development of research universities—particularly the role of UPM over a nine-year period—this research is framed around the challenge of rethinking new models that facilitate the articulation of business relationships with the generation of new knowledge, oriented toward policy proposals and project development within the framework of sustainable development.

Based on everything presented so far, and following the development of the framework, the main objective of this research is to demonstrate the Metauniversity as an effective instrument to promote sustainable development through the integration of the CSA-IRA Principles, from the WWP model, and within an international university–business network in Latin America, Spain, and the Caribbean.

The following section presents and justifies the methodological process undertaken.

2. Materials and Methods

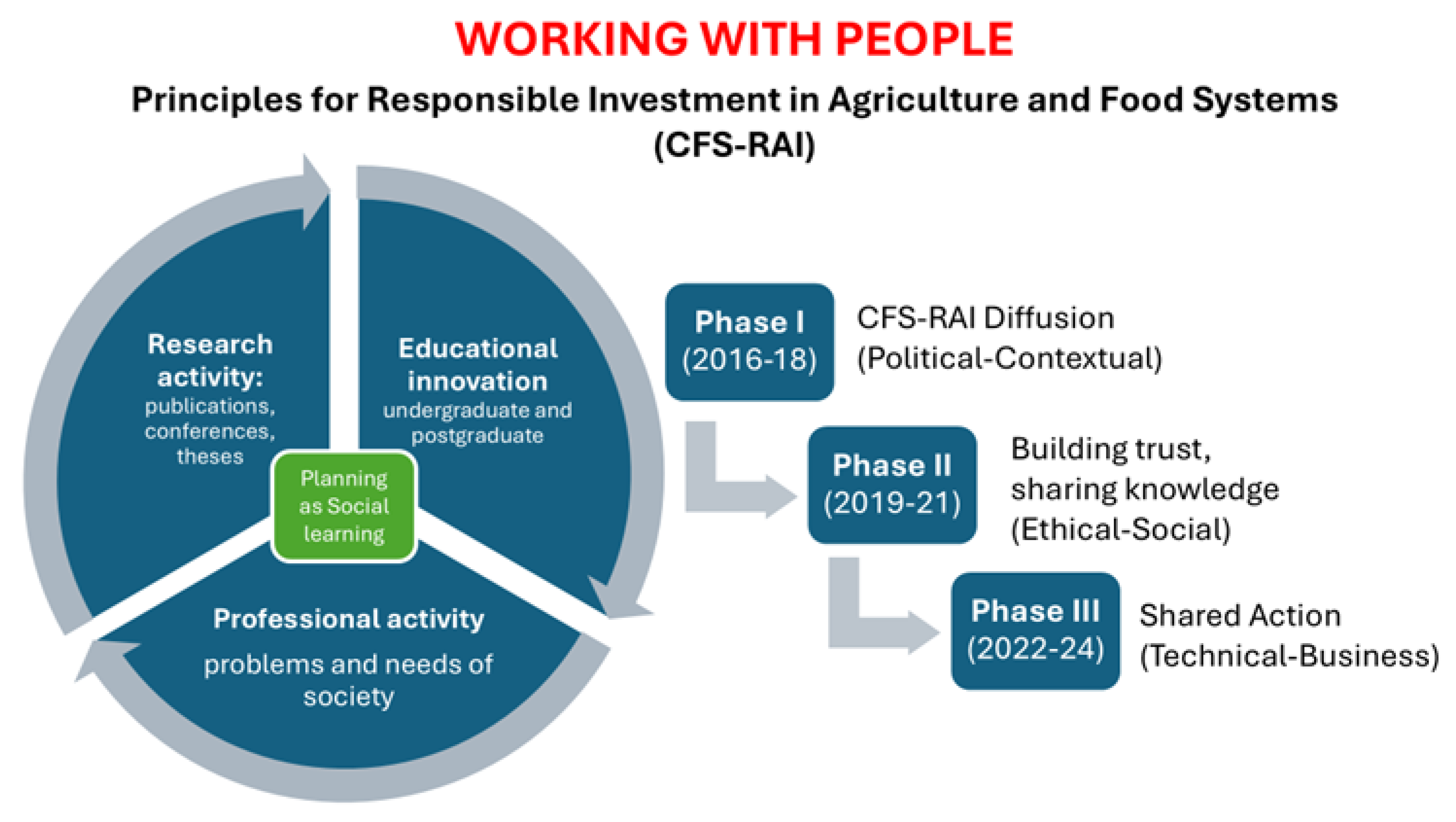

Since 2016, the methodology developed in the successive Letters of Agreement between UPM and FAO has been based on the Working with People model. This WWP model is the result of 25 years of experience by the Gesplan Group in working and publishing in the field of rural development project management in various international contexts. The model is understood as a professional practice developed in cooperation that seeks to connect knowledge and action through joint projects that integrate the learning and values of the people involved.

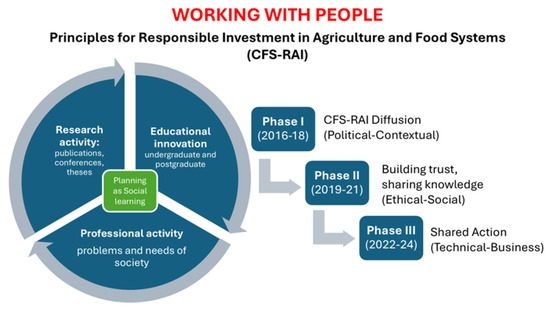

This WWP conceptual framework is synthesized into three components—ethical-social, technical-business, and political-contextual—which interact to reinforce and enhance one another through processes of social learning. Figure 3 summarizes these three dimensions of the WWP model.

Figure 3.

Working with People model [20]. Source: Own elaboration.

The WWP model, [20] in the context of this particular case study —process for the creation of a Metauniversity for Sustainable Development, consolidating a strategic alliance between 46 universities and 52 companies from 12 countries—, is characterized by the following aspects:

- Participatory approach: This involves different actors (universities, companies, civil society) in a joint learning process.

- Social learning: This focuses on generating shared knowledge through interaction among participants.

- Quantitative and qualitative analysis: This presents both descriptive and numerical results of the activities and outcomes of the process.

- Longitudinal case study: This is quite rarely achieved as, in this case, a nine-year continuity allows for an in-depth analysis of its evolution and results.

Based on the premise that “if there are no ideas, there are no projects or plans”, this model, applied to our case study, integrates in its principles the thinking of John Friedmann, a global figure in Planning, particularly through his seminal publication detailed below:

Planning in the Public Domain, where one can extract from “Planning Action” the creative thoughts that ultimately shape a “scientific breakthrough” once, through contrast, something new emerges [29]. In our case, following the emergence of a “new concept” with the CSA-IRA Principles, approved in 2014 by 191 countries around the world, a dissemination project for this concept was proposed in 2016 to a university (UPM), targeting an extensive territorial area: Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC).

The following section describes the phases that make up the model and the work carried out over nine years, in such a way that dissemination evolved into shared knowledge and, in a third stage, into joint actions. Naturally, not all universities or companies have evolved at the same pace, as some have been involved since 2016 while others joined over the subsequent years, the most recent being in 2024. Nevertheless, the body of knowledge that has been developed has enabled these newer institutions to progress more rapidly, for obvious reasons.

2.1. Phases of the Methodological Process

From the political–contextual dimension of the WWP model (Phase I), dissemination actions played a fundamental role in initiating the process and ensuring a level of understanding necessary to guarantee the effectiveness of the subsequent phases. The CSA-IRA Principles require an understanding of contextual and political conditions in order to initiate processes within university–business relationships.

The ethical–social dimension of the WWP model (Phase II) allows for the generation of trust and commitment to advance toward the integration of the CSA-IRA Principles into academic, research, and community engagement programs, thereby fostering shared knowledge.

The technical–business dimension of the model (Phase III) plays an essential role in moving toward “Shared Action” through the development of joint university–business projects, involving stakeholders who have previously been trained and have established mutual trust. These projects would not be possible without having gone through the earlier phases.

2.2. Learning Processes and Scope of Participation

The scope of this research encompasses the nine-year period (2016–2024) of the program, during which the CSA-IRA Principles have been disseminated and integrated into educational programs, applied research, and business engagement—something that was unthinkable just a few years ago—given the challenges multilateral organizations face in reaching that level [29].

From the WWP approach, various actions—such as conferences, workshops, and seminars—were implemented to exchange experiences, generating “living” documents used as “case studies” for the application of the CSA-IRA Principles in education and training efforts across universities, associations, and companies. These were accompanied by well-established methodologies such as project-based learning [19,29,33], question-based learning [28,52,53], and service-learning [54,55].

These joint learning processes help in identifying problems and reflecting on decision-making processes in business, associative, or cooperative environments regarding the Principles for Responsible Investment in Agriculture (IRA) and have been systematized for research and dissemination through a web repository [47].

Over the years, as detailed later in the results section, workshops and training programs have been conducted across various countries in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), fostering collaboration between universities and agro-food companies.

In total, 25 workshops and 36 training programs were carried out, with 11,299 participants, distributed as follows: 441 from companies and associations, 764 from universities (faculty and researchers), 151 from public administrations (national, regional, local), 448 from organized civil society, and 9495 students (8868 undergraduate, 601 postgraduate, and 26 in research).

As of 30 June 2024, the initiative had reached 98 committed entities—52 companies and 46 universities—from 12 countries: Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Paraguay, Ecuador, Peru, Colombia, Venezuela, Mexico, Panama, the Dominican Republic, and Spain.

The following Table 2 quantifies in each of the phases the scope of participation, the objectives and their relationship with the CSA-IRA Principles in each of the phases of the WWP metamodel to evolve towards the creation of a Meta-university oriented to sustainable development [20,30].

Table 2.

Phases of research from Working with People” (WWP) model: Scope of participation, objectives and relationship with CSA-IRA Principles.

Each phase of the WWP model is aligned with specific objectives, concrete activities and outcomes which, in turn, are linked to the CSA-IRA principles from the interconnected dimensions (ethical-social, technical-business and political-contextual) that reinforce each other through social learning processes. These WWP dimensions were developed in three sequential and progressive phases, designed for the dissemination of the conceptual framework—the CFS-IRA Principles—into shared, tangible actions.

The main novelty of the methodology lies in the application of the WWP metamodel as a structured and sequential framework to operationalize the CSA-IRA Principles through an innovative university paradigm: the Metauniversity. Unlike traditional models, the WWP approach is not limited to the simple transfer of knowledge but articulates a development process in three logical and progressive stages. Phase I ensures strategic dissemination so that a complex concept (the CFS-IRA Principles) is understood and contextualized by all actors (contextual type dimension). Phase II of building social capital is crucial, as it recognizes that effective and sustainable collaboration cannot occur without a foundation of trust and mutual commitment (ethical-social dimension of the model). Finally, in Phase III, the action based on trust is built, which allows the implementation of successful technical and business projects (living labs) that would not be viable without the previous phases.

This WWP methodological progression ensures that the Metauniversity is not only a collaborative network, but a social learning ecosystem where research, teaching, and engagement with society are synergistically integrated to address real challenges of sustainable development.

The results of the Metauniversity—with its pillars of research, linkage, teaching, governance and administration—from this nine-year methodological process are shown below.

3. Results

The implementation of the Metauniversity model as an outcome of the FAO-UPM project has produced significant results across multiple dimensions, demonstrating the feasibility and transformative potential of this approach in higher education. The findings are presented according to the methodological dimensions employed, allowing for a comprehensive understanding of the achievements.

The success of the Metauniversity model in creating an international network of universities and companies for sustainable development has been guided by the integration of the three interconnected WWP dimensions [20,30] in its three phases.

The Political-Contextual dimension (Phase I) is crucial to establish the essential framework that guarantees political support, resource mobilization and a collaborative environment. It focuses on diffusion and the ability of actors to build relationships. The Ethical-Social dimension (phase II) its actions are aimed at promoting active participation, developing skills and sharing knowledge. Finally, the Technical-Business dimension (phase III) allows knowledge to be transformed into “Shared Action” with practical actions aimed at sustainable development in the territories.

The results in the process of creation of the Metauniversity are shown, operating under the WWP model, which has demonstrated its viability, by promoting a balance between the three dimensions, to be an instrument for institutional transformation integrating the CFS-RAI Principles.

3.1. Results of the Political–Contextual Dimension (Phase I, 2016–2018): Dissemination

During this initial phase, grounded in the political–contextual dimension of the WWP model, strategic actions were carried out over three years to disseminate the CSA-IRA Principles, establishing the necessary political and contextual foundations to foster a favorable ecosystem. Below are the most notable activities and their specific outcomes.

3.1.1. Activities for the Dissemination of the CSA-IRA Principles

International Multi-stakeholder Workshops on Responsible Investment in Agriculture (2017): Three CSA-IRA high-impact workshops were held in Peru (Lima, 27–28 June 2017), Ecuador (Cuenca, 21–22 September 2017), Colombia (Bogotá 26–27 September 2017), bringing together 195 participants from universities, agrifood companies, associations and public administrations. An additional seminar in Madrid with 65 attendees integrated Spanish actors into the network. The novelty of this approach was the creation of a space for intensive mutual learning, which made it possible to incorporate the productive sector from the beginning and overcome the previous fragmentation of efforts [29].

Facilitator Training Workshop (2018), in the Dominican Republic, 24 professors were trained as multiplying agents of the CSA-IRA principles in their institutions. This strategy ensured local appropriation of knowledge and the sustainability of the model, decentralizing the initiative and guaranteeing its continuity.

3.1.2. Results and Relation to the Principles

The result of this phase was the creation of an initial and committed network of 27 universities in 7 countries, laying the institutional foundations and social capital necessary for the future Meta-university. Specifically, the following instruments were designed for the University:

- (A)

- Methodological Guide “Application of the CSA-IRA Principles in the University Context” (2017): A foundational document translated into two languages (Spanish and English) used as introductory material to present the principles in various academic settings.

- (B)

- Collection of 10 Infographics on the CSA-IRA Principles (2018): Visual materials adapted to facilitate the understanding of each principle with contextualized examples for Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC).

- (C)

- Documentary Video “Investing Responsibly in Agriculture” (2018): A 15 min audiovisual production featuring testimonials from academics and producers on the importance of the principles, used as a didactic resource in the early years.

- (D)

- Colombia Case: In the context of post-conflict Colombia, emphasis was placed on Principles 5 (land tenure) and 10 (impact assessment), in collaboration with the National University of Colombia, adapting materials to this territorial reality.

- (E)

- Mexico Case: In collaboration with the Colegio de Posgraduados, an adapted version of the principles was developed for regions with a strong presence of traditional agriculture, emphasizing Principle 7 (respect for cultural heritage).

The analysis of the political–institutional context initially revealed significant fragmentation in collaboration efforts between universities and businesses in LAC and Spain. However, the results achieved enabled the establishment of effective and lasting cooperation structures during the first phase of the project (2016–2018), including the formation of an initial network of 27 universities in 7 countries, 15 of which committed through an institutional signing event in October 2018, held at the Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, in the presence of a regional FAO representative. As shown later, this network expanded to 46 institutions in 12 countries by June 2024, becoming the backbone of the Metauniversity proposal approved in September 2024.

The creation of institutional collaboration frameworks has been particularly successful, as evidenced by the signing of a formal cooperation agreement and the establishment of shared working protocols thanks to the preparatory efforts described above. A significant milestone was the integration of the CSA-IRA Principles into the institutional policies of participating universities such as Universidad Politécnica Salesiana and Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, demonstrating a tangible commitment to sustainable development.

The results of this Phase I especially relate to the CSA-IRA Principles 9 and 10, focused on governance, to establish the necessary political and governance foundations to foster an ecosystem favorable to university-business cooperation. Initially, a fragmentation in collaboration efforts between universities and companies was detected. Through the workshops and the work with the people, it was possible to build trust among the participants to establish effective and lasting cooperation structures. A fundamental milestone was the creation of the initial network of 27 universities from 7 countries, which became the “backbone” to move towards the future Meta-university. In this process, priority was given to the application of Principle 9, to incorporate governance structures in the collaboration network (universities-companies, public sector) with formal agreements and shared work protocols. In addition, in this phase, the principles were not only disseminated in a generic way, but also adapted to specific territorial realities, to assess and address contextual impacts, in line with Principle 10 [17,21]. The creation of a “Methodological Guide for the Application of the CSA-IRA Principles in the University Context” and the collection of 10 contextualized infographics for LAC, a concrete example, contributed to promoting and materializing principles 9 and 10 [23].

In short, this phase was not limited to a simple dissemination of concepts but actively built the governance structures (P9) and the mechanisms of responsibility and adaptation (P10) that allowed the successful development of the subsequent phases [14]. By creating a formal network and adapting content to local contexts, this stage laid the institutional and political foundations indispensable for transforming fragmented collaboration into a robust and functional ecosystem geared towards sustainable development [13].

3.2. Results of the Ethical–Social Dimension (Phase II, 2019–2021): Building Trust and Shared Knowledge

The construction of social capital and trust among participants has been one of the project’s most remarkable achievements. It is important to note that this period was marked by the COVID-19 pandemic, which prevented in-person meetings that had previously been the usual method of collaboration. This second phase, grounded in the ethical–social dimension of the WWP model, marked a qualitative leap forward, reflected in several emblematic activities.

3.2.1. Trust-Building and Knowledge-Sharing Activities

The activities developed show an innovative character in terms of their orientation towards building trust and the creation of shared knowledge between traditionally fragmented sectors. The virtual seminars organized during the pandemic were not only a mechanism for academic continuity but also provided a space for horizontal interaction between universities and business actors, where explicit commitments were generated to promote the CSA-IRA principles. This aspect is especially relevant, since inter-institutional trust was based on the joint deliberation of challenges and solutions in a context of crisis. Two Seminars hosted jointly by UPM, Universidad Politécnica Salesiana and the Executive Leadership Program of Universidad de Piura in 2020, during the pandemic. These online events gathered 317 faculty and university administrators and 70 business leaders and association executives who began committing to promote the CSA-IRA Principles in their sectors.

Similarly, legislative research in the Latin American and Caribbean region provided a common ground of normative reference, contributing to a shared language that links academia with legal and political practice. Research on Legislation in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) to identify laws that, even if not explicitly, reflected the CSA-IRA Principles: This effort led to the identification of three relevant legal cases in Peru, Colombia and Chile [47].

The elaboration of case studies, based on diverse national realities, functioned as a pedagogical and scientific resource to share transferable learning and strengthen epistemological confidence in the validity of the principles. Preparation of 5 completed Case Studies, which—at FAO’s suggestion—were aligned with the CSA-IRA Principles and proposed as research materials. These cases came from Argentina, Peru, Ecuador, Mexico, and Colombia.

Finally, curricular integration at multiple educational levels shows a long-term commitment to institutionalizing collective knowledge, promoting not only the transmission of content, but also a culture of cooperation between students, teachers, and sectoral leaders. Following the commitments made by universities in 2018, the CSA-IRA Principles were integrated into academic programs (undergraduate, postgraduate, and research) at each institution, reaching more than 9000 students across the 15 participating universities.

3.2.2. Results and Relation to the Principles

The results of Phase II (2019–2021) allowed the building of trust and shared knowledge around the CSA-IRA Principles related to the social dimension (P3, promote gender equality and the empowerment of women; P4 (Strengthen youth participation and empowerment).

In this Phase II, an integration of the CSA-IRA principles was achieved in the undergraduate, graduate and research programs in 15 universities, laying the foundations to strengthen youth participation and empowerment (P4) to educate future generations of professionals in these principles. The seminars brought together 317 university professors and 70 business leaders, who committed to promoting gender equality (P3) and youth empowerment (P4) in their respective sectors. The production of three master’s theses (carried out at the Universidad Nacional de La Plata, Universidad Politécnica Salesiana and Universidad Politécnica de Madrid) and two doctoral dissertations based on research developed in previous years, allowed the generation of knowledge from research on the social aspects of responsible investment [19,20,23,28].

In relation to the economic dimension (prosperity), during Phase II, and at the suggestion of FAO, five case studies were prepared (in Argentina, Peru, Ecuador, Mexico and Colombia) from research aligned with the principles CSA-IRA P1 (Contribute to food security and nutrition), P2 (Contribute to sustainable and inclusive economic development) and P7 (Respect cultural heritage and traditional knowledge). These joint investigations [16,17,19,23,25] also enabled the building of trust and shared knowledge, meaningfully addressed both social (P3, P4) and economic (P1, P2, P7) principles, and paved the way for the “Shared Action” of Phase III.

3.3. Results of the Technical–Business Dimension (Phase III, 2022–2024): Shared Action

The third phase of this research–action process represented the culmination of a journey that led to the maturity necessary to establish a Metauniversity through joint projects. It was characterized by the transformation of shared knowledge into practical solutions for real challenges in sustainable development, encompassing teaching, research, societal engagement, administrative structuring, and strategic leadership as elements that laid the groundwork for the phase to be launched in September 2024: the creation of a Metauniversity for sustainable development [56].

3.3.1. Shared Actions in the Field of Postgraduate Studies

In this third phase, the above results allowed an innovative approach aimed at integral sustainability and institutional responsibility, carrying out various pioneering training actions in the field of higher education and executive training. These initiatives, endorsed by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), constitute a milestone in the international articulation of postgraduate programs around the CSA-IRA Principles [57], with special impact in Latin America, the Caribbean and Spain. These actions in the field of postgraduate studies are summarized below.

- (A)

- First international postgraduate program on CSA-IRA Principles, approved by FAO and aimed at faculty and researchers from universities in Latin America, the Caribbean, and Spain. It lasted two months, included 40 h of instruction, and had 65 participants in its first edition. The second and third editions, held in 2023 and 2024, respectively, were extended to four months and involved 135 participants from 23 universities across 9 countries.

- (B)

- First international program for business executives, association leaders, and cooperatives on the CSA-IRA Principles, with a duration of two months and 40 h, and a total of 69 participants. The second and third editions maintained the same format, reaching 113 participants from 10 countries.

- (C)

- Two executive training seminars on the IRA Principles and two teacher training seminars, organized in-person over two days in Lima (UCSS, PAD) and Santo Domingo (PUCMM), and held online for participants from other countries, with a total of 198 attendees.

- (D)

- Certification programs for professors and business executives interested in becoming experts and future instructors in CSA-IRA seminars. Between 2023 and 2024, a total of 203 professors and business leaders from 45 university and business institutions across 12 countries were certified. These individuals went on to form the academic faculty of what would become the future Metauniversity.

These actions at the level of the postgraduate degree studies represent an educational innovation in the field of sustainability and institutional responsibility, by integrating academic, executive and certifying training around a common conceptual framework. The results achieved—more than 500 certified participants from more than 20 countries and the formation of an inter-university network—show the consolidation of a training ecosystem of international scope and the projection of the CSA-IRA Principles as a benchmark in education for sustainable development and good institutional governance.

3.3.2. Shared Actions in the Field of Societal Engagement

The actions developed in this phase constitute a novel contribution in the field of university-business cooperation and in the construction of international frameworks for research and training in sustainability.

- (A)

- Second Meeting of the Network of Universities/Companies Committed to the CSA-IRA Principles: Held on 70December 2022, in Santo Domingo, hosted by the Pontificia Universidad Católica Madre y Maestra (PUCMM) in collaboration with UPM. Twenty universities from the network participated, along with three additional universities that joined during this meeting. University representatives formally endorsed the commitment of the 27 companies, associations, and cooperatives affiliated with the network.

- (B)

- Three Living Labs as joint university–business initiatives were launched in Cayambe (Ecuador), Santiago Rodríguez (Dominican Republic), and Mantaro (Peru). These practical implementations of ongoing efforts were documented as case studies following FAO’s format, under the term living labs, coined by FAO. Detailed information is available [47].

- (C)

- As a result of a training plan in Mexico with researchers from the Colegio de Posgraduados (CP), the cooperative Sabores de Calpan, and entrepreneurs who founded the company Campo de Lima for marketing a new variety of corn, a new living lab was launched in June 2024, still in an early stage compared to the three previously described.

- (D)

- Third Meeting in Santo Domingo, September 2024, with direct or delegated participation from nearly all network universities and companies, to discuss the creation of the Metauniversity: This new structure would replace the existing network with a higher-level research/teaching/societal engagement approach. The proposal was unanimously approved. The development of the Metauniversity is addressed later in this article.

The results obtained—the expansion of the network, the formalization of inter-institutional commitments, the creation of living laboratories, and the gestation of a Meta-University—demonstrate the capacity of the CSA-IRA Principles to generate academic, business, and social innovations. These actions not only consolidate an international community of practice but also constitute a pioneering platform for collective learning and institutional transformation in favor of integral sustainability.

3.3.3. Shared Actions in the Field of Research Serving Society

A central aspect in the consolidation of the CSA-IRA Principles has been the generation of research with academic and social impact. Between 2022 and 2025, the following significant advances were achieved that demonstrate the maturity of the scientific ecosystem linked to the network.

- (A)

- Research articles published in impact journals (9): Peru (3), Ecuador (2), Colombia (1), Guatemala (1), Ethiopia (1), and Spain (1).

- (B)

- Master’s theses (4) completed in Colombia (2), Argentina (1), and Spain (1).

- (C)

- Doctoral dissertation based on research conducted in Guatemala and Colombia, with related articles published in JCR Q1 journals. Four doctoral dissertations defended in the first seven months of 2025 by researchers from universities linked to the now-established Metauniversity (UPS, UCSS, and UNMSM), stemming from three prior research projects focused on the IRA Principles: Ecuador (UPS, UTPL) and Peru (UCSS, UNMSM).

- (D)

- Creation of a repository, initiated by the FAO and officially presented at the Third Meeting, as a testament to nine years of work. Key materials were grouped as follows: Doctoral dissertations (3), Master’s theses (12), JCR papers (16), Conference papers (12), Research project case studies (18), Teaching cases for business leaders (50).

The volume and diversity of scientific production achieved in this period shows the consolidation of research around the CSA-IRA Principles as an emerging field of international relevance. The combination of publications in impact journals, postgraduate theses, doctoral projects and a knowledge repository validated by the FAO demonstrates the model’s ability to articulate academic research with advanced training and the generation of public knowledge goods at the service of society.

3.4. Global Impacts of the 2016–2024 Period Not Covered in Previous Sections

A particularly significant result of this cycle has been the strengthening of the links between academia and society. Over nine years, 25 workshops were organized that facilitated direct dialogue between academics, entrepreneurs and social actors, configuring spaces for co-creation and mutual learning that go beyond traditional models of unidirectional knowledge transfer. This interaction resulted in the following:

- (A)

- Applied research projects. Implementation of 18 applied research projects addressing specific challenges of sustainable development in various regional contexts. These projects demonstrate the model’s capacity to produce practical solutions to complex problems.

- (B)

- Inclusive collaboration network. Another outstanding contribution was the creation of a multi-stakeholder network that is not limited to universities and companies but also incorporates 448 representatives of organized civil society. This breadth reinforces the participatory and inclusive nature of the model, which differentiates it from international experiences focused exclusively on academic institutions.

- (C)

- Quantitative results. The scope of the program can be measured in the more than 11,299 participants directly involved: 441 business professionals, 764 university professors and directors, 151 representatives of the public administration, 8868 undergraduate students, 661 graduate students and 26 doctoral students. At the same time, academic production reached significant levels: 16 articles in high-impact journals, 12 master’s theses and 7 doctoral dissertations (of which four were defended in the first months of 2025).

These indicators not only show the consolidation of a critical mass of research and advanced training, but also the capacity of the model to generate relevant and socially applicable scientific knowledge. Its novelty lies in the balanced integration of academia, business and civil society, which positions it as a benchmark in the construction of higher education models aimed at sustainable development and the strengthening of university-society interaction. Table 3 summarize the global impacts for each phase.

Table 3.

Global impacts of the 2016–2024 period.

These results clearly demonstrate that the Metauniversity proposal presented in the following section is built upon foundational elements developed over time through the university–business network. This network holds strong potential to undertake new scientific, educational, and societal engagement ventures of a different order.

3.5. A Metauniversity for Sustainable Development

Such a proposal must be grounded in an established knowledge base, which is outlined below. It is evident that the concept of sustainable development does not permeate all areas of academic knowledge taught at universities, such as fields like the exact sciences, history, philology, or computer science. However, it is equally valid to argue that many other disciplines—particularly those related to economic, social, business, and environmental sciences, as well as certain engineering fields—are deeply affected by the overarching concept of sustainable development.

Thus, this transversal knowledge could greatly enhance the preparation of future professionals, enriching them with multidisciplinary and multicultural perspectives from countries such as those in Latin America, the Caribbean, and Spain. The results previously outlined enable the conceptualization and design of a Metauniversity proposal framed within sustainable development. It is oriented toward “working on policy and project proposals to strengthen governance for rural development and food and nutritional security”, [31] with a more suitable structure as envisioned by the authors, based on the outcomes achieved.

This Metauniversity model, emerging from joint work since 2016 and rooted in the previously described conceptual framework, originates within the GESPLAN Research Group at UPM [31]. However, it comprises professors and senior academics from other Latin American and Caribbean universities, as well as their collaborations with businesses, associations, and cooperatives spaces, where experienced professionals collectively embark on this intellectual and practical journey.

Although this Metauniversity vision integrates technology and many aspects of the European educational model, it is based on the following key elements according to Cazorla & De los Ríos [56]:

- The role of faculty as guides, coordinators, and project leaders, responsible for educational quality, grounded in competencies and the CSA-IRA Principles aligned with applied methodologies.

- A strong ethical commitment in teaching and governance, centered on educational values derived from the CSA-IRA Principles.

- A shared conceptual foundation based on the fields of Project Studies and Planning, fostering project-based learning as a starting point for the integration of CSA-IRA Principles.

- A unified learning framework that incorporates diverse educational components from participating universities, contributing to the richness of the model.

- A degree of curricular homogeneity built around CSA-IRA Principles across interdisciplinary undergraduate and postgraduate programs, designed to address real-world problems and needs.

- “Living labs” in ongoing construction and evolution, built on shared experiences, facilitating research, education, and societal engagement.

- Technological tools to share knowledge and experience and to support distance learning (e-learning), combined with competency-based in-person training.

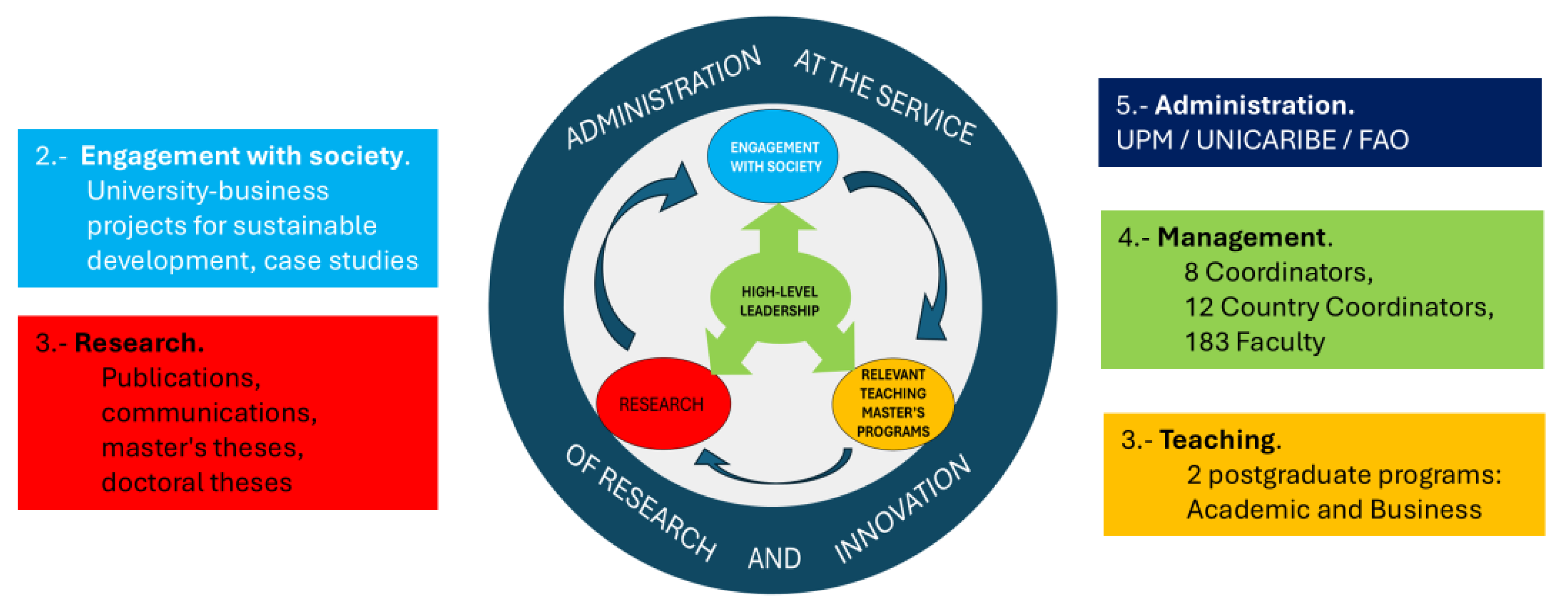

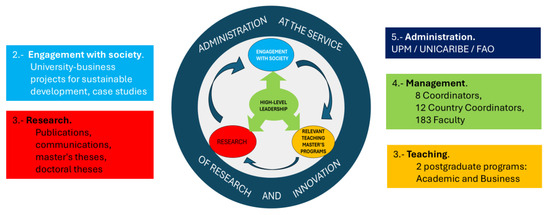

Figure 4 summarizes components and subcomponents of this Metauniversity, drawing from the previously explained research university model, and representing an integrated framework. The Metauniversity represents an innovative higher education paradigm, integrating research, teaching, societal engagement, and governance to address global sustainability challenges.

Figure 4.

Characteristics of the Metauniversity. Source: Own elaboration.

Research: A central digital repository, the “crown jewel” of the network’s digital identity [19], currently hosts 111 published documents and ongoing works. By centralizing outputs from 46 universities, the repository strengthens collaboration and evidence-based approaches critical for sustainable development.

Societal Engagement: Case studies developed by 117 certified faculty members provide diverse real-world scenarios from multiple ecosystems. This approach enhances academia–society interactions and supports applied learning aligned with sustainability goals.

Teaching: The Metauniversity has launched postgraduate programs integrating CSA-IRA Principles and Artificial Intelligence, targeting leaders of agrifood cooperatives across Latin America and the Caribbean. These programs cultivate skills for sustainable food systems and leadership in complex socio-environmental contexts.

High-Level Governance: A leadership team of 13 senior professionals from six countries, supported by 20 PhD coordinators across 12 nations, ensures strategic oversight. Administrative coordination by UPM, UNICARIBE University, and PAD enables efficient management of a complex transnational network.

Metauniversity Administration: UPM leads the administrative coordination, supported by UNICARIBE University and PAD (School of Government at the University of Piura) for the private agrifood sector. This was likely the first key success factor of the initiative, enabling a highly effective management model for a complex structure with first-rate online coordination.

4. Discussion

The results obtained over the nine uninterrupted years of development and structuring of the program validate the Metauniversity proposal and reveal significant patterns that deserve analysis: both in terms of achievements and challenges. This discussion is organized around the most relevant aspects, considering their theoretical and practical implications for the future of higher education.

4.1. Transformation of the University Model

The experience gained through the FAO–UPM program demonstrates that the transformation of the traditional university model into a more collaborative and flexible structure is not only possible but necessary in the face of global and complex challenges—especially those of a territorial nature—where traditional university collaboration proves limited due to a lack of institutional commitment.

The success of building a network of 46 universities and 52 companies suggests there is substantial willingness within the academic and business sectors to adopt new paradigms of collaboration. This finding aligns with Vest’s [3] observations on the emergence of new forms of university organization in response to global challenges.

However, it is important to note that such transformation is not without complexity. Balancing rigorous academic standards while promoting innovation and flexibility requires a delicate balance. The project results suggest that the Metauniversity model offers an effective framework to manage this tension, allowing traditional academic excellence to coexist with more agile and collaborative modes of knowledge creation [56].

4.2. Social Capital and Collaboration Networks

A particularly revealing aspect of the results is the fundamental role of social capital in the model’s success. Building trust-based relationships among institutions and across sectors proved to be a critical factor for the sustainability of the initiatives. Several years of inter-university work were needed to strengthen ties, engage the productive sector, and develop dynamic, practical training systems. This observation reinforces the arguments [1] regarding the importance of collaboration networks in contemporary higher education. The evolution of these networks over time suggests that trust-building is a long-term process requiring sustained commitment. The first two years of the program, focused on the political–contextual dimension, were essential for laying the groundwork of trust that enabled the later development of more ambitious initiatives.

4.3. Innovation in Educational Practice

The results related to innovation in educational practice deserve special attention. The creation of joint academic programs and the implementation of new teaching–learning methodologies have shown that the Metauniversity model can drive significant transformations in how higher education is delivered. The active participation of 9495 students in various programs suggests strong student acceptance of these new approaches.

The effective integration of digital technologies and participatory methodologies has been key to these achievements. However, it must be acknowledged that implementing these innovations required considerable effort in terms of faculty training and institutional adaptation. The Metauniversity’s first two programs have already fostered innovation, especially in terms of didactic knowledge, focusing on two key areas: question-based learning methodologies and the incorporation of Artificial Intelligence in rural settings as an ambitious challenge in the LAC region.

4.4. Sustainability and Scalability of the Model

The long-term sustainability of the Metauniversity model emerges as a crucial topic for discussion. The results suggest that creating shared value between universities and companies can provide a solid foundation for both financial and operational sustainability. The active participation of 52 companies in the project indicates recognition of the value this kind of collaboration can generate for the productive sector.

The Metauniversity model represents a flexible and inclusive learning ecosystem that integrates emerging technologies and educational innovation approaches based on global collaboration and sustainable development. The conceptual framework of the Metauniversity is highly adaptable, which allows its effective extension to other fields and productive sectors, including industry, through a dual application: technological innovation and the structuring of collaborative networks. Multisectoral collaboration and the creation of shared value (WWP model) facilitates the integration of academia, business and civil society, allowing its possible application in any sector linked to sustainable development, as well as in areas such as health, education, technological innovation, energy and urban management, promoting comprehensive solutions with social, environmental and economic impact.

This scalability of the model to other sectors is based on its dual application from: (a) the transfer of immersive technologies for practical training and simulation of critical industrial processes; and (b) the use of a proven methodological framework (WWP) to build sustainable collaborative networks that generate shared economic value and practical solutions, essential for governance and innovation in the productive sector. However, the model’s scalability presents significant challenges. The network’s expansion from 27 to 46 universities during the project demonstrates that growth is possible, but it requires careful management of resources and institutional relationships. The results indicate that expansion must be step by step and accompanied by a proportional strengthening of coordination and support structures.

4.5. Implications for Sustainable Development

The contribution of a Metauniversity to sustainable development deserves special consideration. The results demonstrate that integrating the CSA-IRA Principles into academic and research activities can generate tangible impacts in the form of practical solutions to sustainability challenges. The production of 111 research documents and implementation of 33 applied projects illustrate the model’s capacity to generate relevant and applicable knowledge.

The nine-year experience validates the use of the WWP model, structured in political-contextual, ethical-social and technical-business dimensions, as an effective framework to guide institutional transformation and the generation of knowledge oriented towards practical solutions. The development of applied projects and case studies shows the ability to produce concrete solutions to sustainability problems in real contexts.

A particularly revealing finding consistent with other research [49,50] is the critical role of social capital and trust for long-term success. The sustained construction of relationships of trust between institutions and productive sectors was a critical factor for the sustainability of the initiatives developed under the CSA-IRA principles.

However, it is important to recognize that measuring real impact in terms of sustainable development poses significant methodological challenges. The results from the project suggest the need to develop more robust frameworks to evaluate and document these impacts over the long term.

In summary, the Metauniversity, driven by the CSA-IRA principles from the WWP model, acts as an engine of sustainable development by fostering cross-sectoral collaboration and producing applicable solutions, although its long-term impact requires overcoming challenges in rigorous measurement and documentation.

5. Conclusions

This research has shown that the Metauniversity model represents a significant evolution in the conceptualization and operation of higher education, particularly in its ability to address sustainable development challenges. Through a detailed analysis of the FAO–UPM program (2016–2024) [57], this study provides substantial evidence of the viability and effectiveness of a more integrated and collaborative approach to higher education. Cazorla & De los Ríos [56] elaborate on this approach in a communication presented at a recent international congress.

The successful implementation of a network comprising 46 universities and 52 companies across 12 countries demonstrates that it is possible to overcome the traditional limitations of university structures and create more dynamic and adaptable systems. The WWP model, with its three fundamental dimensions—political–contextual, ethical–social, and technical–business—has provided an effective framework to guide this transformation.

A particularly significant finding has been the importance of the gradual construction of trust and social capital among participating institutions [57]. The program’s progression through its three phases has shown that effective institutional transformation requires a careful balance between innovation and respect for academic traditions and values. The active participation of more than 11,299 individuals across various components of the program over nine years reflects the model’s potential to generate meaningful impact within the academic community and beyond.

The integration of the CSA-IRA Principles [58] into the institutional fabric of participating universities represents a major step toward aligning higher education with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The development of 18 applied research projects and 50 business-oriented case studies demonstrates that the model can produce not only theoretical knowledge but also practical solutions to real-world sustainability challenges. In conclusion, the Metauniversity exemplifies a scalable and replicable model that aligns higher education with the SDGs, particularly quality education (SDG 4), responsible production (SDG 12), and partnerships for the goals (SDG 17), offering a viable framework for institutional transformation aligned with sustainable development. Its success in building effective collaborative networks and generating tangible impacts suggests that this model could serve as a valuable response to the challenges facing higher education in the 21st century. The results documented in this study provide a solid foundation for future implementation and adaptation of the model in diverse global contexts.

Experience also shows that the Metauniversity faces significant limitations, starting with the challenge of assessing the long-term impact on a scarcely explored field of study such as the CSA-IRA Principles. At the operational level, the model also faces the lack of trained human resources in this field and who are the basis for the sustainability of the initiatives. The governance of the Metauniversidad network must also resolve outstanding issues of intellectual property of shared content and the transfer of international credits.

Future research directions focus on expanding the Metauniversity model and the framework of the CSA-IRA Principles in new global contexts. Over time, the meta-university must develop more robust frameworks to assess and document the real impact and long-term sustainability of projects in new contexts. Another future direction is technological innovation, which includes research on the incorporation of Artificial Intelligence in training processes to improve the governance and operational efficiency of managers and professionals of institutions.

Author Contributions

Methodology, C.L.; Validation, A.C. (Adhemir Cáceres); Investigation, A.C. (Adolfo Cazorla); Writing—original draft, A.C. (Adolfo Cazorla). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the GESPLAN research group and the Metaniversity member´s, whose collaboration and contributions were essential to the development of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- San Martín, F.; Cazorla, A. Buen Gobierno en las Universidades de Investigación en un Entorno Digital Global; Fondo Editorial de la UNMSM: Lima, Peru, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Costanza, R.; Kubiszewski, I.; Kompas, T.; Sutton, P.C. A global metauniversity to lead by design to a sustainable well-being future. Front. Sustain. 2021, 2, 653721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vest, C.M. The Emerging Meta University. In Part III Global Strategies for Emerging Universities; 2008; Volume 217. [Google Scholar]

- Couturier, L. The American Research University from World War II to World Wide Web: Governments, the Private Sector, and the Emerging Meta-University; The Review of Higher Education; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2008; Volume 1, pp. 356–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manapbayeva, Z.; Daineko, Y. Metauniversity as a Tool for Achieving Multiple Sustainable Development Goals. In Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on Application of Immersive Technology, Almaty, Kazakhstan, 5 March 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Turzhanov, U.; Daineko, Y.; Tsoy, D.; Ipalakova, M. Metauniversity as a Tool for Inclusive Learning. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 251, 550–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R.; Barreiro-Gen, M.; Lozano, F.J.; Sammalisto, K. Teaching sustainability in European higher education institutions: Assessing the connections between competences and pedagogical approaches. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiek, A.; Withycombe, L.; Redman, C.L. Key competencies in sustainability: A reference framework for academic program development. Sustain. Sci. 2011, 6, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundiers, K.; Wiek, A.; Redman, C.L. Real-world learning opportunities in sustainability—Concept, competencies, and implementation. Int. J. Sust. Higher Educ. 2010, 11, 308–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Requelme, N.; Afonso, A. The Principles for Responsible Investment in Agriculture (CFS-RAI) and SDG 2 and SDG 12 in Agricultural Policies: Case Study of Ecuador. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvis, B.; Mao, Y.; Robinson, D. Three Pillars of Sustainability: In Search of Conceptual Origins. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanović, I.; Ateljević, J.; Stević, R.S. Good governance as a tool of sustainable development. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 5, 558–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De los Ríos-Carmenado, I.; Mereles, M.L.A.; Deza, X.N.D.L. Connecting Sustainable Rural Development Projects and Principles of Responsible Investment in Agriculture and Food Systems from WWP Model: Lessons from Case Studies in Seven Countries. Preprints 2025, 2025090058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, A.; Velasquez-Fernandez, A.; Rodriguez-Vasquez, M.I.; Cuervo-Guerrero, G. Territorial Analysis Through the Integration of CFS-RAI Principles and the Working with People Model: An Application in the Andean Highlands of Peru. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta Mereles, M.L.; Mur Nuño, C.; Stratta Fernández, R.R.; Chenet, M.E. Good Practices of Food Banks in Spain: Contribution to Sustainable Development from the CFS-RAI Principles. Sustainability 2025, 17, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cachipuendo, C.; Requelme, N.; Sandoval, C.; Afonso, A. Sustainable Rural Development Based on CFS-RAI Principles in the Production of Healthy Food: The Case of the Kayambi People (Ecuador). Sustainability 2025, 17, 2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regalado-López, J.; Maimone-Celorio, J.A.; Pérez-Ramírez, N. Strengthening of the Rural Community and Corn Food Chain Through the Application of the WWP Model and the Integration of CFS-RAI Principles in Puebla, México. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]