1. Introduction

The concept of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) was first introduced in 2004 through the

Who Cares Wins report, jointly published by the United Nations, the International Finance Corporation, and the Global Compact [

1]. This report advocated for financial institutions to pay more attention to environmental, social, and governance factors in their investment decisions. With the United Nations’ publication of the

Principles for Responsible Investment in 2006 and the adoption of the

Paris Agreement in 2015, ESG evolved from a conceptual idea to measurable standards [

2]. The establishment of organizations such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) [

3], the Climate Disclosure Standards Board (CDSB) [

4], the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) [

5], and the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) [

6] has provided technical support for the standardization and localization of ESG reporting. Today, ESG sustainability reports have become a critical measure of corporate development quality and have a profound impact on investor decision-making.

In 2020, China proposed the “dual carbon goals” (carbon peak and carbon neutrality), and in the 14th Five-Year Plan and the Vision 2035 outline issued in 2021, it clearly called for advancing the construction of an ecological civilization [

7]. Promoting green and sustainable economic and social development is a key step in China’s transition from high-speed growth to high-quality development. Against this backdrop, the importance of ESG information disclosure has been increasingly emphasized by financial and regulatory institutions. As the micro-foundation and backbone of China’s “dual carbon goals,” how enterprises can drive green transformation and enhance international competitiveness under the guidance of ESG principles holds significant practical importance.

In 2015, the

Government Work Report introduced the “Made in China 2025” initiative, outlining the goal of transforming China from a manufacturing powerhouse into a manufacturing stronghold [

8]. As the world’s largest exporter, China’s manufacturing exports accounted for a significant share of global exports, reaching 13.7% in 2016 [

9]. The rapid development of China’s manufacturing sector has been driven by advantages in labor and traditional resources. However, with the implementation of the dual carbon goals and the advancement of high-level opening up, China’s manufacturing industry faces the gradual erosion of its traditional resource advantages and increasingly complex international trade dynamics. Therefore, improving the export competitiveness of Chinese manufacturing enterprises and achieving high-quality development has become a critical task for China’s economic transformation. How ESG performance can help manufacturing enterprises overcome current development challenges has become a focal point of research.

Export competitiveness refers to a firm’s ability to enhance its position in international markets by improving the quality, technological sophistication, and value of its exported products, thereby sustaining or expanding its global market share. It is not only influenced by traditional macroeconomic factors such as exchange rate policies, trade costs, and factor endowments, but also by firm-level capabilities related to technological upgrading, financing, and productivity. Currently, research on manufacturing export competitiveness largely focuses on macro-level factors such as environmental regulations [

10], export costs [

11], factor endowments [

12], and foreign direct investment (FDI) [

13]. However, micro-level studies that explore the impact of ESG performance on the export competitiveness of manufacturing enterprises remain limited. Existing research often concentrates on single dimensions, such as the impact of corporate financing [

14], social responsibility [

15], and governance on exports [

16], but systematic research on how overall ESG performance influences export competitiveness is sparse and often yields inconsistent conclusions. Some studies suggest that investments in environmental, social, or governance practices may increase operational costs and suppress exports [

17], while others argue that good ESG performance enhances a firm’s reputation and development quality, which can, in turn, boost exports [

18].

This paper explores whether and how ESG performance impacts the export competitiveness of manufacturing enterprises. By analyzing the relationship and mechanisms between ESG performance and export competitiveness, the study aims to further clarify the practical significance of ESG performance for manufacturing firms’ international competitiveness. Using data from Chinese A-share listed manufacturing companies from 2011 to 2021, combined with the China Customs database, this paper investigates how ESG performance can promote export competitiveness through reducing financing constraints and enhancing risk-taking capacity.

The paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 reviews existing research on ESG performance and its impact on corporate development, with a focus on export competitiveness in manufacturing.

Section 3 presents the theoretical framework and develops the research hypotheses.

Section 4 outlines the research design, including data collection, sample selection, and variable measurement.

Section 5 presents the empirical analysis and tests the hypotheses.

Section 6 examines the moderating effects of business environment and institutional investor ownership.

Section 7 concludes with the study’s implications, limitations, and future research suggestions.

2. Literature Review

As the global concept of sustainable development continues to deepen and be practiced, research on ESG performance has gradually become an important topic across various fields worldwide. ESG performance is widely regarded as one of the key factors driving high-quality corporate development, especially for export-oriented enterprises. This is particularly relevant in the context of China, where ESG practices provide feasible pathways and support for improving export competitiveness. A review of the existing literature reveals that studies on the impact of ESG performance on business development primarily focus on the following areas: capital costs, corporate innovation, auditing, corporate performance, and stock market performance.

To begin with, from the perspective of capital acquisition costs, investors tend to reduce equity financing costs for firms with higher ESG ratings due to their preference for such companies [

19]. In contrast, firms with lower ESG ratings, which typically have a narrower investor base, experience an increase in their equity financing costs [

20]. Additionally, companies with higher ESG ratings tend to have a lower perceived risk compared to those with poorer ratings [

21]. These companies also enjoy higher creditworthiness, which enables them to secure debt financing at a lower cost [

22].

In addition, the positive signals conveyed by a company’s ESG performance can effectively mitigate information asymmetry, thereby improving the efficiency of resource acquisition and allocation, which further enhances the company’s innovation performance [

23]. Additionally, ESG performance plays a positive moderating role in the relationship between Research and Development (R&D) investment and green innovation performance, with strong ESG performance significantly boosting green innovation within firms [

24]. Li et al. (2023) have shown that companies can enhance their innovation performance by investing in ESG practices, particularly in improving both the quantity and quality of innovation [

25].

Turning to auditing, Burke et al. (2019) have explored the impact of ESG performance on corporate audits, suggesting that when a company’s ESG performance is poor, auditors need to spend more time on financial audits to address the anticipated risks [

26]. This subpar ESG performance also leads to higher audit fees due to the increased scrutiny required.

Finally, studies examining corporate performance and stock market impacts have found that companies with higher ESG ratings tend to have better corporate performance and higher corporate value compared to those with lower ESG ratings. Both overall ESG scores and the individual components of ESG significantly enhance corporate performance [

27]. Additionally, ESG performance has a notable impact on stock prices, with companies rated higher in ESG exhibiting lower stock price volatility and better market performance. This phenomenon is especially pronounced in non-state-owned enterprises [

28,

29,

30]. In summary, research exploring the impact of ESG performance on export competitiveness remains relatively limited.

In a related vein, another key focus of this study is the exploration of the factors affecting export competitiveness. A review of the literature reveals that factors such as export costs [

31], vertical division of labor [

32], supply chain conditions [

33], and trade dynamics [

34] all influence a company’s export performance. However, studies on export competitiveness primarily focus on macro-level factors such as industry or national/regional characteristics. The development of processing trade in a country brings technological spillovers and demonstration effects, driving the progress of product complexity and further enhancing the country’s export competitiveness. Additionally, the development of infrastructure in a region or country has a positive impact on its export competitiveness [

35,

36]. At the industry level, Luo and Qi (2016) and others have suggested that the foreign investment share within an industry positively impacts the export complexity of that industry in the host country [

37], particularly with a more significant effect from FDI from OECD countries on product quality [

38]. From the perspective of factor endowments, Hausmann et al. (2007) proposed that human capital and labor force size are major factors influencing changes in the technological complexity of industry exports [

39].

Existing research on export competitiveness has yielded rich results at the macro level, focusing on national, industry, and regional factors. These studies have also explored the impact of corporate export costs and trade conditions on export performance. However, there is limited research on the impact of ESG performance on corporate export competitiveness. The existing studies primarily focus on the effect of individual ESG factors on exports, and their conclusions are inconsistent. From the perspective of environmental regulation, some studies argue that environmental regulations guide companies to transform their product structure, thereby improving product quality and enhancing export performance [

40,

41,

42]. On the other hand, some scholars contend that environmental regulations increase operational costs, which can lead to a decline in product quality and suppress export performance [

43,

44]. From the perspective of corporate social responsibility (CSR), some studies suggest that fulfilling CSR or attracting high-level foreign talent helps improve export performance [

45]. In contrast, other studies argue that focusing on CSR can reduce export capacity and have a negative impact on export competitiveness [

46].

From the existing literature, it is evident that research on ESG performance’s impact on export competitiveness is fragmented, and the conclusions are inconsistent. Some studies focus on individual dimensions, such as CSR, corporate governance, or environmental policies, without examining the systemic mechanisms of overall ESG performance. Therefore, this paper uses Chinese manufacturing enterprises as the research subject, applying stakeholder theory and agency theory to explore the impact of ESG performance on export competitiveness and its mechanisms.

3. Theoretical Framework and Research Hypotheses

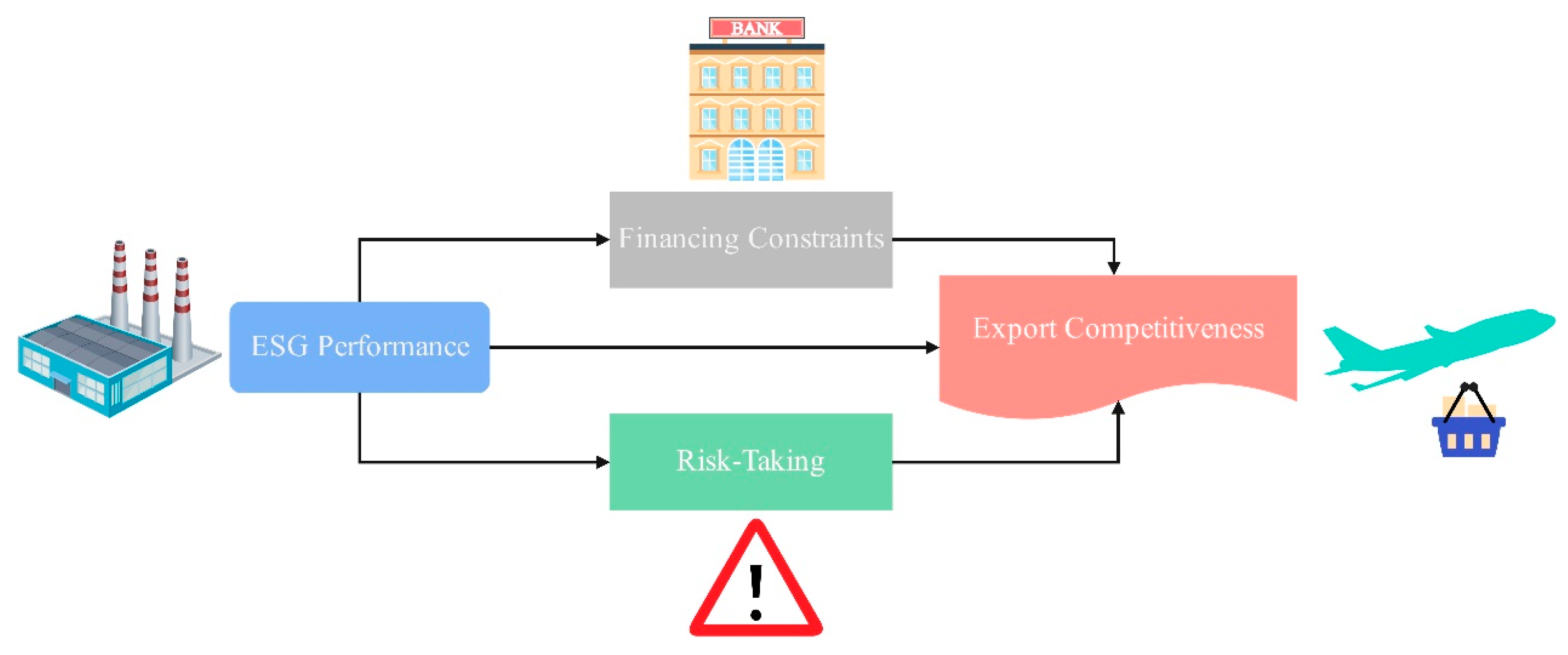

We developed an integrated model that links ESG performance to export competitiveness through two mechanisms—alleviating financing constraints and encouraging risk-taking (

Figure 1).

3.1. ESG Performance and Export Competitiveness of Manufacturing Enterprises

In recent years, an increasing number of stakeholders, investment institutions, and investors have paid attention to the ESG performance of companies. For export-oriented enterprises, ESG performance plays a crucial role in addressing market recognition and information asymmetry, which in turn affects their export competitiveness.

From the perspective of resource acquisition, stakeholder theory and signaling theory provide a strong framework for understanding this relationship. Companies, as “socio-economic entities,” are in a “shared destiny” with various stakeholders, including the environment, employees, creditors, and others. By implementing ESG practices, companies enhance their credibility and trust among stakeholders, reduce communication costs, and improve the efficiency of resource acquisition and allocation [

47]. Particularly in the context of China’s manufacturing industry pushing for green sustainable development and the “Made in China 2025” strategy, positive ESG performance allows companies to gain government policy support and attract investors, thereby securing more financial resources [

48]. These resources are crucial for improving production and R&D efficiency, expanding sales and production scale, and entering international markets, thereby boosting export competitiveness.

Furthermore, positive ESG performance signifies higher levels of management, as a focus on environmental and social responsibility requires companies to have more efficient, transparent management structures, long-term sustainable development plans, and a proactive corporate culture [

49,

50,

51]. These management advantages provide companies with a competitive edge in international trade, helping them break through trade barriers, gradually realize the returns on ESG investments, and ultimately enhance export competitiveness.

From a resource allocation perspective, positive ESG performance draws more attention from the public and markets, helping alleviate internal agency conflicts. On the one hand, integrating social responsibility into management incentive mechanisms helps reduce conflicts of interest between shareholders and management [

52]. On the other hand, companies that actively fulfill their ESG responsibilities not only send signals of sustainable development but also enhance stakeholder trust and risk tolerance, establishing long-term stable business relationships [

53]. These factors contribute to improving resource allocation efficiency and stimulating innovation, further enhancing competitiveness in international trade.

Based on the above analysis, this paper proposes the following hypothesis:

H1. Positive ESG performance has a positive impact on the export competitiveness of manufacturing enterprises.

3.2. ESG Performance, Financing Constraints, and Export Competitiveness of Manufacturing Enterprises

Financing constraints are a key factor influencing export competitiveness, especially for manufacturing enterprises, as they create liquidity pressure and affect investment in production efficiency, scale expansion, and R&D. Particularly in financial environments and systems that are not well-developed, manufacturing companies often face difficulties in securing financing, which in turn limits their ability to enhance export competitiveness [

54].

According to signaling theory [

55], due to information asymmetry, investors have limited understanding of companies, and firms with poor social responsibility performance often struggle to secure investment opportunities or face higher financing costs [

56]. Higher financing costs lead to increased liquidity pressure, thus restricting investments in improving export competitiveness. In contrast, companies with better ESG performance actively disclose social responsibility information, establishing an image of being responsible and sustainable. This signal helps reduce the perceived risk, diminish information asymmetry, increase investor confidence, and lower financing barriers [

57]. Additionally, government subsidies for companies that comply with environmental regulations help alleviate financing constraints.

Furthermore, positive ESG performance enhances employee identification and a sense of belonging, improving internal financing efficiency. From a stakeholder perspective [

58], a company’s enhanced potential for sustainable development and its sense of responsibility increase trust among various stakeholders, lower external financing costs, and facilitate access to the necessary funds [

59]. This, in turn, improves resource allocation and boosts export competitiveness.

Based on this, the paper proposes the following hypothesis:

H2. Positive ESG performance enhances the export competitiveness of manufacturing enterprises by reducing financing constraints.

3.3. ESG Performance, Risk-Taking, and Export Competitiveness of Manufacturing Enterprises

Manufacturing enterprises that focus on export products face various risks and uncertainties during their development. The implementation of ESG sustainable development principles helps these companies make scientific strategic decisions, thus enhancing their core competitiveness.

From an information effect perspective [

60], positive ESG performance sends signals to the market that the company actively practices sustainable development, has an effective monitoring system, and adheres to high governance standards [

61]. These signals demonstrate the company’s strong organizational flexibility, environmental adaptability, and risk management capabilities. This not only helps avoid losses from risk aversion but also opens up more development opportunities. Additionally, by actively disclosing ESG information, companies enhance information transparency, increasing stakeholder tolerance for risk in decision-making, thus creating a favorable environment for increased R&D investment and innovation [

62].

From an agency theory perspective [

63], excellent ESG performance is often accompanied by a more rational corporate governance structure and compensation incentive systems [

64]. This reduces agency costs and short-term managerial behavior, stimulating the company to improve production efficiency and R&D innovation. These management advantages help companies maintain a competitive edge when facing uncertainties in export markets, increase their risk-taking capacity, optimize resource allocation, reduce production costs, and ultimately improve export competitiveness.

Therefore, the paper proposes the following hypothesis:

H3. Positive ESG performance enhances the export competitiveness of manufacturing enterprises by increasing their risk-taking capacity.

4. Research Design

4.1. Sample Selection and Data Sources

This study focuses on publicly listed manufacturing companies in China, aiming to explore the mechanisms through which ESG performance affects their export competitiveness. Since ESG performance data has been gradually collected by various institutions since 2009, and the China Customs database ceased disclosing company names and related information after 2021, the sample selection process follows these steps: First, data from 2009, which could have been influenced by the 2008 U.S. subprime mortgage crisis and the 2010 European debt crisis, was excluded. We selected ESG data disclosed by manufacturing companies listed on the Shanghai and Shenzhen A-share markets from 2011 to 2021. During the data processing, companies categorized as Special Treatment (ST), * ST, or ** ST, as well as those in the financial industry, were excluded. Incomplete or missing samples were also removed, and extreme values at the 1st and 99th percentiles were addressed. Then, the ESG data from the selected manufacturing companies were cross-matched with information from the China Customs database, including company names, company identification codes, and export values, resulting in a final sample of 9641 valid observations. Specifically, ESG performance data were sourced from the Huazheng database, export value data from the China Customs database, and financial information related to financing constraints and risk-taking levels were obtained from the Wind and Guotai An databases. All relevant data were analyzed using Stata 17.0 for correlation and regression analysis.

4.2. Variable Selection and Measurement Methods

This study uses ESG performance of Chinese manufacturing companies as the core explanatory variable and export competitiveness as the dependent variable, with multiple control variables introduced to analyze their impact on export competitiveness. The definitions and symbols for each variable are shown in

Table 1.

4.2.1. Explanatory Variable: ESG Performance and Its Measurement

The core explanatory variable in this study is the ESG performance of manufacturing companies. Existing literature mainly uses custom-built indicator systems or ratings from third-party institutions [

65]. Given the potential subjectivity and limited coverage of self-constructed indicator systems, this study uses ESG ratings provided by the Huazheng database as the explanatory variable. During data processing, to avoid the issue of excessively large ESG scores that could lead to extreme regression coefficients, the ESG scores were divided by 100 before being included in the regression model for analysis.

4.2.2. Dependent Variable: Export Competitiveness of Manufacturing Enterprises and Its Measurement

The export competitiveness of manufacturing enterprises serves as the dependent variable in this study. From the micro-enterprise perspective, the export competitiveness of manufacturing enterprises is measured using two indicators: the company’s export volume—representing export quantity—and the technical complexity of the company’s exports—representing export product quality. The export volume is measured using export value data from the China Customs database, with natural logarithms taken for export values, using the formula (1 + Export Value) to account for potential zero values in export data. Additionally, to measure the technical complexity of the company’s exports, we refer to the method used by Sheng and Mao (2017) [

66], building on Hausmann et al. (2007) [

39] approach, calculating the export technical complexity of a company based on the following formula:

First, the complexity of product (k) is calculated using the following formula:

where

k represents the product,

c represents the country or region,

xck is the export value of product

k in country or region

c, and

Xc is the total export value of country or region

c. The term

Xck/Xc represents the export share of product

k in country or region

c, and

pcgdpc refers to the actual GDP (Gross Domestic Product) per capita of country or region

c. In this context, the weight (

xck/Xc)

/(

) indicates the export advantage of product

k in country or region

c.

Next, following the approach of Sheng and Mao (2017) [

66], the export technical complexity at the firm level is calculated using the following formula based on the China Customs database:

where

Xik is the export value of product

k by firm

i, and

Xi represents the total export value of firm

i. The term

xik /Xi represents the proportion of product

k ‘s export in the total export of firm

i.

Finally, to account for the impact of product quality on export technical complexity, the following formula is used to adjust the export technical complexity at the firm level:

where the adjustment is made by incorporating the product quality factor into the original product complexity formula from Formula (2).

Specifically, the product-level quality factor qk is proxied by the unit value (UV) of each product, defined as the export value divided by the export quantity at the HS-8 product–year level from the China Customs database. We winsorize ln(UV) at the 1st and 99th percentiles to mitigate the influence of outliers, and normalize it within each year so that the mean equals one. The adjusted product complexity, denoted as = PRODYk × qk, is then used to construct the firm-level quality-adjusted export sophistication index according to Formula (3). This adjustment allows the export sophistication index to reflect not only the technological content of exports but also the quality dimension of the products.

4.2.3. Mechanism Variables

First, for measuring financing constraints, studies typically use either a single indicator or a composite set of variables. Compared to the potential subjectivity and limitations of single indicators, composite indices cover a broader range of factors and are more comprehensive. Therefore, this study adopts the SA index used by Hadlock and Pierce (2010) [

67] to measure financing constraints. The SA index is constructed based on firm size and firm age [

67], and is calculated as:

A higher (less negative) SA indicates more severe financial constraints, while a lower (more negative) SA indicates less severe financial constraints [

67].

Firm size (Size) is measured as the natural logarithm of total assets, and firm age (Age) is consistently defined as the difference between the current year and the IPO year. This definition ensures that firm age takes positive values, consistent with the standard in Hadlock and Pierce (2010) [

67].

This index has been widely applied in the literature to capture financing difficulties faced by firms of different sizes and ages.

In this formula, the indicators are based on two completely exogenous variables: the company’s asset size and the company’s age. This method is convenient and intuitive, and its results are relatively robust and reliable, avoiding the problems of measurement errors or endogeneity. Here, Size represents the natural logarithm of the company’s total assets (in millions), and Age represents the difference between the current year and the IPO year. In general, the higher the value of this index (less negative), the more severe the financing constraints faced by the company.

Secondly, when measuring a company’s risk-taking behavior, common indicators typically include stock return volatility. Compared to traditional financial indicators, this approach is less constrained by financial statements and better reflects a company’s risk-taking behavior. In this study, we follow the approach of Chen and Zhang (2021) [

68] by using the natural logarithm of the annualized monthly return standard deviation (RISK) as the measure of a company’s risk-taking behavior. The calculation formula is as follows:

where

ri,j,t represents the return of company

i in year

t during month

t, and

T is the total number of months in each accounting year.

4.2.4. Control Variables

The selection of control variables in this study follows the approach of Tsang et al. (2021) [

69]. The selected control variables are listed in

Table 1.

In addition, we include the provincial business environment as a contextual variable to capture the degree of marketization (MARKET). The data are obtained from the

China Provincial Marketization Index compiled by the National Economic Research Institute of China. For comparability across provinces and years, the original index is standardized before estimation by subtracting its overall mean and dividing by the standard deviation over the full sample. This standardized variable (mean = 0, SD = 1) is used in regressions, whereas

Table 2 reports the raw (unstandardized) MARKET values.

4.3. Model Construction

To investigate the impact of ESG performance on the export competitiveness of manufacturing enterprises and its mechanisms, this study constructs the following econometric models:

In these models, i, c, j, and t represent firm, industry, region, and time, respectively. ESI is the firm-level export technical complexity, EXPORT is the firm’s export value, ESG represents the firm’s ESG performance indicator, SA is the firm’s financing constraint, RISK is the firm’s risk-taking level, γj is the industry fixed effect, φt is the time fixed effect, and εit is the random disturbance term. The remaining variables are control variables.

The extended specifications include industry, province, and year fixed effects to control for unobservable heterogeneity across sectors, regions, and time. Firm fixed effects were considered but not included due to limited within-firm variation over the sample period. Throughout the empirical analysis, we define the baseline as the specification without industry, province, or year fixed effects; models that add these fixed effects are reported as robustness checks.

For clarity, throughout the empirical sections we refer to the baseline specification as Models (6) and (7), consistent with the model numbering introduced in

Section 4.3; note that Model (4) defines the SA index rather than a regression equation. Additionally, as a robustness extension (not part of the baseline), we consider industry-by-year fixed effects to absorb sector–time shocks and include a lagged peer ESG

as an alternative instrument to reduce simultaneity.

5. Empirical Analysis

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

As shown in

Table 2, regarding the dependent variable “Export Technical Complexity of Manufacturing Listed Companies” (ESI), the mean is 11.1350 and the median is 11.1321, indicating that most companies exhibit relatively consistent performance in the technical complexity of their export products, with a high level of export quality. The mean for “Company Export Value” (EXPORT) is 14.6997, with a minimum of 0 and a maximum of 23.3626, highlighting significant variation in the export performance across firms. For the explanatory variable “Company ESG Performance” (ESG), the minimum value is 0.5867, the mean is 0.7331, and the maximum value is 0.8350, showing considerable differences in ESG performance among companies. Regarding the mediating variable “Company Financing Constraints” (SA), the standard deviation is 0.2231, with a minimum value of −4.3486 and a maximum value of −3.2196, indicating significant variation in financing constraints across companies, with considerable room for improvement. The mean of the “Risk-Taking Level” (RISK) is 0.0296, with a standard deviation of 0.0318, indicating noticeable differences in risk-taking behavior among firms. The distributions of other control variables are within reasonable ranges, suggesting a broad and diverse sample.

5.2. Baseline Results

Table 3 presents the baseline regression analysis based on Models (6) and (7). The baseline includes ESG (the key explanatory variable) and a set of controls (e.g., SIZE, LEV, ROA, GRO, HHI, MARKET, AGE) and does not include industry, province, or year fixed effects. Columns (2) and (4) add industry, province, and year fixed effects to assess robustness. Therefore, the baseline model includes only control variables, while the extended models incorporate the fixed effects.

Age is consistently calculated as “current year–IPO year” across all regression models. The regression coefficients for ESG are 0.0132 (p < 0.05) and 0.0241 (p < 0.01), both significantly positive. To address extreme outliers (such as the maximum value of RISK), we apply winsorization, limiting the range of RISK to the 1st and 99th percentiles. Alternatively, robust checks excluding these outliers are conducted to ensure the validity of our results.

In the regression, MARKET is used as a standardized index with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. Descriptive statistics report the raw values of MARKET, which may include negative values, reflecting performance below the sample mean. To mitigate potential endogeneity due to omitted variables, we additionally estimate specifications that include industry, province, and year fixed effects. These fixed-effects models are presented as robustness checks; firm fixed effects are excluded due to limited within-firm variation over the sample period.

Columns (1) and (3) report results with control variables only, while Columns (2) and (4) include fixed effects. These results show that ESG performance significantly promotes improvements in export technical complexity and export value for manufacturing listed companies, enhancing export competitiveness.

The relatively high R2 for ESI (≈0.61) primarily reflects the inclusion of multiple fixed effects (industry, province, and year), which absorb substantial cross-sectional and time-series variation rather than overfitting the substantive relationship. Columns (2) and (4) present the regression results after adding control variables and simultaneously controlling for industry, province, and time fixed effects. The regression coefficients are 0.0132 (p < 0.05) and 0.0241 (p < 0.01), also significantly positive, further confirming the positive role of ESG performance in enhancing export competitiveness. This suggests that when manufacturing listed companies perform better in ESG, the positive signals they emit are more likely to be recognized by stakeholders. Specifically, companies not only reduce the cost of acquiring the resources needed for development but also stimulate enthusiasm for product innovation and service upgrades, thereby enhancing their competitiveness in international trade. Therefore, the ESG performance of manufacturing listed companies significantly promotes the improvement of export competitiveness, confirming the validity of Hypothesis 1.

5.3. Mechanism Testing

5.3.1. Financing Constraints Mechanism

Table 4 presents the regression results for Models (6) through (10). Columns (1) and (2) show the baseline regression results, while Column (3) displays the regression results for the impact of financing constraints on ESG performance. The regression coefficient is −0.171 and significantly negative, indicating that strong ESG performance effectively reduces financing constraints for companies. As defined in

Section 4.2.3, a higher (less negative) SA value indicates more severe financing constraints, while a lower (more negative) SA value reflects fewer constraints. Therefore, the negative coefficient of SA confirms that ESG performance helps alleviate financing constraints. Columns (4) and (5) show the regression results when both financing constraints and ESG performance are included in the model. The regression coefficients for financing constraints are −0.0121 and −0.0179, both significantly negative, while the coefficients for ESG performance are 0.0130 and 0.0238, both significantly positive. Combining these results with the earlier baseline regression findings, we can conclude that good ESG performance effectively reduces financing constraints, thereby enhancing the export competitiveness of manufacturing enterprises. This regression result confirms Hypothesis 2.

5.3.2. Risk-Taking Mechanism

Table 5 presents the regression analysis conducted for Models (9), (10), and (11) based on the baseline regression results from Models (6) and (7). Columns (1) and (2) show the baseline regression results (without industry, province, or year fixed effects), while Column (3) presents the regression results for the impact of risk-taking behavior on ESG performance. The regression coefficient is 0.0146 and significantly positive, suggesting that strong ESG performance enhances a company’s risk-taking capacity. Columns (2) and (3) show the regression results when both risk-taking behavior and ESG performance are included in the model. The regression coefficients for risk-taking behavior are 0.0085 and 0.0152, both significantly positive, while the coefficients for ESG performance are 0.0131 and 0.0239, both significantly positive. Combining these results with the baseline regression results, we can conclude that good ESG performance effectively enhances a company’s risk-taking capacity, which in turn boosts the export competitiveness of manufacturing enterprises. This regression result confirms Hypothesis 3.

5.4. Robustness Checks

5.4.1. Instrumental Variables

To further verify the robustness of the regression results, this study uses the industry-average ESG score for the same year as an instrumental variable for the test, based on peer effects in choosing the instrument. ESG performance of companies within the same industry exhibits strong competitiveness and imitation, and is highly exogenous, meaning that the ESG performance of peer companies does not have a direct impact on the export performance of the firm in question. First, the validity of the instrumental variable is tested: (1) The minimum eigenvalue statistic is 12,111.8, far exceeding the critical value of 16.3 for 2SLS, indicating that there is no weak instrument problem; (2) Since there is only one instrument, there is no issue of over-identification. Based on these results, the choice of the instrumental variable is valid. Next, the regression results using the instrumental variable are shown in

Table 6. The regression coefficient for ESG performance remains unchanged in sign, and the significance test passes, indicating that after controlling for endogeneity, the research conclusions remain valid. While the industry-average ESG (same-year) is a strong and relevant instrument, a potential concern is the exclusion restriction: industry-level ESG might correlate with firms’ export performance through sectoral regulations, demand shifts, or global supply-chain shocks operating at the industry–year level. To address this concern without altering our core design, we discuss two complementary strategies—adding industry-by-year fixed effects to absorb sector–time shocks and instrumenting with lagged peer ESG (t − 1) to reduce simultaneity. Both strategies are standard in the literature and, when implemented, are expected to yield estimates similar in sign and significance to our baseline IV results.

5.4.2. Propensity Score Matching Robustness Check

To further test the robustness of the results, this study employs Propensity Score Matching (PSM), using companies with ESG scores above the mean as the treatment group and those below the mean as the control group. A 1:1 nearest-neighbor matching method is applied using the Logit model, and regression analysis is performed on the matched samples. Control variables include company size, number of patents, debt ratio, growth rate, proportion of the largest shareholder’s ownership, proportion of independent directors, Herfindahl index, capital intensity, dual positions in management, and company nature. The regression results for the matched samples are shown in

Table 7. Columns (1) and (2) indicate that after eliminating firm characteristic differences, the impact of ESG performance on export competitiveness is positive at both the 1% and 5% significance levels, supporting the conclusions of this study.

5.4.3. Robustness Check by Replacing the Explanatory Variable

To further validate the robustness of the regression results, the study replaces the ESG score from the Huazheng database with the ESG score from Hexun, which is widely used in relevant ESG research, as the core explanatory variable. This is considered a reliable alternative variable. The regression results are shown in

Table 8. The results for the core explanatory variable are consistent with the baseline regression, with only minor changes in the significance of a few control variables, indicating that even when the explanatory variable is replaced, the regression results remain robust.

5.4.4. Robustness Check by Changing the Time Sample

Considering that the 2015 Chinese stock market crisis might have affected stakeholder trust and expectations, and consequently impacted company performance, the study removes the data for the year 2015 to ensure the reliability of the results. Regression analysis is then performed on the baseline model. The regression results, shown in

Table 9, reveal that after excluding the year 2015 only, the impact coefficients of ESG performance on export technical complexity and export value are 0.0139 and 0.0242, respectively, both showing positive effects at the 5% significance level, thus confirming the robustness of the regression results. As a result, the sample size decreased from 9641 to 8858 (≈8%), which is consistent with removing one single year from the 2011–2021 panel.

6. Further Analyses

6.1. Moderating Effect of Business Environment

This study further analyzes how the business environment might moderate the impact of ESG performance on enhancing export competitiveness. Specifically, we hypothesize that in regions with a better business environment, the positive effect of ESG performance on export competitiveness may be weaker for the following reasons: First, in regions with a better business environment, the government’s intervention in the market economy is lower, and companies can access a significant amount of resources needed for future development through intermediary channels. These resources may substitute for those obtained through ESG disclosure, thereby diminishing the effect of ESG performance on enhancing export competitiveness. Second, in regions with a more developed financial market, the communication cost between financial institutions and enterprises is lower, making it easier for companies to obtain the resources they need, which further reduces the role of ESG performance in improving export competitiveness. Third, regions with better business environments typically have more robust legal systems, stronger regulatory oversight, and higher levels of law enforcement, so companies’ reliance on informal institutional routes (such as ESG performance) to improve export competitiveness is lower.

Therefore, in regions with a weaker business environment, good ESG performance becomes an important means to enhance export competitiveness. To test this hypothesis, this study uses an interaction model, following the approach of scholars such as Niu et al. (2023) [

70] and Su et al. (2023) [

71], and selects the “development level of non-state-owned enterprises” as a secondary index within the marketization index to reflect the business environment from a macro perspective. The marketization index (MARKET) is standardized (mean = 0, SD = 1) for comparability across provinces; hence some negative values appear. The regression results shown in

Table 10 indicate that in Columns (1) and (2), the interaction term (ESG × MARKET) has negative regression coefficients of −0.0128 and −0.0174, both significantly negative, while the ESG performance coefficients in the baseline regression models are positive. This suggests that the regression coefficients of the moderating variable have the opposite sign to the main effect coefficients, further validating the moderating effect of the business environment on ESG performance. Specifically, in regions with poorer business environments, the positive effect of good ESG performance on export competitiveness is more significant.

6.2. Moderating Effect of Institutional Investor Ownership

Institutional investors, as independent shareholders of companies, not only stimulate innovation but also effectively supervise corporate managers, preventing short-term behaviors driven by personal interests. In shareholder structures, when the proportion of institutional investors is high, they can effectively curb managerial myopia, ensuring the long-term development of the company. Moreover, the advantage of institutional investors lies in their ability to enhance a company’s risk-taking capacity. By creating a favorable investment environment for managers, institutional investors help them better analyze risks and opportunities, thus making decisions that benefit the company’s long-term development and improving corporate performance.

Therefore, when institutional investors hold a higher proportion of shares and adopt a long-term investment style, they provide more robust support for the company’s long-term development, thereby strengthening the company’s core competitiveness and diminishing the direct effect of ESG performance on export competitiveness. The regression results in

Table 11 show that in Columns (1) and (2), the interaction term (ESG × INS) has negative coefficients of −0.0183 and −0.0152, both significantly negative, while the ESG performance coefficients in the baseline regression models are positive. This suggests that when the proportion of institutional investor ownership is low, ESG performance has a stronger positive effect on export competitiveness; conversely, when the proportion of institutional investor ownership is high, the positive effect of ESG performance on export competitiveness weakens.

7. Discussion

This study investigates how corporate ESG performance influences export competitiveness among Chinese manufacturing firms, with a particular focus on alleviating financing constraints and enhancing risk-taking capacity. Our findings show that stronger ESG performance significantly improves both export technical complexity and export value. These results align with the work of Wu et al. (2022), who demonstrated that better ESG performance enhances export intensity by alleviating financing constraints and fostering innovation [

72]. Our study also corroborates Ma (2025), who found that ESG performance is positively associated with higher technological complexity in exported products [

73]. By improving product quality and technological sophistication, ESG contributes directly to a firm’s ability to compete in international markets, as indicated by both Wu et al. (2022) and Ma (2025) [

72,

73].

However, our results diverge from some previous studies, particularly regarding the role of the business environment in shaping ESG performance’s impact on export competitiveness. In contrast to Ma et al. (2024), who found that ESG performance improves export resilience and risk recovery across various business environments [

74], our study shows that the positive impact of ESG is more pronounced in regions with weaker business environments. We argue that in less-developed regions, where institutional and financial constraints are more significant, firms are more dependent on ESG practices to secure external resources and improve their competitive position in international markets. On the other hand, firms in better business environments may have easier access to resources and financing, which reduces the reliance on ESG performance for improving export competitiveness.

Furthermore, our study builds on the work of Yue and Li (2024), who examined the influence of ESG practices on domestic value added to exports during periods of technological change [

75]. They found that ESG practices increased the domestic value-added share embodied in exports, with significant spatial spillovers across regions. Similarly, our study finds that ESG practices play a crucial role in improving export competitiveness, particularly in regions with weaker business environments. This aligns with Yue and Li’s findings that regional characteristics, such as the business environment, influence the effectiveness of ESG practices in enhancing export performance. In regions with weaker business environments, firms appear to gain more from adopting ESG practices as a strategy to navigate institutional barriers.

In addition, our study provides further insights into the relationship between ESG and export sophistication. While Li et al. (2022) argued that individual ESG factors, such as corporate social responsibility (CSR), have minimal effects on export quality [

15], our research demonstrates that an integrated approach to ESG—incorporating environmental, social, and governance practices—significantly enhances export technical complexity and adds value to exports. By treating ESG as a comprehensive set of practices rather than focusing on individual components, firms can better position themselves to compete in the global market. This finding is consistent with Ma (2025), who similarly observed that ESG is positively correlated with the technological complexity of exports [

73].

Additionally, our study shows that ESG performance helps alleviate financing constraints, particularly for firms facing liquidity challenges. This result contrasts with some existing research, which suggests that despite strong ESG performance, firms may still face significant financing barriers due to structural issues in financial markets. We believe this divergence can be explained by the specific context of China, where recent government policies supporting green finance and ESG-related investments have made it easier for firms with strong ESG practices to access capital. In contrast, other regions may not have similar financial systems or policies in place to support ESG-focused investments, limiting the impact of ESG on alleviating financing constraints.

Our findings also complement the work of Xu et al. (2024), who explored how ESG practices serve as a strategy for Chinese exporters to navigate international competition, particularly during the US-China trade war [

76]. Xu et al. found that Chinese exporters exposed to tariffs intensified their ESG engagement as a market-access and signaling strategy. Similarly, our research suggests that ESG practices not only help firms improve their export competitiveness but also serve as an important strategy for firms to signal their commitment to sustainability in the face of external pressures such as trade wars and global market uncertainty.

Finally, Wu and Wang (2024) emphasized the importance of ESG in improving the export competitiveness of Chinese manufacturing firms [

77]. Our study supports their conclusion, showing that ESG performance is associated with improved corporate risk-taking, which is a key factor in enhancing export competitiveness. We extend their work by emphasizing the moderating role of business environment—ESG’s impact is significantly stronger in regions with weaker business environments, where firms face greater institutional and financial challenges.

In conclusion, while our study largely supports the findings of previous research on the positive effects of ESG on export competitiveness, it also introduces new insights into the nuanced role of the business environment in shaping these effects. Our results suggest that ESG performance is particularly critical in regions with weaker business environments, where firms face more significant institutional and financial challenges. Future research could explore how ESG practices influence export competitiveness in other national and regional contexts, particularly comparing the effects of ESG in developed versus developing countries. Examining how ESG practices affect different industries and firm types will further enhance our understanding of the global impact of ESG on international competitiveness.

8. Conclusions and Implications

This study, based on panel data from Chinese A-share listed manufacturing companies between 2011 and 2021, combined with data from the China Customs database, employs empirical analysis to examine the impact of corporate ESG performance on export competitiveness and the underlying mechanisms. The results indicate that ESG performance significantly promotes the enhancement of export competitiveness. Specifically, in terms of both export complexity and export value, strong ESG performance contributes positively to the improvement of export competitiveness. Further analysis reveals that superior ESG performance improves financing conditions and increases risk-taking capacity, thus enhancing export competitiveness. Additionally, the study identifies that in regions with a poor business environment and in firms with a low proportion of institutional investors, the positive effect of ESG performance on export competitiveness is more pronounced.

This research makes three key contributions.

First, it constructs a company-level export competitiveness index, which enriches the understanding of ESG performance in the context of export competitiveness, particularly for manufacturing enterprises. While much of the existing literature focuses on export competitiveness from a macroeconomic perspective, there is limited research that integrates ESG performance within the framework of sustainable development, especially at the micro-enterprise level. By examining how ESG performance influences export competitiveness through mechanisms such as financing constraints and risk-taking, this study provides new theoretical insights into these relationships.

Second, it tests two measurable mediating mechanisms—financing constraints and risk-taking—that help explain the impact of ESG performance on export competitiveness. This adds a valuable layer of understanding to the existing literature by demonstrating the specific channels through which ESG practices affect export performance.

Third, the study emphasizes the differences in ESG performance’s effect based on institutional environments and institutional investor ownership. The findings highlight how the effect of ESG performance is stronger in regions with poorer business environments and among firms with lower institutional investor ownership. This provides important implications for policymakers and business leaders seeking to optimize ESG strategies according to varying institutional contexts.

The findings of this study offer several important implications.

From a government/regulatory perspective, it is essential to strengthen guidance on ESG performance and encourage the adoption of credible ESG practices. Governments and regulators should provide policy support and technical assistance—especially for high-pollution, resource-intensive industries—to translate ESG awareness into process upgrades, technological innovation, and measurable green transformation. At the same time, China’s ESG rating and disclosure system should be further localized, unified, and made machine-readable with third-party assurance, thereby improving data quality and comparability and reducing potential bias from local measurement methodologies. Extending proportionate disclosure requirements and pilot programs to large private exporters and key SME suppliers would mitigate the listed-firm selection concern and enable staged rollouts that lend themselves to natural-experiment designs (e.g., difference-in-differences across provinces or industries). Finally, tighter oversight of ESG information disclosure—paired with transparent reward and penalty mechanisms linked to verifiable outcomes—can curb greenwashing and sustain a healthy ESG ecosystem, while the parallel development of more precise product-quality statistics (e.g., unit values and technology classifications in customs microdata) will support both policy monitoring and future causal assessments.

From a corporate perspective, firms should deepen their understanding of ESG principles and treat ESG as a long-horizon investment rather than reacting to short-term performance fluctuations. Concretely, companies can embed ESG into strategy and organization by aligning governance structures, incentive systems, and talent pipelines with ESG goals and by establishing dedicated budgets or internal funds for capability building. Substantive, timely, and assured ESG disclosure—preferably in standardized, machine-readable formats—will enhance reputation, reduce information asymmetry, and strengthen brands in international markets. For manufacturing firms in particular, tracking and reporting product-level quality and innovation outputs helps translate ESG efforts into export competitiveness and provides observable, testable outcomes for future research. Where corporate groups include non-listed subsidiaries or strategic suppliers, encouraging aligned reporting across the value chain can reduce selection bias and generate richer evidence on ESG’s real effects.

From a market/investor perspective, participants should shift from narrow reliance on financials or short-term performance toward integrated ESG-financial analysis that balances near-term returns with long-term resilience and sustainability. Stewardship should focus on verifiability and comparability—engaging issuers on disclosure quality, third-party assurance, and progress against auditable milestones. Capital allocation tools such as green bonds and sustainability-linked instruments can be tied to measurable targets (e.g., emissions intensity, product quality upgrades), aligning incentives and producing data suitable for rigorous evaluation. Because our evidence is based on listed firms and local ESG metrics, investors can further strengthen inference by supporting initiatives that broaden disclosure coverage and by exploiting quasi-experimental settings (e.g., index inclusions or stewardship campaigns) that allow researchers to identify the causal links between ESG improvements and long-term performance.