Joint Sustainability Reports (JSRs) to Promote the Third Mission of Universities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theory—Literature Review

2.1. Sustainability Reporting by Universities

2.2. Between In-House Implementation and Outsourcing

2.3. Networks for Sustainability Reporting

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Sample

3.2. Interview-Guide

3.3. Data Analysis

- Q1—Challenges and problems in daily work,Q2—Assessment of existing resources,Q3—Cooperation with other HEIs, networks and external third parties,Q4—Supply chain information,Q5—Orientation towards the private sector,Q6—Specification of certain report formats,Q7—Common report for all HEIs.

- Q1—Obligation vs. voluntary action; lack of expertise; lack of data availability; lack of personnel; limited time resources; lack of automation; lack of regular monitoring of KPIs; lack of financial resources; qualification requirements; learning by doing; communication barriers; non-ownership of property;Q2—Insufficient resources; third-party funding; one-man/woman show;Q3—External cooperation; internal cooperation; superregional cooperation;Q4—Procurement processes; criteria for selection of suppliers; supplier evaluation;Q5—Scope of reporting; relevant key figures; best practice, brainstorming ideas for the report; orientation data points; conformity criteria; benchmark; bookable service offerings; digital solutions;Q6—Usefulness; automatic reporting; freedom of design; comparability; threshold and feasibility, exchange of information;Q7—Support; recognition of universities of applied sciences; incentives; complexity.

4. Results

4.1. Current Challenges and Problems

4.2. Available Resources

4.3. Cooperation with Universities, Networks and External Companies

4.4. Exchange of Information Between Universities and Business Partners

4.5. Guidance from Private Sector Companies

4.6. Use of Reporting Formats

4.7. Opportunities of a Joint Sustainability Report

5. Discussion

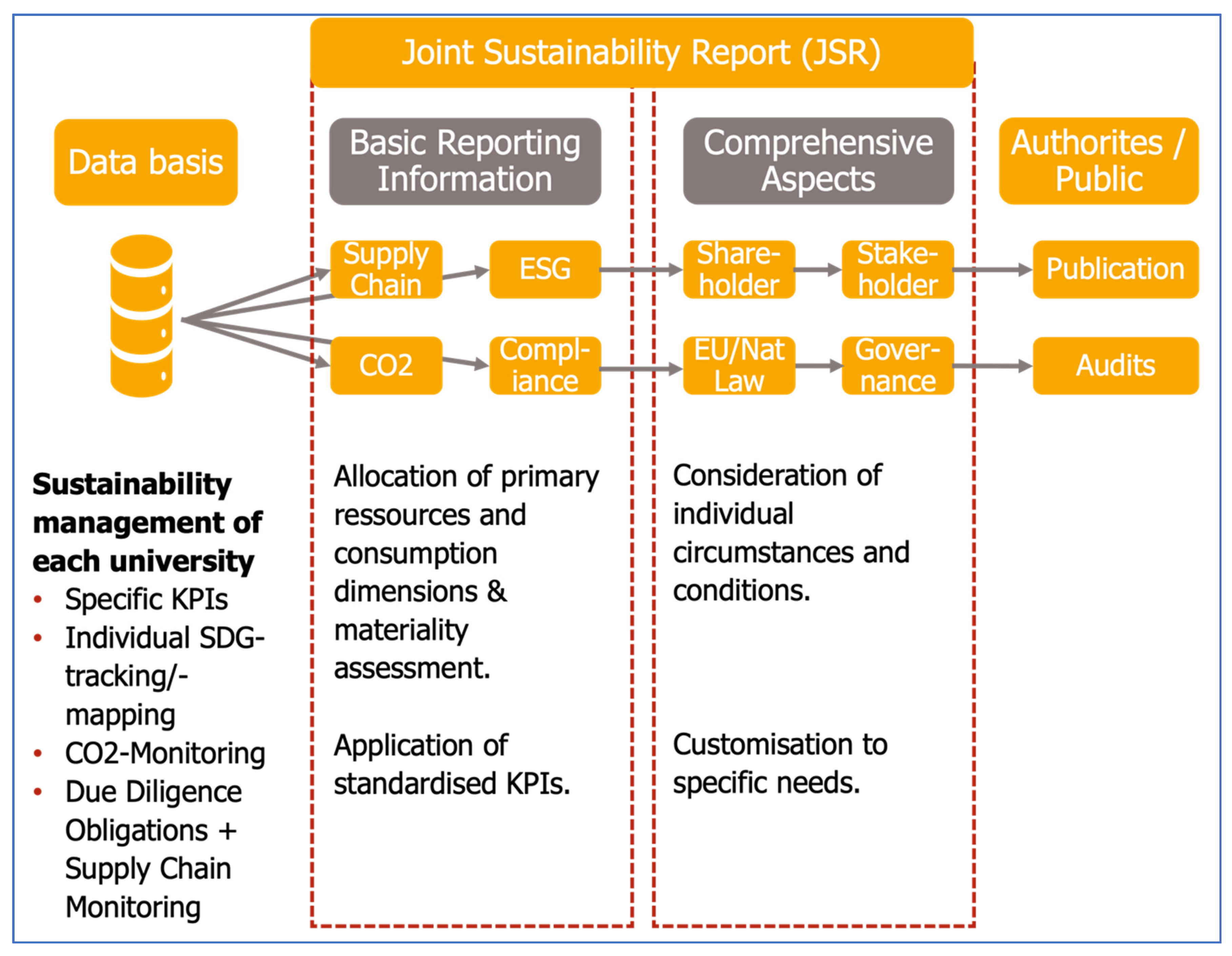

6. Joint Sustainability Reports (JSR)

7. Conclusions

7.1. Research Limitations

7.2. Directions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Sub-Category | Codes | Illustrative Interview Statements |

| Challenges and Problems in Daily Work | Lack of expertise | “Existing know-how is an issue, it is difficult to rely on expertise.” (E3) |

| Lack of data availability | “Data availability is the second major issue […] we have to check what already exists.” (E2) | |

| Lack of personnel | “We do not have the personnel to handle the whole matter professionally.” (E1) | |

| Limited time resources | “Personally I do not have the resources for this; I have a 20-h position.” (E4) | |

| Lack of automation | “It is still very labour-intensive; data must be laboriously gathered.” (E5) | |

| Lack of financial resources | “The real challenge is resources, staffing and, of course, budget” (E4) | |

| Qualification requirements | “A lot of learning by doing.” (E4) |

References

- Ceulemans, K.; Molderez, I.; Van Liedekerke, L. Sustainability reporting in higher education: A comprehensive review of the recent literature and paths for further research. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 106, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R. The state of sustainability reporting in universities. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2011, 12, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahl, W.; Teichert, V.; Meier, T.; Schröder, J.; Huggins, B. Nachhaltigkeit. In Umwelt Interdisziplinär; Universitätsbibliothek: Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ott, K.; Döring, R. Theorie und Praxis Starker Nachhaltigkeit; Metropolis: Marburg, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Döring, R. Wie Stark ist Schwache, wie Schwach Starke Nachhaltigkeit? Wirtschaftswissenschaftliche Diskussionspapiere; No. 08/2004; Universität Greifswald, Rechts- und Staatswissenschaftliche Fakultät: Greifswald, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Elkington, J. The triple bottom line. In Environmental Management: Readings and Cases; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997; Volume 2, pp. 49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Borgwardt, A. Nachhaltigkeit an Hochschulen. In Eine Stunde für die Wissenschaft; Paper No. 12; Friedrich Ebert Stiftung: Berlin, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Daub, C.-H. Assessing the quality of sustainability reporting: An alternative methodological approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dienes, D.; Sassen, R.; Fischer, J. What are the drivers of sustainability reporting? A systematic review. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. (SAMPJ) 2016, 7, 154–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceulemans, K.; Lozano, R.; Alonso-Almeida, M.D.M. Sustainability Reporting in Higher Education: Interconnecting the Reporting Process and Organisational Change Management for Sustainability. Sustainability 2015, 7, 8881–8903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haj Taieb, S. Measuring the third mission of European Universities: A systematic literature review. Soc. Econ. 2024, 46, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CHE. Centrum für Hochschulentwicklung. Third Mission der Hochschulen. 2025. Available online: https://www.che.de/third-mission/ (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Moggi, S. Sustainability reporting, universities and global reporting initiative applicability: A still open issue. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2023, 14, 699–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compagnucci, L.; Spigarelli, F. The Third Mission of the university: A systematic literature review on potentials and constraints. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 161, 120284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European University Association [EUA]. Universities and Innovation: Beyond the Third Mission; EUA: Brussels, Belgium, 2019; Available online: https://www.eua.eu/our-work/expert-voices/universities-and-innovation-beyond-the-third-mission.html (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- European University Association [EUA]. A Green Deal Roadmap for Universities; EUA: Brussels, Belgium, 2023; Available online: https://eua.eu/publications/reports/a-green-deal-roadmap-for-universities2.html (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- European Commission. Commission Recommendation on a Voluntary Sustainability Reporting Standard for Small and Medium-Sized Undertakings (C(2025) 4984 Final); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Recommendation on a Voluntary Sustainability Reporting Standard for Small and Medium-Sized Undertakings: Questions and Answers. DirectorateGeneral for Financial Stability, Financial Services and Capital Markets Union; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Impact Europe, Global Alliance of Impact Lawyers, & Euclid Network. 2024. Available online: https://www.impacteurope.net/sites/www.evpa.ngo/files/publications/Joint_Statement_VSME_July2024.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Bannier, C. Nachhaltigkeitsberichterstattung—Aktuelle Herausforderungen und Chancen für Großunternehmen und Mittelständler. In Mit Sustainable Finance die Transformation Dynamisieren. Wie Finanzwirtschaft Nachhaltiges Wirtschaften Ermöglicht; Zwick, Y., Jeromin, K., Eds.; Springer: Hamburg, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralph, M.; Stubbs, W. Integrating environmental sustainability into universities. High. Educ. 2014, 67, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, D.; Jenssen, S.; Tappeser, V. Getting an empirical hold of the sustainable university: A comparative analysis of evaluation frameworks across 12 contemporary sustainability assessment tools. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2015, 40, 785–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, S.; Bassen, A. Towards a sustainability reporting guideline in higher education. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2018, 19, 218–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, A.; Asmuss, M. Benchmarking tools for assessing and tracking sustainability in higher educational institutions. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2013, 14, 449–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R.; Young, W. Assessing sustainability in university curricula: Exploring the influence of student numbers and course credits. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 49, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughter, P.; Wright, T.; McKenzie, M.; Lidstone, L. Greening the ivory tower: A review of educational research on sustainability in post-secondary education. Sustainability 2013, 5, 2252–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarime, M.; Tanaka, Y. The issues and methodologies in sustainability assessment tools for higher education institutions: A review of recent trends and future challenges. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 6, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassen, R.; Azizi, L. Voluntary disclosure of sustainability reports by Canadian universities. J. Bus. Econ. 2018, 88, 79–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, K.-H.; Shi, H.; Weaver, S. What are the motivations for and obstacles to disclosing voluntary sustainability reporting by U.S. universities? J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 409, 137232. [Google Scholar]

- Sassen, R.; Azizi, L.; Mertins, L. What are the Motivations and Barriers to Disclosing Voluntary Sustainability Information by U.S. Universities in STARS Reports? J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 359, 131912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, P. Nachhaltigkeitsberichterstattung an Hochschulen. Diskussion Möglicher Ansatzpunkte und Ihrer Konsequenzen für die Praxis. Universität Lüneburg. 2006. Available online: https://www.leuphana.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Forschungseinrichtungen/infu/files/infu-reihe/33_06.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Sepasi, S.; Braendle, U.; Rahdari, A.H. Comprehensive sustainability reporting in higher education institutions. Soc. Responsib. J. 2019, 15, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassen, R.; Azizi, L. Strategien und Prozesse der Nachhaltigkeitsberichterstattung an Hochschulen in Deutschland. Z. Für Umweltpolit. Umweltr. 2018, 2, 185–219. [Google Scholar]

- Lopatta, K.; Jaeschke, R. Sustainability reporting at German and Austrian universities. Int. J. Educ. Econ. Dev. 2014, 5, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siboni, B.; Del Sordo, C.; Pazzi, S. Sustainability Reporting in State Universities: An Investigation of Italien Pioneering Practices. Int. J. Soc. Ecol. Sustain. Dev. (IJSESD) 2013, 4, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Salvia, A.L.; Eustachio, J.H.P.P. An overview of the engagement of higher education institutions in the implementation of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 386, 135694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallah Shayan, N.; Mohabbati-Kalejahi, N.; Alavi, S.; Zahed, M.A. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as a Framework for Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). Sustainability 2022, 14, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Almeida, M.D.M.; Marimon, F.; Casani, F.; Rodríguez-Pomeda, J. Diffusion of sustainability reporting in universities: Current situation and future perspectives. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 106, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhao, D.; Cao, Y.; Xu, C. New trends in sustainability reporting: Exploring the online sustainability reporting practices by Irish universities. J. Innov. Knowl. 2024, 9, 100529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bais, B.; Nassimbeni, G.; Orzes, G. Global Reporting Initiative: Literature review and research directions. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 471, 143428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Global Compact Questionnaire Guidebook. Communication on Progress 2024. Available online: https://www.globalcompact.de/fileadmin/user_upload/UNGC_CoP_GuideBook_2023_Feb.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Sammalisto, K.; Brorson, T. Training and Communication in the Implementation of Environmental Management Systems (ISO 14001): A Case Study at the University of Gävle, Sweden. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disterheft, A.; Ferreira da Silva Caeiro, S.; Rosario Ramos, M.; De Miranda Azeiteiro, U. Environmental Management Systems (EMS) implementation processes and practices in European higher education institutions—Top-down versus participatory approches. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 31, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European University Association (EUA). Sustainability. 2023. Available online: https://www.eua.eu/our-work/topics/sustainability.html (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- European University Association (EUA). Sustainability in Higher Education: A European Perspective. 2025. Available online: https://www.enqa.eu/wp-content/uploads/1.3-Plenary1_Sustainability-in-HE_EUA.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- AASHE. Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education. STARS Technical Manual Version 3.0. 2024. Available online: https://stars.aashe.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/STARS-Technical-Manual-v3.0.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Rat für Nachhaltige Entwicklung. Leitfaden zum Deutschen Nachhaltigkeitskodex. 2020. Available online: https://www.deutscher-nachhaltigkeitskodex.de/media/wxvchuff/rne_dnk_leitfaden_2020-1.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- HochN. Operational Sustainability in Higher Education. 2022. Available online: https://www.dg-hochn.de/startpage (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Quacquarelli Symonds. QS World University Rankings: Sustainability 2025. 2025. Available online: https://www.topuniversities.com/sustainability-rankings (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Principles for Responsible Management Education (PRME). PMRE Annual Report 2023. 2023. Available online: https://www.unprme.org/resources/2023-prme-annual-report/ (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Times Higher Education. University Impact Rankings 2024. 2024. Available online: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/rankings/impact/overall/2024 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Ankareddy, S.; Dorfleitner, G.; Zhang, L.; Ok, Y. Embedding sustainability in higher education institutions: A review of practices and challenges. Clean. Environ. Syst. 2025, 17, 100279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rat für Nachhaltige Entwicklung. Der Hochschulspezifische Nachhaltigkeitskodex. 2018. Available online: https://www.deutscher-nachhaltigkeitskodex.de/media/nampl4zr/2018-05-15-hs-dnk.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- STARS. The Sustainability Tracking, Assessment & Rating System. Available online: https://stars.aashe.org/about-stars/ (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- CSEAR. Creating a Sustainable World Through Accounting Research, Engagement and Education. Available online: https://csear.co.uk (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Brusca, I.; Labrador, M.; Larran, M. The challenge of sustainability and integrated reporting at universities: A case study. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 188, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Rosa, M.R.; Boscarioli, C.; Regina de Freitas Zara, K. A systematic review of the trends and patterns of sustainability reporting in universities. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2024, 25, 556–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Reporting Initiative. The Global Standards for Sustainability Impacts. 2025. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/standards/ (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Nikolaou, I.E.; Tsalis, T.A.; Skouloudis, A.; Malesios, C. Sustainability reporting in universities: A content analysis of SDG orientation. Stud. High. Educ. 2023, 48, 2234–2252. [Google Scholar]

- Rieckmann, M.; Giesenbauer, B.; Nölting, B.; Potthast, T.; Schmitt, C.T. Nachhaltige Entwicklung von Hochschulen. Erkenntnisse und Perspektiven zur Gesamtinstitutionellen Transformation; Verlag Barbara Budrich: Leverkusen, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, C.A. Sustainability reporting and performance management in universities: Challenges and benefits. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2013, 4, 384–392. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano, R. A tool for a graphical assessment of sustainability in universities (GASU). J. Clean. Prod. 2006, 14, 963–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R.; Llobet, J.; Tideswell, G. The process of assessing and reporting sustainability at universities: Preparing the report of the university of Leeds. Rev. Int. Sostenibilidad. Tecnol. Humanismo 2013, 8, 85–113. [Google Scholar]

- Moudrak, N.; Clarke, A. Developing a first-time sustainability report for a higher education institution. In Sustainable Development at Universities: New Horizons; Filho, W.L., Ed.; Peter Lang Scientific Publishers: Frankfurt, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Del Sordo, C.; Farneti, F.; Guthrie, J.; Pazzi, S.; Siboni, B. Social reports in Italian universities: Disclosures and preparers’ perspective. Meditari Account. Res. 2016, 24, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorio-Grima, A.; Sierra-Garcia, L.; Garcia-Benau, M.A. Sustainability Reporting Experience by Universities: A Causal Configuration Approach. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2018, 19, 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Bolívar, M.P.; Garde Sánchez, R.; López Hernández, A.M. Online disclosure of corporate social responsibility information in leading Anglo-American universities. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2013, 15, 551–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isenmann, R.; Sassen, R.; Zinn, S. Digitalisierung und IKT in der Nachhaltigkeitsberichterstattung von Hochschulen in Deutschland—Terra Incognita? Lecture Notes in Informatics (LNI); Cunningham, D., Hofstedt, P., Meer, K., Schmitt, I., Eds.; Gesellschaft für Informatik: Bonn, Germany, 2015; pp. 469–482. [Google Scholar]

- EFRAG 2024a Cover Letter. December. 2024. Available online: https://www.efrag.org/system/files/sites/webpublishing/Project%20Documents/2309261112573240/EFRAG%20Cover%20Letter%20for%20the%20VSME.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- EFRAG. EFRAG Releases the Voluntary Sustainability Reporting Standard for Nonlisted SMEs (VSME); EFRAG: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Linklaters. European Commission Adopts Recommendation on Voluntary Sustainability Reporting Standard for SMEs. Sustainable Futures 2025. Available online: https://sustainablefutures.linklaters.com (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Isip, A. Recent Perspectives on Outsourcing of Sustainability Reporting. 2023. Available online: https://www.icess.ase.ro/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Recent-Perspectives-on-Outsourcing.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Sayed, M.; Hendry, L.C.; Zorzini Bell, M. Sustainable procurement: Comparing inhouse and outsourcing implementation modes. Prod. Plan. Control 2021, 32, 145–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SDSN. Our Networks. 2025. Available online: https://www.unsdsn.org/our-networks/ (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Urbanski, M.; Filho, W. Measuring Sustainability at Universities by Means of the Sustainability Trackingm Assessment and Rating System (STARS): Early Findings from STARS Data; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; Volume 17, pp. 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Higher Education Sustainability Initiative. 2025. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/HESI? (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- ISCN. Sustainable Reporting Working Group. 2021. Available online: https://international-sustainable-campus-network.org/communities-of-practice/sustainability-reporting-working-group/ (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- AASHE. Sustainable Campus Index. 2024. Available online: https://www.aashe.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/2024-SCI.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Hassan, M.; Ahmad, A. Systematic literature review on the sustainability of higher education institutions (HEIs): Dimensions, practices and research gaps. Cogent Educ. 2025, 12, 2549789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diekmann, A. Empirische Sozialforschung: Grundlagen, Methoden, Anwendungen, 13th ed.; Rowohlt Verlag: Reinbek, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Häder, M. Empirische Sozialforschung: Eine Einführung, 4th ed.; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchmair, R. Qualitative Forschungsmethoden: Anwendungsorientiert: Vom Insider aus der Marktforschung Lernen; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Grundlagen und Techniken, 12th ed.; Verlagsgruppe Beltz: Weinheim, Germany; Basel, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Schaebs, D.S. Nachhaltigkeitsberichterstattung an Staatlichen Hochschulen: Qualitative Untersuchung Eines Rechtlich und Freiwillig Motivierten Reportings; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, R. Qualitative Experteninterviews: Konzeptionelle Grundlagen und Praktische Durchführung; Springer VS: Weinheim, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bogner, A.; Littig, B.; Menz, W. Interviews mit Experten: Eine Praxisorientierte Einführung; Springer VS: Weinheim, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Quast, C. Was Sind Experten? Eine Begriffliche Grundlegung; Campus Verlag GmbH: Frankfurt, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hochschulrektorenkonferenz. Hochschulen in Zahlen 2024. 2024. Available online: https://www.hrk.de/fileadmin/redaktion/hrk/02-Dokumente/02-06-Hochschulsystem/Statistik/2024-08-28_HRK-Statistikfaltblatt-2024.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Bundeskanzleramt. Liste der Fachhochschulen in Österreich. 2025. Available online: https://www.oesterreich.gv.at/themen/bildung_und_ausbildung/hochschulen/fachhochschulen/Seite.810400.html#:~:text=Derzeit%20gibt%20es%20in%20%C3%96sterreich%2021%20Fachhochschulen (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Statistik Austria. Hochschulstatistik. 2025. Available online: https://www.statistik.at/statistiken/bevoelkerung-und-soziales/bildung/studierende-belegte-studien? (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Meuser, M.; Nagel, U. ExpertInneninterviews—Vielfach Erprobt, Wenig Bedacht. Ein Beitrag zur Qualitativen Methodendiskussion. In Experteninterviews, 2nd ed.; Bogner, A., Littig, B., Menz, W., Eds.; Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2009; pp. 465–480. [Google Scholar]

- Gläser, J.; Laudel, G. Experteninterviews und Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse, 4th ed.; VS Verlag: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Meyen, M.; Löblich, M.; Pfaff-Rüdiger, S.; Riesmeyer, C. Qualitative Forschung in der Kommunikationswissenschaft: Eine Praxisorientierte Einführung; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Döring, N.; Bortz, J. Forschungsmethoden und Evaluation in den Sozial- und Humanwissenschaften, 5th ed.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. Grundlagen und Techniken, 13th ed.; Verlagsgruppe Beltz: Weinheim, Germany; Basel, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, U. Qualitative Sozialforschung: Eine Einführung; Rowohlt Verlag: Reinbek, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kuckartz, U. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Methoden, Praxis, Computerunterstützung; Beltz Juventa: Weinheim, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Abello-Romero, J.; Mancilla, C.; Restrepo, K.; Sáez, W.; Durán-Seguel, I.; Ganga-Contreras, F. Sustainability Reporting in the University Context—A Review and Analysis of the Literature. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yáñez, S.; Uruburu, A.; Moreno, A.; Lumbreras, J. The sustainability report as an essential tool for holistic approach in HEIs. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 207, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaou, I.I.; Tsalis, T.A.; Trevlopoulos, N.S.; Mathea, A.; Avlogiaris, G.; Vatalis, K.I. Exploring the sustainable reporting practices of universities in relation to the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for sustainable development. Discov. Sustain. 2023, 4, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauro, S.G.; Cinquini, L.; Simonini, E.; Tenucci, A. Moving from Social and Sustainability Reporting to Integrated Reporting: Exploring the Potential of Italian Public-Funded Universities’ Reports. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Tullio, P.; La Torre, M. Sustainability reporting at a crossroads in universities: Is web-based media adoption deinstitutionalising sustainability reporting? Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PwC. Not-for-Profit Entities. 2025. Available online: https://viewpoint.pwc.com/dt/us/en/pwc/accounting_guides/not-for-profit-entities/assets/pwcnotforprofitguide0525.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Fachhochschule Burgenland GmbH. Der erste Bericht als Verpflichtung zur Nachhaltigkeit. 2024. Available online: https://hochschule-burgenland.at/fileadmin/user_upload/PDFs/Nachhaltigkeit/01_240057_Nachhaltigkeitsbericht_A4_V10_Screen.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Fachhochschule Burgenland GmbH. Nachhaltigkeitsstrategie Fachhochschule Burgenland-Gruppe. Kurzfassung. 2021. Available online: https://hochschule-burgenland.at/fileadmin/user_upload/PDFs/Nachhaltigkeit/Nachhaltigkeitsstrategie_2021_Kurzfassung.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- FH Campus Wien University of Applied Sciences. Strategie 2025. 2025. Available online: https://portal.fh-campuswien.ac.at/webservices/portaltoenabler/enablergetdocument.aspx?id=2097 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Republic of Austria. Austria and the 2030 Agenda: Austrian Voluntary National Review—Report on the Implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals, 2nd ed.; Sustainable Development Goals: New York, NY, USA, 2024; Implementation of the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs; Available online: https://www.bundeskanzleramt.gv.at/dam/jcr:87c1e200-7bc5-4e2b-89d8-8367988a28ff/austria-second-vnr-2024.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Hochschule Mittweida. Klima- und Umweltschutz an der Hochschule Mittweida. Integriertes Klimaschutzkonzept. 2022. Available online: https://www.ifem-mittweida.de/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/Vorstellung-KSM-der-HSMW-2025_.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Freistaat Sachsen. Nachhaltigkeitsstrategie für den Freistaat Sachsen. 2018. Available online: https://publikationen.sachsen.de/bdb/artikel/33120/documents/57955 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Fachhochschule Südwestfalen. University of Applied Sciences. Nachhaltigkeitsverständnis der Fachhochschule Südwestfalen. 2023. Available online: https://www.fh-swf.de/media/neu_np/hv_nachhaltigkeit/extern_6/Nachhaltigkeitsverstandnis_Fachhochschule_Suedwestfalen.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- NRW. Die Globalen Nachhaltigkeitsziele Konsequent Umsetzen. Weiterentwicklung der Strategie für ein Nachhaltiges Nordrhein-Westfalen. 2020. Available online: https://nachhaltigkeit.nrw.de/fileadmin/Dokumente/NRW_Nachhaltigkeitsstrategie_2020.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- European Commission. SME Relief Package. 2023. Available online: https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/document/download/8b64cc33-b9d9-4a73-b470-8fae8a59dba5_en?filename=COM_2023_535_1_EN_ACT_part1_v12.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Hamilton, S.N.; Waters, R.D. Mainstreaming Standardized Sustainability Reporting: Comparing Fortune 50 Corporations’ and U.S. News & World Report’s Top 50 Global Universities’ Sustainability Reports. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassen, R.; Dienes, D.; Beth, C. Nachhaltigkeitsberichterstattung deutscher Hochschulen. Z. Für Umweltpolit. Umweltr. (ZfU) 2014, 37, 258–277. [Google Scholar]

- Andrades, J.; Martinez-Martinez, D.; Larrán, M. Sustainability reporting, institutional pressures and universities: Evidence from the Spanish setting. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2025, 16, 1045–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, E.; Roberts, R. Sustainability and impact reporting in US higher education anchor institutions. J. Account. Lit. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Goiria, J.; Sianes, A. Reporting the social value generated by European universities for stakeholders: Applicability of the GRI model. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 787385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertelsmann Stiftung. Sustainability Transformation Monitor 2024. 2024. Available online: https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/fileadmin/files/PicturePark/2024-02/W_Studie_Sustainability_Transformation_Monitor_2024.pdf? (accessed on 20 October 2025).

| Reporting Standard/Framework & Main Objective | Scope & Structure | Use in European Universities |

|---|---|---|

| Global Reporting Initiative (GRI)—comprehensive, comparable ESG reporting for all stakeholders | Broad coverage (economic, environmental, social, governance); modular structure; focused on materiality and stakeholder engagement. Sometimes considered ‘too corporate’ for academia but adaptable; serves as the foundation for many hybrid models (e.g., GRI + SDG + AA1000). | Widely used in Spain, Ireland, the UK, Germany, and the Nordic countries. Mainly public and research-intensive universities [39,40,41]. |

| SDG-linked reporting—demonstrating contribution to the UN Sustainable Development Goals | Cross-cutting approach linking research, teaching, campus operations, and outreach to the 17 SDGs. Used as a narrative and strategic framework, often combined with GRI indicators. | Almost all reporting universities apply SDG mapping; standard approach in European University Association (EUA) and national sustainability initiatives. All university types [39,40]. |

| Integrated Reporting (<IR> Framework)—linking financial and non-financial value creation | Structure: strategy, governance, performance, and outlook; based on six ‘capitals’. Complements GRI by emphasizing strategic and long-term value creation. | Selective adoption in the UK and Northern Europe; primarily large, research- and management-oriented universities [39,41]. |

| AA1000 (AP/SES/AS)—ensuring credible stakeholder engagement and assurance | Principles-based (inclusivity, materiality, responsiveness, impact). Not a topic-based framework but a process and quality tool to complement other standards. | Applied occasionally (Spain, UK) to strengthen quality assurance of GRI/SDG reports. Public universities with strong stakeholder engagement [39,41]. |

| UN Global Compact (CoP)—reporting progress on 10 principles (human rights, labour, environment, anti-corruption) | Narrative progress reports; ethical and normative focus. Serves as a value-based complement to GRI. | Moderate use among European United Nations Global Compact (UNGC) member universities (mainly business and management schools) [41,42]. |

| ISO 14001 (Environmental Management System)—environmental management and certified improvement | System-oriented (Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle); focuses on environmental performance, compliance, and continuous improvement. Not a reporting framework, but provides indicators for environmental sections in reports. | Common in the UK, Germany, and Nordic countries; applied by technical and public universities [40,43,44]. |

| National and regional frameworks (e.g., EAUC UK, French CSR Charter, EUA Guidelines, AUHEP Australia, Hochschul-DNK Germany)—sectoral harmonisation | Based on GRI/SDG indicators and adapted to HE-specific missions (education, research, governance). Promote comparability and accountability within national university networks. Includes the Hochschul-DNK (German Sustainability Code for Universities), structured around 20 criteria (strategy, process management, environment, society) plus higher education indicators. Compatible with GRI and SDGs. | Implemented in the UK, France, Australia, and Germany. The Hochschul-DNK is widely used by German universities, universities of applied sciences, and colleges [45,46,47,48,49]. |

| AASHE STARS (Sustainability Tracking, Assessment & Rating System)—performance benchmarking for higher education | HE-specific scoring system covering academics, engagement, operations, and planning & administration. Produces a public Bronze–Platinum rating; not a reporting standard but widely used for transparency and benchmarking. | Most popular in North America; increasing adoption in Australia and some European HEIs. Applicable to all types of institutions [41,47]. |

| QS Sustainability Rankings Framework—comparative global index for HE sustainability performance | Weighted scorecard across environmental impact, social impact, and governance indicators. Data-driven assessment integrating SDG dimensions. | Rapidly expanding globally; mainly used for reputational benchmarking and international visibility [50]. |

| PRME (Principles for Responsible Management Education)—business school–specific sustainability integration | Framework for integrating UNGC principles and SDGs into curricula, research, and operations. Designed for management and business schools; emphasizes ethics and responsible leadership. | Widely used globally; signatory schools publish annual Sharing Information on Progress (SIP) reports [41,51]. |

| Times Higher Education (THE) Impact Ranking Metrics—global performance-based sustainability benchmarking | Ranking methodology measuring universities’ contribution to SDGs using research, teaching, and outreach indicators. Combines quantitative metrics with self-reported data. | Used globally by over 1500 universities; complement to reporting frameworks; not a standard per se [52]. |

| Criterion | In-House Solution | Outsourcing Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Control & Governance | Full control over content, data, and strategic alignment | Less direct control; risk of communication issues |

| Organisational Issues | Builds internal know-how and learning, awareness, and embeds sustainability culturally with committee work and good institutionalisation | Learning and development processes partly ‘outsourced’ |

| Resource Requirements | High staff and time investment; need to build expertise | Relieves internal resources; lower staff requirements, dependence on data flows/data transfer points |

| Costs | Potentially cheaper in the long term, but high fixed costs for staff & processes/IT | Clear cost calculation; often cheaper short term, but dependency on external providers |

| Expertise | Depends on internal know-how, which may be limited | Access to specialized knowledge, best practices, and reporting tools |

| Credibility | May be perceived as less independent externally | External providers or assurance can increase credibility |

| Flexibility & Scalability | Adjustments take time and require internal coordination | External providers can scale more quickly, with lean processes and offer additional services |

| Data Protection & Confidentiality | Data stays internal and under control | Risk of data protection issues or lack of customization |

| Expert | Name and Country | Legal Form | Key Data | Position |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E1 | Leipzig University of Applied Sciences (HTWK) [Germany] | Public | 6431 students, 6 departments, 629 employees, 44 degree programmes | Vice-Rector for Research and Sustainability |

| E2 | University of Applied Sciences Mittweida [Germany] | Public | 6094 students, 5 departments, 495 employees, 58 degree programmes | Climate protection manager |

| E3 | University of Applied Sciences Südwestfalen [Germany] | Public | 10,479 students, 9 departments, 938 employees, 70 degree programmes | Head of the Sustainability Unit |

| E4 | University of Applied Sciences Burgenland [Austria] | Public | 2840 students + 5573 distance learning students, 4 departments, 973 employees, 70 degree programmes | Head of the Sustainability Unit |

| E5 | University of Applied Sciences St. Pölten [Austria] | Public | 3552 students + 459 distance learning students, 504 employees, 29 degree programmes | Sustainability Coordinator |

| E6 | University of Applied Sciences Vienna (WKW) [Austria] | Public | 2876 students + 500 distance learning students, 193 employees, 27 degree programmes | Head of Competence Center for Sustainability |

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| Resource efficiency | Coordination efforts |

| Standardisation and comparability | Heterogenity issues |

| Transparency and visibility | Data quality and availability |

| Flexibility and individuality | Dependency and sovereignty |

| Accessibility and peer learning | Basic resource requirements |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Biloslavo, R.; Schaebs, D.S. Joint Sustainability Reports (JSRs) to Promote the Third Mission of Universities. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9587. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219587

Biloslavo R, Schaebs DS. Joint Sustainability Reports (JSRs) to Promote the Third Mission of Universities. Sustainability. 2025; 17(21):9587. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219587

Chicago/Turabian StyleBiloslavo, Roberto, and Daniel Simon Schaebs. 2025. "Joint Sustainability Reports (JSRs) to Promote the Third Mission of Universities" Sustainability 17, no. 21: 9587. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219587

APA StyleBiloslavo, R., & Schaebs, D. S. (2025). Joint Sustainability Reports (JSRs) to Promote the Third Mission of Universities. Sustainability, 17(21), 9587. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219587