Co-Opetition as a Pathway to Sustainability: How Bed and Breakfast Clusters Achieve Competitive Advantage in High-Density Tourism Destinations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Current Status and Development Trends of B&Bs in China

2.2. Co-Opetition Theory

2.3. Inter-Firm Co-Opetition Relationships

2.4. Co-Opetition Among B&Bs

2.5. SCA

3. Research Methodology

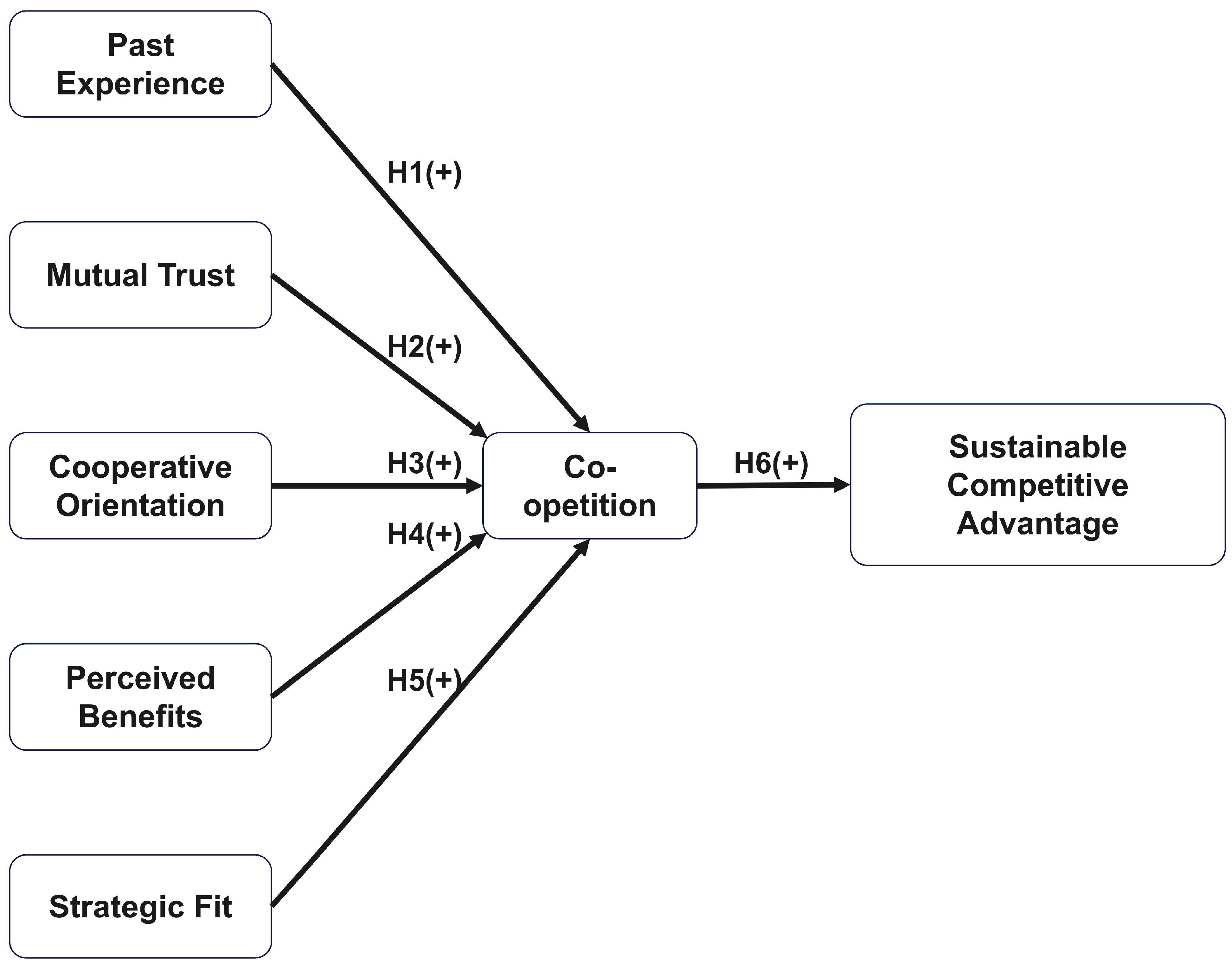

3.1. Hypotheses and Conceptual Model

3.2. Research Design

3.3. Questionnaire Design and Variable Measurement

3.4. Data Collection

3.5. Reliability and Validity Test

- (1)

- Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA): EFA was conducted using SPSS 26.0. The results showed that all variables had Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) values above 0.6, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (p < 0.05), confirming the suitability of the data for factor analysis. Following the loading threshold of >0.6, one item (CE2) was removed. All other items met the standard. The variance explained by each latent variable either met or closely approached the acceptable level; for instance, the explained variance for SCA was 57.615%, close to the 60% benchmark (Table 1).

- (2)

- Reliability Testing: Internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha. All constructs had alpha values greater than 0.7, indicating strong internal reliability.

- (3)

- Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA): CFA was conducted using AMOS 23.0 to evaluate convergent validity. Two items (CP1 and SCA3) were removed due to low standardized loadings. The remaining items all showed loadings >0.6, composite reliability (CR) > 0.7, and average variance extracted (AVE) > 0.5, meeting the criteria for convergent validity. Model fit indices were acceptable: χ2/df = 3.007, RMR = 0.034, RMSEA = 0.072, CFI = 0.922, and NFI = 0.888 (Table 1).

- (4)

- Discriminant Validity Analysis: Discriminant validity was tested using the Fornell-Larcker criterion. The square roots of the AVE values for all constructs exceeded the corresponding inter-construct correlations, supporting discriminant validity. Although a few indicators were near boundary levels, which may be attributed to data characteristics, the overall discriminant validity remained acceptable (Table 2).

3.6. Data Analysis Techniques

- (1)

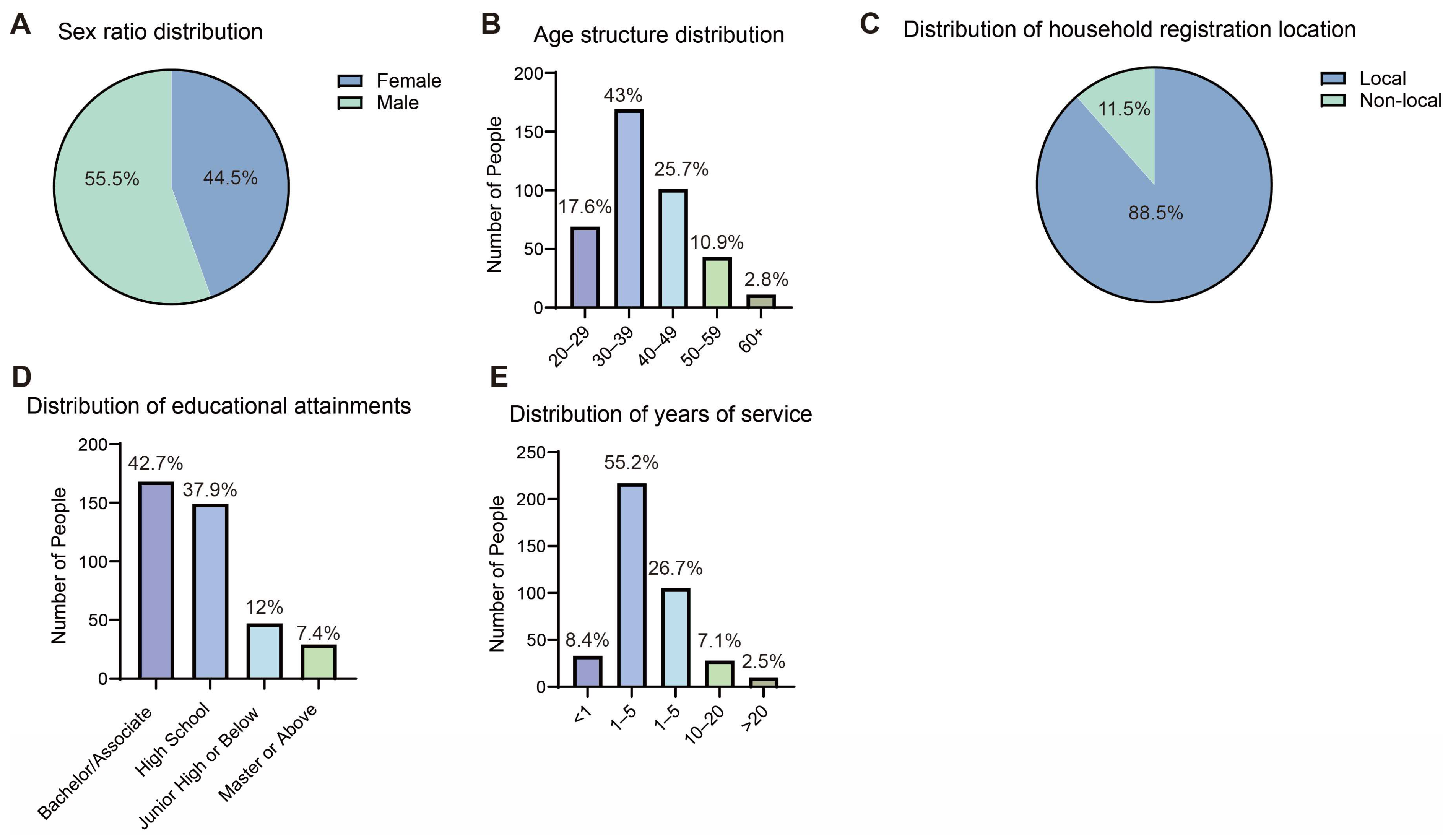

- Descriptive Statistics: Descriptive statistics were conducted using SPSS 26.0 to analyze sample characteristics, including gender, age, educational background, household registration, and work experience. Results were reported as frequencies and percentages.

- (2)

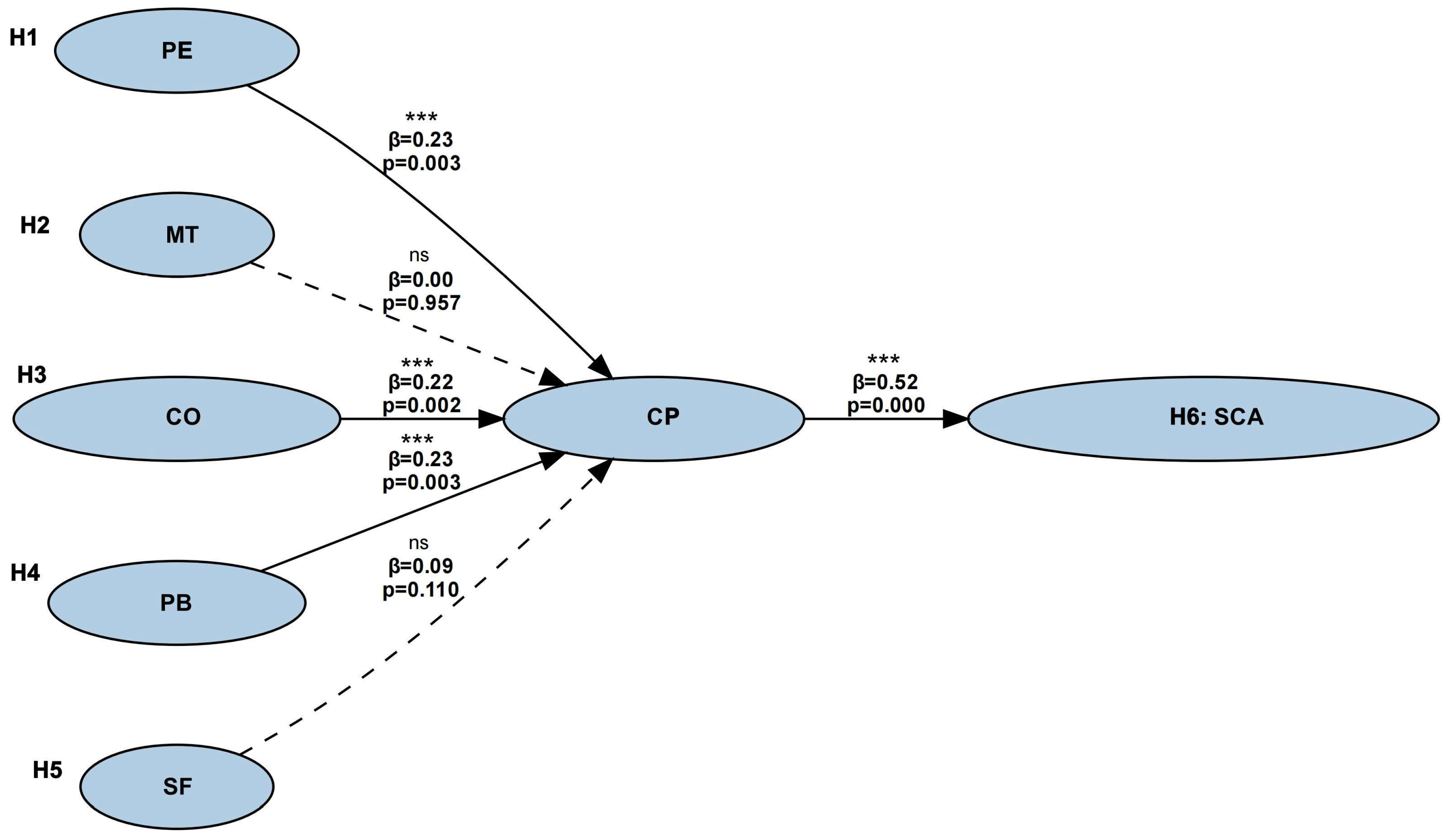

- SEM: SEM was performed using AMOS 23.0 to test the theoretical model and hypotheses. SEM is appropriate for analyzing complex relationships among multiple latent variables, consistent with the aim of this study to explore interconnections among constructs. Parameters were estimated using the maximum likelihood (ML) method. The SEM analysis was conducted in two steps. First, overall model fit was assessed using indices such as the χ2/df, RMSEA, CFI, and NFI. The recommended thresholds were: χ2/df < 3, RMSEA < 0.08, and CFI and NFI > 0.90. Model fitting was adjusted based on modification indices (MI) and theoretical considerations, adding covariances between measurement error terms to capture residual associations. Each adjustment released a single parameter followed by re-evaluation, all changes supported by theory to avoid overfitting. After two adjustments (MI > 10, release of two pairs of error covariances), fit indices reached acceptable levels (χ2/df = 2.85, RMSEA = 0.068, CFI = 0.936, NFI = 0.901), indicating good model-data fit. Second, the hypothesized paths (H1–H6) were evaluated through path coefficients, with statistical significance determined at the p < 0.05 level.

4. Results

4.1. Structural Characteristics of B&B Operators in the Moganshan Region

4.2. SEM Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

6.2. Managerial Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AVE | Average Variance Extracted |

| B&B | Bed and Breakfast |

| CFA | Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index |

| CO | Cooperation Orientation |

| CP | Coopetition Behavior |

| CR | Composite Reliability |

| EFA | Exploratory Factor Analysis |

| KMO | Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin |

| ML | Maximum Likelihood |

| MT | Mutual Trust |

| NFI | Normed Fit Index |

| PB | Perceived Benefit |

| PE | Prior Experience |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

| RMR | Root Mean Square Residual |

| SCA | Sustainable Competitive Advantage |

| SEM | Structural Equation Modeling |

| SF | Strategic Fit |

| SMEs | Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises |

| χ2/df | Chi-Square to Degrees of Freedom Ratio |

Appendix A. Variable Measurement Scales

| Construct Name & Source | Indicator | Survey Item |

|---|---|---|

| Past Experience | PE1 | Had good relationships with other homestays. |

| PE2 | Had prior cooperation with other homestays. | |

| PE3 | Had effective cooperation with other homestays in the past. | |

| PE4 | Past cooperation experience encourages me to actively consider future collaboration opportunities. | |

| Mutual Trust | MT1 | Information is mutually open when dealing with partners. |

| MT2 | The mutual commitments between me and my partners are reliable. | |

| MT3 | My partners and I do not make false statements. | |

| Cooperative Orientation | CO1 | Believe in the importance of cooperating with competitors. |

| CO2 | Cooperation with competitors is “effective.” | |

| CO3 | Cooperation with competitors is critical. | |

| CO4 | Have a mindset focused on cooperation with competitors. | |

| Perceived Benefits | PB1 | Through cooperation, my partners and I have gained competitive advantages. |

| PB2 | Through cooperation, my partners and I have improved our market positions. | |

| PB3 | Through co-opetition, my B&B improved existing capabilities and created more value than partners. | |

| PB4 | Through co-opetition, my B&B improved products/services and created more value than partners. | |

| Strategic Fit | SF1 | My partners and I have aligned goals. |

| SF2 | My partners and I support each other’s goals. | |

| SF3 | My partners and I develop business objectives together. | |

| Co-opetition | CO1 | My partners and I engage in intense competition. |

| CO2 | I engage in broad cooperation with competitors. | |

| CO3 | Cooperation with competitors to achieve shared goals. | |

| CO4 | Active competition with partners is important. | |

| Sustainable Competitive Advantage | SCA1 | Gained strategic advantage through co-opetition. |

| SCA2 | Overall, more successful than major competitors. | |

| SCA3 | Possess management ability to absorb new knowledge from partners. | |

| SCA4 | Entered new markets in the past three years. | |

| SCA5 | Entered new markets in the past three years. | |

| SCA6 | Expanded product range in the past three years. |

Appendix B. Demographic Information

- Your Gender:□ Male□ Female

- Your Age:□ 20–29 years□ 30–39 years□ 40–49 years□ 50–59 years□ 60 years and above

- Your Place of Household Registration:□ Local□ Non-local

- Your Highest Level of Education:□ Junior high school or below□ Senior high school or vocational school□ College diploma or bachelor’s degree□ Master’s degree or above

- Years of Experience in the B&B Industry:□ Less than 1 year□ 1–5 years□ 5–10 years□ 10–20 years□ More than 20 years

References

- Bengtsson, M.; Kock, S. “Coopetition” in Business Networks—To Cooperate and Compete Simultaneously. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2000, 29, 411–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouncken, R.B.; Fredrich, V. Good fences make good neighbors? Directions and safeguards in alliances on business model innovation. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5196–5202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Corte, V.; Aria, M. Coopetition and sustainable competitive advantage. The case of tourist destinations. Tour. Manag. 2016, 54, 524–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; He, J. Horizontal Tourism Coopetition Strategy for Marketing Performance—Evidence From Theme Parks. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 917435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Q.; Chen, J.; Zheng, Y. Assessing the impact of community-based homestay experiences on tourist loyalty in sustainable rural tourism development. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Sun, H.; Wang, Z.; Sun, L.; Shao, Q. Investigating the determinants of homestay satisfaction on Airbnb using multiple techniques. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 24146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Chen, D.; Bi, J.-W.; Lyu, J.; Li, Q. The construction of the affinity-seeking strategies of Airbnb homestay hosts. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 861–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maracajá, K.F.B.; Chim-Miki, A.F.; da Costa, R.A. Status and dimensions of research on coopetition in wine tourism. Rural. Soc. 2025, 34, 62–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czakon, W.; Klimas, P.; Mariani, M. Behavioral antecedents of coopetition: A synthesis and measurement scale. Long Range Plan. 2020, 53, 101875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R. Formation Mechanism, Development Challenges, and Path Selection of Rural Tourism Homestay Clusters. 2018. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0024630117305496 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Qian, Y.; Zhu, H.; Wu, J. Understanding the determinants of where and what kind of home accommodation to build. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Xu, L. Unraveling the dynamics of bed and breakfast clusters development: A multiscale analysis. Appl. Geogr. 2024, 169, 103320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sbai, Y. Homestay Tourism Research: A Systematic Literature Review. Rev. Études Multidiscip. Sci. Économiques Soc. 2024, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riquelme-Medina, M.; Stevenson, M.; Barrales-Molina, V.; Llorens-Montes, F.J. Coopetition in business Ecosystems: The key role of absorptive capacity and supply chain agility. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 146, 464–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, N.; Kumar, R.; Malik, A. Global developments in coopetition research: A bibliometric analysis of research articles published between 2010 and 2020. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 145, 495–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorn, S.; Schweiger, B.; Albers, S. Levels, phases and themes of coopetition: A systematic literature review and research agenda. Eur. Manag. J. 2016, 34, 484–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gernsheimer, O.; Kanbach, D.K.; Gast, J. Coopetition research—A systematic literature review on recent accomplishments and trajectories. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2021, 96, 113–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomason, S.J.; Simendinger, E.; Kiernan, D. Several determinants of successful coopetition in small business. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2013, 26, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrich, V.; Bouncken, R.B.; Kraus, S. The race is on: Configurations of absorptive capacity, interdependence and slack resources for interorganizational learning in coopetition alliances. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 101, 862–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crick, J.M.; Crick, D. Rising up to the challenge of our rivals: Unpacking the drivers and outcomes of coopetition activities. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2021, 96, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, H. Research on the Transformation and Upgrading of Mountain Dwelling Style Farmhouse Accommodation Based on Incentive Policy Innovation: A Case Study of Lishui. 2019. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/doi/10.13395/j.cnki.issn.1009-0061.2019.10.019 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Yu, J.L.; Ling, L.; Li, J. Research on the Agglomeration Characteristics and Mechanisms of Lin’an Homestays Based on the Niche Theory. 2020, pp. 74–86. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=X-VFCYicIZuZKcUOo8ZEL6zXNkY768BVwBQJBcKh54UWUe_1dKshcYrUnhPIeWj0r5f0AnIP59O5d94bFRt80i0DIiEwuXswcDHXNM96Kp5ALbi-pcjM5wtSEZ-_g6of1lifwulm09brmTcwmLXYTplQ-yCDrcKPxnYJd0X3-Tknkv1dW47jqA==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Jiang, X.W. Research on Moganshan Homestay Based on Cooperation and Competition Strategy. 2017, p. 180. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=X-VFCYicIZstZGOPcWUzttebpIOu5w0Nom2kuXA5hYO2Po-2SJRyF6yJEKB0eS2vfPwf_OcIcHDZMoxKPUrwCSzK0cGDYcrmi9mGfNn8Rh2mGbM1qR01gTC7zRkqXolBt7HC_acOzMiXdbBe9f3lEUgqHZ3OEKyRrbB_T7q9U9htgXHMzwUAUQ==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; Shi, Y. The Influence of Cluster Social Capital on The Growth of Rural Homestay Inns: The Case of Two Villages in Mount Danxia; Jinan University: Guangzhou, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ritala, P.; Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, P. What’s in it for me? Creating and appropriating value in innovation-related coopetition. Technovation 2009, 29, 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdi, O.R.; Nassar, I.A.; Almsafir, M.K. Knowledge management processes and sustainable competitive advantage: An empirical examination in private universities. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 94, 320–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. Research on the Branding and Clustering Development Strategies of Rural Homestays in Harbin. 2020. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=YNWfVykhE0bhL1GkSTnuurlUWeyvUYcumQfC2uRu8I8uKLeq8uCOilMvgOPM39wMv-hLnKTBlrDSJ3jJKu780CYt1DYq5jLeedmPaC_-eN36OfrZltW-1YHAc9qmXMFYfpcCW7cO9jhwuLIA4bQMe_pRLZeCkeYZuUR7Fly6XRGCcgX3XKA4-Q==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Maury, B. Sustainable competitive advantage and profitability persistence: Sources versus outcomes for assessing advantage. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 84, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, A.; Lim, M.K.; Knight, L. Sustaining competitive advantage in SMEs. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 25, 408–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, S. Determinants of long-term orientation in buyer-seller relationships. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osarenkhoe, A. A study of inter-firm dynamics between competition and cooperation—A coopetition strategy. J. Database Mark. Cust. Strategy Manag. 2010, 17, 201–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, L.; Wang, H.; Yang, Y.; He, W. Promoting resident-tourist interaction quality when residents are expected to be hospitable hosts at destinations. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 46, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, M.; Raza-Ullah, T. A systematic review of research on coopetition: Toward a multilevel understanding. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2016, 57, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallmuenzer, A.; Zach, F.J.; Wachter, T.; Kraus, S.; Salner, P. Antecedents of coopetition in small and medium-sized hospitality firms. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 99, 103076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greven, A.; Fischer-Kreer, D.; Müller, J.; Brettel, M. Inter-firm coopetition: The role of a firm’s long-term orientation. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2022, 106, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalebuf, B.J.; Brandenburger, A.M. Co-opetition. Long Range Plan. 1997, 30, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriazos, A.T. Applied Psychometrics: Sample Size and Sample Power Considerations in Factor Analysis (EFA, CFA) and SEM in General. Psychology 2018, 9, 2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, L.N. “Co-opetition”: A model for multidisciplinary practice. Can. J. Nurs. Res. 1997, 29, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- LeTourneau, B. Co-opetition: An alternative to competition. J. Healthc. Manag. 2004, 49, 81–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosemberg, M.S.; Granner, J.R.; Li, W.V.; Adams, M.; Militzer, M.A. Intervention needs among hotel employees and managers. Work 2022, 71, 1063–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yijun, W. Co-opetition Strategy: The Strategic Transformation Path for Small and Medium-sized Enterprises in the New Era. Yunmeng J. 2018, 39, 67–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteoliva, A.; Garcia-Martinez, J.M.; Calvo-Salguero, A. Perceived Benefits and Costs of Romantic Relationships for Young People: Differences by Adult Attachment Style. J. Psychol. 2016, 150, 931–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanon, M.A. Hotel housekeeping work influences on hypertension management. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2013, 56, 1402–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkhwesky, Z.; Derhab, N.; Elkhwesky, F.F.Y.; Abuelhassan, A.E.; Hassan, H. Hotel employees’ knowledge of monkeypox’s source, symptoms, transmission, prevention, and treatment in Egypt. Travel. Med. Infect. Dis. 2023, 53, 102574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köseoglu, M.A.; Yick, M.Y.Y.; Okumus, F. Coopetition strategies for competitive intelligence practices-evidence from full-service hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 99, 103049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.Q.T.; Johnson, P.; Young, T. Networking, coopetition and sustainability of tourism destinations. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 50, 400–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeTourneau, B. From co-opetition to collaboration. J. Healthc. Manag. 2004, 49, 147–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.; Xi, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, R.T. Co-opetition Relationships and Evolution of the World Dairy Trade Network: Implications for Policy-Maker Psychology. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 632465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrin, D.L.; Dirks, K.T.; Shah, P.P. Direct and indirect effects of third-party relationships on interpersonal trust. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 870–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, D.C.; Liden, R.C. Antecedents of coworker trust: Leaders’ blessings. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 1130–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarbrough, A.K.; Powers, T.L. A resource-based view of partnership strategies in health care organizations. J. Hosp. Mark. Public Relat. 2006, 17, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upadhyay, S.; Weech-Maldonado, R.; Lemak, C.H.; Stephenson, A.; Mehta, T.; Smith, D.G. Resource-based view on safety culture’s influence on hospital performance: The moderating role of electronic health record implementation. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2020, 45, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munten, P.; Vanhamme, J.; Maon, F.; Swaen, V.; Lindgreen, A. Addressing tensions in coopetition for sustainable innovation: Insights from the automotive industry. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 136, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnyawali, D.R.; Park, B.-J. Co-opetition between giants: Collaboration with competitors for technological innovation. Res. Policy 2011, 40, 650–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keen, C.; Lescop, D.; Sanchez-Famoso, V. Does coopetition support SMEs in turbulent contexts? Econ. Lett. 2022, 218, 110762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M. Analysis of the current situation and existing problems in the development of homestays in China. Agric. Technol. 2021, 41, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Cai, J.; Zhang, Y. Rural Community Industry Creation under the Mechanism of Multi Subject Interaction: A Case Study of Moganshan Homestay Industry in Deqing, Zhejiang Province. Lingnan J. Chin. Stud. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Huang, B.G. Promotion Strategies for the Clustering of Homestay Tourism from the Perspective of Rural Revitalization. 2021. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=YNWfVykhE0b_9X5Dp6WA40SOqfXirhhTNQhlmzwMzroUIKGMNAKhPh62SowC69aAWRmIXVv7tDAA1ST3b72z2D4whTgD5DMnVmot18a1QCVXNN2hQCUdcF26iCh8siHQN2qmKXB4IRRH8yC449Bre2FF1yDOHZMrzlmvQQIE4ldQQaIPgpxPPg==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Seepana, C.; Paulraj, A.; Huq, F.A. The architecture of coopetition: Strategic intent, ambidextrous managers, and knowledge sharing. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 91, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.H. The Upgrading Path of the Future Homestay Industry: A Discussion on the Cluster Development Model. 2020. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=YNWfVykhE0aC-l61NcZXokDjGP-pkYSBlLvwlGmswDCCGp3IsO_rlH9WLVmletQ8pW480q4pl33xD1yOa5-A997xivpp-kYN67G4jmKgy4d__1vMiG7fNEPR-o-mUyBaWln8smVpMo4-S0IAjuvSgbG5s3quyoIe-vS6fd57KaFSC1_cC5DPYg==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Wang, J.; Guo, L. Research on the Challenges and Breakthrough Paths of Sustainable Development of Moganshan Homestay. 2020. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/doi/10.19699/j.cnki.issn2096-0298.2020.07.077 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Chen, X.J.; Wang, W.L. Analysis of Social Governance in Homestay Agglomeration Areas: Taking the Moganshan Homestay Agglomeration Area as an Example. 2017. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=YNWfVykhE0Z9xcIQMDuG-G2OIeQ9W7sAOm_EXJKZLjX5RhYEqsnhMoCU8laJ4L6s5IlndP1WY_X7E0ZrXBjEF2B8M4huZDJ-RIQQ_3i5mTjVKdhY5BYomEeP8GCk3oFUJ1rjD1xq6wXgzNPjCGk9PTGkvCr1UqYU5QYwe2GnfgEEwnDEmL1fdw==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 1 August 2025).

| Factor Loading | Explained Variance (%) | Standard | SE | T Value | p | CR | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Past Experience | 77.720 | |||||||

| PE1 | 0.840 | 0.738 | ||||||

| PE3 | 0.903 | 0.868 | 0.067 | 16.588 | *** | 0.861 | 0.675 | |

| PE4 | 0.900 | 0.852 | 0.073 | 16.352 | *** | |||

| Mutual Trust | 80.242 | |||||||

| MT1 | 0.841 | 0.73 | ||||||

| MT2 | 0.929 | 0.895 | 0.063 | 17.414 | *** | 0.883 | 0.719 | |

| MT3 | 0.915 | 0.907 | 0.067 | 17.203 | *** | |||

| Cooperative Orientation | 72.429 | |||||||

| CO1 | 0.823 | 0.74 | ||||||

| CO2 | 0.859 | 0.831 | 0.072 | 16.223 | *** | |||

| CO3 | 0.870 | 0.823 | 0.072 | 15.85 | *** | 0.873 | 0.633 | |

| CO4 | 0.852 | 0.784 | 0.076 | 15.101 | *** | |||

| Perceived Benefits | 73.224 | |||||||

| PB1 | 0.852 | 0.813 | ||||||

| PB2 | 0.847 | 0.784 | 17.538 | 17.538 | *** | |||

| PB3 | 0.867 | 0.798 | 17.484 | 17.484 | *** | 0.878 | 0.643 | |

| PB4 | 0.857 | 0.811 | 17.727 | 17.727 | *** | |||

| Strategic Fit | 74.072 | |||||||

| SF1 | 0.825 | 0.779 | ||||||

| SF2 | 0.879 | 0.804 | 14.881 | 14.881 | *** | |||

| SF3 | 0.878 | 0.79 | 15.231 | 15.231 | *** | 0.826 | 0.613 | |

| Co-opetition | 63.012 | |||||||

| CP1 | 0.627 | |||||||

| CP2 | 0.851 | 0.79 | ||||||

| CP3 | 0.876 | 0.836 | 18.092 | 18.092 | *** | 0.816 | 0.599 | |

| CP4 | 0.798 | 0.688 | 14.069 | 14.069 | *** | |||

| Sustainable Competitive Advantage | 57.615 | |||||||

| SCA1 | 0.761 | 0.707 | ||||||

| SCA2 | 0.758 | 0.687 | 12.992 | 12.992 | *** | |||

| SCA3 | 0.719 | |||||||

| SCA4 | 0.789 | 0.739 | 12.582 | 12.582 | *** | 0.853 | 0.539 | |

| SCA5 | 0.794 | 0.757 | 12.387 | 12.387 | *** | |||

| SCA6 | 0.817 | 0.778 | 12.439 | 12.439 | *** |

| SF | PB | CO | MT | PE | CP | SCA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF | 0.783 | ||||||

| PB | 0.877 | 0.802 | |||||

| CO | 0.611 | 0.705 | 0.795 | ||||

| MT | 0.725 | 0.713 | 0.668 | 0.848 | |||

| PE | 0.652 | 0.704 | 0.759 | 0.753 | 0.821 | ||

| CP | 0.784 | 0.838 | 0.763 | 0.712 | 0.773 | 0.774 | |

| SCA | 0.601 | 0.642 | 0.585 | 0.546 | 0.592 | 0.766 | 0.734 |

| Item | Number of People | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 218 | 55.5 |

| Female | 175 | 44.5 |

| Age | ||

| 20–29 | 69 | 17.6 |

| 30–39 | 169 | 43.0 |

| 40–49 | 101 | 25.7 |

| 50–59 | 43 | 11.0 |

| 60 and above | 11 | 2.8 |

| Place of Residence | ||

| Local | 348 | 88.5 |

| Non-local | 45 | 11.5 |

| Education Level | ||

| Junior high school or below | 47 | 12.0 |

| High school or secondary school | 149 | 37.9 |

| Bachelor’s degree or associate degree | 168 | 42.7 |

| Master’s degree or above | 29 | 7.4 |

| How long have you worked in the homestay industry? | ||

| Less than 1 year | 33 | 8.4 |

| 1–5 years | 217 | 55.2 |

| 5–10 years | 105 | 26.7 |

| 10–20 years | 28 | 7.1 |

| More than 20 years | 10 | 2.5 |

| Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | p | Hypothesis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE | → | CP | 0.232 | 0.083 | 3.018 | 0.003 | Supported |

| MT | → | CP | 0.004 | 0.074 | 0.053 | 0.957 | Not Supported |

| CO | → | CP | 0.223 | 0.077 | 3.139 | 0.002 | Supported |

| PB | → | CP | 0.355 | 0.115 | 2.936 | 0.003 | Supported |

| SF | → | CP | 0.182 | 0.117 | 1.596 | 0.11 | Not Supported |

| CP | → | SCA | 0.766 | 0.069 | 10.763 | *** | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nie, Z.; Cronin, S. Co-Opetition as a Pathway to Sustainability: How Bed and Breakfast Clusters Achieve Competitive Advantage in High-Density Tourism Destinations. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9562. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219562

Nie Z, Cronin S. Co-Opetition as a Pathway to Sustainability: How Bed and Breakfast Clusters Achieve Competitive Advantage in High-Density Tourism Destinations. Sustainability. 2025; 17(21):9562. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219562

Chicago/Turabian StyleNie, Zirui, and Siobhan Cronin. 2025. "Co-Opetition as a Pathway to Sustainability: How Bed and Breakfast Clusters Achieve Competitive Advantage in High-Density Tourism Destinations" Sustainability 17, no. 21: 9562. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219562

APA StyleNie, Z., & Cronin, S. (2025). Co-Opetition as a Pathway to Sustainability: How Bed and Breakfast Clusters Achieve Competitive Advantage in High-Density Tourism Destinations. Sustainability, 17(21), 9562. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219562