Abstract

Sport has long served as a powerful vehicle for promoting social inclusion, particularly among marginalized youth. Football, due to its global appeal and participatory nature, is uniquely positioned to bridge social divides while fostering technical and tactical development. This study explores the dual function of small-sided games (SSGs) in advancing both performance outcomes and inclusive dynamics within youth football contexts. Utilizing a longitudinal case study of a Romanian U14 team during the 2022–2023 season, we implemented a tailored SSG training program aimed at enhancing offensive play and team cohesion. Performance was assessed using key technical and tactical indicators, with data analyzed via SmartPLS structural equation modeling. Results demonstrated statistically significant improvements in several offensive and defensive metrics, including crosses, collective goal-scoring, and ball recovery actions. Importantly, the format of SSGs facilitated equitable participation, reinforcing inclusionary practices. The findings support the integration of SSGs not only as effective pedagogical tools for football training but also as mechanisms for fostering social development through sport. This study underscores the strategic potential of SSGs in aligning youth athletic training with broader educational and social inclusion objectives.

1. Introduction

In the context of modern education and social development, sport represents a vital mechanism for fostering social inclusion, especially among children and adolescents exposed to marginalization, isolation, or disadvantage. Among various sports, football is recognized as a global social phenomenon with significant potential for fostering community engagement and youth development [1,2]. In line with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, particularly SDG 4 (Quality Education) and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities), football—and more specifically small-sided games (SSGs)—can serve as effective tools for both technical-tactical training and social inclusion [3]. Despite this potential, limited research has systematically examined the dual role of SSGs in advancing both performance and inclusion, identity formation, and inter-personal bonds. As such, it serves not only as a vehicle for athletic development but also as a space for cultivating inclusive, equitable environments.

In this paper, we explore the role of small-sided football games (SSGs) as both a pedagogical tool for enhancing technical and tactical player development and a social mechanism capable of promoting inclusion. By focusing on youth players aged 13–14 years, we examine how SSGs—through their structural and relational dynamics—can create conditions that empower young people, foster participation, and strengthen team cohesion.

Research questions:

RQ1: To what extent does a season-long SSG program improve the technical and tactical performance of U14 players in competitive matches?

RQ2: How does participation in SSGs influence players’ perceived social inclusion (belonging, respect, fairness, and enjoyment) within the team environment?

RQ3: What is the fidelity of the implemented SSG program in terms of task constraints, role rotation, and intensity monitoring?

Social Inclusion Through Sport

Social inclusion is a multidimensional construct that encompasses equitable access to resources, active participation in community life, and recognition of individual and group identities. Inclusion involves both removing structural barriers and building social connections that enable individuals to feel part of a collective whole. The World Bank (2013) further emphasizes inclusion as improving the ability, opportunity, and dignity of people to take part in society [4].

In the context of sport, and football in particular, social inclusion refers not merely to physical presence on a team, but to meaningful participation, reciprocal recognition, and development of social capital (FIFA). Football can serve as an inclusive space where shared goals, communication, and structured interaction allow for mutual trust and solidarity to emerge. These processes are especially potent in youth contexts, where identity and interpersonal skills are actively being shaped. In the context of sport (and football in particular), social inclusion transcends mere physical participation; it encompasses meaningful participation, reciprocal recognition, and social capital development—implying that individuals not only take part, but are truly included in roles and environments that foster connection and growth [5].

From a socio-cognitive lens, Social Identity Theory suggests that participation in team sports can enhance group affiliation and reduce intergroup bias. Communities of Practice theory positions football teams as informal learning environments where norms, skills, and values are transmitted through joint engagement.

Within this framework, SSGs play a specific role: by reducing the number of players and the playing area, they increase individual engagement and interaction. This design minimizes hierarchical barriers, enhances communication, and enables all players—regardless of skill or background—to contribute visibly and frequently. These structural features of SSGs support both technical development and inclusive team dynamics.

The education of the young generation encompasses various aspects of human development, including individual, artistic, moral, civic, psycho-behavioral, and biomotor aspects. Inclusive aspects play a crucial role in this process. Children should be trained to use their free time effectively, fostering healthy life habits and promoting socialization, integration, and self-affirmation. Football, a popular sport, is associated with human virtues such as intelligence, honesty, loyalty, pleasure, strength, and mastery. Top performers serve as role models for children from various social areas. Football offers social security and personal affirmation, making it an effective tool for social inclusion [6,7].

FIFA and UNICEF collaborate to improve the quality of life for children and teens by using football as a technique for social inclusion. The Homeless World Cup (HWC) is a successful example of this, with the tournament transforming 1.2 million lives since 2003. SSGs provide superior technical/tactical drills, allowing players to make quick and efficient decisions in various situations. These games are designed to train players to be physically, technically, tactically, psychologically, and theoretically capable of continuing their activity in senior teams [8].

Using games that partially simulate football is a valuable strategy for improving player performance. SSGs involve fewer performers, a compact playing field, and adjusted intervention rules, but they can recreate partial episodes in some 11v11 formats [9,10,11,12].

Football has evolved from normal pitches to smaller pitches, necessitating constant updates on rules and training methods. This requires coaches to adapt and implement new guiding ideas, such as SSGs, based on players’ age and practice experience. SSGs are crucial for skill growth in team activities, especially for younger players. This research aims to highlight the impact of SSGs on improving the offensive phase in football, particularly for 13–14-year-old teams. By de-signing SSGs based on the unique characteristics of this age range, the study aims to improve the team’s offensive level and attack preparation.

Sport plays a crucial role in combating social exclusion, discrimination, poverty, and unfairness. Football, in particular, contributes to the development of fundamental physical and mental qualities such as attention, willpower, perseverance, self-control, endurance, strength, and speed. Inclusive school sports aim to adapt to individual and collective characteristics, breaking down social barriers and promoting diversity. Football is accessible and contributes to the integration of personal efforts and actions in a team’s collective effort, enhancing health and motivation. Street football should be adapted to achieve social goals aimed at individual and collective transformation [6,13,14,15,16].

Stair football should be emphasized for its potential to blend physical, technical, and tactical training in environments similar to actual play. Research findings support the application of Street Soccer Groups (SSGs) as a systematic resource for teaching children the game of football. A recent study found that the average amount of goals per game is highly correlated with the physical parameters of eight different football variants, and changes made to the fundamental elements of football can impact its scoring rate. For example, a 20-m shorter football field could increase the average goal scored per match by 3.6 [17,18].

Research on agility requirements in professional Australian football (AF) compared four SSGs with 14 male premier Australian Football League (AFL) players. The study found that while there was a significant 2D player load, there was little gain in overall agility movements due to reduced surface per player. However, there was an increase in diversity but a moderate overall number of dexterity movements due to fewer players. The adoption of a 2-handed-tag rule caused a somewhat insignificant decline in agility events compared to conventional AFL tackling regulations. Coaches should carefully assess how SSG is designed to maximize each player’s potential for developing agility. The study also found that pitch size changes and goalie participation had different outcomes in terms of overall distance run, explosive distance, accelerations or decelerations, and maximal sprint. Mid-fielders had the highest network significance scores compared to defenders and forwards. The study suggests that coaches can estimate the SSG load and modify the field’s dimensions to accommodate players [19,20,21,22,23].

SSGs are a popular method for football training, as they provide a low training load and allow for a smaller playing area and number of athletes. The size of the pitch is crucial for female football players, as it affects both internal and external strain. SSGs are preferred over wide-sided games, as they allow children under 12 to develop a variety of skills and creativity [24,25].

However, forcing children to play in larger teams and games can reduce engagement, success, enjoyment, and learning opportunities. Larger-sided games often focus on positions and complex adult tactics, rather than developing skills, communication, and enthusiasm. Training on larger-sided playing areas may have a high failure rate for young football players [26].

SSGs are modified versions of known games used during training to prepare players for specific technical, tactical, and physical topics. Regular use of SSGs may result in changes in the technical ability and strategic behaviors of child and junior football players. Further research should analyze the tactical and technical aspects of young players’ responses to different SSG formats, considering their age and training experience [27,28].

A study examined the impact of SSGs on juvenile football players of varying pitch dimensions during 7-a-side SSG forms. Two teams of seven players each were formed from 14 male soccer athletes in each age category. The study recommended coaches use SSGs to encourage specific-adaptive behaviors and improve individual performance. The development of football for children and juniors has increased dynamically at both elite and grassroots levels, with new approaches focusing on personalized games, strategic awareness, technical/tactical learning, and alternative educational progression [21,29].

Playing on a pitch is crucial for the development of young footballers and improving their performance in elite teams [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38]. Low-field games (SSG) are introduced to optimize training time, introduce “street football” in training, increase player motivation, improve decision-making, and enhance tactical aspects. CS Concordia Chiajna’s 2022/2023 competitive season evaluation revealed poor individual technique, inadequate tactics, low physical training, and psychological factors impacting the players. To address these issues, SSGs were introduced into the training process, using various sources such as literature, online platforms, and the internet.

At the same time, the Concordia Chiajna club has developed a program for young people from disadvantaged backgrounds, trying to achieve social inclusion. Noting an accelerated increase in juvenile delinquency, the community of Chejnă together with the Romanian-American University laid the foundations for a project through which young people from Chiajna participate in football training, forming a group of such young people, under the guidance of the coach from the club. This group used Low Court Games (SSG) in the training program. adapted to the value level of this group. After about a year of work (3 training sessions per week) it was possible to introduce 2 such young people in the club’s performance group. Moreover, the CS Concordia Chiajna club has been humanely involved in supporting these young people, offering them accommodation and meals and schooling them in the local school.

As for the team’s performance level, referring to the points obtained in the Championship-Elite League, we can say that considerable progress has been made, in the sense that the first year the team accumulated only 10 points, in the second 20 points and this year they already have 10 points after only 7 rounds. From here we can see that the team has traveled a rather difficult road, constantly improving the value level of the team, ending up fighting for a place in the playoffs (the first 4 teams).

2. Study Purpose

Guided by the theoretical foundations above, this study investigates the dual function of SSGs in football: (1) their impact on technical and tactical performance indicators in 13–14-year-old players, and (2) their potential to foster social inclusion within a youth training environment. While the primary analysis is quantitative and performance-based, the conceptual emphasis is on how the design and implementation of SSGs align with inclusive values and learning principles that are increasingly critical in contemporary sport pedagogy.

3. Materials and Methods

The current analysis is based on a Web of Science (WoS) scan of the scientific literature on football, more specifically, on SSGs across all WoS sectors and categories, with releases from 2020 to 2023 of both research and review publications. The search yielded 1274 papers, of which 41 were selected based on relevant criteria, namely the results and performance obtained. Studies that showed equivalent results but did not have the full text available and were mainly theoretical or irrelevant to the topic were excluded. The author data in Figure 1 are classified by key topic and year, with a connection between them.

Figure 1.

Interrelation between articles written on the SSG topic (Own source, generated with VOSviewer software version 1.6.20).

The effects of SSG treatments on the tactical actions and technical performance of young and adolescent team sports players were examined by a group of writers [26]. 803 titles were initially found in the database search. Of these, six publications were eligible for in-depth examination and meta-analysis. No tactical behavior outcomes were reported in any of the studies reviewed. Compared to controls, the results demonstrated that SSGs had a minor impact on technical performance. After 17 SSG training sessions, a subgroup examination of the training factor highlighted modest and minor improvements in technical execution. This comprehensive study and meta-analysis found that using SSG programs for training to enhance technical performance in young and adolescent performers had a substantial favorable effect. Regardless of the number of training sessions applied, the benefits were similar. However, further research is needed to include tactical actions as one of the effects of limiting the impact of SSG training [39].

The objective of the present study is to find out if these SSGs (drills) can have a positive kick on football players in terms of their ability to complete technical/tactical actions at the opponent’s goal by scoring or staying in possession, or by increasing their team’s percentage of staying in attack and decreasing their team’s percentage of passing in defense. Thus, we aim to analyze the impact of SSG programs on technical/tactical performance among adolescents and young people participating in team sports (with a spotlight on the game of football) in order to improve the performance of 13–14-year-old athletes at a competitive level.

For the Concordia Chiajna children’s team, the coach used ameliorative methods and training based on SSGs, as shown above. The results were quantified through several technical/tactical indicators during the official games played in both the first half and the return stage of the 2022–2023 championship.

This study used an uncontrolled before–after (pre–post) single-arm design in one under-14 (U14) boys’ team competing in the Elite League (season 2023/2024 U14; season 2023/2024 U15; season 2024/2025 U16). The observational unit was the match, with technical–tactical events coded at match level. The intervention was a season-embedded SSG program integrated into regular training microcycles. Because no concurrent control group was available, inferences are limited to associations and observed within-team changes across phases; causal language is avoided.

This study hypotheses are:

H1:

Players will demonstrate significant improvements in key offensive and defensive indicators (e.g., crosses, recoveries, collective goals) between the first and second halves of the season.

H2:

Players’ scores on the Youth Football Perceived Inclusion Mini-Scale (YFPIS) will significantly increase over the course of the intervention.

Eligibility, Observation Window, and Sample Size

Inclusion criteria (matches): official league fixtures within the 2022–2023 season; full-length video available; complete team sheet and substitutions; standard playing format 11v11; regulation pitch.

Exclusion criteria (matches): friendlies/cup games; abandoned or forfeited matches; incomplete footage; <70 min effective recording; extraordinary events altering match structure (e.g., prolonged medical stoppage, multiple red cards >1 per team before minute 30, weather suspension).

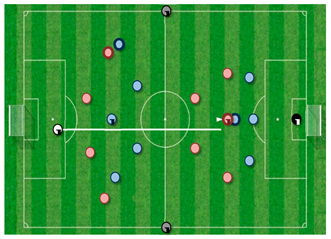

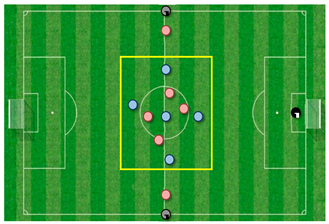

The intervention was operationalized through a structured SSG -based training microcycle applied to the Concordia Chiajna U14 team. Each 90-min session combined physical, technical, and tactical objectives, with an average intensity of ~70% and group sizes of 20 players on synthetic turf. Training resources included 10 balls, 10 bibs, and 10 cones.

The session design followed three main phases:

- Introductory Phase (≈30 min)—dynamic stretching and activation games such as handball-style possession (aiming at spatial awareness and mobility under constraints) and 4v4+4 rondo formats (promoting rapid ball circulation, pressure resistance, and support play).

- Fundamental Phase (≈65 min)—progressive SSG scenarios targeting offensive and transitional dynamics:

The fundamental phase of training (≈65 min) was structured around a progression of SSGs as presented in Table 1. These scenarios were designed to enhance offensive efficiency, transitional play, and collective tactical awareness, while simultaneously adhering to fidelity principles including task constraints, duration and work–rest balance, intensity monitoring, coaching cues, and equitable role rotation.

Table 1.

SSGs training fidelity analysis.

Training formats ranged from reduced-number games, such as 3v3+3 defense in numerical inferiority and 4v4+4 control-oriented marking, which emphasized resilience under pressure, ball circulation, and marking principles, to medium-size scenarios such as 6v6+6 pressing and pressure and 6v6+6 control and passing, focusing on compact pressing, short-passing retention, and support play. Larger formats, including 7v7 transition games, 8v8+4 defensive transition, and 9v9+4 transition games, were used to replicate broader tactical demands, such as counterattacking, defensive reorganization, and zone switching. Finally, possession-based scenarios with finishing components, notably the 9v9 possession and pace of play with finishing and the rondo with finishing, encouraged rapid recognition of attacking opportunities and coordinated offensive execution.

This structured progression allowed for increasing tactical complexity and physical load, while maintaining alignment with the principles of inclusion through systematic role rotation and consistent application of coaching cues. In this way, the fundamental phase not only supported the development of offensive and transitional behaviors but also ensured equitable engagement for all players, reinforcing the dual objectives of technical-tactical improvement and social inclusion.

- 3.

- Closing Phase (≈5 min)—low-intensity jogging, stretching, breathing exercises, and coach–player feedback to consolidate physical recovery and reflective learning.

The overarching objectives were the improvement of ball retention under pressure, efficient zone changes in attack, and rapid transition behaviors. Across sessions, coaches emphasized decision-making, communication, and collaborative play, ensuring equitable engagement and alignment with the principles of social inclusion. An example of training plan is presented in Appendix C.

4. Results

4.1. Teting Social Inclusion Rate

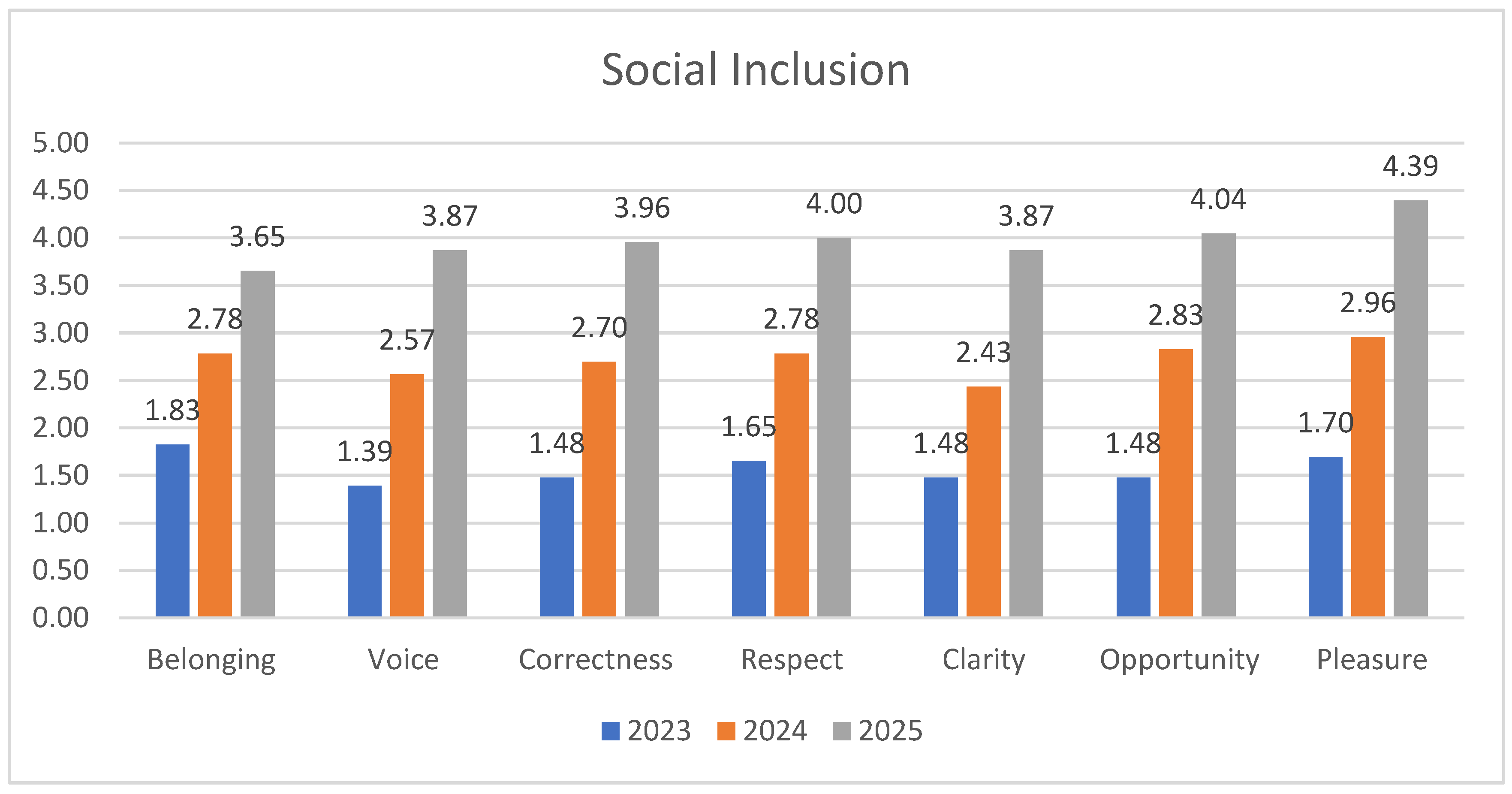

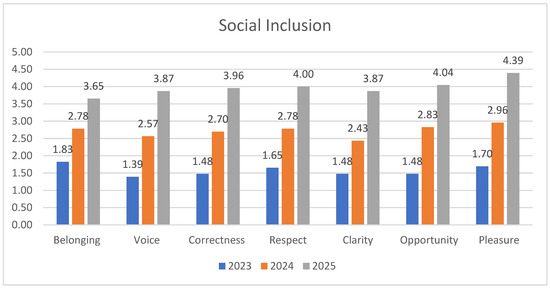

Analysis of the Youth Football Perceived Inclusion Mini-Scale (YFPIS) scores across three years (2023–2025) demonstrates a consistent upward trend in players’ perceptions of social inclusion. In 2023, mean scores for all dimensions were relatively low, ranging from 1.39 (Voice) to 1.83 (Belonging), with narrow 95% confidence intervals (CIs; e.g., Belonging CI = 0.31). In 2024, substantial increases were observed, with means rising to between 2.43 (Clarity) and 2.96 (Pleasure), again with reasonably tight CIs (e.g., Pleasure CI = 0.31). By 2025, all indicators reached their highest levels, with means spanning from 3.65 (Belonging) to 4.39 (Pleasure). The CIs for this final year confirmed the precision of these estimates (e.g., Belonging CI = 0.31; Pleasure CI = 0.22). Together, these results indicate a consistent upward trajectory across social inclusion and performance-related dimensions, supporting the interpretation that increases in participation and belonging occurred in the same temporal window as gains in technical–tactical clarity, opportunity, and pleasure. (Figure 2 and Appendix A).

Figure 2.

Social Inclusion evolution.

4.2. SSGs Training Fidelity Analysis

The fidelity checklist revealed that the small-sided game (SSG) training sessions were generally implemented with high consistency, with total scores ranging from 8 to 12 out of 12 possible points. Sessions such as 6v6+6 control and passing and 9v9 possession and pace with finishing achieved perfect fidelity scores, indicating that all elements—including task constraints, duration, work-to-rest balance, intensity, coaching cues, and role rotation—were fully applied as intended. In contrast, sessions like 6v6+6 pressing and pressure and Rondo with finishing scored lowest (8/12), reflecting deviations primarily in task constraints, intensity, and work-to-rest implementation. Across sessions, coaching cues and role rotation were consistently strong, suggesting that the learning environment was both supportive and inclusive. However, intensity monitoring and strict adherence to task constraints were more variable, which may have influenced the consistency of the training stimulus. Overall, the data suggest that the intervention was delivered with high fidelity, ensuring that most sessions aligned with the intended design and thereby supporting reliable dose–response analysis (Appendix B).

4.3. Testing Technical/Tactical Offensive Actions

To find out if there is a statistically meaningful variation among the test values achieved in the first half and the return stage of the championship for technical/tactical offensive actions, we apply the t-test for Paired Samples (Paired-Two-Sample for Means).

Analyses of offensive indicators revealed several significant improvements from the first half of the season to the return phase (Table 2). Players produced substantially more crosses in the return phase (M = 18.67) compared to the first half (M = 4.33), t(5) = 4.02, p = 0.01, d = 1.64, 95% CI [5.17, 23.50]. A similar pattern was observed for crosses with ball possession, t(5) = 3.63, p = 0.015, d = 1.48, 95% CI [2.91, 17.09]. Diagonal launches also increased significantly (M = 14.17 vs. 4.67), t(5) = 2.74, p = 0.041, d = 1.12, 95% CI [0.60, 18.40]. The most pronounced effect emerged for corner kicks, which rose sharply (M = 15.00 vs. 0.33), t(5) = 10.80, p < 0.001, d = 4.41, 95% CI [11.18, 18.16]. Penalty kicks also showed a significant increase (M = 3.83 vs. 0.50), t(5) = 2.71, p = 0.042, d = 1.11, 95% CI [0.17, 6.49]. In contrast, vertical launches demonstrated only a nonsignificant trend toward improvement, t(5) = 1.87, p = 0.12, d = 0.76. Neither throw-ins from the own half (t(5) = −1.82, p = 0.128, d = −0.74) nor throw-ins from the opponent’s half (t(5) = −0.73, p = 0.499, d = −0.30) changed significantly across phases. Shapiro−Wilk tests confirmed that all difference scores were approximately normally distributed (all ps > 0.08).

Table 2.

t-Test for Paired Samples: Offensive actions.

4.4. Testing Technical/Tactical Defensive Actions

To find out if there is a statistically meaningful variation among the test values achieved in the first half and the return stage of the championship for technical/tactical defensive actions, we apply the t-test for Paired Samples (Paired Two-Sample for Means).

Analyses of defensive indicators revealed mixed patterns. Ball recoveries in the goal area were significantly higher in the first half (M = 33.50) than in the return phase (M = 17.50), t(5) = −5.20, p = 0.003, d = −2.12, 95% CI [−23.91, −8.09]. Similarly, recoveries in the opponent’s half declined from the first half (M = 7.67) to the return (M = 5.17), t(5) = −5.84, p = 0.002, d = −2.38, 95% CI [−3.60, −1.40]. Other defensive indicators showed nonsignificant changes, including recoveries in the penalty area (t(5) = −1.28, p = 0.258, d = −0.52), recoveries in the own half (t(5) = −1.73, p = 0.144, d = −0.71), rejections with the foot (t(5) = −2.34, p = 0.066, d = −0.96), rejections with the head (t(5) = −1.60, p = 0.171, d = −0.65), and penalties conceded (t(5) = −0.76, p = 0.484, d = −0.31). Assumption checks indicated acceptable normality for difference scores (Shapiro−Wilk ps > 0.42), except for goal area recoveries, which showed some departure (p = 0.007) (Table 3).

Table 3.

t-Test for Paired Samples: Defensive actions.

4.5. Testing the Number of Scored Goals

To find out if there is a statistically meaningful variation among the test values achieved in the first half and the return stage of the championship for the number of scored goals, we apply the t-test for Paired Samples (Paired Two-Sample for Means).

Changes in scoring outcomes favored the return phase, though differences did not reach statistical significance at n = 6. Goals from active play increased (M = 4.00 vs. 0.50), t(5) = 1.73, p = 0.145, d = 0.70, 95% CI [−1.72, 8.72]. Similarly, goals from set pieces rose (M = 9.83 vs. 5.17), t(5) = 1.63, p = 0.164, d = 0.67, 95% CI [−2.68, 12.02]. Total goals also trended upward (M = 13.83 vs. 5.67), t(5) = 1.78, p = 0.136, d = 0.73, 95% CI [−3.64, 19.97]. While not statistically significant, effect sizes were in the medium-to-large range, indicating potentially meaningful improvements. Normality tests suggested no major violations (all Shapiro–Wilk ps > 0.25) (Table 4).

Table 4.

t-Test for Paired Samples: Testing the number of scored goals.

In football, SSG training did not positively influence these offensive components, but they can be influenced by other individuals. The DTMIN average (691.25) is lower than the DRMIN average (704.37), indicating concerns about keeping the ball in play and strengthening in-game relationships.

Thus:

- -

- the number of crosses increased from 4.63 to 6.88 (+2.25);

- -

- the number of crosses with ball possession increased from 2.81 to 3.69 (+0.875);

- -

- the number of corner kicks increased from 2.5 to 3.69 (+1.1875);

- -

- the number of penalty kicks increased from 1.19 to 1.31 (+0.125);

- -

- the number of throw-ins from the own half decreased from 3.94 to 2.69 (−1.25);

- -

- the number of throw-ins from the opponent’s half increased from 2.5 to 4.38 (+1.875).

Instead, the results decreased for two indicators:

- -

- vertical releases—from 5.75 to 4.31 (−1.4375);

- -

- diagonal releases—from 4.19 to 3.88 (−0.3125).

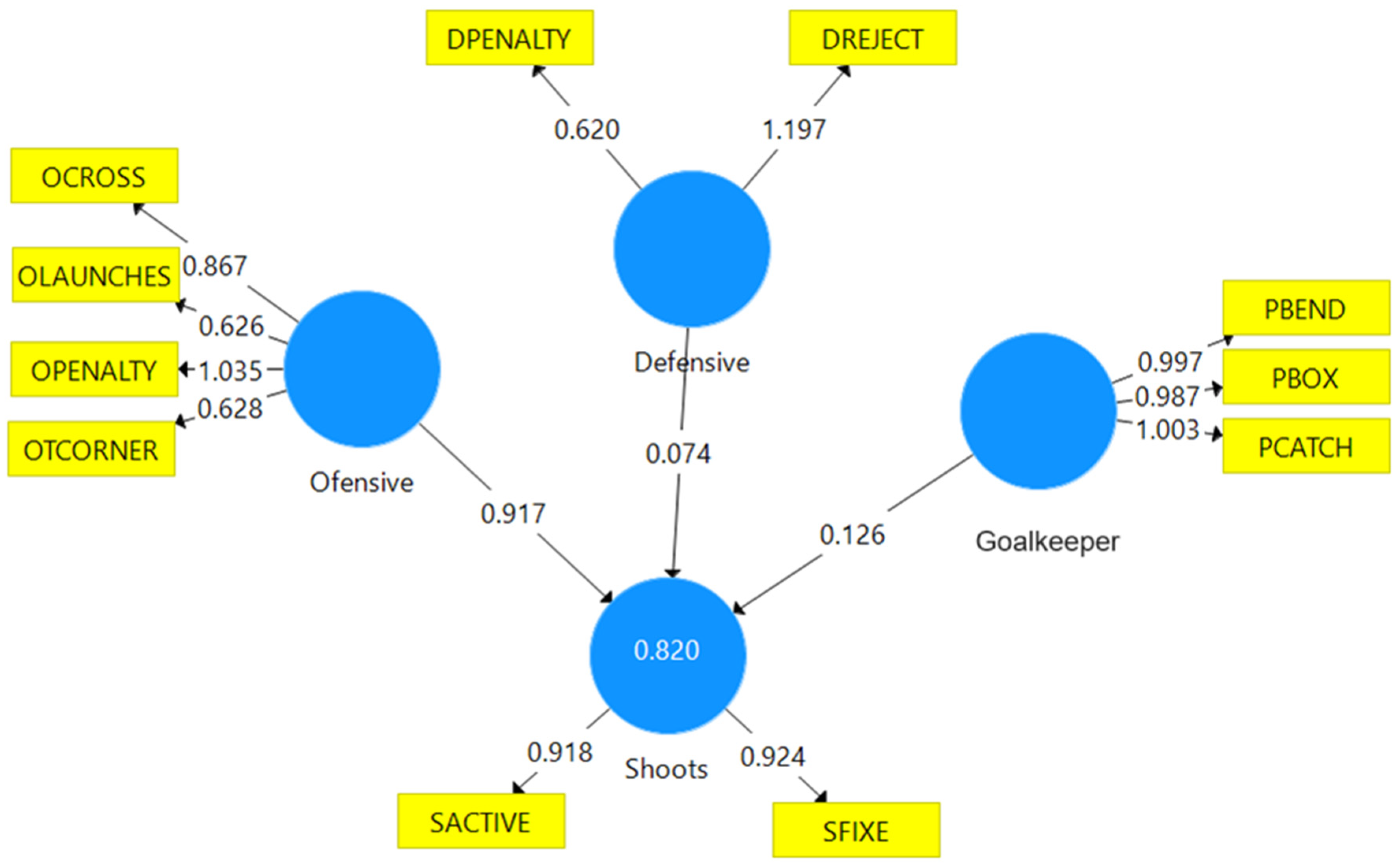

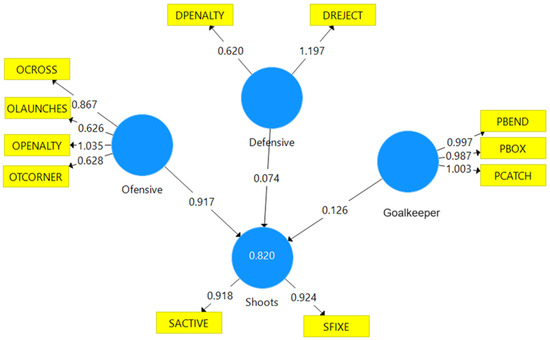

Based on the previously analyzed variables, we have designed a regression model highlighting that each of the offensive and defensive components or the goalkeeper’s play has a positive influence on game performance (number of goals from fixed or active phases). The Path Coefficients: OffensiveShots (0.917), Goalkeeper Shots (0.126), and DefensiveShots (0.074) reveal once again the crucial importance of the offensive phase, demonstrating the positive effect of SSGs on improving game strategy and making inspired decisions in real-time (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Structural Equation Model created using SmartPLS, version 3.2.9. (This is an output of the SmartPLs software, obtained after stastistical analysis. It is a standard type of output).

The model designed by us is very strong and reflects reality very well because all regression conditions are met, with CA (Cronbach’s Alpha), Rho_A, and CR (Composite Reliability) greater than 0.7, and AVE (Average Variance Extracted) > 0.5 (Table 4). There is no multicollinearity between variables since VIF (Variance Inflation Factor) is less than 3 for each analyzed sub-item. R2 is 0.820, indicating a very strong positive correlation between variables. Adjusted R2 is 0.776, which means that the variance of the independent variables OFFENSIVE, DEFENSIVE, and GOALKEEPER ex-plains 77.6% of the variance of the dependent variable SHOTS (Table 5).

Table 5.

Regression model validation indicators.

The Fornell–Larcker criterion was used to assess discriminant validity across the latent constructs. The square roots of the average variance extracted (AVEs) were consistently greater than the inter-construct correlations, supporting discriminant validity. Specifically, the AVE square roots were 0.953 for Defensive, 0.996 for Goalkeeper, 0.808 for Offensive, and 0.921 for Shoots. These values exceeded the correlations among constructs (e.g., Defensive–Goalkeeper r = 0.267; Offensive–Shoots r = 0.891), indicating that each construct shared more variance with its indicators than with other constructs. Collectively, these results confirm that the measurement model achieved acceptable discriminant validity.

Multicollinearity was assessed using variance inflation factors (VIFs). The most indicators fell well below the conventional cut-off of 5.0 [40], indicating that collinearity was not a major concern. Specifically, VIF values ranged from 2.13 for Openalty to 3.66 for Ocross, with additional moderate values for Olaunches (3.18), Ocorner (3.52), Sactive (3.57), and Sfixe (3.57). Very low and negative values were observed for Pbend, Pbox, and Pcatch, which are likely computational anomalies or artifacts of estimation, and thus require cautious interpretation. Overall, the results suggest that the measurement model did not exhibit problematic multicollinearity.

5. Discussion

The findings of this case study suggest that SSGs can positively influence both the technical–tactical performance and inclusive dynamics of youth football. However, given the methodological constraints of a single-team design and the small sample size, these results should be interpreted as exploratory rather than definitive. This section situates the outcomes in the wider pedagogical and sustainability context, acknowledges methodological challenges, and highlights directions for future research.

5.1. Technical–Tactical Development Through SSGs

The offensive and defensive improvements observed—such as increases in crosses, collective goal-scoring, and ball recoveries—support prior work showing that spatial and numerical constraints in SSGs enhance decision-making and game awareness [9,27]. These changes indicate that SSGs may foster not only technical efficiency but also tactical intelligence through frequent repetitions in game-like conditions. Nonetheless, other indicators, such as penalty kick outcomes or aerial defensive actions, did not change significantly, suggesting that complementary training modalities are needed to target less frequent or context-specific skills.

5.2. Social Inclusion and Team Participation

Beyond technical outcomes, the equal participation inherent in SSG structures appeared to reduce hierarchical barriers and promote inclusion. All players had repeated opportunities to contribute, which aligns with social identity theory and supports group cohesion. The increase in goals from collective actions and shifts toward more advanced field positions reflect a more distributed responsibility across the team, a hallmark of inclusive sporting environments. From a psychosocial perspective, this suggests that SSGs can strengthen belonging and shared purpose—critical elements for adolescent development.

5.3. Alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

While sport’s contribution to sustainable development is often acknowledged, this study demonstrates concrete pathways linking SSGs to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

The intervention outcomes can be meaningfully situated within the framework of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In relation to SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being), players reported marked improvements in psychosocial experiences, as reflected in increases on the YFPIS belonging (Mpre = 1.83; Mpost = 3.65) and pleasure subscales (Mpre = 1.70; Mpost = 4.39). These gains suggest that SGs enhanced both participation and enjoyment, key indicators of youth well-being. Consistent with SDG 4 (Quality Education), technical–tactical outcomes demonstrated significant learning effects, with improvements in crosses (t(5) = 4.02, p = 0.01, d = 1.64) and diagonal launches (t(5) = 2.74, p = 0.041, d = 1.12), highlighting the pedagogical potential of structured play to develop decision-making and technical execution. Regarding SDG 5 (Gender Equality), while the study was conducted within a single U14 male team, the systematic use of inclusive pedagogical tools (e.g., role rotation and balanced participation monitored via fidelity checklists) aligns with principles of equitable practice in youth sport and provides a replicable model to support mixed-gender or underrepresented groups in future interventions. The findings also speak to SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities), as increases in fairness/correctness (Mpre = 1.48; Mpost = 3.96) and opportunity (Mpre = 1.48; Mpost = 4.04) subscales indicate that the intervention fostered more equitable participation and reduced perceived disparities within the team environment. Finally, outcomes linked to SDG 16 (Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions) were evident in significant increases on the YFPIS respect (Mpre = 1.65; Mpost = 4.00) and voice subscales (Mpre = 1.39; Mpost = 3.87), reflecting greater fairness, dialogue, and shared decision-making within the group. Taken together, these findings demonstrate that structured SSGs not only foster performance development but also contribute measurable progress toward global targets of health, education, equality, reduced inequalities, and inclusive institutions.

5.4. Methodological Considerations

Several methodological limitations temper the strength of causal claims:

Sample Size and Scope: Only one U14 Romanian team (n = 23) was included, limiting generalizability across regions, age groups, or competitive levels. The design should be regarded as a pilot case study.

Confounding Factors: Improvements could also reflect natural growth, maturation, or coaching strategies unrelated to SSG exposure. Without a control group, isolating the specific effect of SSGs remains challenging.

SmartPLS Analysis: While the model showed strong internal consistency and explanatory power, key goodness-of-fit indices (e.g., SRMR, NFI) were not reported, and the small sample size does not meet recommended thresholds for PLS-SEM (n ≥ 100). Consequently, the statistical model should be considered exploratory.

5.5. Future Directions

To strengthen the evidence base, future research should:

Incorporate larger, multi-team samples across regions and age groups to test generalizability.

Use controlled or randomized designs to better separate intervention effects from maturation or contextual factors.

Complement quantitative indicators with qualitative assessments (e.g., interviews, sociometric mapping) to more directly capture perceptions of inclusion.

Explore hybrid training approaches that combine SSGs with targeted drills to address underrepresented tactical or technical actions.

5.6. Summary

In sum, SSGs appear to offer dual benefits: they improve technical–tactical execution while fostering inclusive team environments. Their design naturally supports frequent involvement, shared responsibility, and collaboration—outcomes that extend beyond sport into the broader aims of sustainable education and social inclusion. While the present findings remain provisional, they contribute to a growing body of work positioning SSGs as both a methodological and social innovation in youth football.

6. Conclusions

SSGs proved to be an effective method for enhancing both technical–tactical performance and social inclusion in youth football. For players aged 13–14, SSG-based training improved offensive and defensive execution while also fostering equitable participation, belonging, and respect. These dual outcomes highlight SSGs as a sustainable pedagogical model, aligning competitive development with broader educational and social goals. Future research with larger samples and mixed-methods designs is recommended to confirm and extend these findings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.-D.P. and R.S.E.; methodology, R.S.E. and M.D.D.; software, R.S.E. and M.D.D.; validation, G.-D.P. formal analysis, G.-D.P.; investigation, G.-D.P.; resources, G.-D.P.; data curation, R.S.E. and M.D.D.; writing—original draft preparation, G.-D.P.; writing—review and editing, G.-D.P., R.S.E. and M.D.D.; visualization, G.-D.P.; supervision, G.-D.P.; project administration, G.-D.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the The Research Ethics Commission of the Faculty of Physical Education, Sports and Physiotherapy, Romanian-American University and CS Concordia Chiajna (protocol code: 147/30.09.2022 and approval date: 30 September 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Perceived Inclusion Scale

Title: Youth Football Perceived Inclusion Mini-Scale (YFPIS)

Purpose: To measure players’ perceptions of inclusion, belonging, and fairness within the training and match environment. Designed for adolescents (13–14 years) in football contexts.

Administration: Self-report, paper or digital. Collected three times (pre-season, mid-season, post-season). 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree).

Anonymous to encourage honesty.

Items

Belonging—“I feel accepted as a valued member of this team.”

Voice—“My ideas and suggestions are listened to during training.”

Fairness—“Everyone on this team gets a fair chance to participate.”

Respect—“My teammates and coaches treat me with respect.”

Role Clarity—“I understand my role in the team and have the opportunity to contribute.”

Opportunity—“I get enough chances to be involved in the game (touches, passes, shots).”

Enjoyment—“I enjoy training and matches with this team.”

Table A1.

Social inclusion—descriptive statistics.

Table A1.

Social inclusion—descriptive statistics.

| Year | Stat | Belonging | Voice | Correctness | Respect | Clarity | Opportunity | Pleasure | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | Mean | 1.83 | 1.39 | 1.48 | 1.65 | 1.48 | 1.48 | 1.70 | 2023 |

| 2023 | SD | 0.72 | 0.58 | 0.51 | 0.57 | 0.51 | 0.59 | 0.47 | 2023 |

| 2023 | CI | 0.31 | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.26 | 0.20 | 2023 |

| 2024 | Mean | 2.78 | 2.57 | 2.70 | 2.78 | 2.43 | 2.83 | 2.96 | 2024 |

| 2024 | SD | 0.52 | 0.79 | 0.63 | 0.52 | 0.51 | 0.83 | 0.71 | 2024 |

| 2024 | CI | 0.22 | 0.34 | 0.27 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.36 | 0.31 | 2024 |

| 2025 | Mean | 3.65 | 3.87 | 3.96 | 4.00 | 3.87 | 4.04 | 4.39 | 2025 |

| 2025 | SD | 0.71 | 0.69 | 0.71 | 0.67 | 0.63 | 0.71 | 0.50 | 2025 |

| 2025 | CI | 0.31 | 0.30 | 0.31 | 0.29 | 0.27 | 0.31 | 0.22 | 2025 |

Appendix B. Small-Sided Games (SSG) Fidelity Checklist

Purpose: To assess the extent to which the SSG training sessions were delivered as intended, ensuring intervention consistency and enabling dose–response analyses.

Administration: Completed by the head coach or assistant after each session. Scored on a 0–2 scale per item (0 = not achieved, 1 = partially achieved, 2 = fully achieved).

Total possible score: 0–12. Higher scores = higher fidelity.

Checklist Items

Task Constraints—Were the planned rules, numerical formats (e.g., 4v4+4, 7v7, 8v8+GK), and conditions applied as designed?

(0 = deviated, 1 = minor deviations, 2 = fully applied)

Duration—Were the prescribed work and rest periods implemented correctly (±10% tolerance)?

(0 = >20% deviation, 1 = minor deviation, 2 = on target)

Work:Rest Balance—Did the intensity and recovery cycles reflect the planned ratios (e.g., 3 min play/1 min rest)?

(0 = inconsistent, 1 = somewhat consistent, 2 = consistent)

Intensity Proxy—Was session intensity monitored (e.g., RPE, HR zones, external load if available) and did it align with target (~70% mean effort)?

(0 = no monitoring, 1 = monitored but outside target, 2 = monitored and within target)

Coaching Cues—Were the intended coaching prompts delivered (decision-making, communication, collaboration, inclusion)?

(0 = absent, 1 = partial delivery, 2 = fully delivered)

Role Rotation/Inclusion—Were roles (e.g., goalkeeper, floater, neutral player) rotated to ensure equitable involvement of all players?

(0 = no rotation, 1 = limited rotation, 2 = full and fair rotation)

Appendix C. Training Plan 10

Concordia Chiajna

Group 2009 (U16); Coach: Păun Dan

Character: physical-technical, tactical

No. of players: 20; Duration: 90 min; Field: Synthetic turf

Intensity: 70%; Materials: 10 balls, 10 breastplates, 10 cones

Themes and objectives: Direct attack and 2nd ball and possession

Table A2.

Training plan—example.

Table A2.

Training plan—example.

| Training Part | Means | Work Training | Dose | Observations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Part Introduction 30 min | 1. Handball (15 min) Players run and stretch in the first 5 min. Players then progress to a possession game using only their hands. Ten passes equals one goal. Players are not allowed to move with the ball in their hand. Players must move away from the ball to create passing options. Players are only allowed to hold the ball for three seconds. After that, I can only run 3 steps and the speed increases. At the end 5 min stretching | 4 columns | 15 min |  |

| 2. 4 vs. 4+4 Each team has four players. Black’s players are on the outside, they each have a ball. They try to pass the ball to the players of the Yellow team who pass it back with a single touch. The Red Team must score the Yellow Team. Every 5 min the roles change. | 3 teams | 15 min |  | ||

| 2 | The fundamental part 65 min | 1. 2 teams. The goalkeeper throws the ball into the opponent’s half where an attempt is made to win the ball, followed by completion in time as quickly as possible. | 2 teams | 20 min |  |

| 2. Shipping: 4 vs. 4 in a square with 2/4 jokers. The team that makes 10 passes can complete and the team that recovers the ball goes to finish with the 2/4 jokers. | 4 teams | 20 min |  | ||

| 3. Bilateral play | 2 teams | 20 min | 1/2 plot | ||

| 3 | Part Conclusion 5 min | -Easy running -Walking with breath -Stretching -Feedback | Individual -The whole team |

Indications

- -

- Be careful when exiting crowded areas with ball passing, one-two, dribbling or changing the direction of play.

- -

- The stretching exercises at the end of the workout are relaxation stretching, especially on muscle groups requested.

References

- Javier, D.G.; Martín, J.; Jesús, P. Fútbol y Racismo: Un Problema Científico y Social. Soccer and Racism: A Scientific and Social Problem. RICYDE Rev. Int. Cienc. Deporte 2006, 3, 68–94. Available online: http://www.cafyd.com/REVISTA/art5n3a06.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Blondeau, J. The Influence of Field Size, Goal Size and Number of Players on the Average Number of Goals Scored per Game in Variants of Football and Hockey: The Pi-Theorem Applied to Team Sports. J. Quant. Anal. Sports 2020, 17, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.J.; Young, W.; Farrow, D.; Bahnert, A. Comparison of Agility Demands of Small-Sided Games in Elite Australian Football. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2013, 8, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Inclusion Matters: The Foundation for Shared Prosperity. The Report Defines Social Inclusion as “The Process of Improving the Ability, Opportunity, and Dignity of People, Disadvantaged on the Basis of Their Identity, to Take Part in Society”. 2013. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099819401222443265/pdf/IDU175f35c9f149be1458318ec61979fcfa7dd5e.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Pečnikar Oblak, V.; Campos, M.J.; Lemos, S.; Rocha, M.; Ljubotina, P.; Poteko, K.; Kárpáti, O.; Farkas, J.; Perényi, S.; Kustura, U.; et al. Narrowing the Definition of Social Inclusion in Sport for People with Disabilities through a Scoping Review. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilamitjana, J.J. Soccer, an Opportunity for Social Integration. Boletín Electrónico REDAF 2014, 73, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.M. Soccer and its Educational and Social Possibilities. Cult. Cienc. Y Deporte 2006, 4, 13–19. Available online: https://www.homelessworldcup.org/ (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Sánchez-Sánchez, J.; Yagüe, J.M.; Fernández, R.C.; Petisco, C. Effects of small-sided games training on technique and physical condition of young footballers. RICYDE Rev. Int. Cienc. Deporte 2014, 41, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampinini, E.; Impellizzeri, F.M.; Castagna, C.; Abt, G.; Chamari, K.; Sassi, A.; Marcora, S.M. Factors influencing physiological responses to small-sided soccer games. J. Sports Sci. 2007, 25, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Little, T. Optimizing the Use of Soccer Drills for Physiological Development. Strength Cond. J. 2009, 31, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, A.L.; Ford, P.R.; Twist, C. Small-Sided Games: The Physiological and Technical Effect of Altering Pitch Size and Player Numbers. Insight 2004, 7, 50–53. [Google Scholar]

- Barnabé, L.; Volossovitch, A.; Ferreira, A.P. Effect of Small-Sided Games on the Physical Performance of Young Football Players of Different Ages and Levels of Practice. In Performance Analysis of Sport IX; Peters, D., O’Donoghue, P., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014; pp. 71–76. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, C.H.; Volossovitch, A.; Duarte, R. Influence of Scoring Mode and Age Group on Passing Actions during Small-Sided and Conditioned Soccer Games. Hum. Mov. 2017, 18, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonney, N.; Ball, K.; Berry, J.; Larkin, P. Effects of Manipulating Player Numbers on Technical and Physical Performances Participating in an Australian Football Small-Sided Game. J. Sports Sci. 2020, 38, 2430–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, F.J.; Figueiredo, T.; Ferreira, C.; Espada, M. Physiological and Physical Effects Associated with Task Constraints, Pitch Size, and Floater Player Participation in U-12 1 × 1 Soccer Small-Sided Games. Hum. Mov. 2022, 23, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, P.H.; da Costa, J.C.; Ramos-Silva, L.F.; Praça, G.M.; Vaz Ronque, E.R. Combined Effect of Game Position and Body Size on Network-Based Centrality Measures Performed by Young Soccer Players in Small-Sided Games. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 873518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangnier, S.; Cotte, T.; Brachet, O.; Coquart, J.; Tourny, C. Planning Training Workload in Football Using Small-Sided Games’ Density. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2019, 33, 2801–2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modena, R.; Togni, A.; Fanchini, M.; Pellegrini, B.; Schena, F. Influence of Pitch Size and Goalkeepers on External and Internal Load during Small-Sided Games in Amateur Soccer Players. Sport Sci. Health 2021, 17, 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sannicandro, I. Small-Sided Games and Size Pitch in Elite Female Soccer Players: A Short Narrative Review. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 2021, 16, S361–S369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, F.M.; Wong, D.P.; Martins, F.M.L.; Mendes, R.S. Acute Effects of the Number of Players and Scoring Method on Physiological, Physical, and Technical Performance in Small-Sided Soccer Games. Res. Sports Med. 2014, 22, 380–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Football. Using Small-Sided Games. 2024. Available online: https://ministry-of-football.com/small-sided-games/ (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Casamichana Gómez, D.; Castellano Paulis, J.; González-Morán, A.; García-Cueto, H.; García-López, J. Physiological Demand in Small-Sided Games on Soccer with Different Orientation of Space. RICYDE Rev. Int. Cienc. Deporte 2011, 23, 141–154. Available online: http://www.cafyd.com/REVISTA/02306.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Castellano, J.; Fernández, E.; Echeazarra, I.; Barreira, D.; Garganta, J. Influence of Pitch Length on Inter-and Intra-Team Behaviors in Youth Soccer. An. Psicol. 2017, 33, 486–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, F.M.; Ramirez-Campillo, R.; Sarmento, H.; Praça, G.M.; Afonso, J.; Silva, A.F.; Rosemann, T.J.; Knechtle, B. Effects of Small-Sided Game Interventions on the Technical Execution and Tactical Behaviors of Young and Youth Team Sports Players: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 667041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnabé, L.; Volossovitch, A.; Duarte, R.; Ferreira, A.P.; Davids, K. Age-Related Effects of Practice Experience on Collective Behaviours of Football Players in Small-Sided Games. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2016, 48, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frencken, W.; Lemmink, K.; Delleman, N.; Visscher, C. Oscillations of Centroid Position and Surface Area of Soccer Teams in Small-Sided Games. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2011, 11, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill-Haas, S.V.; Dawson, B.T.; Impellizzeri, F.M.; Coutts, A.J. Physiology of Small-Sided Games Training in Football: A Systematic Review. Sports Med. 2011, 41, 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampaio, J.E.; Lago, C.; Gonçalves, B.; Maças, V.M.; Leite, N. Effects of Pacing, Status and Unbalance in Time Motion Variables, Heart Rate and Tactical Behaviour when Playing 5-A-Side Football Small-Sided Games. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2013, 17, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill-Haas, S.V.; Coutts, A.J.; Rowsell, G.J.; Dawson, B.T. Generic versus Small-Sided Game Training in Soccer. Int. J. Sports Med. 2009, 30, 636–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, D.M.; Drust, B. The Effect of Pitch Dimensions on Heart Rate Responses and Technical Demands of Small-Sided Soccer Games in Elite Players. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2009, 12, 475–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aroso, J.; Rebelo, A.; Gomes-Pereira, J. Physiological Impact of Selected Game-Related Exercises. J. Sports Sci. 2004, 22, 522. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, S.; Drust, B. Physiological and Technical Demands of 4v4 and 8v8 Games in Elite Youth Soccer Players. Kinesiology 2007, 39, 150–156. [Google Scholar]

- Katis, A.; Kellis, E. Effects of Small-Sided Games on Physical Conditioning and Performance in Young Soccer Players. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2009, 8, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Little, T.; Williams, A.G. Suitability of Soccer Training Drills for Endurance Training. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2006, 20, 316–319. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, K.; Owen, A.L. The Impact of Player Numbers on the Physiological Responses to Small-Sided Games. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2007, 6, 99–102. [Google Scholar]

- Hoff, J.; Wisloff, U.; Engen, L.C.; Kemi, O.J.; Helgerud, J. Soccer Specific Aerobic Endurance Training. Br. J. Sports Med. 2002, 36, 218–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallo, J.; Navarro, E. Physical Load Imposed on Soccer Players during Small-Sided Training Games. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2008, 48, 166–171. [Google Scholar]

- Hill-Haas, S.V.; Coutts, A.J.; Dawson, B.T.; Rowsell, G.J. Time-Motion Characteristics and Physiological Responses of Small-Sided Games in Elite Youth Players: The Influence of Player Number and Rule Changes. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2010, 24, 2149–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessitore, A.; Meeusen, R.; Piacentini, M.F.; Demarie, S.; Capranica, L. Physiological and Technical Aspects of “6-A-Side” Soccer Drills. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2006, 46, 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to Use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).