ESG Performance and Tourism Enterprise Value: Impact Effects and Mechanism Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

2.1. ESG Disclosure and Market Value

2.2. Mediating Factors

3. Research Design

3.1. Model Specification

3.1.1. Baseline Model

3.1.2. Difference in Differences Model

3.2. Variable Setting

3.2.1. Core Explanatory Variable

3.2.2. Explained Variable

3.2.3. Control Variables

3.3. Data Sources

4. Empirical Results Analysis

4.1. Baseline Regression

4.2. Robustness Tests

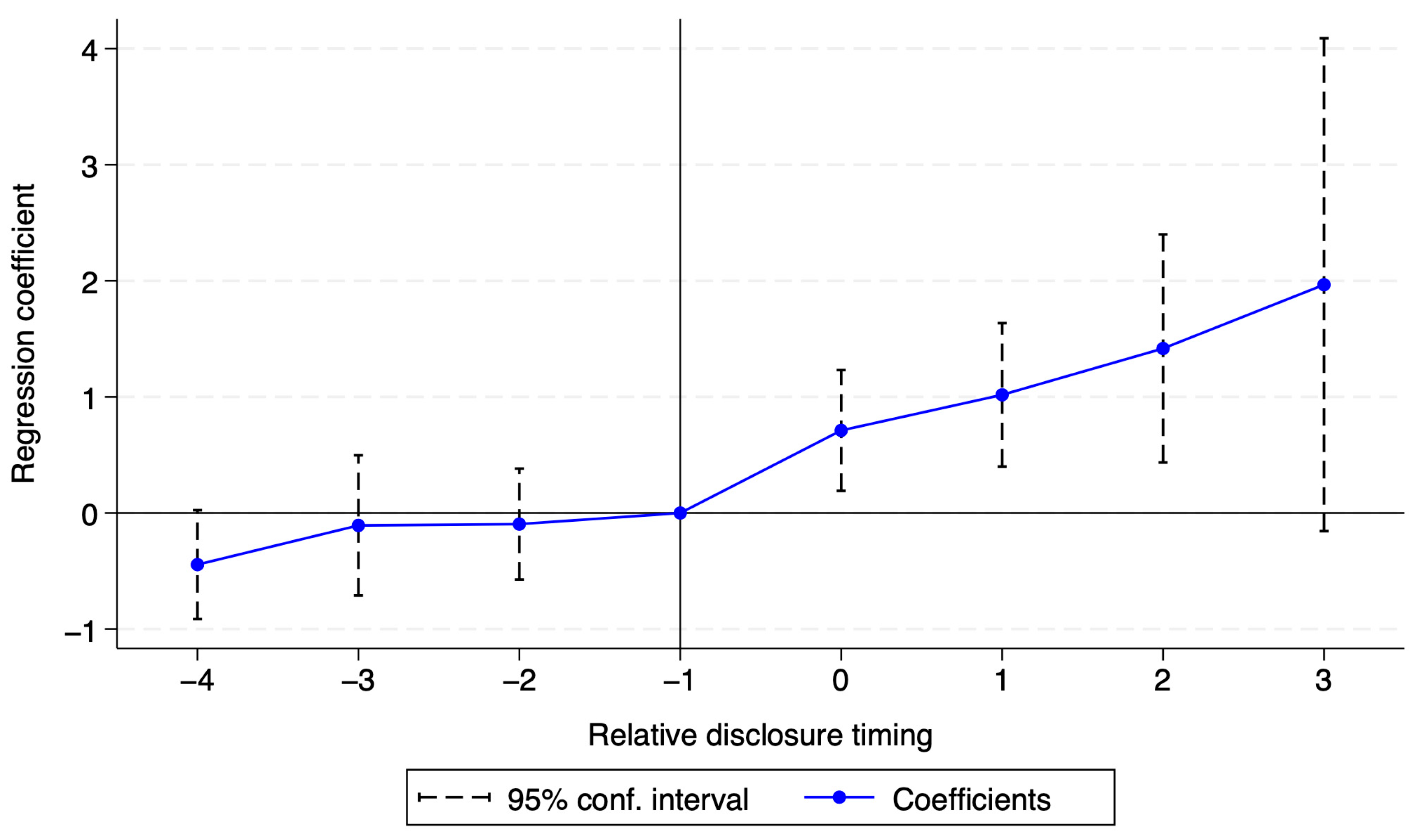

4.2.1. Dynamic Test of the Relationship Between ESG Disclosure and Market Value

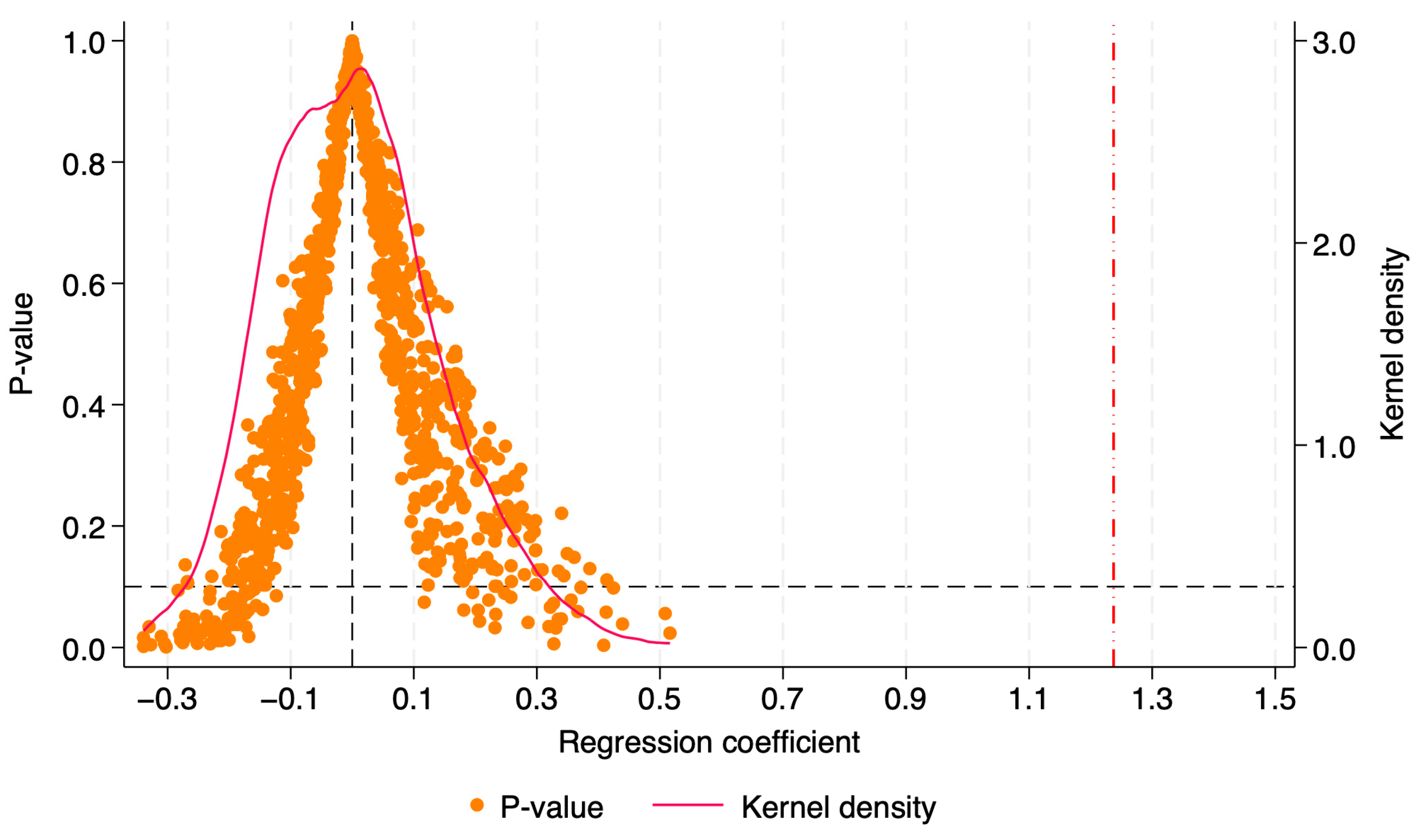

4.2.2. Placebo Test

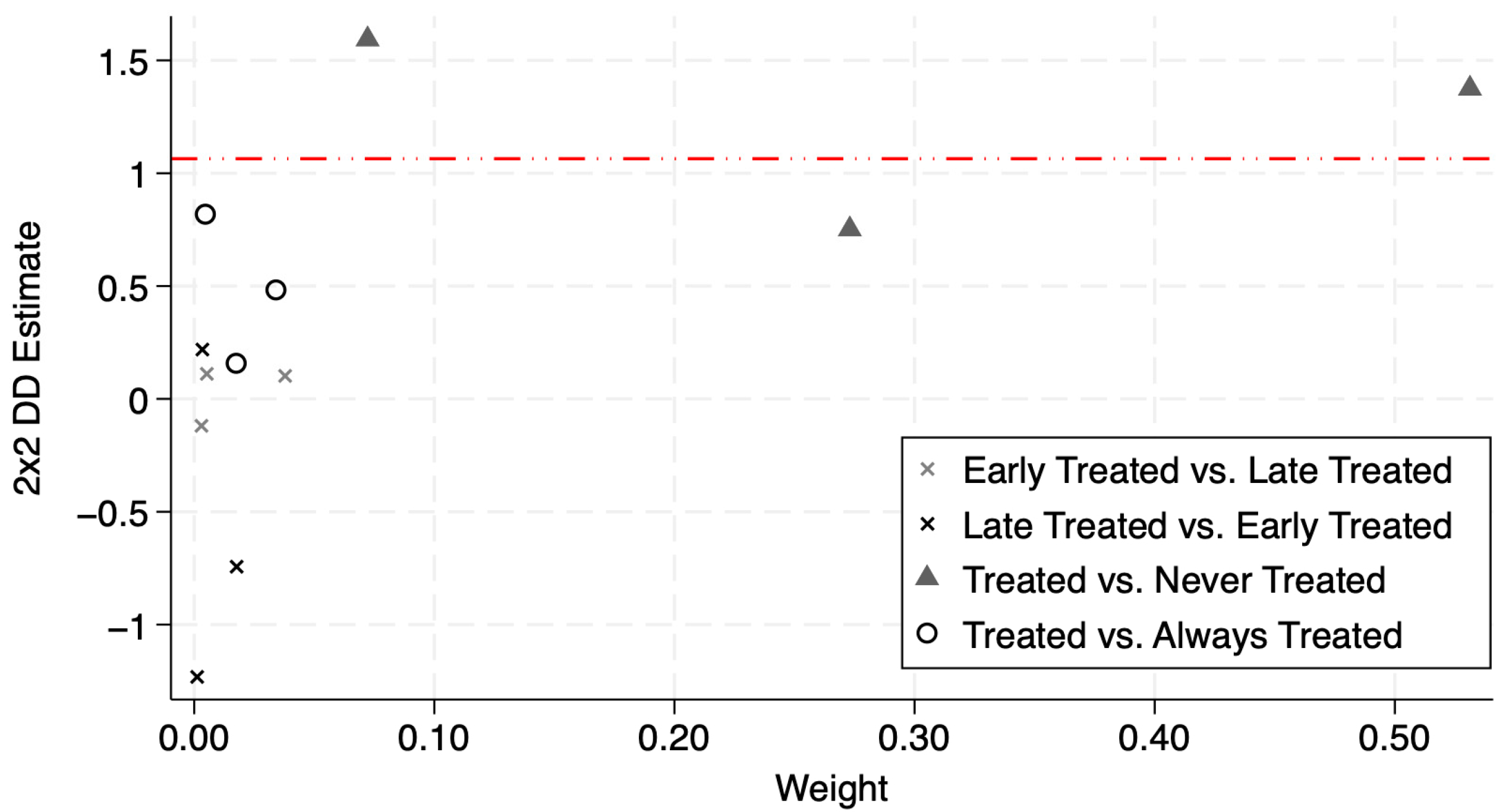

4.2.3. Goodman-Bacon Decomposition

4.2.4. Propensity Score Matching

4.2.5. System Generalized Method of Moments

4.2.6. Replacing the Core Explanatory Variable and Explained Variable

5. Mechanism Test

5.1. ESG Disclosure and Financing Constraints

5.2. ESG Disclosure and Financial Risk

5.3. ESG Disclosure and Green Investors Entry

6. Heterogeneity Analysis

6.1. Ownership Nature

6.2. CEO Duality

6.3. Environmental Efficiency

6.4. Tourism Sub-Industries

7. Discussions and Conclusions

7.1. Main Findings and Contributions

7.2. Policy and Managerial Implications

7.3. Limitations and Future Research

7.4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, H.L.; Zhou, L.Q. The role of tourism in achieving the “dual carbon” goals. Tour. Trib. 2023, 38, 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.J.; Xiao, H.J.; Wang, X. Study on high-quality development of the state-owned enterprises. China Ind. Econ. 2018, 10, 19–41. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.J.; Gu, W.J.; San, Z.Y. ESG rating divergence and analysts’ earnings forecast accuracy. China Soft Sci. 2023, 10, 164–176. [Google Scholar]

- Lian, Y.H.; He, X.Y.; Zhang, L. Corporate ESG performance and debt financing cost. Collect. Essays Financ. Econ. 2023, 1, 48–58. [Google Scholar]

- Mathath, N.; Kumar, V.; Balasubramanian, G. ESG disclosure and cost of equity: Do big 4 audit firms matter? J. Emerg. Mark. Financ. 2025, 24, 87–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Yu, S.; Mei, M.; Yang, X.; Peng, G.; Lv, B. ESG performance and corporate resilience: An empirical analysis based on the capital allocation efficiency perspective. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Xiong, L.; Peng, R. The mediating role of investor confidence on ESG performance and firm value: Evidence from Chinese listed firms. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 61, 104988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuler, D.A.; Cording, M. A corporate social performance–corporate financial performance behavioral model for consumers. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 540–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garsaa, A. How Has the COVID-19 Crisis Affected the Link Between ESG Disclosure and Firm Value? A Two-Level Analysis of European Listed Companies. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 2025, 34, 2390–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nollet, J.; Filis, G.; Mitrokostas, E. Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: A non-linear and disaggregated approach. Econ. Model. 2016, 52, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, A.S.; Orsato, R.J. Testing the institutional difference hypothesis: A study about environmental, social, governance, and financial performance. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 3261–3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.L.; Lian, Y.H.; Dong, J. Research on the impact mechanism of ESG performance on corporate value. Secur. Mark. Her. 2022, 5, 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Talan, G.; Sharma, G.D.; Pereira, V.; Muschert, G.W. From ESG to holistic value addition: Rethinking sustainable investment from the lens of stakeholder theory. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 96, 103530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, J.F.; Shan, H. Corporate ESG profiles and banking relationships. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2022, 35, 3373–3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofsson, P.; Råholm, A.; Uddin, G.S.; Troster, V.; Kang, S.H. Ethical and unethical investments under extreme market conditions. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2021, 78, 101952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, P.M.; Palepu, K.G. Information asymmetry, corporate disclosure, and the capital markets: A review of the empirical disclosure literature. J. Account. Econ. 2001, 31, 405–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.L.; Yang, Z.; Chen, J. Research on the Mechanism of ESG Promoting Corporate Performance: From the Perspective of Enterprise Innovation. Sci. Sci. Manag. ST 2021, 42, 71–89. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, R.; Chawla, S.; Dagar, V.; Kagzi, M.; Rao, A. SDG adoption and firm risk: The impact of ESG performance, investor confidence, and agency cost. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2025, 101, 104205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, I. Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) practice and firm performance: An international evidence. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2022, 23, 218–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, L.S.; Wang, Y. Corporate ESG information disclosure and stock price crash risk. Econ. Probl. 2022, 8, 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Agapova, A.; King, T.; Ranta, M. Navigating transparency: The interplay of ESG disclosure and voluntary earnings guidance. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2025, 97, 103813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, M. A Choice Model Approach to Business and Leisure Traveler’s Preferences for Green Hotel Attributes; Proquest, Umi Dissertation Publishing: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- International Capital Market Association. Market Integrity and Greenwashing Risks in Sustainable Finance. ICMA. 2023. Available online: https://www.icmagroup.org/assets/documents/Sustainable-finance/Market-integrity-and-greenwashing-risks-in-sustainable-finance-October-2023.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2024).

- Marquis, C.; Toffel, M.W.; Zhou, Y. Scrutiny, norms, and selective disclosure: A global study of greenwashing. Organ. Sci. 2016, 27, 483–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyck, A.; Lins, K.V.; Roth, L.; Wagner, H.F. Do institutional investors drive corporate social responsibility? International evidence. J. Financ. Econ. 2019, 131, 693–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammer, C.; Toffel, M.W.; Viswanathan, K. Shareholder activism and firms’ voluntary disclosure of climate change risks. Strateg. Manag. J. 2021, 42, 1850–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Yin, J. Digital transformation and ESG performance: The chain mediating role of technological innovation and financing constraints. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 71, 106387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.S.; Huang, J.W.; Chen, H.Y.; Tsay, M.H. Detecting corporate ESG performance: The role of ESG materiality in corporate financial performance and risks. N. Am. J. Econ. Financ. 2025, 76, 102370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.S.; Lu, J.C.; Li, W.A. Do green investors play a role? Evidence from corporate participation in green governance. J. Financ. Res. 2021, 5, 117–134. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, H.; Tong, M.; Chen, Y. Green investor behavior and corporate green innovation: Evidence from Chinese listed companies. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 366, 121691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergmann, D.R.; Savoia, J.R.F.; Souza, B.D.M.; Mariz, F.D. Evaluation of merger and acquisition processes in the Brazilian banking sector by means of an event study. Rev. Bras. De Gestão De Negócios 2015, 17, 1105–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T.; Levine, R.; Levkov, A. Big bad banks? The winners and losers from bank deregulation in the United States. J. Financ. 2010, 65, 1637–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Liu, A.R. From difference-in-differences to event study method. Rev. Ind. Econ. 2022, 2, 17–36. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Lu, Y.; Wang, J. Does flattening government improve economic performance? Evidence from China. J. Dev. Econ. 2016, 123, 18–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Li, X.; Li, Z. Effect of ESG rating disagreement on stock price informativeness: Empirical evidence from China’s capital market. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 96, 103651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. Industrial Classification for National Economic Activities (GB/T 4754-2017); Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. Statistical Classification of Tourism and Related Industries (2018); China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara, E.L.; Chong, A.; Duryea, S. Soap operas and fertility: Evidence from Brazil. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 2012, 4, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman-Bacon, A. Difference-in-differences with variation in treatment timing. J. Econom. 2021, 225, 254–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.W.; Acharya, K.P. Propensity score matching for causal inference and reducing the confounding effects: Statistical standard and guideline of Life Cycle Committee. Life Cycle 2022, 2, e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zheng, Z.G. Voting rights entrustment and corporate performance in the scenario of control rights transfer. Manag. World 2024, 40, 189–208. [Google Scholar]

- Blundell, R.; Bond, S. Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. J. Econom. 1998, 87, 115–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadlock, C.J.; Pierce, J.R. New evidence on measuring financial constraints: Moving beyond the KZ index. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2010, 23, 1909–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, E.I. Financial ratios, discriminant analysis and the prediction of corporate bankruptcy. J. Financ. 1968, 23, 589–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siwei, D.; Chalermkiat, W. An analysis on the relationship between ESG information disclosure and enterprise value: A case of listed companies in the energy industry in China. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2023, 10, 2207685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.C. The modern industrial revolution, exit, and the failure of internal control systems. J. Financ. 1993, 48, 831–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E.F.; Jensen, M.C. Separation of ownership and control. J. Law Econ. 1983, 26, 301–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Chen, Y.; Chen, J. How to improve industrial green total factor productivity under dual carbon goals? Evidence from China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.N.; Fei, J.H. Measurement, difference sources, and causes of green production efficiency of heavily polluted enterprises. China Population. Resour. Environ. 2021, 31, 102–109. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Definition | Obs | Mean | Std.Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tobin’s Q | Market value/ Asset replacement cost | 408 | 2.002 | 1.317 | 0.825 | 13.53 |

| discm | 1 if MSCI publishes the company’s ESG rating for the year, 0 otherwise | 408 | 0.145 | 0.352 | 0 | 1 |

| Listage | (Current year − listing year) + 1 | 408 | 14.96 | 6.902 | 1 | 29 |

| Size | Natural logarithm of total assets | 408 | 22.54 | 1.680 | 19.88 | 27.97 |

| Lev | Total liabilities/Total assets | 408 | 0.421 | 0.219 | 0.0503 | 0.895 |

| ATO | Operating revenue/ Average total assets | 408 | 0.520 | 0.400 | 0.0162 | 2.796 |

| Cashflow | Net cash flow from operating activities/Total assets | 408 | 0.0616 | 0.0742 | −0.310 | 0.292 |

| Boardsize | Natural logarithm of total board members | 408 | 2.187 | 0.193 | 1.386 | 2.708 |

| Mfee | Management expenses/Operating revenue | 408 | 0.135 | 0.161 | 0.0123 | 2.187 |

| Top1 | Largest shareholder’s shareholding/Total shares | 408 | 0.393 | 0.148 | 0.122 | 0.713 |

| Balance | Sum of shareholdings of the second to fifth largest shareholders/Largest shareholder’s shareholding | 408 | 0.622 | 0.507 | 0.0267 | 2.577 |

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Variable | Tobin’s Q | Tobin’s Q |

| discm | 1.0560 ** | 1.2372 *** |

| (0.4048) | (0.3826) | |

| Listage | 0.0527 * | |

| (0.0292) | ||

| Size | −0.4287 ** | |

| (0.1952) | ||

| Lev | 0.5275 | |

| (0.6614) | ||

| ATO | 0.2074 | |

| (0.3144) | ||

| Cashflow | 3.2899 ** | |

| (1.3197) | ||

| Boardsize | −0.0324 | |

| (0.4923) | ||

| Mfee | 0.8569 *** | |

| (0.3103) | ||

| Top1 | −2.1045 | |

| (1.3783) | ||

| Balance | −0.2298 | |

| (0.4128) | ||

| _cons | 1.7160 *** | 10.8417 ** |

| (0.1237) | (4.2667) | |

| Controls | No | Yes |

| Firm Effect | Yes | Yes |

| Year Effect | Yes | Yes |

| Obs. | 408 | 408 |

| Adj.R-squared | 0.2342 | 0.3009 |

| DID Comparison | Avg DID Est | Weight |

|---|---|---|

| Early Treated vs. Late Treated | 0.092 | 0.046 |

| Late Treated vs. Early Treated | −0.622 | 0.022 |

| Treated vs. Never Treated | 1.199 | 0.877 |

| Treated vs. Always Treated | 0.410 | 0.056 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tobin’s Q | Tobin’s Q | Tobin’s Q | |

| 1:1 Nearest Neighbor Matching | 1:3 Nearest Neighbor Matching | Kernel Density Matching | |

| discm | 0.7013 *** | 0.7131 *** | 0.9041 *** |

| (0.2480) | (0.2443) | (0.2495) | |

| _cons | 1.6426 | 1.4970 | 1.8609 * |

| (1.6064) | (0.9571) | (0.9376) | |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Obs. | 161 | 270 | 394 |

| Adj.R-squared | 0.3069 | 0.2878 | 0.3146 |

| Variable | (4) | (5) |

|---|---|---|

| Tobin’s Q | Tobin’s Q | |

| Two-Way Fixed Effects Model (TWFE) | Generalized Method of Moments Model (GMM) | |

| discm | 0.9588 *** | 1.1850 *** |

| (0.2887) | (0.3969) | |

| L.Tobin’s Q | 0.4522 *** | 0.7041 *** |

| (0.1482) | (0.1456) | |

| _cons | 14.4669 ** | - |

| (6.9970) | - | |

| Controls | Yes | Yes |

| Firm Effect | Yes | Yes |

| Year Effect | Yes | Yes |

| Obs. | 353 | 353 |

| Adj.R-squared | 0.4264 | - |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tobin’s Q | PBratio | PTratio | |

| discs | 0.4223 ** | ||

| (0.1767) | |||

| discm | 2.0300 *** | 1.2903 *** | |

| (0.6706) | (0.4105) | ||

| _cons | 7.8354 | 28.2994 *** | 8.6584 ** |

| (4.9950) | (6.5528) | (4.2226) | |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Obs. | 408 | 408 | 393 |

| Adj.R-squared | 0.2392 | 0.3788 | 0.2534 |

| Mediating Effect of Financing Constraints | Mediating Effect of Financial Risk | Mediating Effect of Green Investors Entry | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

| SA | Tobin’s Q | Z-Score | Tobin’s Q | GInv | Tobin’s Q | |

| discm | −0.0945 *** | 1.0524 ** | 2.9449 ** | 0.6626 *** | 0.4770 ** | 0.9389 *** |

| (0.0290) | (0.4024) | (1.3476) | (0.2045) | (0.1871) | (0.3205) | |

| SA | −1.9560 ** | |||||

| (0.8858) | ||||||

| Z-score | 0.1951 *** | |||||

| (0.0459) | ||||||

| GInv | 0.6255 *** | |||||

| (0.1668) | ||||||

| _cons | 5.6197 *** | 21.8340 *** | 7.9309 | 9.2942 ** | −0.6725 | 11.2623 *** |

| (1.4277) | (7.0098) | (12.5376) | (3.5498) | (2.1783) | (3.4101) | |

| Sobel test | 0.1849 * | 0.5746 * | 0.2984 ** | |||

| Bootstrap test | 0.1214 ** | 0.3429 * | 0.2257 ** | |||

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Obs. | 408 | 408 | 408 | 408 | 408 | 408 |

| Adj.R-squared | 0.7145 | 0.3168 | 0.3031 | 0.6076 | 0.1172 | 0.4022 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tobin’s Q | Tobin’s Q | Tobin’s Q | Tobin’s Q | Tobin’s Q | Tobin’s Q | |

| Non-SOE | SOE | Separation | Duality | Low GTFP | High GTFP | |

| discm | 0.6558 | 1.5257 *** | 1.4429 *** | −0.0941 | 2.5817 *** | 0.3943 |

| (0.5008) | (0.4979) | (0.4274) | (0.3269) | (0.5886) | (0.2483) | |

| _cons | 12.3491 *** | 17.8325 ** | 13.6271 | 12.7218 | 11.5573 | 15.9676 ** |

| (3.8092) | (7.7277) | (8.1401) | (11.7010) | (12.9147) | (7.1502) | |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Obs. | 126 | 282 | 329 | 79 | 198 | 197 |

| Adj.R-squared | 0.3500 | 0.3211 | 0.2939 | 0.5371 | 0.3562 | 0.4304 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accommodation and Catering | Tourism Transportation | Tourism Sightseeing | Tourism Comprehensive Services | |

| discm | 1.4651 *** | 0.3889 | 1.2303 *** | 2.1750 |

| (0.3128) | (0.2281) | (0.1824) | (1.4398) | |

| _cons | 37.3722 ** | −12.1873 | 15.0477 ** | 14.4567 ** |

| (13.6309) | (20.8227) | (5.4986) | (5.2187) | |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Obs. | 68 | 87 | 125 | 128 |

| Adj.R-squared | 0.7469 | 0.3507 | 0.5962 | 0.2930 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Q.; Jia, Z. ESG Performance and Tourism Enterprise Value: Impact Effects and Mechanism Analysis. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9550. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219550

Wang Q, Jia Z. ESG Performance and Tourism Enterprise Value: Impact Effects and Mechanism Analysis. Sustainability. 2025; 17(21):9550. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219550

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Qianqian, and Zeqi Jia. 2025. "ESG Performance and Tourism Enterprise Value: Impact Effects and Mechanism Analysis" Sustainability 17, no. 21: 9550. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219550

APA StyleWang, Q., & Jia, Z. (2025). ESG Performance and Tourism Enterprise Value: Impact Effects and Mechanism Analysis. Sustainability, 17(21), 9550. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219550