2.1. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and Sustainable Tourism

Peace and prosperity around the world were guided by the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which the United Nations approved in 2015 [

18]. The UN continues to support the SDGs, as Goal 8.9 aims to make tourism sustainable by enhancing local culture and products, as well as Goal 17, focusing partnership development to ensure measurable progress in sustainable development and institutional or organizational interaction between all sectors. This twin purpose sets urban tourism not only as an engine of economic development, but also as a tool for sustainable inclusive growth and environmental conservation and cooperative governance. Although tourism is a major part of sustainable development, some researchers argued that existing methods have proven to be less sustainable than desired [

19]. Those studying tourism have pointed out that there has been undue focus on coupling tourism with sustainability rather than restructuring the institutions underpinning the tourism system [

20]. According to Rutty and his team [

21], there is usually greater emphasis on profit than on caring for the environment and society. As a result, places like Venice have now faced local protests and pressure on their environment [

22].

The World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) defines sustainable tourism as “tourism that takes full account of its current and future economic, social, and environmental impacts” [

23]. The UNWTO, 2023 [

24] believes that it should address the needs of visitors, tourism entrepreneurs and those who live at these destinations. The goal of sustainable tourism is to retain the natural and cultural value of the area, enhance the local community’s income, and lessen its harm to nature [

25]. In this way, tourism constitutes a multi-faceted system articulating economic performance (accomplished through job creation and income generation), cultural vitality (achieved via heritage conservation and identity) and environmental responsibility (enacted through preservation and low carbon measures). Researchers have shifted more attention to tourism’s contribution to achieving the SDGs. According to a recent paper by Pahrudin et al. [

26], sustainability is now a key aspect studied in tourism research, mostly in tourism marketing and management, since tourism must match up with global sustainability targets. These studies also emphasized the necessity to apply SDGs at the city level with quantifiable benchmarks such as SDG 8.9.1 (a proportion of tourism employment and share in GDP) and SDG 17.14.1 (policy coherence for sustainable development). In a parallel example, Puah et al. [

27] reviewed the economic value of tourism in Malaysia and showed that the sector helps the local economy, adds jobs, and improves living standards, largely in urban areas undergoing economic development and growth. They demonstrate that sustainable tourism and economic development are mutually reinforcing, particularly in low middle-income countries looking for inclusion and resilience. The central government has made sure that SDG priorities are part of China’s tourism and countryside revival policies through its program called “Beautiful China Initiative” [

28]. This policy direction resonates with the recent acknowledgment of the role that medium-sized cities like Nanyang can play as “living laboratories” for real-world experience in promoting SDG-centered tourism models to reconcile economic transformation and sustainability. The Sustainomics approach highlights the interconnectedness of economic development, social justice and environmental preservation in achieving sustainable development over the long term. In this perspective, sustainable urban tourism, as in Nanyang City, can become a practical expression of Sustainomics itself through the integration between (economic), preservation, and inclusivity (social) and resource conservation (environmental). Therefore, by focusing on SDG 8.9 and 17 in Nanyang City’s urban tourism governance, this study’s strategy helps to contextualize Sustainomics at the city level and model multi-dimensional sustainability assessment.

2.2. Urban Tourism and Sustainable Development in Nanyang City

Urban tourism in Nanyang City demonstrates how local governments can operationalize SDGs 8.9 and 17 through cultural events, economic inclusion, and cross-sector partnerships. A rising trend in urban tourism, especially in Chinese cities, is event tourism, guided by efforts to add value to unique cultural, historical, and artistic backgrounds and boost their appeal in the economy [

29]. Exhibitions, art fairs, and local festivals encourage visitors to visit and let the area become known. In the bigger picture, Lee et al. [

30] and Armbrecht and Andersson [

31] noted that Ritchie and Beliveau [

32] were the first to identify the economic value of tourism events. Later studies [

33,

34,

35] investigated how events influence destination image, build brand equity, and local economic structures, linking cultural celebration to tourism marketing and emotional engagement. The Wuhou Temple Cultural Tourism Festival in Nanyang City is an excellent model for how the story of history, traditional music, and theater can be used to serve both tourism and community well-being [

17,

36]. The Zhuge Liang Cultural Festival is a festival with performances, storytelling, and community events that are good for business and locals alike [

36]. As a result, the city uses its Han Dynasty history and success in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) to hold events that bring together people from all over the world [

37,

38]. Instances like this serve not only to safeguard intangible heritage but also to build intersectoral relationships between artists, micro-businesses, and local government that generate employment opportunities and contribute to the achievement of SDG 8.9 through culture-led development.

In economic terms, tourism provides a local economic development vehicle. Researchers assess how tourism improves the economy by checking income, job creation in tertiary industries, and development in individual earnings. With the global COVID-19 outbreak and along with, tourism provided a 148% boost to the global economy, going from USD 983.5 billion to USD 1458.7 billion from 2010 to 2019, making it clear how powerful tourism is for the world’s economies [

39,

40]. The Henan Provincial Statistics Bureau pointed out that Nanyang’s tourism sector employs more than 150,000 people, highlighting its importance for urban job creation. Empirical investigations revealed that the expansion of tourism was positively associated with household income growth and job diversification, especially for younger households and those with lower incomes [

19,

41,

42,

43]. Hospitality, retail, and transportation services are driven by events and exhibitions that lead to inclusive growth [

44]. In addition, Moore and Quinn [

45] argue that art-based festivals have a greater economic impact in rural and peri-urban areas. Nanyang City’s tourism model reflects this process by passing on development benefits to its neighbouring Neixiang County, contributing to the harmonious development of regions under SDG 8.

Just as significant is Nanyang city’s shared governance, a theme of SDG 17 on partnership. MacDonald et al. [

46] highlighted that strong partnership between the public and private sectors is fundamental for achieving sustainable development. In tourism, local governments, private investors, civil society, and international investors are expected to cooperate [

47,

48]. Nanyang City has developed innovative partnerships with local universities, the China Association of Tourism and Culture, and digital platforms, Ctrip and Meituan, which aid in data collection and evidence-based new policymaking. These partnerships lead to more money, greater knowledge exchange, and boost innovation and how the firm survives tough times [

49]. As an example, data-sharing agreements give bureaus insights into tourism so they can distribute tourists better, improve how festivals are arranged, and lessen the burden on both infrastructure and the environment [

50]. Further, organizations from different industries are now cooperating to organize green events [

51]. In 2023, the TCM Expo in Nanyang launched “Low-Carbon Tourism Events,” including eco-friendly materials, waste sorting, and carbon-cutting transportation to lessen emissions. This co-governance model demonstrates how Nanyang’s policies align with SDG 17.14.1’s goal of improving policy coherence for sustainable development.

Tourism also functions as a socio-economic equalizer, provides employment for many, and influence city-country relationships, as well helps connect people doing informal jobs with formal work [

52,

53,

54,

55]. Due to tourism in Nanyang City, the Hospitality and cultural sector offers new jobs to youth and women as well as Artisans, while the transport sector provides additional logistics and service jobs. The most recent Nanyang Urban Development Report revealed that tourism-related services in 2023 created more than 20% of new jobs in the tertiary sector, proving that the industry helps support growth in employment outside major cities [

56]. Furthermore, the Wuhou Festival helps to create a temporary market for local vendors, caterers, singers, and artisans. These short-term jobs usually help marginalized people become involved in urban economies, which supports inclusive development, as discussed in SDG 8 [

57]. Also, by creating jobs that young people can take, city tourism can hold back or even reverse the migration of people from urban areas [

58].

2.3. Challenges and Research Gaps

Although Nanyang City offers a strong blueprint for sustainable tourism, several issues stand in the way of fully adopting Sustainable Development Goals 8.9 and 17. A major issue is that many visitors to festivals can cause a lot of stress on the environment, using up water, leading to more waste, and raising the overload on transportation remain significant challenges in operationalizing SDG indicators at the municipal level. In addition, resources, for example, water and transportation, are strained by festival tourism, and commercialization can also challenge the authenticity of local culture [

17,

59]. The lack of access to tourism data limits academic research and policy comparison, also leading to a concentration in urban areas rather than peripheral areas [

60]. These tensions are symptomatic of a much larger global discussion about the balance between growth and sustainability in tourism governance. According to Rutty et al. [

21], argue that policymakers must weigh trade-offs between economic expansion, social inclusion, and environmental protection [

61]. In addition, there is a theoretical and empirical blank on how partnerships at the city level, collaborative data sharing systems, and participatory governance structures can promote the achievement of SDGs, with an emphasis on urban tourism within medium-sized Chinese cities, such as Nanyang City.

2.4. Development of Research Hypotheses

To develop survey items aligned with each research question, this study adapted and integrated measurement indicators from established scholarly works and institutional frameworks relevant to sustainable urban tourism and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This study extends existing tourism–Sustainable Development Goals (tourism-SDG) models by incorporating governance theory and context-based sustainability perspectives, to understand how urban tourism can facilitate the delivery of SDGs in a mid-sized Chinese city. In contrast with previous studies on enclave tourism or high-level indicators of development, this study prioritises the governance practices at the local level, the involvement of stakeholders, and heritage flows from an urban standpoint, identifying Nanyang City as a unique paradigm for region-specific considerations in developing sustainable tourism projects. Special attention was paid to how SDG indicators 8.9.1 (tourism contributions to GDP and jobs) and 17.14.1 (policy coherence for sustainable development) could be operationalised using measuring constructs as well as empirical data where such were available or feasible. For Research Question 1 (RQ1), which explores how urban tourism in Nanyang contributes to achieving SDG 8.9, focusing on the promotion of local culture, employment generation, and sustainable economic growth, the survey items were adapted from the United Nations World Tourism Organization [

62]. In addition, items were grounded and adapted from [

63], who emphasized the relationship between community involvement and sustainable tourism development. Reports published by the World Travel and Tourism Council in 2021 and the United Nations Development Programme in 2020 provided valuable insights into the role of tourism in driving economic growth and creating opportunities for local people. For Research Question 2 (RQ2), which investigates the challenges and opportunities related to implementing sustainable tourism practices in alignment with SDG 8.9, the survey items were informed by [

64]. Thanks to the scale, it is easy to contrast opinions on how to deal with infrastructure demands, the environment, and sustainable abilities. More opinions came from [

65,

66], showing that problems mainly stem from having no laws, too many tourists, and harm to nature.

For Research Question 3 (RQ3), which examines the extent to which multi-stakeholder partnerships, specifically collaborations among public institutions, private enterprises, and local communities, contribute to urban tourism development in line with SDG 17, the survey items were developed using governance frameworks from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development [

67]. Supporting theory was found in [

68], who directed attention to the benefits of community involvement and partnering in tourism policies. Lastly, for Research Question 4 (RQ4), which explores how strengthening policy frameworks and community engagement can improve Nanyang City’s capacity to achieve SDG 8.9 and SDG 17 through urban tourism development, survey items were developed with reference to [

69] Tourism Planning and Policy, which stresses participatory governance, community empowerment, and integrative policy frameworks. Indicators 17.14.1 of the UN SDGs on “enhancing policy coherence for sustainable development” were also looked at, stressing the importance of both cross-sectoral cooperation and including all groups in decisions. Drawing from the objectives and questions of this research, hypotheses are set up to determine the links between urban tourism and sustainable development in Nanyang City, mostly focusing on Goals 8.9 and 17 of the Sustainable Development Goals. Below is the list of hypotheses used in this research:

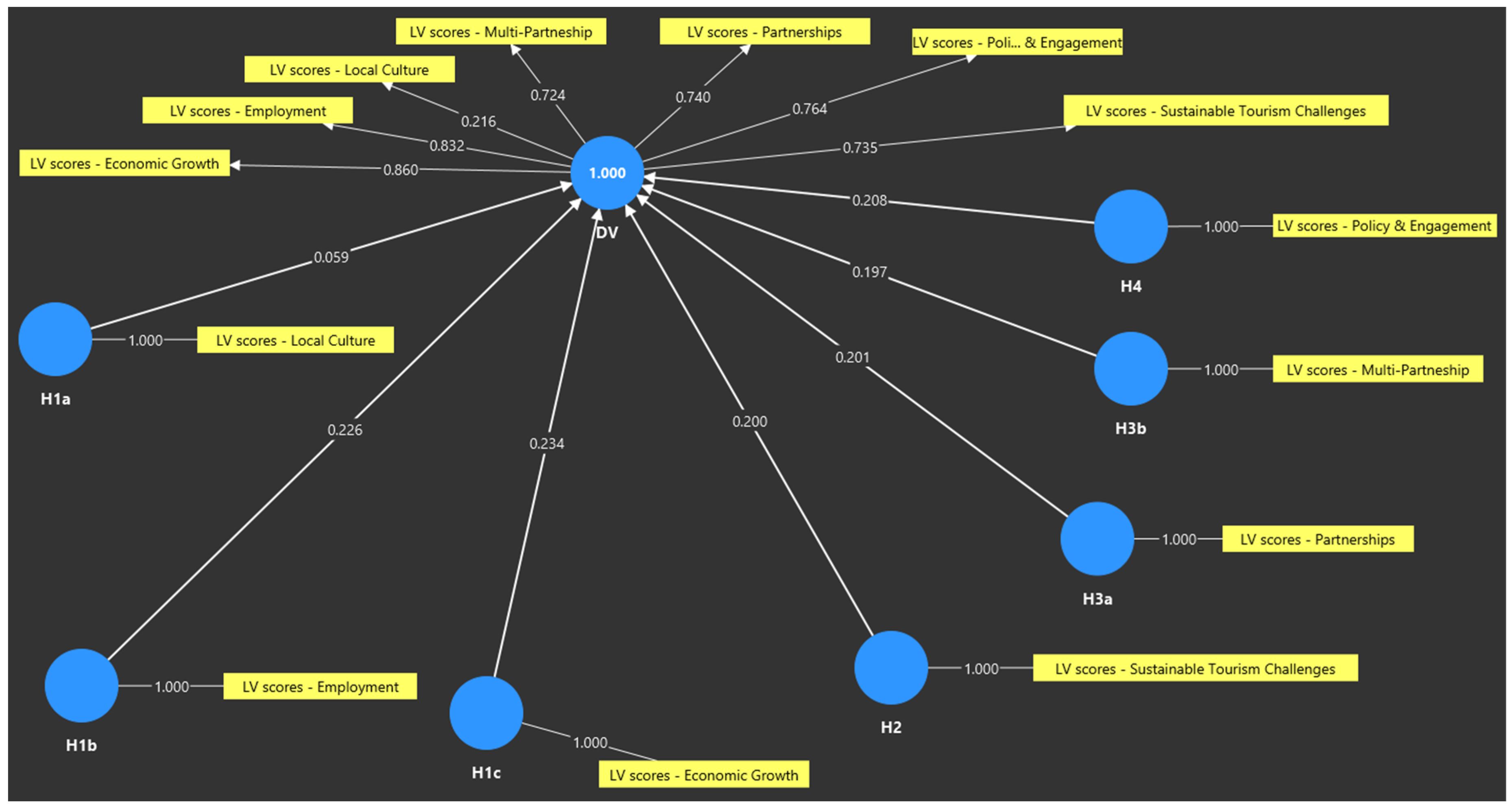

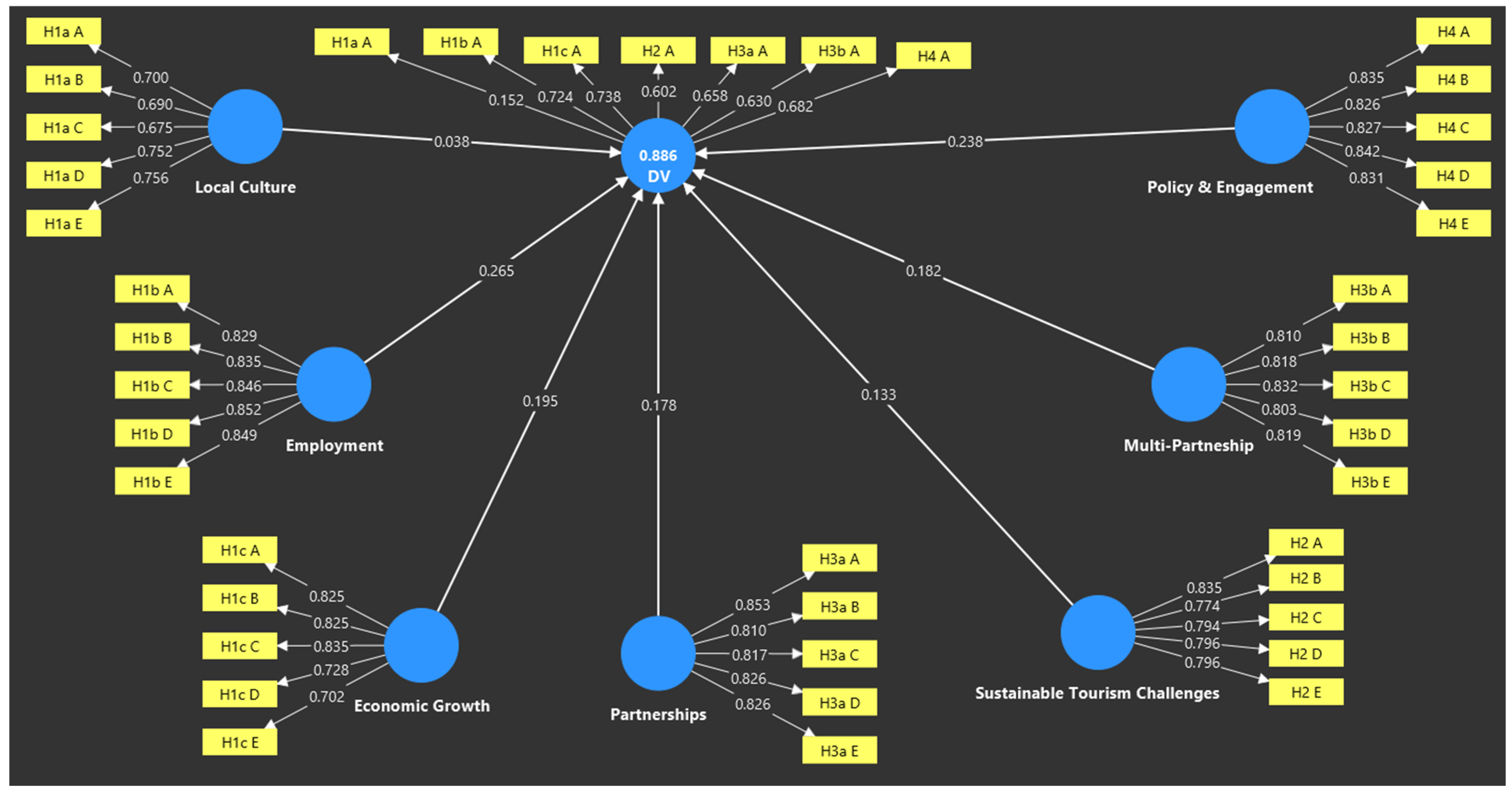

H1a: Urban tourism in Nanyang City positively contributes to the promotion of local culture, thereby supporting the achievement of SDG 8.9.

H1b: Urban tourism in Nanyang City positively influences employment generation in the local tertiary sector, facilitating progress toward SDG 8.9.

H1c: Urban tourism in Nanyang City significantly promotes sustainable economic growth in alignment with SDG 8.9.

H2: Various challenges negatively affect the implementation of sustainable tourism practices in Nanyang City, whereas identified opportunities facilitate their successful adoption in alignment with SDG 8.9.

H2a: Structural, environmental, and policy-related challenges negatively affect the implementation of sustainable tourism practices in Nanyang City, thereby hindering progress toward SDG 8.9.

H2b: Institutional innovation, cultural resources, and stakeholder collaboration positively influence the successful adoption of sustainable tourism practices in Nanyang City, facilitating alignment with SDG 8.9.

H3a: Institutional coordination among governmental agencies, private enterprises, and tourism organizations (Multi-stakeholder partnerships) significantly enhances policy coherence and governance effectiveness in urban tourism development in Nanyang City, consistent with SDG 17.

H3b: (Multi-stakeholder partnerships) Community co-production that, through local participation, shared decision-making, and cultural co-creation, can strengthen the sustainability and long-term impact of urban tourism initiatives in Nanyang City, contributing to both SDG 8.9 and SDG 17.

H4: Policy coherence and participatory governance mechanisms jointly impacting the relationship between partnerships and SDG advancement, significantly improving Nanyang City’s capacity to achieve SDG 8.9 and SDG 17 through sustainable urban tourism development.