Abstract

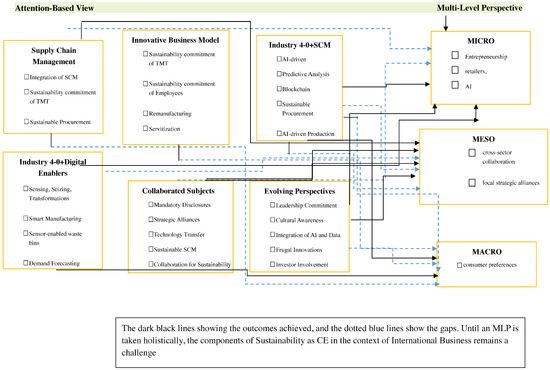

The circular economy (CE) is increasingly central to international business, promoting resource efficiency and mitigating environmental impacts. However, existing literature often examines isolated elements—such as supply chains, innovation, or business models—resulting in a fragmented understanding of circularity within this domain. To address this gap, the present study conducts a systematic literature review of 128 PRISMA-screened articles, employing thematic analysis to identify six prevailing themes. Despite growing interest, the absence of a cohesive framework has led to disjointed inquiries that overlook the systemic complexities of embedding CE in international business. Anchored in the Attention-Based View and synthesized through the Multi-Level Perspective framework, this review reveals critical research gaps. At the micro level, limited attention is given to entrepreneurship, retailer engagement, and the integration of artificial intelligence. At the meso level, studies insufficiently address cross-sector collaboration and localized strategic alliances. At the macro level, consumer-driven circularity remains underexplored. This study proposes an integrative framework to bridge these levels, advancing both theoretical understanding and practical application. By aligning diverse insights, it delineates strategic pathways for institutionalizing CE principles in international business, thereby supporting sustainable development and environmental stewardship.

1. Introduction

Research on the circular economy (CE) has increased in recent years, demonstrating a growing focus and managerial interest in sustainability-focused business models. The literature on international business (IB) has primarily focused on supply chain optimization and corporate social responsibility (CSR) [1]. Still, recent studies underscore the significance of integrating CE principles, which combine environmental outcomes with economic challenges [2]. However, despite the increasing attention to CE adoption, extant studies provide limited insights into how IB can operationalize the CE across geographically dispersed supply chains. Specifically, prior research has rarely examined the capabilities, institutional pressures, and interorganizational dynamics that influence CE implementation in IB contexts. Even when these aspects have been studied, the research has been fragmented. Given this gap, and considering that globalization presents both opportunities and complexities associated with sustainability, this study systematically reviews the literature to synthesize key themes, identify conceptual shortcomings, and propose a comprehensive agenda for future CE research and practice in IB.

Despite the growing body of scholarship on the CE [3,4], research in the IB context remains scattered and conceptually underdeveloped. Prior reviews primarily focus on CE implementation at the firm or policy level [5,6], with limited integration of multi-level dynamics and strategic agency in global business systems. Moreover, while the CE is frequently associated with sustainability outcomes, the mechanisms through which firms and actors enable, adapt to, or resist CE transitions across global contexts are insufficiently theorized [4]. This study addresses this fragmentation by systematically synthesizing the CE literature in the IB context and applying the Attention-Based View (ABV) [7] to examine how organizational attention shapes the strategic prioritization of CE-related initiatives. The ABV framework provides a valuable theoretical lens to explain why certain CE domains attract sustained attention, while others remain peripheral to global corporate strategies. A systematic review is particularly suited for uncovering such latent patterns, as it enables thematic integration across heterogeneous studies and facilitates the identification of conceptual gaps, underexplored domains, and opportunities for theoretical advancement.

The CE offers a pathway to address depleting resources and increasing consumption demand [8] amid a backdrop of global turbulence, including conflict and geopolitical instability. However, unprecedented efforts toward sustainability through international collaboration highlight the critical need to focus on Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 12, which addresses responsible production and consumption [9]. As one of the most promising sustainability practices, the CE fosters competitiveness and innovation, driving firms’ long-term financial growth. However, achieving short-term economic gains through the CE remains a challenge [10]. Implementation of the CE requires a long-term strategic plan.

Understanding the key domains and barriers is essential for the successful adoption of circular loops in IB operations. The concept of the CE has been embraced across various economies, business contexts, and environments; however, it does not originate from a specific date or individual [11]. While the roots of sustainability can be traced to global societies that respect nature and conserve resources, the CE has evolved into a widely adopted business model with contributions from architects and economists, including Walter Stahel and the Ellen MacArthur Foundation [12]. Historically, humans—especially businesses—have exploited the environment and its resources for economic gain, leading to critical sustainability issues. IB, owing to its cross-border supply chains, consumes more resources than other businesses. Although the CE has been discussed for the past four decades, IB has only recently actively shifted from linear economic models to the CE. This shift is attributed to the numerous environmental and social benefits associated with the CE [13]. Moreover, according to Walter Stahel and the Ellen MacArthur Foundation [12], significant global initiatives have been undertaken to promote sustainability, with a particular focus on SDG 12: responsible production and consumption [9]. The United Nations SDG guidelines emphasize IB and the CE as two key imperatives.

Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic acted as a transformative force, driving numerous shifts across both academic and industrial domains [14,15,16]. The pandemic highlighted vulnerabilities in global supply chains [17], led to policy changes, and accelerated the adoption of digital technologies [18]. These disruptions have culminated in heightened awareness of environmental issues, a shift toward healthier lifestyles, and greater global collaboration to address the ongoing ecological crisis. Consequently, governments worldwide have expedited initiatives to promote research on sustainability, further emphasizing the need for studies on the challenges, benefits, and strategies for achieving sustainable economic models. As a result, research in the fields of CE and sustainability in IB has increased markedly. Altogether, these dynamics convey that the circular economy is a market necessity as well as a key strategy for competitive advantage of the firms, particularly in International Business. The circular economy is one sustainability component that addresses pressing challenges of resource scarcity and supply chain fragility in International Business. This makes firms comply with ESG regulations and meet evolving consumer expectations.

The objectives of this study are fourfold: (1) to systematically synthesize scholarly literature on the CE within IB, identifying the dominant themes; (2) to examine how managerial and organizational attention—as conceptualized in the ABV—shapes the selection, prioritization, and diffusion of CE-related strategies in IB; (3) to interpret the evolution and gaps in CE scholarship using a Multi-Level Perspective (MLP); (4) to offer a structured agenda for future research and practice by integrating ABV and MLP insights. This study is designed to examine the factors contributing to the adoption of the CE as a crucial strategy for sustainability in IB. Section 2 outlines the research approach, data collection methods, and analytical tools. Section 3 presents key insights and findings, offering a critical analysis of the obstacles impeding CE adoption. The discussion in Section 4 highlights the practical and managerial implications of the findings and proposes future research directions. The study concludes in Section 5 with a synthesis of the research outcomes, emphasizing their significance in advancing sustainability in IB.

1.1. Attention-Based View

Introduced by Ocasio [7], the ABV posits that organizational behavior is fundamentally shaped by what decision-makers focus their attention on. While it has been widely applied in strategic decision-making and innovation research [19], its application in the domain of sustainability in IB remains limited. This is a critical oversight, given that sustainability-related decisions, especially those involving complex global supply chains, require navigating competing institutional logics, regulatory demands, and stakeholder expectations across borders. Recent studies suggest that attention allocation is pivotal in explaining why certain multinational enterprises (MNEs) engage more deeply in sustainability than others. For instance, Bansal et al. [20] argue that sustainability choices are not only externally driven but also filtered through the internal attention structures of top executives. Similarly, Roszkowska-Menkes et al. [21] shows that even firms adhering to similar reporting standards differ significantly in their sustainability disclosures, often engaging in selective disclosure—a form of symbolic decoupling between communication and practice. Therefore, the ABV provides a powerful explanatory mechanism for understanding how and why sustainability becomes a strategic priority in IB settings.

1.2. The Multi-Level Perspective (MLP) Framework

The Multi-Level Perspective (MLP) is the much-needed framework to explain the shift toward a circular economy (CE) in international business contexts [22,23]. MLP segregates complex solutions into multi-level—micro-level, meso-level, and macro-level environmental trends [24]. Sustainability is multidimensional; therefore, any approach bringing a fruitful solution embracing sustainability is essentially multi-fold. MLP is consequently the ideal framework for this, working on many levels to provide insight into practical approaches.

The MLP to the CE literature in international business brings in a structured interpretation of findings across these levels. In this study, the micro-level captures firm- and entrepreneur-led innovations, including retailer engagement strategies and the application of artificial intelligence in CE practices, which remain underexplored. The meso level highlights industry and supply chain dynamics, where gaps exist in understanding cross-sector collaborations and local strategic alliances that could accelerate CE adoption. The macro level reflects global market forces, consumer preferences, and policy landscapes, although research addressing the role of consumer-driven circularity in shaping international business strategies is limited [25].

The study proposes a conceptual framework based on the reviewed literature and theoretical perspectives as depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework.

2. Materials and Methods

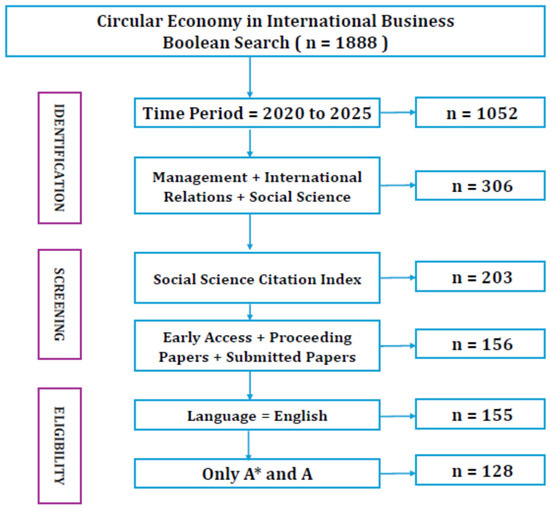

A systematic literature review is an invaluable method for obtaining a comprehensive understanding of a given topic [26] and facilitating substantive contributions to the field. This review adheres to specific criteria, focusing on articles sourced from journals indexed in the Social Science Citation Index (SSCI), ensuring high-quality content owing to the journals’ rigorous peer-review processes [27]. The screening, selection, and shortlisting of research articles were conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. The research methodology is illustrated in the flow diagram in Figure 2. The literature search included articles published until 6 March 2025. The authors conducted an in-depth analysis of each study to elucidate the factors contributing to stagnation in the CE within the context of IB and to propose a research agenda and practical applications.

Figure 2.

Process of Document Search and Selection in the Systematic Review. A* denotes the ABDC journal ranking, indicating one of the highest quality categories.

The Web of Science database was used to identify relevant research papers for the systematic literature review, chosen for its prioritization of article quality, ease of access to journal metrics, and comprehensive international coverage of the topic. Additionally, the articles were filtered and integrated using various tools to complete the systematic literature review.

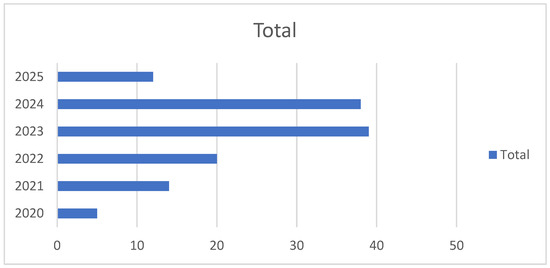

PRISMA guidelines were implemented to identify, screen, and establish eligibility criteria for research papers in the systematic literature review. This review focuses on the Boolean search terms “circular economy” and “sustainability” for the period 2020–2025. The authors selected this time frame for many reasons. First, we selected this timeframe because of a clear shift in the literature—there’s been a surge in CE publications since 2020, as shown in Figure A1 (Appendix A). This growth reflects how CE has gained traction in both academic circles and industry, especially within international business contexts. Second, focusing on the post-2020 period captures emerging perspectives shaped by major global disruptions: the pandemic initially, then the rapid advancement of AI and digital technologies. These events fundamentally altered how international businesses approach strategy, manage supply chains, and navigate regulatory landscapes—all relevant to CE implementation. Finally, examining 2020–2025 ensures we’re working with recent knowledge that directly applies to today’s international business environment. We didn’t restrict publications by language, as this didn’t meaningfully impact our findings, though we did narrow our search to Management and Business domains to keep the scope manageable.

During abstract screening, a gap was identified in the literature on IB and the CE. To confirm the limited literature on IB, a Boolean search using “circular economy” and “sustainability” yielded 1888 research articles. After applying publication criteria, 1052 articles remained. The 2020–2025 period was chosen to capture the real impact of post-COVID research. Further identification was conducted using subject criteria in management, social science, and international relations to ensure alignment with the chosen topic. The quality of the articles was further validated using the SSCI, which identified 203 SSCI-indexed articles from over 3400 scholarly journals, providing access to an extensive repository of social science research. The screening process included early-access articles, proceedings, and submitted papers to ensure research quality, culminating in 156 articles. Eligibility was confirmed using the language criterion “English,” resulting in 155 articles. Finally, only A*- and A-ranked journals were selected from the Australian Business Deans Council (ABDC) journal rankings, yielding 128 articles (Figure 2).

The SSCI is updated regularly to ensure that users have access to the latest research in their fields. A team of experts rigorously selects the journals included in the SSCI based on their quality and impact. Only A* and A-ranked journals were included from the ABDC rankings. The journals from which the articles were taken are listed below (Table 1) in descending order of the number of articles from each journal. This review has been conducted following the PRISMA 2020 guidelines (Supplementary Materials) and has been registered with the Open Science Framework (OSF). The registration details are publicly available at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/TW5F7 (accessed on 21 September 2025).

Table 1.

Journals Included in the Systematic Review, Ranked by Number of Articles Extracted.

Thematic Analysis

The authors employed a systematic approach to synthesize and scientifically extract patterns prevalent in the CE literature in the context of IB, using the 128 articles screened and selected through the PRISMA guidelines and Braun and Clarke’s [28] six-phase thematic analysis framework. This approach provides a rigorous yet flexible method suitable for reviewing diverse qualitative insights. Braun and Clarke’s [28] six-phase thematic analysis framework was chosen for its proven applicability in synthesizing large bodies of literature in interdisciplinary domains and its capacity to reveal both latent and explicit patterns. The 128 research papers were selected by individual authors for independent coding based on title, journal, author, and abstract. The results from each author were discussed and disagreements resolved through discussion, which allowed the determination of further coding and synthesis criteria, as detailed in Table 2. Repeating the process, each author reviewed the 128 articles, considering titles and abstracts, which significantly reduced the risk of including themes with low or no relevance to the topic or excluding significant ones. The coding yielded codes that described distinct ideas, practices, or phenomena, such as “reverse logistics”, “eco-design”, “AI integration”, or “cross-border regulation”. This process generated more than 400 preliminary codes. Codes were then reviewed for semantic similarity and grouped into higher-order sub-themes, such as “circular supply chain redesign”, “institutional drivers”, or “data-driven innovation”. These sub-themes were iteratively refined through axial coding into six dominant themes, each representing a critical lens of the CE in an IB context.

Table 2.

Final Themes, Sub-Themes, and Sample Codes.

These themes were not arbitrarily derived but were grounded in the empirical and theoretical patterns recurring across the reviewed literature. Each theme captures a significant dimension of the conceptualization, implementation, and evaluation of the CE within IB operations.

The clusters presented in Table 3 highlight the multifaceted nature of the CE, encompassing both operational and strategic elements for sustainable transformation. This study categorized 128 articles using keyword-based text mining, co-occurrence analysis, and qualitative interpretation at the abstract level. The largest category, Circular Supply Chain Strategies, includes 80 studies, reflecting the importance of strong supply chain management (SCM) to the competitive strength of industrial businesses. The Innovation for Circularity cluster contains 33 studies. The Digital Enablers and Industry 4.0 cluster consists of 14 studies examining how smart technologies enable data and analytics within circular systems. This theme reflects the convergence of the CE with Industry 4.0, as highlighted by the growing interest in “smart circular economy” frameworks.

Table 3.

Clusters and their sources in the CE.

The authors combined keyword co-occurrence analysis with manual abstract reviews for an inductive analysis of CE networks. This analysis identified six overlapping clusters that expanded the literature-based structures. Three clusters—Circular Supply Chain Strategies, Innovation for Circularity, and Digital Enablers and Industry 4.0—were identified. The remaining clusters—Integrating Supply Chain Management and Industry 4.0, Collaborative Subjects in the CE, and Evolving Perspectives on the CE—emerged from interdisciplinary literature. Together, these clusters demonstrate how supply chain circularity, innovation, and digital enablement guide academic inquiry while revealing emerging interdisciplinary connections that shape future research.

3. Results

3.1. SCM in the CE

Supply chains are the operational pillars of IB. Moreover, the role of supply chains is crucial in incorporating the CE into IB. Studies underscore that the transition toward circular SCM must extend beyond logistical tasks and be recognized as a strategic necessity for global sustainability [36,37,38]. This transition demands dynamism and flexibility in the supply chain [39], along with stakeholder engagement to integrate the CE [40]. In the context of IB, this change also involves managing environmental risks, diversifying supply sources, and aligning suppliers across different regions to adhere to common circular standards with configurations and coordination that incorporate artificial intelligence (AI) [41,42].

A significant insight from these studies is the emphasis on integrating circular supply chains through a collaborative approach [43]. Technologies like blockchain play a crucial role by enabling closed-loop systems that enhance transparency and traceability in the supply chain [44,45]. Research shows that IB participants adopting circular supply practices often achieve proficiency through strategies such as reverse logistics, closed-loop systems, and product-service frameworks. The sustainability commitment of top executives, driven by AI, is essential for CE practices, leading to cost-efficient and environmentally friendly SCM [46]. A CE helps companies comply with strict international environmental regulations regarding sustainability. This approach builds customer trust by using sustainable materials and taking responsibility for products at the end of their lifecycles [47,48].

In the context of IB, the perception of a network is of utmost importance, particularly within the SCM framework. This field prioritizes resource efficiency and the development of a circular closed-loop system, which necessitates the continuous exchange of information, goods, and CE practices on a global scale [12]. Such a system enables exceptional optimization of production processes by reducing waste [31], minimizing costs, fostering customer loyalty, and enhancing competitive strength. Consequently, SCM is essential for the CE in IB. Furthermore, applying a CE to supply chains in a global business environment requires cooperative and flexible strategies across various regulatory and cultural landscapes. Supply chains function not only as pathways for goods but also as mechanisms through which circularity can be established and expanded on a global scale. These insights highlight that managing circular supply chains is fundamental to the CE in IB. The effectiveness of the CE depends on embedding sustainable practices into procurement, operations, and logistics, all of which require ongoing optimization across international borders.

3.2. Innovative Business Models for the CE

Innovative business models are conceptual drivers that enable the implementation of the CE for sustainability. The related body of research consistently highlights the shift from a linear to a circular value co-creation model. Innovative business models involve a fundamental reevaluation of how companies worldwide generate, deliver, and capture value. These models require a multidimensional approach with commitment from top executives, skilled employees, and robust internal corporate systems [49]. Innovative models prevent stagnation within a CE [50], while value co-creation enhances its applicability [51]. Business models incorporating CE principles frequently adopt strategies such as servitization, remanufacturing, product-as-a-service systems, and closed-loop systems designed for global scalability. These models enable companies to decouple growth from resource extraction, which is increasingly crucial for international sustainability [52,53].

Notably, the literature emphasizes that business model innovation extends beyond corporate-level activities and responds to institutional and societal demands that vary internationally. Businesses operating within diverse regulatory environments must tailor their CE business models to align with local environmental regulations [54]. IB innovation linked with social trust can align CE practices to enhance global competitiveness [55]. Ongoing changes in the business environment demand innovation at every stage. Innovation is key to maintaining competitiveness and fostering growth, particularly for IB.

Additionally, integrating the supply chain in emerging markets requires business model innovation through flexibility and adaptation, leading to environmental sustainability [56]. The dynamics of business model innovation are influenced by numerous internal and external factors contributing to success. The transition from a linear economy to a CE involves internal factors, such as organizational culture and resource management, alongside external market demands and policies [50]. Business model innovation is more challenging for established companies compared to newer entities, such as those in the gig economy, which can be more easily developed and adapted [57]. The Green Alliance CE has proposed an innovative business model for recycling and reusing e-waste, using environmentally friendly production as the foundation for advancing a circular product lifecycle [58].

Many studies emphasize the influence of digitalization, stakeholder involvement, and cross-sector partnerships as a foundation for business models. The literature demonstrates that innovative business models become feasible when companies actively incorporate circularity into their customer value propositions, supply chain structures, and revenue strategies. This may also be a necessity for corporations, as IB participants adopt these models for legitimization [59]. The adoption of the quintuple helix model could be a pathway for the CE in IB [60]. Effective CE ecosystems require strong collaboration between stakeholders and customers [61].

The literature collectively acknowledges that CE business models not only promote environmental sustainability but also create new market opportunities, enhance customer loyalty, and build long-term resilience in global contexts. These models enable companies to transform sustainability from a compliance-focused cost economy to a source-focused CE with competitive advantage and innovation [62,63]. Therefore, developing business models aligned with the CE is crucial for reshaping IB toward a more regenerative economic future.

3.3. Integrating SCM and Industry 4.0 for the CE

The integration of SCM with Industry 4.0 technologies represents a significant paradigm shift in promoting the CE within IB. The literature emphasizes how this integration enables companies to employ circular principles through digitally enhanced e-supply chains that are adaptable, transparent, and optimize resource use [64,65]. These hybrid models support the shift from linear to circular operations and establish the infrastructure essential for adopting strategies at an IB scale by optimizing reverse logistics, enhancing product lifecycle tracking, and automating waste reduction processes. Industry 4.0 is transforming SCM on a global scale by integrating advanced technologies such as the Internet of Things (IoT), AI, and blockchain. These developments provide real-time visibility, predictive analytics, automation, and optimization of supply chain operations and decision-making. Industry 4.0 improves transparency, capability, and collaboration, thus promoting agile and sustainable international supply chains that enhance CE innovation, efficiency, and value creation [66].

For the effective implementation of the CE, IB participants must incorporate Industry 4.0 into SCM. An organization’s ability to adapt, learn, and change over time using its skills, resources, and knowledge, combined with Industry 4.0, supports circular and resilient manufacturing supply chains by enabling real-time monitoring, resource tracking, and addressing CE implementation challenges [65]. The CE is central to this integration, which involves the synchronization of physical supply processes with cyber-physical systems that gather, relay, and act upon real-time data. This combination enables international companies to enhance their global operational capabilities and facilitates closed-loop flow across borders. For example, incorporating blockchain into Industry 4.0-based supply chains improves circularity, trust, and decentralized coordination, supporting real-time, data-driven decisions and promoting strong interorganizational collaboration, thus accelerating sustainable supply chain integration [64]. This is particularly beneficial in IB, where materials and components frequently navigate intricate multinational value networks.

Additionally, research indicates that merging SCM with Industry 4.0 enhances decision-making agility and strategic foresight in CE initiatives. The integration of dynamic capabilities and Industry 4.0 technologies allows firms to build circular and flexible IB supply chains by reallocating resources, adapting to disruptions, and executing sustainable practices [65]. This expertise is essential for addressing regulatory requirements, achieving carbon neutrality, and meeting consumer expectations, which vary significantly across markets.

By integrating SCM with Industry 4.0, the CE extends beyond technical enhancements. This amalgamation represents a strategic transformation that makes a CE feasible on a global scale. It unites production, logistics, and end-of-life stages into a unified digital framework, allowing companies to execute circular strategies with high accuracy and robustness. Therefore, the integration of Industry 4.0 and SCM in IB for the CE requires a comprehensive approach that combines technological innovation, collaboration, and strategic planning.

3.4. Digital Enablers and Industry 4.0 in the CE

Digital technologies and advancements in Industry 4.0 play a crucial role in promoting a CE within the complex domain of IB. Industry 4.0, combined with lean production methods, establishes a robust foundation for implementing CE strategies in manufacturing. Together, they help overcome transition barriers, enhance sustainability, and shape competitive, future-ready business models [67]. Digitalization supports the development of business models for industrial manufacturers [68]. It stimulates the CE not only through adoption but also by enabling firms to develop dynamic capabilities, such as sensing, seizing, and transforming, which are vital for successful industrial circular transitions [69]. The disclosure of Industry 4.0’s transformation in annual reports, especially when coupled with strong ESG performance, positively influences financial performance [70]. CE practices in supply chain design, relationships, and HR enhance firm performance, and big data amplify this impact, particularly in HR-related circular efforts [71]. The IoT supports CE practices in Industry 4.0 by identifying stakeholder expectations for IoT tools and establishing best practices to monitor the environment, thus supporting manufacturing research [72].

Industry 4.0, representing the fourth phase of the Industrial Revolution, is characterized by interconnectivity, automation, machine learning, and real-time data utilization. Although the integration of digitalization and the CE is in its early stages, the innovative contributions of smart technology to businesses, particularly industrial firms, through circularity are noteworthy [69]. Industry 4.0, encompassing resource management, manufacturing, and IB, fosters creativity to enhance productivity. However, reverse logistics remains in its infancy and is intricately linked to digitalization technologies such as cloud connectivity, the Industrial IoT, AI, and machine learning. The evolving collaboration between the CE and Industry 4.0 is advancing toward sustainable solutions [58]. Despite the urgent need for stakeholder collaboration, the requirements and outcomes remain unclear.

The strategic adoption of smart technologies in waste management, emphasizing the 3Rs (recycling, reuse, refurbishing) and reducing the consumption of critical natural resources, generates new opportunities. The synergy between the CE and Industry 4.0, as evidenced by RFID-enabled waste-carrying trucks, sensor-enabled waste bins, and robots used for waste sorting, creates new opportunities in the waste recycling industry [73].

Many studies highlight that digital tools reduce transaction costs and simplify the complexities of international circular loops. Blockchain and RFID technologies improve transparency and traceability in global reverse logistics and closed-loop supply chains, while AI aids demand forecasting and lifecycle assessment, which are crucial for circular planning [74,75]. These technological advancements allow MNEs to monitor, retrieve, and reintegrate materials in a manner that conforms to local regulations and meets consumer expectations across regions [76,77]. Nevertheless, the involvement of various stakeholders in a CE is complex, and the dynamics of beliefs about a CE remain uncertain.

3.5. Collaborative Subjects in the CE

Collaboration is crucial for the effective implementation of CE principles in IB. Research within this cluster collectively highlights that circular transformation extends beyond individual elements, such as SCM, innovation, and digitalization. This suggests that circular loops require efforts beyond individual companies, involving multiple actors, including governments, non-governmental organizations, intermediaries, and institutional ecosystems. A significant synthesis emerges from big data and stakeholder-driven decision-making, which can empower the CE in emerging markets by enabling technologies, enhancing business significance, deriving value, and achieving circular goals [78]. Such collaborative structures are particularly vital in international contexts, where regulatory frameworks, resource availability, and stakeholder expectations vary widely. The successful adoption of a CE often results from interconnected efforts, making collaboration essential. Even in sectors actively engaged in areas such as waste management, renewable energy, emissions reduction, and sustainable CE practices, the clarity of their disclosures is often low, hindering stakeholder understanding and engagement and limiting the full potential of the CE [79,80]. Furthermore, international collaboration promotes the dissemination of CE practices by fostering learning, technology transfer, and knowledge exchange, especially in areas with institutional gaps where strategic alliances could facilitate CE adoption, such as among small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) [81].

Expertise across various platforms is required to facilitate holistic approaches to achieving the objective of a circular loop with multiple stakeholders across borders. An example is the Sustainable Processes and Resources for Innovation and National Growth (SPRING) initiative in Italy [52], where firms within the SPRING cluster are encouraged to enhance their positioning across various domains, exemplifying innovative business models as hallmarks of the CE in the bioeconomy. Collaboration enables the examination of intricate issues from multiple perspectives and the formulation of comprehensive strategies to address them. Such partnerships can include the integration of empirical studies and theoretical applications to achieve CE objectives [65].

These transformations depend heavily on supportive networks encompassing the public, private, and civic sectors. Such arrangements not only lend legitimacy to circular initiatives but also improve access to resources, such as secondary materials and reverse logistics. This fosters adaptive capacities essential for scaling internationally, such as e-waste collection, repair, remanufacturing, and recycling businesses [82]. In this context, the CE in IB surpasses internal policies and innovation, indicating a structural transformation in how international companies engage in circular ecosystems.

The integration of digital business transformation, organizational ambidexterity, and circular business models enhances Industry 4.0, thereby promoting sustainable supply chain performance [66]. This multidimensional collaborative approach advances CE goals in IB. Reverse logistics activities are complex and dynamic, involving various stakeholders and the flow of materials, information, human resources, and financial resources [83,84]. Although markets are more effective when waste materials possess economic value, they are often insufficient to drive innovation when environmental value surpasses economic incentives. In such cases, public sector support through regulations and demand shaping is essential to facilitate the CE transition [85].

From a strategic perspective, these findings highlight the importance of the CE in helping companies operating globally to develop institutional capabilities and form alliances with stakeholders to facilitate the transition. Such collaborative efforts can include international joint ventures aimed at advancing recycling technologies or multi-stakeholder platforms that work toward regulatory alignment of circular processes. This study indicates that emerging markets and developing economies gain substantial advantages from international CE partnerships, which can offset the lack of domestic policy support and infrastructure. However, Manioudis and Meramveliotakis [86] suggest that scholars in international development methodically contrast current development studies with classical frameworks, offering theoretical depth and clarity to pave the way for future frameworks. The path to achieving CE sustainability in IB often requires a complete demolition and redefinition of the system [87].

3.6. Evolving Perspectives on the CE

CE studies in the context of IB emphasize the evolution of global sustainability practices. IB participants have implemented frameworks associated with global sustainability. However, scholars have noted that significant knowledge gaps still exist [11]. Moreover, internal factors such as leadership commitment, specialized skills, and cultural awareness are significant in adopting a CE in IB. Nonetheless, considerable gaps remain in implementing these internal dynamic functions in large, established, and internationally operating firms [47].

AI is essential for steering sustainable practices in the CE by optimizing resource use and improving decision-making in CE initiatives. AI capabilities enhance green innovation, which improves sustainable performance and CE outcomes, primarily when supported by big data analytics and knowledge management systems. Integrating AI with data and knowledge systems significantly promotes sustainability [88]. Recently, IB participants have become increasingly interested in capturing emerging markets with innovative products that require less investment, aiming to provide at least cost to the end user. AI plays a greater role in this by generating frugal innovations aligned with the CE to reduce resource use and maximize competitive strength [42].

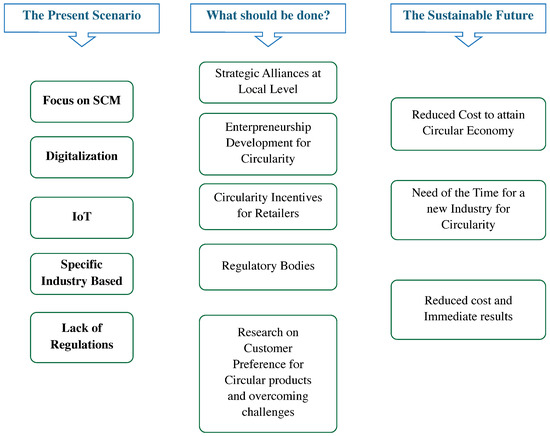

The CE in IB faces challenges related to infrastructure and inadequate regulations that obstruct circularity, requiring a systemic, collaborative approach. Shared responsibilities, cross-border regulatory coherence, and integrated stakeholder efforts are ways to advance the CE globally [89]. Achieving sustainability is not a short-term goal. Sustainability is influenced by innovation, investor involvement, and sustained engagement with the sharing economy, which together provide important macro-level insights into IB and policies. Industrial policies and regulations focused on sustainability are key drivers of environmental transformation. For global businesses, this stresses a shift from a firm-level CE to an ecosystem perspective on the CE [90]. The circularity of IB must withstand global disruptions such as the pandemic. A resilient CE arises from adaptive capabilities, especially digitalization and integration, which are fundamental to supply chain survival during global disruptions [91]. In the context of IB, the concept of a CE is shifting focus from operational efficiency to strategic transformation. Corporations are becoming increasingly involved in comprehensive change, adopting legitimacy and meeting stakeholder expectations. By incorporating digitalization, innovation, and policy adaptability, IB participants have restructured value creation across borders (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Strategic Roadmap for the Evolution of the CE in IB. Source: Authors.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to synthesize and critically advance both established and emerging scholarship on the circular economy (CE) within the context of international business (IB), guided by four primary objectives. First, it consolidated prevailing trends across key thematic domains, offering a structured analysis of how CE has been conceptualized and operationalized on a global scale. Second, through the theoretical lens of the ABV, it examined how managerial attention and organizational priorities shape the adoption and diffusion of CE strategies in international contexts. Third, it applied the MLP to explain the evolutionary pathways and institutional dynamics that influence CE integration across firms, industries, and national boundaries. Finally, this discussion presents research gaps and proposes a future research agenda that integrates insights from the ABV and MLP, offering a coherent framework for advancing theory and practice in the CE within IB. This study draws on the ABV [7], which posits that organizational decisions are shaped by the issues leaders notice and how they interpret them. In the context of IB, executive attention tends to focus on evident and high-reward strategies [92,93,94], such as digital transformation or compliance with global environmental standards, often at the expense of local-level engagement, leadership development, or consumer-centric innovation. This explains why themes such as local entrepreneurship, AI applications, and consumer behavior remain under-researched or under-prioritized despite their recognized importance [36,55].

Our findings span across the micro, meso, and macro levels of analysis and implementation. At the micro level, the literature highlights entrepreneurial initiatives, retailer engagement, and the adoption of AI and digital tools that drive transformations at the local level toward circularity. The meso level highlights strategic collaborations, cross-sectoral partnerships, and supply chain configurations that empower the implementation of circular models. At the macro level, the studies examined underscore the influence of regulatory frameworks, institutional pressures, and evolving consumer preferences in shaping CE transitions. Additionally, the systematic review incorporated all three levels.

Further, the identified role of digital technologies such as the IoT and blockchain confirms earlier research emphasizing their enabling functions in CE adoption [61,95]. However, our findings extend this body of work by showing that AI, a more cognitive and predictive tool, remains underutilized. From the perspective of the ABV, this suggests that managerial attention focuses on “measurable” technologies like blockchain, which support reporting and traceability, rather than on AI, which requires long-term vision and abstract strategic thinking. The role of supply chains as CE enablers aligns with prior work [39], but our analysis challenges the dominant narrative by revealing a lack of attention to SME integration and reverse logistics customization across cultural contexts. The ABV explains this as a top management bias toward centralized, high-visibility logistics systems, overlooking the decentralized, adaptive supply innovations of local partners [38,92].

Our study reveals that though CE is widely accepted and attention to CE in IB, the literature remains heavily focused on supply chain optimization and digital technologies. The aim and strategies are to achieve operational efficiency, while broader sustainability outcomes—CE as climate action, consumer engagement in sustainability, and entrepreneurial innovation—receive limited attention. Our study offers a critical perspective that highlights the gaps at the micro, meso, and macro levels. The study emphasizes the need for more integrated strategies that align managerial attention with multi-level sustainability objectives. By situating CE within this larger sustainability context, our study underscores both the achievements and the significant areas still underexplored in IB research.

Our findings confirm the transformative role of circular business models in decoupling value from resource use [52]. However, we challenge the prevailing assumption of a “universal model” by showing that business model innovation needs to adapt to local cultural and regulatory environments. The ABV clarifies that strategic attention in global firms often remains fixed on macro-level compliance and digital efficiency, neglecting context-specific adaptation, which constrains local legitimacy and adoption. Leadership commitment, while noted in earlier studies [58], remains peripheral in the CE–IB literature. For instance, Chabowski, Han, and Sar [93] research on sustainable international business model innovations for the circular economy and provides an integrative framework for CE transitions with IB. The review provides valuable insight on policy, partnership and innovation. However, the research has focused on supply chain and digitalization. Our findings stresses the overly attention on value chains and digitalization with limited executive-level attention and integration of CE principles in IB strategies. Our findings extend this discourse by identifying a lack of structured executive attention to CE transitions, particularly when integrating environmental key performance indicators into core strategy [94]. The ABV not only explains this gap but also suggests solutions by advocating for new attentional structures, such as CE–dedicated C-suite roles or performance dashboards, which elevate sustainability to a strategic focus.

Our data show that retailers and consumers are underrepresented actors in CE literature. This challenges existing IB sustainability frameworks, which are overly firm-centric. The ABV reveals that corporate attention systems filter out consumer engagement unless it is linked to immediate return on investment or reputational risks, indicating the need to reconfigure attentional processes to include downstream actors more meaningfully. The failure to align micro-level innovations (e.g., entrepreneurial solutions), meso-level firm strategies, and macro-level policy frameworks is a persistent fragmentation in CE–IB research. Our analysis confirms Kansheba et al. [11] in identifying this disjunction. The ABV explains this as a cognitive misalignment of attentional domains: different stakeholders prioritize different signals, leading to breakdowns in coordination and learning. Therefore, a more integrated attention architecture is required to align these levels.

By applying the ABV to CE implementation in IB, this study challenges the traditional operational framing of the CE and recasts it as a function of executive attention [92,93,94] and strategic cognition. This highlights that many observed gaps—AI neglect, weak leadership involvement, and limited local engagement—are not merely resource constraints but also attentional blind spots. Thus, the ABV provides a theoretical tool for understanding why certain CE practices succeed or stall across international contexts.

In sum, our findings reinforce but also extend prior work on CE in IB. For example, Chabowski et al. [93] underscored the role of sustainable business model innovations in international contexts, yet their integrative framework remained heavily focused on supply chains and digitalization; our analysis confirms this emphasis but reveals that executive attention to CE integration remains peripheral and insufficiently structured. Similarly, Castilla-Polo and Sanchez-Hernandez [55] highlighted the CE awareness of agri-food cooperatives. Still, our results show that such awareness often fails to translate into consumer engagement or SME integration within global value chains. Bag and Rahman [75] emphasized how leadership attention to analytics and political factors can strengthen CE performance. However, our findings caution that this attention is still disproportionately directed toward traceability and efficiency rather than long-term innovation. Finally, Neri et al. [68] illustrated the potential of digital-enabled dynamic capabilities for advancing CE, while our study demonstrates that managerial attention continues to privilege “measurable” technologies like blockchain over predictive tools such as AI [68]. Together, these insights show that earlier research has recognized the importance of CE in IB, but our analysis highlights additional blind spots—particularly weak executive attention, neglect of AI, and limited consumer integration—that must be addressed through better alignment of micro, meso, and macro strategies.

5. Theoretical and Practical Implications

The study makes several significant contributions to literature and theory by integrating the Attention-Based View and Multi-Level Perspective for the advancement of CE implementation in International Business. Prior research has focused on managerial attention and system-level transitions in isolation. This study depicts the framework that demonstrates that CE adoption requires both focused managerial attention and alignment across micro, meso, and macro levels. Putting together the overlooked factors like entrepreneurship, retailer engagement, AI integration, and consumer preferences through the integration of the ABV-MLP lens, the study highlights that the allocation of executive attention connects firm-level decisions with broader CE transformations. The categorization of systematically reviewed 128 articles, seizing the recent trends into six thematic clusters, informs that theoretical development is fragmented for CE application in the context of International Business. In addition, the study identifies through the 6 themes and framework where and how theoretical development is uneven. For instance, in the evolving perspectives theme, consumer behavior and preferences are underexplored. In the digital enablers and Industry 4.0 theme, entrepreneurship and retailer dynamics are scarcely considered, and in collaborative subjects, cross-sector alliances are documented but still disconnected from AI-driven innovation. This mapping demonstrates that theoretical advancement in CE and IB requires bridging different routes through which absolute implementation and application of CE can happen across International Business.

Furthermore, the findings of the study provide valuable insights for managers, policymakers, and practitioners in the context of CE and International Business. First, top management needs to realize that managerial attention is a critical driver of sustainability, which extends to CE implementation. In the absence of a comprehensive strategy to implement sustainability at every level, CE implementation in International Business remains peripheral. Second, the study informs the managers that firms involved in International Business should expand their focus beyond supply chain efficiency and digital technologies. This involves including consumer preferences, entrepreneurial initiatives, and retailer engagement, which are currently underexplored in practice. For policymakers, the findings of the study guide on the importance of cross-sector collaborations and strategic alliances at the meso level. AI and digital capacity are not just technological decisions for International Business but also a matter of directing executive attention to integrate these tools into sustainable business models. Resonating with our findings, Munonye [93] states that integrating CE principles into business strategies needs a strong policy-driven orientation. This aligns with our observation that institutional and regulatory frameworks can play a catalytic role in expanding IB’s engagement with CE beyond supply chain optimization. Finally, global firms must develop digital and organizational capabilities to embed the CE into core operations.

6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Despite several contributions, the study also has many limitations. First, the study is based on a systematic literature review focused on the time frame of 2020–2025, which could have excluded earlier influential studies. Second, the review analyzes 128 peer-reviewed articles, which ensures depth but may limit the generalizability of findings across all sectors of international business. Third, though the six categories lead to a structured understanding of CE in International Business, the study could fall under a degree of subjectivity. Finally, the conceptual framework integrating ABV and MLP is theoretical and has not been empirically validated; therefore, its practical application requires further testing and validation in real-world contexts.

Accordingly, the study offers several avenues for future research in CE implementation in International Business. While prior studies have predominantly focused on supply chain management and Industry 4.0 technologies, this review identifies underexplored areas across micro, meso, and macro levels. At the micro level, future research should further investigate entrepreneurship, retailer engagement, and the adoption of artificial intelligence within firms, as these factors play critical roles in driving circular innovation and operationalizing circular economy strategies. At the meso level, further research should explore strategic alliances and cross-sector collaborations as mechanisms to facilitate the diffusion of circular practices across industries and supply chains. At the macro level, broader systemic factors—such as consumer preferences, market demand, and regulatory environments—remain underexplored and warrant empirical investigation. Additionally, technological enablers, particularly artificial intelligence, play a pivotal role in elucidating the structure of circular economy adoption within international supply networks.

Empirical studies exploring how managerial attention interacts with institutional structures, organizational capabilities, and digital technologies will strengthen the practical applicability of the ABV–MLP conceptual framework proposed in this study. Figure 3. Strategic Roadmap for the Evolution of the CE in International Business is conceptually derived from the review and the ABV–MLP framework, illustrating priority areas for future research and practice. The diagram highlights five key areas: Strategic alliances at the local level to enhance collaboration and resource sharing, Entrepreneurship development focused on circular innovation, Retailer engagement and circularity incentives, Regulatory and policy alignment across borders to reduce institutional voids, and investigation of consumer preferences to inform demand-driven CE strategies. Finally, future research should adopt multi-method approaches, including longitudinal, cross-country, and mixed-method designs.

7. Conclusions

This study systematically synthesizes the emerging literature on the CE within IB, identifies dominant themes, and interprets these findings through the ABV and the MLP. Thematic analysis revealed six major clusters: (1) SCM in the CE; (2) innovative business models for the CE; (3) integration of supply chains and Industry 4.0; (4) digital enablers in the CE; (5) evolving perspectives on the CE; (6) collaborative approaches to the CE. These themes collectively highlight how technological enablers, institutional shifts, stakeholder pressures, and strategic decision-making shape CE strategies across global contexts. The findings extend prior research by showing that firms increasingly adopt CE practices not only as a sustainability imperative but also as a pathway for operational efficiency, innovation, and competitive advantage. Industry 4.0 technologies—especially the IoT, AI, and blockchain—have emerged as key enablers that attract organizational attention and facilitate CE adoption. At the same time, significant barriers remain, including regulatory fragmentation, implementation complexity, and a lack of internal capabilities. From the ABV perspective, firms prioritize CE practices when they align with top management’s attention, stakeholder salience, and perceived economic value. The MLP situates these transitions within landscape pressures, regime-level barriers, and emerging niche innovations, particularly in multinational environments. This study offers several practical implications. Second, policymakers should promote cross-border alignment of CE regulations to reduce institutional voids. Third, stakeholders, including retailers and end-users, play critical roles in shaping circular practices, requiring further strategic collaboration across the value chain. However, this study has limitations. The review was restricted to a defined time frame and focused only on peer-reviewed literature, potentially overlooking gray literature and emerging policy developments. Methodologically, while thematic analysis was used, the absence of quantitative meta-analysis or triangulation with primary data may limit the generalizability of findings. Additionally, the ABV and MLP were applied conceptually rather than empirically tested. Future research should address these limitations by adopting multi-method approaches, exploring CE strategies in emerging markets, and empirically examining how managerial attention and institutional structures affect CE outcomes in IB. Beyond SCM, research should explore underexamined areas such as strategic alliances for the CE, entrepreneurship in circular innovation, and the influence of customer preferences on cradle-to-cradle product strategies. Investigating how AI, blockchain, and digital-twins specifically reshape the CE across international supply networks remains a critical frontier. In summary, this study advances understanding of the intersection between the CE and IB by integrating theoretical perspectives, providing a structured synthesis of key themes, and outlining future research directions. It offers a foundation for scholars, practitioners, and policymakers seeking to navigate and accelerate sustainability transitions in IB.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su17219532/s1, Table S1: PRISMA 2020 Checklist. Reference [96] is cited in Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.P. and H.B.; methodology, M.P.; formal analysis, M.P.; data curation, M.P.; writing—original draft preparation, M.P., H.B., T.B.H. and W.B.A.-Y.; writing—review and editing, M.P., H.B., T.B.H. and W.B.A.-Y.; supervision, T.B.H.; project administration, T.B.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Qatar University Collaborative Grant. Project title: Scaling Qatar’s Entrepreneurial Ecosystem in the Emerging Sectors: Policy Insights on Needs to Empower Innovation, Entrepreneurship, and Knowledge Economy’, Project no. QUCG-CAS-24/25–396.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing does not apply to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CE | Circular economy |

| IB | International business |

| CSR | Corporate social responsibility |

| ABV | Attention-Based View |

| MLP | Multi-Level Perspective |

| MNE | Multinational enterprise |

| SSCI | Social Science Citation Index |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| ABDC | Australian Business Deans Council |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| SCM | Supply chain management |

| SPRING | Sustainable Processes and Resources for Innovation and National Growth |

| SME | Small and medium-sized enterprise |

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Evolution of Research on the Circular Economy and Sustainability in International Business (2020–2025). Source: Authors’ elaboration based on Web of Science data.

References

- Dimitropoulos, P.; Koronios, K.; Sakka, G. International business sustainability and global value chains: Synthesis, framework, and research agenda. J. Int. Manag. 2023, 29, 101054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisellini, P.; Cialani, C.; Ulgiati, S. A review on circular economy: The expected transition to a balanced interplay of environmental and economic systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 114, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arruda, E.H.; Melatto, R.A.P.B.; Levy, W.; de Melo Conti, D. Circular economy: A brief literature review (2015–2020). Sustain. Oper. Comput. 2021, 2, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merli, R.; Preziosi, M.; Acampora, A. How do scholars approach the circular economy? A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 178, 703–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, E. Circular Economy—A Way Forward to Sustainable Development: Identifying Conceptual Overlaps and Contingency Factors at the Microlevel. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 30, 771–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Pieroni, M.P.P.; Pigosso, D.C.A.; Soufani, K. Circular Business Models: A Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 277, 123741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocasio, W. Towards an attention-based view of the firm. Strat. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Lamata, M.; Latorre-Martínez, M.P. The Circular Economy and Sustainability: A Systematic Literature Review. Cuad. Gestión 2022, 22, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, M.; Alfredsson, E.; Cohen, M.; Lorek, S.; Schroeder, P. Transforming Systems of Consumption and Production for Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals: Moving beyond Efficiency. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 1533–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonioli, D.; Ghisetti, C.; Mazzanti, M.; Nicolli, F. Sustainable production: The economic returns of circular economy practices. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2022, 31, 2603–2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansheba, J.M.; Fubah, C.N.; Acikdilli, G. Circular economy practices in international business: What do we know and where are we heading? Bus. Strat. Environ. 2025, 34, 296–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Towards the Circular Economy Volume 1: An Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Cowes, UK, 2013; Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/towards-the-circular-economy-vol-1-an-economic-and-business-rationale-for-an (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Murray, A.; Skene, K.; Haynes, K. The Circular Economy: An Interdisciplinary Exploration of the Concept and Application in a Global Context. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamba, H.K.; Kumar, N.S.; Dhir, S. Circular Economy and Sustainable Development: A Review and Research Agenda. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2024, 73, 497–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamunda, J. The COVID-19 pandemic as a driving force for transformational change in organisations. J. Contemp. Manag. 2022, 19, 198–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Xu, Z.; Škare, M.; Wang, X. Aftermath of COVID-19 technological and socioeconomic changes: A meta-analytic review. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2024, 202, 123322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, S.A.; Indhu, B.; Jagannathan, P. Impact of COVID-19 on supply chain management in construction industry in Kashmir. Asian J. Civ. Eng. 2023, 24, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusch, R.F.; Vargo, S.L.; Wessels, G. Toward a Conceptual Foundation for Service Science: Contributions from Service-Dominant Logic. IBM Syst. J. 2008, 47, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocasio, W.; Joseph, J. The Attention-Based View of Great Strategies. Strategy Sci. 2018, 3, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P.; Smith, W.K.; Vaara, E. New ways of seeing through qualitative research. Acad. Manag. J. 2018, 61, 1189–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roszkowska-Menkes, M.; Aluchna, M.; Kamiński, B. True Transparency or Mere Decoupling? The Study of Selective Disclosure in Sustainability Reporting. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2024, 98, 102700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W. Technological Transitions as Evolutionary Reconfiguration Processes: A Multi-Level Perspective and a Case-Study. Res. Policy 2002, 31, 1257–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W.; Schot, J. Typology of Sociotechnical Transition Pathways. Res. Policy 2007, 36, 399–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, J.; Geels, F.W.; Kern, F.; Markard, J.; Onsongo, E.; Wieczorek, A.; Alkemade, F.; Avelino, F.; Bergek, A.; Boons, F.; et al. An Agenda for Sustainability Transitions Research: State of the Art and Future Directions. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2019, 31, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. SSRN Electron. J. 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, D.F.B.; Padilha, M.A.S.; Cecatti, J.G. Approaching Literature Review for Academic Purposes: The Literature Review Checklist. Clinics 2019, 74, e1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, R.M.; Andrews, R. Local Government Management and Performance: A Review of Evidence. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2015, 25, 101–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; Short, S.W.; Rana, P.; Evans, S. A Literature and Practice Review to Develop Sustainable Business Model Archetypes. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montag, L. Circular economy and supply chains: Definitions, conceptualizations, and research agenda of the circular supply chain framework. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2023, 3, 35–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Savaget, P.; Bocken, N.M.P.; Hultink, E.J. The circular economy: A new sustainability paradigm? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotondo, B.; Bakker, C.; Balkenende, R.; Arquilla, V. Integrating Circular Economy Principles in the New Product Development Process: A Systematic Literature Review and Classification of Available Circular Design Tools. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jesus, A.; Mendonça, S. Lost in transition? Drivers and barriers in the eco-innovation road to the circular economy. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 145, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmykova, Y.; Sadagopan, M.; Rosado, L. Circular Economy—From Review of Theories and Practices to Development of Implementation Tools. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 135, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haupt, M.; Vadenbo, C.; Hellweg, S. Do We Have the Right Performance Indicators for the Circular Economy?: Insight into the Swiss Waste Management System. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, 615–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vass, T.; Nand, A.A.; Bhattacharya, A.; Prajogo, D.; Croy, G.; Sohal, A.; Rotaru, K. Transitioning to a Circular Economy: Lessons from the Wood Industry. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2023, 34, 582–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modgil, S.; Gupta, S.; Zhang, B.; Bag, S. Blockchain-enabled supply chain finance strategies for a circular economy revolution. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2024, 33, 7006–7020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyabeng-Mensah, Y.; Afum, E.; Baah, C.; Essel, D. Exploring the Role of External Pressure, Environmental Sustainability Commitment, Engagement, Alliance and Circular Supply Chain Capability in Circular Economy Performance. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2022, 52, 431–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bag, S.; Rahman, M.S. The Role of Capabilities in Shaping Sustainable Supply Chain Flexibility and Enhancing Circular Economy-Target Performance: An Empirical Study. Supply Chain. Manag. Int. J. 2023, 28, 162–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fobbe, L.; Hilletofth, P. Moving toward a circular economy in manufacturing organizations: The role of circular stakeholder engagement practices. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2023, 34, 674–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciccullo, F.; Pero, M.; Patrucco, A.S. Designing Circular Supply Chains in Start-up Companies: Evidence from Italian Fashion and Construction Start-Ups. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2023, 34, 553–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AL-khatib, A.W.; Ramayah, T. Artificial Intelligence-based Dynamic Capabilities and Circular Supply Chain: Analyzing the Potential Indirect Effect of Frugal Innovation in Retailing Firms. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2025, 34, 830–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, L.; Seuring, S.; Genovese, A.; Sarkis, J.; Sohal, A. Theorising Circular Economy and Sustainable Operations and Supply Chain Management: A Sustainability-Dominant Logic. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2023, 43, 581–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Giovanni, P. Leveraging the Circular Economy with a Closed-Loop Supply Chain and a Reverse Omnichannel Using Blockchain Technology and Incentives. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2022, 42, 959–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komulainen, R.; Nätti, S. Barriers to Blockchain Adoption: Empirical Observations from Securities Services Value Network. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 159, 113714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bag, S.; Dhamija, P.; Bryde, D.J.; Singh, R.K. Effect of Eco-Innovation on Green Supply Chain Management, Circular Economy Capability, and Performance of Small and Medium Enterprises. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 141, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Confente, I.; Russo, I.; Peinkofer, S.; Frankel, R. The Challenge of Remanufactured Products: The Role of Returns Policy and Channel Structure to Reduce Consumers’ Perceived Risk. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2021, 51, 350–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhetri, P.; Nikkhah, M.J.; Soleimani, H.; Shahparvari, S.; Shamlou, A. Closed Supply Network Modelling for End-of-Life Ship Remanufacturing. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2022, 33, 431–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Kolpinski, C.; Yazan, D.M.; Fraccascia, L. The Impact of Internal Company Dynamics on Sustainable Circular Business Development: Insights from Circular Startups. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2023, 32, 1931–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchek, N.; Fernandes, C.I.; Kraus, S.; Filser, M.; Sjögrén, H. Innovation and the Circular Economy: A Systematic Literature Review. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2021, 30, 3686–3702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerke, A.; Fehrer, J.; Benson-Rea, M.; McCullough, B.P. A typology of circular sport business models: Enabling sustainable value co-creation in the sport industry. J. Sport Manag. 2024, 38, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfano, M.R.; Cantabene, C.; Lepore, A.; Palermo, S. The Green to Circular Bioeconomy Transition: Innovation and Resilience among Italian Enterprises. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2023, 32, 6094–6105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Nguyen, D.K.; Tian, X.-L. Assessing the Impact of the Sharing Economy and Technological Innovation on Sustainable Development: An Empirical Investigation of the United Kingdom. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2024, 209, 123743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donis, S.; Gómez, J.; Salazar, I. Economic Complexity, Property Rights and the Judicial System as Drivers of Eco-Innovations: An Analysis of OECD Countries. Technovation 2023, 128, 102868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castilla-Polo, F.; Sánchez-Hernández, M.I. International Orientation: An Antecedent-Consequence Model in Spanish Agri-Food Cooperatives Which Are Aware of the Circular Economy. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 152, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Sezersan, I.; Garza-Reyes, J.A.; Gonzalez, E.D.R.S.; AL-Shboul, M.A. Circular Economy in the Manufacturing Sector: Benefits, Opportunities and Barriers. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 1067–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Piscicelli, L.; Bour, R.; Kostense-Smit, E.; Muller, J.; Huibrechtse-Truijens, A.; Hekkert, M. Barriers to the Circular Economy: Evidence From the European Union (EU). Ecol. Econ. 2018, 150, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaro, M.; Secinaro, S.; Dal Mas, F.; Brescia, V.; Calandra, D. Industry 4.0 and Circular Economy: An Exploratory Analysis of Academic and Practitioners’ Perspectives. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2021, 30, 1213–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiVito, L.; Leitheiser, E.; Piller, C. Circular Moonshot: Understanding Shifts in Organizational Field Logics and Business Model Innovation. Organ. Environ. 2023, 36, 349–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán-Romero, G.; López, A.M.; Beliaeva, T.; Ferasso, M.; Garonne, C.; Jones, P. Bridging the Gap Between Circular Economy and Climate Change Mitigation Policies through Eco-Innovations and Quintuple Helix Model. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 160, 120246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabas, A.M.; Rehman, M.A.; Khitous, F.; Urbinati, A. Stakeholder and Customer Engagement in Circular Economy Ecosystems: A Systematic Literature Review and Research Agenda. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2025, 34, 402–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajewska, A.; Siewczyńska, M. Circular Economy in the Construction Sector in Materials, Processes, and Case Studies: Research Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, S.C.; Neiva, C.R.; Dias, J.C. Action Research on Circular Economy Strategies in Fashion Retail. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2025, 53, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayikci, Y.; Gozacan-Chase, N.; Rejeb, A.; Mathiyazhagan, K. Critical Success Factors for Implementing Blockchain-Based Circular Supply Chain. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2022, 31, 3595–3615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhadi, A.; Kamble, S.; Gunasekaran, A.; Mani, V. Analyzing the Mediating Role of Organizational Ambidexterity and Digital Business Transformation on Industry 4.0 Capabilities and Sustainable Supply Chain Performance. Supply Chain. Manag. Int. J. 2022, 27, 696–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciliberto, C.; Szopik-Depczyńska, K.; Tarczyńska-Łuniewska, M.; Ruggieri, A.; Ioppolo, G. Enabling the Circular Economy Transition: A Sustainable Lean Manufacturing Recipe for Industry 4.0. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2021, 30, 3255–3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oghazi, P.; Mostaghel, R.; Hultman, M. International Industrial Manufacturers: Mastering the Era of Digital Innovation and Circular Economy. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2024, 201, 123160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri, A.; Negri, M.; Cagno, E.; Kumar, V.; Garza-Reyes, J.A. What Digital-enabled Dynamic Capabilities Support the Circular Economy? A Multiple Case Study Approach. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2023, 32, 5083–5101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkaraan, F.; Albitar, K.; Hussainey, K.; Venkatesh, V. Corporate Transformation Toward Industry 4.0 and Financial Performance: The Influence of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG). Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 175, 121423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Giudice, M.; Chierici, R.; Mazzucchelli, A.; Fiano, F. Supply Chain Management in the Era of Circular Economy: The Moderating Effect of Big Data. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2021, 32, 337–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, U.; Sroufe, R.; Shahbaz, M. Industry 4.0 and the circular economy: A literature review and recommendations for future research. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2021, 30, 2038–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost & Sullivan. Digital Technologies Create Disruption for the Future of Waste Recycling. PR Newswire, 30 July 2018. Available online: https://www.newswire.ca/news-releases/frost--sullivan-digital-technologies-create-disruption-for-the-future-of-waste-recycling-689514661.html (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Belhadi, A.; Kamble, S.; Benkhati, I.; Gupta, S.; Mangla, S.K. Does Strategic Management of Digital Technologies Influence Electronic Word-of-Mouth (EWOM) and Customer Loyalty? Empirical Insights from B2B Platform Economy. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 156, 113548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez, R.; Malik, M.; Ghaderi, H.; Yu, W. Environmental Collaboration with Suppliers and Cost Performance: Exploring the Contingency Role of Digital Orientation from a Circular Economy Perspective. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2023, 43, 651–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bag, S.; Rahman, M.S. Navigating Circular Economy: Unleashing the Potential of Political and Supply Chain Analytics Skills among Top Supply Chain Executives for Environmental Orientation, Regenerative Supply Chain Practices, and Supply Chain Viability. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2024, 33, 504–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrilo, S.; Dahms, S.; Tsai, F.-S. Synergy Between Multidimensional Intellectual Capital and Digital Knowledge Management: Uncovering Innovation Performance Complexities. J. Innov. Knowl. 2024, 9, 100568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modgil, S.; Gupta, S.; Sivarajah, U.; Bhushan, B. Big Data-Enabled Large-Scale Group Decision Making for Circular Economy: An Emerging Market Context. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 166, 120607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskin, H.; Esen, E. Themes and Readability of Integrated Reports of Banks from a Circular Economy Perspective. Int. J. Bank. Mark. 2025, 43, 321–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opferkuch, K.; Caeiro, S.; Salomone, R.; Ramos, T.B. Circular Economy in Corporate Sustainability Reporting: A Review of Organisational Approaches. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2021, 30, 4015–4036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, V.; Nandakumar, M.K.; Sahasranamam, S.; Bamel, U.; Malik, A.; Temouri, Y. An Exploratory Study into Emerging Market SMEs’ Involvement in the Circular Economy: Evidence from India’s Indigenous Ayurveda Industry. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 142, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derks, M.; Bidmon, C.; Ciulli, F. Circular E-waste Ecosystems in Necessity-driven Contexts: The Impact of Formal Institutional Voids. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2024, 33, 3733–3747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazancoglu, Y.; Ekinci, E.; Mangla, S.K.; Sezer, M.D.; Kayikci, Y. Performance Evaluation of Reverse Logistics in Food Supply Chains in a Circular Economy Using System Dynamics. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2021, 30, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]