Sustainable Development and Environmental Harmony: An Investigation of the Elements Affecting Carbon Emissions Risk

Abstract

1. Introduction

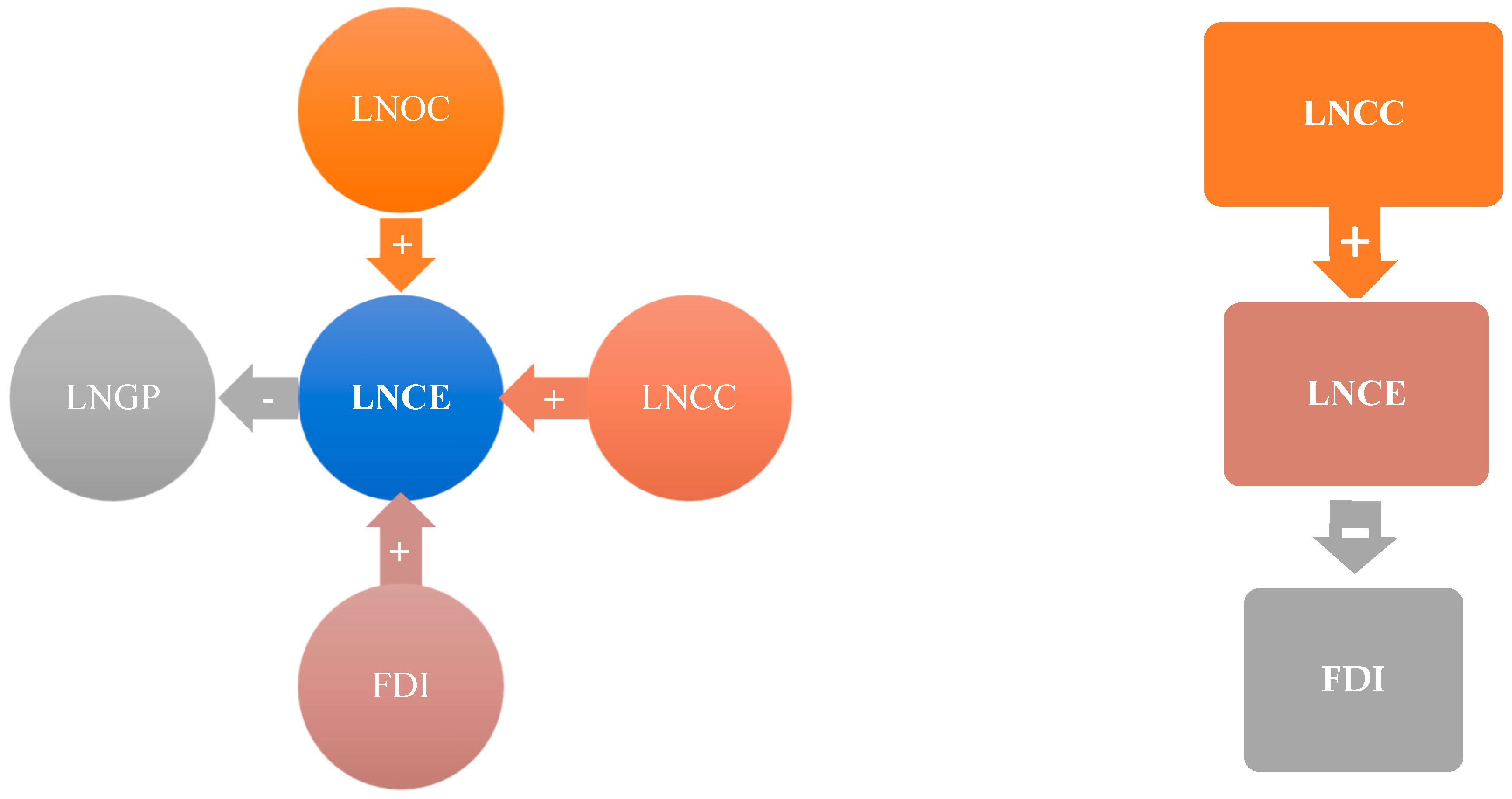

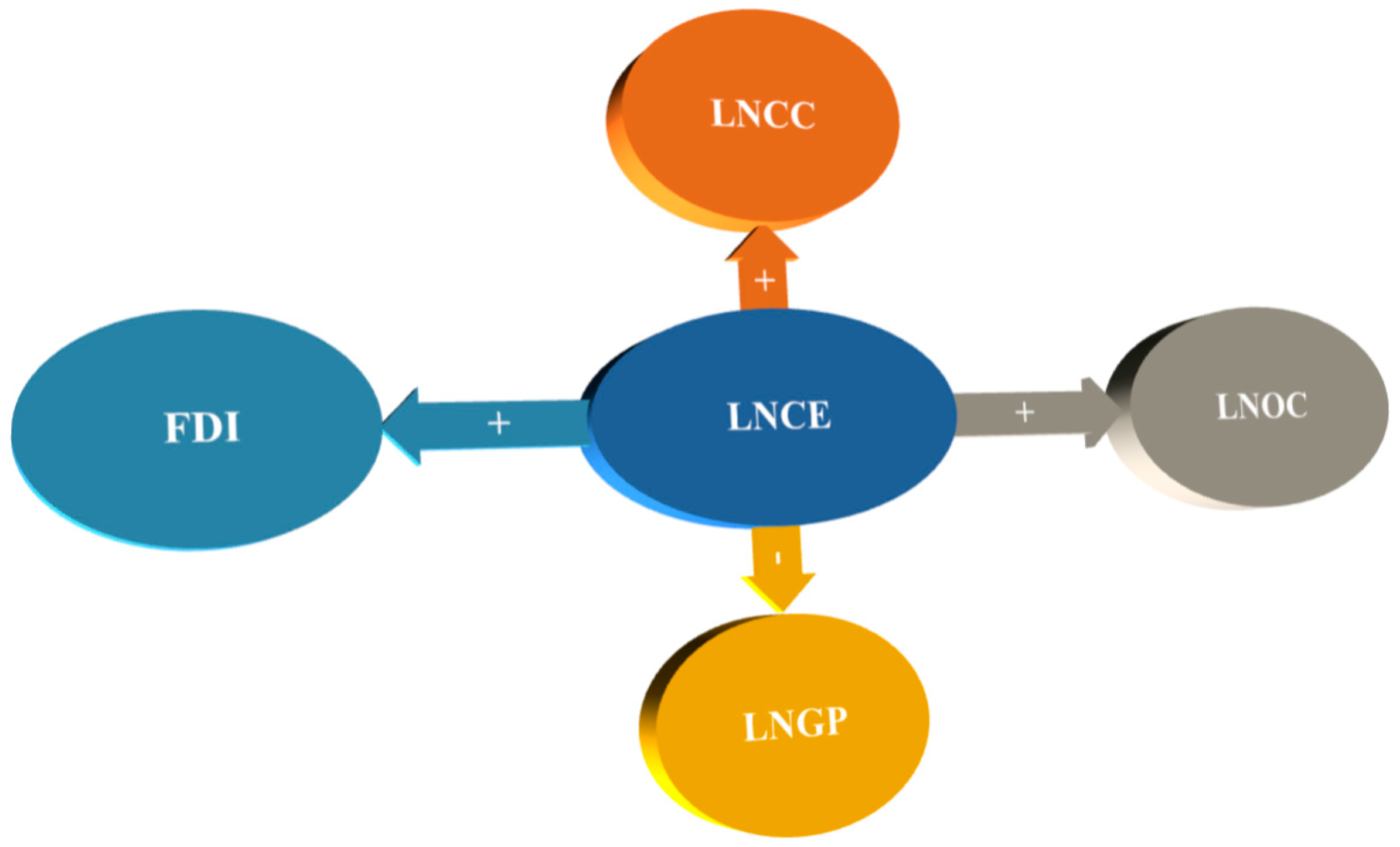

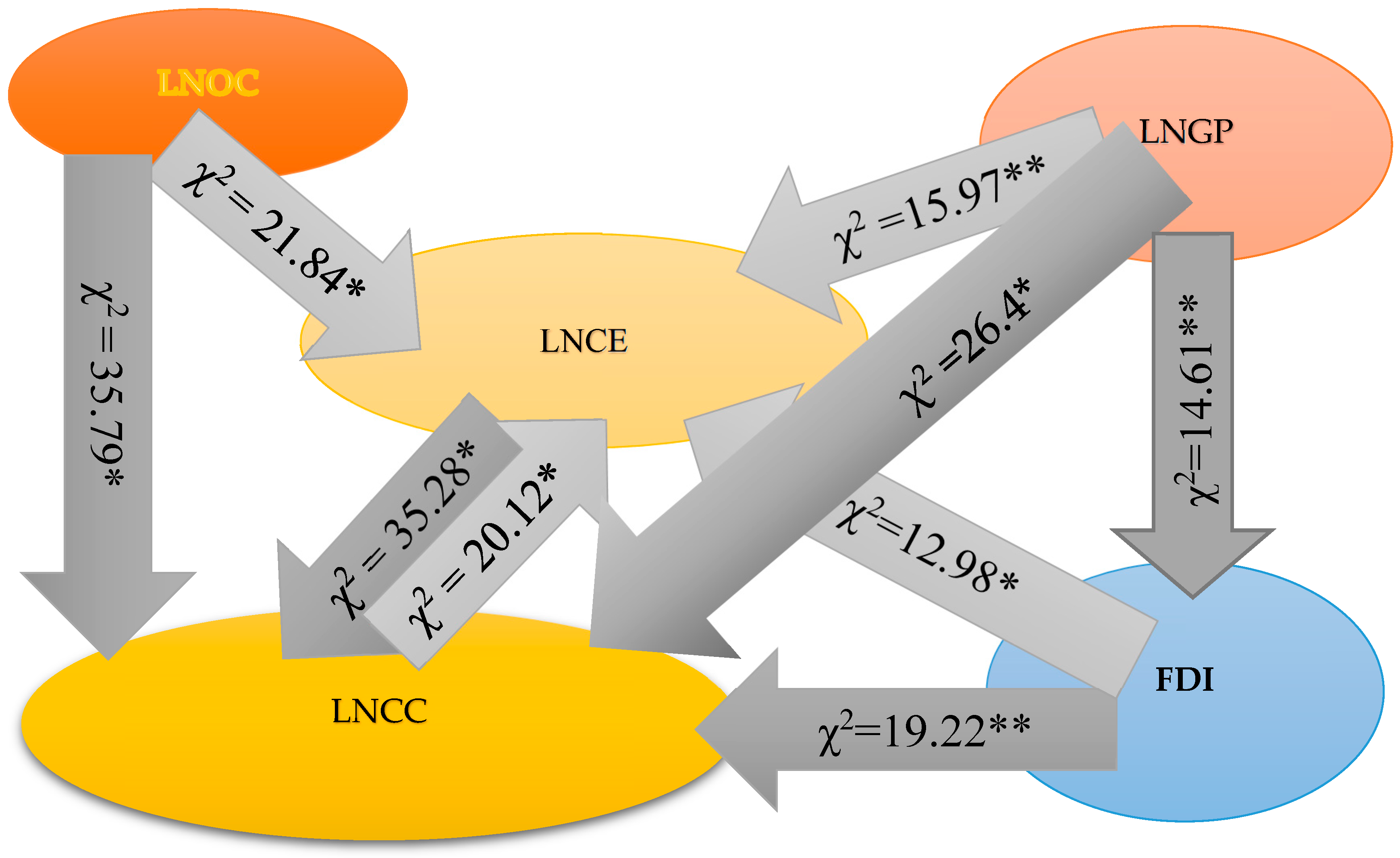

- H1: Fossil fuel consumption (coal and oil) significantly increases carbon emissions in India.

- H2: Foreign direct investment positively contributes to carbon emissions through energy-intensive industrialization.

- H3: Economic growth moderates the long-term relationship between energy consumption and environmental degradation.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Oil and Coal Consumption

2.2. Oil Consumption and Carbon Emissions

2.3. FDI and Carbon Emissions

2.4. Growth (GDP) and CO2: EKC and Structural Change

3. Methods

3.1. Data and Model

3.2. Econometric Procedure

3.3. Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL)

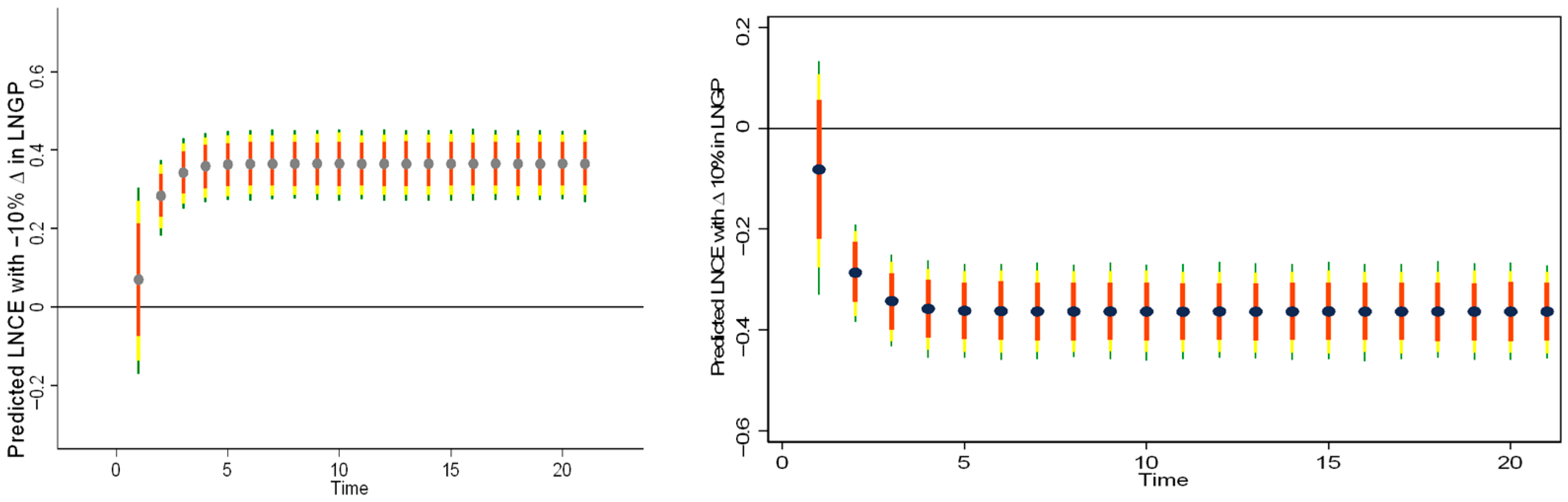

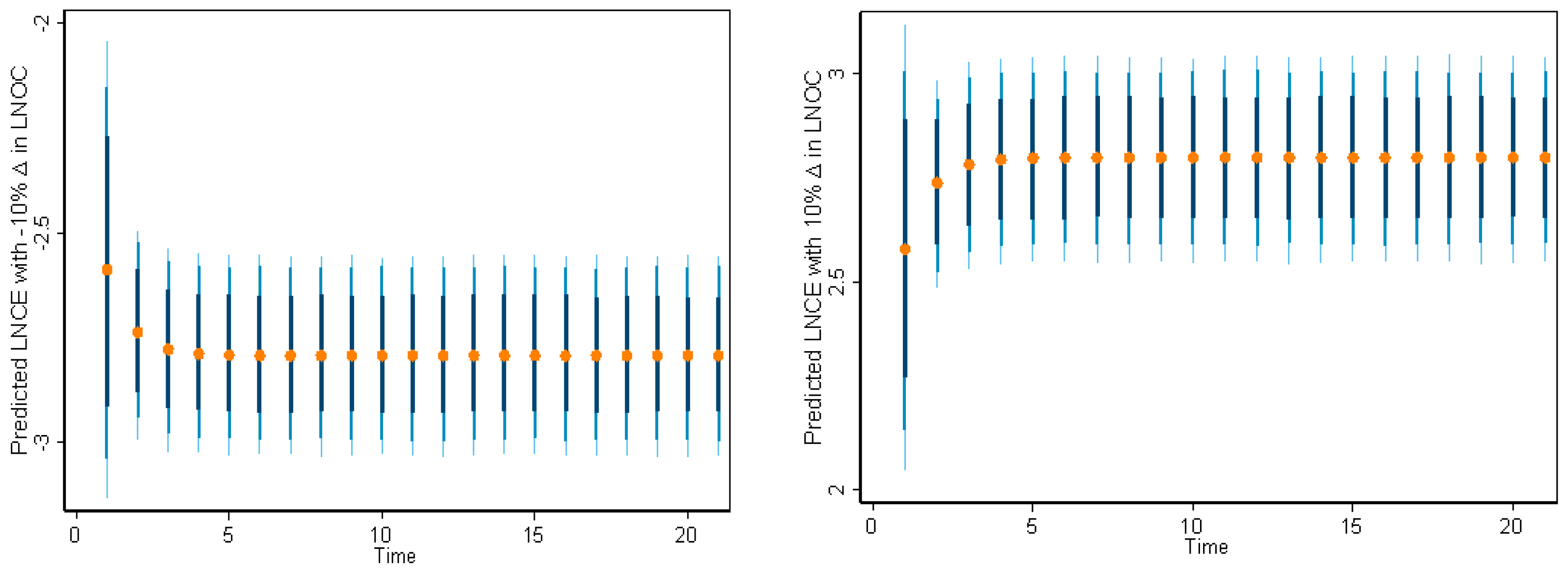

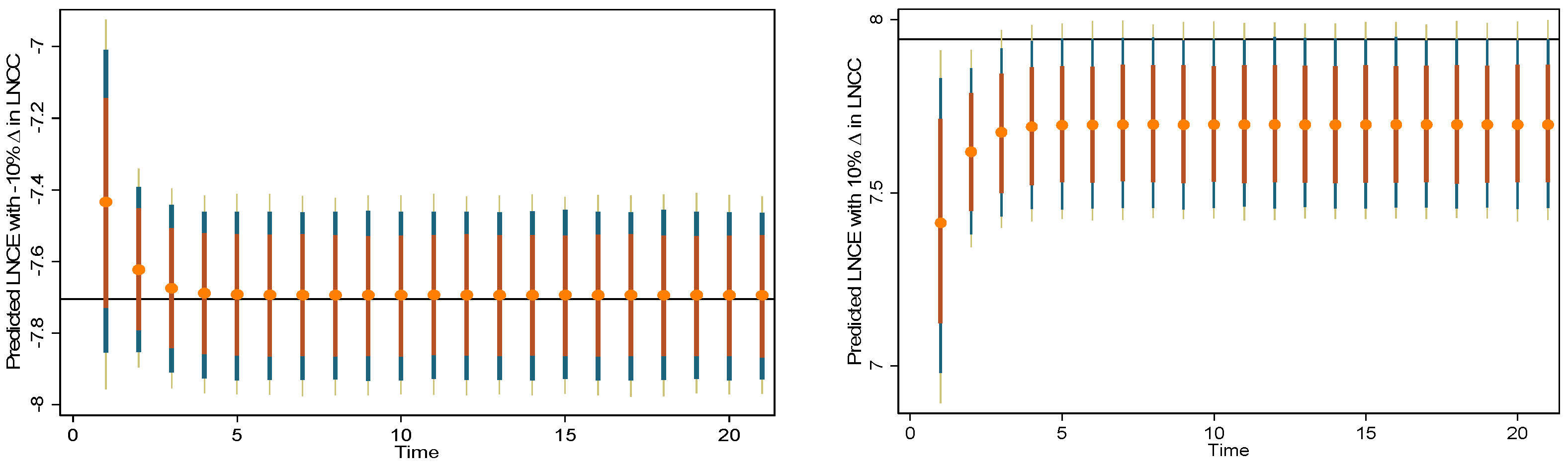

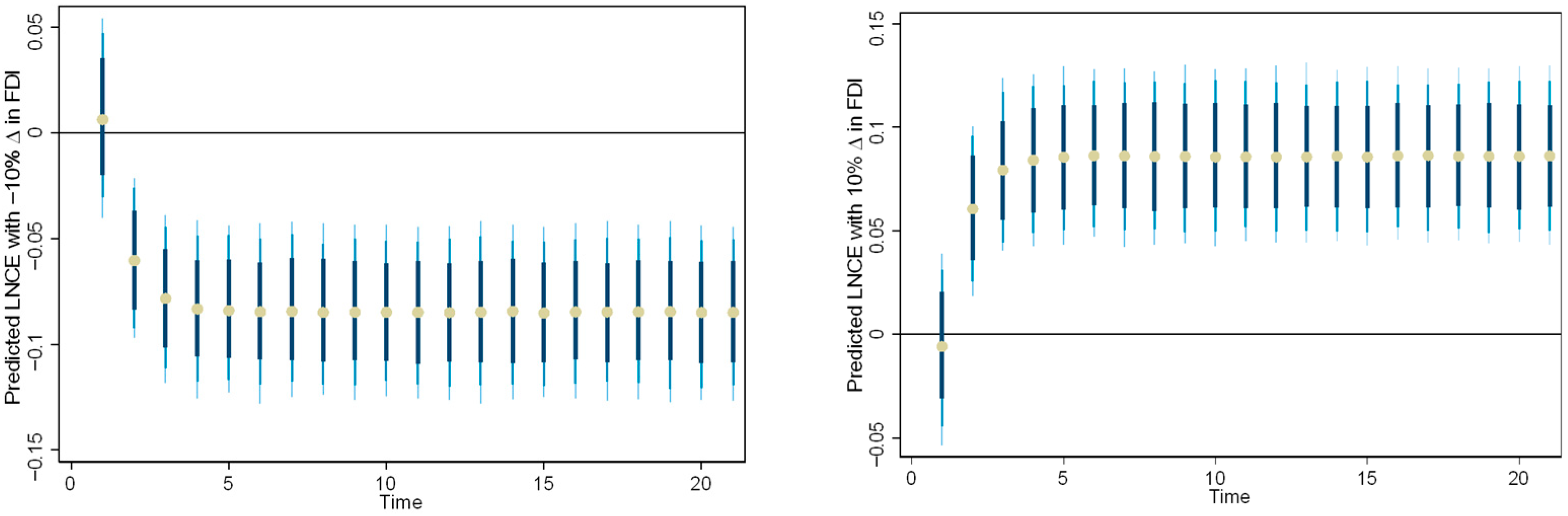

3.4. Dynamic ARDL Simulation

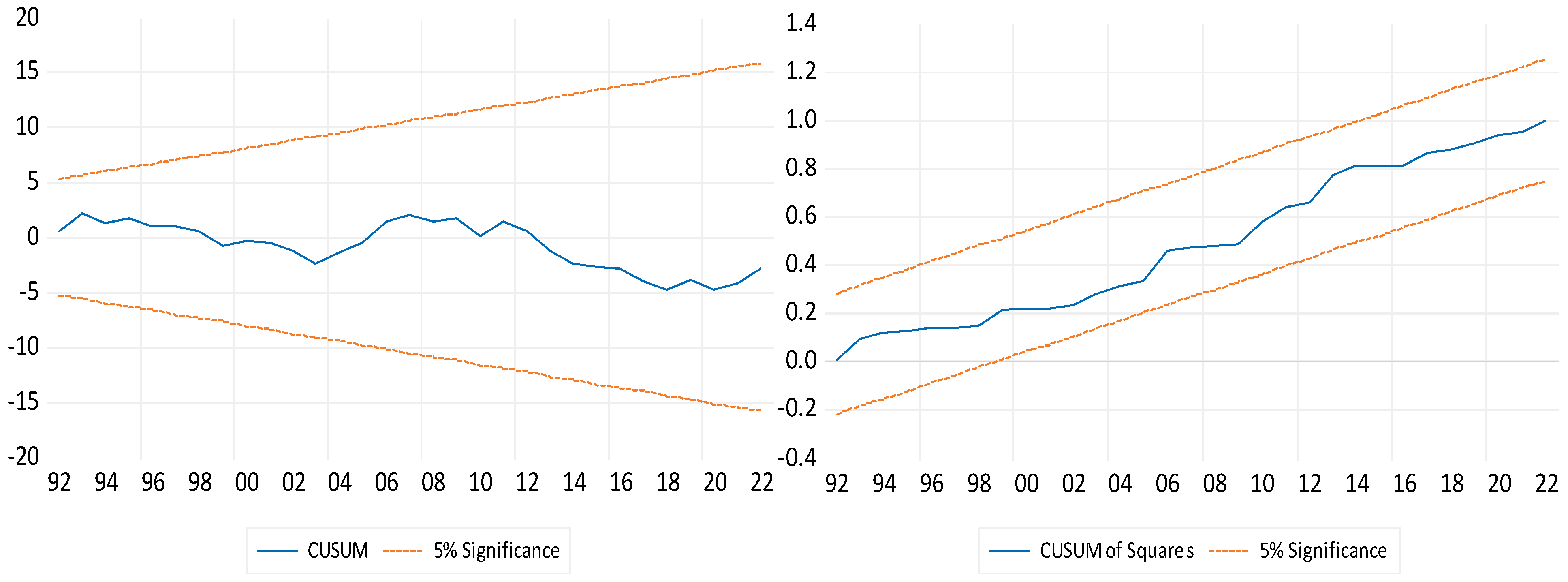

3.5. Model Stability

4. Conclusions

4.1. Policy Suggestions

- Create and put into action thorough urban planning policies that put mixed-use, compact urban development first to promote public transportation and lower energy use.

- To meet the energy needs of growing urban areas, push for and give money to switch to renewable energy sources like solar, wind, and hydropower.

- Use carbon pricing methods like cap-and-trade systems or carbon levies to get cities and businesses to cut down on their emissions.

- Encourage the use of electric and hybrid public transportation and give people reasons to switch to electric vehicles. This will lower the number of hydrocarbons used and released by the transportation sector.

- Support and improve energy efficiency codes and green building standards to cut down on the amount of energy buildings and operational structures use.

- To deal with the carbon emissions that come from waste management, push for a circular economy that focuses on recycling, reducing, and using resources more efficiently.

- You and your group are the ones who can make a difference. Your actions can help a group reduce its carbon footprint, invest in renewable technologies, and adopt environmentally friendly business practices. Not only will you get tax breaks and other financial benefits, but you will also help India achieve its broader sustainability goal.

- Create public awareness campaigns and educational programs that stress the need to cut down on carbon emissions, save energy, and promote sustainable development.

4.2. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Y.; Ramzan, M.; Li, X.; Murshed, M.; Awosusi, A.A.; Bah, S.I.; Adebayo, T.S. Determinants of carbon emissions in Argentina: The roles of renewable energy consumption and globalization. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 4747–4760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.; Ma, H.; Ahmad, M.; Öztürk, I.; Işik, C. An Asymmetrical Analysis to Explore the Dynamic Impacts of CO2 Emission to Renewable Energy, Expenditures, Foreign Direct Investment, and Trade in Pakistan. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 53520–53532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Sinha, A.; Inuwa, N.; Wang, Y.; Murshed, M.; Abbasi, K.R. Does structural transformation in economy impact inequality in renewable energy productivity? Implications for sustainable development. Renew. Energy 2022, 189, 853–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachiyappan, D.; Alam, M.S.; Khan, U.; Khan, A.M.; Mohammed, S.; Alagirisamy, K.; Manigandan, P. Environmental sustainability with the role of green innovation and economic growth in India with bootstrap ARDL approach. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 975177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. 2025. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-energy-review-2025/co2-emissions (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Malik, M.A. Economic growth, energy consumption, and environmental quality nexus in Turkey: Evidence from simultaneous equation models. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 41988–41999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattak, S.I.; Khan, A.M.; Khan, M.K.; Chen, L.C.; Liu, J.; Pi, Z. Do regional government green innovation preferences promote industrial structure upgradation in China? Econometric assessment based on the environmental regulation threshold effect model. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 995990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunjra, A.I.; Bouri, E.; Azam, M.; Azam, R.I.; Dai, J. Economic growth and environmental sustainability in developing economies. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2024, 70, 102341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lin, B. Impacts of Urbanization and Industrialization on Energy Consumption/CO2 Emissions: Does the Level of Development Matter? Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 52, 1107–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation. Energy Statistics 2020. Government of India. 2020. Available online: https://www.mospi.gov.in/sites/default/files/publication_reports/ES_2020_240420m.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- International Energy Agency. India Energy Outlook 2021; IEA Publications: Paris, France, 2021; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/india-energy-outlook-2021 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Khan, U. Effects of Oil Consumption, Urbanization, Economic Growth on Greenhouse Gas Emissions: India via Quantile Approach. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2013, 3, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Solarin, S.A.; Mahmood, H.; Arouri, M. Does Financial Development Reduce CO2 Emissions in Malaysian Economy? A Time Series Analysis. Econ. Model. 2013, 47, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Nasir, M.A.; Roubaud, D. Environmental Degradation in France: The Effects of FDI, Financial Development, and Energy Innovations. Energy Econ. 2018, 74, 843–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murshed, M.; Apergis, N.; Alam, M.S.; Khan, U.; Mahmud, S. The impacts of renewable energy, financial inclusivity, globalization, economic growth, and urbanization on carbon productivity: Evidence from net moderation and mediation effects of energy efficiency gains. Renew. Energy 2022, 196, 824–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Qiu, R.; Tu, Y. Pulling Off Stable Economic System Adhering Carbon Emissions, Urban Development and Sustainable Development Values. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 814656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharya, M.; Paramati, S.R.; Ozturk, I.; Bhattacharya, S. The Effect of Renewable Energy Consumption on Economic Growth: Evidence from Top 38 Countries. Appl. Energy 2016, 162, 733–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafindadi, A.A. Does the Need for Economic Growth Influence Energy Consumption and CO2 Emissions in Nigeria? Evidence from the Innovation Accounting Test. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 62, 1209–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkodie, S.A. The invisible hand and EKC hypothesis: What are the drivers of environmental degradation and pollution in Africa? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 21993–22022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkodie, S.A.; Strezov, V. Assessment of contribution of Australia’s energy production to CO2 emissions and environmental degradation using statistical dynamic approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 639, 888–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafindadi, A.A.; Usman, O. Globalization, Energy Use, and Environmental Degradation in South Africa: Startling Empirical Evidence from the Maki Cointegration Test. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 244, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. 2013: Index. In Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis; Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth. Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Stocker, T.F., Qin, D., Plattner, G.-K., Tignor, M., Allen, S.K., Boschung, J., Nauels, A., Xia, Y., Bex, V., Midgley, P.M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Enerdata. Global Energy Statistical Yearbook; Enerdata: Grenoble, France, 2019; Available online: https://yearbook.enerdata.net (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Katircioglu, S. Investigating the Role of Oil Prices in the Conventional EKC Model: Evidence from Turkey. Asian Econ. Financ. Rev. 2017, 7, 498–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanif, I.; Raza, S.M.F.; Gago-de-Santos, P.; Abbas, Q. Fossil fuels, foreign direct investment, and economic growth have triggered CO2 emissions in emerging Asian economies: Some empirical evidence. Energy 2019, 171, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saboori, B.; Rasoulinezhad, E.; Sung, J. The nexus of oil consumption, CO2 emissions and economic growth in China, Japan and South Korea. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 7436–7455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koçak, E.; Şarkgüne, N.S. The Impact of Foreign Direct Investment on CO2 Emissions in Turkey: New Evidence from Cointegration and Bootstrap Causality Analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 790–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solarin, S.A.; Al-Mulali, U. Influence of Foreign Direct Investment on Indicators of Environmental Degradation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 24845–24859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baloch, M.A.; Zhang, J.; Iqbal, K.; Iqbal, Z. The Effect of Financial Development on Ecological Footprint in BRI Countries: Evidence from Panel Data Estimation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 6199–6208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, F.; Su, H.; Li, Y.; Qian, W.; Xiao, J. The impact of foreign direct investment on China’s carbon emissions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jijian, Z.; Twum, A.K.; Agyemang, A.O.; Edziah, B.K.; Ayamba, E.C. Empirical study on the impact of international trade and foreign direct investment on carbon emission for belt and road countries. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 7591–7600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, M.A.; Hossain, M.A.; Chen, S. The impact of foreign direct investment, tourism, electricity consumption, and economic development on CO2 emissions in Bangladesh. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2022, 29, 37344–37358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.S.; Hossain, M.E.; Khan, M.A.; Rana, M.J.; Ema, N.S.; Bekun, F.V. Heading towards sustainable environment: Exploring the dynamic linkage among selected macroeconomic variables and ecological footprint using a novel dynamic ARDL simulations approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2022, 29, 22260–22279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhsh, K.; Rose, S.; Ali, M.F.; Ahmad, N.; Shahbaz, M. Economic growth, CO2 emissions, renewable waste and FDI relation in Pakistan: New evidences from 3SLS. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 196, 627–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, M.; Long, X.; Dauda, L.; Mensah, C.N.; Muhammad, S. Different impacts of export and import on carbon emissions across 7 ASEAN countries: A panel quantile regression approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 686, 1019–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramati, S.R.; Ummalla, M.; Apergis, N. The effect of foreign direct investment and stock market growth on clean energy use across a panel of emerging market economies. Energy Econ. 2016, 56, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Khattak, S.I.; Khan, A.; Rahman, Z.U. Innovation, foreign direct investment (FDI), and the energy–pollution–growth nexus in OECD region: A simultaneous equation modeling approach. Environ. Ecol. Stat. 2020, 27, 203–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, S.; Jithin, P.; Umar, Z. The asymmetric relationship between foreign direct investment, oil prices and carbon emissions: Evidence from Gulf Cooperative Council economies. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2022, 10, 2080316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udemba, E.N. Mediation of foreign direct investment and agriculture towards ecological footprint: A shift from single perspective to a more inclusive perspective for India. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 26817–26834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmami, M.; Ben-Salha, O. An empirical analysis of the determinants of CO2 emissions in GCC countries. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2020, 27, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Li, Y.; Li, R. Rethinking the environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis across 214 countries: The impacts of 12 economic, institutional, technological, resource, and social factors. Palgrave Commun. 2024, 11, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, X.; Li, R.; Jiang, X. Reinvestigating the environmental Kuznets curve (EKC) of carbon emissions and ecological footprint in 147 countries: A matter of trade protectionism. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2014, 11, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voumik, L.C.; Rahman, M.; Akter, S. Investigating the EKC hypothesis with renewable energy, nuclear energy, and R&D for EU: Fresh panel evidence. Heliyon 2022, 8, e12447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Yang, T.; Li, R. Does income inequality reshape the environmental Kuznets curve (EKC) hypothesis? A nonlinear panel data analysis. Environ. Res. 2023, 216 Pt 2, 114575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, H.; Ma, C.; Arash, F. Government innovation subsidies, green technology innovation and carbon intensity of industrial firms. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 369, 122274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yu, Z.; Wang, B.; Ma, C. Environmental regulations and carbon intensity: Assessing the impact of command-and-control, market-incentive, and public-participation approaches. Carbon Manag. 2015, 16, 2499091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, B.; Çil, N. Investigating the environmental Kuznets curve modified with HDI: Evidence from a panel of eco-innovative countries. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025, 27, 16655–16682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muratoğlu, Y.; Songur, M.; Ugurlu, E.; Sanli, D. Testing the environmental Kuznets Curve hypothesis at the sector level: Evidence from PNARDL for OECD countries. Front. Energy Res. 2024, 12, 1452906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. World Development Indicators 2022; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; Available online: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- Khan, I.; Hou, F.; Le, H.P. The Impact of Natural Resources, Energy Consumption, and Population Growth on Environmental Quality: Fresh Evidence from the United States of America. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 754, 142222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkodie, S.A.; Strezov, V.; Weldekidan, H.; Asamoah, E.F.; Owusu, P.A.; Doyi, I.N.Y. Environmental Sustainability Assessment Using Dynamic Autoregressive-Distributed Lag Simulations—Nexus between Greenhouse Gas Emissions, Biomass Energy, Food and Economic Growth. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 668, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahbaz, M.; Shahzad, S.J.H.; Mahalik, M.K. Is Globalization Detrimental to CO2 Emissions in Japan? New Threshold Analysis. Environ. Model. Assess. 2018, 23, 557–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H.; Shin, Y.; Smith, R.J. Bounds Testing Approaches to the Analysis of Level Relationships. J. Appl. Econ. 2001, 16, 289–326. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2678547 (accessed on 5 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H.; Shin, Y.; Smith, R.P. Pooled Mean Group Estimation of Dynamic Heterogeneous Panels. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1999, 94, 621–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duasa, J. Determinants of Malaysian Trade Balance: An ARDL Bound Testing Approach. Glob. Econ. Rev. 2007, 36, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granger, C.W.J. Some Properties of Time Series Data and Their Use in Econometric Model Specification. J. Econom. 1981, 16, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, F.E.; Granger, C.W.J. Cointegration and Error Correction: Representation, Estimation, and Testing. Econometrica 1987, 55, 251–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, S.; Juselius, K. Maximum Likelihood Estimation and Inference on Cointegration—With Applications to the Demand for Money. Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 1990, 52, 169–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, P.K. Reformulating Critical Values for the Bounds F-Statistics Approach to Cointegration: An Application to the Tourism Demand Model for Fiji; Department of Economics Discussion Papers 2004, No. 02/04; Monash University: Clayton, Australia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, S.; Philips, A.Q. Cointegration Testing and Dynamic Simulations of Autoregressive Distributed Lag Models. Stata J. 2018, 18, 902–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.L.; Durbin, J.; Evans, J.M. Techniques for Testing the Constancy of Regression Relations over Time. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 1975, 37, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) | Phillips-Peron (PP) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I (0) | I (1) | I (0) | I (1) | |

| t-Stats | t-Stats | Adj.t-Stats | Adj.t-Stats | |

| LNCE | −1.37 | −7.39 * | −1.41 | −7.38 * |

| LNOC | −1.45 | −5.41 * | −1.14 | −5.24 * |

| LNCC | −0.43 | −7.88 * | −0.44 | −7.88 * |

| LNGP | −0.008 | −6.79 * | −0.023 | −6.8 * |

| FDI | −1.73 | −8.49 * | −1.59 | −9.59 * |

| F-Bounds Test | Significance Level | t-Bounds Test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bounds | Upper Bounds | F-Statistic | Lower Bounds | Upper Bounds | t-Statistic | |

| 2.45 | 3.52 | 17.201 * | 10% | −2.57 | −3.66 | −8.27 * |

| 2.86 | 4.01 | 5% | −2.86 | −3.99 | ||

| 3.25 | 4.49 | 2.50% | −3.13 | −4.26 | ||

| 3.74 | 5.06 | 1% | −3.43 | −4.6 | ||

| Variable | t-Stat | Coef. | Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|

| ECT(−1) | −8.27 | −0.73 | 0.00 |

| Long run | |||

| LNOC | 16.72 | 0.28 | 0.00 |

| LNCC | 39.33 | 0.77 | 0.00 |

| LNGP | −5.41 | −0.036 | 0.00 |

| FDI | 2.98 | 0.009 | 0.005 |

| Short run | |||

| ∆LNOC | 1.63 | 0.056 | 0.11 |

| ∆LNCC | 2.85 | 0.18 | 0.007 |

| ∆LNGP | 1.5 | 0.019 | 0.14 |

| ∆FDI | −2.77 | −0.007 | 0.008 |

| Cons | 8.45 | 3.12 | 0.00 |

| R-squared | 0.96 | ||

| Adj. R-squared | 0.96 | ||

| F-statistic | 255.96 | 0.00 | |

| Variable | Coef. | Prob. |

|---|---|---|

| L1_LNCE | 0.27 | 0.003 * |

| D_LNGP | −0.007 | 0.565 |

| L1_LNGP | −0.03 | 0.00 * |

| D_LNOC | 0.26 | 0.00 * |

| D_LNCC | 0.74 | 0.00 * |

| D_FDI | −0.0006 | 0.811 |

| L1_LNOC | 0.2 | 0.00 * |

| L1_LNCC | 0.56 | 0.00 * |

| L1_FDI | 0.006 | 0.003 * |

| R-squared | 1 | |

| Adj. R-squared | 0.99 | |

| F-statistic | 255.96 * | |

| Variables | FMOLS | DOLS | CCR | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | t-Stats | Prob. | Coef. | t-Stats | Prob. | Coef. | t-Stats | Prob. | |

| LNOC | 0.29 | 14.37 | 0.00 * | 0.28 | 23.42 | 0.0 * | 0.29 | 14.34 | 0.0 * |

| LNCC | 0.76 | 32.81 | 0.00 * | 0.78 | 54.67 | 0.0 * | 0.76 | 32.04 | 0.0 * |

| LNGP | −0.03 | −4.19 | 0.00 * | −0.04 | −9.29 | 0.0 * | −0.03 | −4.21 | 0.0 * |

| FDI | 0.007 | 2.1 | 0.04 ** | 0.01 | 4.62 | 0.0 * | 0.007 | 2.07 | 0.0 * |

| C | 4.26 | 61.06 | 0.00 * | 4.32 | 104.1 | 0.0 * | 4.26 | 60.74 | 0.0 * |

| Diagnostic Test Name | χ2 (p Values) | Inference |

|---|---|---|

| Breusch–Godfrey LM Test | 0.13 | No issues of Serial correlation. |

| Breusch–Pagan–Godfrey | 0.88 | No issues of heteroscedasticity. |

| Jarque–Bera | 0.097 | Estimated residuals usually are. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aldoseri, M.; Khan, A.M. Sustainable Development and Environmental Harmony: An Investigation of the Elements Affecting Carbon Emissions Risk. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9468. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219468

Aldoseri M, Khan AM. Sustainable Development and Environmental Harmony: An Investigation of the Elements Affecting Carbon Emissions Risk. Sustainability. 2025; 17(21):9468. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219468

Chicago/Turabian StyleAldoseri, Mahfod, and Aarif Mohammad Khan. 2025. "Sustainable Development and Environmental Harmony: An Investigation of the Elements Affecting Carbon Emissions Risk" Sustainability 17, no. 21: 9468. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219468

APA StyleAldoseri, M., & Khan, A. M. (2025). Sustainable Development and Environmental Harmony: An Investigation of the Elements Affecting Carbon Emissions Risk. Sustainability, 17(21), 9468. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219468