Restoring European Coastal Wetlands for Climate and Biodiversity: Do EU Policies and International Agreements Support Restoration?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

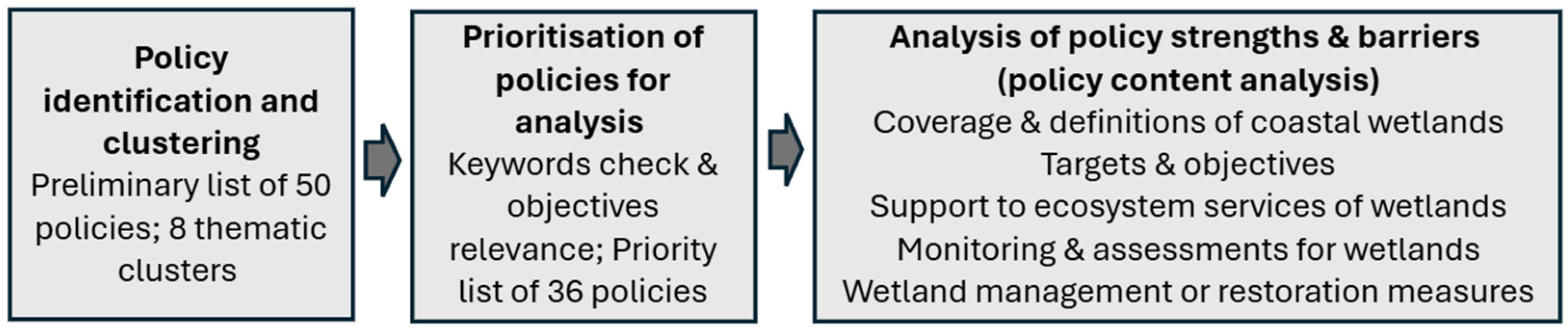

- Document and web searches were used to identify EU policies, regional and global agreements carrying the potential to support wetland protection, restoration and conservation for climate change mitigation and other co-benefits (biodiversity support, disaster risk reduction and climate adaptation, water regulation). An initial long list (50) of potentially relevant policies was compiled, covering both those directly targeting wetland conservation and restoration and those considered indirectly supportive (see Appendix A).

- The identified policies were classified into eight broad thematic clusters reflecting their primary focus areas: nature & biodiversity conservation; climate change mitigation & adaptation; water management; marine & coastal protection & management; pollution & water quality; disaster risk reduction; agriculture & soil; and cross-sectoral aspects.

- The long list of policies underwent a keyword-based screening if using specific terms (wetlands, floodplain, saltmarsh, mudflat, seagrass, ecosystems, habitat(s) and/or species, biodiversity, restoration, protection, conservation, (natural) carbon sinks, carbon sequestration/removal/storage, carbon stock(s), carbon-rich ecosystems, blue carbon, coastal nature-based solutions).

- 4.

- The policy content analysis using the standardised policy template enables the analysis of each policy’s elements and provisions to identify factors that may support or hinder coastal wetland restoration and conservation (analysis of policy strengths and policy barriers). For this, the analysis focused on five key policy elements:

- (a)

- Coverage and definitions of coastal wetland ecosystems. Assessment of whether the policy explicitly mentions specific coastal wetland types and whether it provides clear definitions of wetlands.

- (b)

- Targets/objectives. Evaluation of the presence of clearly defined targets or objectives related to (coastal) wetlands, including whether these targets or objectives are mandatory legal provisions or non-binding, voluntary commitments.

- (c)

- Support to ecosystem services of wetlands. Examination of whether the policy supports one or more ecosystem services provided by restored wetlands, including direct or indirect references to such services.

- (d)

- Monitoring and assessments relevant to (coastal) wetlands. Analysis of policy requirements related to data reporting, monitoring, or the development of assessment methods relevant to (coastal) wetlands.

- (e)

- (Coastal) wetland management or restoration measures. Review of policy measures supporting (coastal) wetland management or restoration, including mandates for management or conservation plans relevant to wetlands.

3. Results

3.1. Relevance of Policies to Coastal Wetlands Conservation and Restoration

3.2. Policy Objectives and Targets for Coastal Wetlands Conservation and Restoration

3.3. Policy Support to Retain and Enhance Ecosystem Services from Wetland Conservation and Restoration

3.4. Policy Provisions for Monitoring and Assessments Relevant to Wetlands

3.5. Policy Provisions for Wetlands Conservation or Restoration Measures

4. Discussion

4.1. Policy Strengths and Policy Barriers for Coastal Wetland Restoration

4.2. Key Policy Opportunities and Proposed Actions for Coastal Wetlands

4.2.1. Harmonising Wetland Definitions

4.2.2. Leveraging Synergies Between EU Nature and Climate Policies

4.2.3. Promoting Coastal Wetlands in the Climate Change Mitigation Framework

4.2.4. Enhancing Coastal Flood Protection

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BD | Birds Directive |

| CAP | Common Agricultural Policy |

| CBD | Convention on Biological Diversity |

| ECL | European Climate Law |

| EIA | Environmental Impact Assessment |

| EU | European Union |

| EU BDS 2030 | EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 |

| EU CRCF Regulation | EU Carbon Removals and Carbon Farming Regulation |

| EU NRR | EU Nature Restoration Regulation |

| F2F | Farm to Fork Strategy |

| FD | Floods Directive |

| GAEC | Good Agricultural and Environmental Condition |

| GBF | Global Biodiversity Framework |

| GD | Groundwater Directive |

| GES | Good Environmental Status |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gases |

| GI | Green Infrastructure |

| HD | Habitats Directive |

| HELCOM | Helsinki Commission (Baltic Marine Environment Protection Commission) |

| IAS | Invasive Alien Species |

| ICZM | Integrated Coastal Zone Management |

| INSPIRE | Infrastructure for Spatial Information in the European Community |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| LULUCF | Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry |

| MSFD | Marine Strategy Framework Directive |

| NEAES | North-East Atlantic Environment Strategy |

| Post-2020 SAPBIO | Post-2020 Strategic Action Programme for the Conservation of Biological Diversity in the Mediterranean Region |

| RED | Renewable Energy Directive |

| SEA | Strategic Environmental Assessment |

| SFDRR | Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction |

| UNFCCC | United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change |

| WFD | Water Framework Directive |

| ZPAP | Zero Pollution Action Plan |

Appendix A

| Policy Thematic Cluster | Policy Name | Screening Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Nature & biodiversity conservation | Convention on Wetlands of International Importance especially as Waterfowl Habitat (Ramsar Convention) (1971) | Selected for further analysis |

| Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) (1992) | Selected for further analysis | |

| Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment and the Coastal Region of the Mediterranean (Barcelona Convention) (1976, amended 1995) | Selected for further analysis | |

| Convention on the Protection of the Marine Environment of the Baltic Sea Area (Helsinki Convention) (1974, updated 1992) | Selected for further analysis | |

| Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic (OSPAR Convention) (1992) | Selected for further analysis | |

| Bucharest Convention on the Protection of the Black Sea Against Pollution (Bucharest Convention) (1992) | Screened out | |

| Birds Directive (BD) (2009/147/EC) (2009) | Selected for further analysis | |

| Habitats Directive (HD) (92/43/EEC) (1992) | Selected for further analysis | |

| EU Green Infrastructure Strategy (EU GI Strategy) (COM/2013/ 249) (2013) | Selected for further analysis | |

| Invasive Alien Species Regulation (IAS Regulation) (1143/2014) (2014) | Selected for further analysis | |

| EU Biodiversity Strategy 2030 (EU BDS 2030) (key action of the European Green Deal) (COM/2020/380) (2020) | Selected for further analysis | |

| EU Nature Restoration Regulation (EU NRR) (2024/1991) (2024) | Selected for further analysis | |

| Marine & coastal protection & management | Recommendation on Integrated Coastal Zone Management in Europe (EU ICZM Recommendation) (2002/413/EC) (2002) | Selected for further analysis |

| Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD) (2008/56/EC) (2008) | Selected for further analysis | |

| Marine Spatial Planning Directive (MSPD) (2014/89/EU) (2014) | Screened out | |

| Strategic Guidelines for the Sustainable Development of EU Aquaculture (COM/2021/236) (2021) | Selected for further analysis | |

| Sustainable Blue Economy Communication (COM/2021/240) (2021) | Selected for further analysis | |

| Climate change mitigation & adaptation | United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) (1992) | Selected for further analysis |

| EU Land Use Land Use Change and Forestry Regulation (LULUCF Regulation) (2018/841) (2018) | Selected for further analysis | |

| EU Strategy on Adaptation to Climate Change (key action of European Green Deal) (EU Adaptation Strategy) (COM/2021/82) (2021) | Selected for further analysis | |

| European Climate Law (key action of European Green Deal) (ECL) (2021/1119) (2021) | Selected for further analysis | |

| Sustainable Carbon Cycles Communication (COM/2021/800) (2021) | Selected for further analysis | |

| EU Carbon Removals and Carbon Farming Regulation (EU CRCF Regulation) (EU/2024/3012) (2024) | Selected for further analysis | |

| EU Renewable Energy Directive (RED) (2018/2001) (2018) | Selected for further analysis | |

| Pollution & water quality | Water Framework Directive (WFD) (2000/60/EC) (2000) | Selected for further analysis |

| Floods Directive (FD) (2007/60/EC) (2007) | Selected for further analysis | |

| European Water Resilience Strategy (COM/2025/280) (2025) | Selected for further analysis | |

| Urban Wastewater Treatment Directive (UWWTD) (recast) (EU/2024/3019) (2024) | Screened out | |

| Drinking Water Directive (recast) (EU/2020/2184) (2020) | Screened out | |

| Bathing Water Directive (76/160/EEC) (2006) | Screened out | |

| Industrial Emissions Directive (2010/75/EU) (2010) | Screened out | |

| Nitrates Directive (91/676/EEC) (1991) | Selected for further analysis | |

| Groundwater Directive (GD) (2006/118/EC) (2006) | Selected for further analysis | |

| Farm to Fork Strategy (F2F) (key action of European Green Deal) (COM/2020/381) (2020) | Selected for further analysis | |

| Zero Pollution Action Plan (key action of European Green Deal) (ZPAP) (COM/2021/400) (2021) | Selected for further analysis | |

| Directive on Environmental Quality Standards (2008/105/EC) (2008) | Screened out | |

| Pesticides Directive (proposal) (2022) | Screened out | |

| Sewage Sludge Directive (86/278/EEC) (1986) | Screened out | |

| Chemicals Strategy for Sustainability (COM/2020/667) (2020) | Screened out | |

| Agriculture & soil | Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) (Regulation (EU) 2021/2115) (2021) | Selected for further analysis |

| EU Soil Strategy 2030 (COM/2021/699) (2021) | Selected for further analysis | |

| EU Forest Strategy (COM/2021/572) (2021) | Screened out | |

| Disaster-risk reduction | Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030 (SFDRR) (2015) | Selected for further analysis |

| Cross-sectoral aspects | Environmental Impact Assessment Directive (EIA Directive) (2011/92/EU) (2014) | Selected for further analysis |

| Strategic Environmental Assessment Directive (SEA) (2001/42/EC) (2001) | Screened out | |

| Infrastructure for Spatial Information in the European Community Directive (INSPIRE Directive) (2007/2/EC) (2007) | Selected for further analysis | |

| EU Bioeconomy Strategy (COM/2018/673) (2018) | Selected for further analysis | |

| EU Sustainable Finance Taxonomy Regulation (2020/852) (2020) | Selected for further analysis | |

| Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage (1972) | Screened out | |

| Bern Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats (1982) | Screened out |

References

- Otero, M.; Camacho, A.; Abdul Malak, D.; Kampa, E.; Scheid, A.; Elkina, E. How Can Coastal Wetlands Help Achieve EU Climate Goals? RESTORE4Cs Project. 2024. Available online: https://restore4cs.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Policy-Brief_web-1.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Costa, M.D.P.; Wartman, M.; Macreadie, P.I.; Ferns, L.W.; Holden, R.L.; Ierodiaconou, D.; MacDonald, K.J.; Mazor, T.K.; Morris, R.; Nicholson, E.; et al. Spatially explicit ecosystem accounts for coastal wetland restoration. Ecosyst. Serv. 2023, 65, 101574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsch, W.J.; Bernal, B.; Hernandez, M.E. Ecosystem services of wetlands. Int. J. Biodivers. Sci. Ecosyst. Serv. Manag. 2015, 11, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Bellerby, R.; Craft, C.; Widney, S.E. Coastal wetland loss, consequences, and challenges for restoration. Anthr. Coasts 2018, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN. Issues Brief on Blue Carbon; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2017; Available online: https://iucn.org/sites/default/files/2022-07/blue_carbon_issues_brief.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2024).

- Reise, J.; Urrutia, C.; von Vittorelli, L.; Siemons, A.; Jennerjahn, T. Potential of Blue Carbon for Global Climate Mitigation; German Environment Agency: Dessau-Roßlau, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, J.; Hoyt, S.; Isensee, K.; Telszewski, M.; Pidgeon, E. Coastal Blue Carbon: Methods for Assessing Carbon Stocks and Emissions Factors in Mangroves, Tidal Salt Marshes, and Seagrasses; Conservation International, Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of UNESCO, IUCN: Arlington, VA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Santalla, I.; Navarro, N. Main threats in Mediterranean coastal wetlands. The Ebro Delta Case. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsar Convention Secretariat. Principles and guidelines for incorporating wetland issues into Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM). In Proceedings of the 8th Meeting of the Conference of the Contracting Parties to the Convention on Wetlands (Ramsar, Iran, 1971), Valencia, Spain, 18–26 November 2002; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, S.; Kawabe, M.; Rewhorn, S. Wetland conservation and sustainable coastal governance in Japan and England. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2011, 62, 956–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission: Directorate-General for Environment; Silva, J.P.; Jones, W.; Phillips, L. LIFE and Europe’s Wetlands: Restoring a Vital Ecosystem; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, J.; Teller, A.; Erhard, M.; Conde, S.; Vallecillo Rodriguez, S.; Barredo Cano, J.I.; Paracchini, M.; Abdul Malak, D.; Trombetti, M.; Vigiak, O.; et al. Mapping and Assessment of Ecosystems and Their Services: An EU Ecosystem Assessment; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojica Vélez, J.M.; Barrasa García, S.; Espinoza Tenorio, A. Policies in Coastal Wetlands: Key Challenges. Environ. Sci. Pol. 2018, 88, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.G. The Evolution of Coastal Wetland Policy in Developed Countries and Korea. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2010, 53, 562–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsamara, T.; Ghazi, F. Legal Protection of Coastal Wetlands: A Case Study of Mediterranean Sea. J. Ecohumanism 2024, 3, 1923–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouillard, J.; Lago, M.; Abhold, K.; Roeschel, L.; Kafyeke, T.; Klimmek, H.; Mattheiß, V. AQUACROSS Deliverable 2.1: Synergies and Differences Between Biodiversity, Nature, Water and Marine Environment EU Policies; Ecologic Institute: Berlin, Germany, 2016; p. 532. Available online: https://aquacross.eu/sites/default/files/D2.1_Synergies%20and%20Differences%20between%20EU%20Policies%20with%20Annexes%2003112016.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Davis, M.; Abhold, K.; Mederake, L.; Knoblauch, D. NATURVATION Deliverable 1.5: Nature-Based Solutions in European and National Policy Frameworks; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018; p. 50. [Google Scholar]

- Morseletto, P.; Biermann, F.; Pattberg, P. Governing by targets: Reductio Ad Unum and evolution of the two-degree climate target. Int. Environ. Agreem. Polit. Law Econ. 2016, 17, 655–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carré, A.; Abdul Malak, D.; Isabel Marín, A.; Trombetti, M.; Ruf, K.; Hennekens, S.; Mücher, S.; Stein, U. Comparative Analysis of EUNIS Habitats Modelling and Extended Ecosystem Mapping: Toward a Shared and Multifunctional Map of European Wetland and Coastal Ecosystems; European Topic Centre on Biological Diversity: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- European Environment Agency. State of Nature in the EU Results from Reporting Under the Nature Directives 2013–2018; EEA: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Duwe, M.; Graichen, J.; Böttcher, H. Can Current EU Climate Policy Reliably Achieve Climate Neutrality by 2050? Post-2030 Crunch Issues for the Move to a Net Zero Economy; Ecologic Institute, Oeko-Institut: Berlin, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission: Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development, Agrosynergy, ECORYS, METIS; Chartier, O.; Krüger, T.; Folkeson Lillo, C.; Valli, C.; Jongeneel, R.; Selten, M.; Avis, E.; Rouillard, J.; Underwood, E.; et al. Mapping and Analysis of CAP Strategic Plans: Assessment of Joint Efforts for 2023–2027; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picourt, L.; Delrieu, E.; Thomas, T.; Comstock, M.; Gauttier, F. Political Narrative. Including Coastal Wetlands Within the European Union Climate Strategy; Ocean & Climate Platform: Paris, France, 2021; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Ryfisch, S.; Seeger, I.; McDonald, H.; Lago, M.; Blicharska, M. Opportunities and Limitations for Nature-Based Solutions in EU Policies—Assessed with a Focus on Ponds and Pondscapes. Land Use Policy 2023, 135, 106957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Arcilla, A.; Cáceres, I.; Roux, X.L.; Hinkel, J.; Schuerch, M.; Nicholls, R.J.; Otero, D.M.; Staneva, J.; De Vries, M.; Pernice, U.; et al. Barriers and enablers for upscaling Coastal Restoration. Nat.-Based Solut. 2022, 2, 100032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French Ministry of Ecology, Energy, Sustainable Development and Town and Country Planning. Ramsar and Wetland Management in France; French Ministry of Ecology, Energy, Sustainable Development and Town and Country Planning: Paris, France, 2008; p. 40. [Google Scholar]

- Casajus Valles, A.; Marín Ferrer, M.; Poljanšek, K.; Clark, I. Science for Disaster Risk Management 2020: Acting Today, Protecting Tomorrow; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2760/438998 (accessed on 11 March 2025).

| Policy/Agreement (Abbreviation) 1 | Related Coastal Wetland Terms Used in Official Texts | Key Relevant Implementing Instruments or Citation |

|---|---|---|

| Ramsar Convention | Coastal wetlands, habitat types (marsh, fen, estuary, mangrove, tidal marsh, seagrass) | Convention text, i.a. Article 1.1 |

| Convention of Biological Diversity (CBD) | Wetlands (general) | Convention text; Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) (2022) 2 |

| Barcelona Convention | Coastal wetlands, estuaries, blue carbon sinks, salt marshes, salt pans, intertidal mudflats, coastal lagoons | Convention text, i.a. Art 10 of Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) Protocol; Specially Protected Areas and Biological Diversity Protocol; Post-2020 Strategic Action Programme for the Conservation of Biodiversity and Sustainable Management of Natural Resources in Mediterranean Region (Post-2020 SAPBIO) 3; Mediterranean Strategy for Marine & Coastal Protected Areas 4 |

| Helsinki Convention | Wetlands (general), coastal habitats | Annex III of Helsinki Convention; HELCOM Recommendations 18/4 & 40-1 |

| OSPAR Convention | Coastal wetland habitat types (Zostera beds, intertidal mudflats, Cymodocea meadows, seagrass beds, saltmarshes) | The North-East Atlantic Environment Strategy 2030 (NEAES 2030) 5 |

| Birds Directive (BD) | Wetland habitats, sites designated for waterbirds/wetlands | Directive text, i.a. Article 4(1) (designation of Special Protection Areas) |

| Habitats Directive (HD) | Coastal wetland habitat types (list): coastal lagoons, estuaries, salt marshes, intertidal mudflats, Zostera beds/seagrass | Directive text, i.a. Article 3 (Natura 2000/Special Areas of Conservation from Annex I (list of habitat types of community interest, includes coastal/marine habitat types)) |

| EU Green Infrastructure (GI) Strategy | Coastal wetlands, tidal habitats, blue carbon | Strategy text (EU Communication) |

| EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 (EU BDS 2030) | Coastal wetlands, specific habitats (mangroves, seagrass) | Strategy text with references to ecosystem protection and restoration targets (EU Communication) |

| EU Nature Restoration Regulation (EU NRR) | Coastal wetland Habitat types (estuaries, mudflats and sandflats, coastal lagoons, salt marshes, seagrass beds) | Regulation text, i.a. Article 4 (binding restoration targets, list of ecosystems), Annex I and Annex II |

| Invasive Alien Species (IAS) Regulation | None | Regulation text, i.a. Article 20 requires ecosystem restoration |

| Policy/Agreement (Abbreviation) 1 | Related Coastal Wetland Terms Used in Official Texts | Key Relevant Implementing Instruments or Citation |

|---|---|---|

| Strategic Guidelines for the Sustainable Development of EU Aquaculture | Ponds, wetlands and brackish waters | Communication text, i.a. Section 2.2.1 (promoting aquaculture in wetlands) |

| Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD) | None | Directive text with references to coastal environment and ecosystems, coastal and transitional waters |

| Recommendation on ICZM in Europe (EU ICZM Recommendation) | None | Recommendation text, i.a. Chapter I on the strategic approach to ICZM aiming to protection of the coastal environment, based on an ecosystem approach |

| Sustainable Blue Economy Communication | Coastal wetland Habitat types (salt marshes, seagrass fields, mangroves, dunes, coral reefs, macro-algal forests) | Communication text, i.a. references to habitats and ecosystem services |

| Policy/Agreement (Abbreviation) 1 | Related Coastal Wetland Terms Used in Official Texts | Key Relevant Implementing Instruments or Citation |

|---|---|---|

| United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) | Coastal wetland habitat types (Managed coastal wetlands including mangrove forests, managed tidal marshes and seagrass meadows) | Convention text, i.a. Article 4, par. 1 (d) (conservation of sinks and reservoirs of greenhouse gases (GHG), including coastal and marine ecosystems); Paris Agreement, i.a. Article 5 (conservation of sinks and reservoirs of GHG); IPCC Wetlands Supplement (Technical guidance) |

| EU Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry (LULLUCF) Regulation | Wetlands (general) as a managed land category for GHG accounting and carbon storage | Article 2 (scope), 7 (accounting for managed wetlands), 13b (land use mechanism for 2026–2030); recitals refer to importance of wetlands as high carbon stock ecosystems |

| European Climate Law (ECL) | None | Regulation text with references to natural sinks, emission sources; Article 5 on adaptation to climate change |

| EU Strategy on Adaptation to Climate Change (EU Adaptation Strategy) | Wetlands (general) as nature-based solutions | Strategy Communication text, i.a. Section 11 (promoting nature-based solutions for adaptation) |

| Sustainable Carbon Cycles Communication | Wetlands (general) and coastal wetlands | Communication text with references to nature-based solutions and high-carbon-stock lands |

| EU Carbon Removals and Carbon Farming (CRCF) Regulation | Wetlands (general) | Preamble refers to nature-based removals; references to wetlands and coastal environments included in the Regulation |

| EU Renewable Energy Directive (RED) | Wetlands (general) | Article 29(4)(a) on sustainability criteria defines land with high-carbon stock and explicitly includes wetlands |

| Policy/Agreement (Abbreviation) 1 | Related Coastal Wetland Terms Used in Official Texts | Key Relevant Implementing Instruments or Citation |

|---|---|---|

| Water Framework Directive (WFD) | Wetlands (general), transitional waters and coastal waters | Article 2, Annexes addressing definitions and scope; Supporting Common Implementation Strategy guidance |

| Floods Directive (FD) | None | The legal text refers to the role of certain wetland types in natural flood retention (Article 4(2)(d)) |

| European Water Resilience Strategy | Wetlands (general), coastal restoration | Strategy Communication text with reference to wetlands and coastal areas, a source-to-sea approach |

| Groundwater Directive (GD) | Wetlands (general) | Article 3 on criteria for assessing groundwater chemical status |

| Nitrates Directive | Coastal wetlands habitat types (estuaries), coastal and marine waters | Article 6, Annex I on criteria for identifying waters affected by pollution or which could be affected by pollution |

| Farm to Fork Strategy (F2F) | Wetlands (general) | Communication text includes general references to wetlands |

| Zero Pollution Action Plan (ZPAP) | None | Action Plan Communication text on zero pollution ambition for all aquatic ecosystems |

| Policy/Agreement (Abbreviation) 1 | Related Coastal Wetland Terms Used in Official Texts | Key Relevant Implementing Instruments or Citation |

|---|---|---|

| Common Agricultural Policy Regulation (CAP) | Wetlands (general) | Regulation texts refer to wetlands in conditionality rules (e.g., Good Agricultural and Environmental Conditions (GAEC)) and eco-schemes |

| EU Soil Strategy for 2030 | Wetlands (general) | Strategy Communication text with references to the role of peatlands/wetlands for carbon/soil health |

| Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030 (SFDRR) | Wetlands (general), coastal floodplain areas | Article 30(g) on mainstreaming the disaster risk assessment into rural development planning and management of different areas |

| Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) Directive | Wetlands (general) | Annex III on selection criteria to determine locations of projects for Environmental Impact Assessment considers wetlands |

| Infrastructure for Spatial Information in the European Community (INSPIRE) Directive | Wetlands (general) | Annex II on spatial data themes includes wetlands as a land cover type |

| EU Sustainable Finance Taxonomy Regulation | Wetlands (general) Coastal wetland habitats (mangroves, seagrass) | Regulation text, i.a. Article 10 on substantial contribution to climate change mitigation; Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/2139 (Climate Delegated Act); Delegated Regulation (EU) 2023/2486 (Environmental Delegated Act) |

| EU Bioeconomy Strategy | None | Strategy Communication text with references to restoration of ecosystems, water quality and biodiversity |

| Policy/Agreement (Article, If Available) | Definition of Wetlands |

|---|---|

| Ramsar Convention (Art. 1.1) | “Areas of marsh, fen, peatland or water, whether natural or artificial, permanent or temporary, with water that is static or flowing, fresh, brackish or salt, including areas of marine water the depth of which at low tide does not exceed six metres”. |

| IPCC Wetlands Supplement (Glossary) | “Land with wet soil that is inundated or saturated by water for all or part of the year to the extent that biota, adapted to anaerobic conditions, particularly soil microbes and rooted plants, control the quality and quantity of the net annual GHG emissions and removals”. A coastal wetland is defined as a “wetland at or near the coast that is influenced by brackish/saline water and/or astronomical tides”. |

| RED (Art. 29(4)(a)) | “Land that is covered with or saturated by water permanently or for a significant part of the year”. |

| Policy/Agreement | Objectives Relevant to Coastal Wetlands and Their Bindingness Degree | Targets Relevant to Coastal Wetlands and Their Bindingness Degree |

|---|---|---|

| Ramsar Convention | Designate, manage, and wisely use wetlands of international importance (binding) |

|

| CBD | Conserve biodiversity, sustainably use its components, and share the benefits fairly and equitably (binding) | GBF: Ensure 30% area-based conservation and restoration of degraded ecosystems (incl. wetlands) by 2030 (non-binding) |

| Barcelona Convention |

| Implement ICZM Protocol and Post-2020 SAPBIO targets:

|

| Helsinki Convention | Protect the Baltic Sea from all sources of pollution from land, air and sea (binding) |

|

| OSPAR Convention | Conserve marine ecosystems and, when practicable, restore marine areas which have been adversely affected (binding) | Implement NEAES 2030: Develop a regional approach to apply nature-based solutions for carbon storage and restoring relevant habitats by 2025 (seagrass beds, kelp forests, saltmarshes) and to reinstate natural capacity to sequester nutrients through conservation and restoration of estuarine, coastal, and marine habitats by 2030 (non-binding) |

| UNFCCC | Promote conservation and enhancement of sinks and reservoirs of GHGs, including coastal and marine ecosystems (binding) | Implement Paris Agreement:

|

| Policy/Agreement | Objectives Relevant to Coastal Wetlands and Their Bindingness Degree | Targets Relevant to Coastal Wetlands and Their Bindingness Degree |

|---|---|---|

| BD | Preserve, maintain and re-establish sufficient diversity and area of habitats for all wild birds (binding) |

|

| HD | Ensure that species and habitat types are maintained, or restored, to favourable conservation status in EU (binding) | Designate and manage Special Areas of Conservation for listed wetland habitat types within six years after adoption of Sites of Community Importance (binding) |

| EU BDS 2030 | Protect and restore biodiversity, including wetlands as priority ecosystems (non-binding) | By 2030:

|

| EU NRR | Restore degraded ecosystems, including coastal and freshwater habitats (binding) |

|

| MSFD | Achieve “Good Environmental Status” (GES) in marine waters, including biodiversity and seafloor integrity linked to coastal wetlands (binding) | Achieve or maintain GES in the marine environment by 2020, including coastal and transitional waters where these are not covered by the WFD (binding) |

| EU LULUCF Regulation | Account for and manage emissions/removals from land use including wetlands (binding) | Meet EU-wide net removal target of 310 Mt CO2e by 2030 through reporting and accounting for wetlands, among others (binding) |

| EU CRCF Regulation | Facilitate and encourage carbon farming in terrestrial and coastal environments (binding) | Certify carbon removals and support deployment of carbon farming in terrestrial or coastal environments (binding, where applicable) |

| Communication on Sustainable Carbon Cycles | Promote carbon farming upscaling through, i.a., restoration of wetlands that reduces carbon stocks oxidation and enhances carbon sequestration potential (non-binding) | Restore wetlands and peatlands and promote blue carbon farming, including on coastal wetlands, to upscale carbon farming up to 2030 (non-binding) |

| EU Adaptation Strategy | Promote use of wetland and coastal ecosystem restoration as cost-effective nature-based solution for adaptation (non-binding) | No specific targets for wetlands |

| WFD | Prevent further deterioration, protect and enhance the status of wetlands directly depending on aquatic ecosystems and groundwater (binding) | Achieve good ecological and chemical status of all surface water bodies and good chemical and quantitative status of all groundwater bodies by 2015, at the latest 2027 (binding) |

| European Water Resilience Strategy | Restore and protect the water cycle as basis for sustainable water supply (non-binding) |

|

| Nitrates Directive | Reduce water pollution caused or induced by nitrates from agricultural sources and prevent further such pollution of ground and surface waters (binding) | Designate Nitrate Vulnerable Zones, which may include wetlands, and apply mandatory measures to reduce pollution from nitrates (binding) |

| CAP | Protect wetlands and peatlands as part of GAEC 2 (binding, where applicable) | Ensure appropriate protection of wetland and peatland due to their role as carbon stores, as of 2025 at the latest (binding, where applicable) |

| EU Soil Strategy for 2030 | Limit drainage of wetlands and organic soils and restore managed/drained peatlands (non-binding) | By 2030, maintain/increase soil organic carbon, minimise flood/drought risks and enhance biodiversity through wetland protection and restoration (non-binding) |

| Policy/Global or Regional Agreement | Biodiversity Support | Climate Change Mitigation | Disaster Risk Reduction & Climate Change Adaptation | Water Supply and Quality Regulation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nature & biodiversity conservation | ||||

| Ramsar Convention | ++ | + | + | + |

| CBD | + | + | + | + |

| Barcelona Convention | ++ | ++ | ++ | + |

| Helsinki Convention | ++ | ++ | ||

| OSPAR Convention | + | ++ | ++ | |

| BD | ++ | |||

| HD | ++ | + | + | |

| IAS Regulation | + | |||

| EU GI Strategy | + | + | + | + |

| EU BDS 2030 | ++ | ++ | + | + |

| EU NRR | ++ | ++ | ++ | + |

| Climate change mitigation & adaptation | ||||

| UNFCCC | + | ++ | + | |

| EU LULUCF Regulation | + | ++ | ||

| EU Adaptation Strategy | + | + | + | + |

| ECL | + | ++ | + | |

| Communication on Sustainable Carbon Cycles | + | ++ | + | + |

| EU CRCF Regulation | ++ | + | + | + |

| RED | + | + | ||

| Marine & coastal protection | ||||

| EU ICZM Recommendation | + | + | ||

| MSFD | + | |||

| Strategic Guidelines for the Sustainable Development of EU Aquaculture | + | + | ||

| Communication on Sustainable Blue Economy | ++ | ++ | ++ | |

| Water management | ||||

| WFD | + | ++ | ||

| FD | +/− | + | ||

| European Water Resilience Strategy | + | ++ | ||

| Pollution & water quality | ||||

| GD | + | + | ||

| Nitrates Directive | + | + | ||

| F2F | + | |||

| ZPAP | + | |||

| Agriculture & soil | ||||

| CAP | +/− | +/− | + | |

| EU Soil Strategy 2030 | + | + | + | + |

| Disaster risk reduction | ||||

| SFDRR | ++ | |||

| Cross-sectoral aspects | ||||

| EU Sustainable Finance Taxonomy | + | ++ | ++ | + |

| EIA Directive | + | + | ||

| INSPIRE Directive | ||||

| EU Bioeconomy Strategy | + | + | + | |

| Strengths What levers do policies offer to support coastal wetlands protection and restoration?

| Barriers Are there elements in the policies that limit the protection and restoration of coastal wetlands?

|

| Opportunities Are there any potential opportunities linked to policies which could benefit coastal wetland restoration?

| |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kampa, E.; Elkina, E.; Bueb, B.; Otero Villanueva, M.d.M. Restoring European Coastal Wetlands for Climate and Biodiversity: Do EU Policies and International Agreements Support Restoration? Sustainability 2025, 17, 9469. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219469

Kampa E, Elkina E, Bueb B, Otero Villanueva MdM. Restoring European Coastal Wetlands for Climate and Biodiversity: Do EU Policies and International Agreements Support Restoration? Sustainability. 2025; 17(21):9469. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219469

Chicago/Turabian StyleKampa, Eleftheria, Evgeniya Elkina, Benedict Bueb, and María del Mar Otero Villanueva. 2025. "Restoring European Coastal Wetlands for Climate and Biodiversity: Do EU Policies and International Agreements Support Restoration?" Sustainability 17, no. 21: 9469. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219469

APA StyleKampa, E., Elkina, E., Bueb, B., & Otero Villanueva, M. d. M. (2025). Restoring European Coastal Wetlands for Climate and Biodiversity: Do EU Policies and International Agreements Support Restoration? Sustainability, 17(21), 9469. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219469