Abstract

Achieving gender diversity and women’s empowerment (SDG 5) is not only a social priority but also a key driver of sustainable financial resilience. This study investigates whether the presence of women on bank boards strengthens the stability of financial institutions in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), where gender diversity remains limited yet is steadily growing. Using a balanced panel of 61 commercial banks across nine MENA countries from 2012 to 2020, we assess whether board gender diversity enhances the predictive performance of Early Warning Systems (EWSs) for bank distress. Applying a logit random-effects model, our results show that a higher proportion of female directors significantly lowers the probability of bank failure and improves EWS accuracy. Further analyses reveal that gender-diverse boards foster stronger governance by reducing operating costs, boosting profitability, and supporting higher capitalization and liquidity, indicating more prudent and risk-averse oversight. Robust tests using the Z-score and System Generalized Method of Moments (System-GMM) confirm these outcomes. Moreover, a non-linear pattern emerges: the stabilizing influence of women directors is most pronounced during financial crises but less evident in stable periods. These findings underscore the strategic value of women’s leadership in banking, offering insights for policymakers and regulators aiming to advance SDG 5 and promote resilient, inclusive financial systems.

1. Introduction

During the last decades, the financial liberalization movement has led to major difficulties in the banking sector, particularly in developing countries [1,2]. At the same time, the increasing connectedness between financial markets intensified the contagion effects, leading to a proliferation of banking crises [3]. It therefore became a priority for developing countries to prevent the onset of these crises, given their huge economic damage. This effort should be made at the micro level, because the default of one bank can destabilize the banking system as a whole, leading to a systemic crisis [4].

Early Warning Systems (EWSs) are one of the most widely used tools to predict and prevent bank failure. Based on a set of bank-specific and macroeconomic variables, they make it possible to evaluate the probability of occurrence of a banking crisis [5]. When a critical threshold is triggered, the bank managers or the supervisory authorities can implement the appropriate corrective measures to prevent the outbreak of the crisis, and thus protect the banking system [6]. Given the importance of this forecasting exercise, the construction of warning systems has grown considerably, giving rise to a lively debate about the empirical methodology and the variables to be integrated with these models [5,7].

Based on the idea that a financial crisis is simply the result of high macroeconomic imbalances, the early EWS relied exclusively on macroeconomic indicators such as the indebtedness ratio and the fiscal deficit [2,8]. However, Kaminsky and Reinhart [2] have already emphasized the necessity to complete these models by introducing microdata relative to banks. The CAMELS indicators are widely used to assess a bank’s financial situation. They refer to six key points related to banking activity: capital adequacy, asset quality, earnings, management, liquidity, and sensitivity to market risk. They represented an appropriate starting point for various empirical works aiming to build effective EWS [9]. For instance, Ahern and Dittmar [10] and Jin, Wang and Gao [11] showed that associating the CAMELS indicators with variables reflecting the internal control and the audit quality within the bank allows for enhancing the predictive power of an EWS. However, despite the abundant literature devoted to this theme, studies emphasizing the impact of the board of directors’ gender diversity on the probability of bank default are very scarce. Indeed, an important body of literature identified poor banking governance as a major cause of financial crises [12,13]. At the same time, various studies emphasized that the presence of women in the boardroom leads to improved board governance [14,15,16]. It is therefore important to investigate if incorporating more women on the board of directors can help to better predict the outburst of bank distress.

Beyond governance quality, gender dynamics themselves are deeply embedded in cultural and institutional routines within the MENA region. Women’s access to senior banking roles is shaped by entrenched gender norms, implicit bias in evaluation and promotion processes, and evolving, but still uneven, organizational inclusion practices. These dynamics mean that when women do enter boardrooms, they may bring distinctive oversight styles (often described as more risk–averse, participatory, and data-driven) that interact with the sector’s cultural context. Understanding these dynamics is essential to assess whether gender diversity contributes to more effective EWS and to the stability of banks in environments where formal gender–diversity policies are still emerging [17,18].

In this paper, we try to bridge these gaps by investigating the impact of the board of directors’ gender diversity on the default probability of 61 banks operating in 9 MENA countries. This study aligns explicitly with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 5 “Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls.” It informs target 5.5 “ensure women’s full and effective participation and equal opportunities for leadership at all levels of decision-making” by examining whether female board representation strengthens the resilience of financial institutions. Linking gender diversity to banking stability not only fills a research gap but also offers actionable insights for policymakers and regulators seeking to advance SDG 5 within the financial sector [18,19,20].

In the MENA region, the lack of gender diversity in the boardrooms of the listed firms is quite alarming. A recent study by Deloitte [21] revealed that in MENA country-listed firms, women hold 10.2% of the board seats, 4.1% of board chairs, and only 1.6% CEOs. This situation is often attributed to the existence of significant cultural barriers preventing the integration of women into the business world [22]. However, mindsets are changing rapidly in this region, leading to increased participation of women in the labor market and a significant shift towards gender balance. The banking system is at the beginning of this trend. The banking and finance industry has by far the largest female presence on boards of directors in the MENA region: 93 financial firms reported having at least one female director. A major event confirming this shift was the appointment of women COEs as the head of Arab Bank, First Abu Dhabi Bank and Samba Financial Group. The banking industry represents therefore an interesting field of experimentation for the whole region. The success of the feminization strategy undertaken by this sector could accelerate the current trend and lead to greater representation of women on corporate boards. Female directors are expected to boost the firms’ social agenda, enhance the level of sustainability reporting, and improve banking stability due to their strong risk aversion and their tendency to make data-driven decisions [23]. This potential remains underexplored: it is unclear whether these governance and cultural shifts translate into measurable reductions in insolvency risk.

Our contribution to existing literature is threefold. First, the article focuses on a region for which very few studies have dealt with the presence of women in the governing bodies of banks. It provides robust empirical evidence highlighting the benefits that can be drawn from enhancing gender diversity in the boardrooms of MENA banks. Using a panel random effects logit model, results show that a higher percentage of female directors is associated with a lower default probability. Moreover, the EWS integrating gender diversity among the dependent variables is the one exhibiting the highest predictive power. Secondly, the article investigates the transmission channels through which gender diversity may contribute to reducing the likelihood of bank failure. Findings show that female directors provide effective monitoring by lowering the bank’s operating costs and boosting financial performance. Results also suggest that banks with more gender-diverse boards are holding higher capitalization and liquidity ratios, which reflects stronger risk-averse behavior. Similar results are obtained by applying the SGMM estimator while retaining the Z-score as a dependent variable, which confirms the robustness of our findings. Finally, a last set of estimations reveals that the involved transmission channels are operational only during periods of high instability, which suggests the existence of a non-linear relationship between gender diversity and banking stability. It seems that the rigorous management enforced by female directors is effective only during financial turmoil.

Beyond the econometric evidence, our findings should also be interpreted considering the strong socio-cultural context that characterizes the MENA banking sector. Gender norms, implicit bias in promotion, and historically male-dominated governance routines often restrict women’s strategic influence under normal conditions [24]. However, during periods of heightened uncertainty, the participatory and risk-averse leadership style frequently attributed to female directors may become more valued, enabling them to exercise stronger oversight and impose prudent capital and liquidity buffers [25]. This dynamic helps explain why the stabilizing effect of gender diversity appears stronger in times of financial turmoil. It also suggests that policies aiming to empower women on boards must go beyond numerical representation and address deeper inclusion practices, such as equal access to key committees, transparent evaluation processes, and cultural change programs, to unlock the full stabilizing potential of female leadership.

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides a brief review of the theoretical and empirical literature dealing with the board’s gender diversity and banking stability. Section 3 describes the models and the empirical methodology. Empirical results are summarized and discussed in Section 4. Section 5 concludes and provides some policy recommendations.

2. Theoretical and Empirical Underpinnings of the Board’s Gender Diversity

2.1. Theoretical Perspectives on Board Gender Diversity

Literature supporting gender diversity relies on theories emphasizing the benefits that can be drawn from diversifying the composition of the board of directors. Based on the agency theory, developed by Fama and Jensen [26] and Jensen and Meckling [27], some studies have argued that female directors provide more effective monitoring than their male counterparts [16], which reduces the agency cost within the company and promotes its financial performance [28]. A higher percentage of female directors also leads to higher attendance at the board meetings [14], which enhances the monitoring quality. Tougher monitoring is particularly noticeable when women are sitting in the audit, nominating, and corporate governance committees [29,30,31,32].

On the other hand, the resources dependency theory supports the idea that an increased presence of women will lead to a fruitful exchange of ideas and expertise, thus improving decision-making within the board [33,34,35]. Ahern and Dittmar [10] viewed the board’s gender diversity as a renewal of the decision-making entity, which allows the firm to take advantage of a diverse pool of profiles and expertise. Along the same vein, Terjesen, Sealy and Singh [36] asserted that a higher presence of women on the board of directors enhances the decision-making process by providing valuable insights and expertise, which helps to better achieve the board’s objectives. The company will take advantage of the network and external linkages of the female directors, which is expected to produce a positive impact on financial performance [37]. Eagly and Carli [16] pointed out that firms can also benefit from the leadership of female directors.

Unlike the agency theory, the stewardship theory refutes the existence of a conflict between shareholders and managers and considers that they aim jointly to increase the firm’s value [38]. In this respect, the positive effect that female directors may produce on the firm’s stability and financial performance may be attributed to their lawfulness and their high degree of engagement in the tasks to which they are assigned [39]. As they are clearly under-represented, women are keen to prove that they deserve a greater place on the board and to hold decision-making positions within the company [40]. Moreover, Eagly and Carli [16] argued that women are characterized by a participative leadership style, which transforms the way the board operates, reduces the likelihood of conflicts, and favors long-term strategies [41].

On the other hand, the stakeholders’ theory states that homogeneous boards focus mainly on financial performance to meet the shareholders’ objectives. Consequently, they give little attention to the interests of the various partners of the firm [42]. In this regard, diversifying the composition of the board, by including more female directors may be considered a commitment of the firm to take into account the interests of all the stakeholders [43]. Evidence suggests that women directors care more than men about self-transcendence values and thus better meet the needs of socially responsible firms [44,45,46]. For instance, El Nemar, El-Chaarani [47] and Galletta, Mazzù [48] confirmed that gender diversity is an important driver of environmental sustainability in banks, either directly, or indirectly, through their lending activity.

Finally, the Resource-Based View provides valuable insights into how firms can achieve and sustain competitive advantage by leveraging their unique resources and capabilities, which are difficult for competitors to imitate or replicate. It has become a foundational theory in strategic management and continues to influence research and practice in the field [47]. Although the Resource-Based View framework itself does not explicitly address gender diversity, it has become widely recognized that female directors can influence the composition, utilization, and strategic implications of a firm’s resources and capabilities, potentially shaping its competitive advantage and long-term success [31].

2.2. Gender Diversity in Banking Governance and Stability

Gender diversity refers to the representation of women and men across roles, hierarchies, and decision-making levels within an organization or sector. Increasing gender diversity is not only a demographic shift but a foundational step toward achieving gender equality, which implies equal rights, responsibilities, opportunities, and access to resources for all genders. Building on these theoretical lenses, a substantial body of research has explored how gender diversity shapes governance quality and the financial stability of banks. The empirical literature dealing with the gender diversity-stability nexus showed that female directors may promote the bank’s soundness, either directly, by shaping the bank’s strategy and risk-taking behavior, or indirectly, by boosting its performance [49,50]. Various studies highlighted the positive effect produced by gender diversity on financial performance. For a sample of 159 European banks, García-Meca, García-Sánchez and Martínez-Ferrero [12] found that a higher percentage of female directors is associated with a higher financial performance. This positive effect is, however, dependent on the quality of the regulatory framework. Based on a sample covering more than 90% of the assets of the European banking system, Cardillo, Onali and Torluccio [51] showed that gender diversity promotes financial performance as proxied by the ROA and Tobin’s Q. A similar result was also detected by Adams and Ferreira [29] for the Tobin’s Q. Ref. [52] found that the financial performance of Nigerian banks is positively impacted by the board’s gender diversity. For a sample of 90 US banks, Owen and Temesvary [53] showed that female participation in the boardrooms spurs financial performance only in better-capitalized banks and once a threshold of gender diversity is reached. In a recent study, Galletta, Mazzù [48] confirmed that a higher proportion of female directors boosts both the financial and environmental performance of banks, arguing that women are more willing to consider the stakeholders’ interests than their male counterparts.

The positive direct effect of gender diversity on banking stability is also well documented. Most of the empirical literature attributed this effect to the high-risk aversion of female directors [44,54]. In this respect, Cardillo, Onali and Torluccio [51] provided robust evidence showing that gender diversity reduces the probability of receiving a public bailout for a sample of listed European banks. Specifically, they found that an increase of one standard deviation in gender diversity decreases the probability of a bailout by at least 2.44%. For a sample of 99 European banks, Farag and Mallin [55] detected a reduced vulnerability to financial crisis when women represent, respectively, more than 18% and 21% of the board of directors and the supervisory board. Similarly, Faccio, Marchica and Mura [56] highlighted that firms run by female executives have lower leverage, less volatile earnings, and a higher chance of survival. Moreover, transitions from male to female executives are associated with statistically significant reductions in corporate risk-taking. In line with these conclusions, Palvia, Vähämaa and Vähämaa [57] provided empirical evidence suggesting that small banks with female chief executives or with women in chair positions are less likely to default during a financial crisis. According to Dhir [58], these results are probably because gender-diverse boards are more effective at managing risk and making decisions during turmoil periods.

The empirical literature dealing with the impact of gender diversity on banking stability is inconclusive. Besides the studies providing supportive results for the board’s gender diversity, an important body of literature has led to different outcomes. The first set of results showed that gender diversity may be detrimental to financial performance [59,60]. Following these results, Adams and Ferreira [29] argued that imposing gender quotas can lead to negative outcomes. Another stream of studies highlighted that female directors are less averse than their male counterparts [44,55] and showed that higher percentages of female executives are associated with higher risk exposure [50].

Such neutral or negative effects may be explained by the fact that diversity results in communication problems, leading to more conflicts within the board [29]. A group of individuals with very different views and beliefs is less likely to implement a clear and coherent strategy. For Lazzaretti, Godoi [40], despite the political and institutional pressure to promote the board’s gender diversity, women are still unable to reach decision-making positions, which prevents them from helping shape the firm’s strategy. Similarly, Claire, Silber [61] pointed out that female directors are simple “tokens” in the boardrooms unless a critical mass of female directors is reached. Moreover, Sila, Gonzalez and Hagendorff [62] argued that opting for less risk-taking behavior will make firms less competitive in the long run, which may hinder financial performance. Other studies highlighted the additional costs associated with gender diversity. Adams and Ferreira [29] found that more gender-diverse boards are receiving higher equity-based compensation, while Kara, Nanteza [63] showed that banks with higher percentages of female directors are more engaged in charity and donations. Sila, Gonzalez and Hagendorff [62] emphasized that female directors may be chosen to meet the preferences and needs of the firm. Accordingly, banks willing to reduce their risk exposure should appoint risk-averse female directors, while banks engaged in risky strategies should prefer directors known for their low-risk aversion. In this way, introducing more female directors to the boards will not affect the firm’s strategy.

Finally, the expected positive effect associated with gender diversity is often attributed to the ability of female directors to bring additional ideas, expertise and connections. However, as asserted by Johnson [64], women still need to act independently and fully affirm their views to enhance decision-making with the board. In many cases, female directors are adopting the old boys club behavior to be fully integrated into the new environment. Consequently, their presence does not lead to any significant change in the way the board operates.

2.3. Cultural and Institutional Determinants of Gender Diversity in MENA Banking

The effectiveness of gender diversity in banking is closely tied to the cultural and institutional environment. In MENA countries, board composition is shaped not only by firm-level governance but also by deeply embedded norms and regulatory frameworks. Despite global progress, women remain underrepresented on boards and continue to face barriers such as traditional gender roles, male-dominated networks, and limited public-sphere participation [65,66,67]. Institutional settings strongly mediate the impact of diversity. Ownership structures and investor activism alone are insufficient without supportive governance frameworks and regulatory enforcement [68,69,70,71]. Although recent reforms and governance codes have encouraged inclusion, progress remains uneven due to entrenched cultural routines. Even where gender diversity improves bank performance, its effect depends on institutional quality and rule enforcement [72,73]. Differences between conventional and Islamic banks further highlight how cultural–religious identity shapes both women’s appointments and the outcomes of diversity [70,74,75]. Broader financial inclusion dynamics also influence board diversity: systemic gender gaps in access to finance limit the pipeline of qualified female leaders [76,77] while informal networks and cultural perceptions of leadership suitability still restrict advancement [19,20,66,70].

Overall, numerical representation alone is insufficient. The influence of female directors depends on institutional quality, governance codes, and cultural change. Stronger support, through transparent promotion processes, diversity disclosure requirements, and investor pressure, can enhance women’s impact on risk oversight and banking stability. Despite these insights, little is known about how board gender diversity interacts with cultural and institutional realities to influence bank default risk in the MENA region. Moreover, few studies have explored whether incorporating gender diversity can strengthen the predictive power of EWS for banking stability or examined the mechanisms through which female directors affect risk outcomes.

Most existing studies have focused on developed markets or treated gender diversity as a simple board characteristic, without integrating the cultural and institutional context that shapes its effectiveness in the MENA region. Research rarely examines whether gender diversity can enhance the predictive power of EWS, a key tool for preventing bank failure, nor does it clarify the mechanisms through which female directors influence risk outcomes. Furthermore, while theoretical work highlights women’s risk aversion and participatory decision-making, empirical support in emerging financial systems with patriarchal norms and evolving governance codes is still scarce.

This study advances the literature in three ways.

This study offers contextual novelty by examining how board gender diversity affects bank default probability in the MENA region, where women’s leadership in finance is growing but remains constrained by socio-cultural barriers. It provides a methodological contribution by testing whether the inclusion of gender diversity improves the predictive accuracy of Early Warning Systems (EWSs), using both logit random-effects and System-GMM estimations, and by explicitly validating model robustness with the Z-score. Finally, it delivers a mechanism-focused analysis by exploring the channels through which female directors may reduce failure risk—such as cost control, profitability, capitalization, and liquidity—while assessing whether these effects are non-linear and stronger during periods of financial turmoil. Together, these contributions directly support Sustainable Development Goal 5 (Gender Equality) by linking women’s leadership to the resilience and stability of financial institutions.

Building on the theoretical perspectives of agency and resource-dependency, and the socio-cultural and institutional dynamics affecting MENA banks, we develop a set of testable hypotheses. Table 1 summarizes each hypothesis alongside its theoretical rationale, expected directional effect, and the corresponding empirical support reported in this study.

Table 1.

Hypotheses, Theoretical Foundations, Expected Effects, and Empirical Findings.

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Models’ Specification and Variables Definitions

The early literature dealing with banking stability relied on single soundness indicators, such as the capital adequacy ratio or the standard deviation of return on assets [78]. However, various scholars pointed out the incapacity of a single financial indicator to reflect the variety of risks affecting banking activity and emphasized the importance of developing a composite stability index [79]. In this respect, the Turkish Central Bank (2006) [80,81] developed a financial strength index encompassing six sub-indices reflecting, respectively, interest rate risk, foreign exchange risk, profitability, capital adequacy, asset quality and liquidity. Similarly Gersl and Hermanek [82] developed an aggregate index based on six financial indicators. The weights associated with these partial indicators are based on experts’ judgments. The Overall financial strength index (OFSI), developed by Doumpos, Gaganis and Pasiouras [78], is a weighted average of five financial criteria reflecting the CAMEL framework. The optimal weights associated with the five variables are determined via a Monte Carlo simulation. Accordingly, banks are classified into five categories from very weak to very strong.

The main advantage of this indicator is that it reflects various dimensions of the banking activity: profitability (via the average return on assets ratio), management quality (assessed through the cost ratio), capitalization (through the capital adequacy ratio), asset quality (gauged by the loans loss provision ratio) and liquidity risk (measured by the liquid assets ratio). It provides, therefore, a global evaluation of a bank’s soundness. However, this indicator suffers from important shortcomings. Firstly, the construction of this index requires a very large number of simulations and relies on ad hoc assumptions regarding the weights assigned to the variables and banks’ risk aversion. Secondly, the OFSI does not take into consideration the risks associated with foreign liabilities, including exchange risk, which became a source of growing instability for banks due to the rapid pace of international financial integration. Thirdly, the financial ratios should be normalized when introduced in the composite index to obtain equal variances for all of them. This is not the case with the OFSI, which considers the levels of the financial ratios. Finally, the OFSI considers simultaneously variables capturing the sources of risk and others reflecting the capacity of the bank to absorb these risks, which seriously affects the coherence of this index. For instance, an increase in the Capital Adequacy Ratio (CAR), Return on Assets (ROA), and Liquidity Ratio is associated with sounder banks, while an increase in the Cost to Income Ratio and the Problem Loans Ratio indicates a deterioration of the bank’s stability. An increase in the OFSI is, therefore, ambiguous to interpret.

To overcome these drawbacks, this study relies on two fragility indicators: the Banking Fragility Index (BFI) developed by Kibritçioğlu [83] and the traditional Zscore. First, these indicators are complementary, since the FBI captures the sources of risk, while the Zscore reflects the capacity of the bank to absorb these risks. Together, they offer a complete picture of a bank’s soundness by assessing both its risk exposure and its capacity to face this risk. Secondly, comparing the estimation outcomes yielded by two different stability indicators should ensure the robustness of our results.

The main objective of this study is to investigate if an increased presence of female directors contributes to lowering the default probability of banking firms operating in the MENA region. We also aim to check if introducing internal governance mechanisms among the independent variables may enhance the predictive power of the model and lead to a more efficient EWS. To achieve these goals, we estimate the following model:

where α0 is the constant term, βi coefficients associated with the independent variables, υi an individual random effect relative to bank i and εit the error term. Crisisit is a dummy variable which takes 1 if bank i is considered as highly exposed to insolvency risk in period t and 0 otherwise. Various methodologies have been implemented to identify episodes of high banking instability. Following a strand of the previous studies [83,84], we opt for the Banking Fragility Index (BFI) to identify periods during which banks are suffering from financial distress. This indicator is defined as follows:

where CPSit, FLit, and DEPit represent the annual rates of change in Claims on Private Sector, Foreign Liabilities and Deposits, respectively, while μ and σ stand for their mean values and standard deviations. The underlying assumption of this indicator is that banking crises are characterized by high deposit withdrawals (banking runs), a sharp drop in claims in the private sector (due to an increase in non-performing loans), and a strong decrease in foreign liabilities (due to the depreciation of the domestic currency). The simultaneous occurrence of these three events clearly indicates that the bank is facing major financial difficulties. The main advantage of this indicator is that it covers a large scope of risks, as it assesses the bank’s exposure to the credit risk, the liquidity risk, and the currency risk simultaneously. A fall in the BFI can be interpreted as an increase in banking fragility. A negative BFI is a sign of financial fragility as it indicates that one or more variables composing the index are below their average values. Banks are supposed to be facing moderate fragility if the index ranges between 0 and −0.5, while they are considered as suffering from high fragility if the BFI’s value is less than −0.5.

In a second step, we try to assess the determinants of banking stability, while retaining the Zscore as a dependent variable:

The Zscore corresponds to the sum of the return on assets and the equity-to-assets ratios divided by the standard deviation of the return on assets. Following Delis, Hasan and Kazakis [85] a five-year rolling time window is used to calculate the standard deviation of the ROA. Banks with lower values of the Zscore are considered highly exposed to insolvency risk, while higher Zscores are associated with more resilient banks. The advantages of using the Zscore as a dependent variable is threefold:

- The variable Crisis is a dummy variable. It allows us to identify the independent variables producing a significant effect on banking stability to the point of tipping into a situation of financial distress. In contrast, the Zscore is a continuous variable, and thus makes it possible to better account for the impact of all the explanatory variables on banking stability, no matter how small.

- Including the lagged Zscore among the independent variables is crucial because it is likely that banks that have recently experienced high instability are more prone to be subject to financial turmoil during the current period. That is, banking stability is highly persistent [86].

- Comparing estimation outcomes of models 1 and 2 should help identify the variables that have the greatest impact on banking stability and confirm the robustness of the results provided by Model (1).

The set of independent variables reflects the characteristics of the board of directors: the board’s size, the percentage of female directors, the percentage of independent directors, the number of board’s meetings, the number of committees, the attendance rate at the board’s meetings, and the number of the audit committee’s meetings. Larger boards and higher percentages of female and independent directors are expected to boost the exchange of ideas within the board, thereby leading to better decision-making and higher stability. More meetings and committees and a higher attendance rate are associated with tighter monitoring and should, therefore, contribute to enhancing stability.

The control variables include the bank’s financial variables, which capture instability stemming from bank-specific characteristics, and macroeconomic variables, which control for differences in cross-country economic risk. The bank’s size (Assets) produces an ambiguous effect on stability. Large banks benefit from economies of scale [87], and enjoy lower financing costs and high market shares, which should boost their revenues and positively impact their stability. However, the too big to fail theory argues that big banks trigger a moral hazard problem, as they engage in risky strategies expecting that the cost of a banking failure would be mutualized over the whole banking system. Other studies highlighted that, above a critical size, banks should incur diseconomies of scale. The capital adequacy ratio (CAR) should spur stability, as better-capitalized banks are less exposed to insolvency risk. Similarly, holding more liquid assets (Liq) should enhance soundness by protecting banks against liquidity risk. However, liquid assets provide low returns, which may deteriorate performance and thereby stability. High cost-to-income ratios (CIR) reflect a deteriorated management efficiency and should therefore increase the default probability. Banks exhibiting high loan-to-assets ratios (Loans) should enjoy high-interest income, but are seriously exposed to credit risk. Finally, higher profitability, proxied by the return on assets ratio (ROE), should contribute to enhancing the bank’s soundness.

At the macro level, banks are expected to achieve better performance during high growth periods, which increases their resilience. At the same time, boom periods are characterized by the prevalence of adverse selection problems during the credit-granting process, which is detrimental to banking stability. On the other hand, a sharp deterioration of the macroeconomic environment should naturally lead to a stronger probability of default. The inflation rate is a widely used proxy for macroeconomic instability. Table 2 summarizes the definitions of the variables included in models (1) and (2).

Table 2.

Variables Definitions.

3.2. Sample and Methodology

The conventional econometric methods assume that the dependent variable is continuous and unbounded, which is not the case with Model (1). We therefore use logistic regression, well suited for binary outcomes such as bank default. The odds ratios are reported in Table A2 to enhance interpretability. As a robustness check, we also estimated a probit model, an alternative specification for binary data. The probit results were highly consistent with the logit model, showing no meaningful differences in sign, magnitude, or statistical significance. These checks confirm the robustness and practical relevance of our findings.

An Early Warning System (EWS) intends to estimate the probability of the occurrence of a banking failure. The dependent variable is bounded (ranges between 0 and 1), while the outcome of the estimated equation is limitless (the predicted value may vary from −∞ to +∞). To overcome this problem, a transformation is applied to the predicted values of the dependent variable to transform them into probabilities. Let Zit be the outcome of the estimated equation:

Zit may vary from −∞ to +∞. However, the following transformation of Zit yields values ranging between 0 and 1:

This transformation stands for the probability that the dependent variable, Yit, takes the value 1 conditional on the information contained in the set of independent variables, Xit. Finally, a logistic transformation is applied to this probability to obtain the following model:

The model is estimated by applying the Maximum Likelihood method. Following the literature, we retain a fragility prediction threshold of 0.5 (Crisisit takes 1 if Pit > 0.5). The performance of the Logit model is assessed through the prediction accuracy in Table 3, which summarizes the overall error rates. Two types of errors can be associated with an early warning system: misidentification of fragility on one side and false alarms on the other side. The best specification is the one that minimizes both types of errors.

Table 3.

The prediction accuracy.

Results provided by the Logistic regression may be seriously affected by an endogeneity problem stemming mainly from reverse causality. To confirm the robustness of our results, we estimate Model (2) while applying the System GMM estimator which controls for endogeneity. Model (2) also offers the possibility to capture the persistence of turmoil periods by introducing a dynamic term in the model. Estimation methods designed for static models (i.e., fixed and random effects) are not suitable for Model (2), which includes the lagged dependent variable among the independent variables. In this case, applying the within or the FGLS estimators may lead to inconsistent results due to the autocorrelation between the dynamic term and the error term. Moreover, endogeneity stemming from reversed causality between the Zscore and some independent variables may lead to biased estimates. The difference-GMM estimator developed by Arellano and Bond [88] deals with endogeneity and autocorrelation. This estimator removes the bank-specific effects and uses the lagged levels as instruments of the differenced variables. However, the second and higher order lags are often weak instruments of the difference variables, which reduces the robustness and the efficiency of the difference-GMM estimator. Alternatively, we use the System-GMM estimator developed by Arellano and Bover [89] and Blundell and Bond [90], which estimates a system composed of the difference and level equations and specifies a different set of instruments for each of them. The System-GMM estimator is more efficient, particularly when the dependent variable is highly persistent, which is likely to be the case in our model. The validity of the System-GMM estimators relies upon two tests: (i) the Arellano and Bond [88] test confirming the null hypothesis of no second-order serial correlation in residuals; (ii) the Sargan/Hansen test used to confirm the overall validity of instruments (the null hypothesis states that instruments are jointly exogenous and are not correlated with the residuals).

Our final sample includes 61 commercial banks from nine MENA countries: Bahrain, United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia, Morocco, and Egypt and covering 2012–2020 (Table A1 and Table 4). Data was compiled from banks’ annual reports, InvestingPro, Thomson Reuters, and the World Bank Development Indicators. The size of the sample reflects the limited availability of consistent data on women’s board representation, which we collected manually and retained only for banks reporting this information across the full period. We also excluded Islamic banks and commercial banks with Islamic windows to ensure model comparability, which reduced coverage in Gulf states. Islamic and conventional banks are characterized by different economic models and present, therefore, different risk profiles. For instance, Islamic banks are exposed to specific risks, such as the Shariaa compliance risk, which is not relevant for conventional banks. Moreover, all the Islamic financial instruments are backed by real assets. As a result, Islamic banks are less exposed to the credit risk and more sensitive to negative chocks affecting the real economy. We also note that Islamic banks do not have access to the hedging instruments that are banned by the Shariaa rules. The risks associated with these two categories of banks should, therefore, be modeled separately to take into consideration their specificities.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics.

Countries such as Sudan and Iran were excluded because their systems are fully Islamic, while Iraq, Libya, Syria, Palestine, and Yemen were omitted due to political instability and severe data gaps. These selection criteria, while limiting the sample size, ensure data consistency and robustness in addressing endogeneity and cultural heterogeneity.

3.3. Descriptive Statistics and Preliminary Diagnostics

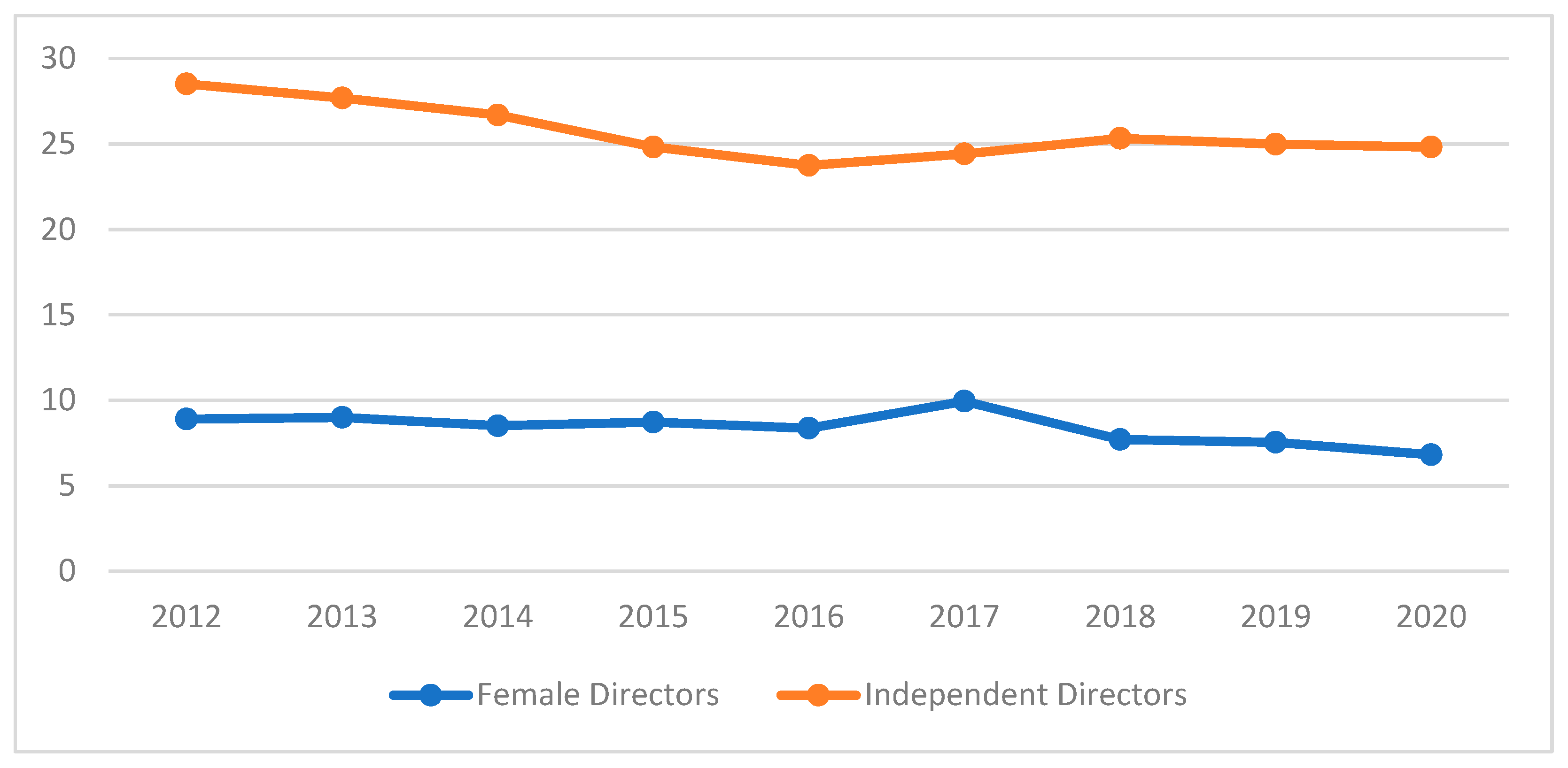

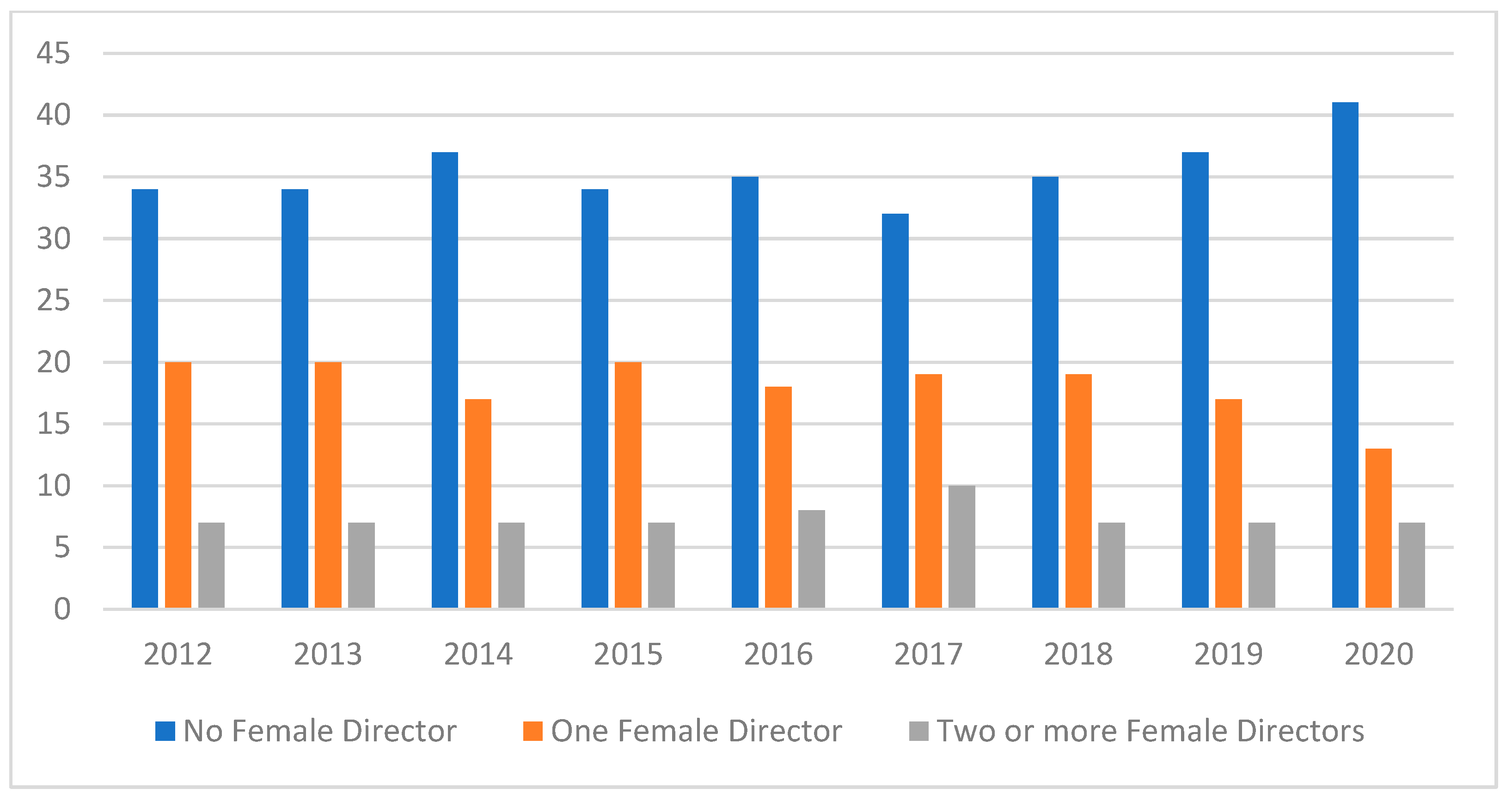

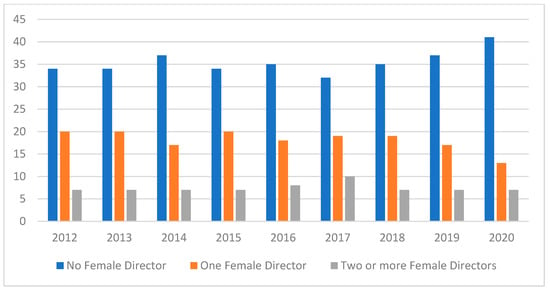

Descriptive statistics related to the variables included in both models are summarized in Table 4. We notice that gender diversity is very limited in the boards of MENA banks, with women representing only 8.39% of the board members. Figure 1 confirms that this average percentage is quite stable over the sample period. It also shows that banks in MENA countries have chosen a diversification strategy geared more towards independent directors than towards gender diversity. The percentage of women on boards is very limited compared to the percentage of independent directors, which barely exceeds 25% over the sample period. Figure 2 reveals a more alarming fact: in most banks, no women are appointed to the board of directors. These findings show the extent to which MENA countries are lagging in terms of gender diversity, particularly in the banking industry.

Figure 1.

Percentage of Female and Independent Directors, Mean values. Source: Authors’ presentation.

Figure 2.

Number of banks by number of female directors. Source: Authors presentation.

Despite the fact that the MENA region still lags behind in terms of gender diversity, a decisive step towards diversification has been made during the last decade. Annual data summarized in Table 5 shows that a large number of banks have at least one woman on their boards. A more in-depth analysis reveals that at least one woman is present on the board of directors in 65.2% of the total number of observations over the sample period (311 out of the 477 available observations). According to the critical mass theory, a minimum of two female directors is required to influence the decision-making process within the board. This is the case in 28.1% of the observations (134 out of the 477 observations).

Table 5.

Female Representation on Bank Boards in the Sample (2012–2020).

Although it cannot attest to causality, the correlation analysis may provide interesting insights into the relationship between the dependent and independent variables. It also allows for to detect potential colinearity problems, which may affect the robustness of the estimation results. As shown in Table 6, the highest negative and significant correlation coefficient is the one associated with the percentage of female directors and the crisis dummy variable (−0.42). This result suggests that gender diversity is the control variable that contributes most to reducing the likelihood of a banking crisis. Among the internal governance mechanisms, we notice that the percentage of independent directors, the number of the board’s meetings, and the attendance rate at those meetings all significantly contribute to reducing the probability of default. Enhancing internal governance seems, therefore, to play a key role in preventing a banking crisis. However, the correlation coefficients associated with the Zscore (column 2) lead to a very different conclusion: none of the governance proxies contributes significantly to promoting banking stability.

Table 6.

Correlation matrix.

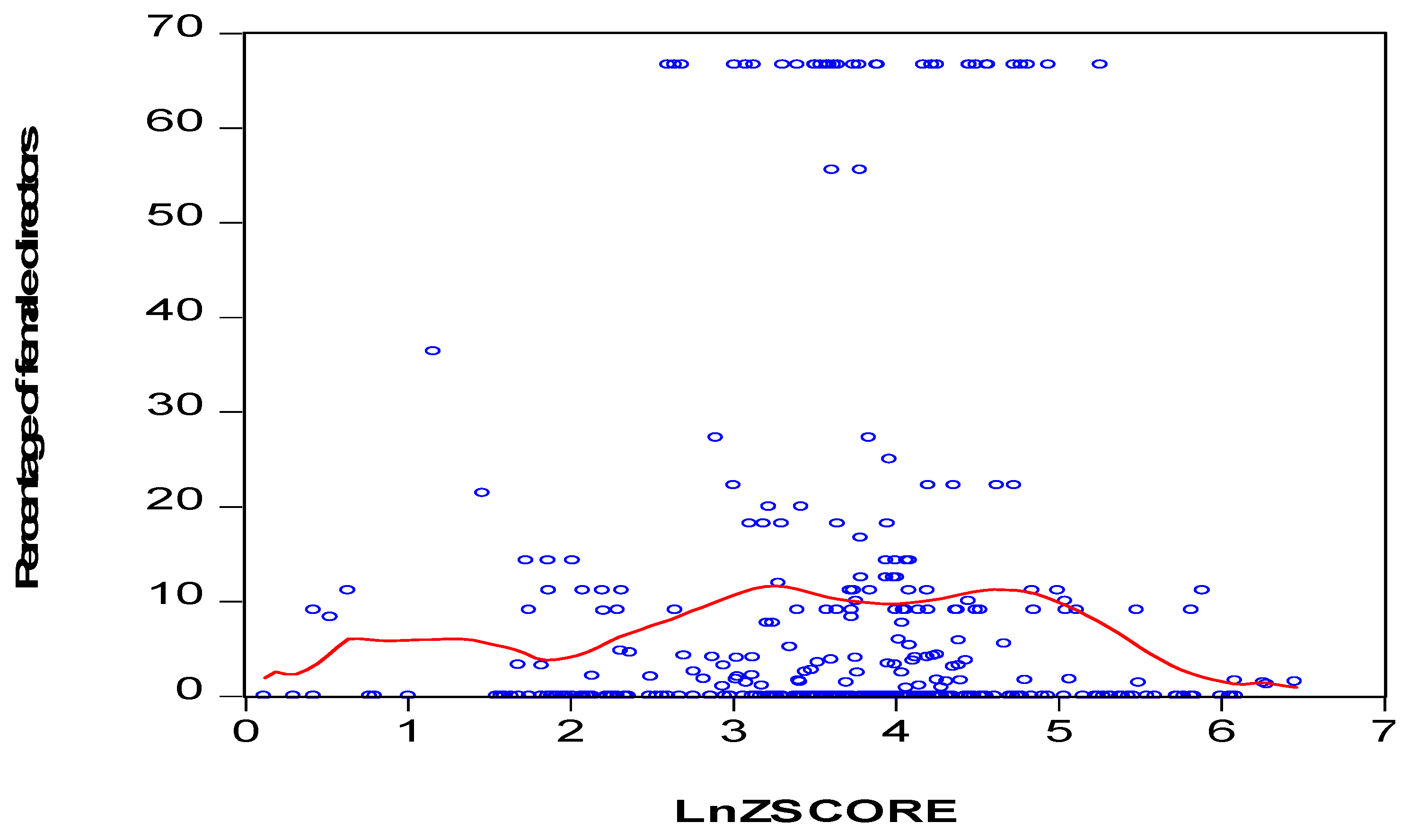

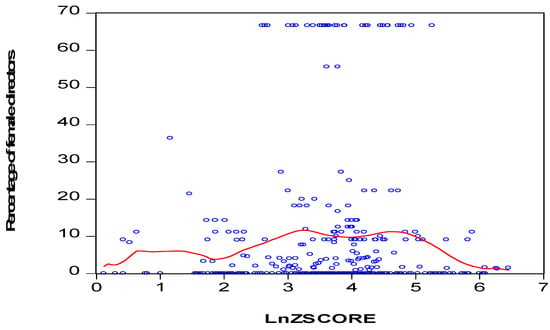

One possible explanation for these contradictory results is the non-linear effect produced by the governance proxies on banking stability. To investigate the non-linearity issue, we calculated the mean values of the Zscore and the crisis dummy variable for different intervals of gender diversity. Results in Table 7 and Table 8 show that crisis occurs most during periods when banks are exhibiting weak percentages of female directors (0.55% on average), and that the percentage of crises declines as the percentage of female directors increases. Such results suggest the existence of a linear decreasing relationship between gender diversity and the probability of default. Oppositely, results in Table 8 suggest that the average Zscore declines and then increases as the percentage of women on the board increases. Figure 3 confirms the non-linear relationship between the Zscore and the percentage of female directors. The Kernal regression curve shows that gender diversity spurs stability for weak values of the Zcore and becomes detrimental to stability when the Zscore takes high values. In other words, gender diversity is beneficial for banking stability during periods of financial turmoil (weak Zscore), while it deters stability during tranquil periods (high Zscore). The variance inflation factors (VIF) associated with the independent variables are reported at the end of Table 6 (the VIF values reported in the table correspond to fixed effects models, with the log of the Zscore as a dependent variable, and in which all the independent variables and governance proxies have been included simultaneously). We notice that despite the high value of some correlation coefficients, the model does not suffer from multicollinearity.

Table 7.

Mean percentage of female directors by Crisis.

Table 8.

Mean percentage of female directors by Zscore.

Figure 3.

The Zscore and the board’s gender diversity. Source: Authors presentation.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Gender Diversity and Default Probability

Results related to the random effects logistic regression are reported in Table 9. We first estimate a basic specification including the bank’s specific control variables, the growth rate, and the inflation rate. The internal governance proxies are then introduced alternately in the model to assess their respective effects on banking default.

Table 9.

Determinants of default probability, 2012–2020, Logit estimates.

Results relative to the basic model, summarized in column 1, show that the bank’s size, the liquidity ratio and the return on assets ratio all significantly contribute to reducing the probability of banking failure. These results are consistent with Stever [91], who emphasized that big banks have greater control over their market risk thanks to their ability to diversify their portfolios. On the other hand, banks with higher liquidity ratios are less exposed to the liquidity risk and are therefore less prone to banking distress. Similarly, a higher financial performance reduces the likelihood of banking default. This result corroborates the findings of Swamy [92] and Kjosevski, Petkovski and Naumovska [93], who argued that banking institutions with poor profits are more likely to experience financial fragility. As expected, the cost-to-assets ratio contributes to increasing the probability of default, indicating that poor management is a major driver of banking distress. Results also suggest that an increase in the loans-to-assets ratio or the inflation rate leads to a higher default probability. Providing a larger volume of loans increases the bank’s exposure to credit risk, while high inflation often stems from major macroeconomic imbalances, which are detrimental to the stability of the banking sector. Finally, the capital adequacy ratio and the GDP growth rate do not produce any significant effects on the dependent variable.

Regressions, including the internal governance mechanisms, are summarized in columns from two to eight. The estimation results reveal that gender diversity, board independence, the number of board meetings, and the attendance rate all contribute to lowering the default probability. Oppositely, larger boards prove to be a significant source of instability, while the number of committees and the audit committee’s meetings do not produce any significant effect on the probability of bank failure. Such results corroborate those of Karkowska and Acedański [94], who emphasized that costs associated with large boards seem to outweigh beneficial effects and that a stronger board structure requires more independent directors rather than a bigger size. Our results suggest that diversity matters for the monitoring quality, as boards with a higher percentage of women and independent members are associated with lower default probabilities. The odds ratios reported in Table A2 in the Appendix A confirm these findings and show that gender diversity, independence, and attendance at the meetings contribute strongly to lowering the probability of default. Such findings are consistent with those of Palvia, Vähämaa and Vähämaa [57], according to which the board’s gender diversity reduces the likelihood of bank failure during periods of market stress. Similarly, independent directors are associated with lower bank risk [94], better cost efficiency and lower variability in performance [95].

To offer further support to these conclusions, we estimate the previous models, while implementing the random effects probit estimator. The results, summarized in Table 10, confirm those provided by the logit estimator. Gender, independence, the number of meetings, and the attendance rate are the governance proxies producing a negative effect on the default probability, while gender diversity is the one impacting this probability. These results confirm the robustness of our results.

Table 10.

Determinants of default probability, 2012–2020, Probit estimates.

A key finding stemming from these results is that early warning systems should include governance proxies to enhance their predictive power. Results reported in Table 11 confirm such a conclusion. Regarding the ability to predict default events, six out of the seven models, including internal governance proxies, are performing better than the basic specification relying solely on macroeconomic and bank-specific variables. Moreover, results reveal that gender diversity is the governance proxy that leads to the lowest percentage of prediction errors and the highest rate of correct previsions. Including the percentage of female directors among the independent variables enables to predict 95.22% of bank failure events.

Table 11.

Prediction Accuracy.

To investigate the channels through which female directors may reduce the probability of default, we reestimate Model (1) while introducing iteratively the following interaction terms among the independent variables: Gender × CAR; Gender × CIR; Gender × Loans; Gender × ROE, and Gender × LIQ. A significant coefficient associated with an interaction term indicates that the marginal effect produced by gender diversity is conditional on the interaction variable. The interpretation of this conditionality effect is dependent on the sign of the coefficient. A positive sign implies that a higher value of the interaction variable curbs the impact of gender diversity on the probability of default, and indicates, therefore, the existence of a substitutability relationship between gender diversity and that variable. Oppositely, a negative sign indicates that higher values of the interaction variable increase the ability of female directors to reduce the default probability. The two variables are, therefore, complementary. For instance, if the sign associated with “CAR × Gender” is negative, this means that female directors are more successful in lowering the probability of default when banks are well-capitalized. In this case, gender diversity and the capital adequacy ratio are acting in a complementary way on the probability of default. However, a positive sign associated with this interaction term implies that gender diversity is less prone to reducing the probability of default in better-capitalized banks. In this case, gender diversity may be considered as a substitute for an adequate capitalization ratio.

Results reported in Table 12 show that female directors contribute to reducing the default probability through four main channels. On one hand, gender diversity proves to be complementary to the capital adequacy ratio and the liquidity ratio. The negative and significant coefficients associated with their interaction terms indicate that the ability of female directors to reduce the default probability is intensified in well-capitalized banks and in banks holding more liquid assets. It seems that boards made up of a high percentage of women are imposing higher capitalization and liquidity ratios, which reflects a conservative and risk-averse behavior. A similar conclusion was put forward by Palvia, Vähämaa and Vähämaa [57], who asserted that female CEOs and board Chairs should reduce the likelihood of bank failure by holding higher levels of equity capital. In the same vein, Faccio, Marchica and Mura [56] have emphasized the high risk aversion of female directors. The estimation results also show that gender diversity acts in a complementary manner with profitability on the probability of default. Such a result suggests that gender diversity reduces the likelihood of default by improving the financial performance of banks. The positive effect of gender diversity on financial performance has been evidenced by an important body of empirical literature [29,61,96].

Table 12.

Gender diversity and default probability: Main transmission channels, 2012–2020.

On the other hand, the positive coefficient associated with “CIR × Gender” shows that female directors strongly support financial stability when banks incur lower costs. Accordingly, it seems that boards including more female directors are ensuring more effective monitoring, which translates into lower cost ratios and leads to a lower default probability. Several empirical studies have already pointed out the ability of female directors to provide effective cost oversight [51,97].

4.2. Robustness Checks

To confirm the robustness of the previous findings, we estimate Model (2) where banking stability is proxied by the Zscore. Unlike the dummy variable distinguishing between tranquil and crisis periods, the Zscore provides a continuous measure of instability and allows, therefore, a better assessment of the effects produced by the independent variables on bank soundness. On the other hand, introducing the lagged Zscore in the model allows for capturing the persistence of banking instability. We implement the SGMM estimator to deal with the endogeneity and weak instruments problems.

Results relative to the basic model are reported in the first column of Table 13. They show that better-capitalization (CAR), higher performance (ROE), and higher growth rates (Growth) are associated with higher Zscores and contribute, therefore, to promote banking stability. Conversely, the bank’s soundness is impaired by an increase in the inflation rate and the loans-to-assets ratio. Providing higher loan volumes should fuel instability by increasing the bank’s exposure to credit risk.

Table 13.

Determinants of the Zscore, 2014–2020.

Results relative to the governance proxies (columns from 2 to 8) confirm the conclusions drawn from Model (1). We notice that the percentage of female and independent directors on one side, and the number of meetings and the attendance rate on the other side, are the governance mechanisms that contribute significantly to boosting banking stability. Such results suggest that the diversity of the board and the directors’ involvement in the oversight activity are important determinants of stability. To investigate the transmission channels, we introduce the interaction terms in the model. The signs associated with these terms are interpreted differently, since the Zscore and the probability of default move in opposite directions (a low value of the Zscore corresponds to a high probability of default). The results, summarized in Table 12, show that the only significant transmission channels are those associated with the capital adequacy ratio and the cost ratio. The negative sign associated with the interaction term “Gender × CIR” indicates that gender diversity contributes more strongly to promoting banking stability when the cost ratio takes lower values. Such a result suggests that gender diversity enhances the effectiveness of the monitoring process, which contributes to reducing operating costs. Such a result confirms the conclusion drawn from Model (1), emphasizing the effectiveness of the cost oversight provided by female directors.

Surprisingly, the negative sign associated with the capital adequacy ratio implies that better capitalization reduces the positive impact of gender diversity on banking stability. This finding is totally inconsistent with the results provided by Model (1), according to which gender diversity promotes stability by increasing the capitalization and liquidity ratios, thereby limiting the bank’s exposure to insolvency and liquidity risks. Such a counterintuitive result can be explained by the non-linearity of these transmission channels. Indeed, it is likely that the positive impact of a rigorous risk management strategy will only manifest during periods of financial turmoil. Inversely, during calm periods, an increase in the bank’s own capital or its liquid assets can impair financial performance and, thus, reduce the Zscore. In this respect Johnson [64] claimed that, “While risk aversion is likely desirable during an economic downturn, it is noteworthy that the same approach would not be optimal in a period of prosperity”. Budnik and Bochmann (2017) [98] detected similar non-linear relationships and emphasized that very high capital levels cease to have a tempering effect on the response of NFC (NFC stands for loans provided to non-financial companies and household) long-term loans to a real shock. Their results also suggest that high bank liquidity amplifies the effects of standard and unconventional monetary policy shocks on this category of loans. Similarly, Ali (2019) [99] argued that high buffers of capital enhance stability while reducing the net interest margin due to their opportunity cost. For Buschmann and Smaltz (2017) [100], liquidity buffers may be useful during crisis periods, but they negatively affect profitability by orienting resources to low-yielding liquid assets. Wagner (2007) [101] argued that liquidity buffers may hinder stability by encouraging banks to take on a new risk that more than offsets their positive direct impact on stability.

To investigate the non-linearity issue, we estimate Model (2) while restricting the sample to the periods during which the Zscore is below its mean value (3.78). This will make it possible to assess the effectiveness of these channels during periods of high instability characterized by weak Zscores. Results for this subsample are reported in columns from 6 to 8 of Table 14. We note that the coefficients associated with the three interaction terms are all positive and significant (at the 1% level for the capitalization ratio and the liquidity ratio and the 10% level for the return on equity ratio). Such results suggest that in times of financial turmoil, female directors help to ensure bank stability by imposing high capitalization and liquidity ratios and maintaining profitability at acceptable levels. Given the full sample results (for the full sample, the capitalization ratio reduces the effectiveness of gender diversity, while the liquidity and performance channels are non-significant), the capitalization, liquidity, and performance channels are effective only during periods of high instability. Such findings confirm the non-linear effects produced by these transmission channels.

Table 14.

Gender diversity and Zscore: main transmission channels, 2014–2020.

From an economic point of view, these results imply that a higher percentage of women on boards leads to more efficient cost management and a higher risk-averse investment strategy, which enables banks to better withstand sudden adverse changes in economic conditions. This rigorous strategy was mainly materialized by maintaining higher capitalization ratios and holding more liquid assets. During financial turmoil, such a rigorous strategy allows sounder banks to outperform their counterparts that are fully impacted by adverse financial and economic conditions. However, this strategy can hinder performance during tranquil periods by leading banks to hold low return assets. Banks are, therefore, facing a trade-off between risky strategies that can generate high revenues during boom periods, and strategies favoring stability during crisis periods at the expense of the short-run performance.

5. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

This paper assessed the impact of board gender diversity on the default probability of banks in the MENA region. We examined whether including gender diversity among the independent variables enhances the predictive power of an EWS based on bank-specific indicators and macroeconomic aggregates. We also verified whether a higher percentage of female directors strengthens banking stability and identified the transmission channels through which women directors contribute to this objective.

Results from the random-effects logistic regression show that gender diversity significantly reduces the probability of banking distress. Moreover, the model including the percentage of female directors demonstrates the highest predictive power. Results also suggest that other governance characteristics, such as the presence of independent directors, the number of board meetings, and attendance rates, help reduce default probability. These findings are confirmed by System-GMM estimations, which show that a higher share of female directors has a positive and significant effect on the Z-score, thereby strongly promoting financial stability among MENA banks.

A second set of estimations reveals that gender diversity contributes to stability by lowering costs, improving profitability, strengthening capitalization ratios, and encouraging banks to hold more liquid assets. These results emphasize the capacity of female directors to ensure effective monitoring, translating into lower cost ratios and stronger financial performance. They also highlight the risk-averse approach of female directors, whose growing presence helps reduce banks’ exposure to solvency and liquidity risks.

However, subsample analyses show that these transmission channels are effective mainly during periods of high financial instability. Under normal market conditions, the relationship between gender diversity and the Z-score becomes less dependent on profitability and liquidity, and higher capitalization may even reduce the ability of female directors to promote stability. This suggests a trade-off between stability and profitability: female directors strengthen stability but may do so at the expense of short-term profitability during calm periods.

While this study offers robust evidence on the role of gender diversity in banking stability, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, data availability remains a challenge: reliable, standardized governance disclosures in the MENA region are limited, forcing the sample to include only banks with complete records, which may introduce selection bias toward larger or more transparent institutions. Second, the region is culturally heterogeneous; variations in religion, regulatory enforcement, and social norms may shape how gender diversity translates into risk oversight, yet our design cannot fully disentangle these contextual differences. Finally, the panel ends in 2020 and therefore does not capture recent policy reforms, global shocks, or evolving diversity trends that might influence post-COVID governance dynamics. Future research could overcome these constraints by constructing richer multi-source governance datasets, combining quantitative and qualitative boardroom studies to capture informal dynamics, and conducting comparative cross-regional analyses to test whether the transmission channels identified here hold in other emerging and developed banking systems.

Importantly, all recommendations that follow are strictly based on the empirical mechanisms confirmed in our analysis, such as reduced distress probability, improved profitability, and enhanced liquidity. Our findings show that gender diversity is not merely a social goal but a measurable risk-management asset. This has several implications for regulators, central banks, and bank boards. First, regulators should treat board gender composition as a prudential risk indicator, not only as a diverse metric. Supervisory reviews could integrate gender diversity scores alongside capital adequacy and liquidity ratios when evaluating bank resilience, transforming diversity from a compliance box into a forward-looking stability signal. Secondly, Central banks and supervisory agencies could refine EWS models by including gender diversity indicators together with CAMELS and macroeconomic variables. Doing so would improve early detection of bank distress in contexts where governance weaknesses often trigger crises. Moreover, governments and development banks can tie preferential funding, guarantees, or sustainability ratings to evidence of inclusive governance. Linking green or SDG-aligned financing with gender-balanced boards would push banks to adopt diversity as part of a broader stability and sustainability strategy.

On the other hand, nomination committees should move beyond occasional appointments of high-profile women by institutionalizing leadership development programs, mentoring, and succession plans that prepare women for risk-sensitive positions (audit, risk, credit committees) where their monitoring role directly affects bank soundness. Public reporting on board composition, attendance, and committee roles can empower shareholders and investors to demand better governance. Diversity disclosure could become part of ESG reporting standards for banks, aligning with global sustainable finance frameworks. Finally, policymakers must recognize that cultural norms influence the effectiveness of diversity. Quotas or targets should be paired with regulatory guidance and training to ensure that female directors participate meaningfully, rather than remain symbolic appointees.

By reframing gender diversity as a financial stability tool, these actions should allow MENA regulators and banks to simultaneously address SDG 5 and systemic risk. Diversity becomes not only an ethical imperative but also an instrument of resilience and crisis prevention, a message especially relevant for emerging economies facing repeated financial shocks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.B.M., A.B., F.M. and J.B.; methodology, S.B.M., A.B. and F.M.; software, S.B.M., A.B. and F.M.; validation, S.B.M., A.B., F.M. and J.B.; formal analysis, S.B.M., A.B. and F.M.; investigation, S.B.M., A.B., F.M. and J.B.; resources, J.B.; writing—original draft preparation, S.B.M., A.B., F.M. and J.B.; writing—review and editing S.B.M., A.B., F.M. and J.B.; funding acquisition, J.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R540), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available to the public in http://databank.worldbank.org/data/source/world-development-indicators (accessed on 6 September 2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R540), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

List of banks by country.

Table A1.

List of banks by country.

| Country | Banks |

|---|---|

| Oman | DHOFAR BANK; Oman Arab BANK; Bank MUSCAT; HSBC Bank; AHLI SOAG; SOHAR Bank |

| Kuwait | National Bank of Kuwait; Al Ahli bank of Kuwait; Burgan Bank; Gulf Bank of Kuwait; Commercial bank of Kuwait; Industrial Bank of Kuwait |

| UAE | United Arab Bank; Emirates NBD Bank; Abu Dhabi Commercial bank; MASHREQ Bank; Commercial Bank of Dubai; First Abu Dhabi Bank; RAK Bank; Bank of Sharjah PJSC; Invest Bank PSC; Commercial Bank International PJSC; National Bank of Umm Al-Qaiwain PSC; National Bank of Fujairah |

| Tunisia | Banque internationale arabe de Tunisie; Banque Nationale Agricole; Banque de Tunisie; Attijari Bank; Arab Tunisian Bank; UBCI Bank; AMEN BANK; BH Bank; Union International de Banques; Société Tunisienne de Banque; Banque de Tunisie et des Emirats |

| Morocco | Attijeri Wafa; Bank of Africa; BMCI; Crédit du Maroc; Banque Populaire; CIH Bank |

| Egypt | Commercial International Bank Egypt; Credit Agricole Egypt; Qatar National Bank Alahly Egypt |

| Qatar | Doha Bank; International Bank of Qatar; Commercial Bank PSQC; Qatar National Bank; Ahli Bank |

| KSA | Saudi Investment Bank; Riyad Bank; Arab National Bank; Saudi National Bank; Banque Saudi Fransi; Saudi British Bank |

| Bahrain | Arab Banking Corporation; Bank of Bahrain and Kuwait; Ithmaar Holding; Ahli United Bank; National Bank of Bahrain; United Gulf Holding Company |

Source: Authors presentation.

Table A2.

Determinants of default probability, Logit estimation Odd Ratios.

Table A2.

Determinants of default probability, Logit estimation Odd Ratios.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assets | 0.6582 ** | 0.62503 ** | 0.6424 | 0.8662 | 0.553 *** | 0.6884 | 0.450 | 0.255 *** |

| (0.1174) | (0.1454) | (0.2145) | (0.1827) | (0.1224) | (0.1795) | (0.341) | (0.104) | |

| CAR | 1.0351 | 1.0270 | 0.9550 | 0.9765 | 0.9707 | 0.9942 | 1.118 | 0.995 |

| (0.0466) | (0.0533) | (0.0524) | (0.0523) | (0.0551) | (0.0613) | (0.099) | (0.074) | |

| CIR | 197.150 *** | 39.0187 * | 7447.897 ** | 123.796 ** | 1521.346 *** | 156.403 * | 4.92 × 10−17 *** | 1464.912 *** |

| (327.5841) | (76.446) | (27,799.93) | (264.1565) | (2940.427) | (440.237) | (5.19 × 10−16) | (2885.771) | |

| LIQ | 0.6650 ** | 1.9555 * | 0.4681 ** | 0.4707 *** | 0.682 * | 0.443 *** | 0.0002 *** | 0.360 *** |

| (0.1173) | (0.7117) | (0.1616) | (0.1149) | (0.1434) | (0.1313) | (0.0005) | (0.1366) | |

| LOANS | 13.3524 *** | 10.434 *** | 13.722 ** | 10.808 ** | 4.0653 | 79.785 *** | 651.467 *** | 1.325 |

| (11.9916) | (11.508) | (16.9244) | (12.5774) | (4.5490) | (107.798) | (1623.828) | (1.497) | |

| ROE | 5.34 × 10−21 *** | 4.31 × 10−25 *** | 1.55 × 10−28 *** | 3.65 × 10−21 *** | 2.35 × 10−20 *** | 1.31 × 10−25 *** | 4.27 × 10−78 *** | 1.09 × 10−16 *** |

| (3.9 × 10−20) | (4.34 × 10−24) | (2.85 × 10−27) | (3.28 × 10−20) | (1.74 × 10−19) | (1.54 × 10−24) | (2.35 × 10−76) | (7.82 × 10−16) | |

| GROWTH | 1.0299 | 1.0295 | 0.9113 | 1.0334 | 1.0421 | 0.8725 | 0.95603 | 1.091 |

| (0.05295) | (0.06266) | (0.0824) | (0.0634) | (0.0611) | (0.07379) | (0.1420) | (0.068) | |

| INFLATION | 1.2786 * | 1.2506 | 1.5485 | 1.1036 | 1.1994 | 1.4720 | 2.1217 | 1.140 |

| (0.18931) | (0.24026) | (0.4885) | (0.1930) | (0.1842) | (0.3518) | (1.6367) | (0.168) | |

| BOARD SIZE | 3.861 *** | |||||||

| (1.1655) | ||||||||

| GENDER | 9.91 × 10−49 *** | |||||||

| (1.90 × 10−47) | ||||||||

| INDEPENDENCE | 1.70 × 10−7 *** | |||||||

| (5.21 × 10−7) | ||||||||

| NB COMMITEES | 0.8281 | |||||||

| (0.1470) | ||||||||

| NB MEETING | 0.204 *** | |||||||

| (0.0609) | ||||||||

| ATTENDANCE | 2.65 × 10−44 *** | |||||||

| (7.09 × 10−43) | ||||||||

| AUDITMEETING | 1.195 | |||||||

| (0.161) | ||||||||

| Constant | 31.095 * | 0.0005 * | 6157.534 ** | 6230.616 *** | 271.557 ** | 1779.203 *** | 1.74 × 1046 *** | 129,669.4 *** |

| (63.562) | (0.002) | (24,046.52) | (17,881.36) | (725.9485) | −6,528,228 | (5.12 × 1047) | (583,690) |

Source: Authors’ calculations ***, ** and * denote 1%, 5% and 10% significance levels, respectively.

References

- Daniel, B.C.; Jones, J.B. Financial liberalization and banking crises in emerging economies. J. Int. Econ. 2007, 72, 202–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminsky, G.L.; Reinhart, C.M. The twin crises: The causes of banking and balance-of-payments problems. Am. Econ. Rev. 1999, 89, 473–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, J. Banking crises and financial integration: Insights from networks science. J. Int. Financ. Mark. Inst. Money 2015, 34, 127–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupiec, P.H.; Ramirez, C.D. Bank failures and the cost of systemic risk: Evidence from 1900 to 1930. J. Financ. Intermediation 2013, 22, 285–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrell, R.; Davis, E.P.; Karim, D.; Liadze, I. Bank regulation, property prices and early warning systems for banking crises in OECD countries. J. Bank. Financ. 2010, 34, 2255–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knedlik, T. The impact of preferences on early warning systems—The case of the European Commission’s Scoreboard. Eur. J. Political Econ. 2014, 34, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candelon, B.; Dumitrescu, E.-I.; Hurlin, C. How to evaluate an early-warning system: Toward a unified statistical framework for assessing financial crises forecasting methods. IMF Econ. Rev. 2012, 60, 75–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drehmann, M.; Juselius, M. Evaluating early warning indicators of banking crises: Satisfying policy requirements. Int. J. Forecast. 2014, 30, 759–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bräuning, M.; Malikkidou, D.; Scalone, S.; Scricco, G. A new approach to Early Warning Systems for small European banks. In Proceedings of the Machine Learning, Optimization, and Data Science: 6th International Conference, LOD 2020, Siena, Italy, 19–23 July 2020; Revised Selected Papers, Part I 6, 2020. pp. 551–562. [Google Scholar]

- Ahern, K.R.; Dittmar, A.K. The changing of the boards: The impact on firm valuation of mandated female board representation. Q. J. Econ. 2012, 127, 137–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Wang, X.; Gao, Y. Gender differences in farmers’ responses to climate change adaptation in Yongqiao District, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 538, 942–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Meca, E.; García-Sánchez, I.-M.; Martínez-Ferrero, J. Board diversity and its effects on bank performance: An international analysis. J. Bank. Financ. 2015, 53, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, A.; Rajan, R.; Stein, J. Rethinking capital regulation. Maint. Stab. A Chang. Financ. Syst. 2008, 21, 43171. [Google Scholar]

- Chou, H.-I.; Chung, H.; Yin, X. Attendance of board meetings and company performance: Evidence from Taiwan. J. Bank. Financ. 2013, 37, 4157–4171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, C.A.; Philpot, J. Women’s roles on US Fortune 500 boards: Director expertise and committee memberships. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 72, 177–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H.; Carli, L.L. The female leadership advantage: An evaluation of the evidence. Leadersh. Q. 2003, 14, 807–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbar, J. Government ownership in the MENA region: The roles of institutional voids, sociocultural norms and control-enhancing mechanisms. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2025, 25, 68–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morshed, A. Cultural norms and ethical challenges in MENA accounting: The role of leadership and organizational climate. Int. J. Ethics Syst. 2025, 41, 630–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumder, M.M.M. An empirical analysis of SDG disclosure (SDGD) and board gender diversity: Insights from the banking sector in an emerging economy. Int. J. Discl. Gov. 2025, 22, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaiss, A. Empowering All, Achieving More: A Critical Analysis of World Bank’s Gender Strategy 2.0 for Sustainable Development. 2024. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4815410 (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Deloitte, S. Deloitte; Deloitte: Westlake, TX, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Isa, S.M.; Ismail, H.N.; Fuza, Z.I.M. Integrating Women Entrepreneurs into Smes Programmes and National Development Plan to Achieve Gender Equality. J. Islam. 2022, 7, 20–31. [Google Scholar]

- Jizi, M.; Nehme, R.; Melhem, C. Board gender diversity and firms’ social engagement in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries. Equal. Divers. Incl. Int. J. 2022, 41, 186–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liem, C. Female Leaders in the Male-Dominated Industry: Is that Possible? FIRM J. Manag. Stud. 2025, 10, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Hussain, A. Board gender diversity and corporate cash holdings: Evidence from Australia. Int. J. Account. Inf. Manag. 2024, 32, 622–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E.F.; Jensen, M.C. Separation of ownership and control. J. Law Econ. 1983, 26, 301–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.C.; Meckling, W.H. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. In Corporate Governance; Gower: Surrey, UK, 2019; pp. 77–132. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, D.A.; D’Souza, F.; Simkins, B.J.; Simpson, W.G. The gender and ethnic diversity of US boards and board committees and firm financial performance. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2010, 18, 396–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.B.; Ferreira, D. Women in the boardroom and their impact on governance and performance. J. Financ. Econ. 2009, 94, 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]