The Linkage Between Cultural Ecosystem Services and Local Culture

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What are the effects of CES on LCV and PA?

- What are the internal processes within local culture among PI, PD, and LCV?

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Cultural Ecosystem Services

2.2. Cultural Ecosystem Services and Sustainable Development

2.3. Local Culture

2.4. The Linkage Between Cultural Ecosystem Services and Local Culture

2.5. Local Cultural Values, Place Identity, and Place Dependence

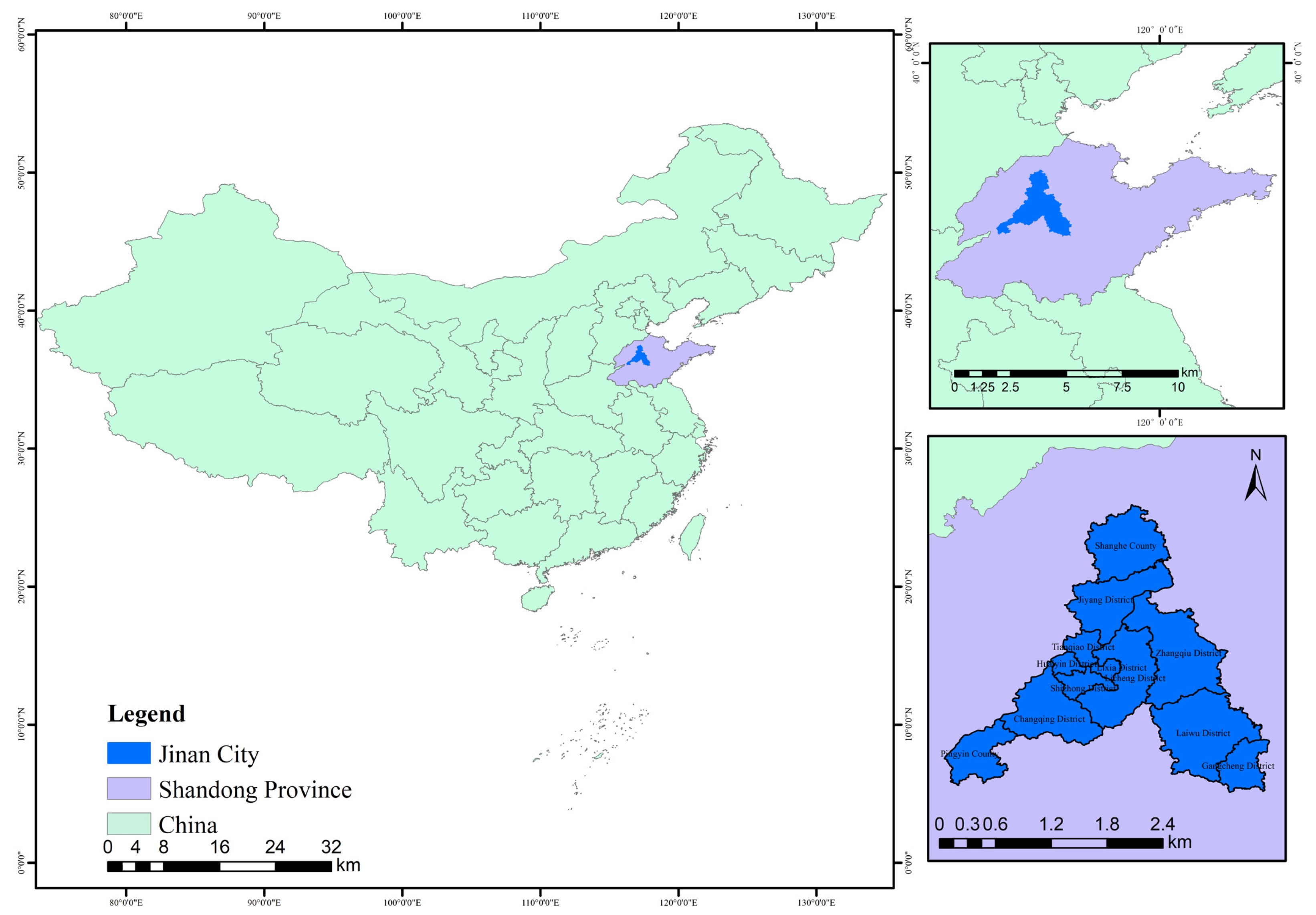

3. Research Area

4. Methods

4.1. Survey Implementation

4.2. CES Valuation

4.3. Measurements of LCV, PI, and PD

4.4. Statistical Analysis

5. Results

5.1. Respondent Profile

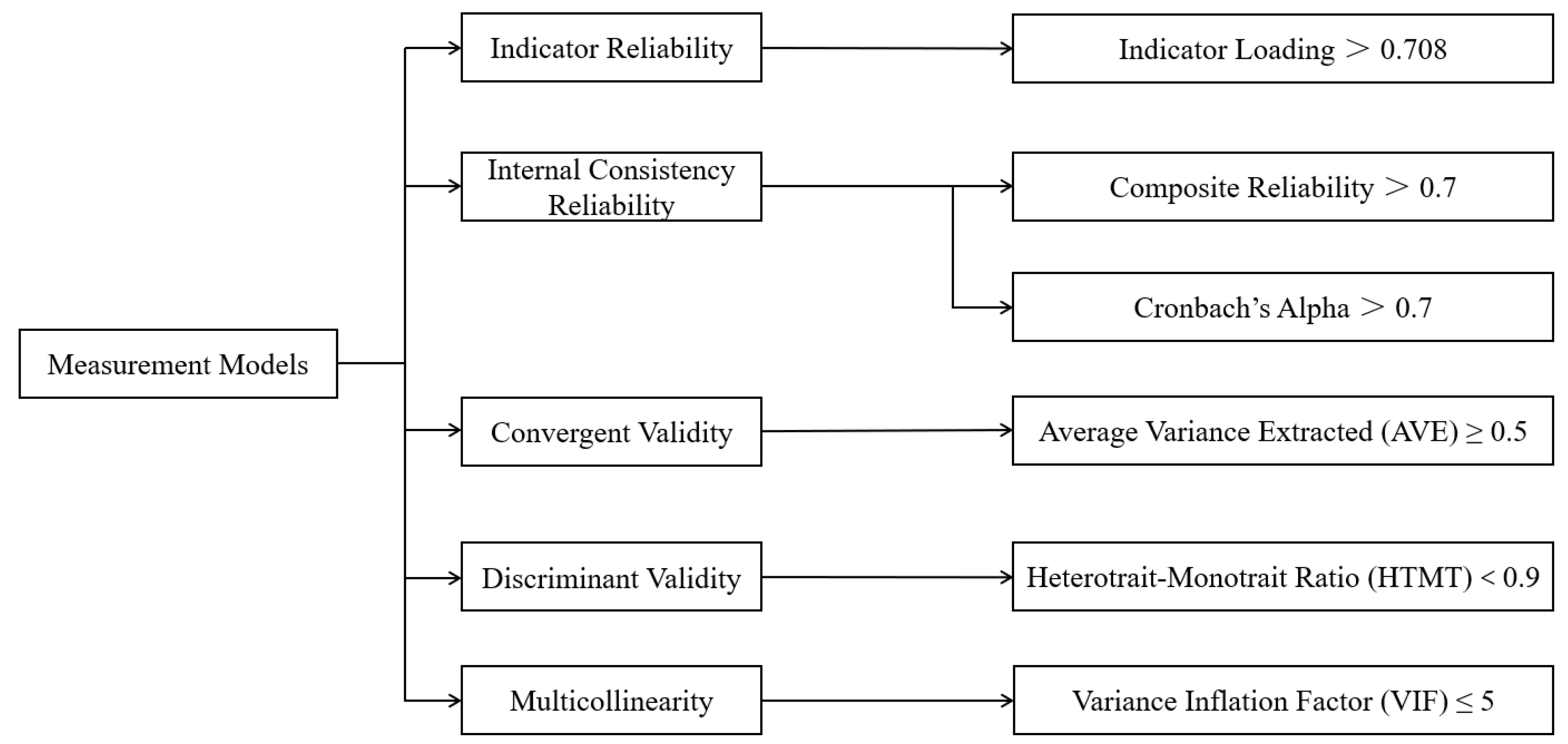

5.2. Evaluation of Measurement Models

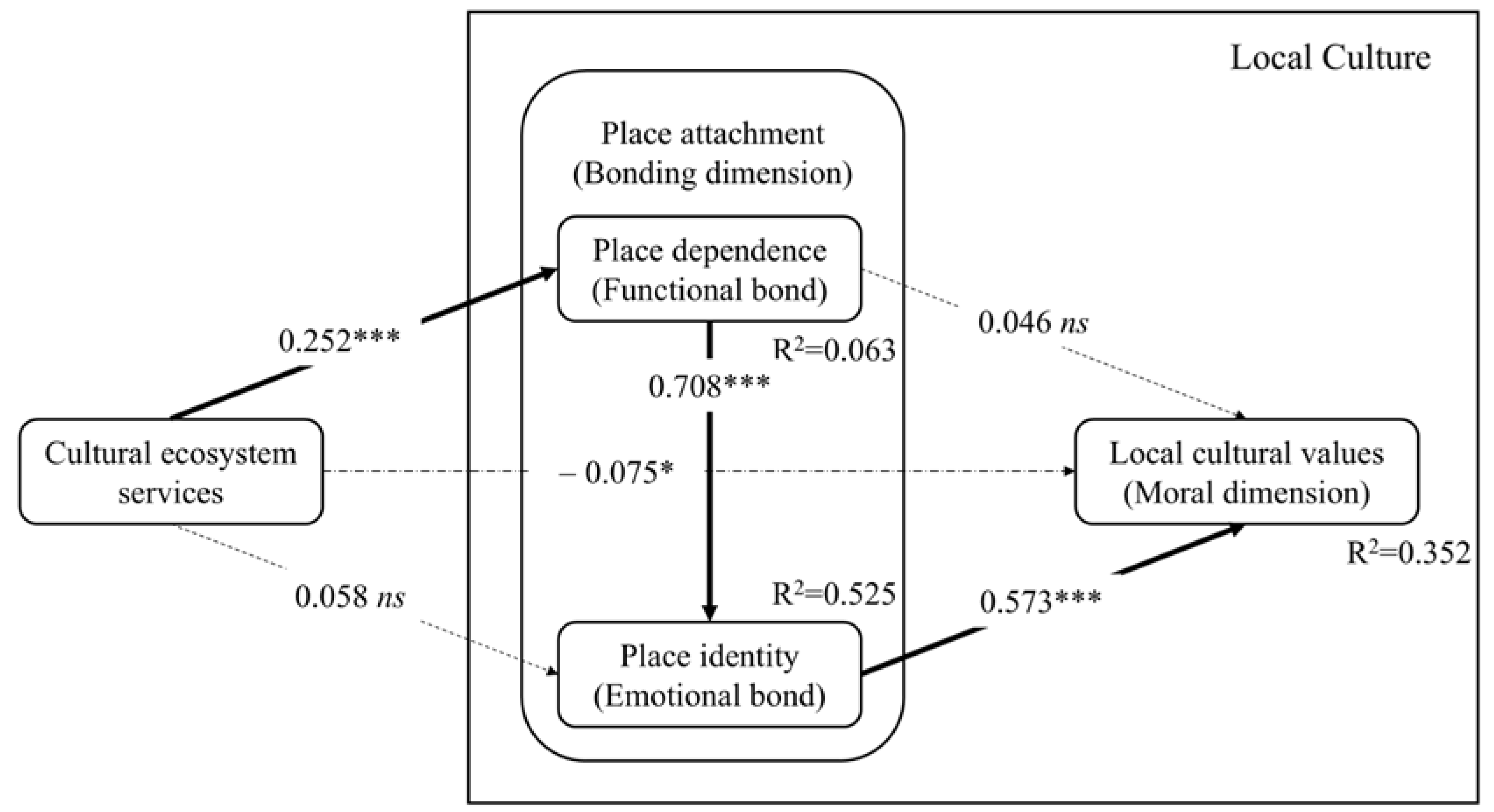

5.3. Evaluation of the Structural Model

5.4. Diversity in Subareas

6. Discussion

6.1. Effect of Cultural Ecosystem Services on Local Culture

6.2. Internal Processes of Local Culture: Relationships Among PD, PI, and LCV

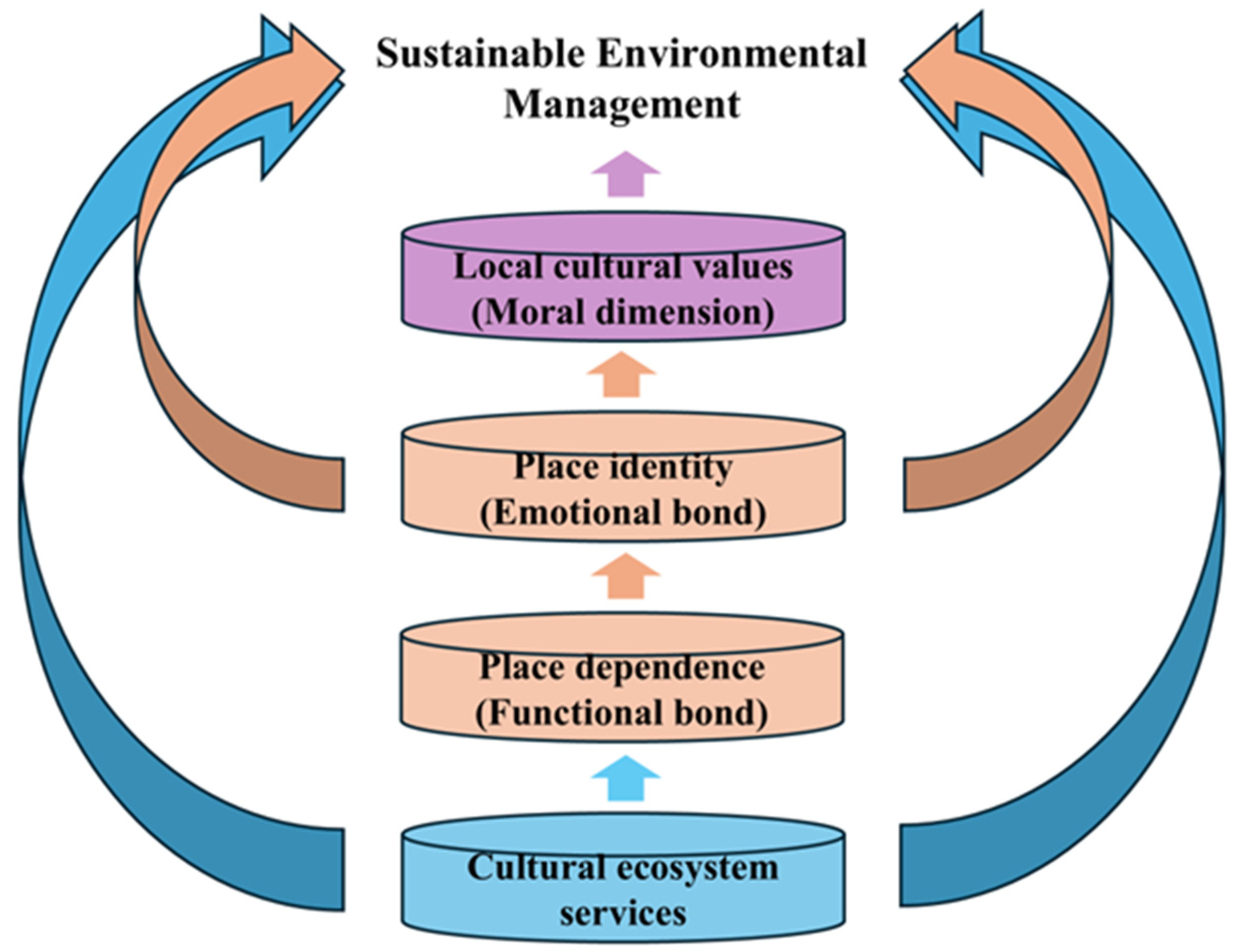

6.3. Overall Process of CES Influencing LCV

6.4. Linkage Between Cultural Ecosystem Services, Local Culture: Toward Sustainable Environmental Management

6.5. Practical Implications

6.6. Methodological Limitations and Future Directions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fish, R.; Church, A.; Winter, M. Conceptualising Cultural Ecosystem Services: A Novel Framework for Research and Critical Engagement. Ecosyst. Serv. 2016, 21, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirons, M.; Comberti, C.; Dunford, R. Valuing Cultural Ecosystem Services. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2016, 41, 545–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Synthesis; The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment series; Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, Ed.; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-1-59726-040-4. [Google Scholar]

- Satterfield, T.; Gregory, R.; Klain, S.; Roberts, M.; Chan, K.M. Culture, Intangibles and Metrics in Environmental Management. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 117, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer-Oatey, H.; Franklin, P. What Is Culture. A Compilation of Quotations. Glob. Core Concept. 2012, 1, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X.; Ding, Z.; Li, X.; Sun, J.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, R.; Wang, D.; Wang, Y.; Sun, W. How Cultural Values and Anticipated Guilt Matter in Chinese Residents’ Intention of Low Carbon Consuming Behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 246, 119069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, O.; Varaksina, N.; Hinterhuber, A. The Influence of Cultural Differences on Consumers’ Willingness to Pay More for Sustainable Fashion. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 442, 141024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, D. What Influences Urban Residents’ Intention to Sort Waste?: Introducing Taoist Cultural Values into TPB. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 371, 133540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roccas, S.; Sagiv, L. Personal Values and Behavior: Taking the Cultural Context into Account. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2010, 4, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. A Theory of Cultural Value Orientations: Explication and Applications. Comp. Sociol. 2006, 5, 137–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taras, V.; Rowney, J.; Steel, P. Half a Century of Measuring Culture: Review of Approaches, Challenges, and Limitations Based on the Analysis of 121 Instruments for Quantifying Culture. J. Int. Manag. 2009, 15, 357–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, T.; Fitzgerald, A.; Shwom, R. Environmental Values. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2005, 30, 335–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization). Records of the General Conference, 31st Session, Paris, 15 October to 3 November 2001, Volume 1: Resolutions. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000124687.page=68 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Matsumoto, D. Culture, Context, and Behavior. J. Pers. 2007, 75, 1285–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. Defining Place Attachment: A Tripartite Organizing Framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, E.; Tengö, M.; McPhearson, T.; Kremer, P. Cultural Ecosystem Services as a Gateway for Improving Urban Sustainability. Ecosyst. Serv. 2015, 12, 165–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torralba, M.; Lovrić, M.; Roux, J.-L.; Budniok, M.-A.; Mulier, A.-S.; Winkel, G.; Plieninger, T. Examining the Relevance of Cultural Ecosystem Services in Forest Management in Europe. Ecol. Soc. 2020, 25, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plieninger, T.; Bieling, C.; Fagerholm, N.; Byg, A.; Hartel, T.; Hurley, P.; López-Santiago, C.A.; Nagabhatla, N.; Oteros-Rozas, E.; Raymond, C.M.; et al. The Role of Cultural Ecosystem Services in Landscape Management and Planning. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 14, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Queiroz, L.S.; Rossi, S.; Calvet-Mir, L.; Ruiz-Mallén, I.; García-Betorz, S.; Salvà-Prat, J.; de Meireles, A.J.A. Neglected Ecosystem Services: Highlighting the Socio-Cultural Perception of Mangroves in Decision-Making Processes. Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 26, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvill, R.; Lindo, Z. The Inclusion of Stakeholders and Cultural Ecosystem Services in Land Management Trade-off Decisions Using an Ecosystem Services Approach. Landsc. Ecol. 2016, 31, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Sato, M. The Effect of Culture on Domestic Water Saving. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brundtland, G.H. Our Common Future World Commission on Environment and Development; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Nationen, V. (Ed.) Report of the World Summit on Sustainable Development: Johannesburg, South Africa, 26 August–4 September 2002; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-92-1-104521-5. [Google Scholar]

- Purvis, B.; Mao, Y.; Robinson, D. Three Pillars of Sustainability: In Search of Conceptual Origins. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurse, K. Culture as the Fourth Pillar of Sustainable Development. In Small States: Economic Review and Basic Statistics; Commonwealth: London, UK, 2006; pp. 28–40. ISBN 978-1-84859-887-4. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Transforming Our World The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://docs.un.org/en/A/RES/70/1. (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Soini, K.; Birkeland, I. Exploring the Scientific Discourse on Cultural Sustainability. Geoforum 2014, 51, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. The Hangzhou Declaration: Placing Culture at the Heart of Sustainable Development Policies; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2013; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sabatini, F. Culture as Fourth Pillar of Sustainable Development: Perspectives for Integration, Paradigms of Action. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, L.T.M.; Gasparatos, A.; Su, J.; Dam Lam, R.; Grant, E.I.; Fukushi, K. Linking the Nonmaterial Dimensions of Human-Nature Relations and Human Well-Being through Cultural Ecosystem Services. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabn8042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleasant, M.M.; Gray, S.A.; Lepczyk, C.; Fernandes, A.; Hunter, N.; Ford, D. Managing Cultural Ecosystem Services. Ecosyst. Serv. 2014, 8, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Q.; Shen, Z.; Liu, K.; Wei, X.; Yuan, C.; Gao, Y.; Liu, L. Understanding Residents’ Perspectives on Cultural Ecosystem Service Supply, Demand and Subjective Well-Being in Rapidly Urbanizing Landscapes: A Case Study of Peri-Urban Shanghai. Landsc. Ecol. 2024, 39, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.M.A.; Satterfield, T.; Goldstein, J. Rethinking Ecosystem Services to Better Address and Navigate Cultural Values. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 74, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Cai, L.; Bai, B.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, J. National Forest Park Visitors’ Connectedness to Nature and pro-Environmental Behavior: The Effects of Cultural Ecosystem Service, Place and Event Attachment. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2023, 42, 100621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masterson, V.A.; Stedman, R.C.; Enqvist, J.; Tengö, M.; Giusti, M.; Wahl, D.; Svedin, U. The Contribution of Sense of Place to Social-Ecological Systems Research: A Review and Research Agenda. Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidl, A. Cultural Ecosystem Services and Economic Development: World Heritage and Early Efforts at Tourism in Albania. Ecosyst. Serv. 2014, 10, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csurgó, B.; Smith, M.K. Cultural Heritage, Sense of Place and Tourism: An Analysis of Cultural Ecosystem Services in Rural Hungary. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baah, C.; Saleem, M.A.; Greenland, S.; Tenakwah, E.S.; Chakrabarty, D. Place Attachment and Residential Water Conservation: Application of an Extended Theory of Planned Behaviour in Australia’s Northern Territory. Environ. Dev. 2025, 55, 101203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariccio, S.; Petruccelli, I.; Ganucci Cancellieri, U.; Quintana, C.; Villagra, P.; Bonaiuto, M. Loving, Leaving, Living: Evacuation Site Place Attachment Predicts Natural Hazard Coping Behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 70, 101431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leahy, J.; Lyons, P. Place Attachment and Concern in Relation to Family Forest Landowner Behavior. Forests 2021, 12, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Kim, J. The Role of Place Attachment in Diminishing Compassion Fade in the Time Donation Context. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 70, 101462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Shen, G.Q.; Choi, S. The Place-Based Approach to Recycling Intention: Integrating Place Attachment into the Extended Theory of Planned Behavior. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 169, 105549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.H.; Kim, J.S.; Lee, C.-K.; Kim, N. Role of Place Attachment Dimensions in Tourists’ Decision-Making Process in Cittáslow. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2019, 11, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snider, A.G.; Luo, S.; Fusco, E. Predicting College Students’ Environmentally Responsible Behavior from Personality, Political Attitudes, and Place Attachment: A Synergistic Model. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2018, 8, 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, A.S.Y.; Ma, A.T.H.; Wong, G.K.L.; Lam, T.W.L.; Cheung, L.T.O. The Impacts of Place Attachment on Environmentally Responsible Behavioral Intention and Satisfaction of Chinese Nature-Based Tourists. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaykh-Baygloo, R. A Multifaceted Study of Place Attachment and Its Influences on Civic Involvement and Place Loyalty in Baharestan New Town, Iran. Cities 2020, 96, 102473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valizadeh, N.; Bijani, M.; Karimi, H.; Naeimi, A.; Hayati, D.; Azadi, H. The Effects of Farmers’ Place Attachment and Identity on Water Conservation Moral Norms and Intention. Water Res. 2020, 185, 116131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Io, M.-U. The Relationships Between Positive Emotions, Place Attachment, and Place Satisfaction in Casino Hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2018, 19, 167–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boley, B.B.; Strzelecka, M.; Yeager, E.P.; Ribeiro, M.A.; Aleshinloye, K.D.; Woosnam, K.M.; Mimbs, B.P. Measuring Place Attachment with the Abbreviated Place Attachment Scale (APAS). J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 74, 101577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Stewart, S.I. Sense of Place: An Elusive Concept That Is Finding a Home in Ecosystem Management. J. For. 1998, 96, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, H.-M.; Su, J.-Y.; Wang, C.-H.; Kiatsakared, P.; Chen, K.-Y. Place Attachment and Environmentally Responsible Behavior: The Mediating Role of Destination Psychological Ownership. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Shen, G.Q.; Choi, S. Pathways of Place Dependence and Place Identity Influencing Recycling in the Extended Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 81, 101795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinan Municipal Bureau of Statistics Communique of the Seventh National Census of Jinan City. Available online: https://jntj.jinan.gov.cn/art/2021/6/16/art_57208_4742898.html (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champ, P.A.; Boyle, K.J.; Brown, T.C. (Eds.) A Primer on Nonmarket Valuation; The Economics of Non-Market Goods and Resources; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2017; Volume 13, ISBN 978-94-007-7103-1. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatachalam, L. The Contingent Valuation Method: A Review. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2004, 24, 89–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, M.; Fazey, I.; Cooper, R.; Hyde, T.; Kenter, J.O. An Evaluation of Monetary and Non-Monetary Techniques for Assessing the Importance of Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services to People in Countries with Developing Economies. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 83, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinan Municipal Bureau of Water. Modern Water Network Plan of Jinan City (2021–2025). 2022. Available online: https://jnwater.jinan.gov.cn/art/2025/2/25/art_24727_4774766.html (accessed on 1 September 2025). (In Chinese)

- NBS Survey Office in Jinan, Jinan Municipal Bureau of Statistics. Jinan Statistical Yearbook 2024. Available online: http://jntj.jinan.gov.cn/art/2024/12/13/art_27523_4753171.html (accessed on 11 September 2025). (In Chinese)

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to Use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaiuto, M.; Bilotta, E.; Bonnes, M.; Ceccarelli, M.; Martorella, H.; Carrus, G. Local Identity and the Role of Individual Differences in the Use of Natural Resources: The Case of Water Consumption1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 38, 947–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Gursoy, D. Exploring the Relationship between Servicescape, Place Attachment, and Intention to Recommend Accommodations Marketed through Sharing Economy Platforms. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2020, 37, 429–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Song, H.; Chen, N.; Shang, W. Roles of Tourism Involvement and Place Attachment in Determining Residents’ Attitudes toward Industrial Heritage Tourism in a Resource-Exhausted City in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, L.; Weiss, J. Evidence on the Relationship between Place Attachment and Behavioral Intentions between 2010 and 2021: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hypothetical scenario | In order to maintain the springs’ gushing and protect historical artifacts, the Jinan government proposed two specific goals. First, to increase the days of groundwater levels higher than 28.15 m from 98 to 200 in years of normal precipitation (647.9 mm); Second, to repair and protect 166 damaged or insufficiently protected cultural landscapes of the springs. For achieving the above two goals, the Jinan government planned to conduct four projects during 2021–2025 including:

|

| Question | If you are willing to pay for the four projects to protect the cultural values of the spring environment in Jinan, how much are the highest amounts of Chinese Yuan you would want to pay during 2021–2025 at one time? (Please answer the total amount you want to pay including the actual payment that you are already paying for these projects.) |

| Payment card | A. 0 Yuan, B. 10 Yuan, C. 20 Yuan, D. 30 Yuan, E. 50 Yuan, F. 70 Yuan, G. 90 Yuan, H. 140 Yuan, I. 180 Yuan, J. 220 Yuan, K. Other: _____ Yuan |

| Latent Variable | Indicator | Measurement Item | Mean | S-W Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local cultural values | LCV1 | The spring environment is important for Jinan City. | 6.48 | 0.483 *** |

| LCV2 | The urban development of Jinan City needs to protect the spring environment. | 0.573 *** | ||

| LCV3 | “Protection of springs takes priority over all” is the most important principle in the development process of Jinan City. | 0.706 *** | ||

| LCV4 | All of Jinan’s development plans must ensure the maintenance of a good spring environment (for example, protection and repair of spring landscapes, and maintenance of spring gushing). | 0.67 *** | ||

| Place identity | PI1 | I am very attached to Jinan City. | 6.16 | 0.608 *** |

| PI2 | Jinan City is very special to me. | 0.811 *** | ||

| PI3 | I identify strongly with “I am proud to be from Jinan City.” | 0.76 *** | ||

| Place dependence | PD1 | Jinan City is the best place for me to live. | 5.25 | 0.882 *** |

| PD2 | No other place can compare to Jinan City for living. | 0.907 *** | ||

| PD3 | I would not substitute any other city for the activities I do in Jinan City. | 0.884 *** |

| Demographic Variable | Number | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Female | 221 | 54.7% | |

| Male | 169 | 41.8% | |

| Prefer not to answer | 14 | 3.5% | |

| Educational Level | |||

| Elementary school | 1 | 0.2% | |

| High school | 17 | 4.2% | |

| University/college | 313 | 77.5% | |

| Graduate school | 67 | 16.6% | |

| Prefer not to answer | 6 | 1.5% | |

| Age | |||

| 18–30 | 229 | 56.7% | |

| 31–40 | 127 | 31.4% | |

| 41–50 | 35 | 8.7% | |

| 51–60 | 12 | 3% | |

| ≥61 | 1 | 0.2% | |

| Residence Time (Years) | |||

| 1–3 | 60 | 14.9% | |

| 4–6 | 66 | 16.3% | |

| 7–10 | 55 | 13.6% | |

| 11–20 | 41 | 10.1% | |

| 21–30 | 100 | 24.8% | |

| 31–40 | 60 | 14.9% | |

| ≥41 | 22 | 5.4% | |

| Monthly Income (CNY) | |||

| 0–4000 | 88 | 21.8% | |

| 4001–8000 | 189 | 46.8% | |

| 8001–12,000 | 86 | 21.3% | |

| ≥12,001 | 40 | 9.9% | |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 | 0.2% | |

| Latent Variables | Indicator | Indicator Loading | p-Value | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted | Variance Inflation Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Place identity (PI) | PI1 | 0.858 | 0.000 | 0.827 | 0.897 | 0.743 | 1.951 |

| PI2 | 0.849 | 0.000 | 1.760 | ||||

| PI3 | 0.879 | 0.000 | 1.985 | ||||

| Place dependence (PD) | PD1 | 0.931 | 0.000 | 0.870 | 0.921 | 0.795 | 3.169 |

| PD2 | 0.862 | 0.000 | 2.145 | ||||

| PD3 | 0.881 | 0.000 | 2.322 | ||||

| Local Cultural Values (LCV) | LCV1 | 0.849 | 0.000 | 0.877 | 0.915 | 0.730 | 2.510 |

| LCV2 | 0.897 | 0.000 | 3.102 | ||||

| LCV3 | 0.820 | 0.000 | 2.113 | ||||

| LCV4 | 0.850 | 0.000 | 2.425 |

| Variable | CES | LCV | PD | PI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CES | ||||

| LCV | 0.078 | |||

| PD | 0.272 | 0.503 | ||

| PI | 0.258 | 0.688 | 0.846 |

| Indicators | Central Area | Marginal Area | Median Difference | Mann–Whitney U (p Value) | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CES | 81.9 | 69.2 | 0 | 0.496 | 0.143 |

| PI | 6.2 | 6.0 | 0.333 | 0.018 | 0.201 |

| PI1 | 6.5 | 6.4 | 0 | 0.123 | 0.121 |

| PI2 | 6.0 | 5.8 | 0 | 0.056 | 0.168 |

| PI3 | 6.1 | 5.9 | 1 | 0.104 | 0.216 |

| PD | 5.4 | 5.1 | 0.167 | 0.031 | 0.217 |

| PD1 | 5.5 | 5.1 | 1 | 0.013 | 0.255 |

| PD2 | 5.4 | 5.1 | 0 | 0.039 | 0.179 |

| PD3 | 5.3 | 5.0 | 1 | 0.186 | 0.151 |

| LCV | 6.5 | 6.4 | 0 | 0.212 | 0.157 |

| LCV1 | 6.7 | 6.6 | 0 | 0.016 | 0.172 |

| LCV2 | 6.6 | 6.5 | 0 | 0.293 | 0.107 |

| LCV3 | 6.4 | 6.2 | 0 | 0.221 | 0.158 |

| LCV4 | 6.4 | 6.4 | 0 | 0.207 | 0.09 |

| Path | Difference | 1-Tailed p Value | 2-Tailed p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CES ⇒ LCV | 0.021 | 0.396 | 0.396 |

| CES ⇒ PD | −0.088 | 0.835 | 0.165 |

| CES ⇒ PI | −0.099 | 0.883 | 0.117 |

| PD ⇒ LCV | 0.019 | 0.451 | 0.451 |

| PI ⇒ LCV | −0.078 | 0.683 | 0.317 |

| PI ⇒ PD | −0.028 | 0.325 | 0.325 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, G.; Sato, M. The Linkage Between Cultural Ecosystem Services and Local Culture. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9420. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219420

Yang G, Sato M. The Linkage Between Cultural Ecosystem Services and Local Culture. Sustainability. 2025; 17(21):9420. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219420

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Guolunan, and Masahiro Sato. 2025. "The Linkage Between Cultural Ecosystem Services and Local Culture" Sustainability 17, no. 21: 9420. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219420

APA StyleYang, G., & Sato, M. (2025). The Linkage Between Cultural Ecosystem Services and Local Culture. Sustainability, 17(21), 9420. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219420