Abstract

This research investigates the factors influencing organizational participation in Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), specifically examining the role of Chief Executive Officer (CEO) attributes and the moderating influence of stakeholder pressure. Utilizing fuzzy-set Quantitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) on a dataset of 220 Chinese firms, this study identifies that high SDG engagement arises from multiple, equally effective configurations of CEO characteristics (age, education, experience, CEOs in family and non-family firms, digital and financial literacy) and shareholder pressure as a moderator. Our research shows three distinct configurational paths towards participation in SDGs. Young–Skilled–Pressured (Path A): Younger, highly educated CEOs with strong financial and digital literacy, operating under significant stakeholder pressure, are more likely to participate in SDGs. Older–Experienced–Family–Pressured (Path B): Older, experienced family CEOs, supported by at least one form of literacy (financial or digital), and facing strong stakeholder pressure, tend to participate in SDGs. Professionalized Non-Family (Path C): Highly educated CEOs in non-family firms with robust financial and digital literacy, who are also under strong stakeholder pressure as moderators, participate in SDGs. Crucially, strong pressure from external stakeholders is found to be a near-constant prerequisite (quasi-necessary condition) for achieving high SDG participation. This study contributes to Upper Echelons Theory by demonstrating the conjunctural nature of CEO attributes in impacting strategic outcomes. It also reinforces Stakeholder Pressure Theory by confirming its critical and moderating role in driving sustainable practices. Practically, the findings suggest that boards should strategically design leadership teams and foster robust stakeholder engagement, as this external pressure is nearly always required to enhance SDG participation.

Keywords:

demographics; CEO; corporate governance; environment; CSR; SDG; fsQCA; upper echelons theory 1. Introduction

The urgent need for a global shift towards sustainable development has become increasingly prominent in the 21st century. Recognizing environmental challenges and societal disbalances, in 2015, the United Nations established the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), emphasizing 17 interconnected objectives designed to foster a sustainable future [1]. The objective of establishing these goals is to address critical global issues such as poverty, inequality, environmental degradation, and climate change by balancing economic growth with social inclusion and environmental protection. It is pertinent to note that the implementation of SDGs is not merely a moral obligation but a pragmatic necessity for protecting global equity and fostering collective efforts among businesses, governments, and civil societies. Given its critical nature and strategic importance, sustainability has thus become a relevant discourse in the current scholarship. Organizations are increasingly under pressure to align their strategies and operations with these global sustainability objectives, a complex endeavor that requires significant strategic leadership [2,3]. This study specifically investigates how different attributes of CEOs can influence an organization’s participation in SDGs, while also considering the crucial role of external pressures.

Earlier investigations have extensively explored various factors influencing corporate social responsibility (CSR) and sustainability initiatives, often focusing on individual CEO characteristics or external pressures in isolation. We concur that the relationship between CSR and SDGs is crucial, as they are intrinsically linked concepts. Our research reflects this by grounding the positive influence of CEO attributes, such as higher education, in their documented propensity to engage in CSR activities that strictly align with SDGs. Therefore, CSR serves as a foundational element where CEO traits are shown to foster the sustainable mindset necessary for eventual high SDG participation [4]. For instance, numerous studies find CEO’s academic qualifications highly relevant in terms of their participation in sustainable development, equipping them with superior skills, knowledge, and exposure to refined global practices essential for sustainable adaptation [5,6,7]. Educationally qualified CEOs demonstrate a higher propensity to engage in CSR activities that align with SDGs [7,8]. Likewise, the youthfulness of managers is often linked to environmentally friendly behavior, better awareness, and proactive strategies that collectively foster sustainable practices, as younger managers tend to be more open to innovative sustainable approaches and more enthusiastic about CSR [9,10,11].

Apart from education and youthfulness, the experience of managers plays a fundamental role in influencing their decision-making and leadership effectiveness, which provides practical knowledge on how to handle uncertain situations and leverage prior knowledge for strategic planning and innovation [12,13]. Older and experienced managers often adopt a broader perspective, prioritize long-term success through socially responsible practices, and provide stable leadership crucial for long-term SDG attainment [14]. The distinction between CEOs in family and non-family firms has also been examined, with arguments suggesting that family firms often prioritize socioemotional wealth and legacy preservation, leading to deeper CSR engagement and a commitment to long-term sustainability that drives SDG practices beyond mere regulation [15,16]. Lastly, financial and digital literacy among CEOs has been emphasized as fundamental for shaping a firm’s environmental and social policies [17,18], enabling informed decisions on sustainable investments and leveraging advanced technologies to optimize operations and advance various SDGs.

In parallel, stakeholder pressure has been identified as a critical external driver. This refers to the influence exerted by various groups—such as regulators, customers, communities, suppliers, and investors—on firms to engage in sustainable and environmentally friendly practices [19]. Firms subject to stronger stakeholder pressure are highly influenced towards social activities, acting as a catalyst for embedding sustainable practices, imposing compliance requirements, fostering innovation, and enhancing corporate legitimacy (for instance, see [20,21]).

Despite this rich body of work, a significant gap remains in understanding the configurational interplay of these factors. Most prior research tends to examine the net effects of individual CEO attributes or the general impact of stakeholder pressure in isolation, rather than exploring how specific combinations of CEO characteristics in conjunction with external stakeholder demands lead to high organizational participation in SDGs. This linear, variable-centric approach often fails to consider the complex and multifaceted reality of organizational decision-making, where multiple conditions may combine to produce a particular outcome.

Addressing this gap is crucial because the participation of SDGs is shaped by a constellation of attributes rather than the result of a single “silver bullet” factor. Therefore, participation in SDGs often emerges from a complex interplay of internal leadership dynamics and external contextual forces. So, by adopting a configurational approach—fuzzy-set Quantitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA)—this study moves beyond examining whether attributes “individually or exclusively” influence SDG participation, to understanding how they “complement” each other to drive such outcomes. This allows for the identification of multiple, equally effective pathways to high SDG engagement, providing a more nuanced and realistic picture for both research and practice.

This research provides a nuanced, configurational perspective on the drivers of high organizational participation in SDGs. Chiefly, this study offers two major contributions:

Configurational Upper Echelons Account (UET): This research significantly advances Upper Echelons Theory (UET) by demonstrating the fundamentally conjunctural nature of CEO attributes in achieving complex strategic outcomes like SDG implementation. The study moves beyond traditional linear, variable-oriented analyses by employing fsQCA to understand how CEO characteristics (age, education, experience, CEOs in family and non-family firms, digital and financial literacy) interact not in isolation, but in specific combinations. The findings establish that high SDG participation is not the result of a single “silver bullet” factor, but rather emerges from multiple, equally effective configurations of CEO attributes combined with context. Robustness checks confirm conjunctural causation, indicating that removing any single core condition significantly reduces consistency, thus highlighting that effectiveness is contingent upon the holistic profile of the CEO within their specific context.

Stakeholder Pressure as a Quasi-Necessary Condition: The research provides robust empirical support for Stakeholder Pressure Theory by confirming that stakeholder pressure plays a unique and pervasive role in driving sustainable practices. This study empirically confirms that stakeholder pressure is a quasi-necessary condition for high SDG participation. This finding is supported by a high consistency score of 0.90. A consistency above 0.90 suggests that the condition is almost always present when the desired outcome (high SDG participation) occurs.

This critical role deepens the theory by demonstrating that stakeholder pressure acts as the bridging component that is essential to transform or strengthen the positive relationships between CEOs’ internal attributes and subsequent sustainable practices. Stakeholder pressure is a core condition in all three sufficient configurations (Paths A, B, and C) identified by the fsQCA analysis, underscoring its pivotal role in the dynamic interplay between internal leadership and external demands.

By identifying specific successful configurations, the current study enlightens organizations with practical and actionable insights for the selection and development of CEOs in the presence of strategic stakeholders’ engagement, which ultimately improves SDG participation. In addition, our findings offer valuable guidance for policymakers by providing an in-depth analysis of how internal leadership capabilities, external pressure mechanisms, and SDG implementation interact. On the whole, our study provides a comprehensive understanding of how characteristics of CEOs, in the presence of stakeholder pressure, reshape the firm’s commitment to sustainable activities, contributing to the ambitious global agenda. While this study is conducted in the Chinese context, the methodology and theoretical foundation provide a robust framework that enlightens readers on the complex path towards corporate sustainability across diverse contexts.

The methodology and configurational logic offer a robust framework applicable wherever Upper Echelons Theory (UET) and Stakeholder Pressure Theory interact, such as in highly regulated emerging markets or major economies like Europe and the USA. These contexts, which face significant institutional and competitive pressure to meet SDG targets, would benefit from testing how specific combinations of professional leadership (Path C) or enduring family legacies (Path B) are activated by external demands. This allows researchers globally to move beyond linear analyses when studying complex strategic outcomes like sustainability.

Addressing the Gap

Earlier variable-centric studies have established that individual CEO characteristics—such as higher education and youthfulness—are positively linked to CSR and sustainability engagement. Similarly, prior research supports the positive effects of older/experienced CEOs and the long-term orientation of CEOs in family firms on sustainable practices. However, this study challenges the sufficiency of these isolated variables. While these linear approaches provide valuable baseline findings, our configurational analysis reveals that no single CEO attribute (except stakeholder pressure) is strictly necessary to achieve high SDG participation [22]. Instead, high engagement arises from multiple, equally effective configurations [23,24]. For instance, merely being an experienced CEO is not sufficient alone; rather, the positive effect of older/experienced CEOs is only effective when coupled with family control, strong stakeholder pressure, and at least one form of literacy (Path B). This complex interplay moves beyond the net effects typically found in the conventional literature, providing a more realistic, configurational account of UET and Stakeholder Theory in practice.

2. Theoretical Background

To understand the influence of CEO attributes on organizational participation in SDGs, encompassing the critical role of external stakeholders’ pressure, this research draws upon two foundational theories: Upper Echelons Theory and Stakeholder Pressure Theory.

2.1. Upper Echelons Theory (UET)

Upper Echelons Theory, mostly dubbed ‘UET’, posits that the organizational performance, strategic choices, and outcomes, to a significant extent, are driven by the values and cognitive bases of a firm’s top managers. Pioneered by Hambrick and Mason [25], this theory argues that executives’ observable characteristics—such as education, age, functional experience, and socioeconomic background—influence their approach towards different strategic issues, subsequently affecting their decision-making process. In fact, the personal attributes affect what top managers notice, as well as how they interpret information and make decisions based on their perceptions (see [26,27,28]).

Therefore, in the context of sustainable development, UET provides a strong foundation for investigating CEOs’ personal attributes because they directly influence their approach to environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues and, consequently, the firm’s engagement with SDGs (see [29,30,31]). Hence, the current study using UET emphasizes how various attributes of CEOs impact a firm’s engagement with SDGs.

- Education is often attributed to superior skills, knowledge, and exposure to refined global practices, which are essential for adopting sustainable practices [32]. Firms with highly educated CEOs are better equipped with skills and knowledge that are fundamental for addressing challenges and complexities associated with sustainable practices [33]. The body of previous research suggests that the higher education of CEOs is directly related to a firm’s CSR activities (see [34]), which strictly align with SDGs. The experience of managers significantly contributes to their level of awareness of value orientation, social responsibility, and professional ability [35].

- Youthfulness is associated in the literature with eco-friendly behavior, better awareness, and proactive strategies that align with sustainable development. In fact, younger managers often indulge in more innovative sustainable practices due to their enthusiasm and motivation for social activities [36]. They also possess better physical and mental stamina, which translates to better information-processing abilities that empower them to implement sustainability-related strategies in more effective ways [36].

- Experience and age also play a fundamental role in decision-making and leadership effectiveness. Over the years, functional managers have developed such valuable practical knowledge, which enables them to handle uncertain situations more efficiently by leveraging prior knowledge for strategic planning and innovation [37]. Older managers, with their broader perspective and wealth of experience, demonstrate a more ethical attitude, valuing long-term success over short-term gains by adopting sustainable practices and socially responsible behavior [38]. They are also more likely to integrate sustainable practices into the firm’s core values, providing stable leadership fundamental for long-term SDG attainment.

- This study also considers the distinction between CEOs in family and non-family firms. Family firms are often more concerned about their reputation and legacy, henceforth, prioritizing socioemotional wealth by engaging in CSR activities and showing their commitment to long-term sustainability (see [39]). Even though non-family CEOs also engage in sustainable activities, this impact is stronger in family firms due to their long-term orientation and commitment to legacy [40].

- Lastly, the financial and digital literacy of managers is emphasized in the context of sustainable practices as it plays a fundamental role in shaping a firm’s social and environmental policies. Empirically, it is proven that the financial literacy of a manager equips firms with knowledge that is useful to assess the financial viability and long-term impact of sustainable development projects and motivates managers to make ethical investments [41]. Meanwhile, digitally literate managers are able to harness advanced technologies that are crucial for optimizing operations, reducing waste, and advancing various SDGs [42]. These literacies collectively enhance CEOs’ abilities, improving their decision-making process, specifically in terms of SDG implementations.

UET, in the context of our study, provides a robust framework for analyzing different characteristics of the top management and their role in shaping a firm’s commitment and participation in activities that are in accordance with SDGs.

2.2. Stakeholder Theory

In the context of organizational sustainability, stakeholders’ pressure is another key element that plays a pivotal role in the implementation of SDGs. Stakeholder Theory asserts that organizations are not isolated entities; rather, they function within a network of diverse actors who exert significant influence over the firm’s operations and strategic decisions [43]. Stakeholders’ pressure refers to the external influence of various groups—including customers, regulators, institutional investors, and social activists—on a firm’s decision to invest in sustainable and environmentally friendly projects [44]. This theory highlights that firms must respond to the demands of these stakeholders to sustain their legitimacy, resources, and social acceptance.

So, in any firm, sustainability is driven by external pressure, prompting firms to align organizational strategies and operations with social, environmental, and community principles [45]. The primary objective of such pressure is to bridge the gap between broader sustainability objectives and organizational economic goals. This external pressure might be exerted in different forms. For instance, institutional investors prioritize investing in firms concerned with environmental and social goals, while consumer activism influences firms’ sustainable development decisions due to heightened awareness of CSR and sustainability (see [46]).

A rich body of literature affirms that the firms subjected to strong external pressure are more likely to engage in social activities (for instance, [47,48,49]). Empirically, stakeholders’ pressure is often seen as a catalyst for a firm’s sustainable development. Therefore, regulatory stakeholders—including international organizations and governments—impose strict compliance requirements and industry standards that mitigate environmental footprints and enhance social practices.

This positive pressure acts as a catalyst for embedding sustainable practices into the organization’s culture. Regulatory stakeholders, including international organizations and governments, impose compliance requirements and industry standards that reduce environmental footprints and augment social practices. This pressure can reshape firms’ priorities, transforming sustainability from merely a compliance obligation into a competitive advantage. Furthermore, stakeholder pressure fosters innovation and collaboration, enabling firms to co-create solutions to environmental challenges, such as green technologies [19].

Crucially, in this study, Stakeholder Pressure Theory is employed to understand its moderating role. The research hypothesizes that the positive relationships between various CEO attributes (young and educated, experienced and aged, CEOs in family/non-family firms, and financially/digitally literate) and SDG implementation will be strengthened in the presence of stakeholder pressure. The findings confirm that stakeholder pressure is a quasi-necessary condition for high SDG participation, with a high consistency of 0.90. This underscores that while CEO attributes are important, the external push from stakeholders is almost always present for organizations to achieve significant SDG engagement.

2.3. UET and Stakeholder Under Configuration Approach

By integrating these two theories, this study provides a comprehensive understanding of how internal leadership characteristics, when combined with external stakeholder demands, configuratively drive a firm’s commitment to and participation in the ambitious global agenda of the SDGs.

Integrating UET and Stakeholder Theory: A Configurational Approach

To provide a comprehensive understanding of how internal leadership characteristics and external demands collectively drive organizational commitment to SDGs, this research integrates UET and Stakeholder Pressure Theory through a configurational lens.

Prior investigations into corporate sustainability have typically employed a linear, variable-centric approach, examining the net effects of individual CEO attributes (UET) or the general impact of stakeholder pressure in isolation. This approach, however, often fails to account for the complex and multifaceted reality of organizational decision-making. The reality is that participation in SDGs is shaped by a “constellation of attributes” and emerges from a complex interplay between internal leadership dynamics and external contextual forces.

By adopting a configurational approach—specifically, fsQCA—this study overcomes the limitations of linear analysis. This methodology allows the research to move beyond understanding whether CEO attributes and stakeholder pressure “individually or exclusively” influence SDG participation, toward understanding how they “complement” each other to drive these outcomes.

This theoretical integration posits two critical concepts:

- The Conjunctural Nature of UET: The impact of CEO attributes on strategic outcomes like SDG implementation is not isolated; it is conjunctural. UET is extended by recognizing that observable CEO characteristics (e.g., age, education, literacy) operate effectively only in specific combinations with other attributes and contextual factors.

- The Bridging Role of Stakeholder Pressure: Stakeholder pressure, derived from Stakeholder Theory, is hypothesized to act as a crucial moderating force. This research hypothesizes that the positive relationships between various CEO attributes and SDG implementation are strengthened in the presence of external demands. Empirical evidence further establishes stakeholder pressure as a quasi-necessary condition for high SDG participation.

In essence, this integrated framework proposes that high SDG participation is achieved via multiple, equally effective pathways (configurations) where specific bundles of CEO traits—representing internal capabilities and cognitive bases—must align with the persistent external mandate provided by stakeholder pressure.

3. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

3.1. Younger and Educated CEO and SDGs

Keeping in view the environmental challenges, the UN in 2015 established the SDGs with the aim of a sustainable future [1]. Seventeen interconnected goals are emphasized, which aim to tackle critical challenges such as inequality, poverty, environmental degradation, and climate change. The basic purpose of setting these goals is to balance economic growth with social inclusion and environmental protection [50]. Fostering collective efforts among businesses, governments, and civil societies, the SDGs provide a conducive framework that encompasses economic and sustainable growth collectively [51]. It is pertinent to note that the implementation of SDGs is not merely a moral obligation but a pragmatic necessity to protect global equity.

There is enough evidence that portrays the positive role of education in sustainable performance [52]. Higher academic qualifications enhance the abilities of CEOs, which influence their participation in the sustainable development of a firm [53]. Essentially, education is attributed to superior skills, knowledge, and exposure to refined global practices that are essential for sustainable practices’ adaptation. Therefore, managers with higher education are more skillful and are in a strong position to address challenges and complexities that are associated with sustainable practices [50].

Emerging research from the field of sustainability suggests that youthfulness, along with education, positively contributes to sustainable practices. In this regard, the study of Dimitrova, et al. [54] suggests that young managers, with environmentally friendly behavior, have better awareness, which equips them with proactive strategies that foster sustainable practices. Moreover, Hong, et al. [55] in their study revealed that the Chinese youth actively participate in sustainable consumption practices, inspired by societal norms and consciousness. The findings are substantive in arguing that the combination of youth and a high education level fosters a sustainable mindset. For instance, García-Sánchez and Martínez-Ferrero [56] in their study found educationally qualified CEOs more prone towards CSR activities. On the other hand, Huang [57] in his study revealed that the younger managers in firms are more open to innovative sustainable practices.

From the empirical findings, the current study demonstrates that youthfulness and managerial education collectively encourage managers to adopt sustainable practices. CEOs who are educated and young are more likely to engage in CSR activities that strictly align with SDGs [55,58]. There are several studies that have identified the role of age and education in influencing the sustainability mindset. For instance, Ma, et al. [59] in their study investigating the behavior of top management towards CSR revealed that managers with academic backgrounds perceived CSR as an opportunity rather than a threat. Yang and Qi [60] argue that the academic experience of managers enhances their awareness of value orientation, social responsibility, professional ability, and network resources. Zhou, Chen, and Chen [33] also concluded that educated CEOs perform well in incorporating SDGs into firms’ goals. Similarly, age is also considered a contributor to the purpose felt toward achieving SDGs [61]. Young people are more enthusiastic and motivated about CSR activities [62]. Moreover, young top managers have better physical and mental stamina; therefore, they have better information-processing abilities [63]. Hence, young managers are open to adopting and implementing sustainability-related strategies to attain SDGs without hesitation. Therefore, from the empirical evidence, we suggest that

H1:

Organizations led by younger and well-educated CEOs demonstrate high motivation to participate in SDGs.

3.2. Experienced and Aged CEOs and SDGs

In any firm, the experience of managers plays a fundamental role in decision-making and leadership effectiveness. An experienced manager is full of valuable practical knowledge acquired from years of practice [25]. The literature provide insight on the role of professional managers in handling uncertain situations more efficiently based on their informed decision-making [64]. Moreover, with experience, the managers have a tendency to leverage prior knowledge to enhance their capacity for strategic planning and innovation [31,65]. Thus, the experience of the manager is a pivotal factor for attaining effectiveness and sustainability. Similarly, the age of the manager is also an important factor for sustainable practices. Age shapes the leadership style and decision-making approach of managers. Older managers have a broader perspective and a wealth of experience that helps them in achieving long-term organizational goals [66].

Employing a configurational model, this study views managerial age and experience as critical determinants of SDGs’ achievement. Aged CEOs with experience are more often engaged in sustainable practices based upon their knowledge and long-term perspective of business success [67]. With the passage of time, the CEOs develop a deep understanding of the market’s dynamics, societal expectations, and regulatory obligations; hence, they appreciate the significance of environmental and social values. Moreover, with the rapidly changing world, where firms are under immense pressure to go green and follow the SDGs, seasoned leadership tends to have a more ethical attitude, prioritizing the long-term success over short-term gains by adopting socially responsible and sustainable business practices [68,69]. In fact, their capacity to foresee upcoming opportunities and challenges spurs on their intentions to pursue such strategies that align with the requirements of sustainable development [64].

Furthermore, a top management with aged CEOs tends to have a more stable leadership style, which often helps in the integration of sustainable practices into the core values of the firm. Therefore, stability in terms of a sustainable leadership style is fundamental to adopting practices that support the attainment of SDGs in the long run [70]. It is pertinent to note that the increasing pressure of stakeholders to adopt sustainable development practices requires extensive experience; hence, the top management needs better-equipped CEOs who tend to balance the needs of society with the needs of the organization. In a recent study, Ingason and Eskerod [71] revealed that experienced managers with professional backgrounds have the capabilities to navigate environmental concerns, such that they handle complexities, opportunities, and economic concerns by assuming responsibility for sustainable development. Thus, aged and experienced managers, through their accumulated wisdom, make informed decisions in line with the SDGs, keeping in view the interests of shareholders, societal goals, and long-term benefits of CSR [72]. Therefore, based on the empirical evidence, we hypothesize that

H2:

Organizations led by both experienced and senior/aged CEOs have high motivation to participate in SDGs.

3.3. CEOs in Family and Non-Family Firms and SDGs

There is a lack of consensus on whether the CEOs in family businesses are different from non-family CEOs in the context of CSR. However, the empirical evidence is clear that family businesses do have certain differences compared to other businesses, specifically borne from the influence of the family on the objectives, goals, and vision of the company [73]. The scholars argue that such differences are reflected in the behaviors of CEOs, given that firms with CEOs perceive social behavior as a strength, supporting them to attain a better reputation within society. Essentially, firms in the last few years have emphasized sustainable development based on the assumption that companies are accountable for their social actions [74]. Indeed, societal groups attribute high values to organizations that actively report socially responsible activities and principles [75]. Therefore, organizations spend a great deal of time, money, and effort on sustainable development practices.

Family firms often pursue environmental and social sustainability with efforts that go beyond regulation [76]. Firms with CEOs in the family not only strive for profit maximization but they also make greater efforts to generate and build a strong relationship with reference communities to preserve the family reputation [77]. Although few studies have identified values that define the way of viewing business with reference to family firms, the evidence is sufficiently substantial to argue that family firms, with CEOs in the family, are more likely to engage in SDG practices [78]. As a starting point, the study of Block and Wagner [79] signifies the behavior of the family CEO in regard to CSR. Their findings suggest that family firms pursue social activities more rigorously than non-family firms.

A recent systematic literature review by Mariani, et al. [80] further strengthens our argument that CEOs in the family are comparatively more socially responsible than CEOs in non-family firms. Meanwhile, the study of García-Sánchez, et al. [81] using an international sample of 956 listed firms revealed that family-run businesses are more ethical and have higher levels of CSR activities in their organizations. While investigating a US sample, Abeysekera and Fernando [82] argued that family firms are more loyal and responsible to the shareholders compared to non-family firms. Elsewhere, Madden, McMillan, and Harris [39], drawing on socioemotional selectivity theory, suggested that the managers of family firms are more engaged in terms of CSR activities, and they invest more in CSR in comparison to non-family managers. In a similar context, Rubino, et al. [83] examined the board of directors and the ownership structure of Italian firms, and their findings suggested that CEOs in family firms have a stronger nexus with sustainable activities compared to non-family top management.

Several different studies, including the above-cited studies, show that family firms are more influenced towards social activities; however, this does not mean that non-family firms’ CEOs do not participate in social activities. In fact, sustainability development within firms is now an obligation. Yet, the relationship between CEOs in family firms and sustainability is stronger compared to non-family firms’ CEOs because CEOs in family firms prioritize sustainable practices due to the company’s long-term orientation and their commitment to preserving the family legacy [58,82]. So, based on the empirical evidence, we hypothesize that

H3:

Organizations led by CEOs in the family have higher motivation to be engaged in SDGs as compared to firms with CEOs not in the family.

3.4. Digital and Financial Literacy and SDGs

In the past few decades, financial literacy’s definition has evolved from what once was considered ‘understanding basic numbers’ to the ‘management of personal finances and knowledge of market securities, investment, future planning, risk management, and diversification’ [84]. After the great financial crisis, the need for financial literacy has further increased worldwide. In fact, individually and institutionally, a lack of adequate financial literacy results in a poor financial performance. Klapper, et al. [85] argue that financial literacy, in both developed and developing economies, acts as a buffer in financial crisis and crisis impact. As a result, more schools, financial institutions, governments, and organizations have promoted financial literacy based on it being a core competency.

Over time, financial literacy has become a fundamental approach to sustainable investment and economic stabilization. The advancement of globalization, with markets escalating, has resulted in economic integration deepening; thus, the capacity for decision-makers across the globe to make sensible financial choices has never been so important. In this regard, Lusardi and Mitchell [84] termed financial literacy a crucial factor in shaping the economic competencies that, in realistic scenarios, aid in the realistic application of knowledge. In fact, they suggest that financial literacy acts as a basic component that provides insight into the complexity of the functioning of society. As such, the current study emphasizes the role of financial literacy in sustainable investment decisions and its implications for a sustainable environment.

Sustainable investment, its impact, and its importance have become a burning topic for both academics and practitioners. In Europe alone, half of the inflow of European investment products is of sustainable financial products [86]. The role of financial literacy in encouraging sustainable investment practices is quite prominent. Financial literacy equips individuals with greater financial knowledge, which prompts the long-term benefits of sustainable investment. In this regard, [84] argues that financial literacy enables individuals to effectively measure the risks and rewards associated with their investment projects. This capability, in fact, leads investors to hold sustainable investment preferences. Fatoki [87], in this regard, argues that financial literacy, along with financial knowledge, cultivates the ethical awareness of investors, and thus investors with higher financial literacy are more likely to invest in socially responsible projects. The study of Døskeland and Pedersen [88] also revealed similar findings, stating that individuals with higher financial literacy demonstrated stronger inclinations towards sustainable projects.

Similar to financial literacy, the current study, in the context of the configurational model, argues that financial literacy, along with digital literacy, can influence CEOs to prioritize SDGs. Digitalization can play a fundamental role in advancing sustainable development goals [89,90]. By leveraging digital technologies, investors can address unique sustainability challenges, including financial inclusion, poverty alleviation, equitable resource distribution, and environmental protection [91]. Therefore, financially and digitally literate CEOs are more likely to strive to achieve SDGs. Digital literacy enables individuals to harness technologies like big data, blockchain, and artificial intelligence, which spur on sustainable initiatives [92,93]. For instance, CEOs with higher digital proficiency can optimize their supply chain operations to reduce emissions and waste, which is in accordance with SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production, Dubey, et al. [94]). Likewise, financial literacy enables CEOs to better assess the financial viability and long-term impact of sustainable investments such as renewable energy, welfare programs, and CSR [84]. Several other studies posit that digital and financial literacy are the pivotal drivers of sustainable development, enabling firms’ CEOs to play a prominent role in global sustainable development; thus, we hypothesize that

H4:

Organizations led by both financially and digitally literate CEOs have a high motivation to participate in SDGs.

3.5. The Moderating Role of Stakeholders’ Pressure

Although the current study predicts a direct relationship between several attributes of CEOs and SDGs’ implementation, we argue that in the presence of stakeholders’ pressure, these relationships will be stronger. Stakeholders’ pressure essentially refers to the influence exerted by various stakeholders (regulators, customers, communities, suppliers, etc.) on firms to invest in sustainable and environmentally friendly practices [43,95]. This pressure exerted by stakeholders is a critical driver of sustainable initiatives, which motivates firms to align their strategies and operations with social, environmental, and community governance principles. The main objective of stakeholders’ pressure is to bridge the gap between broader sustainability objectives and organizational economic goals. Hence, institutional investors prioritize investing in firms that are concerned with environmental and social goals and are accountable in their sustainability reporting [96]. Similarly, activism from consumers also influences the firm’s sustainable development decisions because of the heightened awareness of customers regarding CSR, social practices, and sustainability [97].

The enriched literature demonstrates that social activities highly influence firms that are subjected to stronger levels of pressure from stakeholders. According to Helmig, et al. [98], the positive pressure exerted by stakeholders acts as a catalyst for embedding sustainable practices into the organization’s culture. Meanwhile, regulatory stakeholders, including international organizations and governments, impose compliance requirements along with industry standards that reduce environmental footprints and augment social practices [99,100]. Henceforth, such pressure often reshapes the firm’s priorities, turning sustainability into a competitive advantage from just compliance obligations [101]. Moreover, stakeholder pressure also fosters innovation and collaboration because the firms, with the assistance of stakeholders, co-create solutions to environmental challenges such as green technologies [102]. Furthermore, stakeholder pressure results in corporate legitimacy by ensuring the implementation of required actions.

Earlier, we argued that young and educated CEOs of firms are more likely to engage in activities that are in accordance with SDGs. Yet, the team behind the current study believes that, in the presence of stakeholders’ pressure, this relationship is stronger. Young managers are more environmentally friendly and are proactive in devising environmentally friendly strategies (see [54,55]). The extensive literature supports the argument that young and educated CEOs at the top positions foster social and environmental practices. The relationship of young and educated CEOs and SDG implementation is strengthened by shareholders’ pressure. Young and educated CEOs are more skillful and innovative [103]. At the same time, the positive pressure from stakeholders acts as a catalyst in ensuring the implementation of SDGs (see [98]). So, based on empirical evidence, we suggest that

H5a:

The stakeholders’ pressure strengthens the positive relationship between young and educated CEOs and SDGs, making the relationship robust even in the event of high stakeholder pressure.

Substantial empirical literature suggests that experienced and aged CEOs are more likely to engage in social practices. In this regard, [104] suggested that a longer tenure of CEOs builds greater experience, which aids executives in engaging in more social activities. This is because aged CEOs have fewer career concerns; hence, it allows them to undertake long-term sustainable investments. Moreover, CEOs who are closer to their retirement are more inclined towards sustainable projects because they are more concerned about their legacy instead of short-term benefits [105]. However, stakeholders’ pressure can play a significant role in this relationship, such that the relationship between aged and experienced CEOs and Sustainable Development Goals achievement will be stronger. Stakeholder Theory, validate our argument that stakeholders proactively moderate CSR practices [106]. Similarly, Berg, Holtbrügge, Egri, Furrer, Sinding and Dögl [49] argue that in the presence of stakeholder pressure, firms are more likely to indulge in CSR activities. Therefore, based on this evidence, we suggest that

H5b:

Stakeholders’ pressure strengthens the relationship between aged/experienced CEOs and SDGs, making the relationship robust even in the event of high stakeholder pressure.

Several studies have determined the distinct reaction of CEOs in family and non-family firms to social and sustainable practices, suggesting that firms with CEOs in the family have a strong commitment to socioemotional wealth, which includes their commitment to preserving their family reputation, legacy, and long-term sustainability [107]. Therefore, this commitment results in deep CSR practice engagement, with the goal to potentially maintain their family values, and with the aim of ensuring longevity. Therefore, the CSR activities in non-family firms with non-family CEOs are lower (stated CSR policies and actual implementation are not aligned) in comparison to descendant-led organizations [108,109].

In comparison, the non-family firms’ CEOs prioritize short-term financial performance to enhance shareholders’ value, which sometimes negatively affects CSR practices [110]. However, the influence of stakeholder pressure, specifically from investors and customers who are socially centric, can affect the CEO’s behavior [111]. The pressure from the stakeholders can significantly moderate this relationship by urging both family and non-family firms’ CEOs to ensure environmental and sustainable practices. Several stakeholders, including customers, shareholders, and regulators, exert ample pressure through direct or indirect engagement in order to ensure sustainability in terms of environmental protection [112]. Based on this discussion, we hypothesize that

H5c:

The stakeholder pressure strengthens the relationship between CEOs in/not in the family and SDGs, making the relationship robust even in the event of high stakeholder pressure.

As discussed earlier, digital and financial literacy plays a fundamental role in shaping firms’ environmental and social policies. Financially and digitally literate CEOs are in strong positions to recognize the importance of sustainable practices because they have more information upon which they make informed decisions [113]. Moreover, the understanding of digital finance not only enhances profitability but can also aid sustainability by making strategic investments that are in accordance with the SDGs. For instance, Mishra, Agarwal, Sharahiley, Kandpal, Mishra, Agarwal, Sharahiley, and Kandpal [113] argue that digital financial inclusion has a significant positive impact on SDGs by means of providing easy access to financial services that enhance economic opportunities and reduce poverty. Moreover, financial literacy aids CEOs in making better financial decisions that, in turn, reduce financial stress. Meanwhile, the study of Yadav, et al. [114] strongly suggests that CEOs with high financial literacy tend to steer through complexities related to the digital financial environment and align their strategies with SDG implementation. Under stakeholder pressure, the relationship will be stronger. Stakeholders’ pressure strengthens the commitment of the firm to SDGs, and when the firm is led by digitally and financially literate CEOs, the firm strategically plans to achieve long-term benefits [107], fulfilling the demands of stakeholders. Several studies argue that industry-specific factors, firm-level attributes, and stakeholders’ pressure positively spur on sustainable practices. So, we hypothesize that

H5d:

The stakeholder’s pressure strengthens the relationship between digitally and financially literate CEOs and SDGs, making the relationship robust even in the event of high stakeholder pressure.

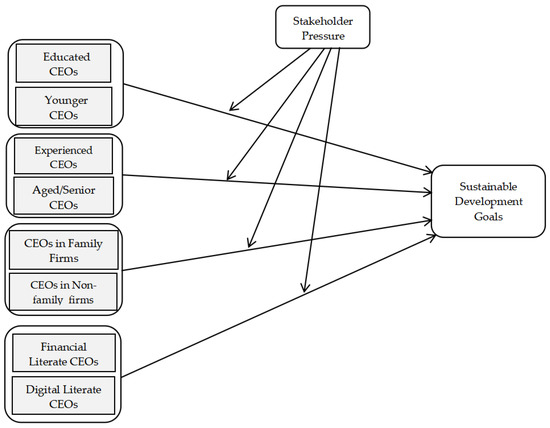

Figure 1 presents the conceptual framework of this study.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

4. Methodology

In order to assess the complex interplay between CEO attributes, stakeholders’ pressure, and engagement with organizational SDGs, this study employed a configurational design grounded in Upper Echelons Theory and Stakeholder Theory. The use of fuzzy-set QCA in this study is grounded in the broader tradition of fuzzy logic applications in decision-making. As demonstrated by Stanojević et al. [115], fuzzy numbers and fractional programming offer robust tools for modeling complex strategic choices, particularly under uncertainty and multidimensional conditions. In the context of our study—where SDG engagement is rarely the result of a single determinant—this approach facilitates the recognition of complex combinations of internal leadership characteristics and their impact on SDG engagement in the presence of stakeholders’ pressure. To understand such complexity, the current study employed fuzzy-set Quantitative Comparative Analysis, a key method in identifying multiple, equally effective causal configurations.

4.1. Population and Sampling

The target population of this research comprises firms operating within China, specifically those operating in economic hubs, including Shanghai, Beijing, and Shenzhen. There are several reasons for choosing these cities. Notably, firms operating in these cities are leading centers of innovation, economic growth, and international trade. Moreover, these firms account for a major portion of GDP and host a high concentration of publicly listed companies, making them highly relevant for our study. China, being the second-largest economy, is under immense domestic and international pressure to align its financial goals with global sustainability standards. While China is the world’s second-largest economy, its firms operate under distinct institutional pressures. For comparison, economies like the USA, Germany, and Japan also face strong global mandates for sustainability, but their firms operate under distinct institutional pressures. The application of our configurational framework in these diverse contexts (EU, USA, Japan) is therefore crucial to validate the generalizability of the successful pathways we identified. Therefore, China provides an especially suitable and fertile ground for investigating our research questions.

We obtained a list of the firms from the China Stock Market & Accounting Research Database (CSMAR), which contains all the firm lists with their information. The firms included in the sample represent diverse sectors, namely Manufacturing, Trading, and Services. A total of 500 questionnaires were distributed, of which 300 were returned, showing a 60% response rate. After rigorous screening for completeness and consistency, 220 of the questionnaires were found useful for further empirical analysis. This method involved the random selection of firms from comprehensive registries and databases within Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen, which belong to the manufacturing, trading, or services industries.

4.2. Procedure and Data Analysis

The hypotheses were tested using fuzzy-set Quantitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA). This methodology was chosen to move beyond conventional linear analyses, providing a nuanced, configurational understanding of how various CEO characteristics interact with each other and with external stakeholder demands to foster high SDG engagement. fsQCA is particularly suited for understanding how combinations (configurations) of factors lead to an outcome, rather than evaluating individual factors in isolation. The data analysis involved several steps inherent to fsQCA.

4.3. Measurement of the Variables

4.3.1. CEO Attributes

The attributes of the CEO presented in Table 1 were operationalized through various indicators, including age, education, experience, and family business background. For education (also referred to as educational qualification), basic 4-point Likert scales were used, where 1 = matriculation, 2 = intermediate, 3 = bachelor’s degree, and 4 = master’s degree or above. The basic purpose of including matriculation was to capture the education level of family firms’ CEOs, where successors often assume managerial responsibilities at an early stage prior to the completion of their higher education. Meanwhile, the CEO’s age was classified into 2 main categories: 18–35 representing young managers, and 35 years and above representing older CEOs. We justify this specific threshold by noting that dividing the sample at age 35 allows us to sharply distinguish younger CEOs. The choice of 35 specifically aligns with the literature linking youthfulness to eco-friendly behavior, better awareness, and proactive strategies due to their enthusiasm and motivation for social activities, often seen in the earlier stages of a career. Conversely, classifying those 35 and above as older/senior captures individuals who have accumulated sufficient experience and developed a broader perspective, enabling them to prioritize long-term success, which is fundamental to Path B’s success. This dichotomy thus proves effective in isolating the distinct drivers for the two most successful proactive configurations observed in our study.

Table 1.

Demographic information.

In terms of experience, managerial experience was measured by the number of years spent in current and previous ventures, with a greater number of years indicating higher managerial experience. Lastly, the ownership context was captured through 2 different categorizations: (1) CEOs in family firms, representing the leaders of family businesses, and (2) non-family firms’ CEOs, representing leaders without family businesses.

4.3.2. Financial Literacy

To assess financial literacy, this study adopted the questionnaire developed by Diéguez-Soto, et al. [116]. This instrument is widely recognized in the literature for its multi-dimensional conceptualization of financial literacy, including CEOs’ knowledge. This questionnaire comprises a total of 6 items measured on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. This financial literacy questionnaire allowed us to assess the variation in perceived financial literacy levels among CEOs. A sample item is, “I am well-informed about alternative financial sources (equity loans, venture capital, MAB, business angels, etc.) rather than bank financing”.

4.3.3. Digital Literacy

For digital literacy, the current study adopted the framework of Ng [117] in the study “Can we teach digital natives digital literacy?”. To capture digital literacy, this instrument encompasses 3 dimensions—technical, cognitive, and social–emotional—with a 15-item scale. Responses were collected using a five-point Likert scale, ranging from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree.

4.3.4. Stakeholder Pressure

For the measurement of stakeholders’ pressure, we adopted the questionnaire framework of Singh, et al. [118], originally developed by Henriques and Sadorsky [119]. The measurement comprises a 9-item scale, with each rating on a five-point Likert scale, encompassing the influence of diverse stakeholders—including investors, customers, regulators, and community actors—upon the strategic and environmental decision-making of a firm. A sample item reads, “Our firm regularly faces expectations from stakeholders (e.g., regulatory agencies, customers) to pursue environmentally friendly innovations.”

4.3.5. SDGs

The SDGs encompass 17 interrelated objectives with the aim of promoting a sustainable future. In most of the prior literature, for each goal, 1 item is used, and in total, 17 items show the SDGs. Hence, we measured the SDGs with 17 items adopted from [120] and measured with a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = lack of participation to 5 = frequent participation.

5. Data Analysis

We tested the hypotheses through FsQCA because it develops configurations of groups to make decisions. In our case, we had various demographic factors, such as age, education, experience, and family background. The FsQCA methodology was chosen to understand whether these attributes individually, exclusively, or complementarily lead to participation in the SDGs. In fsQCA, a fuzzy set allows cases to have partial membership in a set, ranging from 0 (full non-membership) to 1 (full membership), recognizing that social phenomena are matters of degree rather than sharp dichotomies. Within this framework, the outcome variable was conceptualized as ‘high organizational participation in SDGs’ and treated as a fuzzy set.

5.1. Results from FsQCA

Based on the FsQCA analysis, this study explores how various CEO demographic factors, in conjunction with stakeholder pressure, contribute to high organizational participation in SDGs. The study utilized fsQCA to identify causal configurations leading to high SDG participation. Here is an interpretation of the FsQCA results.

5.1.1. Necessary Condition Analysis

The necessary condition analysis reveals that stakeholder pressure (Stk_Press) is a quasi-necessary condition for high SDG participation, with a consistency of 0.90. This implies that while stakeholder pressure is nearly always present when there is high SDG participation, no other single CEO attribute (such as education, age, experience, or literacy) is strictly necessary on its own to achieve high SDG participation.

5.1.2. Sufficient-Condition Solutions

The FsQCA analysis identifies multiple pathways or “configurations” of CEO attributes and stakeholder pressure that are sufficient to lead to high SDG participation. Three types of solutions are reported: parsimonious, intermediate, and complex. The intermediate solution, which applies directional expectations (assuming the presence of certain conditions like high education, literacy, and stakeholder pressure, which is helpful for achieving the SDGs), provides the most interpretable pathways for this study:

Path A (“Young–Skilled–Pressured”): This pathway highlights that younger and highly educated CEOs, combined with both financial and digital literacy, under strong stakeholder pressure, are highly likely to lead to high SDG participation. This is a core presence of these conditions.

Path B (“Older–Experienced–Family–Pressured”): This pathway indicates that older, experienced CEOs in family firms under strong stakeholder pressure, along with at least one type of literacy (financial or digital), are also conducive to high SDG participation. Here, being an older, experienced CEO in a family firm under strong stakeholder pressure is a core condition, while literacy can be peripheral.

Path C (“Professionalized Non-Family”): This pathway demonstrates that even non-family firms can achieve high SDG engagement if their CEO is highly educated, possesses both financial and digital literacy, and operates under strong stakeholder pressure. In this configuration, higher education, both literacies, and strong stakeholder pressure are core conditions.

The overall consistency for the intermediate solution is 0.88, with a raw coverage of 0.69. The complex solution provides further granular detail, for instance, by distinguishing between peripheral financial literacy and peripheral digital literacy in the ‘Older–Experienced–Family–Pressured’ pathway.

5.1.3. Abbreviations

Causal conditions (all fuzzy 0–1):

SDG_High = high organizational participation in SDGs (fuzzy set) as the outcome.

Age_Old = senior/older CEOs (so ~Age_Old ≈ younger).

Edu_High = highly educated CEO (e.g., graduate degree and higher).

Exp_High = experienced CEO (tenure, cross-functional role).

Fam_CEO = family firm CEO (1) vs. non-family (0).

Fin_Lit = highly financially literate CEOs.

Digi_Lit = highly digitally literate CEOs.

Stk_Press = high stakeholder pressure (such as investors, NGOs, media, regulators, customers, and so on).

Calibration (direct method): In this study, full membership is considered as 0.95 (e.g., ≥90th%), crossover = 0.50 (≈median), and full non-membership is considered as 0.05 (≤10th%).

Truth Table thresholds: Frequency cutoff: 2 cases per row (out of all observed rows, only 14 rows meet a frequency ≥ 2).

Consistency cutoff: 0.80 (robustness checked at 0.83, unchanged), which is the threshold used to determine if a condition or configuration is sufficient. The results report consistency (the degree to which the cases sharing the configuration agree in exhibiting the outcome) and coverage (the degree to which the configuration explains instances of the outcome).

Additionally, stakeholder pressure achieved a consistency score of 0.90, identifying it as a quasi-necessary condition. This implies that the presence of high stakeholder pressure is a prerequisite for achieving high SDG participation in this sample. These measures of consistency and coverage determine the sufficiency of causal recipes, rather than statistical significance or effect sizes.

5.1.4. Truth Table

The Truth Table (Table 2) is a crucial analytical tool used in fsQCA. The Truth Table shows which specific combinations (configurations) of CEO attributes and stakeholder pressure are consistently associated with high organizational participation in SDGs.

Table 2.

Truth Table attributes.

- Tested Combinations: It lists various combinations of the seven causal conditions (Age_Old, Edu_High, Exp_High, Fam_CEO, Fin_Lit, Digi_Lit, Stk_Press). Each row represents a specific pattern of presence (1) or absence (0) for these attributes.

- Sufficient Combinations: The table identifies which combinations of CEO characteristics and pressure lead to the desired outcome (high SDG participation). Rows with a consistency (Consistency) score above the set cutoff (0.80) are considered sufficient to produce high SDG participation (Outcome = 1).

- Core Configurations: Of the 14 rows observed with sufficient cases, the results show that specific patterns, such as Row 1 (Young, Higher Education, Dual Literacy, High Pressure) and Row 2 (Older, Experienced, Family CEO, High Pressure), are successful routes to high SDG outcomes.

In essence, the Truth Table provides the raw data foundation used by the fsQCA methodology to formally identify the three effective pathways—Path A, Path B, and Path C—that ultimately lead to high SDG engagement.

Notation: 1 = high membership (~0.67–1), 0 = low membership (~0–0.33). (Fuzzy values were used, shown here dichotomized for display.) Outcome column = SDG_high; “Cons.” = row consistency.

Table 3 shows necessary conditions, indicating if any attributes of CEOs as individuals or collectively necessary for SDGs. Table 4 shows parsimonious solution in two categories that are aligned with SDGs. In Table 5, intermediate solutions were discussed that shows if any of the attributes could be presented or excluded for SDGs participation in businesses. Similarly, Table 6 shows core solutions and ideas of the attributes of CEOs for SDGs.

Table 3.

Necessary conditions.

Table 4.

Parsimonious solution.

Table 5.

Intermediate solution (directional expectations applied).

Table 6.

Complex solution (remainders were not used).

5.2. Robustness Checks

The robustness checks confirm the stability of the findings:

Raising the consistency cutoff to 0.83 did not alter the structure of the intermediate solution, only causing minor drops in coverage (see Table 7). Importantly, the analysis showed conjunctural causation for Path A, meaning that no single condition within that path is a “silver bullet”; removing any one of them would reduce the consistency below 0.80. This reinforces that the phenomenon is configurational, implying that high SDG participation results from specific combinations of CEO attributes and stakeholder pressure, rather than from isolated factors (except for stakeholder pressure being quasi-necessary).

Table 7.

Consistency and raw coverage.

5.3. Hypotheses Remarks

The FsQCA results provide strong support for most of the hypotheses, often highlighting the critical role of stakeholder pressure:

H1 (Younger and educated CEOs → SDGs): This hypothesis is supported through Path A, where younger and highly educated CEOs are a core component, especially when combined with financial and digital literacy, and strong stakeholder pressure.

H2 (Older/experienced CEOs → SDGs): This hypothesis is conditionally supported. Older and experienced CEOs contribute to SDG participation primarily via Path B, but only when coupled with family control, strong stakeholder pressure, and at least one type of literacy (financial or digital).

H3 (Family Firms’ CEOs > Non-family): This hypothesis is partially supported. While family firms’ CEOs are identified as a core condition in Path B (along with older/experienced CEOs and pressure), Path C explicitly shows an alternative route for non-family firms to achieve high SDGs when led by highly educated, dual-literate CEOs under strong pressure.

H4 (Financial and digital literate CEOs → SDGs): This hypothesis is supported. Dual literacy is a core condition in Path A and Path C, and at least one form of literacy appears as a peripheral condition in Path B.

H5a (Pressure strengthens young and educated → SDGs): This is supported. Stakeholder pressure is a core and necessary condition in Path A, directly enhancing the relationship between young, educated CEOs and SDGs.

H5b (Pressure strengthens aged/experienced → SDGs): This is supported in Path B, where stakeholder pressure is a core condition in the configuration leading to high SDGs.

H5c (Pressure strengthens family/non-family → SDGs): This is supported. Stakeholder pressure appears as a core condition in both Path B (for family firms’ CEOs) and Path C (for non-family firms’ CEOs), indicating its strengthening role regardless of family control.

H5d (Pressure strengthens literate CEOs → SDGs): This is supported. Stakeholder pressure interacts with both financial and digital literacy as a core conjunction in Paths A and C, indicating its strengthening effect on the relationship between literate CEOs and SDGs.

In summary, the FsQCA results clearly demonstrate that high SDG participation is not driven by isolated CEO characteristics but rather by specific configurations of these attributes, most notably when combined with significant stakeholder pressure. Stakeholder pressure itself emerges as a critical quasi-necessary condition.

6. Discussion

Previous studies have shown that corporate leaders and stakeholders stimulate organizational sustainability strategies, yet few studies have examined the collective impact of CEOs’ attributes in sustainability development. This study responds to this gap by examining how top management attributes, in the presence of stakeholders’ pressure, improve the firm’s engagement with the SDGs. This study, adopting a configurational framework, using fsQCA, reveals that several combinations of CEO’s attributes—including age, education, experience, and literacy—together with stakeholders’ pressure, enhance the firm-level SDG participation.

For instance, our first hypothesis proposed that firms led by younger and more educated CEOs are more likely to engage in activities that align with SDGs. Our fsQCA results validate our proposition, particularly through Path A, which shows that firms that have younger CEOs with higher levels of education emerge as strong drivers of SDG engagement. Our findings corroborate earlier research in this context. Similarly, Garrido-Ruso, Aibar-Guzmán, and Suárez-Fernández [29] in their study concluded that CEOs with higher education are more likely to align the firm’s objectives with SDGs. In parallel, several studies highlight the CEO’s youthfulness as a significant factor influencing a firm’s SDG engagement. For instance, our findings are in line with the study of Dimitrova, Vaishar, Šťastná, Dimitrova, Vaishar, and Šťastná [54], which stated that young managers have better awareness of sustainable strategies that foster sustainable practices. Taken together, although in isolation, these studies collectively validate our hypothesis that young and educated CEOs actively participate in sustainable practices that are in accordance with the SDGs. This is also verified by Triyani and Setyahuni [121], who found that age is negatively related and education is positively related to ESG disclosure.

Our findings provide conditional support for H2, specifically along path B. We proposed that older and experienced managers are more likely to engage in sustainable practices that are in accordance with the SDGs. However, the findings from Path B indicate that the relationship between older/experienced managers and SDG engagement is effective only under conditions of family control, strong stakeholder pressure, and at least one form of literacy (digital or financial). This suggests that experience alone is not sufficient to drive a sustainable orientation unless embedded within governance structures (such as family ownership) in addition to the external pressure.

Several studies found a direct linear relationship between older/experienced managers and firms’ sustainability [122,123]. However, our findings do not support such a direct linear relationship. There are several possible reasons for this anomaly. First, the conditional support for our hypothesis might be explained by the Chinese culture. Rooted in Confucian traditions, aged managers mostly demonstrate more conservative and risk-averse behavior, therefore engaging in sustainable practices primarily when pressured to do so by the stakeholders [124]. Moreover, while younger CEOs are proactive and sustainability-oriented, older CEOs might adopt SDG practices only as a reactive strategy to societal pressure [125].

Similarly, the current study proposed that the CEOs in family firms are more likely to engage their firms in SDG-related activities compared to non-family firms’ CEOs. Our findings provide partial support for this proposition. Path B indicates that family firms’ CEOs, in combination with older age, experience, stakeholder pressure, and at least one kind of literacy, play a pivotal role in enhancing a firm’s SDG participation. Yet, Patch C indicates a unique, but equally effective route for non-family firms’ CEOs, suggesting that when highly educated non-family firms’ CEOs are equipped with high digital and financial literacy, they leverage their modern managerial credentials and professional capabilities to attain SDGs. Path B somehow supports the social–economic wealth perspective, which suggests that family leaders are more concerned about their long-term reputation and intergenerational legacy, hence supporting sustainability-oriented activities, but under the condition of external pressure [126]. This indicates that family firms are more concerned about their own legacy and reputation, but the pressure of stakeholders and complementary attributes collectively affect the relationship between family control and engagement with SDGs. As a result, SDG engagement becomes a strategic tool for sustaining the family image (see [127]). In contrast, Path C highlights that non-family firms’ CEOs emphasize professional management over their legacy [127], making them more responsive to stakeholders’ demands with the help of their skills and professionalism [127]. The unique institutional setting of Chinese firms contextualizes the partial support for H3. Family firms (Path B) are deeply motivated by socioemotional wealth and the need to preserve the family reputation and long-term legacy, aligning with cultural continuity. However, the prevalence of Path C shows that professionalization in non-family Chinese firms, driven by highly skilled CEOs, offers an equally effective route. This dual reality reflects the country’s intense domestic and international pressure to meet global sustainability standards, requiring both legacy commitment and professional acumen.

The results also indicate that digital and financial literacy act as key enablers of CEO- driven engagement. This strongly supports our H4, which proposes that financial literacy and digital literacy are key determinants of engagement with SDGs. In fact, dual literacy appeared as a core condition in Paths A and C, while at least one form of literacy—digital or financial—plays a supporting role in Path B. Interestingly, the literacy element is especially critical in non-family firms. Our findings corroborate prior research, which shows that digital and financial literacy enhance sustainability [128], as well as strengthen a firm’s ability to pursue long-term sustainable goals [129], and that digital literacy is a core element in a firm’s sustainable innovation, contributing to the firm’s progress towards sustainable development [130].

Lastly, our study proposed that stakeholders’ pressure plays a moderating role between the CEO’s attributes and SDGs’ engagement. The findings provide strong evidence supporting the moderating role of stakeholders’ pressure, validating that it is the element that strengthens the relationship between CEOs’ attributes and SDG engagement. Notably, in all three configurational paths, stakeholder pressure emerged as a core condition, underscoring its quasi-necessary role in determining the sustainable behavior of the firm. Particularly, in Path A, it shows that younger and educated CEOs perform rigorously in sustainable practice when they are under stakeholders’ pressure. Moreover, the findings reveal that the older/experienced family firms’ CEOs (Path B), under stakeholders’ pressure, engage in activities that align with SDGs, and empower highly educated, non-family members to deliver on SDGs.

Collectively, all paths—A, B, and C—demonstrate that external legitimacy demands and stakeholders’ expectations are the pivotal catalysts that are fundamental for transforming CEOs’ attributes into sustainability outcomes. These findings lend support to the prior literature. For instance, Helmig, Spraul, Ingenhoff, and Bernd Helmig [98] determined stakeholder pressure as a catalyst in a firm’s sustainable development. Similarly, Dal Maso, et al. [131] found that the stakeholders’ pressure positively supports the relationship between the environmental and financial performance of a firm. The meta-analysis of Wang, Li, and Qi [44] confirms that the stakeholders’ pressure—especially in proactive strategies—consistently results in better environmental performance. Together, all these studies affirm the constructive role of stakeholders’ pressure in transforming the CEO’s attributes into sustainable practices.

6.1. Theoretical Contribution

This study significantly advances the existing theoretical understanding by offering a nuanced, configurational perspective on the drivers of organizational participation in SDGs. Our findings contribute primarily to the literature on SDGs and corporate sustainability, as well as to established theories such as UET and Stakeholder Pressure Theory.

1. Contribution to the Literature on SDGs, CEO Attributes, and Sustainability through a Configurational Lens: Prior research has often examined the impact of individual CEO attributes (e.g., education, age, experience, CEOs in family and non-family firms, literacy) or external stakeholder pressure in isolation on CSR and sustainability outcomes. While these studies have established positive links between specific CEO characteristics and engagement in sustainable practices, they largely overlooked the complex, configurational interplay among these factors. Our study addresses this critical gap by employing fsQCA, which allows us to explore how multiple conditions combine to produce high organizational participation in SDGs. We demonstrate that high SDG participation is not the result of a single “silver bullet” factor but rather emerges from multiple, equally effective combinations of CEO attributes and stakeholder pressure. For instance, our findings reveal distinct pathways: Path A (“Young–Skilled–Pressured”) highlights that younger, highly educated CEOs with strong financial and digital literacy, operating under significant stakeholder pressure, are a powerful configuration for high SDG engagement. This underscores that specific bundles of capabilities and external context are crucial.

Path B (“Older–Experienced–Family–Pressured”) indicates that older, experienced family firms’ CEOs, particularly when combined with at least one form of literacy (financial or digital) and operating under strong stakeholder pressure, also lead to high SDG participation. This illustrates the enduring value of seasoned leadership within a family firm context, especially when supported by modern competencies and external impetus. Path C (“Professionalized Non-Family”) reveals a route for non-family firms, where highly educated, financially and digitally literate CEOs can drive high SDG engagement, again under strong stakeholder pressure. This shows that professionalization, combined with critical modern literacies, can compensate for the absence of family-specific drivers.

Confirming Conjunctural Causation: Through robustness checks, we confirm that dropping any single core condition from these successful configurations (e.g., Path A) significantly reduces consistency, unequivocally demonstrating conjunctural causation—meaning no single attribute alone is sufficient to explain high SDG participation. This complex understanding enriches the sustainability literature by providing a more realistic and comprehensive model of how firms achieve their SDG objectives.

2. Contribution to Upper Echelons Theory (UET) and Stakeholder Pressure Theory: Extending UET: UET posits that strategic choices and organizational outcomes are a reflection of the demographic and psychological characteristics of top managers [25]. Our research significantly extends UET by demonstrating that while CEO characteristics are indeed crucial for strategic outcomes like SDG implementation, their impact is fundamentally conjunctural. We show that individual CEO attributes do not operate in isolation but rather form synergistic combinations with other internal characteristics and external environmental conditions. Our specific findings, such as the support for H1, H2, H3, and H4, confirm that attributes like being younger and highly educated or being older and experienced, being a family or a non-family firm, and being digitally and financially literate are critical components within successful configurations for high SDG participation. This configurational extension provides a more refined application of UET, highlighting the importance of considering the holistic profile of a CEO within their specific context.