Structural Equation Model for Assessing Relationship Between Green Skills and Sustainable Entrepreneurial Intentions

Abstract

1. Introduction

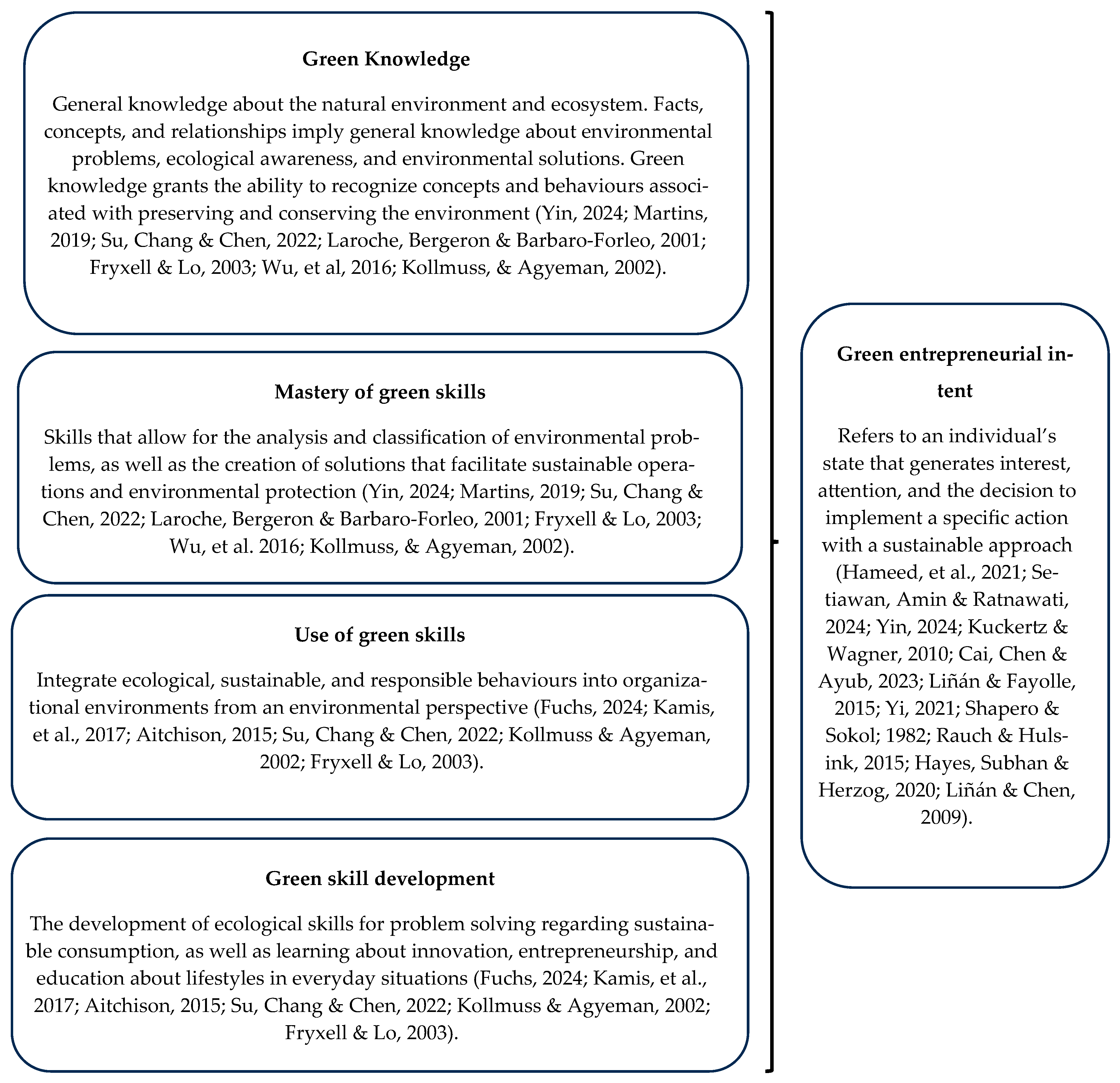

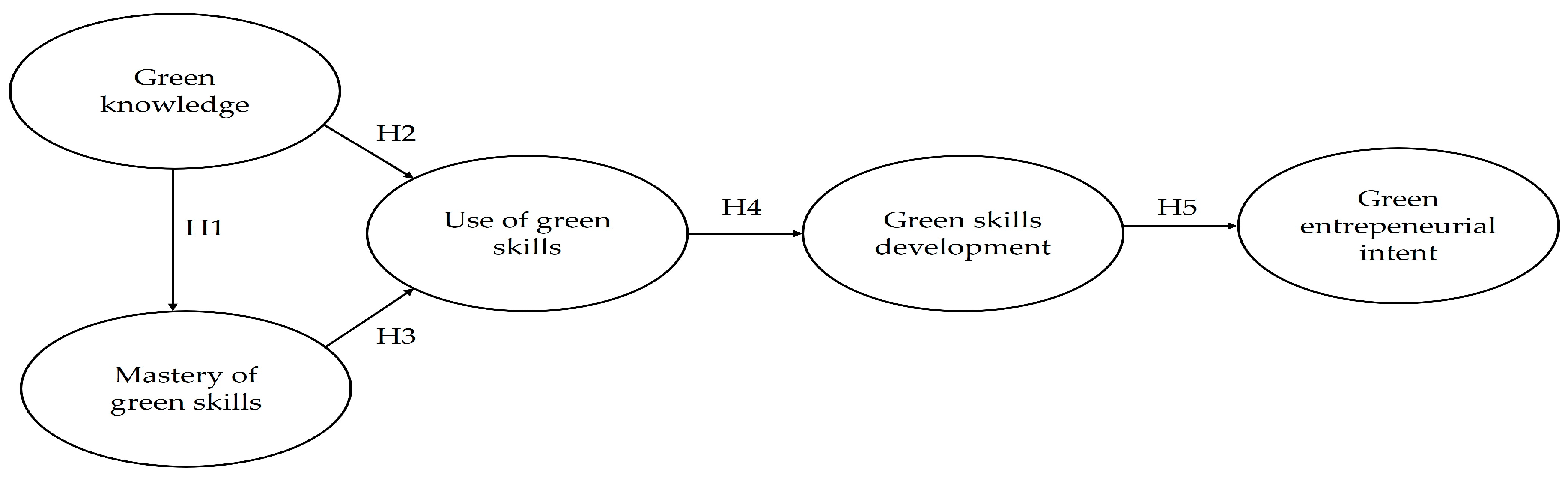

Literature Review

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Population and Sample

2.2. Data Collection Method

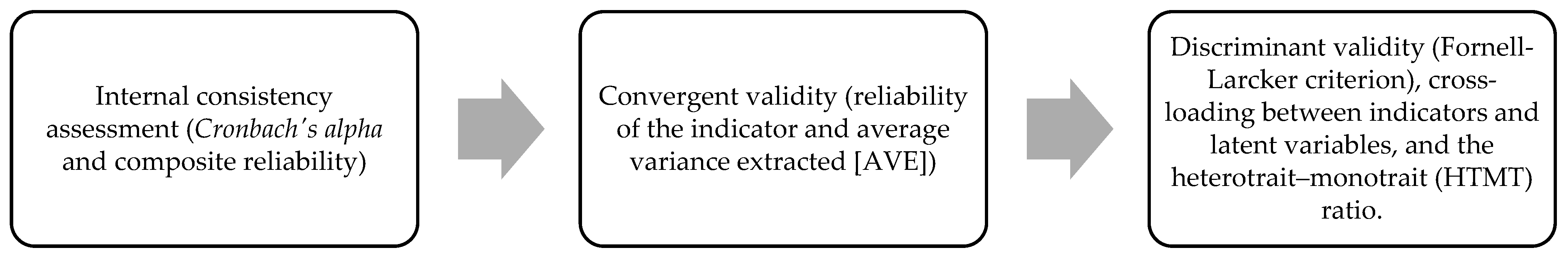

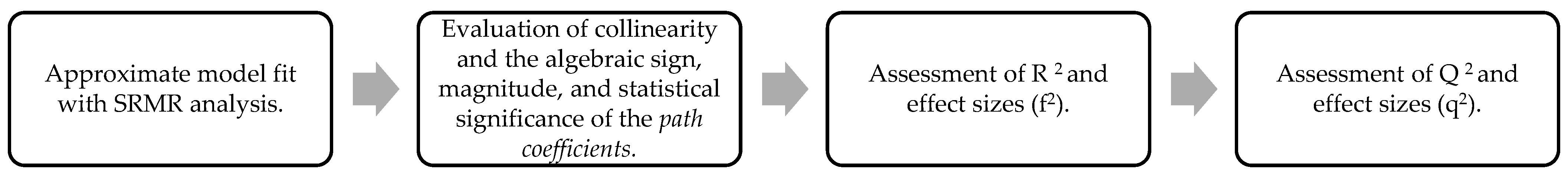

2.3. Procedure and Data Analysis

3. Results

- (a)

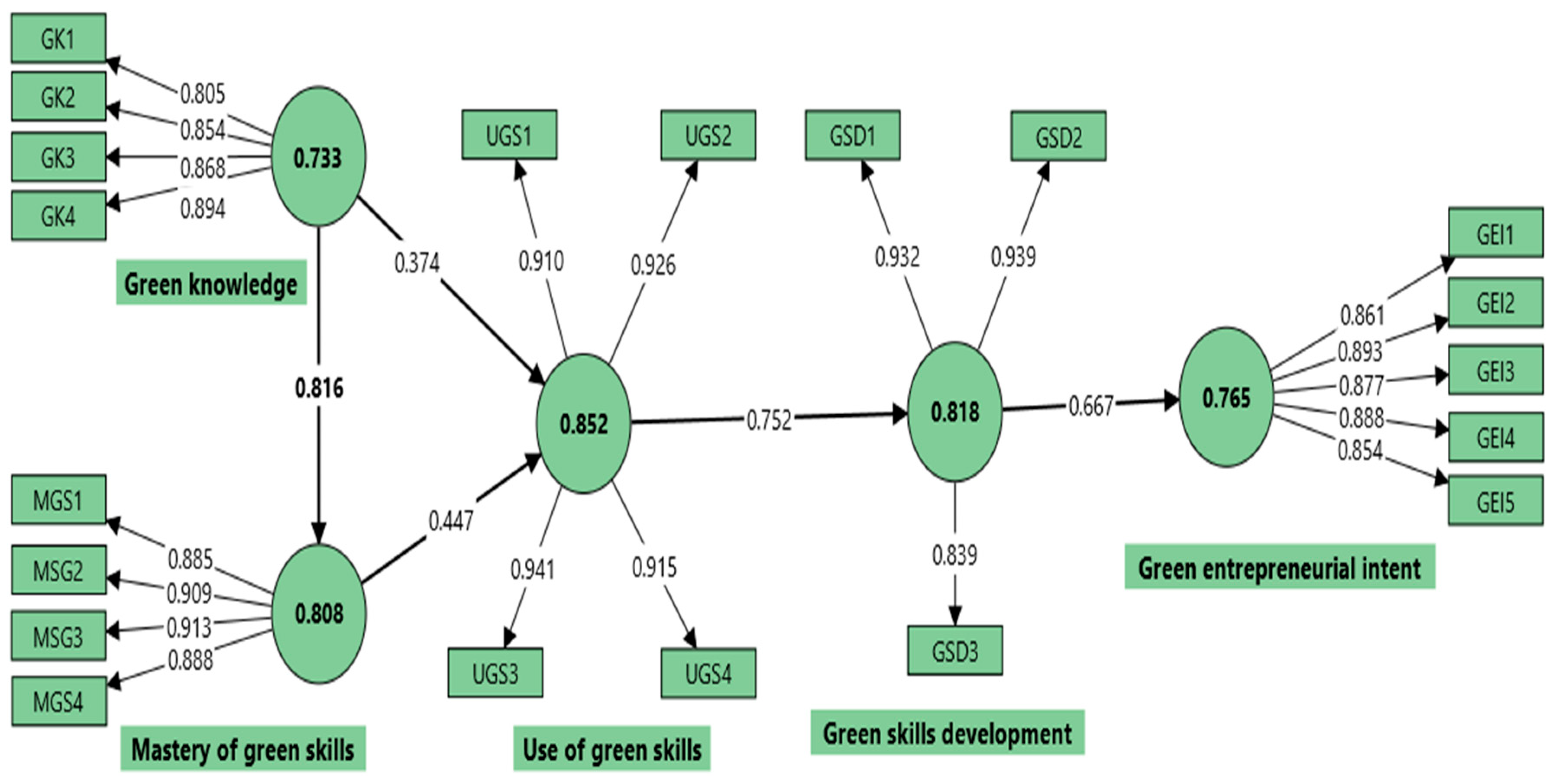

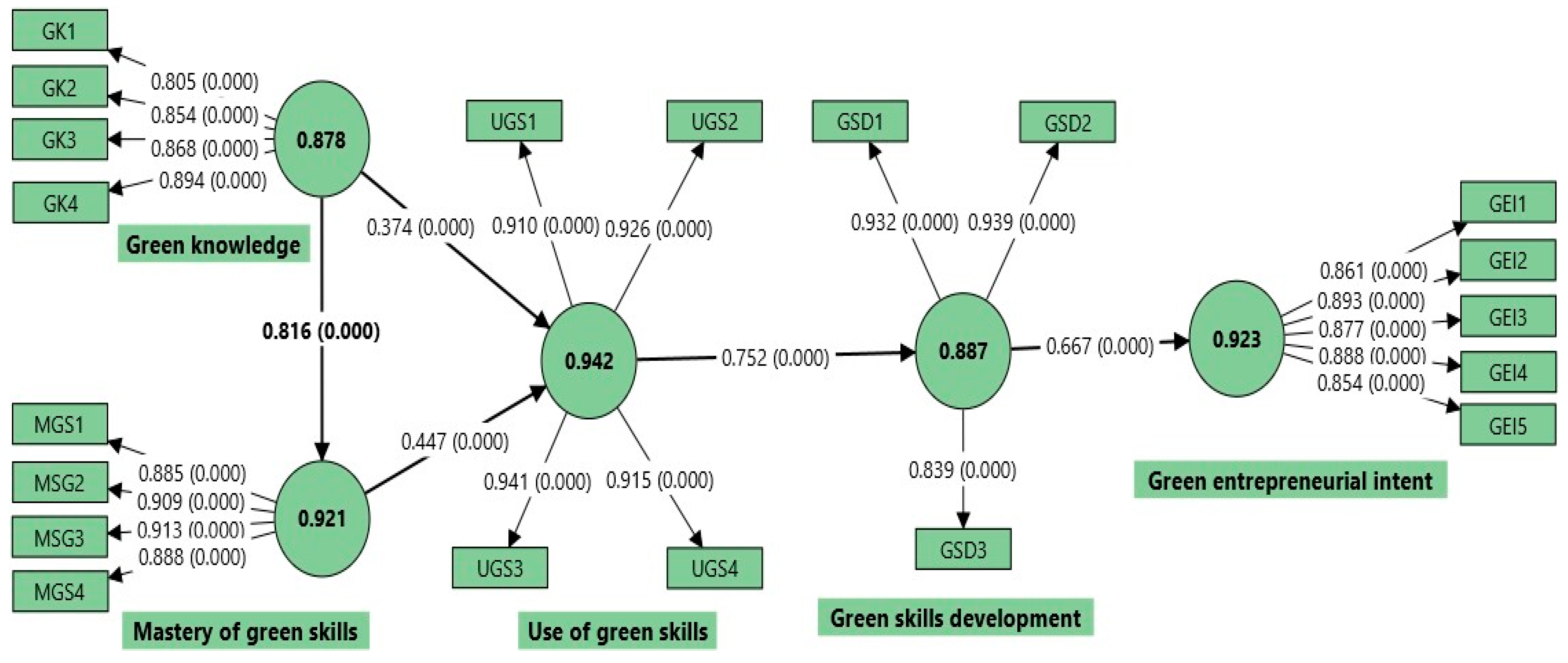

- Measurement model

- (b)

- Structural model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- I understand what environmental protection is.

- I have professional knowledge of topics such as energy, waste, resource efficiency and sustainable development.

- I have knowledge of topics such as energy conservation and ecosystem protection.

- I have knowledge of environmental management responsibility.

- I have knowledge of environmental protection.

- I have management or work experience related to energy, waste, resource efficiency and sustainable development.

- I have skills related to energy conservation and ecosystem protection.

- I have skills related to environmental management responsibility.

- I can effectively use environmental skills in my studies and in my life.

- I can apply knowledge and skills related to energy, waste, resource efficiency and sustainable development in management or at work.

- I can apply skills related to energy conservation and ecosystem protection in my studies and in my life.

- I have skills related to energy conservation and ecosystem protection.

- I believe that my professional knowledge continues to improve.

- I believe that the resources and knowledge provided by the institution effectively help me to grow professionally.

- The various platforms and opportunities offered by the institution strengthen my capacity for green-oriented professional practice.

- I am willing to do whatever it takes to become a green entrepreneur.

- My professional goal is to become a green entrepreneur.

- I am determined to start an eco-friendly business in the future.

- I am willing to do whatever it takes to become a green entrepreneur during my university studies.

- I will act as an agent of change and focus on managing a social or eco-friendly business.

References

- Sern, L.C.; Adamu, H.M.; Salleh, K.M. Development of competency framework for Nigerian TVET teachers in tertiary TVET institutions. J. Techn. Educ. Train. 2019, 1, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderi, N.; Monavvarifard, F.; Salehi, L. Fostering sustainability-oriented knowledge-sharing in academic environment: A key strategic process to achieving SDGs through development of students’ sustainable entrepreneurship competences. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2022, 20, 100603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.D.; Schmidt-Traub, G.; Mazzucato, M.; Messner, D.; Nakicenovic, N.; Rockstrm, J. Six Transformations to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, L.M.; Reyes, J.F. Sustainable entrepreneurial intentions: Exploration of a model based on the theory of planned behaviour among university students in north-east Colombia. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2022, 2, 100627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, M. Green Skills for Sustainability Transitions. Geogr. Compass. 2024, 18, e70003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, T.; Elliott, D. Green skills gap—A way ahead. Front. Sociol. 2025, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leal, W.; Shiel, C.; Paço, A.; Mifsud, M.; Avila, L.V.; Brandli, L.L.; Molthan-Hill, P.; Pace, P.; Azeiteiro, U.M.; Vargas, V.R.; et al. Sustainable Development Goals and sustainability teaching at universities: Falling behind or getting ahead of the pack? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 232, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, I.; Zaman, U.; Waris, I.; Shafique, O. A serial-mediation model to link entrepreneurship education and green entrepreneurial behavior: Application of resource-based view and flow theory. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, M.H.; Amin, B.F.; Ratnawati, I. Green Entrepreneurial Intentions and University Support for Green Entrepreneurial Behavior: A Systematic Literature Review. Res. Horiz. 2024, 4, 339–350. Available online: https://journal.lifescifi.com/index.php/RH/article/view/344 (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Truong, H.T.; Le, T.P.; Pham, H.T.; Do, D.A.; Pham, T.T. A mixed approach to understanding sustainable entrepreneurial intention. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2022, 20, 100731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C. From green entrepreneurial intention to behaviour: The role of environmental knowledge, subjective norms, and external institutional support. Sustain. Futures 2024, 8, 10033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louw, W. Green curriculum: Sustainable learning at a higher education institution. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2013, 14, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handayani, M.N.; Kamis, A.; Ali, M.; Wahyudin, D.; Mukhidin, M. Development of green skills module for meat processing technology study. J. Food Sci. Educ. 2021, 20, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamis, A.; Rus, R.C.; Rahim, M.B.; Yunus, F.A.; Zakaria, N.; Affandi, H.M. Exploring green skills: A study on the implementation of green skills among secondary school students. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2017, 7, 327–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dote-Pardo, J.; Ortiz-Cea, V.; Peña-Acuña, V.; Severino-González, P.; Contreras-Henríquez, J.M.; Ramírez-Molina, R.I. Innovative Entrepreneurship and Sustainability: A Bibliometric Analysis in Emerging Countries. Sustainability 2025, 17, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makuya, V.; Changalima, I.A. Unveiling the role of entrepreneurship education on green entrepreneurial intentions among business students: Gender as a moderator. Cogent Educ. 2024, 11, 2334585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Hussain, S.; Zhang, Y. Factors that can promote the green entrepreneurial intention of college students: A fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckertz, A.; Wagner, M. The influence of sustainability orientation on entrepreneurial intentions-Investigating the role of business experience. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 59, 524–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, W.L.; Trevisan, L.V.; Dinis, M.A.; Ulmer, N.; Paço, A.; Borsari, B.; Salvia, A. Fostering students’ participation in the implementation of the sustainable development goals at higher education institutions. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, B.; Chen, Y.; Ayub, A. Quiet the Mind, and the Soul Will Speak! Exploring the Boundary Effects of Green Mindfulness and Spiritual Intelligence on University Students’ Green Entrepreneurial Intention–Behavior Link. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F.; Rodriguez-Cohard, J.C. Rueda-Cantuche, J.M. Factors affecting entrepreneurial intention levels: A role for education. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2011, 7, 195–218. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11365-010-0154-z (accessed on 12 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Yi, G. From green entrepreneurial intentions to green entrepreneurial behaviors: The role of university entrepreneurial support and external institutional support. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2021, 17, 963–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gucaj, A.; Merko, F.; Ramallari, A. Impact of green economy in sustainable development. Int. J. Ecosyst. Ecol. Sci. 2021, 11, 753–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PNUM. United Nations Environment Programme. How is a Green Economy Defined? Available online: https://www.unep.org/explore-topics/green-economy (accessed on 28 May 2024).

- Le Blanc, D. Special issue on green economy and sustainable development. Nat. Resour. Forum 2011, 35, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OIT. International Labour Organization World Employment and Social Outlook 2018—Greening with Jobs. 2018. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/publications/world-employment-and-social-outlook-2018-greening-jobs (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Loiseau, E.; Saikku, L.; Antikainen, R.; Droste, N.; Hans-Jürgens, B.; Pitkánen, K.; Leskinen, P.; Kuikman, P.; Thomsen, M. Green economy and related concepts: An overview. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 139, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vertakova, Y.V.; Plotnikov, V.A. Assessment of the economic activity greening level and the green economy development directions. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 392, 012078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kummitha, H.R.; Kummitha, R.K.R. Sustainable entrepreneurship training: A study of motivational factors. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2021, 19, 100449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelwahed, N.A.; Alshaikhmubarak, A. Developing female sustainable entrepreneurial intentions through an entrepreneurial mindset and motives. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, F. Defining and developing environmental competence. Adv. Exp. Soc. Process 1980, 2, 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichter, K.; Tiemann, I. Factors influencing university support for sustainable entrepreneurship: Insights from explorative case studies. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 175, 512–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitchison, K. Adapting Green Skills to Vocational Education and Training: Questionnaire Report; Landward Research Ltd.: Sheffield, UK, 2015; Available online: https://www.pscherer-online.de/www/download/Zusammenfassung.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Martins, V.; Rampasso, I.S.; Anholon, R.; Quelhas, O.L.; Leal, W. Knowledge management in the context of sustainability: Literature review and opportunities for future research. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, C.; Dhar, R.L. Green competencies: Construct development and measurement validation. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 235, 887–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q.; Chang, Y.C.; Chen, P.F. Design of a green skills scale for Chinese University students. Educ. Res. Rev. 2022, 17, 288–298. Available online: https://academicjournals.org/journal/ERR/article-abstract/CA2B33F70112 (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Wegenberger, O.; Ponocny, I. Green Skills Are Not Enough: Three Levels of Competences from an Applied Perspective. Sustainability 2025, 17, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vona, F.; Marin, G.; Consoli, D.; Popp, D. Environmental Regulation and Green Skills: An Empirical Exploration. J. Assoc. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2018, 713–753. Available online: https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/698859 (accessed on 8 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Diepolder, C.S.; Weitzel, H.; Huwer, J. Competence frameworks of sustainable entrepreneurship: A systematic review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, J. The Theory of Economic Development: An Inquiry into Profits, Capital, Credit, Interest and the Business Cycle, Translated from the German by Redvers Opie, New Brunswick (U.S.A) and London (U.K.); Transaction Publishers: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1934; Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4499769 (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Ajzen, I. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In Action-Control: From Cognition to Behavior; Kuhl, J., Beckman, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapero, A.; Sokol, L. The Social Dimensions of Entrepreneurship. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign’s Academy for Entrepreneurial Leadership Historical Research Reference in Entrepreneurship. 1982. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1497759 (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Jebsen, S.; Senderovitz, M.; Winkler, I. Shades of green: A latent profile analysis of sustainable entrepreneurial attitudes among business students. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2023, 21, 100860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N.; Reilly, M.; Carsrud, A. Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2000, 15, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, A.; Hulsink, W. Putting entrepreneurship Education where the intention to Act lies: An investigation into the impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial behavior. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2015, 14, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Gregorio, S.; Badenes-Ribera, L.; Oliver, A. Effect of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurship intention and related outcomes in educational contexts: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2021, 19, 100545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, K.; Gibbs, D. Rethinking green entrepreneurship-Fluid narratives of the green economy. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2016, 48, 1727–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Razzaq, A.; Mohsin, M.; Irfan, M. Spatial spillovers and threshold effects of internet development and entrepreneurship on green innovation efficiency in China. Technol. Soc. 2022, 68, 101844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sola, A.O. Environmental education and public awareness. J. Educ. Soc. Res. 2014, 4, 333–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, L.; Namestovski, Ž.; Horák, R.; Bagány, Á.; Krekić, V. Teach it to sustain it! Environmental attitudes of Hungarian teacher training students in Serbia. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 154, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.S.; Baharon, N.; Foong, L.M. Integrating Knowledge Aspects of Green Skills into Engineering Programmes: The Perceptions of Engineering Lecturers in Malaysia Polytechnics. In Proceedings of the IEEE 10th International Conference on Engineering Education (ICEED), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 8 November 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, H.; Geissler, M.; Hundt, C.; Grave, B. The climate for entrepreneurship at higher education institutions. Res. Policy 2018, 47, 700–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.C.; Liguori, E.W. Entrepreneurial self-efficacy and intentions: Outcome expectations as mediator and subjective norms as moderator. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2019, 26, 400–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research, 1st ed.; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1975; pp. 118–142. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233897090_Belief_attitude_intention_and_behaviour_An_introduction_to_theory_and_research (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Fayolle, A.; Gailly, B.; Lassas-Clerc, N. Assessing the impact of entrepreneurship education programmes: A new methodology. J. Eur. Ind. Train. 2006, 30, 701–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F.; Fayolle, A. A Systematic Literature Review on Entrepreneurial Intentions: Citation, Thematic Analyses, and Research Agenda. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2015, 11, 907–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, A. Challenges in predicting new firm performance. J. Bus. Ventur. 1993, 8, 241–253. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/0883902693900309 (accessed on 12 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Hayes, D.; Subhan, Z.; Herzog, L. Assessing and understanding entrepreneurial profiles of undergraduate students: Implications of heterogeneity for entrepreneurship education. Entrep. Educ. 2020, 3, 151–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, M.; Bergeron, J.; Barbaro-Forleo, G. Targeting consumers who are willing to pay more for environmentally friendly products. J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryxell, G.E.; Lo, C.W. The influence of environmental knowledge and values on managerial behaviours on behalf of the environment: An empirical examination of managers in China. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 46, 45–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.H.; Thongma, W.; Leelapattana, W.; Huang, M.L. Impact of hotel employee’s green awareness, knowledge, and skill on hotel’s overall performance. Adv. Hosp. Leis. 2016, 5, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F.; Chen, Y. Development and Cross–Cultural Application of a Specific Instrument to Measure Entrepreneurial Intentions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimzadegan, H.; Meiboudia, H. Exploration of environmental literacy in science education curriculum in primary schools in Iran. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 46, 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Sharma, N.; Kumar, S.; Asif, M. Catalyzing green entrepreneurial behavior: The role of intentions and selective factors. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2337959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano, J.L.; Mejía-Trejo, J. Modelado de Ecuaciones Estructurales en el campo de las Ciencias de la Administración. Rev. Métodos Cuant. Econ. Empresa. 2022, 33, 242–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.; Smith, D.; Reams, R.; Hair, J. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): A useful tool for family business researchers. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2014, 5, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Bush, R.; Ortinau, D.J. Investigación de mercados. In Un Ambiente de Información Digital, 6th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 42–67. Available online: https://www.uachatec.com.mx/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/3.-INVESTIGACI%C3%93N-DE-MERCADOS-HAIR-Y-BUSH-3.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Zeller, R.A.; Carmines, E.G. Measurement in the Social Sciences, the Link Between Theory and Data; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1980; pp. 18–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 78, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulland, J. Use of partial least squares (PLS) in strategic management research: A review of four recent studies. Strateg. Manag. J. 1999, 20, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grande, E.I.; Abascal, E. Fundamentos y Técnicas de Investigación Comercial. 9ª Edición. Pozuelo de Alarcón, España; Esic Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 2007; pp. 42–61. Available online: https://sgfm.elcorteingles.es/SGFM/dctm/MEDIA02/CONTENIDOS/201409/08/00106524190748____1_.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Nguyen, O. Factors affecting the intention to use digital banking in Vietnam. J. Asian Finan. Econ. Bus. 2020, 7, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. The Partial Least Squares approach to Structural Equation Modelling. In Modern Methods for Business Research; Marcoulides, G.A., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1988; pp. 295–358. Available online: https://share.google/OKLUsVa3NOcqlaOV3 (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Zahoor, N.; Khan, H.; Khan, Z.; Akhtar, P. Responsible innovation in emerging markets’ SMEs: The role of alliance learning and absorptive capacity. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2022, 41, 1175–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The use de partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. Adv. Int. Mark. 2009, 20, 277–320. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2176454 (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Widodo, M.; Irawan, M.; Sukmono, R. Extending UTAUT2 to explore digital wallet adoption in Indonesia. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Information and Communications Technology (ICOIACT), Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 24–25 July 2019; pp. 878–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmines, E.; Zeller, R. Reliability and validity assessment. N. 07-017. In Sage University Paper Series on Quantitative Applications the Social Sciences; Sage Research Methods: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1979; pp. 8–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Hult, G.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling; Sage Research Methods: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017; pp. 44–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, A.H.; Malhotra, A.; Segars, A. Knowledge Management: An Organizational Capabilities Perspective. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2001, 18, 185–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, N.; Huang, X.; Mahmood, A.; AlGerafi, M.; Javed, S. Project-based learning as a catalyst for 21st-Century skills and student engagement in the math classroom. Heliyon 2024, 10, e39988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Sivo, S.A. Sensibilidad de los índices de ajuste a la especificación errónea del modelo y a los tipos de modelo. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2007, 42, 509–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, D.; Coughlan, J.; Mullen, M.R. Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electron. J. Bus. Res. Methods 2008, 6, 53–60. Available online: https://academic-publishing.org/index.php/ejbrm/article/view/1224 (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- González Huelva, I. Modelos PLS-PM; Universidad de Sevilla: Sevilla, Spain, 2018; Available online: https://idus.us.es/server/api/core/bitstreams/e6597824-8220-4ec5-a835-6a10ac0f8729/content (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988; Available online: https://utstat.utoronto.ca/~brunner/oldclass/378f16/readings/CohenPower.pdf (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mamary, Y.H. Factors shaping green entrepreneurial intentions towards green innovation: An integrated model. Future Bus. J. 2025, 11, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulà, I.; Tilbury, D.; Ryan, A.; Mader, M.; Dlouhá, J.; Mader, C.; Benayas, J.; Dlouhý, J.; Alba, D. Catalysing Change in Higher Education for Sustainable Development: A review of professional development initiatives for university educators. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2017, 18, 798–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Dai, L.; Deng, L.; Peng, P. Analysis of farmers’ perceptions and behavioral response to rural living environment renovation in a major rice-producing area: A case of Dongting Lake Wetland, China. Cienc. Rural 2021, 51, e20200847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Ding, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, L. Key factors affecting the adoption willingness, behavior, and willingness-behavior consistency of farmers regarding photovoltaic agriculture in China. Energy Policy 2021, 149, 112101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Jin, J.; He, R.; Mao, J. The deviation between the willingness and behavior of farmers to adopt electricity-saving tricycles and its influencing factors in Dazu District of China. Energy Policy 2022, 167, 113069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiq, M.; Yang, J.; Bashar, S. Impact of personality traits and sustainability education on green entrepreneurship behavior of university students: Mediating role of green entrepreneurial intention. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2024, 14, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, S.; Reynaud, E. Individuals’ sustainability orientation and entrepreneurial intentions: The mediating role of perceived attributes of the green market. Manag. Decis. 2022, 60, 1947–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabowo, H.; Ikhsan, R.; Yuniarty, Y. Drivers of Green Entrepreneurial Intention: Why Does Sustainability Awareness Matter Among University Students? Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asad, M.; Fryan, L.; Shomo, M.I. Sustainable Entrepreneurial Intention Among University Students: Synergetic Moderation of Entrepreneurial Fear and Use of Artificial Intelligence in Teaching. Sustainability 2025, 17, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Wang, Z.; Hu, H.; Fan, Z. Exploring the Formation of Sustainable Entrepreneurial Intentions among Chinese University Students: A Dual Path Moderated Mediation Model. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anghel, G.A.; Anghel, M.A. Green Entrepreneurship among Students Social and Behavioral Motivation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruwaichi, E.; Said, M.; Abdi, I. Entrepreneurship education and business and science students’ green entrepreneurial 999 intentions: The role of green entrepreneurial self-efficacy and environmental awareness. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2024, 22, 100987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Description | Yes | No | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| In my professional training, I have taken subjects related to entrepreneurship. | 85.20% | 14.80% | 100.00% |

| In my professional training, I have taken subjects on sustainable development, ecology, and the environment. | 91.10% | 8.90% | 100.00% |

| Do you feel you have a solid background in entrepreneurship? | 73.10% | 26.90% | 100.00% |

| Have you studied any specific entrepreneurship program with a green or sustainable focus? | 25.30% | 74.70% | 100.00% |

| Would you like to receive training in entrepreneurship with a green or sustainable focus? | 83.40% | 16.60% | 100.00% |

| Description | Being an Employee of a Company | Being a Founder and Working in Your Own Company | Successor in a Family Business | Other, I Don’t Know Yet | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| What was your intention when choosing the career you are currently studying? | 34.5 | 48.6 | 7.0 | 9.9 | 100 |

| What is your intention to choose the career you are currently studying after finishing your studies? | 32.1 | 54.7 | 8.1 | 5.1 | 100 |

| What is your intention regarding the career you are studying five years after finishing your studies? | 24.3 | 65.4 | 8.3 | 2.0 | 100 |

| Cronbach’s Alpha | Compound Reliability (rho_a) | Compound Reliability (rho_c) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Green entrepreneurial intent | 0.923 | 0.929 | 0.942 |

| Green knowledge | 0.878 | 0.886 | 0.916 |

| Green skill development | 0.887 | 0.888 | 0.931 |

| Mastery of green skills | 0.921 | 0.921 | 0.944 |

| Use of green skills | 0.942 | 0.942 | 0.958 |

| Construct | Item | External Loading | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green knowledge | GK1 | 0.805 | 0.878 | 0.733 |

| GK2 | 0.854 | |||

| GK3 | 0.868 | |||

| GK4 | 0.894 | |||

| Mastery of green skills | MGS1 | 0.885 | 0.921 | 0.808 |

| MGS2 | 0.909 | |||

| MGS3 | 0.913 | |||

| MGS4 | 0.888 | |||

| Use of green skills | UGS1 | 0.910 | 0.942 | 0.852 |

| UGS2 | 0.926 | |||

| UGS3 | 0.941 | |||

| UGS4 | 0.915 | |||

| Green skill development | GSD1 | 0.932 | 0.887 | 0.818 |

| GSD2 | 0.939 | |||

| GSD3 | 0.839 | |||

| Green entrepreneurial intent | GEI1 | 0.861 | 0.923 | 0.765 |

| GEI2 | 0.893 | |||

| GEI3 | 0.877 | |||

| GEI4 | 0.888 | |||

| GEI5 | 0.854 |

| Green Entrepreneurial Intent | Green Knowledge | Green Skill Development | Mastery of Green Skills | Use of Green Skills | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green entrepreneurial intent | (0.874) | ||||

| Green knowledge | 0.569 | (0.856) | |||

| Green skill development | 0.667 | 0.692 | (0.904) | ||

| Mastery of green skills | 0.555 | 0.816 | 0.646 | (0.899) | |

| Use of green skills | 0.663 | 0.739 | 0.752 | 0.752 | (0.923) |

| Green Entrepreneurial Intent | Green Knowledge | Green Skill Development | Mastery of Green Skills | Use of Green Skills | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green entrepreneurial intent | |||||

| Green knowledge | 0.627 | ||||

| Green skill development | 0.730 | 0.785 | |||

| Mastery of green skills | 0.599 | 0.899 | 0.715 | ||

| Use of green skills | 0.706 | 0.810 | 0.822 | 0.807 |

| Saturated Model | Estimated Model | |

|---|---|---|

| SRMR | 0.047 | 0.068 |

| d_ULS | 0.456 | 0.982 |

| d_G | 0.525 | 0.545 |

| Chi-cuadrado | 2392.213 | 2437.961 |

| NFI | 0.839 | 0.836 |

| R-Squared | Adjusted R-Squared | |

|---|---|---|

| Green entrepreneurial intent | 0.445 | 0.444 |

| Green skill development | 0.565 | 0.565 |

| Mastery of green skills | 0.665 | 0.665 |

| Use of green skills | 0.613 | 0.612 |

| Path (β) Original Sample (O) | Statistics t (|O/STDEV|) | p Values | Comment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green knowledge -> Mastery of green skills | 0.816 | 43.108 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| Green knowledge -> Use of green skills | 0.377 | 7.198 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| Mastery of green skills -> Use of green skills | 0.447 | 8.480 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| Use of green skills -> Green skill development | 0.752 | 29.516 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| Green skill development -> Green entrepreneurial intent | 0.667 | 21.363 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| Original Sample (O) VIF | Sample Mean (M) | 2.5% | 97.5% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green knowledge -> Mastery of green skills | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Green knowledge -> Use of green skills | 2.986 | 3.019 | 2.441 | 3.530 |

| Green skill development -> Green entrepreneurial intent | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Mastery of green skills -> Use of green skills | 2.986 | 3.019 | 2.441 | 3.530 |

| Use of green skills -> Green skill development | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T-Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green knowledge -> Mastery of green skills | 0.816 | 0.816 | 0.019 | 43.108 | 0.000 |

| Green knowledge -> Use of green skills | 0.374 | 0.377 | 0.052 | 7.198 | 0.000 |

| Green skill development -> Green entrepreneurial intent | 0.667 | 0.666 | 0.031 | 21.363 | 0.000 |

| Mastery of green skills -> Use of green skills | 0.447 | 0.443 | 0.053 | 8.480 | 0.000 |

| Use of green skills -> Green skill development | 0.752 | 0.752 | 0.025 | 29.516 | 0.000 |

| R2 | Adjusted R2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Green entrepreneurial intent | 0.445 | 0.444 |

| Original Sample (O) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T-Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green knowledge -> Mastery of green skills | 1.986 | 0.277 | 7.164 | 0.000 |

| Green knowledge -> Use of green skills | 0.121 | 0.037 | 3.250 | 0.001 |

| Green skill development -> Green entrepreneurial intent | 0.800 | 0.136 | 5.880 | 0.000 |

| Mastery of green skills -> Use of green skills | 0.173 | 0.049 | 3.552 | 0.000 |

| Use of green skills -> Green skill development | 1.300 | 0.209 | 6.208 | 0.000 |

| Q2 Predict | |

|---|---|

| Green entrepreneurial intent | 0.282 |

| Green skill development | 0.457 |

| Mastery of green skills | 0.663 |

| Use of green skills | 0.544 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

García Hernández, Y.; Martínez García, M.D.; Amador Martínez, M.d.L. Structural Equation Model for Assessing Relationship Between Green Skills and Sustainable Entrepreneurial Intentions. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9306. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209306

García Hernández Y, Martínez García MD, Amador Martínez MdL. Structural Equation Model for Assessing Relationship Between Green Skills and Sustainable Entrepreneurial Intentions. Sustainability. 2025; 17(20):9306. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209306

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía Hernández, Yessica, María Dolores Martínez García, and María de Lourdes Amador Martínez. 2025. "Structural Equation Model for Assessing Relationship Between Green Skills and Sustainable Entrepreneurial Intentions" Sustainability 17, no. 20: 9306. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209306

APA StyleGarcía Hernández, Y., Martínez García, M. D., & Amador Martínez, M. d. L. (2025). Structural Equation Model for Assessing Relationship Between Green Skills and Sustainable Entrepreneurial Intentions. Sustainability, 17(20), 9306. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209306