Abstract

The concept of accountability is central to understanding how sustainable corporate governance (SCG) structures shape organizational behavior, legitimacy, and firm performance in the pursuit of sustainability goals. While widely invoked, accountability is often treated inconsistently across governance contexts—oscillating between technical compliance and ethical legitimacy. This paper provides a structured conceptual review of how accountability is framed and operationalized within sustainability governance, with a specific focus on its implications for sustainable performance, corporate sustainability strategies, and governance effectiveness. Based on a qualitative analysis of thirteen peer-reviewed articles published between 2006 and 2025, the study identifies three dominant conceptual clusters: compliance-oriented, legitimacy-oriented, and hybrid approaches. Each cluster reflects different accountability logics and governance mechanisms—ranging from ESG metrics and sustainability reporting frameworks to participatory forums and stakeholder engagement processes that support sustainable development. The article synthesizes theoretical contributions from institutional theory, stakeholder theory, and deliberative democracy to explore how accountability serves as a bridge between formal governance mechanisms and legitimacy claims. A conceptual framework is proposed to illustrate the tensions and complementarities between compliance-driven and legitimacy-driven governance models in sustainability contexts. By deepening the theoretical understanding of accountability in corporate sustainability, this review contributes to the literature on ESG governance, social and environmental reporting, and the legitimacy–performance nexus in corporate settings. The findings offer a foundation for advancing more inclusive, transparent, and sustainability-oriented corporate governance practices in response to global sustainability challenges and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

1. Introduction

The governance of sustainability has emerged as a central concern for scholars and practitioners seeking to respond to the escalating ecological, social, and economic crises of the twenty-first century. Defined broadly, sustainability governance encompasses the institutions, rules, actors, and practices that shape collective efforts toward sustainable development across multiple levels and sectors [1]. It reflects an evolution from traditional, state-centered regulation to more dynamic and hybrid systems involving public, private, and civil society actors [2]. This shift has prompted a corresponding rethinking of accountability—who governs, on what authority, and to whom they are answerable.

Accountability is a normative pillar of good governance. Bovens [1] defines it as a relationship in which an actor is obliged to explain and justify conduct to a forum with the power to assess and sanction. Reporting frameworks and disclosure metrics often reinforce a compliance-oriented view of accountability [3,4]. We also distinguish between sustainability, as an organizational and governance paradigm oriented toward long-term viability, and sustainable development, as the broader societal agenda articulated by the United Nations’ SDGs. This distinction ensures conceptual precision when situating corporate governance debates within wider sustainability transitions.

While accountability is frequently invoked in sustainability governance, the literature remains fragmented across compliance- and legitimacy-oriented framings, with limited attempts to systematically integrate them. This study addresses this gap by mapping these conceptual approaches and proposing a relational framework that links compliance, legitimacy, and hybrid logics of accountability in the context of sustainable corporate governance.

Though this study focuses on accountability, it is important to delimit it from closely related concepts. Responsibility refers to the substantive duties and roles assigned to actors; liability denotes the legal enforceability of obligations; and accountability is the relational process whereby actors must justify their conduct to relevant forums empowered to sanction or validate them. Clarifying these distinctions strengthens the conceptual background and avoids terminological ambiguity.

Suchman [2] famously distinguishes between pragmatic, moral, and cognitive legitimacy, arguing that institutions gain support not just by following rules but by resonating with broader values and expectations. In the context of sustainability, this insight is crucial: governance systems may comply with technical standards while failing to earn the trust or consent of affected stakeholders.

This disconnect is especially salient in emerging systems of non-state, market-driven governance (NSMD), such as certification schemes, ESG reporting, and voluntary sustainability standards. These systems often operate under the assumption that formal compliance mechanisms can substitute for traditional democratic legitimacy [5]. However, as Fox [4] notes, transparency does not guarantee accountability; information must be actionable, institutions must be responsive, and forums for redress must exist. These tensions have led some authors to advocate for participatory, deliberative, and value-driven models of accountability, particularly in fields such as environmental justice, urban sustainability, and global commodity governance [6,7].

Recent scholarship has also expanded the debate by linking accountability to broader sustainability regulations and industry practices. For instance, D’Adamo et al. [8] analyze accountability mechanisms in the circular economy of the fashion sector, Balcerzak et al. [9] examine the EU’s regulation of sustainable investment to address greenwashing, Pelikánová & Rubáček [10] discuss accountability through transparency requirements in non-financial statements, and Hála et al. [11] investigate generational determinants of CSR support. Although these contributions were not included in the 13-article conceptual corpus of this review, they provide complementary perspectives that reinforce the timeliness of our analysis.

Despite growing interest, the literature on accountability in sustainability governance remains theoretically fragmented and empirically dispersed. Few studies have systematically analyzed how accountability is framed, operationalized, and legitimated across different governance contexts. The result is a landscape where “accountability” is invoked frequently but understood unevenly—sometimes as control, sometimes as transparency, sometimes as democratic responsiveness.

In this context, the present article provides a structured conceptual review of the literature at the intersection of sustainability governance, accountability, and legitimacy. Drawing on a curated corpus of 13 peer-reviewed articles published between 2006 and 2025, we identify and analyze the dominant ways in which accountability is conceptualized and linked to compliance or legitimacy-oriented governance. Rather than offering a quantitative bibliometric analysis, this study adopts a qualitative, theory-driven approach, with the aim of synthesizing conceptual trajectories and identifying gaps and tensions in the field.

Specifically, the paper seeks to answer the following research questions:

- How is accountability framed in sustainability governance through compliance-, legitimacy-, and hybrid-oriented approaches?

- What tensions and complementarities emerge among these approaches?

- How can these insights advance more integrative frameworks for sustainability governance?

By synthesizing institutional theory, stakeholder theory, and deliberative democracy, this study provides a novel conceptual framework that moves beyond fragmented typologies.

The article proceeds as follows. Section 2 describes the methodology used to select and analyze the corpus of articles. Section 3 presents the key conceptual clusters that emerged from the review. Section 4 discusses theoretical implications and tensions. Section 5 outlines a framework for future research. Finally, Section 6 concludes by reflecting on the need to reconceptualize accountability as a bridge between institutional integrity and democratic legitimacy.

2. Methodology

This study adopts a structured conceptual review approach to examine how accountability is theorized and operationalized within the field of sustainability governance. Rather than employing a purely quantitative bibliometric method, the research design reflects the need for a focused, theory-driven analysis of a well-defined scholarly niche: the intersection of accountability, compliance, and legitimacy in sustainability governance.

A systematic search was conducted using the Scopus database, widely recognized for its comprehensive coverage of peer-reviewed publications in the social sciences and environmental studies. Scopus was chosen due to its comprehensive coverage of peer-reviewed journals in social sciences, business, and environmental studies, which represent the primary domains of sustainability governance research. While the use of a single database may exclude some publications, Scopus is considered sufficiently broad to capture the core debates in this interdisciplinary field. The search strategy was developed to isolate academic works that address accountability within the context of sustainability governance, particularly in relation to issues of compliance and legitimacy.

The search query used in the Scopus “Advanced Search” function was the following:

- (TITLE-ABS-KEY(“sustainability governance”)) AND

- (TITLE-ABS-KEY(“accountability” OR “transparency” OR “responsibility”)) AND

- (TITLE-ABS-KEY(“legitimacy” OR “compliance”))

The query was limited to peer-reviewed journal articles written in English and published between 2006 and 2025. The search date was 28 July 2025. The initial search returned 127 records. After removing duplicates and conducting a title and abstract screening, 89 records were excluded because they did not engage conceptually with accountability or legitimacy in sustainability governance. A further 25 records were excluded during full-text assessment due to limited analytical focus or insufficient connection with governance debates. Ultimately, 13 articles met the inclusion criteria and were retained for detailed analysis.

Duplicates, off-topic results, and articles without conceptual engagement with accountability or legitimacy were excluded. No additional filters (e.g., subject area or document type) were applied beyond peer-reviewed research articles.

To ensure conceptual depth and relevance, articles were selected based on the following inclusion criteria:

- Explicit engagement with the concept of accountability in sustainability governance;

- Theoretical or empirical discussion of legitimacy, compliance, or both;

- Focus on governance in public, private, or hybrid institutional settings;

- Analytical clarity and contribution to understanding governance mechanisms or models;

- Availability of the full text for in-depth reading and coding.

These criteria reflect the study’s aim of producing a qualitative, interpretive synthesis of conceptual framings, not a comprehensive survey of the broader field.

The selected articles were reviewed in full and analyzed using an inductive, thematic coding strategy. Attention was given to how each article

- Defines and frames accountability;

- Associates accountability with either compliance mechanisms (e.g., audits, standards, performance indicators) or legitimacy-based processes (e.g., participatory governance, stakeholder inclusion);

- Employs or references theoretical frameworks (e.g., institutional theory, stakeholder theory, public administration, deliberative democracy);

- Addresses power dynamics, transparency, and responsiveness in governance settings.

For instance, Kolk [5] was coded under compliance-oriented accountability because of its emphasis on reporting frameworks; Miller [12] was coded as legitimacy-oriented due to its focus on participatory governance; and Joseph [13] was classified as hybrid, given its analysis of tensions between donor accountability and citizen responsiveness. A complete coding matrix with the 13 reviewed articles, their assigned cluster, and illustrative excerpts is provided in Appendix A, enhancing transparency and reproducibility.

Although the final corpus is relatively small, its representativeness was ensured by selecting articles that explicitly address accountability in sustainability governance and that draw on diverse governance contexts (corporate, public, hybrid). The selected works capture the major theoretical debates in the field, including compliance-oriented accountability, legitimacy-oriented accountability, and hybrid approaches. This strategy ensures that the review covers the central conceptual trajectories without diluting analytical focus.

Based on this review, the articles were grouped into three emergent conceptual clusters:

- Compliance-oriented accountability: emphasizing control, monitoring, and standardization;

- Legitimacy-oriented accountability: emphasizing participation, trust, and discursive justification;

- Hybrid and tension-based approaches: highlighting the co-existence and conflict between compliance and legitimacy.

Each cluster was developed iteratively, drawing on patterns in language, theoretical orientation, and governance logic. The resulting structure enables a comparative reading of how accountability is embedded and contested within sustainability governance discourses.

The decision to limit the corpus to 13 articles is not a methodological weakness but a reflection of the narrow scope and conceptual precision of the study. This narrow corpus ensures conceptual depth and captures major debates across corporate, public, and hybrid governance contexts. While large-scale bibliometric reviews rely on hundreds of documents, this research intentionally targets a highly specific intersection of themes. This focused scope was deliberately chosen to allow conceptual precision in distinguishing compliance-, legitimacy-, and hybrid-oriented framings. To address concerns of coverage, we integrated recent contributions such as The European Union’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) enhances transparency and accountability in corporate sustainability practices (2025); Navigating CSRD reporting: Turning compliance into sustainable development with science-based metrics. the IFRS S1 & S2 standards under ISSB (2023) and ISSB: Global Momentum for Sustainability Reporting (Anthesis Group, 2023/24). The approach enables a depth of analysis and conceptual clarity that would be difficult to achieve with a broader dataset. Nevertheless, the results are not intended to be exhaustive, but exploratory and theory-generating, providing a foundation for future empirical and conceptual investigations.

3. Results: Conceptual Clusters of Accountability in Sustainability Governance

The 13 selected articles reveal a multidimensional understanding of accountability in sustainability governance. Through an inductive thematic analysis, three conceptual clusters were identified: compliance-oriented accountability, legitimacy-oriented accountability, and hybrid/tension-based approaches. Each cluster reflects distinct assumptions about the purpose of accountability, its operational mechanisms, and its sources of legitimacy.

The following analysis is structured around these three clusters, which are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Conceptual clusters of accountability in sustainability governance.

3.1. Compliance-Oriented Accountability

This cluster includes studies that approach accountability primarily as a technical, rule-based mechanism focused on enforcing compliance, enhancing transparency, and aligning actor behavior with established norms or standards. Within this perspective, accountability is typically measured through standardized instruments, such as ESG indicators, sustainability reporting frameworks, auditing procedures, and external performance metrics.

Theoretical orientation: The compliance-oriented view is grounded in traditions of principal-agent theory, new public management, and regulatory governance. It conceives accountability as a form of answerability to a superior entity (regulators, boards, investors), where performance is monitored and evaluated against predefined criteria. Legitimacy in this cluster is derived from rule adherence, procedural transparency, and data-driven reporting rather than stakeholder inclusion or ethical justification.

This framing echoes what Bovens [1] calls “accountability as control”, and what Fox [4] critiques as “transparency without teeth”—mechanisms that inform but do not necessarily empower.

Empirical illustrations: Several articles in the corpus exemplify this model. Kolk [5] for instance, analyzes sustainability and CSR reports of multinational corporations, concluding that while reporting practices have become increasingly standardized (e.g., via GRI frameworks), they often serve reputational functions more than democratic ones [5]. ESG disclosures enhance a company’s appearance of accountability, but rarely open channels for stakeholder engagement or institutional responsiveness.

Dabbous and Tarhini [14] explore ESG accountability in the banking sector and highlight how environmental disclosures are structured primarily for investor expectations, reinforcing formal compliance while downplaying qualitative stakeholder narratives [10]. These mechanisms serve as performance proxies, fulfilling regulatory and reputational obligations more than fostering democratic transparency.

Joseph [13] (presents a particularly interesting case from public governance, showing how urban mayors employ accountability tools—such as dashboards, audits, and performance contracts—not to involve citizens but to satisfy national or international donors. Here, accountability becomes managerial, facilitating top-down pressure without downward responsiveness [9].

Other studies in this cluster [16,17] focus on governance codes, institutional standards, and formal compliance with ESG-related best practices, reaffirming a view of accountability as institutional obligation, not ethical dialogue.

Governance instruments and legitimacy source: Across these studies, the most common instruments include:

- Sustainability and ESG reporting frameworks (e.g., GRI, SASB);

- Audit and assurance systems;

- Codes of conduct and corporate governance guidelines;

- Quantitative performance metrics (KPIs, SDG indicators).

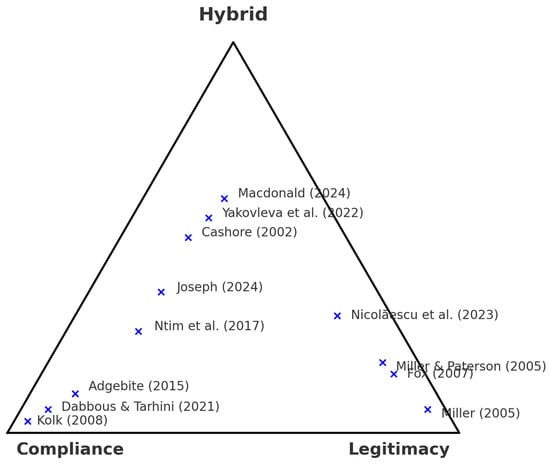

Legitimacy, in this cluster, is linked to objective measurability, institutional transparency, and rule conformity. As shown in Table 2 and visualized in Figure 1, papers such as Kolk [5], Dabbous & Tarhini [14] and Adegbite [16] fall clearly into this paradigm.

Table 2.

Comparative overview of the 13 reviewed articles.

Figure 1.

Conceptual positioning of reviewed articles within the accountability framework [4,5,7,12,13,14,15,16,18,19,20].

Critiques and challenges: While such mechanisms enhance formal transparency, they risk reducing accountability to a checklist of technical outputs, vulnerable to symbolic use or greenwashing. As Fox [4], warns, “reporting without responsiveness” may increase information without increasing institutional answerability [2].

Moreover, these systems often prioritize external investor or donor audiences rather than affected communities, reinforcing top-down legitimacy structures that may obscure underlying social or ecological harms.

Compared to legitimacy-oriented models, compliance-oriented approaches prioritize rule adherence and measurable outputs. While this ensures procedural clarity, it often sidelines stakeholder inclusion, creating tensions between procedural efficiency and democratic responsiveness.

3.2. Legitimacy-Oriented Accountability

This cluster groups studies that conceptualize accountability not as a compliance obligation, but as a relational, participatory, and dialogic process. These contributions critique the technocratic focus on metrics and reporting, instead emphasizing ethical justification, stakeholder engagement, and responsiveness as the core of meaningful accountability in sustainability governance.

Theoretical orientation: This view aligns with deliberative democratic theory, stakeholder theory, and normative institutionalism, where legitimacy is not automatically granted through formal compliance, but must be earned and continuously reaffirmed through socially embedded processes. Accountability is thus seen as upward, downward, and horizontal, with legitimacy emerging from perceived fairness, moral credibility, and discursive justification [2].

Suchman’s [2] typology of legitimacy—pragmatic, moral, and cognitive—provides an essential theoretical lens here [2]. In this cluster, the focus lies on moral legitimacy, which depends on normative alignment with stakeholder values, and pragmatic legitimacy, based on active responsiveness to those stakeholders’ needs.

Empirical illustrations: Miller [12] is a cornerstone for this perspective. In his analysis of global environmental governance, he argues that efforts to improve accountability must go beyond formal mechanisms and address inclusion, deliberation, and justice [12]. He emphasizes the democratization of governance structures, proposing that legitimacy arises when marginalized voices gain representation in environmental decision-making.

Macdonald [15] critiques the overreliance on technocratic tools in sustainable commodity governance. Through empirical examples in palm oil and cocoa value chains, she shows how certification and sustainability standards often reinforce elite-centric legitimacy, sidelining local knowledge and agency. She calls for a shift from compliance-based to narrative-based accountability, where affected communities help define what “sustainability” and “accountability” mean [15].

Fox [4] deepens this critique by distinguishing between transparency (passive information release) and accountability (active responsiveness and enforceability) [4]. He highlights the need for feedback loops, community sanction mechanisms, and institutional capacity to process and act on stakeholder input—essential components of democratic accountability.

Bendell [6] further problematizes CSR and sustainability initiatives that lack genuine stakeholder dialogue. He asserts that accountability cannot be imposed externally, but must be grounded in legitimate relationships, informed consent, and procedural justice [6].

Governance instruments and legitimacy source: Articles in this cluster emphasize:

- Participatory mechanisms (consultations, citizen forums, stakeholder panels);

- Deliberative spaces for norm negotiation;

- Feedback and grievance systems;

- Context-sensitive indicators shaped by affected groups.

Legitimacy is constructed, not presumed, and accountability is a two-way relationship, not a unilateral obligation. This cluster also questions the assumption that transparency equals legitimacy, showing that voice, agency, and contestation are just as essential.

From the comparative Table 2 and the conceptual positioning in Figure 1, core articles in this cluster include Miller [12] Fox [4], Bendell [6] and to a significant extent, Macdonald [15].

Critiques and challenges: Although ethically compelling, legitimacy-based accountability is resource-intensive and institutionally demanding and may generate deliberative fatigue or political resistance—especially in settings where hierarchical or investor-driven structures dominate. Moreover, as Fox [4] notes, transparency reforms are often decoupled from mechanisms of answerability or sanctions, limiting their transformative potential [4].

In contrast to compliance-oriented logics, legitimacy-oriented approaches emphasize moral justification and participation, but they often face challenges of feasibility and implementation. These tensions pave the way for hybrid forms of accountability, where compliance and legitimacy interact in complex ways.

3.3. Hybrid and Tension-Based Approaches

This third cluster captures articles that problematize the dichotomy between compliance- and legitimacy-oriented models. Rather than fully aligning with one paradigm, these studies recognize that accountability mechanisms in sustainability governance are often hybrid, dynamic, and conflictual. They expose the tensions and trade-offs inherent in governance arrangements that attempt to be both procedurally robust and normatively legitimate.

Theoretical orientation: These works draw on institutional complexity theory, multi-level governance, and critical policy analysis. Rather than assuming convergence between legitimacy and compliance, they focus on the frictions between rule adherence and contextual legitimacy, highlighting how power asymmetries, contested norms, and conflicting stakeholder expectations shape accountability practices.

Suchman’s [2] notion of cognitive legitimacy—legitimacy derived from taken-for-granted institutional forms—offers a useful lens here [2]. In hybrid governance systems, actors may conform to recognizable forms of accountability (e.g., certifications, reporting standards) not because they are effective, but because they are perceived as necessary to maintain legitimacy in complex environments.

Empirical illustrations: Macdonald [15] is central in this cluster. Her study of global commodity chains shows how sustainability certifications and accountability systems, though formally robust, often fail to gain local legitimacy or produce equitable outcomes. These mechanisms become what she terms “apolitical accountability”—procedures that signal control without addressing deeper social tensions [15].

Cashore [7] provides a seminal theoretical contribution through his analysis of non-state market-driven (NSMD) governance in the forestry sector. He demonstrates how these systems gain rule-making authority through market credibility and third-party audits, despite lacking public, democratic legitimation. This introduces a paradox: non-state systems demand accountability but are not accountable to democratic publics [7].

Joseph [13], discussed earlier, illustrates how urban governance actors must navigate competing accountabilities—to funders, citizens, political elites, and performance regimes. The result is a fragmented accountability space, where actors comply selectively and strategically, often reinforcing instrumental legitimacy while eroding democratic ties.

Ntim et al. [19] and Yakovleva et al. [20] also identify hybrid accountability patterns. Ntim focuses on corporate board structures, showing how ESG frameworks create tensions between fiduciary duties and stakeholder expectations. Yakovleva et al., examining the mining sector, reveal how formal consultation mechanisms coexist with deep legitimacy deficits due to weak enforcement and cultural dissonance [19,20].

Mechanisms and accountability logics: Common elements across this cluster include:

- Coexistence of technical compliance and informal legitimacy claims;

- Strategic use of accountability tools to satisfy divergent audiences;

- Institutional bricolage, where governance actors combine and adapt tools based on political context.

The reviewed articles show that hybrid systems often pursue legitimacy through familiar forms (e.g., audit, reporting), even when these fail to deliver meaningful accountability on the ground.

Implications and analytical value: This cluster contributes theoretical depth by refusing simplistic categorizations. It acknowledges that accountability is never neutral, and that governance systems operate under multiple, often competing logics. Figure 1 illustrates this cluster’s position near the center of the triangle—occupying the conflict zone between control and legitimacy.

Articles in this category e.g., [7,13,15,20] serve as a bridge, encouraging a more nuanced understanding of how accountability is structured, resisted, and transformed in complex sustainability settings.

Taken together, these clusters address RQ1 and RQ2 by showing how accountability is framed through compliance, legitimacy, and hybrid logics and by revealing the complementarities and conflicts that emerge when these approaches coexist in sustainability governance.

4. Discussion: Reframing Accountability Between Compliance and Legitimacy

The conceptual clusters identified in Section 3 reveal three distinct but overlapping approaches to accountability in sustainability governance. These models reflect deeper normative and institutional tensions around how authority is exercised, justified, and evaluated in complex governance systems. This section discusses the implications of these clusters, synthesizes the trade-offs and complementarities among them, and proposes an integrative framework to inform future theorization and practice.

4.1. Three Logics of Accountability: Trade-Offs and Overlaps

The compliance-oriented model views accountability as a function of rule adherence, performance metrics, and formal transparency mechanisms [3,5,10]. Its strength lies in its operational clarity and institutional enforceability, particularly in corporate and public-sector contexts where auditability and comparability are valued. However, its narrow focus on output measures and technocratic instruments risks excluding normative and participatory dimensions of accountability [4,15].

In contrast, the legitimacy-oriented approach emphasizes moral justification, deliberative participation, and stakeholder responsiveness [6,12]. It aligns with democratic theory and critiques top-down and investor-centric models. Yet these approaches may lack implementation feasibility, especially in transnational or resource-constrained settings [19].

Hybrid approaches acknowledge that real-world governance often involves institutional bricolage—the adaptive combination of multiple, and sometimes contradictory, accountability mechanisms. As shown in Joseph [13] and Yakovleva et al. [20], actors navigate fragmented accountabilities to different constituencies [e.g., donors vs. citizens], creating hybrid systems that may simultaneously empower and exclude [13,20].

Unlike Bovens’ [1] notion of accountability as control, Suchman’s [2] legitimacy typology, or Fox’s [4] transparency–accountability cycle, the framework proposed here integrates these strands into a relational model. It advances the literature by conceptualizing accountability not as a static design principle but as a dynamic balance of instrumental credibility, moral alignment, and reflexive adaptability.

These dynamics are synthesized in Table 3, which maps the tensions and complementarities among the three approaches.

Table 3.

Comparative logics of accountability in sustainability governance.

Greenwashing persists because compliance tools prioritize external visibility over stakeholder responsiveness; tokenism emerges where legitimacy mechanisms exist formally but lack enforcement.

While participatory systems are often portrayed as normatively desirable, they may also experience legitimacy failures, such as elite capture or deliberative fatigue. Likewise, hybrid systems may generate accountability overload, where competing demands create institutional ambiguity. These counterpoints underscore the need for safeguards, including streamlined reporting requirements and clearer stakeholder mandates.

Practically, this framework can guide governance reforms in concrete domains. For example, on corporate boards, it suggests balancing ESG reporting with stakeholder engagement; in ESG disclosure systems, it points to reflexive mechanisms that adapt to evolving sustainability norms; and in participatory forums, it highlights the importance of linking deliberation to enforceable outcomes.

4.2. Theoretical Integration: Towards a Relational View

Unlike Bovens’ [1] accountability-as-control, Suchman’s [2] legitimacy typology, or Fox’s [4] transparency–accountability cycle, our framework integrates these strands by positioning accountability as a dynamic balance of instrumental credibility, moral alignment, and reflexive adaptability.

To reconcile these tensions, we propose an integrative framework that redefines accountability as a relational and dynamic governance function, rather than a fixed set of tools or outcomes. Drawing on Suchman’s legitimacy typology [2] and Fox’s accountability cycle [1], the framework identifies three core dimensions that effective accountability systems must balance:

- Instrumental credibility (compliance logic): Are actors monitored and evaluated using reliable criteria?

- Moral alignment (legitimacy logic): Are decisions ethically justified and accepted by affected groups?

- Reflexive adaptability (hybrid logic): Can institutions navigate conflicts, update mechanisms, and remain responsive to evolving norms?

This triadic model is visualized in Figure 2, which situates accountability mechanisms across a triangular space defined by these three poles.

Figure 2.

Accountability dynamics across compliance, legitimacy, and reflexivity.

The triangle shows each approach as a vertex. Real-world governance systems often position themselves inside the triangle, moving between logics based on institutional context, power relations, and stakeholder pressures.

In corporate boards, the framework highlights the need to balance ESG reporting with genuine stakeholder engagement. In ESG disclosure systems, it encourages reflexive mechanisms that adapt to evolving sustainability norms. In participatory forums, it underscores the importance of linking deliberation to enforceable outcomes.

Recent contributions also emphasize the challenges of accountability in multi-level governance settings, where competing forums complicate both compliance and legitimacy dynamics [13].

This study advances beyond Bovens [1], Suchman [2], and Fox [4] by integrating their insights into a relational model that explicitly addresses the interplay of compliance, legitimacy, and reflexivity. The unique contribution lies in reframing accountability not as a static mechanism but as a relational and dynamic governance function that can inform sustainability reforms.

4.3. Analytical and Practical Implications

This synthesis generates several implications for research and practice:

- For researchers, accountability should be conceptualized not as a single norm or mechanism but as a dynamic field of negotiation among actors with different expectations and powers [20]. Future studies should focus on how accountability logics are translated, resisted, or reinterpreted across sectors and cultures.

- For practitioners, especially in sustainability governance bodies, the key challenge lies in designing accountability systems that are both procedurally robust and normatively legitimate. This requires moving beyond compliance checklists toward reflexive governance—embedding learning loops, grievance mechanisms, and deliberative spaces that evolve over time [8,16].

- For policy designers, hybrid systems must be assessed not only for technical efficacy but for their ability to empower marginalized stakeholders, challenge existing power asymmetries, and foster meaningful institutional trust [19].

The applicability of the triadic framework is necessarily bounded by sectoral and geographical contexts. For example, accountability dynamics in extractive industries differ markedly from those in financial reporting or transnational certification systems. Similarly, governance practices on European Union corporate boards contrast with those in emerging economies or indigenous governance systems. These contextual variations highlight the limits of transferability and call for future empirical studies that test the framework across diverse industries and regions.

Beyond the selected corpus, complementary studies illustrate how accountability is operationalized in different regulatory and sectoral domains. D’Adamo et al. [8] highlight accountability in ESG assurance through circular economy practices, Balcerzak et al. [9] stress the role of EU financial disclosure regulation in curbing greenwashing, Pelikánová & Rubáček [10] reflect on the limits of sanctioning transparency in corporate reporting, and Hála et al. [11] provide evidence of the societal and generational determinants of CSR support. These perspectives, while outside the structured conceptual sample, extend the external validity of our findings and confirm the relevance of the compliance–legitimacy–hybridity framework across diverse governance settings.

The evolving legal framework in the European Union further contextualizes accountability debates. The transition from the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD) to the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), together with the proposed Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) and the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS), significantly reshapes compliance and legitimacy dynamics in corporate governance. These regulatory shifts reinforce the timeliness of revisiting accountability in sustainability governance.

5. Framework for Future Research

The preceding analysis revealed three dominant conceptual orientations—compliance, legitimacy, and hybrid approaches—that structure the field of accountability in sustainability governance. While these paradigms provide valuable insights, they also expose theoretical blind spots, empirical tensions, and normative challenges. To move the field forward, we propose a future research agenda articulated along three core trajectories: integration, reflexivity, and contextualization (Table 4).

Table 4.

Key research directions for advancing accountability in sustainability governance.

5.1. Integration: Beyond the Compliance–Legitimacy Divide

Many studies remain locked into dichotomous framings of accountability—either as technical control or ethical responsiveness. Yet in practice, most governance settings involve hybrid forms where formal and informal mechanisms interact [8,14,15]. Future research should thus explore how actors strategically combine or prioritize different accountability modes depending on political pressures, institutional mandates, or legitimacy demands.

This calls for theoretical work on institutional bricolage and governance hybridity [7,16], including how tensions between vertical (top-down) and horizontal (peer or stakeholder) accountability are managed. Methodologically, longitudinal and multi-level studies could illuminate how hybrid systems stabilize, fail, or evolve over time.

Promising contexts for integration include financial reporting standards, extractive industry governance, and transnational certification systems such as those for palm oil and cocoa.

5.2. Reflexivity: Accountability as a Dynamic Process

Accountability is often framed as a fixed structure—audits, reports, metrics—but recent work urges a view of accountability as dynamic, adaptive, and relational [4,8]. Especially in complex or contested environments, effective governance requires not just information disclosure but capacity for institutional learning, responsiveness, and course correction.

Building on theories of deliberative democracy and institutional reflexivity [21,22], scholars can examine how legitimacy is not only granted but continuously negotiated and re-earned, particularly in transnational or post-colonial contexts. Case studies might track how institutions respond to feedback loops or legitimacy crises over time.

Methodologically, longitudinal case studies and comparative institutional analyses are particularly suited to examining how accountability mechanisms adapt to feedback and crises over time.

Future studies could operationalize the compliance–legitimacy trade-off using measurable indicators. For example, compliance can be proxied through ESG disclosure indices, audit frequency, and assurance quality; legitimacy can be assessed through stakeholder feedback loops, grievance mechanisms, and participation rates; and reflexivity can be tracked through institutional learning processes and adaptive policy changes. A concise case study or an illustrative vignette could empirically demonstrate how organizations balance these three dimensions over time.

5.3. Contextualization: Cultural and Political Specificity

Finally, universalist models of “good governance” risk obscuring how accountability is understood and practiced differently across cultural, political, and epistemic contexts. For example, what constitutes accountability in Indigenous land governance or extractive zones may differ radically from corporate ESG frameworks [12,16].

Future research should engage with normative pluralism, using ethnographic, participatory, and narrative methods to capture the situated practices and contested meanings of accountability in real-world governance systems. This also requires decolonizing dominant frameworks that equate legitimacy with compliance or market efficiency [22,23,24].

Furter, future research could focus on indigenous land governance and postcolonial state–NGO partnerships, where accountability is understood and practiced differently than in mainstream corporate ESG frameworks.

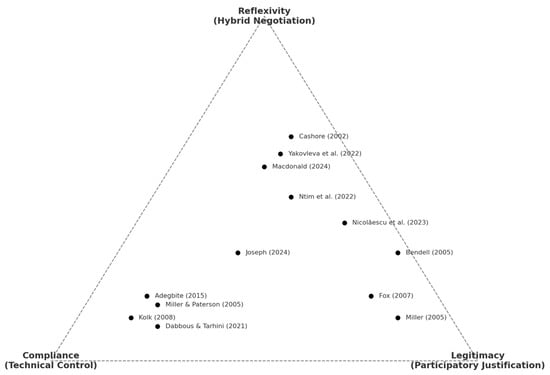

This framework seeks not only to consolidate existing knowledge but to generate theory-informed, empirically grounded, and methodologically diverse research on sustainability governance. It also offers a conceptual map—presented in Figure 3—that positions the reviewed literature within a triangular accountability model integrating compliance, legitimacy, and reflexivity. Figure 3 reports the conceptual mapping of accountability paradigms in sustainability governance.

Figure 3.

Conceptual mapping of accountability paradigms in sustainability governance [4,5,6,7,12,13,14,15,16,18,19,20].

6. Conclusions

Accountability remains one of the most invoked yet ambiguously defined concepts in the field of sustainability governance. As demonstrated in this structured conceptual review, approaches to accountability tend to cluster around three primary logics: compliance-oriented models, emphasizing performance, monitoring, and transparency [5,10,11]; legitimacy-oriented models, focusing on participation, deliberation, and ethical justification [4,6,12]; and hybrid approaches, which recognize the tension or coexistence between procedural control and normative legitimacy [7,8,9].

This article contributes to the literature by clarifying these competing logics and proposing a reflexive framework for future accountability research that emphasizes integration, contextualization, and adaptability. As noted by Fox [4], transparency mechanisms alone are insufficient if not accompanied by institutional responsiveness. Similarly, Cashore [7] illustrates how non-state governance initiatives may achieve symbolic legitimacy without being democratically accountable.

The analysis also highlights that compliance mechanisms often dominate in corporate and institutional settings, where ESG reporting and audit systems are seen as proxies for accountability [5,10,14]. Yet these tools may fall short of building meaningful stakeholder trust or addressing power asymmetries [12,16,23]. On the other hand, legitimacy-oriented approaches, while normatively desirable, require significant institutional resources and face challenges of implementation in hierarchical or investor-driven contexts [6,17,22].

Hybrid models—especially in complex global value chains, urban governance, and natural resource sectors—demonstrate the strategic use of accountability instruments to satisfy multiple, and sometimes conflicting, audiences [8,9,24]. These cases suggest that accountability is best understood not as a fixed design principle but as an evolving, negotiated relationship that is deeply embedded in context.

In sum, this study affirms that accountability in sustainability governance must move beyond dichotomies of compliance and legitimacy. A more fruitful path lies in bridging managerial accountability with democratic legitimacy through systems that are participatory, reflexive, and capable of learning. Rather than asking whether institutions are accountable, future research must interrogate how accountability is constructed, to whom it is directed, and under what normative assumptions it operates.

In response to RQ1–RQ3, this study demonstrates how accountability is differentiated into compliance, legitimacy, and hybrid logics; identifies the tensions among them; and proposes an integrative framework that advances beyond Bovens [1], Suchman [2], and Fox [4]. The unique contribution lies in reframing accountability as a relational and dynamic governance function that can inform both sustainability research and policy reform.

Beyond corporate governance, accountability intersects with adjacent disciplines such as international business, political science, and legal studies. The work of scholars like Rob van Tulder [25] and Ans Kolk [5] highlights how accountability debates are embedded in broader CSR and international business contexts, underscoring the interdisciplinary nature of sustainability governance research.

Despite its contributions, this study has several limitations. First, the reliance on a single database (Scopus) may have excluded relevant publications indexed elsewhere. Second, the relatively small sample size, while adequate for qualitative theory-building, limits the possibility of generalization. Third, the review focuses on conceptual debates rather than empirical validation, which restricts the scope of its practical implications. Future research should therefore expand the dataset through multiple databases, incorporate empirical studies, and examine how different accountability logics operate across varied sustainability governance contexts.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Union—Next Generation EU, Project Title: Innovation, digitalization and sustainability for the diffused economy in Central Italy—VITALITY.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Coding Matrix of Reviewed Articles

| Author(s), Year | Governance Context | Assigned Cluster | Illustrative Excerpt/Rationale |

| Kolk, A. [5] | Corporate sustainability reporting | Compliance | “Multinationals disclose sustainability information primarily through standardized reporting frameworks.” |

| Miller, C. [12] | Global environmental governance | Legitimacy | “Stakeholder participation after WSSD highlights the need for accountability through deliberation.” |

| Joseph, P. [13] | Urban sustainability/donor–citizen dynamics | Hybrid | “Mayors are accountable both to international donors and to local citizens, creating tension between compliance and responsiveness.” |

| Cashore, B. [7] | Forest certification systems | Legitimacy | “Non-state market-driven governance relies on legitimacy from stakeholders rather than state coercion.” |

| Fox, J. [4] | Transparency–accountability debates | Hybrid | “Bridging transparency and accountability requires reflexive mechanisms across multiple scales.” |

| Bovens, M. [1] | Public administration | Compliance | “Accountability as control emphasizes rule-following and sanctions.” |

| Suchman, M. [2] | Organizational legitimacy | Legitimacy | “Distinction between pragmatic, moral, and cognitive legitimacy frames accountability beyond compliance.” |

| Kolk, A. [5] | Climate governance | Hybrid | “Firms balance compliance with standards and legitimacy through stakeholder dialogue.” |

| Dabbous, A. & Tarhini, A. [14] | ESG reporting/corporate governance | Compliance | “Standardized metrics and disclosure are central to accountability.” |

| Macdonald, K. (2024) [15] | Global supply chains | Hybrid | “Accountability operates at multiple levels, balancing compliance demands and legitimacy expectations.” |

| Zadek, S. [26] | CSR accountability | Legitimacy | “Effective accountability requires alignment with societal values and stakeholder engagement.” |

| Fransen, L. [27] | Multi-stakeholder initiatives | Hybrid | “Tensions between technical compliance and participatory legitimacy persist in transnational MSIs.” |

| Gray, R. [22] | Social/environmental accounting | Compliance | “Corporate accountability is primarily expressed through measurable disclosure and auditing practices.” |

References

- Bovens, M. Analysing and Assessing Accountability: A Conceptual Framework. Eur. Law J. 2007, 13, 447–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchman, M.C. Managing Legitimacy: Strategic and Institutional Approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biermann, F.; Betsill, M.; Gupta, J.; Kanie, N.; Lebel, L.; Liverman, D.; Schroeder, H.; Siebenhüner, B. Earth System Governance: A Research Framework. Int. Environ. Agreem. Politics Law Econ. 2010, 10, 277–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, J. The Uncertain Relationship Between Transparency and Accountability. Dev. Pract. 2007, 17, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolk, A. Sustainability, Accountability and Corporate Governance: Exploring Multinationals’ Reporting Practices. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2008, 17, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendell, J. In Whose Name? The Accountability of Corporate Social Responsibility. Dev. Pract. 2005, 15, 362–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashore, B. Legitimacy and the Privatization of Environmental Governance: How Non-State Market-Driven (NSMD) Governance Systems Gain Rule-Making Authority. Governance 2002, 15, 503–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Adamo, I.; Lupi, G.; Morone, P.; Settembre-Blundo, D. Towards the circular economy in the fashion industry: The second-hand market as a best practice of sustainable responsibility for businesses and consumers. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 46620–46633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcerzak, A.P.; MacGregor, R.K.; MacGregor Pelikánová, R.; Rogalska, E.; Szostek, D. The EU regulation of sustainable investment: The end of sustainability trade-offs? Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2023, 11, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelikánová, R.M.; Rubáček, F. Taxonomy for transparency in non-financial statements—Clear duty with unclear sanction. Danub. Law Econ. Soc. Issues Rev. 2022, 13, 173–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hála, M.; MacGregor Pelikánová, R.; Rubáček, F. Negative Determinants of CSR Support by Generation Z in Central Europe: Gender-Sensitive Impacts of Infodemic in ’COVID-19′ Era. Cent. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2024, 13, 89–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C. Democratizing Global Environmental Governance: Stakeholder Democracy after the World Summit on Sustainable Development. Democr. Nat. 2005, 11, 81–99. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, G. Assessing the sustainability and resilience of urban transit: The case of Kochi water metro. In Sustainable and Resilient Supply Chain: Environmental Accounting and Management Focus; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2024; pp. 141–157. [Google Scholar]

- Dabbous, A.; Tarhini, A. Corporate ESG Performance and Accountability: An Empirical Study in the Banking Sector. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2021, 12, 540–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, K. The Politics of Accountability in Global Sustainable Commodity Governance: Dilemmas of Authority in Palm Oil and Cocoa. Glob. Policy 2024, 15, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegbite, E. Good Corporate Governance in Nigeria: Antecedents, Propositions and Peculiarities. Int. Bus. Rev. 2015, 24, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.; Paterson, M. The Governance of Climate Change in the Post-1990 Period. Int. Aff. 2005, 81, 775–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolăescu, E.; Radu, L.D.; Mihăescu, L. Enhancing Institutional Legitimacy in Multi-Level Governance: Challenges for the EU. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntim, C.G.; Soobaroyen, T.; Broad, M.J. Governance structures, voluntary disclosures and public accountability: The case of UK higher education institutions. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2017, 1, 65–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakovleva, N.; Vazquez-Brust, D.A.; Liston-Heyes, C. Accountability and Legitimacy in the Governance of Global Mining: Institutional Challenges and Opportunities. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 180, 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherardi, L.; Linsalata, A.M.; Gagliardo, E.D.; Orelli, R.L. Accountability and reporting for sustainability and public value: Challenges in the public sector. Sustainability 2021, 3, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, R.; Owen, D.; Adams, C. Accounting and Accountability: Changes and Challenges in Corporate Social and Environmental Reporting; Prentice Hall: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bäckstrand, K. Multi-stakeholder Partnerships for Sustainable Development: Rethinking Legitimacy, Accountability and Effectiveness. Eur. Environ. 2006, 16, 290–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashaw, J.L. Accountability and Institutional Design: Some Thoughts on the Grammar of Governance. In Public Accountability: Designs, Dilemmas and Experiences; Dowdle, M., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006; pp. 115–156. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=924879 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Van Tulder, R. Business & the Sustainable Development Goals: A Framework for Effective Corporate Involvement; Erasmus University Rotterdam: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; p. 123. [Google Scholar]

- Zadek, S. Responsible competitiveness: Reshaping global markets through responsible business practices. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2006, 6, 334–348. [Google Scholar]

- Fransen, L. Multi-stakeholder governance and voluntary programme interactions: Legitimation politics in the institutional design of corporate social responsibility. Socio-Econ. Rev. 2012, 10, 163–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).