How and When Entrepreneurial Leadership Drives Sustainable Bank Performance: Unpacking the Roles of Employee Creativity and Innovation-Oriented Climate

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Social Learning Theory (SLT)

2.2. Entrepreneurial Leadership

2.3. Entrepreneurial Leadership and Sustainable Bank Performance

2.4. Entrepreneurial Leadership and Employee Creativity

2.5. Employee Creativity and Sustainable Bank Performance

2.6. The Mediating Role of Employee Creativity

2.7. The Moderating Role of Innovation-Oriented Climate

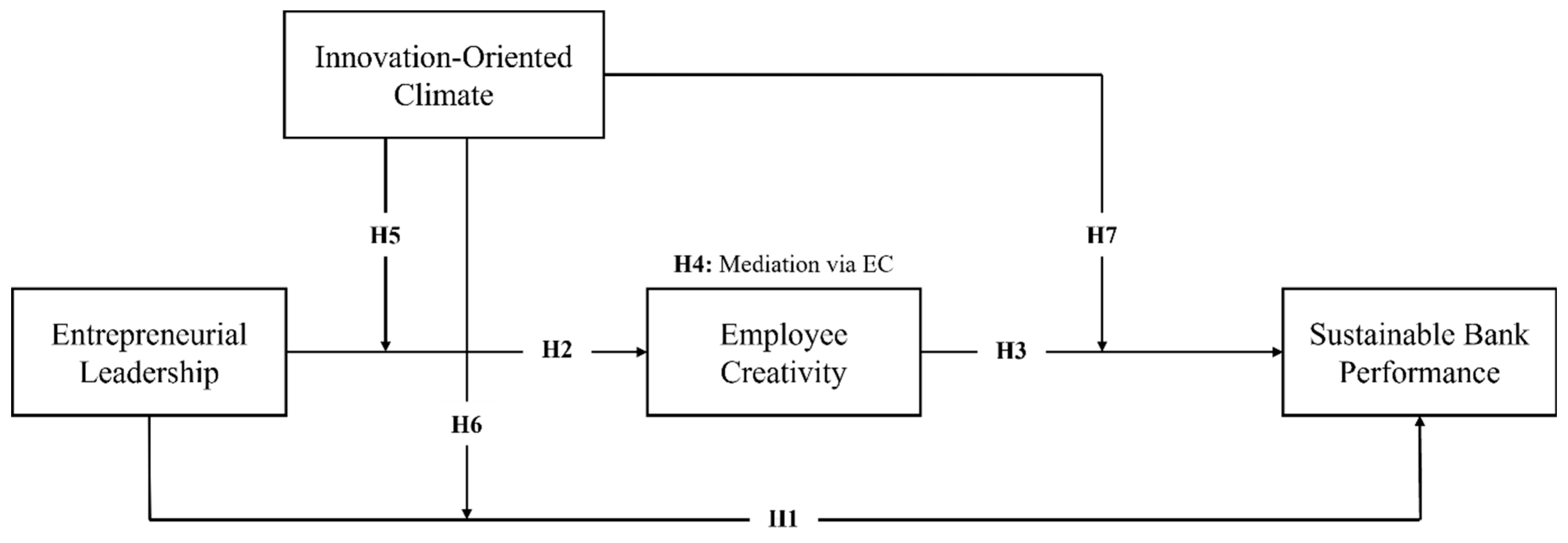

2.8. Research Model

3. Methods

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Data Collection and Procedure

3.3. Measurement Items

3.4. Non-Response Bias

3.5. Common Method Bias

3.6. Analytical Methods

4. Analysis and Results

4.1. Measurement Model Assessment

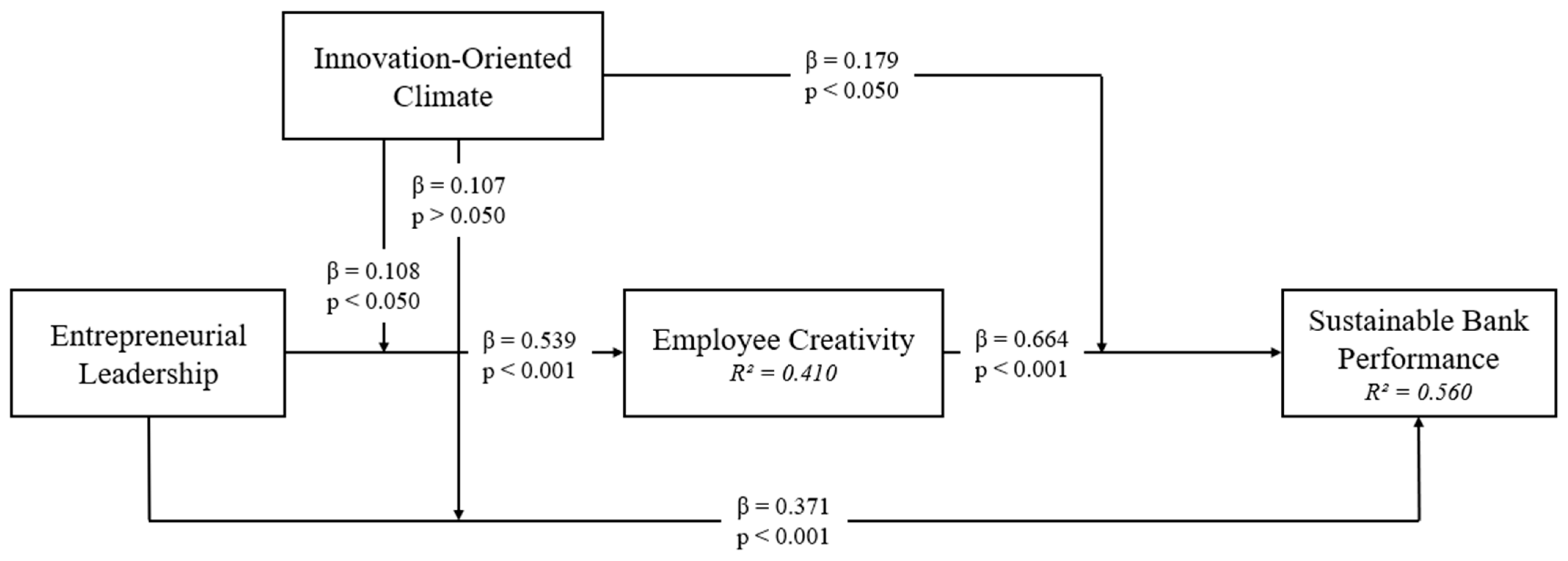

4.2. Hypotheses Testing: Direct and Indirect Effects

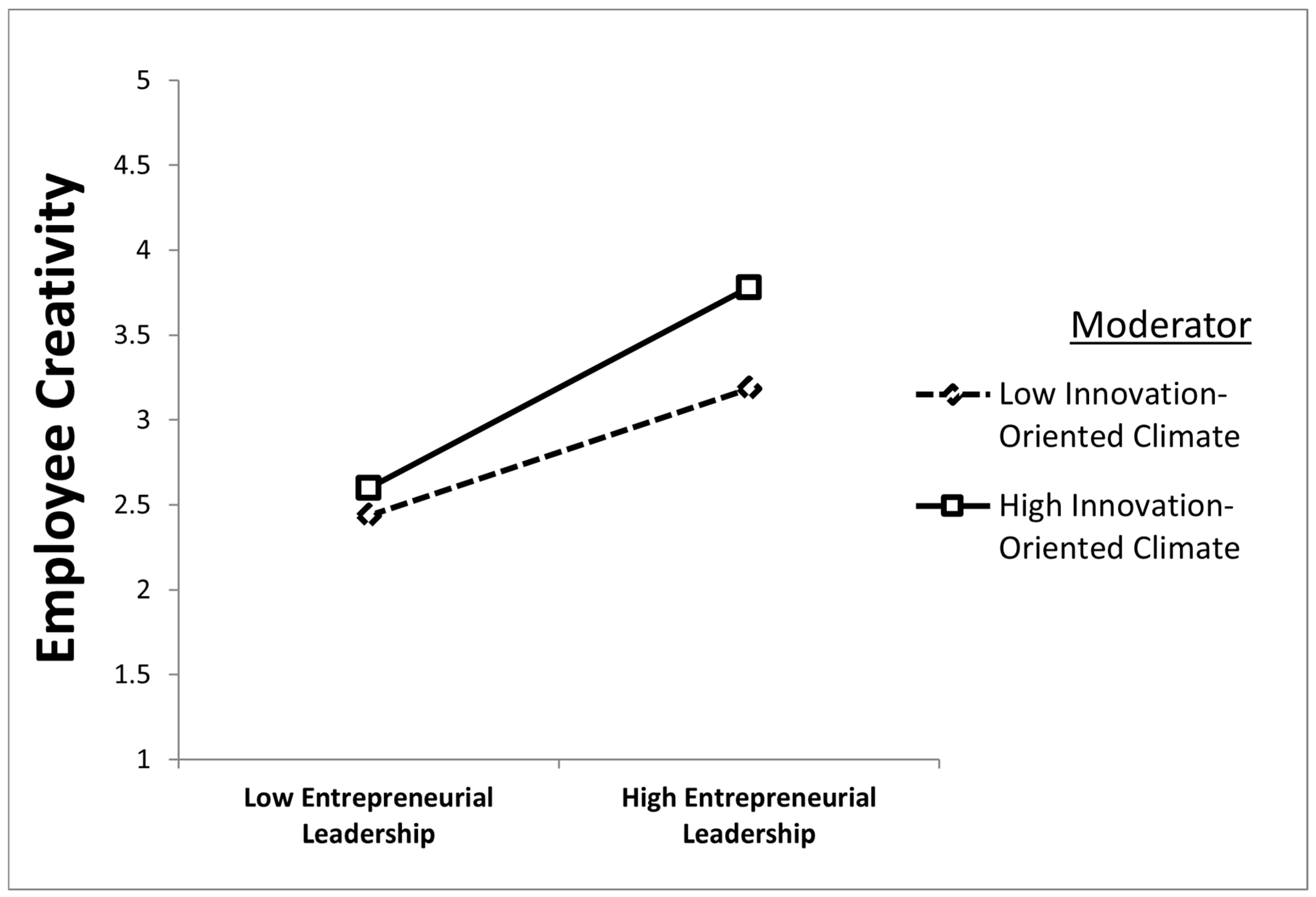

4.3. Hypotheses Testing: Moderating and Conditional Indirect Effects

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Limitations and Direction for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Construct | Measurement Items | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurial Leadership (EL) | 1. My manager often comes up with radical improvement ideas for the products/services we are selling. 2. My manager often comes up with ideas for completely new products/services we could sell. 3. My manager takes risks. 4. My manager has creative solutions to problems. 5. My manager demonstrates a passion for his work. 6. My manager has a vision of the future of our business. 7. My manager challenges and pushes me to act in a more innovative way. 8. My manager wants me to challenge the current ways we do business. | Renko et al. [28] |

| Employee Creativity (EC) | 1. I generate novel but operable work-related ideas. 2. I seek new ideas and ways to solve problems. 3. I identify opportunities for new ways of dealing with work. 4. I demonstrate originality in my work. | Tierney & Farmer [108] |

| Innovation-Oriented Climate (IOC) | 1. The bank provides time and resources for employees to generate, share/exchange, and experiment with innovative ideas/solutions. 2. The bank works in diversely skilled work groups where there is free and open communication among the group members. 3. The employees frequently encounter nonroutine and challenging work that stimulates creativity. 4. The employees are recognized and rewarded for their creativity and innovative ideas. | Oke et al. [109] |

| Sustainable Bank Performance (SBP) | Economic Performance (EP) 1. Provides employment to us and others. 2. Sales growth. 3. Income stability. 4. Return on investment. Social Performance (SO) 1. Ensures basic needs for our family. 2. Enhances our social recognition in society. 3. Improves our empowerment in society. 4. Provides freedom and control. Environmental Performance (EN) 1. Uses utilities in an environment-friendly manner. 2. Produces insignificant waste and emissions. 3. Is concerned about waste management. 4. Is concerned about hygiene factors. | Khan & Quaddus [110] |

References

- Murinde, V.; Rizopoulos, E.; Zachariadis, M. The Impact of the FinTech Revolution on the Future of Banking: Opportunities and Risks. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2022, 81, 102103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Chupradit, S.; Hassan, M.; Soudagar, S.; Shoukry, A.M.; Khader, J. The Role of Technical Efficiency, Market Competition and Risk in the Banking Performance in G20 Countries. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2021, 27, 2144–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkhweildi, M.; Vetbuje, B.; Alzubi, A.B.; Aljuhmani, H.Y. Leading with Green Ethics: How Environmentally Specific Ethical Leadership Enhances Employee Job Performance Through Communication and Engagement. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elansari, H.; Alzubi, A.; Khadem, A. The Impact of United Nations Sustainable Development Goals on Customers’ Perceptions and Loyalty in the Banking Sector: A Multi-Mediation Approach. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djalil, M.A.; Amin, M.; Herjanto, H.; Nourallah, M.; Öhman, P. The Importance of Entrepreneurial Leadership in Fostering Bank Performance. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2023, 41, 926–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.V.; Huynh, H.T.N.; Lam, L.N.H.; Le, T.B.; Nguyen, N.H.X. The Impact of Entrepreneurial Leadership on SMEs’ Performance: The Mediating Effects of Organizational Factors. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahibzada, U.F.; Aslam, N.; Muavia, M.; Shujahat, M.; Rafi-ul-Shan, P.M. Navigating Digital Waves: Unveiling Entrepreneurial Leadership toward Digital Innovation and Sustainable Performance in the Chinese IT Industry. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2024, 38, 474–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, G.; Luu, T.T.; Nguyen, T.T.; Du, T.; Le, L.P. Examining the Effect of Entrepreneurial Leadership on Employees’ Innovative Behavior in SME Hotels: A Mediated Moderation Model. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 102, 103142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrowwad, A.; Abualoush, S.H.; Masa’deh, R. Innovation and Intellectual Capital as Intermediary Variables among Transformational Leadership, Transactional Leadership, and Organizational Performance. J. Manag. Dev. 2020, 39, 196–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyery, A.L.J.; Steyrer, J.M. Transformational Leadership and Objective Performance in Banks. Appl. Psychol. 1998, 47, 397–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M.; Ozturk, A.; Kim, T.T. Servant Leadership, Organisational Trust, and Bank Employee Outcomes. Serv. Ind. J. 2019, 39, 86–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayram, O.; Talay, I.; Feridun, M. Can Fintech Promote Sustainable Finance? Policy Lessons from the Case of Turkey. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzkurt, C.; Kumar, R.; Semih Kimzan, H.; Eminoğlu, G. Role of Innovation in the Relationship between Organizational Culture and Firm Performance: A Study of the Banking Sector in Turkey. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2013, 16, 92–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpkan, L.; Karabay, M.; Şener, İ.; Elçi, M.; Yıldız, B. The Mediating Role of Trust in Leader in the Relations of Ethical Leadership and Distributive Justice on Internal Whistleblowing: A Study on Turkish Banking Sector. Kybernetes 2020, 50, 2073–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alikaj, A.; Ning, W.; Wu, B. Proactive Personality and Creative Behavior: Examining the Role of Thriving at Work and High-Involvement HR Practices. J. Bus. Psychol. 2021, 36, 857–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Ma, E.; Lin, X. Can Proactivity Translate to Creativity? Examinations at Individual and Team Levels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 98, 103034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.N.; Nham, P.T.; Takahashi, Y. The Joint Effect of Value Diversity and Emotional Intelligence on Team Creativity: Evidence from Vietnam. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2024, 20, 3782–3797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stawicki, C.; Krishnakumar, S.; Robinson, M.D. Working with Emotions: Emotional Intelligence, Performance and Creativity in the Knowledge-Intensive Workforce. J. Knowl. Manag. 2022, 27, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.H.; Bai, Y. Leaders Can Facilitate Creativity: The Moderating Roles of Leader Dialectical Thinking and LMX on Employee Creative Self-Efficacy and Creativity. J. Manag. Psychol. 2020, 35, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, F.; Su, Y.; Qi, M.-D.; Dong, B.; Jia, Y. A Multilevel Investigation of the Cascading Effect of Entrepreneurial Leadership on Employee Creativity: Evidence from Chinese Hospitality and Tourism Firms. Tour. Manag. 2024, 100, 104816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Fu, C. The Influence of Leader Empowerment Behaviour on Employee Creativity. Manag. Decis. 2020, 58, 2681–2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, L.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, X. How Does High-Commitment Work Systems Stimulate Employees’ Creative Behavior? A Multilevel Moderated Mediation Model. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 904174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalley, C.E.; Gilson, L.L. What Leaders Need to Know: A Review of Social and Contextual Factors That Can Foster or Hinder Creativity. Leadersh. Q. 2004, 15, 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhl-Bien, M.; Marion, R.; McKelvey, B. Complexity Leadership Theory: Shifting Leadership from the Industrial Age to the Knowledge Era. Leadersh. Q. 2007, 18, 298–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, M.S.; Jian, Z.; Akram, U.; Tariq, A. Entrepreneurial Leadership: The Key to Develop Creativity in Organizations. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2021, 42, 434–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awang, A.H.; Haron, M.; Zainuddin Rela, I.; Saad, S. Formation of Civil Servants’ Creativity through Transformative Leadership. J. Manag. Dev. 2020, 39, 499–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, F.-C. Does Transformational, Ambidextrous, Transactional Leadership Promote Employee Creativity? Mediating Effects of Empowerment and Promotion Focus. Int. J. Manpow. 2016, 37, 1250–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renko, M.; El Tarabishy, A.; Carsrud, A.L.; Brännback, M. Understanding and Measuring Entrepreneurial Leadership Style. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2015, 53, 54–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T.M.; Pratt, M.G. The Dynamic Componential Model of Creativity and Innovation in Organizations: Making Progress, Making Meaning. Res. Organ. Behav. 2016, 36, 157–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirst, G.; Van Knippenberg, D.; Zhou, J. A Cross-Level Perspective on Employee Creativity: Goal Orientation, Team Learning Behavior, and Individual Creativity. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 280–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; George, J.M. Awakening Employee Creativity: The Role of Leader Emotional Intelligence. Leadersh. Q. 2003, 14, 545–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Issa, H.-E.; Omar, M.M.S. Digital Innovation Drivers in Retail Banking: The Role of Leadership, Culture, and Technostress Inhibitors. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2024, 32, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, N.; Potočnik, K.; Zhou, J. Innovation and Creativity in Organizations: A State-of-the-Science Review, Prospective Commentary, and Guiding Framework. J. Manag. 2014, 40, 1297–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabić, M.; Lažnjak, J.; Smallbone, D.; Švarc, J. Intellectual Capital, Organisational Climate, Innovation Culture, and SME Performance: Evidence from Croatia. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2018, 26, 522–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Learning Theory; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1977; ISBN 978-0-13-816744-8. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986; ISBN 978-0-13-815614-5. [Google Scholar]

- Pauceanu, A.M.; Rabie, N.; Moustafa, A.; Jiroveanu, D.C. Entrepreneurial Leadership and Sustainable Development—A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.; Neesham, C.; Manville, G.; Tse, H.H.M. Examining the Influence of Servant and Entrepreneurial Leadership on the Work Outcomes of Employees in Social Enterprises. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 29, 2905–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, G.; Samreen, F.; Riaz, A.; Wan Ismail, W.K.; Sultan, M. A Cross-Level Relationship between Entrepreneurial Leadership and Followers’ Entrepreneurial Intentions through Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and Identification with the Leader under Moderating Role of Cultural Values. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 7478–7496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liden, R.C.; Wayne, S.J.; Liao, C.; Meuser, J.D. Servant Leadership and Serving Culture: Influence on Individual and Unit Performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 1434–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Morales, V.J.; Lloréns-Montes, F.J.; Verdú-Jover, A.J. The Effects of Transformational Leadership on Organizational Performance through Knowledge and Innovation*. Br. J. Manag. 2008, 19, 299–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raziq, M.M.; Saleem, S.; Borini, F.M.; Naz, F. Leader Spirituality and Organizational Innovativeness as Determinants of Transformational Leadership and Project Success: Behavioral and Social Learning Perspectives. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2024, 74, 56–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, A.; Cornett, M.M. Financial Institutions Management: A Risk Management Approach, 7th ed.; McGraw-Hill/Irwin: New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-0-07-353075-8. [Google Scholar]

- Brownson, C. Entrepreneurial Leadership and Managerial Sustainability. Int. J. Bus. Manag. Rev. 2022, 10, 42–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awashreh, R.; Hamid, A.A. The Role of Entrepreneurial Leadership in Driving Employee Innovation: The Mediating Effect of Knowledge Sharing. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2025, 12, 2466812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, J.A. The Theory of Economic Development: An Inquiry into Profits, Capital, Credit, Interest, and the Business Cycle; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1934; ISBN 978-0-674-87990-4. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, P.D. Entrepreneurship and Management. J. Small Bus. Manag. 1987, 25, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Covin, J.G.; Wales, W.J. Crafting High-Impact Entrepreneurial Orientation Research: Some Suggested Guidelines. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2019, 43, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, C.; Burnard, K.; Paul, S. Entrepreneurial Leadership in a Developing Economy: A Skill-Based Analysis. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2017, 25, 521–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.; MacMillan, I.C.; Surie, G. Entrepreneurial Leadership: Developing and Measuring a Cross-Cultural Construct. J. Bus. Ventur. 2004, 19, 241–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, G.; Luu, T.T.; Babalola, M.T. Entrepreneurial Leadership: A Systematic Literature Review and Research Agenda. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2024, 46, 285–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempster, S.; Cope, J. Learning to Lead in the Entrepreneurial Context. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2010, 16, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Zahra, I.; Rehman, S.U.; Jamil, S. How Knowledge Sharing Encourages Innovative Work Behavior through Occupational Self-Efficacy? The Moderating Role of Entrepreneurial Leadership. Glob. Knowl. Mem. Commun. 2022, 73, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guberina, T.; Wang, A.M.; Obrenovic, B. An Empirical Study of Entrepreneurial Leadership and Fear of COVID-19 Impact on Psychological Wellbeing: A Mediating Effect of Job Insecurity. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0284766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masa’deh, R.; Al-Henzab, J.; Tarhini, A.; Obeidat, B.Y. The Associations among Market Orientation, Technology Orientation, Entrepreneurial Orientation and Organizational Performance. Benchmarking Int. J. 2018, 25, 3117–3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirvonen, S.; Laukkanen, T.; Salo, J. Does Brand Orientation Help B2B SMEs in Gaining Business Growth? J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2016, 31, 472–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikker, J.; Bos, J.W.B. Bank Performance: A Theoretical and Empirical Framework for the Analysis of Profitability, Competition and Efficiency; Routledge: Abingdon, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-0-415-56961-3. [Google Scholar]

- Aljuhmani, H.Y.; Emeagwali, O.L.; Ababneh, B. The Relationships between CEOs’ Psychological Attributes, Top Management Team Behavioral Integration and Firm Performance. Int. J. Organ. Theory Behav. 2021, 24, 126–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljuhmani, H.Y.; Awwad, R.I.; Albuhisi, B.; Hamdan, S. The Impact of Digital Transformation Leadership Competencies on Firm Performance Through the Lens of Organizational Creativity and Digital Strategy. In Innovative and Intelligent Digital Technologies; Towards an Increased Efficiency: Volume 1; Al Mubarak, M., Hamdan, A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 283–293. ISBN 978-3-031-70399-7. [Google Scholar]

- AlAjlouni, A.O.; Aljuhmani, H.Y. Leveraging Business Intelligence for Enhanced Financial Performance: The Mediating Effect of Supply Chain Integration. In Achieving Sustainable Business Through AI, Technology Education and Computer Science: Volume 3: Business Sustainability and Artificial Intelligence Applications; Hamdan, A., Ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 79–89. ISBN 978-3-031-73632-2. [Google Scholar]

- Aljuhmani, H.Y.; Neiroukh, S. From AI Capability to Enhanced Organizational Performance: The Path Through Organizational Creativity. In Achieving Sustainable Business Through AI, Technology Education and Computer Science: Volume 2: Teaching Technology and Business Sustainability; Hamdan, A., Ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 667–676. ISBN 978-3-031-71213-5. [Google Scholar]

- Ayoub, H.S.; Aljuhmani, H.Y. Artificial Intelligence Capabilities as a Catalyst for Enhanced Organizational Performance: The Importance of Cultivating a Data-Driven Culture. In Achieving Sustainable Business Through AI, Technology Education and Computer Science: Volume 2: Teaching Technology and Business Sustainability; Hamdan, A., Ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 345–356. ISBN 978-3-031-71213-5. [Google Scholar]

- Enbaia, E.; Alzubi, A.; Iyiola, K.; Aljuhmani, H.Y. The Interplay Between Environmental Ethics and Sustainable Performance: Does Organizational Green Culture and Green Innovation Really Matter? Sustainability 2024, 16, 10230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkish, I.; Iyiola, K.; Alzubi, A.B.; Aljuhmani, H.Y. Does Digitization Lead to Sustainable Economic Behavior? Investigating the Roles of Employee Well-Being and Learning Orientation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nor-Aishah, H.; Ahmad, N.H.; Thurasamy, R. Entrepreneurial Leadership and Sustainable Performance of Manufacturing SMEs in Malaysia: The Contingent Role of Entrepreneurial Bricolage. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, A.; Musa, S. The Impact of Entrepreneurial Leadership on Innovation Management and Its Measurement Validation. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2017, 9, 2–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covin, J.G.; Slevin, D.P. Strategic Management of Small Firms in Hostile and Benign Environments. Strateg. Manag. J. 1989, 10, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, A.; Wenqi, J.; Akhtar, S. Entrepreneurial Leadership and Organizational Performance: Employee Creativity and Behavior. Manag. Decis. 2025, 63, 2486–2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T.M.; Pillemer, J. Perspectives on the Social Psychology of Creativity. J. Creat. Behav. 2012, 46, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alt, R.; Beck, R.; Smits, M.T. FinTech and the Transformation of the Financial Industry. Electron. Mark. 2018, 28, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Lysova, E.I.; Khapova, S.N.; Bossink, B.A.G. Does Entrepreneurial Leadership Foster Creativity Among Employees and Teams? The Mediating Role of Creative Efficacy Beliefs. J. Bus. Psychol. 2019, 34, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumford, M.D. Managing Creative People: Strategies and Tactics for Innovation. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2000, 10, 313–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, M.S.; Jian, Z.; Akram, U.; Akram, Z.; Tanveer, Y. Entrepreneurial Leadership and Team Creativity: The Roles of Team Psychological Safety and Knowledge Sharing. Pers. Rev. 2021, 51, 2404–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otache, I.; Mejabi, E.I.; Alogwuja, C.U.; Umar, K. Entrepreneurial Leadership and Hospitality Firm Performance: The Roles of Employee Creativity and Competitive Advantage. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2025, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasmeen, A.; Ajmal, S.K. How Ambidextrous Leadership Enhances Employee Creativity: A Quantitative Approach. Evid.-Based HRM A Glob. Forum Empir. Scholarsh. 2023, 12, 421–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinzimmer, L.G.; Michel, E.J.; Franczak, J.L. Creativity and Firm-Level Performance: The Mediating Effects of Action Orientation. J. Manag. Issues 2011, 23, 62–82. [Google Scholar]

- Khedhaouria, A.; Gurău, C.; Torrès, O. Creativity, Self-Efficacy, and Small-Firm Performance: The Mediating Role of Entrepreneurial Orientation. Small Bus. Econ. 2015, 44, 485–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Jian, C. Does Cloud Computing Improve Team Performance and Employees’ Creativity? Kybernetes 2021, 51, 582–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsafadi, Y.; Aljuhmani, H.Y. The Influence of Entrepreneurial Innovations in Building Competitive Advantage: The Mediating Role of Entrepreneurial Thinking. Kybernetes 2023, 53, 4051–4073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeYoung, R.; Lang, W.W.; Nolle, D.L. How the Internet Affects Output and Performance at Community Banks. J. Bank. Financ. 2007, 31, 1033–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwi Widyani, A.A.; Landra, N.; Sudja, N.; Ximenes, M.; Sarmawa, I.W.G. The Role of Ethical Behavior and Entrepreneurial Leadership to Improve Organizational Performance. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2020, 7, 1747827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, A.; Daryani, M.A.; Rahmani, S. The Influence of Entrepreneurial Orientation on Firm Growth among Iranian Agricultural SMEs: The Mediation Role of Entrepreneurial Leadership and Market Orientation. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2021, 11, 519–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frese, M.; Gielnik, M.M. The Psychology of Entrepreneurship: Action and Process. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2023, 10, 137–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T.M.; Conti, R.; Coon, H.; Lazenby, J.; Herron, M. Assessing the Work Environment for Creativity. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 1154–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, E.H.; Chakrabarti, A.K. Innovation Speed: A Conceptual Model of Context, Antecedents, and Outcomes. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1996, 21, 1143–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissi, J.; Dainty, A.; Liu, A. Examining Middle Managers’ Influence on Innovation in Construction Professional Services Firms: A Tale of Three Innovations. Constr. Innov. Inf. Process Manag. 2012, 12, 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waheed, A.; Miao, X.; Waheed, S.; Ahmad, N.; Majeed, A. How New HRM Practices, Organizational Innovation, and Innovative Climate Affect the Innovation Performance in the IT Industry: A Moderated-Mediation Analysis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryee, S.; Hsiung, H.-H.; Jo, H.; Chuang, C.-H.; Chiao, Y.-C. Servant Leadership and Customer Service Performance: Testing Social Learning and Social Exchange-Informed Motivational Pathways. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2023, 32, 506–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, K. Developing Organizational Creativity and Innovation: Toward a Model of Self-Leadership, Employee Creativity, Creativity Climate and Workplace Innovative Orientation. Manag. Res. Rev. 2015, 38, 1126–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al’Ararah, K.; Çağlar, D.; Aljuhmani, H.Y. Mitigating Job Burnout in Jordanian Public Healthcare: The Interplay between Ethical Leadership, Organizational Climate, and Role Overload. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-de Castro, G.; Delgado-Verde, M.; Navas-López, J.E.; Cruz-González, J. The Moderating Role of Innovation Culture in the Relationship between Knowledge Assets and Product Innovation. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2013, 80, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamayo-Torres, I.; Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez, L.J.; Llorens-Montes, F.J.; Martínez-López, F.J. Organizational Learning and Innovation as Sources of Strategic Fit. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 1445–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcioglu, Y.S.; Evranos, F. Sustainable Digital Banking in Turkey: Analysis of Mobile Banking Applications Using Customer-Generated Content. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, E.C.; Terblanche, F. Building Organisational Culture That Stimulates Creativity and Innovation. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2003, 6, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Iyiola, K.; Alzubi, A.; Aljuhmani, H.Y. Using Safety-Specific Transformational Leadership to Improve Safety Behavior Among Construction Workers: Exploring the Role of Knowledge Sharing and Psychological Safety. Buildings 2025, 15, 3340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, S.T.; Bedell-Avers, K.E.; Mumford, M.D. The Typical Leadership Study: Assumptions, Implications, and Potential Remedies. Leadersh. Q. 2007, 18, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landry, G.; Vandenberghe, C. Relational Commitments in Employee–Supervisor Dyads and Employee Job Performance. Leadersh. Q. 2012, 23, 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Translation and Content Analysis of Oral and Written Materials. In Handbook of Cross-Cultural Psychology: Methodology; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1980; pp. 389–444. [Google Scholar]

- Behr, D. Assessing the Use of Back Translation: The Shortcomings of Back Translation as a Quality Testing Method. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2017, 20, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, N.; Cakan, S.; Kayacan, M. Intellectual Capital and Financial Performance: A Study of the Turkish Banking Sector. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2017, 17, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyiola, K.; Rjoub, H. Using Conflict Management in Improving Owners and Contractors Relationship Quality in the Construction Industry: The Mediation Role of Trust. Sage Open 2020, 10, 2158244019898834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awwad, R.I.; Aljuhmani, H.Y.; Hamdan, S. Examining the Relationships Between Frontline Bank Employees’ Job Demands and Job Satisfaction: A Mediated Moderation Model. Sage Open 2022, 12, 21582440221079880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalay, M.O.; Altin, M.; Al Ani, M.K. From Diversity to Sustainability: How Board Meeting Frequency, Financial Performance and Foreign Members Enhance the Board Gender Diversity—ESG Performance Link. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2025, 25, 552–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkmen, S.Y.; Yigit, I. Diversification in Banking and Its Effect on Banks’ Performance: Evidence from Turkey. Am. Int. J. Contemp. Res. 2012, 2, 111–119. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, C.M.; Simmering, M.J.; Atinc, G.; Atinc, Y.; Babin, B.J. Common Methods Variance Detection in Business Research. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3192–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.-J.; van Witteloostuijn, A.; Eden, L. From the Editors: Common Method Variance in International Business Research. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2010, 41, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, P.; Farmer, S.M. Creative Self-Efficacy Development and Creative Performance over Time. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, A.; Prajogo, D.I.; Jayaram, J. Strengthening the Innovation Chain: The Role of Internal Innovation Climate and Strategic Relationships with Supply Chain Partners. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2013, 49, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, E.A.; Quaddus, M. Development and Validation of a Scale for Measuring Sustainability Factors of Informal Microenterprises—A Qualitative and Quantitative Approach. Entrep. Res. J. 2015, 5, 347–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business; New Society Publishers: Gabriola Island, BC, USA; Stony Creek, CT, USA, 1998; ISBN 978-0-86571-392-5. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, J.S.; Overton, T.S. Estimating Nonresponse Bias in Mail Surveys. J. Mark. Res. 1977, 14, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slil, E.; Iyiola, K.; Alzubi, A.; Aljuhmani, H.Y. Impact of Safety Leadership and Employee Morale on Safety Performance: The Moderating Role of Harmonious Safety Passion. Buildings 2025, 15, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamash, A.; Iyiola, K.; Aljuhmani, H.Y. The Role of Circular Economy Entrepreneurship, Cleaner Production, and Green Government Subsidy for Achieving Sustainability Goals in Business Performance. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindell, M.K.; Whitney, D.J. Accounting for Common Method Variance in Cross-Sectional Research Designs. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, J. Applied Structural Equation Modeling Using AMOS: Basic to Advanced Techniques, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-0-367-43526-4. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Partial, Conditional, and Moderated Moderated Mediation: Quantification, Inference, and Interpretation. Commun. Monogr. 2018, 85, 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Ye, B. Analyses of Mediating Effects: The Development of Methods and Models. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 22, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill Companies: Columbus, OH, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Aljuhmani, H.Y.; Ababneh, B.; Emeagwali, L.; Elrehail, H. Strategic Stances and Organizational Performance: Are Strategic Performance Measurement Systems the Missing Link? Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2022, 16, 282–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-8058-6373-4. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. Commentary: Issues and Opinion on Structural Equation Modeling. MIS Q. 1998, 22, vii–xvi. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the Evaluation of Structural Equation Models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, G.M.; Feinn, R. Using Effect Size—Or Why the P Value Is Not Enough. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2012, 4, 279–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and Resampling Strategies for Assessing and Comparing Indirect Effects in Multiple Mediator Models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alashiq, S.; Aljuhmani, H.Y. From Sustainable Tourism to Social Engagement: A Value-Belief-Norm Approach to the Roles of Environmental Knowledge, Eco-Destination Image, and Biospheric Value. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koryak, O.; Mole, K.F.; Lockett, A.; Hayton, J.C.; Ucbasaran, D.; Hodgkinson, G.P. Entrepreneurial Leadership, Capabilities and Firm Growth. Int. Small Bus. J. 2015, 33, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaque, A.; Lee, I.; Mangalaraj, G. The Effect of Entrepreneurial Leadership Traits on Corporate Sustainable Development and Firm Performance: A Resource-Based View. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2023, 36, 177–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surie, G.; Ashley, A. Integrating Pragmatism and Ethics in Entrepreneurial Leadership for Sustainable Value Creation. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 81, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-H. Entrepreneurial Leadership and New Ventures: Creativity in Entrepreneurial Teams. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2007, 16, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayat-ur-Rehman, I.; Hossain, M.N. The Impacts of Fintech Adoption, Green Finance and Competitiveness on Banks’ Sustainable Performance: Digital Transformation as Moderator. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyiola, K.; Alzubi, A.; Dappa, K. The Influence of Learning Orientation on Entrepreneurial Performance: The Role of Business Model Innovation and Risk-Taking Propensity. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2023, 9, 100133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koseoglu, G.; Liu, Y.; Shalley, C.E. Working with Creative Leaders: Exploring the Relationship between Supervisors’ and Subordinates’ Creativity. Leadersh. Q. 2017, 28, 798–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Barros, R.; Resende, L.M.; Pontes, J. Exploring Creativity and Innovation in Organizational Contexts: A Systematic Review and Bibliometric Analysis of Key Models and Emerging Opportunities. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2025, 11, 100526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshahrani, M.A.; Yaqub, M.Z.; Ali, M.; El Hakimi, I.; Salam, M.A. Could Entrepreneurial Leadership Promote Employees’ IWB? The Roles of Intrinsic Motivation, Creative Self-Efficacy and Firms’ Innovation Climate. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Süer, Ö.; Levent, H.; Şen, S. Foreign Entry and the Turkish Banking System in 2000s. North Am. J. Econ. Financ. 2016, 37, 420–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousrih, J. The Impact of Digitalization on the Banking Sector: Evidence from Fintech Countries. Asian Econ. Financ. Rev. 2023, 13, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekin, Z. Green Banking Strategies: Evidence from Turkish Banks. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2025, 25, 930–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, R.C.; Scullion, H. Inclusive Leadership in a Turbulent Global World: A Systematic Review and Future Research Directions. In Advances in Global Leadership; Osland, J.S., Reiche, B.S., Maznevski, M.L., Mendenhall, M.E., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2025; Volume 16, pp. 151–166. ISBN 978-1-83662-289-5. [Google Scholar]

- Rehman, K.; Lim, K.B.; Yeo, S.F.; Saif, N.; Ameeq, M. The Nexus of Entrepreneurial Leadership and Entrepreneurial Success with a Mediation of Technology Management Processes: From the Perspective of the Small- and Medium-Sized Enterprises of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Sustainability 2025, 17, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adu, I.N.; Boakye, K.O.; Yeboah, S.; Twumasi, E. Entrepreneurial Leadership and Employee Performance; the Role of Innovative Work Behavior among Employees in the Food and Beverages Industry. Int. Hosp. Rev. 2024, 39, 2516–8142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.; Al-refaei, A.A.; Alshuhumi, S.; Al-Hidabi, D.; Ateeq, A. The Effect of Entrepreneurial Leadership on Employee’s Creativity and Sustainable Innovation Performance in Education Sector: A Literature Review. In Business Development via AI and Digitalization: Volume 1; Hamdan, A., Harraf, A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 1005–1017. ISBN 978-3-031-62102-4. [Google Scholar]

- Ercantan, K.; Eyupoglu, Ş.Z.; Ercantan, Ö. The Entrepreneurial Leadership, Innovative Behaviour, and Competitive Advantage Relationship in Manufacturing Companies: A Key to Manufactural Development and Sustainable Business. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atobishi, T.; Podruzsik, S. Ethical Entrepreneurial Leadership and Corporate Sustainable Development: A Resource-Based View of Competitive Advantage in Small and Medium Enterprises. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mamun, A.; Ibrahim, M.D.; Yusoff, M.N.H.B.; Fazal, S.A. Entrepreneurial Leadership, Performance, and Sustainability of Micro-Enterprises in Malaysia. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcellos, S.L.D.; Parente, R.C.; Schotter, A.P.J.; Garrido, I.L.; Gonçalo, C.R. Organizational Creativity: A Microfoundation of the International Business Competence and Performance Link. J. Int. Manag. 2024, 30, 101203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zheng, J.; Darko, A. How Does Transformational Leadership Promote Innovation in Construction? The Mediating Role of Innovation Climate and the Multilevel Moderation Role of Project Requirements. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marfu, A.; Abbas, H.; Sya, A.; Purwanto, A.; Nadiroh; Sumargo, B.; Wulandari, S.S.; Malaihollo, C.A.; Tanubrata, D.; Pratiwi, D.I. Building Long-Term Value: A Practical Guide to Integrating ESG into Business Strategies. Sustain. Futures 2025, 10, 100955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, R.J.J.; Hanges, P.J.J.; Javidan, M. Culture, Leadership, and Organizations: The GLOBE Study of 62 Societies, 1st ed.; Dorfman, P.W.W., Gupta, V., Eds.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-0-7619-2401-2. [Google Scholar]

| Demographic Profiles | Categories | Frequency | Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 278 | 60.57 |

| Female | 181 | 39.43 | |

| Education | Bachelor degree | 307 | 66.89 |

| Master degree | 101 | 22.00 | |

| Others | 51 | 11.11 | |

| Experience | Less than 3 | 69 | 13.77 |

| Between 3 and 5 | 162 | 32.34 | |

| More than 6 years | 201 | 40.12 | |

| Total | 459 | 100% |

| Constructs | Indicators | SFL | CA | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurial Leadership | 0.886 | 0.890 | 0.553 | ||

| EL1 | 0.711 | ||||

| EL2 | 0.744 | ||||

| EL3 | 0.693 | ||||

| EL4 | 0.699 | ||||

| EL5 | 0.754 | ||||

| EL6 | 0.708 | ||||

| EL7 | 0.624 | ||||

| EL8 | 0.732 | ||||

| Employee Creativity | 0.835 | 0.821 | 0.537 | ||

| EC1 | 0.787 | ||||

| EC2 | 0.699 | ||||

| EC2 | 0.638 | ||||

| EC4 | 0.794 | ||||

| Innovation-Oriented Climate | 0.821 | 0.823 | 0.538 | ||

| IOC1 | 0.757 | ||||

| IOC2 | 0.722 | ||||

| IOC3 | 0.729 | ||||

| IOC4 | 0.727 | ||||

| Sustainable Bank Performance | 0.935 | 0.938 | 0.791 | ||

| EP | 0.938 | ||||

| SO | 0.905 | ||||

| EN | 0.914 | ||||

| Construct | Mean | Std | EL | EC | IOC | SBP | Edu | Ex |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EL | 5.133 | 0.530 | (0.503) | |||||

| EC | 5.573 | 0.501 | 0.497 ** | (0.732) | ||||

| IOC | 4.856 | 0.572 | 0.517 ** | 0.465 ** | (0.734) | |||

| SBP | 5.552 | 0.664 | 0.674 ** | 0.704 ** | 0.515 ** | (0.889) | ||

| Edu | - | - | 0.074 | 0.074 | 0.031 | 0.065 | na | |

| Ex | - | - | 0.037 | 0.036 | 0.006 | 0.039 | 0.040 | na |

| Fit Indicators | Cut-Off Range | Results |

|---|---|---|

| CMIN/df | ≤3 | 2.195 |

| TLI | ≥0.9 | 0.946 |

| NFI | ≥0.9 | 0.923 |

| RFI | ≥0.9 | 0.905 |

| RMSEA | ≤0.9 | 0.061 |

| CFI | ≤0.9 | 0.956 |

| GFI | ≥0.9 | 0.903 |

| Relationships | β | S.E. | t-Values | p-Values | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 2.910 | 0.179 | 16.286 | <0.001 | [2.559, 3.262] |

| H1: EL → SBP | 0.371 | 0.054 | 6.823 | <0.001 | [0.264, 0.487] |

| H2: EL → EC | 0.539 | 0.036 | 14.996 | <0.001 | [0.468, 0.610] |

| H3: EC → SBP | 0.664 | 0.065 | 10.269 | <0.001 | [0.573, 0.791] |

| H4: EL → EC → SBP | 0.357 | 0.043 | - | <0.001 | [0.277, 0.444] |

| Paths | β | S.E. | t-Values | p-Values | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Employee Creativity | |||||

| Intercept | 0.097 | 0.031 | 2.816 | <0.001 | [0.048, 0.128] |

| Gender | 0.039 | 0.060 | 0.188 | >0.05 | [−0.073, 0.210] |

| Education | 0.018 | 0.072 | 0.105 | >0.05 | [0.049, 0.103] |

| EL | 0.483 | 0.042 | 11.516 | <0.001 | [0.400, 0.566] |

| IOC | 0.190 | 0.041 | 4.539 | <0.001 | [0.108, 0.272] |

| H5: EL × IOC → EC | 0.108 | 0.048 | 2.262 | <0.05 | [0.014, 0.202] |

| R2 = 0.451 | |||||

| The conditional direct effect of EL on EC at different levels of IOC | |||||

| IOC (−1SD) | 0.423 | 0.043 | 9.613 | <0.001 | [0.436, 0.661] |

| IOC (Mean) | 0.486 | 0.042 | 9.774 | <0.001 | [0.337, 0.508] |

| IOC (+1SD) | 0.549 | 0.057 | 11.197 | <0.001 | [0.402, 0.569] |

| Model 2: Sustainable Bank performance | |||||

| Constant | 5.558 | 0.026 | 214.587 | <0.001 | [5.507, 5.609] |

| Gender | 0.028 | 0.077 | 0.119 | >0.05 | [−0.061, 0.99] |

| Education | 0.010 | 0.104 | 0.036 | >0.05 | [−0.027, 0.084] |

| EL | 0.310 | 0.059 | 5.298 | <0.001 | [0.195, 0.320] |

| EC | 0.596 | 0.065 | 9.218 | <0.001 | [0.468, 0.723] |

| IOC | 0.212 | 0.050 | 4.207 | <0.000 | [0.113, 0.311] |

| H6: EL × IOC → SBP | 0.107 | 0.093 | 1.160 | >0.05 | [−0.075, 0.290] |

| Interaction: EC × IOC → SBP | 0.179 | 0.071 | 2.559 | <0.05 | [0.062, 0.302] |

| H7: The conditional indirect effect of EL on SBP through EC at different levels of IOC | |||||

| IOC (−1SD) | 0.270 | 0.057 | [0.160, 0.380] | ||

| IOC (Mean) | 0.289 | 0.039 | [0.214, 0.368] | ||

| IOC (+1SD) | 0.295 | 0.052 | [0.194, 0.402] | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ageli, R.; Alzubi, A.B.; Aljuhmani, H.Y.; Iyiola, K. How and When Entrepreneurial Leadership Drives Sustainable Bank Performance: Unpacking the Roles of Employee Creativity and Innovation-Oriented Climate. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9259. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209259

Ageli R, Alzubi AB, Aljuhmani HY, Iyiola K. How and When Entrepreneurial Leadership Drives Sustainable Bank Performance: Unpacking the Roles of Employee Creativity and Innovation-Oriented Climate. Sustainability. 2025; 17(20):9259. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209259

Chicago/Turabian StyleAgeli, Rajia, Ahmad Bassam Alzubi, Hasan Yousef Aljuhmani, and Kolawole Iyiola. 2025. "How and When Entrepreneurial Leadership Drives Sustainable Bank Performance: Unpacking the Roles of Employee Creativity and Innovation-Oriented Climate" Sustainability 17, no. 20: 9259. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209259

APA StyleAgeli, R., Alzubi, A. B., Aljuhmani, H. Y., & Iyiola, K. (2025). How and When Entrepreneurial Leadership Drives Sustainable Bank Performance: Unpacking the Roles of Employee Creativity and Innovation-Oriented Climate. Sustainability, 17(20), 9259. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209259