Teaching Equity and Perceived Learning Effect in Dual-Teacher Classroom Under Education for Sustainable Development: A Comparative Study of Student Engagement Mechanisms Through the Opportunity-to-Learn Framework

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Education for Sustainable Development

1.2. Dual-Teacher Classroom: A New Model of Education for Sustainable Development to Address Urban-Rural Educational Gaps

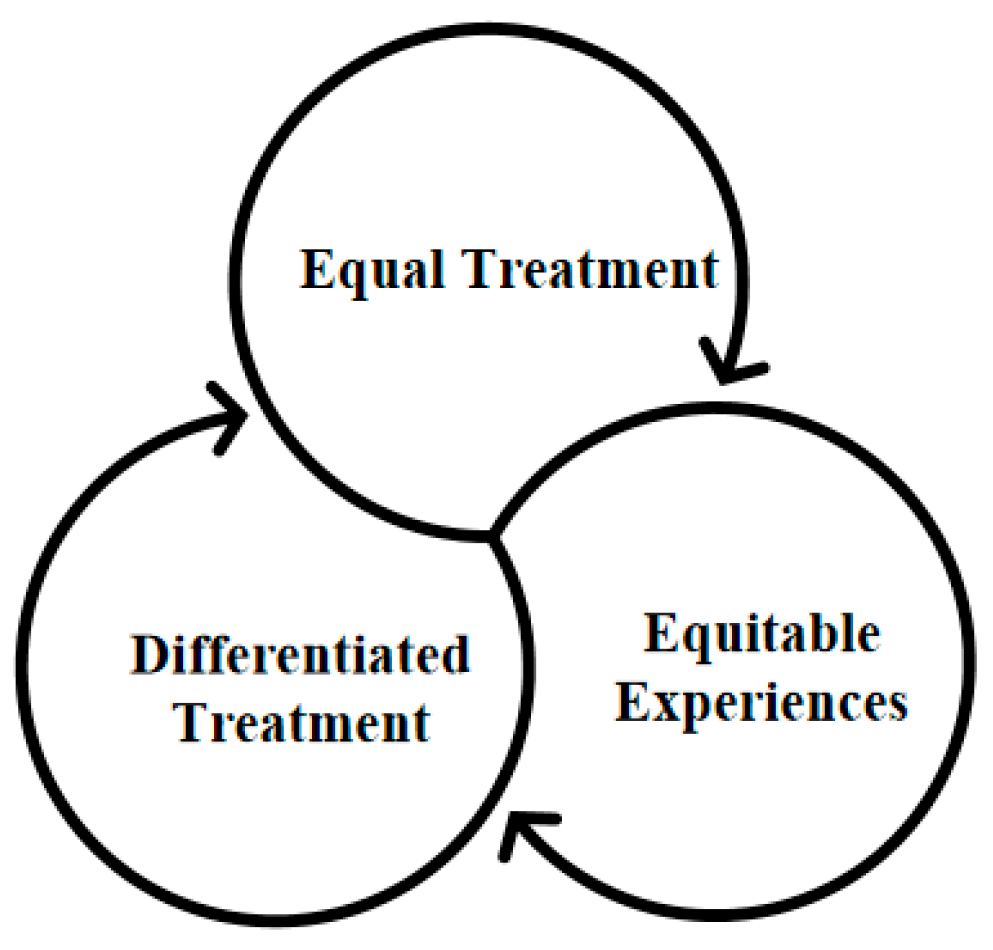

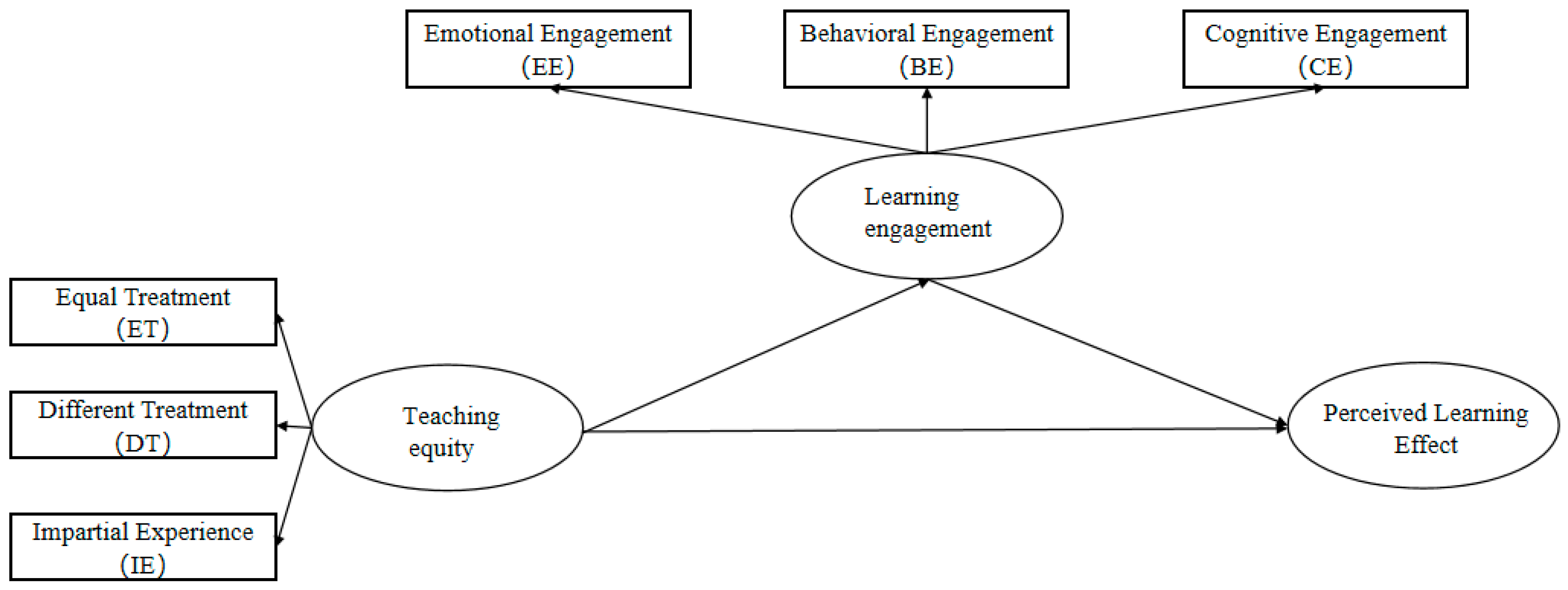

1.3. The Framework of Teaching Equity Under the OTL Theory: From Theory to Practice

- A.

- Equal Treatment: Ensuring uniform access to learning identities, rights, and resources (Lei, 2018) [25]. However, contemporary research cautions that such procedural uniformity, while foundational, can inadvertently sustain inequities if applied rigidly without considering students’ diverse starting points (Kwok et al., 2025) [26].

- B.

- Differentiated Treatment: Adapting instruction to address individual needs, particularly for disadvantaged students (Boaler & Sengupta-Irving, 2016) [3]. Effective differentiation is increasingly framed as a humanizing practice that responds to students’ unique cultural and cognitive assets, rather than a mere technical adjustment (Kwok et al., 2025; Phuong et al., 2025) [26,27].

- C.

- Equitable Experiences: Prioritizing students’ subjective perceptions of fairness, trust, and satisfaction (Yang & Li, 2016) [28]. This dimension aligns with the growing emphasis on transformative social-emotional learning and “expansive framing,” which prioritizes students’ sense of belonging, identity, and relevance in the learning process (Yadati et al., 2025; Freedman et al., 2025) [9,29].

1.4. Learning Engagement and Perceived Learning Effect: A Multidimensional Lens

- How do urban-rural disparities in Dual-Teacher Classroom for ESD influence students’ perceptions of teaching equity?

- Which dimensions of learning engagement mediate the relationship between teaching equity and perceived learning effect?

- How does teaching equity contribute to narrowing the gap in perceived learning effect between urban and rural student groups?

Hypotheses

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Context of the Study and Participants

2.2. Research Instrument

2.2.1. Dual-Teacher Classroom Teaching Equity Survey

2.2.2. Dual-Teacher Classroom Student Learning Engagement Survey

2.2.3. Dual-Teacher Classroom Student Perceived Learning Effect Survey

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Common Method Bias Test

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Analysis

Descriptive Statistics, Differences, and Correlations

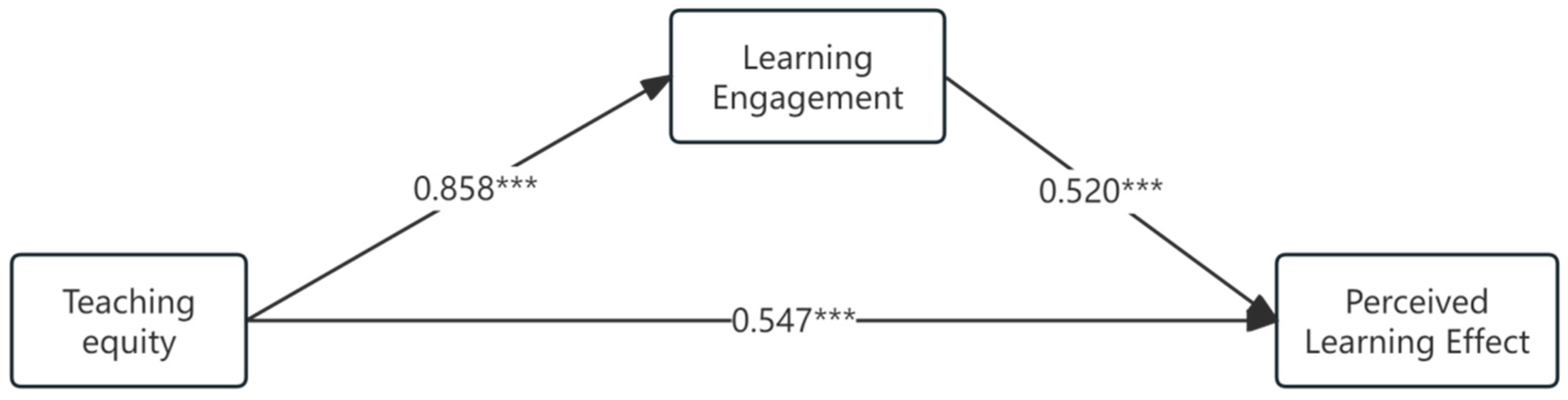

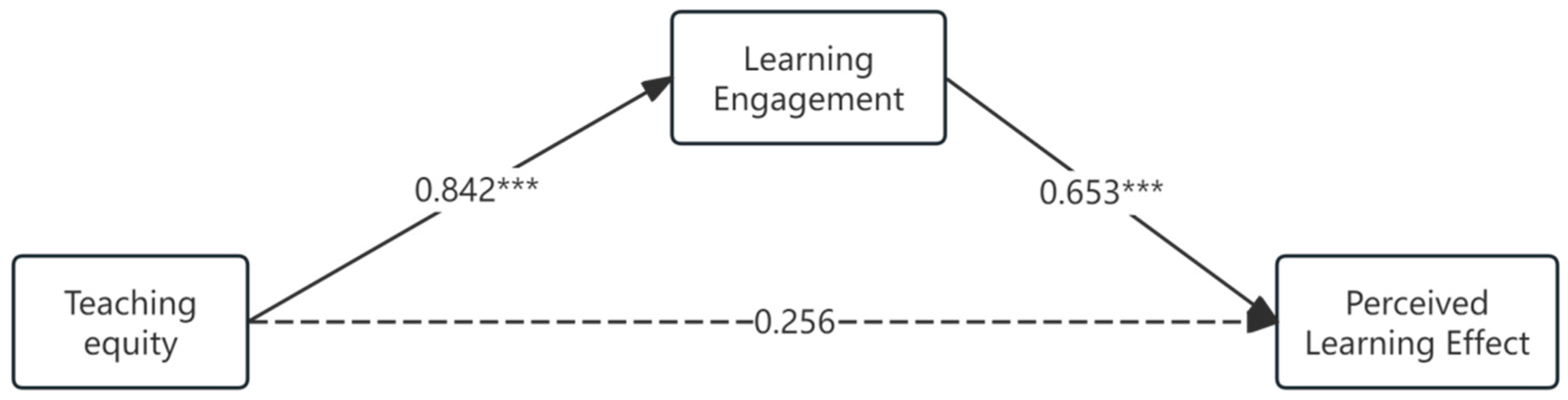

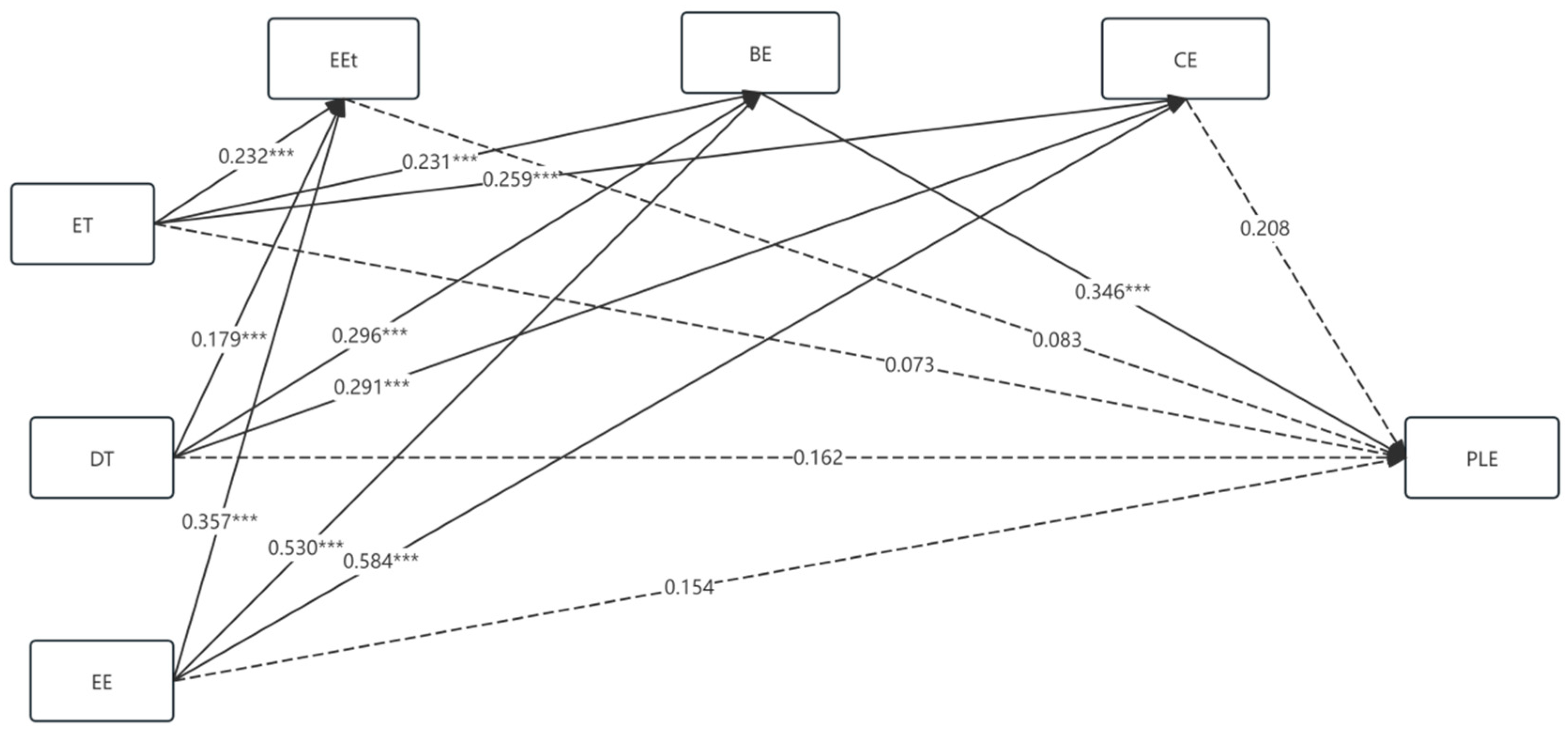

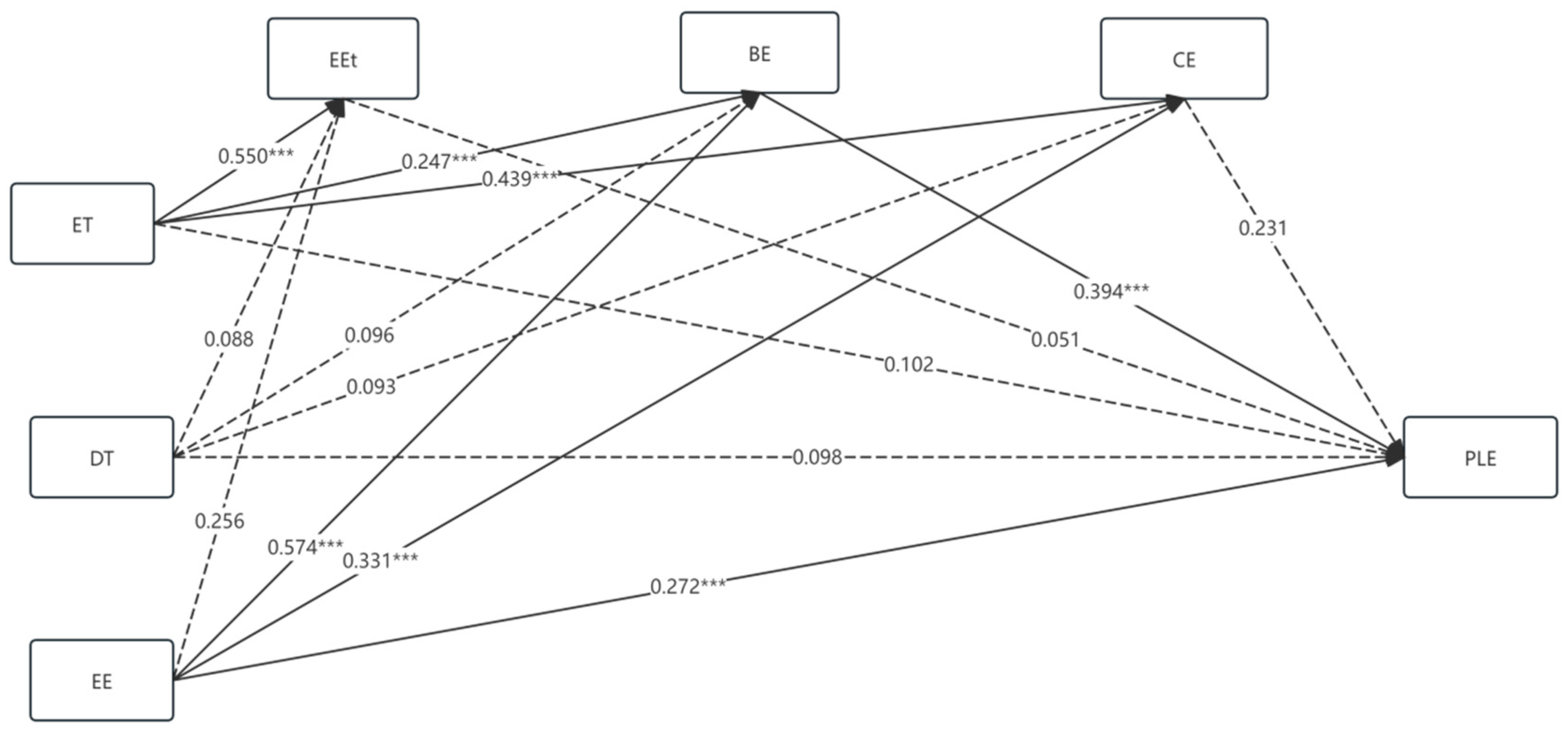

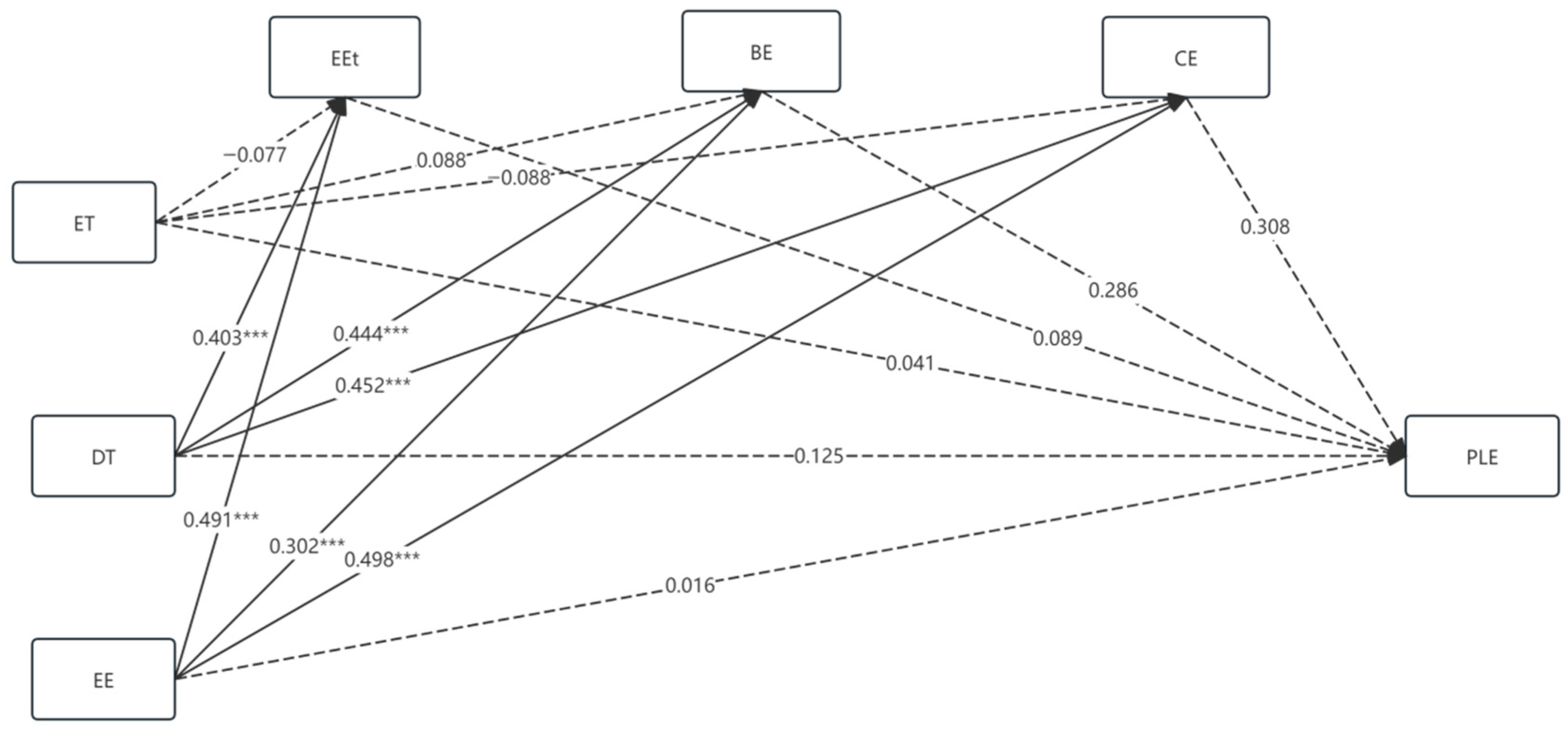

3.3. Mediating Effects and Heterogeneity in Dual-Teacher Classroom

3.4. Dual-Teacher Classroom Structural Equation Model and Heterogeneity

4. Discussion

4.1. Significant Differences in Teaching Equity, Learning Engagement, and Perceived Learning Effect Between Rural and Urban Students in Dual-Teacher Classroom

4.2. Teaching Equity in the Dual-Teacher Classroom Has a Significant Positive Effect on Perceived Learning Effect, with Equitable Experiences as the Strongest Sub-Dimension

4.3. Teaching Equity in the Dual-Teacher Classroom Significantly Influences Perceived Learning Effect Through the Mediation of Learning Engagement, with Variation in Effects Between Rural and Urban Groups

4.4. Structural Equation Model Pathways Differ Between Rural and Urban Students in the Dual-Teacher Classroom, with Equal Treatment in Teaching Equity and Learning Engagement Exhibiting Significant Positive Effects for Urban but Not Rural Students

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OTL | Opportunity to Learn |

| ESD | Education for Sustainable Development |

| ET | Equal Treatment |

| DT | Differentiated Treatment |

| EE | Equitable Experiences |

| EEt | Emotional Engagement |

| BE | Behavioral Engagement |

| CE | Cognitive Engagement |

| PLE | Perceived Learning Effect |

References

- Braßler, M. Students’ digital competence development in the production of open educational resources in education for sustainable development. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. About the Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Boaler, J.; Sengupta-Irving, T. The many colors of algebra: The impact of equity focused teaching upon student learning and engagement. J. Math. Behav. 2016, 41, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnam, K.J.; Johnson, S.L.; Waasdorp, T.E.; Bradshaw, C.P. Equity, connection, and engagement in the school context to promote positive youth development. J. Res. Adolesc. 2014, 24, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farley, I.A.; Burbules, N.C. Online education viewed through an equity lens: Promoting engagement and success for all learners. Rev. Educ. 2022, 10, e3367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Chen, X. Study on the influence of teaching equity on students’ interest in learning. Chin. Univ. Teach. 2012, 7, 81–84. [Google Scholar]

- Rolleston, C.; James, Z.; Aurino, E. Exploring the Effect of Educational Opportunity and Inequality on Learning Outcomes in Ethiopia, Peru, India, and Vietnam; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2013; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000225938 (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Goldin, S.; Robinson, D.D.; Shaughnessy, M.; Garcia, N.M.; Blunk, M.; Pynes, D.A.; Mortimer, J.P. Beyond Technical Fixes: Reconsidering Equity Sticks and Expanding Notions of Equitable Teaching. Urban Educ. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, E.B.; Hickey, D.T.; Schamberger, B.; Harris, T. Reimaging productive disciplinary engagement and expansive framing: A synthesis of equity-oriented scholarship. Educ. Psychol. 2025, 60, 106–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Rao, J.; Jia, Y. “Three classrooms” promote the high-quality and balanced development of compulsory education: Evolution history, strategic value, relationship analysis and conceptual framework. Mod. Educ. Technol. 2021, 31, 14–22. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, W.; Li, W.J. Evolutionary Logic and Future Trends of Education for Sustainable Development: An Analysis Based on UNESCO Series Reports. J. Comp. Educ. 2023, 45, 3–11+33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messiou, K. Research in the field of inclusive education: Time for a rethink? Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2016, 21, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; He, H. Effective teaching behavior in online teaching in university courses—Based on an empirical analysis of large-scale online teaching during the epidemic. Mod. Educ. Manag. 2022, 3, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, L.; Liu, X.; Lin, C. The collaborative dilemma of double-teacher classroom: Causes, phenomenon and cracking—Based on the perspective of organizational boundary. Audio-Vis. Educ. China 2024, 6, 87–93. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Yuan, Y.; He, Z. How can we enhance elementary students’ learning engagement in a Dual-Teacher Classroom setting? an analysis of a moderated mediation effect. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2025, 33, 4681–4697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coiduras, J.L.; Blanch, A.; Barbero, I. Initial teacher education in a dual-system: Addressing the observation of teaching performance. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2020, 64, 100834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyman, B.; Jane, B.K. Mathematics and Science Education Around the World: What Can We Learn from the Survey of Mathematics and Science Opportunities (SMSO) and the Third International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS)? National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1996; pp. 70–72. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, J.B. A model of school learning. Teach. Coll. Rec. 1963, 64, 723–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, F.I. Applying an Opprtunity to Learn. In Handbook of Education Policy Research; Sestigation of the Effects of Teaching Practices via Secondary Analyses of Multiple-Case-Study Summary Data. J. Negro Educ. 1993, 62, 232–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, W.H.; Maier, A. Opportunity to Learn. In Handbook of Education Policy Research; Sykes, G., Schneider, B., Plank, D.N., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 541–559. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, M. Rogative Learning in Education for Sustainable Development: Environment, Human Rights and Democracy. J. Sustain. Dev. Stud. 2016, 9, 52–75. [Google Scholar]

- Urick, A.; Wilson, A.S.P.; Ford, T.G.; Frick, W.C.; Wronowski, M.L. Testing a Framework of Math Progress Indicators for ESSA: How Opportunity to Learn and Instructional Leadership Matter. Educ. Adm. Q. 2018, 54, 396–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurz, A.; Elliott, S.N.; Wehby, J.H.; Smithson, J.L. Assessing Opportunity-to-Learn for Students with Disabilities in General and Special Education Classes. Assess. Eff. Interv. 2014, 40, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margaret, P.W.; Holly, G. Instruction in Co-Teaching in the Age of Endrew F. Behav. Modif. 2019, 45, 39–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.Q. Research on Classroom Teaching Equity and Its Indicator System. Ph.D. Thesis, Nanjing Normal University, Nanjing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kwok, M.; Su-Keene, E.; Rios, A. Preservice teachers’ conceptualizations of equity and equality: Tensions between technical and humanizing approaches. J. Teach. Educ. 2025, 76, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuong, A.E.; Nguyen, J.; Huang, F.; Vo, J.; Mejia, F.D.; Hunn, C.T. Lenses for Characterizing Equitable College STEM Teaching: Aligning Equity and Academic Goals. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference of the Learning Sciences-ICLS 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 10–13 June 2025; International Society of the Learning Sciences: Bochum, Germany, 2025; pp. 889–897. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Li, X. Index studies focusing on equity within schools. Educ. Sci. Res. 2016, 11, 5–12+21. [Google Scholar]

- Yadati, N.; Thomas, B.; Rajan, S.K. Promoting equity through teacher practices: A scoping review on transformative social-emotional learning. Issues Educ. Res. 2025, 35, 422–441. [Google Scholar]

- Trainor, A.A.; Robertson, P.M. Culturally and linguistically diverse students with learning disabilities: Building a framework for addressing equity through empirical research. Learn. Disabil. Q. 2020, 45, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhao, X. Research on teaching improvement and countermeasures under the perspective of classroom fairness—Empirical analysis of OECD global teaching insight video research data in Shanghai, China. Res. Educ. Dev. 2021, 41, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denessen, E.; Keller, A.; van den Bergh, L.; van den Broek, P. Do Teachers Treat Their Students Differently? An Observational Study on Teacher–Student Interactions as a Function of Teacher Expectations and Student Achievement. Educ. Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 2471956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, G.W. Empirical indicators of educational equity and equality: A Thai case study. Soc. Indic. Res. 1983, 12, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Bergin, C.; Bergin, D.A. Measuring engagement in fourth to twelfth grade classrooms: The Classroom Engagement Inventory. Sch. Psychol. Q. 2014, 29, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Yang, Z.; Jin, C.; Qi, Y.; Liu, X. The influence of emotion on fairness-related decision making: A critical review of theories and evidence. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltiainen, J.; Lipponen, J.; Petrou, P. Dynamics of trust and fairness during organizational change: Implications for job crafting and work engagement. In Organizational Change; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 90–101. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, C.B. Exploring Associations Among African American Youths’ Perceptions of Racial Fairness and School Engagement: Does Gender Matter? J. Appl. Sch. Psychol. 2018, 34, 338–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, T.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, X. From educational opportunities to learning opportunities: The microscopic vision of educational equity. Educ. Res. Tsinghua Univ. 2018, 39, 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Arbaugh, J.B. Does academic discipline moderate CoI-course outcomes relationships in online MBA courses? Internet High. Educ. 2013, 17, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentzel, K.R.; Miele, D.B. Engagement and Disaffection as Organizational Constructs in the Dynamics of Motivational Development. In Handbook of Motivation at School, 2nd ed.; Wentzel, K.R., Miele, D.B., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 237–260. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, L.J.; Parsons, M.; Whitcombe, D. Assessment in Smart Learning Environments: Psychological factors affecting perceived learning. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 95, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacker, R.E.; Lomax, R.G. A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; Taylor and Francis Group, LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Rucker, D.D.; Hayes, A.F. Addressing Moderated Mediation Hypotheses: Theory, Methods, and Prescriptions. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2007, 42, 185–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H. The Decision Science Dictionary; People’s Publishing House: Beijing, China, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Truijen, K.J.; Sleegers, P.J.; Meelissen, M.R.; Nieuwenhuis, A.F.M. What makes teacher teams in a vocational education context effective? A qualitative study of managers’ view on team working. J. Workplace Learn. 2013, 25, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacharach, N.; Heck, T.W.; Dahlberg, K. Changing the face of student teaching through coteaching. Action Teach. Educ. 2010, 32, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mislevy, R.J.; Haertel, G.; Cheng, B.H.; Ructtinger, L.; DeBarger, A.; Murray, E.; Vendlinski, T. A “conditional” sense of fairness in assessment. In Fairness Issues in Educational Assessment; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, R. Study on the current situation and influencing factors of fairness among primary and middle school students. Shanghai Educ. Res. 2023, 2, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King-Sears, M.E.; Strogilos, V. An exploratory study of self-efficacy, school belongingness, and co-teaching perspectives from middle school students and teachers in a mathematics co-taught classroom. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2020, 24, 162–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temkin, L. Equality as comparative fairness. J. Appl. Philos. 2017, 34, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J. The reflection and criticism of the limited effect theory. Young Rep. 2016, 29, 5–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension | N | Cronbach’s Alpha | Cronbach’s Alpha | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teaching Equity | Equal Treatment | 12 | 0.964 | 0.983 | |||

| Differentiated Treatment | 7 | 0.954 | |||||

| Equitable Experiences | 8 | 0961 | |||||

| Learning Engagement | Emotional Engagement | 5 | 0.950 | 0.973 | |||

| Behavioral Engagement | 5 | 0.951 | |||||

| Cognitive Engagement | 8 | 0.956 | |||||

| Perceived Learning Effect | - | 5 | - | 0.950 | |||

| (a) | |||||||

| X2/df | RMSEA | NFI | RFI | CFI | IFI | TLI | |

| Standard | <3 | <0.08 | >0.9 | >0.9 | >0.9 | >0.9 | >0.9 |

| Value | 1.933 | 0.058 | 0.979 | 0.971 | 0.989 | 0.990 | 0.986 |

| (b) | |||||||

| Construct | Composite Reliability (CR) | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) | HTMT Range with Other Constructs | ||||

| Equal Treatment | 0.965 | 0.712 | 0.78–0.85 | ||||

| Differentiated Treatment | 0.955 | 0.698 | 0.80–0.87 | ||||

| Equitable Experiences | 0.962 | 0.705 | 0.82–0.88 | ||||

| Emotional Engagement | 0.951 | 0.734 | 0.65–0.75 | ||||

| Behavioral Engagement | 0.952 | 0.741 | 0.76–0.84 | ||||

| Cognitive Engagement | 0.957 | 0.718 | 0.78–0.85 | ||||

| Perceived Learning Effect | 0.951 | 0.761 | 0.70–0.82 | ||||

| Variable | Group | N | Mean | SD | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teaching Equity | urban | 176 | 4.771 | 0.427 | 0.003 |

| rural | 102 | 4.590 | 0.506 | ||

| Learning Engagement | urban | 176 | 4.725 | 0.469 | 0.002 |

| rural | 102 | 4.536 | 0.523 | ||

| Perceived Learning Effect | urban | 176 | 4.722 | 0.525 | 0.013 |

| rural | 102 | 4.551 | 0.591 |

| Sub-Variable | Group | N | Mean | SD | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equal Treatment | urban | 176 | 4.777 | 0.430 | 0.005 |

| rural | 102 | 4.612 | 0.518 | ||

| Differentiated Treatment | urban | 176 | 4.748 | 0.487 | 0.003 |

| rural | 102 | 4.559 | 0.550 | ||

| Equitable Experiences | urban | 176 | 4.790 | 0.420 | 0.001 |

| rural | 102 | 4.598 | 0.518 | ||

| Emotional Engagement | urban | 176 | 4.673 | 0.637 | 0.065 |

| rural | 102 | 4.531 | 0.573 | ||

| Behavioral Engagement | urban | 176 | 4.759 | 0.475 | 0.001 |

| rural | 102 | 4.537 | 0.546 | ||

| Cognitive Engagement | urban | 176 | 4.742 | 0.434 | 0.001 |

| rural | 102 | 4.539 | 0.531 |

| 1 | 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Teaching Equity | 1.000 | ||

| Learning Engagement | 0.808 ** | 1.000 | |

| Perceived Learning Effect | 0.762 ** | 0.793 ** | 1.000 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ET | 1.000 | ||||||

| DT | 0.857 ** | 1.000 | |||||

| EE | 0.888 ** | 0.893 ** | 1.000 | ||||

| EEt | 0.608 ** | 0.603 ** | 0.626 ** | 1.000 | |||

| BE | 0.752 ** | 0.761 ** | 0.787 ** | 0.763 ** | 1.000 | ||

| CE | 0.787 ** | 0.793 ** | 0.823 ** | 0.725 ** | 0.888 ** | 1.000 | |

| PLE | 0.715 ** | 0.733 ** | 0.745 ** | 0.652 ** | 0.790 ** | 0.782 ** | 1.000 |

| Estimate | se | LLCI | ULCI | % of Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Effect | 0.993 | 0.055 | 0.885 | 1.101 | - |

| Direct Effect | 0.547 | 0.077 | 0.396 | 0.699 | 55.086% |

| Indirect Effect | 0.446 | 0.145 | 0.179 | 0.744 | 44.914% |

| Estimate | se | LLCI | ULCI | % of Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Effect | 0.806 | 0.087 | 0.634 | 0.978 | - |

| Direct Effect | 0.256 | 0.135 | −0.012 | 0.523 | 31.762% |

| Indirect Effect | 0.550 | 0.239 | 0.137 | 1.054 | 68.238% |

| Path | Rural Group | Urban Group |

|---|---|---|

| ET → EEt | −0.077 | 0.550 *** |

| ET → BE | 0.088 | 0.247 *** |

| ET → CE | −0.088 | 0.439 *** |

| DT → EEt | 0.403 *** | 0.088 |

| DT → BE | 0.444 *** | 0.096 |

| DT → CE | 0.452 *** | 0.093 |

| EE → EEt | 0.491 *** | 0.256 |

| EE → BE | 0.302 *** | 0.574 *** |

| EE → CE | 0.498 *** | 0.331 *** |

| EEt → PLE | 0.089 | 0.051 |

| BE → PLE | 0.286 | 0.394 *** |

| CE → PLE | 0.308 | 0.231 |

| ET → PLE | 0.041 | 0.102 |

| DT → PLE | 0.125 | 0.098 |

| EE → PLE | 0.016 | 0.272 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hu, G.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, D.; Liu, Z. Teaching Equity and Perceived Learning Effect in Dual-Teacher Classroom Under Education for Sustainable Development: A Comparative Study of Student Engagement Mechanisms Through the Opportunity-to-Learn Framework. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9216. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209216

Hu G, Zhu Y, Liu D, Liu Z. Teaching Equity and Perceived Learning Effect in Dual-Teacher Classroom Under Education for Sustainable Development: A Comparative Study of Student Engagement Mechanisms Through the Opportunity-to-Learn Framework. Sustainability. 2025; 17(20):9216. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209216

Chicago/Turabian StyleHu, Guangwei, Yonghai Zhu, Di Liu, and Ziling Liu. 2025. "Teaching Equity and Perceived Learning Effect in Dual-Teacher Classroom Under Education for Sustainable Development: A Comparative Study of Student Engagement Mechanisms Through the Opportunity-to-Learn Framework" Sustainability 17, no. 20: 9216. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209216

APA StyleHu, G., Zhu, Y., Liu, D., & Liu, Z. (2025). Teaching Equity and Perceived Learning Effect in Dual-Teacher Classroom Under Education for Sustainable Development: A Comparative Study of Student Engagement Mechanisms Through the Opportunity-to-Learn Framework. Sustainability, 17(20), 9216. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209216