Agency and Advocacy in Social Work: Promoting Social and Environmental Justice Through Professional Practice

Abstract

1. Environmental Crises and Social Implications: Epistemic Justice as an Overarching Framework

2. The Role of Social Work in Promoting Epistemic and Environmental Justice

3. Rationale and Aims

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Phase One: Narrative Interviews

4.2. Phase Two: Discussions in Small Groups

- Introductory session (December 2024, 1 h). It presented the research project and the structure and rationale of the training and research program. This meeting aimed to frame the overall program.

- Training session (January 2025, 2 h). It defined the overarching conceptual framework within which the next ones would develop. This meeting aimed to enhance participants’ knowledge and awareness regarding environmental justice and eco-social intervention frameworks, drawing on interdisciplinary, historical, and theoretical perspectives.

- Discussions in small groups [52] (February 2025, 2 h each). They were designed to foster collective reflection on the environmental challenges encountered in social work practice, identify critical issues and resources, and co-construct operational strategies for future action. The authors of this paper participated in the discussions in different roles, alternating as facilitators and observers. Three group discussions were organized after summarizing the key findings from the interviews, which were presented to participants to stimulate discussion and gather feedback. This synthesis also included the perspective favored by Asproc representatives, which was used as further insights to initiate (or foster) a richer and more nuanced reflection.

4.3. Data Analysis

5. Results

5.1. Awareness

There is discomfort, and there are certainly strong links with the economic conditions of households, so that those who are forced to live in extreme poverty or without enjoyment of their rights, and in my experience, they often find themselves living in completely inadequate housing, lacking even the minimum hygiene and sanitary requirements. That is why we are discussing people who may find themselves in overcrowded homes with inadequate sanitation [Interviews_ID3].

Catastrophic situations, overall, exacerbate the situations that people already experience in their everyday lives. There are two macro areas of concern: one involves people who, up to that point, have lived their lives independently and without major difficulties, as is the case for most of us. Their personal and family lives, in this context, are suddenly confronted with a disruptive event that is not the kind of disruptive event that occurs in personal situations, but rather a disruptive event that involves them personally and their immediate surroundings, as well as the broader context. In this regard, mobilizing resources is not easy, as they have never found themselves in situations of great difficulty, causing them to feel extremely lost [Interviews_ID6].

For example, one of the most serious problems at this stage is the problem of housing, lack of housing, unhealthy housing, cohabitation that should not exist, let’s say people living in the same environment, or living in, well, this is one of the major causes of unrest that we cannot say anything about... [Group3_ID1].

Then, for example, at the level of the relationship with the environment, as a service, there is still no culture of these things here, so even our professional action... which could be an action to change processes and open up to the environment, that is, we have it, but we have it as individuals, in a basic way... I don’t throw paper here, I throw it somewhere else... We are still at this level; we haven’t yet leaped into a local service. In implementing measures that may be environmental or sustainable, which are part of the environment, not only of the individual but of the environment as a territory, we don’t have a territory with too many polluting industries, however, the environment in another sense, i.e., the protection of the environment as a territory and the conservation of nature, is not a priority. On this point, yes, because we are in an area with parks, let’s say that the culture is present. Still, in terms of services, I regret that we do not have any good practices that could be leveraged to increase, for example, sustainability or projects involving renewable energy. These are all things that are not available here [Interviews_ID2].

If, as you have already done in part, you can help me identify examples of environmental justice, I will explain why. Because, if you ask me to discuss examples of social justice, inequality, or unequal access to resources that I have observed, I can do so easily, as it is my daily bread-i.e., what I work on. Environmental justice, as far as I can tell, based on my general knowledge or on issues that interest me, is not a professional issue that I deal with, or perhaps I deal with it indirectly, I don’t know if that could be an element of justice... it doesn’t have access to that kind of right to resources... [Interviews_ID12].

Of course, I agree, but in fact, I completely agree. When I read about this path, it really intrigued me because I had never heard the words’ justice’ and ‘environment’ used together... [Group1_ID2].

My specific situation is not that I have direct, immediate experience of these situations. Yes, some young people have suffered damage to their homes and have had to leave them. Still, it’s not my job because I deal with reports from drug users, so it’s not that I intervene or have any projects or interventions to propose in this regard, except for my sensitivity. Still, it doesn’t stem from the type of work I do, which remains unchanged. It can happen that you see people who live in those areas that are all affected, and they may say, “But I come from this area, we’ve lost a lot,” but that’s a competence that goes beyond my type of work [Interviews_ID11].

5.2. Knowledge

So, what can I say about this topic, which, if I am not mistaken, is ecological transition, right, environmental justice, and the role of social workers? I can discuss our code of ethics, which establishes a connection between social services and the environment, [...] It is present because it establishes the interrelationship between the environment, the individual, and society. The code of ethics was updated in 2020, at the start of the pandemic, so we made the update. It specifically refers to two articles: Article 5 and Article 13. We are facilitators of environmental processes, professionals dedicated to the integral development of individuals and communities. This is the role of the social worker, so we are accustomed to seeing them working primarily with individuals, but it spans a range from micro to macro, so I work with the community. [...]. Article 5 of the code of ethics states that social workers uphold the fundamental principles of the Constitution of the Italian Republic, recognize the intrinsic value, dignity, and uniqueness of all people, and their civil, political, economic, social, cultural, and environmental rights as provided for in international conventions. Article 13 states that social assistance contributes to the production of development models, so it is not enough to simply respect them. Still, we must also contribute to creating something operational, i.e., development models that respect the environment, promote economic sustainability, and ensure social survival, while being aware of the complexities in the relationship between human beings and the environment. Therefore, in our professional work, our goal is the well-being of people. We start from this in each context. Then there are different levels of interpretation: micro, middle, and macro, and so we start from the well-being of the person, thinking from the micro to the macro, starting from the awareness that intervention on the person has consequences on the context and everything around them, i.e., the environment and everything that surrounds us. Social well-being, therefore, presupposes a healthy environment in balance. In our professional activities, we act daily, making the best use of resources, which enables us to transition from the individual to the physical environment and thus recognize the importance of environmental sustainability. I can say this, and I am part of the ASPROC, which you called me because you probably drew from a list that we have in Article 42 of the code of ethics, which talks about the social worker who makes himself available to the authorities, and therefore the task and responsibility of the social worker to society [Interviews_ID9].

Now, something has just come to mind that is unrelated to this. Still, it is symbolically interesting in the context of life and the environment in the broad sense, as we understand them, rather than in social services. One of the activities that my colleague, or rather the two colleagues working in that context, was asked to do was all related to the cemetery. It would never have occurred to me to do something like that, sitting at a desk. Still, the shocks were so strong, we’re talking about an earthquake, but it could have been a flood, they were so strong that there was a complete disaster, a disaster at the level of the cemeteries, that is, uncovered graves, those in the niches, in short, I can’t describe it, but we can imagine it. So one of the activities that was there at the time, we said to ourselves, but what are we going to do in the cemeteries? It was essential because it’s a connection with their past, for them it was excruciating to think that even their graves were... Yes, I mean, it was essential because it’s excruciating to think that even their graves were... I mean, when this came out, I said I couldn’t believe it, but no, it’s not true... The history and memory of people are not the reason why, but it’s a bit like that in all countries, not just in Italy, and perhaps in different ways, but the cult of the dead is a historical phenomenon. You lose everything, and you also lose the most concrete memory, which is that of a cemetery, where you can find a moment, not just a few things. I’m the one who keeps talking about things for hours [Interviews_ID6].

I see injustice in terms of housing in the fact that it is increasingly difficult to find private rental accommodation because what is asked for does not correspond to the market, i.e., guarantees are asked for, pay slips are asked for, permanent contracts are asked for, but most people have on-call contracts, fixed-term contracts, and so there is this huge difficulty. So what happens? If you lose your job due to health or family issues, and the company no longer wants to retain you, you may be unable to pay your rent and risk losing your home, as evictions are very high [Interviews_ID13].

So, it is possible to say that where there is less nature, there is less health. In the sense that we know that in environments where there are few plants, where there is a strong urban connotation, and therefore gas, etc., health is... Yes, it’s true, it’s at risk, and inevitably, where there is less health, there is also less capacity for individuals to be well, not only individually but also within an activity, [...]. Therefore, where there is less nature, there is likely to be more disease or poorer health, and fewer resources are available to invest in other areas [Interviews_ID1].

However, there is this sense of place, etc., there is a strong connection with nature, but there is also the lake, the territory, the province of Bergamo has two large valleys, the Seriana Valley and the Brembana Valley... [...] [Interviews_ID5].

The other sore point is the environmental issue, which is talked about so much in courses and in many things, but then in reality, nothing much is done about it. Although I repeat, it always depends on how involved you are, in the sense that if you look around a bit, you might find something. For example, even regarding the implementation of all aspects related to Agenda 2030, we have had limited contact with social services in terms of involvement, despite these issues being closely related to topics of social justice and environmental justice. So, Agenda 2030 brings everything together, a series of principles that concern environmental justice on the one hand, which goes hand in hand with social justice, because it is one of the founding principles that states that if there is no social justice, there can be no environmental justice either. The issues are related, but I studied them at university, we have brought something to the table, as an order, as an interest, because on international social service days, the environment and inclusion, diversity in communities, remain very important issues [...] [Interviews_ID1].

If I may, I work in the municipality, and I often wonder why a social worker cannot be of support to the town planning office, for example? Why? Because often when living spaces are created and designed, only the physical space is considered. Still, no thought is given to the fact that a community will live in this physical space, and who better than we, as social institutions, can contribute our own perspective on the community, where we may have been working for a long time [Group2_ID2].

It was the first time I had ever considered this issue, the very first time, so, from my perspective, there is a significant lack of cultural awareness regarding environmental justice. More than environmental culture, it is a culture of environmental justice. It was interesting, to say the least, the approach, because then I started to think that it would take much more. For me, it remains the case that when I think of environmental justice, I think of natural disasters, rather than everyday life in our local communities and at work [Group2_ID1].

Yes, now I have to say that I find it a bit difficult to think of anything strictly directly related to environmental issues, except to imagine a context that changes a little depending on the geographical area, so, I don’t know, someone who lives in the high mountains, for example, but I don’t know, I don’t think it’s... I wouldn’t want it to be a little off topic... [Interviews_ID3].

In my experience, it’s an issue that... ...hasn’t yet come to the fore. I know what we’re talking about because... because of my interests, I have also researched and studied environmental issues, [...]. Still, I can tell you that during the meetings and gatherings we have, I have never even heard this word mentioned. It’s incredible that the connection is not yet being made. Even when we talk about the distribution of resources and access for all, no, it’s not an issue [...], well, it seems like a kind of taboo... a taboo subject... the problem is that we still talk about bad weather [...], and then linking this to environmental issues, social justice issues, etc., is a leap that is even bigger and, in my opinion, is not really being made [Interviews_ID7].

5.3. Practices

That’s why we say that the Children’s Town Council has been active for many years. The mayor is very keen on this, so he gives speeches too, and let’s say that the children’s mayor has the aim of making them understand that the municipality is their municipality, that if we take care of public affairs, what belongs to others is also ours. [...] maybe the child who is a little more lost in his own world finds less complicity in the context around him, that is, if you manage to reinforce those children who don’t really know which way to go at the beginning, a sense of civic duty with a sense of belonging [...] in short, you give clear communication, you clarify the rules that exist, you make it clear what the right and wrong behaviors are... [Interviews_ID5].

The issue I have also been involved in professionally, for example, the redevelopment of environments... where more peripheral, together I worked a lot in contact with social services and therefore with social workers, and here, that is, social housing is called Ater... and in collaboration to redevelop, create and therefore also give dignity to a place to live that is as adequate and peaceful as possible, it comes to mind, here [Group2_ID3].

In 2017, we launched what I believe to be the first 24-h social emergency service in Italy, operating five days a year. One of the first interventions carried out by the social emergency service was to intervene alongside the fire brigade, the police, etc., which is clearly the health component. There was a terrible fire in one of these small factories, part of which was empty and had been occupied by homeless people who were caught up in the fire. So, there are these situations that we observe which are part of, and the result of, social imbalance and are also influenced by environmental factors, in this case, the presence of very crowded living and working spaces [Interviews_ID14].

At Asproc, we are starting to create a database of the most vulnerable individuals in our respective areas. This includes the elderly who are not self-sufficient, the disabled, and those who require immediate assistance [Interviews_ID13].

Asproc [...] intervenes in the event of a disaster or emergency when the civil protection department is activated. Civil protection operates according to the principles of subsidiarity, so when there are sufficient forces in the area, national organizations are not activated. [...]. We were faced, for example, with a system that works quite well, with strong links to what are normally referred to as the technical offices of the municipalities, i.e., those responsible for divisions and so on, which are reinforced by engineers, architects, surveyors, and volunteers who systematically check the safety of houses. So, after checking the habitability, where we were able to do so, where we intervened, we tried to establish a direct link not only to communicate the results to people but also to evaluate alternative solutions because, paradoxically, very often we found ourselves faced with people who had habitable houses but did not want to return for any reason. Any one of us who had experience with family members or had acquaintances or relatives who had experienced such situations. We know very well that these people would rather stay in their cars for months than enter their homes because their fear is so great... On the other hand, there were people whose homes were uninhabitable but who did not want to move, even though they were entitled to alternative accommodation. They did not want to know about it because they did not want to move in, so we had to take all these aspects into account, as well as the environment... The working environment is also important. Experience has shown us that for these people, the possibility of keeping their jobs is more important than taking care of themselves, even in emergency situations such as the 2016 earthquake. However, in the initial interventions I carried out in Norcia, the most important thing for these people was to understand how to keep their businesses running, which were often linked to livestock farming, for example. In those cases, paradoxically, the civil protection agencies are united, but everyone is divided into sectors, and the part that deals with personal services is linked to veterinary services. I must say that there was no better combination, because putting pigs and people together is like saying that work and business are equally important. Otherwise, everyone would have been evacuated to the coast and housed in bungalows, rented houses, or hotels, but they returned to their homes every day, precisely because, apart from losing their jobs, it was what gave them hope of getting back on their feet a little. This is interesting because it highlights the difference between individuals who, despite their habitable homes, do not want to return, and others who, despite their uninhabitable homes, yearn to return due to a profound connection with nature [Interviews_ID6].

5.4. Strengths

So, yes, the work of mediation and networking and, in my opinion, a role of gathering the needs of sections of the population who may have less power and less ability to express their needs, including concerning the right to live in a healthy environment, and therefore acting as a conduit to bring the voice of these contexts to the fore [Group2_ID4].

Mediation, in this case, is essential, facilitated by social services. It can have a positive impact on community resilience and, therefore, also on active citizenship. This is a central question, given that the role of community promoter is one of the tasks that social workers are increasingly developing. They take what is available in the area and make it available to those who do not have access to it. It is increasingly a matter of gathering community work, [...], so you gather what the community has and, if necessary, develop it and make it available to those who cannot access it [Interviews_ID1].

In other situations, however, I have observed that, alongside vulnerability, there is a kind of cohesion or resilience among people. As a social worker, I find it easier to see the problems, [...], so elements of strong solidarity, not only among the people who are victims of these disasters, but also between these people and those who come to support them. From the perspective of the tools used, all the work of building small self-help groups has been very effective. This has helped a great deal. We are talking about people who were living in containers, and the fact that they were able to talk about their situation, exchange information, and feel very supported by each other and by the colleagues who organized this type of activity [Interviews_ID6].

This is a very valuable tool that all municipalities in Italy have for emergency planning. All municipalities are required to have emergency plans, which include a list of vulnerabilities associated with the areas where people live, spend their days, and form a community. This emergency plan, which the various social workers working in municipalities of varying sizes are familiar with, should be promoted more widely. The law already requires the mayor to organize evening presentations of the emergency plan. This often does not happen, but it is an important tool [Group3_ID4].

This work in the community is ongoing and a strength. What is sometimes lacking are resources; that is, it is necessary... everyone recognizes that it is necessary and fundamental. Today, if you don’t work in the community, you contribute nothing more than what is already there; you stand and observe reality, but there is no investment in this sector. [...] It is one of the fundamental things; this networking and mediation work is essential [Group3_ID4].

This seems to me to be part of the DNA of our profession, so yes, I feel it is very much ours, and perhaps what distinguishes us from other professions that are perhaps more specialized [Group3_ID3].

We often think of older people as being dependent on where they live, but we have also seen older people being cared for by people from other countries. These so-called careers have left them behind, so they have transitioned from a supportive environment in their own home, surrounded by familiar surroundings, to suddenly being isolated. Exactly, left alone but then ferried off to community settings they were not used to, uprooting people from their points of reference. Now I always think of the elderly, it was mainly them who, even in situations of severe isolation, especially in small villages, which are quite small, would not leave their homes for any reason, their animals, not just pets but also, I don’t know, chickens, for example, and there they were, because they knew they would never see their homes again. And here too, the attachment to the place, the attachment to their land, to their homes [Interviews_ID6].

5.5. Barriers

In my opinion, there is a lack of university training on this subject, i.e., extending these concepts to the university level, so that when someone comes to do this job, they know that this is also the basis, a starting point from which to view the world and their context. Another point is that, as you are aware, we provide continuous training; we are obligated to do so, and this is what is lacking here, even in terms of training proposals [Interviews_ID12].

What is interesting is that there are farmers who are aware of the potential damage that they could cause, but they report it to the city and the institutions. The institutions block him because it’s not his job to do the work, not only that, it’s not his job to decide, and not only that, but they also put him aside and say, “OK, we understand there’s a problem, we’ll take care of it”, but in the end, who knows when they’ll get around to it. Exactly, this has been the issue over the last two years, and, in my opinion, this has also accentuated the feeling of injustice. [...] they are very convinced that nothing will change, I mean, I don’t know how to say it, the perception when you talk about these things is that yes, there’s this, there’s that, there’s the other thing, there are all these problems, but in the end, nothing will ever change because we can’t decide anything. This is very much present [Interviews_ID8].

Bring these results to the attention of the authorities, because in my opinion, if we don’t start to realize that environmental issues are closely linked to social issues, we won’t get anywhere. However, this awareness must also be acquired at the political and administrative level, because unfortunately, our work is still very compartmentalized. We are still accustomed to the old mentality, where social services address social issues, health services handle health issues, and civil protection is perhaps more attentive to the environmental aspects of the territory. However, we can no longer think in this way [Interviews_ID7].

It is also true that, at least in organizations traditionally staffed by professionals and social workers, the ecological aspect is usually delegated to other departments and other colleagues, i.e., to other officials with different skills. It is also true that the opportunity to express this aspect of the profession is quite limited for those working for a public body or in traditional organizations, such as those where social workers are employed [Group2_ID4].

Social workers often identify with the organization where they work. They are unable to detach themselves and say,’ This is not my job; I have other tasks. I am a bureaucrat because those who pay me ask me to be, but I do not have a moral code or a professional philosophy, and I find this very worrying.’ I also agree with the structural issues raised [Group3_ID1].

Some citizens felt they had not received adequate assistance, particularly in the worst-affected neighborhoods. Citizens’ committees were established to protest the management of the relief efforts and, above all, the subsequent phase, i.e., the reconstruction, which was not truly reconstruction but rather reorganization, as the primary issue was the budget. I did not follow it personally, so what I know is limited because I heard about it from people who told me, rather than from families affected by the floods that I follow, or through my work. Still, I found out by reading the newspapers, listening to the news, and hearing people talk about it... But the problem was that the money didn’t reach the neighboring municipalities [Interviews_ID7].

5.6. Needs

Today, we realize that the needs are so many and so complex that we can no longer compartmentalize, because I may have in front of me an elderly person who is homeless and has an addiction, etc. So, can I only work on the addiction target, or only on the elderly target? Well, I think this is the work that needs to be done for the environmental issue as well, because we must work in collaboration with others, but this must go higher up, because maybe we as individual operators may have it in mind because of personal stories or interests. Still, in my opinion, there is no thinking at the political level [Interviews_ID7].

This new vision of environmental justice, which I believe should also be included in our university education because only in this way, only if we manage to build a critical awareness of the problem, even in places that... by institution, should do this, such as universities or training courses, a bit like we are experimenting with... can also help to highlight and bring to the fore the issues [Group2_ID2].

For example, Asproc, but I was thinking now, listening to you, that even there the attitude is... let’s alleviate the devastating effects of disasters once they have already happened, but never a particular thought about prevention or... thinking before acting on the causes, so again very limited, besides the fact that Asproc is a small association and also completely unknown to most people in our field, which is very interesting and valuable, but very small and partial, in short [Group3_ID3].

Therefore, we need to initiate a cultural change, which can be triggered as a regulation or procedure, to ensure that I also achieve this, in addition to the other existing measures. We also need to codify the issue of environmental justice, which is very important [...] because environmental justice is certainly a concept that is part of a much broader discourse on justice. So, it is somewhat transversal to all other concepts of justice, and as such, I would also see it well integrated into the context. We should put it down in black and white, i.e., start a cultural change from the central institutions of the state down to the municipalities, i.e., down to the institutions closest to the citizen, and start thinking in these terms because when we plan, design, propose, make agreements, carry out a whole series of activities that are done to guarantee services to citizens, we should also keep in mind the issue of environmental justice, especially from a modern perspective, considering all the transformations that are taking place at this moment in history, right? So, beyond everything we have said, everything is welcome. Still, I would say we need to start putting it down on paper, in the sense of starting to propose to our administrations that we introduce the concept, but not just in theory, with practical implications and therefore in everything we do, continuing to push towards a theme of environmental justice that can be cross-cutting but also a bit 360°, right? So, understanding everything a little bit, because in all activities, there can be the issue of environmental justice. It’s not easy because we’re still in the early stages of this discussion on environmental justice, but we need to take the first steps, put them into practice, and build on them over time. So, I would say that this is my vision [Group1_ID1].

When we manage to include an article in our regulations that talks about environmental justice, then we can say that we have taken the first step towards a process of change [Group1_ID1].

Therefore, we need to recognize the voices of everyone who has experienced hardship, including the people and farmers, and ensure that there is less bureaucracy in the institutions, which can be reduced, and greater awareness and knowledge of environmental issues, which are discussed but not sufficiently addressed [Interviews_ID7].

If, on the other hand, we manage to integrate social awareness as far as possible, we can also activate measures to recognize rights that, in those contexts, would otherwise remain on the margins. So, I imagine perhaps also social services [Group2_ID5].

5.7. Towards Cross-Cutting Environmental Skills

6. Discussion

- (1)

- Detached approach. The first profile is characterized by low awareness, limited knowledge, and a lack of actions on environmental issues. This generally includes social workers who complain of a lack of environmental culture, a lack of training on environmental justice issues, and who do not see that some social action could also fall within the scope of environmental justice (e.g., the problem of housing). Although the code of ethics also affirms the need to address environmental issues, this profile considers that all environmental concerns are not part of social work in its strict sense.

- (2)

- Sensitive/Conscious approach. The second profile is characterized by high environmental awareness, primarily due to individual sensitivity and extraprofessional interests; however, it is accompanied by low or limited knowledge of environmental justice issues and a lack of action taken on these issues. This profile highlights the critical issues and organizational problems of institutions, such as the sectionalization of various and diverse skills, and considers these objective barriers to be challenging to change. When addressing environmental issues, they often employ inappropriate tools. In other words, they frequently use outdated social work tools to address new environment-oriented problems, which are ineffective. Everything revolves around their interests and personal environmental awareness, which, however, clash with the institutional organization and the mandate expressly requested of social workers, which is certainly not to deal with the environment. Nevertheless, they value the need for actions aimed at building a sense of community and citizen participation, identity and a sense of attachment to the place. Not only that, they also highlight the problem of sectoralisation and the need to legitimise the issue of environmental justice within the work of social services. Finally, they stress that there is an urgent need to create new skills through specialist training and an environmental culture.

- (3)

- Expert approach. The third and final profile that emerged is characterized by high awareness, extensive knowledge of environmental issues, and action aimed at developing environmental justice. This includes participants who are members of Asproc, which aims to assist and support the work of social services in areas affected by emergencies related to floods and/or earthquakes. Participants include those with experience in social work during the floods in Emilia-Romagna and Tuscany, the earthquakes in Norcia (Perugia) in 2016, Amatrice in 2016–2017, the floods in Tuscany in 2023, and the floods in Emilia-Romagna in 2023 and 2024. This profile is characterized by a high level of awareness, extensive knowledge, and practical experience in the field, particularly in emergencies. Among the characteristic narratives are the need to utilize emergency plans in every city, the importance of adopting a preventive rather than an emergency approach, and the significance of considering the sense of community and identity associated with place and historical memory, even in times of emergency. As anticipated, while we recognize that these professionals’ perspectives may bias our study by overestimating the level of understanding and engagement with environmental issues, we believe it has been enriching to bring such a privileged perspective to the discussion.

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IPCC—Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rockström, J.; Steffen, W.; Noone, K.; Persson, Å.; Chapin, F.S., III; Lambin, E.F.; Lenton, T.M.; Scheffer, M.; Folke, C.; Schellnhuber, H.J.; et al. A safe operating space for humanity. Nature 2009, 461, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, H.L.; Bowen, K.; Kjellstrom, T. Climate change and mental health: A causal pathways framework. Int. J. Public Health 2010, 55, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutter, S.L.; Boruff, B.J.; Shirley, W.L. Social vulnerability to environmental hazards. Soc. Sci. Q. 2003, 84, 242–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlosberg, D. Defining Environmental Justice: Theories, Movements, and Nature; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bullard, R.D. Dumping in Dixie: Race, Class, and Environmental Quality; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Agyeman, J.; Bullard, R.D.; Evans, B. (Eds.) Just Sustainabilities: Development in an Unequal World; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, G. Environmental Justice: Concepts, Evidence and Politics; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pellow, D.N. What is Critical Environmental Justice? John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Knoble, C.; Yu, D. Environmental justice: An evolving concept in a dynamic era. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 31, 2091–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnstein, S.R. A Ladder of Citizen Participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, N. Rethinking recognition. New Left Rev. 2000, 3, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D.E. The rise of the environmental justice paradigm: Injustice framing and the social construction of environmental discourses. Am. Behav. Sci. 2000, 43, 508–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brondi, S.; Chiara, G.; Matutini, E. Navigating Environmental Justice Framework: A Scoping Literature Review over Four Decades. Environ. Justice 2025, 18, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlosberg, D.; Collins, L.B. From environmental to climate justice: Climate change and the discourse of environmental justice. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2014, 5, 359–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuana, N. Viscous porosity: Witnessing Katrina. Mat Fem. 2008, 188, 188–213. [Google Scholar]

- Temper, L.; Del Bene, D. Transforming knowledge creation for environmental and epistemic justice. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2016, 20, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottinger, G. Careful knowing as an aspect of environmental justice. Environ. Politics 2024, 33, 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fricker, M. Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fricker, M. Evolving concepts of epistemic injustice. In The Routledge Handbook of Epistemic Injustice; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Dotson, K. Conceptualizing epistemic oppression. Soc. Epistemol. 2014, 28, 115–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes Barbosa, L.; Walker, G. Epistemic injustice, risk mapping and climatic events: Analysing epistemic resistance in the context of favela removal in Rio de Janeiro. Geogr. Helv. 2020, 75, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tengö, M.; Brondizio, E.S.; Elmqvist, T.; Malmer, P.; Spierenburg, M. Connecting diverse knowledge systems for enhanced ecosystem governance: The multiple evidence base approach. Ambio 2014, 43, 579–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, M. Bioethanol sacrifice zones and environmental/epistemic injustice. A case study in Argentina. Environ. Sci. Pol. 2024, 157, 103782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCauley, J.; Mokos, J. Amplified Voices, Organized Ignorance, and Epistemic Justice: Examining the Impact of Community-Science Partnerships for Environmental Justice. J. Sustain. Educ. 2024, 30, 2151–7452. [Google Scholar]

- Jasanoff, S. Science and Public Reason; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gosselin, L.; Gauquelin, M. Rethinking Knowledge Cumulation: Foregrounding Epistemic Justice in Environmental Governance Research. Environ. Policy Gov. 2025, 35, 729–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaržija, H.; Cerovac, I. The institutional preconditions of epistemic justice. Soc. Epistemol. 2021, 35, 621–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Brabander, R. Voices of climate justice. Ecosocial work and the politics of recognition. J. Soc. Interv. Theory Pract. 2023, 32, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominelli, L. Green Social Work: From Environmental Crises to Environmental Justice; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, K. Working with Nature: Environmental Social Work and the Biosphere; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Parra Ramajo, B.; Prat Bau, N. The Responsibilities of Social Work for Ecosocial Justice. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, L.R.; Coye, S.R.; Rao, S.; Krings, A.; Santucci, J. Environmental Justice and Social Work: A Study across Practice Settings in Three U.S. States. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicario, S.; Gui, L.; Sinigaglia, M. Embedding sustainability in local welfare systems: Bottom-up contributions from social workers and care professionals in public and third sector organisations. Eur. J. Soc. Work 2024, 28, 168–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, C. Prospettive di Eco-Social Work ne Lavoro Sociale di Comunità; FrancoAngeli: Milan, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Fook, J. Social Work: A Critical Approach to Practice; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Miner-Romanoff, K.; Greenawalt, J. Evaluation of the Arthur Project: Evidence-Based Mentoring in a Social Work Framework with a Social Justice Approach. Societies 2024, 14, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ife, J. Community Development in an Uncertain World: Vision, Analysis and Practice; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Healy, K. Social Work Theories in Context: Creating Frameworks for Practice, 3rd ed.; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dominelli, L. Promoting environmental justice through green social work practice. Int. Soc. Work 2014, 57, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, S.; Krings, A. Sustainable social work: An environmental justice framework for social work education. Soc. Work Educ. 2015, 34, 513–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randolph, K.A.; Mathias, J.; Boel-Stuth, S. Preparing social workers to promote environmental justice: An exploratory study. J. Soc. Work. Educ. 2024, 60, 388–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matutini, E. Eco-Social Work: Politica e Lavoro Sociale Nella Crisi Ecologica; PM Edizioni: Segrate, Italy, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pavani, L.; Ganugi, G. Social sustainability: What implications for social work? Eur. J. Soc. Work 2024, 27, 1271–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chancel, L. Unsustainable Inequalities: Social Justice and the Environment; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dominelli, L. Environmental justice at the heart of social work practice: Greening the profession. Int. J. Soc. Welf. 2013, 22, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrán, R.; Hacker, A.; Begun, S. Environmental justice is a social justice issue: Incorporating environmental justice into social work practice curricula. J. Soc. Work Educ. 2016, 52, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, D. Environmental justice and social work: A call to expand the social work profession to include environmental justice. Columbia Soc. Work Rev. 2013, 11, 36–45. [Google Scholar]

- Jovchelovitch, S.; Bauer, M.W. Narrative Interviewing; LSE Research Online: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Riessman, C.K. Narrative Methods for the Human Sciences; Sage: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, C.; Scott, S.; Geddes, A. Snowball Sampling; Sage Research Methods Foundations: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, U. An Introduction to Qualitative Research, 7th ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide; Sage: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

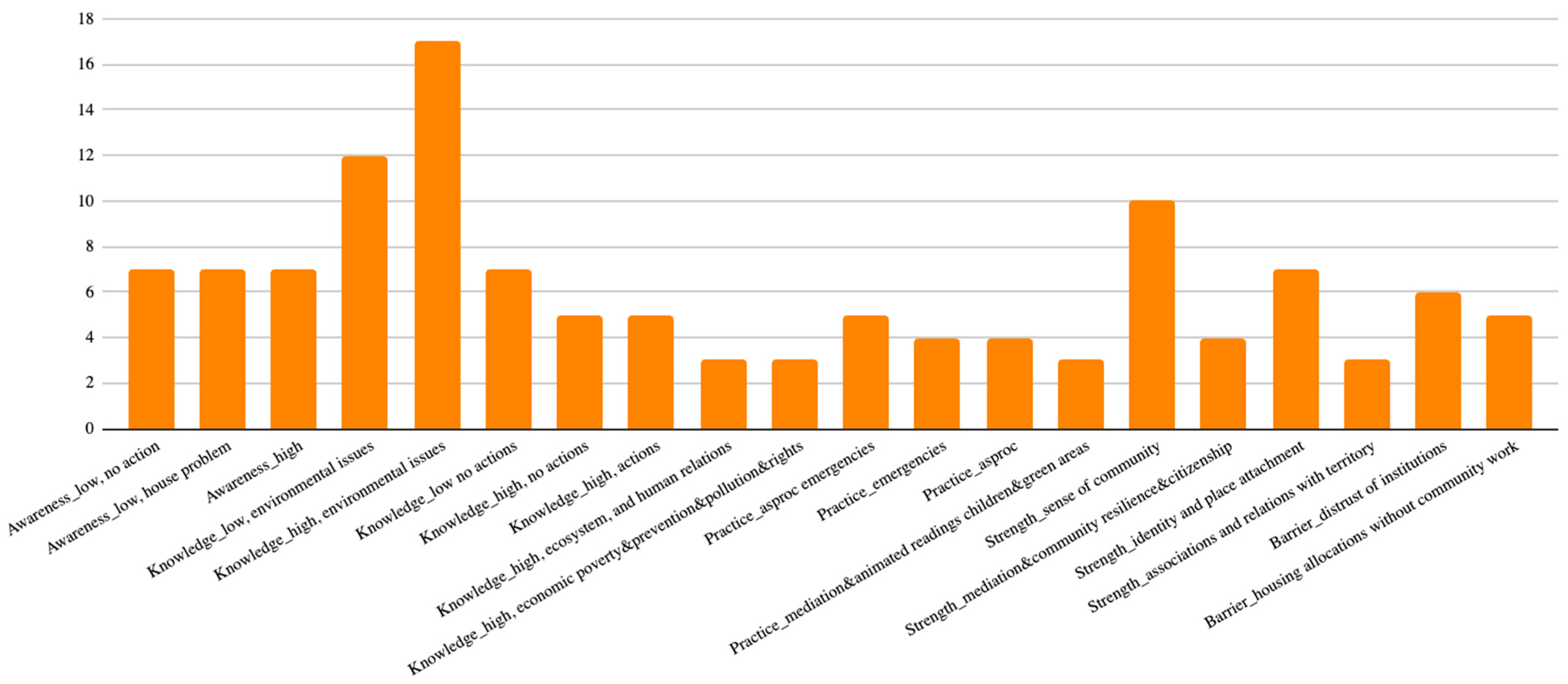

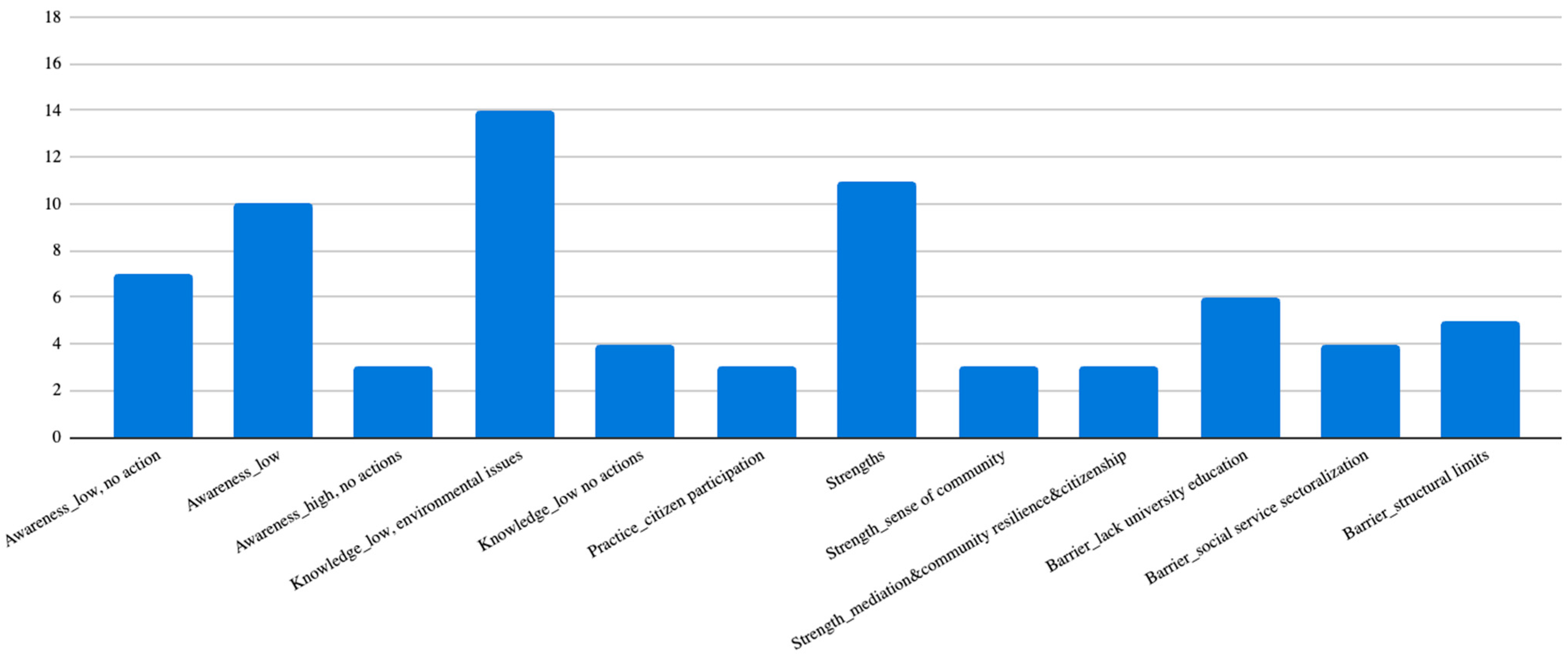

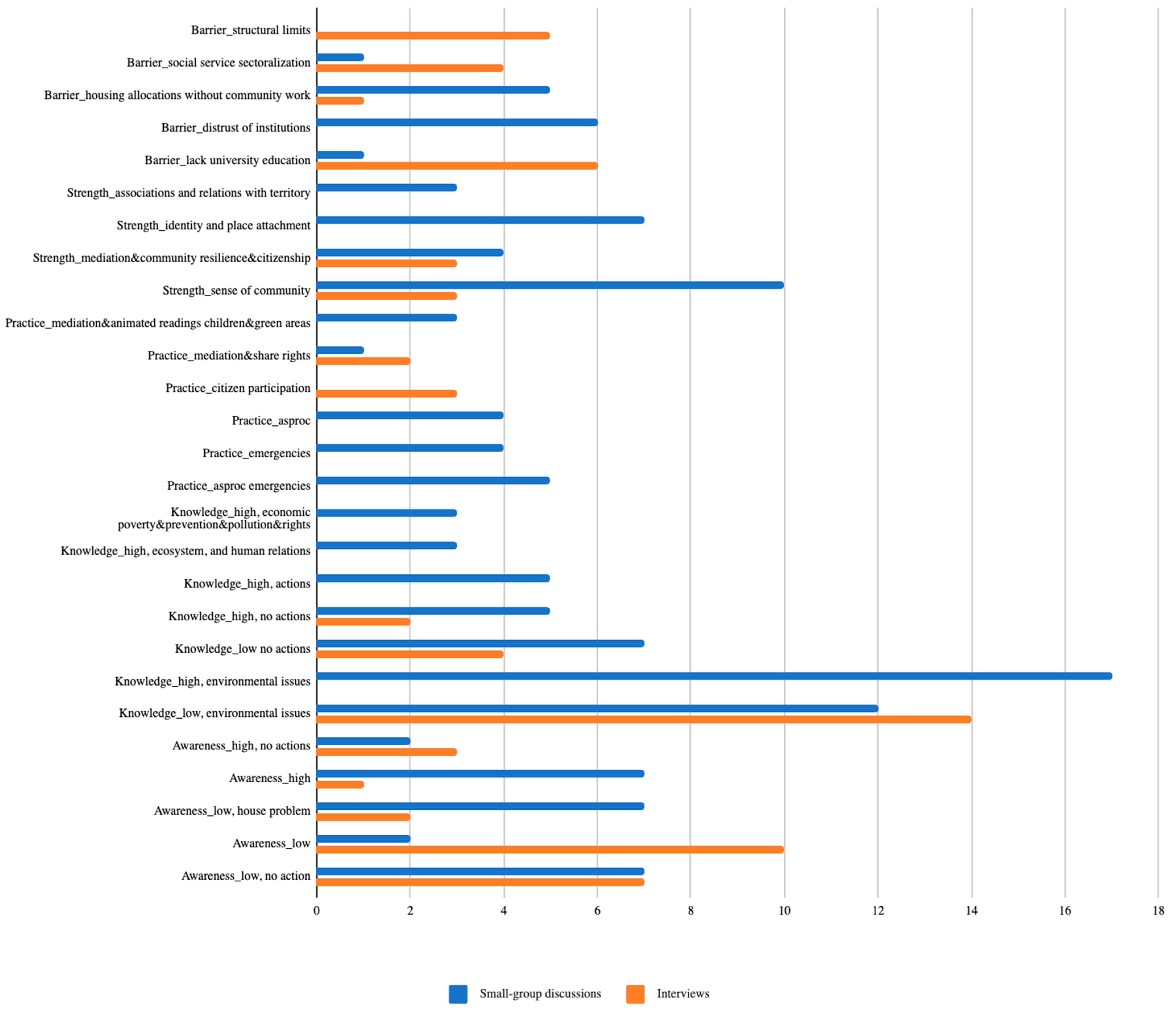

| Themes: Awareness, Knowledge and Practices | Sub-Themes (F > 3) |

|---|---|

| EJ Awareness | Awareness_high |

| Awareness_high, no actions | |

| Awareness_low | |

| Awareness_low, no actions | |

| Awareness_low, house problem | |

| EJ Knowledge | Knowledge_high, environmental issues |

| Knowledge_high, ecosystem, and human relations | |

| Knowledge_high, economic poverty&prevention&pollution&rights | |

| Knowledge_high, actions | |

| Knowledge_high, no actions | |

| Knowledge_low, environmental issues | |

| Knowledge_low no actions | |

| EJ Practices | Practice_asproc |

| Practice_asproc emergencies | |

| Practice_emergencies | |

| Practice_citizen participation | |

| Practice_mediation&share rights | |

| Practice_mediation&animated readings children&green areas | |

| Strenghts, Barriers, and Needs | |

| EJ&SW Strenghts | Strength_sense of community |

| Strength_mediation&community resilience&citizenship | |

| Strength_identity and place attachment | |

| Strength_associations and relations with territory | |

| EJ&SW Barriers | Barrier_lack university education |

| Barrier_distrust of institutions | |

| Barrier_housing allocations without community work | |

| Barrier_social service sectoralization | |

| Barrier_structural limits | |

| Barrier_distributive injustice | |

| Barrier_communication | |

| Barrier_poverty&culture does not accept inequality | |

| EJ&SW Needs | Need_sense of community&partecipation |

| Need_EJ education | |

| Need_collaboration with other services | |

| Need_environemntal competence | |

| Need_prevention | |

| Need_recognition justice | |

| Need_create environmental culture | |

| Need_territorial map | |

| Need_EJ codification in social service | |

| Need_community development | |

| Need_beyond sectorialization | |

| Need_advocacy actions | |

| Need_cooperation agreements |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Matutini, E.; Chiara, G.; Brondi, S. Agency and Advocacy in Social Work: Promoting Social and Environmental Justice Through Professional Practice. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9208. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209208

Matutini E, Chiara G, Brondi S. Agency and Advocacy in Social Work: Promoting Social and Environmental Justice Through Professional Practice. Sustainability. 2025; 17(20):9208. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209208

Chicago/Turabian StyleMatutini, Elisa, Giacomo Chiara, and Sonia Brondi. 2025. "Agency and Advocacy in Social Work: Promoting Social and Environmental Justice Through Professional Practice" Sustainability 17, no. 20: 9208. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209208

APA StyleMatutini, E., Chiara, G., & Brondi, S. (2025). Agency and Advocacy in Social Work: Promoting Social and Environmental Justice Through Professional Practice. Sustainability, 17(20), 9208. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209208