Thematic Evolution and Transmission Mechanisms of China’s Rural Tourism Policy: A Multi-Level Governance Framework for Sustainable Development

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background and Problem Formulation

1.2. Literature Review and Theoretical Basis

1.2.1. Core Analytical Perspective: Multi-Level Governance (MLG) Theory

1.2.2. Contextualizing the Theory: China’s Policy Process and Central-Local Relations

1.2.3. Research Focus: Rural Tourism Policy

1.3. Research Gaps, Core Questions, and Paper Structure

2. Research Design and Methods

2.1. Research Context and Object

2.2. Data Source and Processing

2.3. BERTopic Topic Modeling Method

3. Results

3.1. Spatio-Temporal Evolution of Rural Tourism Policies in China

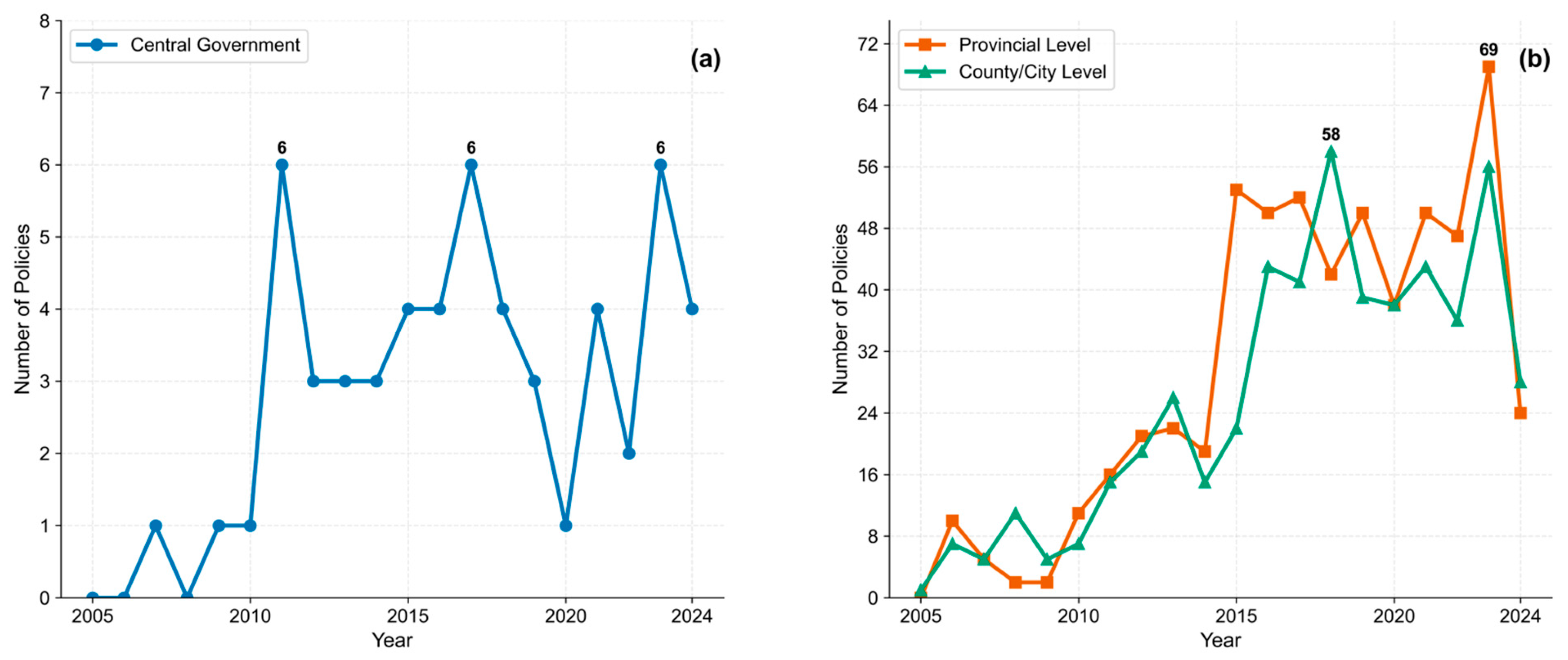

3.1.1. Temporal Characteristics of Policy Issuance and Inter-Level Interactions

3.1.2. Spatial Patterns and Regional Agglomeration of Policy Issuance

3.2. Thematic Structure and Evolution of Rural Tourism Policies from a Multi-Level Governance Perspective

3.2.1. Hierarchical Differentiation and Functional Positioning of Policy Themes

3.2.2. Temporal Evolution of Policy Themes and Vertical Transmission Mechanisms

3.3. Spatial Clustering Patterns and Regional Differences in Rural Tourism Policy Themes

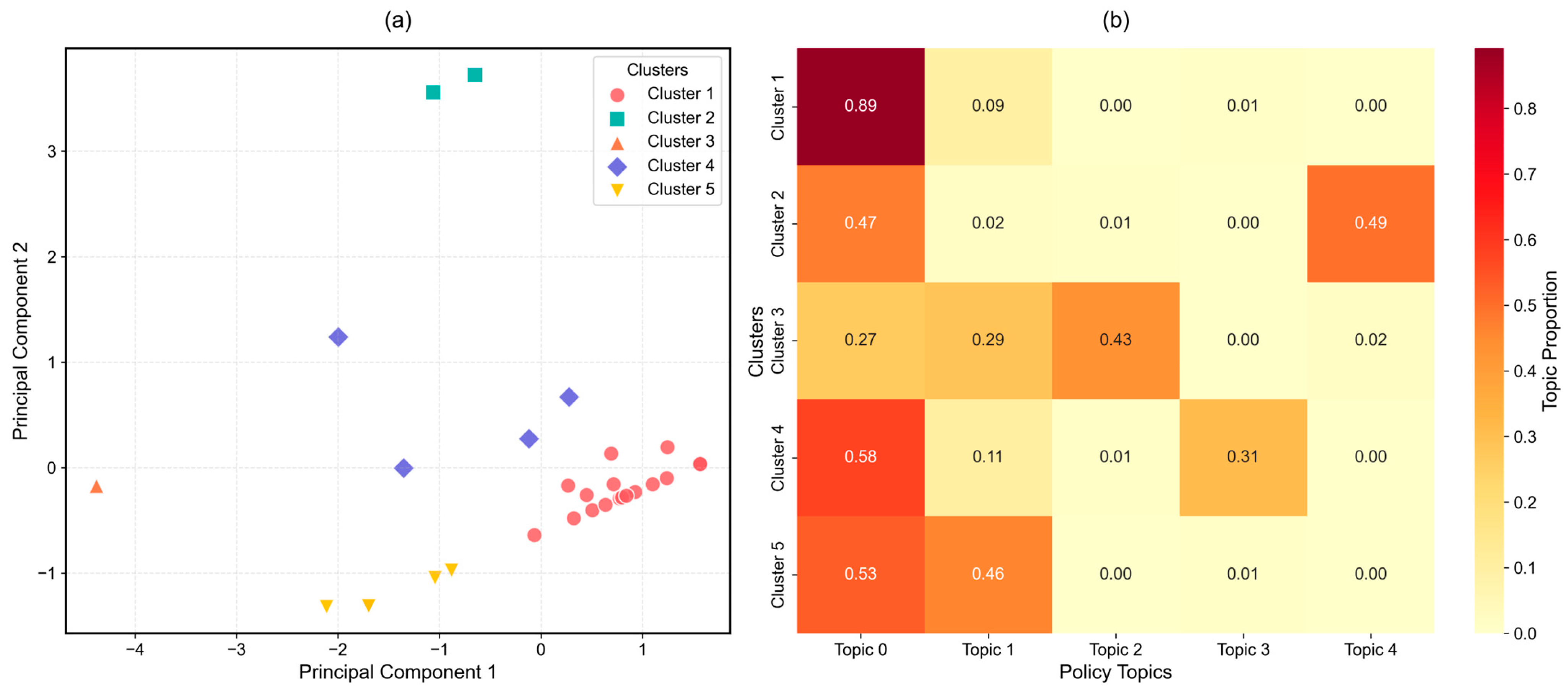

3.3.1. Regional Clustering Characteristics of Provincial Rural Tourism Policy Themes

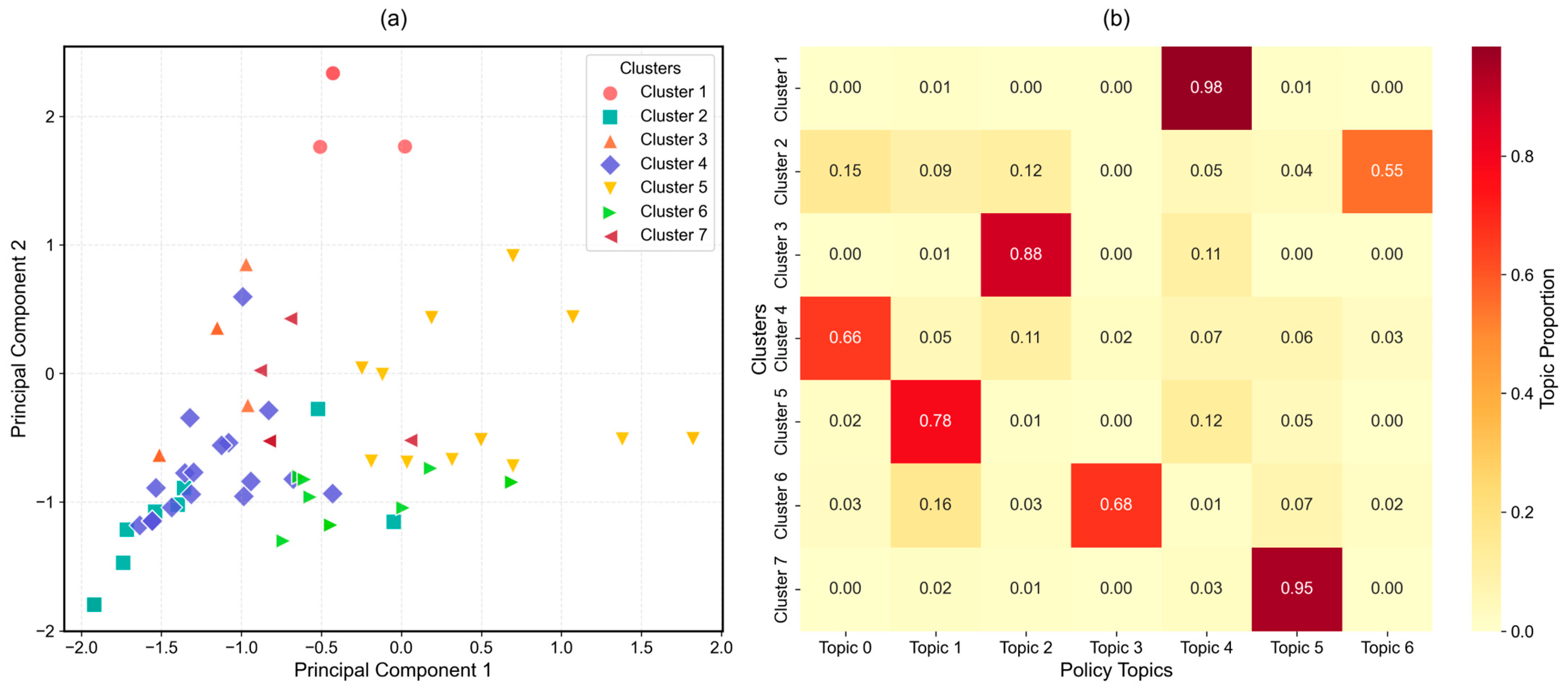

3.3.2. Clustering Patterns and Regional Differentiation of City/County-Level Rural Tourism Policy Themes

4. Discussion

4.1. The Operational Logic of Multi-Level Governance in China’s Rural Tourism Policy

4.2. “Learning” and “Adaptation” in the Transmission of China’s Rural Tourism Policy

4.3. Uniqueness of the Governance Model from an International Comparative Perspective

5. Conclusions and Implications

5.1. Core Research Findings

5.2. Theoretical and Practical Contributions

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ammirato, S.; Felicetti, A.M.; Raso, C.; Pansera, B.A.; Violi, A. Agritourism and sustainability: What we can learn from a systematic literature review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streimikiene, D.; Svagzdiene, B.; Jasinskas, E.; Simanavicius, A. Sustainable tourism development and competitiveness: The systematic literature review. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Agarwala, T.; Kumar, S. Rural tourism as a driver of sustainable development: A systematic review and future research agenda. Tour. Rev. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.-Y.; Gao, M.; Kim, H.; Shah, K.J.; Pei, S.-L.; Chiang, P.-C. Advances and challenges in sustainable tourism toward a green economy. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 635, 452–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosalina, P.D.; Dupre, K.; Wang, Y. Rural tourism: A systematic literature review on definitions and challenges. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 47, 134–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Guo, T.; Nijkamp, P.; Xie, X.; Liu, J. Farmers’ livelihood adaptability in rural tourism destinations: An evaluation study of rural revitalization in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Cheng, L.; Iqbal, J.; Cheng, D. An integrated rural development mode based on a tourism-oriented approach: Exploring the beautiful village project in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhou, M.; Wang, S. Localized practices of rural tourism makers from a resilience perspective: A comparative study in China. J. Rural Stud. 2025, 119, 103722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Chai, S.; Chen, J.; Phau, I. How was rural tourism developed in China? Examining the impact of China’s evolving rural tourism policies. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 28945–28969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhai, S.; Xin, M.; Xi, Y. Research on Rural Tourism Poverty Alleviation Strategy from the Perspective of Rural Revitalization. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Social Science, Education and Humanities Research (SSEHR 2018), Xi’an, China, 22–24 June 2018; pp. 680–683. Available online: https://webofproceedings.org/proceedings_series/ESSP/SSEHR%202018/SSEHR1220142.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Piattoni, S. The Theory of Multi-level Governance: Conceptual, Empirical, and Normative Challenges; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollack, M.A. Theorizing the European Union: International organization, domestic polity, or experiment in new governance? Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 2005, 8, 357–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, T.; Miedema, M. A governance approach to regional energy transition: Meaning, conceptualization and practice. Sustainability 2020, 12, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotirov, M.; Winkel, G.; Eckerberg, K. The coalitional politics of the European Union’s environmental forest policy: Biodiversity conservation, timber legality, and climate protection. Ambio 2021, 50, 2153–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redaelli, E. Understanding American cultural policy: The multi-level governance of the arts and humanities. Policy Stud. 2020, 41, 80–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katikireddi, S.V.; Hilton, S.; Bonell, C.; Bond, L. Understanding the development of minimum unit pricing of alcohol in Scotland: A qualitative study of the policy process. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e91185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeffery, C.; Peterson, J. ‘Breakthrough’ political science: Multi-level governance-Reconceptualising Europe’s modernised polity. Br. J. Polit. Int. Relat. 2020, 22, 753–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooghe, L.; Marks, G. Unraveling the central state, but how? Types of multi-level governance. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 2003, 97, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales-Iwanciw, J.; Dewulf, A.; Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen, S. Learning in multi-level governance of adaptation to climate change—A literature review. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2020, 63, 779–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, B.J.; Brummel, L.; Toshkov, D.; Yesilkagit, K. Multilevel governance and responses to the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic literature review. Reg. Fed. Stud. 2023, 35, 305–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.H. Studies of central-provincial relations in the People’s Republic of China: A mid-term appraisal. China Q. 1995, 142, 487–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostka, G.; Nahm, J. Central-local relations: Recentralization and environmental governance in China. China Q. 2017, 231, 567–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X. Dynamics of central-local relations in China’s social welfare system. J. Chin. Gov. 2016, 1, 251–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, J.A.; Yang, X. Shifting strategies: The politics of radical change in provincial development policy in China. China Q. 2022, 249, 139–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mah, D.N.Y.; Hills, P.R. Policy learning and central-local relations: A case study of the pricing policies for wind energy in China (from 1994 to 2009). Environ. Policy Gov. 2014, 24, 216–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Han, S.S.; Chen, S. Understanding the structure and complexity of regional greenway governance in China. Int. Dev. Plan. Rev. 2022, 44, 241–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertha, A.C. China’s “soft” centralization: Shifting Tiao/Kuai authority relations. China Q. 2005, 184, 791–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, K.; Mah, D.N.-Y. State capitalism, fragmented authoritarianism, and the politics of energy policymaking: Policy networks and electricity market liberalization in Guangdong, China. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 107, 103348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lema, A.; Ruby, K. Between fragmented authoritarianism and policy coordination: Creating a Chinese market for wind energy. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 3879–3890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, A.; Jiang, L.; Guo, B.; Li, W. Subsidy policy interactions in agricultural supply chains: An interdepartmental coordination perspective. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, Z.; Yuan, C.; Liu, L. Exploration on the reasons for low efficiency of arable land protection policy in China: An evolutionary game theoretic model. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 25173–25198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, K. The politics of just transition: Authoritarian environmentalism and implementation flexibility in forest conservation. Polit. Geogr. 2024, 109, 103066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heffer, A.S.; Schubert, G. Policy experimentation under pressure in contemporary China. China Q. 2023, 253, 35–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Zhao, H. Experimentalist governance with interactive central-local relations: Making new pension policies in China. Policy Stud. J. 2021, 49, 13–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yang, D.Y. Policy experimentation in China: The political economy of policy learning. J. Polit. Econ. 2025, 133, 2180–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiper, T.; Korkut, A.; Yilmaz, E. Determination of rural tourism strategies by rapid rural assessment technique: The case of Tekirdag Province, Sarkoy County. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2011, 9, 491–496. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, J.; Lee, S. The effect of the rural tourism policy on non-farm income in South Korea. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.C.Y.; Kusadokoro, M.; Chang, H.-H.; Kitamura, Y. Rural tourism promotion policy and rural hospitality enterprises performance: Empirical evidence from Japan. Agribusiness 2025, 41, 815–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Li, H. Effect of agriculture-tourism integration on in situ urbanization of rural residents: Evidence from 1868 counties in China. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2024, 16, 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, B.; Zhao, C.; Luo, M.; Jia, Z.; Xia, H. Beyond the scenery: Understanding the impact of rural tourism development on household consumption in China. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2024, 28, 1152–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Dang, X.; Song, T.; Xiao, G.; Lu, Y. Agro-tourism integration and county-level sustainability: Mechanisms and regional heterogeneity in China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Li, S. Multi-level governance of low-carbon tourism in rural China: Policy evolution, implementation pathways, and socio-ecological impacts. Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 12, 1482713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smets, T.; Verbeeck, N.; Claesen, M.; Asperger, A.; Griffioen, G.; Tousseyn, T.; Waelput, W.; Waelkens, E.; De Moor, B. Evaluation of distance metrics and spatial autocorrelation in uniform manifold approximation and projection applied to mass spectrometry imaging data. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 5706–5714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, A.C.A.; Sander, J.; Campello, R.J.G.B.; Nascimento, M.A. Efficient computation and visualization of multiple density-based clustering hierarchies. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2021, 33, 3075–3089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugavadivel, K.; Subramanian, M.; Vasantharan, K.; Prethish, G.A.; Sankar, S. Event Categorization from News Articles Using Machine Learning Techniques. In Communications in Computer and Information Science; Springer: Singapore, 2024; Volume 2046, pp. 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Sun, G.-N.; Ma, S.-Q. Assessing holistic tourism resources based on fuzzy evaluation method: A case study of Hainan tourism Island. In Fuzzy Information and Engineering and Decision, Proceedings of the 2016 International Workshop on Mathematics and Decision Science (IWMDS 2016), Guangzhou, China, 12–15 September 2016; Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Cao, B.-Y., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 646, pp. 434–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Cui, J. Spatio-temporal characteristics and evolution of ice and snow tourism resources in Northeast China from 1990 to 2022. J. Glaciol. Geocryol. 2025, 47, 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Fan, P.; Yue, W.; Huang, J.; Li, D.; Tian, Z. Assessing polycentric urban development in mountainous cities: The case of Chongqing metropolitan area, China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, K.; Broto, V.C. Co-benefits, contradictions, and multi-level governance of low-carbon experimentation: Leveraging solar energy for sustainable development in China. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2019, 59, 101993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, O.S.K.; Wernli, D.; Liu, P.; Tun, H.M.; Fukuda, K.; Lam, W.; Xiao, Y.; Zhou, X.; Grépin, K.A. Unpacking multi-level governance of antimicrobial resistance policies: The case of Guangdong, China. Health Policy Plan. 2022, 37, 1148–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lysek, J.; Rysavy, D. Empowering through regional funds? The impact of Europe on subnational governance in the Czech Republic. Reg. Fed. Stud. 2020, 30, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlhorst, D. Germany’s energy transition policy between national targets and decentralized responsibilities. J. Integr. Environ. Sci. 2015, 12, 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brueck, C.; Losacker, S.; Liefner, I. China’s digital and green (twin) transition: Insights from national and regional innovation policies. Reg. Stud. 2025, 59, 2384411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, G.; Hooghe, L.; Blank, K. European integration from the 1980s: State-centric v multi-level governance. J. Common Mark. Stud. 1996, 34, 341–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L.; Shi, C. Multi-level governance in centralized state? Evidence from China after the territorial reforms. Lex Localis 2022, 20, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Wang, R. Central-local relations and higher education stratification in China. High. Educ. 2020, 79, 111–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, A.; Pasquier, R. The Breton model between convergence and capacity. Territ. Polit. Gov. 2015, 3, 51–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, R.K.; Lowndes, V. How does multi-level governance create capacity to address refugee needs, and with what limitations? An analysis of municipal responses to Syrian refugees in Istanbul. J. Refug. Stud. 2022, 35, 51–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolowitz, D.P.; Marsh, D. Learning from abroad: The role of policy transfer in contemporary policy-making. Governance 2000, 13, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipan, C.R.; Volden, C. The mechanisms of policy diffusion. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 2008, 52, 840–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, B.A.; Elkins, Z. The globalization of liberalization: Policy diffusion in the international political economy. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 2004, 98, 171–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, D. Transfer and translation of policy. Policy Stud. 2012, 33, 483–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilmann, S. Policy experimentation in China’s economic rise. Stud. Comp. Int. Dev. 2008, 43, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamori, N.; Sun, J.; Zhang, S. The announcement effects of regional tourism industrial policy: The case of the Hainan international tourism island policy in China. Tour. Econ. 2017, 23, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kun, X.; Ullah, W.; Liu, D.; Wang, Z. Exploring the spatial patterns and influencing factors of rural tourism development in Hainan Province of China. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, M.M.; Wall, G.; Wang, Y.; Jin, M. Livelihood sustainability in a rural tourism destination-Hetu Town, Anhui Province, China. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, N.; Wei, F.; Zhang, K.H.; Gu, D. Innovating rural tourism targeting poverty alleviation through a multi-industries integration network: The case of Zhuanshui Village, Anhui Province, China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberlein, B.; Grande, E. Beyond delegation: Transnational regulatory regimes and the EU regulatory state. J. Eur. Public Policy 2005, 12, 89–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Börzel, T.A.; Heard-Lauréote, K. Networks in EU multi-level governance: Concepts and contributions. J. Public Policy 2009, 29, 135–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newig, J.; Koontz, T.M. Multi-level governance, policy implementation and participation: The EU’s mandated participatory planning approach to implementing environmental policy. J. Eur. Public Policy 2014, 21, 248–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, A.; Eberlein, B. The Europeanization of regional policies: Patterns of multi-level governance. J. Eur. Public Policy 1999, 6, 329–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehnert, F.; Kern, F.; Borgström, S.; Gorissen, L.; Maschmeyer, S.; Egermann, M. Urban sustainability transitions in a context of multi-level governance: A comparison of four European states. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2018, 26, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Level | Topic ID | Topic Name | Document Count | Representative Keywords |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central | 0 | Rural Revitalization Support and Innovation | 24 | Support, Funding, Talent, Innovation, Rural Revitalization |

| Central | 1 | Agritourism Demonstration Parks and Counties | 12 | Sightseeing Garden, Demonstration Zone, Park, Demonstration County, Eco-park |

| Central | 2 | Rural Tourism Governance and Policy Implementation | 15 | Practitioners, Demonstration County, Policy Measures, Leadership, Tourism Department |

| Central | 3 | Rural Homestay Development and Regulation | 5 | Renovation, Housing, Supervision, Context-based Approach, Integration |

| Provincial | 0 | Rural Characteristic Agriculture and Leisure Tourism | 431 | Characteristic, Agriculture, Leisure, Resources, Ecology |

| Provincial | 1 | Rural Tourism Rating and Assessment | 86 | Assessment, Scenic Area, Rating, Ecology, Farm |

| Provincial | 2 | Coconut-Grade Rural Tourism Sites Assessment | 26 | Coconut Grade, Assessment, Rating, Tourism Site, Quality |

| Provincial | 3 | Key Rural Tourism Villages Selection | 25 | Key Rural Tourism Village, Selection, Evaluation, Tourism Leader, Demonstration Village |

| Provincial | 4 | Poverty Alleviation through Rural Tourism | 27 | Poverty Alleviation Office, Poverty Alleviation, District, Achievement, Development |

| City/County | 0 | Star-rated Rural Tourism Zone Assessment | 112 | Preliminary Assessment, Three-star, Four-star, Tourism Zone, Assessment Criteria |

| City/County | 1 | Rural Tourism Financial Support and Land Use | 113 | Loan, Finance, Renovation, Credit, Land Use |

| City/County | 2 | Beautiful Leisure Village Selection | 57 | Select the Best, Beautiful Leisure Village, Preliminary Review, Demonstration County, Voluntary |

| City/County | 3 | Rural Tourism Development Proposal and Strategy | 53 | Key Tourism Village, Proposal, Context-based Approach, Rural Revitalization, Research Tourism |

| City/County | 4 | Rural Tourism Supervision and Modernization | 93 | Guidance, Renovation, Supervision, Land, Modernization |

| City/County | 5 | Rural Revitalization Concept and Development | 56 | Development Concept, Rural Revitalization Strategy, Renovation, Land Use, Health and Wellness |

| City/County | 6 | Rural Tourism Expert Evaluation System | 38 | Appointment, Expert Group, Three-star, Evaluation, Quality Control |

| Cluster | Number of Provinces | Total Policies | Provinces |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 19 | 384 | Jilin, Guangxi, Shandong, Anhui, Beijing, Guizhou, Hebei, Shanghai, Fujian, Gansu, Sichuan, Guangdong, Inner Mongolia, Shaanxi, Zhejiang, Hunan, Liaoning, Heilongjiang, Tianjin |

| 2 | 2 | 51 | Chongqing, Hubei |

| 3 | 1 | 56 | Hainan |

| 4 | 4 | 50 | Shanxi, Xinjiang, Jiangsu, Yunnan |

| 5 | 5 | 54 | Jiangxi, Henan, Ningxia, Tibet, Qinghai |

| Cluster | Number of Cities | Total Policies | Representative Cities |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 26 | 43 | Lüliang, Guigang, Sanya, Chongzuo, Wanning, Hezhou, Nanchong, Lijiang |

| 2 | 9 | 64 | Fuzhou, Nanchang, Guangzhou, Xuzhou, Quzhou, Nanjing |

| 3 | 11 | 25 | Xiamen, Changchun, Zhongshan, Changsha, Wuhan, Deyang |

| 4 | 20 | 167 | Hefei, Haikou, Qingdao, Guilin, Guiyang, Nanning, Suzhou |

| 5 | 60 | 141 | Xining, Huzhou, Haidong, Zaozhuang, Wuxi, Lhasa, Qinzhou |

| 6 | 10 | 60 | Yinchuan, Zhengzhou, Zibo, Suzhou, Anshan, Fushun |

| 7 | 18 | 28 | Huainan, Yulin, Luoyang, Tianshui, Beihai, Xuchang |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hu, H.; Yin, Y.; Xie, Y.; Cai, J.; Wang, C.; Zhang, W. Thematic Evolution and Transmission Mechanisms of China’s Rural Tourism Policy: A Multi-Level Governance Framework for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9187. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209187

Hu H, Yin Y, Xie Y, Cai J, Wang C, Zhang W. Thematic Evolution and Transmission Mechanisms of China’s Rural Tourism Policy: A Multi-Level Governance Framework for Sustainable Development. Sustainability. 2025; 17(20):9187. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209187

Chicago/Turabian StyleHu, Haoqian, Yifen Yin, Yingchong Xie, Jingwen Cai, Chunning Wang, and Wenshuo Zhang. 2025. "Thematic Evolution and Transmission Mechanisms of China’s Rural Tourism Policy: A Multi-Level Governance Framework for Sustainable Development" Sustainability 17, no. 20: 9187. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209187

APA StyleHu, H., Yin, Y., Xie, Y., Cai, J., Wang, C., & Zhang, W. (2025). Thematic Evolution and Transmission Mechanisms of China’s Rural Tourism Policy: A Multi-Level Governance Framework for Sustainable Development. Sustainability, 17(20), 9187. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209187